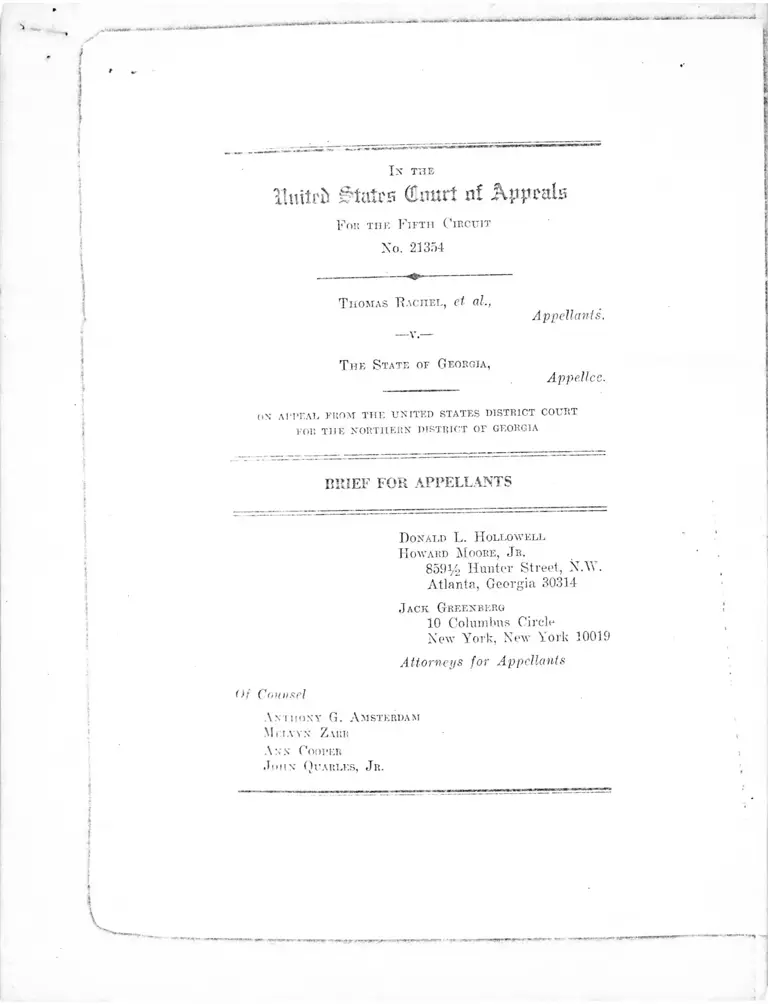

Rachel v. Georgia Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rachel v. Georgia Brief for Appellants, 1964. d2fce2bd-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cc852238-ff0a-4069-b8ef-b8bf2e9195e7/rachel-v-georgia-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

Ix THE

HiutrEs S t a t e s C im r t n ! A p p e a l s

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 21354

T homas 'Raciiel, et al.,

-v.-

T he S tate of Georgia,

Appellant i

Appellee

OX A1’PEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

D onald L. H ollowell

H oward M oore, Jr.

859% Hunter Street, N.Y\.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

Of Counsel

A nthony G. A msterdam

Mi.i.YYN Z aur

A x x Cooper

John Q uarles, J r.

\

^ .**>.■** aii

I n the

'i lu i t i i i f^ ta trn (d m ir t n f A p o n t h i

P’ok the F ifth Circuit

No. 21354

T homas R achel, et al.,

Appellants,

T he S tate of Georgia,

Appellee.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of ilie Case

Appellants are twenty Negro and white persons charged

by special presentment of the July-August, 1963 Term of

the Grand Jury of Fulton County, Georgia with violating

Title 26, Georgia Code Annotated, Section 3005, refusing

and failing to leave the premises of another when requested

to do so, a misdemeanor (R. 2-3).

On February 17, 1964, prior to their cases being reached

for trial before the Honorable Durwood T. Pye, Judge,

Fulton Superior Court, AJdantic^Jiidicial Circuit, appel

lants filed a verified removal petition in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Georgia,

Atlanta Division (R. 2-5, 7). Removal was sought pur

suant to Title 28, U. S. C. A., 1443(1) and (2) (R. 6).

In their verified removal petition, appellants alleged that

their arrests by members of the Atlanta Police Depart

ment at various hotels, cafeterias, and restaurants within

the City of Atlanta in the spring and early summer of

1963 had been “ effected for the sole purpose of aiding,

abetting, and perpetuating customs, and usages which have

deep historical and psychological roots in the mores and

attitudes which exist within the City of Atlanta with re

spect to serving and seating members of the Negro race

in . . . places of public accommodation and convenience

upon a racially discriminatory basis and upon terms and

conditions not imposed upon members of the so-called white

or Caucasian race. Members of the white . . . race are

similarly treated and discriminated against when accom

panied by members of the Negro race” (R. 2-5).

Appellants sought removal “ to protect rights guaranteed”

under the due process and equal protection clause of the

Fourteentli Amendment and to protect First Amendment

rights “ of free speech, association, and assembly . . . ”

(R. 6).

Appellants, also, averred that they were “being prose

cuted for acts done under color of authority derived from

the Constitution and laws of the United States and for

refusing to do acts inconsistent with the Constitution and

laws of the United States” (R. 6).

The following day, without hearing or argument, United

States District Judge Boyd Sloan remanded sua spoilte,

and held that “ the petition for removal to this Court does

not allege facts sufficient to justify . . . removal.” Judge

Sloan construed section 1443 to be inapplicable “where a

party is deprived of any civil right by reason of discrimi

nation or illegal acts of individuals or judicial or adminis

trative officers” (R. 14).

On March 5, 1964, appellants filed notice of appeal from

the District Judge’s order (R. 16).

Appellants herein, on March 12, 1964, filed a motion for

stay pending appeal in the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

2

i ■i.Yr i iViunTr̂ ■’■■■*<* ***-■ it.

3

Circuit to which was annexed a copy of the verified re

moval petition and the removal order. The motion recited

tint Judge Pye had ordered defendants m othei ca. .

pnidin- on his calendar involving alleged violations o

Title 26-3005 to show cause why their appearance bonds

should not he increased and why fresh surety si on no.

bo given and that movants (Appellants herein) stood

threatened with the immediate prospect of their bom s

being increased. Judge Pye had already increased the bond

of one accused niisdenH-ari02i££I!Lf22^J°j!L^-ia :- ^ ^ - _

lants’ bonds were increased, many oH lim w o u ia ̂ re

quired to remain in jail because of inability to make the

increased bond. Their motion further recited that the enm

inal prosecutions prevented them from exercising rights

under the federal Constitution and laws, that if the Dis 1

Tmb-e had granted a hearing appellants herein would have

shown facts sustaining federal removal jurisdiction, and

that unless a stay were granted substantial issues raised

by appellants would become moot (App. ©-•-) ------------ '

Also on March 12th, the State of Georgia moved to dis

miss the appeal and to deny the stay, arguing that the

Court of Appeals was without jurisdiction of the case (R.

2(1-30).

The same day, on the authority of Congress of Racial

Equality v. City of Clinton, Louisiana (now pending for

decision on the merits in this Court), the Court of Appeals

ordered the remand order “ stayed pending final disposition

of this appeal on the merits or the earlier order of [the]

Court” (R. 32). District Judge Carswell, sitting by desig

nation, dissented (R. 32).

* Through inadvertence the appellants’ motion for stay pending

appeal was omitted from the printed record and is reproduced as

an appendix to the appellants’ brief in order to expedite the appeal

and to avoid the costs of preparing a supplemental record. The

motion for stay is properly before this Court since it was timelj

designated as a part of the record on appeal (R. 18).

________________„ ___ w . ------ -------- . . — - ̂

4

On April 1, 1961, Judge Pye ordered the Solicitor Gen

eral, Atlanta Judicial Circuit, to apply to the Supreme

Court of the United States for writs of mandamus and

prohibition against this Court directing the Court to vacate

its stay order and to proceed no further with the case. In

a memorandum order, appellee’s application tor leave to

file a petition for extraordinary relief was denied by the

Supreme Court of the United States on June 22, 1964.

State of Georgia, v. Tuttle, et al., 32 U. S. L. Week 3446

(U. S. 6/22/64).*

Statutes and Rules

28 IT. S. C. §1291 (1958):

§1291. Final decisions of district courts.

The courts of appeals shall have jurisdiction of ap

peals from all final decisions of the district courts of

the United States, . . .

28 U. S. C. §1443 (195S):

§1443. Civil rights cases.

Any of the following civil actions' or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a Stale court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot en

force in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the jurisdic

tion thereof;

* On this appeal, appellants substantially repeat their argument

first made in opposition to the motion of the State of Georgia in

the Supreme Court of the United States for extraordinary relief

in State of Georgia v. Tuttle, et al., supra.

0

(2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for refus

ing to do any act on the ground that it would be in

consistent with such law.

28 U. S. C. §1447(d) (1958):

§1447. Procedure after removal generally.

(d) An order remanding a case to the State court

from which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal

or otherwise. . . .

28 U. S. C. §1651 (1958):

§1651. Writs.

(a) The Supreme Court and all courts established

by Act of Congress may issue all writs necessary or

appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and

agreeable to the usages and principles of law.

28 U. S. C. §2241 (1958):

§2241. Power to grant writ.

(a) Writs of habeas corpus may be granted by the

Supreme Court, any justice thereof, the district courts

and any circuit judge within their respective jurisdic

tions. The order of a circuit judge shall be entered in

the records of the district court of the district wherein

the restraint complained of is had.

(b) The Supreme Court, any justice thereof, and any

circuit judge may decline to entertain an application

for a writ of habeas corpus and may transfer the ap

plication for hearing and determination to the district

court having jurisdiction to entertain it.

6

(e) The writ of habeas corpus shall not extend to

a prisoner unless—

(3) He is in custody in violation of the Constitu

tion or laws or treaties of the United States; . . .

28 U. S. C. §2254- (195S):

§2254. State custody; remedies in State Courts.

An application for a writ of habeas corpus in behalf

of a person in custody pursuant to the judgment, of a

State court shall not be granted unless it appears that

the applicant has exhausted the remedies available in

the courts of the State, or that there is either an ab

sence of available State corrective process or the exist

ence of circumstances rendering such process ineffec

tive to protect the rights of the prisoner.

An applicant shall not be deemed to have exhausted

the remedies available in the courts of the State, within

the meaning of this section, if he has the right under

the law of the State to raise, by any available pro

cedure, the question presented.

Fed. Rule Civ. Pro. 81 (b ) :

(b) Scire Facias and Mandamus. The writs of scire

facias and mandamus are abolished. Relief heretofore

available by mandamus or scire facias may be obtained

by appropriate action or by appropriate motion under

the practice prescribed in these rules.

Fed. Rule Grim. Pro. 37:

Rule 37.

(a) Talcing Appeal to a Court of Appeals.

(1) Notice of Appeal. An appeal permitted by law

from a district court to a court of appeals is taken by

7

filing with the clerk of the district court a notice of

appeal in duplicate. . . .

(2) Time for Talcing Appeal. An appeal by a defen

dant may he taken within 10 days after entry of the

.judgment or order appealed from. . . .

Ga. Code Ann. §20-3005 (1963 Supp.):

20-3005. Refusal to leave premises of another when

ordered to do so by owner or person in charge.—It

shall be unlawful for any person, who is on the prem

ises of another, to refuse and fail to leave said prem

ises when requested to do so by the owner or any

person in charge of said premises or the agent or em

ployee of such owner or such person in charge. Any

person violating the provisions of this section shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof

shall he punished as for a misdemeanor. (Acts I960,

p. 142.)

<r Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Slat. 241 (P. L. SS-352):

T itle I X — I ntervention and P rocedure A fter

R emoval in C ivil R ights Cases

S ec. 901. Title 28 of the United States Code, section

1447(d), is amended to read as follows:

An order remanding a case to the State court from

which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal or

othenvise, except that an order remanding a case to

the State court from which it was removed pursuant

to section 1443 of this title shall be reviewable by ap

peal or otherwise.”

. ____ Tiif >■ n _____________ ...

8

Statutory History

Since the inception of the Government, federal removal

jurisdiction has been progressively expanded by Congress’

to protect national interests in cases “ in which the state

tribunals cannot be supposed to be impartial and un

biassed,’' for, as Hamilton wrote in The Federalist, “The

most discerning cannot foresee how far the prevalency of

a local spirit may be found to disqualify the local tribunals

for the jurisdiction of national causes. . . . ” 2 3 In the fed

eral convention Madison pointed out the need for such

protection, just before he successfully moved the Commit

tee of the Whole to authorize the national legislature to

create inferior federal courts :4

“ Mr. [Madison] observed that unless inferior tri

bunals were dispersed throughout the Republic with

final jurisdiction in many cases, appeals would be

multiplied to a most oppressive degree; that besides, an

1 Sec H art & W echsler, T he F ederal Courts and the F ederal

System 1147-1150 (1953). Before 1887, the requisites for removal

jurisdiction were stated independently of those for original fed-

ernh jurisdiction; since 1887,“ the statutory scheme has been jto

authorize removal generally of cases over which the lower federal

courts have original jurisdiction and, additionally, to allow removal

in special classes of eases particularly affecting the national inter

est: suits or prosecutions against federal officers, military per

sonnel, persons unable to enforce their equal civil rights in the

state courts, person acting under color of authority derived from

federal law providing for equal rights or refusing to do an act

inconsistent with such law, the United States (in foreclosure ac

tions), etc. 28 TT. S. C. §§1441-1444 (1958) ; see H art & W echsler,

supra, at 1019-1020.

2 The F ederalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) (Warner, Philadelphia cd.

1818), at 429.

3 Id., No. 81, at 439.

4 1 F ar r axd , R ecords of t h e F eder al C o n v e n t io n 125 (1 9 1 1 ) .

Mr. Wilson and Mr. Madison moved the matter in pursuance of

a suggestion of Mr. Dickinson.

, , , ....._■ . _____- ____ * 4,____

9

appeal would not in many oases be a remedy. What

was to be done after improper Verdicts in State tri

bunals obtained under the biassed directions of a de

pendent Judge, or the local prejudices of an undirected

jury? To remand the cause for a new trial would an

swer no purpose. To order a new trial at the supreme

bar would oblige the parties to bring up their wit

nesses, tlio’ ever so distant from the seat of the Court.

An effective Judiciary establishment commensurate to

the legislative authority, was essential. A Government

without a proper Executive & Judiciary would be the

mere trunk of a body without arms or legs to act or

move.” 5 *

The Judiciary Act of 17S9 allowed removal in specified

classes of cases where it was particularly thought that

local prejudice would impair national concerns," and exten

sions of the removal jurisdiction were employed in 1815

and 1833 to shield federal customs officials, respectively,

against New England’s resistance to the War of 1812 and

South Carolina’s resistance to the tariff.7 The 1815 act al

51 id. 124.

0 The Act of September 24, 1780, eh. 20, §12, 1 Stat. 73, 79-80,

authorized removal in three classes of cases where more than $500

was in dispute: suits by a citizen of the forum state against an out-

stater; suits between citizens of the same state in which the title

to land was disputed and the removing party set up an outstate

land grant against his opponent’s land grant from the forum state;

suits against an alien. The first two classes were specifically de

scribed by Hamilton as situations “ in which the state tribunals

cannot be supposed to be impartial,” T h e F eder alist , No. 80

(Warner, Philadelphia ed. 1818), at 432; and Madison, speaking

of state courts in the Virginia convention, amply covered the

third: “ We well know, sir, that foreigners cannot get justice done

them in these courts. . . . ” I l l E lliot’s D ebates 583 (1836).

7 Act of February 4. 1815, ch. 31, §8, 3 Stat. 195, 198. Concern

ing Northern resistance to the War culminating in the Hartford

10

lowed removal of “ any suit or prosecution” (save prosecu

tions for offenses involving corpora] punishment) com

menced in a state court against federal officers or other

persons acting under color of the act or as customs officers,

3 Stat. 198; the 1833 act allowed removal in any case where

“ suit for prosecution” was commenced in a state court

against any federal officer or other person acting under

color of the revenue laws, or on account of any authority

claimed under the revenue laws, 4 Slat. 633.

Congress was thus acting within a tradition of enforcing

national policies against resistant localities by use of the

removal jurisdiction when, in 1863, it provided “ That if

any suit or prosecution, civil or criminal, has been or shall

be commenced in any state court against any officer, civil

or military, or against any other person, for any arrest or

imprisonment made, or other trespasses or wrongs done

or committed, or any act omitted to be done, at any time

during the present rebellion, by virtue or under color of

any authority derived from or exercised by or under the

President of the United States, or any act of Congress,”

the defendant might remove the proceeding into a circuit

court of the United States. Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 81,

§5, 12 Stat. 755, 756. Certain procedural amendments to

the 1863 act were effected by the Act of May 11,1866, ch. 80,

14 Stat. 46, which also provided in its fourth section “ That

if the State court shall, notwithstanding the performance

Convention of 1814-1815, see 1 Morison & Commager, Growth

of THE A merican Republic 426-429 (4th ed. 1950).

Act of March 2, 1833, ch. 07, §3, 4 Stat. G32, 633. Concerning

South Carolina’s resistance to the successive tariffs, culminating

in the nullification ordinance, see 1 Morison & Commager, supra

470-485. The Force Act of March 2, 1833, responded to the South

ern threat not merely by extending the removal jurisdiction of the

federal courts, but by establishing a new head of habeas corpus

jurisdiction. Section 7, 4 Stat. 632. 634. See Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S.

391, 401 n. 9 (1963).

of all thing.'? required for the removal of the case to the

circuit court . . . , proceed further in said cause or prose

cution [before receipt of a certificate from the circuit court

stating that the removal has not been perfected] . . . , then,

in that case, all such further proceedings shall be void and

of none effect. . . . ”

Earlier in the same 18(16 session, Congress passed, over

the presidential veto, the first civil rights act, Act of April

9, 1866, eh. 31, 14 Stat. 27. The first and third sections of

the Act, reproduced below, significantly expanded federal

removal jurisdiction within the traditions of the 1815, 1833

and 1863 enforcement legislation:

“Be it evaded by the Senate and House of Repre

sentatives of the United States of America in Congress

assembled, That all persons burn in the United States

and not subject to any foreign power, excluding Indians

not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the

United States; and such citizens, of every race and

color, without regard to any previous condition of

slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punish

ment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly

convicted, shall have the same right, in every State and

Territory in the United States, to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence, to

inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and

personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all

laws and proceedings for the security of person and

property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and

to none other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.

“ S ec. 2. And be it further enacted, That any person

who, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regu

lation, or custom, shall subject, or cause to be subjected,

12

any inhabitant of any State or Territory to the depri\a-

tion of any right secured or protected by this act, or

to different punishment, pains, or penalties on account

of such person having at any time been held in a condi

tion of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a

punishment for crime whereof the party shall have

been duly convicted, or by reason of his color or lace,

than is prescribed for the punishment of white persons,

shall lie deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on con

viction, shall be punished by fine not exceeding one

thousand dollars, or imprisonment not exceeding one

year, or both, in the discretion of the court.

“ Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That the district

courts of the United States, within their respective

districts, shall have, exclusively of the courts of the

several States, cognizance of all crimes and offences

committed against the provisions of this act, and also,

concurrently with the circuit courts of the United

States, of all causes, civil and criminal affecting per

sons who are denied or cannot enforce in the courts or

judicial tribunals of the State or locality where they

may be any of the rights secured to them by the first

section of this act; and if any suit or prosecution, civil

or criminal, has been or shall be commenced in any

State court, against any such person, for any cause

whatsoever, or against any officer, civil or military, or

other person, for any arrest or imprisonment, tres

passes, or wrongs done or committed by virtue or un

der color of authority derived from this act or the act

establishing a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and

Refugees, and all acts amendatory thereof, or for re

fusing to do any act upon the ground that it rvould be

inconsistent with this act. such defendant shall have

the right to remove such cause for trial to the proper

district or circuit court in the manner prescribed by

13

the ‘Act relating to habeas corpus and regulating ju

dicial proceedings in certain cases,’ approved March

three, eighteen hundred and sixtv-three, and all acts

amendatory thereof. The jurisdiction in civil and crim

inal matters hereby conferred on the district and cir

cuit courts of the United States shall be exercised and

enforced in conformity with the laws of the United

States, so far as such laws are suitable to carry the

same into effect; but in all cases where such laws are

not adapted to the object, or are deficient in the pro

visions necessary to furnish suitable remedies and

punish offences against law, the common law, as modi

fied and changed by the constitution and statutes of

the State wherein the court having jurisdiction of the

cause, civil or criminal, is held, so far as the same is

not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the

United States, shall be extended to and govern said

courts in the trial and disposition of such cause, and,

if of a criminal nature, in the infliction of punishment

on the party found guilty.”

The 186(1 statute was reenacted by reference in the civil

rights act of 187fl,s and, with stylistic changes, became

Rev. Stat. §641; 8

8 The Enforcement Act of Mav 31, 1870, eh. 114, 5516-18, 16

Slat. 140, 144:

“ Sec. 16. And hr it further mar,ted, That all persons with

in the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same

right in every State and Territory in the United States to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence,

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings

for the security of person and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, pen

alties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and none

other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom to

the contrary notwithstanding. No tax or charge shall be im

posed or enforced by any State upon any person immigrating

thereto from a foreign country which is not equally imposed

and enforced upon every person immigrating to such State

14

“ Sec. 641. When any civil suit or criminal prose

cution is commenced in any State court, for any cause

-whatsoever, against any person who is denied or can

not enforce in the judicial tribunals of the State, or in

the part of the State where such suit or prosecution is

pending, any right secured to him by any law provid

ing for the equal civil rights of citizens of the United

States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States, or against any officer, civil or military,

or other person, for any arrest or imprisonment or

other trespasses or wrongs, made or committed by

virtue of or under color of authority derived from any

law providing for equal rights as aforesaid, or for

refusing to do any act on the ground that it would be

inconsistent with such law, such suit or prosecution

may, upon the petition of such defendant, filed in said

State court, at any time before the trial or final hearing

of the cause, stating the facts and verified by oath, be

removed, for trial, into the next circuit court to be

from any other foreign country; and any law of any State in

conflict with this provision is hereby declared null and void.

“ Sec. 17. And be it further enacted, That any person who,

under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or

custom, shall subject, or cause to be subjected, any inhabitant

of any State or Territory to the deprivation of any right

secured or protected by the-last preceding section of this act,

or to different punishment, pains, or penalties on account of

such person being an alien, or by reason of his color or race,

than is prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on conviction, shall be

punished by fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, or im

prisonment not exceeding one year, or both, in the discretion of

the court.

“ Sec. 18. And be it further enacted, That the act to pro

tect all persons in the United States in their civil rights, and

furnish the means of their vindication, passed April nine,

eighteen hundred and sixty-six, is hereby re-enacted; and sec

tions sixteen and seventeen hereof shall be enforced according

to the provisions of said act."

massu m ... —

■

15

liold in the district where it is pending. Upon the tiling

of such petition all further proceedings in the State

courts shall cease, and shall not be resumed except as

hereinafter provided. . . . ”

In 1911, in the course of abolishing the old Circuit Courts,

Congress technically repealed Rev. Stat. §6419 but carried

its provisions forward without change (except that removal,

jurisdiction was given the district courts in lieu of the cir

cuit courts) as §31 of the Judicial Code.10 Section 31 ver

batim became 2S U. S. C. §74 (1940),11 and in 194S, with

9 Judicial Code of 1911, §297, 36 Stat. 1087, 1168.

10 Judicial Code of 1911, §31. 36 Stat. 1087, 1096: .

“ Sec. 31. ’When any civil suit or criminal prosecution is

commenced in any State court, for any cause whatsoever,

against any person who is denied or cannot enforce in the,

judicial tribunals of the State, or in the part of the State where

such suit or prosecution is pending, any right secured to him

by any law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States, or against any officer, civil or military, or

other person, for any arrest or imprisonment or other tres

passes or wrongs made or committed by virtue of or under

color of authority derived from any law providing for equal

rights as aforesaid, or for refusing to do any act on the ground

that it would be inconsistent with such law, such suit or prose

cution may, upon the petition of such defendant, filed in said

State court at any time before the trial or final hearing of

the cause, stating the facts and verified by oath, be removed

for trial into the next district court to be held in the district

where it is pending. Upon the filing of such petition all fur

ther proceedings in the State courts shall cease, and shall not

be resumed except as hereinafter provided. . . . ”

11 28 U. S. C. §74 (1940):

“ §74. (Judicial Code, section 31.) Same; causes against

persons denied civil rights.

“ When any civil suit or criminal prosecution is commenced

in any State court, for any cause whatsoever, against any

person who is denied or cannot enforce in the judicial tri

bunals of the State, or in the part of the State where such

suit or prosecution is pending, any right secured to him by

any law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of the

16

changes in phraseology,12 it assumed its present form as

28 U. S. C. §1443 (195S) :13

‘•§1443. Civil rights cases.

“ Any of the following civil actions or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a State court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the

place wherein it is pending:

United States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States, or against any officer, civil or military, or other

person, for any arrest or imprisonment or other trespasses or

wrongs made or committed by virtue of or under color of

authority derived from any law providing for equal rights

as aforesaid, or for refusing to do any act on the ground

that it would be inconsistent with such law, such suit or prose

cution may, upon the petition of such defendant, filed in said

State court at any time before the trial or final hearing of

the cause, stating the facts and verified by oath, be removed

for trial into the next district court to be held in the district

where it is pending. Upon the filing of such petition all fur

ther proceedings in the State courts shall cease, and shall not

be resumed except as hereinafter provided.. . . ”

12 Revisor’s Note to 28 U. S. C. §1443 (1958) :

u

“Words ‘or in the part of the State where such suit or

prosecution is pending’ after ‘courts of such States,’ [sic]

were omitted as unnecessary.

“ Changes were made in phraseology.”

13 -Act of June 25, 1948, eh. G4G, §1443, 62 Stat. SG9, 93S. The

1948 Code made important changes in removal procedure. Prior

to 1948, a party seeking to remove a case or prosecution filed a

removal petition in the state court where the case was pending.

The state court passed upon the propriety of removal and granted

or denied the petition. Its denial was subject to direct review in

the state appellate courts and ultimately in the Supreme Court of

the United States, or to collateral attack by the filing of the record

in the lower federal court to which removal was authorized by

statute. See Metropolitan Casualty his. Co. v. Stevens, 312 U. S.

5G3 (1941). Under the 1948 Code the removal petition in “ any

civil action or criminal prosecution” is filed in the first instance in

the federal district court, 28 U. S. C. §1446(a) (1958), which alone

_____ -------------------------------------------- _ - . . . . . . . . — ■.; rP frU W fafct iwm.H »«*!<■• - m siid a tm iid j J

17

“ (1) Against any person who is denied or cannot

enforce in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof;

“ (2) For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights, or for refus

ing to do any act on the ground that it would be in

consistent. with such law.”

All of the statutes thus far traced from 1815 to the 1948

codification dealt with the removal of civil and criminal

actions against federal officers and others acting under

federal authority; and after 1866 specifically with the re

moval of civil and criminal actions against officers and

persons enforcing, or obedient to, federal civil rights legis

lation or who could not enforce their equal civil rights

in the state courts. In 1875, the fourth and last nineteenth

century civil rights act was enacted, granting to all per

sons within the United States further “ equal civil rights”

(Bev. Stat. §641, supra) enforceable under inter alia the

removal provisions of the act of 1866 codified in -§641.

Act of March 1, 1875, ch. 114, 18 Stat. 335. In the same

year, a distinct statutory development extended the removal

decides whether or not removal is allowable. Removal petitions in

civil actions must be fded within 20 days following receipt of the

initial pleading (or the first subsequent pleading stating a remov

able ease, where the case stated by the initial pleading is not re

movable), but removable petitions in criminal prosecutions may be

tded at any time before trial. 28 U. S. C. §1440(b), (c) (195S).

Filing of a copy of the removal petition with the clerk of the state

court effects removal and deprives the state court of jurisdiction

to proceed. 28 U. S. C. §1440(e) (1958). As under earlier practice,

the federal court to which removal is effected may stay subsequent

state proceedings, 28 U. S. C. §2283 (1958), and, in criminal prose

cutions, takes the defendant into federal custody by habeas corpus

28 U. S. C. §1446(f) (1958). * '

-xaaiiut .

jurisdiction in quite different directions and for quite dif-

ferent purposes, This was the Judiciary Act of 1S75 which,

beginning as a bill to expand the diversity jurisdiction,11 * * 14

was enacted as a regulation of the general civil (non-

civil-rights) jurisdiction of the circuit courts of the United

States. Act of March 3, 1S75, ch. 137, 18 Stat. 470. This

act for the first time15 gave the lower federal courts origi

nal federal-question jurisdiction; its first section gave

the circuit courts jurisdiction “ of all suits of a civil nature

at common law or in equity” involving the requisite juris

dictional amount and “ arising under” federal law, or be

tween citizens of different states, or citizens of a State and

foreign states or subjects, or between citizens of the same

State claiming under land grants of different States, or

where the United States was plaintiff. 18 Stat. 470. No

original civil-rights jurisdiction was given; this had been

specially created by the civil rights acts and was codified,

in pertinent part, in Rev. Stat. §629, Sixteenth, Seventeenth,

Eighteenth,16 now 28 U. S. C. §1343(1), (2), (3) (1958).17

Section 1 of the 1875 Judiciary Act also gave the circuit

courts exclusive criminal jurisdiction “ of all crimes and

offenses cognizable under the, authority of the United

States, except as otherwise provided by law, and concur

rent jurisdiction with the district courts of the crimes and

offenses cognizable therein.” 18 Stat. 470. Sections 2

11 F rankfurter & L andis, The Business of the Supreme Court

66-68 (1928).

15 Excepting the short-lived federalist Act of February 13, 1801,

ch. , 0 , §11, 2 Stat. 89, 92, repealed by the Act of March 8, 1802,

ch. Q , 2 Stat. 132.

1G The civil rights jurisdiction of the district courts was sepa

rately codified in Rev. Stat. §563, Eleventh, Twelfth.

17 Original federal jurisdiction in federal question, diversity, and

diversity land grant cases is now provided respectively by 28

U. S. C. §§1331, 1332, 1354 (1958).

19

through 7 of the act dealt with removal jurisdiction. They

authorized removal of “ any suit of a civil nature, at law

or in equity” involving the requisite jurisdictional amount

and “ arising under” federal law, or between citizens of

different States, or citizens of a State and foreign states

or subjects, or between citizens of the same State claiming

under land grants of different States, or where the United

States was plaintiff. IS Stat. 470-471. No civil-rights

removal jurisdiction was given, nor any removal jurisdic

tion over criminal cases. Section 5 of the act provided

that, whenever it appeared that jurisdiction of an original

or removed suit was lacking, the circuit court should dis

miss or remand the suit to the state court as justice might

require; “but the order of said circuit court dismissing or

remanding said cause to the State court shall be reviewable

by the Supreme Court on writ of error or appeal, as the

case may be.” 18 Stat. 472.18

The Act of March 3, 1887, ch. 373, 24 Stat. 552, amended

to correct enrollment by the Act of August 13, 188S, ch.

86G, 25 Slat. 433, extensively amended the Judiciary Act

of 1875. Although it left the original jurisdiction largely

unaltered (the jurisdictional minimum was raised- from

$500 to $2,000, and creation of diversity jurisdiction by

18 “ Sec. 5. That if, in any suit commenced in a circuit court or

removed from a State court to a circuit court of the United States,

it shall appear to the satisfaction of said circuit court, at any time

after such suit has been brought or removed thereto, that such

suit docs not really and substantially involve a dispute or con

troversy properly within the jurisdiction of said circuit court, or

that the parties to said suit have been improperly or collusively

made or joined, either as plaintiffs or defendants, for the purpose

of creating a ease cognizable or removable under this act, the said

circuit court shall proceed no further therein, but shall dismiss

the suit or remand it to the court from which it was removed as

justice may require, and shall make such order as to costs as shall

be just; but the order of said circuit court dismissing or remanding

said cause to the State court shall be reviewable by the Supreme

Court on writ of error or appeal, as the case may be.”

. a i i l iK iK M tt i

20

assignment of a negotiable instrument was precluded), the

Act of 3887 fundamentally rewrote the jurisdictional

grounds for, and the procedure in, civil removal cases.

Section 1, 25 Stat. 434-435, in pertinent part, provided:

“ That, the second section of said act [of 1875] he,

and the same is hereby, amended so as to read as fol

lows :

Sec. 2. That any suit of a civil nature, at law or

in equity, arising under the Constitution or laws of

the United States, or treaties made, or which shall he

made, under their authority, of which the circuit courts

of the United States are given original jurisdiction

JV the preceding section, which may now he pending,

or which may hereafter he brought, in any State court,

may be removed by the defendant or defendants therein

to the circuit court of the United States for the proper

district. Any other suit of a civil nature, at law or

m equity, of which the circuit courts of the United

States are given jurisdiction by the preceding section,

and which are now pending, or which may hereafter

be brought, in any State court, may be removed into

the circuit court of the United States for the proper

district by the defendant or defendants therein, being

non-residents of that State. And when in any suit

mentioned in this section there shall be a controversy

which is wholly between citizens of different States, and

which can be fully determined as between them, then

either one or more of the defendants actually inter

ested in such controversy may remove said suit into

the circuit court of the United States ,fo rthe. proper

district. And where a suit is now pending, or may be”

hereafter brought, in any State court, in which there

is a controversy between a citizen of the State in which

the suit is brought and a citizen of another State, any

, , r'• il’i «n»n , m.m, - ’■ ■ •-"*••• ̂ ---A., ._____________

21

defendant, being such citizen of another State, may

remove such suit into the circuit court of the United

States for the proper district, at any time before the

trial thereof, when it shall be made to appear to said

circuit court that from prejudice or local influence he

will not lie able to obtain justice in such State court, or

in any other State court to which the said defendant

may, under the laws of the State, have the right, on

account of such prejudice or local influence, to remove-

said cause: Provided, That if it; further appear that

said suit can be fully and justly determined as to the

other defendants in the State court, without being

affected by such prejudice or local influence, and that

no party to the suit will be prejudiced by a separation

of the parties, said circuit court may direct the suit

to be remanded, so far as relates to such other defen

dants, to the State court, to be proceeded with therein.

“ At any time before the trial of any suit which is

now pending in any circuit court or may hereafter be

entered therein, and which has been removed to said

court from a State court on the affidavit of any party

plaintiff that he had reason to believe and did believe

that, from prejudice or local influence, he was unable

to obtain justice in said State court, the circuit court

shall, on application of the other party, examine into

the truth of said affidavit and the grounds thereof,

and, unless it. shall appear to the satisfaction of said

court that said party will not be able to obtain justice

in such State court, it shall cause the same to be re

manded thereto.

“ Whenever any cause shall be removed from any

State court into any circuit court of the United States,

and the circuit court shall decide that the cause was

improperly removed, and order the same to be re

manded to the State court from whence it came, such

22

remand shall be immediately carried into execution,

and no appeal or writ of error from the decision of the

circuit court so remanding such cause shall be allowed.”

Section (i of the 1S87 act provided: “ That the last para-___. f cj

graph of section five of the act [of 1875; th^rid'ererrci'TTs

to the review provision of §5, supra p. 0 , n. 18] . . . and

all laws and parts of laws in conflict with the provisions of

this act, he, and the same are hereby repealed. . . . ” 25

Stat. 436-437. But §5 of the 1887 act contained this saving

clause:

“ S ec. 5. That nothing in this act shall be held,

deemed, or construed to repeal or affect any juris

diction or right mentioned either in sections six hun

dred and forty-one, or in six hundred and forty-two, or

in six hundred and forty-three, or in seven hundred and

twenty-two, or in title twenty-four of the Revised Stat

utes of the United States, or mentioned in section eight

of the act of Congress of which this act is an amend

ment, or in the act of Congress approved March first,

eighteen hundred and seventy-five, entitled ‘An act to

protect all citizens in their civil and legal rights.’ ” 19

Like the Act of 1875 which it amended, the Act of 1S87 did

not affect federal removal jurisdiction in criminal cases.

19 The provisions to which reference is made are as follows:

§G41 is the civil rights (civil and criminal) removal statute set

out supra p p ^ -Q ; §642 requires the clerk of the circuit court to

>—issiie'a writ of habeas corpus cum causa for the body of the defen

dant. who has removed any suit or prosecution under §641; §643

authorizes removal of “any civil suit or criminal prosecution”

against a federal revenue officer, or any officer or person acting

under the federal voting laws; §722 describes the law to be applied

in civil rights (civil and criminal) removed eases; title 24 of the

Revised Statutes is the civil rights title; §8 of the Judiciary Act

of 1875 provides for service of process ou absent defendants in civil

actions to enforce or remove liens or incumbrances on property

within the court’s jurisdiction; the Act of March 1, 1875, is the

fourth civil rights act. supra pij. Q .

........................................................ ........................* -

23

As indicated above, the Judicial Code of 1911 technically

repealed Rev. Stat. '§041, for the purpose of abolishing the

jurisdiction of the circuit courts. It carried forward §G41’s

exact provisions as a grant of civil rights (civil and crim

inal) removal jurisdiction to the district courts by virtue

of Judicial Code §31, supra, p. Q"7"nTl0. The civil (non-

civil-rights) removal provisions of the Judiciary Act of

1887, amending that of 1875, Avere carried forward virtu

ally unchanged as Judicial Code §§28-30. Section 28, the,

principal provision, reenacted inter alia the 1887 prohibi

tion of appellate revieAv of remand orders, supra pp. Q .20

20 3G Stat. 1094-1095. Italicized in pertinent part, §28 reads:

Sec. 28. Any suit of a civil nature, at law or in equity,

arising under the Constitution or Ihavs of tire United States,

or treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority,

of which the district courts of the United States are given

original jurisdiction by this title, which may now be pending

or AA’hieh may hereafter be brought, in any State court, may

be removed by the defendant or defendants therein to the

district court of the United States for the proper district.

Any other suit of a civil nature, at law or in equity, of which

the district courts of the United States are given jurisdiction

by this title, and which arc now pending or which may here

after be brought, in any State court, may be remo\red into the

district court of the United States for the proper district by

the defendant or defendants therein, being non-residents of

that State. And Avhen in any suit mentioned in this section

there shall be a controversy which is wholly between citizens

of different States, and which can be fully determined as be

tween them, then either one or more of the defendants actu

ally interested in such contnrversy may remo\7e said suit into

the district court of the United States for the proper district.

And where a suit is now pending, or may hereafter be brought,

in any Slate court, in which there is a controA’ersy between

a citizen of the State in which the suit is brought and a citizen

of another State, any defendant, being such citizen of another

State, may remove such suit into the district court of the

United States for the proper district, at any time before the

trial thereof, when it shall be made to appear to said district

court that from prejudice or local influence he will not be able

to obtain justice in such State court, or in any other State court

to which the said defendant may, under the laAvs of the State,

have the right, on account of such prejudice or local influence,

24

Section 297 of the Code, 36 Stat. 11GS, specifically repealed

the Judiciary Act of 1875 and §§1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 of the

Judiciary Act of 1887—that is, every part of the act of 1887

except the civil rights saving clause, section 5, supra p. O r - ~L

Section 297 further provided, 36 Stat. 1169:

“Also all other Acts and parts of Acts, in so far as

they are embraced within and superseded by this Act,

are hereby repealed; the remaining portions thereof

to be and remain in force with the same effect and to

the same extent as it this Act had not been passed.” 21

to remove said cause: Provided, That if it further appear that

said suit can be fully and justly determined as to the other

defendants in the State court, without being affected by such

prejudwe or local influence, and that no party to the suit

will lie prejudiced by a separation of the parties, said district

™“ ,rt "?ay direct the suit to be remanded, so far as relates to

such other defendants, to the State court, to be proceeded with

theiein. At any time before the trial of any suit which is now

pending in any district court, or may hereafter be entered

therein, ana which has been removed to said court from a

State court on the affidavit of any party plaintiff that he had

i'n?Wn I0 0''" and ,d,id belicve that- prejudice or local nfluence, he was unable to obtain justice in said State court

the distuct court shall, on application of the other party’

examine into the truth of said affidavit and the grounds there-

of, and, unless it shall appear to the satisfaction of said court

eonrtSTfd iPanty W11 >110t bc abl° to obtain justice in said State court, it shall cause the same to be remanded thereto. Whenever

Sl allr lJiC rTcTni0Ved f rom anV state court into any

dfni l t >C Umted States, and the district court .shall

, , le CaltSC, was '^Properly removed, and order the

sa ne to he remanded to the State court from whence it came,

Z fannZl vnn\cdinidV ™rried into execution, and

no appeal or writ of error from the decision of the district court

so remanding such cause shall bc allowed: Provided That no

case arising under an Act entitled “ An Act relating to the lia-

b lty of common carriers by railroad to their employees in

c i tan, cases approved April twenty-second, nineteen hun-

a iiv s l ei? ' l ° V “y amendl!1(mt thereto, and brought in

} Sta<( ™ " r\ of competent jurisdiction shall be removed

to any court of the United States.

-'Section 297 of the Judicial Code of 1911 was not affected bv

thc enactment of Title 28, U. S. C. in 1948. See 02 Stat 869 996.

rtr’-'i iiri -1 -- - -— ^ - «iV,;irn'l iTn

25

Sections 2S, 29 and 30 of the Judicial Code appear as 28

U. S. C. §§71, 72 and 73 (1940), respectively. By reason

of the abolition of the writ of error in all cases, civil and

criminal, in 1928," the sentence in §28 (ffsarryrng: :fon v a rd ^

the 1887 preclusion of review by “ appeal or writ of error,”

supra p ]v ,0 , n. 20. omits reference to the writ. It reads:

~~'t\ rT\T hen ever any cause shall be removed from any State

court into any district court of the United States, and the

district court shall decide that the cause was improperly

removed, and order the same to be remanded to the State

court from whence it came, such remand shall be immedi

ately carried into execution, and no appeal from the deci

sion of the district court so remanding such cause shall be

allowed.'” 28 II. S. C. §71 (1940). No other significant

change appears.23

The 1948 Code (A) reenacted the civil rights (civil and

criminal) removal jurisdiction without substantive change,

28 IT. S. C. §1443 (1958), supra■ pp. © f ‘ (B) significantly

broadened the scope of removal jurisdiction (civil and

criminal) in cases involving federal officers and persons

acting under them, 2S U. S. C. §1442 (1958); (C) substan

tially rewrote the jurisdictional bases of general civil re

moval jurisdiction (descendant from the Judiciary Acts of

1875,1887, the Judicial Code of 1911, §§28-30 and 28 U. S. C.

§§71-73 (1940)), 28 U. S. C. §1441 (195S) ;24 (D) con-

t c n

22 Act of January 31, 1928, eh. 14, 45 Stat. 54. The enactment

is general and has no special pertinence to removal cases.

23 Apart from (lie omission of reference to the writ of error, the

1940 sections differ from those of the 1911 Judicial Code only in

that 28 TJ. S. C. §71 (1940) reflects the Act of January 20, 1914,

eh. 11. 38 Stat. 278, limiting removal in actions brought against

railroads and common carriers for damages for delay, loss of, or

injury to property received for transportation.

21 §1441. Actions removable generally.

(a) Except as otherwise expressly provided by Act of Con

gress, any civil action brought in a State court of which the

26

\1

siderably altered the removal procedures for both civil and

criminal actions, 2S U. S. C. §§1446, 1447 (195S), see supra

pp. J®, n. 13, and (E) inadvertently omitted the provi

s ion of the earlier general civil removal statutes which pro

hibited appellate review of remand orders. The Act of

May 24, 1949, ch. 139, §84(b), 63 Stat. 89, 102, supplied

the latter omission by adding a new subsection (d) to 28

U. S. C. §1447. The 1949 act was an omnibus technical

amendment statute, intending no “ enactment of substantive

law, but merely correction of errors, misspellings, and in

accuracies in revision.” '*5 The House Report says that the

purpose of the new subsection is “ to remove any doubt

that the former law as to the finality of an order of remand

to a State court is continued.” 28 U. S. C. §1447(d) reads:

district courts of the United States have original jurisdiction,

may he removed by the defendant or the defendants, to the

district court of the United States for the district and division

embracing the place where such action is pending.

(b) Any civil action of which the district courts have origi

nal jurisdiction founded on a claim or right arising under the

Constitution, treaties or laws of the United States shall be

removable without regard to the citizenship or residence of

the parties. Any other such action shall be removable only if

none of the parties in interest properly joined and served as

defendants is a citizen of the State in which such action is

brought.

(c) Whenever a separate and independent claim or cause

of action, which would be removable if sued upon alone, is

joined with one or more otherwise non-removable claims or

causes of action, the entire case may be removed and the dis

trict court may determine all issues therein, or, in its discre

tion, may remand all matters not otherwise within its original

jurisdiction.

25 Mr. O’Connor in the Senate, 95 Cong. lice. 5827 (81st Cong.,

1st Sess. 5 /6 /4 0 ). Senator O’Connor reported the bill from the

Senate Committee on the Judiciary. 05 Cong. Rec. 5020 (81st

Cong., 1st Sess. 4 /26 /49 ).

20II. R. Rep. No. 352, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (1949), 2 U. S. Code

Cong. Serv., 81st Cong., 1st Sess., 1949. 1254, 1268 (1949).

“ (d) An order remanding a ease to the State court

from which it was removed is not reviewable on ap

peal or otherwise.”

By Title^ff) Section 901 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

passed in each house by an overwhelming vote, Congress

has amended 2S USC 1447 (d) to expressly provide for

review of remand orders in civil rights d^by appeal or

otherwise,” (Emphasis added.) ________ ____

Ordinarily, unless a contrary legislative purpose affirma

tively appears, statutes not affecting substantive rights,

“ but related only to the procedural machinery provided

to enforce such rights” are “applied to pending as well as

to future suits.” Bowles v. Stricldand, 151 F. 2d 419, at

420 (5th Cir. 1945). Hence, 28 USC 1447(d) is completely

extinguished as even an arguable bar to the exercise of

this Court’s authority to review the order of remand “ by

appeal or otherwise.” 27

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred in:

(1) remanding the case to the state court on the au

thority cited;

27 For other examples of cases following this rule see:

lhuncr v. United States, 343 U. S. 112 (1952) (statute with

drawing jurisdiction of District Court over Tucker Act claims

did not affect Government’s liability in pending legislation);

E.r parte Collett, 337 U. S. 55 (1949) (statute authorizing trans

fer of venue);

Orr v. United States, 174 F. 2d 577 (2d Cir.) 1949 (statute sav

ing from dismissal eases in which venue is improperly laid) ;

Schoen v. Mountain Producers Carp., 170 F. 2d 707 (3d Cir

1948) (statute authorizing transfer of venue, applied to avoid

forum non conveniens dismissal) ;

lloadley v. San Francisco, 94 U. S. 4 (1876), 1875 (statute mak

ing remand orders in civil removal cases reviewable by appeal or

I

1

I

|

28

(2) remanding the case to the state court sua sponte;

(3) remanding the case to the state court without first

hearing evidence and argument as to the correctness of the

uncontradicted allegations of the verilied removal petition.

Summary of Argument

By its motion to dismiss the appeal, the appellee attacks

the jurisdiction of this Court on the grounds (i) 28 IT. S..C.,

Sec. 1447(d) (1958) bars all appellate review of the Dis

trict Court’s remand order,28 and (ii) appellants’ attempts

to secure review in the Court werc^untimely under Fed.

Rules Crim. Pr. (37) (a) (2), and 54[BHI) (R. 26, 27).

Appellants take the position that: (A )(1) the remand

order is reviewable by a proceeding in the nature of' man- ̂

damns under 28 IT. S. C., Sec. 1651(1958); (2) on the

record before the Court the case may be properly enter

tained as on petition for writ of mandamus -^Apfi.

(B) 28 U. S. C., Sec. 1447(d)(1958) does not

apply to (1) criminal cases or (2) cases sought to be re

moved under the civil rights acts, 28 U. S. C., Sec. 1443

(1958); (C) whether or not the remand order is reviewable

by proceedings in the nature of mandamus under Sec. 1651,

the validity of appellants’ custody following remand of

their cases to the state court is cognizable by petition for

writs of habeas corpus to the judges of this Court under

,v r -* y

writ of error applied to authorize Supreme Court review of a

remand in a ease pending in the state courts at the time of pas

sage of the act and subsequently removed and remanded).

zs The statute precluding review of an order of remand is ex

pressly limited in its operation to instances where the district

court determines prior to final judgment that the cause was “ im

properly removed” ; i.e., where the removal petition fails to aver

the requisite jurisdictional facts. Traveler's Protective Ass’n of

America v. Smith, ct ah, 71 F. 2d 511 at 512 (4th Cir. 1934) (ap

peal dismissed; leave to fde petition for mandamus allowed). See

_ If. © , supra.

J *

:

28 U. S. C., Sec, 2241(c) (3) (1958), and in such proceeding,

which this Court may entertain as timely and properly

before it, the validity of the order of remand may he tested;

or (D), alternatively to all of the foregoing, appellants’

verified petition for removal may properly be construed as

a petition for writs of habeas corpus under 28 U. S. C.,

Sec. 2241(c)(3)(1958), the denial of which is appealable

to this Court under 28 U. S. C., Sec. 2253(1958); or (E)

(1) the ten day appeal time allowable under Criminal Rule

37(a)(2) has no application to review of the remand orders

Appellants’ verified removal petition stated a removal

claim cognizable under both subsections (1) and (2) of

28 U. S. C. 1443(1958). Sufficient facts were alleged to

support removal upon the basis of the authority relied

upon by the District Court to remand. The removal peti

tion stated facts adequate to show that appellants are per

sons acting “under color of authority” within the meaning

of subsection (2), Section 1443, authorized to remove crim

inal prosecutions. The facts averred, if proved, authorize

removal under this subsection.

The substantially probable case doctrine adhered to by

the Court below is too restrictive a construction of sub

section (1) Section 1443, because (1) it is founded upon

unreasonable assumptions about state judges, and (2) if

those unreasonable assumptions are indulged, the Suprem

acy Clause renders them untenable. Thus, the authorities

relied upon to support remand aj’e only plausible if no

more than a common sense view of their rationale is taken,

limiting each case, especially Kentucky v. Powers, 201

1’ . S. 1 (1906), to its own peculiar facts.

Failure to attacli copies of the indictments does not jus

tify remand because (1) remedy is available by certiorari

or other appropriate order, and (2) absent abuse of dis-

j« ; ( 'i! * i iY* i<Tr* “ ■—— « T> i ,MttWn-ffi1ir:'ri itfrtfriWi1~^i—*4-' ̂ ; - * v-* ~ ̂ - k - — ■«$

30

crotion, such matter is wholly committed to district judges’

discretion, and (3) such requirement would unduly frus

trate resort to federal courts to vindicate equal civil rights.

Appellants’ position on this appeal as stated supra,

p age j© , makes it unnecessary for them to respond to / , . . .

^appellee’s point 5 (Tv. 24).

A R G U M E NT

I

(A) Reserving questions presented by Section 1447(d),

the remand order is reviewahle in proceedings in

the nature of mandamus which are properly before

the court

(1) Under the all writs section of the Judicial Code,

28 U. S. C. Section 1651 (1958), this Court has power to

issue orders in the nature of mandamus29 in aid of its ap

pellate jurisdiction. Pursuant to 28 U. S. C. Section 1291

(1958) this Court has authority to review final decisions

entered in the Court below in removed criminal prosecu

tion. Hence, review “ agreeable to the usages and principles

of law” (section 1651) of interlocutory orders in the cases

is allowable, United States v. Smith, 331 U. S. 469 (1947);

LaBuy v. IJotces Leather Co., 352 IT. S. 249 (1957); Platt

v. Minnesota Mining tC Mfg. Co., 84 S. Ct. 769 (1964) (by

implication), particularly where the interlocutory order

prevents the cases from coming to final judgment in the

District Court and thus defeats the normal appellate juris-

2,1 Rule 81(h) Fed. R. Civ. Pro., formally abolishing the writ of

mandamus and providing that all relief previously available by

mandamus may be obtained by appropriate action or motion, does

not. affect the scope of relief in the nature of mandamus which

a federal appellate court may order. LaBuy v. Howes Leather Co.,

•152 U. S. 249 (1957) (by implication).

■ - - - - - - w»: „1. i .» r»-fJ l..Mi»'

31

diction of this Court under section 1291. McClellan v.

Garland, 217 U. S. 268 (1900).

“Applications for a mandamus to a subordinate coui t

are warranted by the principles and usages of law in cases

where the subordinate court, having jurisdiction of a case

refuses to hear and decide the controversy . . . ” Ex parte

Newman, 14 Wall. 152, 165 (1877) (dictum). See Insurance

Co. v. Comstock, 16 AYal.U© (1872) (issuing advisory opin-

—ton'Td do service for mandamus). Grounding its rationale

upon Newman and Comstock, the United States Supieme

Court in Railroad Co. WiswaU, 23 A Call. 507 (1874), decided

that an order of a federal trial court remanding a removed

case to the state court was reviewable by mandamus.30 That

ruling lias never been questioned in subsequent cases. See

Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 U. S. 4, 5 (1875); Babbitt v.

Clark, 103 U. S. 606 (1880); Tamer v. Farmers’ Loan <C

Trust Co., 106 U. S. 552, 555 (1882); Gay v. Ruff, 292 II. S.

25, 28 n. 3 (1934); Employers Reinsurance Corp. v. Bryant,

299 U. S. 374, 378 (1937); also Missouri Pacific Ry. Co. v.

Fitzgerald, 160 U. S. 556, 580 (1896); United States v.

Rice, 327 U. S. 742, 749-750 (1946). It is accordingly clear

that, but for any question arising from 28 U. S. C. Section

1447 (d), “ the power of the court to issue the mandamus

would be undoubted.” In re Pennsylvania Co., 137 U. S.

451, 453 (1890).

(2) It is evident also that this Court may properly

treat the present case as though before it on application for

The WiswaU case was decided before the creation of the Courts

of Appeals in 1831. at a time when the Supreme Court of the United

States had the same immediate appellate superintendence over the

old Circuit Courts that the Courts of Appeals now have over the

District Courts. In Wiswall the Court dismissed a writ of error

to the Circuit Court on the ground that the proper remedy was

an application to the Court for mandamus.

32

relief in the nature of mandamus. Fed. Rules Civ. Pro.

81 (b) provides that “ Relief heretofore available bj’’ man

damus . . . may be obtained by appropriate action or by

appropriate motion under the practice prescribed in [the]

. . . rules.” Appellants’ motion for stay pending appeal

(App. ]). ), to which were attached copies of the

rverTfieclremova] petition and the remand order (R. 2, 10),

adequately served to put before this Court a proceeding in

the nature of mandamus. It is unimportant that the motion

did not speak in terms of mandamus. See United States

v. Morgan, 346 U. S. f>02 (1954); Heflin v. United States,

358 U. S. 415 (1959); United Slates v. Morgan, 358 U. S.

415 (1959); Mitchell y. United Stales, 368 U. S. 439 (1962);

Coppedge v. United States, 369 U. S. 438, 442 n. 5 (1962);

Fed. Rule Crim. Pro. 52(a).

(It) §1447 (d) does not bar review of

the remand order

(1) Section 1447(d) provides broadly: “ An order re

manding a case to the State court from which it was re

moved is not reviewable on appeal or otherwise.” On its

words alone the statute appears so sweeping as to bar re

view of any remand order issued by any federal court in

any case. But, as shown by the only pertinent legislative

document, the purpose of this undebated technical enact

ment of 1949 was to “ remove any doubt that the former

law as to the finality of an order of remand to a State

court is continued.” See p. Q supra. Thus, notwithstand

ing the comprehensive statutory wording, it would be ab

surd, for example, to suppose that an enactment which the

Senate was told by the floor manager of the bill “ [ i]n no

sense is . . . any enactment of substantive law,” 31 meant

31 Senator O’Connor at 95 Cone. Rec. 5827 [8]st Cong., 1st Sess.

5/6/49), quoted in part supra p. at n.(X.

iwrrmnn^i

'S£k-ua---------------a o u ri-aitfiMn. — •—- ........ . ............. •■-■ ■ ■■' -■ - ■ :--i „

33

to overrule the long-standing doctrine that orders of a Court

of Appeals directing remand of a removed case are re-

viewable by the Supreme Court on certiorari. E.g., Gay

v. Ruff, 292 F. S. 25 (1934); Aetna Casualty <6 Surety Co.

v. Flowers, 330 V. S. 404 (1947). The sweeping language

of the 1949 enactment plainly seems to have this unintended

overreach, for it omits the limitation of the original 1887

statute to “decision of the circuit court” (sec p.

and the limitation of the 1911 Judicial Code to “decision

of the district court” (see pp. 20 supra), ujtoiu-

which limitation Gay and Flowers rested. BiiTThe statute

cannot rationally be given the effect which its words appear

to command. Plainly §1447(d) looks broader than it is.

The statutory history set out at pp. ©' supra also dem

onstrates that when Congress barred review of a remanded

“ case” in §1447(d) it meant a civil ease and did not mean

to preclude review of remand orders by mandamus in crim

inal cases. The criminal removal jurisdiction of the federal

courts was 1he creature of a series of relatively limited

and specific enactments throughout the nineteenth century

—principally the acts of 1815, 1833, and 1866, and related

enactments.32 These concerned federal officers, persons act

ing under them, and civil rights defendants; the statutes

invariably spoke of “ suit or prosecution,” or “ suit or prose-

eution, civil or criminal.” See pp. 0 "7 ^The general

civil removal jurisdiction was created, and its scope altered

from time to time, by an entirely different line of statutes,33

of which the Judiciary Acts of 1875 and 1887 are the most

See pp.important. See pp. © — supra. The removal

of these statutes are in terms limited to civil actions:

suit of a civil nature, at law or in equity.” See pp

/

2 3

a - a ?

- C - >

provisions

“ any

G - / ? ,

32 Citations to the statutes are collected in H art & W e c h sl e r ,

T in : F ederal Courts a n d t h e F ederal S y s t e m 1147-1150 (1 9 5 3 ) .

33 See H art & W e c h sl e r , su p ra note">t5))Ht 1019-1020.

% /

3 2

•>____ I. « = ^ H

84

supra. Section 5 of the 1875 act for the first time authorized

review of remand orders by appeal or writ of error: it pro

vided that “ in any suit commenced in a circuit court or

removed from a State court to a circuit court of the United

States,” a circuit court finding that “ such suit does not

really and substantially involve a dispute or controversy

properly within the jurisdiction of said circuit court,”

should “ dismiss the suit or remand it to the court from

which it was removed,” “ but the order of said circuit court

dismissing or remanding said cause to the State court shall

be. reviewable by the Supreme Court on writ of error or

appeal, as the case may be.” See p. ©__. n. 18 supra (em

phasis added). “ Cause” is used intorchangealiTy'witTrrrsuIt”

and refers to the only “ suits” with which the act deals:

civil suits. This is clear beyond dispute, for the same

provisions of §5 which authorize review of an “ order . . .

remanding” a removed suit also authorize review of an

“ order . . . dismissing” a removed or original suit, and it

has never been supposed that the act of 1875 gave the

Government a right of appeal in criminal cases. See United

States v. Sanges, 144 U. S. 310 (1892). Like the act of

1875, the act of 1887 dealt, in its removal provisions, only

with suits “ of a civil nature, at law or in equity.” See

p. supra. It was in these provisions that the Congress,

"reversing its decision of 1875. for the first time enacted the

preclusion of review which is the predecessor of the present

$1447(d). Section 1 of the act of 1887"1 amended §2 of the

1875 act substantially to circumscribe the civil removal

jurisdiction of the circuit courts and. in so doing, provided

that whenever a circuit court remanded a cause as improp

erly removed, “ such remand shall be immediately carried

into execution, and no appeal or writ of error from the

31 As amended to correct enrollment l>v the act of 1888. See

pp. O supra.

35

decision of (he circuit court so remanding such cause shall

be allowed.” See pp. O supra.

— Snch a disallowance of “appeal or writ of error” in 1887

could not conceivably have been intended to apply to crimi

nal cases, because prior to 1889 there was in the federal

courts “no jurisdictional provision for appeal or writ of

error in criminal cases.” Carroll v. Untied Stales, 354 II. S.

394, 400 n. 9 (1957); Bator, Finality in Criminal Law and

Federal Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners, 76 H arv. L.

Rev. 441, 473 n. 75 (19G3). The act of 1875 had given none,

and there was no other.35 Moreover, the exclusive preoccu

pation of the 1887 statute with matters of civil removal is

evident. The act was a compromise between the House and

Senate as to the means of relieving the lower federal courts

which were “ overloaded with business.” 30 The overload

had been a subject of Congressional agitation during a

number of years preceding 1887, and the agitation had con

cerned civil cases.36 37 All of the changes of law worked by

the jurisdictional provisions of the act of 1887 were changes

36 Of course in civil cases, which were clearly within the scope

of preclusion of review (being in 1887 revie,wable either by appeal

or writ of error, and the class of case with which the 1887 statute

was concerned), this Court subsequently held that the effect of the

statute was to bar mandamus in those cases where it barred appeal

or writ of error. In re Pennsylvania Co., 137 U. S. 451 (1890); cf.

United States v. Rice, 327 U. S. 742 (1946). This was concluded on

reasoning that, where Congress had shut one door tight, it did not

intend that another stand open. Neither the cases nor the reasoning

have pertinency to the question of the applicability of the review

bar to criminal removal proceedings unless it can be shown on

independent grounds that, with respect to such proceedings, Con

gress did intend to shut one door tight. Such an intent is tlie more

doubtful because the only door then open in criminal cases was

mandamus, and the statute does not speak of mandamus.

30II. R. Rep. No. 1078, 49th Cong., 1st Sess. (1886), p. 1.

37 The story is told in F rankfurter & Landis, The Business of

tiie Supreme Court 56-102 (1928).

J W U -

IS

J

, 2 3

affecting civil cases.38 Contemporary comment on the act, of

1SS7 is concerned exclusively with civil cases.30 In this con

text, the provision barring review of remanded “ cause[s]

can only plausibly be read to refer to civil causes. Con

gress dealt with nothing else, considered nothing else, in

1887. The Judicial Code of 1911 merely carried forward the

1887 provision without change,40 and this was the “ former

law” 41 which Congress reinstated when it enacted §141-7 (d)

in 1949.

None of the authorities cited by the appellee in its mo

tion to dismiss (R. 28) holds that §1447(d) applies to crim

inal cases, and appellants have been unable to find any case

so holding. Snypp v. Ohio, 70 F. 2d o35 (6th Cir. 1934),

seems to be the only criminal case in which the issue

might have been raised and, although the court in Snypp

appears tentatively disposed to reject the specific con

tention that the 1887 provision precluding review of re

mand orders applies only to cases removed under the 18S7

removal provisions, the court leaves the issue undecided

and affirms the remand order on the merits. Of course,

it is not appellants’ contention, as it was Snypp’s, that the

§1447(d) bar is limited to cases sought to be removed

under so much of the removal statutes as presently continue

/

J

r<>

1 7

J

■iH

V

It,

3S See P IV /O supra.

•— See D u st y , T he R e m o v a l of C a u s e s F rom S t a t e to F ederal

C ourts 207 (3d ed. 1893); D il l o n , R e m o v a l of C au ses F rom