Warth v. Selden Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Warth v. Selden Brief Amicus Curiae, 1974. a35bf884-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cd4e797d-5e31-4ce8-a35d-e7eb3a2b1722/warth-v-selden-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

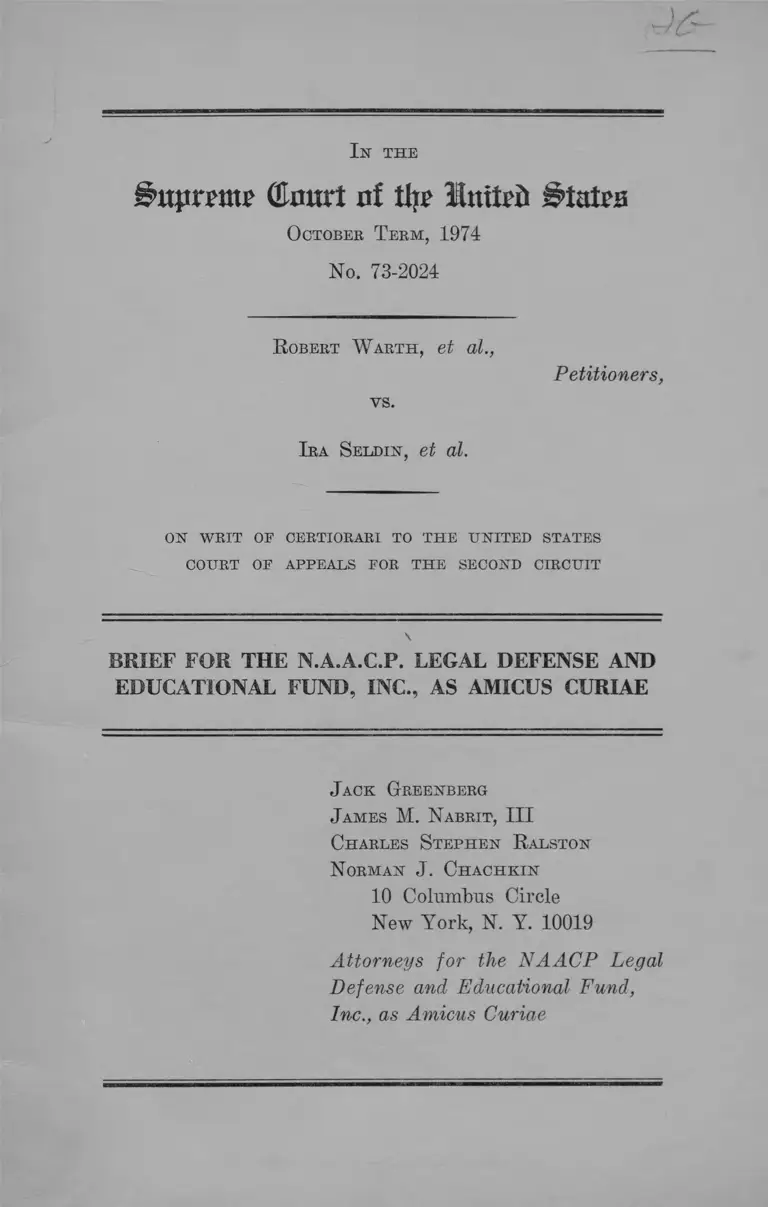

In t h e

g’upratte (Eourt of tljt' Itnitcii States

O ctober T e r m , 1974

No. 73-2024

R obert W a r t h , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

I ra S e l d in , et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

J a c k G r ee n b e r g

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

C h a r l e s S t e p h e n R a l st o n

N o r m a n J . C h a c h k i n

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., as Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amiens Curiae .............................................. 1

I. The Denial of Standing to Challenge Exclusion

ary Zoning to Excluded Minorities Would Frus

trate Achievement of Fair Housing Throughout

the United States ...................................................... 3

II. Individual Black and Spanish-Surnamed Plain

tiffs, Housing Council in the Monroe County

Area, and Rochester Home Builders Association

Have Standing to Challenge the Penfield Zoning

PAGE

Ordinance ................................................................... 6

C o n c l u s io n ......................................................................... 12

Cases:

Allee v. Medrano, ------ U.S. — 40 L.Ed.2d 566

(1974) .................................. ........................................ 6,9,11

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ......................4,10

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960) ...................... 9

Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 (1954) ........ .................. 8

Blackshear Residents Organ, v. H.A. of City of Austin,

347 F. Supp. 1138 (W.D. Texas 1971) ....................... 10

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ...................3,4,10

California Bankers Assn. v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21 (1974) 6

Cypress v. Newport News Gf. & N. Hosp. Ass’n, 375

F.2d 648 (5th Cir. 1967).................................................. 8

Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179 (1973) .............................. 6

Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972) ...................... 4

11

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926) ....... 8

Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S. 83 (1968) .................................. 6

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ................... 5

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U.S. 668 (1927) ....................... . 4

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir.

1971) affirmed en banc, 461 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1972) 5

James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971) ......................... 8

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341

U.S. 123 (1951) .......................................................... 9

Kennedy Park Homes Assoc, v. City of Lackawanna,

436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970) cert, denied 401 U.S.

1010 (1971) ...................................................................... 10

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 269 (1939) .......................... ...... 3

Linda R.S. v. Richard D., 410 U.S. 614 (1973) ........... 6

Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U.S. 293 (1961) ................... 9

Milliken y . Bradley, -------- U.S. ---------, 41 L.Ed.2d 1069

(1974) ............................................................................... 5

Moose Lodge v. Irvis, 407 U.S. 163 (1972) ................... 4

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449

(1958) ............................................................................... 9

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .... ...................... 9,11

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F.2d 920 (2nd Cir. 1968) .......................................... 10

Park View Heights Corp. v. City of Black Jack, 467

F.2d 1208 (8th Cir. 1972)

PAGE

10

Ill

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925) ........... 9

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ....................... 5

Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930) ...................... 4

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1972) .................................. 4

Rogers v. Panl, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ...................... ........ 9

Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 (1972) ................... 9

Sisters of Prov. of St. Mary Woods v. City of Evanston,

335 F. Supp. 396 (N.D. 111. 1971) .................... 10

Smith x. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) ........... 3

Southern Alameda Span. Sp. Organ, v. City of Union

City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970) .............................. 10

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969) .... 10

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205

(1972) ...............................................................................6,10

United Farm Workers of Florida Housing Prop, Inc.

v. City of Delray Beach, 493 F.2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974) 10

United States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669 (1974) ....6, 7, 9,10,11

Village of Belle Terre v. Boraas, 416 U.S. 1 (1974) ..... 4, 8

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) ...................... 3

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 3601 ................................................................. 2, 4

The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974,

Pub. L. No. 93-383 ... ...................................................... 4

Other Authorities:

Equal Opportunity in Suburbia 29-35 (July 1974) ....... 5

PAGE

I n t h e

g'ltpn'uu' Ghmrt of tin' Unitrii States

O ctober T e r m , 1974

No. 73-2024

R obert W a r t h , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

I r a S e l d in , et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE N.A.A.C.P. LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of Amicus Curiae*

The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under the

laws of the State of New York in 1939. It was formed to

assist Negroes to secure their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its pur

poses include rendering legal aid gratuitously to black

persons suffering injustice by reason of race who are un

able, on account of poverty, to employ legal counsel on

# Letters of consent from counsel to the filing of this brief for

the petitioners and the respondents have been filed with the Clerk

of the Court.

2

tlieir own behalf. The charter was approved by a New York

court, authorizing the organization to serve as a legal aid

society. The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. is independent of other organizations and is sup

ported by contributions from the public. For many years its

attorneys have represented parties in this Court and the

lower courts, and it has participated as amicus curiae in

this Court and other courts, in cases involving many facets

of the law.

The Legal Defense Fund receives many requests for as

sistance in the enforcement of fair housing laws, and par

ticipates in many cases in both federal and state forums

to advance the national policy of “ fair housing through

out the United States,” 42 U.S.C. § 3601. Our experience

indicates that discrimination in housing transactions neces

sarily causes injury to a wide circle of persons, including

potential renters or purchasers, other residents of the

building or neighborhood, builders, and owners. Adequate

enforcement of fair housing requires that a commensu-

rately broad range of persons and organizations be en

titled to commence administrative and judicial proceedings.

The Legal Defense Fund is therefore interested that re

quirements in fair housing cases not be more onerous than

in other areas of law, lest victims of racial exclusionary

zoning and other discriminatory housing practices be de

prived of access to the judicial forum. Moreover, in our

experience, fair housing cases can only be successfully

litigated with advance preparation and the ability to de

vote the time, effort and expense necessary to prosecute

complaints. Often “the only effective adversary” , Bar-

rows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 259 (1953), with sufficient

resources and independence to challenge exclusionary zon

ing may be a membership association suing in behalf of

injured members.

3

I.

The Denial of Standing to Challenge Exclusionary

Zoning to Excluded Minorities Would Frustrate Achieve

ment of Fair Housing Throughout the United States.

As this Court has said, the Constitution “nullifies so

phisticated as well as simple minded modes of discrimina

tion.” Lane v. Wilson, 307 U.S. 269, 275 (1939).1 At issue

in this case is whether a town can escape the scrutiny of

a federal court that would result if it enacted an ordinance

that explicitly excluded blacks and other minorities,2 by

enacting and administering- a zoning scheme racially neu

tral on its face that nevertheless had the same purpose

and effect.3 The Court of Appeals in this case, by erect

ing rules of standing more stringent than those that

govern in other areas of the law, has effectively insulated

the Town of Penfield from a challenge to its policies.

The Second Circuit held, in essence, that poor black and

other minority persons who allege that they are prevented

by the policies of the defendants from renting or purchas

ing housing cannot maintain this action; rather, their only

apparent remedy is to wait and hope that other persons,

specifically potential home-builders, will bring suit. Com

pletely overlooked by the Court below is the fact that the

interests and goals of a construction firm may be quite

different from those of a potential black renter or pur

chaser. Also overlooked is the fact that in another case

where a home-builder was the sole plaintiff there might be a

question as to his standing in an action seeking to over

turn a decision not to grant him a permit, to rely solely

1 See also, Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 132 (1940).

2 Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

3 See, Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886).

4

on the ground that the reason for the denial was to deprive

third parties, i.e., blacks and minorities, of their constitu

tional rights. Compare, Moose Lodge v. Irvis, 407 U.S.

163 (1972), with, Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972)

and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953). Thus, the

net result of the decision might he that no one could chal

lenge policies that clearly violate the Constitution, a result

that this Court has often refused to sanction. See, e.g., Roe

v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113,125 (1972).

Amicus urges that the decision of the court below,

therefore, is inconsistent with the goal of enforcing the

national policy of “ fair housing throughout the United

States,” 42 U.S.C. § 3601,4 by making it impossible for those

ultimately injured by exclusionary zoning policies to chal

lenge them. The discriminatory impact of racial zoning has

been recognized at least since Buchanan v. Warley, 245

U.S. 60 (1917). See also, Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U.S. 668

(1927); Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930); Village of

Belle Terre v. Boraas, 416 U.S. 1, 6 (1974). Notwithstand

ing applicable Reconstruction amendments and laws, and

long-standing judicial precedent, exclusionary zoning prac

tices such as lot size, restrictions on multi-family struc

tures, density limitations, and discriminatory grant of vari

ances persist as barriers to racial integration of metro

politan areas across the nation. Indeed, the United States

Commission on Civil Rights has recently documented that

exclusionary zoning by local authorities is a principal factor

in maintaining dual housing markets in metropolitan areas

4 The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, Pub.

L. No. 93-383, also affirms as an aim, “ the reduction of the isola

tion of income groups within communities and geographical areas

and the promotion of an increase in the diversity and vitality of

neighborhoods through the spatial deconcentration of housing op

portunities for persons of lower income and the neutralization of

deteriorating or deteriorated neighborhoods to attract persons of

higher income.”

5

in which the black and the poor are restricted to decaying

central cities surrounded by closed white, affluent suburban

communities. Equal Opportunity in Suburbia, 29-35 (July

1974).5

Racial zoning is a particularly pernicious form of hous

ing discrimination in that its effect is wholesale exclusion.

This is not a case as simple as the one where a man

with a bicycle or a car or a stock certificate or even a

log cabin asserts the right to sell to whomsoever he

please, excluding all others whether they be Negro,

Chinese, Japanese, Russians, Catholics, Baptist, or

those with blue eyes. We deal here with a problem in

the realm of zoning . . . whereby a neighborhood is

kept “white” or “ Caucasian” as the dominant interests

desire. Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 381 (1967)

(Justice Douglas concurring).

Exclusionary zoning can also have the effect of facilitat

ing discrimination in the provision of public schools, see,

e.g., Milliken v. Bradley,------U .S .------- , 41 L.Ed. 2d 1069

(1974), municipal services, see e.g., Hawkins v. Town of

Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir. 1971), affirmed en banc, 461

F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1972), and in the exercise of other civil

rights, see, e.g., Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960), by efficiently creating racially distinct neighbor

hoods and communities. It would be anomalous, there

fore, if those persons with the greatest interest in the

eradication of exclusionary policies cannot challenge them

because of artificially strict standing requirements.

5 In the Rochester metropolitan area, for instance, the black

population in 1970 was 49,647 in Rochester and 2,571, in suburban

towns, as compared to total population figures of 296,233 in

Rochester and 415,684 in the suburbs. The black population of

suburban Penfield is 60 out of a total population of 23,782. A p

pendix on Appeal 228-29. [hereinafter “Appeal App.” ]

6

Individual Black and Spanish-Surnamed Plaintiffs,

Housing Council in the Monroe County Area, and Roch

ester Home Builders Association Have Standing to Chal

lenge the Penfield Zoning Ordinance.

The issue in this case is whether any of the plaintiffs

or the intervenor has made allegations adequate to confer

standing to challenge the Penfield zoning ordinance as

enacted and administered.6 In affirming the motion to dis

miss, the Second Circuit disregraded express allegations

and averments in the record of “ threatened or actual in

jury resulting from the putatively illegal action,” Linda

R.S. v. Richard D., 410 U.S. 614, 617 (1973), that estab

lish “ a logical nexus between the status asserted and the

claim sought to be adjudicated,” Flast v. Cohen, 392 U.S.

83, 102 (1968). The rule is that, “ federal plaintiffs must

allege some threatened or actual injury resulting from

the putatively illegal action before a federal court may

assume jurisdiction.” (emphasis added) Linda R.S. v. Rich

ard D., supra, 410 U.S. at 617.

The Second Circuit, however, misconstrued this stan

dard and premised dismissal on the judgment that none

of the individuals or associations “has suffered from any

of the specific, overt acts alleged,” i.e. that the allega

tions of injury were in fact untrue. In so deciding, the

Court of Appeals failed to make the distinction explicitly

recognized by this Court in Trafjicante v. Metropolitan

Life Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205, 209 (1972) and in United

States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669 (1974), between the al

II.

6 Because standing is clear as to certain individuals and asso

ciations, this amicus brief will not discuss the standing of all of

them. See, Doe v. Bolton, 410 U.S. 179, 189 (1973); California

Bankers Assn. v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21, 44-45 (1974).

7

legations of the complaint and what may be proved in

the trial on the merits.7

The complaint specifically alleges that the black and

Spanish-snrnamed class action plaintiffs are deprived of

fair housing opportunities in Penfield on account of race

and poverty by the operation of the zoning ordinance.

Looking at the allegations as a whole (rather than by

each plaintiff separately, as did the court below), the

minority plaintiffs seek to show that: (1) the exclusionary

zoning scheme was adopted and administered to exclude

minorities; (2) it in fact has succeeded in its purpose;

(3) as part of this scheme permit requests for low-income

multiple housing have been denied; (4) the named plain

tiffs are black, Spanish-surnamed, low-income persons who

wish to live in the town; and (5) they have been unable

to do so because of the success of the exclusionary zoning

scheme.8 If plaintiffs prevail on the merits, the black

7 “We deal here simply with the pleadings in which the appel

lees alleged a specific and perceptible harm that distinguished them

from other citizens who had not used the natural resources that

were claimed to be affected. If, as the railroads now assert, these

allegations were in fact untrue, then the appellants should have

moved for summary judgment on the standing issue and demon

strated to the District Court that the allegations were sham and

raised no genuine issue of fact. We cannot say on these plead

ings that the appellees could not prove their allegations which, if

proved, would place them squarely among those persons injured

in fact by the Commission’s action, and entitled under the clear

import of Sierra Club to seek review.” United States v. SCRAP,

412 U.S. at 689-90.

8 The complaint states:

FO U RTEEN TH : That the statute as enacted and/or admin

istered by the defendants, has as its purpose and in fact,

effects and propagates exclusionary zoning in said Town with

respect to excluding moderate and low income multiple hous

ing and further tends to exclude low income and moderate

income and non-white residency in said Town and thereby

deprives persons and has deprived persons including the

plaintiffs Harris, Ortiz, Broadnax, Reyes and Sinkler of the

8

and Spanish-surnamed plaintiffs will personally benefit by

achieving the same right to rent or purchase property in

Penfield presently possessed by white persons, but denied

the class of racial minorities by the present ordinance.

See James v. Valtierra, 402 U.S. 137 (1971). Thus, here

the individual minority-group plaintiffs have alleged a

direct relationship between the correction of the injury

suffered (exclusion from the town), and the relief sought

(ending of the scheme of evclusionary zoning).9

same right to inherit, purchase, lease, sell and/or convey real

property and to make and enforce contracts and to the full

and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security

of persons and property as are enjoyed by persons presently

living in said Town. Appeal App. at 9.

Similar allegations are made in paragraphs Sixteenth, Appeal

App. at 9-10; Seventeenth, Appeal App. at 10-11; Eighteenth,

Appeal App. at 11-12; Nineteenth, Appeal App. at 12-13; and

Twentieth, Appeal App. at 13-14. More particularly, the com

plaint alleges that Mr. Ortiz, a Puerto Rican, “ is denied certain

rights by virtue of his race.” and that Mr. Ortiz “ is employed

in the Town of Penfield, New York, but has been excluded from

living near his employment as he would desire by virtue of the

illegal, unconstitutional and exclusionary practices.” Appeal App.

at 6. Mr. Ortiz subsequently filed an affidavit that avers in de

tail the deprivation on account of race and poverty alleged, A p

peal App. at 188-202. Affidavits were also submitted in behalf of

similar allegations of injury to Ms. Broadnax, a black person,

Appeal App. at 203-09; Ms. Reyes, a Puerto Rican, Appeal App.

at 210-14; and Ms. Sinkler, a black person, Appeal App. at 215-23.

9 This Court, in other contexts, has noted that the effect of a

zoning ordinance on certain property is at times indirect, with

out suggesting any difficulty with standing. “ [A ] zoning ordi

nance usually has an impact on the nature of the property which

it regulates . . ., [even though] the precise impact on value may,

at the threshold of litigation over validity not yet be known.”

Belle Terre v. Boraas, supra, 416 U.S. at 9-10; Berman v. Parker,

348 U.S. 26, 36 (1954) ; Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S.

365, 397 (1926). The effect of the Penfield zoning ordinance on

certain excluded persons should be similarly treated.

Moreover, it has long been recognized that a black person need

not be physically denied admission to segregated facilities before

he may challenge racial discrimination. See, e.g., Cypress v. New

port News G. & N. Hosp. Ass’n, 375 F.2d 648 (5th Cir. 1967).

9

The standing of these class action plaintiffs who seek to

dismantle the existing dual housing market which excludes

them from living in the Pentield suburb is exactly the stand

ing possessed by school desegregation plaintiffs who seek to

disestablish dual school systems. See, e.g., Rogers v. Paul,

382 U.S. 198, 200 (1965). Indeed, allegations of less tradi

tionally cognizable forms of personal injury have been held

to confer standing adequate to survive a motion to dis

miss. “Aesthetic and environmental well-being, like eco

nomic well-being, are important ingredients of the quality

of life in our society, and the fact that particular environ

mental interests are shared by the many rather than the

few does not make them less deserving o f legal protection

through the judicial process.” Sierra Club v. Morton, 405

U.S. 727, 734 (1972). The allegations of personal injury

in United States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669 (1974), although

“far less direct and perceptible” than in Sierra Club were

held adequate.

With regard to the organizational plaintiffs, this Court

has held that, “ It is clear that an organization whose mem

bers are injured may represent those members in a proceed

ing for judicial review. See, e.g., NAACP v. Rutton, 371

U.S. 415, 428,” Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 739

(1972).10 That associations may enforce rights in behalf

of their members is a well established principle of standing

law in civil rights litigation,11 and this Court has long

10 See also, United States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669, 683-90

(1973) ; Allee v. Medrano, ------ U.S. ----- , 40 L.Ed. 2d 566, 582

n. 13, 588-89 (1974) ; Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. Mc

Grath, 341 U.S. 123, 153-54 (1951) (Justice Frankfurter concur

ring) ; Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 534-35 (1925).

11 See NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449, 458-

60 (1958); Rates v. Little Rock. 361 U.S. 516, 523 n. 9 (1960) ;

Louisiana v. NAACP, 366 U.S. 293, 296 (1961); NAACP v. But

ton, 371 U.S. 415, 428 (1963).

10

recognized that the difficult task of enforcing fair housing

guarantees in particular requires application of realistic

standing requirements.12 Moreover, membership organiza

tions have played a significant role in fair housing enforce

ment in the lower federal courts.13

Housing Council in the Monroe County Area, an asso

ciation of various groups concerned with fair housing in

the Rochester metropolitan area, alleges that, “Housing

Council’s claim in this action arose out of the same trans

actions and occurrences, and raises the same questions of

law and fact, as are already before this Court.” Appeal

App. at 83. Housing Council, in the affidavit of its execu

tive director filed with Motion and Notice of Motion,

specifically avers that the Penfield zoning ordinance has

resulted in injury to an identified member group.14 Simi

12 jBuchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60, 72-73 (1917); Barrows v.

Jackson, 346 U.S. 249, 254-59 (1953); Sullivan v. Little Hunting

Park, 396 U.S. 229, 237 (1969) ; Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life

Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205 (1972).

13 See, e.g., Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency,

395 F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1968); Southern Alameda Span. Sp. Organ.

v. City of Union City, 424 F.2d 291 (9th Cir. 1970) ; Kennedy

Park Homes Assoc, v. City of Lackawanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir.

1970) , cert, denied, 401 U.S. 1010 (1971); Park View Heights

Corp. v. City of Black Jack, 467 F.2d 1208 (8th Cir. 1972) ;

United Farm Workers of Florida Housing Proj., Inc. v. City of

Delray Beach, 493 F.2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974); Sisters of Prov. of

St. Mary Woods v. Citŷ of Evanston, 335 F. Supp. 396 (N.D. 111.

1971) ; Blackshear Residents Organ, v. H.A. of City of Austin,

347 F. Supp. 1138 (W .D. Texas 1971).

14 Upon information and belief, at least one such [charter

member] group, viz. Penfield Better Homes Corporation, is

and has been actively attempting to develop moderate in

come housing in the Town of Penfield, but has been stymied

by its inability to secure the necessary approvals from the

defendants in this action. Appeal App. at 91.

Similarly, the affidavit of Ann McNabb, a director of Penfield

Better Homes, set forth actual terms of an application of Pen-

field Better Homes to build “ a complex of cooperative housing

11

larly, intervenor Rochester Home Builders Association, a

construction industry association, specifically alleges in its

complaint that the Penfield zoning ordinance has injured

its members by prohibiting them from “constructing and

offering for sale or rental, housing to all segments of the

community which require housing, particularly those per

sons of low and moderate income.” Appeal App. at 80-81.

Further, it is alleged that the members of the association,

who have been responsible for constructing 80% of the

private housing units in Penfield in the last 15 years,

have been injured in the sum of $750,000 by reason of

the challenged ordinance and its administration.

In short, the Housing Council and Rochester Home

Builders alleged no less than did the NAACP in NAACP

v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 428; Students Challenging

Regulatory Agency Procedures, the Environmental De

fense Fund, the National Parks and Conservation Asso

ciation, and the Izaak Walton League of America in

United States v. SCRAP, 412 IT.S. at 678-80; or the United

Farm Workers Organizing Committee in Allee v. Medrano,

supra, 40 L.Ed. 2d at 582 n. 13. Thus, the decision of the

Court of Appeals denying them standing is in conflict

with the decisions of this Court and should be reversed.

units which would be sold to persons earning approximately

$5,000.00 to $8,000.00 a year” and facts concerning the refusal to

rezone by Penfield Planning Board and Town Board. Appeal

App. at 311-13, 423-51. The affidavit of Housing Council’s execu

tive director also avers that, “ The large majority of the charter

member groups themselves have membership which is made up

primarily of low and moderate income whites and non-whites and

therefore directly represent the interests of such people.” Appeal

App. at 92.

12

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision of the Second

Circuit should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

C h a r l e s S t e p h e n R a l s t o n

N o r m a n J . C h a c h k i n

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., as Amicus Curiae

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. <*??©*•• 219