Simmons v Brown Reply Brief for Plaintiffs Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 29, 1979

21 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simmons v Brown Reply Brief for Plaintiffs Appellants, 1979. 7d3bd36c-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cb9b5a06-ced8-4fa9-ab58-b277741dd08e/simmons-v-brown-reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

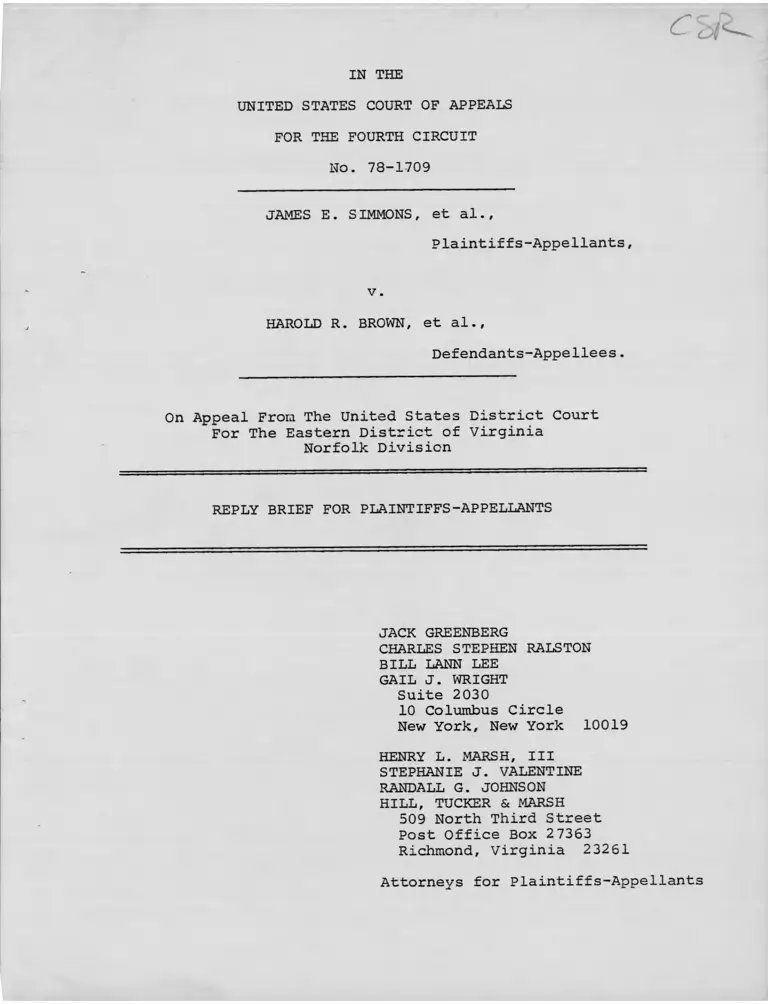

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-1709

JAMES E . SIMMONS, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

HAROLD R. BROWN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

IN THE

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Virginia

Norfolk Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

GAIL J. WRIGHT

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

HENRY L. MARSH, III

STEPHANIE J. VALENTINE

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

509 North Third Street

Post Office Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-1709

JAMES E. SIMMONS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

HAROLD R. BROWN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Virginia

. Norfolk Division

REPLY BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

In their brief, the defendants-appellees urge two

points: first, that the district court properly dismissed

the class action on the ground the named plaintiffs were not

proper class representatives; and second, that the district

court in fact made a full Rule 23 determination in reaching

its finding that the requirements for class certification had

not been met. Both of these assertions are patently incorrect.

ARGUMENTS

1. Plaintiffs in their motion for summary reversal

and in their main brief present an exhaustive discussion which

TABLE OF CONTENTS

preliminary Statement............................... 1

Argument............................................. 1

Conclusion........................................... 12

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Allen v. Likins, 517 F.2d 532 (8th Cir.1975)...... 10

Arkansas Educ. Assn. v. Bd. of Educ. of Portland

446, F . 2d 763, 767 (8th Cir. 1971)................ 9

Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543 (4th

Cir. 1975).................................................... 10

Barrett v. united States Civil Service Comm.,

14 FEP Cases 1007 (D.D.C. 1977)................. 10

Basil v. Knebel, 551 F.2d 395, 397 (D.C. Cir. 1977) 7

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d

437, 442 (5th Cir. 1974)....................... 12

Berman v. Narragansett Racing Assn., 414 F.2d 311,

317 (1st Cir. 1969).............................. 9

Brown v. Gaston Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377

(4th Cir. 1972)cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972) 11

Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp., 483 F.2d 300 (5th

Cir. 1973)........................................ 4

Chrapliwy v. uniroyal, Inc., ____ F.Supp.____ , 7

FEP Cases 343, 345 (N.D. ind. 1974)............. 12

Donaldson v. pillsbury, 554 F.2d 825, 832-834

(8th Cir. 1977) (plaintiffs' Brief 12-13)....... 4,8

Page

-l-

East Texas Motor Freight v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395

(1977)............................................ 3,6

Ellis v. Naval Air Newark Facility, 404 F.Supp.

391 (N.D. Ca., 1975).............................. 10

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co., 423 U.S. 814 (1976). 5,6'

Geraghty v. united States parole Commission, 579

F.2d 238, 245-254 (3rd Cir. 1978)................ 7

Goodman v. Schlesinger, 584 F.2d 1325 (4th Cir.

1978).................. 2

Huff v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973) 4

international Brotherhood of Teamsters v. united

States, 431 U.S. 324............................. 5,6

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122

(5th Cir. 1969)................ 11

Lamphere v. Brown university, 553 F.2d 714, 719

(1st Cir. 1977)...... 5

Lasky v. Quinlan, 558 F.2d 113, 1136-37 (2nd Cir.

1977)..... 7

Leisner v. N.Y. Telephone Co., 358 F. Supp. 359

(S.D.N.Y. 1973)............... 9

Long v. Sapp, 502 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1974)......... 11

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792,

805 (1973)........................................ 5

Pettway v. American Cast iron pipe Co., 494 F.2d

211, 257-258 (5th Cir. 1974).................... 4

Phillips v. Klassen, 520 F.2d 362, 366 (D.D.C. Cir.

1974)............................................. 8

price v. Lucky Stores, Inc., 501 F.2d 1177, 1179

(9th Cir. 1974).................................. 3

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th

Cir. 1972).... 12

Page

-ii-

Page

Satterwhite v. City of Greenville, 578 F.2d 987

(5th Cir. 1978)................................ . 5,6

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511 (6th

Cir. 1976)........................................ 12

Sperry Rand Corp. v. Larson, 554 F.2d 868 (8th Cir.

1977)............... 9

United States Transportation union, Local 574 v.

Norfolk & Western Ry„, 532 F.2d 336 (4th Cir. 1975) 4

V.Jo Rockier & Co., v. Graphic Enterprises, Inc.,

52 F.R.D. 335 (D. Minn. 1971)................... 8

Walker v. World Tile Group, 563 F.2d 918, 921

(8th Cir. 1977).... ............................. 7,8

Wells v. Ramsey Scarlett and Company, Inc., 506 F.2d

436 (5th Cir. 1975).............................. 9

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual ins. Co., 508 F.2d 239

(3rd Cir. 1975).................................. 8

White v. Nassau County Police Dept., 15 FEP Cases

266 (S.D.N.Y. 1977).............................. 10

Williams v. City of New Orleans, ____ F.Supp.____

18 FEP 347 (E.D0 La. January 14, 1978)......... 10

Winokur v. Bell Federal Sav. & Loan Ass'n., 560

F. 2d 271, 274 (7th Cir. 1977)................... 10

Zurak v. Regan, 550 F.2d 113, 1136-37 (2nd Cir. 1977) 7

Secondary Authorities

Manual for Complex Litigation, part I §1.40........ 4

-ill-

demonstrates that the lower court failed to comply with this

Court's mandate. Plaintiffs rely on this Court's recent decision

in Goodman v. Schlesinger, 584 F.2d 1325 (4th Cir. 1978), and

submit that at least this case should be remanded to the district

court so that the other class members will have the opportunity

to come forward. The defendants make a futile attempt to dis

tinguish Goodman on grounds which do not withstand analysis.

In Goodman, the district court decided the question of class

action certification prior to class discovery being conducted.

Accordingly, the Court of Appeals found that there was not enough

evidence in the record to make a proper determination. In the

instant case the facts which lead to a Goodman ruling are even

more compelling. Here, there was no Rule 23 determination at

all! Class certification was denied on the grounds that the named

plaintiffs were not proper representatives because of the deter

mination on the merits of their individual claims that they had

not been discriminated against. Assuming, arguendo, that the

Court below was correct in not reconsidering the individual

claims, the posture of the present case now is even less favor

able to the government than in Goodman, since there the Court had

decided the Rule 23 issues, albeit prematurely. Both Goodman

and the instant case involve the same essential elements:

(1) a failure to properly decide class certifications; and

(2) a decision on the merits of the individual claims. In both

cases, a remand is required.

2

2. Defendants contend that the district court's

cryptic statement, in its order denying reconsideration of

its denial of a class action, that "the pleadings and facts

presented fail to establish any basis for certifying a class

action," was a decision on the merits of the Rule 23 issues.

We submit that if such was the lower court's intention, then

it failed to comply with the requirements of Rule 23, viz.,

that it make specific findings and explain in what way the

requirements of Rule 23 were not met. With all due respect

to the Court below, it appears to us that the one sentence

pronouncement is no more than an afterthought. The basis for

both the original order denying a class action and the order

denying reconsideration was clearly the Court's reading of

East Texas Motor Freight v, Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395 (1977).

The Court's determination which fails to describe

the material facts or disclose the reasons on which the

decision is based is insufficient. Price v. Lucky Stores,

Inc,, 501 F .2d 1177, 1179 (9th Cir. 1974). Although defend

ants contend that "the lower court considered and weighed

the pleadings and facts," it is clear that they have no basis

for supposing that such was the case, and in fact even if it

were the court certainly did not consider all of the class

wide evidence which plaintiffs had not discovered nor pre

sented. (Defendants'Brief, p. 11).

-3-

3. The defendants in their argument attempt to

camouflage the fact that plaintiffs were not provided an

opportunity to conduct or present classwide discovery by

stating that the "doors to the Civilian Personnel Office

were opened ..." (Defendants' Brief, p. 5). This discovery'

which defendants describe as being extensive and inclusive

of various personnel papers, was conducted for class certifi

cation purposes, and is not to be confused with the broad

scope of discovery which would be needed to prove the merits

of classwide discrimination. See, e.g., Burns v. Thiokol

Chemical Corp., 483 F.2d 300 (5th Cir. 1973). See also, Huff

v. N.D. Cass Co., 485 F.2d 710 (5th Cir. 1973). The courts

have held that although limited discovery could be conducted

for pre-certification purposes, broader discovery should be

subsequently conducted pertaining to the merits of the allega

tions of classwide discrimination. See, e.g., United States

Transportation Union, Local 574 v. Norfolk & Western Ry., 532

F.2d 336 (4th Cir. 1975); Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Co. , 494 F.2d 211, 257-258 (5th Cir. 1974). This practice is

not only sanctioned by the courts, but the Manual for Complex

Litigation recommends that discovery be conducted in "sequential

waves"; the first wave limited to the class question followed

by discovery on the merits. See Manual for Complex Litigation,

Part I § 1.40. Had this process been followed, the individual

named plaintiffs could have presented their claims in light of

the classwide evidence. See, e.g., Donaldson v. Pillsburv, 554

F.2d 825, 832-834 (8th Cir. 1977) (Plaintiffs' Brief 12-13).

-4-

The Supreme Court has recognized that an individual

claim of discrimination cannot be decided without first de

ciding whether there is a classwide pattern or practice of

discrimination. See, e.g., International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324; Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

423 U.S. 814 (1976); McDonnell Douglas Corp v. Green, 411 U.S.

792, 805 (1973). The circuit courts in following this prin

ciple have expressly required that the plaintiff be permitted

to establish the classwide issue prior to a determination of

the individual claim. See, e.g., Lamphere v. Brown University,

553 F.2d 714, 719 (1st Cir. 1977); Burns v. Thiokol, supra at

306; Donaldson v. Pillsbury, supra at 832-33.

4. Defendants in their brief cite Satterwhite v.

City of Greenville, 578 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1978) for the pro

position that the individual named plaintiffs had no continuing

interest in the litigation and did not have the necessary nexus

to the proposed class because their claims were adjudged merit

less. (Defendants Brief, p. 9). The facts which led to the

court's denial of class certification in Satterwhite are dis

tinguishable from this case. In Satterwhite the named plain

tiff had never been an employee although she complained of

specific employee oriented discriminatory employment practices

affecting numerous classes of employees, nor had she suffered

from the defendant employers' acts; and therefore did not re

tain a personal stake in the outcome of the litigation. Plain

tiffs here, are and were employees with a vested interest in

the outcome of the lawsuit; they will continue to be affected

by defendants' employment policies and procedures. Defendants'

simplistic conclusion that they had "no nexus" because their

-5-

claimshad been negatively determined totally ignores that

portion of Satterwhite which states that Long v. Sapp is still

good law:

"The lack of merit of representative's

claim is not determinative in and of itself

of the adequacy of his representation for

Rule 23 purposes. ... a plaintiff without a

viable claim may in appropriate circumstances,

act as a class representative, provided he or

she is a member of the class and maintains a

sufficient homogenity of interests ...." at 993.

As previously stressed, plaintiffs were denied a review of the

classwide evidence which would demonstrate that their claims

were homogenous with those of the class.

5. Defendants reliance on East Texas Motor Freight

Systems, Inc, v. Rodriquez, 97 S.Ct. 1891, 1986 (1977) is fac

tually misplaced. In that case the Supreme found that the

individual claims lacked merit and that the plaintiffs had

failed to appropriately request a certification hearing and

that the plaintiffs failed to present class issues.

In this action the Court considered the individual

claims only and did not consider evidence of classwide pattern

and practice discrimination, which plaintiffs here, contrary

to those in Rodriguez, definitively desired to have considered.

In addition, unlike plaintiffs in Rodriquez plaintiffs requested

a class certification hearing during which they would have pre

sented evidence of classwide discrimination which had affected

the individual named plaintiffs. See, e.g.. International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, supra; Franks v.

Bowman Transp. Co., supra; McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green.

supra.

-6-

6. As these factors point out and as plaintiffs

have discussed in their main brief and need not discuss to

the point of being redundant, whether or not a motion for

reconsideration had been filed was irrelevant to the outcome

of the determination due to the fact that it was the prac

tical unavailability of classwide evidence of discrimination

that precluded a complete finding on the individual claims

and not a premature technical pleading.

7. Defendants purport that Walker v. World Tile

Group, 563 F.2d 918, 921 (8th Cir. 1977) is comparable to

the instant lawsuit. First, it should be noted that other

circuits have taken a position contrary to Walker and held

that an erroneous failure to certify can be reviewed and

corrected by an appellate court; and that such review

"relates back" to the date on which the lower court failed

to certify the class. See, e.g., Lasky v. Quinlan, 558 F.2d

113, 1136-37 (2nd Cir. 1977); Zurak v. Regan, 550 F.2d 86,

91-92 (2nd Cir. 1977); Geraghty v. United States Parole

Commission, 579 F.2d 238, 245-254 (3rd Cir. 1978); Basil

v. Knebel, 551 F.2d 395, 397 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

It is our position that a careful reading of Walker,

where the appellate court in fact stated that it did not approve

of the lower court's convoluted certification procedure, reveals

-7-

that that case is inapplicable here. In Walker the plaintiff

was given an opportunity to present pattern and practice evi

dence but then did not prove that he was adversely affected by

the alleged discriminatory practices. The court specifically

determined that the case therefore was not controlled by

Donaldson v. Pillsbury, supra. As plaintiffs have previously

set forth, the remand order of the court of appeals required

the development of classwide discovery which had not been con

ducted or considered, and ordered that the named individuals

claims were to be determined in light of such evidence. The

distinction between the two cases is obvious.

We do however, rely on defendants reference to

Walker for another proposition which they omitted from their

discussion, which is that:

The District Court must have before it

"sufficient material ... to determine the

nature of the allegation and rule in com

pliance with the Rule's requirement. Blackie

v. Barrack, 524 F.2d 891, 901 (9th Cir. 1975)

cert, denied. 429 U.S. 816 (1976)," at 921.

8. Finally, defendants cite Phillips v. Klassen,

520 F .2d 362, 366 (D.D.C. Cir. 1974) in a futile attempt to

show that the named plaintiffs' claims are significantly

antagonistic to those of the class they represent. Rule 23(a)(4),

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, is uniformly interpreted as re

quiring a lack of antagonism between the representative and the

class, Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co., 508 F.2d 239 (3rd Cir.

1975), and freedom of conflict between the named plaintiffs'

interests and those of the class, V.J. Rockier & Co. v. Graphic

Enterprises, Inc., 52 F.R.D. 335 (D. Minn. 1971). The courts

-8-

have firmly held that antagonism between the plaintiffs 1

interests and those of the class which would defeat claims

of adequacy must go to the heart of the subject matter of the

discrimination. See Sperry Rand Corp. v. Larson, 554 F.2d

868 (8th Cir. 1977); Berman v. Narragansett Racing Assn.,

414 F.2d 311, 317 (1st Cir. 1969); and Arkansas Educ. Assn,

v. Bd. of Educ. of Portland, 446 F.2d 763, 767 (8th Cir.

1971. Defendants' assertions fail to meet this test.

Plaintiffs' interests in eliminating historic racially

discriminatory practices can in no way conflict with the in

terests of other, similarly-situated black persons. This is

not a case where there are unionized and non-unionized employees

which commonly involve conflicts of interest due to collective

bargaining agreements and must include the union as an addi

tional defendant. See, e.g., Wells v. Ramsey Scarlett and

Company, Inc., 506 F.2d 436 (5th Cir. 1975). The former status

of plaintiffs as past wage grade system employees and their

current status as general schedule employees does not indicate

any actualized antagonism between their interest and those of

other class members. See Leisner v. N.Y. Telephone Co., 358

F. Supp. 359 (S.D.N.Y. 1973).

Defendants suggest that the named individuals whom

they finally decided to promote subsequent to the institution

of the lawsuit cannot now adequately represent the class. To

accept their "timely decision" to promote the named individuals

as an action which removed the named plaintiffs from the class

would be inequitable and unjust. Such a procedure would permit

the defendant to deliberately preclude a class certification and

-9-

which would result in a denial of certification in the vast

majority of cases. See, e.g., Allen v. Likins, 517 F.2d 532

(8th Cir. 1975); Winokur v. Bell Federal Sav. & Loan Ass'n.,

560 F.2d 271, 274 (7th Cir. 1977). A recent court ruling

on the very issue presented here held that named plaintiffs

who were promoted to the positions they requested were still

adequate representatives. Williams v. City of New Orleans,

____ F. Supp. ____ 18 FEP 347 (E.D. La. January 14, 1978).

Furthermore, in actions challenging federal government agencies

which involve various job classifications, categories, posi

tions, and wage systems, the courts have not found the interests

of the groups to be antagonistic. Ellis v. Naval Air Newark

Facility, 404 F. Supp. 391 (N.D. Ca., 1975); Barrett v. United

States Civil Service Commission, 14 FEP Cases 1007 (D.D.C. 1977);

see also, White v. Nassau County Police Dept., 15 FEP Cases 266

(S.D.N.Y. 1977).

The requirement of adequacy of representation has also

been frequently treated as an adjunct of the requirement of

typicality. Rule 23(a)(2) and (3) require respectively that

there exist common question of fact or law and that the named

plaintiffs' claims be typical of those of class members. Most

employment discrimination decisions have viewed the two re

quirements as closely related, illegal discrimination being

both the common thread and the typical claim. The governing

law in this circuit was declared in the Fourth Circuit's decision

in Barnett v. W.T. Grant Co., 518 F.2d 543 (4th Cir. 1975).

There the Court of Appeals disapproved an unduly narrow class

certification limited to class claims factually similar to

those of the individual plaintiffs. It declared the approach

-10-

taken by the Fifth Circuit in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

417 F.2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969).

"more consonant with the broad remedial

purposes of Title VIT"

and held

"that the district court's less chari

table view, under which Barnett could

as a class representative challenge

only those specific actions taken by

the defendants toward him, would under

cut those purposes." Barnett, supra

518 F.2d at 548. (Emphasis in text).

The Fourth Circuit proceeded to declare itself in agreement with

the Fifth Circuit's more recent decision in Long v. Sapp, 502

F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1974) where that court reversed the refusal of

a district court to allow a plaintiff whose individual claim

involved discriminatory discharge to represent a class includ

ing rejected applicants.

Like the plaintiff in Long, Barnett

directed his attack at discriminatory

policies of defendants manifested in

in various actions, and as one who has

allegedly been aggrieved by some of

those actions he has demonstrated a

sufficient nexus to enable him to

represent others who have suffered

from different actions motivated by

the same policies." Barnett, supra

518 F .2d at 548.

In this case plaintiffs make an across the board attack

alleging that employment decisions at all steps of the employment

process have been left to the uncontrolled discretion of white

personnel. Historically such pervasive practices have been uni

formly held illegal by the Fourth Circuit as well as other Courts

of Appeals where they have an adverse impact on black employees.

Brown v. Gaston Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972),

-11-

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972); Rove v. General Motors

Corp.. 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972); Senter v. General Motors

Corp., 532 F.2d 511 (6th Cir. 1976); Baxter v. Savannah Sugar

Refining Corp., 495 F.2d 437, 442 (5th Cir. 1974). The basing

of employment decisions at all stages of employment on the un

fettered discretion of predominately white officials and

intermediate and higher supervisory personnel provides a nexus

which amply satisfies the commonality and typicality require

ments .

Plaintiffs reasoned opinion as based on the case

law is that the individual named plaintiffs are appropriate

class representatives. However, should there be any questions,

the courts have held that such doubts concerning the potential

conflicts should be resolved in favor of upholding the class.

See Chrapliwy v. Uniroval, Inc., ____ F. Supp. ___ , 7 FEP

Cases 343, 345 (N.D. Ind. 1974); and Sperry Rand Corp. v.

Larson, supra.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons presented in their Brief, Motion

for Summary Reversal and as set forth herein, plaintiffs

respectfully urge this Court to reverse the lower courts

order, and remand the case and in accordance with the original

-12-

remand order which required that a decision be made as to

whether a Rule 23 class action is maintainable; and for

reconsideration of the named plaintiff's individual claims

in light of classwide evidence.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

BILL LANN LEE

GAIL J. WRIGHT

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

HENRY L. MARSH, III

STEPHANIE J. VALENTINE

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

509 North Third Street

Post Office Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

-13-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 29th day of January,

1979, copies of the preceding Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-

Appellants were served on counsel for defendants-appellees

by depositing same in the United States mail, first class

postage prepaid, addressed as follows: Peter B. Lowenberg,

Esq., Department of the Navy, 1735 North Lynn Street,

Rosslyn, Virginia 22209.

- /

/ '

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the attached

Memorandum Amicus Curiae on the parties by depositing the same in

the United States mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed

as follows:

John H. Harwood, II

1666 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

John A. Terry

William D. Pease

Neil I. Levy

Assistant United States Attorneys

Room 3830

United States Courthouse

Washington, D.C. 20001

Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant

Dated: December , 1978.

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

11

70

CONCLUSION

In 1972 Congress was dissatisfied with the uncertain

and ineffective enforcement of guarantees against employment dis

crimination in federal departments and agencies.. Morton v.

Mancari, 417 U.S. 535, 546-47 (1974); Roger v. Ball, supra, at

704-06. As a result, Congress enacted 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 "to

make the courts the final tribunal for the resolution of contro

versies over charges of discrimination." Roger v. Ball, supra, 497

F. 2d at 70 6;. see also Alexander v . Gardner-Denver Co. , supra, at

60 n. 21. Proper resolution of the fundamental questions in this

appeal - the availability of class actions, access to discovery

of systemic discrimination, and the application of Title VII

law to federal agencies - will in large measure decide if

Title VII's broad pronouncement of rights is to become a

reality for federal employees.

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the court

below on the questions presented should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted

h e ;

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

STEPHANIE J. VALENTINE

HILL, TUCRER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

P. 0. Box 27363

Richmond, VA 23261

JACR GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVIN R. LEVENTHAL

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

C^c

— *