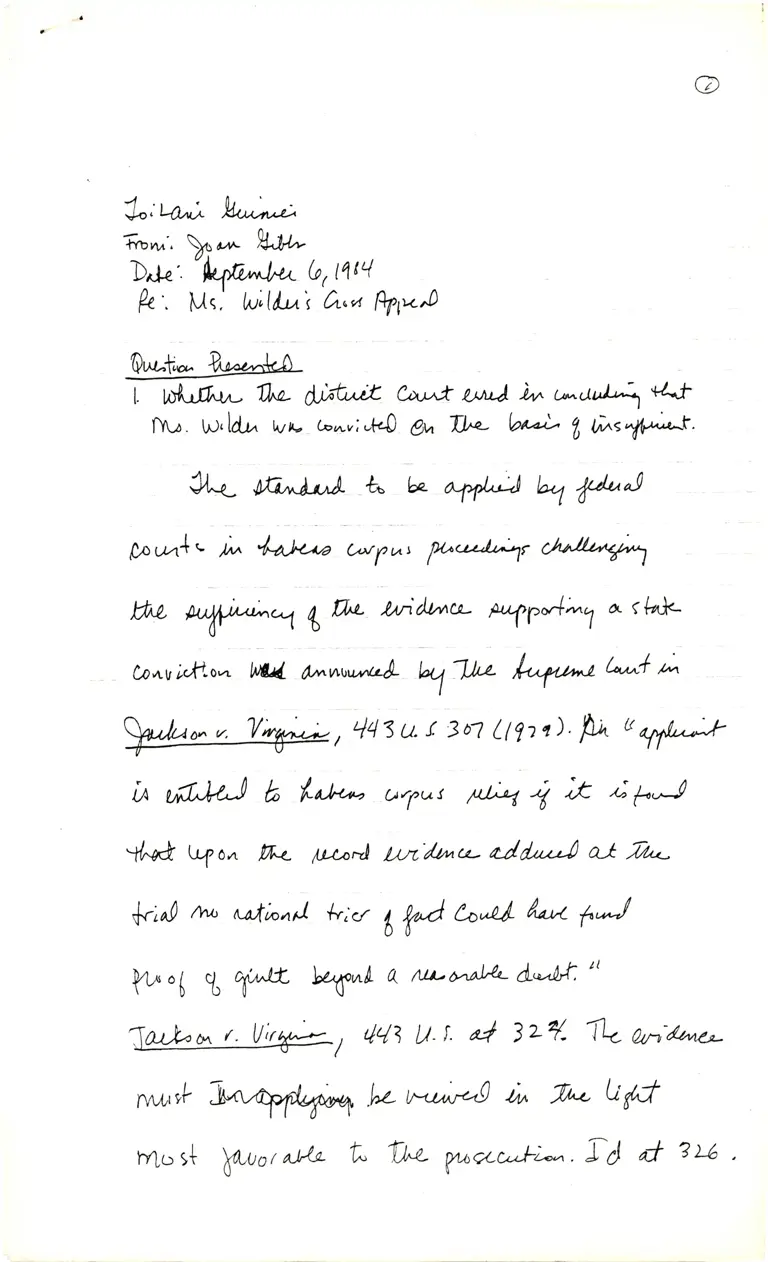

Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier

Working File

September 6, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier, 1984. a13d0e4f-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cce136be-b678-43e4-98a0-8100da066764/memorandum-from-gibbs-to-guinier. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

@

L,t-a; k,M^

Tmrv', V r,^ YlJf*

D^P ' 'l*4tt ^,'lru b, f4t4

k . Ms,' lp'llr^'t Cuq fttrf.O

Q,rut,", Wr^rr^k a

t td\rjful-, fl,@ dJhtilL Or,, -t urll )^ u*,4q a-t

lYu. W,[d]" Wa Lowvi't 0 Ou T)/L be-;- ?, tr,^s^5i.,-,*-t.

3l^{ Lfr,*ALA t" &

^fpL-,! 4 {iuJ

W *fW'^ZLil^L tiolnco' Pff'd;1 a<W

Co*u Lc,?"0,n Wel 0.,.,.wr',t rt J- A4 T/2 1.4r"* (."r^4 P,

I

& / 44s u. r 301 (lgl r) PA a 4ffL**

iA b{,"kJ h /'^l** L,trTut /1,4 4 k i hJ

I/"r^* W o^ fr,.e- 1lunl t/.r{/tntz- L/dr.,rrJ a/ .T/tr-

k',o! /Yv, wtirnrl .(";v

6 W 6,,4 4rr/ t",,-/

\/1J'

66 % W buyt ct, /1tt-6^il/L d,,l,t lt

, 441 U- f . al 3 L(- 7* o.on-tu,alr-

-W brutd.9 b Ih* U{"t'fYwrsl

h4t, f{ Wror a&-a- t" [l^L yua-a,tL^ T() d ? L6 .

?. Ly'a.a,

tL/

tL Brut+L

Dg^car^ \t. 9l7nyLu"^L-t 764 € U

(^ Lt,B ),' t*Lt^u.: a*,t t/. [lc4/nq , 6S z

b(c, (ru c), /tr)

lo.zL I bt e. cf, )a t q,6? /. il. zl

I u 60r.

4s t L(. r.

s1 s Qqn),

c-orr+{ rwrrt-s I

dd0"^\^4- 9,s

( ffi*- (/,-b ry M w'J rw.t

/1/.,t^ 1'< lm L4" 4 0,r.!-'' L;c\ , &rfil^yL in u

<1* u,,i ;"

Wat4^L$1 fre Aa.)o,,-, Mt+k

#t t l-{.An;* s1,r1<- LC^, t'

/.Ai^"a/'Jr t W Ct*b, D,r-nr-- u

1uf € 2J t>t? i tz tt/( tl'tt (;. ltu ?b

du{<*uvJt b.,l lrJ'l,rGl"r* 44- < GJr'tz{,-t-t

I

4arh,wl

-Aolxr* curp* 4,*+ P wL{L a'-

/wu{d \hlnc,,Q. WrU"} s.^1P,s.{,

Wu-,v.q_Vx_.\

aflW iJ{-'4 dr,4 n^*

%y,^

,bu,*r\- W #. (; (,t-d b-eoL6-l

y Pttrh G"W ir^ Yuo' ^Tl^'

4w,"*L^,

V rr c/rr^r- .,

%. 1., 14-k /'taolJl*. " Sul'r*^ '-

413A.c. d 34,

;* .yrv*Sl bL ?.ov4r^ 't4*k IL.

ft\( . l,O,U,u- fuo-, Cqu:r*A -{V;t^*;,

g n- ?fuil rt y* Lk g h-;dd^^^^ Pt 15 / ,JJ

W;b i put^.-+ f*l

t

htLa Pu' \ tt nt t,u$"o v o k t rwl $,1Q t(,t^

or fupur,ll, ,rrr,- T^a,A oAa- b4!/5+

lnr fu0- sa,** W o-, -4; u*-

'A,* Ur^ l).-o-<f*qt or la',,-'*.fu

q{<,^fb h vo&'ur)*-' 4'- ; A.+

!*',14il + bo^so1 rLffi,\w1

k ,A I ,utl.r*Q or ]^at,it,Ja*T

**T\, *tf

6.' %wrlt!L^' L'<-

y."WL-"^'J h -Ki- P^tL4+;"1 \o'

U-- 4(* 1,^/t )tutt .atLo,-.- fu^ b

W, d,, fr* dLo'rj)-oc,- 7 la

Y1 '

{nr e Ot^rr}tnn t b. obhu*',-^9 urr,4a

g t1- 0.J-l

z

frrLLLUr'-g o^,"fu@ fa*r) { /o# ttttult- (/'-*''

G

AnU. W:uLs,,^ v. e{il* /€ 2 +h, )4q/ ?o Z

L tt 1t ) ', l/rl fu^ /. g 1*1c, ct6 I gu u

/

/

/sl , LLc> (frlo h;- ftfr,.) , o*t

t ' 'l-

4bt fo ,d lbs aru, (%r), ul / -i ,

L drrfu* cr#t h16*;;, s,uq^*tt4

C^rUdr^L Ar) X

ff,*

&rJ

I"/.6-"/ h Vo, qu |\ns-

Wfu*Q*z--

fr,@ at*oun* q t^Jo^r--

,+1"* hutt^+- tplt-' Cr-e

lh [^,* rvW'vvto- q^ Wt* (rt" fu"'rr-/

ffimwYLwbff*

prd*l wp rgwrwau-t I4N;-A^L./

b,"..{.o1.' l,tu* + fuL iw).n(

hYLuq Vok-.hx&- ?*'yfl\LtgJ,rb, rr pl,* l"*l 'a;* h )Mr*1

a frl'L b4,*<, 0^,-,1 aL u-h L V=-t

hrrq +Lre i. u 'l'la; t Q^tl.^r t"

Vrr.' ,hA a^;-J.9 fr fi-tL4 co,^L-l

lWaDM^,Flz flil t-rfu^l'6

fu^a-a.',."+'d o\uJi U|* uil/t-

rr^ tl "1"* [i,Ll /^ (/^- buJkh

.l^!^?,).{ wl tu+ YLtuW^ lL ,^l+

0tl

w,y a)dlrwflry dtl Wb

$*,-^l*p h^i: +fu)w4 n"{ WTTnV

ffi Trnf fi"*fo W qt

a@vg fvww ry Vf,*fd u*,)nY W ffi

yy-drfi*a mr *p r-f V.*nil o

.t\1+su?-) L-r* jw) ,f+ y n-rry| Amvfux \.L

)yl'"rl ,,ri4 =trd'rwv hq Wry t"**'1'r1 {4

?q ?t*,.*"7vt 4-*f,^,r+ty ut f{ryu(J ry

) lw W u,etrrcp tf*--)* f-,,qO \ l*\?

%ropdl % dr,avr

ri"'r"r,f \^""oa,1';, M

0

b ,yenry ywfl ^fl- ua fniy ?N\d t ''n")lT

*-efd +ry

o'[?)|-flln x

m

f:'t?P aL 'b

]a+W a'ry'*?rr'}1l tf 'PT-

y*r1/ -)t \.Pnrnyt n

a_ fli+ ryv 4Y8 J^d

'J h s l ttlh *r.,f vvoto wn,)

,e"q @)i -tTqul

@

U4^AL ?rfr.lL^ta AnA wa) TJ,4 U-fu-ac-t- +1,.4

lqiL Lil^;) h^ Uil/tt)-,^ tn t4^ p"tr{*,ntu\

a^l ,",1* fr,- ,W*lb^k c*in ; fr&,

'v1a*g,,, tls f Sr*fp . kZ Cs-t)

l@ 1L &-Fr* ,^,^+ kp* c-o,tr.q

0,,,*9 \!.5{r\1& +;[+L*^e) clir";

dr^r**r) -W fu,1o^J.n^l- t'+\ k"l- a Ar-i\rL**"0

Wr*, \W-1, ci^^1 7L<t- pr( lilL

t trt-,r,*ff W (rr4J Mf,nar*f

lr),*, + uJ-il**.1"'w TL& ()/6-

lid**u- +. y+'h a,n$,^*J

&u^ q,wfw ew

W"",L a A).-o<o,n-lrls- dt:urtrT.

tt

5 tI- f.s4 r of 16+- lb< ck r1.o<qo* Ar*#

CD

tra,- ${^ 3odrf

qM W @**,,^

to to,n1 t^r,V^ .lL C"-t*, M-I,A

Wd- y 3o d*{ +1""-^{. l^^

f/f

f,Suff, o* lU r .

Ll,la,l il^* "-l)-.b+ t r,.*p a,u-l w & -Ur"t-,9

LWL h t4t), \,h" Wt fl^,Q- lufu)-t

&-} t^ Lb,nrtdu..1 urlqfl^^ fr M ttu,^r"1

d^/

qfr,,# i,^ b,,, ( fi, MlPo-lt* b{ A4,'i<^o

@ur fr* at*,L'^,,.; Ut^ /0f& L hJ ["u^

r-"

Lbwr,>k) s, h fi-6?^ir 6juu- il"e W

apmarl

tld-k'

-1, fh**

J4

d $u d"ur"**= .' 44* s//^k 'ff"t * a,n/3

&rr^ ; /^j<* uT* f.{,{|u

a / fl-

ru-*iua

^

d,r,^-; n*./ fr4/'- 'r ,u-V--rf-L

muf,'bm. .,V' , ,o , 66 z E e/ zJZz.

@

dA / ' /W @ /-o6r-f ccya.t /zore/ fu-

\U/ru^*J b1 -f^;! Orq{.JL* A}r*l 1af4'

tulAil l^ h"t Q*U u->4r-*t a b,Tl,. Nl;';

W {-- tli,"A'|I hil hr^{lt}+u^,o o' t)occ,-,au*.

(J ut v I

w fu4 Wr ["a{.na Y,* d;li-* 6*r| (

u. C',/r* ,b6?€il

at rr (. ,

t, pfrl;,^ ,fu tu,*4

I

h)lh^ but 'L Wt, k;"* A*4 t' (*, ),L-! 4 aztq*t*/

t M,q gnltua tlrt t-4- "vrr4"/4/ r/a,*t'u-/ a{'

fr^L &ak A(lrj. Oqr\+l s*tanor!1 UJ

Ca*&rdil flqf 'ilu- qn'/e,^ct- le rv'"1 r' ffi

ful'rJl*,l^ tvtl N [4,,ru'AA y /l^ /1.0-*-u.//-

1-,1 p ul/ti f l,ut 4u Lr*rt-L 4hfr, t( f;d4e,^ {^-

W CA)n+/ /LilrJ t(ti,a, d^>Gr* b*,+

6

H'+

rafu--wu laira fi*-Jr*livr-y uL&'-

W ttac.tttrch;{*1 etn'ltnc'L (D d4

arl ({1,TU-+b/ Y4 tu'u* tH* oa ( a(ro .

,t-ta *,^t 1qtu:;:; ;, i-;.fu / ii r,--+-

-

ryr & a (l4u,L;^,-ti W d*(r:,k rn*rl s

/t{,lrtyu4+ ,e!. N @ azr,'l /D/4,,11<4 +

\dlr+-- U*P* frf++*^ a,l.lrg

{ pq- wfu,-cz, X A e+ g8? - (r't.

1

klt),Y^/ry tuN, +I'n] *L u,*

t 1u* T,,* u,-t krLlP,^Rl

d a>ust

Y^ru-Ar.u!- W tlr,llrrrfu ,\{s- b";\lA) ch;

\)

frrr^ W /1r-!^L1 a^-a-{--.- lau-.*, ,}-d4

D

t^ r,-6Vr.r;-,

9q ,c, th1 U^d Wt,t,aJtnl"t-

h,'!,'4r")r#- f "d* X {l* {c+;^.,*,

Atr ffi"rh&,W;W;!r' ,

Wlt^"L f,u*"-W a W Xt

t*f*"

W,^A 4d** n.,,1 + W dgla€rr>,^a-1L

-.f.1W-r,+4* +<,+i"r^- X

p..$,'errro, t^il"o g^4- U^+ L

*H'{^"r$ ks fi*+ fl,g

b.4.^,}.

n-, og L

+

.!yuJ* 'lAil {*l Wu: }rJ d ",,^'-;^",1"1

)rtn)t',,Lrr-o4itl W F;*4" Vr-*' n/u'<4

{, b d'u"r+. l"tt- UJld'h, +;,1 \nl

da^ cr"hl b.&, Pl"* tta& 6,a!^ P.H:,rrn\

Ai^ff<-6 fuA^ry F-xrYv-^,.-!*^

arv,A 'l-t-*+ A,L<- l-.9 cLAa/r,k^g

b Nbv \ hw+ /'1^

.W WbJrv,, t>r"r*uT)r*-, W-rl aJ

[-Luv- UJ { l't'18 %- Al,ro c,on ca-LA W

Arl,a -l-A pru),-J "-ft dla.,'lza- boJJ^+s +

wd'rry

fr,ad- )^^r*

U

qY*

w@

t\* pn'cl.!,,. .,- T!4b"Vra ^J il,Lr. fu\/tr^'t (n:'J-

,lrlXt^/d- W y 1ot*Dv'L'

t\A^M y* wl,tust b*l,ul-r Ur4^L tu/1L6,^fl

aJrrl )v* *< 1"""^.,^1 t o-, lr*\ Le^

b

Ms,

h,ryt A4-tr-i

Ltn--l*-

ltar. /41* Oluat

Urwd [hr, h/,a1 [-;nes.Vol So.Ud]lel-/ez'

'JloOfuY

q 1Ur* o..l.{^0"

Cp',"l AA; o'

e-,'tfun-u{ . frl* rkt< "fldirJ*

l,Uv b"+t^ b"Ntu\ il'!,-l b^lMy,

A*1, eqwh,r'q a" lnh o t,'L t*o')*a

W!r^" ilA).4.+;+'wwo\ wu 4uroJ,u '

-l L,o til. "1,'- fvt^st-uLL trW b".

dt-Vfu ,',|il)a il,a/r!- A- upr,t{'*ov

t"^

'4fu"^^

fr^r^

T"fue. A; g,.r^* rgrLu ,/rr+/ d;t ;h^P"l

{ .kL hr 6r6t, fiJ*- ftlsw/ Da,1^r- (

4.4 +1Q l I q!.---tt)Jr* url,*-@ h - -

W;$"'dd- W tuAb,t a* tt^* pttlt,

*!* At!, Ue aJ,)'t'r)<& hoJ/"u+'-

lhillr- l* /,*rri$ t l,*t^uY-

a* fi!- %ru*.hJlr^y

0v-^r6 b(/t rr 01,* We^^n) l^-L- t1**

ar) CiLu,> il)*L 1'(qtl^.'cua+^

0

+BW

6n*

A,l,'\Ud 7

ffi Now

L MJa^^Gl ( Utl<-, lln,,,,'t- tfLs*+l*A {Ja,

0

Offii^fu ry u- ,"1 +@ W

a^l a)t al.L, Ml /llr/J ,aVU,,nh*Ju-, ,n,'.lL

Irruh o//-tu.

T1". W tt)b',ar*/ c;"j bu '{,"*

t

CAri-\ h,,;,*0 A'?Tu"Lt 41/,rlf*1 il[..^'f

q>UAk\ yrvt dlr^a Ah Lo,nl*'j'^-*t"'-" f-o ?rVL(.

t

W rlfuA\ Cl,ar^;r, 'U*rl- {tY. a-Aa !-'t*t*o'^l X TL'*

% Uf W l,-l t.,u^ b,^,*-p^+/X^*f

nia4't u)^ ae|lyt st^^,^*A uc,".*

tA^76.,,tjn."f.t: lqz, W WCqil@

& ; p"; | *Ll.*\ sld-,,0 'et lrr- wLlu

&;,& ,,,*+ W {ak l.; [ruk LT*

Ft,u M tfurtfr^t', erfr,h, fu fYl'n (tmn'u1L'*

0 !*a ,ur. t*tl.L, U*l /; a-.u,rtr^{

Jr,f,bLJ nW 0L lA D,,.. /^a4^,4-4 on )

0

fl,,

dq

b-llct uLl* r:v-sl 4"* 4-''N'-

U ith'",r t,r,,^@ a^* -t/to- htuf , T, l7(,

/f'-1 . . t - l r , fu

11,"^ Cctv^ l^-r^tq ; d,wdap ff orr;-Ar"^,o

+l,r^4 Al"s. Ur,l"fu4u€+CLll i{r:. 0rn^,--,dna^'t uk,

tn 4w ard* ft,f frl*n"il sk(I

t-

lU,rT^4,- a

t fr;"^f frt*wo'il Sk(r- *'ll

{ilr^\ w;,*1",r",1 y,,,,; io^ .