United States of America v State of Georgia Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

July 11, 1997

45 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States of America v State of Georgia Brief for Appellant, 1997. 8913117a-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb47a860-54fd-468b-895c-1d409af17187/united-states-of-america-v-state-of-georgia-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

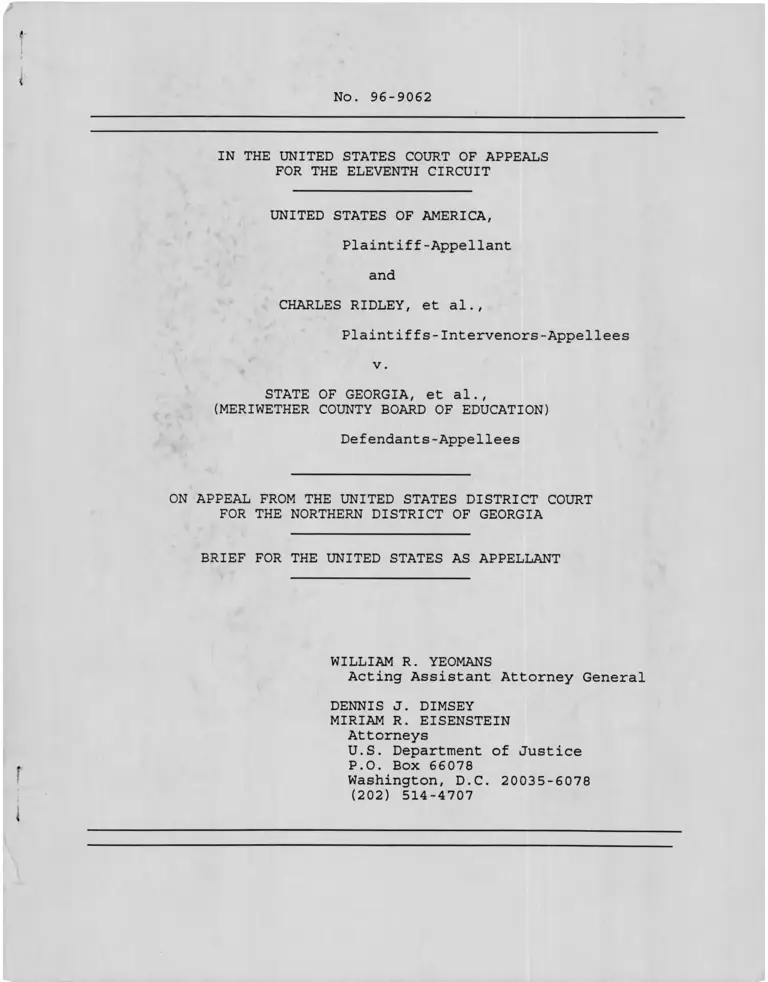

No. 96-9062

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

and

CHARLES RIDLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees

v .

STATE OF GEORGIA, et al.,

(MERIWETHER COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION)

Defendants-Appellees

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS APPELLANT

WILLIAM R. YEOMANS

Acting Assistant Attorney General

DENNIS J. DIMSEY

MIRIAM R. EISENSTEIN

Attorneys

U.S. Department of Justice P.O. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078 (202) 514-4707

United States of America

v. State of Georgia,

No. 96-9062

C-l of 2

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PARTIES AND

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Eleventh Circuit Rule 26.1, appellant, United

States of America, lists the following persons or entities which

may have an interest in the outcome of this case.

Curtis Eugene Anderson

Tommie Lee Bryant

Martha L. Dean

Dennis J. Dimsey

Salliann Dougherty

Lucille M. Durham

Miriam R. Eisenstein

Jeremiah Glassman

Jennye Hardaway

Phillip L. Hartley

Robert Hawk

Richmond Hill

Elaine Jones

MERIWETHER COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FIND, INC.

Dennis D. Parker

United States of America

v. State of Georgia,

No. 96-9062

C-2 of 2

Martha M. Pearson

Brenda Phillips

Charles Ridley

STATE OF GEORGIA

Robert Lee Todd IV

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Joe D. Whitley

William R. Yeomans

THE HONORABLE ROBERT L. VINING, JR., UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

The United States believes that oral argument would be

helpful to the Court in this case.

CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE

This brief is typed in 12 point Courier.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER AND

APPELLATE JURISDICTION .................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE I S S U E ....................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ......................................... 2

A. Course Of Proceedings And Disposition Below ........ 2

B. Facts............................................... 4

1. Historical Background.......................... 4

2. The 1995 P l a n ................................ 12

3. The Objections................................ 16

4. The Response.................................. 19

C. The District Court Decision And Opinion ......... 21

STANDARD OF R E V I E W ........................................ 2 3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.......................................... 24

ARGUMENT:

I. INCORRECT LEGAL PREMISES SHAPED THE DISTRICT

COURT'S DISCRETION TO APPROVE THE FIVE YEAR

P L A N ............................................ 26

A. It Is Legally Incorrect That The Board's

Facilities Plan Is Valid As Long As It Is

Not Motivated By Racially Discriminatory

P u r p o s e .................................... 2 6

- i -

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued): PAGE

B. Nothing In Case Law Makes “Plus-or-

Minus 20 Percentage Points” Into A

Universal Legal Standard .................... 27

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION BY

BASING ITS DECISION ON SOME ERRONEOUS FINDINGS

AND IGNORING RELEVANT FACTS ...................... 33

CONCLUSION................................................ 3 6

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

* Freeman v. Pitts. 503 U.S. 467 (1992)................ passim

* Georgia State Conference of Branches of NAACP v.

Georgia. 775 F.2d 1403 (11th Cir. 1985) .............. 28

Green v. County Sch. Bd.. 391 U.S. 430 (1968) ........ 22, 27

Harris v. Crenshaw Countv Bd. of Educ.. 968 F.2d 1090

(11th Cir. 1992).................................. 23, 26

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver. Colo.. 413 U.S.

189 (1973).......................................... 31-32

Stall v. Board of Pub. Educ. for the City of Savannah

& County of Chatham. 860 F. Supp. 1563

(S.D. Ga. 1994) ................................ 27-28, 29

* S w a n n V. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.. 402 U.S. 1

(1971)........................................ 24, 26, 34

ii

CASES (continued): PAGE

United States v. Georgia. 19 F.3d 1388

(nth cir. 1994)............................. passim

STATUTES:

28 U.S.C. 1292 (a) (1) 2

28 U.S.C. 1345 1

RULES:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a)...................................... 23

MISCELLANEOUS:

United States Department of Commerce, 1990 Census of

Population (1990 CP-2-12) 4

* Authorities chiefly relied upon are marked with asterisks.

- iii -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 96-9062

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

and

CHARLES RIDLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA, et al.,

(MERIWETHER COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION)

Defendants-Appellees

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF SUBJECT MATTER AND APPELLATE JURISDICTION

The district court had continuing jurisdiction of this

school desegregation suit under 28 U.S.C. 1345. On June 28,

1996, the district court granted the Meriwether County School

Board's petition to approve a Five Year Facilities Plan

(RIO-147) ,1/ The United States filed a timely notice of appeal

17 "R" refers to the volumes and numbered documents listed on

the district court's docket. "PI. Exh." refers to the

Plaintiffs' exhibits at trial in 1990. "RS" refers to the

(continued...)

-2-

on August 23, 1996 (Rll-156). This Court has jurisdiction under

28 U.S.C. 1292(a)(1) from the district court's order modifying an

injunction.

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

Whether, based upon errors both of law and of fact, the

district court abused its discretion in approving the defendants'

Five Year Facilities Plan.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Course Of Proceedings And Disposition Below

The United States filed this suit against the State of

Georgia and 81 public school districts, including the Meriwether

County Board of Education, on August 1, 1969 (United States v.

Georgia. 19 F.3d 1388, 1390 (11th Cir. 1994)). On December 17,

1969, the court entered a detailed injunction (see Order of July

23, 1973, at 6).z/ In 1970, certain individuals representing

black school children intervened as plaintiffs in the statewide

case (19 F.3d at 1390). The district court lifted the detained

17 (. . . continued)

supplemental record volumes assigned by the court to the

transcripts of the 1990 nonjury trial.

J The Order of July 23, 1973, no longer in the district court's

office (see 19 F.3d at 1390 n.l), will be filed by agreement of

the parties, together with the exhibits that are apparently

missing from the district court as well, in a motion to

supplement the record after the briefs are filed.

-3-

injunction and entered a permanent injunction by Order of July

23, 1973 (n.2, supra). In 1979, the district court placed the

case on its inactive docket (19 F.3d at 1390) .

In 1986, the Board of Education (Board) adopted a Five Year

Facilities Plan. When the Board voted to drop this plan, in

1988, the Hill Intervenors moved to reopen the case (Rl-1),

alleging noncompliance by the Board with the 1973 injunction.

The United States filed a Motion to Enforce the 1973 Order and

for Supplemental Relief on October 16, 1989 (R5-47). On November

13, 1989, the district court granted a motion by the Ridley

Intervenors that inter alia, directed the State to hold onto

certain funds allocated to the Board for construction (R5-53).

After a bench trial in February, March, and May of 1990, the

district court entered several orders closing one high school

(RS3-521 to 522, ruling from the bench), ordering equalization of

the high school curricula, and halting most interdistrict and

intradistrict transfers of students (19 F.3d at 1391; R7-71).

In November 1992, a new Board voted to pursue the previously

proposed high school consolidation (19 F.3d at 1391). The

district court, upon joint motion of all the parties (R8-98),

ordered the State to release the funds it had been holding in

abeyance since November 1989 to help fund the plan (R8-99,

modifying R5-53). A civic group opposed to the plan tried to

intervene in this suit (R8-100), but the district court denied

intervention (R8-108) and this Court affirmed (19 F.3d 1388).

-4-

The would-be intervenors, meanwhile, acquired a state court

injunction on procedural grounds preventing release of the state

funds and preventing the consolidation plan from being

implemented (19 F.3d at 1392 n.5).

On January 23, 1996, the Board filed a petition for approval

of a new Five Year Facilities Plan that called for two high

schools (R9-130). The United States and the Intervenors objected

to the Plan (RIO-132 and RIO-136) and moved for an evidentiary

hearing (RIO-143 and RIO-144). On June 28, 1996, the district

court entered an order granting the Board's petition and denying

the motions for an evidentiary hearing (RIO-147). On August 22,

1996, the district court filed a memorandum opinion (Rll-155) .

The United States and the Intervenors filed notices of appeal on

August 23 and August 26, 1996, respectively (Rll-156 and Rll-

157) .

B . Ea.c.ts

l. Historical Background

Meriwether County is in southwestern Georgia. As of 1990,

it had a population of 22,411 people, the majority of whom were

white (United States Department of Commerce, 1990 Census of

Population (1990 CP-2-12), Georgia, Section 1, Table 6, at 27).

In 1969, Meriwether County's school population was over

5,000 pupils, about 58% of whom were black (see n.3, infra). A

formerly jure dual system, Meriwether had 11 schools in 1969,

6 of them attended entirely by African American children.

-5-

Schools in the City of Manchester, in the southern portion of the

county, were attended predominantly by white children. The City

of Greenville (in the central part of the county) had two schools

housing grades 1-12. One, called "Greenville Consolidated," had

824 black students; the other, smaller one, was called

"Greenville High School" and was predominantly white.1 11 Figures

furnished to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare for

1970 reflect that desegregation in Greenville was achieved by

having two single-sex schools housing grades 1-12. The single-

1 The following figures are from data furnished to the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare for 1969:

School_________________

Luthersville Elem.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Greenville Consolidated

McCrary Elem.

Woodbury Elem./Sec.

Meriwether Co. Train.

Greenville High

Manchester Elem.

Meriwether Elem.

Warm Springs Elem.

Manchester High

Grades______No. b n o . w

1-8 286 0

1-6 144 0

1-12 824 0

1-8 326 0

1-12 568 0

1-12 672 0

1-12 26 575

1-7 45 619

1-8 22 239

1-8 20 181

8-12 18 476

-6-

sex structure of the Greenville schools was abandoned for the

1971-72 school year. Instead, the schools were paired so that

Greenville Consolidated (now Greenville Elementary) served

children in grades 1-7 and Greenville High School, grades 8-12

(Order of July 23, 1973, at 3).

In 1973, the district court lifted the detailed order and

replaced it with a permanent injunction enjoining the State from

taking any action that would "result in the reestablishment of

the former dual school system" and from providing funds to any

school district found in violation of the injunction (Order of

July 23, 1973, at 5). The court also officially approved the

pairing arrangement of the Greenville schools (id. at 6). Among

other things, the permanent injunction provided that all future

school construction, consolidation, and site selection would be

done in a manner "which will prevent the reoccurrence of the dual

school structure" (î L. at 7). The court also enjoined all the

school districts in the statewide case from granting transfers in

or out of the district that would have the cumulative effect of

reducing desegregation in either the sending or receiving

district (ibiiLJ . In 1979, as indicated at 3, the court

put this case on inactive status.

Meriwether had ten schools in the late 1980s: six element

ary, one middle school, and three high schools (Stipulation

-7-

#1) While the school population was 60% black, the three

Manchester schools were between 64%-67% white. The Greenville

and Woodbury schools, by contrast, were between 72%-88% black

(ibilLJ •

A census taken by the school district in May 1988 showed

that 233 white students had transferred, within the system, to

schools to which they were not assigned, most of them to the

three predominantly white Manchester schools: 85 to Manchester

Elementary School, 61 to Manchester Middle School, and 29 to

Manchester High School (Stipulation #10). These intradistrict

transfers of white children were mainly transfers out of

Greenville and Woodbury schools (PI. Exh. 10). In addition, as

of October 1988, a large number of white children from

predominantly black Talbot County School District were also

attending those three schools: 37 in Manchester Elementary, 45

in Manchester Middle, and 46 in Manchester High School

(Stipulation #3). According to Jerry Hicks, who was chairman of

the School Board from the late 1970s until 1988 (and again since

- The stipulations of the parties were in an unsigned pretrial

order that was never entered on the docket. They were forwarded

to the district court for inclusion in the record by agreement of

the parties, but they were never forwarded to this Court.

Accordingly, they will be filed with a motion to supplement the

record after the briefs are filed.

-8-

1992), the Manchester schools were perceived to be "white"

schools while the Greenville and Woodbury schools were perceived

to be "black" schools (RS4-731 (Hicks); see also RSI-105 to 106

(Stekelenberg, former superintendent of schools) (Manchester High

School perceived as the white school and Greenville High School

as the black school)).

In 1986, the Board adopted a plan to replace the three high

schools with one consolidated school. This proposal set off a

prolonged conflict. None of the existing high schools --

Greenville, Woodbury, or Manchester -- had an adequate plant, but

Woodbury was clearly the worst, followed by Greenville (RS2-246

to 290 (Carroll McGuffey)). There were also serious disparities

among the curricular offerings (PI. Exh. 109 and 111; RS4-770 to

778 (testimony of former Board chairman Hicks)).

The State's Quality Basic Education (QBE) Act determines how

much state assistance a school district can get to build or

renovate facilities. A school district is eligible for the

maximum "incentive" funding if it adopts a K-5, 6-8, and 9-12

grade organization, and has schools that house either the

prescribed minimum number of students or all the students in

those grades (RS3-596 to 597 (Cloer, State Department of

Education)). The minimum school sizes for new construction

funding are 450 for an elementary school, 624 for a middle

school, and 970 for a high school (RS3-589).

-9-

On November 4, 1986, the Board voted 3-2 (over the

opposition of the Manchester and Warm Springs members) to locate

a comprehensive high school at a central site east of Greenville

(RS4-807 to 809 (Hicks)). Opposition to the plan was centered in

the predominantly white southern portion of the county, spear

headed by a group calling itself the Citizens for Community

Schools. Some of the opposition was explicitly racial in

character. See RS4-812 to 815, 819, RS5-837 to 839, 850 to 851

(Hicks); RSI-156, 158 to 159, 161 (Stekelenberg). On April 14,

1987, by a 3-2 vote, the Board approved the plan to build a

comprehensive high school (RS5-841 to 843 (Hicks)). In 1988,

Chairman Jerry Hicks was replaced on the Board (RS4-733 (Hicks)),

and the Board voted in April 1988 to abandon the Five Year Plan

(RS5-851 to 854 (Hicks)). While the Board was considering

alternative plans, the Ridley and Hill Intervenors reactivated

this case (Rl-1) (August 1988).

In July 1989, the Board adopted a resolution calling for a

new, two-high school plan to be financed by a bond issue if it

passed a referendum. The resolution kept the one high school

plan as a default plan in case the referendum failed (RS5-855 to

857 (Hicks); RS10-1742 to 1743 (Forehand); Pi. Exh. 107). At

this point, the United States and the Intervenors filed their

motions to enforce the 1973 desegregation order (R3-42 and R5-

47) .

-10-

The United States focused upon the transfers of students,

intradistrict and interdistrict, arguing that they contributed to

the perception that the Manchester schools are "white" schools

and the Greenville schools are "black" schools. In addition, the

United States argued that retention of Greenville High School and

Manchester High School -- even if Woodbury were closed -- would

undo whatever progress had been made in dismantling the dual

system. The United States asked the court to order equalization

of opportunity at the high school level by any means that would

work, did not enhance segregation, and did not place an

inordinate burden on black children. See R5-47.

In November 1989, upon motion of the United States and the

Ridley Intervenors, the district court ordered the State to hold

onto the entitlement money that had been set aside for Meriwether

County pending the outcome of the renewed litigation (R5-53).

The bond issue referendum was defeated on October 3, 1989.

Although the original resolution contemplated going back to the

consolidated high school plan if the referendum failed, the Board

then rescinded that resolution (RS5-857 to 859 (Hicks)). That

left the entire matter in limbo while the parties went to trial

on the motions by the United States and the Intervenors.

In 1990, after a bench trial, the district court entered

several orders, but did not require the district to build a

consolidated high school. The court ordered the Board to close

Woodbury High School, to send the students in grades 9-12 to

-11-

Manchester High, and to distribute the eighth grade students

between Greenville High School and Manchester High School. Among

other things, the court enjoined all future transfers. Children

who lived in the Talbot County part of the City of Manchester,

however, were allowed indefinitely to transfer to schools in the

Meriwether County part of the City of Manchester (R7-71 and R7-

78). Finally, the court directed the Board to "offer the same

courses above the core curriculum at both Manchester High School

and Greenville High School" and to bring the faculties of all the

schools into line with the district-wide ratio (R7-71; see also

19 F.3d at 1391).

In 1992-1993, as indicated supra at 3, the Board went

through another round of approving and then abandoning a plan to

consolidate high schools. Shortly after a new Board was elected

in November 1992, it voted to pursue the consolidation plan. The

Board, State, and plaintiffs jointly moved the court to direct

the State to release the funds it had been holding so that

construction could begin. This time, members of the Citizens for

Community Schools of Meriwether County moved to intervene to

prevent the money from being distributed for this purpose. They

claimed that the Board had bowed to pressure from the United

States and no longer represented their interests. The district

court disagreed, and denied the intervention. Meanwhile, how

ever, the same group went to state court and got an injunction

against release of the money on the ground that the Board had not

-12-

followed proper procedures (19 F.3d at 1391-1392 & n.5). This

Court affirmed the district court's denial of the intervention on

May 4, 1994 (19 F.3d at 1389). In September 1995, the district

court authorized the State to reallocate the capital funds it had

been holding for Meriwether County (R8-124).

2. The 1995 Plan

On November 8, 1994, the Board put the question of a

consolidated high school to a referendum, and the voters rejected

the proposal (R9-130-2 (Affidavit of Superintendent Hawk)). Con

sequently, on November 15, 1994, the Board passed the first of a

series of resolutions leading to the current Petition to Approve

a Five Year Facilities Plan based, among other things, on the

assumption that the county would continue to have two high

schools (R9-130, Exh. 2; RIO-135, Exh. 15). The State Board

approved a proposed two high school facilities plan on November

9, 1995 (R9-130-5 (Hawk Affidavit)). On January 23, 1996, the

Board filed its petition to the court for approval of a new Five

Year Facilities Plan (R9-130).

At this point, there were slightly over 4,000 students in

the system (R9-190, Exh. 4), and blacks accounted for about 65%

of the students. The racial proportions in the schools for the

1995-96 school year were as follows (RIO-135-21 (Report of United

States' Expert William M. Gordon)):^

L/ A slightly different set of figures are presented in the Brief

(continued...)

-13-

School Grades *B %W Total

Luthersville Elem. Pre-K-7 57%B 43%W 547

McCrary Elem. Pre-K-7 90%B 10%W 211

Greenville Elem. Pre-K-7 84%B 16%W 552

Woodbury Elem. Pre-K-5 79%B 21%W 248

Greenville High 8-12 80%B 20%W 672

Warm Springs Elem. Pre-K-5 46%B 54%W 311

Manchester Elem. Pre-K-5 50%B 5 0%W 546

Manchester Middle 6-8 58%B 42%W 448

Manchester High 9-12 53%B 47%W 649

Under the Board's proposed plan, which would have two distinct

phases, the six elementary schools would all eventually be

replaced by three new ones: North, Central, and South. Each of

these would serve grades Pre-K to 5. North Meriwether Elementary

would combine the populations of Luthersville and McCrary,^ and

would feed into a "new" North Middle School (using old Greenville

High School) that would serve grades 6-8, and then into a newly

built North Meriwether High School (grades 9-12) that would

- (...continued)

supporting the Petition at 6, 12 & n.7. That brief is not

separately entered on the docket but was attached to the

Petition.

£/ Under the original resolution, the North Elementary School

would have combined the Pre-K to 5 populations of Greenvil1e and

Luthersville (R9-130, Exh.2; RIO-135, Exh. 15).

-14-

replace the existing Greenville High School. The Board would

refurbish the old Greenville High School to make it into a middle

school. These changes, and the building of a new South Element

ary (combining the populations of Manchester and Warm Springs)

would complete Phase I of the plan. State "entitlement" funds

amounting to $6.6 million would cover a portion of the elementary

school construction; all the rest of the funds for Phase I would

have to be raised through a planned $13 million bond issue and

through local taxes (R9-130-4 to 5; Brief in Support at 10-11).

The proposed Phase II of the plan would involve construction

of Central Meriwether Elementary (to serve the populations of

Greenville and Woodbury) and renovations of Manchester Middle,

Manchester High, and old Greenville High. See Brief in Support

of Petition at 7-12. Each of the new schools would use the

attendance zones and feeder patterns of the schools they replaced

(id. at 7-8).2/ The Board anticipated that a bond referendum

(which it hoped to call for September 1996) would pass because it

believed that there was considerable support for Phase I of the

-x Since there will be only two middle schools and two high

schools, the "central" elementary group would divide those

previously assigned to Greenville elementary going north and

those assigned to Woodbury going south. Indeed, those assigned

to Woodbury elementary have been going south for middle school

and high school since the 1990 order to close Woodbury High.

-15-

plan (id. at 11) .fi/

No funding arrangements were proposed for the second phase

of the plan. No exact sites were selected for any of the new

schools^7 though, the Board claimed, the locations of the schools

would not require significantly longer trips for anyone.

However, even without having selected the exact sites, the Board

anticipated that seventh and eighth graders newly assigned to

North Meriwether Middle School, and all the children who now

attend McCrary Elementary School, would have at least slightly

longer rides than before (Brief in Support at 13-14).

The Board anticipated that the racial proportions in the new

schools would be as follows (Brief in Support at 9): * 11

School Grades No. (%)B NO.(%)W Other Total

North Elem. Pre-K-5 385(62%) 227 (37%) 9 (2%) 621

North Middle 6-8 321(74%) 112(26%) l 434

North High 9-12 471(80%) 118 (20%) — 589

Middle Elem. Pre-K-5 574(83%) 116 (17%) 2 692

South Elem. Pre-K-5 429 (49%) 437 (50%) 5 871

South Middle 6-8 261(56%) 205 (44%) — 466

South High 9-12 335 (50%) 331 (50%) 2 668

y The United States is informed that the referendum in fact

passed.

11 Tentative alternative sites had been explored. See, e .o ..

R10-135-2, 5.

-16-

Defending the plan, the Board argued that the populations of

the new schools would deviate from the district-wide ratio of

about 64%B-36%W by no more than twenty percentage points, no

school would be majority white (Brief in Support at 12-13), and

the staff of every school would be 62% white (based on the 1995-

96 figures) (id. at 14-15). According to the Board, there would

be no reduction in staff as a result of the consolidation of

schools (id. at 15).

3. The Objections

The United States objected to the plan (RIO-137), basing the

objections on a report filed by the United States' expert William

M. Gordon (RIO-135).lfi/ First, the United States took the

position, based on 4̂ of the 1973 Order, that the Meriwether

School Board still had an obligation (when building or moving

schools) to further desegregation (R10-137-3 to 4). The United

States also observed that financing for the plan was (at the

time) speculative as to Phase I and nonexistent as to Phase II

(R10-137-5 to 7). In addition, the United States registered the

following objections:

a. The proposed grouping of schools into north, central,

and southern schools (and feeder patterns) locks in a system of

Because the United States is not raising here every issue it

raised below, this recital of objections and the responses to

them cover only those points pursued on appeal.

-17-

student assignment that reinforces racial identifiability by-

maintaining the traditional north-south division while altern

ative plans could alleviate the identification of schools as

"white" and "black" (R10-137-8 to 12). The United States' expert

Dr. Gordon did not take issue with the consolidation of

Luthersville and McCrary. He recommended, however, that if

historically black Greenville Elementary School were consolidated

with Warm Springs (rather than with 79% black Woodbury), the

resulting combined school would be about 68% black and the oldest

school in the system, Warm Springs, could still be scheduled for

replacement as part of Phase I. This approach would address both

problems -- racial identifiability and the poor condition of both

of the existing schools. Similarly, Dr. Gordon recommended that

Manchester Elementary be consolidated with Woodbury Elementary,

with the resulting consolidated elementary school being 58%

black. Instead, the Board proposed a pattern of consolidations

that would make two new schools (Middle Elementary and South

Elementary) 83% black and 51% white (RIO-137-11 to 15 and RIO-135

- Option 1). In addition, the United States suggested (as

recommended by Dr. Gordon) that the boundaries for the middle

schools be modified so that both middle schools would be about

equal in size and racial composition (RIO-137-16 to 17).

b. The Board planned Middle Meriwether Elementary School,

to replace Woodbury and Greenville Elementary Schools, for the

second phase. There is not even a hypothetical funding plan for

-18-

Phase II. Both Greenville and Woodbury are former jure

segregated schools. Of all the facilities, historically black

Greenville Elementary is either the second or third school most

in need of repair or replacement (R10-135-4, 6, 8) (Luthersville

clearly most in need; Greenville and Warm Springs are next). The

United States noted that, instead of making historically black

Greenville a high priority, the district has designated histori

cally white Manchester and Warm Springs Elementary schools to be

replaced during Phase I of the plan (RIO-137-11 to 12).

c. The United States also argued that the plan for the high

schools violates the 1990 court order to equalize Greenville and

Manchester High Schools. Greenville High School, though it was

not a jure black school, is perceived as "black" if for no

other reason than that location, history, and a record of

unlawful white transfers caused Manchester High to be perceived

as the white school. Greenville High School has had fewer

advanced courses than Manchester High School (RIO-135-38 and Att.

27 & 28; RIO-138 (Deposition of Georgia Drake) at 26-28). Yet

nothing in the Board's plan will correct that situation. The new

North Meriwether High School, scheduled to replace Greenville

High, will still be undersized by state standards, and will still

be likely to have offerings inferior to those at Manchester

(South Meriwether) High n/ (RIO-138 (Deposition of W. Jerry

n/ Although the chart proffered by the Board in its brief

(continued...)

-19-

Rochelle) at 34, 73; RIO-135-37 to 38). It will not have the

trade clusters, auditorium, or stadium, now found at existing

Manchester High School (RIO-135-37 and Attachments 19, 31, 16 &

23). The population, moreover, will be at least 80% black the

day it opens (RIO-137-17 to 18). Consequently, the United

States' expert suggested some alternatives that would mitigate

the disparities between the "white" and "black" high schools such

as building a northern school containing grades 6-12, or

renovating the existing Greenville High School into a 6-12

facility (R10-135-0ptions 3 & 4), or simply redrawing the middle

and high school attendance zones (RIO-137-17 to 18; R10-135-

Option 2; RIO-135-58). ̂

4. The Response

The Meriwether Board of Education responded (RIO-140),

claiming that the the United States' expert did not consider

whether his proposed alternatives would have any support in the

li/ (. . . continued)

anticipated a North High School enrollment of over 500 for 1996-

1997 (Brief at 9), the anticipated enrollment for 1999-2000 was

465, and the construction plan was based on that figure (R10-135-

13 & Exh. 19).

w Dr. Gordon suggested that a northern 6-12 school could have a

combined population of over 1,000 and a high school population of

well over 500, thus enabling the district to become eligible for

some state "QBE" funds (R10-135-Option 2 & Table 9).

-20-

Meriwether County community (R10-140-2, 5), and whether the

funding for these options could be raised in referendum (R10-140-

3). Raising the millage would not be a popular move, and local

voter approval would be necessary to increase local sales taxes

(RIO-140-6). In addition, because the Warm Springs Elementary

School is the oldest school in the county, the Board argued, the

southern part of the county probably would not support any plan

that did not make its replacement a top priority (R10-140-5) .

The Board also took issue with the contention that Greenville and

Woodbury Elementary Schools were significantly more in need of

replacement than Warm Springs and Manchester Elementary (whose

replacement would be built first) (R10-140-16 to 20).

Second, the Board argued that, under what it construed to be

the relevant legal definitions, no school would be racially

identifiable (R10-140-6 to 9). The Board questioned whether it

had any desegregation obligation beyond bringing each school

within the 20 percentage points of the system-wide racial ratio

(id. at 8-10) . According to the Board, moreover, it is

irrelevant how the schools were perceived in 1990 before Woodbury

High School was closed and its students distributed to the other

high schools (R10-140-7 n.8).

Third, the Board took issue with some of Dr. Gordon's

factual assertions regarding the alleged inequalities between the

existing Greenville High and Manchester High, and alleged pro

jected inequalities in the plans for North and South High Schools

-21-

with respect to plant and course offerings (R10-140-9 to 21).

The Board noted that neither high school would have the State's

recommended baseline population of 900-1000 (as opposed to the

minimum population for receiving state aid), and therefore the

plaintiffs' objections with respect to size could only mean that

they were holding out for a single comprehensive high school

(R10-140-12 to 13). The Board noted that Manchester High School

does not have a gymnasium of its own,11'' and one is planned for

North High School (though neither an auditorium nor a stadium is

planned for North High School) (id. at 14). In addition, the

Board noted that some of the courses that Dr. Gordon said were

not offered at Greenville High School in fact had been offered,

though not at the levels originally planned (R10-140-14 to 15 &

n.23). Moreover, the electronic interactive television system

planned for the new high school would, the Board argued, make

classes given at one school available to the other (id. at 16) .

C. The District Court Decision And Opinion

On June 28, 1996, the district court entered an order

approving the Board's petition, and denied the requests by the

United States and the Intervenors for a hearing (R10-147). On

n/ But see PI. Exh. 121 at 101-111 (McGuffey's Report).

Manchester High School has had the use of the nearby and

excellent gymnasium at the Callaway Center.

-22-

August 22, 1996, the court entered its findings and conclusions

in support of that decision (Rll-155).

The district court began with the assumption that, without

evidence of discriminatory intent, there could be no legitimate

objection to the plan. The plaintiffs, however, had "presented

no evidence to show that racial motives played any part in the

school board's decision making process" (Rll-155-4) (emphasis in

original). Thus, as far as the court was concerned, there was no

legal basis to prefer the plaintiffs' alternative recommendations

over the school board's proposal (ibid.).

Second, the court noted that the United States and the

Intervenors had failed to give adequate weight to the fact that

it is very difficult to get a bond referendum passed in Meri

wether County, and that the school board's recommendation is

grounded on political necessities (Rll-155-5 to 6). According to

the district court, a board is obliged only to adopt a plan that

will succeed politically. In support of this proposition, the

court cited v. County School Board. 391 U.S. 430, 439

(1968) ("The burden on the school board today is to come forward

with a plan that promises realistically to work....") (Rll-155-

6) .

Third, the district court took the position that, at least

from the point of view of pupil attendance, none of the schools

would be "racially identifiable" under the proposed plan (Rll-

155-7). The court reserved judgment, however, stating that, if

-23-

the new schools in fact turn out to be racially identifiable

(however defined), the court can take action to remedy it later

(ibid.). Similarly, the district court was prepared to take a

"wait and see" posture with respect to faculty assignments and

transportation (iiL_ at 8-9) — except that the court was sure

that if any greater burden is ultimately placed on black students

than on white students, it will have been because of demographic

patterns (id. at 9).

Finally, the district court did not credit the testimony of

Dr. Gordon that the Greenville High School had course offerings

inferior to those at Manchester High, and therefore had never

been equalized as required by the 1990 order (Rll-155-7 to 8).

Without making specific subordinate findings, the court accepted

the Board's explanation that some of the plaintiffs' numbers were

"simply incorrect" (id. at 8).

Finding no reason to disapprove of the plan, the district

court therefore approved it.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

Approval or disapproval of a proposed facilities plan is

reviewed for abuse of discretion. Harris v. Crenshaw Gonnty Bd,

of Educ.. 968 F.2d 1090, 1098 (11th Cir. 1992). To the extent

that the court's discretion was shaped by an error of law,

however, it is reviewable novo. To the extent that it is

based upon factual findings, the findings are reviewed for clear

error under Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. P.

-24-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court based its consideration of the Board's

petition on the incorrect legal premise that a facilities plan is

acceptable as long as it is not discriminatorily motivated.

School districts that have not achieved unitary status have an

on-going duty. They must ensure that construction and

replacement of facilities furthers desegregation rather than

freezing the status quo or reestablishing racially identifiable

schools. Freeman v. Pitts. 503 U.S. 467, 485 (1992); Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.. 402 U.S. 1, 21 (1971). The

district court further erred, as a matter of law, by declaring

that the schools in Meriwether County would not be racially

identifiable under the new plan. The ratio of black to white

students at each school would be within 20 percentage points of

the system-wide ratio, but there is no absolute rule that this

ratio qualifies the school district as having unitary status for

purposes of school attendance. The Middle Elementary School

would unnecessarily combine two former iifi. jure black schools,

Woodbury and Greenville, into an 83% black school. The South

Elementary and High Schools would still be disproportionately

white, and continue to function as a haven for white students

from Talbot County. Greenville High School would still be at

least 80% black, reinforcing its image as the "black high

school." None of these problems, moreover, is an inevitable

result of demographic patterns. There are viable alternatives

-25-

that would be more desegregative. The Board has made a conscious

decision to freeze the north-south division of the county. The

district court has permitted the Board to avoid its continuing

duty.

In addition, the district court ignored salient facts in

summarily granting the Board's petition. The court ignored the

history of school transfers that had reinforced the racial makeup

and images of certain schools as "black" or "white" schools. The

court paid no attention to the fact that the Board has chosen to

give first priority to replacing the elementary school that

houses the largest proportion of white students in this majority-

black school system. The court also summarily dismissed the

contention that Greenville High School has been maintained as

both black and inferior. Thus, the district court failed to

appreciate the degree to which the Board has not yet dismantled

its dual system. The court did this, moreover, without holding

the hearing requested by the United States and the Intervenors.

Accordingly, the district court abused its discretion in granting

the petition.

-26-

ARGUMENT

I

INCORRECT LEGAL PREMISES SHAPED THE DISTRICT

COURT'S DISCRETION TO APPROVE THE FIVE YEAR PLAN

A. It Is Legally Incorrect That The Board's Facilities

Plan Is Valid As Long As It Is Not Motivated By

Racially Discriminatory Purpose____________________

"The duty and responsibility of a school district once seg

regated by law is to take all steps necessary to eliminate the

vestiges of the unconstitutional de jure system." Freeman v.

Pitts. 503 U.S. 467, 485 (1992). Local authorities and the

district courts must "see to it that future school construction

and abandonment are not used and do not serve to perpetuate or

re-establish the dual system." v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ.. 402 U.S. 1, 21 (1971) (emphasis added). See also

Order of July 23, 1973, in this case. The board's "duty to

desegregate is violated if [it] fails to consider or include the

objective of desegregation in decisions regarding abandonment

[and construction] of school facilities." Harris v. Crenshaw

County Bd. of Educ.. 968 F.2d 1090, 1095 (11th Cir. 1992). It is

an abuse of discretion, therefore, for the district court to

approve a plan that is inconsistent with the Board's continuing

duty, and it is not relevant that the Board may have had no

affirmative intent to discriminate when it promulgated the plan.

-27-

The district court's reliance on Green v. County School

Board. 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968), as a basis for approving the

plan, is misplaced. It is true that Green calls for plans that

"work." A desegregation plan that "works," however, is one that

desegregates. Nothing in Green holds that it is the court's role

to accommodate the local white citizens' determination to have

their schools replaced ahead of any other schools. "[A] school

board that is properly subject to continuing court supervision

may be required to relinquish its political autonomy to the

extent that its decisions are shown to adversely impact the

objective of alleviating the unconstitutional conditions that

justified the court's initial intervention." United States v.

Georgia (Meriwether County). 19 F.3d 1388, 1392 (11th Cir. 1994).

B. Nothing In Case Law Makes "Plus-or-Minus 20

Percentage Points" Jinto A Universal Legal Standard

Without asking to be declared partially unitary, the Board

has taken the position that the Five Year Facilities Plan will,

in effect, create a school district that is unitary with respect

to pupil attendance. The district court apparently concurred in

the defendants' theory that the facilities plan cannot be faulted

as long as the result will be schools whose populations meet the

benchmark of plus-or-minus twenty percentage points from the

systemwide ratios of 65%B-35%W. This figure has appeared as an

analytic tool in Pitts. 503 U.S. at 476, and in Stell v. Board of

Pub. Educ. for the City of Savannah & County of Chatham. 860

-28-

F. Supp. 1563 (S.D. Ga. 1994). It does not follow, however, that

this formula in the abstract represents the limits of a school

district's obligation in every instance.

A formerly jure segregated school district is required to

achieve the maximum practical desegregation. Pitts. 503 U.S. at

480. The Board incorrectly assumed, however, that there is some

absolute cut-off or legal benchmark after which it is no longer

under any obligation to take the more desegregative alternatives

-- even though they exist and are practicable. The Board based

that assumption, in part, on an assertion in Georgia State

Conference of Branches of NAACP v. Georgia. 775 F.2d 1403, 1413

(llth Cir. 1985), taken out of context, that a school district

need not take the most desegregative alternative in every

instance.

In Georgia Branches, the court of appeals held that school

districts were not absolutely barred from using ability groupings

even though heterogeneous groupings would have been more desegre

gative. In context, the court was holding only that some

practices could be justified educationally even though they might

not be the most (intra-school) desegregative alternative.

Georgia Branches does not suggest that a school board can,

generally and without either a practical problem or an

educational justification, decide that it is free to take a less

desegregative alternative.

-29-

A school district is not free of its obligation to desegre

gate, when further desegregation is practicable, merely because

it has reached a numerical benchmark used in a case involving

some other school district. Pitts and Stell concern the huge

urban school districts of DeKalb and Chatham Counties, Georgia.

DeKalb County had some 74 elementary schools by the time Pitts

was decided, dozens of them in large areas populated overwhelm

ingly by African Americans. A twenty percentage point benchmark

for "racial identifiability" makes some sense in that context.

It has no universal legal significance, however.

What the courts made clear, in both Pitts and Stell. is that

"unitariness" in school attendance patterns has less to do with

the numbers than with the reasons for them. A school district is

obliged to strive to reach that point at which school attendance

patterns, even if racially identifiable, are "attributable nei

ther to the prior de jure system nor to a later violation by the

school district but rather to independent demographic forces."

Pitts. 503 U.S. at 493.̂ Meriwether County has not reached

^ In Pitts. the system was found to have achieved "unitary-

status " with respect to pupil attendance patterns even though a

large number of the schools did not meet the criterion of having

a student body balanced within 20 percentage points of the

district-wide racial proportion.

-30-

that point now, nor will it be closer to that point if the pro

posed plan is put into effect.

Meriwether County has only 4,000 students and nine schools.

At this time, six of those schools have populations that are 15

percentage points or more away from the district-wide norm:

McCrary Elementary, Greenville Elementary, Woodbury Elementary,

Greenville High, Warm Springs Elementary, and Manchester

Elementary. The Five Year Plan (if it ever is completely funded)

will result in a system having only seven schools, and two of

those schools will be just as racially identifiable as ever:

North Meriwether High (80%B), and Central Meriwether Elementary

(83%B). A third school, South Meriwether Elementary (49%B),

while technically desegregated, would still be very dispropor

tionately white. These patterns, moreover, will not have

occurred by chance or by virtue of demographic change alone.

School boards can contribute to racial segregation either by

directly causing the racial imbalance or by doing things that

contribute to demographic change that segregates people by race.

Pitts. 503 U.S. at 507-508 (opinion of Souter, J.); id. at 510-

513 (opinion of Blackmun, J.). The Meriwether Board has done,

and continues to do, both of these things.

First, it cannot be ignored that the Meriwether schools were

jure segregated, and that the Greenville and Woodbury Element

ary Schools are vestiges of that system. The fact that sie. jure

segregation officially ended a long time ago is irrelevant.

-31-

These schools are as identifiable as black schools as they were

thirty years ago; to this extent, the Board has not yet dis

established the original dual system.

Second, the Board has contributed to the racial identi-

fiability of Greenville High School. Racial identifiability in a

system that has both black and white students is a matter of

contrasts: a school can be perceived to be the "black school" if

there are only two schools serving these grades and, over a long

period of time, the Board has permitted one of them to serve as a

haven for white students. Throughout the 1980s, whites were

allowed to flee from the Greenville High School and Woodbury High

School attendances zones and attend Manchester High School.

Whites were and still are permitted to flee Talbot County

majority-black schools to attend Manchester schools. When the

district court closed Woodbury High School, it did distribute

some black students to Manchester High -- but it also distributed

black students to the already majority-black Greenville High. To

this day, Manchester High School is disproportionately white. If

allowed to proceed as planned, the Board will entrench the

attendance patterns that identify the South High School as the

white school and the North High School as the black school.

"[T]he practice of building a school * * * to a certain size and

in a certain location, with conscious knowledge that it would be

a segregated school * * * has a substantial reciprocal effect on

the racial composition of other nearby schools." Keyes v. School

-32-

Dist. No. 1. Denver. Colo.. 413 U.S. 189, 201-202 (1973)

(internal quotation marks omitted).

While it may be true that the present population of the high

schools as well as that of the elementary schools reflects

residential patterns in the county, it is not written in stone

that this relatively small county must be divided on a north-

south axis for school attendance purposes. Traveling from north

to south and vice versa to attend school is not impossible. In

fact, the record reflects that people did so for years to avoid

going to "black" schools. In the process of approving the Five

Year Plan, the district court has approved the Board's choice of

schools to combine when the system goes from six to three

elementary schools. Though no sites have been selected yet, the

sites would be selected based on the Board's assumptions about

which schools' populations are to feed into them. The Board,

therefore, will actively contribute to fixing attendance patterns

that are unnecessarily racially identifiable for generations to

come .ii/

^ The district court took at face value the Board's assurances

that black children would not be disproportionately burdened

before sites had been selected.

-33-

II

THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED ITS DISCRETION BY BASING

ITS DECISION ON SOME ERRONEOUS FINDINGS AND IGNORING

RELEVANT FACTS

The district court did not address the issue of the Board's

priorities reflected in the plan. Although deploring the sad

condition of the Meriwether schools, the district court paid no

attention to the plaintiffs' contention that leaving the new

Middle Elementary School for the unfunded second phase of the

plan burdens black children disproportionately and without any

justification except, perhaps, that a plan putting white children

first is easier to sell to the citizenry that must vote for the

bond issue.

The Middle Meriwether Elementary School anticipated by the

Board for Phase II would combine Greenville and Woodbury Element

ary Schools -- two historically black schools that had also been

affected by illegal transfers out of white students. Postponing

the building of the substitute school to Phase II means that the

predominantly black student body in the dilapidated Greenville

school will again be handicapped --by having to stay in a

substandard school longer than will other students in the system.

"Independent of student assignment, where it is possible to

identify a 'white school' or a 'Negro school' simply by reference

to * * * the quality of school buildings or equipment, * * * a

prima facie case of violation of substantive constitutional

-34-

rights under the Equal Protective Clause is shown." Swann. 402

U.S. at 18. In this case, in addition, when the substitute

school is finally built (if it is built), it will open as a

school disproportionately attended by African American children.

South Meriwether Elementary will be the successor to a pair

of historically white elementary schools,- the district court has

expressly allowed continued interdistrict transfers into one of

them (Manchester Elementary). By contrast to the Middle

Elementary School, this school will be built early in the

schedule. Thus, the school will be identifiably "white" both

because of its disproportionately white population and because it

will be brand new, while the predominantly black Greenville and

Woodbury Schools await the unspecified funding of Phase II.

The district court also made factual errors and abused its

discretion in its treatment of the high school question (Rll-155-

7 to 8). The proposed North Meriwether High would be, literally,

the successor to Greenville High. Contrary to the court's find

ing, Greenville High School has offered fewer advanced courses

than the other high school. See PI. Exh. 109 & 111. In fact,

Secondary Curriculum and Vocational Education Director Georgia

Drake indicated that she does not recall advanced placement

courses being given at Greenville at any time since 1988 (RIO-138

(Drake Deposition) at 26-27). Nor, contrary to the court's

finding, has Greenville High offered every course requested by

-35-

ten or more students.1̂ Greenville High also has acquired the

reputation of being a black school partly because, in the past,

the Board permitted white pupils to transfer into increasingly

white Manchester High School. Thus, Greenville has in fact been

perpetuated as both the black school and the inferior school.

The district has not equalized the education at the two high

schools as required by the district court's 1990 order. Nor has

the district fulfilled its ongoing duty to see to it that there

are not black or white schools that can be identified as such.

The new North Meriwether High School, successor to Green

ville High School, will be built with fewer typical high school

features (like an auditorium and a ballfield with grandstands)

than the old school it will replace (which will be used as a

middle school). There is no excuse for opening a new high school

with these shortcomings -- and with a population at least 80%

black. The United States' expert suggested that, instead of

building a new high school, the district could build a new 6-12

school. Alternatively, it could repair and improve the old plant

of Greenville High School and turn it into a facility housing

Dr. William M. Gordon's Report On Two High School Local

Facilities Plan (R10-135-40), shows that there were a number of

subjects offered at Manchester High -- sometimes when fewer than

ten students requested the course -- and not given at Greenville

High even though 20-27 students requested that it be offered.

-36-

grades 6-12. This would make the facility eligible for some

state money and would enable the school to make optimum use of

its combined middle school/high school faculty. Indeed, if the

county has abandoned the idea of having a single comprehensive

high school, it could have two schools serving grades 6-12 and

have attendance zones on some basis other than a north-south

division. In short, there are a number of ways in which the

county could use the building of new facilities as a way to

dismantle what is left of the dual system. Instead, it has

chosen the path of least resistance, and the district court has

let it do so. In addition, the court has denied the plaintiffs a

hearing in which more options could have been offered and spelled

out.

The judgment of the district court should be vacated and the

cause remanded for a hearing and decision consistent with the

correct facts and legal principles.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM R. YEOMANS

Acting Assistant Attorney General

DENNIS J. DIMSEY

MIRIAM R. EISENSTEIN

Attorneys

Department of Justice

P.0. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on July 11, 1997, I served all parties

to this case with two copies of the attached Brief for the United

States as Appellant and one copy of the Record Excerpts, at the

following addresses:

Philip L. Hartley, Esq.

Martha M Pearson, Esq.

P.0. Box 2975

Gainesville, GA 30503

Robert Lee Todd IV, Esq.

Todd and Todd

P.0. Box 663

Greenville, GA 30222-0663

Kathryn L. Allen, Esq.

Senior Assistant Attorney General

Suite 229, State Judicial Building

40 Capital Square, S.W.

Atlanta, GA 30334-1300

Dennis D. Parker, Esq.

Elaine R. Jones, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

MIRIAM R. EISENSTEIN

Attorney

4