Waisome v. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Brief for Defendants-Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 17, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Waisome v. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Brief for Defendants-Appellees, 1991. b4c99d28-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cbbc1357-af10-46db-852b-6cd550761671/waisome-v-port-authority-of-new-york-and-new-jersey-brief-for-defendants-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

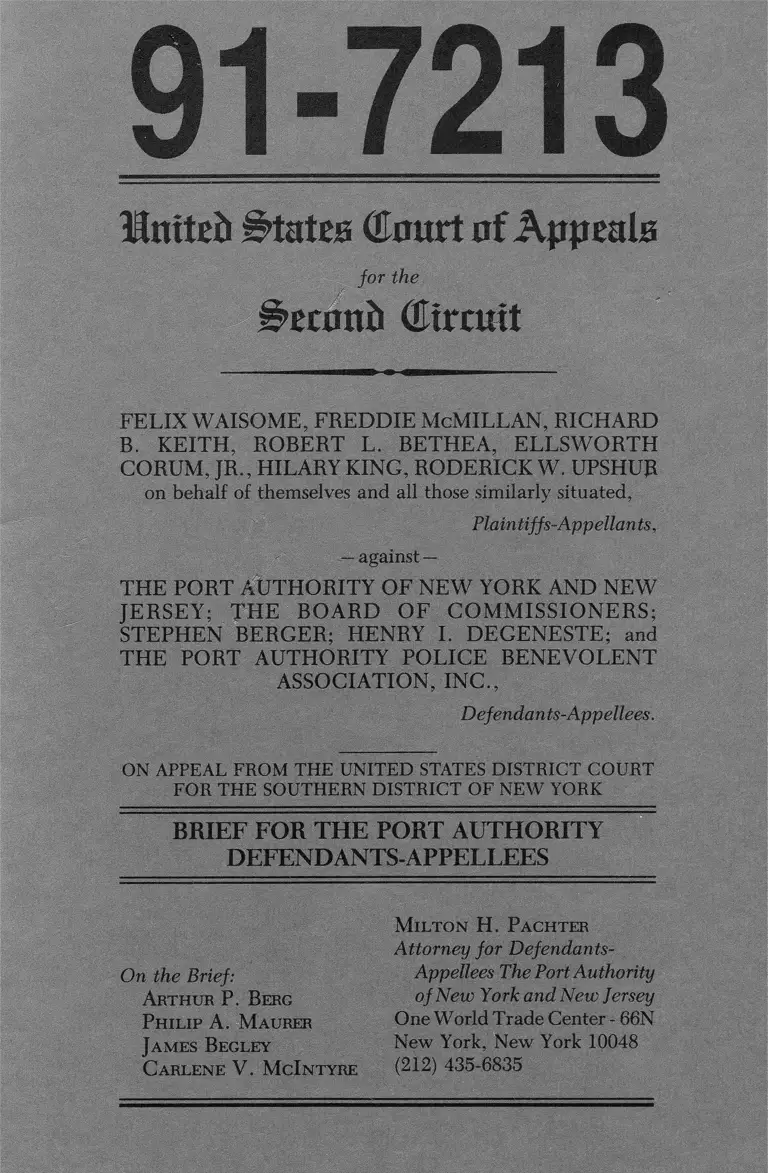

91-7213

llniteii States Court of Appeals

fo r the

&edml» Circuit

F E L IX W A ISO M E , F R E D D IE M cM IL LA N , R IC H A R D

B. K E IT H , R O B E R T L . B E T H E A , E L L S W O R T H

C O R U M , JR ., H ILA RY K IN G , R O D E R IC K W . UPSHUR

on behalf of themselves and all those similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

— against —

T H E P O R T A U T H O R IT Y O F N EW YO RK AND N E W

J E R S E Y ; T H E B O A R D O F C O M M IS S IO N E R S ;

ST E P H E N B E R G E R ; H EN RY I. D E G E N E S T E ; and

T H E P O R T A U T H O R IT Y P O L IC E B E N E V O L E N T

A SSO C IA TIO N , IN C .,

Defendants-Appellees,

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF FOR THE PORT AUTHORITY

DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

On the Brief:

Arthur P. Berg

Philip A. Maurer

James Begley

C arlene V . McIntyre

Milton H. Pachter

Attorney for Defendants-

Appellees The Port Authority

of New York and New Jersey

One World Trade Center - 66N

New York, New York 10048

(212) 435-6835

1

T A B L E O F C O N TEN TS

Page

Table of Authorities................................. iii

Statement Of The Issue Presented For Review v

Statement Of The Case.................... 1

A. Nature of the Case and Course of

Proceedings............................................ 1

B. Statement of the Facts ............................... 3

1. The Sergeant’s Promotion

Examination Process.......................... 3

2. EEO C Administrative Proceedings . . 6

3. The District Court’s Decision . . . . . . . 7

Summary Of The Argument ............................. . 9

Argument

The Selection Process For Police Sergeant

Had No Disparate Impact On Black

Candidates ........................................................ 12

A. Standard of Review and Proceedings

Under Review............................... 12

B. Applicable Legal Standards............... 13

C. The Multi-Component Examination

Process Had No Disparate Impact on

Black Candidates................................. 20

1. The Written Exam ination.................... 20

2. The Oral Examination and the

Performance Appraisal.......................... 27

3. The Eligibility L is t ......................... 28

Conclusion ................................................................. 37

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Bilingual Bicultural Coalition on Mass

M edia, Inc. v. FC C , 595 F.2d 621 (D.C.

Cir. 1978) ............................. ............... ............. 17, 21

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. M em bers o f

Bridgeport Civil Sew . C om m ’n, 482 F.2d

1333 (2d Cir. 1973) ......................................... 23

Bushey v. New York State Civil Service

C om m ’n, 733 F.2d 220 (2d Cir. 1984) . . . 14, 18, 22

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) . 15

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, A ll U.S. 317

(1986) ........................................ 12

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982) . . 10, 19, 20,

21, 24, 25

G ilbert v. City o f L ittle R ock, A rk., 722

F.2d 1390 (8th Cir. 1983).................. 34, 35

Guardians Assn v. Civil Service C om m ’n,

630 F.2d 79 (2d Cir. 1980)........................... 15 n.8, 18,

19, 23

H azelw ood School District v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977)............. .......................... 15

Jackson v. Nassau County Civil Service

C om m ’n, 424 F.Supp. 1162 (E.D.N.Y.

1976) ............................................................... .... 22, 23

K irkland v. New York State Dept, o f

C orrectional Services, 374 F.Supp. 1361

(S.D.N.Y. 1974), a f f ’d, 520 F.2d 420 (2d

Cir. 1975), cert, denied , 429 U.S. 823

(1976) ................ .......................... ........................ 23, 24

IV

Cases Page

K irkland v. New York State D ept, o f

C orrectional Services, 711 F.2d 1117 (2d

Cir. 1983) ..................................................... .. 29, 30, 34

Ottaviani v. State U. o f New York at New

Paltz, 875 F.2d 365 (2d Cir. 1 9 8 9 )........... 8, 16,

16 n.9-10,

17, 26, 30

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273

(1982)................................................................... 12

Teal v. Connecticut, 645 F.2d 133 (2d Cir.

1981) ................................................................... 18

U nderwood v. State o f New York, 28

F .E .P . 922 (S.D.N.Y 1980)............. ............. 35 n.16

W ade v. New York Tel. C o., 500 F.Supp.

1170 (S.D.N.Y. 1980) .................................... 33

W ards C ove Packing C o., Inc. v. Frank

Antonio, 109 S.Ct. 2115 (1 9 8 9 ).................. 13, 14 n.7,

16 n.9

Watson v. Fort W orth Bank and Trust, 487

U.S. 977 (1988)................................................. 13-14 ,15 ,

16 n.9-10,

18, 21

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981

(West 1981 & Supp. 1 9 9 1 ) ........................... 2

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1983

(West 1981 & Supp. 1 9 9 1 ) ........................... 2

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Tit. V II, 42

U .S.C. §2000d (West 1981 & Supp. 1991) 2

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Tit. V II, 42

U .S.C. §2000e (West 1981 & Supp. 1991) 2

Other Authorities:

29 C .F .R . §1607,4D (1 9 8 8 )............................. 29, 31

Rniteii States (Court of Appeals

fo r the

i>ec0ni> (Circuit

FE LIX WAISOME, FRED D IE McMILLAN, RICHARD

B. KEITH, ROBERT L. BETHEA, ELLSW ORTH

CORUM, JR ., HILARY KING, RODERICK W. UPSHUR

on behalf of themselves and all those similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

— against —

THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NEW YORK AND NEW

JE R S E Y ; TH E BOARD O F CO M M ISSIO N ERS;

STEPHEN BERG ER; HENRY I. D EGEN ESTE; and

THE PORT AUTHORITY POLICE BENEVOLENT

ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Defendants-Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT O F NEW YORK

BRIEF FOR THE PORT AUTHORITY

DEFEND ANTS-APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Nature o f the Case and Course o f Proceedings

In this case, plaintiffs-appellants, individual Black police

officers who are employed by the Port Authority and a class

of similarly situated officers whom they represent, challenge,

2

as discriminatory, a selection process used by the Port

Authority to make promotions to the rank of Sergeant.

Plaintiffs are currently employed as police officers by the

Port Authority and now represent a class consisting of all

Black police officers who took the promotion examination.

They claimed below that defendants-appellees1 have

violated Tide VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2000d, §2000e, e tseq . (West 1981 & Supp. 1991), as well

as the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981 and §1983.

Plaintiffs’ district court papers sought declaratory relief

based on the defendants’ alleged maintenance of an

unlawful employment practice and the administration of

unlawful selection criteria. Specifically, in their original

complaint, they alleged that the Port Authority violated

plaintiffs’ rights by utilizing, as a prerequisite for promo

tion to the rank of Sergeant, a selection procedure which

had an adverse impact on Black applicants and which had

not been demonstrated to be job-related. In their amended

complaint, plaintiffs added a claim that the selection pro

cess had intentionally discriminated against Black ap

plicants (J.A, 20).2 Before filing their amended complaint,

plaintiffs also served and filed a motion seeking preliminary

injunctive relief.

By endorsement dated October 14, 1988, the district

court denied plaintiffs’ motion for preliminary injunctive

relief, ruling that plaintiffs had failed to demonstrate

1 Plaintiffs have also named as a defendant the Port Authority

Police Benevolent Association, Inc. (hereinafter “PBA”), the union

which is the collective bargaining agent for Port Authority police

officers and which is represented in these proceedings by its own

counsel.

2 “J.A .” refers to the joint appendix filed by plaintiffs in this Court.

“Br.” refers to the opening brief filed by plaintiffs in this Court.

3

irreparable harm. On November 21, 1989, the court ap

proved a stipulation between the parties whereby the plain

tiffs agreed to discontinue their claims for intentional

discrimination and the defendants agreed that if the ex

amination was found by the court to have an adverse im

pact on Black applicants, they would not seek to litigate

the validity of the examination (J.A. 80-81).3 The parties

cross-moved for summary judgment agreeing that, despite

slight differences in methodology and computation, the

underlying facts were essentially undisputed. Therefore,

the parties filed statements consisting of the material facts

not in dispute in accordance with the rules of the court

(J.A. 82).

B. Statem ent o f the Facts

1. The Sergeant’s Prom otion Exam ination Process

On July 11, 1986, the Personnel Department of the Port

Authority announced the commencement of an examina

tion process for the purpose of establishing a vertical list

of Port Authority police officers eligible for promotion to

the rank of Sergeant (J.A. 83; Promotion Examination An

nouncement, No. 86-31, J.A. 126). In order to be eligible

to participate, candidates for promotion were required to

have at least two years in grade (including Academy train

ing) as a Port Authority police officer and were also re

quired to be actually employed as a police officer as of the

first date of the written test (J.A. 126).

The selection process for placement on the Eligible List

consisted of three basic components. The first component

consisted of a written test, to “measure knowledge of law,

3 On November 2, 1988, the district court granted the motion to in

tervene as defendants filed by Port Authority police officers Joseph

Leather, et al.

4

police supervision and social and psychological problems

in police work.” The second component was an individual

oral test to “measure judgment and personal qualifica

tions.” Finally, the third component was a performance

appraisal consisting of two parts — a supervisory perform

ance rating and a score based on the candidate’s attend

ance record (J.A. 126, 127).

The written examination for police officers was ad

ministered on September 6, 1986, and a make-up test was

administered on September 20, 1986 (J.A. 85). In mid-

November of 1986, candidates were notified of their scores

on the written component. Candidates were given until

December 19, 1986 to appeal the results of the written ex

amination and, by January 8, 1987, all the appeals taken

were completed (J.A. 85). The individual oral examina

tions were administered between January 26, 1987 and

February 13, 1987. The performance appraisal process

began on March 2, 1987 and was completed by March 20,

1987 (J.A. 85). The performance appraisal ratings were

factored into the total test score.4 The eligibility list was

issued on March 30, 1987 (J.A. 86).5

The passing score for the written examination was 66 %

and the passing score for the oral was 69.5% (J.A. 86, 90).

A passing score on the written was needed to proceed to

the oral examination and a passing score on the oral was

needed to proceed to the performance appraisal (J.A. 86,

4 There was an identical selection process commenced for detectives

who desired to be promoted to the rank of sergeant (J.A. 134). That

process also consisted of a written examination, oral examination and

performance appraisal component. Successful detective candidates

were placed on the same Eligible List as successful police officers.

5 A revised eligibility list was issued December 4, 1987 after an Ap

peals Board resolved seventeen appeals from candidates on the per

formance evaluation process (J.A. 97).

5

90). The weights accorded to the three components of the

selection process were 55 % for the written examination,

35% for the oral examination and 10% for the perfor

mance appraisal process (J.A. 84-85).

A total of 617 police officers (including detectives) par

ticipated in the selection process. Of the total number of

participants, 508 were White and 64 were Black (J.A. 86).

A total of 539 participants passed the written examination.

Of those who passed the written, 455 were White and 50

were Black (J.A. 86, 188).

Of the 539 successful candidates on the written examina

tion, 531 participants took the oral examination. Of those

who either decided not to or could not proceed further,

7 were White and 1 was Black (J.A. 89-90, 188). On the

written examination, the pass rate for Blacks (78.13 %) was

87.2% of the pass rate for Whites (89.57 %) (J.A. 124,197).

Of the 531 participants who took the oral examination,

448 participants were White and 49 participants were

Black. Of the 531 participants, 310 passed the oral exam.

Of those who passed, 258 were White and 33 were Black

(J.A. 90, 188). On the oral examination, the Black pass

rate (67.35%) was 116.97% of the White pass rate (57.58)

(J.A. 90, 188).

Of the White candidates who participated in both the

written and the oral examinations, 51.7% passed (258

divided by 499) and of those Black candidates who par

ticipated in both oral and written examinations, 51.56%

(33 divided by 64) passed (J.A. 125, 188).

Of the 617 participants who began the selection process

(508 Whites and 64 Black), 310 participants completed the

process and were included on the Eligible List (J.A. 91,

97-101). Of the 310 candidates included on the Eligible

List, 258 were White and 33 were Black (J.A. 92, 125).

6

When the list expired on March 30, 1990, 79 promo

tions had been made from the list and the 85th candidate

on the list had been reached.6 The promoted officers in

cluded 70 Whites, 5 Blacks, 2 others and two “grand

fathered” candidates who were White (J.A. 124, 189).

2. EEO C Administrative Proceedings

The Eligible List was issued on March 30, 1987. All

named plaintiffs filed charges of discrimination with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). In

each case, a determination was made by the EEOC that

each charging party had not been the subject of discrimina

tion in violation of Title V II. The letters to all plaintiffs

were dated December 3, 1987.

Mr. Felix Waisome filed a charge of discrimination on

June 8, 1987. He passed the written test with a score of

90, but failed the oral by one-half of a point (J.A. 95).

Mr. Freddie McMillan filed his charge on June 10, 1987.

He passed both the written exam (score of 80) and the oral

(score of 77.5). However, he complained that his combined

scores placed him near the bottom of the Eligible List (No,

195) (J.A. 95).

Mr. Richard B. Keith filed his charge on July 20, 1987.

He passed the written test (score of 88) and failed the oral

(score of 64.5) (J.A. 95).

Mr. Robert L. Bethea filed his charge on July 14, 1987.

He passed the written (score of 68) and the oral (score of

94). His claim of discrimination was based on his position

on the Eligible List (No. 221) (J.A. 95).

6 Two candidates whose rankings were high enough to entitle them

to promotions retired and four other candidates, all White, refused

promotions and remained on the force (J.A. 91-92).

7

Mr. Ellsworth Corum, Jr. filed his charge on July 27,

1987. He passed the written examination (score of 86) but

failed the oral (score of 68) (J.A. 95).

Mr. Hilary A. King filed his charge on July 30, 1987.

He alleged that he passed both the written and oral. He

based his claim of discrimination on his position near the

bottom of the Eligible List (No. 180) (J.A. 95).

Mr. Roderick W. Upshur filed his charge on September

30, 1987. He failed the written test (score of 58). He is the

only named plaintiff that failed the written component of

the selection process (J.A. 96).

3. The District C ourt’s Decision

After outlining the essential facts, the district court (Duffy,

J.) initially determined that it would be appropriate to cer

tify a class, a determination which defendants-appellees do

not contest on appeal. On the merits, the court determined

that plaintiffs had not met their burden of demonstrating

that the examination process had an adverse impact on

Black candidates. The court then separately analyzed

plaintiffs’ claims that the written component of the selec

tion process as well as the overall process had an adverse

effect on Black candidates. The court noted that, in order

to prevail, plaintiffs were bound to demonstrate that “the

disputed component denied minorities, to a dispropor

tionate degree, the opportunity to be promoted” (J.A. 193).

Comparing the pass rates on the written component, the

court noted that it was undisputed that, using standard

deviation analysis as a unit to measure the statistical

significance of those differences, the differences were

statistically significant at 2.68 standard deviations.

However, the court also noted that the Second Circuit had

“rejected the efficacy of a ‘minimum threshold level of

8

statistical significance’ for determining whether the plain

tiff has established a prim a facie case of discrimination.

Ottaviani v. State Univ. o f New York at New Paltz, 875

F.2d at 373.” (J.A. 195). Following Ottaviani, which had

drawn from recent Supreme Court pronouncements on this

issue, the court below noted that statistical analysis was

not the only method adopted by the Court in order to

determine whether such differences are legally significant.

The court observed that “[i]n order to determine the im

portance or magnitude of the differences, the statistical

data must be analyzed in the context of the situation in

practical terms” (J.A. 196).

The district court used two additional measures to deter

mine whether the difference in pass rates on the written

exam was practically significant. First, the court referred to

the EEOC guidelines or the “four-fifths rule” (80 % rule con

tained in those guidelines). Under that rule, a selection rate

for any protected group which is less than four-fifths the

selection rate for the group with the highest rate is general

ly determined by the federal rules to be evidence of adverse

impact. Applying this rule, the court noted that the pass

rate for Blacks on the written component of the examina

tion was 87.2 % of the pass rate for White candidates. Ad

ditionally, the court observed that while a test for statistical

significance yielded a result of 2.68 standard deviations,

had two additional Black candidates passed, the difference

would no longer be statistically significant (J.A. 198).

Further, the court below addressed plaintiffs’ claim that

mathematically a score of 76 was needed on the written

component to qualify an individual for promotion, and

a comparison between the proportion of Blacks and Whites

achieving such a score was statistically significant at 2.68

standard deviations. The court observed that while some

Blacks performed well on the written component, as a

group Blacks scored lower than Whites. However, the

9

court held that this evidence, standing alone, did not in

dicate adverse impact because a number of Blacks per

formed better than Whites on the balance of the examina

tion, and a comparison of overall pass rates on the entire

examination revealed no statistical disparity (J.A. 199-200).

Finally, applying a test of statistical significance, a test

which the court below held was appropriate due to the

small number of promotions involved, the district court

rejected plaintiffs’ claim that the overall promotion rates,

as measured by the overall ranks of all candidates on the

eligibility list, demonstrated adverse impact. The court

observed that an application of standard deviation analysis

revealed a difference in selection rates of 1.34 standard

deviations, a number well below the level of 2 or 3 stan

dard deviations which constitutes statistical significance

(J.A. 200). Based on its determination that plaintiffs had

failed to present evidence of a “sufficiently substantial dif

ference” between W hite and Black selection or

performance rates, the court granted judgment in favor

of the defendants and this appeal followed.

SUM M ARY O F T H E A RGUM ENT

The Supreme Court has indicated that Title VII covers

intentional discrimination as well as facially neutral

employment practices which have a significant adverse im

pact on protected groups and are, therefore, regarded as

the functional equivalents of intentional discrimination.

Under this latter theory, the sole issue presented to this

Court for review is whether the examination process used

by the Port Authority, until March of 1990, for the pro

motion of police officers to the rank of Sergeant had an

adverse impact on Black candidates for promotion. The

district court, in disposing of cross-motions for summary

judgment, determined that the plaintiffs failed to

10

demonstrate a “sufficiently substantial difference” in the

White and Black selection rates or performance rates which

would warrant an inference of discrimination under Title

V II. We submit that, on the material facts of this case,

which all parties agree are not in dispute, the district court

was plainly correct.

First, while the Supreme Court, in Connecticut v. Teal,

457 U.S. 440 (1982), indicated that an examination which

operates as a pass/fail barrier and which, therefore, ex

cludes protected candidates from further participation in

the examination process must be separately analyzed, ap

plication of Teal to the facts of this case would indicate

that no such barrier was in operation. In the instant case,

unlike the situation in Teal, a comparison of pass/fail rates

for the written test component reveals that the Black pass

rate is 87.2% of the White pass rate. Therefore, here, a

comparison of pass rates for the written test component

satisfies the four-fifths rule, set forth in the EEO C guide

lines, which is used as a benchmark by courts, including

the Supreme Court in Teal, to measure the significance

of such differences.

Plaintiffs, however, contend that a higher score than the

established score on the written examination was needed

in order to assure a position on the eligibility list within

striking range for promotion and that the difference in

Black and White performance at the higher passing score

reveals adverse impact. Plaintiffs’ analysis is flawed. Com

mon sense dictates that, when, as here, a multi-component

examination is involved, any legally significant disparity

in performance by protected groups on one component will

be reflected in the aggregate results achieved by those in

dividuals on the entire examination. Here, while Whites

scored better than Blacks on the written component, Blacks

scored better than Whites on the oral examination. Most

importantly, a significant number of Blacks performed well

11

enough on the entire process that an analysis of the overall

promotion rates reveals no statistical disparity between the

number of Whites and the number of Blacks promoted.

Second, the selection process resulted in the promotion

of only 79 individuals (5 Blacks, 70 Whites, 2 others and

2 grandfathered candidates). As the district court noted,

because of the small numbers involved, it is appropriate

in this case to look at the statistical significance of the dif

ference in the overall promotion rates in order to deter

mine whether the selection process had an adverse impact.

Applying standard deviation analysis, however, the dif

ference in selection rates is 1.34 standard deviations, a

measure well below the 2 or 3 standard deviations men

tioned most often in court decisions as constituting

statistical significance.

Moreover, while plaintiffs argue that the court below

committed legal error in failing to compare the relative

ranks of Black and White candidates on the resulting

eligibility list, we maintain that plaintiffs’ argument on

these facts is misplaced. Contrary to plaintiffs’ emphasis

on relative rank, Title VII does not require that employers

equalize scores or equalize the probabilities that all in

dividuals in a protected class will be promoted. Rather,

it requires that members of protected groups enjoy relative

ly equal opportunities to be promoted. Here, there were

proportionally equal numbers of Blacks and Whites cer

tified as eligible for promotion and some Blacks significant

ly outperformed others. Moreover, there were relatively

few positions to be filled. Therefore, the district court cor

rectly determined that since a significant number of Black

candidates completed the entire process and qualified for

these promotions, no adverse impact was shown against

Black candidates.

12

ARGUMENT

THE SELECTION PROCESS FOR POLICE

SERGEANT HAD NO DISPARATE IMPACT ON

BLACK CANDIDATES

A. Standard o f Review and Proceedings Under Review

In the court below, the parties stipulated that the only

issue on the merits for the court to resolve was the issue

of whether the examination process under challenge had

an adverse impact on Black candidates (J.A. 81). The

defendants agreed that if the district court found that the

examination had an adverse impact on Blacks, they would

not seek to litigate the validity of the examination. Based

on the undisputed material facts, the parties submitted

cross-motions for summary judgment. We submit that the

district court correctly determined that application of the

governing legal standards to the undisputed facts of this

case leads to but one conclusion — the examination pro

cess had no significant adverse impact on Black candidates.

Thus, under the established standards for the grant of sum

mary judgment, the district court properly entered judg

ment in favor of the defendants. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett,

477 U.S. 317, 325 (1986). Since this Court is now called

upon to review an alleged misapplication (Br. at 13) of

the governing legal standards to the undisputed facts in

this case, the applicable standard of review is de novo.

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 289 n.19 (1982).

Plaintiffs contend that “at stake in the instant appeal

are both retrospective relief for blacks denied promotions

as a result of the 1987 Eligibility List, and prospective relief

regarding the continued use of a selection process similar

to that utilized in preparing the 1987 List” (Br. at 10, em

phasis supplied). While the meaning of this statement is

less than clear, it is plain that there is only one selection

13

process at issue in this appeal. As the district court stated,

“[t]he underlying claim concerns the legality, under Title

VII, of a promotional examination given in 1986-1987, the

results of which were to be used to make all promotions

to the position of Sergeant for a three-year period from

1987 through 1990” (J.A. 189-190). Thus, as plaintiffs have

otherwise acknowledged, the only examination process

which formed the basis of their underlying claim (Amend.

Complaint - J.A. 7, 8, 16, 21), and on which the district

court was asked to rule, was the process which resulted

in an eligibility list that expired in March of 1990. Although

a new examination was subsequently administered and has

resulted in a new eligibility list, the validity of that ex

amination was not challenged in the proceeding below.

In fact, plaintiffs, who have informed this Court that ad

ministrative proceedings are pending before the EEOC on

claims concerning that separate examination, did not, in

the court below, attempt to amend their complaint to raise

allegations arising out of that exam (J.A. 207). In short,

the only issue presented for review in this case is the district

court’s rejection of plaintiffs’ claim that the examination

process and resulting eligibility list, which expired on

March 30, 1990, had a disparate impact on Black

candidates.

B. A pplicable L egal Standards

The Supreme Court has now clarified the standards

which apply to cases such as the one at bar which rely on

the disparate impact theory to prove discrimination. That

theory presumes that “some employment practices,

adopted without a deliberately discriminatory motive, may

in operation be functionally equivalent to intentional

discrimination.” Watson v. Fort W orth Bank and Trust,

487 U.S. 977 (1988). See also, Wards Cove Packing C o.,

Inc. v. Frank Antonio, 109 S.Ct. 2115 (1989). In disparate

impact cases, “facially neutral employment practices that

14

have significant adverse effects on protected groups have

been held to violate the Act without proof that the

employer adopted those practices with a discriminatory

intent.” Watson v. Fort W orth Bank and Trust, 487 U.S.

at 977 (emphasis in original).7

The law in this Circuit has long established that in the

appropriate case, a showing of disparate impact may be

based on “ ‘statistical evidence showing that an employment

practice has the effect of denying the members of one race

equal access to employment opportunities.” ’ Bushey v. New

York State Civil Service C om m ’n, 733 F.2d 220, 225 (2d

Cir. 1984) (collecting cases), quoting New York City Transit

Authority v. Beazer, 440 U.S. 568 (1979). The Supreme

Court in Watson v. Fort W orth Bank and Trust provided

generalized guidelines concerning the kind and quantity of

statistical evidence that is sufficient to raise an inference

of discriminatory impact. Eschewing “any rigid

mathematical formula”, the Court explained that “statistical

disparities must be sufficiently substantial [in order to] raise

such an inference.” Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust,

487 U.S. at 995 (emphasis supplied). The Court emphasized

that no consensus has developed around any one

mathematical standard for demonstrating disparities in

selection rates and “courts appear generally to have judged

the ‘significance’ or ‘substantiality’ of numerical disparities

on a case-by-case basis.” 487 U.S. at 995 n.3.

While no consensus has developed around any one

theory, two approaches to the issue of whether a disparity

7 Once a prima facie case of discrimination based on a showing of

disparate impact is established, then and only then will an employer

carry the burden of producing evidence of a business justification for

its employment practice. The courts have made clear, however, that

while the employer may have the burden of producing evidence of

business justification, the burden of persuasion always rests with the

plaintiff. Wards Cove Packing Co., supra.

15

in selection rates is “sufficiently substantial”, both men

tioned in Watson as providing a point of reference for the

courts, have emerged. After outlining these approaches,

we will show that the district court correctly determined

that their application to the relevant aspects of the selec

tion process in this case reveals either no disparity between

the Black and White selection rates at all or, if a slight

disparity does exist, that the disparity is not statistically

and/or practically significant, and, therefore, is not “suf

ficiently substantial.”

The Supreme Court (Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S.

482, 496 n .17 (1977); H azelw ood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977)), as well as this Court,8 have

referred to the standard deviation analysis as a unit of

measurement to assess whether differences in selection rates

8 In Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Comrn ’n, 630 F.2d 79, 86-87 n,4

(2d Cir. 1980), this Court defined the concept of standard deviation

as follows:

“The standard deviation for a particular set of data pro

vides a measure of how much the particular results of that

data differ from the expected results. In essence, the stan

dard deviation is a measure of the average variance of the

sample, that is, the amount by which each item differs from

the mean. The number of standard deviations by which

the actual results differ from the expected results can be

compared to the normal distribution curve, yielding the

likelihood that this difference would have been the result

of chance. The likelihood that the actual results will fall

more than one standard deviation beyond the expected

results is about 32% . For more than two standard devia

tions, it is about 4.6% and for more than three standard

deviations, it is about .03% . On this basis, the Supreme

Court concluded in Castaneda that when actual results fell

more than three standard deviations from the expected

result (that is, a race-neutral selection), the deviation could

be regarded as caused by some factor other than chance.”

16

are statistically significant. “The greater the number of

standard deviations, the less likely it is that chance is the

cause of any difference between the expected and observed

results” (Ottaviani v State Univ. o f New York at New Paltz,

875 F.2d 365, 372 (2d Cir. 1989) (citation omitted)),9 or,

in other words, the more likely the difference is statistically

significant. However, in Watson, the Supreme Court made

clear that it had “not suggested that any particular number

of ‘standard deviations’ can determine whether a plaintiff

has made out a prima facie case in the complex area of

employment discrimination.” 487 U.S. at 995 n.3 (cita

tion omitted). This Court, following “recent Supreme

Court pronouncements”, has soundly rejected the efficacy

of a “minimum threshold level of statistical significance”

for determining whether the plaintiff has established a

prim a fa c ie case of discrimination.10 Ottaviani, 875 F .2d

9 That portion of Justice O’Connor’s decision in Watson v. Fort Worth

Bank and Trust, 487 U.S. at 993, dealing with causation requirements

in disparate impact cases (IID ), commanded a plurality of the Court.

However, in Wards Cove Packing Co., Inc. v. Frank Antonio, 109

S.Ct. at 2124, a majority of the Court indicated that the law with

respect to causation in disparate impact cases was “correctly stated”

by Justice O’Connor in her opinion in Watson. Moreover, even prior

to Wards Cove, this Court in Ottaviani essentially embraced the Wat

son plurality’s analysis when, citing Watson, the Court noted that,

“recent Supreme Court pronouncements instruct that there simply is

no minimum threshold level of statistical significance which mandates

a finding that Title VII plaintiffs have made out a prima facie case.”

875 F.2d at 373.

10 While Ottaviani dealt with discriminatory treatment and not

discriminatory impact, statistical analysis is used in a similar fashion

in both theories. “[Pjlaintiffs in a disparate treatment case frequently

rely on statistical evidence to establish that there is a disparity between

the predicted and actual treatment of employees who are members

of a disadvantaged group. . . .” Ottaviani, 875 F.2d at 370-371. In

deed, after Watson, the distinction between the two theories is blurred

by the fact that the Court has held that subjective employment prac

tices may be judged under the disparate impact model.

17

at 372. In rejecting plaintiffs’ “argument that a finding of

two standard deviations should be equated with a prima

facie case of discrimination under Title V II . . . ”, this

Court explained:

“It is certainly true that a finding of two to three

standard deviations can be highly probative of

discriminatory treatment. * * * As tempting as

it might be to announce a black letter rule of law,

however, recent Supreme Court pronouncements

instruct that there simply is no minimum

threshold level of statistical significance which

mandates a finding that Title VII plaintiffs have

made out a prima facie case. See, e .g ., Watson

v. Fort W orth Bank b Trust, * * * * .”

Ottaviani, 875 F.2d at 372-73.

Standard deviation analysis, however, is not the only

approach the courts have endorsed. Indeed, as will be ex

plained in detail, a test for statistical significance measured

by the standard deviation for a particular set of data may

simply be insufficient, standing alone, to measure the legal

significance or practical impact of any disparities in the

selection process in this case.

In fact, as the district court recognized, it is obvious that

“[w]hen a case of disparate impact rises or falls on a com

parison of the numbers selected, the point at which there

is a disparity in selection rates between the races must grow

so large that it may be said that the numbers alone establish

a ‘sufficiently substantial’ difference in selection rates to

warrant an inference of discriminatory impact” (J.A. 196).

“[Statistical significance is not the same as practical

significance because in isolation it tells nothing about the

importance or magnitude of the differences.” Bilingual

Bicultural Coalition o f Mass M edia, Inc. v. FCC, 595 F.2d

18

621, 641 n. 57 (D.C. Cir. 1978), quotingH. Blalock, Social

Statistics at 163 (2d ed. 1972). In other words, in order

to determine whether a disparity in selection rates is, as

required by the Supreme Court, “sufficiently substantial”,

or stated differently, in order to determine the importance

or magnitude of the differences, courts must determine not

only the bare statistical significance but also the

significance of those differences in practical terms.

As the court below correctly held, to aid in making the

determination of practical significance, guidelines are

already in place. The Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission has adopted guidelines on employee selection

procedures. While the courts are not bound by the

guidelines, and while the Supreme Court has stated that

the “four-fifths rule” set forth in those guidelines provides

no more than a “rule of thumb for the court” (W atson,

487 U.S. at 995 n.3), this Court has repeatedly recognized

that the guidelines are useful in determining the substan

tiality of disparities in selection rates, and has, therefore,

accorded the guidelines “great deference”. Teal v. Con

necticut, 645 F.2d 133, 137 n.6 (2d Cir. 1981), q f f ’d, 457

U.S. 440 (1982); Bushey v. New York State Civil Service

C om m ’n, 733 F.2d 220, 225 (2d Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

469 U.S. 1117 (1985); Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service

C om m ’n, 630 F.2d 79, 88 (2d Cir. 1980).

As is particularly pertinent here, the guidelines, in

cluding the “four-fifths rule” contained in the guidelines,

assess the difference in proportions of selection from a

statistical and practical standpoint. The “four-fifths rule”

or “80% rule” provides in pertinent part:

“D. Adverse im pact and the four-fifths rule.

A selection rate for any race, sex, or ethnic group

which is less than four-fifths (4/5) (or eighty

19

percent) of the rate for the group with the highest

rate will generally be regarded by the Federal en

forcement agencies as evidence of adverse impact,

while a greater than four-fifths rate will generally

not be regarded by Federal enforcement agen

cies as evidence of adverse impact. Smaller dif

ferences in selection rate may nevertheless con

stitute adverse impact, where they are significant

in both statistical and practical terms or where

a user’s actions have discouraged applicants

disproportionately on grounds of race, sex, or

ethnic group. Greater differences in selection rate

may not constitute adverse impact where the dif

ferences are based on small numbers and are not

statistically significant, or where special recruit

ing or other programs cause the pool of minority

or female candidates to be atypical of the normal

pool of applicants from that group. 29 C .F.R .

1607.4D (Exh. A to Plaintiffs’ Brief at iii).”

It should be noted that this Court has used both stan

dard deviation analysis and the four-fifths rule to deter

mine the impact of a selection process which is alleged to

have a discriminatory effect. See, e.g., Guardians Assn

v. Civil Service C om m ’n, 630 F.2d at 88. Further, courts

have recognized that, although the difference in selection

rates between two groups may be statistically significant,

because of the numbers involved, the magnitude of the dif

ference between the groups may be so small that it is ap

propriate to conclude that the difference is not practical

ly significant, or, in other words, is, in real terms, simply

an insignificant basis on which to find discriminatory

impact.

As we will show in the following section, when the ex

amination process under challenge here is scrutinized with

an eye toward statistical, as well as practical, significance,

20

there are no disparities between the Black and White selec

tion rates which warrant a finding of discriminatory

impact.

C . The M ulti-Component Examination Process H ad No

D isparate Im pact on B lack Candidates

1. The W ritten Exam ination

To assess whether the selection process had an adverse

impact on Black candidates, it is necessary to first conduct

an analysis of the pass rates of Blacks and Whites on the

written component of the examination. As the Port

Authority’s expert, Dr. Abrams, explained in her affidavit,

“in analyzing adverse impact of multi component selec

tion procedures, it is important to analyze any separate

components in the process which serve to exclude par

ticipants from subsequent components of the selection pro

cess” (J.A. 37) (emphasis supplied). This is the case because

the Supreme Court has determined, in affirming a deci

sion of this court, that a protected employee who

demonstrates that a “pass/fail barrier” in a multi-

component selection process had a discriminatory impact

on his class makes out a prim a fa c ie case of discrimina

tion under Title VII despite the fact that the “bottom-line”

of the selection process had no adverse impact against the

class as a whole. Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982).

The plaintiffs in Teal had all failed the first step in a selec

tion process for permanent supervisory promotions — a

written examination. Plaintiffs, who were able to show

that Blacks passed the written test at a rate less than 80 %

of the White rate, were determined to have a cause of ac

tion under Title VII even though the overall promotion

rate for Blacks was higher than for Whites.

In the instant case, the written component of the ex

amination was taken by 508 Whites and 64 Blacks. Of

21

those, 455 Whites and 50 Blacks passed the written ex

amination (J.A. 86, 188). Significantly, the percentage of

Whites passing was 89.57 % and the percentage of Blacks

passing was 78.13% (J.A. 86). As the district court

recognized, the passing rate for Blacks is 87.2%

(78.13/89.57 = .872) of the passing rate for Whites, a rate

which plainly is greater than the 80% rule (J.A. 86,

197-98). Thus, the instant case is clearly distinguishable

from Teal where the passing rate for Blacks on the writ

ten exam was less than 80% of the White rate.

Further, to complete the analysis of pass rates, Dr.

Abrams notes that the Uniform Guidelines state that

“ ‘small differences in selection rates may nevertheless con

stitute adverse impact, where they are significant in both

statistical and practical terms. . . (J.A. 38). Here, a

test for the statistical significance between the difference

in pass rates yields 2.68 standard deviations (J.A. 124, 145).

However, as the district court noted, “had two more Black

candidates passed the examination, the difference in pass

rates would no longer be statistically significant” (J.A. 198).

Obviously, therefore, the district court was correct in

holding that “[a] proper analysis of a written examination

with results which are as close as these requires considera

tion of not only bare statistical significance, but also prac

tical significance” (J.A. 198). As we have noted, one must

often look at practical significance because bare statistical

significance “tells nothing about the importance or

magnitude of the differences” (Bilingual Bicultural Coali

tion o f Mass M edia, Inc. v. FC C , 595 F.2d at 642 n.57),

and the Supreme Court has made clear that a disparity

must be “sufficiently substantial” (W atson , supra) to war

rant an inference that the disparity is attributable to race.

Here, since the difference in pass rates on the written

examination meets the four-fifths rule, and no statistical

significance would be shown if only two other Black

22

candidates had passed the examination, the court below

appropriately concluded that the difference in pass rates

is simply not practically significant or “sufficiently

substantial”.11

Instructive in this regard is Jackson v. Nassau County

Civil Service C om m ’n, 424 F.Supp. 1162, 1168 (E.D.N.Y.

1976). In that case, the court, obviously sensitive to prac

tical significance, refused to find disparate impact after

evaluating the results of an examination where a signifi

cant alteration in the passing percentages would occur by

the simple shift of several minority candidates from the

failing to the passing column. In this case also, the failure

of two more Black candidates to pass the written examina

tion simply does not rise to the level of a significant

disproportion that cries out for judicial remedy.

Additionally, it is interesting to compare the instant case

to prior decisions of this Circuit which have found that

the differences in percentages of pass rates on written ex

aminations did have an adverse impact. Significantly, those

cases involved differences in passing rates between Whites

and minority candidates which were markedly greater

than the differences in the case at bar.

Thus, in Bushey v. New York State Civil Service

C om m ’n , 733 F.2d at 225-226 (emphasis supplied), this

11 Plaintiffs would fault the court below for using the four-fifths rule

as a measure of practical significance. They assert that “[fjailure to meet

the Guidelines’ four-fifths threshold is precisely what triggers the

Guidelines’ additional inquiry into statistical and practical significance”

(Br. at 32). Under plaintiffs’ analysis of the EEOC guidelines, however,

the court’s alleged error on this point would be of no consequence on

these facts since it is undisputed that the pass rates on the written com

ponent meet the four-fifths rule and, therefore, there would be no need

to further consider statistical or practical significance.

23

court, using the 80 per cent rule, noted that “the passing

rate of minority candidates [for promotion to Correction

Captain] was approximately fifty percent low er than the

passing rate of the nonminority candidates.” In Kirkland

v. New York State D ept, o f C orrectional Services, 374

F.Supp. 1361 (S.D.N.Y. 1974), a ff ’d, 520 F.2d420 (2d Cir.

1975), cert, denied , 429 U.S. 823 (1976), 30.8% of the

Whites and only 7.7 % of the Blacks passed the exam for

promotion to Correction Sergeant. Further, in Guardians

Assn v. Civil Service C om m ’n, 630 F.2d at 87, 88, on

evidence that the minority pass rate for an exam ad

ministered to determine selection for the position of City

police officer was about two-fifths the passing rate for

Whites (and 89 standard deviations), it was determined

that “[b]y any reasonable measure, including the standard

deviation . . . or the four-fifths rule of the EEOC

Guidelines”, the exam had a disparate impact on Blacks.

And finally, in Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. M em bers o f

Bridgeport Civil Serv. C om m ’n, 482 F.2d 1333, 1335 (2d

Cir. 1973), the passing rate for White candidates for the

position of police officer was three and one-half times the

passing rate for minorities.

Aware that the actual pass rate for Blacks compared to

the pass rate for Whites on the written component survives

the four-fifths rule, plaintiffs argue instead that the Court

should consider the fact that since the Port Authority

reached only rank number 85 on the list, a higher score on

the written test than the actual passing score was needed

to reach a rank on the Eligible List that would qualify a

candidate for promotion (Br. at 26-29). Plaintiffs argue that

“[f]rom a purely mathematical perspective, a score of at

least 76 was needed for an applicant to be eligible for pro

motion” (Br. at 27). They assert that the difference in pro

portion of Blacks scoring 76 or higher demonstrates adverse

impact under the four-fifths rule and that the statistical

significance for such proportional difference yields a result

24

of 2.68 standard deviations — also showing adverse im

pact (Br. at 29). Plaintiffs attempt to support this argu

ment for the significance of a higher passing score from

a reading of the Supreme Court’s decision in Connecticut

v. Teal, which they argue stands for the proposition that

the test for adverse impact is whether one component of

an exam process denied minorities to a disproportionate

degree the opportunity to be promoted (Br. at 26). There

are, however, several fallacies in plaintiffs’ reasoning, and,

despite plaintiffs’ attempt to squeeze the very different facts

of this case into the principle announced in Teal, that case

is readily distinguishable.

Significantly, in Teal, all plaintiffs fa iled the written ex

amination component and were thus barred from proceed

ing to the next step in the examination process. Here, in

sharp contrast to that situation, when a separate analysis

of the pass/fail rates on the written exam is undertaken,

no disparate impact on Black candidates is shown. Once

this pass/fail analysis is performed, Teal does not require,

and it is not necessary for, the Court to separately analyze

any disparity7 in the subscores or in the performance on sub

tests of the examination because the actual selection of those

to be promoted was based on the overall ranking on the

list which, in turn, was based on a combination of scores

on all components (J.A. 84, 199). Indeed, for this reason,

as this Court has noted, “[wjhere all of the candidates par

ticipate in the entire selection process, and the overall results

reveal no significant disparity of impact, scrutinizing in

dividual questions or individual sub-tests would, indeed,

‘conflict with the dictates of common sense.’ ” Teal, 645

F.2d at 138, quoting Kirkland v. New York State Dept,

o f Correctional Services, 374 F.Supp. 1361, 1370 (S.D.N.Y.

1974), a f f ’d, 520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975).

At bottom, plaintiffs would apparently translate the

language in Teal, which speaks of equality of opportunities

25

for individuals, into a requirement that a multi-component

exam be constituted so that individuals from protected and

unprotected groups score as well on each component of the

examination, even though it is a composite score from all

components which results in the final ranking and ultimate

selection of candidates. But plaintiffs misconstrue Teal.

Contrary to plaintiffs’ analysis, Teal does not dictate an

inquiry into individual performance on subtests or, follow

ing plaintiffs’ logic, individual performance on questions

in a subtest. See, Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 464

n.8 (Powell, J . , dissenting) (“Another possibility [flowing

from the majority decision] is that employers may integrate

consideration of test results into one overall hiring deci

sion based on that ‘factor’ and additional factors. Such a

process would not, even under the Court’s reasoning, result

in a finding of discrimination on the basis of disparate im

pact unless the actual hiring decisions had a disparate im

pact on the minority group.” (emphasis in original).

In fact, “common sense” dictates that since there is a

multi-component exam involved, any legally significant

disparity in scores achieved by a protected class on one

component of the examination will be reflected in the ag

gregate results for that class and, thus, in the overall pro

motion rates. Here, while a comparison of pass/fail rates

for Blacks and Whites on the written exam satisfies the 80

percent rule, it is undisputed that Whites did score better

than Blacks on this exam component. However, it is also

undisputed that Blacks outperformed Whites both in pass

rates and scores on the oral examination component, and

that the scores from all components were aggregated before

candidates were placed on the eligibility list.

Most importantly, as the court below recognized, an

analysis of the overall results of the process — the actual

promotion rates — reveals no statistical disparity between

the numbers of Blacks and the numbers of Whites

26

promoted (J.A. 200). Further, the facts reveal that the dif

ference in overall average scores achieved by Blacks and

Whites on the total test process is so slight that, even if

those scores were determinative of adverse impact, the dif

ference amounts to only 2.2 written exam questions (J.A.

150).

Arguing further, plaintiffs state that a comparison of

performance at the established pass rate for the written

component (66% and above) “does not meet the initial

four-fifths threshold” of the guidelines (Br. at 30). Actually,

since the pass rate for Blacks was 87.2% of the pass rate

for Whites, the rate is greater than 80 % and, therefore,

the court below correctly determined that a comparison

of pass rates does not violate the four-fifths or 80 % rule

(J.A. 197-98). Plaintiffs, however, apparently fault the

district court for failing to find, as legally determinative

of adverse impact, the fact that this difference in pass rates

was, nonetheless, statistically significant at 2.68 standard

deviations (J.A. 88) (Br. at 32). Actually, the EEOC

guidelines do not, by their terms (supra, at 18, 19), man

date an inquiry into statistical significance if, as here, the

four-fifths rule of thumb is not violated. Further, “there

simply is no minimum threshold level of statistical

significance which mandates a finding that Title VII plain

tiffs have made out a prima facie case” (Ottaviani, 875

F.2d at 372-73). Also, while the guidelines indicate that

small differences in selection rates (rates that exceed 80 %)

may constitute adverse impact if they are statistically and

practically significant, as we have noted, the statistical dif

ferences present here would disappear if only two addi

tional Blacks had passed the examination.

Plaintiffs note that an additional two blacks scoring

higher than the established pass rate of 66 % would not

equalize the pass rates between Blacks and Whites (Br. at

34). However, as we have noted, those pass rates already

27

meet the four-fifths rule and such a hypothetical change

would bring the pass rates even closer together (81.25%

Black pass rate divided by 89.57 % White pass rate equals

90.71% ). Thus, under this hypothetical, while absolute

equality would not be achieved, the point for practical

significance is that a small shift in the pass rates would

bring those rates much closer together. Therefore, under

the present state of the law, and on these facts, it may not

be maintained that the district court committed legal er

ror in failing to find adverse impact from the differences

in pass rates on the written component.12

2. The Oral Exam ination and the Perform ance

Appraisal

Three of the seven named plaintiffs based their allega

tions of discrimination on the alleged discriminatory im

pact of the oral examinations (J.A. 95). However, by any

measure and plaintiffs do not argue otherwise, the oral ex

amination as well as the performance appraisal component

did not have a disparate impact on Black police officers.

In fact, on the oral, the pass rate for Blacks at 67.35 % was

greater than the 57.58 % pass rate for Whites (J.A. 90). Fur

ther, the average oral examination score of 73.46 for Blacks

was higher than the mean score of 70.86 for Whites (J.A.

90). Indeed, a test for statistical significance between White

and Black mean scores on the oral examination yields a

negative difference of 1.49 standard deviations.

12 Plaintiffs cite as error the district court’s analysis of practical

significance of the pass rates arguing that statistical significance, if

it exists, may not be nullified by a shift in pass rates (Br. at 34). While

statistical significance may not be nullified in such a manner, in the

wake of the Supreme Court’s determination that differences in selec

tion rates must be “sufficiently substantial” in order to be legally signifi

cant, it is entirely appropriate for a court to look at the “magnitude”

of such differences in terms of actual numbers of individuals impacted

by the process.

28

Also, on the performance appraisal, while there was no

minimum score needed in order to be placed on the

eligibility list, the mean score for Whites was 94.37 and

for Blacks the mean score was 94.17 (J.A. 91). A difference

of only . 16 standard deviations results from a comparison

of mean Black and White scores on this component.

Therefore, since Blacks outperformed Whites both in

pass rates and scores on the oral examination component

and scored almost equally as well as Whites on the per

formance appraisal component of the examination process,

there was no adverse impact posed by those components

of the process.

3. The Eligibility List

The multi-component examination process resulted in

the ranking of the 310 successful candidates on the ver

tical promotion list (J.A. 97). As of March 30, 1990, the

date the eligibility list expired, 79 officers had been pro

moted and the 85th name had been reached on the eligibili

ty list (J.A. 91-92). As of that date, the promotion rate for

Blacks was 7.9 % (5 divided by 63) and the promotion rate

for Whites was 14.0% (70 divided by 499) (J.A. 124, 148).13

The promotion rate for Blacks is thus 57 % of the promotion

13 In computing the promotion rates for the two groups, the plaintiffs

would have included the six grandfathered individuals as well as the

two individuals who retired before being offered promotion. The Port

Authority defendants took the position that the grandfathered in

dividuals should be excluded since they did not participate in the ex

amination process, and the retirees should be excluded because they

removed themselves from the selection process before being offered

promotion (J.A. 124, 125, 147-148). However, in the court below, and

in this Court as well (Br. at 4 ,9), plaintiffs agree with defendants’

assessment that, whatever methodology one selects for this computa

tion, such selection will not materially affect the resolution of this issue

(J.A. 94, 123).

29

rate for Whites. However, because of the small numbers

(only 5 Blacks and 70 Whites selected) on which this

analysis is based, the district court correctly determined

that it would be appropriate to look at the statistical im

pact of these differences.

Once more, the Uniform Guidelines have anticipated

a result such as this and provide ample support for the

court’s analysis. As the Port Authority’s expert, Dr.

Abrams, noted in her affidavit, the Guidelines state that

“ ‘[gjreater differences in selection rate may not constitute

adverse impact where the differences are based on small

numbers and are not statistically significant . . . .’ ” (J.A.

41); 29 C .F .R . §1607.4D. Therefore, in analyzing the ac

tual promotion rates, comparisons which involve small

numbers, the district court correctly held that the proper

approach is to perform a statistical analysis of the dispari

ty in selection rates (J.A. 200). Performing standard devia

tion analysis to measure the impact of the difference in

promotion rates, that difference is 1.34 standard devia

tions (J.A. 125, 148). As the court below held, “[tjhis is

well below the level of 2 or 3 standard deviations” cited

as significant by the courts (J.A. 200).

Indeed, a similar analysis of current promotions was

sanctioned by this Court in K irkland v. New York State

Dept, o f Correctional Services, 711 F.2d 1117, 1131 (2d

Cir. 1983) (Correction Lieutenants). That case dealt with

a claim that the rank ordering on a vertical list used for

promotion to Correction Lieutenant had an adverse im

pact on Blacks (id., at n.5). This court sustained the district

court’s approval of a voluntary settlement of the case, af

firming the district court’s finding that there existed a

prim a fa c ie case of discrimination on the basis of adverse

impact. This Court summarized the district court’s analysis

as follows:

30

“[The district court judge] determined that a

prim a fa c ie case of employment discrimination

had been established after reviewing the statistics

relevant to Exam 36-808 and its eligibility list.

552 F.Supp. at 670. Finding that the d ifferen ce

betw een the percentage o f minorities actually ap

pointed as o f July 28, 1982 (9.0% ) and the

percentage w hich w ould b e expected to b e ap

pointed from a random selection am ounted to the

level o f 5.86 standard deviations, [the judge]

ruled that the statistics made out a prim a fa c ie

case of Title VII discrimination under Castaneda

v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 97 S.Ct. 1272, 51

L.Ed.2d 498 (1977). Castaneda stated that, in

cases involving significant statistical samples, ‘if

the difference between the expected value [from

a random selection] and the observed number is

greater than two or three standard deviations,’

a prim a fa c ie case is established since the devia

tion then could only be regarded as caused by

some factor other than chance.” 711 F.2d at 1131

(emphasis supplied, footnote omitted).

Therefore, the difference of 1.34 standard deviations for

current promotions falls well below the 2 or 3 standard

deviations cited by this Court in Kirkland. Moreover, it

should be emphasized that, as we explained, this Court,

following “recent Supreme Court pronouncements”, has

noted that even a difference in selection rates of 2 or 3 stan

dard deviations will not automatically be translated into

a finding that plaintiffs have established a prim a fa c ie case

of discrimination. Ottaviani, 875 F.2d at 372-73.

Plaintiffs contend, however, that they are entitled, as

a matter of law, to an inference of discrimination because

the actual selection rates exceed the four-fifths rule (Br.

31

at 15). They fault the district court for looking further at

the statistical significance of those rates. Once more, plain

tiffs misinterpret the EEO C guidelines.

Those guidelines contemplate that differences in selection

rates which do not satisfy the 80 % rule may, nonetheless,

not amount to adverse impact where the differences are

based on small numbers and are not statistically significant.

29 C.F.R. §1607.4D. Here, as we have noted, faithful to these

guidelines, the court below correctly determined that since

the differences in question were based on small numbers,

it would be appropriate to look at the statistical significance

of the difference in the selection rates (J.A. 200).

Plaintiffs, however, argue that the numbers involved here

are not as small as the numbers used in the example sup

plied in the EEOC guidelines which are based on an ap

plicant pool of 20 males and 10 females (Br. at 17).

However, plaintiffs overlook the fact that the example given

in the guidelines is just that, an “example”, and is not

presented as determinative of the issue of what constitutes

a small sample size. Plaintiffs would also seek to distinguish

this case from the example in the guidelines (in the form

of a question and answer), demonstrating that in a case

of small numbers, a small shift in selection rates may result

in a selection rate for minorities which is higher than that

for majorities (Br. at 17). They note that, unlike that ex

ample, “[i]n the present case, assuming that one or two of

the promotees were black rather than white, the white pro

motion rate would remain higher than the black promo

tion rate” (Br. at 17-18). We would add that, if two of the

promotees were Black instead of White, a comparison of

promotion rates would bring the Black promotion rate

within 80% of the White promotion rate.14 Thus, we

14 Thus, 7 Blacks divided by 64 equals a selection rate of 10.9 %. When

that rate is compared to 68 Whites divided by 499 or a 13.6% promotion

rate, the Black promotion rate is 80.14 % of the White promotion rate.

32

submit that plaintiffs’ hypothetical supports the decision

of the court below to carefully scrutinize the magnitude

of the differences at issue here and its determination that

such differences are not sufficiently substantial.

Plaintiffs also argue that the district court committed

error in failing to consider “additional” evidence of adverse

impact other than the actual selection rates (Br. at 18).

Plaintiffs would have a court look at the overall distribu

tion of Black candidates on the eligibility list and assert

that, in this case, that factor is determinative because

Blacks were ranked in greater numbers at the bottom of

the list. Once more, plaintiffs’ analysis misses the mark.

First, the overall ranks are obviously reflective of overall

scores achieved on all components of the examination.

Here, a test for statistical significance in the overall scores

achieved on all components of the examination yields 2.43

standard deviations. However, as the undisputed facts

establish, an analysis of this difference in practical terms

reveals that the results are in actuality much closer than

this number might suggest, and amount to no more than

2.43% or what amounts to 2.2 written examination

questions15 (J.A. 150). Since the Supreme Court has made

clear that a disparity must be “sufficiently substantial”,

the closeness of these scores in practical terms means that

the difference in performance of Blacks and Whites on the

overall examination is simply too close to warrant an in

ference of discriminatory impact against Blacks.

Indeed, district courts in this circuit, in an effort to assess

the magnitude of similar differences, have not ignored the

15 The overall mean score for Whites on the written and oral examina

tion process and the performance evaluation process (mean final rank

ing score) was 83.023% and for Blacks that score was 80.597 % . The

difference between those scores amounts to 2.43% (J.A. 92, 156).

33

importance of practical significance. Thus, in Jackson v.

Nassau County Civil Serv. C om m ’n, supra , at 1162, the

district court, although not using that terminology, analyzed

the “practical significance” of a difference in Black and

White scores which resulted in placement on an eligibili

ty list for Community Service Assistant. In that case, the

plaintiffs, as do the plaintiffs in this case, emphasized the

fact that fewer Black candidates “achieved a score suffi

cient to place him or her high enough on the eligibility

list to be offered an appointment.” 424 F.Supp. at 1168. The

Court rejected plaintiffs’ analysis since the claimed dispari

ty in placement would have disappeared if two Black can

didates had each answered one additional question cor

rectly. See also, W ade v. New York Tel. Co., 500 F.Supp.

1170, 1180 (S.D.N.Y. 1980) (failing to find an inference of

racial discrimination due to the discharge of one or two

extra minority employees when the total number of

discharges is so small).

Second, plaintiffs’ reliance on comparative ranks is flawed

because it does not fully take into account the fact that while

310 individuals were placed on the eligibility list, in fact,

only 79 positions became open for promotion. Indeed, an

emphasis on average ranks or even average overall scores

ignores the critical fact that, ultimately, Title VII neither

requires that employers equalize scores or even equalize

probabilities that all individuals from protected groups will

ultimately be promoted, nor that employers keep promoting

until selection rates for all racial groups are on complete

parity. Bather, it requires that members of protected groups

enjoy relatively equal opportunities for promotion to those

positions that become available. Here, due to the Port

Authority’s manpower needs, there were only 79 “Sergeant”

positions which needed to be filled. Ultimately, what is most

important is the fact that a significant number of Blacks

performed well enough on the examination process to

qualify themselves for promotion to these 79 spots.

34

Further, the cases cited by plaintiffs in support of their

theory that comparative ranks present evidence of adverse

impact are readily distinguishable. Plaintiffs claim that in

Kirkland v. New York State Dept, o f Correctional Services,

711 F.2d at 1122, this Court based its inquiry into disparate

impact on the fact that “minority representation within

the eligibility list’s rank-ordering system was dispropor

tionately low at the list’s top and high at the list’s bottom”

(Br. at 19). However, as we have noted, in ruling on the

issue of adverse impact, Kirkland affirmed the lower court’s

finding which was based on the facts showing that the dif

ference between the number of minorities appointed and

the expected number was 5.86 standard deviations. In

sharp contrast, in the instant case, the difference is 1.34

standard deviations (J.A. 200).

G ilbert v. City o f L ittle R ock, A rk., 722 F.2d 1390 (8th

Cir. 1983) (cited in Br. at 19-20, 23), is also an entirely dif

ferent case on its facts from the one at bar. In Gilbert, the

court of appeals remanded, for further proceedings, allega

tions that a process for promotion of police officers to the

ranks of Sergeant and Lieutenant had a discriminatory im

pact on Black candidates. The plaintiffs argue that Gilbert,

in which virtually all Black candidates were ranked too

low on the eligibility list to attain the few promotions made

from the lists certified each year, demonstrates the danger

present in this case that “employers could easily use selec

tion practices that cause discrimination and still evade en

forcement of Title V II.” They assert that “[s]o long as an

employer used a test to make only a modest number of pro

motions, a paucity of minority promotions could not by

itself be statistically significant” (Br. at 22).

First, plaintiffs’ argument in this regard (See also, Br.

at 21) is confusing because it has never been contended

that the numbers selected in this case, while small, are too

small to be the subject of a reliable statistical analysis and

35

plaintiffs have stipulated to the accuracy of these underly

ing statistics (J.A. 80-81). Second, in G ilbert, the court de

termined that because of the serious allegations of pervasive

racial harassment in the police force, on remand, “it is in

cumbent upon the district court to consider the statistical

evidence against the background of racial harassment at the

Little Rock Police Department.” 722 F .2d at 1398. Signi

ficantly, there are no similar allegations in this case, nor

is there evidence that the Port Authority, as was the case

in G ilbert, used the selection process at issue here, which

has now expired, to avoid minority appointments. 722 F.2d

at 1397. Indeed, in the court below, plaintiffs specifically

withdrew their allegations of intentional discrimination.

Also, in stark contrast to the situation in G ilbert (722 F.2d

at 1397 n.8) in which the district court was faulted for not

looking at the overall results including the ranking aspect

of the promotion system, a significant number of Blacks

were in fact ranked high enough to be promoted to

Sergeant in the selection process under challenge.16

The plaintiffs noted in their Statement of Material Facts

that “[i]f the Port Authority had actually made 145 pro

motions, the calculated statistical significance of the dif

ference in black and white promotion rates would have

been greater than 2.0” (J.A. 94). This statement graphically

demonstrates the fallacy in plaintiffs’ reliance on a com

parison of average ranks. In fact, since 258 Whites and

33 Blacks completed the entire examination process and

were placed on the eligibility list, if the Port Authority had

16 Plaintiffs also attempt to glean support for their argument on the

validity of a comparison of overall ranks from Underwood v . State of