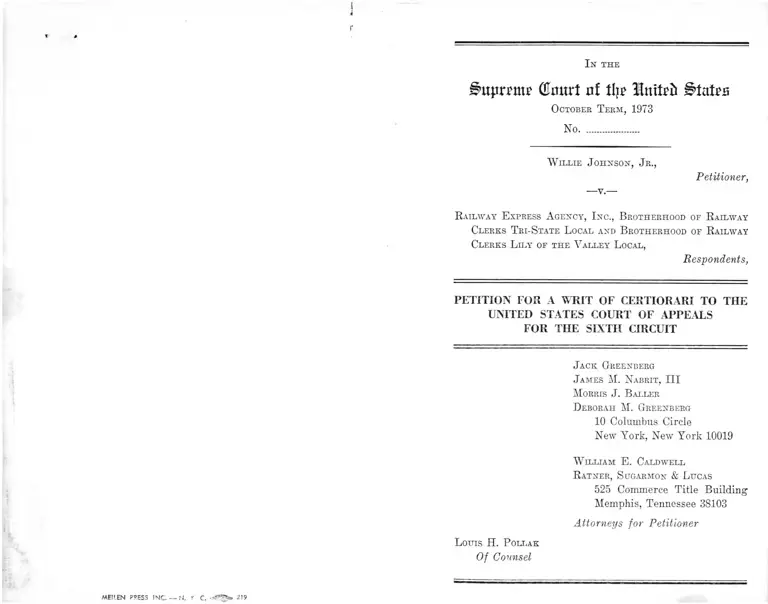

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1974. 6368751a-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cda7cbf3-a0e6-487b-bae8-156631b5ba1e/johnson-v-railway-express-agency-inc-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I'

I

i

MEI'.EN PSESS IMC — N. f C. 219

I n t h e

iatpnmtp (Emtrt nf % InxUb £>tata

October T erm, 1973

No....................

W illie J ohnson, J r.,

-v.—

Petitioner,

R ailway E xpress A gency, I nc., B rotherhood of R ailway

Clerks Tri-State L ocal and Brotherhood of R ailway

Clerks L ily of the Valley L ocal,

Respondents,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Morris J . B aller

Deborah M. Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W illiam E . Caldwell

R atner, S ugarmon & L ucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Petitioner

Louis H. P ollak

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below ............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... 2

Questions Presented........... ........................................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved....................................... 3

'Statement of the Case............................ -................. -.... 5

Reasons for Granting the W rit..................................... 11

I—The Decision Below With Respect to the Tolling

Effect of the Filing of an EEOC Charge Conflicts

With Other Court of Appeals Decisions on an Issue

Having Serious Implications For the Effective

ness of Title VII and Judicial Administration of

Important Federal Statutes.................. -................ 13

XI—The Failure of the District Court to Protect the

Procedural Rights of Petitioner and the Sanction

ing of That Failure by the Court of Appeals Make

This a Compelling Case for the Exercise of This

Court’s Supervisory Authority....... — ................. 15

a. Petitioner’s Section 1981 Claim Should Not Be

Barred by Tenn. Code § 28-301 ......................... 15

b. A Claim Under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 Does Not Re

quire Prior Exhaustion of Administrative

Remedies Under the Railway Labor A ct.......... 18

c. Petitioner’s Title VII Action Should Not Have

Been Precluded by His Failure to Re file His

Complaint Within 30 Days After Dismissal .... 19

11

PAGE

d. Petitioner’s Claims Against the Union Locals

and Claim Against REA on the Issue of Super

visory Training Are Not Barred by the Doc

trine of Res Judicata ......................................... 23

Conclusion.................................................................................

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., ------U.S. , 39

L.Ed.2d 147 (1974) ............................................... 11,15,18

American Pipe and Construction Co. v. Utah, U.S.

----- , 38 L.Ed.2d 713 (1974) ......................................15,20

Austin v. Reynolds Metal Co., 327 F. Supp. 1145 (E.D.

Va. 1971) .......................................................... 21

Balsbaugh v. City of Westland, 458 F.2d 1358 (6th

Cir. 1972) .................................................................... 2^

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co.,

437 F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971) ..................... -......11,13,16

Brady v. Bristol-Myers, Inc., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir.

1972) ........................... - .............................................. 19

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972) 19

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 339 F. Supp.

1108 (N.D. Ala. 1972), affd. per curiam, 476 F.2d

1287 (5th Cir. 1973) ..............................................—- 16

Burnett v. New York Central R. Co., 380 U.S. 424

(1965) .................................................................. --14 ,20

Caldwell v. National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044 (5th

Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 405 U.S. 916 (1972) .............. 19

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals, 421 F.2d 888 (5th Cir.

1970) ............................................. 14

PAGE

iii

Denman v. Shubow, 413 F.2d 258 (1st Cir. 1969) ...... 22, 23

Gates v. Georgia Pacific Corp., 7 CCI1 EPD 9185 (9th

Cir. 1974) ........................................................-......... 19, 20

Glover v. St. Louis & San Francisco R. Co., 393 U.S.

324 (1969) ......................................... ........................... 18

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 350 F. Supp.

529 (S.D. Tex. 1972) .................................... ..............13,14

Hamman v. United States, 399 F.2d 6< 3 (9tli Cir. 1968) 24

Harris v. Walgreen’s Distribution Center, 456 F.2d 5S8

(6th Cir. 1972) ................................................. -.......20,21

Henderson v. First National Bank of Montgomery, 344

F. Supp. 1373 (M.D. Ala. 1972) ................................13,15

Holmberg v. Arinbrecht, 327 U.S. 392 (1945) ....... 20

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ..................... 17

Hutton v. Fisher, 359 F.2d 913 (3rd Cir. 1966) .......... 22

Jenkins v. General Motors Corp., 354 F. Sapp. 1040

(D. Del. 1973) .............................. -.............................. 13

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122

(5th Cir. 1969) ..... -...................................................... 16

Klaprott v. United States, 335 U.S. 601 (1949) .............. 22

Love v. Pullman, 404 U.S. 522 (1972) .... ..................-.... 19

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979

(D.C. Cir. 1973) ........................................11,13,14,17,19

Malone v. North American Rockwell Corp., 457 F.2d

779 (9th Cir. 1972) ..................................................... - 14

McAllister v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 357 U.S. 221

(1958) ................ -...............................................-........ 18

McClendon v. North American Rockwell Corp., 2 CCIi

EPD fl 10,24.3 (C.D. Cal. 1970) 21

IV

PAGE

McDonnell v. Celebrezze, 310 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1962) .... 22

McKnett v. St. Louis & S.F. E. Co., 292 U.S. 230 (1932) 17

McQueen v. E.M.C. Plastics Co., 302 F. Supp. 881 (E.D.

Tex. 1969) ................................................................. 20,21

Newman v. Piggie Park, 390 U.S. 400 (196S) .............. 19

Patapoff v. Vollstedt’s, Inc., 267 F.2d 863 (9th Cir.

1959) ....................................-....................................... 22

Prescod v. Ludwig Industries, 325 F. Supp. 414 (N.D.

111. 1971) .............. 21

Public Service Commission v. Brashear Freight Lines,

312 U.S. 621 (1941) .................................... 24

Eadack v. Norwegian American Line Agency, Inc.,

318 F.2d 538 (2nd Cir. 1963) ............... ............... ........ 22

Eepublic Pictures v. Kappler, 327 U.S. 757 (1946),

aff’g 151 F.2d 543 (8th Cir. 1945) ............................. 17

Eeynolds v. Daily Press Inc., 5 CCH EPD ft 7991 (E.D.

Va. 1972) ...... .......................... ...................... - ........... 13

Eobinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) ........................ — 16

Eooks v. American Brass Co., 263 F.2d 166 (6th Cir.

1959) ........................... .......-----............. -......-............... 22

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir.

1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971) .................. 19

Schiff v. Mead Corp., 3 CCH EPD 8043 (6th Cir.

1970) ............ ..................-_____ _____ ____ ______ 14

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Eailroad Co., .323 U.S.

192 (1944) .................................................................... 18

Sullivan v. Delaware Eiver Port Authority, 407 F.2d

158 (3rd Cir. 1969) ..... ............. ................................... 24

v

PAGE

Town of Marshall v. Carey, 42 F. Supp. 630 (W.D.

Okla. 1941) ..................... ........................................... - 24

United States v. Jacobs, 298 F.2d 469 (4th Cir. 1961) .... 22

U.S. v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir.

1973) ............................................................................ 16

United States v. Wallace & Tiernan Co., 336 U.S. 793

(1949) .................. 24

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970), cert.

denied 400 U.S. 911 (1970) ...................................... 17,19

Wells v. Gainesville-Hall County Economic Opportu

nity Organization, Inc., 5 CCH EPD 8541 (N.D.

Ga." 1973) ....................... -.............................. -........ 14

Young v. International Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

438 F.2d 757 (3d Cir. 1971) ................. - .................... 19

Statutes:

Civil Eights Act of 1866,

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ......... .............. ..... ...... ..............passim

Title VII, Civil Eights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. ....................................passim

Eailway Labor Act,

45 U.S.C. §§ 151 et seq.................. ........... ....3,10,18,19

Tennessee Code

§ 28-106 ..................................................................... 21

§ 28-304 ............................ .................-5,10,12,15,16,17

§28-309 ............................................ 16

§28-310 .............................-.....................................16,17

...... 24

3,10, 22

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 54(b) ........................... .

Rule 60(b) ...........................

Other Authorities:

IB Moore’s Federal Practice If 0.401 (2d Ed. 1965) 24

I n t h e

§>upmnp CEnurt nf thr § ta trs

October T erm, 1973

No....................

W illie J ohnson, J r .,

Petitioner,

R ailway E xpress A gency, I nc., Brotherhood of R ailway

Clerks T ri-State L ocal and B rotherhood of R ailway

Clerks L ily of the Valley L ocal,

Respondents,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment and opinion of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered in this case on

November 27, 1973.

Opinions Below

1. District Court’s order in No. C-71-66 dismissing

claims under 42 U.S.C. <$>1981 and granting summary judg

ment to union locals and partial summary judgment to

REA Express on Title VII claims, June 14, 1971, reported

at 7 CCH EPD f[9108 (la-3a)J

1 This form of citation is to pages of the Appendix.

2

2. District Court’s order in No. C-71-66 dismissing ac

tion without prejudice, February 16, 1972, reported at 7

CCH EPD U9109 (4a-5a).

3. District Court’s opinion and order in No. C-72-183

dismissing refiled complaint, January 25, 1973, reported at

7 CCH EPD 1J9110 (6a-12a).

4. Opinion of Court of Appeals, November 27, 1973, re

ported at 489 F.2d 525 (13a-21a).

5. Order Denying Rehearing, January 15, 1974, reported

at 489 F.2d 525, 530 (22a-26a).

Jurisdiction

The Court of Appeals entered judgment on November

27, 1973. A timely request for rehearing was denied Jan

uary 15, 1974, and this petition for certiorari has been filed

within 90 days of that date. This Court’s jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether the timely filing of a charge of employment

discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission pursuant to Section 706 of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5, tolls the run

ning of the period of limitation applicable to an action

based on the same facts brought under the Civil Rights Act

of 1866, 42 U.S.C. §1981?

2. Whether a person who claims that he has been dis

criminated against in employment on account of his race

3

should be denied a hearing on the merits on any of the

following grounds:

a) As to his cause of action under 42 U.S.C. §1981—

i) That Tennessee’s one-year statute of limita

tions on “civil actions for compensatory or puni

tive damages, or both, brought under the federal

civil rights statutes” bars an employment dis

crimination suit seeking injunctive relief and back

pay;

ii) That failure to exhaust administrative rem

edies under the Railway Labor Act bars a suit;

b) As to his cause of action under Title VII, a suit

dismissed without prejudice for failure to obtain coun

sel must be refiled within 30 days of the order of dis

missal and the order may not be reopened under Rule

60(b), F.R. Civ. P.; and

c) As to his causes of action under either statute,

an interlocutory order granting unopposed motions for

summary judgment in an action subsequently dismissed

without prejudice for failure to obtain counsel has

res judicata effect.

Statutory Provisions Involved

1. United States Code, Title 42, Section 1981 (The Civil

Rights Act of 1866) provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

4

be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

2. United States Code, Title 42, Section 2000e-5(e) (Sec

tion 706(e) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

78 Stat. 259) (prior to its amendment by Pub.L. 92-261)

reads as follows:

If within thirty days after a charge is filed with the

Commission or within thirty days after expiration of

any period of reference under subsection (c) (except

that in either case such period may be extended to not

more than sixty days upon a determination by the

Commission that further efforts to secure voluntary

compliance are warranted), the Commission has been

unable to obtain voluntary compliance with this title,

the Commission shall so notify the person aggrieved

and a civil action may, within thirty days thereafter,

be brought against the respondent named in the charge

(1) by the person claiming to be aggrieved, or (2) if

such charge was filed by a member of the Commission,

by any person whom the charge alleges was aggrieved

by the alleged unlawful employment practice. Upon

application by the complainant and in such circum

stances as the court may deem just, the court may ap

point an attorney for such complainant and may au

thorize the commencement of the action without the

payment of fees, costs, or security. Upon timely ap

plication, the court may, in its discretion, permit the

Attorney General to intervene in such civil action if he

certifies that the case is of general public importance.

Upon request, the court may, in its discretion, stay

further proceedings for not more than sixty days pend

ing the termination of State or local proceedings de

scribed in subsection (b) or the efforts of the Com

mission to obtain voluntary compliance.

5

3. Tennessee Code, Section 28-304, 5 Tennessee Code An

notated 255, provides, in pertinent part:

Personal tort actions—Malpractice of Attorneys—Civil

rights actions—Statutory penalties,—Actions for libel,

for injuries to the person, false imprisonment, mali

cious prosecution, criminal conversation, seduction,

breach of marriage promise, actions and suits against

attorneys for malpractice whether said actions are

grounded or based in contract or tort, civil actions for

compensatory or punitive damages, or both, brought

under federal civil rights statutes, and actions for

statutory penalties shall be commenced within one (1)

year after the cause of action accrued. . . .

Statement o f the Case

Petitioner, Willie Johnson, Jr., is a black man who claims

to have been subjected by respondents to racial discrimina

tion in the terms and conditions of employment. Peti

tioner’s claims have never received a determination of their

merits by a federal court. The procedural vicissitudes of

this litigation, therefore, form the basis of this petition.

Petitioner was employed by respondent Railway Express

Agency Inc. (“REA”) in the spring of 1964 as an express

handler in Memphis, Tennessee. Approximately thirty days

after his hire date, and pursuant to respondent REA’s

direction or referral, petitioner became a member of re

spondent Brotherhood of Railway Clerks Lily of the Valley

Local. More than one year after his initial employment

petitioner became a truck driver with REA.

On May 31,1967, petitioner filed a timely charge with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEOC”)

charging respondent REA with discriminating against its

6

e

black employees with respect to seniority rules and job

assignments. He also charged respondent union locals with

maintaining racially segregated locals, Brotherhood of

Railway Clerks Tri-State Local for whites and Lily of the

Valley Local for blacks. On June 20, 1967 respondent REA

terminated petitioner’s employment, and on September 6,

1967 petitioner amended his EEOC charge to allege that he

had been discharged because of his race.

The EEOC issued a report on December 22, 1967 conclud

ing that respondents had engaged in unlawful racially dis

criminatory employment practices, in that REA directed

black employees to membership in Lily of the Valley Local

and white employees to membership in Tri-State Local, that

membership dues were higher in the black local than in the

white local, that REA maintained racially segregated job

classifications, that respondent REA’s seniority system and

job assignments were discriminatory, that REA discrimi

nated against blacks in the imposition of disciplinary ac

tion, and that petitioner was discriminatorily discharged.

On March 31, 1970 the EEOC issued a decision finding

reasonable cause to believe that respondent had violated

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and on January

10, 1971 petitioner received from the EEOC a notice of his

right to bring suit within 30 days.

Petitioner was unable to obtain private counsel and Dis

trict Judge Bailey Brown entei'ed an order February 12,

1971 appointing an attorney to represent petitioner and

allowing petitioner’s notice of right to sue to be filed as a

complaint on a pauper’s oath.

The court-appointed attorney filed a “Supplemental Com

plaint” alleging violation of Title VII and 42 U.S.C. §§1981

et seq., and invoking the Court’s jurisdiction under 28

U.S.C. §1343(4) and 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5f. The complaint

7

filed March 18, 1971 alleged that respondent REA, in con

junction with respondent union locals, engaged in a policy

and practice of discriminating against black employees with

respect to promotional opportunities and that respondent’s

job assignment and promotion practices served “to maintain

a preexisting pattern of racial discrimination in employ

ment.” Petitioner further alleged that he had been denied

supervisory training and promotion opportunities which

were accorded to white employees, that respondent union

locals did not afford black members (including petitioner)

the same qualitv of representation afforded to white mem

bers, and that petitioner’s discharge was the result of re

spondent REA’s racially discriminatory employment prac

tices. Petitioner prayed for preliminary and permanent

injunctive relief, back pay, costs and attorney’s fees.

Respondents REA and union locals filed their answers on

March 29 and April 6. 1971, respectively. The case was then

scheduled for trial on August 18, 1971.

On April 30 and May 11, 1971, the unions and REA, re

spectively, filed motions to dismiss or in the alternative

for summary judgment.

Petitioner’s court-appointed attorney filed no memoranda

or affidavits on behalf of petitioner in opposition to these

motions.

Judge Brown entered an order June 30, 1971 which,

inter alia, 1) dismissed all claims based on 42 U.S.O. §1981

as barred by Tennessee’s one-year statute of limitations

for actions “for compensatory or punitive damages, or

both, brought under the federal civil rights statutes” ;

2) granted summary judgment to the defendant unions;

and 3) granted REA partial summary judgment on the

issue of improper supervisory training (la-3a.).

8

!

Thereafter, the case having been rescheduled for trial

on February 2, 1972, respondent REA served petitioner

with interrogatories, filed a pre-trial memorandum as

required by local rules of court, and took petitioner’s

deposition. Petitioner’s court-appointed counsel took no

discovery, by interrogatories, deposition, or otherwise, and

filed no pre-trial memorandum.

REA offered Johnson a settlement of one hundred and

fifty dollars which Johnson refused. Petitioner’s counsel

then filed, on January 5, 1972, a motion to be relieved as

attorney of record on the grounds that petitioner’s case

was “questionable,” petitioner had not substantiated money

damages and had not expressed an intention of advancing

the funds necessary for taking depositions, and because

petitioner had refused REA’s settlement offer. The clerk

of the district court advised petitioner by letter dated

January 14, 1972 that the motion to withdraw had been

granted, and informed plaintiff that if he did “not obtain

another counsel to represent [him] within 30 days from this

date, [his] claim will be dismissed without prejudice.”2

Upon receipt of the clerk’s letter, petitioner, in an effort

to obtain representation, contacted the Memphis EEOC

field attorney, the Memphis & Shelby County Legal Services

Association, the Shelbv County Bar Association Legal Re

ferral Service, and two private attorneys. Finally at the

end of the 30 days he returned to the firm of Ratner, Sugar-

mon & Lucas3 and explained his plight to William E. Cald

2 Petitioner received no notice of a hearing on the motion to

withdraw and was afforded no opportunity to state his position.

The court made no finding that petitioner was either unable or

unwilling to proceed pro ae or that petitioner was responsible for

any delay in bringing the case to trial. No order granting the

motion to withdraw was ever entered.

3 Petitioner had first contacted this firm after receipt of his

notice of right to sue. The firm was unable to undertake the repre-

9

well of the firtm. On February 17, 1972 Caldwell wrote a

letter to Judged Brown indicating that he was attempting

to obtain finamcial support for the litigation and request

ing an additional thirty days for petitioner to obtain

counsel. However, the preceding day, February 16, Judge

Brown had erutered an order dismissing petitioner’s case

“without prejudice” (4a-5a).

On Mav 5. 1972, Caldwell again wrote to Judge Brown

indicating than the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund had agreed to pay litigation costs for petitioner,

entering an appearance for petitioner, and requesting that

the order of February 16 be vacated and that the case be

reinstated on The active docket of the court. Judge Brovm

replied on UAy 8, 1972 indicating that the “proper way to

handle this rrratter would be to file a new action since the

old one has long been dismissed.”

Pursuant t'j Judge Brown’s letter, Caldwell, on May 31,

1972, filed a new complaint on petitioner’s behalf (Civil

Action No. 0-72-183), assigned to District Judge Harry

W. Wellford, The new complaint reiterated petitioner’s

original allegations. Respondent REA and union locals

moved for dismissal or for summary judgment on the

grounds of untimeliness and res judicata. The district

court, per Judge Wellford, entered an order of dismissal

on the grounds that 1) Judge Brown’s interlocutory order

of June 14, 1971 granting summary judgment to respon

dent union locals and partial summary judgment to re

spondent REA was a “final disposition” constituting res

judicata. 2) that petitioner’s claims under 42 U.S.C. §§1981

et seq. were I tarred by Tennessee’s one-year statute of limi

tations on “actions for compensatory or punitive damages,

sentation of petitioner because of his inability to defray litigation

expenses and because of the great number of pending Title VII

cases to which the District Court has appointed the firm.

10

or both, brought under the federal civil rights statutes” 4

and because plaintiff did not pursue his administrative

remedies under the Railway Labor Act, and 3) that peti

tioner had “failed to meet the statutory requirements” of

Title VII because he failed to refile his suit within 30

days after Judge Brown’s February 16, 1972 order of dis

missal without prejudice (6a-12a).

The Court of Appeals affirmed the order of dismissal,

disposing of the ease on timeliness grounds (13a-21a).

First, the Court of Appeals held that the Title VII claims

were jurisdictionallv barred because “at a minimum [peti

tioner] had to tile the new case within thirty days from

the date of dismissal without prejudice.” 5 Second, the

court held that petitioner’s claims under 42 I7.S.C. §1981

were time-barred by the running of the statute of limita

tions. In reaching this conclusion as to the Section 1981

claims the Court of Appeals held: a) that the applicable

statute was the one-year limitation contained in Tenn. Code

§28-304; and b) that the running- of the statute on the

Section 1981 claims was not tolled by petitioner’s timely

filing of charg-es with the EEOC.6 The Court of Appeals

did not discuss the issues of res judicata and exhaustion

of remedies under the Railway Labor Act or the failure

of the District Court to grant petitioner relief from the

dismissal without prejudice pursuant to Rule 60(b).

In its opinion denying rehearing, the Court of Appeals

reaffirmed its initial opinion, stating that Tennessee’s at

tempted application of a one-year limitation period to all

4 Tenn. Code §28-304.

5 With regard to Judge Brown’s February 16, 1972 order of dis

missal without prejudice, the Court of Appeals stated:

“We need not determine the propriety of this order because it

was a final order from which no appeal was taken” (15a).

6 If the statute had been so tolled, petitioner’s second complaint,

even if regarded as a new action, would have been timely filed.

11

civil rights actions, regardless of their nature, is not “arbi

trary in a constitutional sense” and the statute does not

create “an explicit racial classification . . . because citizens

of all races are entitled to take advantage of the federal

civil rights statutes” (22a-26a).7

Reasons for Granting llie Writ

1. Assuming for purposes of argument that it was

proper to apply to petitioner’s claim under 42 U.S.C. §1981

the one-year limitation period provided in Tenn. Code

§28-304, even petitioner’s second complaint (with respect

to his Section 19S1 claim) would have been timely had the

court below held that the running of the period had been

tolled by his filing of a charge with the EEOC.8 Its holding

to the contrary squarely conflicts with decisions of the

District of Columbia Circuit and Fifth Circuit Courts of

Appeals9—indeed, the court below- expressly acknowledged

its disagreement with the Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia (25a). Moreover, the decision below is incom

patible with the flexible approach to overlapping remedies

in emplovment discrimination cases—viz., that pursuit of

one does not preclude another—taken by this Court in

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., —— IT.S. ---- -, 39

7 In a footnote, the court stated that it agreed with the district

court on the res judicata question.

8 Petitioner filed his charge with the EEOC on May 31, 1967,

while still employed by REA. The discriminatory acts alleged

therein were continuing in nature, so that none of the one-year

period had run prior to said filing. The first complaint was filed

25 days after termination of EEOC proceedings, that is, after

petitioner received his notice of right to sue; and the second com

plaint was filed 105 days after the first complaint was dismissed

without prejudice. Hence only 130 days of the one-year period

had run when the second complaint was filed.

0 Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979, 994-95

n.30 (D.C. Cir. 1973); Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Con

tracting Co., 437 F.2d 1011, 1017 n.15 (5th Cir. 1971).

(■

12

L.Ed.2d 147 (1974) (pursuit of remedy under arbitration

clause no bar to Title VII action). The holding of the court

below would, if allowed to stand, interfere substantially

with the successful administration of Title VII. Persons

aggrieved by discriminatory employment practices would

be discouraged from invoking the assistance of the EEOC

and possibly achieving voluntary compliance, inasmuch as

they could preserve their claims under Section 1981 only by

filing suit, regardless of whether the EEOC had completed

its investigation and its attempts at conciliation.

2. The ruling of the court below affirming the dismissal

of (a) petitioner’s Section 1981 claims on the further

grounds of failure to exhaust administrative remedies un

der the Railway Labor Act and of untimeliness under a

state statute, Tenn. Code § 28-304, imposing a one-year

limitation period on “civil actions for compensatory or

punitive damages, or both, brought under the federal civil

rights statutes,” (b) petitioner’s Title VII claims on the

grounds of his failure, when unrepresented by counsel, to

refile within thirty days after dismissal without prejudice

(petitioner having been given no notice of this require

ment),10 and (c) petitioner’s claims, under both statutes,

against the unions and. as to failure to train, against REA,

on the ground of res judicata, so far sanctioned a departure

from the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings

as to call for an exercise of this court’s power of super

vision. This court should not allow the great national

values expressed in the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1964

to be frustrated by technical rules which, woodenly applied,

10 In its order denying rehearing, the Court of Appeals makes

an observation which suggests that petitioner was directed to refile

his complaint within thirty days: “ [I]t is difficult to see why

claimant should have more than thirty days to refile after dismissal

without prejudice, particularly when said refiling is ordered by

the Court” (24a). This suggestion that “said refiling [was] ordered

by the Court” is wholly without support in the record.

i

i

13

i

i>

deprive a plaintiff—inadequately represented by court-

appointed counsel or wholly unrepresented because of the

precipitate withdrawal of said counsel—of the opportunity

to have his claims of racial discrimination at the hands of

large corporations and powerful unions decided on the

merits.

I

The D ecision Below With Respect to the Tolling

Effect o f the Filing o f an EEOC Charge Conflicts W ith

Other Court o f Appeals D ecisions on an Issue Having

Serious Im plications For the Effectiveness o f T itle VII

and Judicial Adm inistration o f Important Federal

Statutes.

The Court of Appeals’ rejection of the rule that the

period of limitation applicable to a Section 1981 action

should be tolled for the period during which resolution

through the conciliation procedures of the EEOC is at

tempted (20a-21a, 25a-26a), is in conflict with the decisions

of the only other courts of appeals, those for the District

of Columbia and the Fifth Circuit, which have considered

the question, and with the great majority of district court

decisions.11 The Sixth Circuit’s holding also conflicts in

principle with those decisions in the Fifth, Sixth and Ninth

Circuits and various district courts holding that the period

of limitations for the commencement of proceedings under

Title VII should be tolled for the period during which the * 5

11 Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., supra. 478 F.2d at

994-95 n.30 (D.C. Cir. 1973) ; Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine

Contracting Co., supra, 437 F.2d at 1017 n.16 (5th Cir. 1971) ;

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Corp., 350 F.Supp. 529 (S.D. Tex.

1972) ; Henderson v. First National Bank of Montgomery, 344

F. Supp. 1373 (M.D. Ala. 1972); Reynolds v. Daily Press Inc.,

5 CCH EPD H7991 (B.D. Va. 1972). Contra: Jenkins v. General

Motors Corp., 354 F.Supp. 1040 (D. Del. 1973).

f

14

resolution through arbitration or through the National

Labor Relations Board is attempted.12

The rationale of the decisions holding that the Section

1981 period of limitation should be tolled by the filing of a

charge is that Title VII indicates “a recent Congressional

decision to favor informal methods of settlement and con

ciliation short of litigation in employment cases” and that

“ [p]laintiffs, who often proceed initially without assistance

of counsel and bring their complaint first to EEOC in ac

cord with this legislative policy, should not be penalized

for this action when they later sue for relief in District

Court under both Title VII and § 1981, which overlaps

Title VII.” Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Ine.,

supra, 478 F.2d at 994-95 n.30. Under the contrary rule

adopted by the Sixth Circuit, in order for petitioner to have

preserved both his Title VII and his Section 1981 claims,

he would have to have both filed a charge with EEOC, and,

within one year after his discharge (21 months before

EEOC made its finding of reasonable cause and two and

one-half years before it issued the right-to-sue letter), filed

a lawsuit under Section 1981. Such a requirement, by dis

couraging or rendering futile (by the prior determination

of the Section 1981 action) recourse to the Congressionallv

favored policy of conciliation, would vitiate the administra

tive procedures of the EEOC and be adverse to the interests

of judicial economy.

The view that the Section 1981 limitation period should

he tolled during the pendency of proceedings before the

EEOC comports with the position adopted by this Court

in Burnett v. New York Central R. Co., 380 U.S. 424 (1965)

12 Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals, 421 F.2d 888 (5th Cir. 1970) ;

Schiff v. Mead Corp.'. 3 CCII EPD ([8043 (6th Cir. 1970) ; Malone

v. Forth American Rockwell Corp., 457 F.2d 779 (9th Cir. 1972) ;

Wells v. Gainesville-Hall County Economic Opportunity Organiza

tion, Inc., 5 CCII EPD ([8541‘(N.D. Ga. 1973); Guerra v. Man

chester Terminal Corp., supra.

i

i

15

and reaffirmed in American Pipe and Construction Co., v.

Utah,----- U.S.------ , 38 L.Ed.2d 713 (1974), that where the

policies of ensuring essential fairness to defendants and of

barring a plaintiff “who has slept on his rights” are

satisfied, a statute of limitations should be tolled during

the pendency of a related action the outcome of which could

provide the relief plaintiff seeks. The filing of a charge

with the EEOC puts the respondent on notice of the charg

ing party’s substantive claims. There is neither surprise

nor the dredging up of a stale claim, and duplicate adjudi

cation is avoided. See Henderson v. First National Bank of

Montgomery, supra, 344 F. Supp. at 1377.

Finally, it is a necessary corollary to this Court’s recent

holding in Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, supra, that at

tempts to seek resolution by means other than litigation

should be encouraged not only by rejection of the doctrine

of election of remedies, but also by adoption of the rule

that such attempts toll the applicable statutes of limitations

for commencement of litigation.

II

The Failure o f the District Court to Protect the

Procedural Rights o f Petitioner and the Sanctioning o f

That Failure hv the Court o f Appeals 3Iake This a

Com pelling Case For the Exercise o f This Court’s Super

visory Authority.

a. P etition er’s Section 1981 Claim Should N ot Be

Barred by T enn. Code § 28-304.

Even if the period of limitation on petitioner’s Section

1981 claim were not deemed tolled by the filing of his

E.E.O.C. charge, the first action and the refiled action

should have been held timely under Tennessee’s six-year

statute of limitations for actions on contracts13 or its ten-

year statute for actions not otherwise provided for.14

In both his supplemental complaint filed in No. C-71-66

and his complaint filed in No. C-72-1S3, petitioner sought

injunctive relief from respondent’s discriminatory employ

ment practices and an award of back pay and counsel fees.

In both actions petitioner’s claims under Section 1981 were

dismissed by the application of that portion of Tenn. Code

§ 28-304 which provides a one-year limitation period on

“civil actions for compensatory or punitive damages, or

both, brought under the federal civil rights statutes” (2a,

10a). The Court of Appeals affirmed, ignoring the point

that this action was not one for compensatory or punitive

damages, but an action in equity for injunctive relief and

back pay.15 While Tenn. Code § 28-304 may be applicable

to other types of civil rights actions, it is clearly inapplica

ble by its very terms to the case at bar. The Tennessee

limitation provision that would seem to apply is either its

statute for actions on contracts,16 given that Section 1981

13 Tenn. Code §28-309.

14 Tenn. Code §28-310.

15 Courts of Appeals which have considered the question have

rejected the contention that back pay is “damages” :

“The demand for back pay [in a Title VII action] is not in the

nature of a claim for damages, but rather is an integral part

of the statutory equitable remedy, to be determined through

the exercise of the court’s discretion, and not the jury.-’

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122. 1125 (5th

Cir. 1969). Accord: Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791,

802 (4th Cir.), cert, denied 404 U.S. 1006 (1971) ; see also, TJ.S.

v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354, 380 (8th Cir. 1973).

16 Tenn. Code §28-309 (six years). See Boudreaux v. Baton

Rouge Marine Contracting Co., supra, 437 F.2d at 1017 n.16 (5th

Cir. 1971). But see Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubier Co., 339

F. Supp. 1108 (N.D. Ala. 1972), aff’d per curiam, 476 F.2d 1287

(5th Cir. 1973), in which the court applied a statute of limitations

for actions for “injury to the person or rights of another, not aris-

16 17

protects the right “to make and enforce contracts,” or its

residuary statute for civil actions not otherwise provided

for.17 Under either of these, petitioner’s Section 19S1 claim

was timely filed.

Indeed if, contrary to its plain language, Tenn. Code

§ 28-304 were applicable, it would be violative of both the

supremacy clause of Article VI of the Constitution, in that

it discriminates against rights arising under federal laws,18

and the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, in that it creates an (ineptly camouflaged) explicit

racial classification, drawing a distinction between those

who seek the law’s protection against racial discrimination

in employment and those who seek to vindicate their em

ployment rights on other grounds.19

ing from contract,” but noted that “one may indeed ask whether,

after all, the more appropriate standard should be the doctrine of

laches.” 339 F. Supp. at 1117 n.9.

17 Tenn. Code §28-310 (ten years). See Waters v. Wisconsin Steel

Works of International Harvester Co., 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir.

1970), ccrt. denied. 400 U.S. 911 (1970) ; Macklin v. Specter Freight

Systems, Inc., supra. In Macklin the court noted that it did not

have to decide whether the contract statute of limitations might be

more closely analogous, since the limitation period would have

been the same. 478 F.2d at 994-95 n.30.

18 Republic Pictures v. Kappler, 327 U.S. 757 (1946), aff’g 151

F.2d 543 (8th Cir. 1945); McKnett v. St. Louis & S.F. R.Co.,

292 U.S. 230 (1934).

19 Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969).

i

i

(

18

b. A Claim Under 4 2 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 D oes Not

R equire Prior E xhaustion o f Adm inistrative

R em edies U nder the Railway Labor Act.

The ruling of the District Court that petitioner’s cause

of action under Section 1981 was barred by his failure to

pursue his administrative remedy under the Railway Labor

Act (10a) is contrary to this Court’s holding in Glover v.

St. Louis <& San Francisco R. Co., 393 U.S. 324 (1969).

In Glover, plaintiffs sued the railroad and the union, claim

ing that they had been discriminated against on account

of their race. Rejecting the contention that the complaint

should have been dismissed for failure by plaintiffs to

exhaust their remedies under the Railway Labor Act, this

Court pointed out that “insistence that plaintiffs exhaust

the remedies administered by the union and the railroad

would only serve to prolong the deprivation of rights to

which these petitioners according to their allegations are

justly and legally entitled.” 393 U.S. at 331. See also,

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 323 TI.S. 192

(1944) ; Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra, 39 L.Ecl.

2d at 164, n. 19.

Furthermore, it has been recognized by the Courts of

Appeals for the Third. Fourth, Fifth, Seventh, Eighth

and District of Columbia Circuits that Section 1981 creates

an independent right of action not requiring exhaustion

20 The Court of Appeals found it unnecessary to rule upon this

question. However, since the District Courts holding that peti

tioner’s Section 1981 action should be dismissed for failure to

exhaust his Railway Labor Act. remedies would keep petitioner

out of court even if he should prevail on the tolling issue, we ask

the Court to rule on this question in furtherance of sound judicial

administration. McAllister v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 35/ U.S.

221, 226 (1958).

19

of administrative remedies under other federal statutes.21

Clearly, the District Court was in error in ruling that

petitioner was barred from suing on his Section 1981 claim

for failure to exhaust administrative remedies under the

Railway Labor Act.

c. P etitioner’s T itle VII Action Should Not H ave

B een P recluded by H is Failure to R efile H is

C om plaint W ithin 3 0 Days After D ism issal.

After it permitted petitioner’s court-appointed attorney

to withdraw, the District Court dismissed petitioner’s com

plaint in C-71-66 sua sponte, without a hearing. Its order

of dismissal contained no notice that petitioner must retile

his complaint within thirty days. The subsequent dismissal

by the District Court in No. 72-183 of petitioner’s Title VII

complaint is in conflict with the principles enunciated by

this Court with respect to liberal construction of the pro

cedural requirements of Title VII22 23 and to the Congres

sional policy against discrimination.-3

With respect to the initial tiling of a complaint under

Title VII, “certain equitable principles may operate to

toll the 30 day requirement.” Gates v. Georgia. Pacific

21 Young v. International Telephone & Telegraph Co., 438 F -d

757 (3rd Gir. 1971) ; Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co..

457 F.2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972) ;

Caldwell v. National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044 (5th Cir. 19/1),

cert, denied. 405 U.S. 916 (1972); Sanders Dobbs Houses Inc

431 F 9d 1097 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971),

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International Harvester Co

supra; Brady v. Bristol-Myers, Inc., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir. 197_) ;

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., supra.

22 Love v. Pullman, 404 U.S. 522 (1972).

23 Newman v. Piggie Park, 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

1

i

Corp., 7 CCH EPD H9185 (9th Cir. 1974).24 This Court has

recently affirmed this principle, stating that “the mere fact

that a federal statute providing for substantive liability

also sets a time limitation upon the institution of suit does

not restrict the power of the federal courts to hold that the

statute of limitations is tolled under certain circumstances

not inconsistent with the legislative purpose.” American

Pipe and Construction Co. v. Utah, supra, 38 L.Ed. 2d at

730.25 Where, as in the case at bar, the plaintiff has not

had a clear notice of the time limitation on his right to

sue and has acted with all of the diligence and promptness

which could be expected, it has been held that the limita

tion period does not start running until the plaintiff re

ceives explicit notice.26 That rule should apply here: peti

tioner’s time for refiling his complaint should not have

started until the District Court, knowing that he was un

20

24 Accord: Harris v. Walgreen’s Distribution Center, 456 F.2d

588 (6th Cir. 1972); McQueen v. E.M.C. Plastics Co., 302 F.Supp.

881 (E.D. Tex. 1969).

25 See also Burnett v. New York Central R. Co., supra; Holm-

berg v. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392 (1945).

26 Gates v. Georgia Pacific Corp., supra, 7 CCH EPD j!9185 at

6944. Indeed, the Sixth Circuit reversed a lower court’s failure

to accept a renewed motion for the appointment of counsel made

after the first motion had been denied and more than thirty days

after the receipt of the notice of right to sue, stating:

[Pjursuant to the Congressional purpose when after decision

on the motion for counsel the time remaining is unreasonably

short for securing a lawyer and filing the complaint, the

District Judge’s order granting or denying the motion for

appointment of Counsel should set a reasonable time.

Harris v. Walgreen’s Distribution Center, supra, 456 F.2d at 592.

The only order made by the District Court in C-71-66 relating to

dismissal of the action was that entered March 16, 1972 (4a-5a).

That order set no time for the reeling of petitioner’s complaint.

21

represented by counsel, notified him that he had thirty days

within which to refile.27

Similarly, courts have been liberal in their interpretation

of what constitutes the commencement of a Title VII action,

holding that a motion for appointment of counsel tolls the

running of the thirty-day period.28

The rationale of these cases applies with special vigor

to the instant case. Here petitioner diligently sought to

prosecute his action and obtain counsel. He had no notice

of his duty to reinstitute suit within 30 days. More im

portantly, petitioner would never have run afoul of any

rule requiring him for a second time to meet the thiity-day

filing requirement but for the District Court’s sua sponte

dismissal of his complaint with full knowledge that peti

tioner had at the outset relied on the court to appoint

counsel. The equities here require treating Caldwell’s Feb

ruary 17, 1972 letter requesting an additional thirty days lor

petitioner to obtain counsel as the equivalent of a motion

for the appointment of counsel, satisfying the revived

thirty-day requirement.

After diligently pursuing his case from May 31, 1961,

when he filed his charge with the EEOC, to January 24.

27 Respondents could not be said to be disadvantaged bv this rule

since this was a case of first impression in the Sixth Circuit, and

the Tennessee savings statute, Tenn. Code §28-106 provides a one-

year period for commencement of a new action when a judgment

or decree is rendered against the plaintiff upon any ground not

concluding his right of action.” The only case holding that a Title

VII case must be recommenced within 30 days after dismissal

without prejudice was McClendon v. North American Rockwell

Corp., 2 CCH EPD 1(10,243 (C.D. Cal. 1970), where there was no

such savings statute.

2S Harris v. Walgreen’s Distribution Center, supra; McQueen v.

E M C Plastics Co., supra; Prescod v. Ludwig Industries, 325

f ' Supp. 414 (N.D. 111. 1971) ; Austin v. Reynolds Metal Co., 327

F.Supp. 1145 (E.D. Va. 1971).

r

22

1973, the date of dismissal of his second complaint, peti

tioner found himself, in the words of the District Court,

in the “regrettable” position of having his complaint “dis

missed without a hearing on the merits by reason of the

circumstances alluded to” (12a). The court below never

discussed one of the questions assigned as error, namely

that the District Court abused its discretion by failing to

reopen the first action, C-71-66, pursuant to its powers

under Rule 60(b), F.R. Civ.P. It could have done so either

by treating Caldwell’s letters of February 17 or May 5,

1972 or the refiled complaint as a motion, or by acting on

its own motion.29

This court has established the principle that Rule 60(b)

is to be liberally construed and that any doubt is to be

resolved in favor of an application to set aside a default

judgment or a dismissal for lack of prosecution in order

that a case may be tried on the merits. Klaprott v. United

Stales, 335 U.S. 601 (1949). Numerous courts of appeals

have reversed the denial of relief under Rule 60(b)(1) and

(6) as an abuse of judicial discretion.30

In Denman v. Shuboiv, supra, a case strikingly close on

its facts to the case at bar, plaintiff, appearing pro se in a

civil rights action, overslept because he had taken some

prescribed medication and missed a calendar call, where

upon his case was dismissed without prejudice for lack of

prosecution. In the afternoon of the same day, after calling

the clerk to explain his absence and learning of the dis

missal, he filed a handwritten motion for reconsideration,

29 McDonnell v. Celebrezze. 310 F.2rl 43 (5th Cir. 1962) ; United

States v. Jacobs, 298 F.2d 469 (4th Cir. 1961).

30 Denman v. Shubow, 413 F.2d 258 (1st Cir. 1969) ; Hutton v.

Fisher, 359 F.2d 913, 916 (3rd Cir. 1966); Radack v. Norwegian

American Line Agency, Inc., 318 F.2d 538, 542 (2nd Cir. 1963) ;

flooks v. American Brass Co., 263 F.2d 166 (6th Cir. 1959);

Patapoff v. Vollstedfs, Inc., 267 F.2d 863 (9th Cir. 1959).

I

i

23

which the district court denied. The Court of Appeals for

the First Circuit reversed, stating:

“When the circumstances surrounding plaintiff’s tardi

ness were brought to the district court s attention by

the motion for reconsideration, we think the ends of

justice would have been better served if the district

court had taken the necessary steps to assign the case

for trial on the merits. This pro se plaintiff would

thereby have been assured of his day in Court.” (413

F.2d at 259.)

Similarly, in the instant case the District Court should have

assured petitioner of a trial on the merits by reopening

C-71-66 after Caldwell explained petitioner’s plight and

asked for a thirty-day extension of the time to obtain coun

sel or after he entered his appearance and asked that the

order of dismissal be vacated.

d. P etitioner’s Claims Against the U nion Locals

and Claim A gainst REA on the Issue o f Super

visory T rain ing Are Not Barred by the D octrine

of Res Judicata.

In its order of June 14, 1971, the District Court granted

summary judgment to respondent union locals and partial

summary judgment to respondent REA (2a). Upon the

filing of petitioner’s second complaint, following dismissal

of the first without prejudice, respondents moved to dis

miss on the ground, inter alia, that the interlocutory sum

mary judgment order constituted res judicata. Accepting

this contention, the District Court dismissed all of peti

tioner’s claims against the union locals (9a) and his claim

against REA on the issue of supervisory training (10a).

On appeal, the Court of Appeals did not discuss this

issue, but in its opinion denying rehearing the Court of

r

24

Appeals, in a footnote, affirmed the District Court’s con

clusion (23a).

These rulings are erroneous and should be reversed. It

is hornbook law that res judicata effect can be given only

to final decisions on the merits. See IB Moore’s Federal

Practice fl 0.401 (2d Ed. 1965). The District Court’s sum

mary judgment order dismissing fewer than all of the

defendants was neither final nor appealable, Pule o4(b),

F.E, Civ. P., as the Sixth Circuit itself has recognized.

Balsbaugh v. City of Westland, 458 F.2d 1358 (6th Cir.

1972). Accord: Sullivan v. Delaware River Port Authority,

407 F.2d 58 (3rd Cir. 1969); Tlamman v. United States, 399

F.2d 673 (9th Cir. 1968). It could not he given res judicata

effect, unless by a subsequent order of the court. The only

subsequent order, however, was Judge Brown’s order of

February 16, 1972 dismissing the complaint without preju

dice (4a-5a). Since dismissal without prejudice is not an

adjudication on the merits, such an order cannot have res

judicata effect.31 Public Service Commission v. Brashear

Freight Lines, 312 LT.S. 621 (1941). Even if it were thought,

as respondents have argued below, that the interlocutory

order merged into the subsequent order of dismissal without

prejudice, it does not thereby acquire res judicata finality.32

Petitioner, whose first complaint was dismissed solely lie-

cause he did not have a lawyer, could hardly have been re

quired to appeal a non-prejudicial order on the theory that

an earlier order, unappealable at the time of its entry, had

acquired a quality of finality which even the later order

lacked.

31 As the court below noted in another context, “ [A]n action

dismissed without prejudice leaves the situation the same as if the

suit had never been brought” (17a).

32 United States v. Wallace c& Tiervan Co., 336 U.S. 793 (1949) ;

Town of Marshall v. Carey, 42 F. Supp. 630, 635 ("WiD. Okla.

1941).

i

25

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Morris J . Baller

Deborah M. Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W illiam E. Caldwell

R atner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Petitioner

Louis H. P ollak

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

i

la

District Court’s Order Dism issing Claims Under

4 2 U.S.C. §1981 and Granting Summary Judgment to

Union Locals and Partial Summary Judgment to

REA Express on Title VII Claims

I n the U nited States District Court

F or the W estern D istrict of T ennessee

W estern D ivision

Civil C-71-2

T homas T hornton,

v.

Plaintiff,

REA E xpress, I nc. ; Brotherhood of R ailway Clerks

Tri-State L ocal ; and B rotherhood of R ailway Clerks

L ily of the Valley L ocal,

Defendants,

—and—

Civil C-71-66

W illie J ohnson, J r.,

v.

Plaintiff,

REA E xpress, I nc. ; B rotherhood of Railway Clerks

T ri-State L ocal; and Brotherhood of Railway Clerks

L ily of the Valley" L ocal,

Defendants.

Order W ith Respect to Motions to Dismiss and

Motions for S ummary J udgment

2a

District Court’s Order Dismissing Claims Under, etc.

Upon consideration, and after argument of counsel, it is

hereby Ordered :

1. Insofar as plaintiffs in both cases sue under Civil

Rights statutes other than the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

such claims are dismissed for the reasons that there is no

Federal statute of limitations governing these claims, that

therefore the Tennessee statute of limitations of one year

would apply, and both of these claims were barred by such

statute at the time they were filed.

2. The motions to dismiss in both cases on the ground

that the thirty-day letter filed within the thirty-day period

is not sufficient to satisfy the requirement that a complaint

be filed within thirty days following the issuance of said

letter are overruled. See opinion of Judge Harry W. Well-

ford. Joeanna Beckum v. Tennessee Hotel, (W.D. Tenn.

1971) attached hereto. Cf. Rice v. Chrysler Cory.,

___ F. Supp.------ , 3 FEP Cases 436 (E.D. Mich. 1971).

3. The motion of the defendant Union locals for sum

mary judgment will be granted on the grounds that from

the undisputed facts plaintiffs have no grounds for relief

against said Unions under the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

4. The motions of REA Express, Inc, for summary judg

ment with respect to the claim of dismissal for not giving

plaintiffs supervisory training are granted on the ground

that from the undisputed facts plaintiffs have not shown

any discrimination in this respect.

5. The motions of REA Express, Inc, for summary

judgment with respect to the claim of both plaintiffs of

discriminatory discharge and with respect to plaintiff

3a

District Court’s Order Dismissing Claims Under, etc.

Johnson’s claim of denial of equal promotional opportuni

ties and discrimination in job assignment be and the same

are hereby denied.

E nter this 14th day of June, 1971.

/ s / Bailey Brown

Chief Judge

A True Copy

W. Lloyd J ohnson, Clerk

B y: A. A. Breaux

Deputy Clerk

F i l e d

J un 14 1971

Clerk U.S. District Court

Western Dist. of Tenn.

4a

District Court’s Order Dism issing Action

W ithout Prejudice

l x the U nited States District Court

F or the W estern District of T ennessee

W estern D ivision

Civil N o. C-71-66

W illie J ohnson, J r.,

v.

Plaintiff,

Railway E xpress Agency, I nc., et al.,

Defendants.

Order D ismissing Action W ithout P rejudice

In this cause, this Court heretofore appointed Robert

Rose of the Memphis Bar to represent this plaintiff, as

well as the plaintiff Thomas Thornton in C-71-2, which are

EEOC claims by these plaintiffs against REA Express and

others. Thereafter, after various proceedings in these

matters, counsel for the plaintiffs appeared in court and

stated that he had managed to obtain an offer of settlement

from REA Express, that plaintiff Thornton had agreed

to accept the settlement, but plaintiff Johnson was unwill

ing to do so. Counsel further stated to the Court that in

all frankness, in view’ of the staleness of the claim and

other reasons, he had strongly recommended these settle

ments, but had been unable to persuade plaintiff Johnson

to accept. The cases were set for trial on February 2,

5a

District Court’s Order Dismissing Action

Without Prejudice

1972, and Mr. Rose tiled a motion on or about January 7,

1972 to be relieved as attorney for plaintiff Johnson, which

the Court granted on January 14, 1972. On the latter date,

the Clerk of this Court, under direction of the Court, v7rote

to plaintiff Johnson stating that Mr. Rose had been re

lieved, that the setting for trial on February 2, 1972 would

have to be reset, and that plaintiff Johnson was allowed 30

days from that date to obtain other counsel or his case

would be dismissed without prejudice. Since such 30 days

have passed without plaintiff having obtained such counsel

and so notifying the Clerk as he wras directed, this cause

should be dismissed without prejudice.

It is therefore Ordered and Adjudged that this action be

and the same is hereby dismissed without prejudice.

E nter this 15th day of February, 1972.

/ s / Bailey Brown

Chief Judge

A True Copy.

Attest:

W. Lloyd J ohnson

(Illegible)

F i l e d

F eb 16 1972

Clerk U.S. District Court

Western Dist. of Tenn.

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dism issing Refiled Complaint

I n t h e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

F or t h e W estern D istrict of T en n essee

W estern D ivision

No. C-72-183

W ill ie J o h nso n , J r.,

vs.

Plaintiff,

R ailway E xpress A gency , I nc ., B rotherhood o f R ailway

Clerks T r i-S tate L ocal a n d B rotherhood of R ailway

Clerks L ily' of t h e V alley L ocal,

Defendants.

O r d e r o n D e f e n d a n t M o t io n s f o r J u d g m e n t

This is an action brought by a former employee of Rail

way Express Agency, Inc. (REA) against that carrier and

two local lodges of the BRAC, i.e., the Tri-State Local and

the Lily of the Valley Local (BRAC Locals) alleging viola

tions of the civil rights of the plaintiff under federal statute.

Jurisdiction is asserted pursuant to the provisions of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 TJ.S.C.A., Sec. 2000e,

et seq.), the provisions of other federal statutes protecting

civil rights set forth in 42 U.S.C.A., Sections 1981,1982 and

1988, and the provisions of Title 28 of the United States

Code, Section 1343. The complaint asks for injunctive re

lief, compensatory damages, and the award of costs of the

action together with reasonable attorneys’ fees.

7a

Paragraph VIII of the present complaint states that

“this is the second complaint filed by plaintiff against de

fendants REA and Union Locals concerning the matters

set forth herein and seeking the relief requested herein.”

Said paragraph VIII then goes on to recite the following

facts with respect to the prior complaint:

“On February 12, 1971, this Court entered orders

appointing Robert E. Rose as attorney for plaintiff and

allowing plaintiff’s ‘Notice of Right to Sue’ letter be

filed and treated as a complaint on a pauper’s oath,

which documents were docketed as Civil No. C-71-66.

Subsequently, on March 18,1971, a ‘Supplemental Com

plaint’ was filed on plaintiff’s behalf by his court-

appointed attorney. Defendant REA filed its answer

on March 29, 1971, and defendant Union Locals filed

their answer on April 6, 1971. Thereafter, the case was

set for trial on August 18, 1971. On April 30, 1971, de

fendants Union Locals filed a motion to dismiss or in

the alternative for summary judgment, with supporting

affidavits and memoranda of law. May 11, 1971, defen

dant Union Locals propounded 43 numbered interroga

tories to plaintiff. June 3, 1971, defendant REA filed

a motion to dismiss or in the alternative for summary

judgment, along with supporting affidavits and memo

randa of law. No memoranda or affidavits were ever

filed on behalf of plaintiff in opposition to defendants’

motions.

On June 30, 1971, the Honorable Bailey Brown.

Chief Judge of this Court, entered an order on defen

dants’ motions, which: (1) dismissed plaintiff’s claims

insofar as they were based on statutes other than Title

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dismissing Refiled Complaint

8a

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; (2) granted sum

mary judgment to defendant Union Locals; (3) granted

summary judgment to defendant REA ‘with respect to

the claim of dismissal for not giving plaintiffs super

visory training’; (4) denied defendant REA’s motion

with respect to plaintiff’s charge of discriminatory dis

charge and plaintiff’s claim of denial of equal promo

tion opportunities and discriminatory job assignments;

(5) denied the defendants’ motions to dismiss on the

grounds that filing the ‘Notice of Right to Sue letter

did not constitute the filing of a complaint within the

time allowed. This order was a consolidated ruling in

plaintiff’s case and in No. C-71-2 (Thomas Thornton v.

the same defendants).”

The complaint, with respect to prior history of this

dispute, also sets out in substance that plaintiff’s appointed

counsel. Mr. Rose, failed to take discovery and to prepare

the case for trial, and being dissatisfied with plaintiff s

cause of action and his refusal to settle, was permitted by

Judge Brown to withdraw as counsel (purportedly without

notice to plaintiff) within a few weeks before the date fixed

for trial. Plaintiff further asserts and the record bears out

in the prior action that Judge Brown directed the Court

Clerk to notify plaintiff that if he did not obtain another

counsel within 30 days his claim would be dismissed without

prejudice.

Plaintiff’s present counsel after being contacted (for the

second time) by plaintiff within the prescribed 30 day

period wrote to Judge Brown within a day or two after this

period had elapsed, requesting an additional 30 days for

plaintiff to secure legal representation. The Court had,

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dismissing Refiled Complaint

9a

however, on the 30th day (February 16, 1972) entered an

order dismissing the case without prejudice. This action

has been subsequently filed on May 31, 1972.

At no time did plaintiff Johnson appeal to the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixtli Circuit the order of

Judge Brown dated June 14, 1971, granting the BRAC

Locals summary judgment with respect to the claims upon

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and dismissing

plaintiff Johnson’s claims based upon other federal statutes.

Plaintiff’s Claim Against Defendant Unions

This action clearly involves the same parties and the

same subject matter of dispute as were before Judge

Brown.1 Unless plaintiff can establish a basis for us to act

otherwise, the doctrine of res adjudicata would bar his

bringing this claim again after a final disposition by Judge

Brown. Sopp v. Gehrlin, 236 F. Supp. 823 (W.D. Pa. 1964)

and Burton v. Peartree, 326 F. Supp. 755 (E.D. Pa. 1971),

Vassos v. Societa Trans-Oceania, 272 F.2d 182 (2nd Cir.

1960), cert, denied, Haldane v. Wilhehnina Helen King

Chagnon. 345 F.2d 601 (9th Cir. 1965). We do not subscribe

to any theory that because of alleged improper representa

tion, absent fraud or wrongdoing on defendant’s part, that

a civil litigant should be permitted a “second bite at the

ample” after an adverse ruling in a prior proceeding result

ing in an unappealed final decision of a court assertedly

having proper jurisdiction. Of course, if Judge Brown had

no such jurisdiction of thet parties, neither do we. The mo

tion of defendant unions, either for dismissal, or for sum

mary judgment, is granted on grounds of res adjudicata.

Other grounds are discussed hereinafter.

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dismissing Refiled Complaint

1 The complaints in both causes are substantially similar.

t

10a

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dismissing Refiled Complaint

Plaintiff’s Claim Against REA

1. Plaintiff’s claims of violation of his civil rights under

42 U.S.C. 1981 through 19S8 were properly dismissed and

are here dismissed because barred by the applicable Ten

nessee one year statute of limitations. Ellenburg v. Shep

herd, 406 F.2d 1331 (6th Cir. 196S) and Mulligan v. Schlacli-

ter, 389 F.2d 231 (6th Cir. 1968). In addition, plaintiff’s

cause of action under these sections would be subordinate

to provisions of the Railway Labor Act which governs the

defendant employer (and the defendant unions). See also

Oliphant v. Brotherhood Firemen, et al., 262 F.2d 359 (6th

Cir. 1958) cert, denied, 359 U.S. 935. No effort was made

by plaintiff to protect or assert his rights under the ad

ministrative procedures available under that Act. As to all

claims of plaintiff other than those asserted under Title VII

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, then, the cause of action is

barred under the statute of limitations defense asserted

by all defendants and because plaintiff did not pursue his

administrative remedy under the Railway Labor Act.

2. Judge Brown’s previous order of June 14, 1971,

granted defendant REA’s motion for summary judgment

after a hearing with respect to plaintiff’s claim regarding

lack of supervisory training “on the ground that from the

undisputed facts plaintiff [s] have not shown any discrimi

nation in this respect—” Judge Brown considered the affi

davits and evidence before him and dismissed plaintiff’s

claim in this particular. We hold that Judge Brown’s rul

ing was a final disposition and constitute res adjudicata as

to this aspect of plaintiff’s claim.

3. It is also asserted that plaintiff has failed to comply

with jurisdictional requirements of the Equal Employment

I

i

11a

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dismissing Refiled Complaint

sections of the Civil Rights Act. Judge Brown ruled that

under the then circumstances of the case the “30 day pro

vision” of the act did not bar plaintiff’s claim because he

relied in part upon the Court for advice as to how to tile his

claim of unlawful racial discrimination and simply filed his

notice or letter from Equal Employment Opportunity Com

mission giving him the right to sue within the requisite 30

day period. This Court in Beckum v. Tennessee Hotel,

Cause C-70-417, ruled similarly on the same issue on May

6, 1971. In Beckum, supra, however, wre did not rule as to

whether this procedure met minimal requirement of

F.R.Civ. P. 8a(2). Further complications ensued in this

case after Judge Brown’s initial ruling on the 30 day statu

tory requirement and plaintiff’s suit wras dismissed without

prejudice,2 February 16, 1972. Plaintiff's counsel wrote

Judge Brown again on May 5, 1972,3 requesting reinstate

ment of the cause explaining the financial inability of plain

tiff, and also seeking vacation of the Court’s previous order.

This Judge Brown declined to do since the case “has long

since been dismissed”.4

Considering all the circumstances of the matter, we find

reluctantly that plaintiff has failed to meet statutory re

quirements and that his refiling should have taken place

within 30 days after Judge Brown’s February 16, 1972

order. The Chief Judge extended unusual consideration

to plaintiff that would not have been granted ordinary civil

litigants and we cannot hold under the circumstances that

Title VII Civil Rights Act requirements imposed by Con-

2 It is noted, however, that notice had been issued to plaintiff

that his case would be dismissed if he did not obtain a lawyer by

the appointed time.

3 See Exhibit to complaint.

4 See Exhibit to complaint.

gress may be indefinitely extended by the Courts. Defen

dant REA’s motion to dismiss will therefore be granted.

See Goodman v. City Products Corp., 425 F.2d 702 (6th

Cir. 1970), Brady v. Bristol-Myers, Inc., 332 F. Supp. 995

(E.D. Mo. 1971).

It should also be observed that the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission in this ease was perhaps partially

at fault in the handling of plaintiff’s complaint because of

the long 4 year delay involved in processing the complaint

before issuance of the right to sue notice. It is regrettable

that plaintiff’s complaint should be dismissed without a

hearing on its merits by reason of the circumstances al

luded to in this order.

We, nevertheless, grant all defendants’ motions and dis

miss the complaint filed herein for the reasons stated, but

at the cost, under the circumstances, of REA.

H arry W . W ellford

United States District Judge

Date: 1/24/73

A True Copy.

Attest:

W . L loyd J o h n so n , Clerk

By A. A. B reaux D.C.

F i l e d

J an 25 1973

Clerk, U.S. Dist. Court

Western Dist. of Tenn.

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Dismissing Refiled Complaint

13a

O p in ion o f Court o f A ppeals

No. 73-1306

U nited S tates C ourt of A ppeals

F or t h e S ix t h C ircu it

W illie J o h n so n , J r .,

v.

Plaintiff-Appellant,

R ailway E xpress A gency , I n c ., B rotherhood of R ailway-

Clerks T r i-S tate L ocal a n d B rotherhood of R ailway

Clerks L ily of t h e V alley L ocal,

Defendants-Appellees..

a p p e a l fr o m u n it e d st a t e s d ist r ic t court

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

WESTERN DIVISION

Decided and Filed November 27, 1973.

Before W e ic k , Circuit Judge, O ’S u llivan , Senior Circuit

-Judge, and A l l e n ,* District Judge.

W etck, Circuit Judge. This appeal is from an order o f

the District Court dismissing plaintiff’s complaint whicli

alleged employment discrimination.

Plaintiff-appellant, Willie Johnson, filed timely charges'

with Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)

in 1967 in which he alleged that his employer, Railway Ex

press Agency, Inc. (REA), discriminated against him with

* The Honorable Charles M. Allen, Judge, United States District

Court for the Western District of Kentucky, sitting by designation.

t

14a

Opinion of Court of Appeals

regard to seniority rules and job assignments. Johnson fur

ther asserted that he had been discharged by REA because

of his race (black). Johnson also charged the Brotherhood

of Railway Clerks Tri-State Local and the Lily of the Val

ley Local with maintaining segregated Locals.

On December 22, 1967 EEOC filed a report concluding