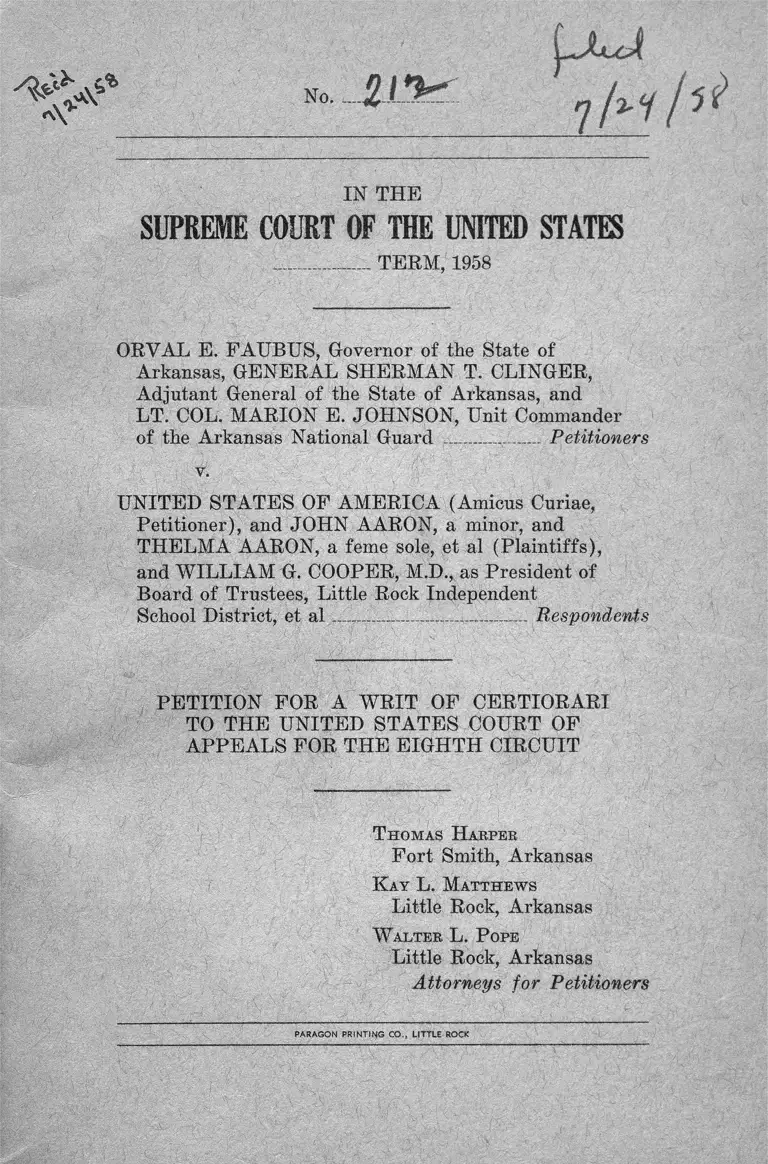

Faubus v. United States Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

Public Court Documents

July 24, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Faubus v. United States Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, 1958. a204f977-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cc90ab00-44e9-4a48-8433-17020585c2fa/faubus-v-united-states-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-eighth-circuit. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

No. _

LJ juA

2 ) ^ Tfafr*

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

..._ _ TERM, 1958

ORVAL E. FAUBUS, Governor of the State of

Arkansas, GENERAL SHERMAN T. CLINGER,

Adjutant General of the State of Arkansas, and

LT. COL. MARION E. JOHNSON, Unit Commander

of the Arkansas National Guard ________Petitioners

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (Amicus Curiae,

Petitioner), and JOHN AARON, a minor, and

THELMA AARON, a feme sole, et al (Plaintiffs),

and WILLIAM G. COOPER, M.D., as President of

Board of Trustees, Little Rock Independent

School District, et al ______________ _______ Respondents

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

T homas H arper

Fort Smith, Arkansas

K ay L. M atth ew s

Little Rock, Arkansas

W alter L. P ope

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

PARAGON PRINTING CO., LITTLE ROCK

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below 1

Jurisdiction ----- 2

Questions Presented --------------------------------------- -—-------- —------------ 2

Statutes Involved ------------------------ —------ -------- ----- -------------------- - - 3

Statement ____________________________ _________ _— -------—- 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ -......-......... . - 12

Conclusion _________________________ 29

Appendix A

Opinion Below _________________ 23a

INDEX—(Continued)

Cases Cited

PA G E

Aaron, et al v. Cooper, et al, 143 F. Supp. 855 ___ ..._4,6

Aaron, et al v. Cooper, et al, 243 F. 2d 361 ___________________ 4

Berger, et al v. United States, 255 U.S. 22, 41 S. Ct. 230,

65 L ed 481 ________ ...____________________________ ___ 18,19,20

Birmingham Loan and Auction Co. v. First National Bank of

Anniston, 100 Ala. 249, 13 So. 945, 946 ____________________ 26

Bishop v. United States, 8 Cir., 16 F. 2d 410, 411 __________12,15,16

Bommarito v. United States, 8 Cir. 61 F. 2d 355 ______________12

Craven v. United States, 1 Cir., 22 F. 2d 605,

cert den 276 U.S. 627; 72 L ed 739 ______________________12,18

Ebel v. Drum, 55 F. Supp. 186 _________________________________24

Fierstein v. Piper Aircraft Corporation, D. C., 79 F. Supp. 217 ___ 24

General Gronze Corporation, et al v. Cupples Products

Corporation, et al, 9 F.R.D. 269 _______________________ ...23

Knapp v. Kinsey, et al, 6 Cir., 232 F. 2d 458, 466,

cert den 352 U.S. 892 ______________________ 21

Korer v. Hoffman, 7 Cir., 212 F. 2d 217 _____ __________________ 19

Lewis v. United States, 8 Cir., 14 F. 2d 369 _________________ .19

Magee v. McNany, 10 F.R.D. 5 ___________ 24

Morris v. United States, 8 Cir., 26 F. 2d 444 ______________________ 20

Murchison in re, 349 U.S. 133, 99 L ed 942 _____________ 18

Nations v. United States, 8 Cir., 14 F. 2d 507, cert den 273

U.S. 735, 71 L ed 866 _____ ___ __ __________ _______ _________19

Scott v. Beams, 10 Cir., 122 F. 2d 777 ________________________ 12,19

Truncale v. Universal Pictures Company, 82 F. Supp. 576 ______24

Tucker v. Kerner, 7 Cir., 186 F. 2d 79, 23 A.L.R. 2d 1027 _________ 19

Universal Oil Products v. Root Refining Co., 328 U.S. 575 ___ __27

Statuies

District Courts, Title 28, U.S.C.A., Section 144 __________________3,12

Rules

Rule 12 A Federal Rules of Civil Procedure __________________ 4,14

Rule 15 (d), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ______ ...2,3,8,9,23,24

Rule 21, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure _____________________4,8,24

Text Books

American Jurisprudence, Volume 2, page 679 ____________________ 26

C.J.S., Volume 43, Injunctions, Section 35 ______________________ 22

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

__________ TERM, 1958

ORVAL E. FAUBUS, Governor of the State of

Arkansas, GENERAL SHERMAN T. CLINGER,

Adjutant General of the State of Arkansas, and

LT. COL. MARION E. JOHNSON, Unit Commander

of the Arkansas National Guard __________ Petitioners

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (Amicus Curiae,

Petitioner), and JOHN AARON, a minor, and

THELMA AARON, a feme sole, et al (Plaintiffs),

and WILLIAM G. COOPER, M.D., as President of

Board of Trustees, Little Rock Independent

School District, et a l ________ _— ---- ---------Respondents

PETITION FOR A 'WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners, Orval E. Faubus, Governor of the State

of Arkansas, General Sherman T. Clinger, Adjutant Gen

eral of the State of Arkansas, and Lt. Col Marion E.

Johnson, Unit Commander of the Arkansas National

Guard, pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit entered in the above case on April

28, 1958.

CITATIONS OF OPINION BELOW

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit in the above case, is reported 254 Fed. (2), page

797.

2

JURISDICTION

The Judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit was entered on April 28, 1958. The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.A.

Section 1254 (1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Was the Affidavit of Prejudice filed less than

ten days after the filing of the Petition for Preliminary

Injunction, and less than ten days after notice of hearing

on the petition a “ timely” affidavit required by Section

144 of Title 28 U.S.C.?

2. Was the Affidavit of Prejudice sufficient to show

personal bias or prejudice as required by Section 144, Title

28, U.S.C.t

3. Did the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas have jurisdiction to order

the Attorney General and the United States Attorney to

file a petition for injunction against the petitioners herein?

4. Did the United States District Court have juris

diction, pursuant to Rule 15 (d) and Rule 21 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to make Governor Fau-

bus and the two Arkansas National Guard officers ad

ditional parties defendant in the case of John Aaron, et al,

plaintiffs and William G. Cooper, et al, defendants?

5. Did the petition of the United States filed as

amicus curiae state a cause of action against Governor

Faubus and the two Arkansas National Guard officers

and did the United States, as amicus curiae have au

thority to seek injunctive relief?

6. Did the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Arkansas have jurisdiction to proceed

3

to trial on the Supplemental Complaint of the original

plaintiffs in the case of John Aaron, et al v. William G.

Cooper, et al, in which Governor Faubus and the two

Arkansas National Guard officers were named as addi

tional defendants on the day on which said Supplemental

Complaint was filed and without notice to the additional

defendants?

STATUTES, RULES, ETC.

Title 28, U.S.C.A. Section 144:

“ Whenever a party to any proceeding in a

district court makes and files a timely and sufficient

affidavit that the judge before whom the matter

is pending has a personal bias or prejudice either

against him or in favor of any adverse party, such

judge shall proceed no further therein, but another

judge shall be assigned to hear such proceeding.

The affidavit shall state the facts and the rea

sons for the belief that bias or prejudice exists, and

shall be filed not less than ten days before the be

ginning of the term at which the proceeding* is to

be heard, or good cause shall be shown for failure

to file it within such time. A party may file only

one such affidavit in any case. It shall be accom

panied by a certificate of counsel of record stating

that it is made in good faith. ’ ’

Rule 15 (d), F.R.C.P.:

“ Supplemental Pleadings. Upon motion of a

party the court may, upon reasonable notice and

upon such terms as are just, permit him to serve a

supplemental pleading setting forth transactions or

occurrences or events which have happened since

the date of the pleading sought to be supplemented.

I f the court deems it advisable that the adverse

party plead thereto, it shall so order, specifying

the time therefor.”

4

Rule 21, F.R.C.P.:

“ Misjoinder and Non-Joinder of Parties. Mis

joinder of parties is not ground for dismissal of

an action. Parties may be dropped or added by

order of the court on motion of any party or

of its own initiative at any stage of tbe action and

on sucb terms as are just. Any claim against a

party may be severed and proceeded with separ

ately.”

Rule 12 (a), F.R.C.P.:

“ Defenses and Objections— When and How

Presented. When Presented. A defendant shall

serve his answer within 20 days after the service

o f the summons and complaint upon him, unless

the court directs otherwise when service of process

is made pursuant to Rule 4 (e). . . . ”

STATEMENT

Prior to the opening of the 1956-1957 term of the

Little Rock Public Schools (February 8, 1956) John Aaron

and others, Negroes of school age, filed a class suit in

the United States District Court against the members of

the school board seeking complete and immediate integra

tion of the races in the Little Rock Public Schools. The

school board answered the complaint and submitted its

plan and program for the integration o f the races. See

Aaron, et at v. Cooper, et al, 143 Fed. Sup. 855, affirmed

243 Fed. 2d, 361. The program of the school board was

designed to start integration at the Little Rock Central

High School at the opening of the school on September

3, 1957. The alleged interference with the enforcement

of the decree of the District Court in said Aaron v. Cooper

case was the basis of federal jurisdiction in the United

States Distict Court.

It was alleged in the petition of the United States

that on September 2, 1957, Governor Faubus called out

5

the Arkansas State National Guard under an order to

prevent Negro students from entering any school in the

city theretofore attended only by white students and to

prevent white school children from entering any school

theretofore attended only by Negro school children (R.7).

Units of the Guard were stationed in front of the Little

Rock Central High School and nine Negro school children

were kept away from the entrance to the school. On

September 3, 1957, the school board issued a public notice

requesting Negro students not to attend the school and

the board petitioned the United States District Court for

a temporary stay of integration (R .l). On the same day

the District Court ordered the school board to appear

before it at 7 :30 p.m. and show cause why the Court

should not order immediate enforcement of the plan of

integration approved by the Court on August 27, 1956

(R .l). At the hour and day fixed in the Court’s order

a hearing was held and thereafter on the same day the

Court entered an order directing the school board to

integrate the Little Rock Central High School “ forthwith”

(R.3). On the following day, September 4, 1957, United

States District Judge Ronald N. Davies issued a letter-

order to United States Attorney Osro Cobb requesting

him “ to begin at once a full, thorough and complete in

vestigation to determine the responsibility for interfer

ence with said order” and “ to report your findings to

me with the least practicable delay” (R.3.-4).

The United States Attorney, as ordered, began an

investigation and made a report to Judge Davies. Upon

receipt of this report Judge Davies made another order

in which he stated that it appeared that Negro students

are not being permitted to attend Little Rock Central

High School in accordance with the plan of integration of

the Little Rock school directors as approved by the Court.

The Court then made an order directing the Attorney

6

General of the United States and the United States At

torney for the Eastern District of Arkansas to appear in

the case of Aaron, et al v. Cooper, et al as amici curiae

and “ to file immediately a petition against Orval E.

Faubus, Governor of Arkansas, Major General Sherman

T. Clinger, Adjutant General, Arkansas National Guard,

and Lt. Colonel Marion E. Johnson, Unit Commander,

Arkansas National Guard, seeking such injunctive and

other relief as may be appropriate to prevent the exist

ing interferences with the obstructions to the carrying

out of the orders heretofore entered by this court in this

case” . This order was made September 9, 1957 (R.5-6).

On September 10, 1957, a petition was filed in the

United States District Court by the United States of

America designated as amicus curiae against Orval E.

Faubus, Governor of the State of Arkansas, and the two

National Guard officers above named. The petition re

ferred to the court order of August 28, 1956, approving

the school board’s plan of integration, which provided

that jurisdiction was retained for the purpose of entering

such further orders as might be necessary to effect the

plan of integration.

Said petition alleged that Governor Faubus and the

State National Guard officers had stationed troops at

the Central High School under orders “ to place off limits

to white students those schools for colored students and

to place o ff limits to colored students those schools here

tofore operated and recently set up for white students.

This order will remain in effect until the demobilization of

the Guard or until further orders” ; that said troops,

pursuant to orders, had been and still were preventing and

restraining eligible Negro students named in the petition

from attending the school.

Said petition of the United States further alleged

that on September 3, 1957, the Little Rock School Board

was ordered to integrate forthwith and that on September

7, 1957, the Court denied an application by the school

board for a stay of the order made September 3.

Said petition further alleged that the acts of Governor

Faubus and the Guard officers in preventing the Negro

students from attending the school obstructed the effectua

tion of the Court’s orders of August 28, 1956, and Septem

ber 3, 1957, contrary to due and proper administration of

justice, and that it was necessary that Governor Faubus

and the officers “ be made additional parties defendant

and enjoined from obstructing and interfering with the

carrying out of said orders of the Court” .

The petitioner prayed that the Governor and said

officers be made parties defendant and that a preliminary

injunction and a permanent injunction issue enjoining

and restraining them, their agents, servants, employees,

attorneys and all persons in active concert or participa

tion with them, from obstructing or interfering in any

way with the carrying out of the said orders of the Court

(R.6-9).

Said petition of the United States was filed on Sep

tember 10, 1957. On the same day, without notice to the

respondents (petitioners here), the Court entered an order

making them parties defendant and setting a hearing on

the prayer for a preliminary injunction at 10:30 a.m.,

September 20, 1957. In this order the Court set forth

that it appeared, “ from the petition of the United States

as amicus curiae” filed in conformity with the Court’s

order of September 9, 1957, that in the interest of the

proper administration of justice, Governor Faubus, Gen

eral Clinger and Colonel Johnson should be made addi

tional parties defendant to prevent the continued obstrue-

8

tion of, and interference with the carrying out and ef

fectuation of the orders of the Court made on August

28, 1956, and September 3, 1957. The Court stated that

the order was made pursuant to Rules 15 (d) and 21

F.R.C.P. (R.9-10).

In Judge Davies’ letter of September 4, 1957, to

United States District Attorney Cobb he stated, “ I am

advised this morning that this Court’s order directing

the integration of the Little Rock schools . . . has not

been complied with due to alleged interference with the

Court’s order” (R.3-4). He did not give the source

of this advice. Three days later in denying the petition

of the school board for a stay of integration alleged to

be due to existing tension at the Central High School

Judge Davies stated: “ The Chief Executive of Little

Rock has stated that the Little Rock Police have not

had a single case of inter-racial violence reported to

them and there has been no indication from sources avail

able to him that there would be any violence in regard

to this situation” (R.13). The source of this informa

tion was not revealed. The Mayor of Little Rock had

not been a witness in any of the proceedings.

On September 19 Governor Faubus filed an Affidavit

of Prejudice setting forth in detail the reasons why the

affidavit could not have been sooner filed and the causes

that disqualified Judge Davis from presiding at the trial

of the issues of law and fact in the case (R.11-15).

On September 20, the day set in the Court’s order

of September 10 for a hearing on the petition for pre

liminary injunction, Governor Faubus and the officers

of the State National Guard filed a motion to dismiss

the petition of the United States against them, setting

forth these six separate grounds for such dismissal:

9

1. The Court was without authority to make the

order herein dated September 10, 1957.

2. The petition was illegally and improperly filed

herein because it related to matters of a different nature

from the subject invloved in the original action.

3. The petition was prematurely filed under Rule

15 (d) of the Rules of Civil Procedure for the United

States District Courts.

4. The petitioner, the United States of America, is

wholly without authority to file and maintain this action

against the respondents, and the Court is wholly without

jurisdiction to entertain said petition or to grant any

relief thereon.

5. The petitioner, seeking a preliminary injunction

and a permanent injunction, is not the real party in

interest in this litigation and, for this reason, is without

authority to maintain the action set forth in the petition.

6. This Court is wholly without jurisdiction of the

persons of respondents and the subject matter of the

petition, because

(a) The petition is in truth and in fact an attempted

action against the Sovereign State of Arkansas. The

State of Arkansas is actually the real respondent and

party in interest and this Court has no jurisdiction of

an action against the State of Arkansas:

(b) This Court is wholly without jurisdiction to ques

tion the judgment and discretion of the respondent, Orval

E. Faubus, as Governor of Arkansas, and other respondents

subordinate to him, in performing their duties made

mandatory upon them by the Constitution and laws of

the State of Arkansas (R.17-18).

Respondents also filed a motion to dismiss for failure

to convene a Three Judge Court (T.19).

10

The United States as amicus curiae then filed a motion

to strike the Affidavit of Prejudice (R.15-17).

The original plaintiffs, John Aaron, et al, had on the

11th day of September, 1957, filed a motion for leave

to file a supplemental complaint and add additional par

ties. No notice of the filing of this motion was given

to these petitioners (respondents below) and no response

was made thereto by them or any one for them (R.10-11).

All of these motions were on September 20 imme

diately set for hearing, and counsel were directed to pre

sent the motions. As the motions were presented and

arguments heard, the Court without delay made rulings

thereon. The motion of the United States as amicus

curiae to strike the Affidavit of Prejudice was sustained

(R.16-17). The motion of the original plaintiffs for leave

to file a supplemental complaint (R.21-23) was granted

(R.20-21). The original plaintiffs thereupon filed a sup

plemental complaint. Of this action petitioners had no

prior notice and announced that they could not go to trial

on the supplemental complaint (R.21-23 and 36). The

motion of Governor Paubus and the officers of the Guard

to dismiss the petition of the United States was denied

(R.18-19). The motion of Governor Faubus and the Guard

officers to dismiss the petition of the United States for

failure to convene a Three Judge Court was denied (R.

19-20).

Thereupon counsel for the respondents announced that

they elected to stand on their motions, and they asked

and obtained leave of the Court to participate no further

in the proceeding and to retire from the courtroom (R.

60-61). Thereupon the Court proceeded to trial on the

petitions of the United States and of the plaintiffs for

preliminary injunction (R.60 and 63). The Court granted

the petitions and thereupon issued a preliminary injunc-

11

tion (R.62-64) and made findings of fact and conclusions

of law dated September 20, 1957 (R.65-74).

The findings of fact and conclusions of law were

written under the style, “ John Aaron, et al, Plaintiffs v.

William G. Cooper, et al Defendants, Civil Action No.

3113” , and the opening paragraph reads: “ This cause

having been heard upon the separate applications of

plaintiffs and of the United States as amicus curiae, for

a preliminary injunction against defendants Orval E.

Faubus, Governor of the State of Arkansas, Major Gen

eral Sherman T. Clinger, Adjutant General of the State

of Arkansas, and Lt. Col. Marion E. Johnson, Unit Com

mander of the Arkansas National Guard, the Court makes

the following findings of fact and conclusions of law” (R.

65) (emphasis supplied).

The first 19 numbered paragraphs of the Court’s

findings of fact set forth chronologically the events and

the actions of the Court heretofore outlined in this state

ment and included almost verbatim the allegations of the

petition of the United States. Paragraph 20 recited that

an “ injunction is necessary in order to protect and pre

serve the judicial process of the Court, to maintain the

due and proper administration of justice, and to protect

the constitutional rights of the minor plaintiffs and other

eligible Negro students on whose behalf this suit is

brought” (R.72).

The preliminary injunction, under the same style as

the Finding of Facts and Conclusions of Law contains

this opening statement: “ This cause having been heard

upon separate applications of the United States, as

amicus curiae, and of the plaintiffs for a preliminary in

junction, and it appearing that . . . ” (R.63).

The Honorable Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit affirmed the actions of the United States

12

District Court from which this cause was appealed, and,

in brief, held (1) that the Affidavit of Prejudice was

not timely filed, further stating that it was “ unnecessary

to consider whether the Affidavit would have been suf

ficient to disqualify Judge Davies had it been filed in

time” ; (2) that the District Court had jurisdiction to

issue the Preliminary Injunction, without expressly pass

ing on the specific objections raised by these petitioners

to the procedure of the Trial Court.

It is our position that the Circuit Court of Appeals so

far sanctioned a departure "from the accepted and usual

course of judicial proceedings" as to call for an exercise of

this Court's power of supervision, and this position we shall

endeavor to sustain in amplifying the six reasons relied cn

for the issuance of the Writ.

REASONS RELIED ON

I

This District Court held that the affidavit was not

legally sufficient and was not timely filed under Sec. 144,

Title 28 U.S.C.A. The affidavit was timely filed for Sec

tion 144 requires that the affidavit be “ . . . timely and

. . . filed not less than ten days before the beginning of

the term at which the proceeding is to be heard, or good

cause shall he shown for failure to file it within such

time” (italics supplied).

The affidavit must be filed with reasonable prompt

ness after knowledge of disqualifying facts are known by

the affiant. Bommarito v. United States, 8 Cir., 61 F. 2d

355; Scott v. Beams, 10 Cir., 122 F. 2d 777. The purpose

of this requirement is to protect the government from

useless and costly delays and to prevent the disarrange

ment of the court’s trial calendar. Bishop v. United States,

8 Cir., 16 F. 2d 410; Craven v. United States, 1 Cir., 22 F.

2d 605, cert den 276 U.S. 627.

13

The affidavit of prejudice was filed by the appellants

on September 19, 1957, the day before the matter was

set for hearing upon the petition of the United States

for a preliminary injunction. The United States, as peti

tioner, in argument below, made much of the fact that

there had been a delay of nine days from the time the

appellants were served with notice that they had been made

parties defendant until they filed the affidavit with the

Court. The pertinent provision of the affidavit is as

follows (R .ll-1 2 ):

“ Affiant states that he did not file this affi

davit ten days before the beginning of the present

term of court for the reason that he had not at

that time been made respondent in this case, and

that he was not, in fact, made repondent herein

until September 10, 1957. On that date the United

States of America, by Herbert Brownell, Jr., At

torney General of the United States, pursuant to

an order herein of Judge Davies directing him so

to do, filed herein a petition praying that affiant

and others be made respondents and for an injunc

tion against them. This affidavit is made and filed

as soon as possible after affiant and others were

made respondents to this litigation, and as soon

as the facts of the bias and prejudice of Judge

Davies became known to him and it is not made for

purposes of delay or for any other purposes than

that stated herein, and further the same is filed

as soon, according to affiant’s information and

belief, as the same could be considered by the Judge

of this Court. The affidavit is accompanied by a

certificate of counsel of record that said affidavit

and application are made in good faith.”

Quite obviously, it was impossible for petitioners to

file the affidavit of prejudice within ten days before the

beginning of the term of court as provided by the statute.

They had not been made parties in the case at that time

and, of course, had no way of knowing that they would

14

be parties defendant. They were made parties defendant

on September 10, 1957 (and were notified thereof on that

day). Between this date and the date set for hearing,

summons had to be served upon them, they had to retain

attorneys for proper presentation of their case, proceed

ings and orders of the Court had to be studied by the

Attorneys, and time was necessary to investigate the facts

and prepare the affidavit and brief in support thereof.

Under the order making petitioners parties, a sum

mons were issued directing them to answer the complaint

within twenty days as provided in Rule 12A of the Rules

of Civil Procedure. True, the Court had set the hearing

for prelimniary injunction on September 20 (R.9), but

they had twenty days, or until October 1, in which to

prepare and file their answer to the petition.

As pointed out to the Court at the hearing on the

petition for preliminary injunction, counsel for the re

spondents were not engaged as such until Monday, Sep

tember 16, 1957, before the hearing which had previously

been by the Court set for Friday, September 20, 1957

(R.33). Counsel did not then ask for a continuance, to

which surely they would have been entitled since the

time for answering had not expired, but with all possible

dispatch prepared the necessary affidavit and brief in

support thereof, filing the same with the Clerk of the

Court on Thursday, September 19, 1957. It cannot be

seriously argued that counsel for appellants were not dili

gent in preparing and presenting the affidavit on the

ninth day after the Court’s order was entered and on

the fourth day after they became associated with the case,

and eleven days before their time for answering the peti

tion would expire. Certainly it cannot seriously be argued

that this affidavit was not “ . . . made and filed as soon

as possible after affiant and others were made respondents

to this litigation . . . ” (R.12).

15

Petitioners also stated in the affidavit that “ . . . and

further the same is filed as soon, according to affiant’s

information and belief, as the same could be considered

by the judge of this Court . . (R.12). It was well

known that at that time the trial judge, the Honorable

Ronald N. Davies, was not in the City of Little Rock, and

had not been for several days prior thereto having spent

several days visiting at his home in Fargo, North Dakota,

Indeed, in the argument upon the affidavit and the mo

tion to strike, counsel for appellants pointed out to the

Court that the matter was being presented to the Court

at the earliest practicable moment it could be done con

sonant with the duties and busy routine of the Court

(R.34). Also, it may be interesting to note that one

of the attorneys for the original plaintiffs stated at the

hearing held on Friday, September 20, 1957, that he had

filed a motion for leave to file a supplemental complaint

(the record reflects that the said motion was filed Sep

tember 11, 1957) (R.78). . . Because of the fact that

his Honor has been out of town, we have not been able

to present this motion before today . . . ” (R.35). Even if

the affidavit had been filed on September 11, 1957, the

Court could not have considered it before the date it was

considered—that is, September 20, 1957.

In Bishop v. United States, 8 Cir., 16 F. 2d 410, 411,

the Court stated:

“ It is the intent of the statute that the affidavit

must be filed in time to protect the government

from useless costs, and protect the court in the

dissarrangement of its calendar, and prevent use

less delay of trials. . . . ”

Since, as shown, the Court could not have considered

the affidavit prior to the time it was presented on Sep

tember 20, there is absolutely no ground upon which to

argue that either the Government or the other appellees

16

herein would have incurred useless costs, disarrangement

of the Court’s calendar, or useless delay of trial.

It should be noted that neither the Court nor the

United States contended that they were taken by surprise

at the filing of the affidavit. At the hearing on the

day following the filing of the affidavit, the United States

filed a motion to strike it, outlining in detail the reasons

why it was alleged that the affidavit should be stricken

and also filed a brief in support of the motion (R.15-16).

The cases which have upheld the trial courts in strik

ing affidavits of prejudice on the grounds that they were

not timely filed have been based on the finding that

the affidavit was being used merely as an instrument

of delay. In this case, the appellants filed the affidavit,

not for the purpose of delay, but because meritorious rea

sons existed for disqualification. It should be noted that

the appellants have never moved for continuance. I f the

appellants had been seeking a delay, certainly they would

have been justified in asking for the delay on the grounds

that they had not had an opportunity to prepare for the

hearing, since they had only nine days to prepare for the

preliminary hearing under the Court’s order, and eleven

additional days in which to file their answer to the

petition.

As stated in Bishop v. United States, 8 Cir., 16 F. 2d

410 . . a defendant should not be compelled to try his

case before a judge who has expressed prejudice against

him . . nor should a technicality be permitted, on

the facts reflected in this case, to support a ruling that

the affidavit of bias or prejudice was not timely filed.

In Bishop v. United States, 8 Cir., 16 F. 2d 410, and other

cases cited, the record reflected that the disqualifying

facts were known long prior to the trial date and the in

tent of afifants was clearly to obtain a continuance of

17

the trial. None of the parties to this litigation have

argued, nor has the Court found, that any hardship would

have been inflicted upon any party if the judge had dis

qualified himself. It can only be assumed that the Court,

in holding that the affidavit was not timely filed, was

seeking to find a technicality whereby it could strike the

affidavit. This is in effect the Court saying—“ even

though I am prejudiced, I will hear the case because of

this technicality” .

II

The affidavit of prejudice filed by Governor Faubus,

in the District Court is copied in full in the record (R .ll) .

It sets forth in specific detail the times and places, where

known to appellant, the occurrence of the facts and rea

sons giving appellant the belief that the trial judge had

a personal bias against appellant. Briefly, these are that:

1. On at least four occasions made known to the

appellant, the trial judge conferred privately with mem

bers of counsel for petitioner, the United States (R.12),

2. On September 7, the United States District At

torney was reported to be making interim reports daily

to Judge Davies which reports had not been made public

and which purportedly contained statements, informa

tion and opinions concerning the merits of this litigation

prior to the time the United States became a party to

the litigation (R.12).

3. On a date unknown to the appellant, the Federal

Bureau of Investigation presented a report to the Court

which appellant believed contained purported facts and

conclusions indicating that appellant had acted without

just cause and in bad faith and that on the basis of said

report, the appellant in good faith believed the judge had

formed a personal bias against him and prejudged the

18

merits of any defense he might have in the litigation (R.

13).

4. As an indication of the personal bias of the judge

against appellants, in ruling on matters before the Court,

he relied on and incorporated in his rulings extra judicial

statements of the Chief Executive of Little Rock, who had

not at that time appeared as a witness, was not under

oath and no opportunity given the defendant to deter

mine the truth or falsity of the matters stated (R.13).

5. The trial judge ordered the Attorney General on

behalf of the United States to enter the case and petition

for injunctive relief against the appellants based upon

information and facts given him by persons not parties

to the litigation and therefore departed from the role of

impartial arbiter of judicial questions presented to him in

a civil case and assumed the role of advocate favoring

parties adverse to the appellants (R.14).

One of the fundamental rights of a litigant under

our judicial system is that he is entitled to a fair trial in

a fair tribunal, and that fairness requires the total ab

sence of any actual bias or prejudice in the trial of the

case. In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 136, 99 L ed 942.

When a personal, as distinguished from a judicial, bias or

prejudice exists in the mind of a trial judge, the principle

of fairness and impartiality is violated and any judgment

rendered must be reversed. Berger v. United States, 255

U.S. 22, 65 L ed 481; Craven v. United States, 1 Cir., 22

F. 2d 605, cert den 276 U.S. 627, 72 L ed 739. In passing

upon this point in the Berger case it was said (p. 35):

“ We are of opinion, therefore, that an affi

davit upon information and belief satisfied the sec

tion, and that, upon its filing, if it show the ob

jectionable inclination or disposition of the judge,

which we have said is an essential condition, it is

his duty to ‘ proceed no further’ in the case, And in

19

this there is no serious detriment to the adminis

tration of justice, nor inconvenience worthy of men

tion; for of what concern is it to a judge to pre

side in a particular case? of what concern to other

parties to have him so preside? and any serious

delay of trial is avoided by the requirement that

the affidavit must be filed not less than ten days

before the commencement of the term. . . . ”

Thus, the Berger case has settled the question as to

the duties the judge before whom such an affidavit is

filed may exercise in determining the sufficiency thereof.

The truth of the matters stated in the affidavit must at the

outset be admitted as the judge is denied the discretion

of determining the truth or falsity of it. The office

of the judge is to determine merely whether the reasons

and facts stated in the affidavit are such that, assuming

them to be true, they comply with the statute.

Upon the filing of the required statutory affidavit

incorporating facts and reasons sufficient to form the be

lief that bias or prejudice exists in the mind of the trial

judge, it is the duty of the judge to immediately dis

qualify himself from further participation in the case and

proceed no further. Lewis v. United States, 8 Cir., 14

F. 2d 369; Nations v. United States, 8 Cir., 14 F. 2d 507,

cert den 273 U.S. 735, 71 L ed 866. Moreover, it is suf

ficient that the allegations contained in the affidavit be

predicated upon information and belief. Berger v. United

States, 255 U.S. 22, 65 L ed 481; Tucker v. Kerner, 7 Cir.,

186 F. 2d 79, 23 A.L.R. 2d 1027. It is well settled also

that a judge whom it is sought to disqualify is presented

solely with a question of law and must treat the matters

alleged in the affidavit of prejudice as true. Berger v.

United States, 255 U.S. 22, 65 L ed 481; Korer v. Hoff

man, 7 Cir., 212 F. 2d 217; Scott v. Beams, 10 Cir., 122

F. 2d 777; and it was not within the province of the trial

judge to pass upon the good faith of the affiant, the af-

20

fidavit being sufficient in form and accompanied by the

required certificate of counsel as to good faith. Morris

v. United States, 8 Cir., 26 F. 2d 444.

The Court has considered the predecessor of the fore

going statute which was then substantially its present

form. In Berger, et al v. United States, 255 U.S. 22, 41

S. Ct. 230, 65 L ed 481, petitioners had filed with the

district court an affidavit pursuant to the above statute

requesting removal of the presiding judge and the assign

ment of another to conduct the trial. Reasons given in

their affidavit were that Judge Landis had made certain

derogatory statements concerning the nativity of the de

fendant petitioners. The question presented was whether

the filing of the affidavit automatically compelled re

tirement of the judge from the case or whether he could

properly exercise a judgment upon the facts set forth

in the affidavit requesting his removal.

The holding in the Berger case makes it clear that

the belief of a party lodging such an affidavit is of primary

concern in determining the issue. It is pointed out that

unless he receives information from others he would nor

mally never know whether a bias or prejudice unfavorable

to him exists in the mind of a trial judge hearing his case.

The United States, as petitioner, argued in the Court

below that bias and prejudice of the trial judge was not

shown merely by his having conferred about the case with

the United States’ Attorney or other representatives of

the Department of Justice without the presence of ap

pellants or their counsel. This argument ignores the

true purpose and intent for which the statute was en

acted. Governor Faubus pointed out and alleged in the

affidavit as clearly as was possible the facts complained

of, giving specific dates on which they were reported

publicly. In Berger v. Untied States, at page 35 it is

stated:

21

“ We may concede that Sec. 21 is not fulfilled

by the assertion of ‘ rumors or gossip’, but such

disparagement cannot be applied to the affidavit

in this case. Its statement has definite time and

place and character, and the value of averments on

information and belief in the procedure of the law

is recognized. To refuse their application to Sec.

21 would be arbitrary and make its remedy unavail

able in many, if not in most, cases. . . . ”

In criminal cases, it might logically be argued that

in proper circumstances the trial judge might be justified

in conferring with counsel for the Justice Department in

serving the ends of justice. However, this is a civil case

and the role of the trial judge as impartial arbiter is

more restricted. As stated by the Court in Knapp v. Kin

sey, et al, 6 Cir., 232 F. 2d 458, 466, cert den 352 U.S. 892:

“ The judge should exercise self-restraint and

preserve an atmosphere of impartiality. When

the remarks of the judge during the course of a

trial, or his manner of handling the trial, clearly

indicate a hostility to one of the parties, or an un

warranted prejudgment of the merits of the case,

or an alignment on the part of the Court with one

of the parties for the purpose of furthering or

supporting the contentions of such party, the judge

indicates, whether consciously or not, a personal

bias and prejudice which renders invalid any re

sulting judgment in favor of the party so favored.”

In the Berger case it is said:

“ . . . the tribunals of the country shall not

only be impartial in the controversies submitted to

them, but shall give assurance that they are im

partial,;—free, to use the words of the section, from

any ‘ bias or prejudice’ that might disturb the normal

course of impartial judgment. . . . ”

The affidavit alleged that the trial judge, at a time

unknown to the appellants, conferred privately with the

22

favored litigants, the plaintifs and the United States, as

petitioner, and that on a date unknown to the appellants,

received a purported report from the Federal Bureau of

Investigation made available to the United States’ At

torney, but not to appellants; and that the report con

tained purported facts and conclusions of a nature to

create an ill and unfriendly feeling in the mind of the

judge against petitioners.

This report, as previously pointed out, was presented

to and received by the trial judge at a time prior to the

United States becoming a party to the litigation. It was

made by persons who were not witnesses and who were

never at anytime available for cross examination by the

appellants, as to the truth or falsity of any matters or

conclusions included therein. Certainly it cannot be said

that this conduct on the part of the trial judge in con

junction with parties adverse to the appellants is not suf

ficient to raise a strong belief in the minds of reasonable

men that a personal bias existed in the mind of the

trial judge hearing the cause.

Ill

The petition of the United States should have been

dismissed on the ground that the United States was not

the real party in interest. The action was one for the

protection of purely private rights. It is true that these

rights arise under the Constitution of the United States,

but the United States had no real interest in the action.

Volume 43 C.J.S., Injunctions, Section 35:

“ In order to be entitled to an injunction com

plainant must be the real party in interest.”

The United States cannot justify its intervention in

this action on the ground that its assistance was needed

to uphold the authority of the Court. If the appellants

23

had violated any orders of the Court there was a plain

and adequate remedy by way of contempt. Presumably,

the United States was of the opinion that the appellants

had violated orders of the Court. Therefore, it sought

and obtained a direct order against the respondents. We

submit that the United States, not being a real party

at interest, was not entitled to seek the relief prayed in

the petition, which was for the sole benefit of the parties

plaintiff in the Aaron v. Cooper case.

IV

In the Court’s order dated September 9, 1957, the

Court directed that pursuant to Pule 15 (d) and Rule

21, F.R.C.P., the respondents be made parties defendant

in this cause. The petition recited in the first paragraph

that it was being filed pursuant to and in conformity with

the purpose and intent of the court’s said Order (R.6-9).

Petition was not filed in compliance with or in con

formity to the provisions of Rule 15 (d).

The provisions of this rule were not complied with.

No party to this suit appeared before the Court and no

notice was given as required by the rule.

Subdivision (d) of Rule 15 is headed “ Supplemental

Pleadings’ ’ . The Courts have frequently had occasion to

determine what pleadings are qualified to be filed there

under. District Judge Hulen, in the case of General

Gronze Corporation, et al v. Guppies Products Corpora

tion, et al, 9 F.R.D. 269, pointed out that the plaintiffs

sought permission to file a supplemental complaint under

Rule 15 (d) by which infringement of a patent, granted

subsequent to filing the original complaint, was charged,

and that the defendants resisted the move claiming the

supplemental complaint would introduce a new and inde

pendent cause of action. Since it was apparent that the

24

so-called supplemental complaint would introduce a new

and independent cause of action, he devoted the remainder

of the opinion to a discussion of the applicability of the

rule.

It is too plain for argument that Rule 15 (d) is de

signed only to permit a party to seek permission to file

a supplemental pleading. District Judge Hulen cited in

further support of his ruling the case of Fierstein v. Piper

Aircraft Corporation, D. C., 79 F. Supp. 217. See also

Ebel x. Drum, D. C. Mass., 1944, 55 F. Supp. 186; and

Magee v. McNancy, D. C. Pa., 1950, 10 F.R.D. 5.

In the court’s said order of September 9, in com

pliance with which this petition was filed, it was stated

that the order was made also pursuant to Rule 21, F.R.C.P.

It is obvious, as was stated in the case of Truncate v.

Universal Pictures Company, D. C. N. Y., 1949, 82 F. Supp.

576, that this rule is intended to permit the bringing

in of a person or persons who, through inadvertence, mis

take or some other reason, had not been made a party and

whose presence as a party was necessary or desirable to

effectuate the relief prayed for in the original action.

The original action in this case was on the part of

John Aaron and others, plaintiffs, seeking to enter cer

tain schools in Little Rock, against William G. Cooper and

others, school directors. It is inconceivable that a con

tention can be made, or will be made, that the respondents

in this case were necessary parties to that action. Rule

21 could not possibly apply to them and does not afford

any support for the action of the Court in ordering them

to be made parties. It is true that Rule 21 provides that

misjoinder of parties is not ground for dismissal of

an action but here the United States was not such a

party to the action as would be entitled to affirmative

25

relief and it could not become such a party. It is well

settled that the United States can become a party litigant

only where there is a Federal statute expressly authoriz

ing it to do so, and respondents submit there is not in

existence any statute authorizing the United States to

become a party in an action or proceeding such as this

one. Indeed the Congress has quite recently expressly

refused to sanction the presence of the United States as

a party litigant in cases of this particular nature.

V

The original action herein was one for the protec

tion of private rights. Until September 10, 1957, it con

tinued to be an action between private litigants involving

purely private rights, i.e., the rights of the plaintiffs to

attend a particular school of their choice.

The order of the District Court dated September 9,

1957 (R.5-6), invited the Attorney General and the United

States Attorney to appear amici curiae and authorized

them as such to submit pleadings. The order then di

rected them to file a petition seeking an injunction against

the Governor of Arkansas and two officers of the Ark

ansas National Guard. Petitioners say that the Court

was wholly without jurisdiction to make its order dated

September 9, 1957, and, further that the Court was with

out jurisdiction to entertain the petition of the United

States or to grant any relief thereon.

If the Attorney General and the United States At

torney were truly amici curiae, they had no right as

such to file petitions or otherwise to seek any affirmative

relief. It is axiomatic that amici curiae are not litigants,

but are merely advisers to the Court. The fact that the

Court authorized and directed the filing of the petition

can add nothing to their status as amici curiae. If they

26

were truly amici curiae, the Court had no jurisdiction by

order to give them the status of litigants.

In Birmingham Loan & Auction Co. v. First National

Bank, of Anniston, 100 Ala. 249, 13 So. 945, 946, the

Court said:

“ An amicus curiae, in practice, is one who, as a

stander-by, when a judge is doubtful or mistaken

in a matter of law, may inform the court. Bouv.

Diet. ‘ He is heard only by the leave and for the

assistance of the court, upon a case already before

it. He has no control over the suit, and no right

to institute proceedings thereon, or to bring the

case from one court to another by appeal or writ

of error.’ Martin v. Tapley, 119 Mass. 116; 1 Law-

son, Rights, Rem & Pr. p. 262, Sec. 156.”

In American Jurisprudence, Volume 2, page 679, the

following appears:

“ . . . an amicus curiae is heard only by leave

and for the assistance of the court upon a case

already before it. He has no control over the suit

and no right to institute any proceedings therein.

It seems clear that an amicus curiae cannot as

sume the function of a party in an action or pro

ceeding pending before the court, and that, ordi

narily, he cannot file a pleading in a cause. An

amicus curiae is restricted to suggestions relative

to matters apparent on the record or to matters

of practice. His principal function is to aid the

court on questions of law.”

On page 682 the following appears:

“ An amicus curiae has no right to except to

the rulings of the court; and if he takes such ex

ceptions, they cannot avail on appeal. He has no

right to complain if the court refuses to accept

his suggestions, for it is not the function of an

amicus curiae to take upon himself the management

27

of a cause and assume the functions of an attorney

at law.”

The petition filed by the United States was filed by

the United States solely as amicus curiae. It is clear

that the United States, as amicus cu-riae had no right

to ask for the joinder of additional parties and the entry of

an injunction against such parties, for, in so doing, the

United States became a litigant and not a “ friend of the

Court” . It is apparent from the order dated Septem

ber 9, 1957, and from the petition filed by the United

States that it was the intent of the Court and of the

United States that the United States become an actual

litigant in this controversy under the guise of amicus curiae.

The United States had no right to intervene in this action

as a litigant, and the Court had no jurisdiction to order

its intervention. The Court had no jurisdiction to en

tertain a petition by the United States seeking to aid

private litigants in the enforcement of private rights.

If the United States had no right to intervene, and

if the Court had no jurisdiction to consider the inter

vention, the Court’s order of September 9, did not create

jurisdiction to consider the petition, whether the United

States was considered a litigant or whether it was con

sidered a friend of the Court.

The District Courts of the United States have only

such jurisdiction as is expressly conferred on them by

the Congress. The Congress has expressly refused to

confer jurisdiction on such courts to entertain petitions

for injunction by the United States in Civil Rights actions.

The case of Universal Oil Products v. Root Refining

Company, 328 U.S. 575, is cited by the Circuit Court of

Appeals to support the action brought by the amici curiae.

In that case attorneys for one or more of the parties

were requested to serve in the role of amici curiae in an

28

investigation to ascertain whether fraud had been prac

ticed on the Court. They undertook this service and pro

cured the appointment of a Master, whose report that

fraud had been practiced resulted in the vacation of the

judgment that had been rendered in the case. It is seen

that there is no similarity in the part taken by amici

curiae in the Root Refining case and that taken by counsel

in this one. There amici curiae were acting in an ancillary

capacity as investigators of questionable features sur

rounding the conduct of a Judge. Here, amici curiae were

acting in the capacity of leading counsel in an effort to

secure substantial rights for the parties themselves. There

are no other interests involved than the rights of the

parties to the suit. This Court condemned such action

by saying, in the Root case, “ Amici selected by the Court

to vindicate its honor ordinarily ought not to he in the

service of those having private interests in the out

come” . While amici in this case were not employed by

the parties in the case, they were serving the parties who

had already employed their own counsel and were ably

represented in this, as well as other phases of the litigation.

V!

This question practically answers itself in the nega

tive. No notice was given petitioners of the filing of

the motion to permit the original plaintiffs to file a sup

plemental complaint. Yet, on September 20, 1957, they

were permitted to file it, and the District Court imme

diately proceeded to trial on the supplemental complaint

and the petition of the United States.

We have endeavored to show that the Court wTas

without jurisdiction to proceed to trial on the petition

of the United States against the petitioners. This lack

of jurisdiction stems from the incapacity of the petitioner

in its role of amicus curiae and its non-interest in the

29

subject manner of the civil litigation. Nevertheless, the

Court proceeded to trial on the Supplemental Complaint

and granted effective relief to the original plaintiffs and

against, the petitioners in the absence of notice of the

filing of the Supplemental Complaint or of the motion

for leave to file it.

CONCLUSION

Regardless of the heights of emotion and public in

terest or curiosity attained by this suit, and regardless

of the notoriety given the participants, there can surely

be no justification for disregarding statutes and rules of

procedure, the observance of which, we feel, would have

gone a long way towards ameliorating the great damage to

racial relations that has resulted from the precipitate

outcome of the case.

Petitioners respectfully ask this Court to grant the

Writ of Certiorari as prayed in the petition.

T homas H arper

Fort Smith, Arkansas

K ay L. M atthew s

Little Rock, Arkansas

W alter L. P ope

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Petitioners

Appendix A

U n i t e d S t a t e s Court o f Appeals

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 15,904

Orval E. Faubus, Governor of the

State of Arkansas, General Sher

man T. Clinger, Adjutant Gen

eral of the State of Arkansas,

and Lt. Col. Marion E. Johnson,

Unit Commander of the Arkan

sas National Guard, (Respond

ents) ______ ___ __- Appellants

v.

United States of America (Amicus

Curiae, Petitioner), and John

Aaron, a minor, and Thelma

Aaron, a minor, by their mother

and next friend, (Mrs.) Thelma

Aaron, a feme sole, et al (Plain

tiffs), and William G. Cooper,

M.D., as President of Board of

Trustees, Little Rock Independ

ent School District, et al (De

fendants) ___________ Appellees

A p p e a l from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

Arkansas.

[April 28, 1958]

2a

Kay L. Matthews and Thomas Harper (Walter L. Pope

was with them on the brief) for Appellants.

Donald B. MacGuineas, Attorney, Department of Justice,

(George Cochran Doub, Assistant Attorney General,

Osro Cobb, United States Attorney, and Samuel D.

Slade, Attorney, Department of Justice, were with

him on the brief) for Appellee United States of Amer

ica, Amicus Curiae.

Thurgood Marshall (Wiley A. Branton was with him on

the brief) for Appellees John Aaron, et al.

Hansel Proffitt filed Brief Amicus Curiae.

Before S anborn , W oodrough and J ohn son , Circuit Judges.

S anborn , Circuit Judge.

This is an appeal from an order of the District Court

made September 20, 1957 (filed September 21, 1957), in

the action of John Aaron, et al, Plaintiffs v. William, G.

Cooper, et al, Defendants (143 F. Supp. 855), to which

the appellants on September 10, 1957, had been made addi

tional parties defendant. The order enjoined the appel

lants, and others under their control or in privity with

them, from using the Arkansas National Guard to prevent

eligible Negro children from attending the Little Rock

Central High School, and otherwise obstructing or inter

fering with the constitutional right of such children to

attend the school. The order expressly preserved to

Governor Faubus the right to use the Arkansas National

Guard for the preservation of law and order by means

which did not hinder or interfere with the constitutional

rights of the eligible Negro students.

3a

The appellants assert that the order appealed from must

be reversed because the District Judge erred in rejecting

an affidavit of prejudice and in refusing to disqualify him

self. They assert also that the Court erred: (1) in over

ruling the motion of the appellants to dismiss the peti

tion of the United States asking that the. appellants be

made additional defendants in the Aaron ease and be

enjoined from using the Arkansas National Guard to pre

vent eligible Negro students from attending the Little

Rock Central High School; (2) in overruling appellants’

motion to dismiss the petition for failure to convene a

three-judge court; and (3) in entering the preliminary

injunction.

A statement of the events and proceedings which con

stitute the background of this controversy seems neces

sary to a full understanding of the questions presented

and to show how they arose.

The Supreme Court of the United States on May 27,

1954, decided in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

347 U.S. 483, that segregation of white and Negro chil

dren in the public schools of a State solely on the basis

of race, under state laws permitting or requiring such

segregation, denied to Negro children the equal protec

tion of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States, even though the

physical facilities and other tangible factors of white and

Negro schools were equal. The case was restored to the

Supreme Court’s docket to await the formulation of de

crees and for further argument on questions not then de

cided.

On May 31, 1955, in 349 U.S. 294, the Supreme Court

announced its supplemental opinion and final judgments

in the Brotvn case. We quote some of the pertinent ex

cerpts from the opinion (pages 288, 299, 300):

4a

“ These cases were decided on May 17, 1954.

The opinions of that date, declaring the funda

mental principle that racial discrimination in public

education is unconstitutional, are incorporated here

in by reference. All provisions of federal, state,

or local law requiring or permitting such discrim

ination must yield to this principle. * # *

* # # # # * #

“ Full implementation of these constitutional

principles may require solution of varied local

school problems. School authorities have the primary

responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving

these problems; courts will have to consider whether

the action of school authorities constitutes good faith

implementation of the governing constitutional prin

ciples. * * *

“ * * * At stake is the personal interest of the

plaintiffs in admission to public schools as soon as

practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis. To effectu

ate this interest may call for elimination of a variety

of obstacles in making the transition to school sys

tems operated in accordance with the constitutional

principles set forth in our May 17, 1954, decision.

Courts of equity may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles in

a systematic and effective manner. But it should go

without saying that the vitality of these constitu

tional principles cannot be allowed to yield simply

because of disagreement with them.

“ While giving weight to these public and pri

vate considerations, the courts will require that the

defendants make a prompt and reasonable start

toward full compliance with our May 17, 1954, rul

ing. Once such a start has been made, the courts

may find that additional time is necessary to carry

out the ruling in an effective manner. The burden

rests upon the defendants to establish that such

time is necessary in the public interest and is con

sistent with good faith compliance at the earliest

practicable date.”

5a

On May 23, 1955, the School Board of the Little Rock

School District had adopted and published a statement to

the effect that it was the Board’s “ responsibility to com

ply with Federal Constitutional Requirements” and that

it- “ intended to do so when the Supreme Court of the

United States outlines the method to be followed,” and

that in the meantime the Board would make the needed

studies “ for the implementation of a sound school pro

gram on an integrated basis.” Pages 858-859 of 143 F.

Supp.

The Superintendent of the Little Rock schools, upon

instructions from the School Board, prepared a plan for

the gradual integration over a period of about seven

years of the public school in Little Rock, commencing at

the senior high school level in the fall of 1957. The plan

was adopted by the Board on May 24, 1955, and is fully

set forth in the opinion of the District Court in Aaron v.

Cooper, supra, 143 F. Supp., at pages 859-860, and need

not be restated in this opinion.

On February 8, 1956, John Aaron and other minor

Negroes of school age brought a class action in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas

against the members of the Little Rock School Board, for

the purpose of bringing about the immediate integration

of the races in the public schools of Little Rock. The

School Board answered the complaint and submitted to

the court its plan for integration which it asserted would

best serve the interests of both races (page 858 of 143 F.

Supp.). It alleged that a hasty integi*ation would be un

wise and would retard the accomplishment of the integra

tion of the Little Rock schools. United States District

Judge John E. Miller, who heard the case, filed a compre

hensive opinion on August 27, 1956 (143 F. Supp. 855),

in which it was determined that the defendants, the school

authorities, had acted in the utmost good faith and with

6a

the sole objective “ to faithfully and effectively inaugurate

a school system in accordance with the law as declared by

the Supreme Court.” The District Court ordered that

the plan of the defendants be approved as adequate;

denied the plaintiffs any declaratory or injunctive relief;

and retained jurisdiction of the case for the entry of such

other and further orders as might be necessary for the

effectuation of the approved plan. (Page 866 of 14.3 F.

Supp.)

The plaintiffs appealed. They urged in this Court, as

they had in the District Court, that there were no valid

reasons why integration in the public schools of Little

Rock should not be completely accomplished by September,

1957. On appeal this Court held, on April 26, 1957, that

“ in the light of existing circumstances the plan set forth

by the Little Rock School Board and approved by the

District Court is in present compliance with the law.”

Aaron v. Cooper, 8 Cir., 243 F. 2d 361, 364. The judgment

of the District Court was affirmed, with its retention of

continued jurisdiction.

On September 2,1957, the appellants, Orval E. Faubus,

Governor of the State of Arkansas, and Sherman T.

Clinger, Adjutant General of the State, stationed units of

the Arkansas National Guard, under the command of Lt.

Col. Marion E. Johnson, at the Little Rock Central High

School. The order of Governor Faubus to General

Clinger was as follows:

“ You are directed to place off limits to white

students those schools for colored students and to

place o ff limits to colored students those schools

heretofore operated and recently set up for white

students. This order will remain in effect until

the demobilization of the Guard or until further

orders.”

As a result of this order, nine Negro school children

who, under the School Board’s approved plan of integra

tion, had been found eligible to attend the high school,

were not, by request of the school authorities,, in attend

ance on September 3, 1957, the opening day of the fall

term.

The court, by United States District Judge Ronald N.

Davies, sitting by assignment, on September 3, 1957, is

sued an order directing the members of the School Board

and the Superintendent of the Little Rock Public Schools,

the defendants in Aaron v. Cooper, to show cause why the

court, under its reservation of jurisdiction in that case,

should not order them to put into effect forthwith the plan

of integration approved by the District Court and by the

United States Court of Appeals. On the same day, after

a hearing on the order to show cause, the court found that,

because of the stationing of military guards at the Central

High School by state authorities, the defendants (mem

bers of the School Board) had reversed the position taken

by them in their plan for integration and had requested

the eligible Negro students to stay away from the school

“ until the legal dilemma was solved.” The court also

found that the evidence presented disclosed no reason

why the plan of integration approved by the court could

not be carried out forthwith. The defendants (members

of the School Board and the Superintendent of Schools)

were ordered to carry out the plan.

Judge Davies on September 4, 1957, wrote the follow

ing letter to the United States Attorney for the Eastern

District of Arkansas:

“ Mr. Osro Cobb

United States Attorney

Little Rock, Arkansas

“ My dear Mr. Cobb:

“ I am advised this morning that this Court’s

order directing the integration of the Little Rock

schools under a plan submitted by the Little Rock

School Board, which plan has been approved by a

Judge of this court and by the United States Court

of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, has not been com

plied with due to alleged interference with the

Court’s order.

“ You are requested to begin at once a full,

thorough and complete investigation to determine

the responsibility for interference with said order,

or responsibility for failure of compliance with

said order of this Court heretofore made and filed,

and to report your findings to me with the least

practicable delay.

Very truly yours,

R onald N. D avies

United States District Judge

(Sitting by Assignment)

On September 7, the court denied a “ petition of the

Little Rock School District directors and of the Super

intendent of the Little Rock Public Schools for an order

temporarily suspending enforcement of its plan of integra

tion heretofore approved by this Court.”

On September 9, the court entered the following

order:

9a

“ In The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Arkansas

Western Division

“ John Aaron, et al, Plaintiffs,

v. No. 3113 Civil.

“ William Gr. Cooper, et al, Defendants.

‘ ‘ On the date hereof, the Court having received

a report from the United States Attorneys for the

Eastern District of Arkansas, made pursuant to the

Court’s request, from which it appears that negro

students are not being permitted to attend Little

Rock Central High School in accordance with the

plan of integration of the Little Rock School Di

rectors approved by this Court and by the Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

“ And the Court being of the opinion that the

public interest in the administration of justice should

be represented in these proceedings and that it will

be of assistance to the Court to have the benefit of

the views of counsel for the United States as amici

curiae, and this Court being entitled at any time

to call upon the law officers of the United States

to serve in that eapacitly, now, therefore,

“ It is ordered that the Attorney General of the

United States or his designate, and the United

States Attorney for the Eastern District of Ark

ansas or his designate, are hereby requested and

authorized to appear in these proceedings as amici

curiae and to accord the Court the benefit of their

views and recommendations with the right to sub

mit to the Court pleadings, evidence, arguments and

briefs, and for the further purpose, under the di

rection of this Court, to initiate such further pro

ceedings as may be appropriate.

“ It is further ordered that the Attorney Gen

eral of the United States and the United States

Attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas be

10a

and they are hereby directed to file immediately a

petition against Orval E. Faubus, Governor of the

State of Arkansas; Major General Sherman T.

C 1 i n g e r , Adjutant General, Arkansas National

Guard; and Lt. Colonel Marion E. Johnson, Unit

Commander, Arkansas National Guard, seeking such

injunctive and other relief as may be appropriate

to prevent the existing interferences with and ob

structions to the carrying out of the orders hereto

fore entered by this court in this case.

“ Dated at Little Rock, Arkansas, this 9th day

of September, 1957.

R onald N. D avies

United States District Judge

(Sitting by Assignment)”

On September 10, the United States, by its Attorney

General and the United States Attorney for the Eastern

District of Arkansas, filed a petition pursuant to the

court’s order, stating that units of the Arkansas National

Guard were still forcibly preventing and restraining

Negro students, eligible under the approved plan of school

integration, from entering school and attending classes;

that the acts of the appellants, through the use of the

Arkansas National Guard, were obstructing and interfer

ing with the effectuation of the court’s orders of August

28, 1956, and September 3, 1957, “ contrary to the due

and proper administration of justice.” The United States

asked that the appellants be made additional parties de

fendant in the Aaron case and be enjoined, together with

those under their control or in privity with them, from

using the National Guard to prevent the eligible Negro

students from attending the Little Rock High School, and

otherwise obstructing or interfering with the effectuation

of the court’s orders in that regard.

The court on September 10, 1957, added the appellants

as defendants in the Aaron case, and set the Government’s

11a

petition for a preliminary injunction for hearing on Sep

tember 20, 1957.

On September 19, 1957, the day before the hearing,

Governor Faubus filed an affidavit of prejudice against

Judge Davies, stating that he was informed and believed

Judge Davies had a personal prejudice against him and a

personal bias in favor of the plaintiffs John Aaron et al.

and the United States. The reasons for the Governor’s

belief were stated at length in this affidavit.

The United States on September 20, 1957, the day of

the hearing, moved the court to strike the affidavit of prej

udice as untimely and legally insufficient.