Walker v. City of Birmingham Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Petition for Rehearing, 1966. 1261ad47-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cd335af8-a6c1-497c-a266-a45dcd928051/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

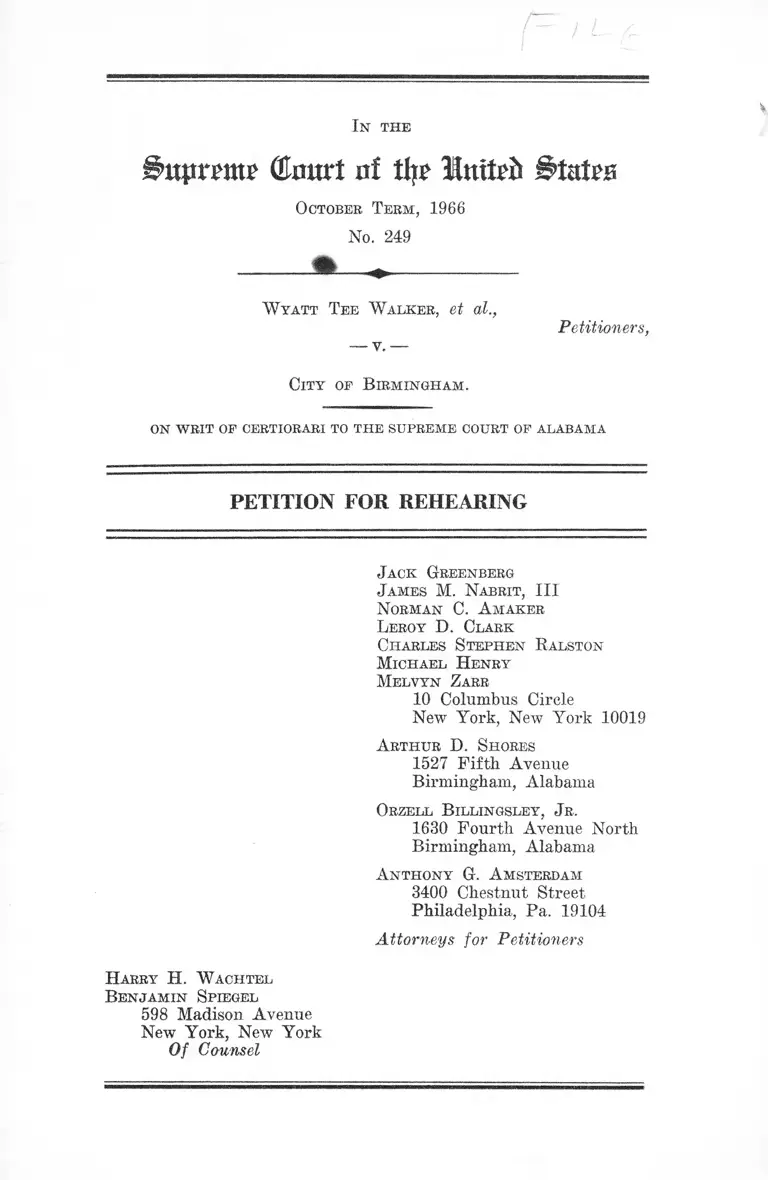

In the

Supreme ( to r t nf tlj? Imtrfc States

October Term, 1966

No. 249

W yatt Tee W alker, et al.,

City of B irmingham.

Petitioners.,

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. A maker

Leroy D. Clark

Charles Stephen Ralston

Michael H enry

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A rthur D. Shores

1527 Fifth Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzbll B illingsley, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Petitioners

H arry H. W achtbl

Benjamin Spiegel

598 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Introduction ................. 1

Reasons for Granting Rehearing .................................... 2

Co n c l u s io n --------- ------- 13

Certificate ......................................................... -................... 14

T able op Cases

Abernathy v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 447 .......................... 12

Arvida Corp. v. Sugarman, 259 F. 2d 428 (2nd Cir.

1958) ............................................ -.................................... 4

Cochran v. State ex rel. Gallion, 270 Ala. 440, 119 So.

2d 339 (1960) .................................................................. 6

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 5 1 .............................. 6,11

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U. S. 374 .......................... 8,12

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 .................................. 12

Lauderdale County Bd. of Education v. Alexander, 269

Ala. 79, 110 So. 2d 911 (1959) .................................. 6

Mills v. Alabama, 384 U. S. 214 ..................................... . 12

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339

IT. S. 306 3

n

PAGE

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 . 8

NAACP v. Alabama, 360 IT. S. 240 ............................ 8

NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 288 . 8

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 ............................. 12

Re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257 ...................................................... 3

Pennington v. Birmingham Baseball Club, Inc., 277

Ala. 336, 170 So. 2d 410 (1964) .............................. 6

Schroeder v. City of New York, 371 IT. S. 208 ........... 3

Sherrer v. Sherrer, 334 U. S. 343 (1948) ....................... 7

In Re Shuttlesworth, 369 IT. S. 3 5 .................................. 8

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 368 U. S. 959 ................... 8

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 373 U. S. 262 ................... 8

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 376 IT. S. 339 ................... 8

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 382 IT. S. 87 .................... 8

Staub v. Baxley, 355 IT. S. 313 .................................. . 12

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 IT. S. 1 .................................. 12

Thomas v. Mississippi, 380 IT. S. 524 ........................... 12

Walker v. City of Hutchinson, 352 IT. S. 112 ............... 3

Wallace v. Malone, 279 Ala. 93, 182 So. 2d 360 (1964) .. 6

Wilson v. State ex rel. Gallion, 270 Ala. 431, 119 So.

2d 337 (1960) .................................................................. 6

O th er A uthorities

Rule 65, F. R. C. P ............................................................. 3,4

Moore’s Federal Practice Rules Pamphlet, 1966 ........... 3

Twentieth Century Fund Report, Administration of

Justice in the South, 1967 .......................................... 9

IT. S. Commission on Civil Rights, 1963 Report ....... 9

In the

g'ltpmtt? of tl|0 InitTft States

October Term, 1966

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alker, et al.,

— v.-

Petitioners,

City of B irmingham.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

PETITION FOR REHEARING

Introduction

Petitioners pray that this Court grant rehearing of its

decision of June 12, 1967, affirming petitioners’ convictions

of criminal contempt. Petitioners earnestly submit that the

opinion of the Court rests upon assumptions concerning

Alabama law and practice which were not the subject of

presentation to the Court and which are incorrect. More

over, the Court’s decision was apparently influenced by a

misunderstanding of petitioners’ fundamental claims. Fi

nally, petitioners submit that the unfortunate consequences

of this Court’s decision have not been adequately explored.

2

Reasons for Granting Rehearing

I.

The majority opinion in effect creates two categories of

governmental restraints trenching upon First Amendment

rights: (1) statutes, ordinances, or executive orders, which

may be ignored; and (2) judicial determinations which

must be obeyed until vacated. Setting aside the question

whether such a bifurcated analysis is rationally support

able, it is evident that the majority uncritically accepted

Alabama’s assertion that the process issued by the State

circuit court merited the respect due litigated judicial de

terminations. In this it erred. The temporary restraining

order in this case was obtained without notice or hearing,

on papers containing no allegation that such notice and

hearing were impossible and, indeed, where such notice and

hearing could easily have been afforded. Whatever effect

this Court decides should be given to litigated court orders

forbidding speech, we pray that it reconsider whether the

same consequences should flow from ex parte orders, where

notice and hearing are possible.

The ex parte restraining order issued in this case should

not have been placed in the same category as litigated

injunctions, even assuming that the latter are rationally

distinguishable from statutes which, if patently unconsti

tutional, can be ignored. The majority assumed that there

is no distinction between litigated injunctions and the re

straining order here, but there is little support for this

assumption. In fact, the rationale of the majority opinion

itself suggests that this assumption is mistaken, for the

only reason for treating an injunction differently from a

statute is that, given normal judicial procedures, the rights

3

of the parties subject to the injunction will have come

under the scrutiny of a court prior to the issuance of the

injunction. Both sides will have had their day in court.

There is no generic difference between efforts to dissolve

an ex parte temporary restraining order and defenses

against enforcement of a permit ordinance. There is no

reason to believe that one is more expeditious or different

in form or content than the other. Given this rationale,

there is no reason to place ex parte restraining orders in

the same category as litigated injunctions.

The Due Process clause requires, at a minimum, “ that

deprivation of life, liberty, or property by adjudication

be proceeded by notice and opportunity for hearing appro

priate to the nature of the case.” Mullane v. Central

Hanover Bank <& Trust Co., 339 U. S. 306, 313. Thus, in

Walker v. City of Hutchinson, 352 U. S. 112, notice by

publication to a resident landowner was rejected. And

see, Schroeder v. City of New York, 371 U. S. 208. The

ex parte hearing smacks of Star Chamber proceedings

without counsel. See Re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257.

Rule 65 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, in con

trast, provides the strictest possible safeguards against the

issuance of restraining orders without notice and oppor

tunity for hearing. In recommending amendment of the

rule in 1966 to tighten the safeguards, the Advisory Com

mittee stated:

In view of the possibly drastic consequences of a

temporary restraining order, the opposition should be

heard, if feasible, before the order is granted.

(Moore’s Federal Practice Rules Pamphlet, 1966, p. 1109.)

New Rule 65, further tightening earlier safeguards, re

4

quires submission of an affidavit setting out all attempts

to give notice with the motion for a temporary restraining

order, in addition to proof of immediate and irreparable

injury.

Petitioners submit that the principle underlying Rule 6b

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is of constitutional

dimensions; failure to give notice and hearing “ offends

our customary notions of fair play.” 1

It is a matter of common knowledge among attorneys

of experience that almost no court will issue a restraining

order without notice to the adverse party and hearing,

unless the unfeasibility of giving such notice is demon

strated. Yet the City of Birmingham did not allege in

its papers requesting the order, nor did the Alabama court

find, that notice could not be given to the petitioners. In

fact, notice could easily have been given; the petitioners

were served copies of the order shortly after it was issued.

The implications for First Amendment freedoms of ele

vating the ex parte temporary restraining order issued in

this case to the level of a litigated injunction—and distin

guishing it from equally lawless statutes—have not been

presented to, or considered by, the Court. For that reason

alone rehearing is appropriate.

1 Arvida Corp. v. Sugcirman, 259 F. 2d 428, 429 (2nd Cir. 1958)

(Lumbard, J. concurring).

&

II.

The linchpin of the majority opinion is the assumption

that petitioners, by filing a motion to dissolve the injunc

tion in the state circuit court on April 11, 1963, could have

received prompt and impartial determination of their First

Amendment claims:

This case would arise in quite a different constitu

tional posture if the petitioners, before disobeying

the injunction, had challenged it in the Alabama courts,

and had been met with delay or frustration of their

constitutional claims. But there is no showing that

such would have been the fate of a timely motion to

modify or dissolve the injunction. There was an in

terim of two days between the issuance of the injunc

tion and the Good Friday march. The petitioners give

absolutely no explanation of why they did not make

some application to the state court during that period.

(Slip Op. p. 11)

The critical assumptions contained in this passage did not

receive briefing and argument commensurate with their

significance as revealed in the court’s opinion; they became

apparent only upon its publication. Unfortunately, thej ̂are

mistaken.

This is not a case where state law procedures requiring

speedy review of prior restraints of First Amendment

rights have been bypassed. Alabama has no such require

ments ; the circuit court was in no way constrained to rule

expeditiously on any motion to dissolve its ex parte injunc

tion. Nor was the Supreme Court constrained to rule ex

peditiously. Until Alabama takes affirmative steps to man-

6

date prompt determination of such prior restraints, see

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51, then petitioners should

not be punished in the name of respect for fictional pro

cedures.

The record does not make unambiguously clear why peti

tioners “did not make some application to the state court

[on April 11, 1963]” (slip op. p. 11). But the record, seen

in the context of the history of the time, warrants some

general conclusions. In retrospect it appears that a num

ber of factors operated.

First, petitioners would show that they had no reason to

believe that a motion to dissolve the injunction, even if it

could have been prepared and filed on April 11, would have

escaped the uncertainty, delay and frustration integral to

Alabama procedure. Petitioners have reviewed Alabama

cases dealing with appeals from temporary injunctions.

They make it apparent that disposition of a motion to dis

solve within the Alabama courts would probably have taken

at least a matter of months and perhaps longer.2

2 See Pennington v. Birmingham. Baseball Club, Inc., 277 Ala.

336, 170 So. 2d 410 (1964) (injunction against picketing a baseball

stadium; final adjudication five months later, after the close of the

baseball season) ; Wilson v. State ex rel. Gallion, 270 Ala. 431, 119

So. 2d 337 (1960) (injunction against money lender preventing the

future usurious loans and collection of previous transactions; final

adjudication took nine months) ; Cochran v. State ex rel. Gallion,

270 Ala. 440, 119 So. 2d 339 (1960) (also an injunction against

usurious loans; nine and one-half months until terminal decision) ;

Wallace v. Malone, 279 Ala. 93, 182 So. 2d 360 (1964) (injunction

to prevent cancellation of a textbook contract; four and one-half

months from the overruling of the motion to dissolve until reversal

of the Circuit Court decision by the Alabama Supreme Court);

Lauderdale County Board of Education v. Alexander, 269 Ala. 79,

110 So. 2d 911 (1959) (injunction against the construction of a bus

barn in a residential neighborhood; six months until final adjudica

tion).

7

The state circuit court was not constrained to rule ex

peditiously on a motion to dissolve. Nor was the Supreme

Court of Alabama constrained to grant expeditious review,

although coneededly it does have the power to do so pur

suant to its Rule 47.3 But even if Rule 47 were successfully

invoked, a trial transcript must be prepared,4 the appeal

must be docketed and time must be taken for preparation

of briefs and arguments and consideration by the Supreme

Court, none of which are dispensed with by Rule 47. In

the most expedited proceedings an indeterminate but

lengthy period of time would be consumed during which an

invalid temporary restraining order would be suppressing

freedom to protest in Alabama.

Of course it may be maintained that petitioners could

have put off their marches—perhaps a few days, a few

weeks, perhaps even a few months, while petitioners sought

relief in the state courts. Such an observation blinds itself

to the realities of Birmingham in the Spring of 1963. No

purpose would be served in rehearsing that history here.

Suffice it to say that the oppressiveness of Birmingham

officialdom revealed by these events sparked national senti

ment for comprehensive civil rights legislation. “We can

not as judges be ignorant of that which is common knowl

edge to all men” (Mr. Justice Frankfurter in Sherrer v.

Sherrer, 334 U. S. 343, 366 (1948)).

Second, petitioners’ unvaried contacts with Alabama jus

tice offered absolutely no prospect that meaningful relief

3 Following decision in the trial court, counsel may on three days’

notice petition the court to reduce the time for filing briefs and

submitting the appeal.

4 It may be assumed that the transcript would be of approximately

the same length as the voluminous record in the instant case.

8

would have been granted. Certainly, one of petitioners’

representatives (R. 352) had been denied a permit a short

time before the event in question. There was an effort to

prove—which was denied—that petitioners were remitted

to a procedure for securing a permit that all other citizens

were not required to follow.

It is common knowledge, and the U. S. Commission on

Civil Rights has recorded that:

. . . While police action in each arrest may not

have been improper, the total pattern of official ac

tion, as indicated by the public statements of city

officials, was to maintain segregation and to suppress

protests. The police followed that policy and they

were usually supported by local prosecutors and courts.

(1963 Report of the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights,

Govt. Printing Office, 1963, p. 112.)

Indeed, in this very cause, attempts to obtain permits

to parade were rebuffed, we submit, unconstitutionally.5 6

Moreover NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 360 U. S.

240, 377 U. S. 288, Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 368

IT. S. 959, 373 U. S. 262, 376 IT. S. 339, 382 U. S. 87,8 and

Gober v. City of Birmingham, 373 IT. S. 374, hardly inspired

confidence that normal functioning of Alabama justice

would have been accelerated in order to grant these peti

tioners their constitutional right to protest against state

enforced racism. On the contrary the opposite should

rightly have been expected.

6 The majority opinion noted that Miss Hendricks, who requested

and was denied a permit, was not a petitioner. But she was acting

on the petitioners’ behalf (R. 352-53).

6 See also In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U. S. 35.

9

Third, at the time in Birmingham, there were exceed

ingly few lawyers representing civil rights defendants.7

There were hundreds of illegal arrests; these few counsel

were deeply involved in judicial hearings and securing re

lease of prisoners on bail. Opportunity for detached con

templation and for legal research were at a minimum.

These physical factors, compounded by the ambiguity of

the legal posture of the situation and the fact that the

injunction and underlying ordinance were apparently un

constitutional, probably all contributed in varying degrees

to the decision against cancelling the Good Friday and

Easter Sunday marches. But when events move quickly

and large numbers of people are involved, the basis of

decision often is not articulated, and it would be impos

sible to assemble a catalogue of reasons why the solution

evolved as it did. It may be observed, however, that this

type of uncertainty may recur in free speech situations

involving suddenly-issued temporary restraining orders,

and that the rule of this case means “ When in doubt, re

frain from exerising First Amendment rights.” But we

submit that the uniform rule of the decisions of this Court

dealing with the vagueness doctrine and prior restraints

has heretofore been to the contrary.

III.

The demonstrations of 1963 are over and, in a funda

mental sense, the demonstrators have been vindicated by

the nation through passage of the Civil Bights Act of 1964.

Sentences of 5 days are not intolerable, and, were the

consequences of this Court’s decision for the nation and

7 See, 1963 Report, United States Commission on Civil Rights,

pp. 117-119; and see, Report of the Twentieth Century Fund, Ad

ministration of Justice in the South, pp. 2-6, 1967.

10

its democratic process not so mischievous, petitioners would

have little cause for complaint. But the damage done to

First Amendment rights, should this decision stand, will

be incalculable. If a vague and overbroad statute need not

be obeyed because of its chilling effect upon free speech,

how much more chilling is a vague injunction incorporating

that statute issued without notice under cover of night!

A statute can at least be contemplated in advance; counsel

can maturely assess its validity and give appropriate ad

vice. But this course was not possible here.

Petitioners hazarded their liberty on the belief—cor

rectly, we submit—that the injunction was offensive to the

First Amendment. Had they been wrong, they would have

no complaint. But they were right; and yet this Court says

that they must be punished. Petitioners must be punished,

the Court says, because the effective modes of legal redress

in Alabama must be respected. But, as has been shown,

prompt and effective legal procedures in Alabama to curb

prior restraints on First Amendment rights are not evi

dent. At a minimum, the cause should be remanded for a

thorough canvass of Alabama law and practice to test the

validity of this assumption.

The Court’s decision leaves the law of prior restraints

in a shambles. Even unconstitutionally vague statutes have

never been so vague as to require that would-be speakers

appraise the speed by which state courts can act. How do

counsel learn of a court’s workload, or the state of a judge’s

health, or the difficulty he may have in deciding issues of

difficulty! How does another court pass on whether a case

moved as quickly as possible! Should counsel now advise

those under ex parte temporary restraining orders that

are incompatible with the First Amendment that they must

nonetheless yield to those unconstitutional restraints while

11

a state court or courts take 10 days, or 20 days, or 90 days

or more to determine the matter! Is appeal to a single

appellate court enough! Must counsel advise his client

to obey the unconstitutional prior restraint while he seeks

review in an intermediate appellate court, the state su

preme court or, indeed, in this Court! Until now, the an

swer was plain: If effective and prompt review is not man

dated under state law, then prior restraints trenching on

First Amendment rights need not be obeyed. Freedman

v. Maryland, supra.

Moreover, the majority opinion reveals a misunderstand

ing of petitioners’ position-—which apparently they ex

pressed unclearly. This misunderstanding markedly af

fected the court’s decision (Slip Op. p. 7) :

We are asked to sa)̂ that the Constitution compelled

Alabama to allow the petitioners to violate this in

junction, to organize and engage in these mass street

parades and demonstrations, without any previous ef

fort on their part to have the injunction dissolved or

modified, or any attempt to secure a parade permit

in accordance Avith its terms.

Nowhere is this misunderstanding more evident than in

the majority opinion’s concluding paragraph, which refutes

an argument never made by petitioners (Slip Op. p. 13):

[N]o man can be judge in his own case, hoAvever

exalted his station, h ow ever righteous his motives, and

irrespective of his race, color, politics or religion.

Petitioners flatly deny that they sought to be judges in

their OAvn case. They sought only to have their ease judged

according to standards compatible Avith the First Amend

12

ment. They sought only the same rights they clearly would

have had if they had been prosecuted under the Birming

ham parade permit ordinance rather than under the injunc

tion which incorporated it. While it is difficult to tell the

extent to which these misapprehensions influenced the ma

jority’s conclusions, further briefing and argument would

place beyond dispute what petitioners’ contentions actually

are.

Rehearing is granted rarely, and never lightly. But the

implications of this decision are so dangerous to First

Amendment freedoms that it deserves reconsideration.8

For those concerned with law and order, as well as equal

justice and social progress, this is the worst of all possible

decisions. The peaceful protest movement—no matter how

dissonant it may have become—has channeled dissatisfac

tion with deeply ingrained injustices into constructive so

cial change. In the face of boiling resentment against

long-standing injustices and ugly traditions of oppression,

the peaceful protest movement has achieved not only some

measure of equal justice and social progress, but has eon-

8 For example, by the device of an ex parte injunction that in

corporates an unconstitutional statute, a state can now suppress

for an indefinite period the distribution of handbills by adherents

to a cause that it finds distasteful, see, Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S.

313, and can prevent the peaceful and orderly use of a park or other

public gathering place by an unpopular religious group, see, Nie-

motko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268; Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S.

290. On the eve of an election, city officials can suppress the pub

lication of a newspaper which they know is hostile to their can

didacy, see, Mills v. Alabama, 384 TJ. S. 214. A public meeting to

be addressed by persons whose views state or city officials fear can

be stopped, see, Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1. “Freedom

Rides” can be halted, see, Abernathy v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 447;

Thomas v. Mississippi, 380 U. S. 524, as can, under the very in

junction issued herein (R. 32, 38), “sit-ins” , even though a city

ordinance requires segregation in restaurants, see, Gober v. Bir

mingham, 373 U. S. 374.

13

tributed to stability. By this decision the Court devastates

the peaceful protest movement and leaves the field to cap

ture by those violent elements who do not stop to read

injunctions.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioners request that the

Court grant rehearing and reverse the judgment below.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. A maker

Leroy D. Clark

Charles Stephen R alston

Michael H enry

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A rthur D. Shores

1527 Fifth Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Petitioners

Harry H. W achtel

Benjamin Spiegel

598 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Of Counsel

14

Certificate

I, Melvyn Zabk, a member of the Bar of this Court and

counsel for petitioners herein, hereby certify that the fore

going Petition for Rehearing is presented in good faith

and not for purposes of delay.

Attorney for Petitioners

38