Plaintiffs-Appellees' Motion for Order Restoring Injunction with Cover Letter

Public Court Documents

April 18, 1977

66 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs-Appellees' Motion for Order Restoring Injunction with Cover Letter, 1977. 7509dc73-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cbaab897-c419-4cf7-b926-8d35fb45d9a3/plaintiffs-appellees-motion-for-order-restoring-injunction-with-cover-letter. Accessed March 09, 2026.

Copied!

* 4

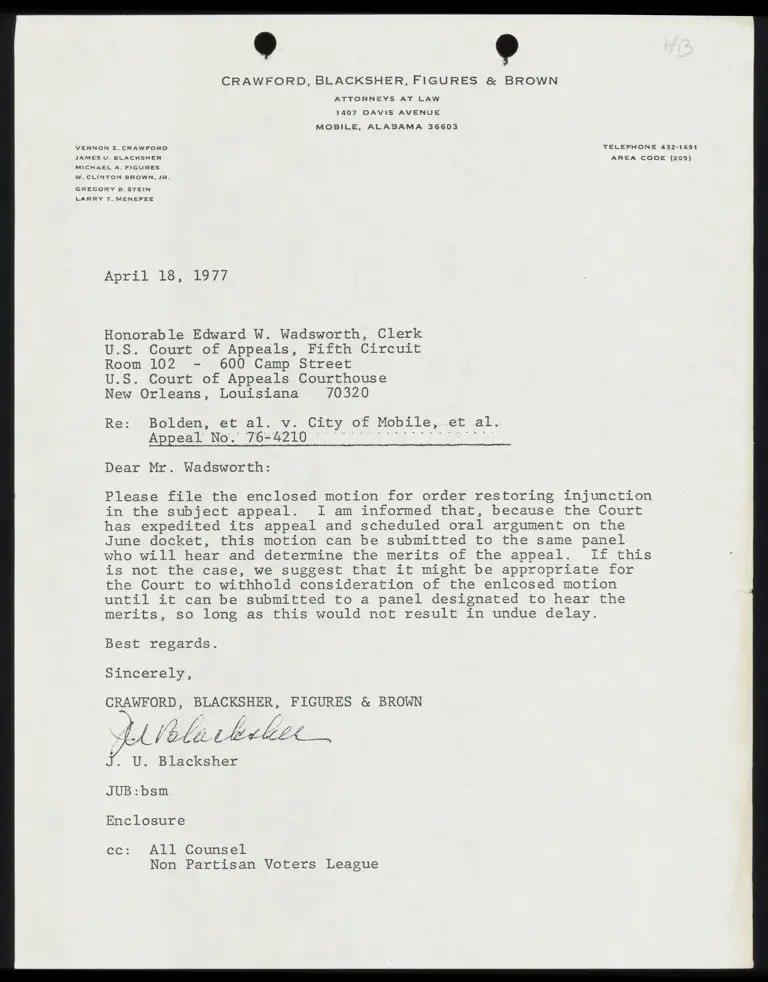

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

1407 DAVIS AVENUE

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

VERNON Z. CRAWFORD TELEPHONE 432-1691

JAMES U. BLACKSHER AREA CODE (205)

MICHAEL A. FIGURES

W. CLINTON BROWN, JR.

GREGORY B. STEIN

LARRY T. MENEFEE

April 18, 1977

Honorable Edward W. Wadsworth, Clerk

U.S. Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit

Room 102 - 600 Camp Street

U.S. Court of Appeals Courthouse

New Orleans, Louisiana 70320

Re: Bolden, et 2) vy. Ciry.. of Mobile, et al.

Dear Mr. Wadsworth:

Please file the enclosed motion for order restoring injunction

in the subject appeal. I am informed that, because the Court

has expedited its appeal and scheduled oral argument on the

June docket, this motion can be submitted to the same panel

who will hear and determine the merits of the appeal. If this

is not the case, we suggest that it might be appropriate for

the Court to withhold consideration of the enlcosed motion

until it can be submitted to a panel designated to hear the

merits, so long as this would not result in undue delay.

Best regards.

Sincerely,

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

AIL i eloles ~

7 U. Blacksher

JUB:bsm

Enclosure

cc: All Counsel

Non Partisan Voters League

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-4210

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

VS.

WILEY 1. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For the Southern District of Alabama

Southern Division

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES'

MOTION FOR ORDER RESTORING INJUNCTION

Plaintiffs-Appellees Wiley L. Bolden, et al., on behalf

of themselves and the class of black citizens they represent,

move this Court for an Order restoring the injunctions issued

in favor of Plaintiffs-Appellees by the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Alabama on October 21,

1976, and March 9, 1977, which injunctions were stayed pending

appeal by the District Judge on April 7, 1977.

Alternatively, Plaintiffs-Appellees move the Court for

an Order modifying the aforesaid stay of the District Court

by enjoining the holding of elections of any kind for the

government of the City of Mobile, Alabama, for a specific

period of time or pending this Court's decision on the merits

of this appeal.

As grounds for their motion, Plaintiffs-Appellees would

show as follows:

1) This action was filed in the District Court on

June 9, 1975, by fourteen (14) black citizens of the City

of Mobile, Alabama, claiming that the at-large system of

electing Mobile City Commissioners bridges their rights and

the rights of other black citizens under the First, Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States; under the Civil Rights Act of 1871, 42

U.5.C. §1983; and under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.5.C. §1973. The Defendants are the City of Mobile and its

three (3) incumbent City Commissioners in their individual

and official capacities.

2) This case was tried before the District Judge

on July 12-2], 1976, and the District Court entered its

findings of fact and conclusions of law in favor of the

black Plaintiffs on October 21, 1976. Bolden v. City of

Mobile, 423 F.Supp. 384 (1976). In its thorough and exhaustive

opinion, the District Court made extensive findings following

the formula of Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) (en banc), aff'd sub nom. East Carroll Parish School

Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.8. 636 (1976). Ir found that the

political process leading to election is not open to blacks,

been

that the at-large elected city government has not/and is not

responsive to black citizens on an equal basis with whites,

and that past official discrimination continues to contribute

to dilution of black voting strength. Among Zimmer's

1 "enhancing factors," the court found that the at-large election

system involves a district that is as large as possible, that

City Commissioners must be elected by a majority vote, that

a numbered place provision has to some extent the same results

as anti-single-shot voting provisions, and that there are

no residency requirements for City Commissioners. 423 F.Supp.

at 399-402.

3) The District Court rejected the Defendant City

Commissioners' primary defense, that because disenfranchised

blacks were not a political factor when the present at-large

elected City Commission form of government was created by

the Alabama Legislature in 1911, Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229 (1976), precluded judgment for plaintiffs because

initial discriminatory purpose could not be shown. The court

held that Washington prohibits as unconstitutional facially

neutral statutes that are applied in a purposefully dis-

criminatory fashion:

There is a "current" condition of dilution

of the black vote resulting from intentional

state legislative inaction which is as

effective as the intentional state action

referred to in Keyes [v. School District No.

1,413 10.8, 180 (1973). 7.

423 F.Supp. at 398 (emphasis supplied by the court).

4) The District Court reached its conclusion in

favor of the black Plaintiffs by following the teachings of

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973); Dallas County v. Reese,

421 U.S. 477 (1975); Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra; Fortson v.

Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (1965); and Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S.

124 (1971).

In summary, this court finds that the

electoral structure, the multi-member at-

large election of Mobile City Commissioners,

results in an unconstitutional dilution of

black voting strength. It is "fundamentally

unfair,” Wallace [v. House, 515 F.2d 619,

630 (5th Cir. 1975), vacated on other grounds,

425 U.S. 947 (1976)], and invidiously dis-

criminatory.

423 F.Supp. at 402.

5) Because City Commissioners combine within

themselves both legislative andy IR254E1S, or administrative

powers, the District Court agreed with the Defendant

Commissioners that election of City Commissioners from single-

member districts "would at a minimum be anomalous and

probably unconstitutional.’ 423 F.Supp. alt 420 n.19.

Accordingly, the court ordered the City of Mobile to change

its form of government to a strong mayor-council system.

423 F.Supp.at 403-04.

6) Finally, the District Court certified its

October 28, 1976, Order for interlocutory appeal pursuant to

28 U.S.C. §1292(b), and gave the following admonition to

the Defendant City Commissioners:

It is the court's desire that if

this order is appealed, such an appeal

be taken promptly in order to provide

the appellate courts with an opportunity

to review, and, if possible, render a

ruling prior to the campaign and election

for the city government offices as

scheduled for August, 1977.

423 F.Supp. at 404.

7) However, eschewing the District Judge's

invitation promptly to appeal within the ten (10) days

allowed for appeals under 28 U.S.C. §1292(b), the Defendant

Commissioners did not appeal the District Court's October

21 decision until November 19, 1976 (apparently relying on

28 U.S.C. §1292(a)).

8) Following his October 21, 1976, decision the

District Judge appointed a blue-ribbon committee of prominent

Mobile citizens to formulate and recommend a strong mayor-

council plan of government. The court requested the

Plaintiffs and Defendants to submit proposed district

boundaries; the Plaintiffs complied, but the Defendants

declined to file a plan. When the blue-ribbon committee

submitted its recommendation to the court, the district judge

asked the parties and all members of the Mobile County

Legislative Delegation to make their recommendations. The

attorneys for the Plaintiffs and one member of the Mobile

County Delegation accepted the court's invitation and made

recommendations, many of which were ultimately incorporated

in the district court's final plan, entered by Order dated

March 9, 1977. The court ordered that the mayor-council

plan, which is modeled after strong-mayor plans presently

in use in Birmingham and Montgomery, be placed in effect

in time for the August 1977 city elections. A copy of the

District Court's March 9, 1977, Order is attached To {his

motion as Attachment A.

9). On or about March 18, 1977, the Defendant

City Commissioners filed an application for stay pending

appeal urging the District Court "to order that all elections

and electoral changes in Mobile's present scheme of government

be stayed pendente lite and that Its Orders of October 21,

1976, and March 9, 1977, be vacated pendente lite." A

copy of Defendants' application for stay in the District

Court is attached to this motion as Attachment B.

10) On or about March 23, :1977, Plaintiffs filed

their opposition to the application for stay pending appeal.

In it, Plaintiffs asked the District Judge to deny the stay

altogether or, alternatively, to grant only a temporary

stay of its Orders for the short time necessary for the

Defendant Commissioners to present their petition for a stay

to this Court, if they chose to do so. A copy of Plaintiffs"

opposition 1s attached to this motion as Attachment C. Also

attached as Attachment D is the proposed temporary stay of

injunction Plaintiffs suggested to the District Court.

11) On or about March 31.and April 1, 1977, the

City Commissioners and the black Plaintiffs, respectively,

filed supplemental briefs with the District Court. The

supplemental briefs are attached to this motion as Attachments

E and F. In their supplemental brief, Plaintiffs suggested

still another alternative to the District Judge, in the

event he was not inclined to deny the stay altogether:

staying all city elections for a specified term, possibly

three months. This last alternative would have avoided the

undesirable contingency of an early ruling by this Court

coming during the middle of an election campaign or shortly

after new commissioners had been elected. Setting a date

certain for expiration of the stay would have provided this

Court the flexibility needed either to rule on the merits

or extend the stay and would have served the important public

interest of avoiding confusion and unnecessary expense by

letting the electorate and aspiring candidates know what to

expect and when. See Attachment F, pp. 6-7.

12) On April 7,.1977, the District Court granted

the stay requested by the City Commissioners for an indefinite

period pending outcome of the appeal. A copy of the court's

stay order is attached to this motion as Attachment G. In

his Order, the District Judge agreed with the City Commissioners

that the actual election and institution of a mayor-council

government pending appeal would create great confusion and

disruption if this Court reversed. Order granting stay,

p. 3. The court acknowledged the standards for granting a

stay set out in Belcher v. Birmingham Trust Nat'l Bank, 395

F.24 685 (5th Cir. 1963). However, it concluded that the

Defendant Commissioners did not have to make a significant

showing with respect to all four factors. Id. Accordingly,

the court granted the stay requested even though it found

there was virtually no likelihood the City Commissioners would

prevail on appeal. Attachment G, p.6. It determined that

"[n]o substantial harm would befall plaintiffs," because,

even though the at-large system of electing commissioners

was unconstitutional, Plaintiffs would be suffering continuing

injury only for "a reasonably short time." Attachment G., p.

De

13) In its Order, the District Court 4id not reveal

its reasons for rejecting the option of staying all elections

pending appeal, thus avoiding the confusion, expense and

politically distorted circumstances that necessarily will

accompany August 1977 elections under either the Commission

or the Mayor-Council form of government. Rather, the court

announced:

This stay 1s subject to review and

change should the Fifth Circuit Court

of Appeals affirm this court within a

time prior to the August, 1977, elections

for a meaningful campaign to be held

under this court's prior order. In any

event, if there is a final affirmance by

an appellate court, elections shall be

ordered to occur within a reasonable time

thereafter in accordance with this court's

prior orders.

Appendix G, p. 7.

14) Plaintiffs-Appellees respectfully submit that

the Honorable District Judge abused his discretion by granting

the stay requested by the City Commissioners, as a matter of

law and as a matter of equity.

Because The City Commissioners Are Unable

To Show Likelihood Of Reveral, Their

Application For Stay Should Have Been Denied

15) it its Order granting the stay, the Districrk

Court emphasized its "firm ... belief that its order granting

affirmative relief to the plaintiffs ... will be affirmed by

the appellate courts." Attachment G, p. 6. Notwithstanding

the absence of this first of the four factors prescribed by

Belcher v. Birmingham Trust National Bank, supra, for obtaining

a stay, the District Judge tnterprated this Court's decisions

as allowing him to balance the absence of one of the four

Belcher factors against the weight of other factors found to

be present. Attachment G, Pp. 3. In this respect, the court

erred as a matter of law. The four factors set out in Belcher

and Plecher v, Laird, 415 ¥.24 473, 744 (5th Cir. 1969). are

stated in the conjunctive mode, and the City Commissioners had

the burden of establishing the existence of all four factors

for the granting of a stay. The cases relied on by the district

court, Long v, Robinson, 432 ¥.24 977, 98 (4ch Cir. 1970).

cited with approval in Beverly v. United States, 468 F.2d 732,

74) n.13 (5th Cir. 1972), do not provide otherwise.

16) Indeed, there is no likelihood that the

Defendants-Appellants will prevail on the merits of this appeal.

~10.

This Court has previously stated that it will give great

deference to the District Court's "intensely local appraisal”

and determination of the Zimmer factors. See Paige v. Gray,

5383 7.24 1108, 1111 (5th Cir. 1976). The City Commissioners

do not seriously contend there is a likelihood that the careful

findings of fact made by the District Judge will be overturned

on appeal.

17) The City Commissioners' primary legal contention

also plainly is without merit. The Defendants cannot seriously

deny that the District Court's ruling on Washington v. Davis

follows the existing law established by this Court. Nevett wv.

Sides, 533 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir. 1976); McGill v. Gadsden County

Commission, 535 F.2d 277 (5th Cir. 1976); and Paige v. Gray,

supra are all post-Washington v. Davis voter dilution cases

from the Fifth Circuit. They uniformly reject Defendants’

argument that Washington v. Davis and its progeny have under-

mined the voter dilution standards of Zimmer v. McKeithen.

The Stay Should Have Been Denied Because

Of The Irreparable Injury Black Citizens

Will Suffer From At-Large Elections

18) The District Court found as a matter of law

and fact that black citizens' constitutional rights are

abridged by the at-large election of City Commissioners.

However, it accepted the Defendants' argument that blacks,

having suffered the unconstitutional deprivation of their

voting rights for sixty-six years, would not sustain substantial

harm by enduring this injury a little longer.

19) But the Supreme Court has instructed federal

courts to weigh unconstitutional impairments to fundamental

rights of suffrage with the highest of priorities. The right

to an unimpaired, equal vote is "a fundamental political

right, because preservative of all rights." Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533, 562 (1964), quoting Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S.

356, 370. "When an alleged deprivation of a constitutional

right is involved, most courts hold that no further showing

of irreparable injury is necessary." 11 Wright & Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure, Civil §2948, p. 440 (1973)

(footnote omitted). See Doe v. Monday, 514 F.2d 1179 (7th

Cir. 19753); A Quaker Aciion Croup v. Hickel, 421 F.2d 13111.

1116 (D.C. Cir. 1969); Keefe Vv. Geanakos, 418 F.2d 359 (4th

Cir. 1969); Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284 F.2d

631, 633 (4th Cir. 1950).

Alternatively, This Court Should Stay

Blecrions Df Any Kind =~ ma oe

20) This appeal has been scheduled for expedited

Moder 4 :

briefing, and the case is set for oral argument on this

Appellants-City Commissioners’ brief was filed April 10,

1977; Plaintiffs-Appellees brief is due May 10, 1977.

~¥2.

Court's June Docket. Undersigned counsel has been informed

by the Clerk that where briefing and oral argument have been

expedited, it is this Court's practice also to expedite

deliberation toward reaching a decision on the merits.

21) The present qualificstion date for candidates

in a City Commission election will be the third Tuesday in

June, and elections will be held the third Tuesday in August,

with any necessary runoff the first Tuesday in September.

Title 37, §§34(74), 34(78), Code of Alabama (Supp. 1975).

Alabama general law provides that, under the mayor-council

form of municipal government, candidates must qualify by the

first Tuesday in July, and the election is to be held on the

second Tuesday in August. Title 37, §§34(21), 34(25), Code

of Alabama (Supp. 1975). Thus, under the District Court's

Order granting a stay, the campaign and election for City

Commission will be held after argument to this Court in June,

and there is a substantial chance that this Court will render

an opinion during the campaign or shortly after the elections.

22) A City Commission campaign and election

conducted under the uncertainty of this pending appeal will

greatly distort the normal political processes in Mobile.

No serious challengers will enter the contest against the

incumbent Commissioners. The cost of a

serious campaign (between $30,000 and $100,000) and the

probability that the Commission form is unconstitutional mean

that the victors will enjoy a very short term in office.

23) The mere administrative cost of voting

officials in conducting a city-wide election will be approximately

$250,000. Of course, the campaign costs for candidates could

easily approach hundreds of thousands of dollars. All citizens

will be greatly injured if such a costly process is declared

anullity shortly after or, possibly at the same time, the

election is held. Yet this is the most likely prospect if

Commission elections are allowed to go forward as regularly

scheduled. No other elections are normally scheduled to

be conducted with the August election of City officials.

Accordingly, postponement of the City elections would cause

no additional expense when, following determination of this

appeal, the stay were dissolved.

24) If City Commission elections are allowed to

go forward in August 1977, after the district court's judgment

is affirmed on appeal, the newly elected commissioners could

still complain that dissolving the stay before the end of

their four-year term would be inequitable because of the

financial losses it would cause both them (campaign monies

spent) and the City (the cost of new elections). Even if

the district court rejected these arguments, the Commissioners

might still keep themselves in office longer by successfully

appealing dissolution of the stay. Thus, allowing the

we, PR

Commission elections to go on, rather than staying elections

altogether, poses additional risks that Plaintiffs will

continue unconstitutional deprivation of their voting rights.

25) This Court and other federal courts have

previously approved the stay of municipal elections pendente

lite in situations where the voting rights of black citizens

were clearly being denied. In Hamer v. Campbell, 358 F.2d

215 (5th Cir. 1966), black voters were denied the right to

participate in municipal elections on an equal basis with

whites. Plaintiffs requested a preliminary injunction

against the town elections, and this Court held that it

should have been granted. The Court first held: "There can

be no question that a District Court has the power to enjoin

the holding of an election." 358 F.2d at 221. Next, the

Court held that because plaintiffs had established a deprivation

of their voting rights, reliance on reapportionment cases

allowing elections to go forward under an unconstitutional

plan was misplaced. In Reynolds v. Sims, supra, 377 U.S. at

585, "[t]he Court clearly warned that it 'would be the unusual

case in which a court would be justified in not taking

appropriate action to insure that no further elections are

conducted under the invalid plan.'" 358 F.2d at 222.

26) Although Hamer involved no at-large voting,

but discrimination in registration, the principles of that

~154

case are equally applicable here. As the Supreme Court has

indicated, at-large voting can 'mullify [minority voters']

ability to elect the candidate of their choice just as would

prohibiting some of them from voting." Allen v. State Board

Of Elections, 383 U.8.: 544, 569. (1969).

27) In several recent cases, the Supreme Court and

lower federal courts have held that a determination of dilution

of black voting strength requires the court to stay the

elections and not permit them to go forward under a dis-

criminatory scheme. In Holt v. City of Richmond, 406 U.S. 903

(1972), Richmond, Virginia, annexed a large white residential

area and prepared to hold municipal elections. Upon submission

of the annexation under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act,

the Attorney General objected that the annexation would dilute

black woting strength in Richmond. The district court refused

to enjoin the elections, but on appeal the Supreme Court entered

the injunction only eight days before the elections were due

to be held.

28) Similarly, in City of Petersburg v. United States,

354 F.Supp. 1021, 1023-24 (D. D.C. 1972) (three-judge court).

aff'd, 410 U.S. 962 (1973), the district court enjoined the

Petersburg municipal elections after the Attorney General had

determined that the annexation diluted black voting strength.

23) In Beer v. United States, 374 F.Supp. 353,372

(D. D.C. 1974) (three-judge court), rev'd on other grounds,

425 8.8. 130:€1976), borh the District of Columbia district

court and a Louisiana district court enjoined the New

Orleans municipal elections after the Attorney General

determined that the redistricting plan for the City Council

minimized and canceled out black voter strength. Also, in

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 410 (1971) ,black plaintiffs

challenged a change from ward to at-large aldermanic elections

for lack of Section 5 clearance. A single district judge

temporarily enjoined the 1969 municipal elections, but the

three-judge district court dissolved the temporary injunction.

400 U.S. at 383. The Supreme Court held that the single

district judge was right. 400 U.S. at 384-85.

30) Although these cases involved objections

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, the black citizens

of Mobile are entitled to no less relief where the district

court has entered a judgment determining that the at-large

elections in Mobile minimize and cancel out their voting

strength in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments and the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973. Indeed,

it can be argued that plaintiffs here are in an even stronger

position for urging stay of all elections when they have

obtained through exhaustive litigation a judicial determination

17

of unconstitutional deprivation, which the district court

iteself thinks is unlikely to be reversed.

31) Staying all further City elections pending

this appeal would serve the same beneficial purposes cited

by the district court in Paige v.Gray , 399 F.Supp. 439 (M.D.

Ga. 1975), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 538 F.2d

1108 (5th Cir. 1976), when it entered a preliminary injunction

postponing the eminent municipal primary election for five

Albany, Georgia,City Commissioners elected on an at-large

basis. The defendants there suggested that the incumbent

City Commissioners should be allowed to hold office pending

action by the State Legislature, but the district court

held that any action which perpetuated the existing at-large

system would be tantamount to sanctioning an unconstitutional

system and would cause plaintiffs irreparable injury. The

court held that it would not countenance

a new, regular election to be conducted

under a law that is now and since 1947

has been unconstitutional because it

violates one of the most precious

possessions that all citizens have --

the right to vote. To do so would be

to irreparably harm the right not of

just the plaintiffs but of every citizen

to vote for the elected officials of

their city government.

393 F.Supp. at 467.

32) To allow new City Commission elections to go

forward in Mobile under the present at-large system would

amount to judicial countenance of a violation of the rights

of all black Mobilians.

33) There is absolutely no evidence that the

appellant Commissioners or other interested persons would

be irreparably injured by a stay of all municipal elections

pending appeal. The incumbent Commissioners cannot be

injured by an order that entitles them to continue holding

office until their successors are sworn in. Since under

Alabama law the current terms of the incumbents do not

expire until the first Tuesday in October 1977, a stay of

all elections might even allow this Court time enough to

court

affirm the district/on the merits of this appeal and order

mayor-council,single-member district elections without having

to extend any of the Defendants in office.

WHEREFORE, Plaintiffs-Appellees pray that this Court

will grant their motion and enter an order restoring the

injunctions issued by the District Court on October 21, 1976,

and March 9, 1977, providing for change in form of municipal

government for Mobile from a City Commission form to a strong

Mayor-Council form, with the election of council members

from single-member districts in August 1977.

Alternatively, Plaintiffs-Appellees pray that the Court

will modify the stay entered by the District Court on April

7, 1977, by enjoining the holding of any elections for the

government of the City of Mobile for a specific period of

time or indefinitely pending this Court's decision on the

merits of this appeal.

/

TZ

Respectfully submitted this LL day of April, 1977.

NY 4 2 Ct bolond

U. SER

ga MENEFEE

EDWARD STILL, ESQUIRE

601 TITLE BUILDING

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG, ESQUIRE

ERIC SCHNAPPER, ESQUIRE

SUITE 2030

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

- CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

1 do hereby cercify that on this the 18th day of April,

1977, I served a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES'®

MOTION FOR ORDER RESTORING INJUNCTION upon counsel of record,

C. A. Arendall, Esquire, Post Office Box 123, Mobile, AL

36601, Fred G. Collins, Esquire, Post Office Box 16629,

Mobile, Alabama 36616 and Charles Rhyne, Esquire, 400 Hill

Building, Washington, D. C. 20006, by depositing same in

United States Mail, postage prepaid.

RL ri

0

- Qc

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, REV. R. L.

HOPE, CHARLES JOHNSON, JANET

0. LeFLORE, JOHN L. LeFLORE,

CHARLES MAXWELL, OSSIE B.

PURIFOY, RAYMOND SCOTT,

SHERMAN SMITH, OLLIE LEE

TAYLOR, RODNEY O. TURNER,

REV. ED WILLIAMS, SYLVESTER

WILLIAMS and MRS. F. C. WILSON,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION

V.

No. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA: GARY

A. GREENOUGH, ROBERT B. DOYLE, JR.,

and LAMBERT C. MIMS, individually

and in their official capacities

as Mobile City Commissioners,

N

e

No

SN

N

f

No

SN

N

S

N

S

N

N

N

A

N

o

N

N

N

F

N

N

N

N

N

S

Defendants.

ORDER

On the 21st day of October, 1976, this court entered

an order in this cause. The order decreed that a mayor-council

plan of government would be adopted by this court with nine

single-member council districts.

The court requested and received from the plaintiffs

and defendants, three names recommended by each from whom the

court selected a committee to formulate and recommend a mayor-

council plan. The court selected two names recommended by the

defendants, City of Mobile, et al.; Joseph N. Langan and Arthur

R. Outlaw, two former city commissioners of the City of Mobile,

one recommended by the plaintiffs,

and /James E. Buskey, a black State Legislator.

The court requested the plaintiffs and defendants to

submit proposed councilmen districts made up of nine single-

member districts. The plaintiffs complied. The defendants

declined to file a plan.

The committee appointed by the court to draft a mayor-

council plan submitted an initial plan. The court submitted

the plan to all of the parties for their recommendations and

invited all members of the Mobile County legislative delegation

to make recommendations. The attorneys for the plaintiffs,

and one member of the Mobile County delegation, accepted the

invitation and made recommendations, many of which have been

incorporated in the final plan. The defendants declined to

make any Bob mndart ons. or is members of the Mobile

legislative delegation expressed a general view that it created

a conflict between their legislative duties and the judicial

branch and did not desire to make recommendations .i/

It is hereby ORDERED, ADJUDGED, and DECREED that

the mayor-council plan attached to this order as Appendix A,

is hereby ADOPTED and made a part of this order the same as.

if set out at length herein.

It is further ORDERED, ADJUDGED, and DECREED that

the nine single-member council districts as submitted by the

plaintiffs' Plan "H", together with the map attached to the

plan as Exhibit "A", both of which are attached to this order

as Appendix B, is hereby ADOPTED and made a part of this order

the same as if set out at length herein.

Beginning at the regularly scheduled city elections

in August 1977, and each four years thereafter, the City of

Mobile shall elect nine members to a city council and a mayor.

The mayor and the city council shall have such powers, duties

and responsibilities as are established by the report of the

committee appointed by this court on October 6, 1976, attached

hereto as Appendix A, and as are established by the provisions

of Ala. Code, Tit. 37, dealing with cities generally or cities

having a mayor-alderman form of government. To the extent that

the report or this order conflicts with the Alabama Code, the

report or order shall prevail.

One member of the City Council shall be elected by

and from each district. A candidate for the council and each

1/ Some declined because the City of Mobile was not in their

district.

A 1A

member of the council shall reside in the district represented

or sought to be represented.

Nothing in this order shall prevent the defendants

or Legislature of Alabama from changing the powers, duties,

responsibilities, or terms of office of the city council and

mayor, or changing the boundaries of wards or districts, or

changing the number of wards; provided however that the court

retains jurisdiction for six years from the date of this order

to review such changes for conformity with the principles

enunciated in the order of this court entered in this case

on October 21, 1976.

The court is aware that numberous local acts having

application to the City of Mobile are in effect. Because

of the change from a commission form to a city council form,

there may be conflicts between the plan herein adopted and

those acts. The court specifically retains jurisdiction for

a period of two years from the date the first city council

members take office for all purposes for persons having standing.

The retained jurisdiction of this court under the

two preceding paragraphs shall be dissolved upon motion of

either party when and if the Legislature of Alabama adepts

(a) a comprehensive act establishing a constitutional form of

government for the City of Mobile, or (b) enables the City of

Mobile to act under "home rule" powers to adopt such a compre-

hensive act.

The defendants City of Mobile, Gary A. Greenough,

Lambert C. Mims, Robert B. Doyle, Jr., and their agents, ser-

vants, enploviss, and successors are hereby ENJOINED from failing

to make the following changes with respect to the election of

the elected officials of the City of Mobile:

ls

1. Ward 33-99-1 is hereby split into east and west

wards, divided by a line beginning at the south boundary of

the ward on Stanton, inning north to Costarides, west to

Summerville, north to Andrews, and east to theward boundary.

The voters in these two areas may be constituted as separate

wards or the eastern area may be reassigned as part of MW-33-

99-2,

2. Ward 35-103-1 is split into eastern and western

divisions by a dividing line beginning at the west boundary

of the ward, running east on Davis Avenue, south on Kennedy to

the ward line. The two divisions shall be constituted as separate

wards.

3. Ward 35-103-3 is split into northern and southern

divisions by a line beginning in the northward boundary on |

Broad Street, running south to Elmira, east to Dearborn Street,

south to New Jersey, hE: to Warren Street, north to Delaware,

east to Interstate 10, south to Virginia Street, and east to

Mobile Bay. These two divisions may be established as separate

wards or the northern division may be redesignated as part of

MW-35-103-2.

4. Ward 34-100-3 is split into southeastern and

northwestern divisions by a line beginning on the east at 01d

Shell Road, west to East Drive, south to North Shenandoah,

west to East Cumberland, south on East Cumberland and Ridgefield

Road to the ward line. The residents of the southeastern area

shall be reassigned to MW-34-100-2 or made a new ward.

5. Ward 35-104-2 is divided by a line beginning at

the north ward boundary on Eslava Creek, running south along

Eslava Creek and Dog River to old Military Road, eastwardly

to Dauphin Island Parkway, south to Rosedale Road, east to

Brookley Field boundary and following said boundary eastwardly

to Perimeter Road, thence east on Perimeter Road to Mobile Bay.

The eastern portion of this ward may be designated a new ward

or merged into MW-35-104-1. The western portion of this ward

may be designated a new ward or merged into MW-35-104-3.

villi

6. Nothing in this order shall prevent the defendants

from changing any other ward boundaries, so long as the

boundaries described in this order for the new council districts

are not disturbed.

7. The defendants shall undertake the merger or

redesignation of wards immediately and shall inform each voter

in an area designated or merged of the new ward designation

in which he or she lives. The defendant shall work with the

Board of Registrars to accomplish this task by May 1, 1977.

If the defendants encounter problems with the Board of Regis-

trars, they shall forthwith petition this court for an appro-

priate order, including making the Board of Registrars a party

defendant.

8. The following districts for the election of

members of the City Council of Mobile are hereby created and

designated:

- District 1 shall consist of MW-33-98-1 and

the western portion of MW-33-99-1.

| - District 2 shall consist of the eastern part

of MW-33-99-1, all of MW-33-99-2, MW-33-99-3, and MW-34-102-2,

and the western part of MW-35-103-1.

- District 3 shall consist of MW-33-99-4, the

eastern part of MW-35-103-1, MW-35-103-2, and the northern

part of MW-35-103-3.

- District 4 shall consist of the southern part

of MW-35-103-3, MW-34-102-3, MW-34-102-6, and MW-34-102-7.

- District 5 shall consist of MW-35-103-4,

MW-35-104-1, and the eastern part of MW-35-104-2.

- District 6 shall consist of MW-35-104-3,

- MW-35-104-4, MW-35-104-5, and the western part of MW-35-104-2.

- District 7 shall consist of MW-34-100-1,

MW-34-100-2, MW-34-101-4, MW-34-101-5, MW-34-101-6, and the

southeastern part of MW-34-100-3.

5.

- District 8 shall consist of MW-34-102-5,

MW-34-102-1, MW-34-101-2, MW-34-101-3.

- District 9 shall consist of MW-34-101-1,

MW-34-101-1, MW-34-100-4,

MW-34-100-3.

9. The defendants shall forthwith take all steps

and the northwestern part of

necessary to prepare for the election of the city council

and mayor.

The court reserves a decision upon the plaintiffs’

claim for attorneys' fees and ye of -pocket expenses.

Done, this the i 329 of March, 1977.

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

SOU, DIST. ALA.

FILED AND ENTERED THIS THE

Gly > DAY OF MARCH

Zi

19.77, MINUTE ENTR

NO. L331

WILLIAM J. CONNOR, CLERK

DEPUTY CLERK

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

I

ATTACHMENT B

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v. CIVIL ACTION

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, et al., No. . 75-297~P

Defendants.

APPLICATION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL

Defendants City of Mobile, et al.., move this Court pursuant

to F.R.Civ.P, Rule 62{(c) for an order staying implementation of

this Court's Orders of October 21, 1976, and March 9 , 1977,

disestablishing the City's present form of government and in-

stituting a new mayor-council government, pending appeal to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and until

determination thereof, and shows to the Court as follows:

1. This Court's decision of October 21, 1976, was based

upon the legal premise that Plaintiffs were not required to prove

discriminatory intent or purpose to prevail under the Equal Pro-

tection Clause. Although the Supreme Court had recently held in

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), that such intent was

essential to proof that a facially neutral official action is

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment, this Court concluded that

"Davis was inapplicable to the case ait bar.

Subsequent decisions of the Supieme Court demonstrate conclu-

sively that this Court was mistaken in limiting Davis to its facts.

Proof of invidious intent or purpose is a universal requirement for

success of any Equal Protection Challenge to facially neutal official

ment Corp., U.S. y> 97:8. Ct. 555, 563 (1977); United

States v. Board of School Commissioners of Indianapolis, U.S.

. 150.8,%.%. 3508 (U.S. Jan. 25, 19277), vacating 541. ¥ 2d

1211 (7th Cir. 1976) in light of Davis and Arlington Heights;

United Jewish Organization of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, U.s.

y 45: 0.8.L.W. 422), 423) (U.S. Mar. 1, 1977) (Stewart, J.,

concurring).

2. This Court's denial of access holding was based primarily

upon its finding of black discouragement over the chance for politi-

cal victory in the face of putative racial bloc voting in Mobile.

Yet the Supreme Court has recently reaffirmed the principle of

Nevett v. Sides, 533 F. 24 1361, 1365 {5th Cir. 1975) that even ..

where racially polarized voting precludes election of blacks; this

result does not offend the Constitution and require restructuring

of the electoral system to permit blacks to be elected. United

Jewish Organizations, supra., 45 U.S.L.W. at 4227.

3. On these and other points, the City is likely to prevail

on appeal.

4. This Court has recognized that its ordering of a change in

the City's form of government raised serious constitutional issues

as to which reasonable men might reasonably differ. 423 F. Supp. at

404. Unless the Orders of this Court are stayed pending resolution

of these issues by the Court of Appeals, Defendant City and its

citizens will suffer grave and irreparable harm. Mobile's present

Commission Government will have been scrapped, its Charter completely

revamped under Order of this Court, and a newly enlarged body of

City officials elected--all before the lawful basis for such a

changeover has been scrutinized by the Court of Appeals.

ME a BE AND 0 HEIN FN 03 WE Salis Dwi a A eno BT 2, ne SIGE TNR 20

>. The change of government ordered by this Court will clearly

occasion considerable confusion and disruption to the City's normal

functions. But if the Court of Appeals reverses, as Defendants

submit it must, these disruptive effects will pale in comparison with

those caused by reinstituting Mobile's Commission Form of Government.

The Court-ordered August 1977 councilmanic and mayoral election will

be rendered nugatory, and the nine newly elected Councilmen and the

Mayor would be reduced, once again, to three Commissioners. Candidates,

black and white alike, who have campaigned at considerable expense,

both personal and financial, will find themselves vying once again

for City office. The interests of all parties to this action, and

the interest of the public at large, will be gravely disserved if

this Court of equity counkenances these results by failure to stay

its hand pending appeal.

6. The status quo to be preserved pendente lite is the main-

tenance of Mobile's City Commission form of government, effective

for 66 years.

WHEREFORE, Defendants City of Mobile, et al., respectfully

urge this Court to order that all elections and electoral changes

in Mobile's present scheme of government be stayed pendente lite

and that Its Orders of October 21, 1976 and March 9, 1977 be

vacated pendente lite.

Respectfully submitted,

OF COUNSEL:

Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, C. B. " Arendall, Jr.

Greaves & Johnston William C. Tidwell III

Post Office Box 123 Travis M. Bedsole, Jr.

Mobile, Alabama 36601 Post OFfFfice Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Legal Department of the

City of Mobile Pred G,., Collins, City Attorney

Mobile, Alabama 36602 S. R. Sheppard, Assistant City

: Attorney

Rhvne & Rhyne City Hall

400 Hill Building Mobile, Alabama 36602

Washington, D.C. 20005

: Charles S. Rhyne

William S. Rhyne

Donald A. Carr

Martin Vi. Matzen

400 Hill Building

Washington, D.C. 20006

’ ’ ; i ; :

By > ASE 1t- ! Arya

: 7

Attorneys for Defendants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that I have on this (pA day of

March, 1977, served a copy of the foregoing Application for Stay

Pending Appeal on counsel for all parties to this proceeding, by

mailing the same by United States mail, properly addressed, and

first class postage prepaid.

2x »

Ls ( 2 oni Ig

Attorney A

- ATTACHMENT C -

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TIE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al., )

Plaintiffs, )

: CIVIL ACTION

VS. )

NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, ef al., )

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS’

APPLICATION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL

Plaintiffs Wiley L. Bolden, et al., through thet

undersigned counsel, herein oppose the application for stay

pending appeal filed by defendants City of Mobile, et al. on

or about March 18, 1977. Defendants' application urges the

Court, pending final determination by the Fifth Circuit of

its pending appeals, to stay the Orders of October 21, 1976,

and March 9, 1977, and also to stay all elections, even those

under the present scheme of government. As grounds for their

opposition, plaintiffs would show as follows:

The Application for Stay Properly Should

be Submitted to the Fifth Circuit

1. The gravamen of defendants’ application is the contention

that this Court erred and probably will be reversed because it

held that Washington Vv. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), does not

apply to voter dilution cases and, in any event, did not require

judgment for the defendants in the instant case.

2. But defendants cannot seriously deny that this Court's

ruling on Washington Vv. Davis follows the existing law established

in the Fifth Circuit. Never: Vv. Sides, 533 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir.

1976); McGill v.Gadsden County Commission, 535 F.2d 277 (5th

Cir. 1976); and Paige v. Cray, 538 F.24 11038 (5th Cir. 1976),

are all post-Washington Vv. Davis voter dilution cases from

the Fifth Circuit. They uniformly reject defendants' argument

herein that Washington v. Davis and its progeny have under-

mined the voter dilution standards of Zimmer Vv. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1207 {5th Cir. 1973)(en banc), aff'd, East Carroll

Parish School Board v. Marshall, 96 8.Ct. 1083 (1976). This

Court's conclusions of law followed the teaching of Paige Vv.

Gray, supra, distinguishing racial gerrymandering cases, which

require proof of racial motivation, from voter dilution

decisions of the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circult, which

should be handled by the multifactor test enunciated in

Zimmer. 538 7.24 at 1110. As this Court noted, 423 F.Supp. at

395 n.10, Paige Vv. Gray, states in no uncertain terms that

"tlhe Zimmer standards ... are still controlling in this

circuit. 538 F.24 at 1110 n.4.

3. In light of the clearly established law in this

circuit rejecting defendants' argument that Washington v. Davis

requires in voter dilution cases proof of racial motivation

in the enactment of the electoral scheme, it would be in-

appropriate for this Court to stay its well-reasoned opinion

and injunction when defendants suggest no other ground on

which there is a likelihood of reversal by the Fifth Circuit.

Under these circumstances the Fifth Circuit is the appropriate

court to hear defendants' argument that it should reconsider

its en banc decision in Zimmer or that Zimmer and the other

Fifth Circuit voter dilution cases have been overruled by

Washington Vv. Davis.

4. For these controlling reasons, defendants’ application

for stay pending appeal should be denied. Thereafter, there

is ample time for defendants, if they choose, to press their

application for stay in the Court of Appeals.

5. Alternatively, plaintiffs would not object to the

Court granting a short-term temporary stay of its decrees

just long enough to provide defendants a reasonable

opportunity to have their motion for stay considered by the

Court of Appeals.

6. Although, in light of the settled law in the Fifth

Circuit concerning the standards governing voter dilution

cases the Court need not consider them, plaintiffs will

hereinafter state their additional grounds for opposing the

application for stay.

Other Grounds

7. Defendants have the burden of establishing the

existence of all four (4) factors for the granting of a

stay set out in Pitcher v. Laird, 415 F.24 743, 744 (5th Cir.

1969), and Belcher v. Birmingham Trust National Bank, 395 F.2d

635, 686 (5th Cir. 1968). Defendants have failed to carry

this burden.

-

I 8. There is no likelihood that the defendants-appellants

will prevail on the merits of this appeal. As stated above,

Paige v. Gray, Nevett v. Sides, and McGill v. Gasdsen County

Commission. reject the defendants' constitutional theory.

J

Nor have defendants alleged in their application there is any

likelihood this Court will be reversed with respect to its

findings of fact. The Fifth Circuit has said it will give

great deference to the district court's determination of

the Zimmer factors. See Paige Vv. Gray, supra, 538 F.2d at

111}.

9. By denying the suggestions of defendants herein

Appeal No. 76-3619, the Fifth Circuit has further indicated

its disinclination to reconsider the en banc Zimmer opinion.

10. Contrary to defendants' assertion, Village of Arlington

555, 50 L.Ed.2d 450 (1977), does not extend the scope of

the intent or purpose principles enunciated in Washington Vv.

Davis. If anything, the Supreme Court's discussion of

Washington v. Davis,and Arlington Heights represents yet

another opportunity the Court did not use to extend Washington

v. Davis, to Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971), White

v. Regester, 412 U.8. 755 (1973), or their progeny. As this

Court noted in its own opinion, reference to these voter

dilution cases by the Supreme Court is conspicous by its

absence. 423 F.Supp. at 394-95. Even if, arguendo, Washington

v. Davis were applicable to this case, defendants' application

does not allege that there is a substantial likelihood of

"n

reversal with respect to this Court's finding of "a 'current’

condition of dilution of the black vote resulting from

1

intentional state legislative inaction," by which this Court

reconciled its decision with the principles enunciated in

Washington v. Davis. 423 F.Supp. at 398.

11. Further, defendants’ application does nor allege

there is a likelihood this Court will be reversed with

respect to its ruling that plaintiffs have stated a cause

of action herein under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.5.C. §1973. Even if Washington v. Davis were to apply to

voter dilution cases, and even if the district court erred

in finding legislative intent to discriminate sufficient to

satisfy the standards of Washington Vv. Davis, plaintiffs are

not required to demonstrate discriminatory intent or motivation

to establish their right to relief under 42 U.S.C. §1973.

12. Contrary to defendants' assertions the Court should

not grant the stay requested on grounds that the appeal

7

presents ''movel questions.' Certainly the issues on appeal

in the instant case do not approach the degree of novelty

377 U.S. 533 (1964), wherein the Supreme Court announced

for the first time the substantive rule of one-man-one-vote,

yet refused a petition for stay pending appeal, see 377 U.S.

Supreme Court affirmed for the first time a finding of voter

dilution, yet had denied a petition for stay pending appeal,

405 U.S. 1201; or City of Richmond v. United Stares, 95 S.Ct.

2296 (1975), where, after the Court had denied a stay pending

appeal, 95 S.Ct. at 2300 n.4, it reversed a lower court

ruling that a critical annexation to the City of Richmond

had not unlawfully diluted the voting strength of blacks in

that city.

13. Contrary to defendants' assertion that "this Court

has taken the extraordinary step of proscribing [sic] in

every detail the government that must be used by the City,"

the Order of March 9, 1977, expressly provides that nothing

in it "shall prevent the defendants or Legislature of Alabama

from changing the powers, duties, responsibilities, or terms

of office of the city council and mayor, or changing the

boundaries of wards or districts, or changing the number of

wards," provided only that such changes comply with the

constitutional principals enunciated by the Court. Indeed,

it is the defendants' refusal to respond to the Court's

repeated invitations to seek to eliminate the racially

discriminatory features of the current election system that

has forced the Court to prescribe an interim form of govern-

ment.

14. In ordering a specific form of government to be

used by the City of Mobile pending affirmative action by

local politicians and the Legislature, the Court has carefully

avoided unnecessary interference with established state

policies. Its mayor-council plan is closely modeled after

plans prescribed by the Legislature for the other large

cities in Alabama. Defendants should be estopped from

attacking the ''strong mayor" features of the Court's plan

when at trial they in part based their defense on the

undesirability of the ''weak mayor" form provided by the general

Alabama law.

15. Further, defendants should be estopped from attacking

the Court's exercise of its equitable powers, given a finding

of unconstitutional voter dilution, to change the form of

government from a commission to a mayor-council in order to

utilize single-member districts. The inappropriateness of

imposing single-member districts on the commission form of

government was one of the principal elements of the defendants’

defense at the rial of his action.

16. A court-ordered change from one state-approved form

of municipal government to another state-approved form of

municipal government in order to provide a sound constitutional

remedy is no more radical or novel a judicial act than the

redrawing of municipal boundaries. The Supreme Court has made

it absolutely clear that a federal district court must

exercise its equitable powers in this manner whenever it

finds an unconstitutional abridgement of black citizens' voting

rights. Qolillion V. Lishifool, 364 U.S. 339 (1960). Indeed,

defendants do not suggest in their applicationfor stay that,

given the finding that the current election system is

unconstitutional, the Court should have adopted a different

remedial plan than the one it has approved.

17. The defendants have not proved or even offered

evidence in an attempt to prove that the City of Mobile will

suffer irreparable injury if the requested stay is not granted.

Indeed, according to newspaper reports the financial expense

of changing to the form of government and election system

prescribed by the Court will cost but a fraction of the amounts

defendants say they plan to spend to attack this Court's

decision. Plaintiffs demand strict proof of defendants' claim

of irreparable injury.

18. Defendants concede the injury that will be done

plaintiffs and the class of black voters they represent in

the event the Court grants the requested stay. Defendants

can only argue that the additional hardship to the plain-

tiff class pales in comparison with the discrimination they

have suffered for the past sixty-six (66) years. But the

Supreme Court has instructed the federal courts to weigh

unconstitutional impairments to fundamental rights of suffrage

with the highest of priorities. The right to an unimpaired,

equal vote is ''a fundamental political right, because

preservative of all rights." Reynolds v. Sims, supra, 377

0.8. "at 562, quoting Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 355, 370.

Plaintiffs’ right not to have their voting strength

unconstitutionally diluted far outweighs any administrative

inconvenience or expense the City might incur unnecessarily,

in the event this Court is reversed.

19. Defendants concede that the public interest is

served when its government is elected in a constitutional

fashion. Their only claim that a stay would serve the public

interest is based on the erroneous assertion that the majority

of Mobile's citizens favor the commission form of government

over the form of government and election system adopted by

the Court. In the first place, such an argument, even if

true, is fundamentally unsound: The Constitution of the United

States, which explicitly assigns a higher value to the

unimpaired voting rights of a minority than to the will of

the majority, best expresses the public interest. In any

event, there is no evidence in the record of this case to

show that the majority of Mobile citizens favor a city

commission ‘over a '"'strong mayor'' council form of government.

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray, for all the foregoing

reasons, that the Court deny defendants application for a

stay pending determination of an appeal to the Fifth Circuit.

ALTERNATIVELY, plaintiffs pray that the Court grant only

a temporary stay of its Orders for the short time necessary

for defendants to present their petition for a stay to the

Court of Appeals, if they choose.

Respectfully submitted this 23rd day of March, 1977.

CRAWFORD, BLACKSHER, FIGURES & BROWN

1407 DAVIS AVENUE |

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36603

-

-—

2 A a AO ae y By: WJ i Qash ite 4d 3/0. 'BLACKSHER

TARRY MENEFEE

EDWARD STILL, ESQUIRE

601 TITLE BUILDING

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA 35203

JACK GREENBERG, ESQUIRE

ERIC SCHNAPPER, ESQUIRE

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this the 23rd day of March,

1977, I served a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION

TO DEFENDANTS' APPLICATION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL, upon

counsel of record, C. A. Arendall, Esquire, Post Office Box

123, Mobile, Alabama 36601, Fred G. Collins, Esquire, City

Attorney, City Hall, Mobile, Alabama 36602 and Charles S.

Rhyne, faguive; 400 Hill Building, Washington, D. C. 20005,

by depositing same in United States Mail, postage prepaid

or by HAND DELIVERY.

ATTACHMENT D

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN LISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al., 0

Plaintiffs, x

CIVIL ACTION

VS. is

NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al., x

Defendants. *

TEMPORARY STAY OF INJUNCTION

This cause is before the Court on the application filed

March 18, 1977, by Defendants for an Order staying imple-

mentation of this Court's Orders of October 21, 1976, and

March 9, 1976, pending determination of an appeal to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. Defen-

dants' motion urges this Court to stay, pending outcome of

the appeal, not only the changes in form of City government

and method of election prescribed by the aforesaid orders,

but all elections under the present scheme of government

as well.

The sole contention advanced by the City Commissioners

in their motion as grounds for contending this Court's orders

are likely to be reversed on appeal is that recent Supreme

Court decisions demonstrate conclusively that this Court was

mistaken in its interpretation of Washington v. Davis, 426

U.5. 229 (1976), as it applies to this case. Buc this Court

is of the opinion that Fifth Circuit voter dilution cases

533. F.2d 13561 (5th Cir. 1976); McGill Vv, Gadsden County

Commission, 535 F.24 277 (5th Cir. 1978); and particularly

Paige v. Gray, 538 F.2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1976), have considered

and rejected the suggestion that Washington v. Davis has

undermined the continued viability of Zimmer Vv. McKeithen,

485: F.2d 1297 (5th Cixr. 1973) (en banc), aff'd, Fast Carroll

Parish School Board v. Marshall, 96.8.Ct. 1083 (1978), which

this Court so assiduously followed in reaching its conclusion

that the at-large election of the Mobile City Commission is

unconstitutional. "The Zimmer standards ... are still

controlling in this circuit.” Paige v. Gray, supra, 338 7.

2d at 1110 n.4.

Thus this Court is of the opinion that it would be

inappropriate for it to grant Defendants' application for a

stay pendente lite in the face of such clear directions from

the Court of Appeals. Furthermore, the Court is not impressed

with the City Commissioners' argument that "the majority"

of the citizens of Mobile will suffer irreparable injury

absent issuance of the requested stay. The Legislature of

Alabama has been in session three times since this action

began, and the Court has throughout its course taken pains

to urge the Commissioners and the Mobile County Legislative

Delegation to enact suitable changes in the election system

to remedy its present racially discriminatory features.

Yet the Defendants have refused to act. Even as the City

Commissioners approach this Court with their petition to

preserve the status quo, they have taken no initiative

toward proposing to the Legislature now in session some

alternative to the Court's plan that would still protect

black citizens' rights to equal representation in city

government.

However, this Court has Since the trial of this case

indicated its strong desire that the Court of Appeals be

given the opportunity to review the ''serious constitutional

issues" and any remedial plan imposed by this Court prior to

the 1977 City elections. Bolden v. City of Mobile, 423

F.Supp. 384, 404 (S.D. Ala. 1976). In addition, it has

been called to the Court's attention that election officials

may have difficulty meeting the May 1, 1977, deadline in the

March 9, 1977, order for redesignating certain new wards and

informing affected voters of the changes.

ACCORDINGLY, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED as

follows:

1. The time for accomplishing the tasks set out

in paragraph 7 of this Court's March 9, 1977, Order is

hereby extended from May 1, 1977, to June 1, 1977.

2. Defendants' application for a stay of the

October 21, 1976, and March 9, 1977, Orders pending final

determination of the appeal pending in the Court of Appeals

is HEREBY DENIED.

3. This Court's Orders of Geioher 21, 1976. and

March 9, 1977, are HEREBY TEMPORARILY STAYED until April

15, 1977, in order to enable Defendants, or any one or more

of them, to apply for and obtain a stay of said Orders of

October 21, 1976, and March ©, 1977, From the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. See Bush v. Martin, 224

F.Supp. 488, 5172 (5.0. Tex. 1953),

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

9... E

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY IL. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

O

N

ON

NH

OH

O

N

¥

Defendants.

SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT

OF DEFENDANTS' MOTION FOR STAY

XI. INTRODUCTION

Defendants have moved the Court to stay its Order of March

9, 1977, pending resolution of Defendants' appeal. The Court

heard oral argument on this motion on Wednesday, March 23, 1977,

and requested the parties to submit supplemental briefs by Friday,

April 1,:1977.

II. ARGUMENT

Whether injunctive relief granted by a district court should

be stayed pending disposition of the appeal of that order is a

decision entrusted to the sound discretion of the district court.

Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil §2904, at

316; see Beverly v. United States, 468 F.2d 732, 740 n.13

(5th Cir. 1972). The traditional considerations guiding the court

in the exercise of its discretion are (1) the likelihood of suc-

cess on the merits on appeal, (2) irreparable injury to the appli-

cant, (3) lack of substantial harm to other parties, and (4) the

public interest. E.g., Pitcher v. Laird, 415 F.24 743 (5th Cir.

1969); Belcher v. Birmingham Trust National Bank, 395 F.2d 685

{5th Cir. 1968); Wright & Miller, supra $2904, at 316. "If the

court is satisfied that these considerations or other relevant con-

siderations indicate that an injunction should be stayed pending

appeal, a stay will be granted."Wright & Miller, supra §2904, at

317 (emphasis added).

The Court is familiar with the last three considerations,

and is cognizant of the enormous confusion and disruption that

would occur if the form of the government of the City of Mobile

were changed only to have to be changed back should the appeal

be successful. Accordingly, and as Your Honor suggested, De-

fendants will direct this memorandum to the first of the four

considerations set out above.

As pointed out in Defendants' first memorandum, the first

consideration is subject to an aration or significant relaxa-

tion in cases of first impression or where novel remedies have

been ordered. This exception or relaxation is a practical neces-

sity since no district judge is likely to rule one way while ack-

nowledging that the losing side will likely prevail on the merits

on appeal. 7 Moore's Federal Practice para. 62.05 n.i5c.,

Moore cites as examples of stays granted in novel cases

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 456 F.2d 6 (4th

Cir. 1972) (school district merging case) and Rodriguez v. San

Antonio Independent School District, 337 F. Supp. 280 (W.D. Tex.

1972) (school property tax equalization case). Cases specifical-

ly recognizing the existence of an exception or significant relaxa-

tion of the first consideration where novel issues are involved

include Marr v. Lyon, 377 F. Supp. 1146 (W.D. Okla. 1974) and

Stop H-3 Association v. Volpe, 353 F. Supp. 14 (D. Hawaii 1972).

In Marr v. Lyon the court said:

The Court recognizes that the issues in this

case are novel and thus Defendants should be

given the benefit of the doubt as to whether

they are likely to succeed on appeal. . . .

377 F. Supp.at 1148.

Several factors bring this case within the novel case rule.

First, this case, along with the Shreveport case, is the first to

AE ts LW rere BR TR NI RA Tp Tn

apply voter dilution principles to at-large elections that are

an integral part of a commission form of government. Second,

this case is the first to consider in detail the applicability

of Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), to voter dilution

cases and the changes in the law, if any, resulting from that

Supreme Court decision.

Third, and most significant, this Court has ordered a

unique remedy; it is the first court, as far as Defendants are

aware, to order a city to change its form of government to remedy

the existence of (alleged) unconstitutional dilution resulting

from at-large election of city commissioners. This Court has

itself recognized the uniqueness of this remedy and the existence

of substantial ground for difference of opinion as to its validity

by certifying its October 21, 1976, Order for interlocutory

appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1292(b). C.f. Brown v. Texas and

1975

Pacific R.R. Co., 392 F. Supp. 1120, 1126 (W.D. La./) (court certi-

fied interlocutory appeal and stayed further proceedings pending

resolution of appeal); Fawvor v. Texaco, inc., 387 FP. Supp. 626,

629 (E.D. Tex. 1975) (court certified interlocutory appeal and

stayed further proceedings pending resolution of appeal).

A review of the case law indicates that this Court has ample

discretion in the circumstances of this case to grant the stay

requested. In Corpus Christi School District v. Cisneros, 404

U.S. 1211 (1971), the district court ordered extensive desegrega-

tion of a school district bak stayed its order pending appeal to

the Fifth Circuit. The court of AoneaY Shin vacated the stav even

though the appeal had not yet been heard. On petition by the

school district, Justice Black of the Supreme Court reversed the

Fifth Circuit and reinstated the district court's stay, sayng:

It is apparent that this case is in an

undesirable state of confusion and presents

a i Ch rp ee fe Te a 3 FE BIER SE A PI nce fe a me 5 4 SPI 0 037 ASI = Tho So

questions not heretofore Passed upon

by the full Court, but which should be.

Under these circumstances, which pre-

sent a very anomalous, new, and confus-

ing situation, I decline as a single

Justice to upset the District Court's

stay and, therefore, I reinstate it . . . .

The stay will be reinstated pending action

on the merits in the Fifth Circuit or

action by the full Court.

404 U.S. at 1212.

In Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, supra,

the district court ordered extensive merger of school districts

to eliminate segregation. The Fourth Circuit granted a stay of

the district court's order pending resolution of the appeal on the

merits. whe cours of appeals ordered the defendants to continue

planning and preparation for a merger of the school districts

"to the end that there will no unnecessary delay in the implemen ~

tation of the ultimate step . . . in the event that the order is

affirmed on appeal," but stayed actual implementation of the

merger. 456 F.2d at 7. The course of action tentatively indicated

by Your Honor in this case is quite similar to that adopted in

Bradley. Defendants would be ordered to make all preparation and

plans for holding of mayor-council elections so that all unneces-

sary delay is avoided if Your Honor's decision is affirmed on

appeal, but actual implementation of that order would be stayed

until the appeal is resolved.

In Medley v. School Board of the City of Danville, Virginia,

350 F. Supp. 34 (W.D. Va. 1972), remanded on other grounds, 482

F.2d 1061 (4th Cir. 1973), the district court ordered steps to

eliminate segregation in public schools, but recognized the costs

and extensive disruption that would be caused by its order, stayed

the order pending resolution of the appeal. The district court

granted the stay even though it had ruled against defendants on

the substantive issues and had not made a finding that defendants

were likely to prevail on papeal.

It should be noted that Defendants here are not seeking an

injunction pending appeal even though the court has denied in-

junctive relief on the merits, but rather are, in order to pre-

serve the status quo, seeking a stay of the affirmative injunc-

tive relief ordered by the Court. Compare Pitcher v. Laird,

supra, with Stop H-3 Association v. Volpe, supra at 16 (stay

appropriate to preserve status quo). It is appropriate for the

district court to give more or less weight to each of the four

considerations for the exercise of its discretion depending on

the circumstances existing in the case and the court's knowledge

of the particular problems and cirsumstances existing. There is

no requirement that before the district court can grant a stay it

must in every case find the 100% existence of each of the four

considerations. See Belcher v. Birmingham Trust National Bank,

supra; Marr v. Lyon, supra (recognizing relaxation of first consi-

deration in novel cases); Stop H-3 Association v. Volpe, supra

(recognizing relaxation of first consideration in cases charting

new ground).

In Belcher, the Fifth Circuit found that the fourth element,

the public interest, had "little bearing” in a case between private

parties, distinguishing situations where "the public interest fac-

tor is 'crucial' in [for example] litigation over regulatory

statutes « . « "395 F.2d at 685. Clearly, the FPifth Circuit is

recognizing that the weight to be given to each of the four con-

siderations depends upon the circumstances of the particular case.

It would have been pointless for the Fifth Circuit in Belcher, and

in courts in many other cases, to continue to examine the other

three considerations if the rule were that a failure to establish

the probability of success on appeal precluded issuance of a stay.

IIT. CONCLUSION

In light of the circumstances of this dase, particularly

the confusion and dislocation unavoidably resulting from a

change in city government and the admitted novely of the remedy

ordered, this Court should exercise its discretion to stay its

Order of March 9, 1977, pending resolution of Defendants' appeal.

Respectfully submited on this lst day of April, 1977.

OF COUNSEL:

Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, C. B. Arendall, Jr.

Greaves & Johnston William C. Tidwell, IIT

Post Office Box 123 Travis M. Bedsole, Jr.

Mobile, Alabama 36601 Post Office Box 123

=, Mobile, Alabama 36601

Legal Department of the

City of Mobile Fred G. Collins, City Attorney

Mobile, Alabama 36602 City Hall

: Mobile, Alabama 36602

Rhyne & Rhyne

400 Hill Building Charles S. Rhyne

Washington, D. C. 20006 William S. Rhyne

Donald A. Carr

Martin W. Matzen

400 Hill Building

Washington, D.C. 20006

By: (ono) Sra

Attorneys for Defendants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that I have on this /27 day of april,

1977, served a copy of the foregoing Supplemental Memorandum in

Support of Defendants' Motion for Stay on counsel for all parties

to this proceeding, by mailing the same by United States mail,

properly addressed, and first class postage prepaid.

Attorney /

ATTACHMENT F

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

CIVIL ACTION

VS.

No. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, et al.,

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' MEMORANDUM BRIEF OPPOSING

APPLICATION FOR STAY PENDING APPEAL

Plaintiffs Wiley L. Bolden, et al., pursuant to the Court's

instructions from the bench on March 23, 1977, herein submit

authorities and suggestions supplementing those in their

opposition to Defendants' Application For Stay, filed March

23,:1977.

The parties agree that the principles of Pitcher v. Laird,