Niesig v. Team I Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 15, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Niesig v. Team I Brief Amici Curiae, 1990. eb885d9b-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cadadae3-abe1-400c-821b-7f5ea114687b/niesig-v-team-i-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

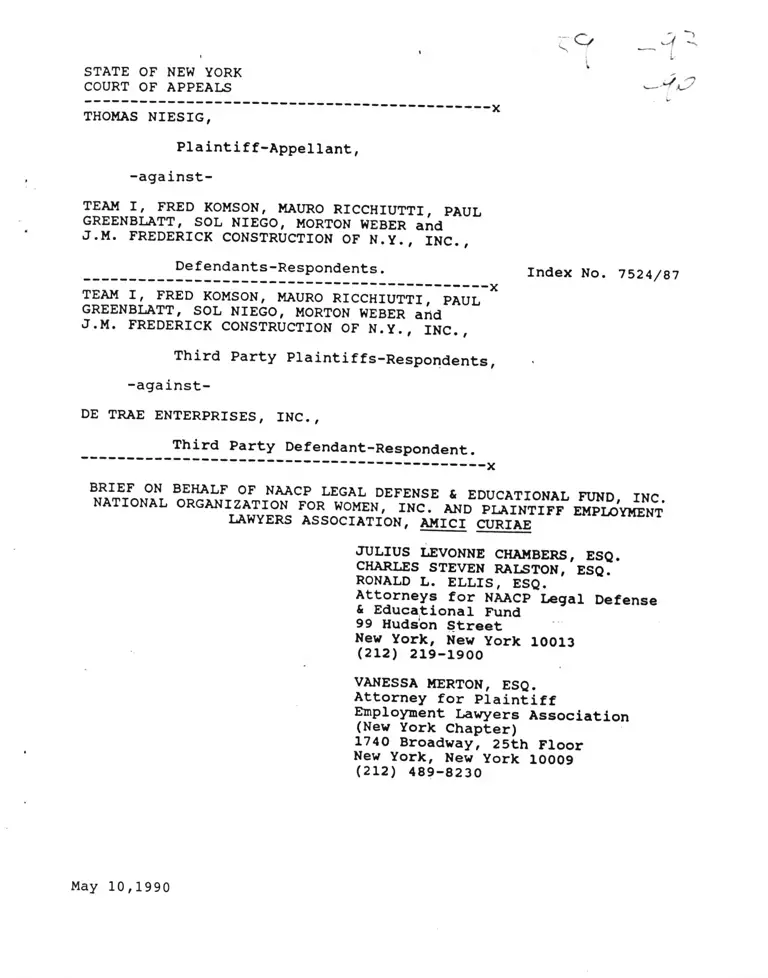

THOMAS NIESIG,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

-against-

STATE OF NEW YORK

COURT OF APPEALS

TEAM I, FRED KOMSON, MAURO RICCHIUTTI, PAUL

GREENBLATT, SOL NIEGO, MORTON WEBER and

J.M. FREDERICK CONSTRUCTION OF N.Y., INC.,

_________ Defendants-Respondents. Index No. 7524/87

TEAM I, FRED KOMSON, MAURO RICCHIUTTI PAUL X GREENBLATT, SOL NIEGO, MORTON WEBER and

J.M. FREDERICK CONSTRUCTION OF N.Y., INC.,

Third Party Plaintiffs-Respondents,

-against-

DE TRAE ENTERPRISES, INC.,

Third Party Defendant-Respondent.

x

BEHALF OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND INC NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN, INC. AND PLAINTIFF EMPLOYMENT

LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, AMICI CURIAE

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS, ESQ.

CHARLES STEVEN RALSTON, ESQ. RONALD L. ELLIS, ESQ.

Attorneys for NAACP Legal Defense& Educational Fund99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013(212) 219-1900

VANESSA MERTON, ESQ.

Attorney for Plaintiff

Employment Lawyers Association (New York Chapter)

1740 Broadway, 25th Floor New York, New York 10009 (212) 489-8230

May 10,1990

KIM GANDY, ESQ.

Attorney for National Organization for Women, Inc.

1401 New York Avenue, N.W.Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20005-2102 (202) 347-2279

STEEL & BELLMAN, P.C.

Attorneys for all Amici 351 Broadway

New York, New York 10013 (212) 925-7400

On the Brief

MIRIAM F. CLARK

LEWIS M. STEEL

10

4

6

7

9

8

7

5

5

4

4

9

9

6

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES AND CASES

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver 415 U.S. 35, 47 (1974)

Christianburq Garnet Co. v. EEOC 434 U.S. 434 412 (1978)

EEOC v. Plumbers Local

311 F. Supp 464 (S.D. Ohio 1970)

Frank v. Capital Communications 25 FEP 1186 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)

Gulf Oil v. Bernard

452 U.S. 89 (1981)

Havens Realty v. Coleman 455 U.S. 363 (1982)

Hunter v. Allis Chalmers Coro.797 F2d 1417 (7th Cir. 1986)

McDonnell Douglas v. Green 411 U.S. 792 (1973)

NLRB v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co. 437 U.S. 214 (1978) “

New York Gaslight Club v. Carev 447 U.S. 54, 63 (1980)

Newman v. Piggie Park Enternrispg 390 U . S . 400, 402 (1968)

Niesig v. Team I.

149 A.D.2d 94 (2nd Dept. 1989) passim

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins 109 S. Ct. 1775 (1989)

Sheehan v, Purolator Inc.839 F2d 99 (2d Cir.)

cert, denied 109 S Ct. 226 (1988)

Snell y, Suffolk County

782 F2d 1094 (2d Cir. 1986)

State Division of Human Rights v. Kilian35 N.Y. 201 (1974) -------------....................... 4,9

Taylor v. General Electric Coro.87 Civ. 1211C (WDNY 3/15/90) ............

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co 7 09 U.S. 207 (1972) 7777------ 1

Fed R. civil Proc. 23

N.Y. Civ. Practice Law & Rules 901

...................... 8

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This brief focuses the Court's attention on the extraor

dinarily detrimental effect the rule in Niesiq v. Team I. 149

A.D.2d 94 (2d Dept. 1989) will have on civil rights litigation if

it is adopted by this Court. As presently formulated, the rule

is so broad that it will apply to virtually all forms of communi

cation between an employee, an applicant, or an employee's

attorney and a corporate defendant. Such a rule, as amici show

below, severely impairs plaintiffs and their counsel in their

role as private attorneys general enforcing laws of critical

public importance and will substantially set back civil rights

enforcement in both federal and state courts. See, Taylor v.

General Electric Corp., 87 Civ. 1211C (W.D.N.Y. 3/15/90), at

tached hereto, and cases cited therein.

Given the importance and difficulty of civil rights enforce

ment, the Court should be wary of attempts to impose so-called

bright line, across-the-board rules on private attorneys general.

Standards of conduct for plaintiffs and their attorneys, there

fore, should be developed only after careful consideration of the

facts of individual cases.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Amici understand that the major facts are not in dispute and

therefore adopt the Statement of Facts set forth in the memo

randum of law of plaintiff-appellant.

-2-

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICI

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. is a non

profit corporation, incorporated under the laws of the State of

New York in 1939. It was formed to assist blacks to secure their

constitutional and civil rights by the prosecution of lawsuits.

The charter was approved by a New York Court, authorizing the

organization to serve as a legal aid society.

The Plaintiff Employment Lawyers Association is a non-profit

association of attorneys in 49 states whose practice involves the

representation of individual employees seeking to vindicate basic

employment rights. The clients of many PELA members are employ

ees who lack union representation and need legal assistance to

prevent or redress discriminatory or wrongful treatment in the

workplace. New York PELA, the amicus herein, is the PELA chapter

for attorneys practicing in the State of New York.

The National Organization for Women, Inc. is a membership

organization of over 250,000 members in 800 chapters nationwide.

It was founded in 1966 and has among its goals the elimination of

discrimination in employment, and the effective enforcement of

laws and regulations regarding egual employment opportunities.

-3-

ARGUMENT

UNDER THE NIESIG RULE, CIVIL RIGHTS PLAINTIFFS

AND THEIR ATTORNEYS, IN THEIR ROLE AS

PRIVATE ATTORNEYS GENERAL, WILL BE BARRED

FROM INVESTIGATING AND PROSECUTING MERITORIOUS ACTIONS

The United States Supreme Court has reaffirmed time and

again that the "main generating force" behind civil rights laws

is "private suits, in which . . . the complainants act not only

on their own behalf but also 'as private attorneys general in

vindicating a policy that Congress considered to be of the

highest p r i o r i t y . Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance

Co»/ 409 U.S. 207 (1972), citing Newman v. Piqgie Park Enter

prises, 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968).1 In affirming this Court's

decision that attorneys' fees may be awarded to a successful

civil rights plaintiff for representation before the New York

State Division of Human Rights, the United States Supreme Court

reaffirmed that civil rights plaintiffs are cast by Congress in

the role of private attorneys general and held that "one of

Congress' primary purposes in enacting [Title VII] was to 'make

it easier for a plaintiff of limited means to bring a meritorious

suit.'" New York Gaslight Club v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 63 (1980),

quoting Christianburq Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412, 420

(1978) .

The Appellate Division's decision in Niesiq eviscerates this

policy almost entirely. A review of civil rights cases over the

reveals that had the Niesig rule been in place, civil

The leading role taken by the anti-discrimination laws of the State of New York is well established. State Division of Human Rights v. Kilian. 35 N.Y.2d 201 (1974). ----

-4-

rights enforcement would have been significantly weakened. For

example, in the seminal case of McDonnell-Douglas v. Green, 411

U.S. 792 (1973), the Supreme Court set forth a now familiar

standard of proof of a disparate treatment case. The Court

suggested that plaintiff produce the following evidence in

support of its argument that the employer's real motive was

discriminatory: "[E]vidence that white employees involved in

acts . . . of comparable seriousness were . . . retained or

rehired" and evidence concerning the employer's "general policy

and practice with respect to minority employment." McDonnell-

Douglas , 411 U.S. at 804. As a rule, neither plaintiff nor his

or her lawyer can obtain this information without discussions

with plaintiff's co-workers. To insist that company counsel be

present at each of these discussions is to ensure the intimida

tion of many of these potential witnesses into silence. This is

especially true because Niesiq places no limits on the contacts

between corporate counsel and these employees — before, during

and after discussions with plaintiff's counsel. As the United

States Supreme Court has warned, "The danger of witness intimi

dation is particularly acute with respect to current employees —

whether rank and file, supervisory, or managerial — over whom

the employer, by virtue of the employment relationship, may

exercise intense leverage. Not only can the employer fire the

employee, but job assignments can be switched, hours can be

adjusted, wage and salary increases held up and other more subtle

forms of influence exerted." NLRB v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co..

437 U.S. 214, 240 (1978). See EEOC v. Plumbers Local 189. 311

-5-

F.Supp. 464, 466 (S.D.Ohio 1970) (conversations with union and

employer present held to be coercive and statements made during

the course thereof not truly voluntary).

The pressing need for an employment discrimination plaintiff

and his or her counsel to communicate privately with other

employees is starkly illustrated by the recent decision of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Snell v.

Suffolk County, 782 F.2d 1094 (2d Cir. 1986), affirming 611

F.Supp. 521 (E.D.N.Y. 1985), a case involving overt and wide

spread racial harassment of corrections officers employed by

Suffolk County. The district court in that case, Chief Judge

Jack Weinstein, denied plaintiffs' motion for class certifica

tion, but ordered plaintiffs' counsel to canvass other minority

employees and determine if they wished to join in the action.

Under Niesig, of course, such an action would have been pro

hibited. Moreover, the Court's description of the work environ

ment in Suffolk County makes clear the need for plaintiffs'

counsel to interview fellow employees outside the presence of

opposing counsel. One witness, for example, testified that after

an unsuccessful attempt to challenge the harassment in an admin

istrative hearing, a group of white officers marched outside the

hearing room chanting and carrying signs declaring, "We have the

spic." Snell, 782 F.2d at 1098. Several other officers testi

fied that they had also suffered and witnessed racial harassment,

but had chosen not to report it for fear of retaliation. Id., at

1105, n. 13. In such an atmosphere, the presence of an employ

-6-

er's lawyer during a discussion of working conditions is likely

to close off any meaningful discussion.

Similar workplace conditions prevailed in Hunter v. Allis-

Chalmers Corp., 797 F.2d 1417 (7th Cir. 1986), in which plaintiff

described racial harassment to include racial graffiti on the

bulletin board and tampering with tools. Significantly, much of

plaintiff's evidence in that case concerned the harassment of

other employees, such as derogatory notes and a hangman's noose

left in another worker's equipment. Hunter also presented

evidence that his foreman called another black worker a "nigger"

and often referred to other black workers as "niggers" behind

their backs. Hunter, 797 F.2d at 1420. The Court held that the

evidence of Hunter's co-workers was "pertinent, perhaps essen

tial, to Hunter's case." Id. , at 1424. Neither Hunter nor his

lawyer could have gathered this evidence without open discussions

with other black and white employees. In fact, the opinion notes

that Hunter's lawyer visited the plant during the investigatory

process. Id., at 1420. Again, it is hard to believe that the

presence of Allis-Chalmers' lawyer during these discussions would

not have significantly inhibited these already burdened employ

ees .

The need for plaintiff's counsel in an employment dis

crimination case to communicate with his or her client's fellow

employees was clearly explained by the court in Frank v. Capital

Cities Communications, 25 FEP 1186 (S.D.N.Y 1981). In that case,

an age discrimination plaintiff requested permission to notify

-7-

other employees of the suit pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §626(b). The

court granted permission, stating:

The experience of other employees

may well be probative of the exis

tence vel non of a discriminatory

policy, thereby affecting the merits

of plaintiff's own claims; and the

notice machinery contemplated by the

ADEA may further the statute's

remedial purpose. 25 FEP at 1188.

Pursuant to Niesig, however, all further communications between

these potential plaintiffs and plaintiffs' counsel would have to

be conducted under the watchful eye of corporate counsel, thus

rendering impossible any substantive discussion about strategy or

the strengths and weaknesses of potential claims.

After Niesig, a plaintiff's ability to prove housing dis

crimination may also be sharply curtailed. Under the testing

procedure approved by the Supreme Court in Havens Realty v.

Coleman, 455 U.S. 363 (1982), minority and white housing appli

cants are sent by a civil rights group to a broker or landlord

suspected of discrimination. If the white applicants are treated

more favorably than the minority applicants, a lawsuit may be

brought. However, under Niesig, communications between the

testers and the broker's employees would be grounds for disci

plinary sanctions for plaintiff's counsel, if the broker were

represented by counsel in any pending litigation.

The Niesig rule would also have a detrimental effect on

plaintiffs' ability to successfully move for class certification

under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23.2 Under that Rule,

. tSupreme Court has held that it was beyond the power of a

^ls^ric"t court under the Federal Rules to issue a blanket

-8-

plaintiffs must prove that other affected employees are too

numerous to be conveniently joined, and that plaintiffs' claims

are common and typical to those of other potential class mem-

3bers. The same general requirements apply to putative class

actions brought under CPLR §901. Without discussions with

potential class members, meaningful investigation may be impos

sible .

Time and again, the federal and state courts have taken

judicial notice of the difficulty of proving civil rights cases.

For example, Justice O'Connor recently observed, "As should be

apparent, the entire purpose of the McDonnell—Douglas prima facie

case is to compensate for the fact that direct evidence of

intentional discrimination is hard to come by." Price Waterhouse

v. Hopkins, __ U.S. __, 109 S.Ct. 1775, 1801-02 (1989) (O'Connor,

J., concurring).

As this Court stated in State Division of Human Rights v.

Kilian, 35 N.Y.2d 201, 209 (1974), "[d]iscrimination today is

rarely so obvious, or its practices so overt that recognition of

the fact is instant and conclusive. One intent on violating the

Law Against Discrimination cannot be expected to declare or

prohibition on plaintiffs' counsel speaking to prospective

employee class members in a Title VII action. The Fifth Circuit had reached the same conclusion on the ground that such a

prohibition would violate the First Amendment. Gulf Oil v.

Bernard, 452 U.S. 89 (1981), affirming 619 F.2d 459 (5th Cir. 1980)•

For example, the Second Circuit has affirmed a district court

decision denying class certification because plaintiffs did not

present a sufficiently detailed showing concerning the specific

complaints of other class members. Sheehan v. Purolator. Inc..

839 F.2d 99 (2d Cir.), cert, den., 109 S.Ct. 226 (1988). L'

-9-

announce his purpose. Far more likely is it that he will pursue

his discriminatory practice in ways that are devious, by methods

subtle and elusive — for we deal with an area in which

'subtleties of conduct . . . play no small part. '" By severely

restricting the ability of civil rights plaintiffs and their

lawyers to gather necessary evidence, Niesig impedes vigorous

enforcement of civil rights laws, which the Supreme Court has

repeatedly deemed a matter of the "highest priority." Alexander

v. Gardner-Denver. 415 U.S. 35, 47 (1974).

-10-

CONCLUSION

In dismissing out of hand plaintiff's public policy argu

ments, the Niesig court stated that these arguments are "likely

to persuade only those who, contrary to the basic axioms of the

American legal system, believe that one-sided, inquisitorial

procedures are more effective than adversarial ones in arriving

at the truth." Niesig, 545 N.Y.S.2d at 161. In fact, the Niesig

rule, by allowing only corporate counsel to communicate privately

with employees, sets up a one-sided, inquisitorial system which

severely weakens enforcement of civil rights laws and which is

completely antithetical to the American policy of assigning the

highest priority to civil rights litigation. Therefore, the

decision of the Appellate Division should be reversed.

Dated: New York, New York Respectfully submitted,May 10, 1990

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS, ESQ.

CHARLES STEVEN RALSTON, ESQ.RONALD L. ELLIS, ESQ.

Attorneys for NAACP Legal Defense& Educational Fund99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013(212) 219-1900

VANESSA MERTON, ESQ.

Attorney for Plaintiff

Employment Lawyers Association (New York Chapter)

1740 Broadway, 25th Floor New York, New York 10009

(212) 489-8230

KIM GANDY, ESQ.

Attorney for National Organization for Women, Inc.

1401 New York Avenue, N.W.Suite 800

Washington, D.C. 20005-2102 (202) 347-2279

-11-

STEEL & BELLMAN, P.C.

Attorneys for Amici

351 Broadway

New York, New York 10013

(212) 925-7400

On the Brief

MIRIAM F. CLARK

LEWIS M. STEEL

-12-

AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE

STATE OF NEW YORK )

ss. :COUNTY OF NEW YORK)

PATRICIA M. COOPER, being duly sworn, deposes and says, I am

not a party to the action, am over 18 years of age and reside at

351 Broadway, New York, New York.

On May 11, 1990, I caused to be personally served the within

Notice of Motion for Leave to Appear as Amici Curiae, supporting

Affirmation, and Brief in Support of Motion for Leave to Appear

as Amici Curiae, by delivery of true copies thereof to each

person named below at the address indicated:

EMILY M. BASS, ESQ.

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant

330 Madison Avenue, 33rd Floor

New York, New York 10017

PATRICK CROWE, ESQ.

Attorneys for Third Party Defendant- Respondent

De Trae Enterprises, Inc.

McCoy, Agoglia, Beckett & Fassberg, P.C.80 East Old Country Road Mineola, New York 11501

STEVEN K. MANTIONE, ESQ

Attorneys for Defendant Third Party

Plaintiff-Respondent

J.M. Frederick Construction of New York, Inc. Gerard A. Gilbride, Jr.

20 Crossways Park North

Woodbury, New York 11797

STEVEN A. FRITZ, ESQ.

Attorneys for Defendants Third

Party Plaintiffs-Respondents

Team I, Fred Komson, Mauro Ricchiutti,

Paul Greenblat, Sol Niego and Morton Weber Purcell, Fritz & Ingrao, P.C.204 Willis Avenue

Mineola, New York 11501

Sworn to before me this

11th day of May, 1990.

NOTARY PUBLIC

V O A M S N »0 OJ25S

aavio a wvihiw

Notary © ^ f - C U R K0 o^Yorfc

Q ualified h t?;-65

u’se/on E x p ire s 5 3 Coun?y, >Commisc

-2-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

HAROLD TAYLOR,

- vs -

GENERAL ELECTRIC CORP.,

Plaintiff,

Defendant.

CIV-87-1211L

Take notice of an Order of which the within is

a copy, duly granted in the wUhin ent.tled act,on ^ the

15th day of March, 1990 and entered in the office

Clerk of the United States District Court, Western

District of New York , on the 15th day of March, 1990.

Rochester, New York

March 15, 1990

'«■' -1- G IT K.

u. S. District Court

DiStriot °f Ne" 282 U. S. Courthouse

Rochester, New York 14614

Emmelyn Loaan-Baldwin, Esq Edward Ryan Conan, Esq.

017

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

HAROLD TAYLOR,

Plaintiff,

v.

GENERAL ELECTRIC CORP.,

Defendant.

DECISION AND ORDER

Civ. 37-1211L

By letter dated December 15, 1989, plaintiff's counsel moved

for permission to conduct ex parte interviews with current and

former employees of General Electric, on the authority of Jones

v. Monroe Community College, unpublished decisions of Judge (now

Chief Judge) Telesca and Judge (then Magistrate) Larimer (Civ.

84-704T, August 30, 1984 and April 18, 1984). Plaintiff's

counsel commendably identified a New York Appellate Division

decision prohibiting ex parte current employee interviews on

ethical grounds, Niesiq v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d 94, 545 N.Y.S.2d

153 (2d Dept. 1989), but asserted that it "is not controlling in

this case." Logan-Baldwin letter of December 15, 1989, at p.10.

Defense counsel moves, by letter dated January 4, 1990,

supplemented by a letter dated January 15, 1990, for a protective

order prohibiting such interviews of current General Electric

employees. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(c). I ordered plaintiff's counsel

to comply with Niesiq until I determined the merits of the motion

(docket entry #63). In his January 15th letter, defense counsel

explicated the Niesiq decision, and argued: "By its terms, the

holding in Niesiq v- Team I applies to all attorneys who practice

law in New York State, and is therefore controlling on counsel to

018

No issue is raised with respect to GE's formerthis litigation,

employees. See Polvcast Technology Corporation v. Uniroval.

Inc.. ___ F. Supp. ___ (S.D.N.Y. February 13, 1990); Amarin

Plastics. Inc, v. Maryland Cup Corporation. 116 F.R.D. 36, 39-41

(D. Mass. 1987); Niesig v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d at 100 n.l.

By letter dated February 15, 1990, plaintiff's counsel

replies that Niesig may not be applied in this case "to current

employees of the company where there is a conflict of interest

between the current employee and the company." (emphasis

deleted). She contends that all current employees on her list of

requested depositions have such a conflict, and asserts that "it

is obvious that Mr. Conan cannot purport to represent them

because the company interest and the employee interest is in

conflict."

Plaintiff's counsel attempts to provide "examples of these

conflicts "by referring to (1) Devora Mclver, who purportedly had

an affair with plaintiff and has retained her own counsel; (2)

Geoffrey Burnham and Sue Carmey, who were evidently the subject

of a report to the Defense Department; and (3) other employees

who have had some personnel action taken against them by GE.

Plaintiff's counsel reasons that Mr. Conan cannot, consistent

with ethical precepts, represent these named employees. She

means, presumably, that the Niesig rule by its terms could not

apply to any employee who became the subject of a personnel

action by the company.

Finally, plaintiff's counsel argues that Niesig "is poorly

reasoned and absolutely wrong on the law." She further contends

2

019

that "[i]t has no application in an employment discrimination

lawsuit." Logan-Baldwin letter of February 15th, at p. 13.

Because Niesiq has dramatically changed the legal landscape since

this district's unpublished decisions six years ago in Jones v.

Monroe .Community College, supra. a reexamination is in order.

For the following reasons, defendants' motion for a protective

order should be granted.

A. The Niesiq Decision

Last August, the Appellate Division Second Department issued

a significant decision interpreting New York's version of DR 7-

104(A)(1) of the ABA Code of Professional Responsibility as it

applies to corporate clients. DR 7-104(A)(1) prohibits a lawyer

who represents a client from "[c]ommunicat[ing] . . . on the

subject of the representation with a[nother] party [s]he knows to

be represented by a lawyer in that matter unless [s]he has the

prior consent of the lawyer representing such other party or is

authorized by law to do so." When a corporation is a "party" the

question arises whether this rule applies to only a small group

of the company's managers or to all corporate employees.

Hlesig resolved that issue as follows: "We hold that the

terms of DR 7-104(A)(1) may effectively be enforced 'only by

viewing all present employees of a corporation as parties'"

Niesiq v.— Team 1, 149 A.D.2d at 106 (emphasis in original)

(quoting N.Y. City Opn. 80-46). in particular, Niesiq rejected

the more recent ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 4.2

(Comment)(ex parte contact is permissible "with lower echelon

employees who are not representatives of the organization"), as

3

020

-totally unworkable." Id. 149 A.D.2d at 104.1 The court found

that acceptance of another rule "would engender a significant

amount of litigation addressed to the question of whether, in

particular cases, particular corporate employees are or are not

within the company's 'control group."' Id. 149 A.D.2d at 105.

The court summarized, "In the interest of clarity, then, we

reject the 'control group' and hold, as has at least one other

court, that '[i]t is not proper for opposing counsel or its

investigator to contact ex parte an employee of a corporation

that is a party to a suit knowing that the information sought

from the employee relates to a subject of controversy.'" id. 149

A.D.2d at 106 (quoting Hewlett-Packard Co. v. Superior Cnnrf

iJensen), 252 Cal. Rptr. 14, 16, 205 Cal. App.3d 986, (Cal. App.

4th Dist. 1988) ) .

0 . . _lv.en interpretation of the revised Comment to Model

U % 4’o ln Technology Corporation v. Uniroval. Inc. .--- . Supp. at — _— ("the expanded comments to Rule 4.2, . . .were intended to insure that current employees — whether

participants or witnesses — would not be subject to

in errogation by an adversary's attorney except through formal discovery ), which I accept, the perceived difference is

academic. In any event, the ABA Model Rules were rejected by the

ew ork State Bar Association House of Delegates in favor of

amendments to the existing Code of Professional Responsibility.

Amendments to the Code were approved by the House of Delegates in

o!?d4-Were sut)Initted to the four Appellate Divisions of New ork State Supreme Court, which are vested with defining and

enforcing the standards of Professional Conduct under New York

7^; /2'Y\ J UdlClary Law § 9°(2)- See e.g. . 22 N.Y.C.R.R. Part 1022 (Fourth Department); id. §1022.17 (defining misconduct to

include a violation of a Disciplinary Rule of the Code of

ro **®sponsibility) . None of the Amendments proposed

affect DR 7-l04(A)(l). After appointment of the so-called Kane

ommission, the Appellate Divisions are expected to approve a

close variant of the proposed amended Code as a court rule.

021

embraced the underlying rationale articulated in that ethics

opinion, which reasons:

It is our opinion, however, that the Code in

DR 7-104(A)(1) has determined that the

considerations in favor of permitting a party

and his client to discover the facts must be

subordinated to the need to protect an

adverse lay party from unsupervised

communications with opposing counsel and the

need of counsel for the adverse party to

provide effective representation. Since we

believe a corporate party is equally entitled

to the benefit of these policies, we are

required to shape the scope of DR 7-104(A)(1)

to assure that the corporation is provided

the effective representation that the

disciplinary provision is designed to

protect.

N.Y. City 80-46 (Part IV, last paragraph). In addition, the

court scrutinized the asserted interest of the plaintiff in

conducting an ex parte interview.

[The rule does] not prohibit plaintiff's

counsel from interviewing these witnesses; it

merely prohibit[s] such interview from

occurring ex parte. Thus, it is clear that

the interest sought to be advanced by

plaintiff is not that of obtaining the

information necessary to prepare for trial,

but rather, that c obtaining such

information in a r ticular wav, that is,

through the procedure of an ex parte

interview. Once it is seen for what it is,

the plaintiff's argument that such ex parte

interviews should be allowed in order to

advance his "search for the truth" is likely

to persuade only those who, contrary to the

basic axioms of the American legal system,

believe that one-sided, inquisitorial

procedures are more effective than

adversarial ones in arriving at the truth.

The real interests which the plaintiff

seeks to advance in this case are too obvious

to be concealed by his repeated references to

"the quest for truth."

By adopting N.Y. City 80-46, supra, the court in Niesjg

5

922

Niesiq v._Team 1. 149 A.D.2d at 107 (emphasis in original).

Finally, the court in Niesiq concluded that, "given the fact that

attorneys have an obligation not only to avoid engaging in

conduct which is actually unethical, but also to avoid engaging

in conduct which even appears to be unethical [citations

omitted,] [t]he integrity of the legal profession would not be

well served by the creation of a rule which infuses a substantial

amount of ambiguity into one of the most important and most

widely recognized of all ethical precepts [citations omitted]."

Id. 149 A.D.2d at 108.

B* Enforcement of Ethical Rules in the Federal Courts

Plaintiff contends that Niesiq has no application in an

employment discrimination case. Defendants contend that Niesiq

applies to all attorneys in New York State and, ipso facto,

applies to counsel in this case.

That Niesig applies to attorneys licensed in New York cannot

be doubted. The Appellate Division of State Supreme Court

governs professional behavior in New York. N.Y. Judiciary Law

§ 90(2) . Furthermore, a ruling by one of the four coordinate

departments of the Appellate Division of State Supreme Court is,

absent New York Court of Appeals or other Appellate Division

authority to the contrary, a binding precedent within the state

court system. Mountain View Coach Lines. Inc, v. Storms. 102

A.D.2d 663, 664-65, 476 N.Y.S.2d 918 (2d Dept. 1984); Sheridan v.

Tucker, 145 App. Div. 145, 147 (4th Dept. 1911); 1 Carmody-Wait

2d' Cyclopedia of New York Practice § 2:58 pp. 69-70, § 2.63 p.75

(2d ed. 1965) . Niesiq unquestionably applies to New York

6

023

attorneys and a violation of the rule articulated in that case

may lead to "disqualification [of the attorney], as well as to

disciplinary sanctions." Niesig v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d at 105.

Whether an authoritative New York judicial interpretation of

an ethical rule applies to govern conduct of attorneys in federal

litigation is a more difficult question. The Supreme Court has

stated, "Federal courts admit and suspend attorneys as an

exercise of their inherent power; the standards imposed are a

matter of federal law." In re Snyder. 472 U.S. 634, 645 n.6

(1985).2 Perhaps in recognition of the lack of any comprehensive

statement or collection of federal professional responsibility

standards, however, the Court pointed out that "[t]he uniform

first step for admission to any federal court is admission to a

state court." Id. Therefore, it is fair for a district court

"to charge . . . [a lawyer admitted to practice in that court]

with the knowledge of and the duty to conform to the state code

of professional responsibility." Id. In other words, federal

courts obtain the "[m]ore specific guidance . . . provided by

case law, applicable court rules, and 'the lore of the

profession' as embodied in codes of professional conduct." Id.

472 U.S. at 645 (text at fn. 6). Cf., In re Grievance Committee

2 For that proposition, the Court relied on Hertz v. United

States. 18 F.2d 52, 54-55 (8th Cir. 1927), which rejected an

argument that a lawyer, charged in federal court with misconduct

committed in federal court sufficient to warrant disbarment by

that federal court, was entitled to application of state created

disbarment procedures prescribing the standards of disbarment and

an applicable limitations period. The circuit court held that

"[i]ts power (to admit and disbar attorneys) could be affected

only by action of Congress and such action has not been taken."

Id. 18 F.2d at 55.

7

024

of the United States District Court for the District of

Connecticut, 847 F.2d 57, 61-63 (2d Cir. 1988)(relevant also are

the drafting history of the Code, its structure, and decisions

from other jurisdictions).

In the Second Circuit, DR 7-104(A)(1) is vigorously applied

in criminal matters, United States v. Hammad. 858 F.2d 834, 837-

38 (2d Cir. 1988),3 and there is no reason to believe that it

has any less effect on civil litigation. See e.q.. W.T. Grant

Co. v. Haines, 531 F.2d 671, 674 (2d Cir. 1976)(interpreting and

applying New York's version of DR 7-104(A)(1)); Ceramco. Inc, v.

Lee Pharmaceuticals. 510 F.2d 268, 270-71 (2d Cir. 1975)

The applicability of DR 7-104(A)(1) to federal

prosecutors, recently reaffirmed in a policy statement of the

American Bar Association despite Supremacy Clause objections

raised by Attorney General Richard Thornburgh, ABA House of

Delegates Report No. 301 (adopted February 12, 1990, as amended),

was recently underscored by the four dissenting justices in

Michigan v. Harvey. 58 U.S.L.W. 4288, 4294 n.12 (March 5,

1990) (Stevens, J., dissenting, joined by Justices Brennan,

Marshall and Blackmon). In opposition to the ABA resolution,

Attorney General Thornburgh wrote of the difficulties application of DR 7-104(A)(1) creates when Justice Department Civil division

attorneys attempt ex parte interviews of corporation employees.

Nevertheless, the resolution was passed by the House of Delegates

and endorsed in Justice Stevens' dissent. The majority in Harvey

did not touch on the matter, perhaps because the issue was not

raised at the trial level (58 U.S.L.W. at 4288-89), and because

the Court had earlier determined that DR 7-104(A)(1) "does not

bear on the constitutional question" raised in Sixth Amendment

cases- United States v. Henrv. 447 U.S. 264, 275 n.14, 100 S.Ct. 2183, 2189 n.14 (1980)(emphasis supplied. Cf. Patterson v.

Illinois, ___ U.S. ___, 108 S.Ct. 2389, 2393 n.3 (1988); id. 108

S.Ct. at 2399-2400 (Stevens, J., dissenting). Of course federal

prosecutors have the protection of a federal forum if retaliatory

state disciplinary charges are brought. Kolibash v. Committee on

Legal Ethics of the West Virginia Bar. 872 F.2d 571, 575 (4th

cfr* 1989). Whatever the Supreme Court's view, the rule in this

circuit, expressed in Hammad. is that DR 7-104(A)(1) does not

present an impediment to the Supremacy Clause in the area of

federal criminal investigations. Therefore, it should provide no

impediment to federal interests in this Title VII litigation.

8

Q25

Lee Pharmaceuticals. 510 F.2d 268, 270-71 (2d Cir. 1975)

(anonymous phone call to employee of corporate adversary "is not

to be commended"); Papanicolaou v. Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A.,

720 F. Supp. 1080, 1084 (S.D.N.Y. 1989). As the Second Circuit

has repeatedly recognized, "[t]he Code is recognized by both

state and federal courts within this circuit as providing

appropriate guidelines for proper professional behavior." Fund

of Funds. Ltd, v. Arthur Anderson & Co.. 567 F.2d 225, 227 n.2

(2d Cir. 1977). See NCK Organization Ltd, v. Brecrman. 542 F.2d

128, 129 n.2 (2d Cir. 1976); Cinema 5, Ltd, v. Cinerama. Inc..

528 F.2d 1384, 1386 (2d Cir. 1976)("The Code has been adopted by

the New York. State Bar Association, and its canons are recognized

by both Federal and State Courts as appropriate guidelines for

the professional conduct of New York lawyers."); Paretti v.

Cavalier Label Co. . Inc.. 722 F. Supp. 985, 986 (S.D.N.Y. 1989);

Cresswell v. Sullivan & Cromwell. 704 F. Supp. 392, 400 (S.D.N.Y.

1989)(same). The applicability of the Code in this district is

clear even if it "has not been formally adopted" in a local rule.

Hull v. Celanese Corporation. 513 F.2d 568, 571 n.12 (2d Cir.

1975) .4

4 This treatment contrasts with the Rule elsewhere.

Culebras Enterprises Corporation v. Rivera-Rios. 846 F.2d 94, 98

(1st Cir. 1988)("absent promulgation by means of a statute or a

court rule, ethical provisions of the ABA or other groups are not

legally binding upon practitioners."); E.F. Hutton & Company v.

Brown. 305 F. Supp. 371, 377 n.7 (S.D. Tex. 1969). The court in

Culebras Enterprises cited International Electronics Corporation

v. Flanzer. 527 F.2d 1288, 1293 (2d Cir. 1975) in support of the

parenthetical quotation, ante. but as is demonstrated in the

text, infra, Flanzer involves a different and functionally

unrelated principle.

9

026

That federal courts look to state codes of professional

conduct in regulating the profession pursuant to their inherent

or supervisory authority over members of the bar does not

establish that an authoritative state court interpretation of a

disciplinary rule will provide an adequate predicate for what is,

in essence, "a matter of federal law." In re Snyder. 472 U.S. at

645 n. 6. It is often observed that "[a] federal court is not

bound to enforce . . . [a state's] view of what constitutes

ethical professional conduct." County of Suffolk v. Long Island

Liqhtinq Co., 710 F. Supp. 1407, 1413-14 (E.D.N.Y. 1988)(and

cases cited). The applicable rule is not so starkly stated. In

this circuit, courts "approach the problem" of interpreting the

Code by "'examining afresh the problems sought to be met by that

Code, to weigh for itself what those problems are, how real in

the practical world they are in fact, and whether a mechanical

and didactic application of the Code to all situations

automatically might not be productive of more harm than good, by

requiring the client and the judicial system to sacrifice more

than the value of the presumed benefits.'" International

Electronics Corporation v. Flanzer, 527 F.2d 1288, 1293 (2d Cir.

1975)(quoting Brief Amicus Curiae of the Connecticut Bar

Association, at p.7, and rejecting "promisciou[s]" use of Canon

9" as a convenient tool for disqualification when the facts

simply do not fit within the rubric of other specific ethical and

disciplinary rules"). On the other hand, recognizing that the

Code should not be treated as "a statute that we have no right to

amend" in "an area of uncertainty," courts "should not hesitate

10

027

to enforce it with vigor" when it "applies in an equitable manner

to the matter before us, " J.P. Foley & Co.. Inc, v.

Vanderbilt. 523 F.2d 1357, 1359-60 (2d Cir. 1975)(Gurfein, J.,

concurring). See Tessier v. Plastic Surgery Specialists. Inc..

___ F. Supp. ___, ___ n.4 (E.D. Va. February 22, 1990); Polyeast

Technology Corporation v. Uniroyal, Inc.. ___ F. Supp. at ___.

Contrast United Sewerage Agency of Washington County, Oregon v.

Jelco Incorporated. 646 F.2d 1339, 1342 n.l (9th Cir.

1981)(rejecting the independent federal interest in ethics code

interpretation for cases involving a federal district court rule

which adopts a state ethics code) .

As indicated by the Second Circuit authority cited in the

preceding two paragraphs, federal courts rarely attempt a

separate delineation of ethical rules which differ from the

primary work of the state bar associations as adopted by the

state courts. The Supreme Court has emphasized:

Since the founding of the Republic, the

licensing and regulation of lawyers has been

left exclusively to the states and the

District of Columbia within their respective

jurisdictions. The States prescribe the

qualifications for admission to practice and

the standards of professional conduct. They

are also responsible for the discipline of lawyers.

Leis v. Flynt. 439 U.S. 438, 442 (1979). It is this historical

fact which the Supreme Court had in mind when it recognized that,

even if "federal law" is applied, the primary source of federal

ethics law is the state codes of professional responsibility. In

re Snyder. 472 U.S. at 645 n.6.

11

028

Unthinking or arbitrary divergence from a state imposed

standard of ethical conduct would also upset the delicate balance

between state and federal courts in administering standards of

Professional behavior to those who practice in these respective

courts. The federal cases which champion a divergent federal

standard of professional responsibility generally fall into two

categories. The first category involves state regulation

inimical to federal constitutional or statutory interests. See

Barnard v. Thorstein, ___ U.S. ___, 109 S.Ct. 1294, 1299-1302

(1989)(Privileges and Immunities Clause)(collecting cases);

Shapero v._Kentucky Bar Association, ___ U.S. , 108 S.Ct.

1916, 1921-25 (1988)(First Amendment)(collecting cases); Goldfarb

— — State Bar, 421 U.S. 773 (1975) (antitrust statute);

County of Suffolk v._Long Island Lighting Company. 710 F. Supp.

at 1414-15 (federal class action device and RICO). Even in this

line of cases, with perhaps the exclusion of Long Island

Lighting, the deference accorded to the state's interest in

regulating the bar is substantial; invalidation of particular

state regulations occurs in the clear cases. Board of Trustees

of the State of New York v. Fox. ___ U.S. ___, 109 S.Ct. 3028,

3034 (1989)("None of our cases invalidating the regulation of

commercial speech involved a provision that went only marginally

beyond what would adequately have served the governmental

interest. To the contrary, almost all of the restrictions

disallowed . . . have been substantially excessive, disregarding

'far less restrictive and more precise means.'")(quoting Shapero

— Kentucky—Bar Association. 108 S.Ct. at 1923) ; Supreme Court of

12

029

Virginia v. Friedman. ___ U.S. ___, 108 S.Ct. 2260, 2265-67

(1988)(even if a bar regulation "burden[s]" a constitutionally

protected interest, it may be upheld if "substantial reasons

exist" for the regulation and, "within the full panoply of

legislative choices otherwise available to the state, there exist

[only more burdensome] alternative means of furthering the

State's purpose without implicating constitutional concerns");5

Supreme Court of New Hampshire v. Piper. 470 U.S. 274, 284-87

(1985) (same) ; cf. _id. 470 U.S. 283 n.16 (constitutionally imposed

non-discriminatory bar admission requirements leave the state

free to apply "the full force of . . . [its] disciplinary rules"

upon out of state admittees); District of Columbia Court of

Appeals v. Feldman. 460 U.S. 462, 482-83 n.16 (1983)("strength of

the state interest in regulating the state bar"); Goldfarb v.

Virginia State, 470 U.S. at 792-93 (same).

The second category may fairly be described as involving an

insufficiently exacting state ethical rule which, if applied in

the federal litigation at hand, threatened the integrity of the

adversary process, see Cord v. Smith. 338 F.2d 516, 524-25 (9th

1964) (state rule arguably more lenient than appropriate to

excuse a former client conflict of interest), modified on other

qrounds, 370 F.2d 418 (9th Cir. 1966), overruled for districts

adopting a state ethics code. Unified Sewerage Agency v. Jelco

Incorporated, 646 F.2d at 1342 n.l; Hertz v. United States. 18

This "less restrictive means" test was loosened somewhat

in Board of Trustees of the State of New York v. Fox. 109 S.Ct. at 3032-35.

13

030

F.2d at 54-55 (state statute of limitations for disbarment

proceedings is insufficient to protect federal proceedings from

obvious professional misconduct evidencing moral fitness for the

federal bar), or as involving an antiquated state standard which,

according to modern authority, needlessly required

disqualification of counsel or invalidation of counsel's

arrangements with the client. County of Suffolk v. Long Island

Lighting Company. 710 F. Supp. at 1413-14; Figueroa-Olma v.

Westinghouse Electric Corn.. 616 F. Supp. 1445, 1450 (D.C. Puerto

Rico 1985); Black v. State of Missouri. 492 F. Supp. 848, 874-75

(W.D. Mo. 1980). While it may be debatable whether any of these

latter decisions may be appropriately categorized, it is enough

to say here that the circumstances with impelled those decisions

are not present here. In addition, contrary to those federal

cases which tend to embrace the most recent bar association

efforts at ethics restatement, courts in the Second Circuit have

accorded considerable deference to New York's version of the Code

of Professional Responsibility in the face of recent promulgation

by several states of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct.

United States v. Hammad. 858 F.2d at 837; United States v. Kwang

Fu Peng, 766 F.2d 82, 86 n.l (2d Cir. 1985); Polvcast Technology

Corporation v. Uniroyal, Inc.. ___ F. Supp. at ___ ("It seems

best to . . . [look to] those ethical guidelines which have not

14

031

only been promulgated by the bar associations but have also

received the imprimatur of the State.")6

Recognizing that Niesiq fully applies to New York lawyers

and that it will provide an adequate predicate for attorney

"disqualification, as well as . . . disciplinary sanctions" in

the New York courts, Niesiq v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d at 105, brings

fully into focus the likely collision between federal and state

interests implementation of a different federal standard may

create. Those cases which stress federal autonomy in defining

professional misconduct recognize, sometimes only implicitly,

that a state is free to enforce its ethical rules consistent with

the Supremacy Clause unless to do so would frustrate a federal

constitutional or statutory policy, or would interfere with

"vindication of the specific federal rights in question." County

of Suffolk v. Long Island Lighting Co.. 710 F. Supp. at 1415.

See also, Mason v. Departmental Disciplinary Committee. 894 F.2d

512 (2d Cir. 1990)("If it should develop that a letter of caution

is issued under circumstances where such action impairs Mason's

federal rights,, we are not foreclosing federal court scrutiny.");

Person v. Association of the Bar of the City of New York. 554

F.2d 534, 538-39 & n.9 (2d Cir. 1977)(federal scrutiny not

appropriate where a disciplinary rule has only a "remote" effect

Although Polycast Technology, as other cases from the

districts downstate involved a local rule incorporation of New

York's code, and although the Western District has not similarly

incorporated the New York Code of Professional Responsibility, it

is worth noting again that the Second Circuit has recognized the

Code's applicability despite the absence of a local rule. Hull

v. Celanese Corporation. 513 F.2d at 571 n.12.

15

032

on an asserted federal interest), cert, denied. 434 U.S. 924, 98

S.Ct. 403 (1977) .

Thus, if no countervailing federal interest is compromised,

departure from an authoritative state court interpretation of DR

7-104(A)(1) would put federal courts at odds with their state

court counterparts, and subject lawyers practicing in New York to

the undesirable juxtaposition of substantially different ethical

rules in a frequently recurring and important area of

professional responsibility. Adhering to New York's

interpretation of the Code where it "applies in an equitable

manner to a matter before us," J.P. Folev & Cn.. Inc, v.

Vanderbilt, 523 F.2d at 1360 (Gurfein, J., concurring), thus

"avoids subjecting attorneys to potentially inconsistent sets of

ethical requirements in the state and federal courts within the

same geographic area." Polycast Technology Corporation v.

Uniroval. Inc.f ___ F. Supp. at .7

is true th.at an attorney disobeying Niesia in reliance on a federal court interpretation may attempt to rely on the

authorized by law" exception to DR 7-104( A ) m . See United

gtates v. Schwimmer, 882 F.2d 22, 28 (2d Cir. l989T7~ci^t:--

enie , -- U.S. --- llo S.Ct. 1114 (1990); Morrison v. Brandei*?

yniysrsity, 125 F.R.D. 14, 15 (D. Mass. 1989)7^ But this solution

to the federal-state conflict created by a differing federal

court interpretation is undesirable, at least, and would leave

attorneys with competing rules to be applied according to the

litiSItiSnfortuitous circumstance of the forum chosen for the

bi United s t a t L ^ S ln Polycast Technology, and as illustratedStates v. Hammad, supra, the avoidance of conflicting

k Professional responsibility "is particularly

is andC? h r / any ^thical ™ les aPPly even before a n actionis filed and the forum designated." Polycast Technology

Corporation v. Uniroval. Tnr., ___ F.“supp. at 7 Also the

disi?if?ratlSn of jusJice' particularly in matters of attorney discipline, demands wherever possible a uniform set of ethical

5V e?’ . faith in the fair administration of attorney

discipline would be compromised by the juxtaposition of competing

rules and the divergent results issuing from coordinate jurisdictions in like circumstances.

16 033

Plaintiff's motion for permission to conduct ex parte

interviews with GE's current employees, therefore, requires an

examination of whether any countervailing federal interest

militates against enforcement of New York's DR 7-104(A)(1). I

conclude that there are none.

The advantages of ex parte or informal witness interviews to

trial counsel may be briefly summarized.

A lawyer talks to a witness to ascertain

what, if any, information the witness may

have relevant to h[er] theory of the case,

and to explore the witness' knowledge, memory

and opinion — frequently in light of

information counsel may have developed from

other sources. This is part of an attorney's

so-called work product [citing Hickman v.

Tavlor. 329 U.S. 495 (1947)]

* * *

We believe that the restrictions on

interviewing set by trial judge [which

prohibited ex parte interviews of witness in

the absence of a court reporter "so that it

can be available to the Court, for the Court

to see it"] exceeded his authority. They not

only impair the constitutional right to

effective assistance of counsel but are

contrary to time-honored and decision-honored

principles, namely, that counsel for all

parties have a right to interview an adverse

party's witnesses (the witness willing) in

private, without the presence or consent of

opposing counsel and without a transcript

being made.

* * *

The legitimate need for confidentiality in

the conduct of attorneys' interviews, with

the goals of maximizing unhampered access to

information and insuring the presentation of

the best possible case at trial, was given

definitive recognition by the Supreme Court

in Hickman v. Tavlor. 329 U.S. 495 (1947) .

* * *

17

034

Building on the rationale of Hickman, courts

have also specifically forbidden interference

with the preparation of a client's defense by

restricting his counsel's ability to freely

interview witnesses willing to speak with h[er].

International Business Machines Corporation v. Edel^t^in, 526

F.2d 37, 41 43 (2d Cir. 1975)(emphasis and bracketed material in

original). These considerations, of course, apply to witness

interviews, not ex parte interviews with an opposing party. when

a party is the subject of the interview, the interests sought to

be protected by DR 7-l04(A)(l), specifically the right to

effective representation, fully outweigh the interest in

unrestricted access to information. Access to information is not

prevented by DR 7-104(A)(1). Information may be obtained from a

party if the party's right to effective representation is

honored.

The considerations articulated in IBM v. Edelstein, supra,

have been employed by some courts in holding that DR 7-104(A)(1)

does not forbid informal interviews with corporate employees of

the opposing party. see e^., Morrison v. Brandeis University

125 F.R.D. at 18-19 (''tendency which the presence of opposing

counsel has to inhibit the free and open discussion which an

attorney seeks to achieve at such interviews"); Frev v.

Department of Health and Human S e r v i ^ l06 F.R.D. 32, 36

(S.D.N.Y. 1985)("to permit the SSA to barricade huge numbers of

potential witnesses from interviews except through costly

discovery procedures, may well frustrate the right of an

individual plaintiff with limited resources to a fair trial and

18

035

deter other litigants from pursuing their legal remedies"). The

difficulty with these discussions is that they fail to identify,

perhaps because the issue has rarely been appreciated in light of

Supremacy Clause or federalism considerations, the precise

federal right impaired by application of the rule embraced by

Niesig. Federal courts unquestionably recognize a federal

litigant's right to unrestricted access to information, IBM v.

Edelstein, supra, but federal courts also fully embrace the view

that this "right" has limits which are, in part, defined by the

prohibition of DR 7-l04(A)(l). United States v. Hammad. 858 F.2d

at 837 ("lawyers are constrained to communicate indirectly with

adverse parties through opposing counsel"). Given New York's

interpretation of DR 7-104(A)(1) to encompass corporate employees

having knowledge of the subject of the lawsuit, Niesig v. Team I.

149 A .D.2d at 106, the apt task is to discern whether there is

any discrete federal interest requiring, in this court, a

different interpretation. More precisely, the issue is whether

the marginal restriction of access to information imposed by

Niesig burdens a federally protected right.

New York has answered the question forthrightly. In Niesig.

the court emphasized that informal interviews are not prohibited

by its interpretation of DR 7-104(A)(1). Counsel are free to

solicit informal interviews under the conditions set forth in the

disciplinary rule (consent of opposing counsel or as authorized

by law) and may speak with the corporate employee freely during

an authorized interview. Niesig v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d at 106-07.

In answer to the argument of Frev v. Department of Health & Human

19

036

Services, _supra (also made in Morrison v. Brandeis University,,

supra) that the presence of opposing counsel inhibits free and

open discussion, the New York court held that such an argument

"is likely to persuade only those who, contrary to the basic

axioms of the American legal system, believe that one-sided,

inquisitorial procedures are more effective than adversarial ones

in arriving at the truth." Niesia v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d 107. I

would venture even further; the simple presence of opposing

counsel at an informal interview of a corporate employee, or the

availability to corporate counsel of prior notice of the proposed

interview and the prior opportunity to consult with the employee,

cannot be deemed to inhibit free access to information except if

(1) it is assumed that the employee will not come clean and tell

the truth even if put to sworn testimony in a subsequent

deposition, (2) the employee will remain still notwithstanding

Title VII's prohibition of retaliation for statutorily protected

conduct, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a); Jenkins v. Orkin Exterminating

Co., Inc., 646 F. Supp. 1274 (E.D. Tex. 1986); United States v.

City of Milwaukee, 390 F. Supp. 1126 (E.D. Wis. 1975), and (3) it

is assumed that opposing counsel will violate the general

prohibition against obstructing access to evidence. See D.R. 7—

109(A)-(C); DR 7-l02(A)(6); C. Wolfram, Modern Legal Ethics.

§ 12.4.1, at 646-50 (1986) (collecting authorities); G. Hazard &

W. Hodes, The Law of Lawyering. 369-86 (1988 Supp.) These

assumptions are not warranted. Accordingly, it would be

improvident to predicate a differing federal rule upon such

20

037

tenuous conclusions, which are derived, necessarily, upon a

presumption of attorney bad faith and witness intransigency.

The other major objection articulated in Frey was the

asserted increased expense to individual plaintiffs formal

discovery procedures would entail. Frey v. Department of Health

& Human Services. 106 F.R.D. at 36. Application of the Niesiq

rule does not mean, however, that formal discovery procedures,

such as a deposition, need be employed in every case of an

employee interview. Niesiq only requires that the corporate

attorney be given the opportunity to exercise an option whether

to attend the interview, not that a deposition need be conducted.

In addition, the corollary of sensible application of Niesiq is a

rule which prevents corporate counsel from unreasonably

withholding consent to the interview whether in counsel's

presence or otherwise. Therefore, the marginal increased

expense, if any, accrues to the corporate party only. The court

in Niesiq assumed that increased expense would accrue to an

individual plaintiff, and discounted the matter. Niesiq v. Team

I, 149 A.D.2d at 107. I conclude that the financial

consideration is marginal, at best, and substantially ameliorated

by the provision of counsel fees for a successful plaintiff. 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k); See also, 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

The case of New York State Association for Retarded Children

v. Carey, 706 F.2d 956 (2d Cir. 1983), cert, denied. 464 U.S.

915, 104 S.Ct. 277 (1983) is not to the contrary. In that case,

the Second Circuit approved of a discovery order tailored to the

specific needs of the case which permitted plaintiff's counsel to

tour a governmental facility and interview the facility's

21 038

employees outside the presence of defense counsel. This case

involves a private corporate party. Niesiq. which purported to

apply N.Y. City 80-46, must also be taken to embrace the

statement in that City Bar opinion that "we do not address the

scope of DR 7—104(A)(1) where a governmental, as opposed to a

private, party is involved." N.Y. City 80-46 (Part II at last

sentence, fn.). See also, Mompoint v. Lotus Development

Corporation, 110 F.R.D. 414, 417-18 (D. Mass. 1986). Thus,

application of Niesiq to this litigation involving General

Electric contravenes none of the divergent interests applicable

to governmental entities. Indeed, if Niesiq was applicable to

the situation in Carey. it would require no more than that

defense counsel be given the option to join the tour.

In short, application of Niesiq would not lead to an

abridgement of any federally protected right, nor does it appear

that the rule of Niesiq would lead to an "[in]equitable" result.

-•R•— Foley & Co. ,_Inc, v. Vanderbilt. 523 F.2d at 1360 (Gurfein,

J., concurring). No good reason exists to create a differing

federal standard. Although it is not necessary to a decision, it

should be noted that Niesiq was endorsed as "a very well

ar^lculated and persuasive" holding in Cagquila v. Wyeth

Laboratories, Inc., 127 F.R.D. 653, 654 n.2 (E.D. Pa. 1989), and

that it was cited approvingly by a district court in this Circuit

for the proposition that violating DR 7-104(A)(1) will lead to

disqualification or sanctions. Papanicolaou v. Chase Manhattan

Bank,— N.A., 720 F. Supp. at 1085 n.ll. In Polvcast Technology

Corporation v._Uniroyal. Inc.P supra. which involved an issue of

former employee contracts, Niesiq was seen as consistent with the

22 039

court's interpretation of the "expanded comments" to ABA Model

Rule 4.2. Id. ___ F. Supp. at ___. The interests of federalism

and comity in matters such as these which is expressed in cases

recognizing the state's "substantial interest in regulating the

practice of law within the state . . . in the absence of federal

legislation" requiring different treatment, Sperry v. State of

Florida. 373 U.S. 379, 383-84 (1963), are served by recognition

of and deference to New York's interpretation of DR 7-104(A)(l).

Cf. Nix v. Whiteside. 475 U.S. 157, 165-66, 106 S.Ct. 988, 993

(1986)("a court must be careful not to narrow the wide range of

conduct acceptable under the . . . [Constitution] so

restrictively as to constitutionalize particular standards of

professional conduct and thereby intrude into the state's proper

authority to define and apply the standards of professional

conduct applicable to those it admits to practice in its

courts").8

8 There is an alternative mode of analysis which produces

the same result, even if information access may be said to be

impeded by application of DR 7-104(A)(1). For those districts

which have approved a local rule which incorporates New York's

Code of Professional Responsibility, there is no Supremacy Clause

problem created by enforcement of DR 7-104(A)(1) "because by its

incorporation into the local rules, [it] has become federal law."

United States v. Klubock. 832 F.2d 649, 651 (1st Cir. 1987),

aff'd en banc. 832 F.2d 664 (1st Cir. 1987)(equally divided

court). In this circuit, this principle would apply even in the

absence of a local rule. Hull v. Celanese Corporation. 513 F.2d

at 571 n.12. Accordingly, in the absence of a finding that the

state's interpretation of DR 7-104(A)(l) would lead to

inequitable results, there is no independent need to address the

Supremacy Clause issue. Indeed, the Ninth Circuit has rejected

the view that federal courts need to make an independent federal

interpretation of the Code in a district which formally adopts a

state ethics code. United Sewerage Agency of Washington County j_

Oregon v. Jelco Incorporated. 646 F.2d at 1342 n.l.

23 040

D. The Conflict of Interest Problem

Plaintiff's counsel places substantial emphasis on the

statement in Ni.esig that the corporate attorneys "are in

connection with the present litigation, holding themselves out as

attorneys for DeTrae's employees, as well as for DeTrae itself,

and absent a conflict of some sort, this is entirely proper."

149 A .D.2d at 101-02. The identification by plaintiff's counsel

of purported conflicts of interest, described in her letter and

quoted at the outset of this opinion, however, is entirely too

broad. m essence, it is argued that a prohibited conflict

arises whenever a corporate party takes any personnel action

against an employee sought to be interviewed by plaintiff.

It is unquestionably true that, in litigation involving

multiple representation of a corporate and individual client,

where both are parties to an action or potential parties, a

conflict of interest may arise requiring disqualification of

counsel. Dunton v. County of Suffolk. 729 F.2d 903, 907-10 (2d

Cir. 1984), amended 748 F.2d 69 (2d Cir. 1984). Compare Coleman

~ — Smith, 814 F.2d 1142 (7th Cir. 1986). Plaintiff does not

allege, however, that any of the individuals who have an asserted

conflict of interest are currently engaged in litigation against

General Electric, nor indeed is there an allegation that these

individuals are currently engaged in any adversary disciplinary

process administered by General Electric's personnel department,

substantially related to this litigation. Cf. Gluek v. Jonathan

— qan> Inc-' 653 F*2d 746' 749 (2d Cir. 1981); Cinema S. T.M. „

24

041

Cinerama. 528 F.2d 1384, 1386 (2d Cir. 1976). N.Y. State 580

(1987) .

The standards governing conflict of interest are contained

in D.R. 5—105(A),(C) of the Code of Professional Responsibility.

There is no basis to conclude that the standards of those

disciplinary rules are invoked by the simple existence of a past

personnel action taken against a particular employee whom

plaintiff's counsel wishes to interview. The language in Niesig

that corporate counsel is holding himself out as an attorney for

the corporate employee is, perhaps, unfortunate. A more precise

formulation would be that GE's corporate counsel is, by asserting

the interests contained in D.R. 7-104(A)(1) as interpreted in

Niesig. holding himself out as an attorney for the corporation,

and that effective representation of the corporate entity itself

cannot, consistent with Niesig1s rationale, occur without an

entreaty to corporate counsel which gives him the opportunity to

be present during the requested informal interview. It is the

effective representation of the corporation itself which Niesig

seeks to vindicate, not representation of any individual

corporate employee. Accordingly, plaintiff cannot avoid

application of the Niesig rule on a record as scanty as this by

reference, simply to an asserted personnel action taken against a

corporate employee sought to be interviewed.

25

042

CONCLUSION

Plaintiff's motion for permission to conduct ex parte

interviews with General Electric employees is denied. General

Electric's motion for a protective order pursuant to Fed. R. civ

P. 26(c) is granted consistent with this opinion. Consistent

with Nieseq v. Team I. 149 A.D.2d at 106, it is not proper to

contact ex parte an employee of General Electric for the purpose

of eliciting from such employee information which relates to the

subject of this lawsuit. See Stahl, Ex Parte Interviews with

Enterprise Employees: A Post-Upiohn Analysis. 44 Wash. & Lee L.

Rev. 1181, 1227 (1987).

SO ORDERED.

UNITED STATES MAGISTRATE

Dated: Rochester, New York

March j , 1990

26

043