Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Heyward v. Public Housing Administration Brief for Appellants, 1953. 815c1f24-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb83f99d-a5c5-4166-b334-6f3cffdeb5a8/heyward-v-public-housing-administration-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

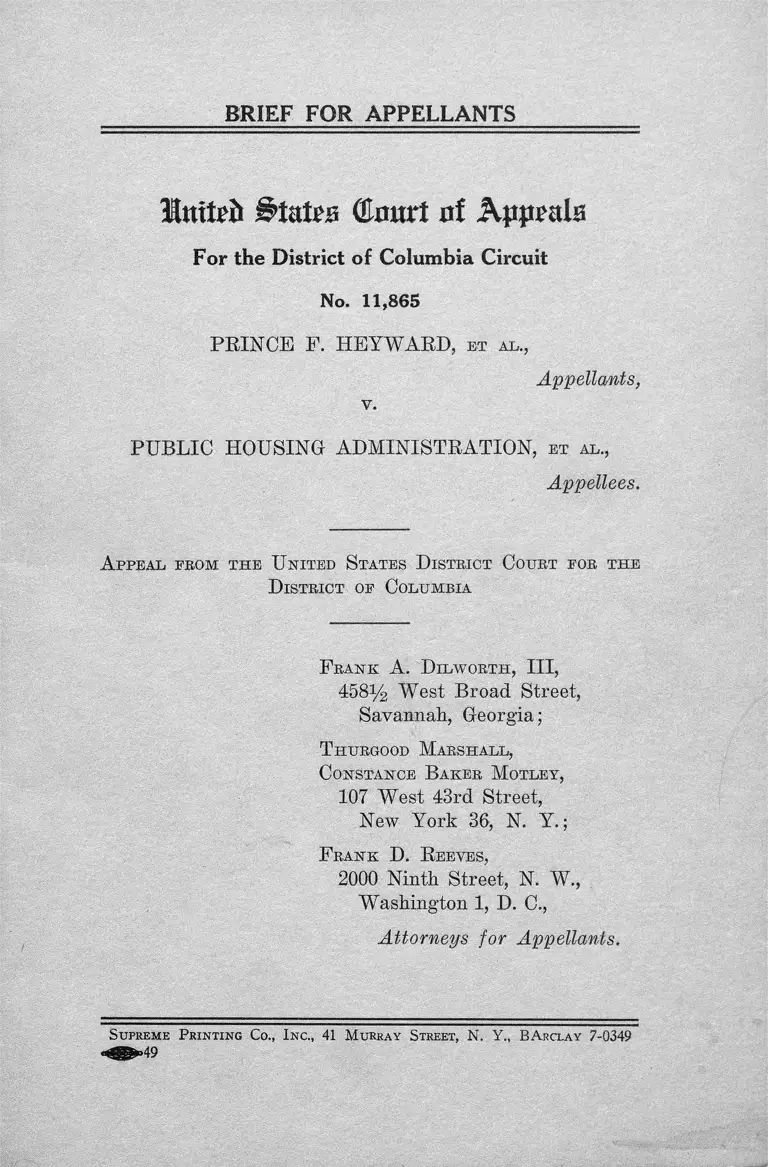

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Imtefc States (Enurt ai Appeals

For the District of Columbia Circuit

No. 11,865

PRINCE F. HEYWARD, e t a l .

Appellants,

v.

PUBLIC HOUSING ADMINISTRATION, e t a l .,

Appellees.

A p p e a l f r o m t h e U n it e d S t a t e s D i s t r i c t C o u r t e o r t h e

D is t r i c t o e C o l u m b ia

F r a n k A. D i l w o r t h , III,

458% W est Broad Street,

Savannah, Georgia;

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

C o n s t a n c e B a k e r M o t l e y ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, N. Y.;

F r a n k D. R e e v e s ,

2000 Ninth Street, N. W.,

Washington 1, D. C.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc ., 41 M urray S treet, N . Y., B A rclay 7-0349

Question Presented

Whether it constitutes a violation of rights secured by

the Constitution, Laws and Public Policy of the United

States for the Federal Government to require or sanction

racial segregation in low rent public housing projects,

provided separate but equal facilities for eligible white

and non-white families are furnished.

I N D E X

Jurisdictional Statem ent............................... 1

Statement of C ase ........................................................................ 1

Statutes Involved......................................................................... 3

Statement of Points ................................................................... 4

Summary of Argum ent................................................................ 6

Argument ..................................................................................... 7

I. The Federal Program Involved in this A ction .......... 7

A. The Basic Statute ................................................ • 7

B. The Role of Appellee PH A as Determined by

the Basic S ta tu te ......................................................... 8

C. The Role of Appellee PHA as Evidenced by

Basic Rules and Regulations and Administra

tive Provisions Adopted by the Appellee Com

missioner of P H A ...................................................... 11

1. The Role of PHA as Defined by Part Two

of the Annual Contributions C ontract........ 11

2. Special Role of PHA with Respect to Local

Racial Policies Described in Agency Manual

of Policy and Procedure, Low Rent Housing

Manual and Special Policy Directives.......... 13

II. The Establishment of Fred Wessels Homes as a Project

Limited to Occupancy by White Low Income Families

Violates Rights Secured to Appellants by the Laws,

Constitution and Public Policy of the United States .. 18

A. The Right Conferred on Appellants by the Basic

State ............................................................................ 18

B. Protection Afforded by the Federal Civil Rights

Statutes........................................................................ 19

PAGE

11

C. Protection Afforded by the Constitution of the

United S ta te s ......................... 21

1. The Fourteenth Am endment...................... 22

a. The Separate but Equal D octrine........ 25

b. Police Power and Property Values . . . . 31

2. The Fifth Amendment.................................. 32

D. Protection Afforded by Consideration of Public

Policy ...................................................................... 35

III. Congress Intended that there be no Segregation.......... 36

A. Legislative History—Senate ................................ 36

B. Legislative History—H o u se .................................. 39

IV. Appellants have Standing to S u e .................................... 40

A. Relief Sought..................... 40

B. This is not a Taxpayer’s A ction............................ 41

C. The Justiciable Is su e .............................................. 43

Conclusion..................................................................................... 46

TA B L E O F CASES

Allen v. Oklahoma City, 175 Okla. 421, 52 Pac. 1054 (1935) .................. 25

Banks, et al. v. San Francisco Housing Authority, No. 420534, Oct. 1,

1952, Superior Court in and for San Francisco County .................... 26, 30

Barrows v. Jackson, United States Supreme Court, Oct. Term, 1952,

No. 517 decided June 15, 1953, — U. S. —, 97 L. ed. (advance

p. 961) ........................................................................................22, 25, 35, 45, 46

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 62 L. ed. 149 (1917) .......20, 22, 23, 24, 27,

28, 31, 35, 46

City o f Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (1951), cert. den. 341 U. S.

940, 95 L. ed. 1367 (1951) .......................................................................... 24

City o f Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704, 74 L. ed. 1128 (1930) .......... 24

Crabb v. Welden Bros., 65 F. Supp. 369 (S. D. Iowa, C. D.) (1946) . . . 19

Crumpton v. Zabriskie, 101 U. S. 601, 25 L. ed. 1070 (1880) ................ 44

E x parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 25 L. ed. 676 (1880) ......................... 23

Favors v. Randall, 40 F. Supp. 743 (E. D. Penn.) (1941) ..................... 27, 28

Frothingham v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 477, 67 L. ed. 1078 (1923) .................. 41, 42

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668, 71 L. ed. 830 (1927) ........................... 24

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 87 L. ed. 1774 (1943) .......... .32, 33

H urd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24, 92 L. ed. 1187 (1948) . . . .20, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 46

Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Bd. o f Education, 333 U. S. 203, 92 L. ed.

649 (1948) ......................................................................................................... 44

Joint AntFFascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 95

L. ed. 817 (1951) .......................................................................................

PAGE

45

Ill

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 89 L. ed. 194 (1944) .......... 32, 33

Massachusetts v. Mellon, 262 U. S. 447, 67 L. ed. 1078 (1923) .............. 41, 42

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. S37 (1896) ............................................... 26, 27, 28

Seawell et al. v. MacW ithey, 2 N. J. Super. 2S5, 63 Atl. 2d 542 (1949)

rev’d on other grds. 2 N. J. 563, 67 Atl. 2d 309 (1949) ................ 26

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 92 L. ed. 1161 (1948)..........20, 22, 24, 28, 32,

33, 34, 35, 45, 46

Strauder v. W est Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 25 L. ed. 664 (1880) .......... 22

Vann, et al. v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, (U. S. D. C.

N. D. Ohio) Civil Action No. 6989, July 24, 1953 ..........................21, 25, 29

Wong Yim v. United States, 118 F. 2d 667 (1949), cert. den. 313 U. S.

589, 85 L. ed. 1544 (1941) ....................................................................... 32

Woodbridge, et al. v. The Housing Authority o f Evansville, Indiana,

et al. (U . S. B. C. Ind.) Civil Action No. 618, July 6, 1953. .19,20,25, 29,36

Young v. Kellex Corf., 82 F. Supp. 953 (E . D. Tenn. N. D.) (1948) .. 19

PAGE

ST A T U TE S

Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 S#at. 888, as amended by Aqt of

July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, U. S. C.,

Sections 1401 ............................................................................................... 1,2,7, 8

1402(11) ....................................................................................... 7,19

1404(a) 11

1409 ............................................................................................... 19

1410 ................................................. 19

1410(a) ......................................................................................... 8,10

1410(c) ......................................................................................... 9

1410(f) ......................................................................................... 10

1410(g) ........................................................................................2 ,3 ,5 ,6 ,18

1410(h) ....................................................................................... 8,10

1411 ............................................................................................... 19

1413(a) ......................................................................................... 10

1415(5) ......................................................................................... 9

1415(7) (a ) ....................................................................................8,9,22,23

1415(7) (b) 8,9

1415(8)(a ) 9

1415(8)(b) 9

1415(8) (c) 19

1421(a)(1) 10

1433 ............................................................................................... 10

Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 1, 14 Stat. 27, Title 8, U. S. C„

Sec. 42 ..................................................................... 1, 4, 5, 6,19,20, 27, 33, 34, 35,46

Act of June 25, 1948, c. 646, Sec. 1, 62 Stat. 930, Title 28, U. S. C.,

Section 1331 ................................................................................................. 1

Act of June 25, 1948, c. 646, Sec. 1, 62 Stat. 929, Title 28, U. S. C„

Section 1291 ............................................................................................... 1

C O N ST IT U T IO N

United States Constitution:

F ifth Amendment ................................................................................. 1, 5, 6, 32

Fourteenth Amendment ......................................................................... 22

OTHER AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Congressional Record, Vol. 95, P art 4, 81st Cong., 1st Sess.

pages 4791 ..................................................

4851 ..............................................

4852 ............................................................

4853 ............................................................

4855 ...................................................................

4856 ......................................................

4857 ................................................. ............................

4858 ........ .....................................................................

Congressional Record, Vol. 95, P a rt 7, 81st Cong., 1st Sess.

pages 8554 ..................................................................

8555 .............................................................

8656 ..............................................................

8657 ..............................................................

Terms and Conditions, Constituting P art Two of an Annual Con

tributions Contract between Local Authority and Public Plousing

Administration, Form PHA-1996, June 1950, Secs. 102(B) ..........

102(C) ..........

102(D) ..........

102(E) ..........

102(F) ..........

103 ..................

104 ..................

113 ..................

115 ..................

118 ..................

122 ..................

126

127 ..................

128 ..................

130 ..................

131 ..................

132 ..................

pp. 13-21 ........

304 ..................

305 ..................

306 ..................

308(D) ..........

308^ ..............

36

37

37

37, 38

37,38

37

37

37

39

39

40

40

12

12

12

12

12

12

12

17

12

12

12

12

12

12

13

13

13

13

13

13

13

13

13

309(C) (D ) .. 13

325 .................. 13

H H F A P H A Manual of Policy and Procedure, Secs. 3911:10 .......... 16

3112:18 .......... 16

3812:1 .......... 16

3810:1 17

3110:1 17

6110:1 17

Low Rent Bulletin 12 (June 1950) ..............*.......................................... 16

Form P H A -1922 (2 /1 5 /5 0 ) .............. ..................................................... 17

Form PHA-1954 (Rev. July 1950) 101 .................................................. 17

103 .................................................. 17

201 .................................................. 17

203 .................................................. 17

207 .................................................. 17

224 .......................................... 17

H H FA -O A No. 470, January 17, 1953 .................................................... 14-15

H H F A P H A Low Rent Housing Manual, Secs. 102.1 ...................... 14

207.1 ...................... 16

Intteit BUtm ( ta r t nt Appeals

For the District of Columbia Circuit

No. 11,865

-------------------o-------------------

P r i n c e F . H e y w a r d , E r s a l in e S m a l l , W i l l i a m M i t c h e l l ,

W i l l i a m G o l d e n , M i k e M a u s t i p h e r , AYi l l i s H o l m e s ,

A l o n z o S t e r l i n g , M a r t h a S i n g l e t o n , I r e n e C h i s h o l m ,

J o h n F u l l e r , B e n j a m i n E . S i m m o n s , J a m e s Y o u n g ,

O l a B l a k e ,

Appellants,

v.

P u b l i c H o u s in g A d m i n i s t r a t i o n , body corporate; J o h n

T . E g a n , Commissioner, Public Housing Administra

tion,

Appellees.

-------------------o-------------------

A p p e a l p r o m t h e U n it e d S t a t e s D is t r ic t C o u r t f o r t h e

D i s t r ic t o f C o l u m b ia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

1

Jurisd ictional S tatem ent

Appellants filed their Complaint in the United States

District Court for the District of Columbia, the court below,

on September 8, 1952, pursuant to Act of June 25, 1948, c.

646, Sec. 1, 62 Stat. 930, Title 28, United States Code,

Sec. 1331, this being a suit which arises under the Con

stitution and Laws of the United States, that is, the

Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and Act of September 1, 1937, c. 896, 50' Stat. 888, as

amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, 63

Stat. 422, Title 42, United States Code, Secs. 1401-1433,

and Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 1, 14 Stat. 27

(B. S. Sec. 1978), Title 8, United States Code, Sec. 42,

wherein the matter in controversy as to each of the Appel

lants exceeds three thousand dollars exclusive of interest

and costs (Joint Appendix 6).

The court below, on April 28, 1953, after hearing

Appellees’ Motion for Summary Judgment, filed December

22, 1952, entered an Order granting Appellees ’ Motion for

Summary Judgment and dismissing the Complaint herein

on the ground that Plaintiffs, Appellants here, failed to

state a claim upon which relief can be granted (Joint

Appendix 15, 1).

From this Order, Appellants duly filed a Notice of

Appeal on May 25, 1953 and prosecuted the appeal herein

pursuant to Act of June 25, 1948, c. 646, Sec. 1, 62 Stat.

929, Title 28, United States Code, Sec. 1291.

Statem ent of the Case

In their Complaint, Appellants allege that:

They are adult Negro citizens of the United States and

of the State of Georgia, residing in the City of Savannah

on a site commonly known as the “ Old Fort” area (Joint

Appendix 8).

2

Each of them will be displaced from such site by reason

of the fact that the site has been condemned by or on

behalf of the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, a

public agency, for the purpose of constructing thereon a

low rent housing project pursuant to the provisions of Act

of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act of

July 15, 1949, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, U. S. C., Secs. 1401-

1433 (Joint Appendix 8).

Each of them meets the requirements established by

law for consideration and admission to the said low rent

public housing project (Joint Appendix 8).

Each of them is entitled by law, Act of Sept. 1, 1937,

c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949,

c. 338, Title III, Sec. 302(a) (g), 63 Stat. 423, Title 42,

IT. S. C. Sec. 1410(g), to a preference for consideration and:

admission to any public low rent housing project built in

the City of Savannah, Georgia, and initiated after January

1, 1947, by reason of the fact that his or her family will be

displaced from a site on which a low rent public housing

project will be built (Joint Appendix 8).

Appellees, the Public Housing Administration and

John T. Egan, Commissioner of the Public Housing

Administration, administer the Act of Congress pursuant

to which the low-rent housing project in controversy will

be constructed and operated, Act of Sept, 1, 1937, c. 896, 50

Stat. 888, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title

III, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, United States Code, Secs. 1401-

1433 (Joint Appendix 9).

In accordance with the provisions of said Act, the Appel

lee, Public Housing Administration, has entered into a

contract with the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia,

pursuant to which contract said Appellee has agreed to

give federal financial assistance and other federal assistance

to the Housing Authority of Savannah, Georgia, for the

construction, operation and maintenance of said housing

project (Joint Appendix 9-10).

3

The housing project in controversy will be known as the

Fred Wessels Homes, is also designated as G-A-2-4, and

will be limited to occupancy by eligible low income white

families (Joint Appendix 10).

The Appellants, although meeting all the qualifications

established by law for admission to the project and although

having a preference for admission conferred by law, will

be denied consideration for admission and admission to the

said project solely because they are not white families

(Joint Appendix 8, 11).

In response to Appellants’ Complaint, the Appellees,

Defendants below, filed a Motion for Summary Judgment

which was heard on April 21, 1953 (Joint Appendix 15).

On May 8, 1953 the court below rendered its opinion

( Joint Appendix 2).

On April 28, 1953, the court below, entered an Order

granting the Motion for Summary Judgment and dismiss

ing the Complaint herein on the ground that the Complaint

fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted

(Joint Appendix 1).

From this Order Appellants appeal.

Statutes Involved

Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended

by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, Sec. 302(a) (g), 63

Stat. 423; Title 42, U. S. C. Sec. 1410(g):

“ Veterans’ preference: Every contract made pur

suant to this Act (§1401 et seq. of this title) for

annual contributions for any low-rent housing proj

ect shall require that the public housing agency, as

among low-income families which are eligible appli

cants for occupancy in dwellings of given sizes and

at specified rents, shall extend the following prefer

ences in the selection of tenants:

4

“ First, to families which are to be displaced by

any low-rent housing project or by any public slum-

clearance or redevelopment project initiated after

January 1, 1947, or which were so displaced within

three years prior to making application to such

public housing agency for admission to any low-rent

housing; and as among such families, first preference

shall be given to families of disabled veterans whose

disability has been determined by the Veterans’

Administration to be service-connected, and the

second preference shall be given to families of de

ceased veterans and servicemen whose death has

been determined by the Veterans’ Administration to

be service-connected, and third preference shall be

given to families of other veterans and servicemen;

“ Second, to families of other veterans and ser

vicemen and as among such families first preference

shall be given to families of disabled veterans whose

disability has been determined by the Veterans’ Ad

ministration to be service-connected, and second

preference shall be given to families of deceased

veterans and servicemen whose death has been de

termined by the Veterans’ Administration to be

service-connected. ’ ’

Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 1, 14 Stat. 27, Title 8,

U. S. C., Sec. 42:

“ Property rights of citizens. All citizens of the

United States shall have the same right, in every

State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens

and thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold,

and convey real personal property. (R. S. § 1978.) ”

Statement of Points

1. The court below erred in dismissing the Complaint

on the ground that it fails to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted.

2. The court below erred in ruling that “ it is entirely

proper and does not constitute a violation of Constitutional

rights for the Federal government to require people of

white and colored races to use separate facilities, provided

equal facilities are furnished to each.”

3. The court below erred in ruling that ‘ ‘ The Congress

has conferred discretionary authority on the administra

tive agency to determine for what projects Federal funds

shall be used. There are very few limitations in the statute

on the power of the administrator, and there is no limitation

as to racial segregation.”

4. The court below erred in granting Appellees ’ Motion

for Summary Judgment on the ground that the Complaint

fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

5. The court below erred in refusing to rule that Appel

lees in giving Federal financial assistance and other Fed

eral assistance, provided for by Act of Congress, for the

construction, maintenance, and operation of a public low-

rent housing project from which the Appellants will be

excluded and denied admission, solely because of their race

and color, are violating rights secured to Appellants by

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Fed

eral Constitution, and by Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 42,

14 Stat. 27, Title 8 U. S. C. Sec. 42 and Act of September

1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act of July

15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, Sec. 302(a) (g), 63 Stat. 423,

Title 42, U. S. C. Sec. 1410(g), and are violating the public

policy of the United States.

6. The court below erred in refusing to rule that Ap

pellants, and all other Negroes similarly situated, cannot be

denied consideration for admission and/or admission to

the Fred Wessels Homes or any other federally-aided hous

ing project solely because of their race and color.

6

7. The court below erred in refusing to rule that the

preference for admission to the Fred Wessels Homes or

any other federally-aided low rent housing project initiated

after January 1,1947 in the City of Savannah, Georgia, con

ferred on Appellants, and all other Negroes similarly situ

ated, by Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c, 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended

by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338 Title III, 63 Stat. 423 Title

42, U. S. C. Sec. 1410(g) may not be qualified or limited

by race or color.

Sum m ary o£ A rgum ent

The Federal Government may not require or sanction,

racial segregation in low-rent public housing, provided

separate but equal facilities for white and non-white fami

lies are furnished, since such a requirement or sanction

violates property rights secured to Appellants by the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution and by Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 1, 14

Stat. 27, Title 8 U. S. C. Sec. 42 and denies to Appellants

rights conferred by Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888,

as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, Sec.

302(a) (g), 63 Stat. 423, Title 42 IT. S. C. Sec. 1410(g) and

violates the public policy of the United States.

Appellants have standing to sue and may maintain this

action which they bring against Appellees as persons ag-

rieved by Appellees’ unlawful administration of a federal

statute enacted for the specific benefit of a class, low income

families, of which Appellants are members, and as persons

whose constitutionally and legislatively protected property

rights have been violated by the racial segregation policy

of which Appellants’ complain, and as persons and mem

bers of a class, displaced families, whose right to a prefer

ence for admission conferred by statute has been denied

by Appellees.

7

A RGUM ENT

I. The Federal Program Involved In This Action.

The federal program involved in this action is low-rent

public housing.

A. The Basic Statute

The basic statute providing for this program is com

monly referred to as The Housing Act of 1937, as amended

by Title III of the Housing Act of 1949.1

The Appellee Public Housing Administration is au

thorized by the basic statute to enter into contracts for

federal financial assistance only “ with a state or a state

agency where such state or state agency makes application

for such assistance for an eligible project which, under the

applicable laws of the state, is to he developed and admin

istered by such state or state agency. ’ ’2 The basic statute

declares that it is “ the policy of the United States to

promote the general welfare of the Nation by employing

its funds and credit * * * to assist the several states and

their political subdivisions * # * to remedy the unsafe and

unsanitary housing conditions and the acute shortage of

decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low

income, in urban and rural non-farm areas, that are

injurious to the health, safety and morals of the citizens

1 Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act

of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, U. S. C„

§ 1401-1433. The Housing Act of 1937 provided for the first exten

sive program of federal financial assistance for low-rent public hous

ing. Prior to 1937, federal financial assistance for low-rent public

housing had been made available under the provisions of the National

Industrial Recovery Act. Title 40, United States Code, §401, 48

Stat. 200.

2 Ibid, Title 42, U. S. C. § 1402 (11), 63 Stat. 429.

8

of the Nation.” 8 The basic act also provides that the

determination that there is a need for snch housing for low

income families in a particular locality must be made by

the political subdivision of the state which seeks the federal

assistance, by providing that the local governing body must,

by resolution, approve the application of the public housing-

agency for the financial assistance sought from the federal

government and must enter into an agreement with the

public housing agency providing for cooperation on its

part with such agency.3 4 In addition, the local governing

body must provide for the exemption from local taxation

of all projects assisted under the basic act,5 and must agree

with the public housing agency that within five years after

the completion of a project it’ shall have eliminated an

equivalent number of slum dwelling units.6

The basic act thus effects federal-state character, making

the housing made available to low income families as a

result of this program distinctly public—the product of

joint federal-state action.

B. The Role Of A ppellee Public Housing

A dm inistration As D eterm ined By The

Basic Statute

Several provisions of the basic statute determine that

the dominant role in this federal-state program shall be

assumed by the federal agency by effecting complete federal

involvement in, with veto power over, every major deter

mination made with respect to the planning, construction,

3 Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act

of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 429, Title 42, U. S. C

§ 1401.

4 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, U. S. C., § 1415(7) (a) (i) (b) (i).

5 Ibid, 63 Stat. 428, Title 42, U. S. C., § 1410(h).

6 Ibid, 50 Stat. 891, as amended by Act of Tuly 15, 1949, c. 338,

63 Stat. 430, Title 42, U. S. C., § 1410(a).

9

operation and maintenance of a project assisted under the

act.

Although the basic statute provides, for example, that

the need for public housing shall be determined by the local

housing authority and approved by the local governing

body, it requires that the locally determined need be ap

proved by PHA.7 PHA is authorized by the basic statute

to require a cooperation agreement between the local public

agency and the local governing body before any contract

for loan or annual contribution is entered into.8 The basic

statute requires that PHA be satisfied “ that a gap of at

least 20 per centum has been left between the upper rental

limits for admission to the proposed low rent housing and

the lowest rents at which private enterprise unaided by

public subsidy is providing * * * housing * * *.” 9 The

basic law further provides that the income limits of tenants

and all revisions thereof be approved by PHA;10 that

periodic written statements be sent PHA concerning

investigations made by a duly authorized official of the

local agency of each family admitted to the project;11 that

PHA approve the cost amounts of the main construction

contracts; 12 that PHA determine the purposes for which

excess receipts of the local agency shall be used;13 that

PHA may defer the requirement of elimination of the

7 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, United States Code, Sec. 1415(7) (a).

8 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, United States Code, Sec. 1415(7) (b).

9 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, United States Code, Sec. 1415(7) (b).

10 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, United States Code, Sec.

1415(8)(a).

11 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1415(8) (b).

12 Ibid, 50 Stat. 896, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338,

63 Stat. 424, Title 42, U. S. C., Section 1415(5).

13 Ibid, 50 Stat. 892, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338,

63 Stat. 426, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1410(c).

10

equivalent number of unsafe or insanitary dwellings situ

ated in the locality, where there is an acute shortage of

decent, safe, or sanitary housing available to families of

low income ;14 that PHA may require that payments under

annual contributions contracts be pledged as security for

any loan obtained by the local agency to assist the develop

ment or acquisition of any project to which the annual

contribution relates;15 that PHA’s contract with the local

agency provide for tax exemption of the project or pay

ments by the local agency in lieu thereof ;16 that PHA may

foreclose on any property or commence any action to

protect or enforce any of its rights and may bid for and

purchase at any other foreclosure or acquire or take posses

sion of any project which it previously owned or in connec

tion with which it made any loan, annual contribution, or

capital grant; and in such case may complete, administer,

pay the principal of and interest on any obligations issued

in connection with such project, dispose of, or otherwise

deal with such projects;17 and that PHA may approve

certain state low rent or veterans projects as low rent

housing projects to be aided under the basic act.18 Finally,

the basic statute provides that PHA, upon the occurrence

of any substantial default by the local agency with respect

to any of the covenants or conditions to which the local

agency is subject, at its option, may take title or possession

of any project as then constituted.181

14 Ibid, 50 Stat. 891, 893, as amended by Act of Tuly 15 1949

c. 338, 63 Stat. 428, 430, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1410(a).

15 Ibid, 50 Stat. 892, as amended by Act of June 21, 1938, c. 554,

52 Stat. 820, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, 63 Stat. 424,

Title 42, U. S. C„ Sec. 1410(f).

16 Ibid, Note 5.

17 Ibid, 50 Stat. 894, Title 42, United States Code, Sec. 1413(a).

18 Ibid, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title VI,

63 Stat. 440, Title 42, U. S. C. Sec. 1433.

1Sa Ibid, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III,

Sec. 307(h j, 63 Stat. 431, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1421(a) (1).

11

PHA lias no rule or regulation or policy directive which

requires open occupancy in any project taken over and

operated by it.

C. The Role Of A ppellee Public Housing

Administration As Evidenced By Basic Rules

And Regulations A nd A dm inistrative P ro

visions Adopted By The A ppellee Commis

sioner of PHA

In order to implement the dictates of the basic statute

with respect to its role, Appellee Commissioner of PHA

has, pursuant to his statutory rule making power, adopted

agency rules and regulations, and administrative pro

visions which bind and determine PHA’s relationship with

the local agency.10 These administrative edicts are con

tained in several basic documents: The Manual of Policy

and Procedure (9/5/51), The Low Rent Housing Manual

(2/2/52), and Part Two of every Annual Contributions Con

tract, copy of the latter being attached to appellees’ Motion

for Summary Judgment in the court below. (Joint Ap

pendix 60).

1. The Role Of PHA As Defined By P a r t Two

Of The Annual Contributions C ontract

Part II of the Annual Contributions Contract is that

part of the basic agreement between the federal agency

and the local authority which contains the terms and con

ditions upon which the two agencies will operate and co

operate in the joint program. The role of PHA as dictated

by various provisions of the basic statute is described

supra. Study of Part II demonstrates even more conclu

sively PHA’s role in planning, development and manage

ment of local program. Under this part of the contract,

PHA approves contracts for services of experts for land 19

19 Ibid, as amended by Act of Aug. 10, 1948, c. 832, 62 Stat. 1284,

Title 42, U. S. C„ Sec. 1404(a).

12

surveys, title information, legal services, land acquisition,

appraisals;20 options accepted by the local authority, the

institution of condemnation proceedings, acquisition of

project site;21 use restrictions on site;22 title vesting of

site in local authority;23 giving of financial assistance to

persons displaced from, site;24 the plans and specification

of the local authority for construction of the project;25 all

construction contracts including bids for same;26 PHA

determines prevailing wages to be paid by local authority

to all architects, technical engineers, draftsmen, and techni

cians employed in the development of the projects ;27 PHA

may waive requirement that only domestic materials be

used in construction;28 PHA prescribes the forms to be

used by contractors and sub-contractors in preparing their

payrolls and issues instructions with respect to same;29

PHA has the right to inspect the construction work 30 and

the completed project when ready for occupancy;31 PHA

approves any further development work;32 PHA approves

20 Form PHA-1996, Part Two, June 1950, pg. 1, Sec. 102(B).

21 Ibid, Sec. 102(C)

22 Ibid, Sec. 102(D)

23 Ibid, Sec. 102(E)

24 Ibid, pg. 2, Sec. 102(F).

25 Ibid, Sec. 103

26 Ibid, Sec. 104

27 Form PHA-1996, Part Two, June, 1950, pg. 7, Sec. 115.

28 Ibid, pg. 8, Sec. 118.

28 Ibid, pg. 8, Sec. 122.

30 Ibid, pg. 9, Sec. 126.

31 Ibid, pg. 10, Sec. 127.

32 Ibid, pg. 10, Sec. 128.

13

development cost;83 PHA approves all financial arrange

ments ;33 34 PHA approves management program,3® budgets,36

income limits and rent schedules;37 standards of dwelling

size;38 insurance coverage;39 supervises and approves or

itself repairs, reconstructs or restores any damaged or de

stroyed project;40 PHA periodically reviews all manage

ment operations and practices.41

These references demonstrate that the role of PHA is

not a passive one—PHA has veto power with respect to

practically every determination made by the local agency,

whose role would appear to be that of agent for the fed

eral agency. These terms and conditions make self-evident

that the predominant role in the planning, construction and

operation of projects is assumed by the federal agency.

2. Special Role Of PH A W ith Respect To Local

Racial Policies Described In A gency M anual

Of Policy And Procedure, Low R ent Housing

Manual And Special Policy Directives

In the agency’s Manual of Policy and Procedure and

Low Rent Housing Manual most of the provisions of Part

Two of the Annual Contributions Contract are reiterated

and embellished with agency directives, but, in addition,

these documents, including Part Two, contain special con

33 Ibid, pg. 11, Secs. 130, 131, 132.

34 Ibid, pg. 13-21.

38 Ibid, pg. 22, Sec. 304.

38 Ibid, pg. 22, Sec. 305.

87 Ibid, pg. 22, Sec. 306.

38 Ibid, pg. 25, Sec. 308(D).

39 Ibid, pg. 25, Sec. 308^.

40 Ibid, pg. 27, Sec. 309(C) (D).

41 Ibid, pg. 33, Sec. 325.

14

siderations and requirements with respect to local racial

policies and determinations, none of which adhere to the

constitutional, legislative or public policy mandate dis

cussed infra that there be no discrimination, including no

racial segregation, with respect to selection of tenants for

the housing accommodations made available as a result of

this federal-state program.

The basic racial policy consideration, commonly referred

to as PHA Racial Equity Formula, provides as follows:

Racial Policy

The following general statement of racial

policy shall be applicable to all low-rent housing

projects developed and operated under the United

States Housing Act of 1937, as amended:

1. Programs for the development of low-rent

housing in order to be eligible for PHA assistance,

must reflect equitable provision for eligible families

of all races determined on the approximate volume

and urgency of their respective needs for such hous

ing.

2. While the selection of tenants and assigning

of dwelling units are primarily matters for local

determination, urgency of need and the preferences

prescribed in the Housing Act of 1949 are the basic

statutory -standards for the selection of tenants.42

In addition to this basic policy statement there is a

recent policy directive which more clearly reveals PHA’s

racial policy. This latest statement of racial policy pro

mulgated by PHA is contained in a release issued January

17, 1953 (HHFA-OA No. 470) and provides, insofar as

material to the low-rent housing* program, as follows:

42 HHFA PHA Low-Rent Housing Manual, Sec. 102.1, Febru

ary 21, 1951.

15

Low-Rent Public Housing

The United States Housing Act of 1937, as

amended, and as perfected by Title III of the Hous

ing Act of 1949, authorizes the Public Housing Ad

ministration to make loans and annual contributions

to local communities to assist them in remedying

unsafe and insanitary housing conditions and in

providing safe, decent and sanitary dwellings for

families of low income. Its primary and principal

objective is the improvement of the housing condi

tions of American families of low income. Many of

the low-rent public housing projects assisted under

the Act, however, are constructed on slum sites. In

such cases * * * such clearance of slum areas occupied

by Negro or other racial minority families could

result in worsening, instead of the desired improve

ment, of the housing conditions of such families,

because of the limited living space generally available

to such families as well as their inability to pay the

rents required for decent, safe, and sanitary housing.

Accordingly, in the course of actual operating ex

perience, general procedures * * * have developed

from the joint efforts of the local and Federal agen

cies to assure that, in the selection of sites for low-

rent public housing projects assisted under the United

States Housing Act of 1937, as amended, the living-

space presently available to Negro and other racial

minority families is not reduced. These general pro

cedures are based upon the following:

A slum or blighted area presently occupied in

whole or in part by a substantial number of Negro or

other racial minority families may be cleared and

redeveloped with low-rent public housing i f :

1. The low-rent public housing is to be available for

occupancy by all racial groups, or

2. The low-rent public housing available for occu

pancy by Negro or other racial minority families

is to be constructed in the area in an amount

substantially equal to the number of dwelling-

units in such area which were occupied by Negro

or other racial minority families prior to its re

development, or

16

3. The low-rent public housing is not to be available

for occupancy by all racial groups or for occu

pancy by Negro or other racial minority families,

and

A. Low-rent public housing available for occu

pancy by Negro or other racial minority families

(in an amount substantially equal to the number

of dwelling units in such area which were occupied

by Negro or other racial minority families prior

to its redevelopment is made available through

the construction of low-rent public housing in

areas elsewhere in the community, which areas

are not generally less desirable than the area to

be redeveloped, and

B. Representative local leadership among

Negro or other racial minority groups in the

community has indicated that there is no sub

stantial objection thereto.

In addition to these major policy statements and direc

tives there are numerous requirements imposed by PH A

on the local agency with regard to race. For example:

the rules and regulations define the organization and func

tion of the Racial Relations Branch of PH A ; 48 set forth

the requirement that local public agencies compile m in ority

employment data; 43 44 define racial relations activities in

in management45 and in construction; 46 require that the

housing provided for all racial groups be of substantially

the same quality, service, facilities and conveniences with

respect to all standards and criteria for planning and

design; 47 48 require a no discrimination provision with respect

to employment in all construction contracts; 48 the same

43HHFA PHA Manual of Policy & Procedure (9/5/51), Sec.

3911:10.

44 Ibid, Sec. 3112:18.

45 Ibid, Sec. 3812:1.

48 Ibid, Sec. 3812:1.

47 Low Rental Housing Manual (12/13/49), Sec. 207.1.

48 Low Rent Bulletin 12 (June 1950) Construction Contract.

17

for architects; 49 the same for all contracts for services

and supplies; 50 the same with respect to all leases of fed

erally-owned housing projects; 51 52 53 54 55 the same with respect to

the hiring policies and procedures of the local authority; 62

the same with regard to the personnel actions of P.HA

itself; 68 require that racial factors be takgn into considera

tion in connection with selection of sites; 64 require that the

land area available to minority groups not to be reduced; 55

require no discrimination with respect to persons to be

employed by the local authority for the purpose of con

ducting surveys.56

The Development Program, which is a form prepared

by PHA for use by the local authority for presentation

of all relevant data in connection with application for fed

eral assistance and which must be approved by PHA before

such assistance is given, requests, for example, relevant

data concerning the local agency’s present program,57 site

occupants,58 59 neighborhood characteristics,69 proposed proj

ect occupants,60 and displaced families,61 separately for

white and non-white families.

49 Ibid, these requirements made pursuant to Executive Orders.

50 Manual of Policy & Procedure (5/25/49), Sec. 3810:1, Pur

suant to Executive Order.

51 Manual of Policy & Procedure (5/25/49), Sec. 3810.1.

52 PHA Form-1996 (June 1950) Annual Contribution Contract,

Sec. 113.

53 Manual of Policy & Procedure (9/25/50), Sec. 3110:1,

6110:1.

54 Low Rental Housing Manual (7/28/50), Sec. 208.1 3 B.

55 Low Rent Housing Manual (7/14/50), Sec. 208:16.

58 Form PHA-1922 (2/15/50) Proposal for Survey.

57 Form PHA-1954, Rev. July 1950. 101.

58 Ibid, 201, 203.

59 Ibid, 207.

60 Ibid, 103.

61 Ibid,224.

18

These considerations and requirements imposed by PH A

on the local agency, with respect to its determinations and

policies involving race, bespeak PHA’s authority and the

extent of its involvement in such local considerations and

determinations.

II. The Establishm ent O f F red W essels Hom es As

A P ro jec t L im ited To O ccupancy By W hite Low In

come Fam ilies V iolates R ights Secured To A ppellants

By The Laws, C onstitution A nd Public Policy O f The

U nited States.

A. The R ight C onferred On A ppellan ts By

The Basic S ta tu te

Appellants are low income families meeting all require

ments established by law for admission to the low rent

project here in controversy, which is being built on the

site of their present or former residence and from which

they will be excluded and denied admission solely because

they are not white families. The limitation to occupancy

by white families is a determination which Appellees con

tend the local agency, the Housing Authority of Savannah,

Georgia, is permitted to make. But this determination has

been specifically approved by Appellees (Appellants’1 Ap

pendix 10-11).

Under the basic statute, Appellants have a preference

for admission to low rent bousing by virtue of the fact that

they are families which are to be displaced and which have

been displaced to make way for the construction of a proj

ect initiated after January 1, 1947.82 The act requires

that every contract for annual contributions between PH A

and the local agency ‘ ‘ shall require that the public housing

agency, as among low-income families which are eligible

82 Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 888, as amended by Act

of July 15, 1949, c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 423, Title 42, United States

Code, Sec. 1410(g).

19

applicants for occupancy in dwellings of given sizes and at

specified rents, shall extend” this preference in the selec

tion of tenants.6211

The contract between Appellees and the local housing

authority in this instance contains this provision, which

Congress obviously intended be included for the specific

benefit of displaced families, and which displaced families

may sue to enforce. Compare Young v. Kellex Corp., 82 F.

Supp. 953 (U. S. D. C. E. D. Tenn.); Crabb v. Welden Bros.,

65 F. Supp. 369 (IJ. S. D. C. S. D. Iowa), reversed on

other grounds, 164 F. 2d 797.

A federal district court has ruled enforcement of

racial segregation in housing developments aided under this

act, violates urgency of need preference rights, 63 Stat.

422, Title 42, U. S. C. §8(c), secured to qualified low

income families by this provision. Woodbridge, et al. v.

Housing Authority of Evansville, et at., Civil No. 619.

U. S. D. C. S. D. Ind. (Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law, filed July 6, 1953.)

The right of Appellants to a preference for considera

tion for admission and admission to Fred Wessels Homes

is thus violated by Appellees through their sanction of the

limitation to white occupancy.

B. Protection Afforded By The Federal Civil

Rights Statutes

The basic Federal legislative safeguard against segre

gation in Federally-aided low rent public housing projects

is one of the Federal Civil Rights Statutes passed by the

Congress to implement and give effect to the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution. This provision,

as presently contained in the United States Code, Title 8',

Section 42 (14 Stat. 27) provides as follows:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right in every state and territory, as is en-

62a Ibid.

20

joyed by white persons thereof, to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty.” [Act of April 9, 1866, c. 31, Sec. 1 (R. S.

1978).]

The United States Supreme Court in its decisions has

noted that Congress considered the right to acquire an

interest in real property so vital to the enjoyment of all

other liberties that it first enacted this provision in 1866

before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment.68 In

invoking the protection afforded by this provision, the

Supreme Court has held, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60,

79 (1917), that it operates “ to qualify and entitle a colored

man to acquire property without state legislation discrim

inating against him solely because of color.” Accord:

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 11-12 (1948). The high

Court has also held that this provision protects the right

of Negroes to acquire an interest in real property free

from discriminatory action on the part of the Federal gov

ernment. Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 (1948).

In Woodbridge, et al. v. The Housing Authority of

Evansville, et al.,&i a Federal district court ruled that the

right to “ lease” property is a civil right protected by

this enactment from discrimination on the basis of race

or color. In that case, qualified low income Negro families

had been denied consideration for admission and admis

sion to a new low rent project built pursuant to the pro

visions of the basic statute involved in this case. The de

fendant local housing officials had defended on the ground

that separate facilities ( a PWA project built 16 years prior

thereto) had been provided, and would be provided by

the proposed program, for low income Negro families. The 63 64 *

63 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 10-11 (1948). This statute

was reenacted by the Congress after the Fourteenth Amendment was

adopted. Act of May 31, 1870, Sec. 18 (16 Stat. 140, 144, c. 114).

64 U. S. D. C. S. D. Ind. Civil Action No. 618, Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law, filed July 6, 1953.

21

district court ruled that the denial of consideration for

admission and the denial of admission, solely because of

race and color, violated this provision. Likewise with re

gard to the policy of enforced racial segregation “ in public

housing financed by public funds and supervised and con

trolled by public agencies.”

In Va/m, et al. v. Toledo Metropolitan Mousing Author

ity, a case similar to the Woo(lbridge case, another federal

district court made similar rulings with regard to this

Civil Bights Statute.05

Thus the right of Negroes to “ lease” or to acquire any

interest in real property, including Federally-aided low

rent public housing, free from restrictions imposed by the

State or Federal governments which are based upon race

and color is specifically protected by Federal legislation.

C. Protection Afforded By The Constitution Of

The United States

PHA is authorized by the basic statute to make loans,60

annual contributions,67 and capital grants68 to public

housing agencies which have been established pursuant to

state enabling legislation.69 One of the basic amendments

to the 1937 Act by the 1949 Act is an amendment which

requires that there be local determination of the need for 65 66 67 68 69

65 U. S. D. C. N. D. Ohio, Civil Action No. 6989 Journal Entry

and Memorandum Opinion filed June 24, 1953.

66 Act of Sept. 1, 1937, c. 896, 50 Stat. 891, as amended July 15,

1949, c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 425, 426, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1409.

67 Ibid, 50 Stat. 892, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338,

Title III, 63 Stat. 427, Title 42 U. S. C., Sec. 1410.

68 Ibid, 50 Stat. 891, 893, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949,

c. 338, Title III, 63 Stat. 430, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1411.

69 Ibid, 50 Stat. 889, as amended by Act of July 15, 1949, c. 338,

Title III (11), 63 Stat. 429, Title 42, U. S. C„ Sec. 1402(11).

22

low-rent housing in the community involved.70 It provides

that the local governing body must, by resolution, approve

the application of the local public agency for a preliminary

loan and must enter into a cooperation agreement with the

local public agency. In other words, the project must be

the result of state as well as federal action. No provision

of the basic statute requires or permits local public agencies

or PH A to determine by which race or color of low income

families a particular project assisted under the Act shall

be occupied. PHA permits local authorities to decide the

racial occupancy patterns which shall obtain in the various

projects of the local program. This determination is set

forth in the Development Program, the basic document sub

mitted to the PHA by the local agency for PHA’s approval

of the local program. Once PHA approves the Develop

ment Program, the local program then becomes a joint

venture or partnership arrangement whereby the state

g'overnment, through one of its subdivisions or agencies,

and the federal government, through PHA, jointly carry

out the planning, construction, operation, and maintenance

of the projects. The housing unit made available to a

qualified low income family is therefore distinctly public—

the product of combined federal-state action, to which

federal constitutional proscriptions are applicable.

1. The F ourteen th A m endm ent

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution

has consistently been construed by the United States

Supreme Court as prohibiting discriminatory state action

based solely on race and color, and has been held to enjoin

such action on the part of the state, whether the result

of action on the part of its legislative arm, Strauder v.

West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1880) ; Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U. S. 60 (1917); its judicial arm, Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U. S. 1 (1948); Barrows v. Jackson, United States

70 Ibid, 63 Stat. 422, Title 42, U. S. C., Sec. 1415(7).

23

Supreme Court, Oct. Term, 1952, No. 512 decided June

15, 1953; or its administrative arm, Ex parte Virginia,

100 U. S. 339 (1880).

In cases involving suits against local housing authorities

to enjoin racial discrimination in low rent public housing

where the local authority has determined upon a policy

of racial discrimination, including racial segregation

policies, the constitutional question which arises is whether

the defendant members of the local authority, who are the

administrative or executive arm of the state, may enforce

a policy which results in denying the Negro plaintiffs, who

are qualified low income families, the right to occupy real

property, a unit in a public housing project, solely because

of race and color.

In Buchanan v. Warley, supra, the United States

Supreme Court declared unconstitutional action on the part

of the legislative arm of the state, a city ordinance, designed

to bar Negroes from occupying as homes houses in blocks

where the majority of residences were occupied by white

families. The ordinance similarly denied white persons

the right to occupy houses in blocks where the majority

of houses were occupied by Negro families. In striking

down this legislative fiat the court said, at page 79:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment and these statutes

enacted in furtherance of its purpose operate to

qualify and entitle a colored man to acquire property

without State legislation discriminating against him

solely because of color.”

The court said that the “ concrete question” before it

was, at page 75:

“ May the occupancy, and necessarily, the pur

chase and sale of property of which occupancy is an

incident, be inhibited by the State or by one of its

municipalities, solely because of the color of the

proposed occupant of the premises?”

24

The precise question decided by the court in this case,

however, was whether the white seller, who brought the

action for specific performance of the contract for the sale

of his property to the Negro contract vendee, had the right

to dispose of his property free from racial restrictions

imposed by the state. The court held that the ordinance in

question deprived the white seller of his right to dispose

of his property in violation of due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

But in Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, at page 12, the court

again pointed out that such legislative restrictions are also

constitutionally invalid when applied to bar a Negro who

seeks to occupy real property in certain residential areas.

The court said that this was made clear by its disposition

of the cases of City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704

(1930) and Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668 (1927). In

both cases the high Court reversed lower court decisions

upholding legislative restrictions on Negro occupancy by

merely citing Buchanan v. Warley, supra. Since Shelley

v. Kraemer, supra, the Supreme Court has denied certiorari

in City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F. 2d 859 (1951), cert,

den. 341 U. S. 940 (1951) where a similar legislative restric

tion against Negro occupants was struck down by the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

In Shelleys. Kraemer, supra, the United States Supreme

Court held violative of the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment action on the part of the judicial

arm of the state which resulted in prohibiting Negroes from

occupying homes in certain residential areas from which

private individuals sought to exclude them' by private race

restrictive covenants. In order to be effective against

breach, these agreements required action on the part of

the state’s judiciary. The court held that where the

judiciary took action to enforce the discriminatory covenant,

the discrimination ceased to be private action and became

the action of the state. The court said, at page 10:

25

“ It cannot be doubted that among the civil rights

intended to be protected from discriminatory State

action by the Fourteenth Amendment are the rights

to acquire, enjoy, own and dispose of property.”

In Barrows v. Jack-son, supra, the United States

Supreme Court ruled that a state court could not, consistent

with the same constitutional prohibition on state action,

award damages for breach of a private racial restrictive

covenant designed to bar Negroes from occupying certain

residential property, since such action on the part of a

state court deprives Negroes of the right secured to them

by the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to occupy real property free from state-imposed

restrictions based solely upon race and color. The Court

had previously ruled in Shelley' v. Kraemer, supra, that a

state court could not, consistent with the same constitutional

proscription, give effect to or enforce such covenants by

the issuance of any injunction.

Thus, the United States Supreme Court has specifically

struck down action on the part of both the legislative and

judicial arm of the state which results in denying Negroes

the right to occupy certain real property, holding such

action violative of rights secured to Negroes by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution. The ques

tion in each of these cases was state action. The result

did not turn on the fact that a particular arm of the state,

legislative or judicial, was involved.

In Allen v. Oklahoma City, 175 Okla. 421, 424, 52 Pac.

1054, 1058 (1935), the Supreme Court of Oklahoma struck

down as invalid and void an executive order issued by the

Governor of the State of Oklahoma requiring racial segre

gation in residential areas.

In Vann, et al. v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Au

thority, supra, and Woodbridge, et al. v. The Housing

Authority of Evansville, et al., supra, two federal district

courts have squarely held that local public housing au-

26

tliorities may not, consistent with the Fourteenth Amend

ment, enforce a policy of racial segregation in federally-

aided low rent public housing projects.

A similar ruling involving federally-aided projects was

made by the Superior Court of San Francisco in Banks,

et al. v. San Francisco Housing Authority?11 and by the

Superior Court of Essex County, New Jersey in Seawell,

et al. v. MacWithey, et al.,12 involving a state-aided veterans

public housing project.

The effect of these rulings is to bring the State’s execu

tive or administrative arm under constraint of Fourteenth

Amendment prohibitions, where property rights are in

volved.

a. The Separa te But Equal D octrine

In Favors v. Randall, 40 F. Supp. 743 (1941), a federal

district court applied the separate but equal doctrine in a

case involving racial segregation in Federally-aided low

rent public housing projects. In that case, the complaint

alleged that Negroes were being discriminated against by

the certification of tenants for occupancy on the basis of

race and color. The court in denying a temporary injunc

tion found that Negroes were to receive a larger propor

tionate share of the available units than their propor

tionate need determined. The court concluded from this

fact that there was no discrimination, as alleged, and ruled

that since the Fourteenth Amendment required a “ legal”

equality as distinguished from “ social” equality, no Con

stitutional rights of the plaintiffs had been violated. The

court, relying on Plessy v. Ferguson,13 expressly rejected 71 72 73

71 Superior Court in and for San Francisco County, No. 420534,

October 1st, 1952.

72 2 N. J. Super. 255, 63 Atl. 2d 542 (1949); reversed on other

grounds, 2 N. J. 563, 67 Atl. 2d 309 (1949).

73163 U. S. 537 (1896).

27

the argument of the attorneys for the plaintiffs that “ equal

rights” could be secured only by “ enforced commingling

of the two races” .

In Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, the United States Supreme

Court for the first time specifically upheld the doctrine of

separate but equal. The Court ruled in that case that the

state’s requirement of separate but equal railroad facilities

for Negro and white passengers did not violate any rights

secured to the individual by the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amednment to the Federal Constitution.

Twenty-one years later the high Court was asked to hold the

same with respect to the state’s requirement of racial

segregation in housing in Buchanan v. Warley, supra, but

the Court expressly refused to do so. The Court said, at

page 79 :

“ The defendant in error insists that Plessy v.'--.

Ferguson, * * * is controlling in principle in favor

of the judgment of the court below * * * it is to be

observed that in that case there was no attempt to

deprive persons of color of transportation in coaches

of the public carrier, and express requirements were .

for equal though separate accommodations for white

and colored races * *

“ As we have seen, this court has held laws valid

which separated the races on the basis of equal

accommodations in public conveyances, and courts of

high authority have held enactments lawful which

provide for separation in the public schools of white

and colored pupils where equal privileges are given.

But, in view of the rights secured by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution, such legis

lation must have its limitations, and cannot be sus

tained where the exercise of authority exceeds the

restraints of the Constitution. We think these limi

tations are exceeded in laws and ordinances of the

character now before us” (p. 81).

In Favors v. Randall, supra, the court made no refer

ence to Buchanan v. Warley, supra, or to Title 8, Section

42, United States Code. Instead of following the Buchamm

case, the court in the Favors case reverted to Plessy v.

Fergmon and held separate but equal applicable. This

may have been due to the fact that plaintiff did not argue

that property rights protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment and Title 8, U. S. C., Sec. 42, were involved, but

argued that “ social rights” or the right of persons to

“ commingle” wTas at stake.

Since the decision of the federal district court in the

Favors case, the United States Supreme Court has decided

the Restrictive Covenant Cases where it expressly affirmed

Buchanan v. Warley, supra, and again rejected a separate

but equal argument. In Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, the

Court was asked by the covenantors to consider that Ne

groes might enter into restrictive agreements barring

whites from their neighborhoods. In rejecting this argu

ment, the Court said, at pages 21-22 :

“ Respondents urge, however, that since the

state courts stand ready to enforce restrictive cove

nants excluding white persons from the ownership

or occupancy of property covered by such agree

ments, enforcement of covenants excluding colored

persons may not be deemed a denial of equal pro

tection of the laws to the colored persons who are

thereby affected. This contention does not bear

scrutiny. The parties have directed our attention

to no case in which a court, state or federal, has been

called upon to enforce a covenant excluding members

of the white majority from, ownership or occupancy

of real property on grounds of race or color. But

there are more fundamental considerations. The

rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amednment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the

individual. The rights established are personal

rights. It is, therefore, no answer to these peti

tioners to say that the courts may also be induced

to deny white persons rights of ownership and oc

cupancy on grounds of race or color. Equal pro

tection of the laws is not achieved through indis

criminate imposition of inequalities.”'

29

*

In Woodbridge et al. v. The Housing Authority of

Evansville, Indiana, et al., supra, the federal district court

ruled the separate but equal doctrine inapplicable to prop

erty rights.

The court, in its Conclusions of Law, said:

“ That the defendants’ theory of defense, namely

that plaintiffs and members of their class are not

being discriminated against due to the defendants’

furnishing ‘ separate but equal ’ low rent public hous

ing facilities to plaintiffs and members of their class,

is not tenable in view of the weight of authority as

expressed in a large majority of recent decisions.

As stated in a decision rendered June 24, 1953 by

Judge Prank L. Kloeb of The United States District

Court for the Northern District of Ohio, in an action

involving a similar situation, ‘ You must bear in mind

here that we have projects erected with public funds,

erected by the Government of the United States, and

the Government does not segregate its tax receipts.

* * * We are here dealing Avith property rights as

distinguished from the mere right to a public service. ’

“ It is the conclusion of this court, that the case

of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, decided in 1895,

on which defendants heavily rely to sustain their

‘separate but equal’ theory of defense, has, by many

decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States

in recent years, lost most, if not all, its weight as a

guide in cases concerning ownership or occupancy of

real property as distinguished from those cases in

volving a public service.

‘ ‘ In the case at hand, we have more than a public

service. Here we have a contractual relation in

volving a lease of real property for which the tenant

must pay a valuable consideration in the form of

monthly rent.”

In Vann, et al. v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Author

ity, supra, the federal district court said in its Memo

randum Opinion:

30

“ The trend of all of the later cases involving

property rights is to conform strictly with the re

quirements of the Fourteenth Amendment and of the

Civil Rights Statutes.”

In Banks, et al. v. San Francisco Housing Authority,

supra, the Superior Court of San Francisco said:

‘ ‘ The main question posed, then, at this stage by

demurrer, is whether or not this public agency can

exclude Negro persons solely because they are

Negroes, from five of these projects and segregate

them into the sixth. Is such segregation unlawful

discrimination?

“ The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States has uniformly been held to

protect all persons, white or colored, against dis

criminatory legislation or action by the states or its

agencies. It is the contention of the Housing Au

thority that they comply with this basic law in offer

ing Negroes equal accommodations and facilities

separately at Westside, even though they deprive

them of the right to admission at the five other

developments.

“ However, it is clear to the Court that although

at one time the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine was

upheld as not being discriminatory treatment and

followed in certain types of activities, nevertheless,

since it was first enunciated in the Plessy v. Fergu

son case (163 U. S. 537) (1895), it has in later years

lost its force by reason of the holdings in many other

cases showing that it has no application to owner

ship or occupancy of real property. Discrimination

by segregation of housing facilities and attempts to

control the same by restrictive covenants have been

outlawed by our Supreme Court. * * *

“ By extension of the logic and reason of those

cases, it is apparent that that doctrine should not

apply to a public housing project, financed by public

funds and supervised and controlled by a public

agency. ’ ’

b. Police Power And Property Values

In Buchanan v. Worley, supra, justification for the city

ordinance requiring residential racial segregation was

sought on several grounds. One ground was that the state

had the power to pass such an ordinance in the exercise of

the police power “ to promote the public peace by prevent

ing racial conflict”.

In response to this argument the Court said,, at pages

74-75:

“ The authority of the state t<| pass laws in the

exercise of the police power, having for their object

the promotion of the public health, safety, and wel

fare, is very broad, as has been affirmed in numerous

and recent decisions of this court. % * * But it is

equally well established that the police power, broad

as it is, cannot justify the passage of a law or ordi

nance which runs counter to the limitations of the

Federal Constitution; * * *

“ True it is that dominion over property spring

ing from ownership is not absolute and unqualified.

The disposition and use of property may, be con

trolled, in the exercise of the public health, con

venience, or welfare. * # * Many illustrations might

be given from the decisions of this court and other

courts, of this principle, but these cases do not touch

the one at bar.

“ The concrete question here is: May the occu

pancy, and, necessarily, the purchase and sale of

property of which occupancy is an incident, be in

hibited by the states, or by one of its municipalities,

solely because of the color of the proposed occupant

of the premises?”

1/ * * *

“ That there exists a serious difficult problem

arising from a feeling of race hostility which the law

is powerless to control, and to which it must give a

measure of consideration, may be freely admitted.

But the solution cannot be promoted by depriving

citizens of their constitutional rights” (at pp. 80-81).

32

Another ground was that in the exercise of the state’s *

police power, the state had the power to pass the ordinance

since “ it tends to maintain racial purity.”

In response to this argument the court Said, at page 81:

“ Such action is said to be essential to the main

tenance of the purity of the races, although it is to

he noted in the ordinance under consideration that

the employment of colored servants in white families

is permitted, and nearby residences of colored per

sons not coming within the blocks, as defined in the

ordinance, are not prohibited.

“ The case presented does not deal with an

attempt to prohibit the amalgamation of the races.

The right which the ordinance annulled was the civil

right of a white man to dispose of his property if

he saw fit to do so to a person of color, * * * ”

Another ground on which justification for the ordinance

was sought was that colored purchases depreciated prop

erty in white neighborhoods.

In response to this argument the court said, at page 82:

“ But property may be acquired by undesirable

white neighbors, or put to disagreeable though law

ful uses with like results.”

2. The Fifth Amendment

The due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the

Federal Constitution has been construed as affording pro

tection against discriminatory action on the part of the

national government if based solely upon race, color or

ancestry. See, Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81,

100 (1943); Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216

(1944); Wong Yim v. United States, 118 F. 2d 667, 669

(1941) cert. den. 61 S. Ct. 1112 (1941). It is clear from