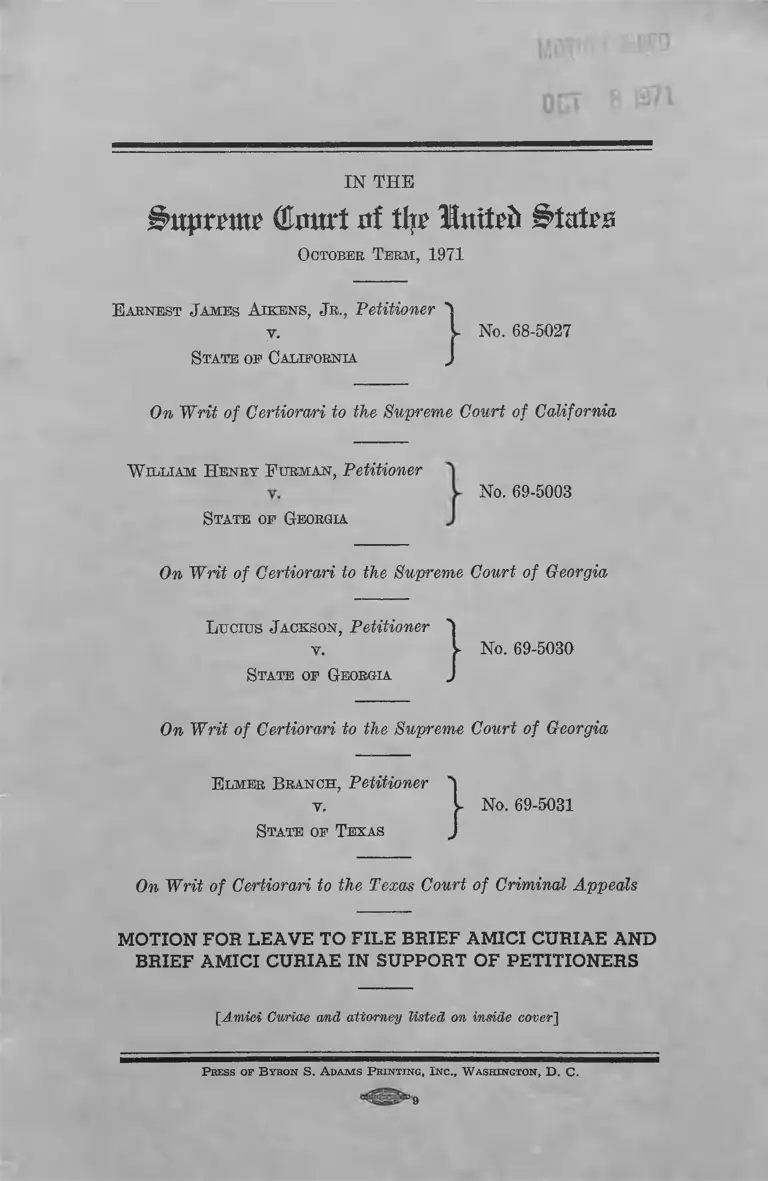

Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 8, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Aikens v. California, Furman v. Georgia, Jackson v. Georgia, and Branch v. Texas Motion for Leave to File Brief Amici Curiae and Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 1971. 155e6920-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb15c84a-756e-4152-8a2b-9c55eda220a7/aikens-v-california-furman-v-georgia-jackson-v-georgia-and-branch-v-texas-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amici-curiae-and-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme ©mart 0! Up United States

October Term, 1971

E arnest J ames A ikens, J r., Petitioner

y. V No. 68-5027

State oe California

J- No

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California

W illiam H enry F urman, Petitioner

State of Georgia

No. 69-5003

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Lucius J ackson, Petitioner

v.

State of Georgia } No. 69-5030

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

E lmer Branch, Petitioner

y, V No. 69-5031

State of Texas }

On Writ of Certiorari to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE AND

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

[Amici Curiae and attorney listed on inside cover]

P ress of B yron S. Adams P rinting, Inc., W ashington, D. C.

9

H on. E dmund 6 . Brown

H on. David F . Cargo

H on. E lbert N. Carvel

H on. Michael Y. D iSalle

H on. P hillip H. H ope

H on. Theodore B. McK eldin

H on. E ndicott P eabody

H on. Grant Sawyer

H on. Milton J . Shapp

By Michael V. D i Salle

425 - 13th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202)-393-3300

Attorney for Amici Curiae

October, 1971

INDEX

Page

M otion for L eave to P ile B rief A m ici C u r ia e ..............1-M

B rief A m ici Curiae in S upport of P e t it io n e r s ............ 1

Interest of Amici C uriae........................................... 1

Summary of Argum ent............................................. 2

Argument ............ 3

The Death Penalty Is a Cruel and Unusual Punish

ment Prohibited by the U. S. Constitution....... 3

Conclusion .................. 16

IN THE

i>uprrmr Court of tijr luitrd Stairs

October Term, 1971

E arnest J ames A ikens, J r., Petitioner

y.

State of California

No. 68-5027

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California

W illiam H enry F urman, Petitioner

y.

State of Georgia

No. 69-5003

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Lucius J ackson, Petitioner ")

v. V No. 69-5030

State of Georgia J

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

E lmer Branch, Petitioner

y.

State of Texas

No. 69-5031

On Writ of Certiorari to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

The movants hereto, Hon. Edmond G, Brown, former

Governor of California, Hon. David E. Cargo, former

Governor of New Mexico, Hon. Elbert N. Carvel,

2-M

former Governor of Delaware, Hon. Michael V.

DiSalle, former Governor of Ohio, Hon. Philip H.

Hoff, former Governor of Vermont, Hon. Theodore B.

McKeldin, former Governor of Maryland, Hon.

Endicott Peabody, former Governor of Massachusetts,

Hon. Grant Sawyer, former Governor of Nevada and

Hon. Milton J. Shapp, Governor of Pennsylvania,

hereby respectfully move for leave to file the attached

brief amici curae in this case The consent of the re

spondent, the State of Georgia, the respondent, the

State of California, and the respondent, the State of

Texas, was requested but, was refused by all.

The interest of the foregoing individuals in this case

arises from the fact that they are all presently or were

formerly Governors in states where the death penalty

is authorized by law, and in their official capacity as

governors of their varied states have had intimate

torturous experience with the death penalty.

While scholarly research and judicial logic can ex

plore the application of theoretical bounds of the Con

stitution to the concept of capital punishment, these

amici are uniquely qualified through personal experi

ence to advise the court of the cruel and unusual nature

of the death penalty. Each of these men has been in

the position of sitting in final human judgment over the

life of another human being; more final than that of

the sentencing judge who had the knowledge that execu

tive clemency might relieve him of the burden of taking

another man’s life; more final indeed, than the decision

of this honorable Court. Each of these amici have wit

nessed the cruelty of the years-long suffering imposed

upon the condemned, and the unusualness of the pun

ishment in its discriminatory application to the poor,

the ignorant, and the unpopular. Each can provide an

3-M

additional dimension to the question now before the

court which counsel can only begin to suggest.

The brief of amici curiae is timely presented.

Although time for filing briefs of the parties has

passed, this Court has postponed consideration of these

cases pending appointment of two additional Justices.

The gravity of the question before the court, the finality

(but for executive clemency) of its decision in these

cases, and the fact that the court will neither be incon

venienced nor delaj^ed due to the postponement of

argument and decision in these cases, all suggest the

propriety of the granting of this motion and the

consideration by this Court of the brief amici curiae.

W herefore movants respectfully request that this

honorable Court grant leave to file the attached brief

Amici Curiae in support of petitioners.

Respectfully submitted,

H on. E dmund Gf. B eown

H on. D avid F . Cargo

H on. E lbert N. Carvel

H on. M ichael V. D i S alle

H on. P h il ip H. H ope

H on. T heodore R. M cK eldin

H on. E ndicott P eabody

TIon. Grant S awyer

H on. M ilton J. S happ

B y M ichael Y. D i Salle

425 - 13th Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20004

(202)-393-3300

Attorney for Amici Curiae

October, 1971

IN THE

^upvnm (Emirf of tlfr United

October Term. 1971

E arnest J ames Aikens, J r., Petitioner 'J

y. I No. 68-5027

State of California J

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California

W illiam H enry F urman, Petitionerv.

State of Georgia

No. 69-5003

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Lucius J ackson, Petitioner 1

Y. I- No. 69-5030

State of Georgia J

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

E lmer Branch, Petitioner 1

v. L No. 69-5031

State of Texas J

On Writ of Certiorari to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The subscribers to this brief are men who in their

official capacity as Governors of their various states,

2

have had intimate, torturous experience with the death

penalty. They are Hon. Edmund G. Brown, former

Governor of California, Hon. David E. Cargo, former

Governor of New Mexico, Hon. Elbert N. Carvel,

former Governor of Delaware, Hon. Michael Y. Di-

Salle, former Governor of Ohio, Hon. Philip H. Hoff,

former Governor of Vermont, Hon. Theodore R. Mc-

Keldin, former Governor of Maryland, Hon. Endicott

Peabody, former Governor of Massachusetts, Hon.

Grant Sawyer, former Governor of Nevada and Hon.

Milton J. Shapp, Governor of Pennsylvania.

Not until one has watched the hands of a clock mark

ing the last minutes of a condemned man’s existence,

knowing that he alone has the temporary Godlike

power to stop the clock, can he realize the agony of

deciding an appeal for executive clemency.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The death penalty is not a deterrant to those who

would willfully take the life of another. History has

repeatedly shown that people who actually witnessed

public legal executions were often those who were later

convicted and executed for similar offenses. The con

verse is also true. In places where the death penalty

has been abolished, there has been no rise in the num

ber of willful homicides committed.

Capital punishment is a relic of barbarism, and the

sadism of earlier societies’ methods of execution is

nonetheless present, even though modern “ more hu

mane” methods may dispatch the convicted more

quickly. The life-for-a-life principal of penology satis

fies nothing but a lust for revenge which is degrading

to the fabric of our society.

3

Legal execution is unconstitutionally cruel because

it leaves no room for redemption and rehabilitation and

subjects the condemned to years of terror on death

row, until reprieve after reprieve, false hopes raised

and dashed, and witness to others on death row going

to a final doom which is uncertain for them only as to

date, finally drives the condemned beyond the point of

madness.

The punishment of execution is unusual in its appli

cation because among those found guilty of willfull

homicide, it is generally the poor, 'the ignorant and the

politically unpopular who suffer its consequences. In

1965, with 9,850 homicides committed, there were seven

executions; in 1966, one, and since then, none. Those

selected for execution appear chosen at random from

among the unprivileged, with no rational method of

applying the death penalty to those who, by legislation,

are subject to it.

ARGUMENT

The Death Penalty Is a Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Prohibited by the U.S. Constitution

Generally, the people who sit in death row waiting

to know whether the Governor will permit them to

live or to die, follow a uniform pattern. They are

men and women who generally have not had the finances

necessary to enlist the services of the peculiarly tal

ented counsel so essential in manning this type of

defense. They are generally unschooled, often illiter

ate, many times mentally inadequate, and frequently

the result of local hysteria which cries for a vengeance

that is extremely fleeting. They are the exception

rather than the ride. It seems that somewhere, some

one believes that the execution of one man among the

4

hundreds that are charged with willful homicide will

serve as an example or a deterrent to society. Is it a

deterrent?

Three Presidents of the United States had been

assassinated before John Fitzgerald Kennedy was

shot down in Dallas. All of their assassins died.

Booth, who shot Lincoln, was killed while trying to

escape his pursuers; his accomplices were hanged.

Garfield’s assassin, a disappointed office seeker, was

executed. So was the anarchist who shot McKinley.

Did this deter the men who took pot-shots at Theodore

Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, or Harry S. Truman ?

All of the previous examples did not deter Lee Harvey

Oswald. The fact that Oswald was killed by Jack

Ruby should have served to satisfy those who were

seeking vengeance. Instead, the killing of Oswald by

Jack Ruby produced intense indignation on the part

of our citizens. But if we say that Ruby as an in

dividual should not seek revenge, should we, as a

people, seek it collectively?

To emphasize the futility of the death penalty as

a deterrent, we might briefly review the case of Charles

Justice. Justice was sentenced in 1902 to the Ohio

State Penitentiary after a cutting scrape. He was

assigned as a trusty to the housekeeping duties of

the death house. In those days, the electric chair was

considered inefficient. Since it was too large for the

small, nervous type of prisoner, it would cause him

to squirm in his seat and cause the electrodes to make

imperfect contact. As a result, the powerful current

would arc between the electrodes and the doomed man’s

body, causing flesh burns and an unpleasant odor

which discommoded the witnesses and officiating rep

resentatives of the state. Charles Justice corrected

5

this deficiency by designing iron clamps which are still

in use. They immobilized the limbs of the condemned

man during his death reflexes and thus made for a

neater execution.

For his service to Ms state, Charles Justice was

granted extra time off and was paroled in April, 1910.

In November of the same year, Justice returned to

the penitentiary, the charge; murder in the first degree.

On October 27, 1911, undeterred Charles Justice died

in the electric chair he had made more lethal, im

mobilized by the clamps he had invented.

How cruel is cruel? Capital punishment is a relic

of barbarism. The Lord Chief Justice of England

wondered if the death penalty might not be a trifle

severe in view of the prisoner’s age. The trial judge

argued against mercy on the grounds that William

York’s punishment would be an example deterring

others from a life of crime. So William York was

hanged for stealing a shilling from the man to whom

he was apprenticed. He was ten years old. The place

was London. The time was 1748.

Britain has come a long way along the road to civ

ilization in the two centuries since the hanging of

William York. In October 1965, not only the House

of Commons, but the usually stuffy House of Lords,

with a surprising two-to-one majority, voted to abolish

the death penalty for a test period of five years,

which will probably prove permanent. Tins enlight

ened legislation, although still behind most of Western

Europe’s, is far ahead of the United States’, and

marks a definite global trend.

Capital punishment is a relic of barbarism, it is

immoral, it usurps for society the exclusive privilege

of natural laws, it is futile because it does not deter

6

the homocidal criminal, and its finality precludes any

possibility of correcting an error.

The eye-for-an-eye, life-for-a-life concept of pen

ology is obviously based on the degrading principle

that society, in punishing the criminal, is seeking re

venge rather than justice. The strong strain of sadism

that rims through a vindictive .society’s clamor for a

wrongdoer’s blood is evident in the fact that until

rather late in this century (in the Western world,

at least) the execution of the condemned has been some

thing of a spectator sport.

The executioners of the Far East have been far

more inventive in their spectacular cruelty than any

20th Century Western country, with the possible ex

ception of Nazi Germany. The Chinese, of course, have

long been recognized as leaders in the field, with their

boiling in oil, leisurely dismemberment (The Hundred

Slices) and similar refinements. The Mogul, emperors

of India, however, should be recognized for their in

genuity in dispatching criminals as well as for their

building of such monuments as the Taj Mahal. Im

palement, for instance, was very popular (except with

the victims) in 17th Century Delhi.

The man to be put to death by impalement (possibly

for stealing a mango or a handful of roasted chick

peas from the Emperor Aurangzeb’s palace kitchens)

was paraded naked past the eager spectators to the

killing grounds, where a sharpened stake of heat-

tempered bamboo had been erected. Two men, each

holding one of the prisoner’s bound arms, would lift

him clear of the ground while a third separated the

buttocks so that when the culprit was lowered briskly,

the bamboo lance would penetrate the rectum as far

as the sigmoid flexure. The executioners could then

7

step back and join the delighted crowd in watching

the dance of death as the screaming' wretch writhed

and pirouetted on his tiptoes in an effort to stay the

inexorable progress of the murderous bamboo through

his vitals. When sheer exhaustion and loss of blood

finally forced the thief to his knees, the point of the

bamboo stake pierced his heart and the show was

over. Justice—or something-—had been done.

The early Siamese did pretty well in the way of

spectacular capital punishment by throwing their

criminals to the crocodiles. This possibly gave the

Romans the idea of throwing Christians to the lions,

although the Romans got better exposure by building

huge stadia for their lionization carnivals. This may

have been an improvement over the earlier Roman form

of capital punishment by crucifixion (in itself an im

provement over the crude Jewish practice of lapidation,

with no strictures as to who was to throw the first

stone), but it was a failure as a deterrent to the spread

of Christianity.

The ancient Greeks, with their more temperate and

philosophic civilization, did not feel it necessary to

borrow from the annals of Oriental cruelty in ex

terminating their undesirables and nonconformists. A

quiet cup of hemlock did away with the lawless and

the contumacious without fuss, feathers or cheering

crowds.

The Greek example, however, did not deter the rest

of Europe from linking justice with sadism. Spain

during the Inquisition made notable advances in the

field of cruel and unusual punishment with the rack,

the wheel, flaying alive and burning at the stake, al

though the popularity of auto-da-fe spread to other

countries. Even today, although Spaniards have

8

managed to transfer most of their hostilities to the

brave bulls, the Franco government, perhaps out of

sentimental longing for the good old days, still retains

garroting as an official form of capital punishment.

Only a few years ago—August 17, 1963, to be exact—-

two men found guilty of terrorist bombing were

garroted in Madrid. Awakened at dawn to be fitted

with adjustable steel collars, they were slowly strangled

to death. The collars were tightened until eyes bulged

and faces purpled, tightened still more until the wind

pipe was collapsed. The two men were then given the

coup de grace by the points of the tightening screws

emerging cleverly from inside the backs of the collars

to pierce the cervical vertebrae and crush the spinal

cord.

Decapitation, once a popular form of capital pun

ishment throughout the world, is now used sparingly

despite an attempt by the Nazis to revive it during

their brief but memorable rule of Schrecklichkeit. It

was originally done by hand—wit h scimitar or cleaver

in the East, with broadsword or ax in the West.

Punitive head chopping was legally automated, how

ever, as early as the 18th Century. The guillotine

came into use in the early years of the French Revo

lution. Curiously, this lethal instrument, which be

came a symbol of the Reign of Terror, was originally

suggested as a humane method of obviating the suf

fering attendant to executing the death penalty. Dr.

Joseph Gruillotin, a professor of anatomy appalled

by the bloody extravagances of the French Revolution,

carried on a campaign to humanize necessary killing,

but resented the fact that his name was attached to

the killing machine which he did not invent. Actually,

the first “ guillotine” was devised by Dr. Antoine

9

Louis, and was called, by contemporaries in Ms honor,

a Louisette. I t consisted—and still consists—of a

trapezoidal knife weighing more than a hundred

pounds, which drops ten feet between guide rails and

slices on the bias through the neck of the condemned

man who lies prone beneath it, Ms head immobilized

by stock-like clamps. The severed head drops into a

suitable container, while the body is rolled into a

basket.

It was Dr. Gfuillotin’s theory that this method of

putting a man to death was the most compassionate,

because the victim would feel nothing except perhaps

a brief sensation of cold at the nape of his neck.

Whether there is any intervening pain or the reali

zation on the part of the severed head of its impossible

position has never been confirmed or denied by any of

the victims.

Executions by guillotine took place in a public

square in Paris as late as 1939. The scaffolding and

the weighted knife would be erected the night before,

and although the accused died at dawn, there were al

ways crowds on hand to be edified, if not deterred

from crime, by the spectacle of the spurting carotid

arteries, the ghastly surprised expression on the de

tached face, the reflex flopping of the headless body.

Whether or not there was any appreciable deterrent

effect, the grisly ritual is today privately performed

behind the walls of La Saute prison on the Left Bank

of the Seine.

Public hangings were abolished in England in 1868.

At that time capital crimes numbered only a dozen,

down from 200 in 1820. It is likely that the public

spectacle was discontinued then because a royal com

mission had reported two years earlier that the death

10

penalty, even when witnessed by potential criminals,

was no deterrent. The commission’s report found that

of the 167 persons executed in 1866, 164 had previously

watched a hanging. This is not surprising, as the

public executions used to attract huge erowuls, and

the crowds would attract dozens of pickpockets intent

on plying the very trade for which the center of at

traction was being hanged.

Public hangings persisted in America beyond the

cutoff date in England, particularly in the Ear West.

The more spectacular forms of legal brutality were

not practiced, however, even in the earlier Colonial

days. There were, of course, occasional unofficial and

nonintegrated autos-da-fe in some of the deeper parts

of our Deep South, a practice that has carried over

well into this century. But even the witches of Salem

were not burned at the stake; they were decently

hanged.

Crimes calling for the death penalty, however, were

almost as numerous in Colonial America as in con

temporary England. In 1636 hanging was the penalty

in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for witchcraft, idol

atry, blasphemy, assault in anger, murder, sodomy,

buggery, statutory rape (the death penalty was op

tional for forcible rape), perjury in a capital case

and rebellion. The Old Dominion of Virginia ranked

the degree of criminality according to race, color and

current condition of servitude. Seventy crimes were

listed as capital for Negro slaves, but only five for

whites.

It was inevitable that an emerging nation like the

United States, aspiring to world leadership in science

and invention and the practical application thereof,

would sooner or later abandon hanging for a modern,

11

efficient, scientific and more “ humane” method of legal

murder. In 1880 the state of New York abolished

the gallows in favor of a newfangled “ electric chair.”

Thirteen years later a man named Kemmler lost his

court battle to have the new monster declared uncon

stitutional as “ cruel and unusual punishment,” and

became the first man to be punished electrically for

his misdeed—an ax murder. The contraption was a

success technically, since it killed Kemmler, but the

humanity of the experiment was doubtful. Either the

machine misfunctioned or the executioner did some

thing wrong. There was considerable searing of flesh

and the human guinea pig apparently died in agony.

Techniques have been improved in the 70-odd years

since, and it is now generally agreed that death by

electrocution is practically painless. While patho

logists still argue over the exact mechanics of death

by electricity—some believe the heart muscles are par

alyzed; others are just as certain that paralysis of

the respiratory centers causes death by asphyxia—

most of them concede that the victim loses conscious

ness almost instantly. The tremendous electrical surge

raises the temperature of the body to the boding point

and sears the brain to insensibility in a fraction of a

second. The jerking and writhing that nauseate wit

nesses are not signs of a death struggle but purely re

flex reactions of the muscles to an electrical impulse.

An expert hanging is also supposed to extinguish

consciousness at the end of the drop. The snap of

the rope grown taut theoretically breaks the neck and

severs the spinal cord. The frantic kicking, the jerk

ing arms, the ejaculation of sperm in men, are all un

conscious nervous reflexes. Of course there have been

many bungled hangings—defective traps, ropes that

12

broke, inexpert knots that merely choked the man to

death. There is a record of an early English hanging

of a half-starved female criminal who dropped through

the trap and dangled at the end of the rope, eyes

bulging with dread, because she was not heavy enough

—she was a small 12-year-old girl—for the fall to

break her neck. The hangman had to go down the

13 steps, grab her legs and add his weight to hers to

carry out the sentence.

In 1921 the Nevada state legislature came up with

the latest contribution to the fine art of killing crim

inals. It was not only scientific, quick and efficient;

it introduced a new ‘£humane” note: I t would elimi

nate the torture of apprehension. Poison gas would

be introduced without warning into the cell of the

condemned man while he was asleep. He would die

peacefully, and nobody’s conscience need be disturbed

by witnessing a death struggle. When a murderer

named Gee Jon was sentenced to this new-style death

three years later, it happily occurred to someone that

the bars of Gee Jon’s cell could hardly be expected

to contain the lethal gas intended exclusively for Gee

Jon’s gentle extinction. Bather than risk exterminat

ing the entire population of the penitentiary, instead,

the penal authorities postponed the historic execution

until a special gas chamber could be built.

Mne states besides Nevada now poison their capital

criminals with gas. The best-known gas chamber of

them all is California’s, perhaps because Caryl Chess

man died there after a legal fight that lasted 12 years.

Chessman had a long record of charges against him,

but the one for which he was finally executed was

that of forcing a girl to move from one car to another

at gunpoint. This is technically kidnaping in Cali-

13

fornia and is punishable by death under California’s

“ Little Lindbergh Law.”

Because there were many newsmen among the 60

witnesses who came to San Quentin for Chessman’s

execution, millions read descriptions of how a man dies

by inhaling poison gas. I t is a death not much dif

ferent, they found, from hanging or electrocution.

Looking through glass panels of the hermetically

sealed gas chamber, the reporters saw the doomed

Chessman enter and without hesitation sit down in

the death chair, watch without expression while his

arms and legs were strapped down. A clutch of

cyanide “ eggs,” poised above a tub of acid beneath

the chair, was released by remote control. As the fumes

rose to shroud the prisoner, his eyes bulged, his head

jerked, he gagged and gasped as he seemed to be

struggling against the straps. In two minutes his

long jaw sagged and his body slumped.

According to medical men, the gaseous cyanide de

rivatives are neurotoxins that attack the nerve centers

and paralyze the cardiac and respiratory functions

at the first deep whiff. The signs of a desperate death

struggle, apparently the symptoms of great suffering,

are again nothing more than unconscious reflexes.

So what is the meaning of all this scientific progress

that we in America have made in the centuries and

centuries since the boiling in oil, the crucifixions and

the hanging of little children? We have perhaps re

duced the coefficient of suffering to within a fraction

of a second of the instantaneous extinction of the

guillotine, which the late Albert Camus described as

“ a crude surgery [without] any edifying character

whatever.” We have reduced our lust for public

blood-letting to boxing (which is becoming more and

14

more bloodless), auto racing and professional football.

We no longer feed our wrongdoers to the crocodiles

or invite VIPs to public hangings, as was the custom

in Arizona, but we still kill our criminals in three

quarters of our American states. We are far ahead

of the rest of the world in the scientific technique of

legal killing, but we are at least a century behind in

the sociological, psychological, economic and humani

tarian approach to the problem of crime and punish

ment.

Why do we still kill our killers'? Do we imagine

that we are doing justice, with no thought of vengeance ?

Do we think we are eradicating crime1? Are we de

luding ourselves that by snuffing out the lives of our

misfits, our nitwits and our psychopathic personalities

(who, our psychiatrists hasten to add, are not con

genital psychopaths), are we creating a better world

for ourselves? Do we really think that punishment

will prevent crime, that killing murderers will prevent

murder ?

Where do we draw the line? I t is certain that we

would consider the Oriental methods of execution cruel.

We would consider other methods that have since been

tried cruel. Does death by a firing squad or gas or

electricity become less cruel because these methods are

used in the name of law and order in the free democ

racy of the United States of America ? The actual

act of execution is not only cruel in and of itself, but

it is more than cruel if we are to contemplate the

days and the nights of a man who is awaiting execu

tion in the name of society by a soverign state. This

usage of cruelty and cold-blooded premeditated murder

is certainly a poor example of the humanity of a

civilized people.

15

Is capital punishment unusual? In the year 1966,

one person was executed by the 37 states still retaining

the death penalty. In the year 1965, with 9,850 homo-

cides committed, there were 7 executions. Year after

year the number of men convicted of homocide and

sentenced to life continues to increase in every state

penitentiary where capital punishment is a part of the

law. The number of persons executed even before

the unofficial moratorium of 1967 has been gradually

decreasing which makes the use of the death penalty

more and more unusual. I t is the person who com

mits the crime in an aroused community who is exe

cuted. I t is the person without proper legal repre

sentation. I t is the person without financial resources.

More and more the world has given recognition to

the sacredness of life. Seventy-three countries have

abolished the death penalty as well as 13 states

of the United States. Yet, in no instance has there

been an eruption of crime. For example, Michigan,

which has not had capital punishment since 1947, over

a period of years has had a lower rate of homocide

than its adjoining states. The same is true with

Maine, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North

Dakota.

Often the death penalty is used as an excuse for

not doing those things that should be done, such as

improving corrections, developing a sounder approach

to rehabilitation, and providing a more modern parole

system. I t seems almost unbelievable that in the year

1971 there should be continued reliance on the destruc

tion of an occasional life with all its self-demeaning

consequences. This is truly an instance where the Su

preme 'Court of the United 'States speaking on behalf

of the Constitution of the United States could restore

justice to all.

16

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the judgments of the Courts

below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

H on. E dmund G. B rown

H on. D avid E . Cargo

H on. E lbert N. Carvel

H on. M ichael Y. D i S alle

H on. P h il ip Id. H ope

H on. T heodore R. M cK eldin

H on. E ndicott P eabody

H on. Grant Sawyer

H on. M ilton J . S happ

By M ichael Y. D i Salle

425 - 13th Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20004

(202)-393-3300

Attorney for Amici Curiae

October, 1971