Carmical v. Craven Reply Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carmical v. Craven Reply Brief for Appellant, 1970. 34e527ca-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb4fda59-5178-44ff-9ca1-02e5c5c7b289/carmical-v-craven-reply-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

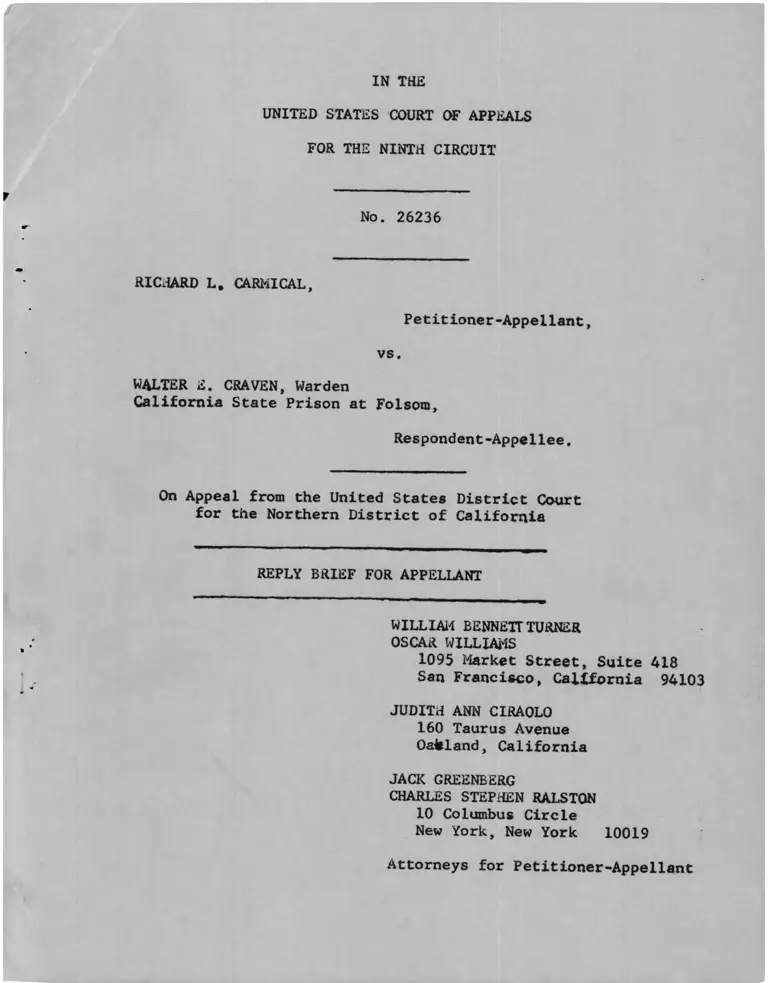

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 26236

RICHARD L. CARMICAL,

Petitioner-Appellant,

vs.

WALTER E. CRAVEN, Warden

California State Prison at Folsom,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

OSCAR WILLIAMS

1095 Market Street, Suite 418

San Francisco, California 94103

JUDITH ANN CIRAOLO

160 Taurus Avenue

Oakland, California

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

I. Petitioner Cannot Be Held To Have

Deliberately By-Passed State Procedure

With Respect To The Issue Of Racial

Discrimination In The Composition Of

The Jury Panel.

II. Petitioner Established A Prima Facie

Case Of Unconstitutional Jury

Discrimination Which Has Not Been

Rebutted By The State.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Clark v. American Marine Corp.,

304 F.Supp. 603 (E.D. La. 1969) 9

Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95

(5th Cir. 1964) 4, 5

Curry v. Wilson, 405 F.2d 110

(9th Cir. 1968) 4

Fay v. Noia,•372 U.S. 391 (1963) 2, 3, 4

Fernandez v. Meier, 408 F.2d 974

(9th Cir. 1969) 2, 3

Gaston County v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969) 9

Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc.,

316 F.Supp. 401 (C.D. Cal. 1970) 9

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443 (1965) 5

Henry v. Williams, 299 F.Supp. 36

(N.D. Miss. 1969) 5

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) 9

Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

397 U.S. 919 (1970) 9

McNeil v. State of North Carolina,

368 F.2d 313 (4th Cir. 1968) 3, 4, 5

Nelson v. California, 346 F.2d 73

(9th Cir. 1965) 5

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc.,

279 F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968) 9

Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking

Organization v. Union City,

424 F .2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970) 9

iii

Page

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) 6, 8

United States v. Logue, 344 F.2d 290

(5th Cir. 1965) 9

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers,

Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) 9

United States ex rel Seals v. Wirnan,

304 F .2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962) 9

Whippier v. Balkcom, 342 F.2d 388

(5th Cir. 1965) 4

4

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

California Code of Civil Procedure,

Section 198(2) 6

iv

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

NO. 26236

RICHARD L. CARMICAL,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v s .

WALTER E. CRAVEN, Warden,

California State Prison at Folsom,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

I. Petitioner Cannot Be Held To Have Deliberately

By-Passed State Procedure With Respect To The

Issue Of Racial Discrimination In The Composition

Of The Jury Panel.

The Attorney General argues that since petitioner did

not challenge the composition of the jury panel before or at

his trial, he is precluded from raising the issue on federal

habeas corpus because he has deliberately by-passed state

procedure. This contention is wholly without merit.

-1-

The Attorney General made the same contention in

the District Court. The District Court, however, proceeded

directly to the merits of the case, thereby necessarily

rejecting the "by-pass" contention. In other words, the

court below sub silentio found that petitioner had not

waived his important constitutional right to a jury selected

without racial discrimination.

The Supreme Court has laid down the test for a

deliberate by-pass or waiver as follows:

"If a habeas applicant, after consultation

with competent counsel or otherwise,

understandingly and knowingly forewent the

privilege of seeking to vindicate his federal

claims in the state courts, whether for

strategic, tactical, or any other reasons

that can fairly be described as the deliberate

by-passing of state procedures, then it is

open to the federal court on habeas to deny

him all relief. . .though of course only

after the federal court has satisfied itself,

by holding a hearing or by some other means,

of the facts bearing upon the applicant's

default." Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 439

(1963).

In the instant case, the court below obviously "satisfied

itself" that no waiver could be found on this record. The

District Court's conclusion was compelled by controlling

precedent and was plainly correct.

In Fernandez v. Meier, 408 F.2d 974 (9th Cir. 1969),

this Court dealt with a collateral attack on jury composition

by a federal prisoner. No objection had been raised at trial.

-2-

The Court held that the issue could be raised on collateral

attack unless it was waived in accordance with the test of

Fay v. Noia. Referring to the question of whether the issue

was waivable by counsel, as opposed to a personal waiver by

the petitioner, this Court relied (408 F.2d at 977, n. 5)

on McNeil v. State of North Carolina, 368 F.2d 313 (4th Cir.

1968). The McNeil case is directly in point. There, a state

prisoner, on federal habeas corpus, attacked racial

discrimination in the composition of the jury. The issue

had not been raised by him before or at trial. The Court

said that there is every reasonable presumption against

waiver of this issue. 368 F.2d at 315. Waiver may not be

presumed from a silent record. Id. No waiver may be found

in the absence of "affirmative conduct on the part of a

defendant evidencing a deliberate and conscious rejection

of a constitutional guarantee." Id. The Court gave special

emphasis to the Supreme Court's language in Fay v. Noia, that

a decision to forego this constitutional claim must be "the

considered choice of the petitioner." I_d. (Emphasis by the

Court). Waiver of this issue by counsel does not bar relief

on habeas corpus. Id.; Cf. Fay v Noia, 372 U.S. at 439.

The Court in McNeil found that there was "no evidence"

that the defendant, after intelligent conversation with his

attorney, had understandingly and knowingly waived the right

to challenge the composition of the jury. The Court therefore

-3-

held as a matter of law that there had been no waiver and

directed the District Court to grant the writ of habeas

corpus. 368 F .2d at 317.

Also squarely in point is the Fifth Circuit's

decision in Cobb v. Balkcom, 339 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1964).

Again, a state prisoner on federal habeas challenged racial

discrimination in the composition of the jury. The issue

had not been.raised at trial. The Court of Appeals, in a

careful and thorough opinion, noted the trial attorney's

affidavit that he was well aware of the issue but did not

raise it because he was satisfied that a fair and impartial

jury could be obtained and that it was in the best interest

of the defendant not to raise the issue. The Court

nevertheless stated that waiver of this issue must be made

by the defendant personally and not by counsel. 339 F .2d

at 102; accord, Whippier v. Balkcom, 342 F.2d 388, 392

(5th Cir. 1965). The Court held that the defendant had not

waived or by-passed this important constitutional protection.

In short, in the instant case, as a matter of law,

there could be no waiver or deliberate by-pass. It is true

that some federal rights may be waived by counsel for a

defendant if this is done as a matter of trial strategy or

tactics. See Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. at 439; Curry v. Wilson,

405 F.2d 110 (9th Cir. 1968)(objection to admission in

-4-

evidence of recordings, where counsel entered express

stipulation); Nelson v. California, 346 F.2d 73 (9th Cir.

1965)(objection to admission of illegally seized evidence).

But objection to composition of the jury panel is not one

of the issues waivable by counsel without the express

personal concurrence of the defendant. See McNeil v. State

of North Carolina, supra; Cobb v. Balkcom, supra.

Challenging racial discrimination in the composition

of the jury panel is not a matter of trial tactics. Rather,

jury discrimination involves a systemic defect in the

administration of justice. In the instant case, there is

nothing to show that petitioner ever agreed to forego the

constitutional right to challenge the system of jury selection

in Alameda County, or that he even knew of either the method

of selecting prospective jurors or his right to question it.

Petitioner's important federal right to a fairly selected

jury has not, on this record, been deliberately by-passed

or waived. The Court should, as did the District Court,

proceed directly to the merits.

V

1/ Cf. Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443, 450-451 (1965).

On remand, the District Court in Henry found that the

State had failed to meet the heavy burden--a "high

quality of proof, with every reasonable presumption

indulged against waiver"--of showing that the right was

explained to the defendant and that he participated in

the decision not to assert it. Henry v. Williams,

299 F.Supp. 36 (N.D. Miss. 1969).

-5-

II. Petitioner Established A Prima Facie Case

Of Unconstitutional Jury Discrimination

Which Has Not Been Rebutted By The State.

It is undisputed that the "clear thinking" test used

in the selection of petitioner's jury panel excluded 81.5%

of eligible black or poor jurors, while excluding only 29%

of eligible white middle class jurors. The Attorney General,

in attempting to distinguish Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

(1970), urges that this racial and economic exclusion was

not "intentional" or "purposeful" because it was accomplished

by an "objective" standard, that of "ordinary intelligence."

The Attorney General therefore concludes that such exclusion

was not unconstitutional.

There are two critical defects in the Attorney

General's argument: (1) the "clear thinking" test, although

purporting to objectively measure ordinary intelligence, did

not in fact reliably do so; and (2) the only requirement of

"intent" or "purpose" is that the practice having discriminatory

effect be engaged in deliberately, as distinguished from an

accidental act.

1. The "Objective" Standard of Intelligence. The

"clear thinking" test was apparently Alameda County's response

to California Code of Civil Procedure, Section 198(2), which

specifies that for a person to be "competent" to serve as a

juror, he need be "in possession of his natural faculties

-6-

The test,and of ordinary intelligence and not decrepit."

however, determined that more than 80% of the registered

voters of the Oakland ghetto did not possess "ordinary

intelligence." Even if this inherently incredible result

does not conclusively show the unfairness and unreliability

of the test, there is the affidavit of Dr. Jay Rusmore, an

expert in psychological testing of this kind, which

establishes (without contradiction by the State) that the

"clear thinking" test did not reliably measure a prospective

juror's intelligence (R.70-73). Dr. Rusmore noted several

fundamental defects in the test and its administration:

(1) it contained too few questions to produce reliable

results; (2) it was improperly administered in that persons

tested were not advised that they would be stopped after

ten minutes; (3) it was never "validated" to determine

whether it in fact measured "ordinary intelligence;" (4) the

cut-off score for passing was too high; (5) the failure rate

of all persons and especially for ghetto persons was too high

to indicate that the test actually measured intelligence; and

(6) certain questions were culturally biased against poor or

minority persons (R.70-73). His conclusion was that "it can

in no way be said that the test provided an accurate or

adequate measure of the intelligence of prospective jurors. . .

(R.72-73). This evidence stands unchallenged in the record.

Indeed, the Attorney General apparently concedes the fact

-7-

that the test does not reliably measure what it is supposed

to measure; the brief for appellee acknowledges that the test

"may measure something higher or somewhat different from

'average intelligence'" (p. 11), that it may exhibit some

"cultural bias" (Id) and that it was a "poorly drawn test

which was eliminating too many people of ordinary intelligence

2/

both black and white" (p. 18). The court below also noted

that the test "may have been imperfect" (R.88).

On this record, then, it cannot be maintained that

the mechanism for excluding black and poor persons from the

jury was the "objective" factor of "ordinary intelligence."

As we stated in our main brief (pp. 16,20), we do not contend

that the State may not require that jurors be intelligent.

We contend simply that since the "clear thinking" test

excluded a disproportionate number of minority persons, the

burden was on the State to show that it in fact adequately

and accurately measured the intelligence of prospective

jurors. See Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346, 358 (1970).

This, the State has not done. Indeed, petitioner has

affirmatively demonstrated that the test did not reliably

measure intelligence. Therefore, the test's exclusion of

black and poor jurors was unconstitutional.

2/ As stated in the brief for appellee (pp. 7-8) , the State

accepted as true the facts set forth in the petition, the

opinion in People v. Craig and petitioner's supplemental

memorandum (including the affidavit of Dr. Rusmore).

-8

2. The Requirement of "Intentional" or "Purposeful"

Discrimination. The Attorney General argues that the

discrimination was not "intentional" or "purposeful" because

it results from the "objective" factor of intelligence. We

have shown above that the State has not carried its burden of

showing that the discrimination in fact results from

objectively measuring intelligence. It remains only to note

that petitioner is not required to show actual racial

motivation, ill will, evil intent or lack of good faith on

the part of the jury commissioner; the only requirement is

that the practice having discriminatory effect be engaged in

deliberately, as distinguished from an accidental act. Cf.

United States ex rel Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53, 65 (5th Cir

1962); Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 995-997

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970); United

States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th

Cir. 1969); Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc., 316 F.Supp. 401,

403 (C.D. Cal. 1970); Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279

F.Supp. 505, 517-518 (E.D. Va. 1968); Clark v. American

Marine Corp., 304 F.Supp. 603 (E.D. La. 1969); Gaston County

v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969); Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385 (1969); United States v. Logue, 344 F.2d 290

(5th Cir. 1965); Southern Alameda Spanish Speaking

Organization v. Union City, 424 F.2d 291, 295 (9th Cir. 1970)

Here, of course, administration of the exclusionary "clear

thinking" test was an established official practice, not an

accident.

9-

Respectfully submitted,

UJa JU -. 7? jZULww-

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

OSCAR WILLIAMS

1095 Market Street, Suite 418

San Francisco, California 94103

JUDITH ANN CIRAOLO

160 Taurus Avenue

Oakland, California

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner-Appellant

-10-