Brief in Support of Answer to Emergency Motion

Public Court Documents

December 6, 1972

43 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Brief in Support of Answer to Emergency Motion, 1972. d6fcb1be-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb581a16-fb26-4806-bd47-7434ca29e1d8/brief-in-support-of-answer-to-emergency-motion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

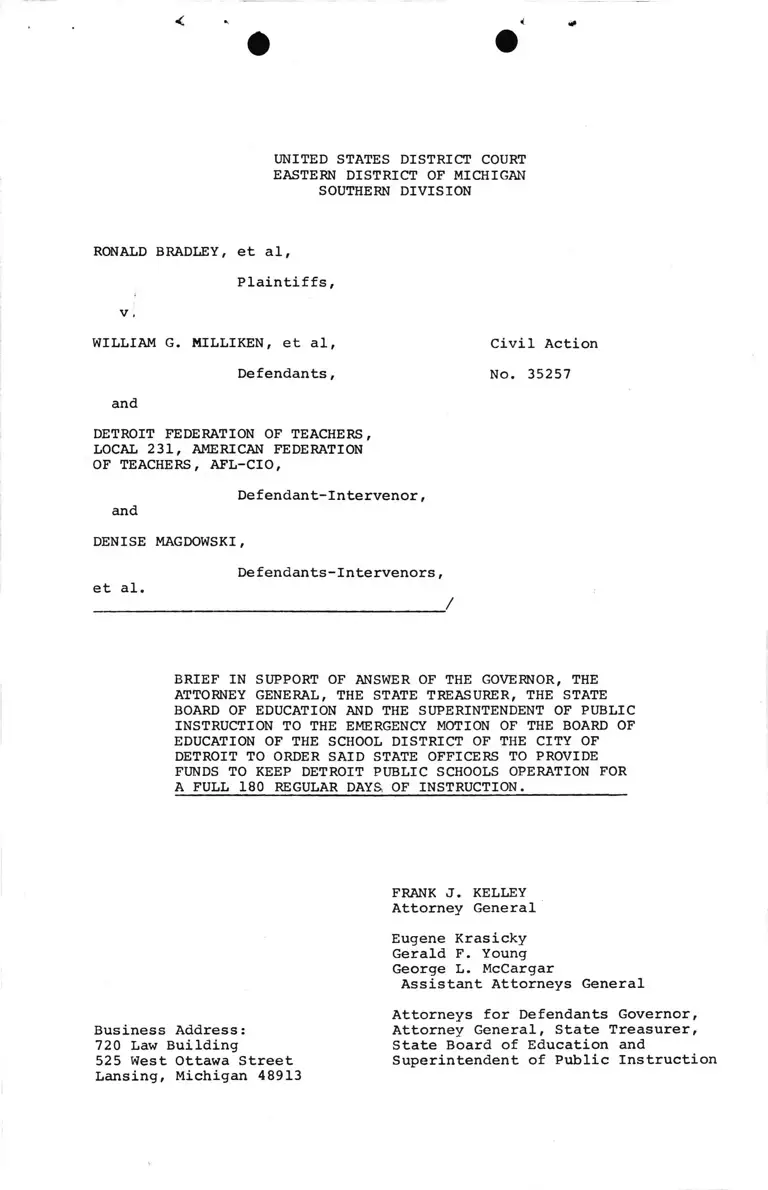

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs,

v ,

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants,

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI,

Defendants-Intervenors,

et al.

______________________________________________ /

Civil Action

No. 35257

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF ANSWER OF THE GOVERNOR, THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL, THE STATE TREASURER, THE STATE

BOARD OF EDUCATION AND THE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION TO THE EMERGENCY MOTION OF THE BOARD OF

EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF

DETROIT TO ORDER SAID STATE OFFICERS TO PROVIDE

FUNDS TO KEEP DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOLS OPERATION FOR

A FULL 180 REGULAR DAYS, OF INSTRUCTION.

Business Address:

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

George L. McCargar

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for Defendants Governor,

Attorney General, State Treasurer,

State Board of Education and

Superintendent of Public Instruction

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs, v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al, Civil Action

Defendants, No. 35257

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

and Defendant-Intervenor,

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.

et al. Defendants-Intervenors,

/

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF ANSWER OF THE GOVERNOR, THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL, THE STATE TREASURER, THE STATE

BOARD OF EDUCATION AND THE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC

INSTRUCTION TO THE EMERGENCY MOTION OF THE BOARD OF

EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF

DETROIT TO ORDER SAID STATE OFFICERS TO PROVIDE FUNDS

TO KEEP DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOLS OPERATING FOR A FULL

180 REGULAR DAYS OF INSTRUCTION.

I.

A. There is no present real emergency.

Defendant Board of Education of the School District of

the City of Detroit pleads an emergency requiring the immediate

attention of this Court. Yet a careful reading of its motion

compels the conclusion that there is in fact no present emergency.

By its own admission (paragraph 6 of the Motion, the first full

paragraph on page 6,of the affidavit of Harold Brown and the

third paragraph of page 1 of the affidavit of Superintendent Wolfe)

*

the Detroit Board of Education has sufficient funds to keep its

schools open and provide an educational program for its pupils

until at least March 15, 1973. It has sufficient funds because

under state law, 1972 PA 258, Chap 13, MCLA 388.1231 et seq;

MSA 15.1919(631) et seq,

it has borrowed from financial institutions and has pledged

future state aid payments, and under 1972 PA 258, § 136,

MCLA 388.1236; MSA 15.1919(636), an advance of state aid payment

has been authorized by the State Administrative Board on condition

that the Detroit Board of Education keep operating its schools

without closure in January and February, 1973. Obviously there

would be no need for the State Administrative Board to make such

an advance of state school aid payment in December of 1972 if the

schools of the defendant Detroit Board of Education were to be

closed December 21, 1972, all of January of 1973 and not reopen

until February 19, 1973. It is noted that the Governor, the

Attorney General, the State Treasurer, and the Superintendent of

Public Instruction are voting members of the State Administrative

Board and acted upon November 21, 1972 to authorize such an advance

to permit the Detroit public schools to keep in operation. See

Exhibit A to the Affidavit of Robert McKerr.

Thus these state defendants have been exercising powers

conferred upon them by Michigan law to assist the defendant

Detroit Board of Education to operate its schools for the requisite

180 days as mandated by Michigan law. 1955 PA 269, § 575, MCLA

340.575; MSA 15.3575.

Indeed this statute requires that a school district failing

to provide 180 days of student instruction shall forfeit 1/180 of

its total state aid for each day of such failure from state aid

payments to be made in the subsequent school year. If defendant

- 2 -

«* *

Detroit Board of Education is permitted to operate less than

180 days for the current school year as authorized by its board

(see page 2 of affidavit of Charles J. Wolfe), such Michigan law

will mandate the forfeiture of 1/180 of the state aid to be paid

the school district in the 1973-74 school year for each day under

180 days. Thus closure of the Detroit schools from December 21,

1972 to February 19, 1973, will contribute to a horrendous financial

problem for the school year 1973-74.

In large part the financial plight of the Detroit School

District is due to the inability of the defendant Detroit Board of

Education to lead its school electors to vote sufficient taxes, at

least to the state average of 24 mills, so that the school district

could afford to pay the comparable salaries it is paying its teachers

based upon the average salaries paid teachers by the seven highest

1

salary school districts in Wayne,sMacomb and Oakland counties. It

is undisputed that for 1972-73 Detroit is levying only 15.5 mills

on each dollar of its assessed valuation as state equalized, while

most of the seven highest districts in such three county area have

been levying at least 24 mills or more. Moreover, even though the

defendant Detroit Board of Education has not provided a general

increase to its teachers in 1972-73, it nevertheless is paying

salary increases by way of increments to many of its teachers

during such fiscal year although it is abundantly clear that it

was in no financial position to do so. In addition, it has entered

into contracts with its teachers other than first year teachers

that gives them contractual rights to collect their salaries for

January and February of 1973, although such contracts may be

^See Affidavit of Robert McKerr.

- 3-

terminated by giving 60 days notice prior to April 15, 1973, with

( /

no contractual obligation to make salary payments after April 15,

1973. Thus it must be concluded that if the Detroit schools close

during January and the major part of February, 1973, the teachers

under contract will have contractual rights to be paid, even

though the children receive no education during such period.

Here, it must be stressed that, as set forth in Appendix A,

attached hereto, the Detroit Federation of Teachers has served

notice that, in the event the Detroit schools are closed during

this period, it will seek a money judgment against defendant,

Detroit Board of Education, based on the contractual rights of

the teachers to be paid during such period. Therefore, it can

hardly be claimed that the decision to close on December 21, 1972

to February 19, 1973 is in the best educational interests of the

children of the school district and will result in substantial

savings to the Detroit school district. Such savings are illusory

in light of the teachers' contracts.

The emergency motion of the defendant Detroit Board of

Education does not inform this Court of the efforts of these

state defendants other than to authorize the advance of the state

aid payment. By their silence, the motion-suggests that the state

defendants are not concerned about the educational well-being of

280,000 children being educated in the Detroit school district.

The efforts of the state defendants have been varied and many.

They will be described in the next portion of state defendants' brief.

Based upon the admissions of the defendant Detroit Board of

Education, it is undisputed that there is no real present emergency

in the Detroit school district. It is under contract to pay its

teachers for the months of December, 1972, and January and February

of 1973, and it has the necessary funds to pay such teachers for

said period and to operate the schools.

- 4-

Moreover, on November 30, 1972, the following joint

statement was issued by House Speaker William A. Ryan, House

Minority Leader Clifford H. Smart, House Appropriations Committee

Chairman William R. Copeland, Senate Republican Leader Robert

VanderLaan, Senate Democratic Leader George S. Fitzgerald, Senate

Appropriations Committee Chairman Charles 0. Zollar and Senate

Democratic Flobr Leader Coleman A. Young:

"Members of the Michigan Legislature are aware of

and concerned about the financial difficulty facing

the Detroit Public School Board in attempting to

fulfill its legal obligation to provide 180 days

of education for nearly 1/7 of the state's school

children. In fact, there are strong feelings among

legislative leaders as well as other members that

the Legislature must act to prevent a drastic

reduction of educational services to children in

Detroit and the many other school districts where

deficits threaten a shortened school year.

"As leaders in our respective caucuses, we pledge today

to give top priority to a speedy solution early in the

next legislative session to the financing of the

required full 180-day school year for all Michigan

schools for the 1972-73 school year and express

considerable confidence that we will meet with

success in this effort. We further express our

determination to simultaneously arrive at absolution

to the long-range financing of schools throughout

Michigan, without which there would be a disastrous

continuation of fiscal crises.

"We trust that this commitment to work out a legis

lative solution to the iiomediate financial crisis

facing Detroit schools wj.ll encourage the Detroit

School Board to reconsider its decision to close

schools for 35 school days beginning December 21

and resolve to give the Legislature the time needed

to fashion a reasonable solution."

See Appendix B attached hereto.

Thus, in light of the foregoing, it is simply the height

of irresponsibility for defendant Detroit Board of Education to

consider closing its schools to its pupils during January and

February of 1973.

- 5-

B. State defendants have been assisting

the Detroit School District and the

relief requested against them is both

unnecessary and without authority.

i

It must be observed that a fair reading of the emergency

Imotion of said defendant and the accompanying affidavits of Charles

J. Wolfe and Harold Brown appears to suggest that the only action

taken by the state defendants to date to assist the Detroit school

district was to authorize an advance of state aid and nothing more.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

State defendants have appended to their response in

opposition to the emergency motion of the defendant Detroit

Board of Education the affidavit of Robert McKerr, Associate

Superintendent for Business and Finance of the Michigan Department

of Education, describing in minute detail the many and varied

efforts of the state defendants from January 17, 1972 to date, to

assist the defendant Detroit Board of Education to resolve its

financial problems so that it could provide 180 days of instruction

for its children. Because of the emergency nature of the motion

filed by the defendant Detroit Board of Education and the urgent

need to file our response without delay, the actions of the state

defendants will not be recited here at length. Thus we direct the

careful attention of the Court to the affidavit of Robert McKerr.

Suffice it to say that the actions of the state defendants have

been varied and many.

It would be well to emphasize the meetings of the state

defendants with representatives of the defendant Detroit Board of

Education on November 10, 1972, where ways and means were explored

to continue operations of the Detroit schools through March 15, 1973

by means of the loan from financial institutions pledging state aid

- 6-

payment and the advance of state aid authorized by the State

Administrative Board on November 21, 1972. See Exhibit A/ ■

appended to the Affidavit of Robert McKerr. Of great significance

also is the meeting called by the Citizens Research Council on

November 21, 1972, attended by the state defendants or their

representatives, representatives of the defendant Detroit Board

of Education, and leaders of the legislature, including, but not

limited to, the Speaker of the House, the Majority Leader of the

Senate, the chairmen of the House and Senate Appropriations

Committees and various members of legislative Education and

Taxation Committees. This was a very productive meeting not

only to consider the financial plight of the Detroit School

District and its ability to provide 180 days of student instruction,

but more importantly, the meeting considered various approaches

to provide the legislative means for the Detroit School District

to operate a 180 day school year.

It is, therefore, abundantly clear that the legislature

is fully informed of the financial situation of the Detroit School

District and there is every reason to believe that the legislature

will provide the means for the Detroit School District to operate

a 180 day school year during the 1972-73 school year. It should be

stressed that the legislature needs time to consider and resolve

t

the problems, and that the nature of the means, whether by loan,

power to tax, grant or otherwise, rests in the discretion of the

legislature. The joint statement of legislative leaders from

both parties and both houses issued November 30, 1972,(Appendix B),

is proof positive that, given sufficient time, the Michigan

legislature will respond to the financial plight of the Detroit

School District.

- 7-

At all times in furthering the interests of defendant

Detroit Board of Education in providing 180 days of school for

its 280,000 pupils, the state defendants have acted within their

scope of powers as conferred by law. However, the power to tax

and appropriate funds is vested by the people in the legislature.

Const 1963, art 9, §§ 1, 11 and 17.

Responding to paragraph 12A of the emergency motion,

defendant Detroit Board of Education therein suggests an order

directing the Governor to call the legislature into special session.

The legislature is in present session. Journal of the House, 1972,

p 2988; Journal of the Senate, 1972, p 2027.

By concurrent resolution the legislature has voted to

adjourn sine die on December 29, 1972, at 12:00 noon. House Journal,

p 2708, September 6, 1972.

The authority of the Governor to convene the legislature

into special Session is conferred by Const 1963, art 5, § 15.

Clearly, the purpose of art 5, § 15 is to empower the Governor to

convene a legislature not in session. It, therefore, must follow

that the Governor does not have the power to convene the legislature

while it is in session.

Therefore, it must follow that an emergency order of this

Court directing the Governor to call the legislature into session

is wholly unnecessary, without lawful authority and should not be

granted. The legislature has already committed itself to giving

top priority to a speedy solution to this financial problem in the

next legislative session commencing in early January, 1973.

See Const 1963, art 4, § 13.

- 8-

Turning to paragraph 12B of the emergency motion, as to the

reviewing and reporting to the Court the possibilities of diverting

existing state funds, including state aid to schools, state

defendants would respond to the policy questions in this portion

of the brief and to their lack of legal authority to divert funds

in another portion of the brief, infra.

Addressing the possible diversion of state aid funds

first, the legislature has enacted 1972 PA 258, MCLA 388.1101

et seq; MSA 15.1919(501) et seq. Under Section 21, the legislature

has made the basic appropriations for Michigan school districts

based upon the assessed valuation of school districts so that

larger state aid grants are made to poorer districts. As provided

in Section 17, two installments of state aid have been paid and the

third of six installments is to be paid on December 1, 1972.

Countless school districts, like Detroit School District, have

borrowed from financial institutions and have pledged state aid

to be received as provided by the legislature in §§ 131 - 135 of 1972

PA 258, supra, while some school districts, including Detroit, have

received advances of state aid as authorized by 1972 PA 258, § 136,

supra.

School districts have relied upon 1972 PA 258, supra, to

plan their budgets, contract with teachers and otherwise operate

their schools as required by state law. To divert funds from 1972

PA 258, supra, from other Michigan school districts who are levying

an average of 24 mills for operating purposes to make such funds

available to the defendant Detroit Board of Education, which is

levying only 15.5 mills for operating purposes, would not only be

unjust and inequitable to Michigan school districts, but would

create financial and legal chaos to Michigan education generally,

and deprive children in many school districts levying 24 mills

- 9-

for operating purposes of 180 days of education as required by

Michigan law.

It is respectfully submitted that from a policy stand

point, diversion of state aid funds during the middle of a school

fiscal year from other Michigan school districts to defendant

Detroit Board of Education is unwise as destructive of educational

opportunity for all children in the state of Michigan. Moreover,

this is a policy decision reposed in the sound discretion of the

Michigan legislature, not the state defendants.

As to the diversion of other state funds, even if the

state defendants had the power to do so, which they do not, a

similar policy argument must be made. The Governor and the legis

lature have considered the needs of all state agencies and services.

Budget bills have been enacted into law and moneys appropriated

thereunder have been expended to feed and house the poor, the ill,

the aged and the mentally incompetent. In addition, education is

being provided on the college and university levels and other

needed state services are being provided the people of this state.

Almost five months of the state fiscal year have elapsed. Contracts

have been let and obligations incurred. To request the state defendants

to divert any of these funds is not only an impossible task but not

in the best interests of all of the people of this state. Where do

we begin to divert funds? The legislature has weighed the competing

interests in determining the appropriations. The diversion of other

state funds at this time would be unwise and destructive of orderly

provision of vital state services. Moreover, again this is a policy

decision reposed, under Michigan law, in the sound discretion of the

Michigan legislature, not the state defendants.

- 10-

m

It must be concluded, therefore, that the state defendants

are doing everything within their lawful authority to assist the

defendant Detroit Board of Education to provide 180 days of

instruction for their pupils in the current school year. An order

of this Court to continue doing this is unnecessary. The Governor

is without lawful authority to convene the legislature in special

session since the legislature is in session presently and will continue

in session until at least December 29, 1972, when it intends to adjourn

sine die. It is manifestly unwise to consider ordering the state

defendants to divert state funds, including state school aid funds,

to the defendant Detroit Board of Education. Moreover, only the

legislature has the power to divert appropriations made by it or

to make any further appropriations. Further, the questions of

ascertaining whether there are additional unappropriated funds in

the state general fund and, if so, whether some of such funds

should be appropriated to the Detroit School District are reposed,

under Michigan law, in the discretion of the Michigan legislature.

II.

A. The lawful power to assist the defendant

Detroit Board of Education in obtaining

funds to provide 180 days of student

instruction for the 1972-73 school year

is reposed in the Michigan legislature,

not a party defendant herein.__________

At the outset of this portion of the brief, it must be

emphasized that the prayer for relief in the emergency motion here

under consideration contains, inter alia, the following:

"3. Find as Fact and Conclude as Law that the

named State Defendants in this cause have the

power, augmented by the equitable power of this

Court, to provide the additional wherewithal

necessary to implement the order of July 7, 1972

without any further action by the Michigan State

Legislature.

- 11-

"4. Order aforesaid State Defendants to present

within 10 days of the issuance of this Order a plan

for the exercise of such authority.

?5. Hold hearings forthwith to consider such plan

and any modifications that may be suggested by

additional parties.

"6. Order the implementation of said plan, with such

modifications as the Court may deem appropriate after

hearings no later than February 1, 1973, provided

that the Michigan State Legislature has not first

acted to provide the necessary wherewithal to allow

the continued operation of the Detroit Public Schools."

[Emphasis supplied! pp 11-12

Further, in the memorandum filed in support of its emergency

motion, defendant Detroit Board of Education states the following:

"Thirdly, it would be imprudent not to consider

the impact of this action on the State Legislature.

The Detroit Board readily admits that by far the

best place for the current problem to be solved is

in the State Legislature, and sincerely hopes that

that body does provide a solution, which in its"

wisdom and expertise is the most workable^ YeT,

as noted above, the pronouncements of legi'slative

leaders do not indicate that that body is eager to

assume the responsibility clearly placed upon it

by the Constitution of the State of Michigan to

provide for a free public education. . . . "

[Emphasis supplied] p 9

a fair

motion

Thus, the following conclusions are patently obvious from

reading of defendant Detroit Board of Education's emergency

and memorandum in support thereof:

1. Defendant Detroit Board of Education is asking

this Court to order the state defendants to

provide approximately 80 million dollars in additional

state funds for the Detroit schools. The phrase

"additional wherewithal" in the prayer is a

euphemism that serves only to obfuscate the

issues before this Court.

2. Yet, defendant Detroit Board of Education

recognizes, as it must, that the Michigan

-12

legislature is the only body with the

authority, under Michigan law, to appropriate

the funds or provide other means whereby the

schools in Detroit may remain open for 180

days during the 1972-73 school year.

Further, in light of the Joint Legislative Statement

issued on November 30, 1972 (Appendix B), it is beyond dispute that

the Michigan legislature has unequivocally demonstrated its intent

to come to grips with the fiscal plight of the Detroit schools in

the next legislative session, on a priority basis, and provide some

method of legislative relief so that Detroit's school children will

have 180 days of school.

Turning to Michigan law, it is crystal clear that the

power to appropriate state funds to school districts, whether from

the state school aid fund or the general fund, is reposed in the Michigan

legislature. Further, it is equally clear that funds appropriated by

the legislature must be paid out by the state defendants herein in

accordance with the statutes appropriating such funds to school

districts as prescribed by the legislature.

In Const 1963, art 9, § 17, the people have provided:

"No money shall be paid out of the state treasury

except in pursuance of appropriations made by law."

Further, Const 1963, art 4, § 30 provides:

"The assent of two-thirds of the members elected

to and serving in each house of the legislature

shall be required for the appropriation of

public money or property for local or private

purposes." 2

^We make no claim that a 2/3 vote is required to appropriate

funds to Michigan school districts but only cite this provision

to show that, demonstrably, the power of the purse is in the

legislature. See also Const 1963, art 3, § 2, setting forth the doctrine of separation of powers for Michigan government.

13-

*

In addition, Const 1963, art 8, § 2 states in

pertinent part, the following:

"The legislature shall maintain and support a

system of free public elementary and secondary

schools as defined by law."

The Address to the People accompanying this constitutional

provision contains the following language:

"This is a revision of Sec 9, Article XI, of the

present [1908] constitution which fixes respon

sibility on the legislature to provide 'primary'

education. To conform to present practice and court

interpretations, 'primary' is changed to 'elementary

and secondary.' The balance of the section is

excluded because its restrictions as to finance

and definitions as to basic qualifications needed

to be eligible for state aid are better left to

legislative determination. I I 7" [Emphasis supplied]

Moreover, in Const 1963, art 9, § 11, which establishes

the state school aid fund, the people there provided:

"There shall be established a state school aid

fund which shall be used exclusively for aid to

school districts, higher education and school

employees' retirement systems, as provided by

law. .One-half of all taxes imposed on retailers

on taxable sales at retail of tangible personal

property, and other tax revenues provided by law,

shall be dedicated to this fund. Payments from

this fund shall be made in full on a scheduled

basis, as provided by law.-11 [Emphasis supplied]

The Address to the People accompanying this constitutional

provision contains, inter alia, the following:

"This is a new section which directs the

legislature to establish a school aid fund to

which must be dedicated one-half of all state

sales tax collections and such other revenues

as the legislature may determine. Moneys in the

fund must be used for support of education and

school employees' retirement systems. Payments

from the fund are to be made in full on a basis

scheduled by legislative enactment"! I ! T71

[Emphasis supplied]

-L4-

t

A unanimous Michigan Court of Appeals has declared

the following:

. . A further indication that the plaintiff

is a public institution is found in Const 1963,

art 8, § 4, which provides, 'The legislature

shall appropriate moneys to maintain the

University of Michigan,' and we recognize that

the legislature dees each year appropriate

moneys to maintain the plaintiff. These

moneys are tax moneys derived from general

taxation on all of the people of this state,

and the legislature is the only body that has

the power to appropriate the public funds of

this state. . . ." [Emphasis supplied]

Regents of University of Michigan v Labor

Mediation Board, 18 Mich App 4~85, 490 (1969).

More recently, in an unreported order attached hereto

as Appendix Cr (Michigan Education Association, et al v State Board

of Education, et al, Court of Appeals No. 11900, order issued

July 8, 1971), in a case involving an attempt to mandamus the

State Board of Education and the Michigan legislature to appro

priate additional funds to several Michigan school districts, the

Court of Appeals, in denying such relief, squarely held:

"IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the motion for

order to show cause as to the members of

the State Board of Education and the Super

intendent of Public Instruction in their

official capacities be, and the same is

hereby DENIED, it appearing to the Court that

plaintiffs have not demonstrated defendants'

failure to perform a clear legal duty, and

further that expenditure of the state

general funds is solely within the province

of the Legislature; Welling v Livonia Board

of Education (ltyogj, 382 Mich 620, Detroit

Board of Education v Superintendent of

Public Instruction, supra; Const 1963,

art 9, § 17." [Emphasis supplied] p 2 of order.

These two unanimous decisions of the Michigan Court of

Appeals, along with Detroit Board of Education v Superintendent of

Public Instruction, 319 Mich 436 (1947), are controlling and must,

it is respectfully submitted, be followed.

>• ' : ..X

- 15-

Thus, under Michigan law, only the Michigan legislature

may lawfully appropriate, allocate and direct the disbursement of

state funds to school districts. The state defendants herein;

possess no authority to do so. Consequently, this Court may not

compel the state defendants herein to appropriate, allocate or

disburse state funds to the Detroit School District in contravention

of the statutes enacted by the Michigan legislature providing for

state school aid appropriations to school districts.

In short, only the Michigan legislature may provide

financial assistance to the Detroit Board of Education to operate

for 180 days during this school year. In modern times, the Michigan

legislature has always responded positively to the financial crises

of school districts and other educational institutions in a manner

that has enabled them to avoid closure during the school year. It

has done so in different ways.

As to school districts incurring deficits and facing

closure, the legislature has provided for emergency assistance

through the provision of 1968 PA 32, MCLA 388.201 et seq; MSA

15.1916(101) et seq. Upon a certified audit of the State Treasury

Department that the school district is insolvent (Sec 4) the board

of education of such a school district is eligible to receive an

emergency loan from the state of Michigan and it shall issue bonds

in the amount of the emergency loan made payable to the state of

Michigan to be repaid in not more than 10 years plus interest.

This statute also created an emergency loan fund in the sum of

$1,500,000.00 (Sec 19). Under Sec 20 of 1968 PA 32, supra, this

act expired on June 30, 1970,

More recently the legislature has enacted 1972 PA 225,

MCLA 388.221 et seq; MSA 15.1919(251) et seq, to provide for

- 16- \

emergency assistance for insolvent districts. Under Sec 3 the

board of education of a school district that incurs a deficit

which is attributable at least in part to annual tax collections

on tax settlement day of less than 85% of ad valorem taxes levied

by the district, upon a certified audit of the State Treasury

Department that the district is insolvent, is eligible to receive an

emergency loan. The school district shall issue bonds in the amount

of the emergency loan made payable to the State in equal installments

in not more than 10 years, plus interest at the rate of 6% per annum.

The legislature has appropriated from the general fund to the school

emergency loan revolving fund the sum of $300,000.00 (Sec 19) and

has provided that the act shall expire June 30, 1973 (Sec 20). It

is noted that, aside from the modest appropriation of $300,000.00

made to the school emergency loan revolving fund under 1972 PA 225,

supra, the statute is limited to school districts in an emergency

condition attributable at least in part to an unusually low tax

collection. It is demonstrable that the school district of the

City of Detroit has a tax collection rate in excess of 95% so that

it is presently ineligible for an emergency loan under 1972 PA 225,

supra.

Under both legislative approaches to school deficits and

closures, the legislature has in the past made emergency loans to

insolvent school districts by 1968 PA 32, supra, and 1972 PA 225,

supra, and has required the school district to issue bonds made

payable to the State of Michigan and has specified that such "bonds

shall also be the full faith and credit obligations of the school

district and all taxable property within the school district shall

be subject to the levy of ad valorem taxes to repay the principle

and interest obtained under the bonds without limitation as to rate

or amount." 1968 PA 32, § 6, supra, and 1972 PA 225, § 6, supra.

- 17-

As another legislative approach to a deficit of a

public educational institution and threatened closure, the

attention of the Court is directed to the plight of Wayne County

Community College, which was confronted with closure in the

fiscal year 1970-71 because of a deficit in excess of 2 million

dollars. It is noted that the Wayne County Community College

district was established by the legislature pursuant to 1966

PA 331, §§ 81-84, MCLA 389.81-84; MSA 15.615(181)-(184), but

its board of trustees is without statutory power to levy any

taxes because its electors have not approved a tax rate. Thus,

the community college district is entirely dependent upon tuition,

fees and appropriations from the legislature. The legislature,

pursuant to its constitutional power, first enacted 1971 PA 39,

to make a supplemental appropriation of $400,000 for Wayne County

Community College and thereafter enacted 1971 PA 115 to appropriate

the sum of $1,873,434.91. These supplemental appropriations

permitted that educational institution to continue its operation

without closure. Such sums were in addition to the general appro

priations for operation of the community college made pursuant

to 1970 PA 83 in the amount of $2,712,225.00.

No representation is made, indeed can be made, that the

legislature will make a grant of any additional moneys to the

Detroit School District, since only the legislature can determine

what grants, if any, can be made to the school district. However,

based upon meetings held with legislative leaders, state defendants

and the Detroit school officers, together with the joint statement

issued by legislative leaders on November 30, 1972, there is every

reason to believe that the legislature will respond with some means

for Detroit to provide 180 days of schooling for its children for

the school year 1972-73. Whether the legislature will provide

- 18-

emergency

- J

/

assistance for the Detroit school district by way of

authorizing a loan, either from private financial institutions

or the state of Michigan, and the issuance of bonds and the

statutory authority to levy taxes to pay off such financial

indebtedness, or by way of a grant, or by a combination of methods,

is solely within the discretion of the legislature. In any event,

it is clear that the legislature must have sufficient time to deal

with the problem.

B. None of the state defendants possess any authority to divert already appropriated

state school aid funds from other school

districts to the Detroit School District.

In 1972 PA 258, MCLA 388.1101 et seq; MSA 15.1919(501)

et seq, hereinafter referred to as the state school aid act of

1972, the legislature has made appropriations of state school aid

funds to school districts.

Sections 11, 21(1) and (2) and 0-7) of the state school

aid act of 1972, supra, provide the following:

"Sec. 11. There is appropriated from the school

aid fund established by section 11 of article 9

of the constitution of the state for each fiscal

year, the sum necessary to fulfill the requirements

of tliis act, with any deficiency to be appropriated

from the general fund by the legislature. The appro

priation shall be allocated as provided in this act."

"Sec. 21. (1) Except as otherwise provided in this

act, from the amount appropriated in section 11 there

is allocated to every district a sum determined as

provided in subsection (2) plus the amounts allocated

for transportation in chapter 7 and tuition in

chapter 11.

"(2) The sum allocated to each school district

shall be computed from the following table:

- 19-

State equalized

valuation behind Gross Deductible

each child Allowance Millage

(a) $17,750.00 $644.00 16

or more

(b) Less than $715.00 20

$17,750.00

"Sec. 17. On or before August 1, October 1,

December 1, February 1, April 1 and June 1, the

department [of Education] shall prepare a

statement of the amount to be distributed in

the installment to the districts and deliver

the statement to the state treasurer, who shall

draw his warrant in favor of the treasurer of

each district for the amount payable to the

district according to the statement and deliver

the warrants to the treasurer of each district."

Thus, it is beyond dispute that payments to school

districts under the state school aid act of 1972, supra, must be

made in accordance with the statutory formula contained therein.

Further, the law is settled in Michigan that mandamus will issue

to compel the State Board of Education to disburse state school

aid funds to school districts in the amounts called for by the

provisions of the statute appropriating funds to school districts'..

Manistique Area Schools v State Board of Education, 18 Mich App 519

(1969), Leave to Appeal denied 383 Mich 775 (1970).

In Manistique, supra, in granting the writ of mandamus,

the Court squarely held as follows:

"Thus, it is defendant who has the clear legal

duty of making the apportionment and distributing

school aid according to the statute. The question

that must be determined is whether the defendant has

complied with the legal mandate which the statute

has imposed upon it. . . . " p 522.

Therefore, it is abundantly clear that the duty to allocate

and disburse funds to school districts under the state school aid

act of 1972, supra, is a ministerial duty that must be done in

accordance with the statutory formula for allocating funds to each

school district set forth therein. In short, none of the state

- 20-

%

defendants possess any lawful authority to divert funds from

other school districts to the Detroit school district under the

state school aid act of 1972, supra.

It is equally clear that there is no authority for the

state defendant to direct any other state funds to the defendant

Board of Education except as authorized by the legislature. See

authorities cited in part II A of the brief.

C. The federal courts will not order state officials

to perform acts that are beyond their lawful

power to perform under state law._______________

The relief sought by defendant Detroit Board of Education

is an order of this Court compelling the state defendants to provide

approximately 80 million dollars in additional state funds to the

Detroit schools. As demonstrated above, this is beyond the lawful

authority of the state defendants to do under Michigan law. Further,

the cases cited by defendant Detroit Board of Education in supportl

of such relief are not authority for the type of coercive mandatory

injunctive relief to provide state funds from the state treasury

sought herein. To the contrary, the law is settled that the federal

courts will not order state officials to perform acts that are beyond

their authority to perform under state law.

m Griffin v County School Board of Prince Edward County,

377 US 218 (1964), involving the closure of public schools in one

county, to avoid school desegregation, while in the other counties

the public schools remained opened, the Supreme Court held the

following:

" . . . The Board of Supervisors has the special

responsibility to levy local taxes to operate

public schools. . . . For the same reasons

the District Court may, if necessary to prevent

further racial discrimination, require the Super

visors to exercise the power that is theirs to

levy taxes to raise funds adequate to reopen,

operate and maintain without racial discrimination

- 21-

i

m #

t

a public school system in Prince Edward County

like that operated in other counties in Virginia."

[Emphasis supplied] pp 232-233

The rulings of the District Court in United States v

School District 151 of Cook County, Illinois, 301 F Supp 201

(ND 111, 1969), aff'd as modified 432 F2d 1147 (CA 7, 1970),

cert den 402 US 943 (1971), and the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals in Plaquemines Parish School Board v United States,

415 F2d 817, 833 (CA 5, 1969), merely reiterate the holding in

Griffin, supra, that federal courts may compel those state and

local governmental officials over whom they have jurisdiction to

exercise their powers under state law to prevent the violation

of Fourteenth Amendment rights.

In Thaxton v Vaughn, 321 F2d 474 (CA 4, 1963), in a suit

to desegregate a municipal nursing home and armory, a unanimous

court held:

". . . As he has no authority to act alone, a

decree entered solely against the City Mayor

would not have the effect of granting complete

or even effective relief to the plaintiffs.

The relief requested by the plaintiffs could

not possibly be granted effectively in the

absence of either the City or the Council, or

other appropriate defendants, and a court,

particularly in an equity action, ought not

grant relief against a public official unless

its order will be effective. [Citations omitted]

. . . " pp 477-478

State defendants strongly urge that federal courts may

only order state officials, over whom they have jurisdiction, to

exercise such powers as they possess under state law. Bradley v

School Board of the City of Richmond, Virginia, 51 FRD 139

(ED Va, 1970) .

"To be sure, state officials may only be

directed, in fulfillment of this duty [to

desegregate schools], to use those powers

granted to them by state law. For this

reason the relief which may be demanded of

state, as opposed to local officials is

- 22-

< i

restricted. Smith v North Carolina State

Board of Education, Misc. No. 674 (4th Cir.,

July 31, 1970) . . . In each case, however,

the obligation is commensurate with the scope

of the power conferred by state law." p 142.

Moreover, an analysis of the arguments put forth by

defendant Detroit Board of Education will demonstrate that it

agrees with the proposition that the federal courts may only

compel state and local governmental officers and agencies to

perform those acts they have the authority to perform under

state law.

Pursuant to Section 196 of 1955 PA 269, as amended,

MCLA 340.1 et seq; MSA 15.3001 et seq; defendant Detroit Board of

Education determines the amount of taxes to be levied for school

operating purposes. Further, in Hertzog v City of Detroit, 378

Mich 1 (1966), the Michigan Supreme Court declared:

"The board of education alone determines the

annual tax needs of the school district. CLS

1961, § 340.196 (Stat Ann 1959 Rev § 15.3196).

The city of Detroit performs the ministeral

task of collection. The board of education is

limited in the amount thclt may be collected for

it. Article 9, § 6, of the Michigan Constitution

of 1963 establishes a 15-mill maximum tax rate

which, together with millage authorized by the

city charter, is the limit past which no property

can be taxed without a vote of the property owners.

(See, generally, CL 1948 and CLS 1961, § 211.201

et seq. [Stat Ann 1960 Rev and Stat Ann 1965

Cum Supp § 7.61 et sec[. ]) . Where the maximum millage is reached, each 'local unit' (CLS 1961,

§211.202 [Stat Ann 1965 Cum Supp §7.62]) receives a

given number of mills with the surplus left over

being allocated among 'local units' according to

their needs. (CLS 1961, §211.211 [Stat Ann 1965

Cum Supp §7.71]). Whenever this amount proves

insufficient as it has in Detroit, unless the

property owners authorize a millage increase,

the local unit, i.e., in this case the board of

education , must do without. . . . " p 19

In paragraph 5A of its motion, defendant Detroit Board of

Education states that it has unsuccessfully submitted four millage

- 23-

i

proposals to the electorate in 1972 to both renew expiring millage

and obtain authority to levy additional millage. These millage

elections were required under the 15-mill limitation on general

ad valorem property taxes contained in Const 1963, art 9, § 6

in order to obtain lawful authority, under state law, to increase

the property tax limitation for school operating purposes. Thus,

in the face of the preliminary injunctive order of July 7, 1972,

entered herein and an impending inability to provide its pupils

with 180 days of instruction due to lack of funds, the Detroit

Board of Education has considered itself bound by Michigan law and

it has not sought to levy general ad valorem property taxes above

the 15.5 mills it has the lawful authority to levy under Michigan law.

Rather, defendant Detroit Board of Education is now attempting

to have this Court compel the state defendants, contrary to their

lawful powers under state law, to reach into the state treasury and

provide approximately 80 million dollars in unappropriated additional

state funds so that there may be 180 days of school in Detroit in the

1972-73 school year. Here, it must be reiterated that the Detroit

School District is levying only 15.5 mills for operating purposes

while the statewide average school district millage levy for operating

purposes is 24 mills. Numerous school districts are levying above

24 mills for operating purposes with a substantial number of school

districts levying above 30 mills. Thus, it would be manifestly

unfair to order the state defendants to divert state school aid

funds away from such school districts, where the electors have

voted in favor of tax rate limitation increases for school operating

purposes, to the Detroit School District, where the electors have

voted against such tax rate limitation increases.

It is the position of the state defendants that this Court

should not order any coercive relief against any party with respect to

providing the additional funds required for 180 days of school

in the Detroit public schools. There is every reason to believe

that the Michigan legislature will provide the means to enable

defendant Detroit Board of Education to have 180 days of student

instruction in the 1972-73 school year. However, in the event

this Court determines it is going to grant such coercive relief

herein, it is significant that in Griffin, supra, cited by

defendant Detroit Board of Education, such coercive relief was

directed against the local governing body with the power to levy

taxes for school operating purposes.

D. The relief sought herein by defendant Detroit

Board of Education constitutes a suit against

the state of Michigan in federal court without

its consent contrary to the Eleventh Amendment

and the controlling precedents of federal

appellate courts.____________________________

In the emergency motion, at paragraphs 3 through 6 of

the prayer for relief, it is crystal clear that, in essence, the

relief sought is to have this Court compel the state defendants,

including the Treasurer of the State of Michigan, to provide

approximately an additional 80 million dollars in state funds

from the state treasury so that the Detroit public schools may be

open for 180 days during the 1972-73 school year. Under the

Eleventh Amendment and the controlling precedents of the federal

appellate courts, this constitutes a forbidden suit against the

state of Michigan in federal court without its consent. Thus, this

Court may not grant the relief sought herein by defendant Detroit

Board of Education.

In the instant cause, the state of Michigan has not been

named as a party defendant. However, the question of whether a suit is

against the state is determined, not by the parties named in the

- 23-

pleadings, but by the essential nature and effect of the

proceedings as appears from the entire record. In re State of

New York, 256 US 490, 497-500 (1921). The state of Michigan, it

must be stressed, has never consented to being sued in this proceeding.

In Smith v Reeves, 178 US 436 (1900) , the Court affirmed a

dismissal of the action, brought against the Treasurer of the State

of California, as the named defendant, on the ground that the

federal courts lacked jurisdiction over such suit in the absence

of consent by the state of California. In doing so, the Court held

the following:

"Is this suit to be regarded as one against the

State of California? The adjudged cases permit

only one answer to this question. Although the

State, as such, is not made a party defendant,

the suit is against one of its officers as Treasurer;

the relief sought is a judgment against TKat officer

in his official capacity; and that judgment would

compel him to pay out of the public funds in the

treasury of the State a certain sum of money.

Such a judgment would have the same effect as if

it were rendered directly against the State for

the amount specified in the complaint. . . . "

pp 438-439

In Ford Motor Co. v Indiana Department of Treasury, 323

US 459 (1945) , a unanimous Court, in dismissing the suit for lack

of jurisdiction in the absence of consent to the suit by the State

of Indiana, held as follows:

"We are of the opinion that petitioner's suit in

the instant case against the department and the

individuals as the board.constitutes an action

against the State of Indiana. A state statute

prescribed the procedure for obtaining refund of

taxes illegally exacted, providing that a taxpayer

first file a timely application for a refund with

the state department of treasury. [Footnote omitted]

Upon denial of such claim, the taxpayer is authorized

to recover the illegal exaction in an action against

the 'department.' Judgment obtained in such action

is to be satisfied by payment 'out of any funds in

the state treasury.' [Footnote omitted] This section

clearly provides for an action against the state, as

opposed to one against the collecting official

individually. No state court decision has been

-26

called to our attention which would indicate that

a different interpretation of this statute has been

adopted by state courts.

"Petitioner's suit in the federal District Court

is based on § 64-2614 (a) of the Indiana statutes

and therefore constitutes an action against the

state, not against the collecting official as an

individual. Petitioner brought its action in

strict accord with § 64-2614 (a). The action is

against the state's department of treasury. The

complaint carefully details compliance with the

provisions of §64-2614 (a) which require a timely

application for refund to the department as a

prerequisite to a court action authorized in the

section. It is true the petitioner in the present

proceeding joined the Governor, Treasurer and

Auditor of the state as defendants, who 'together

constitute the Board of Department of Treasury of

the State of Indiana.' But, they were joined as

the collective representatives of the state, not

as individuals against whom a personal judgment

is sought. The petitioner did not assert any claim

to a personal judgment against these individuals for

the contested tax payments. The petitioner's claim

is for a 'refund,' not for the imposition of personal

liability on individual defendants for sums illegally

exacted. We have previously held that the nature of

a suit as one against the state is to be determined

by the essential nature and effect of the proceeding.

Ex parte Ayers, 12 3 U.S. 443, 490-99;E*.parte New York,

256 U.S. 490, 500; Worcester County Trust Co. v. Riley,

302 U.S. 292, 296-98. And when the action is in

essence one for recovery of money from the state,

the state is the real, substantial party in interest

and is entitled to invoke its sovereign immunity

from suit even though individual officials are nominal

defendants. Smith v. Reeves, supra; Great Northern

Insurance Co. v Read, supra. We are of the opinion,

therefore, that the present proceeding was brought in

reliance on § 64-2614 (a) and is a suit against the

state." p 463-464

Finally, in Copper S S Co v State of Michigan, 194 F2d 465, 466

(CA 6, 1952), a unanimous Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the

dismissal of an action for money damages, on the ground of lack of

jurisdiction, for the reason that the state of Michigan had not

consented to such suit being brought against it in the federal courts.

This decision, together with the two United States Supreme Court

precedents cited above, compel the conclusion that where the state

is the real party against whom relief is sought, particularly where

- 27-

the judgment or decree will operate to compel the payment of state

funds from the state treasury, the action is a forbidden suit

against the state regardless of who are the named parties.

In summary, the relief sought herein is to compel the

state officer defendants to provide approximately an additional

80 million dollars in state funds for continued operation of the Detroit

public schools beyond mid-March, 1973. Thus, under the controlling

precedents, this Court lacks jurisdiction to grant such relief for

the reason that the state of Michigan has never consented to this

suit in federal court.

E. The Defendant Detroit Board of Education is

not entitled to the relief sought herein.

It must be emphasized at the outset of this section of

the brief that the defendant Detroit Board of Education is manifestly

premature in seeking relief from this Court at this time. By its

own admission, sufficient funds are available to operate the schools

through mid-March. Thus the only present emergency is a self

generated one by the defendant Detroit Board of Education in

wanting to close the schoolhouse doors when funds are available,

through the actions of the state defendants, to keep them open, at

least until the middle of March of 1973, with an express legislative

commitment to give top priority to this financial problem in the next

legislative session commencing in early January, 1973.

The moving party, defendant Detroit Board of Education,

has no standing to seek relief under the Fourteenth Amendment for

the reason that, under settled law, it has no rights which it may

invoke under the Equal Protection Clause against its creator, the

state legislature. Williams v Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

289 US 36 (1933).

- 26-

Any claim by defendant Detroit Board of Education that

it is seeking this relief on behalf of its students is patently

inappropriate in light of the expressed intention of such school

board to close the schools on December 21, 1972, when sufficient

funds are available to keep them open through at least mid-March,

1973.

It should be stressed that the Equal Protection Clause

does not require that school districts be financed on the basis of

the relative educational needs of the students attending therein.

Twice the United States Supreme Court has affirmed the decisions

of three-judge federal district courts holding that educational

finance need not be based on the varying educational needs of

students attending in the various school districts of the state.

Mclnnis v Shapiro, 293 F Supp 327 (ND 111 1968), aff'd sub nom.

Mclnnis v Ogilvie, 394 US 322 (1969). Burruss v Wilkerson, 310 F

Supp 572 (WD Va 1969), aff'd 397 US 44 (1970).

The wealth discrimination cases relied upon by the defendant

Detroit Board of Education (Van Dusartz v Hatfield, 334 F Supp 870l

(D Minn, 1971) and Rodrigues v San Antonio Independent School District,

337 F Supp 280 (WD Tex, 1971), appeal docketed 40 USLW 3513 (US April

25, 1972) No. 71-1332) are premised upon a holding that a school

district's per pupil expenditures may not be a function of wealth,

i.e., the property tax base or state equalized valuation of taxable

property per pupil. These precedents are sound. However, they are

inapplicable herein for the reason that the state equalized valuation

per pupil of the Detroit school district is slightly above the state

wide average for Michigan's school districts. Moreover, the Detroit

school district's millage levy is almost 10 mills below the statewide

average for Michigan school districts. If the Detroit School District

- 29-

were levying an additional 10 mills for operating purposes, such

levy would guarantee approximately 60 million dollars in additional

revenue and the remaining financial problems would not have given

rise to any emergency motion before this Court. Detroit's voters,

like every other Michigan school district, were by statute afforded

the opportunity to approve tax rate limitation increases for school

operating purposes without any discrimination, racial or otherwise,

to provide sufficient funds for 180 days of school in the 1972-73

school year.

Here, it cannot be emphasized too strongly that the instant

cause is a school desegregation case, not an educational finance case.

Defendant Detroit Board of Education should not be permitted to turn

this school desegregation case into an educational finance case.

In terms of Michigan's system of financing public elementary and

secondary education, there is presently pending before the Michigan

Supreme Court a case in which that Court is asked to declare the

present Michigan system of financing such public education uncon-

9

stitutional. Milliken and Kelley, et al v Allison Green, et al,

Supreme Court No. 53,809. That case has been briefed and argued

on June 6, 1972 and is awaiting decision.

Other cases relied upon by defendant Detroit Board of

Education, [Hansen v Hobson, 408 F2d 175 (DC Cir, 1969) and Hall

v St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F Supp 649 (ED La, 1961),

aff'd 368 US 515 (1962)], dealt with racial discrimination and thus

are not applicable herein in terms of this emergency motion to

relieve the financial plight of the Detroit School District. In

Hansen v Hobson, supra, the Court was concerned with intra-district

disparities in the allocation of resources among predominantly white

and black schools. In the St. Helena case, supra, under the Louisiana

= 3 0-

statute in question, some school districts closed their schools,

while other public school districts supported with public funds

kept their public schools open, in an attempt to avoid school

desegregation in the closed public schools.

In the instant cause, there is simply no element of racial

discrimination in the current financial plight of the Detroit

school district. The voters in Detroit, white and black alike,

were afforded the same opportunity as the voters in all other

Michigan school districts to approve tax rate limitation increases

for operating purposes. They just failed to vote "yes" in sufficient

numbers, unlike the voters in countless other Michigan school districts.

Further, the fact that Detroit is a majority black school district,

in terms of student body composition, neither adds to nor detracts

from the financial problems of the Detroit school district. Would

anyone seriously contend that the current financial circumstances

of the Detroit school district would somehow be less serious if

all of its pupils were white.

Additional authorities cited by defendant Detroit Board of

Education at page 10 of its memorandum and not heretofore discussed

in this brief are all generally distinguishable on at least two

major grounds. First, such cases were not school cases involving

public education. Second, in none of such cases did the courts

order coercive mandatory injunctive relief of the type sought herein

by defendant Detroit Board of Education.

To summarize this portion of the brief, defendant Detroit

Board of Education lacks standing to seek the relief prayed for

herein. Further, it is the Detroit Board of Education, not the

state defendants, th&t intends to slam the schoolhouse door shut

- 31-

4

and keep its pupils outside when, through the efforts of the

state defendants, there are sufficient funds available to keep

operating the schools through mid-March, 1973, while the legislature

considers various means for assisting the defendant Detroit Board of

Education in providing 180 days of student instruction for the 1972

73 school year, pursuant to its publicly announced intention to do

so on November 30, 1972 (See Appendix B) at the next legislative

session commencing in early January, 1973. Further, during the

month of December legislative staff personnel will be reviewing

various means for providing legislative relief to the Detroit

public schools.

F. The rationale for the July 7, 1972 injunctive

order of the District Court to provide 180 days

of school, that such relief was necessary to

effectuate a metropolitan plan of desegregation,

has been rendered void by the order of the Court

of Appeals entered herein on July 20, 1972, staying

the implementaiton of any metropolitan remedy

pending appeal._______________________________ -

The District Court's injunctive order of July 7,1972,

provides, in pertinent part, as follows:

" . . . [T]he court finding that a metropolitan

plan of desegregation complying with such criteria

cannot be implemented in the event the city of

Detroit school system is on a school year of 117

days, or 63 days less than the minimum statutory

requirement, while other school districts in the

desegregation area comply with such statutory

requirement; and the court further finding that

such criteria and other provisions of the Ruling

on Desegregation Area and Order for Development

of Plan of Desegregation cannot be complied with in the

event such approximately 1,548 teachers are terminated,

as threatened, as aforesaid; and the court further

finding that the threatened implementation of said

shortened school year and of said reduction in

faculty will adversely affect this court's ability

to implement an effective metropolitan plan of

desegregation; and the court further finding that

in order to preserve the status quo, to enable the

effective implementation of such a planT it is

necessary that preliminary injunctive relief issue

as hereinafter provided, . . ." [Emphasis supplied]

pp 2 and 3.

- 3 2 -

Thus, it is manifest that the preliminary injunctive order is

expressly and directly tied to the effective implementation pf

a plan of metropolitan desegregation during the 1972-73 school year.

However, on July 20, 1972 the Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit entered its stay order providing, inter alia, the

following:

"The motion for stay pending appeal having been

considered, it is further ORDERED that the Ordfer

for Acquisition of Transportation, entered by the

District Court on July 11, 1972, and all orders

of the District Court concerned with pupil and

faculty reassignment within the Metropolitan~~Area

beyond the geographical jurisdiction of the

Detroit Board of Education,and all other proceedings

in the District Court other than planning proceedings,

be stayed pending the hearing of this appeal on its

merits and the disposition of the appeal by this

court, or until further order of this court. . . . "

[Emphasis supplied] p 2

It is patently obvious that the rationale for the 180

school day injunctive order is the finding that such order was

necessary to enable the court to effectively implement a metro

politan plan of desegregation. The July 20, 1972 order of the

Court of Appeals has stayed the implementation of any metroplitan

desegregation plan pending appeal on the merits. Consequently,

the rationale underlying the District Court's preliminary injunctive

order has been removed. Therefore, there is no sound basis remaining

for enforcement of the preliminary injunctive order of July 7, 1972.

However, there is e/ery sound basis for permitting the Michigan legis

lature sufficient time to consider and evaluate various proposals

for assisting the defendant Detroit Board of Education in providing

180 days of student instruction in this school year as it has

expressly and publicly stated it intends to do.

- 3 3 -

Conclusion

It is undisputed that the defendant Detroit Board of

Education has been operating at a deficit for the last four

fiscal school years including the current fiscal school year.

See the affidavit of Robert McKerr. It persisted, however, in

paying salaries to its teachers that equal the average salaries

paid to teachers by the seven highest salary school districts in

the counties of Wayne, Macomb and Oakland, even though, at the

same time, it has been unable to lead its electors in voting the

average millage of 24 mills to pay for such salaries. Thus it

has been living beyond its means and the present financial plight

is of its own making.

This is not to say, however, that all efforts should not

be made by the state defendants and, indeed, all parties to this

litigation to persuade the Michigan legislature to provide, by law,

the means so that the defendant Detroit Board of Education can

furnish 180 days of student instruction to its pupils as required

by state law. The state defendants have demonstrated that they

are making every effort, within their lawful authority, to assist

the defendant Detroit Board of Education to provide their pupils

with the education they need and Michigan law requires. They have

every reason to believe that, as in the recent past, the Michigan

legislature will respond favorably to the problem but it must be

stressed that the nature of the means rests in the sound discretion

of the legislature.

It is abundantly clear that there is no real present

emergency in the Detroit school district that would require action

by this Court. It is unnecessary for this Court to order the state

defendants to use the authority they have under state law to assist

the Detroit school district since they already are doing so to the

- 3 4 -

extent of their powers under Michigan law. Diversion of state

funds, including state aid, to the Detroit school district, is not

only unwarranted but not in accordance with law. Defendant Detroit

Board of Education has not made out its case for such extraordinary

relief.

The Michigan legislature is aware of the financial plight

of the Detroit school district and there is every reason to believe

that it will, given sufficient time to study and react to the

problem, provide the means determined by it so that the pupils of

Detroit will receive 180 days of instruction as required by Michigan

law. The Joint Legislative Statement of November 30, 1972,

(Appendix B) is proof positive that this is so.

The foregoing material was prepared prior to the action of

the defendant Detroit Board of Education, on December 5, 1972,

rescinding its decision to close schools on December 19, 1972 for

a period of 8 weeks. The defendant Detroit Board of Education is

to be commended for taking this action on the strength of the Joint

Legislative Statement of November 30, 1972. Thus, the instant

emergency motion is both clearly premature and unfounded. Now is

the time for all parties to cooperate in the democratic legislative

process to resolve this problem rather than to litigate in the federal

judicial process.

Relief

WHEREFORE, state defendants respectfully request this

Honorable Court to deny and dismiss the emergency motion of the

defendant Detroit Board of Education or, alternatively, to dismiss

said motion without prejudice to renewing same at a later date based

upon a showing of changed factual circumstances.

- 3 5 -

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK J. KELLEY

Attorney General

Eugene Krasicky

Assistant Attorney General

Gerald F. Young*

George L. McCargar

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for Defendants Governor,

Attorney General, State Treasurer,

State Board of Education and

Superintendent of Public Instruction

Business Address:

720 Law Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Dated: December 6, 1972

W- * •*

D . C h a r l e s M a r s t o n

W i l l i a m M a z e y

T h e o d o r e S a c h s

R o b e r t L . O 'C o n n e l l

J e a n n e N u n n

B e r n a r d M. F r e i d

M e l v y n J . K a t e s

A . D o n a l d K a d u s h i n

Ro l l a n d R. O ' H a r e

Ro n a l d r . H e l v e s t o n

Ro b e r t R. C u m m i n s

B a r r y P. W a l d m a n

W . K e n n e t h W r i g h t

Ro b e r t G . H o d g e s

J a m e s B . V e u C a s o v i c

R o t h e , M a r s t o n , M a z e y , S a c h s , O ’ C o n n e l l , N u n ^ $ £fc!EiD, P. C.

A t t o r n e y s a n d C o u n s e l o r s a t L a w / ' V

A J>C1 0 0 0 F A R M E R

D E T R O IT . M I C H I G A N 4 8 2 2 6

( 3 1 3 ) 6 6 5 - 3 4 6 4

N i c h o l a s J . r o t h e .

O F C O U N S E L

.4

° $ ■ > ,oV'

P O N T IA C O F F IC E

November 22,

URGENT

V1972

A'

44

O

* X 3 0 2 P o n t i a c St a t e B a n k B l d g .

/ P o n t i a c . M i c h i g a n

FEDERAL 4 - 0 5 8 2

\/

S A G IN A W O F F IC E

2 1 0 B e a r i n g e r B u i l d i n g

S a g i n a w . M i c h i g a n

P L e a s a n t 4 - 3 1 1 0

Detroit Board of Education

5057 Woodward

Detroit, Michigan 48202

CERTIFIED MAIL,

RETURN RECEIPT

REQUESTED

Attention: James A. Hathaway, President

Gentlemen:

As attorneys for the Detroit Federation of Teachers, and on

its behalf, we write to advise you formally that we will regard

any mid-year shutdown of the schools other than as provided in the

parties' collective bargaining contract, to be:

(1) A violation by you and by the State defendants in -

Bradley v. Milliken of Judge Roth's 180-day school year injunction;

(2) A violation by you and by the State defendants of ap

plicable state law to the same effect;

(3) An 'unfair labor practice by you;

(4)

contract;

A violation by you of the parties' collective bargaining

and

(5) A violation by you of individual teacher contracts.

With respect to the latter

applicable law which holds

two items, we call to your attention

that your contractual obligations

APPENDIX A

D e t r o i t B o a r d o f E d u c a t i o n — p a g e 2

to your employees may not be avoided by suspending their services,

regardless of your motivating financial circumstances. Accord

ingly, whether or not the schools remain open, in the event any

regular payroll is not met or appears unlikely to be met we will

seek a- money judgment against you for breach of contract and there

after, as necessary, invoke applicable statutory law to spread

the judgment on the tax rolls for collection.

We add that at is the primary concern of the Federation that Detroit

school children not be deprived of equal and adequate educational

opportunities, and so the first focus of our attention will be to

endeavor to keep the schools open. Failing that, we will unter-

take all appropriate action to enforce teachers' salary rights

under their contracts.

We therefore request that you rescind all resolutions respecting

shutdown for any extended period following December 21, 1972, and

cease and desist from any other comparable action.

Yours very truly,

Theodore Sachs

TS: ek

cc: George Roumell, Esq.

Aubrey McCutcheon, Esq.

Hon. William Milliken, Governor

Hon. Frank Kelley, Attorney General

DFT, Attn: Mrs. Riordan

PRESS RELEASE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

November 30, 1972

House and Senate leaders, meeting today, pledged top priority considera

tion of efforts to solve the short-range and long-range financial problems of

the public schools of Michigan. .

The following statement was issued jointly by House Speaker William A. Ryan,

House Minority Leader Clifford H. Smart, House Appropriations Committee Chairman

William R. Copeland, Senate Republican Leader Robert VanderLaan, Senate Democrati

Leader George S. Fitzgerald, Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Charles 0.

Zollar and Senate Democratic Floor Leader Coleman A. Young.

"Members of the Michigan Legislature are aware of and concerned about the

financial difficulty facing the-Detroit Public School Board in attempting to

fulfill its legal obligation to provide 180 days of education for nearly 1/7

of the state's school children. In fact, there are strong feelings among