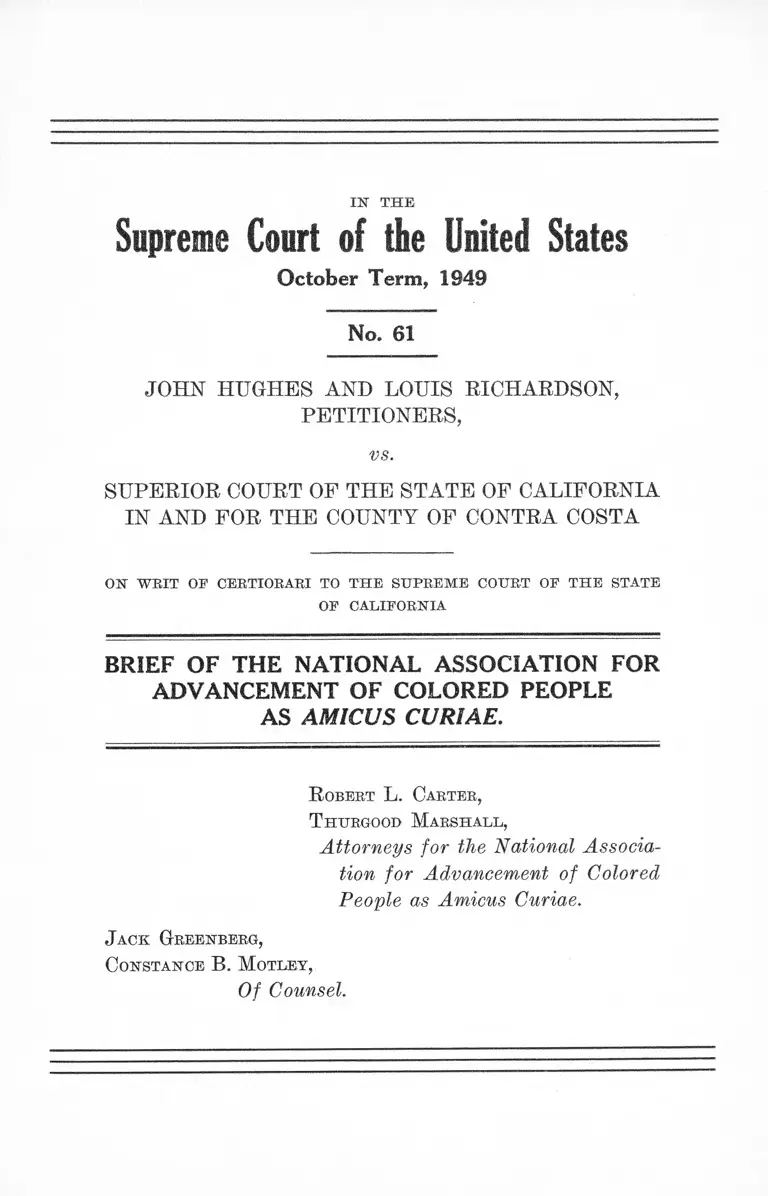

Hughes v. Superior Court of California in Contra Costa County Brief of the NAACP Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hughes v. Superior Court of California in Contra Costa County Brief of the NAACP Amicus Curiae, 1949. 9e14c597-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/caeb144c-9705-4153-82b9-86e9da8c4748/hughes-v-superior-court-of-california-in-contra-costa-county-brief-of-the-naacp-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term* 1949

No. 61

JOHN HUGHES AND LOUIS RICHARDSON,

PETITIONERS,

vs.

SUPERIOR COURT OP THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF CONTRA COSTA

ON WBIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE

OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE.

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for the National Associa

tion for Advancement of Colored

People as Amicus Curiae.

J ack Greenberg,

C onstance B. M otley,

Of Counsel.

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

O cto b e r T erm , 1949

No. 61

J o h n H ughes and L ouis R ichardson ,

P etitio ners ,

vs.

S uperior C ourt op t h e S tate op California

IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OP CONTRA CoSTA

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE

OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE.

Statement of Interest of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is an organization which for the past forty

years has devoted its efforts and energies toward the im

provement of conditions affecting Negroes in the United

States and throughout the world. It has worked unceasingly

towards the eradication of racial discrimination which has

kept the Negro from obtaining full citizenship.

One of the main factors which has kept the Negro in a

status of unequality, is the wholesale discrimination in the

economic field which has severely limited his opportunities

to earn a decent livelihood. The National Association for

2

the Advancement of Colored People has consistently sought

to eliminate these practices and has been in the forefront

of the fight for state and federal fair employment practice

legislation.

Although we are opposed to what has been alleged to be

the ultimate objective of the petitioners in this action—-

proportional or quota hiring of Negroes—we believe that

the controlling and primary issue here is whether the right

to peacefully picket in order to improve the economic oppor

tunities for Negroes is a right which has the protection of

the Federal Constitution. This, we submit, is the basic issue

which this case presents, and it is for this reason that we are

filing this brief as amicus curiae.

Permission has been secured from all parties for the

filing of this brief, and letters granting permission have been

filed in the Clerk’s office.

Statement of the Case.

On May 20,1947, Lucky Stores, Incorporated, filed in the

Superior Court of the State of California, in and for the

County of Contra Costa, a verified complaint for injunction

naming petitioners as defendants (R. 1). The petitioners

demanded that the corporation “ agree to hire Negro clerks,

such hiring to be based upon the proportion of white and

Negro customers patronizing its stores” (R. 4). Be

cause of the refusal of respondent to comply with their

demand, petitioners picketed “ Lucky’s” Canal Street

Store in the City of Richmond, State of California.

“ Lucky” alleged that unless this picketing was restrained

respondent would suffer irreparable damage and be forced

to close the store in question and that such picketing was

an infringement on its right to do business and required

“ Lucky” to violate a contract with a designated Clerk’s

3

Union with which it had an exclusive collective bargaining

contract.

On the same day, May 20, 1947, the Superior Court is

sued a temporary restraining order restraining, among

other things, petitioners from picketing Lucky Stores for

the purpose of compelling it to hire a number of Negro

clerks proportionate to the number of Negro customers

(ft. 34).

On May 26, 1947, a hearing was had on an order to show

cause and the matter was submitted to the judge of the re

spondent Superior Court. The Court determined that

“ Lucky” was entitled to a preliminary injunction, and on

June 5, 1947, the trial court made and issued its formal

order granting the preliminary injunction in substantially

the same language as the temporary restraining order

(E. 34).

On June 21, 1947, citations issued from the trial court

to petitioners ordering them to show cause why they should

not be punished for contempt for violating the preliminary

injunction. On June 23, 1947 the Court found the two peti

tioners guilty of contempt and adjudged that they be im

prisoned for two days and pay a fine of twenty dollars. A

ten day stay of execution was granted (B. 35-36). On the

same day-—June 23,1947—-a petition for certiorari was filed

in the District Court of Appeals, First District, Division

One, State of California (R. 36), and the writ of certiorari

was granted (R. 43).

On November 20,1947, the District Court of Appeals, all

three justices concurring, issued judgment holding that the

preliminary injunction was beyond the jurisdiction of the

trial court since it violated petitioners ’ constitutional rights

and the judgment of contempt was annulled (R. 61).

4

Respondent Superior Court thereafter petitioned the

Supreme Court of the State of California for hearing, and

such petition was granted. On November 1, 1948, the Su

preme Court of the State of California issued its opinion

and made its decision that the judgment of contempt be af

firmed. Four justices concurred in the majority opinion

and two justices dissented (R. 90-111). Petitioners peti

tioned for a rehearing by the State Supreme Court, and on

November 29, 1948, the petition for rehearing was denied,

again with two justices dissenting (R. 111).

The Question Presented.

M ay P ic k e tin g to S ecu re G re a te r E conom ic A d v a n ta g e s fo r

N egroes b e E n jo in ed B ecause th e O b jec tiv e is C on sid ered

Illeg a l in th e A b sen ce o f a S how ing o f a C lea r a n d P re se n t

D a n g e r o f S u b stan tiv e H a rm W h ich th e S ta te is E n title d to

P ro h ib it.

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The action of the Court results in an unconstitu

tional suppression of free speech.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press are among

the indispensable characteristics of a democratic form of

government and are rightly considered the most precious

and cherished freedoms of our society, the sine qua non of

our way of life. Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 327;

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516. Since Thornhill v. Ala

bama, 310 U. S. 88, there has been no question but that

peaceful picketing was an exercise of the right to freedom

of speech and as such was secure against governmental

5

prohibition. Thus interference with petitioners’ actions in

this case was a violation of the guarantee of freedom of

speech contained in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Fed

eral Constitution.

Courts have no power to make a substantive examina

tion of the pickets’ purposes and decide, as a result of such

examination, whether the picketing is permissible or must

be restrained. See Thornhill v. Alabama, supra; New Negro

Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Go., 303 U. S. 552. Courts may

merely determine whether the picketing is protected under

the First or Fourteenth Amendments, not whether it is

proper or meritorious. Almost without exception, as long

as the picketing is peaceful, it is protected under the Con

stitution to the same extent as any other exercise of free

speech. Thornhill v. Alabama, supra; Carlson v. California,

310 U. S. 106; American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312

U. S. 321; Cafeteria Employees Union v. Angelos, 320 U. S.

293. Even such cases as Carpenters & Joiners Union v.

Ritter Cafe, 315 U. S. 722, held that peaceful picketing may

not be prevented so long as the “ sphere of communication”

is “ directly related to the dispute.” No such question

arises here. The picketing was at the premises directly in

volved in the dispute. Neither has any question been raised

concerning the truth of the signs the pickets carried, nor

whether the picketing was in fact peaceful which was the

problem in Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor

Dairies, Inc., 316 U. S. 287.

The clear and present danger concept is the most palat

able limitation upon freedom of speech. It has been

variously defined. However, no matter what interpretation

of the doctrine we employ, petitioners’ actions were not

such as to warrant the restriction herein imposed.

1. The record demonstrates that there was neither a

clear nor present danger of public disturbance.

6

2. The Court did not even imply that there was either

a clear or present danger of petitioners instituting hiring

practices inimical of the public welfare.

3. Even if such legislation were constitutional, there

was no legislative finding that petitioners were creating a

substantive evil which the state has a right to prevent.

Cf. Dunne v. United States, 138 F. (2d) 137, 145 (C. C. A.

8th, 1943).

Thus, whether the proscribed area be defined in any of

the three ways described above or in any reasonable man

ner that comes to mind, petitioners’ expressions still stand

under the constitutional protection guaranteeing freedom

of speech.

II.

Assuming that such a consideration were relevant,

petitioners were not advocating an unlawful result.

The purposes for which the picketing was conducted

were lawful. The picketing took place in the City of Rich

mond, County of Contra Costa, which has a Negro popu

lation of more than ten thousand. As elsewhere in the

United States, employment opportunities for Negroes in

Contra Costa are seriously circumscribed by tradition and

prejudice, a situation which promises to become more acute

in any possible economic recession which we may face in the

future. Already, in Richmond, unemployment among the

Negro population is greatly disproportionate to unemploy

ment among the whites.

Petitioners, motivated by the quite understandable de

sire to improve their economic lot, undertook to picket,

urging that respondent afford greater opportunity for em

7

ployment to Negroes by abolishing discrimination based

upon color in their hiring practices. They picketed, carry

ing signs which stated:

LUCKY WON’T HIRE NEGRO CLERKS IN

PROPORTION TO NEGRO TRADE—DON’T

PATRONIZE

The Court, interpreting “ proportionate” as a math

ematical word of art, concluded that petitioners were ad

vocating employment of Negro clerks in strict ratio to

whites, probably determined by a census of Richmond’s

growing and variable population. In Cafeteria Employees’

Union etc. v. Angelos, supra, this Court adopted a more

reasonable standard for interpreting the language of labor

disputes. There it was stated:

“ To use loose language or undefined slogans that

are part of the conventional give-and-take in our

economic and political controversies—-like ‘unfair’

. . . is not to falsify facts.”

Petitioners’ signs, seen against the background of facts,

and in the light of this Court’s standard of interpretation

takes on a meaning more hortatory and less artificial, which

was the meaning undoubtedly conveyed to those living in

the context of the controversy. They were simply interested

in increasing employment opportunities for Negroes and

eliminating discrimination against them, something quite in

accord with the public policy of the State of California,

Jam.es v. Marinship Corp., 25 Cal. (2d) 721, 155, p. 2(d)

329 (1944) and Williams v. International etc. of B oiler-

makers, 27 Cal. (2d) 586, 165 p. 2(d) 903 (1946), and of the

United States, New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery

Company, 303 U. S. 552.

The only objection to the picketing was the allegation

that the pickets urged hiring of Negroes on a proportional

8

or quota basis and that such hiring would effect an inverse

racial discrimination contrary to the policy of the State of

California as determined in James v. Marinship Corp., supra.

As stated at the outset, we, too, oppose a proportional or

quota system of hiring and feel that persons must be given

job opportunities in accordance with ability rather than in

accordance with race or color. But the question is not whether

petitioners’ aims were good aims (granting that the Court’s

interpretation of the signs was correct), but whether the

state’s action was constitutional. Except for the quota or

proportional aspects of the case, the factual situation is

similar to that presented in New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary

Grocery Co., Inc., supra, where this Court stated at page

561:

“ The desire for fair and equitable conditions of

employment on the part of persons of any race, color,

or persuasion, and the removal of discriminations

against them by reason of their race or religious be

liefs is quite important to those concerned as fair

ness and equity in terms and conditions of employ

ment can be to trade or craft unions or any form of

labor organization or association. Race discrimina

tion by an employer may reasonably be deemed more

unfair and less excusable against workers on the

ground of union affiliation.”

III.

The cases upon which the Court relies are clearly

distinguishable.

Both the Marinship ease and the Williams case, upon

which the Court relies, are clearly distinguishable. James

v. Marinship Corp., supra, concerned a union which refused

to admit Negroes and which also had a monopoly of jobs

in a certain area. The Court held that a union with closed

9

shop prerogatives may not maintain a closed, discrimina

tory union. Williams v. International etc. of Boilermakers,

supra, held similarly, however not limiting itself to the case

of a monopoly of a geographical area. It held that a single

closed shop was enough to justify the Court’s intervention

against discrimination. Secondly, neither the question of a

closed shop nor a closed union is here involved. The Court,

still assuming that the petitioners desire to introduce an

arbitrary system of hiring, unrealistically analogizes the

Negro race to a closed union. To compare a racial group

desirous of acquiring a fair share of jobs available on a

non-discriminatory basis, to an association organized for

economic purposes and capable of including members of

all races, ignores the fundamental social inequities which

precipitated this dispute.

Conclusion.

W h erefo re fo r th e reasons herein a b o ve

m en tion ed it is re sp e c tfu lly su b m itted th a t th e

ju d g m en t o f th e S uprem e C ourt o f C alifornia

sh ou ld b e reversed .

R obert L . Carter,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for the National Associa

tion for Advancement of Colored

People as Amicus Curiae.

J ack Greenberg,

C onstance B . M otley,

Of Counsel.

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300