New York City Police Department Civil Service Entrance and Promotion Exams Challenged in Suit

Press Release

March 3, 1972

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. New York City Police Department Civil Service Entrance and Promotion Exams Challenged in Suit, 1972. ca724fcb-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cbaecf07-cef4-463c-b5ba-e66a66951596/new-york-city-police-department-civil-service-entrance-and-promotion-exams-challenged-in-suit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

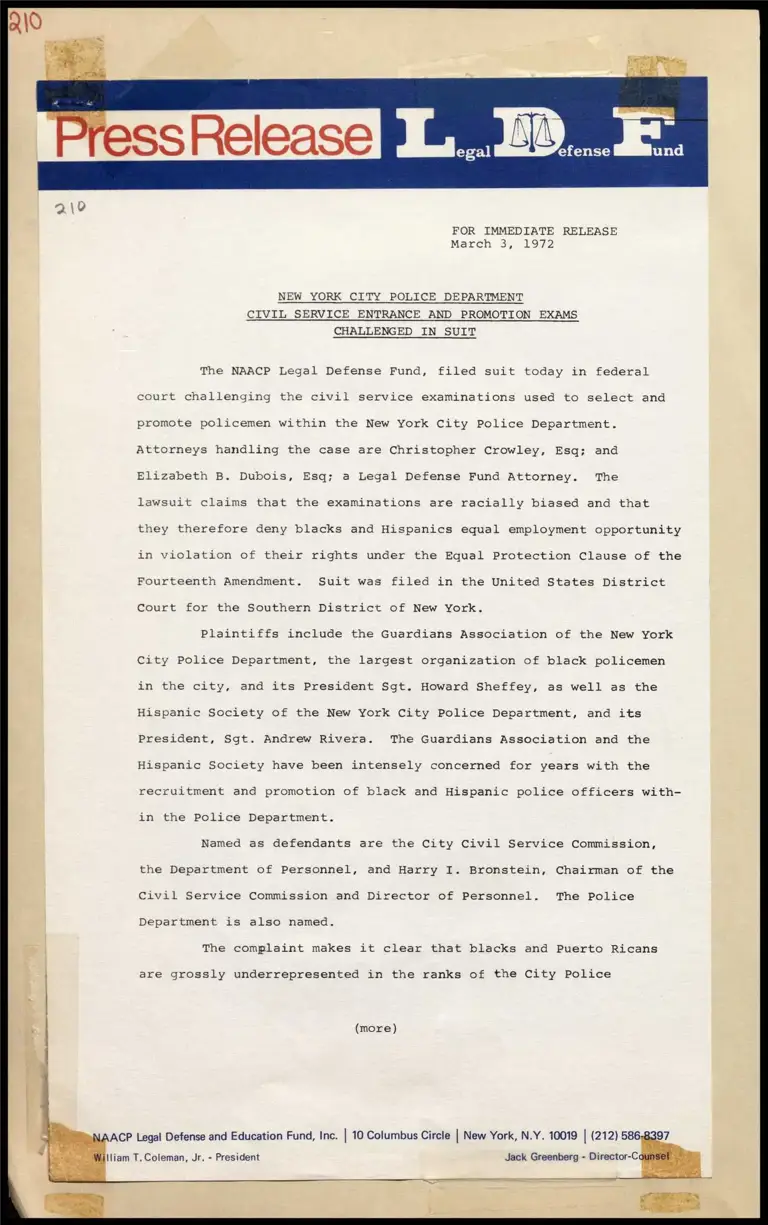

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 3, 1972

NEW _YORK CITY POLICE DEPARTMENT

CIVIL SERVICE ENTRANCE AND PROMOTION EXAMS

CHALLENGED IN SUIT

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund, filed suit today in federal

court challenging the civil service examinations used to select and

promote policemen within the New York City Police Department.

Attorneys handling the case are Christopher Crowley, Esq; and

Elizabeth B. Dubois, Esq; a Legal Defense Fund Attorney. The

lawsuit claims that the examinations are racially biased and that

they therefore deny blacks and Hispanics equal employment opportunity

in violation of their rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Suit was filed in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York.

Plaintiffs include the Guardians Association of the New York

City Police Department, the largest organization of black policemen

in the city, and its President Sgt. Howard Sheffey, as well as the

Hispanic Society of the New York City Police Department, and its

President, Sgt. Andrew Rivera. The Guardians Association and the

Hispanic Society have been intensely concerned for years with the

recruitment and promotion of black and Hispanic police officers with-

in the Police Department.

Named as defendants are the City Civil Service Commission,

the Department of Personnel, and Harry I. Bronstein, Chairman of the

Civil Service Commission and Director of Personnel. The Police

Department is also named.

The complaint makes it clear that blacks and Puerto Ricans

are grossly underrepresented in the ranks of the City Police

(more)

ACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

\liam T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-C

CIVIL SERVICE ENTRANCE EXAMS PAGE 2

Department. Thus while 37% of the City population is black and

Hispanic, only 1.4% of the Police Department's captains, 2.6% of

its lieutenants and 4.7% of its sergeants are from those minority

groups. Blacks and Hispanics make up only 8.7% of the entire

Police Department.

Plaintiffs contend that the principal barrier to the

appointment and promotion of qualified blacks and Hispanics in the

Police Department is the examination system administered by the City

Civil Service Commission. The complaint alleges that these examina-

tions are racially biased and, therefore, that they discriminate

against minority group members for reasons which have nothing to do

with their ability to perform as police officers.

Plaintiffs contend that the examinations are not job-related

and do not test for merit and fitness, as required by law. They

charge that the examinations place a premium on rote memorization,

and paper and pencil test-taking skills, rather than sound judgment

and the ability to lead. The complaint quotes a recent statement

of Police Commissioner Patrick V. Murphy, that the Civil Service

System has "excluded minorities" and has "tragically advanced some

men to captain who cannot or will not lead."

Lawyers handling the case stated that the object of the

lawsuit was to compel the Civil Service System to develop a true

merit system in place of the present system which discriminates

irrationally against minorities.

The lawsuit demands that the Civil Service System develop

new examination procedures for the selection and promotion of

policemen.

LDF Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg stated that this lawsuit

(more)

CIVIL SERVICE ENTRANCE EXAMS PAGE 3

represents another step in LDF's on-going campaign against

employment discrimination. The Fund handled the case of Griggs v.

Duke Power which resulted in the U.S. Supreme Court's recent land-

mark decision in thearea of private discrimination, and is now

responsible for some 150 employment discrimination cases around the

country. Mr. Greenberg stated that the Fund "is seriously concerned

with the problem of employment discrimination by public agencies and,

in particular, with the biased and irrational manner in which many

civil service examinations systems operate."

The Fund brought the case against the Board of Examiners

which resulted in a federal court decision last summer declaring

unconstitutional the examinations used to select principals and

other supervisors in the New York City School System. That case is

now pending on appeal in the Second Circuit. The Fund is also

involved in suits challenging police department selection procedures

in some half-dozen cities.

=290- 5

For further information contact: Attorney Christopher Crowley HA -2 340

Attorney Elizabeth B. Dubois or

Abeke Foster, Public Information

(212) 586-8397

NOTE: Please bear in mind that the LDF is a completely separate and

distinct organization even though we were established by the

NAACP and those initials are retained in our name. Our correct

designation is NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,Inc.,

frequently shortened to LDF.