Background - Lynch v. Gilmore

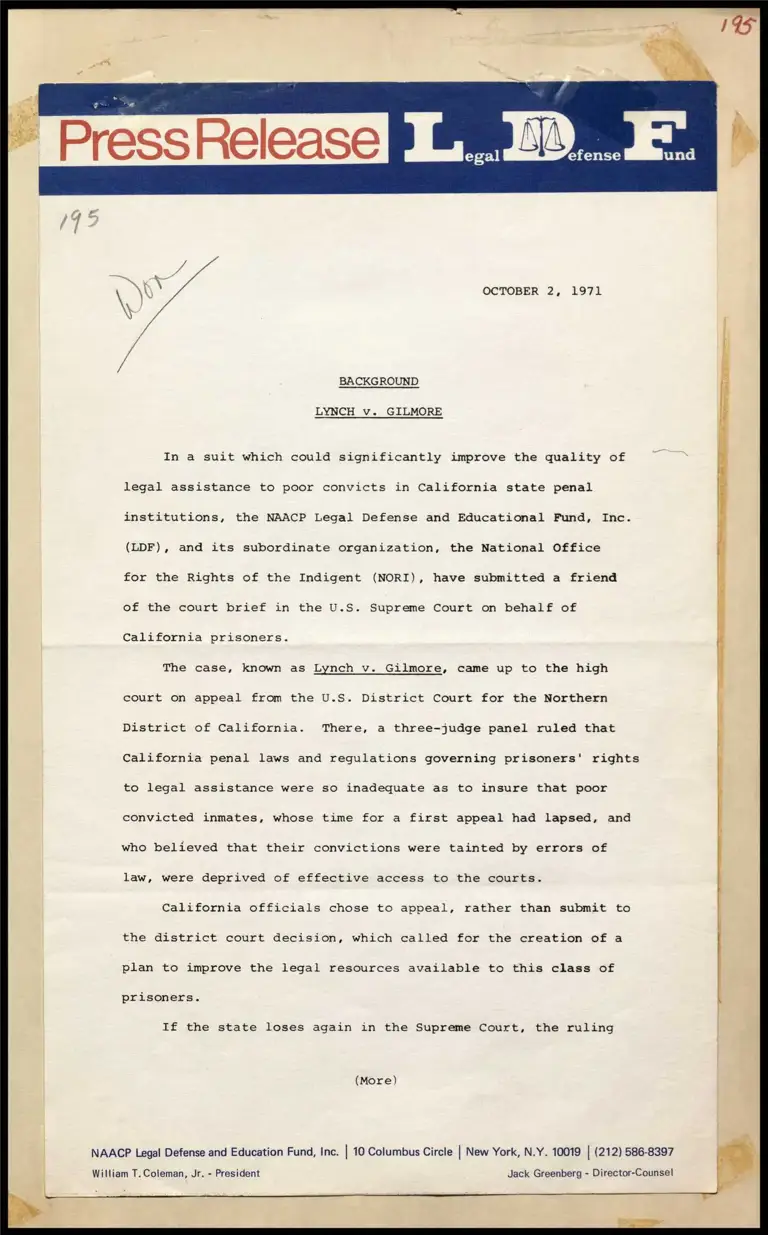

Press Release

October 2, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Background - Lynch v. Gilmore, 1971. b83ac3ac-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb8684ae-fa98-4a1e-974a-1e8dcd8abf58/background-lynch-v-gilmore. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

OCTOBER 2, 1971

BACKGROUND

LYNCH v. GILMORE

In a suit which could significantly improve the quality of

legal assistance to poor convicts in California state penal

institutions, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF), and its subordinate organization, the National Office

for the Rights of the Indigent (NORI), have submitted a friend

of the court brief in the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of

California prisoners.

The case, known as Lynch v. Gilmore, came up to the high

court on appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Northern

District of California. There, a three-judge panel ruled that

California penal laws and regulations governing prisoners' rights

to legal assistance were so inadequate as to insure that poor

convicted inmates, whose time for a first appeal had lapsed, and

who believed that their convictions were tainted by errors of

law, were deprived of effective access to the courts.

California officials chose to appeal, rather than submit to

the district court decision, which called for the creation of a

plan to improve the legal resources available to this class of

prisoners.

If the state loses again in the Supreme Court, the ruling

(More)

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

BACKGROUND ~- LYNCH v. GILMORE PAGE TWO

could have substantial direct and indirect impact on many in-

adequate prison systems around the country.

According to LDF's amicus brief, California has no law

which requires the state to inform convicted felons of their

constitutional right to appeal, nor to inform poor convicted

felons of their right to assigned counsel for their first appeal.

Ignorance of these rights, LDF/NORI contend, has led to a

relatively small number of appeals (from 1964 through 1968 only

5% of California's convicted felons appealed their cases).

Once the time for appeal has lapsed, claims of error in

criminal convictions or sentences must be presented in post-

conviction collateral proceedings (e.g. habeas corpus, coram

nobis), for which the state does not provide counsel. Thus those

prisoners unable to afford private counsel must depend on what-

ever legal assistanee the state might provide in preparing these

crucial pleadings. In California, law libraries are maintained

in each of the state's 12 prisons.

Ironically, this case began in reaction to a new penal

regulation purporting to "standardize" these libraries. The

California Department of Corrections, to implement its regulation,

published a list of Law books which were to be kept in the prisons.

The regulation also provided for the confiscation of those law

books and materials not on the prescribed list. The result,

according to LDF/NORI, amounted to a "veritable book burning "

And the lower court found the "approved" book list grossly in-

adequate, even for the limited purpose of preparing and presenting

post-conviction pleadings, thus barring indigent prisoners of

effective access to the courts and violating their rights to due

process.

(more)

BACKGROUND - LYNCH v. GILMORE PAGE THREE

Also under contention is whether the California penal

practices violated the equal protection clause as well. LDF/NORI

claim that California imprisons only a fraction of its convicted

felons. Those who receive suspended sentences or are released on

parole are free to hold jobs and thus afford an attorney, or to

use the vast resources of public law libraries to fight con-

victions, while the state provides no parallel resource for those

unfortunate enough to be imprisoned for similar crimes.

To demonstrate some of the inequities and costly consequences

of the present system, LDF/NORI took statistics from the 1970

Annual Report to the Governor and the Legislature (of California).

According to this report, in fiscal year 1968-1969, some 6,200

post-conviction applications were filed by prisoners in various

state courts. Of these, about 5,300 were denied without hearing

or written opinion. LDF/NORI believe that many of these denials

resulted from errors in venue and a general lack of knowledge

about important facts of law on the part of prisoners.

Were prisoners provided with proper legal assistance, the

brief suggests, frivolous or unacceptable arguments might have

been screened out before they bogged down California's overcrowded

courts, and, more importantly, meritorious claims, if prepared

with some legal expertise or guidance, would not run the risk of

being overlooked in a deluge of frivolous claims.

California officials continue to assert, as they did in lower

court, that state-supported legal assistance to indigents is not

a right, but a privilege; that any plan to improve the quality of

legal resources would necessitate the spending of additional

state monies and amount to a "raid on the state treasury" in

violation of the Eleventh Amendment. Both arguments were found

(more)

BACKGROUND - LYNCH v. GILMORE PAGE FOUR

to be without basis in the lower court.

The interest of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent in

this case stem from their initiation of more than 63 class

action and individual suits against prisons and jails on behalf

of poor inmates. Their experience, while highly successful, has

also been frustrating. Atrocious conditions -- both physical

and administratively imposed -- are commonplace in all but a

handful of American prisons and jails. Under present circumstances.

the legal job is endless.

Aside from the substantial benefits which would accrue to

poor California convicts should the Supreme Court uphold their

right to effective access to the courts as being paramount,

the tool of legal recourse -- guaranteed in theory though not in

fact to the majority of American prisoners -- could provide the

strongest impetus for prison reform from within.

=30-