Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corporation Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corporation Brief for Appellant, 1970. cb65c6fe-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cba3b3e3-fa36-49ae-b8da-9cd3e2ae0fd6/lee-v-southern-home-sites-corporation-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

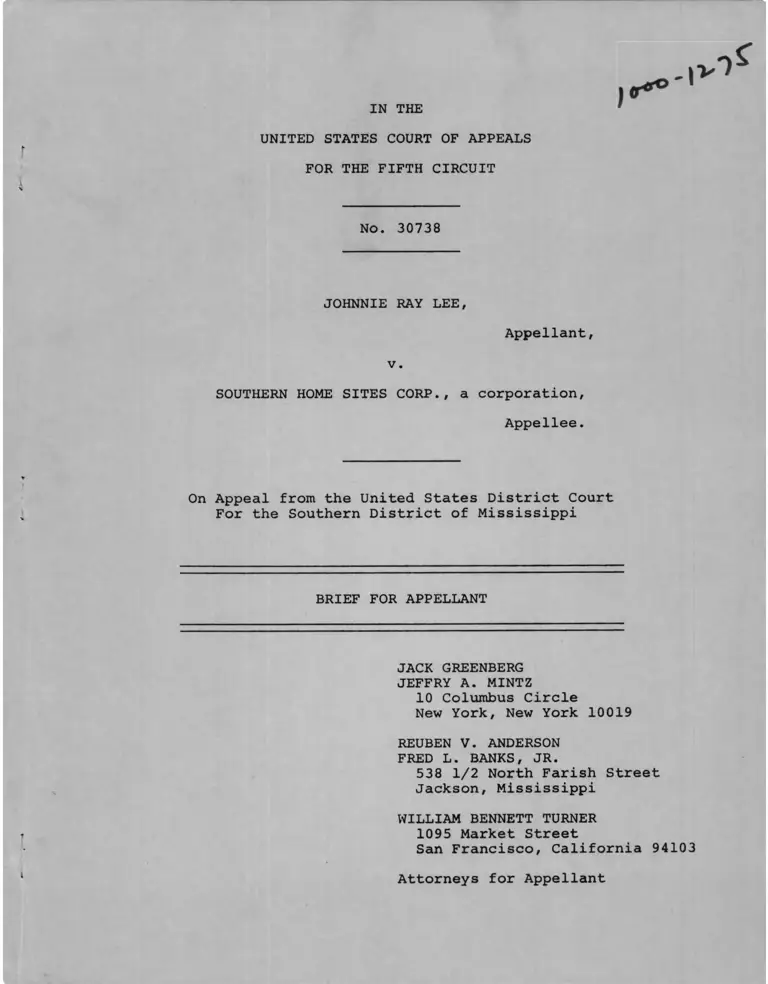

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30738

JOHNNIE RAY LEE,

Appellant,

v.

SOUTHERN HOME SITES CORP., a corporation,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

JACK GREENBERG

JEFFRY A. MINTZ

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS, JR.

538 1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

1095 Market Street San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

paa£

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES i l l

ISSUE PRESENTED

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

STATEMENT OF FACTS

ARGUMENT

II.

The History and the Purpose of Section

1982 Demonstrate that Attorneys' Fees

Should Be Awarded to Plaintiffs Who

Successfully Invoke Its Provisions.

The Explicit Provision for Attorneys'

Fees in the 1968 Fair Housing Act, A

Procedural Aspect of the Statute,

Should Be Applied to This Case. 22

CONCLUSIONS 28

l i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965) 17

Dolgow v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472, (E.D. N.Y. 1968) 22

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 391 F.2d

555 (2d Cir. 1968) 22

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Or. 139, 390 P.2d 320 (1964) 21

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill,

379 U.S. 306 (1964) 25

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) 26

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.,

400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968) 16

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409 (1968) 4,7,8,9,10,11,

12,13,17,18,23

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14

(8th Cir. 1965) 17

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp.,

429 F .2d 290 (5th Cir. 1970) 2,4,11

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.

426 F .2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970) 14,15,22,2$

Mills v. Electric Autolite Co.,

396 U.S. 375 (1970) 20,22

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F.Supp.

407; 1 Race Rel. L. Survey 185

(S.D. Ohio, 1968, 1969) 19

iii

Page

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400 (1968) 11,15,16,18,

20,24,25

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp.,

398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968) 16

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411 F.2d 998 (5th Cir. 1969) 16

Pina v. Homsi, 1 Race Rel. L. Survey 18

(D. Mass. July 10, 1969) 19

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R.R.,

186 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951) 21

Sanders v. Russell, 5th Cir. 1968,

401 F.2d 241 11

Smoot v. Fox, 353 F.2d 830

(6th Cir. 1965) 17

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank,

307 U.S. 161 (1939) 20

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc.,

396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969) 20,27

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery,

307 F.Supp. 369 (1969) 18,19

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the

City of Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969) 26

United States v. Price,

383 U.S. 787 (1966) 11

United States v. Schooner Peggy,

1 Cranch 103 (1801) 26

Vandenbark v. Owens Illinois Co.,

311 U.S. 538 (1941) 26

Page

Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 567 (1962) 20

Williams v. Kimbrough, 295 F.Supp. 578,

aff'd, 415 F.2d 875 (5th Cir. 1969),'

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1061 (1970) 17

Ziffrin, Inc. v. United States,

318 U.S. 73 (1943) 26

Brown v. City of Meridian, 356 F.2d 602

(5th Cir. 1966) 27

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

Civil Rights Act of 1866, Act of

April 7, 1866, c. 31, Section 1,

14 Stat. 27, re-enacted by

Section 18 of the Enforcement Act

of 1870, Act of May 31, 1870, c. 114,

Section 18, 16 Stat. 140, 144

codified in Sections 1977 and 1978

of the Revised Statutes of 1874. 9,10,11

18 U.S.C. Section 241 11

18 u. s. c. Section 242 11

42 U.S.C. Section 1981 2

42 U.S.C. Section 1982 1,2,7,8,9,11,

12,15,16,20,21,23

42 U.S.C. Section 1988 27

42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-2 25

42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-3(b) 8,14,25

42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-5(a) 15

42 U.S.C. Section 2000b et seq. 18

v

Page

42 U.S.C. Section 2000c et seq. 18

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(k) 8,25

42 U.S.C. Sections 3601 et seq. 26

42 U.S.C. Section 3603 23

42 U.S.C. Section 3604 (a) , (b) , (c) & (d) 22

42 U.S.C. Section 3612(b) 8

42 U.S.C. Section 3612(c) 18,24,25

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (b) (2) 2

Fed. R. Civ. P. 30(g), 37(a),

37(c) , 54 (d) and 56(g) 25

Fair Housing Act of 1968

Pub. L. 90-284; 82 Stat. 82 18, 23,24

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 474 10

114 Cong. Rec. S2308 24

Davidson & Turner, Fair Housing and

Federal Law, 1 ABA Human Rights

(1970)

36

15,23

Gulfport-Biloxi Daily Herald,

June 18, 1968, p. 1 12

Jackson Clarion-Ledger,

June 18, 1968, p. 1 12

Mobile Press, June 18, 1968, p. 3 12

Mobile Press Register,

June 23, 1968, p. 1 12

VI

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30738

JOHNNIE RAY LEE,

Appellant,

v.

SOUTHERN HOME SITES CORP., a corporation,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

ISSUE PRESENTED

Whether, in a class action under 42 U.S.C. Section

1982 brought by an individual acting as a "private attorney

general" to eliminate systematic racial discrimination

practiced by a real estate developer, the court should award

reasonable attorneys' fees to the prevailing plaintiff.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is the second appeal to this Court in the

instant case. On the prior appeal (No. 28167), this Court

remanded for findings of fact to justify the District Court's

denial of attorneys' fees. Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp.,

429 F .2d 290 (5th Cir. 1970).

This case was brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. Sections

1981 and 1982 and the Thirteenth Amendment to challenge

systematic racial discrimination practiced by appellee Southern

Home Sites Corp., a real estate developer. The action was

brought by appellant Johnnie Ray Lee on his own behalf and,

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(2), as a class action on

behalf of similarly situated black citizens who were

discriminated against by Southern Home Sites. The complaint

1/(1.4-9) alleged that appellant had been excluded from buying

a lot in the Southern Home Sites resort development because

of his race, and that appellee's refusal to deal with appellant

was pursuant to a widespread policy and practice of

discrimination against black citizens. Plaintiff-appellant

1/ Numbered references preceded by "I" are to pages of the

printed Appendix on the prior appeal, No. 28,167.

References preceded by "II" are to pages of the printed

Appendix on the present appeal, No. 30,738. On Nov. 4,

1970, this Court granted appellant's motion to limit the

reproduction of the record on this appeal to documents

filed since the printing of the Appendix on the prior

appeal. Additional copies of the prior Appendix have

been filed with the Court together with copies of the

present Appendix.

-2-

sought injunctive relief, a declaratory judgment, compensatory

and punitive damages and counsel fees.

The case was tried without a jury on March 18, 1969.

On April 7, 1969, the court below (Nixon, J.) rendered an

opinion (1.42-45) finding that Southern Home Sites had engaged

in racially discriminatory conduct in violation of 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982. On May 14, 1969, the District Court entered

judgment (1.54-56) generally enjoining appellee from

discriminating against black people seeking to purchase lots

in appellee's development, directing Southern Home Sites to

offer appellant Lee a lot and defining the class on whose

behalf the action was maintained. The judgment denied

appellant's claims for money damages and counsel fees. The

court below retained jurisdiction until the judgment would

be fully complied with.

Appellant then sought an order requiring Southern

Home Sites to notify members of the class of their rights

under the court's judgment and to offer lots to members of

the class on the same terms as lots were to be offered to

appellant and as lots had been conveyed to white persons

(1.60-64). On August 6, 1969, the court below denied this

relief. Appellant then appealed to this Court from the

judgment of May 14, 1969, and the order of August 6, 1969.

-3-

On July 13, 1970, this Court (Coleman, Goldberg

and Morgan, JJ.) upheld the District Court's denial of money

damages but remanded with instructions to require Southern

Home Sites to notify class members of their rights under the

judgment, including their right to purchase lots on the same

terms as appellant. This Court also directed the District

Court to make findings of fact "sufficient to enable this

court to review the denial of attorneys' fees." Lee v.

Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d 296 (5th Cir. 1970).

On July 20, 1970, the court below ordered the clerk

of the court to publish notices in two Mississippi newspapers

informing class members of their rights under the judgment

(11.5-6). On August 11, 1970, the court below made findings

of fact regarding its denial of attorneys' fees (II.6-9).

The court found that appellant had failed to prove that

Southern Home Sites had knowledge or notice of the Supreme

Court's decision in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968) and that, therefore, appellee's discriminatory

conduct was not "malicious, oppressive or so 'unreasonable

and obdurately obstinate' as to warrant an award for attorneys'

fees" (II.8). The District Court thereupon entered a

supplemental decree (August 13, 1970) denying an award of

attorneys' fees (II.9). This appeal followed.

-4-

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Appellant Johnnie Ray Lee is a black citizen who

resides in Columbia, Mississippi. Appellee Southern Home

Sites Corp. is a Mississippi corporation which is in the

business of developing resort areas and selling lots or

interests in real estate (1.6,17). It owns and operates a

development called Ocean Beach Estates, located near Ocean

Springs and Pascagoula, Mississippi (Id.).

The development at Ocean Beach Estates contains a

total of 1,653 lots (1.27,33,43). As of the time of trial,

1,206 of the lots had been sold (Id.). Thus, more than 400

lots remained available (1.96-97). At that time, appellee

was holding lots off the market, because developments on

adjacent property were causing Southern Home Sites lots to

increase in value (1.114,43).

On July 30, 1968, appellee sent a form letter to

appellant offering him a lot stated to be worth $600 for

$49.50 in cash (1.6,17,42). In 1968 alone, Southern Home

Sites sent probably more than a thousand such letters to

persons throughout the State of Mississippi and outside

Mississippi (1.86-87). The letters were sent as a promotional

venture, with the idea that persons sold lots at bargain

prices would tell their friends and thus increase appellee's

-5-

sales (1.113,43). At the time of trial, Southern Home Sites

had conveyed 119 lots on the $49.50 terms set forth in the

letter to appellant (1.93,25,31-32,27,33).

Appellee's agents collected names for the promotional

mailing list at boat shows, county fairs, etc. (1.87,32). In

mailing the letters containing the promotional offers, appellee

made no effort whatever to ascertain the race of persons to

whom the letters were sent (1.26,32). Thus, thousands of

letters were sent indiscriminately to both black and white

persons.

The letters sent to citizens throughout the area

stated baldly that in order for the recipient to take advantage

of the offer, "you must be a member of the white race" (1.42,

6,17). Although Southern Home Sites pretended to justify this

condition on the ground that "only the white race" would help

appellee advertise its development (1.32), white purchasers

of lots pursuant to the promotional scheme were never asked

to advertise and no such condition was ever demanded by

Southern Home Sites (1.104-105,108).

Shortly after receiving his letter from appellee,

Johnnie Ray Lee traveled to appellee's office at Ocean Springs

(1.42-43,6-7,12,13-14,18). He took with him the letter and

$50 in cash and was ready, willing and able to purchase a lot

-6-

on the terms set forth in the letter, except for the racial

limitation (1.43,74,76). However, at the Southern Home Sites

office he was bluntly told by appellee's agent that the

development "wasn't for Negroes," and the agent refused to

j o business with him (1.75,82,43). At Ocean Beach Estates,

black people were not permitted to buy lots (1.26,33). Not

only was Ocean Beach Estates maintained as a lily-white

preserve, but appellee planned a separate, all-black

development, and kept a waiting list of black applicants for

that development (1.75,76,82; Plaintiff's Exhs. 2 and 3).

On October 15, 1968, appellant Lee brought this

class action in the court below. He obtained a broad

injunction prohibiting Southern Home Sites from discriminating

against black citizens on the ground of race. The action was

based primarily on 42 U.S.C. Section 1982, which was interpreted

by the Supreme Court to bar all racial discrimination in the

sale of real estate. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968). The letter to appellant Lee was sent by Southern

Home Sites about six weeks after the Jones decision, and

appellant was excluded from the resort development about two

months after the decision. At trial, appellant made no attempt

to show that Southern Home Sites had actual knowledge of the

Jones decision at the time of its discriminatory conduct; nor

did the developer seek to show its ignorance of the decision.

-7-

On August 11, 1970, the District Court found as a fact that

because of appellant's failure to prove appellee's knowledge

or notice of Jones, appellee's conduct was not "malicious,

oppressive or so 'unreasonable and obdurately obstinate' as

to warrant an award for attorneys' fees" (II.8). Appellant

here maintains that the denial of attorneys' fees was

erroneous as a matter of law.

ARGUMENT

I. The History and the Purpose of Section 1982 Demonstrate

That Attorneys' Fees Should Be Awarded to Plaintiffs

Who Successfully Invoke Its Provisions.

Unlike many of the recent statutes authorizing

2/

private suits to vindicate denials of equal rights, 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982 does not expressly authorize the granting of

attorneys' fees to successful plaintiffs. An analysis of the

history and purpose of Section 1982 readily demonstrates,

however, that the allowance of attorneys' fees to successful

plaintiffs invoking its provisions is a proper means of

3/

"fashioning an effective equitable remedy" for its enforcement

2/ See 42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-3(b) (public accommodations);

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5(k) (equal employment); 42 U.S.C.

Section 3612(b) (fair housing).

3/ Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 414, n.13 (1968)

-8-

Section 1982 is derived from Section 1 of the Civil

4/

Rights Act of 1866. The history and meaning of the statute

are discussed at length in the opinion of the Supreme Court

in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 420-444 (1968).

There, the Court held that (1) the statute was intended to bar

all racial discrimination, private as well as public, in the

sale or rental of property, and (2) as thus construed, it was

a valid exercise of the power of Congress to enforce the

5/

Thirteenth Amendment.

£/As originally enacted, the Civil Rights Act of 1866

was to be enforced primarily through criminal prosecutions

brought by federal district attorneys against persons who

violated its provisions. The sponsors of the bill feared that

permitting only a private right of action would be insufficient

to eradicate either the racial wrongs being perpetrated or the

4/ Act of April 7, 1866, c. 31, Section 1, 14 Stat. 27,

re-enacted by Section 18 of the Enforcement Act of 1870,

Act of May 31, 1870, c. 114, Section 18, 16 Stat. 140, 144,

codified in Sections 1977 and 1978 of the Revised Statutes

of 1874.

5/ It was the Jones decision which led the District Court to

hold on the merits that Southern Home Sites' discrimination

violated Section 1982 and to issue the injunction barring

future discrimination and ordering the sale of a lot to

Lee (1.44).

6/ See n.4, supra.

-9-

temper which gave rise to and sustained them. They expressed

particular concern about the likelihood that those persons

whom the Act sought to protect could not bear the expense of

enforcing their rights if they were not assisted by the

8/

federal attorneys.

In the intervening reenactments of the Act of 1866,

the penal provisions which originally accompanied it have been

V

7/ Introducing the bill on January 5, 1866, Senator Trumbull

stated its objective was to give effect to the declaration

contained in the Thirteenth Amendment and to secure to all

persons within the United States practical freedom. "There

is very little importance in the general declaration of

abstract truths and principles unless they can be carried

into effect, unless the persons who are to be affected by

them have some means of availing themselves of their

benefits." Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 474, quoted

in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, at 431-32.

8/ /James Wilson, who introduced the bill into the House,

expressed in greater detail the legislative intention as

he responded to Ohio Congressman Bingham's motion to

recommit and to "strike out all parts of the bill which

are penal and authorize criminal proceedings and in lieu

thereof to give injured citizens a civil action in the

United States Courts..." Id. at 1293. Between the two,

Mr. Wilson said, "There is no difference in the principle

involved...There is a difference in regard to the expense

of protection. There is also a difference as to the

effectiveness of the two modes...This bill proposes that

the humblest citizen shall have full and ample protection

at the cost of the Government, whose duty it is to protect

him. The Amendment of the gentleman recognizes the principle

involved, but it says that the citizen despoiled of his

rights... must press his own way through the courts and pay

the costs attendant thereon. This may do for the rich, but

to the poor, who need protection, it is mockery. . . " Ici. at

1295 (emphasis added).

-10-

separated or eliminated, so that today Section 1982 is

"enforceable only by private parties acting on their own

initiative." Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, at 417.

However, as the Court noted in Jones, "The fact that 42 U.S.C.

Section 1982 is couched in declaratory terms and provides no

explicit method of enforcement does not, of course, prevent

a federal court from fashioning an effective equitable remedy."

Id. at 414, n.13. And as this Court stated in its previous

opinion in the instant case:

"In the area of civil rights, many cases have

either allowed or implicitly recognized the

discretionary power of a district judge to

award attorneys 1 fees in a proper case in

the absence of express statutory provision

icitations omitted] and especially so when

one considers that much of the elimination

of unlawful racial discrimination necessarily

devolves upon private litigants and their

attorneys, cf. Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968),

and the general problems of representation in

civil rights cases. See Sanders v. Russell,

5th Cir. 1968, 401 F.2d 241." Lee v. Southern

Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d 290, 295 (5th Cir.

1970). * 18

9/

9/ The only remaining criminal statute derived from the Act

is 18 U.S.C. Section 242. See United States v. Price,

383 U.S. 787, 801-02 (1966). While Section 242 is limited

to actions taken "under color of law," it may well be that

18 U.S.C. Section 241, derived from the Enforcement Act of

1870 (the reenactment of Section 1982, see n.4, supra)

would permit criminal prosecutions against persons who

conspire to interfere with the rights guaranteed by

Section 1982.

-11-

In Jones, the Supreme Court resurrected Section 1982

and held that it operated as a fair housing statute to outlaw

10/

all racial discrimination in the sale of real property.

We submit that the effectiveness of Section 1982 as a guarantee

of equal housing opportunity would be vastly diminished by

limiting the availability of attorneys' fees under the standard

followed by the court below. The District Court here denied

fees on the around that appellant failed to prove that Southern

Home Sites had actual knowledge or notice of the Supreme

Court's decision in Jones and that, accordingly, appellee's

discriminatory conduct was not "malicious, oppressive or so

'unreasonable and obdurately obstinate' as to warrant an award

11/for attorneys' fees" (1.8) . The District Court did not

10/ The Court noted and agreed with the statement of the

Attorney General at oral argument: "The fact that the

statute lay partially dormant for many years cannot be

held to diminish its force today." 392 U.S. at 437.

11/ The court went further to find that in the absence of

such proof, Southern Home Sites did not in fact have

notice of the Jones decision (II. 7). This inference is

without any evidentiary support whatever and is clearly

erroneous. It might be noted that the Jones decision

made headlines in every newspaper in the South. See,

e.g., the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, June 18, 1968, p. 1;

the Gulfport-Biloxi Daily Herald, June 18, 1968, p. 1?

the Mobile Press, June 18, 1968, p. 3; the Mobile Press

Register, June 23, 1968, p. 1. It seems exceedingly

unlikely that a large real estate developer like Southern

Home Sites would remain wholly ignorant of a landmark

decision directly affecting its business. In any event,

as will be demonstrated below, an award of attorneys fees

cannot be conditioned on proof that the defendant actually

knew the law condemning its racially discriminatory practices.

-12-

mention the facts that (1) six weeks after the Jones decision,

Southern Home Sites distributed thousands of racially insulting

letters, with no attempt whatever to determine the race of

addressees and thus with callous disregard for the feelings

of black recipients; (2) appellee's policy was not only to

keep Ocean Beach Estates a lily-white preserve, but it planned

a wholly segregated all-black development; and (3) appellee's

defense in the trial court was frivolous— appellee contended

that the promotional offers were for a "gift" and that under

Mississippi law the donor had complete discretion to select

his donees (1.32-34,37; defendant's response to motion for

12/summary judgment).

The reason for the District Court's denial of

counsel fees — that appellee did not "know" of the Jones

decision— might be appropriate if the question were whether

to impose punitive damages and if some showing of willful or

malicious conduct were required. But here we are dealing with

whether counsel fees may be awarded, and the District Court's

approach seems wholly inappropriate. Indeed, the approach of

12/ Appellant proved at trial that the transactions could in

no way be considered "gifts." Recipients of promotional

offers were required to pay $49.50 in cash to obtain a

lot (1.93,25,31-32,27,33). All 119 of these transactions

were accounted for on Southern Home Sites' books in

exactly the same manner as all cash purchases of lots

(1.94-95,118). Appellee introduced no evidence of

donative intent.

-13-

the court below has already been rejected by this Court in

the analogous case of Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970). In Miller, the district court

had denied attorneys1 fees to a successful plaintiff in a suit

challenging racial discrimination under Title II of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. The reason for the denial was that at

the time of the discriminatory act (and, indeed, even up to

and after the decision of a panel of this Court), the defendant

company was not deemed in violation of the law; not until the

en banc decision of this Court was the defendant held to be

covered by Title II. This Court reversed the denial of fees,

stating that the defendant

". . .became subject to the prescribed

judicial relief not because the Court said

so, but rather because the Court said--even

perhaps for the very first time— that the

Congress said so." 426 F.2d at 536.

The Court also ruled that the defendant's subjective "good

faith" was not to be considered as a justification for denying

counsel fees. Even though the defendant in Miller, unlike

appellee here, advanced no frivolous defenses, and even though

several judges agreed with its position, this Court directed

an award of attorneys' fees.

To be sure, Miller involved a statute containing an

express provision for attorneys' fees. See 42 U.S.C. Section

2000a-3 (b) (fees may be granted in the "discretion" of the

-14-

court). But this Court's reasoning applies equally to

Section 1982:

"Congress did not intend that vindication of

statutorily guaranteed rights would depend

on the rare likelihood of economic resources

in the private party (or class members) or

the availability of legal assistance from

charity--individual, collective or organized.

An enactment aimed at legislatively enhancing

human rights and the dignity of man through

equality of treatment would hardly be served

by compelling victims to seek out charitable

help." 426 F.2d at 539.

Miller relied on the Supreme Court's decision in Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968). In

Piggie Park, the Court noted that since the statute, like

Section 1982, provides no administrative agency or criminal

prosecutions to enforce its mandate, its effectiveness depends

13/

on the ability of private litigants to maintain civil suits.

Said the Court:

"If [the plaintiff] obtains an injunction,

he does so not for himself alone but also

as a "private attorney general," vindicating

a policy that Congress considered of the

highest priority. If successful plaintiffs

were routinely forced to bear their own

attorneys' fees, few aggrieved parties would

be in a position to advance the public

interest by invoking the injunctive powers

of the federal courts." 390 U.S. at 402

(footnote omitted).

13/ The Attorney General of the United States is empowered to

bring suit to enforce Title II. See 42 U.S.C. Section

2000a-5(a). But Section 1982 has no such provision and

its enforcement depends wholly on private civil actions.

See generally, on the need for counsel fee awards to

enforce fair housing statutes, Davidson and Turner, Fair

Housing and Federal Law, 1 ABA Human Rights 36, 49-50 T1970).

-15-

This Court has subsequently applied the "private attorney

general" doctrine not only in Mi Her but also in cases arising

under the fair employment provisions of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. See Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411

F.2d 998, 1005 (5th Cir. 1969); Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.,

400 F .2d 28, 32-33 (5th Cir. 1968); Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach

Corp., 398 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968).

The teaching of Piggie Park and its progeny is that

counsel fees should be awarded to the successful plaintiff

unless "special circumstances render such an award unjust."

390 U.S. at 402. It is irrelevant whether the defenses

advanced by the discriminating party were frivolous or

plausible. And it is perfectly clear under Miller that the

test cannot be whether the defendant had actual knowledge of

the law.

The fact that Section 1982, unlike more recently

14/

enacted civil rights statutes, does not explicitly provide

for attorneys' fees should not justify deviation from the

Piggie Park standard. First, as demonstrated above, Congress

originally provided that the enforcement of the rights

guaranteed by Section 1982 should be undertaken by government

attorneys for the very reason that the persons aggrieved could

14/ See n.2, supra.

-16-

Nothing in the subsequentnot bear the cost of litigation.

revisions which have made those rights "enforceable only by

16/

private parties acting on their own initiative" indicates

that Congress intended to limit their availability to those

few who could bear the cost of litigation. The allowance of

attorneys 1 fees under the Piggie Park standard clearly would

serve Lo fulfill the legislative intent and to effectuate

the Congressional policy expressed in Section 1982.

Second, the cases relied on by the District Court

to support its standard of requiring "unreasonable, obdurate

17/

obstinacy" by a defendant before attorneys’ fees can be

allowed were all in the context of school desegregation suits,

where the plaintiffs sought to enforce rights which were

judicially declared and which were not an explicit statutory

15/

15/ See nn. 6 and 7 and accompanying text, supra.

16/ Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, at 417.

17/ Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345 F .2d

310, 321 (4th Cir. 1965); cf. Id. at 324-5 (Sobeloff and

Bell, JJ. dissenting); Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F .2d 14 (8th

Cir. 1965); Williams v. Kimbrough, 295 F.Supp. 578, 587,

aff'd, 415 F.2d 875 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396

U.S. 1061 (1970). Smoot v. Fox, 353 F.2d 830 (6th Cir.

1965), also cited by the District Court, was a common

law libel action and is in no way relevant to this case.

-17-

18/

"policy that Congress considered of the highest priority."

Moreover, the defendant here is a profit-making corporation

engaged in racial discrimination as part of its business, not

a school board composed of unpaid public servants. Whatever

may be the policy for denying counsel fees in school cases,

the policy does not apply here. Indeed, the explicit 19/

provision for counsel fees in the Fair Housing Act of 1968#

establishes a Congressional policy strongly favoring counsel

fee awards in housing discrimination cases.

Other district courts granting injunctive relief

in suits under Section 1982 have awarded attorneys' fees. In

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, 307 F.Supp. 369 (1969), suit was

brought to compel the defendant cemetery to sell a burial plot

to a black mother for the grave of her son, who was killed in

action in Viet Nam. The cemetery refused to sell the plot

18/ Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, supra, at 402. See

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 474, quoted in Jones

v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., supra, at 431-32. Also, Congress

has now authorized the Attorney General to file suits on

behalf of the United States to desegregate schools. See

Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000c et. seq. See also Title III, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000b ejt seq. , authorizing the Attorney General

to sue to challenge discriminatory practices in state

owned or operated facilities. Much of the cost of

litigation to desegregate schools is thus borne by the

federal government.

19/ 42 U.S.C. Section 3612(c).

-18-

solely because of the race of the deceased. Chief Judge Lynne

carefully analyzed the Jones decision and the lower court

cases which followed it and held that the refusal to sell the

burial plot was a violation of Section 1982. In the final

judgment (which followed the reported opinion), attorneys'

20/

fees in the amount of $2500 were awarded.

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F.Supp. 407;

1 Race Re1. L. Survey 185 (S.D. Ohio, 1968, 1969), which was

relied upon in Terry, is very similar to the instant case in

that it involved a large real estate development from which

blacks were excluded. The case was brought as a class action

by an individual who had been refused a lot in the development.

The court defined the class as "members of the Negro race" who

had been similarly excluded, Id., at 417, the same delimitation

of the class made by the lower court in this case (1.49). By

a supplemental order, the court in Newbern awarded attorneys

21/

fees in the amount of $1000 . Also, in Pina v. Homsi, 1 Race

Rel. L. Survey 18 (D. Mass. July 10, 1969), the plaintiffs were

20/ Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, N.D. Ala. Civ. No. 69-490,

order of January 29, 1970. Terry is a particularly

significant case in this regard as the property there

involved is not covered by the provisions of the 1968

Fair Housing Act and suit, even today, could be

maintained only under the provisions of Section 1982.

21/ Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 1 Race Rel. L. Survey 185

(S.D. Ohio, March 12, 1969).

-19-

refused an apartment because the husband was black. Under

Section 1982, the court awarded compensatory damages and

attorneys' fees.

These cases under Section 1982 follow the well

established principle that federal courts have equitable power

to award counsel fees in appropriate cases even in the absence

of statutory authorization. See Mills v. Electric Autolite Co.,

396 U.S. 375 (1970); Vaughn v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 567 (1962);

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161 (1939); Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., supra, 390 U.S. at 402, n.4.

The instant case presents special reasons supporting an award

of counsel fees:

(1) Section 1982 expresses a national policy of

the highest priority — the eradication of racial discrimination

in housing. Therefore, appellant acts here as a "private

attorney general" in vindicating the statutory right to equal

housing opportunity. Cf. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., supra, 390 U.S. at 402. And as the Supreme Court said

of Section 1982, "The existence of a statutory right implies

the existence of all necessary and appropriate remedies."

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969). 2

(2) The discrimination involved here was systematic

and deliberate; it was not isolated or accidental. Appellant

Lee challenged not only the refusal to sell him a lot but also

-20-

the policy of (a) distributing offers addressed to the general

public but acceptable only by "a member of the white race,"

and (b) creating a wholly segregated all-black development.

This kind of action ought to be encouraged by an award of

counsel fees under Section 1982, so that neither aggrieved

parties nor their attorneys need subsidize from their own

pockets the essentially public activity of correcting

22/

systematic racial discrimination.

(3) This is a class action on behalf of all blacks

discriminated against by Southern Home Sites. If the action

had not been brought, the rights of class members would never

have been vindicated, because their claims are too small to * * * * * * * *

22/ Awarding counsel fees to encourage "public" litigation

by private parties is an accepted device. For example,

in Oregon, union members who succeed in suing union

officers guilty of wrongdoing are entitled to counsel

fees both at the trial level and on appeal, because they

are protecting an interest of the general public:

If those who wish to preserve the internal

democracy of the union are required to pay

out of their own pockets the cost of employing

counsel, they are not apt to take legal action

to correct the abuse. . . . The allowance ofattorneys1 fees both in the trial court and

on appeal will tend to encourage union members

to bring into court their complaints of union

mis-management and thus the public interest as

well as the interest of the union will be

served.

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Or. 139,

390 P.2d 320 (1964). See also Rolax v. Atlantic Coast

Line R.R., 186 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1951).

-21-

justify individual litigation. Cf. Eisen v. Carlisle &

Jacquelin, 391 F.2d 555, 560 (2d Cir. 1968); Dolgow v.

Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472, 484-87 (E.D. N.Y. 1968). And since

individual suits would not have been brought, the statute

outlawing appellee's conduct would have gone unenforced. As

the Supreme Court said in granting fees in Mills v. Electric

Autolite Co., supra, "private. . .actions of this sort. . .

furnish a benefit to all. . .by providing an important means

of enforcement of the. . .statute." 396 U.S. at 396.

Therefore, it was error for the court below to

withhold counsel fees on the ground that appellee was not

on notice of the Jones decision and did not act maliciously

or obstinately. The case should be remanded with instructions

to award reasonable attorneys 1 fees covering all proceedings

in the District Court and on both appeals. See Miller v.

Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534, 539 (5th Cir. 1970). II.

II. The Explicit Provision For Attorneys' Fees In The 1968

Fair Housing Act, A Procedural Aspect of the Statute, Should Be Applied to This Case.

The discriminatory acts of Southern Home Sites

would clearly have been covered by specific provisions of the

Fair Housing Act of 1968 had they taken place after

December 31, 1968. See 42 U.S.C. Section 3604 (a), (b), (c) and

(d). Because they occurred during 1968 and related to housing

-22-

substantive prohibitions of the Act did not cover them.

Appellant Lee was thus compelled, in this action filed

October 15, 1968, to base his substantive claim that the acts

were illegal on Section 1982. But invoking the procedural

and remedial provisions of the 1968 Act would not run counter

to Congressional intention. Indeed, the legislative history

of the Act indicates that Congress had in mind as one of its

purposes the effectuation of Section 1982:

[T]he Senate Subcommittee on Housing and

Urban Affairs was informed in hearings held

after the Court of Appeals had rendered its

decision in the case that Section 1982 might

well be "a presently valid federal statutory

ban against discrimination by private persons

in the sale or lease of real property." The

Subcommittee was told, however, that even if

this Court should so construe Section 1982,

the existence of that statute would not

"eliminate the need for congressional action"

to spell out "responsibility on the part of

the federal government to enforce the rights

it protects." The point was made that, in

light of the many difficulties confronted by

private litigants seeking to enforce such

rights on their own, legislation is needed

to establish federal machinery for enforcement

of the rights guaranteed under Section 1982...."

quoted in Jones v. Alfred H, Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

at 415-16 (emphasis added; footnotes omitted).

not owned or financed by the federal government, the

23/

23/ 42 U.S.C. Section 3603. The substantive prohibitions

covered only housing owned or financed by the federal

government during 1968. Id. It might be noted that the

1968 Act even now covers only "dwellings" and does not cover

personal, commercial, or industrial property. Of course,

Section 1982 covers all property. Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer

Co., 392 U.S. 409, 413 (1968); see generally, on the coverage

of the respective statutes, Davidson and Turner, Fair Housing

and Federal Law, 1 ABA Human Rights 36 (1970).

-23-

Thus, it seems entirely appropriate to apply the "machinery"

of the Fair Housing Act--in this context, its provision for

attorneys' fees--to assist in the enforcement of the Section

1982 rights which were violated here.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act explicitly provides for

the allowance of "reasonable attorney fees in the case of a

prevailing plaintiff" suing under its provisions. 42 U.S.C.

24/Section 3612(c). Since attorneys' fees are universally

24/ The provision is phrased in stronger language than the

analogous provision in Title II of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, which authorizes attorneys' fees in the

"discretion" of the court. The Title II provision has

been interpreted to mean that fees must be awarded in

virtually every successful case. Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968). Thus the Fair

Housing Act should be interpreted to confer a right to

recover fees, except where the plaintiff is wealthy

enough to afford easily the expense of litigation.

Also, the legislative history indicates that successful

plaintiffs who are not even obligated to pay their

lawyers— for example, persons represented by legal

services offices or private legal associations— are entitled to recover fees, on the Piggie Park theory that

"private attorneys general" play an important role in

vindicating constitutional rights. See remarks of

Senator Hart (floor manager of the bill), 114 Cong. Rec.

S2308 (daily ed. March 6, 1968).

-24-

we submit that thisconsidered a procedural matter,

provision of the Act should be applied to the instant case.

This type of application of new Congressional policy

to prior conduct in the civil rights field was seen in Hamm v.

City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964), where the Court held

26/

that the statutory prohibition of interference with equal

access to public accommodations abated all pending criminal

prosecutions of persons who had sought such access prior to

the passage of the Act. Here, an appreciably less significant

retrospective application is sought, since the Fair Housing

25/

25/ Rules governing the retrospective application of the

substantive portions of a statute need not be discussed

here. Provisions for attorneys' fees are without a doubt

procedural. In the cases and statutes pertinent hereto,

counsel fees are awarded as part of the costs. Provisions

which govern their allowance are found in the procedural

sections of the Fair Housing and other Civil Rights Acts.

42 U.S.C. Section 3612(c); 42 U.S.C. Section 2000a-3(b);

42 U.S.C. Section 2000e-5 (k) .

In Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400,

403 (1968), the Supreme Court ordered the district court

on remand to "include reasonable counsel fees as part of

the costs to be assessed against the respondents." This

Court in Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d

534, 539 (5th Cir. 1970), recognized that "The Newman

rule. . .calls for the allowance of attorney fees as part

of the costs." (emphasis added)

See also Rules 30 (g) , 37 (a), 37 (c) , 54 (d) and 56 (g) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. All refer to attorneys'

fees as an element of costs or expenses.

26/ Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2000a-2.

-25-

Act was enacted well before Southern Home Sites engaged in

27/its discriminatory conduct and the conduct was in any event

illegal under Section 1982.

Also relevant is the principle of Thorpe v. Housing

Authority of the City of Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969), that

when there is a change in the law while a case is pending in

the courts, the court should generally apply the law in effect

28/

at the time of its decision. Here, the 1968 law was fully

applicable prior to the first judicial opinion in this case

(the District Court's opinion of April 7, 1969), and it

seems quite proper to apply its procedural devices here.

Finally, the Supreme Court has recently said of

Section 1982 and the Fair Housing Act that "the 1866 Civil

Rights Act considered in Jones should be read together with

the later statute on the same subject. . . . " Hunter v.

29/

Erickson, 393 U.S. 385, 388 (1969). Moreover, there is

27/ The law was enacted on April 11, 1968, Pub. L. 90-284;

82 Stat. 82; 42 U.S.C. Sections 3601 et_ seq.

28/ See also, United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103,

110 (1801); Vandenbark v. Owens Illinois Co., 311 U.S.

538 (1941); Ziffrin, Inc. v. United States, 318 U.S. 73

(1943).

29/ The Court was there discussing whether the earlier lawshould be read so as to incorporate the provision of the

1968 statute preserving local fair housing laws, and held

that it should.

-26-

the mandate of 42 U.S.C. Section 1988, requiring that the

federal courts, in proceedings to protect and enforce civil

rights, be guided not only by the particular statute in

question; the courts are directed also to draw from other laws

to assure effective remedies for the wrongs involved. The

Supreme Court has invoked this provision specifically to

supply appropriate remedies under Section 1982. See Sullivan

v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 239 (1969). And

this Court has said of Section 1988 that "In civil rights

cases, federal courts should use that combination of federal

law, common law and state law as will be best adapted to the

object of the civil rights laws. . ." Brown v. City of

Meridian, 356 F.2d 602, 605 (5th Cir. 1966). Therefore, the

1968 Fair Housing Act should be read harmoniously with Section

1982 to provide a single set of effective remedies under these

statutes, and the attorneys' fees provision of the 1968 Act

should be applied in this case.

-27-

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the case should be remanded

to the District Court with instructions to award reasonable

attorneys' fees covering all proceedings in that court and

on both appeals of this case.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JEFFRY A. MINTZ

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

REUBEN V . ANDERSON

FRED L. BANKS, JR.538 1/2 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

1095 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Attorneys for Appellant

-28-

II

The District Court Erred In Dismissing These Cases

Without Finding That the School Districts Had Eliminated All

Vestiges of Their Racially Dual and Unequal School Systems

These cases were dismissed without any finding that the

school districts had achieved and maintained unitary status. The

district court did not state that the school districts had

achieved "unitary status," nor did it state that the districts

had eliminated all the vestiges of their racially dual and

unequal school systems. The district court's opinions provide

only, with respect to Etowah County and Sylacauga City, that they

"operated a unitary system over the past several years" (R2-25-

8; R3-24-12); the courc is completely silent on this issue with

respect to Talladega City. (R4-26.)

In Georgia State Conference of Branches of NAACP v. Georgia.

775 F.2d 1403 (11th Cir. 1985), this Court recognized the

confusion over the meaning of the terms "unitary" and "unitary

status." The Court explained the difference in a footnote:

Some confusion has been generated by the failure to

adequately distinguish the definition of a "unitary"

school system from that of a school district which has

achieved "unitary status." As used in this opinion, a

unitary school system is one which has not operated

segregated schools as proscribed by cases such as Swann

and Green for a period of several years. A school

system which has achieved unitary status is one which

is not only unitary but has eliminated the vestiges of

its prior discrimination and has been adjudicated as

such through the proper judicial procedures.

Unfortunately, the terminology used to refer to these

concepts is not universal. See. e". a . . Castaneda Tv.

Pickard! . 648 F.2d [989,] at 996-97 [(5th Cir.

1981)](referring to a school district which does not

25

operate a dual system as having achieved "unitary

status").

Id. at 1413 n.12.33

The district court embraced these definitions in its

opinions in each of these cases by specifically "adopt[ing] and

reiterat [ ing]" the rationale of its opinion in Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education (Nunnelley State Technical College).

681 F. Supp. 730, where the court stated:

"Unitary status" is a term of nouveau art. The fact

that a school district or institution has ceased to

operate in a racially segregated fashion, and is,

therefore, "unitary" in that limited sense, is not

synonymous with a finding that the entity is "fully

unitary" or has achieved "unitary, status."

Id. at 736 (thereafter citing Georgia State Conference of

Branches. and quoting most of the passage set out above.) In

light of the district court's acknowledgement that the two terms

have different meanings, it cannot be argued that the findings

made by the district court are equivalent to findings of

"unitary status."34

Indeed, it is difficult to discern why the district court

decided to dismiss these cases without making specific "unitary

status" findings. Although the court described "unitariness" as

a "will-o-the-wisp" concept at one point in its Nunnelley

opinion, it concluded that an ad hoc. case-by-case approach to

33 See Monteilh v. St. Landrv Parish School Board. 848

F.2d 625, 629 (5th Cir. 1988).

34 Even if the district court's opinion could somehow be

construed to have concluded that all vestiges of the dual systems

had been eliminated, such a finding would be clearly erroneous

based upon the undisputed facts alleged by plaintiffs.

26

e the issue was "not only unavoidable, but wise." 681 F. Supp. at

730. Nevertheless the court failed to address the question

squarely in these cases. This may well have been because of its

recognition that even on the facts produced through limited

discovery and without the hearing that plaintiffs sought,

findings of "unitary status" — which the court at one point in

its Nunnellev opinion appears to have equated with unattainable

"perfection," see 631 F. Supp. at 739 — could not be justified.

Because a finding that a school district has eliminated all

vestiges of its racially dual system and thus has achieved

"unitary status" must be made before a court can conclude a

school desegregation case, Georgia State Conference of Branches.

775 F.2d 1403 ; Pitts v. Freeman. 755 F.2d 1426,35 the district

court erred in concluding these cases without making such a

finding and the judgment below should be reversed.

Ill

The District Court Erred In Vacating The Permanent

Injunctions Without Finding That They Had Become

Burdensome Or Oppressive And That The Dangers Prevented

By The Injunctions Had Become Attenuated To A Shadow

We have argued above that it was error for the district

court to dismiss these cases without holding a hearing and

without making a finding of "unitary status." Reversal of the

judgment below on either or both of these grounds would

35 See also Lee Macon

(Nunnellev State Technical College),

County Board of Education

681 F. Supp. at 736.

27

necessarily mean that the portion of the district court's orders

vacating all injunctive relief previously granted in these cases

also could not stand, inasmuch as the fact of dismissal was the

basis for the district court's dissolution of its decrees.

We deal in this section of the brief with the separate

question whether, even if these school systems have achieved

"unitary status" and the cases are properly dismissed, all prior

injunctive orders entered in the lawsuits should be vacated.36

There are two aspects of this question: (a) does the achievement

of unitary status require dissolution of all prior remedial

decrees? (we contend that it does not) , and (b) what is the

correct legal standard for determining whether to vacate or

modify injunctive relief in a case?

The district court dissolved the permanent injunctions

entered in these cases because it concluded that defendants have

complied with the provisions of the injunctions and, at least as

to Sylacauga and Etowah County, have "operated a unitary system

over the past several years."37 Equating the determination of

unitary status38 with the decision whether to dissolve

36 Thus, even if the Court rejects our earlier arguments,

it should reverse so much of the orders below as vacated all

prior injunctive decrees in these cases. If the Court agrees

with us as to the error of dismissing these cases, it may

nevertheless wish to decide the questions addressed in this

section of the brief in order to provide appropriate guidance to

the district court on remand.

37 See supra note 25.

38 As we have shown in § II above, the district court did

not in fact make findings of "unitary status" in this case.

(continued...)

28

outstanding permanent injunctive relief, however, conflates the

separate substantive issues faced by a court in concluding a

school desegregation case — retention of active supervision and

dissolution of all injunctive remedies — and displaces the

established body of equitable principles applicable to the second

inquiry. The fact that a school district has complied with the

court's injunctive orders, and perhaps thereby attained "unitary

status," does not provide a basis for the conclusion that the

injunctions should be dissolved.38 39 In order to afford complete

relief, school authorities should be prohibited from taking

action that results in the loss of the benefits gained in the

litigation; if school authorities' decisions result in

reestablishment of the dual system, plaintiffs ought to be able

to return to court to protect the relief they obtained, by

enforcing the permanent injunction.40 See Keves v. School

38(...continued)

However, it purported to apply a legal rule dependent upon such a

finding. The discussion in text assumes arguendo that there has

been a predicate finding of "unitary status" in a case.

39 In fact this Circuit has never held that a finding of

"unitariness" or "unitary status," should be equated with

dissolution of all permanent injunctive relief. See Youngblood.

Lee v. Macon County (Baldwin County). United States v. Hinds

County. United States v. Texas Education Agency. Steele v. Board

of Pubic Instruction. Wright v. Board of Public Instruction.

Georgia State Conference of Branches. Pitts v. Freeman. United

States v. Jackson County cited supra at 19-24 and United States

v. Georgia. 691 F. Supp. 1440 (M.D. Ga. 1988).

40 As the Tenth Circuit put it in Dowell v. Board of

Education of Oklahoma Citv. 795 F.2d 1516, 1520, 1521 (10th

Cir.), cert. denied. 107 S. Ct. 420 (1986), rejecting, the

position of the government and the Fourth Circuit in Riddick v.

(continued...)

29

District No. 1. Denver. 653 F. Supp. 1536, 1541-42 (D. Colo.

1987) .40 41

The district court relied upon Judge Higginbotham's opinion

in United States v. Overton. 843 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.

1987) (dictum),42 for the proposition "that a finding of

40(...continued)

School Board of Norfolk. 784 F.2d 521 (4th Cir.), cert, denied.

107 S. Ct. 420 (1986), "the parties cannot be thrust back to the

proverbial first square just because the Court previously ceased

active supervision over the operation of the [desegregation

p]lan;" in order "[t]o make the remedy meaningful, the injunctive

order must survive beyond the procedural life of the litigation."

41 A rather pedestrian example underlines the point. If

the plaintiff in a nuisance action obtains an injunction to

prevent his neighbor from burning tires in his yard, spreading

fumes and particulate matter onto the plaintiff's property, the

fact that the neighbor complies with that order for five or ten

years does not provide a basis for the court to vacate the

injunctive decree and force the plaintiff to file a new lawsuit

if the neighbor resumes the practice. In no other area of the

law have plaintiffs found any cases where a defendant, after

having been found to have violated the law and being enjoined

from continuing that violation, is released from all restraint

based merely upon a showing that the injunction has not been

violated during its continuance, or based upon a finding that the defendant's current behavior conforms to legal requirements.

42 In Overton. a consent decree provided that the plan

which it embodied was to be implemented for a period of three

years, at the end of which time, "unless there is objection by

the parties," the school district "shall be declared to be a

unitary school system and this case shall be dismissed." 834

F.2d at 1173. After three years, an objection was made by one of

the parties but withdrawn by a further stipulation. After the

stipulation expired, the school district adopted a new pupil

assignment plan which the original plaintiffs sought to attack as

a violation of the consent decree. The district court held that

the consent decree was no longer enforceable and the Fifth

Circuit agreed, interpreting the decree itself to have terminated

at the end of the three-year period. Id. at 1174.

Once the panel concluded that the decree was "unenforceable"

because it had "expired by its own terms," there was no need to

decide any other issue in the case, especially an issue of the

(continued...)

30

unitariness calls for the dissolution of permanent injunctive

relief previously granted." (R2-25-15; R3-24-15; R4-26-15.)42 43

In so doing, the court below ignored the clear statement of this

Court: "That school districts have become unitary, however, does

not inevitably require the courts to vacate the orders upon which

the parties have relied in reaching that state." United States

v. Board of Education of Jackson County. 794 F.2d at 1543 (per

curiam). Unless Jackson County is to be overruled, therefore,

the trial court's justification for vacating the injunctive

decrees in these cases cannot be accepted.44

42(...continued'

scope or duration of constitutionally required relief. See

United States v. Henry. 709 F.2d 298, 310 (5th Cir. 1983); accord

United States v. Stuebben. 799 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1986).

43 See Lee v. Macon County (Nunnellev) . 681 F. Supp. at 737.

44 The district court attempted to distinguish Jackson

County. stating that the facts underlying that decision are

"inapposite" to these cases where "plaintiffs have had [many]

years under the benefit of the injunction in which to call to

this court's attention any failures on the [School] Board's part

to comply with the explicit terms of the permanent injunction."

R2-25-15; R3-24-15; R4-26-15. In Jackson County. however, this

Court's statement was a necessary rejection of an across-the-

board rule advanced by the United States and was not limited to

the facts of that suit; rather, it came in response to the

argument of the United States "that all orders flowing from

desegregation suits must be vacated with the dismissal of the

suits and that the unitary nature of the school districts removes

any basis for continuing jurisdiction," 794 F.2d at 1543.

What was fact-bound about this Court's Jackson County

decision was its affirmance of the district court's order there

vacating a 1970 decree because it had been complied with, had

achieved the purposes for which it was entered, and was no longer

necessary:

[T]he district court apparently accepted the resolution.

modifying the contract as fulfilling the 1970 order.

(continued...)

- 31

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. 402

U.S. 1, 12-16 (1971), the Supreme Court emphasized the holding of

Brown v. Board of Education. 349 U.S. 294, 299-300 (1955) (Brown

II) that traditional equitable principles would apply in

desegregation suits. The traditional equitable principle to be

applied in considering a request for modification or dissolution

of injunctive relief, once granted, is set forth in United States

v. Swift & Company. 286 U.S. 106 (1932), and its progeny:

The inquiry for us is whether the changes [in

circumstances] are so important that dangers, once

substantial, have become attenuated to a shadow. No

doubt the defendants will be better off if the

injunction is relaxed, but they are not suffering

hardship so extreme and unexpected as to justify us in

saying that they are victims of oppression. Nothing

less than a clear showing of grievous wrong evoked by

new circumstances should lead us to change what was

decreed after years of litigation with the consent of

all concerned.

286 U.S. at 119.44 45 Accord Dowell v. Board of Education of

44(...continued)This contract sufficed to obtain the state assistance

that the 1970 order was meant to obtain.

Id. This analysis is consistent with the Swift standards, see

infra at 32-33. (In Jackson County this Court was not asked to

consider the propriety of the district court's vacating the more

general 1969 desegregation order. 794 F.2d at 1543.)

45 In Swift. the Supreme Court rejected a request to

modify a decree enjoining the continuance of a combination of

meatpackers in restraint of trade. At another stage in the Swift

litigation, the district court denied a new request for

modification of the decree, rejecting the companies' argument

that the public would be adequately protected by the ability of

the parties to file new lawsuits:

It is of no avail to argue, as they have, that the

anti-trust laws . . . now provide ample remedies for

future violations. The public now enjoys the specific

(continued...)

- 32

Oklahoma City. 795 F.2d at 1521; Paradise v Prescott. 767 F.2d

1514 n.13 (11th Cir. 1985), aff'd. 107 S.Ct. 1053 (1987)

(employment discrimination claim under the Fourteenth Amendment);

Cable Holdings of Battlefield. Inc, v. Cooke, 764 F.2d 1466, 1474

n.19 (11th Cir. 1985) (contract, anti-trust, and securities law

claims).45 46

The fundamental misconception of the Overton dictum is, we

believe, its creation of a remedial jurisprudence in school

desegregation cases which is wholly separate and different from

these equitable principles, which the Overton panel itself

45(...continued)

protections of a decree. The defendants' contention

that the general law also forbids the conduct would be

equally available to prevent the issuance of any

injunction against future conduct, and would render the

equitable remedy nugatory.

United States v. Swift & Company. 189 F. Supp. 885, 906 (N.D.

111. 1960), aff'd per curiam. 367 U.S. 909 (1961). Accord

Securities & Exchange Commission v. Jan-dal Oil & Gas, Inc., 433

F. 2d 304 , 305 (10th Cir. 1970) (rejecting argument that

continuance of injunction was unnecessary because it did not

"gran[t] the S.E.C. any power that was not contained within the

act itself"); United States v. Western Electric Company, Inc. .

592 F. Supp. 846, 854-55 (D.D.C. 1984), appeal dismissed. 777

F.2d 23 (D.C. Cir. 1985).

46 Converting the "unitary status" determination into a

decision on dissolution or modification of injunctive relief

puts school desegregation cases into a category of their own and

affords plaintiffs in these suits less protection from future

injury to their constitutional rights than litigants whose claims

are purely economic. This is particularly inappropriate, given

that the right to be free from discrimination in education is one

of the most fundamental constitutional rights. Bob Jones

University v. United States. 461 U.S. 574, 592-93 (1983); Brown

v. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 483 (1954)(Brown I).

33

recognized were applicable "in other civil litigation, including

antitrust and securities cases," 834 F.2d at 1174.47

47 Overton is not persuasive for other reasons. For

example, the panel there misconstrued the language of Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. 402 U.S. 1 (1971),

upon which it sought to rely. See Overton. 834 F.2d at 1175,

text at n.ll. At the end of its opinion, the Supreme Court

indicated that following unitariness, in the face of demographic

change unaccompanied by school district actions, "a showing that

either the school authorities or some other agency of the State

has deliberately attempted to fix or alter demographic patterns

to affect the racial composition of the schools," id. at 32,

would be required to justify further judicial relief in a

desegregation suit.

The Overton panel quoted this passage with an ellipsis that

uprooted the Supreme Court's language from its context and

implied that conduct by school officials which brought about a

recurrence of the dual system following "unitariness" could be

remedied only upon the showing necessary in a new lawsuit—

intentional discrimination — and that school authorities had no

continuing obligations after "unitariness":

[I]n the absence of a showing that either the school

authorities or some other agency of the State has

deliberately attempted to fix or alter . . . the racial

composition of the schools, further intervention by a

district court should not be necessary.

834 F.2d at 1175 (emphasis and ellipsis added by panel). But see

the Supreme Court's language, 402 U.S. at 21, discussed below.

The Overton panel also erred in attempting to distinguish

the Lee v. Macon County (Baldwin County) ruling cited above, 584

F.2d 78 (5th Cir. 1981), which upheld the continuing jurisdiction

of the court following "unitariness."

The Overton opinion asserted that the statements in the

Baldwin County case "that a unitary district is 'bound to take no

actions which would reinstitute a dual school system' and that

school districts should maintain unitary status once achieved"

were made in "reli[ance] upon" the passage it quoted from Swann

and were therefore limited to the circumstances of deliberate

conduct emphasized by the Overton panel. In fact, the Baldwin

County decision cited an entirely different passage from the

Swann opinion for its conclusion:

In devising remedies where legally imposed segregation

(continued...)

34

Plaintiffs-appellants submit that consistent with this

Court's decision in Jackson County, the reasoned decision in

Dowell. harmonizing remedial principles in school desegregation

cases with those in other equitable suits in the federal courts,

rather than the mechanical rule espoused by the Overton panel,

should govern the issue of modification or dissolution of

injunctive relief in school desegregation suits in this Circuit.

The court below, however, made no attempt to determine either

that all vestiges of the discriminatory conduct by which the dual

system was maintained had been removed, or that the possibility

that such discriminatory conduct would recur had become

"attenuated to a shadow." Its ruling that the prior orders in

these cases should be vacated must therefore be reversed.

In sum, the district court erred in vacating the permanent

injunctions in these cases based on its conclusion that where

injunctions have been complied with and the court concludes that

the school district is unitary, those injunctions are to be

dissolved with dismissal of the case. 47

47(...continued)

has been established, it is the responsibility of local

authorities and district courts to see to it that

future school construction and abandonment are not used

and do not serve to perpetuate or re-establish the dual

system.

402 U.S. at 21; see 584 F.2d at 81. Lee v. Macon County (Baldwin

County), correctly construed and unaffected by the erroneous

characterization of the Overton panel, is controlling here. . See

Bonner v. City of Prichard. 661 F.2d 1206, 1209-11 (11th Cir.

1981)(en banc).

35

Conclusion

For the reasons stated above, plaintiffs-appellants

respectfully request that this Court reverse the final judgments

of the district court entered on July 8, 1988, with respect to

the Etowah County Board of Education, Sylacauga City Board of

Education, and Talladega City Board of Education, dismissing

these cases, dissolving all injunctive relief, and terminating

jurisdiction.

December 16, 1988

Respectfully submitted,

SALOMON S. SEAY, JW.

IP.O. Box 6215

''Montgomery, AL 3 6106

(205) 834-2000

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JANELL M. BYRD

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

36

Certificate of Service

copies of the Plaintiff-Appellants' Brief on Appeal from the

Northern District of Alabama was served by first class U.S. mail,

postage prepaid on the following individuals:

Cleophus Thomas, Jr., Esq.

P. 0. Box 2303

Anniston, AL 36202

Ralph Gaines, Jr., Esq.

Gaines, Gaines & Gaines, P.C.

Attorneys at Law

127 North Street Talladega, Alabama 35106

James R. Turnbach, Esq.

Pruitt, Turnbach & Warren

P.O. Box 29

Gadsden, Alabama 35902

Donald B. Sweeney, Jr. Esq.

Rives & Peterson

1700 Financial Center

Birmingham, A l a b a m a 35203

Dennis J. Dimsey, Esq.

Thomas E. Chandler, Esq.

Department of Justice

Civil Rights Division

Appellate Section

P.O. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

Frank Donaldson, Esq.

Caryl Privett, Esq.

Office of the United States Attorney

1800 Fifth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jim R. Ippolito, Jr., Esq.

609 State Office Building

Montgomery, Alabama 36130

37

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

ANTHONY T. LEE, ET AL., )

Plaintiffs, )

)vs. )

)UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

Plaintiff-Intervenor )

and Amicus Curiae, )

)NATIONAL EDUCATIONAL )

ASSOCIATION, INC., )

Plaintiff-Intervenor, )

)vs. )

)MACON COUNTY BOARD OF )

EDUCATION ET AL., )

Defendants. )

____________________________________ )

UNITED STATES' MOTION AND SUPPORTING

MEMORANDUM REQUESTING FURTHER RELIEF

On August 8, 1988 the Shelby County Board of Education

(Shelby County), in compliance with this Court's order granting

the United States' motion to compel, filed its response to

objections raised by the United States and private plaintiffs to

a finding that Shelby County has achieved unitary status. The

United States filed its objections on April 12, 1988, stating

that prior to a declaration of unitary status and dismissal, the

Shelby County School District (Shelby County) should be required

to produce evidence that it has continued to comply with this

Court's orders in the area of faculty hiring and promotion.

On July 8, 1988, prior to receiving Shelby County's response

to the objections filed by the United States and private

CIVIL ACTION NO.

7 0-AR-251-S

(SHELBY COUNTY)

plaintiffs, this Court concluded that a hearing was appropriate

to allow the parties to present additional evidence on whether

the school district has reached and maintained unitary status

sufficiently to allow the action to be dismissed. The defendant

school districts were given the option of proceeding to hearing

on the question of unitary status and dismissal or of taking nine

months to come into compliance. Shelby County chose to proceed

to hearing, apparently believing that they are entitled to a

finding of unitary status and dismissal of their case. The

hearing is currently set for August 31, 1988.

In responding to the concerns raised by the United States

regarding faculty hiring and promotion, Shelby County admits in

its response filed on August 8, 1988 (filed following an order

granting the United States' motion to compel such a response),

that it hires faculty so that the ratio of black faculty is the

same as the ratio of black students in the district.

Accordingly, the percentage of black faculty has decreased over

time as has the percentage of black students.

Such a standard for hiring faculty members is clearly

discriminatory, is in violation of this Court's orders,^- and

1 The permanent injunction entered on July 25, 1974 enjoins

the school district from operating a dual school system and

requires that:

Staff members who work directly with children, and

professional staff who work on the administrative

level, will be hired, assigned, promoted, paid,

demoted, dismissed, and otherwise treated without

regard to race, color, or national origin.

2

precludes a finding that Shelby County has attained unitary

status. The admitted practices of Shelby County of hiring and

assigning faculty in accordance with the racial composition of

the student enrollment represent, indeed, affirmative,

intentional discrimination by the school district. See generally

Wyqant v. Jackson Board of Education. 476 U.S. 267 (1986.)2 We

note further that the proper standard for faculty assignment

within a school district is to assign faculty and staff to

district schools so that the ratio of white to black faculty is

substantially the same at each school in the district, i.e..

reflects the overall district-wide percentage of faculty.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District. 419 F.2d