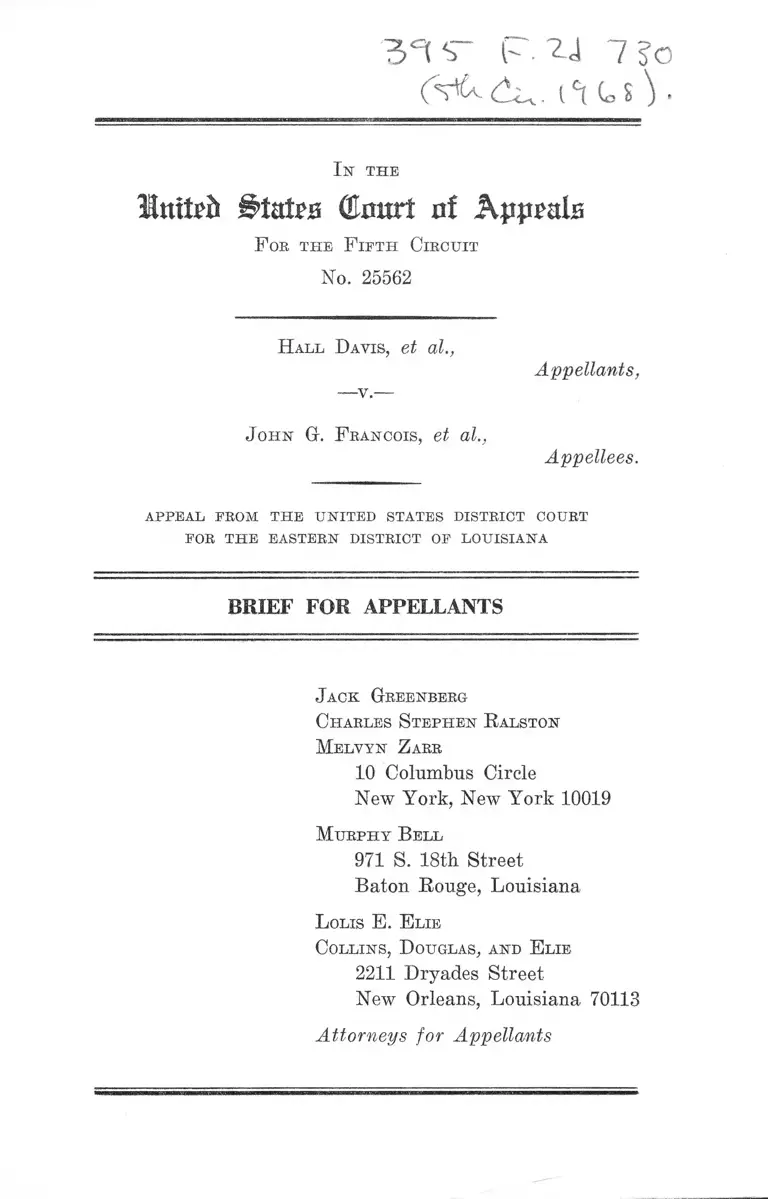

Davis v. Francois Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Francois Brief for Appellants, 1968. 88030522-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ccfa9234-5e55-4777-bce4-e8c3e5c10f74/davis-v-francois-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

3̂ 1 s~ R. 7 ?o

l 1! U

I n the

lu M §>M$b (Eiwrt at Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 25562

H all Davis, et al.,

Appellants,

John G. F rancois, et al.,

Appellees.

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN D ISTRICT OF LO U ISIAN A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Jack Greenberg

Charles Stephen R alston

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

M urphy B ell

971 S. 18th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

L olis E . E lie

Collins, D ouglas, and E lie

2211 Dryades Street.

New Orleans, Louisiana 70113

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Case ............................ ......................... 1

Specifications of Error .................................................... 5

A bgument :

I. The Port Allen Picketing Ordinance Is Un

constitutional on Its Face in Violation of the

First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Con

stitution ........................................................ .......... 6

II. The Decision in Zwickler v. Koota Requires the

Entry of a Declaratory Judgment of Uncon-

stitutionality of the Port Allen Picketing Ordi

nance ......................................................................... 11

Conclusion .......................................... 16

Certificate of Service .......................................................... 17

T able of Cases

Baker v. Bindner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W.D. Ky., 1967) 15

Cameron v. Johnson, 262 F. Supp. 873 (S.D. Miss.

1966), prob. juris, noted------ U .S.------- , 19 L.ed.2d 63

(1967) ............................................................................... 15

Carlson v. California, 310 U.S. 106 (1940) ................... 8, 9

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) .....4 ,1 1 ,13,14

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157 (1943) ...A, 5,11

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966) .............. 4

Guyot v. Pierce, 372 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967) ............. 15

u

PAGE

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1938) ............................ 7

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U.S. 460 (1950) ........... 8

Kelly v. Page, 335 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) ................... 8

Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290 (1951) ...................... 6

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668 (1963) .... 12

Milk Wagon Drivers Union v. Meadowmoor Dairies,

312 U.S. 287 (1941) ........................................................ 8

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105 (1943) ........... 14

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147 (1939) ........................ 7, 9

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940) ..................... 7,8

United Electrical, E & M Workers v. Baldwin, 67

F. Supp. 235 (D. Conn. 1946) .................................... 9

Ware v. Nichols, 266 F. Supp. 564 (N.D. Miss. 1967) 15

Zwickler v. K oota,------U.S.

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1343 .... .............

28 U.S.C. §2283 ..................

42 U.S.C. §1983 .................

19 L.ed.2d 444 (1967)

11,12,13,14

................................ 12

................................... 15,16

................................... 12,15

I n the

Infteft States (tart nf AppraiB

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 25562

H all D avis, et al.,

— v .—

Appellants,

John G. F rancois, et al.,

Appellees.

APPE A L FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOU ISIAN A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the Honorable E.

Gordon West, United States District Judge for the East

ern District of Louisiana, dismissing appellants’ suit seek

ing declaratory and injunctive relief against the picketing

ordinance of the City of Port Allen, Louisiana, as violative

of the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Consti

tution of the United States.

According to the allegations of appellants’ complaint,

which must be taken as true since the court below granted

appellees’ motion to dismiss, appellants are Negro citizens

of the United States residing in West Baton Rouge Parish,

Louisiana. Prior to July 24, 1967, they and other Negro

citizens had been peacefully picketing the West Baton

Rouge Parish School Board Building in the City of Port

2

Allen, Louisiana, protesting “ racist policies of the Board”

(R. 2-3). They marched in an orderly fashion and in small

numbers in front of the School Board’s building (R. 3).

In no way did they obstruct pedestrian or vehicular traffic

or block any entrances to the building (R. 3-4).

On July 24, 1967, apparently in direct response to ap

pellants’ activities, the mayor and board of aldermen of

Port Allen passed City Ordinance No. 11, the ordinance

challenged by this suit.

Section I.

It shall be unlawful for more than two (2) people to

picket on private property or on the streets and side

walks of the City of Port Allen in front of a residence,

a place of business, or public building. Said two (2)

pickets must stay five (5) feet apart at all times and

not obstruct the entrance of any residence, place of

business, or public building by individuals or by auto

mobiles.

Section II.

Any person who violates the provisions of this ordi

nance shall be subject to a fine not exceeding $100.00

or imprisonment for a period not to exceed 30 days,

or both. (R. 4.)

Thereafter every time more than two persons appeared

at the building and peacefully picketed, they were imme

diately arrested and charged with violations of the ordi

nance (R. 4-5).

Subsequent to the arrests, appellants filed a petition for

removal of the criminal prosecutions to the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana. A

motion to remand was filed by the City and the State of

Louisiana (see, R. 39, 22, 35-36). The motion was granted

3

by the court on October 13, 1967, and all the cases were

remanded for trial to the City Court of the City of Port

Allen.

On August 4, 1967, during the pendency of the removal

petition, the present action was filed in the district court.

The complaint invoked the jurisdiction of the district court

under 28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343, 2201 and 2204, and was

brought under the authority of 42 U.S.C. §§1981 and 1983.

It sought a declaratory judgment that City Ordinance No.

11 of the City of Port Allen, Louisiana, was unconstitu

tional as violating the First and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States. It also sought

a temporary restraining order and preliminary and perma

nent injunctions against any enforcement of the ordinance

and specifically against the arrest or prosecution of ap

pellants or members of their class pursuant to the ordi

nance (R. 1-7).

In addition to the facts set out above, the complaint

alleged that in view of the fact that at all times appellants

had picketed in an orderly manner, exercising their rights

of freedom of speech and peaceable assembly, the ordinance

was neither passed nor enforced in good faith. Rather, it

was passed and enforced with the sole purpose and effect

of harassing appellants and their supporters and discour

aging them from picketing and otherwise exercising their

constitutional rights (E. 4-5). It was claimed that there

was no remedy in the state courts adequate to prevent

the arrests and prosecutions of appellants from having a

present “ chilling effect” on their Federal constitutional

rights. Moreover, the arrests were discouraging others

who were sympathetic to appellants’ position from joining

in the picketing. Finally, it was alleged that the ordinance,

in making it a crime for more than two persons to picket

at one time, violated on its face the First and Fourteenth

4

Amendments to the Constitution since it was excessively

restrictive and hence overbroad (E. 5-6).

On October 2, 1967, the defendants, the Mayor of Port

Allen, members of the board of aldermen, the City’s police

chief and the city judge (R. 2), filed a motion to dismiss

for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. The motion dis

puted none of plaintiffs’ allegations of fact but basically

argued that equitable relief was barred by Douglas v.

City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157 (1943) (R. 38-41).

Plaintiffs filed an opposition to the motion to dismiss,

arguing that Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965),

rather than Douglas, governed their right to relief (R. 44-

45). Attached to this opposition was an affidavit of the

three named plaintiffs stating: (1) they, as citizens of

Louisiana living in West Baton Rouge Parish, had been

protesting certain policies of the School Board; (2) ordi

nance No. 11 had caused their arrest, detention, and in

carceration for attempting to exercise their right of free

speech by peacefully picketing; (3) they wished to con

tinue peaceful picketing, but not under the threat of im

mediate prosecution for it; and (4) the enforcement of

the ordinance’s severe limitation of the number of pick

ets had caused and would in the future cause them ir

reparable injury unless the ordinance was declared void

(R. 46).

The case was heard on October 13, 1967, the same day

the removed cases were remanded,1 on an order to show

cause why a preliminary injunction should not issue and

on the motion to dismiss. After hearing the arguments

of counsel, Judge West ordered the case submitted on the

_ 1 The parties agreed that if any Federal remedy lay, it was by injunc

tion and not by removal. See Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808, 829

(1966).

5

record as it stood, i.e., oil the basis of tlie plaintiffs’ un

contradicted complaint and affidavit. On December 8, 1967,

Judge West handed down his order denying all relief to

the appellants and dismissing the action. The primary

basis for the order was that the case was governed by

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, supra, in that no grounds

had been presented showing that “ the intervention of a

Federal Court in order to secure plaintiffs’ constitutional

rights will be either necessary or appropriate” (R. 49).

Therefore, the question of the constitutionality of the ordi

nance “could and should be determined in the orderly

process of a criminal proceeding brought in connection

therewith rather than by the intervention of this Court”

(R. 51). The lower court also expressed the opinion that

the ordinance was “not unconstitutional on its face, and

certainly the ordinance, on its face, does not evidence bad

faith” (Ibid).

The court’s judgment was filed on December 13, 1967

(R. 52), as was plaintiffs’ notice of appeal (R. 53). Also

on December 13, application was made to this Court for

a stay pending appeal of prosecutions of appellants and

members of their class scheduled in the City Court of Port

Allen for December 14. On the same day this Court

granted the stay and subsequently expedited the appeal.

Specifications of Error

1. The court below erred in dismissing the complaint

for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

2. The court below erred in failing to declare the Port

Allen picketing ordinance unconstitutional under the First

and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution.

6

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Port Allen Picketing Ordinance Is Unconstitu

tional on Its Face in Violation of the First and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution.

The specific language of Ordinance No. 11 of the City of

Port Allen, Louisiana, challanged in this action is as

follows:

It shall be unlawful for more than two (2) people to

picket on private property or on the streets and side

walks of the City of Port Allen in front of a residence,

a place of business, or public building (R. 4).2

Appellants contend that this ordinance is unconstitutional

under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Con

stitution.

Appellants start as did the Supreme Court in Kunz v.

New York, 340 U.S. 290, 293 (1951): “ In considering the

right of a municipality to control the use of public streets

for the expression of . . . views, we start with the words of

Mr. Justice Roberts:”

Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they

have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the

public, and, time out of mind, have been used for pur

poses of assembly, communicating thoughts between

citizens, and discussing public questions. . . . The privi

lege of a citizen of the United States to use the streets

2 The rest of the ordinance, making it a crime for two pickets to be

less than 5 feet apart or to obstruct building entrances, is not directly at

issue here, sinee all arrests were made because more than two persons

were present. The ordinance is plainly not severable.

7

and parks for communication of views on national

questions may be regulated in the interest of all; it is

not absolute, but relative, and must be exercised in

subordination to the general comfort and convenience,

and in consonance with peace and good order; but it

must not, in the guise of regulation, be abridged or

denied. Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 515-16 (1938).

Thus, the issue presented by a city ordinance that places

an unconditional ban on all picketing by more than two

persons regardless of time, place, and circumstances is: Is

such a restriction on the right to use the public streets to

express opinions on topics important to the public justifi

able as a necessary regulation of the use of sidewalks?

The approach to be followed in judging such a restriction

has been enunciated by the Supreme Court as follows:

In every case, therefore, where legislative abridgement

of the rights is asserted, the courts should be astute to

examine the effect of the challenged legislation. Mere

legislative preferences or beliefs respecting matters of

public convenience may well support regulation directed

at other personal activities, but be insufficient to justify

such as diminishes the exercise of rights so vital to the

maintenance of democratic institutions. And so, as

cases arise, the delicate and difficult task falls upon the

courts to weigh the circumstances and to appraise the

substantiality of the reasons advanced in support of

the regulation of the free enjoyment of the rights.

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147, 161 (1939).

In 1940, the Supreme Court applied these principles to

the question of whether a state could place an absolute ban

on picketing. In Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940),

the Supreme Court held that any such ban violated the

Fourteenth and First Amendments to the Constitution since

8

peaceful picketing was a protected form of expression. In

both Thornhill and its companion case, Carlson v. California,

310 U.S. 106 (1940), it was indicated that the vice of the

prohibition lay in its being sweeping and unconditional. It

was unrelated in any way to the circumstances surrounding

the picketing, such as time, place, the presence of violence,

or whether entrances or exits to buildings were blocked.

On the other hand, in cases subsequent to Thornhill in

which limitations on or prohibitions of picketing were ap

proved, there were specific facts showing the necessity of

such limitations. Thus, in Milk Wagon Drivers Union v.

Meadowmoor Dairies, 312 U.S. 287 (1941), an injunction

against picketing was justified because of evidence in the

record that violence and intimidation accompanied the

picketing. And in cases such as Hughes v. Superior Court,

339 U.S. 460 (1950), picketing was held enjoinable since it

was shown to be for a purpose ruled unlawful by the state.

Thus, the approach to be taken in judging restrictions on

picketing is whether they are justified in light of time, place,

and circumstances. As this Court stated in Kelly v. Page,

335 F.2d 114, 119 (5th Cir. 1964):

And these rights to picket and to march and to assemble

are not to be abridged by arrest or other interference

so long as asserted within the limits of not unreason

ably interfering with the right of others to use the

sidewalks and streets, to have access to store entrances,

and where conducted in such manner as not to deprive

the public of police and fire protection.

Appellants contend that these standards should be ap

plied in deciding the constitutionality of the Port Allen

ordinance which, while not prohibiting outright all picket

ing, so severely limits and restricts the number of pickets

so as to interfere substantially with its effectiveness.

9

Appellants, of course, do not argue that no restriction

on the number of pickets could be valid.3 Clearly, in situa

tions where there is mass picketing so that the use of the

streets or access to or from buildings is interfered with,

limitation on numbers may be imposed. See, e.g., United

Electrical, JR. & M. Workers v. Baldwin, 67 F. Supp. 235

(D. Conn. 1946) (in a labor dispute, an injunction was

proper that temporarily limited pickets to fifteen where

evidence showed mass picketing that blocked access to en

trances). Nor do appellants contend that under no imagin

able circumstances could a limit of two pickets ever be valid.

What is urged is that a flat, unconditional, absolute ban

on any picketing by more than two persons regardless

of circumstances has not been justified, cannot be justified,

and must fall. Such a limitation cannot be supported by

any legitimate interest of the city in restricting First

Amendment rights involving the use of public sidewalks,

viz., the convenience of the public, access to buildings,

and the free use of sidewalks. It is simply inconceivable

that three, four, or five persons walking peacefully and in

an orderly fashion in front of a public building would auto

matically interfere with the use of sidewalks or with access

to the buildings. Certainly the city has not made any such

showing here. Rather, the record is uncontroverted that

there has been no blockage of streets or doorways. The un

reasonably small number of pickets allowed regardless of

circumstances thus is arbitrary and wholly unrelated to any

valid governmental purpose.4

Indeed, applying the standard of Schneider v. State,

supra, and examining “the effect of the challenged legisla

3 Cf., the language in Carlson v. California, 310 U.S. 106, 112 (1940).

4 Those valid purposes could be adequately accommodated by an ordi

nance that made it unlawful to picket in such a way so as to interfere

with pedestrian or vehicular traffic or with access to buildings.

10

tion” and weighing “ the substantiality of the reasons ad

vanced in support of the regulation of the free enjoyment

of the rights,” 308 U.S. at 161, only one conclusion is pos

sible. The Port Allen picketing ordinance, by restricting the

number of pickets to two persons, was intended to and has

the effect of limiting and destroying the effectiveness of

appellants’ protected activities. Two persons obviously can

have only a small impact on persons to whom appellants

wish to communicate their ideas. And, more importantly,

two and only two Negroes picketing against what they con

sider racist policies of a Louisiana school board are ex

tremely vulnerable to harassment by those antagonistic to

their goals. The conclusion that the city has no valid pur

pose for Ordinance No. 11 is further compelled by the fact

that it was passed in the middle of picketing by the appel

lants in spite of its being at all times peaceful, orderly, and

non-obstructive.

In summary then, appellants contend: (1) that it is clear

that peaceful, non-obstructive picketing such as they have

at all times conducted is protected by the First and Four

teenth Amendments; (2) that any restrictions on it can be

justified only by valid considerations such as keeping side

walks and streets passable and allowing access to build

ings; and (3) that an absolute ban on picketing by more

than two persons regardless of circumstances cannot be

reasonably related to any valid purposes. Therefore, Ordi

nance No. 11 of the City of Port Allen violates the First

and Fourteenth Amendments on its face in that it unduly

restricts and interferes with rights protected by those

amendments and hence is overbroad.

11

II.

The Decision in Zwickler v. Koota Requires the Entry

of a Declaratory Judgment o f Unconstitutionality of the

Port Allen Picketing Ordinance.

The apparent basis for the lower court’s decision was

that, under the rule of Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319

U.S. 157 (1943), the court should not intervene in the en

forcement by the state courts of the Port Allen picketing

ordinance. Rather, “its validity, and the question of the

good or bad faith of its enactors, could be just as well,

and certainly more properly determined in a State crimi

nal proceeding than in a proceeding in equity before this

Court” (R. 51). Appellants contend that this conclusion

was in error in light of the decisions in Zwickler v. Koota,

------U.S. —— , 19 L.ed.2d 444 (1967), and Dombrowski v.

Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965).

In Zwickler, which is identical in all significant respects

to the present case, the plaintiff sought in federal court

declaratory and injunctive relief, challenging the validity

under the federal Constitution of a New York statute mak

ing it illegal to pass out anonymous handbills containing

a statement about any political candidate. The three-judge

district court “ applied the doctrine of abstention and dis

missed the case, remitting appellant to the New York courts

to assert his constitutional challenge in defense of any

criminal prosecution for any future violations of the stat

ute.” 19 L.ed.2d at 448. The Supreme Court reversed and

remanded the case to the district court with orders to

reach and rule upon the issue of the constitutionality of

the state statute. There were four main grounds for the

court’s decision, all of which apply and govern here.

12

First, the Court held that McNeese v. Board of Educa

tion, 373 U.S. 668 (1963), established that the Civil Rights

Acts of 1871 and 1875, now codified in 42 U.S.C. §1983 and

28 U.S.C. §1343, gave jurisdiction to the federal courts, in

dependent of any remedies available in state courts, to en

force federal constitutional rights. That jurisdiction ex

tended not only to claims under the equal protection clause

as in McNeese, but also to claims under the due process

clause, particularly when they involved First Amendment

rights. 19 L.ed.2d at 448-50. Just as in ZwicMer, jurisdic

tion is asserted here under 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 28 U.S.C.

§1343 and appellants seek in the same way vindication of

First and Fourteenth Amendment rights by a federal

forum.

Second, the doctrine of abstention, by which a federal

court may defer to the state courts when presented with a

federal claim, is to be applied only in “ special circum

stances.” 19 L.ed.2d at 450. One of those circumstances

may be present when a statute or ordinance is challenged

on the ground it is vague, i.e., its language is imprecise and

unclear and hence may reach protected activities. It may

be appropriate for a federal court to require a plaintiff to

litigate the issue first in state court, since there a narrow

ing construction may be given the statute that avoids or

modifies the constitutional question. Ibid.

In Zwichler, on the other hand, the claim was not that

the statute was vague; rather, its meaning was agreed by

all to be precise and clear. Plaintiff challenged it on the

ground that it clearly reached and punished federally pro

tected activities, i.e., it was overbroad. Thus, since a state

court could not construe the statute and avoid deciding the

federal question, there was no reason for the federal court,

with its primary obligation of deciding such questions, to

abstain. 19 L.ed.2d at 451-53.

13

The claim of appellants here is identical; the Port Allen

picketing ordinance violates the First and Fourteenth

Amendments because under its clear and precise language

it unduly restricts and impinges upon protected rights.

No claim is or indeed could be made that the language is

vague. Indeed, it would be hard to imagine language more

clear and precise; the ordinance unequivocally prohibits

more than two pickets anywhere, regardless of place, time,

or circumstances, without exception. The only issue to be

decided is whether such a prohibition violates the Consti

tution, and Zwichler makes it clear that the federal courts

must decide the issue and that:

. . . escape from that duty is not permissible merely be

cause state courts also have the solemn responsibility,

equally with the federal courts, ‘ . . . to guard, enforce,

and protect every right granted or secured by the Con

stitution of the United States . . 19 L.ed.2d at 450.

Third, the duty of the federal courts to reach and decide

constitutional questions is particularly compelling when a

statute or ordinance is attacked because it violates the

First Amendment. 19 L.ed.2d at 452. In such a case the

rule of Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 TJ.S. 479 (1965) applies,

for to require a plaintiff, “ to suffer the delay of state court

proceedings might itself effect the impermissible chilling”

of the protected right. 19 L.ed.2d at 452. Here, as well,

plaintiffs demonstrated by their uncontradicted complaint

and affidavit the chilling effect of the ordinance and the

arrests and prosecutions under it. They wish to continue

picketing now; as long as the ordinance is there and as

long as its unconstitutionality has not been definitively de

clared, they and others in their class are “unwilling to in

vite criminal prosecution” (E. 46; 5-6).

14

Finally, the Supreme Court held in Zwichler that Douglas

v. City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157 (1943), relied upon by the

district court in this case, was inapplicable. In Douglas,

the plaintiffs asked only for injunctive relief against prose

cutions under a challenged ordinance. Douglas, said the

court in Zwichler, held only that there was no showing of

special circumstances requiring the issuance of an injunc

tion. This was so because on the same day the Supreme

Court had held, in Murdoch v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105

(1943), that the ordinance challenged in Douglas was un

constitutional. There was no reason to believe that the

Pennsylvania courts would not follow that decision, and

hence it could not be said to he necessary that an injunc

tion against the prosecutions issue. 19 L.ed.2d at 453-54.

In Zwichler, on the other hand, as in the present case,

declaratory relief, as well as an injunction, was requested.

In both cases, plaintiffs seek the effect of Murdoch, that is,

a determination of the constitutionality of a state statute

or city ordinance. On the question of the appropriateness

of declaratory relief, the issue of the necessity and appro

priateness of injunctive relief posed by Douglas is simply

irrelevant. 19 L.ed.2d at 454. A federal court has the duty

to grant the requested declaration (assuming the ordinance

is unconstitutional), “ irrespective of its conclusion as to

the propriety of the issuance of the injunction.” Ibid.

This raises the final issue presented by this case, the

nature of the relief to be granted to the appellants. Zwich

ler makes it clear that the district court erred in relying on

Douglas v. City of Jeannette and dismissing the complaint.

I f the court had clearly expressed no view on the consti

tutionality of the ordinance, Zwichler indicates that the

proper disposition of this appeal would he to reverse the

order of dismissal and to remand for a decision on the

constitutional question. 19 L.ed.2d at 454.

15

However, although its opinion is ambiguous, the court

did express the view, unsupported by any discussion, that

the ordinance is not unconstitutional on its face (R. 51).

Therefore, it is appropriate for this Court to reach and

decide the constitutional question. If the court agrees with

appellants’ contention, set out in Part I, supra, that the

Port Allen picketing ordinance violates rights under the

First and Fourteenth Amendments, then the decision below

should be reversed with directions to enter a declaratory

judgment declaring the ordinance unconstitutional.

As to the prayer for injunctive relief, appellants suggest

that this Court follow the approach taken in Zwickler, Ware

v. Nichols, 266 F. Supp. 564 (N.D. Miss. 1967), and Guyot

v. Pierce, 372 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967) and defer deciding

at this time whether an injunction is necessary. See also,

Baker v. Bindner, 274 F. Supp. 658 (W.I). Ky. 1967). In

Zwickler, the Supreme Court stated that it would be the

task of the district court, after a declaratory judgment was

issued, to decide whether an injunction was necessary or

appropriate, 19 L.ed2d at 454. At the present time this

Court can assume, as did the court in Ware, that the city

and state officials will not act to enforce the ordinance until

the court’s decision is made final, and when final, that the

charges against plaintiffs will be dismissed. 266 F. Supp. at

569. Only if this assumption proves incorrect will the ques

tion of injunctive relief need to be reached.5

5 This disposition is particularly appropriate here since the Supreme

Court has now before it a number of the issues involved in issuing an

injunction against pending criminal prosecutions in Cameron v. Johnson,

262 F. Supp. 873 (S.D. Miss. 1966), prob. juris, noted, ------ U .S .------ ,

19 L.ed.2d 63 (1967). Chief among the questions is whether 28 U.S.C.

§2283 bars injunctive relief against pending state criminal actions. I f the

question of the necessity for injunctive relief were to arise in this ease,

appellants would contend that §2283 was no bar for the reasons set out

by Judge Rives in dissent in Cameron (262 F. Supp. at 882-887) and

Judge Wisdom in his concurrence in Ware (266 F. Supp. at 569-70), viz:

(1) 42 U.S.C. §1983 is an exception to §2283; (2) §2283 is a codification

16

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, appellants pray

that the judgment below be reversed with directions to enter

a declaratory judgment that the Port Allen picketing ordi

nance is unconstitutional under the First and Fourteenth

Amendments.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Charles Stephen R alston

M elvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

M urphy B ell

971 S. 18th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

L olis E . E lie

Collins, D ouglas, and E lie

2211 Dryades Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70113

Attorneys for Appellants

of rules of comity and thus does not absolutely prohibit the issuance of

an injunction where compelling circumstances, the preservation of First

Amendment freedoms, are present; and (3) whatever the effect of §2283

with reference to present prosecutions, it can serve as no bar to enjoining

any arrests or prosecutions initiated after this suit was filed.

17

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that copies of the Brief of Appellants

have been served on the attorneys for appellees by mailing

the same to Hon. Jack P. F. Gremillion, Attorney General,

State of Louisiana, Hon. Thomas W. McFerrin, Assistant

Attorney General, and Hon. Kenneth C. DeJean, Assistant

Attorney General, P.O. Box 44005, Capitol Station, Baton

Rouge, Louisiana 70304, United States mail, postage pre

paid.

Done this day of February, 1968.

Attorney for Appellants

MEiLEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219