Gilligan v. Morgan Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gilligan v. Morgan Brief Amicus Curiae, 1972. 494e2c65-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb385450-fb91-469e-90d2-bdc6d0f4ee8d/gilligan-v-morgan-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

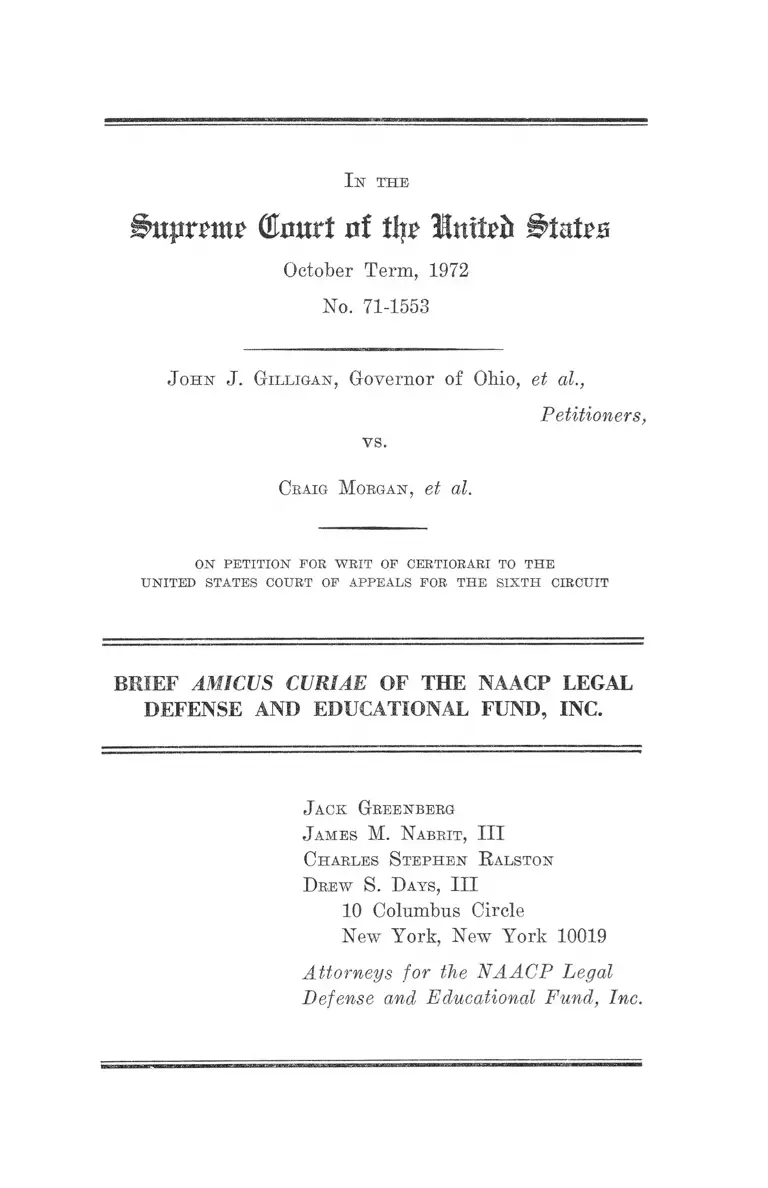

B nprm t (Burnt uf tty Intuit Btattu

October Term, 1972

No. 71-1553

I n the

J o h n J. G illig an , Governor of Ohio, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

Craig M organ, et al.

ON PETITIO N FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E SIX TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

C harles S t e p h e n R alston

D rew S. D ays, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

In the

OInurt nf Stairs

October Term, 1972

No. 71-1553

J ohn J . G illig an , Governor of Ohio, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

Craig M organ, et al.

ON PETITIO N FOB W BIT OP CEBTIOBABI TO TH E

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS FOB TH E SIX TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Interest of Amicus*

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under the laws

of the State of New York to assist Negroes to secure their

constitutional rights through the courts. Its charter de

clares that its purposes include rendering legal aid gratu

itously to Negroes suffering injustice by reason of race

who are unable, on account of poverty, to employ legal

counsel on their own behalf. The charter was approved

* Letters of consent from counsel for the petitioners and respon

dents in this case have been filed with the Clerk of Court.

2

by a New York Court, authorizing the organization to

serve as a legal aid society. The NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), is independent of other

organizations and is supported by contributions from the

public. For many years its attorneys have represented

parties in this Court and the lower courts, and it has

participated as amicus curiae in this Court and other

courts.

LDF has successfully litigated hundreds of suits attack

ing discriminatory and illegal practices of state, county and

municipal authorities affecting the lives and liberties of

blacks and other minorities. Wth few exceptions, LDF

challenges have rested upon the irreconcilability of such

practices—often required by statute—with the spirit and

intent of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

and upon the affirmative remedies afforded by Congress

under the Civil Eights Statutes, specifically, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983.**

Over the years, this Court has often pointed out that

federal court jurisdiction under § 1983 must be given broad

scope to carry out the purposes for which it was enacted.

Here, petitioners seek to curtail drastically the scope of

that important jurisdictional statute. Since the decision of

the Court in this litigation may affect the scope of § 1983,

LDF deems it important to bring to the Court’s attention

some implications of the issues here presented.

** E.g., Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) (voting discrim

ination) ; Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) (restrictive cove

nants) ; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (school

segregation); Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970)

(jury exclusion); and Haines v. Kerner, 405 U.8. 519 (1972)

(prisoners’ rights).

3

Introduction

We respectfully submit that this Court should affirm

the order of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

remanding this issue to the trial court for a hearing on

the merits. There a record can be made which will illumi

nate whether the important jurisdictional statute § 1983

here at issue applies: petitioners may be found—on the

facts—to be without liability, at which point the case most

likely will terminate, eliminating need for decision of the

§ 1983 question. We believe that such a disposition is ap

propriate here in view of the substantial constitutional

question presented by this litigation. The extent to which

federal court consideration and resolution of this question

may conflict with limitations imposed by the “political

question” doctrine or may unduly interfere with certain

basic state responsibilities are not matters which can prop

erly be determined on the bare record before the Court

here.

Argument

At the commencement of this litigation, a federal trial

court was asked to consider and resolve constitutional is

sues arising out of the May, 1970 confrontation between

students and Ohio National Guardsmen at Kent State Uni

versity. The suit had significance not merely because that

incident had attracted national and world-wide attention.

What happened at Kent State was but another in a series

of tragic episodes involving citizens and armed troops.

The suit raised issues equally relevant to these other con

frontations. After the Kent State incident, as well as in

the aftermath of other similar events, investigations iden

tified inadequate training and overreaction on the part of

law enforcement officials in the use of lethal weapons—in

several cases, National Guardsmen—as bearing significant

4

responsibility for the civilian death and injury which re

sulted.1

One of the objectives of these investigations has been to

exhort legislative and executive officials to seek means of

preventing recurrences of such unfortunate incidents. The

trial court’s refusal to address itself to the issues this suit

presented may well have been premised upon the view that

such matters should be dealt with by other branches of

government. But we submit, where the issues are properly

framed, federal courts, too, have authority to adjudicate

litigable matters arising out of these confrontations.

Here the issue is justiciable and within the jurisdiction

of the courts of the United States. For, law enforcement

officials may not inflict summary punishment upon persons

charged with illegal acts. An accused is entitled to be

tried, convicted and sentenced by a lawful tribunal, having

been accorded at each stage all protections encompassed by

“due process”. Screws v. United, States, 325 U.S. 91 (1941).

Excessive force by law enforcement officials under normal

circumstances constitutes “summary punishment” violative

of the Constitution. Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 365 U.S.

365 U.S. 167 (1961). Persons aggrieved by actions of law

enforcement officials may seek injunctive relief against

future infringement. Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939).

If, as the complaint herein alleges, (1) innocent students

were killed or injured by Ohio National Guardsmen, (2)

they were killed as a direct consequence of failure by state

1 President’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders,

Report, pp. 323-326 (Bantam Ed., 1968) (Disturbances in Detroit,

Newark and other cities in 1967) ; President’s Commission on

Campus Unrest, Report, pp. 149-183 (Arno Press Ed., 1970) (Kent

State and Jackson State in 1970); Nelson and Bass, The Orange

burg Massacre (1970), pp. 76-98 (South Carolina State in 1968) ;

and The Washington Post, December 15, 1972, p. 1 (Southern

University, Baton Rouge in 1972).

5

civil and military authorities to train and arm the guards

men properly, and (3) that failure is of a continuing nature

which creates a reasonable likelihood that such conduct will

be repeated in the future, then constitutional violations

have occurred and are occurring which demand federal

court rectification. The fact that the violations occurred

and are likely to occur again under martial law conditions

does not mean that they cease to be acts litig’able in fed

eral court. Martial law cannot suspend constitutional pro

hibitions against the infliction of summary punishment.

See Ex Parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1886).

Where, as here, the complaint raises constitutional

issues not manifestly insubstantial or frivolous, mere

invocation of “political question” or “comity” doctrines

should not close federal court doors to consideration of

the merits of the controversy. They are not talismanic

phrases sufficient to “obscure the need for case-by-case

inquiry” or to preclude the court from, engaging in a

“delicate exercise in constitutional interpretation”, Baker

v. Carr, 369 TT.S. 186, 211 (1962) before declining to act.2

IVe hope that this Court will not cut off resort under

§ 1983 to a federal forum by persons aggrieved by state

action; we believe that this case surely presents no occa

sion to do so. That would thwart the intent of Congress

“to provide at least indirect federal control over the un

constitutional actions of state officials” which state agencies

might not exercise “by reason of prejudice, passion, ne

glect, intolerance or otherwise”. District of Columbia v.

Carter, 41 U.S.L.W. 4127, 4130 (January 9, 1973). Rather,

E.g., in this case, claimed conflict with the federal executive

and legislative branches may turn out not to exist, Regulations

relating to riot control may be adequate, but perhaps were not

followed by the state defendants. Therefore, federal court resolu

tion would not interfere with the powers of coordinate branches

but, instead, vindicate the exercise of such authority.

6

we urge that this Court reaffirm the responsibility of fed

eral trial courts “to give due respect to a suitor’s choice

of a federal forum for the hearing and decision of his

federal constitutional claims.” Zwichler v. Koota, 389' U.S.

241, 248 (1969).3

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Charles S t e p h e n R alston

D rew S. D ays, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the NAAGP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

3 Such a reaffirmation is eminently desirable in view of the recent

decision by the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Krause v.

Rhodes, No. 71-1623 (6th Cir., Nov. 17, 1972) petition for cert,

filed sub nom., Scheur v. Rhodes, 72-914 (41 U.S.L.W. 3377, Janu

ary 9, 1973), for it appears to hold that federal court review of the

Kent State incident by way of traditional § 1983 damage actions is

foreclosed as well. That ruling, when read in conjunction with the

trial court’s decision here, seems to leave truly aggrieved persons

out of court under § 1983 no matter what relief is being sought.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219