Commonwealth v. Edelin Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Commonwealth v. Edelin Brief Amicus Curiae, 1975. f55d7f1d-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb576ef0-b53d-468e-b89f-ef52f7adf3b4/commonwealth-v-edelin-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

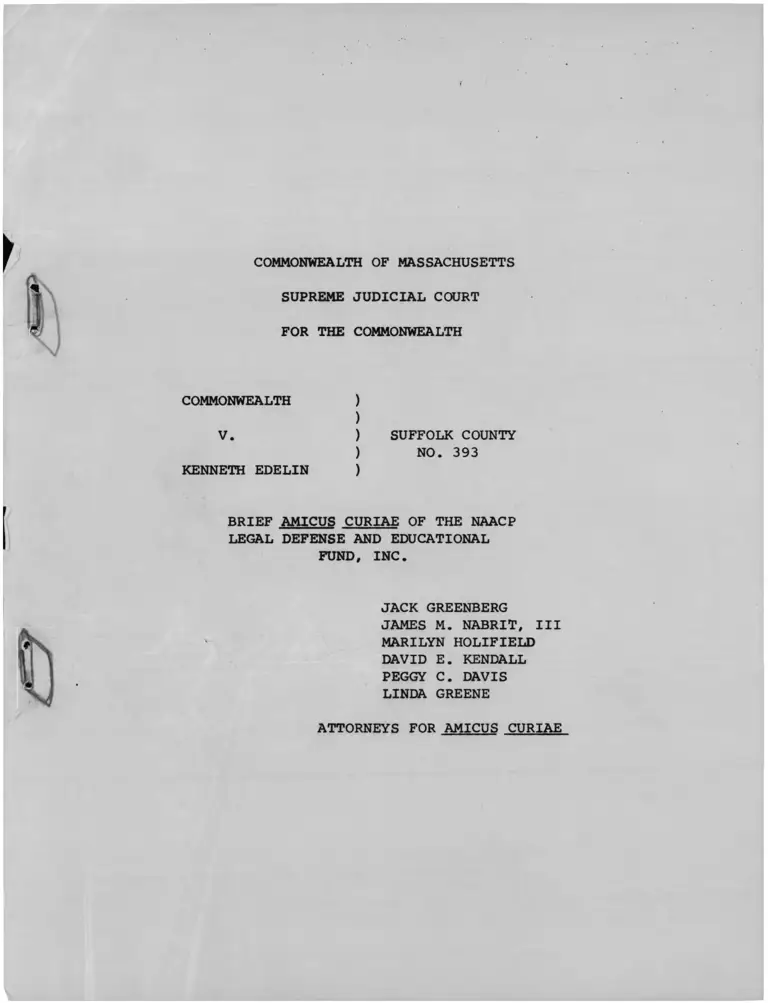

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT

FOR THE COMMONWEALTH

COMMONWEALTH

V.

KENNETH EDELIN

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC.

SUFFOLK COUNTY

NO. 393

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MARILYN HOLIFIELD

DAVID E. KENDALL

PEGGY C. DAVIS

LINDA GREENE

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

\

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest of the Amicus

Curiae .......... 1

Argument 6

1

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249

(1953)......................... 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U.S. 483 (1954).............. 2

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134

(1972) ........................ 9

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S.

471 (1970)..................... 9

Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 6,7,11,14,

(1973) .......................25,37,39

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S.

353 (1963)................... 9

Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S.

438 (1972)................... 7»1°

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972) ...................... 2

Goosby v. Osser, 409 U.S. 512

(1973) .................... •* 9

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S.

12 (1956).................... 9,38

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971).............. 2

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381

U.S. 479 (1965).............. 7,10

Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519

(1972)....................... 2

Harper v. Virginia Bd. of

Elections, 383 U.S. 663(1966). 9

Lindsey v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56

(1972)....................... 9

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1

(1967)....................... 10

TABLE OF CASES

Page

ii

Page

McDonald v. Bd., of Election

Commrs., 394 U.S. 802

(1969)....................... 9

Patton v. Mississippi, 332

U.S. 463 (1947).............. 2

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268

U.S. 510 (1925).............. 10

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S.

158 (1944)................... 10

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).. 6,7,10,11,14,25,37,38,39

San Antonio Independent School

District v. Rodriquez, 411

U.S. 1 (1973)............. 8,9

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial

Hospital, 323 F.2d 959 (CA4

1963), cert, denied, 376 U.S.

938 (1964)................... 2

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618

(1969)....................... 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1

(1948)....................... 2

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535

(1942)....................... 1°

Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645

(1972)....................... 10

Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395 (1971) 9

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S.

745 (1966)................... 9

Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S.

235 (1970)................... 9

iii

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Page

Berger, Tietze, Pakter & Katz,

Maternal Mortality Associated

with Legal Abortions in New

York State, July 1, 1970-

June 30, 1972, 43 OBSTET. &

GYN. 315 (1974)................

Bracken & Swigar, Factors Associated

with Delay in Seeking Induced

Abortions, 113 AM.J.OBSTET. &

GYN. 301 (1972)................18-

PHEW Report; Fewer Out-of-State

Abortions in 1972, 3 FAMILY

PLANNING DIGEST 12 (No. 5,1974).

Dryfoos, A Formula for the 1970's:

Estimating Need for Subsidized

Family Planning Services in the

United States, 5 FAMILY PLANNING

PERSPECTIVES 145 (No.2,1973)---

Gibbs, Martin & Gutierrez, Patterns

of Reproductive Health Care

Among the Poor of San Antonio,

Texas, 64 AM.J.PUB.HEALTH 37

(1974).........................

Glass, Effects of Legalized Abortion

on Neonatal Mortality and Obstet

rical Morbidity at Harlem Hospital

Center, 64 AM.J .PUB.HEALTH 717

(1974).........................

36

20,36

32

13

30

17,35

iv

Page

Kerenyi, Mid-trimester Abortion

in OSOFSKY,H. & OSOFSKY,J.

(ed.), THE ABORTION EXPER

IENCE 383 (1973)............... 17

Kerenyi, Glascock & Horowitz,

Reasons for Delayed Abortions:

Results of 400 Interviews,

117 AM.J.OBSTET. & GYN. 229

(1973)......................... 17,20,25

Mallory, Rubenstein, Drosness,

Kleiner & Sidel, Factors

Responsible for Delay in

Obtaining Interruption of

Pregnancy, 40 OBSTET. & GYN.

556 (1972)..................... 23,31,35

Muller, Health Insurance for

Abortion Costs; A Survey,

2 FAMILY PLANNING PERSPECTIVES

12 (No. 4,1970)................ 23

Muller & Jaffe, Financing Fertility-

Related Health Services in the

United States, 1972-1978: A Pre

liminary Projection, 4 FAMILY

PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 6 (No.l,

1972).......................... 21

NEWSWEEK, Mar. 3, 1975, at 24 ..... 11

Osofsky, Poverty, Pregnancy Outcome

and Child Development, 10 BIRTH

DEFECTS 37 (No. 2, 1974)....... 26

v

Page

Pakter, Impact of the Liberalized

Abortion Law in New Ynrk City

on Deaths Associated with

Pregnancy; A Two Year Experience,

49 BULL. N.Y. ACAD. MEDICINE 804

(1973) ......................... 34,35

Pakter, New York's Liberalized

Abortion Law; An 18-Month

Summary for New York City,

28 NEW YORK MEDICINE 326

(1972).........................17,18,35

Pakter & Nelson, Abortion in New

York City; The First Nine Months

3 FAMILY PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 5

(No. 3,1971)................... 22,35

SARVIS, R., THE ABORTION CONTROVERSY

(1974) ........................ 23

Sklar & Berkov, Teenage Family Forma

tion in Postwar America, 6 FAMILY

PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 80 (No. 2,

1974)............................ 33

Smith & Kalozony, Inequality in Health

Care Programs; A Note on Some

Structural Factors Affecting

Health Care Behavior, 12 MEDICAL

CARE 860 (1974).................. 27

Sparer & Okada, Welfare and Medicaid

Coverage of the Poor and Near

Poor in Low Income Areas, 86

HSMHA [Health Services and Mental

Health Administration] HEALTH

REPORTS 1099 (1971).............. 22

vi

Page

Tietze, Two Years Experience with

a Liberal Abortion Law; Its

impact on Fertility Trends in

New York City, 5 FAMILY PLANNING

PERSPECTIVES 36 (No.2, 1973)--- 17,18

TIETZE, C., JAFFE, F., WEINSTOCK, E.,

& DRYFOOS, J., PROVISIONAL

ESTIMATES OF ABORTION NEED &

SERVICES IN THE YEAR FOLLOWING

THE 1973 SUPREME COURT DECISIONS

— UNITED STATES, EACH STATE &

METROPOLITAN AREA (1975, Alan

Guttmacher Institute of the

Planned Parenthood Federation

of America).................... 12,13,15,

16,17,20

U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty in the

United States 1959-1968, CURRENT

POPULATION REPORTS, Series P-60,

No. 68 (Dec. 31, 1969).........

Weinstock, Tietze, Jaffee & Dryfoos,

Legal Abortions in the United

States Since the 1973 Supreme

Court Decisions, 7 FAMILY

PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 23(No.l,

1975)..........................

Walton, Epstein, Gallay & Nelson,

Development of an Abortion

Service in a Large Municipal

Hospital,64 AM.J.PUB.HEALTH

77 (1974)......................

Wolfe, Primary Health Care for the

Poor in the United States and

Canada, 2 INT. J. HEALTH SERVICES

217 (1974)......................

V l l

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT

FOR THE COMMONWEALTH

COMMONWEALTH )

)

V. ) Suffolk County No. 393

)

KENNETH EDELIN )

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC.

Interest of the Amicus Curiae

Amicus curiae NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., is a non-profit

corporation, incorporated under the laws of

the State of New York in 1939. It was formed

to assist blacks to secure their constitutional

rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its

charter declares that its purposes include

rendering legal aid gratuitously to Negroes

suffering injustice by reason of race who are

unable, on account of poverty, to employ legal

counsel on their own behalf. The charter was

approved by a New York court, authorizing the

organization to serve as a legal aid society.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is independent of other organizations

and is supported by contributions from the

public. For many years its attorneys have

represented parties in the Supreme Court of

the United States, state supreme courts, and

lower courts and have also appeared as amicus

curiae in many cases.

A central purpose of the Fund is the

legal eradication of practices in our society

that bear with discriminatory harshness upon

blacks and upon the economically and culturally

deprived, who too often are blacks. The Fund

has represented clients in cases such as

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

2

(1954); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971); Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1

(1948); Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972)

Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519 (1972); Patton

v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947), which

have had a profoundly reformative effect

on the laws and social practices of this

country.

As part of the Legal Defense Fund's

litigation program to secure racial equality,

many suits involving provision of fair and

adequate health facilities and services have

been filed. The Fund won a landmark decision

in s-imkins v, Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital,

323 F.2d 959 (CA4 1963), cert, denied, 376

U.S. 938 (1964), outlawing segregation in

health care, and it has won a number of

other cases involving discriminatory treat

ment of black physicians or of black patients

/

Lawsuits also established the rights of black

physicians and dentists to membership in state

and local medical and dental societies which

performed services for state governments. The

Fund has also filed a number of complaints

with the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act in an attempt to insure non-discriminatory

federally funded health care services.

Because of its lengthy involvement in

civil rights issues relating to health care,

the Legal Defense Fund is almost uniquely

capable of illuminating for the Court an

important issue which may not be addressed

in detail by either party in this case: the

effect of an affirmance of appellant's crim

inal conviction upon the ability of indigent

black women to secure abortion services. While

amicus curiae does not advocate the general

4

use of abortion as a family planning or popu

lation control device, it believes that abor

tions by safe medically-approved methods should

be available to women who desire to terminate

unwanted pregnancies in situations where contra

ceptives have failed or had not been available,

where the parents' income has suddenly been

reduced or where other circumstances make pro

vision of a decent home environment for a

child impossible, where the pregnancy was due

to rape, or where the fetus may be born de

formed as a result of the mother's exposure

to rubella or drugs. Amicus curiae believes

that it is important that low-income women not

be discriminated against because of their pov

erty when they decide to seek abortions in these

situations and has filed this brief because

5

this case presents important questions of

law and policy affecting directly the rights

of the poor to equal protection of the laws

and to the full enjoyment of the personal

privacy rights guaranteed under Roe v. Wade,

410 U.S. 113 (1973), and Doe v. Bolton, 410

U.S. 179 (1973).

ARGUMENT

Appellant, a black senior resident ob

stetrician and gynecologist at Boston City

Hospital, a public facility which provided

medical care to a great many low-income inner-

city residents, was convicted of manslaughter

as a result of a hysterotomy abortion he per

formed on an unmarried black patient. T. 6—

77, 6— 88, 7— 70, 8— 6, 18-116-117. Amicus

curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., will address in this brief the

single question of the impact of this prosecu

tion and conviction on the Ninth and Fourteenth

6

Amendment rights (as recognized in Roe V.

Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) and Doe v. Bolton,

410 U.S. 179 (1973)) of low-income women to

1/terminate unwanted pregnancies. The patient

for whom appellant performed the abortion

which formed the basis for this manslaughter

prosecution was an "18-year old black female."

T. 8— 6. During the trial, appellant offered

to demonstrate that "the general run of

[appellant's] patients were not of the best

in health" and that most of the persons who

1/ Appellant clearly has standing to assert

and vindicate the constitutional rights of

his patients. Griswold v. Connecticut, 381

U. S. 479, 481 (1965); Eisenstadt v. Baird,

405 U.S. 438, 443-446 (1972). Cf. Barrows

V. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953).

7

sought abortions from him "were poor people

who suffered the regular afflications [sic] of

poor people." T. 18— 116. The trial court

suggested, however, that to admit such evi

dence would be to consider "an awful lot of

collateral issues." T. 18— 117. Amicus curiae

respectfully submits, however, that the in

hibiting effect of this criminal prosecution

on the ability of appellant's low-income

patients to secure adequate and safe abortion

services is an extremely important issue in

this case and constitutes a significant

reason appellant's conviction should be

reversed.

While the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the federal

Constitution does not require the elimination

of all state-imposed discriminations based

upon wealth, San Antonio Independent School

8

Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973); Lindsey

v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56 (1972); Dandridge v.

Williams. 397 U.S. 471 (1970), it does require

that restrictions upon "fundamental rights" be

extraordinarily justified by some compelling

state interest,. San Antonio Independent School

Dist. v. Rodriquez, supra, 411 U.S. at 18. In

addition to the "fundamental" right to fair

treatment in the criminal process, see Griffin

v. Illinois. 351 U.S. 12 (1956); Douglas v.

California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963); Tate v. Short,

401 U.S. 395 (1971); Williams v. Illinois,

399 U.S. 235 (1970), to vote, Harper v. Virginia

Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966); McDonald

v. Bd. of Election Commrs., 394 U.S. 802 (1969);

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972); Goosby

v. Osser. 409 U.S. 512 (1973), and to travel,

Shapiro v. Thompson. 394 U.S. 618 (1969);

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966),

9

the Supreme Court of the United States has

recognized the guarantee under the Ninth

and Fourteenth Amendments of a constitutional

right of personal privacy extending "to

activities relating to marriage, . . . pro

creation, . . . contraception, ... . family

relationships, and child rearing and education,

Roe v. Wade, supra, 410 U.S. at 152-153. See

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967); Skinner

v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942); Eisenstadt

v . Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972); Griswold jy.

Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965); Stanley

Illinois, 405 U.S. 645 (1972); Princely.

Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944); Pierce,y^

gon-i^ty of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925). "This

right of privacy . . .is broad enough to en

compass a woman's decision whether or not to

terminate her pregnancy." Roe v. Wade, supraf.

410 U.S. at 153.

10

Unless appellant's conviction is reversed,

/the constitutional right recognized in Roe v.

Wade and Doe v. Bolton will be severely and

unjustifiably restricted. Indeed, the convic

tion of appellant has already inhibited the

willingness of certain public hospitals to

perform second trimester abortions:

"[I]n Los Angeles, the Planned

Parenthood Office reported a

10 percent increase in the number

of women coming in because doctors

or hospitals to which they first

turned had refused to abort them

in the seventeenth or eighteenth

week. Meanwhile Hutzel Hospital

in Detroit announced it would no

longer do abortions after sixteen

weeks, and a twelve-week limit was

set at West Penn Hospital in

Pittsburgh."

NEWSWEEK, Mar. 3, 1975, at 24. This limita

tion on the availability of abortions comes at

a time when the need for such medical services

already far surpasses the present capacity of

the public health care delivery system of

11

this country. An extensive report by the

Planned Parenthood Federation of America,

released on October 6, 1975, revealed that

between two-fifths and three-fifths of United

States women needing abortions (approximately

one-half to one million women) in 1973 were

yunable to obtain them. This report estimated

that approximately half of these women who/

were unable to obtain abortions had incomes

classified by the federal government as "low"

or "marginal": "One-third of these women —

2/ TIETZE, C., JAFFE, F., WEINSTOCK, E., &

DRYFOOS, J., PROVISIONAL ESTIMATES OF ABORTION

NEED & SERVICES IN TOE YEAR FOLLOWING THE 1973

SUPREME COURT DECISIONS— UNITED STATES, EACH

STATE & METROPOLITAN AREA (1975, Alan Guttmacher

Institute of the Planned Parenthood Federation

of America) at 9 [hereinafter cited as 1975

PPFA Study].

12

413,000-580,000— had low incomes (below 125%

of the federal poverty index)[and] one-fifth

had marginal incomes (between 125 and 200

3/

percent of the index.)"

3/ 1975 PPFA Study at 7. The federal poverty

index is a schedule of gross income and family

size thresholds which is adjusted each year

acco rding to changes in the Consumer Price

Index. See U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty in the

United States 1959-1968. CURRENT POPULATION

REPORTS, Series P-60, No. 68 (Dec. 31, 1969).

While this index "is not an ideal measure of

socioeconomic status, it is superior to income

alone because it approximates per capita in

come and provides a uniform measure applicable

to all sections of the nation." 1975 PPFA Study

at 70. See generally Dryfoos, A Formula for

the 1970's: Estimating Need for Subsidized

Family Planning Services in the United States,

5 FAMILY PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 145 (No.2,1973).

13

The inhibiting effect on the willingness

of public hospitals to provide abortions

caused by a fear of criminal manslaughter

prosecutions will disproportionately affect

those people in low income brackets who al-

i/ready have a difficult time getting abortions.

4/ A study of abortions performed since Roe

v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton found:

"the failure of publicly financed

hospitals to . . . [provide abor

tions] . ... particularly limits

the availability of abortion to

low-income residents who depend

on such hospitals for much of

their medical care, . . . Only 17

percent of public hospitals were

providing abortions during 1973 and

the first quarter of 1974, compared

to 28 percent of non-public non

catholic hospitals. Indeed, in 11

states not a single public hospital

reported performance of a single

abortion for any purpose whatso

ever in all of 1973; and in five

other states fewer than 5 percent

of all hospital abortions were per

formed in public facilities. W ithin

14

and who tend to seek later abortions than more

affluent women. The 1975 report of the Planned

Parenthood Federation of America concluded:

"all available evidence indicates

that low-income women continue to

face great difficulties in obtain

ing safe, legal abortions. In 37

states, the number of abortions

reported by public hospitals con

stituted less than 15 percent of

the estimated number needed by

low-income women." 5/

4/ cont'd.

the overall reluctant response of

U.S. hospitals to the Supreme Court

decisions, therefore, public insti

tutions have been slowest to respond.

Whatever the reason for this differ

ential response, its effect is to

make the constitutional right to

choose abortion considerably less

available to low-income women."

Weinstock, Tietze, Jaffee, & Dryfoos, Legal

Abortions in the United States Since the 1973

Supreme Court Decisions, 7 FAMILY PLANNING

PERSPECTIVES 23, 31 (No. 1, 1975).

5/ 1975 PPFA Study at 9.

15

This study estimated that in Massachusetts in

1974, there was a need for abortion services

in from 35,500 to 49,520 cases, and that low

and marginal income women comprised 41% of

6/

this population. From the first quarter of

1973 to the first quarter of 1974, only 12,370

abortions were provided in Massachusetts, and

1/

public hospitals accounted for only 780.

The fact that low income women seek later

abortions than more affluent women is well

documented. Although about three-quarters of

6/ 1975 PPFA Study at 48. It was estimated

that from 14,440 to 20,380 low and marginal

income women needed abortion services in 1974.

Ibid.

7/ 1975 PPFA Study at 62. The remainder were

performed in clinics (5880), private hospitals

(5280), and physicians' offices (430). Ibid.

16

/

all abortions actually performed are done in

8/

the first trimester, the overwhelming majority

of the remaining women who secure later abor

tions are poor. Low-income residents depend

9/

largely on public hospitals for their abortions,

8/ Tietze, Two Years Experience with a Lib

eral Abortion Law: Its Impact on Fertility

Trends in New York City, 5 FAMILY PLANNING

PERSPECTIVES 36 (No.2,1973); Pakter, New York's

Liberalized Abortion Law: An 18-Month Summary

for New York City, 28 NEW YORK MEDICINE 326

(1972); Glass, Effects of Legalized Abortion

on Neonatal Mortality and Obstetrical Morbid

ity at Harlem Hospital Center, 64 AM. J. PUB.

HEALTH 717 (1974)? Kerenyi, Mid-trimester

Abortion in QSOFSKY, H. & OSOFSKY, J. (ed.),

THE ABORTION EXPERIENCE 383 (1973).

9/ The 1975 Report of the Planned Parenthood

Federation of America found that the response

of public hospitals to Roe v. Wade and Doe

v. Bolton had been extremely sluggish. The

Federation warned that:

"The default of hospitals and other

existing health agencies, if it

continues, will perpetuate sharp in

equities in the availability and

accessibility of legal abortion to

women in different communities and

sections of the nation. The default

of public hospitals, if it continues,

will perpetuate inequities based on

socioeconomic status."

17

and a study of abortions in New York City

found that municipal hospitals serving low

income patients had the greatest proportion

Wof patients seeking late abortion. Two

other studies found that non-private patients

have relatively more abortions in the second

trimester: "women referred from private phys

icians apply for abortions at an earlier stage

of pregnancy. Applicants referred through the

clinic and university services presented

11/[themselves] later." Race is also a distin

guishing feature of the group of women who

10/ Pakter, New York's Liberalized Abortion

Law: An 18-Month Summary for New York City,

28 N.Y. MEDICINE 326 (1972).

11/ Bracken & Swiqar,Factors Associated with

Delay in Seeking Induced Abortions,113 AM.J.

0BSTET.& GYN.301, 305 (1972). The percentages

were quite striking — 25% of the private

patients applied for abortiorP after the tenth

week, whereas 45% of the non-private applied

after the tenth week. Ibid. See Tietze, Two

Years Experience with a Liberal Abortion Law:

Its Impact on Fertility Trends in New York

City, 5 FAMILY PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 36

(No. 2, 1973).

18

must seek abortions in the second trimester.

12/

12/ Indeed, there is some evidence that non

whites in the United States seek abortions

proportionately more frequently than whites.

The 1975 Planned Parenthood Federation study

noted that:

"New York City, Maryland and

California . . . report that the

incidence of abortion among non

whites, a disproportionate number

of whom have low incomes, is two

to three times greater than among

whites.

Further support for a higher rate

of abortion utilization among low-

income women comes from abortion

service statistics for residents of

New York City. While Medicaid has

changed many of the traditional

patterns of health service utiliza

tion, it still remains true that a

greater proportion of low-income

women obtain obstetrical care from

non-private services, while a great

er proportion of higher income women

obtain care from private services.

The differential incidence of abortion

in these two types of services, there

fore, can be used to indicate the

differential incidence of abortion

between the two socioeconomic groups.

19

One study found that the racial distribution

among abortions in the early weeks of preg

nancy was commensurate with the national

average, while among later abortions the

percentage of blacks was double the national

13/average. Another study of over 31,000 New

York residents found that:

"Race was also found to be associated

with stage of pregnancy. Exactly half

(50.0 per cent) of black women

sought an abortion after the tenth

week of pregnancy. Whereas only one-

third (32.2 per cent) of white women

(including several Spanish American

women) applied for an abortion that

late." 14/

12/ cont'd.

In the first year following legal

ization of abortion, the abortion

rate was 637.8 abortions on nonprivate

services per 1,000 live births, com

pared to 400.6 on private services."

1975 PPFA Study at 71-72 (footnotes omitted).

13/ Kerenyi, Glascock, & Horowitz, Reasons

for Delayed Abortions: Results of 400 Inter-

views 117 AM. J. OBSTET. & GYN. 229 (1973).

14/ Bracken & Swigar, Factors Associated with

Delay in Seeking Induced Abortions, 113 AM.J.

OBSTET. & GYN. 301, 304 (1972).

20

The reason that so many low-income women

seek later abortions is not simply negligence.

Inability to finance an abortion is one sub

stantial reason for delay in seeking an abor

tion. In 1972, the average cost of an abor-

15/

tion in the United States was $332. Although

Medicaid, Medicare and private health insur

ance may cover part of these costs, many low-

income women have no health care coverage

and thus must spend a great deal of time and

effort trying to raise the necessary money.

In a study of health care coverage across

the United States, Spare: and Okada found:

15/ Muller & Jaffe, Financing Fertility-

Related Health Services in the United States,

1972-1978: A Preliminary Projection 4 FAMILY

PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 6, 11 (No. 1, 1972).

21

"Moreover, despite the differential

mix of public programs [Medicaid

and Medicare] and private health

insurance, the proportions of the

poor having no health care coverage

ranged from 11 per cent in Bedford-

Stuyvesant-Crown Heights and Red

Hook to 60 per cent in Charleston;

the proportions of the near-poor

in this category ranged from 14

per cent in Wisconsin to 58% per

cent in Atlanta and Charleston;

and the proportions of non-poor in

this category ranged from 9 per

cent in Wisconsin to 44 per cent in

Atlanta." 16/

This finding is supported by a study of abor

tions in New York City which found that approx

imately 16% of the patients in municipal hos

pitals were required to pay for abortions

17/

entirely from their own funds.

16/ Sparer & Okada, Welfare and Medicaid

Coverage of the Poor and Near Poor in Low In

come Areas, 86 HSMHA [Health Services and Men

tal Health Administration] HEALTH REPORTS 1099,

1105 (1971)

17/ Pakter & Nelson, Abortion in New York City

The First Nine Months 3 FAMILY PLANNING PER

SPECTIVES 5, 7 (No; 3, 1971).

22

"Great hopes for paying abortion

costs should not be held for Medi

caid because of the limited popu

lation it covers and because it is

becoming more restrictive in most

states — 'it is thus, even poten

tially, a source of abortion cost

reimbursement for no more than

14% of medically indigent women of

child bearing age.'" 18/

18/ SARVIS, R., THE ABORTION CONTROVERSY

(1974) at 51, quoting Muller, Health Insur

ance for Abortion Costs; A Survey, 2 FAMILY

PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 12 (No. 4, 1970). An

other study by Professor Wolfe on health

insurance coverage fcmnd that, "In 1968 close

to 30,000,000 persons had no hospital insur

ance, 20% of the population had no insurance

against the costs of surgery, 34.5% had no in-

hospital medical insurance, half the popula

tion had no X-ray or laboratory coverage out

of hospital, and 57.5% were unprotected for

the costs of visits to the physicians' office

or for visits by the physician to the patients'

home." Wolfe, Primary Health Care for the Poor

in the United States and Canada, 2 INT. J .

HEALTH SERVICES 217, 218 (1974). See generally

Mallory, Rubenstein, Drosness, Kleiner,

& Sidel, Factors Responsible for Delay

in Obtaining Interruption of Pregnancy, 40

OBSTET. & GYN. 556, 560 (1972).

23

Many hospitals, particularly municipal hospitals,

have instituted a pay-first policy for their

abortion services, thus insuring that those

women not covered by any health coverage plan

will be forced to delay their abortions while

seeking funds. Kings County Municipal Hospital

in Brooklyn instituted a pay-first policy for

patients not covered by Medicaid. Thirty-seven

per cent of the women applying for abortion

during the first year of the program's opera

tion were not covered by any health coverage

plan and thus had to pay themselves. In the

first year of the abortion service, fifty

patients were rejected on the day of their

scheduled abortions due to their inability

19/

to pay in advance for their abortions.

19/ Walton, Epstein, Gallay, & Nelson,

Development of an Abortion Service in a Large

24

Another reason that low-income women so

19/ cont'd.

Municipal Hospital, 64 AM. J. PUB. HEALTH 77

(1974). Another study of abortions in New York

found financial difficulties to be a chief

cause of delay:

"For [12.5% of those women seeking

abortions] . . . financial diffi

culties represented the only cause

of delay . . . . Many of the women

were aware of their pregnancies in

the first tri-mester but were unable

to accumulate the necessary funds

for a curretage and their trip to

New York. By the time this money

was raised, the pregnancies were

sufficiently advanced to require

saline induction, an even more ex

pensive procedure involving a long

er hospital stay."

Kerenyi, Glascock, & Horowitz, Reasons for

Delayed Abortion: Results of 400 Interviews,

117 AM. J. OBSTET. & GYN. 299, 309 (1973).

This study was completed after New York lib

eralized its abortion law in 1970 but before

the United States Supreme Court's decisions

in Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton. At this

time, travel expenses, often quite substan

tial, had to be added to the cost of abor

tions. The conclusions of the study are still

25

frequently delay in seeking abortions is the

lack of good primary medical care which would

make possible the early diagnosis of preg

nancy.

"The current situation in this

country results in the highest

quantity and quality of medical

care being offered to the middle

and upper socioeconomic classes

who are the lowest risk members

of the population. The poor, who

are the highest risk, have least

adequate care. Impersonal and frag

mented services, accompanied by long

waits and inconveniences, are more

common for this group." 20/

19/ cont'd.

relevant, however, due to the failure of

many public hospitals to provide abortion

services, see notes 4 and 9,supra,thus necessitating

a great deal of travel expenses for many women

who desire abortions.

20/ Osofsky, Poverty, Pregnancy Outcome and

Child Development, 10 BIRTH DEFECTS 37, 45

(No. 2, 1974).

26

[between the health care afforded the poor

and that afforded middle and upper income

groups] are most striking in terms of use of

preventive care such as routine physicals [and]

prenatal checkups . . . . The pattern of care

of low income groups tends to be more sporadic,

21/

fragmented, and crisis oriented." The poor

see less doctors less frequently than do higher

Another study found that " [t]he discrepancies

21/ Smith & Kalozony, Inequality in Health

Care Programs: A Note on Some Structural

Factors Affecting Health Care Behavior, 12

MEDICAL CARE 860 (1974). "Numerous studies

and statistics document the discrepancies

in health care received by poor as opposed to

more wealthy segments of the United States

population. While lower income groups have

substantially more chronic conditions,

restricted activity, and bed disability days

as well as more than twice the infant mor

tality rates of more wealthy segments of the

population, they tend to use health services

less effectively." Ibid.

27

income groups. A survey of the Los Angeles

area revealed that while there were 127

doctors per 100,000 people in Los Angeles,

there were only 38 doctors per 100,000

22/

people in Watts. Moreover, while " [t]wo-

thirds of all children in the United States

see a doctor in the course of a year, only

half of the children from low-income, farm,

or non-white families” see doctors once a

23/

year. Fcr the poor, "the emergency room of

the hospital is increasingly used as a sub-

24/

stitute for primary care."

22/ Wolfe, Primary Health Care for the Poor

in the United States and Canada, 2 INT. J.

HEALTH SERVICES 217, 218 (1974).

23/ Id. at 219.

24/ Ibid.

- 28 -

The frequent lack of adequate primary

medical care often leads to delays by low-

income women in the discovery of pregnancy

and consequent delays in seeking abortions.

A study of prenatal services at a public

hospital whose clientele consists almost ex

clusively of indigent persons in the San

Antonio, Texas, area found that approximately

one half of the pregnant women who utilized

the hospital for prenatal services of all

kinds made their first visit to the hospital

after twenty weeks gestation. Through inter

views, it was determined that their delay in

seeking medical care was due to (1) lack of

transportation, (2) difficulty in finding

care for other children, (3) cost of medical

care, and (4) the inconvenient location and

29

In additionhours of the hospital clinics,

to the delays in diagnosing pregnancy, low-

income women frequently are faced with sig

nificant delays in receiving abortion services

after an unwanted pregnancy is detected. A

study conducted at the Albert Einstein College

of Medicine neighborhood clinic in New York

City found that frequently there was a signif

icant interval between the appointment for an

abortion and the date when the abortion was

actually performed. "Fourteen per cent of the

early abortion patients [up to twelve weeks

gestation] waited more than two weeks from

25/

25/ Gibbs, Martin & Gutierrez, Patterns of

Reproductive Health Care Among the Poor of

San Antonio, Texas, 64 AM. J. PUB. HEALTH 37,

38, 39 (1974).

30

time of appointment to abortion; fourteen

per cent of the late abortion patients [after

twelve weeks gestation] waited in excess of

26/

four weeks." This study concluded that while

55% of the women who had second trimester

abortions delayed for personal reasons, 26%

delayed for reasons which could be attributed

to the medical care system; 11% delayed be-

' <

cause of physician error (misdiagnosis, fail

ure to utilize timely procedures, etc.)/ 9%

delayed because of difficulty in locating an

abortion facility, and 6% delayed because of

27/

problems in securing financing.

26/ Mallory, Rubenstein, Drosness, Kleiner

& Sidel, Factors Responsible for Delay in

Obtaining Interruption of Pregnancy, 40 OBSTET.

& GYN. 556, 559 (1972)(emphasis added).

27/ Id. at 560.

31

(in 1972, almost one-third of all reported

28/

abortions were performed on teenagers) also

accounts for delay in securing abortions.

Moreover, where abortions are difficult to

obtain (as in states with restrictive abor

tion laws before 1973^ there is evidence of

much higher illegitimacy rates among nonwhite

29/

teenagers than among white teenagers.

The youth of many women seeking abortions

28/ PHEW Report: Fewer Out-of-State Abortions

in 1972, 3 FAMILY PLANNING DIGEST 12 (No. 5,

1974). The hysterotomy patient whom appellant

treated was eighteen years old. T. 8— 6.

29/ In the fifteen states which had liberal

ized their abortion laws by 1970, both white

unmarried teenagers and black unmarried teen

agers showed significant declines in the rate

of illegitimate births per 1,000 women (14.4%

and 8.9%, respectively) when the 1965-1970

period was compared to the 1970-1971 period.

By contrast, in states which had not liberal

ized their abortion laws by 1970, the group

of white unmarried teenagers showed a more

modest decline in the rate of illegitimate

births per 1,000 women when the 1965-1970

period was compared to the 1970-1971 period,

32

One final consideration should be noted.

Prior to the liberalization of the abortion

29/cont'd.

presumably because such women were able to

secure abortions in states with liberal laws,

while the group of nonwhite unmarried teen

agers showed a rise in the illegitimacy rate

of 3.3% when these two periods were compared.

Sklar & Berkov, Teenage Family Formation in

Postwar America, 6 FAMILY PLANNING PERSPEC

TIVES 80, 86 (No. 2, 1974). In fact, in the

pre-Roe v. Wade period, "in the states where

abortion was illegal, white women of all age

groups showed declines of at least five per

cent [in the illegitimacy rate], whereas non

white women of virtually all age groups showed

either little change or small rises" due to

the inability of this latter group to avail

themselves of "migratory" abortions (i.e.,

abortions outside their home state) to the

same extent as white women. Ibid. The Sklar-

Berkov study concluded that:

"a number of constraints --

such as ignorance of the legality

of abortion in other states and

the expense of travel to a state

where abortion was legal, coupled

with the costs of and concerns

about abortion itself — limited

the widespread use of migratory

abortion. Poor and nonwhite women

33

laws, deaths due to abortion were the leading

cause of all deaths associated with pregnancy

30/

and birth. Because of their inability to

pay for illegal abortions,

"[Blacks and Puerto Ricans] were

the ones who had been largely

the victims of crude attempts

at abortions by unskilled non

medical individuals, or self

induced by dangerous and des

perate measures. In fact,

deaths among these women com

prised the largest component

of our pregnancy associated

29/ cont'd.

in general, especially if they

were teenagers, probably suffered

most from these constraints and

thus were unlikely to have resorted

to abortion in very great numbers

unless it was legal and readily

available in their state of resi

dence or very nearby."

Ibid.

30/ Pakter, Impact of the Liberalized Abortion

Law in New York City on Deaths Associated with

Pregnancy: A Two-Year Experience, 49 BULL. N.Y.

ACAD. MEDICINE 804, 807 (1973).

34

deaths year after year." 31/

In 1970, the New York State abortion law was

liberalized, and there was a subsequent fifty

per cent decline in the maternal mortality

32/rate." Abortions after the twelfth week

have a complication ratio between 5 and 7

times higher than those performed in the

33/

first twelve weeks, and it is therefore

31/ Pakter, New York's Liberalized Abortion

Law: An 18-Month Summary for New York City,

28 N.Y. MEDICINE 326 (1972).

32/ Glass, Effects of Legalized Abortion on

Neonatal Mortality and Obstetrical Morbidity

at Harlem Hospital Center, 64 AM. J. PUB.

HEALTH 717 (1974). See also Pakter & Nelson,

Abortion in New York City: The First—Nine

Months, 3 FAMILY PLANNING PERSPECTIVES 5 (No.3,

1971) ; Pakter, Impact of the Liberalized

Abortion Law in New York City on Deaths

Associated with Pregnancy; A Two-Year Exper

ience , 49 BULL. N. Y. ACAD. MEDICINE 804

(1973).

33/ Mallory, Rubenstein, Drosness, Kleiner

& Sidel, Factors Responsible for Delay in

35

these later abortions that most need hospital

care and observation. If public hospitals

are deterred from providing second trimester

abortions, the maternal mortality rate is

likely to rise sharply and disproportionately

among low-income mothers who are frequently

unable to obtain earlier abortions and who

will likely be forced once again to risk

serious complications and death in undergoing

"crude attempts at abortion by unskilled non

medical individuals."

33/ cont'd.

Obtaining Interruption of Pregnancy, 40 OBSTET.

& GYN. 556 (1972); Berger, Tietze, Pakter, &

Katz, Maternal Mortality Associated with Legal

Abortions in New York State, July 1, 1970-June

30, 1972, 43 OBSTET. & GYN. 315 (1974); Bracken

& Swigar, Factors Associated with Delay in

Seeking Induced Abortions, 113 AM. J. OBSTET.

& GYN. 301, 302 (1972).

36

Affirmation of appellant1s cpnviction

would severely undercut the constitutional

right of personal privacy recognized in Roe

v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton. Moreover, the

impact would be disproportionately felt by

low-income women who often have great

difficulty in diagnosing pregnancy, obtain

ing funds for an abortion, finding a facility,

and scheduling an abortion. The economic

realities of this nation's health care system

makes it inevitable that poor women as a

group will delay longer in seeking abortions

than women from higher income groups. Medical

care (including abortion services.) for black

and low-income women during pregnancy is

now grossly inadequate. The threat of man

slaughter prosecution of doctors making good-

37

faith medical judgments will further inhibit

public hospitals from providing abortions,

thereby increasing present economic inequities.

The ability to exercise fundamental consti

tutional rights should not depend on economic

status. Cf. Griffin v. Illinois, supra, 351

U.S. at 19. The affirmance of this conviction

would seriously erode for minority and poor

women the guarantee under the Ninth and Four

teenth Amendment of a constitutional right

34/

34/ see Roe v. Wade, supra, 410 U.S. at 165:

"The decision vindicates the right

of the physician to administer

medical treatment according to his

professional judgment up to points

where important state interests pro

vide compelling justifications. Up

to those points, the abortion deci

sion in all its aspects is inherent

ly, and primarily, a medical decision,

and basic responsibility must rest

with the physician. If the individ

ual practitioner abuses the privilege

of exercising proper medical judgment,

38

of personal privacy in medical care during

pregnancy guaranteed by Roe v. Wade and Doe

v. Bolton.

Appellant's conviction should be

reversed.

RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MARILYN HOLIFIELD

DAVID E. KENDALL

PEGGY C. DAVIS

LINDA GREENE

ATTORNEYS FOR AMICUS CURIAE

34/ cont'd.

the usual remedies, judicial

and intra-professional are

available."

39