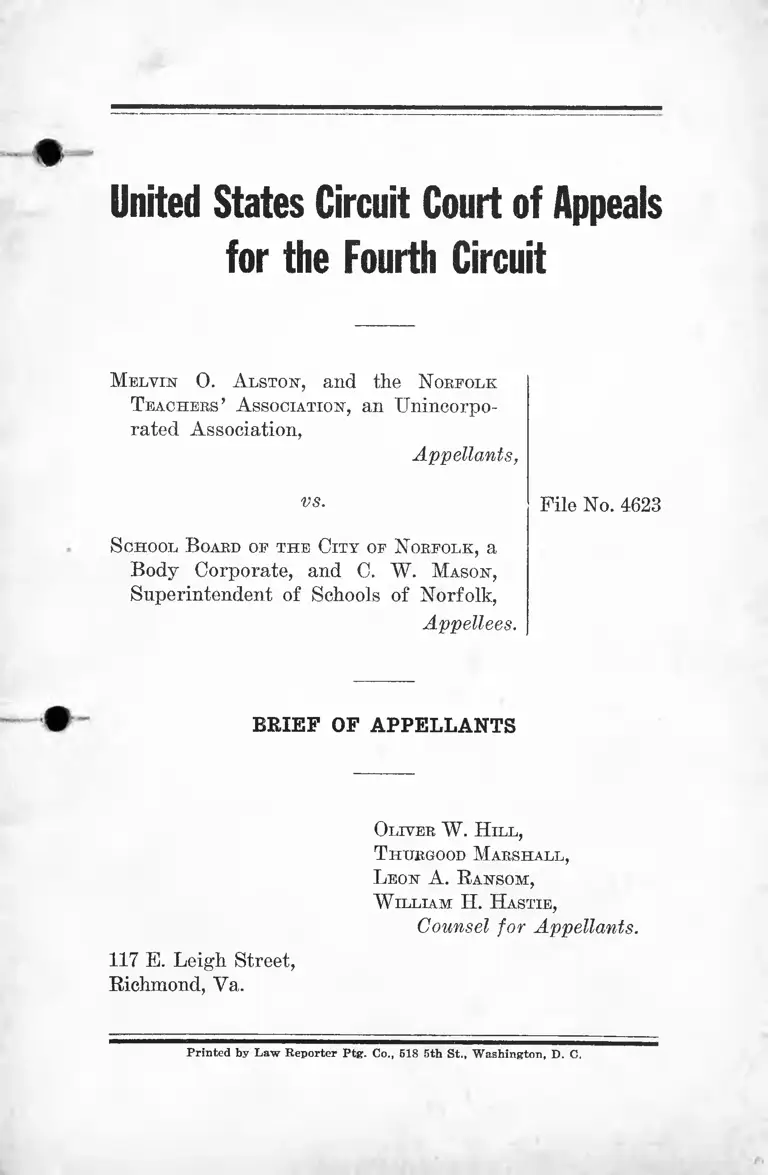

Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 29, 1940

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk Brief of Appellants, 1940. cd3c90a4-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cdd4f881-71ce-4cfc-91cb-a5f172dacd3b/alston-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

United States Circuit Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

M el v in 0 . A lsto n , and the N orfolk

T e a c h e r s ’ A ssociation , an Unincorpo

rated Association,

Appellants,

vs. File No. 4623

S chool B oard of t h e C it y of N orfo lk , a

Body Corporate, and C. W. M ason ,

Superintendent of Schools of Norfolk,

Appellees.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Oliv er W . H il l ,

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

L eo n A . R a n so m ,

W il l ia m H . H a stie ,

Counsel for Appellants.

117 E. Leigh Street,

Richmond, Va.

P rin ted by L aw R eporte r P tg . Co., 518 5 th St., W ashington, D. C.

SUBJECT INDEX

PAGE

Statement of the Case_______ __________ _________ 1

Questions Involved________ _______ ____ ________ 2

Statement of Facts___ __________________________ 3

Pabt Owe : Legislative Background of Appellants ’ Case 5

I. Virginia Has Undertaken the Duty of Providing

Free Public Education as a State Function_____ 5

A. . General Supervision of the Virginia Public

School System is Vested in the State Board

of Education_______ ____________________ 5

B. The Counties and Cities are the Units for Edu

cation in Virginia__________ ___________ ___ 5

C. The Public School System of Virginia is Fi

nanced Jointly by State and Local Public Funds 5

Part Two: Appellants’ Substantive Case__________ 8

I. The Racial Discrimination in Salary Schedules and

in Actual Salaries as Alleged in the Complaint is a

Denial of Constitutional Bight to the Equal Protec

tion of the Laws__________ :_________________ 8

A. The Teachers’ Salary Schedule Being Enforced

by Appellees on its Face Provides and Requires

a Differential in Teachers ’ Salaries Based Solev

on Race or Color _____________________ 10

B. The Salaries Paid to All Teachers and Princi

pals Reveal a Racial Differential Imposed Pur

suant to a General Practice of Unconstitutional

Discrimination__________________________ 13

C. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment Prohibits Such Racial Discrimina

tion Against Appellants as Teachers by Occu

pation and Profession___ i________________ 14

II

PAGE

1. The Fourteenth Amendment Prohibits All

Arbitrary and Unreasonable Classifica

tions by State Agencies____________ -__ 14

2. Discrimination Because of Race or Color is

Clearly Arbitrary and Unreasonable With

in the Meaning of the Fourteenth Amend

ment..._____________________________ 15

D. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment Prohibits Such Discrimination

Against Appellant Alston as a Taxpayer_____ 19

II. The Facts Alleged in Appellant Alston’s Pleading

Do Not Constitute a Waiver of His Right to the

Relief for Which He Prays__________________ 22

Scope of Present Waiver Issue_______________ 22

A. The Contract of Hire is not Affected by the Re

lief Sought____________ 24

B. The Doctrine of Waiver Has Been Held Inap

plicable to Analogous Dealings with Public

Authorities________ ___ __ _______ _____ 26

Rationale of the Decisions ... ...._________ ........ 28

C. Decision on the Waiver Was Erroneously Based

Upon Facts not Before the District Court—.... 32

III. There Is No Merit in the Other Purported De

fenses of Law Raised by the Answer and Not

Relied Upon in the Argument________________ 35

A. An Amount in Controversy to Exceed $3,000

Is Not Required to Confer Jurisdiction in This

Case--------------------- ----------------- ----- -- 35

B. Appellants Have No Full, Adequate and Com

plete Remedy at Law__________ _________ 37

C. The Plea of lies Judicata Is an Affirmative

Defense and Not Now Before the Court___ _ 38

Conclusion 39

I l l

TABLE OF CASES

PAGE

American Union Telegraph Co. v. Bell Telephone Co.,

1 Fed. 698___________________________________ 38

Anderson v. Fuller, 51 Fla. 380, 41 So. 684___________ 21

Black v. Ross, 37 Mo. App. 250____________ _________ 22

Board of Education v. Arnold, 112 111. 11____________ 21

Broom v. Wood, 1 F. Supp. 134, 136_____________ __ 36

Buchannan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60_________ .________ 17

Chaires v. City of Atlanta, 164 G-a. 755,139 S. E. 559___ 17

Chambers v. Davis, 131 Cal. App. 500, 22 P. (2d) 27----- - 27

City of Cleveland v. Clements Bros. Construction Co.,

67 Ohio St. 197, 65 N. E. 885____ __ ____ ________ 28

Claybrook v. City of Owensboro, 16 F. 297___ _______ 20

Davenport v. Cloverport, 72 Fed. 689______ ____ 17-20-36

Di Giovanni v. Camden Ins. Association, 296 IT. S. 64___ 37

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339_____________ __— 12-16

Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission, 271 U. S.

583__________________________________________ 29

Gaines v. Missouri, 305 U. S. 337____ _____________ 17

Gibbs v. Buck, 307 U. S. 66________________________ 34

Glavey v. United States, 182 U. S. 595______________ 27

Glenwood Light and Water Co. v. Mutual Light, Heat

and Power Co., 239 U. S. 121 _________________

Gulf C. & S. F. R. Co. v. Ellis, 165 U. S. 150__________

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 496___________________________________

Hanover Fire Ins. Co. v. Harding, 272 U. S. 494___...... .

Hibbard v. State ex rel Ward, 65 Ohio St. 574, 64 N. E.

109—_______________________________________ _

36

15

36

29

27

Hutton v. Gill, 212 Ind. 164, 8 N. E. (2d) 818-_______ 18-26

International News Service v. Associated Press, 248

U. S. 215___________________________________ 36

Joyner v. Browning, 30 F. Supp. 512______________ 34

Juniata Limestone Co. Ltd. v. Fagley, et ah, 187 Pa. 193,

40 Atl. 977___________________________________ 15

Knapp v. Lake Shore, etc. Ry Co., 197 U. S. 536_______ 38

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268_____________________ _ 17

IV

PAGE

Luke ns v. Nye, 156 Cal. 498,105 Pac. 593___________ 28

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Pe Ry. Co., 235

U. S. 151____________________________________ 17

Miller v. United States, 103 Fed. 413_____________ ___ 27

Mills v. Anne Arundel County Board of Education, et al,

30 Fed. Supp. 245______ _____ ____ _______ 13-25-36

Mills v. Lowndes, et al 26 Fed. Supp. 792____________ 12

Minnesota ex rel Jennison, v. Rogers, 87 Minn. 130, 91

N. W. 438__________________________ ____ ____ 28

M’Intire v. Wood, 7 Cranch. 504___________________ 38

Moses v. Board of Education, 127 Misc. 477, 217 N. Y. S.

265, rev’d, 245 N. Y. 106___________________ ____ 26

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73______________________ 17

O ’Brien v. Moss, 131 Ind. 99, 30 N. E. 894____________ 22

Oehler v. City of St. Paul, 174 Minn. 410, 219 N. W. 760 . 21

Opinion of the Justices, In re, — Mass. —, 22 N. E.

(2d) 49___ ___1_____ ____ _ ____________ _____ 18

Pederson v. Portland, 144 Ore. 437, 24 P. (2d) 1031____ _ 27

People ex rel Fursman, v. Chicago, 278 111., 318, 116

N. E. 158 ___________________________________ 18

People ex rel Rodgers v. Coler, 166 N. Y. 1, 59 N. E. 716.... 28

People ex rel Satterlee v. Board of Police, 75 N. Y. 38__ 27

Petroleum Exploration Inc. v. Public Service Commis

sion, 304 U. S. 209____________________________ 38

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354_________________... 17

Polk v. Glover, 305 IT. S. 5_____ . _________ ___ ______ 34

Puitt v. Commissioner of Gaston County, 94 N. C. 709,

55 Am. Rep. 638______ _________ ______________ 20

Railroad Tax Cases, 13 Fed. 722___________________ 15

Rockwell v. Board of Education, 125 Misc. 136, 210

N. Y. S. 582; rev’d, 214 App. Div. 431, 212 N. Y. S. 281 26

Roper v. McWhorter, 77 Va. 214______________ ___ 20

School District v. Teachers’ Retirement Fund Assn., —

Ore —, 95 P. (2d) 720; 96 P. (2d) 419.-.,..._______ 27-31

Seattle High School, etc. v. Sharpless, 159 Wash. 424, 293

Pac. 994________________________________ ___18

Settle v. Sterling, 1 Idaho, 259 _________________ 27

Simpson v. Geary, et al 204 Fed. 507________________ 15

V

PAGE

Smith v. Bourbon County, 127 U. S. 105-------------------- 38

Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 IT. S. 400------------- 15

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303_______ 15-16-17

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 IT. S. 487--------- .------------- 36

Truax v. Raich, 239 IT. S. 33----------------------------------- 15

Tuttle v. Beem, 144 Ore. 145, 24 P. (2d) 12___________ 21

Union Pacific Railway v. Public Service Corporation,

248 IJ. S. 67.___________ ___ _______ __ __ _____ 30

Whiteley County Board of Education v. Rose, 267 Ky.

283, 102 S. W. (2d) 28______________ _____ ___ 27-29

Wiley v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 58___________________ - 36

Yu Cong Eng v. Trinidad 271 U. S. 500______________ 15

CONSTITUTIONS, STATUTES AND RULES

CONSTITUTIONS CITED

United States Constitution, Amendment Fourteen------- 2

Virginia Constitution, Article IX :

Section 129_______________________ 5-31

131_________________________________ 6

133______________ 6

135 _______ 7

136 ________________________ 7

PRINCIPAL STATUTES CITED

United States Code:

Title 28, Sec. 41 (1) ... ...... . ..................... ....- - ... . 36

Title 28, Sec. 41 (14)________ _-_____ ______ _ 36

Virginia Code:

Sections 611-718-649-653-777______ 6

Section 786 ...____________________ ___ 7-22-31

Section 646 ____ _________ ___________.......— ... 7

Section 664 _______________________ __— 22-23

Section 680 __________ 32

Virginia Acts of 1928, eh. 471, p. 1186 .................... ...... . 5

RULES CITED

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule No. 7 (a)________ 24-34

United States Circuit Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

M e l v in 0 . A l st o n , and the N orfolk

T e a c h e r s ’ A ssociation , an Unincorpo

rated Association,

Appellants,

vs. File No. 4623

S chool B oard op t h e C it y op N orfo lk , a

Body Corporate, a n d C. W. M a son ,

Superintendent of Schools of Norfolk,

Appellees.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from a final judgment of the District

Court of the United States for the Eastern District of

Virginia in a case arising under the Constitution and laws

of the United States, wherein appellants, plaintiffs below,

are seeking a declaratory judgment and a permanent

injunction.

On November 2, 1939, appellants filed a complaint chal

lenging the system, practice and custom of the School Board

of the City of Norfolk, (1) of establishing schedules and

rates of pay for all Negro public school teachers substan

tially lower than those established for white public school

2

teachers similarly situated, and (2) in actually paying to

all Negro teachers, pursuant to such schedules, substan

tially less than is paid to white teachers similarly situated,

all solely because of race or color and in violation of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and

paragraph 14 of Section 41 of Title 28 of the United States

Code. Appellants prayed for a declaratory judgment assert

ing the existence and unconstitutionality of this racial

discrimination and for an injunction restraining its con

tinuance.

On November 21, 1939, the appellees, defendants below,

filed an answer containing four separate defenses. There

after, the Court suggested that inasmuch as defenses in

law were raised in the portions of the answer denominated

“ First Defense”, “ Second Defense” and “ Third Defense” ,

the hearing and disposition of the case might be facilitated

if argument could be made upon these defenses in advance

of trial, treating the said defenses as a motion to dismiss

the bill of complaint for alleged legal insufficiency.

Thereafter, pursuant to the said suggestion of the Court,

the case was argued on February 12, 1940, as upon the ap

pellees’ motion to dismiss the bill of complaint. No testi

mony was taken. On February 29, 1940, the Court entered

a final order dismissing the complaint.

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. Is the racial discrimination in salary schedules and in

actual salaries as alleged in the complaint a denial of con

stitutional right to equal protection of the laws?

2. Has the appellant Alston, by accepting employment

as a matter of law on the facts alleged by his pleading,

waived his right to the relief for which he prays?

3. Is there any substance to the defenses of res judicata,

lack of jurisdiction, and adequacy of remedy at law, pleaded

by the defendants but not relied upon in the argument or

in the decision of the District Court?

3

m

STATEMENT OF FACTS

■ At the hearing on the motion to dismiss the only facts

before the Court were the facts as alleged in the complaint.

Briefly summarized, the basic facts set out in the complaint

are as follows:

Appellant, Melvin O. Alston, is a citizen of the United

States, and a citizen and resident of the State of Virginia.

He is a Negro, a taxpayer of the City of Norfolk and the

State of Virginia, and is a regular teacher in a public high

school maintained and operated by the School Board of the

City of Norfolk. Appellant Alston brings this action (1) as a

teacher by profession and occupation, (2) as a taxpayer, and

(3) as a representative of all other Negro teachers and

principals in the public schools of Norfolk, Virginia, simi

larly situated and affected. (Appendix, p. 41.)

Appellant, Norfolk Teachers’ Association, a voluntary

unincorporated association, is composed of Negro teachers

and principals in the public schools of Norfolk, Virginia,

organized for the mutual improvement and protection of

its members in their profession as teachers and principals

in the public schools of Norfolk, Virginia. (Appendix,

p. 41.)

Appellant Alston and all of the members of the appellant

association and all other Negro teachers and principals in

the public schools of the City of Norfolk are teachers by

profession and are specially trained for their calling.

(Appendix, p. 44.)

The appellee, School Board of the City of Norfolk, is an

administrative department of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia having the direct control and supervision of the public

schools of Norfolk, Virginia, and is charged with the duty

of maintaining an efficient system of public schools includ

ing the employment of teachers and the fixing of teachers’

salaries. Appellee, C. W. Mason, is the administrative and

executive official of the public school system in Norfolk and

is sued in his official capacity. (Appendix, pp. 41, 43.)

4

All public school teachers in Virginia, including appel

lants and all other teachers in Norfolk, are required to hold

teaching certificates in accordance with the rules of cer

tification established by the State Board of Education.

Negro and white teachers and principals alike must meet

the same requirements to receive teachers’ certificates from

the State Board of Education, and upon qualifying do re

ceive identical certificates. (Appendix, pp. 42, 43.)

The appellees over a long period of years have consist

ently pursued and maintained and are now pursuing and

maintaining the policy, custom, and usage of paying Negro

teachers and principals in the public schools of Norfolk less

salary than white teachers and principals possessing the

same professional qualifications, certificates and experience,

exercising the same duties and performing the same serv

ices as Negro teachers and principals. Such discrimination

is being practiced against the appellants and all other

Negro teachers and principals in Norfolk solely because of

their race or color. (Appendix, p. 43.)

Pursuant to the policy, custom and usage, set out above,

the appellees acting as agents and agencies of the Common

wealth of Virginia have established and maintained a salary

schedule used by them to fix the amount of compensation

for teachers and principals in the public schools of Norfolk.

This salary schedule (set out in full in the complaint—

Appendix, p. 46), on its face, provides and requires a dif

ferential in teachers’ salaries based solely on race or color.

The practical application of this salary ■ schedule has

been, is, and will be to pay Negro teachers and principals

of qualifications, certification and experience equal to that

of white teachers and principals, less salary than is paid

white teachers and principals solely because of race or color.

(Appendix, p. 46.)

In order to qualify for his position as teacher, appellant

Alston has satisfied the same requirements as those exacted

of all other teachers, white as well as Negro, qualifying for

similar positions, and he is charged with the same duties

and performs services equivalent to those of all other teach

ers holding these certificates, white as well as Negro. Never

theless, all white male teachers receive salaries much larger

than the salary paid this appellant. White male high school

teachers employed by appellees whose qualifications, cer

tification, duties and services are the same as appellant’s

are paid a minimum annual salary of $1200 while appellant

Alston is paid $921. (Appendix, p. 45.)

As a taxpayer, appellant Alston has contributed to the

fund set out of which all teachers ’ salaries are paid. As a

taxpayer he complains of discrimination against him, solely

on account of race or color in the distribution of the public

fund to which he contributes. (Appendix, pp. 48-49.)

PART ONE

LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND OF APPELLANTS’

CASE

I

Virginia Has Undertaken the Duty of Providing Free

Public Education as a State Function

The Commonwealth of Virginia realizing that free public

education was an essential function of government author

ized the establishment of an adequate educational system

by placing the following mandate in the Constitution of

Virginia:

“ Free schools to be maintained.—The general assembly

shall establish and maintain an efficient system of public

free schools throughout the State. ’ ’ Article IX, Section

129, Virginia Constitution.

Chapter 471 of the Acts of 1928, page 1186, revised, con

solidated, amended and codified the school laws and certain

laws relating to the State Board of Education; the act

6

repealed certain sections and substituted others in their

place; and the new school code is codified as sections 611-718,

inclusive, of the Virginia Code. Section 611 provides that:

“ An efficient system of public schools of a minimum

school term of one hundred and sixty school days, shall

be established and maintained in all of the cities and

counties of the State. The public school system shall

be administered by the following authorities, to-wit:

A State board of education, a superintendent of public

instruction, division superintendent of schools and

county and city school boards.”

A. General Supervision of the Virginia Public School

System Is Vested in the State Board

of Education

Article IX of the Constitution of Virginia established

a State Board of Education and defined its powers and

duties. General supervision is vested in this board and the

members thereof are appointed by the Governor subject

to the approval of the General Assembly.

Section 131 of Article IX of the Constitution provides

for the appointment of a Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion by the Governor subject to confirmation of the General

Assembly.

B. The Counties and Cities Are the Units for Education

in Virginia

Section 133 of Article IX of the Constitution provides

that: “ The supervision of schools in each county and city

shall be vested in a school board, to be composed of trustees

to be selected in the manner for the term and to the number

provided by law.” The local school boards are declared to

be bodies corporate with power to sue and be sued in their

corporate names (Va. Code, Sections 653, 777).

By Section 649 of the Virginia Code each school board

is authorized and required to appoint a division superin-

7

tendent of schools. By Section 786, the city school boards

are required to :

. . establish and maintain therein a general system

of public free schools in accordance with the require

ments of the Constitution and the general educational

policy of the Commonwealth for the accomplishment

of which purpose it shall have the following powers

and duties . . . :

“ Third. To employ teachers from a list or lists of

eligibles to be furnished by the division superintendents

and to dismiss them when delinquent, inefficient or in

anywise unworthy of the position . . . .

‘ ‘ Twelfth. To manage and control the school funds

of the city, to provide for the pay of teachers and of

the Clerk of the board,

C. The Public School System of Virginia is Financed

Jointly by State and Local Public Funds

Section 135 of Article IX of the Virginia Constitution

provides for the distribution of state funds for school pur

poses and Section 136 authorizes each county, city and town

to raise additional funds for local school purposes.

Section 646 of the Virginia Code provides:

“ Of what school fund to consist.—The fund applicable

annually to the establishment, support and maintenance

of public schools in the Commonwealth shall consist of:

“ First. State funds embracing the annual interest

on the literary fund; all appropriations made by the

general assembly for public school purposes; that por

tion of the capitation tax required by the Constitution

to be paid into the State treasury and not returnable

to the localities, and such State taxes as the general

assembly, from time to time, may order to be levied.

“ Second. Local funds embracing such appropriations

as may be made by the board of supervisors or council

for school purposes, or such funds as shall be raised

by levy by the board of supervisors or council, either

8

or both, as authorized by law, and donations or the

income arising therefrom, or any other funds that may

be set apart for local school purposes.”

Realizing that the efficiency of the school system depended

upon an efficient teaching staff which can only be secured

by adequate pay, the General Assembly, by Section 701,

provided:

“ All moneys appropriated by the State for local schools,

unless otherwise specifically provided, shall be used

exclusively for teachers’ salaries.”

PART TWO

APPELLANTS’ SUBSTANTIVE CASE

I

The Racial Discrimination in Salary Schedules and in

Actual Salaries as Alleged in the Complaint Is a Denial

of Constitutional Right to the Equal Protection of

the Laws

The gravamen of this action is clearly set out in the

eleventh and twelfth paragraphs of the complaint which

allege that:

“ Defendants over a long period of years have consist

ently pursued and maintained and are now pursuing

and maintaining the policy, custom, and usage of paying

Negro teachers and principals in the public schools

of Norfolk less salary than white teachers and princi

pals in said public school system possessing the same

professional qualifications, certificates and experience,

exercising the same duties and performing the same

services as Negro teachers and principals. Such dis

crimination is being practiced against the plaintiffs

and all other Negro teachers and principals in Norfolk,

Virginia, and is based solely upon their race or color.

(Italics added.)

9

%

“ The plaintiff Alston and all of the members of the

plaintiff association and all other Negro teachers and

principals in public schools in the City of Norfolk are

teachers by profession and are specially trained for

their calling. By rules, regulations, practice, usage

and custom of the Commonwealth acting by and through

the defendants as its agents and agencies, the plaintiff

Alston and all of the members of the plaintiff associa

tion and all other Negro teachers and principals in the

City of Norfolk are being denied the equal protection

of the laws in that solely by reason of their race and

color they are being denied compensation from public

funds for their services as teachers equal to the compen

sation provided from public funds for and being pai d

to white teachers with equal qualifications and experi

ence for equivalent services pursuant to rules, regu

lations, custom and practice of the Commonwealth

acting by and through its agents and agencies, the

School Board of the City of Norfolk and the Superin

tendent of Schools of Norfolk, Virginia.” (Appendix,

pp. 43-44.)

The District Judge, in his opinion, recognized the prin

ciple that these allegations, accepted as true on a motion to

dismiss, established unconstitutional discrimination against

Negroes. It is readily apparent from the opinion that he

had no doubt that the practice, custom, and usage of pay

ing Negro teachers and principals less salary than white

teachers and principals of the same professional qualifi

cations, certification, and experience solely because of race

or color violates the Fourteenth Amendment. We quote:

. The authorities are clear, I think however, that

there can be no discrimination in a case of this kind,

if such discrimination is based on race or color alone.

Under our constitution, particularly the fourteenth

amendment, all citizens stand upon equal footing before

the law and are entitled to equal benefits and privileges

where state action is involved; or, to state the propo

sition another way, a state can not, through its consti

tution, statutes, or rules and regulations, or through

one of its administrative bodies, arbitrarily discrimi-

10

nate against persons within its jurisdiction. In the

words of the fourteenth amendment, a state cannot

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the law. That principle is firmly estab

lished, and, if and when a case of discrimination based

on race or color is presented, the person discriminated

against will be granted appropriate relief.

‘ ‘ The view that I take of the plaintiff’s case, with some

hesitation I will admit, does not render it necessary

for the Court to pass on the unconstitutional discrimi

nation charged in the complaint to have been practiced

against the plaintiff, other than to observe that the

complaint charges in clear and explicit language that

the discrimination in compensation is based on race or

color alone.” (Italics added.) (Appendix pp. 60-61.)

This cause of action is based upon a system of racial dis

crimination set up by administrative rulings of the appellees

acting as administrative agencies of the Commonwealth of

Virginia. It involves the question of the distribution of

public funds by state agencies pursuant to a system which

discriminates against Negroes solely because of race or

color.

The discriminatory practice, usage and custom of the

appellees consist of: (1) a salary schedule which on its

face provides and requires a differential in teachers’ sal

aries based solely on race or color, and, (2) the practice

of fixing teachers ’ salaries pursuant to this schedule in such

a manner as to provide less salary for Negro teachers and

principals than for white teachers and principals with equal

qualifications and experience solely because of race or color.

A. The Teachers’ Salary Schedule Being Enforced by Ap-

lees on Its Face Provides and Requires a Differential in

Teachers’ Salaries Based Solely on Race or Color

Pursuant to the policy, custom and usage set out above

the appellees acting as agents and agencies of the Common

wealth of Virginia have established and maintained a salary

11

schedule used by them to fix the amount of compensation

for teachers and principals in the public schools of Norfolk.

This salary schedule provides as follows:

Negro—

Elementary

Salaries now

being paid

teachers new

to the system

Maximum salary

being paid

(affecting only

those in system

before increment

plan was

discontinued)

Normal Certificate $ 597.50 $ 960.10

Degree

High School

611.00 960.00

Women 699.00 1,105.20

Men

White

Elementary

784.50 1,235.00

Normal Certificate 850.00 1,425.00

Degree

High School

937.00 1,425.00

Women 970.00 1,900.00

Men 1,200.00

(Appendix,

2,185.00

p. 46.)

This salary schedule is a basic factor of the discrimina

tory system. The evil in the schedule is two-fold: first, it

provides a lower minimum for Negro teachers new to the

system than for white teachers with equal professional

qualifications and new to the system; and, second, it pro

vides a higher maximum for white teachers than for Negro

teachers. Under this schedule appellant Alston and other

Negro teachers can never receive more than the maximum

of $1235 for Negroes which is but $35 more than the mini

mum for white male high school teachers, and $950 less

than the maximum for white male high school teachers.

Under this schedule a Negro teacher must start at a

lower salary than a white teacher and no matter how long

he teaches or how well, how many degrees he obtains at

college or how proficient he may become he can never re

ceive as much as the maximum for white teachers solely

12

because of Ms race or color. TMs system of racial dis

crimination destroys the opportunity of Negro teachers

to bargain freely for their salaries. Their freedom of con

tract is limited to the figures on the schedule which are

lower than the corresponding figures for white teachers.

Two decisions of similar cases in this circuit clearly rec

ognize that such discrimination as this is a denial of con

stitutional rights. In the first case, Mills v. Lowndes, et al.,

26 Fed. Supp. 792 (D. C. Md. 1939), a Negro public school

teacher in Maryland challenged the constitutionality of a

state statute which provided a higher minimum salary for

white teachers than for colored teachers. The Court de

clared that this type of schedule was unconstitutional:

“ . . . The plaintiff is a qualified school teacher and

has the civil right as such to pursue his occupation

without discriminatory legislation on account of his

race or color. While the State may freely select its

employees and determine their compensation it would,

in my opinion, be clearly unconstitutional for a state

to pass legislation which imposed discriminatory bur

dens on the colored race with respect to their qualifi

cations for office or prescribe a rate of pay less than

that for other classes solely on account of race or

color . . . ” (26 Fed. Supp. at 801.)

In the Mills case, supra, the schedule provided for mini

mum salaries only—in the instant case the discrimination

is not only as to minimum salaries but maximum salaries

as well. In the Mills case there was a statutory salary

schedule—in the instant case there is a salary schedule

established by administrative ruling of an administrative

agency of the state.

There can be no question but that the prohibitions of the

Fourteenth Amendment apply with full vigour to the acts

of such agencies. Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339 (1879).

13

H B. The Salaries Paid to all Teachers and Principals Reveal

a Racial Differential Imposed Pursuant to a General

Practice of Unconstitutional Discrimination

Using the salary schedule set out above as a basis, the

appellees fix the salaries of the Negro teachers in the public

schools of Norfolk who are new to the system at a lower

rate than white teachers new to the system who have identi

cal state teachers’ certificates, years of experience, exer

cising the same duties and performing essentially the same

services (Appendix, p. 46). Similarly Negro teachers in

intermediary salary status are paid less than white teachers

with equivalent intermediate status (Appendix, p. 46). The

discrimination in maximum salaries had already been set

forth. It is further alleged in the complaint that the dis

crimination in salaries is based solely on race or color (Ap

pendix, p. 47). White male high school teachers employed

by appellees whose qualifications, certification, duties and

services are the same as appellants’ are paid a minimum

annual salary of $1200 while appellant Alston is paid $921.

The second Mills case, Mills v. Anne Arundel County

Board of Education, et al., 30 Fed. Supp. 245 (D. C. Md.

1939), involved the policy, custom and usage of paying

Negro teachers in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, less

salary than white teachers solely because of race or color.

In granting a declaratory judgment and an injunction to the

Negro teacher, District Judge Chestnut stated:

“ . . . . As already stated, the controlling issue of fact

is whether there has been unlawful discrimination by

the defendants in determining the salaries of white and

colored teachers in Anne Arundel County solely on

account of race or color, and my finding from the testi

mony is that this question must be answered in the

affirmative, and the conclusion of law is that the plaintiff

is therefore entitled to an injunction against the contin

uance of this unlawful discrimination. (Italics added.)

(30 Fed. Supp. at 252.)

14

C. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment Prohibits Such Racial Discrimination Against Apel-

lants as Teachers by Occupation' and Profession

Virginia has no tenure of office statute covering teachers

and there are no civil service provisions applicable to them.

The question in this case is not of the right to teach but of

the right of Negroes, teachers by training and occupation

not to be discriminated against because of color in the fixing

of salaries for public employment by the appellees.

In the employment of teachers and the fixing of salaries

the appellees are acting as an administrative department

of the Commonwealth of Virginia distributing public funds

and not as a private employer distributing his own funds.

A significant difference between the individual employer

and the state at once suggests itself. The federal Constitu

tion does not require individuals to accord equal treatment

to all. It does not forbid individuals to discriminate against

individuals. It does, however, expressly declare that no

state shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the

equal protection of the laws. Thus state action is prohibited

by the federal Constitution where individual action is not

prohibited.

(1 ) T h e F o u r t e e n t h A m e n d m e n t P r o h ib it s all A rbitrary

and U nreasonable Cla ssific a tio n s by S tate A g en cies

While a state is permitted to make reasonable classifica

tions without doing violence to the equal protection of the

laws, such classification must be based upon some real and

substantial distinction, bearing a reasonable and just rela

tion to the things in respect to which such classification is

imposed; and classification cannot be arbitrarily made with

out any substantial basis.

This protection of the Fourteenth Amendment has been

applied in numerous types of cases in which the courts con

cluded that unreasonable classification and resultant dis

crimination were held to be arbitrary and unlawful.

15

%

Railroad Tax Cases, 13 Fed. 722 (1882);

Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400 (1910);

Gulf C. and S. F. R. Co. v. Ellis, 165 IT. S. 150 (1896);

Juniata Limestone, Ltd. v. Fagley, et al., 187 Pa. 193,

40 Atl. 977, (1898) ;

Yu Gong Eng v. Trinidad, 271 U. S. 500 (1926).

This doctrine has been invoked to prohibit unlawful dis

crimination in employment. An Arizona statute which pro

vided that all employers of more than five employees must

employ not less than eighty percent qualified electors or

native-born citizens of the United States was held unconsti

tutional in a suit by an alien.

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915).

“ The right to contract for and retain employment in a

given occupation or calling is not a right secured by

the Constitution of the United States, nor by any

Constitution. It is primarily a natural right, and it

is only when a state law regulating such employment

discriminates arbitrarily against the equal right of

some class of citizens of the United States, or some

class of persons within its jurisdiction, as, for example,

on account of race or color, that the civil rights of such

persons are invaded, and the protection of the federal

Constitution can he invoked to protect the individual

in his employment or calling.”

Simpson v. Geary, et al., (D. C. Ariz. 1913) 204 Fed.

507, 512.

(2 ) D isc r im in a t io n B ecause of R ace or C olor I s Clearly

A rbitrary and U nreasonable W it h in t h e M ea n in g of

t h e F o u r t e e n t h A m e n d m e n t

It is clear that, under the Fourteenth Amendment, officers

of a state cannot discriminate against Negro citizens solely

because of race or color. The purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment has been clearly set out by Mr. Justice Strong

of the United States Supreme Court in the case of Strauder

v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879):

16

“ . . . What is this (amendment) but declaring that

the law in the States shall be the same for the black

as for the white; that all persons, whether colored or

white, shall stand equal before the laws of the States

and, in regard to the colored race, for whose protection

the Amendment was primarily designed, that no dis

crimination shall be made against them by law because

of their color? The words of the Amendment, it is true,

are prohibitory, but they contain a necessary implica

tion of a positive immunity, a right, most valuable to

the colored race—the right to exemption from un

friendly legislation against them distinctively as col

ored; . . . ” Strauder v. West Virginia (supra, at

p. 307).

The Fourteenth Amendment is in general terms and does

not enumerate the rights it protects:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment makes no attempt to

enumerate the rights it is designed to protect. It speaks

in general terms, and those are as comprehensive as

possible. Its language is prohibitory; but every pro

hibition implies the existence of rights and immunities,

prominent among which is an immunity from inequality

of legal protection, either of life, liberty, or property.

Any State action that denies this immunity to a colored

man is in conflict with the Constitution.”

Strauder v. West Virginia (supra, at p. 310.)

The United States Supreme Court in the case of Ex parte

Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 344 (1879), declared:

“ One great purpose of the Amendment was to raise

the colored race from that condition of inferiority and

servitude in which most of them had previously stood

into perfect equality of civil rights with all other per

sons within the jurisdiction of all the States. They

were intended to take away all possibility of oppression

by law because of race or color . . .”

In consistent application of this interpretation to a great

variety of situations the courts have condemned all forms

of state action which impose discriminatory treatment upon

Negroes because of their race or color.

17

Exclusion from petit jury—Strauder v. West Virginia,

supra.

Exclusion from grand jury—Pierre v. Louisiana, 306

IT. S. 354 (1939).

Exclusion from voting at party primary—Nixon v. Con

don, 286 U. S. 73 (1932).

Discrimination in registration privileges—Lane v. Wil

son, 307 U. 8. 268 (1939).

Ordinance restricting ownership and occupancy of

property—Buchannan v. Warley, 245 IT. S. 60 (1917).

Ordinance restricting pursuit of vocation—Chaires v.

City of Atlanta, 164 Ga. 755,139 8. E. 559 (1927).

Refusal of pullman accommodations—McCabe v. At.

chison, Topeka & Sante Fe By. Co., 235 U. S. 151

(1914).

Discrimination in distribution of public school fund—

Davenport v. Cloverport, 72 Fed. 689 (D. C. Ky.

1896).

Discrimination in public school facilities—Gaines v.

Missouri, 305 IJ. S. 337 (1938).

%

It is clear from the cases set out above that: (1) state

agencies, such as appellees, cannot make classifications on

an arbitrary or unreasonable basis, and (2) race or color

alone cannot be used as a basis for discrimination against

Negroes. There is, therefore, complete legal justification

for the decisions in the two Mills cases, supra, and the con

clusion of the District Judge on this point in this instant

case that: ‘ ‘. . . there can be no discrimination in a case of

this kind, if such discrimination is based on race or color

alone” . (Appendix, p. 60.)

As a general proposition, local school boards, in employ

ing teachers, may make reasonable classifications which can

be justified as having a direct connection with the proper

administration of the school system. There is even some

authority that local school boards have the power to require

all new teachers to take an oath that they are not members

18

of a teachers’ union. (Seattle High School, etc. v. Sharpless,

159 Wash. 424, 293 Pac. 994 (1930), and People ex rel.

Fursman v. Chicago, 278 111. 318, 116 N. E. 158 (1917)).

However, this power of local school boards must be con

sidered in connection with the concurring opinion of two

Justices in the Fursman case, supra, that: . This power

does not, however, include the power to adopt any kind of

an arbitrary rule for the employment of teachers it chooses

to adopt; for a rule can easily be imagined the adoption of

which would be unreasonable, contrary to public policy,

and on the face of it not calculated to promote the best

interests and welfare of the schools. In our opinion, courts

would have the power, in the interest of the public good, to

prohibit the enforcement of such an arbitrary rule . . .” .

The correctness of the limitation thus declared by the con

curring justices is well illustrated by two other cases in

which discriminations against public employees upon the

basis of unreasonable classifications have been held to be

invalid.

In In re Opinion of the Justices,—Mass.-—, 22 N. E. (2d)

49 (1939), the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts

held that discrimination against married women in the pub

lic service, solely because of their marital status, is invalid

as a denial of equal protection of the laws guaranteed by

the State Constitution:

‘ ‘ . . . the General Court cannot constitutionally enact a

law, even with respect to employment, in the public

service, that arbitrarily discriminates against any class

of citizens by excluding it from such service. This con

clusion results from . . . the guarantees in Articles 1,

6 and 7 of the Declaration of Rights ‘for equal protec

tion of equal laws without discrimination or favor based

upon unreasonable distinctions.’ ” (22 N. E. (2d)

at 58).

In Hutton v. Gill, 212 Ind. 164, 8 N. E. (2d) 818 (1937), a

salary differential between married and unmarried teachers

was held to be an unreasonable classification, and thus to

19

%

be void. The situation in that case was closely analagous

to that in the case at bar, and the language of the Indiana

Court is directly applicable here:

“ So, if the legislative intent, . . . was to authorize the

School Board to classify its teachers, it necessarily fol

lows that such classification must be reasonable, nat

ural, and based upon substantial difference germane to

the subject . . . The compensation of appellee was

fixed by the board, partly at least upon the fact that she

was married. This, in our opinion, was unlawful and

arbitrary, and formed no rational basis of classifica

tion. It had no reasonable relation to the work assigned

to her, as the fact that appellant was a married woman

did not affect her ability to impart knowledge or per

form her duties in the school room. It is conceded that

her marriage status has no such effect and, if not, there

could be no just or reasonable basis for the school board

classifying her as far as compensation is concerned, in

a different and lower class than an unmarried female

teacher having like qualifications and doing like work. ’ ’

(8 N. E. (2d) at 820.)

A fortiori, discrimination based on race or color is arbi

trary and unreasonable, and therefore is unconstitutional.

D. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment Prohibits Such Discrimination Against Appellant

Alston as a Taxpayer

In addition to his right as a citizen of the United States

and a teacher by occupation and profession to maintain this

action, appellant Alston also bases his right to the relief

prayed for upon the fact that he is a taxpayer. As a tax

payer he is required to contribute to the public tax fund,

a portion of which is used for public schools. As a teacher

in the public schools he has a right to share in this fund

without discrimination because of his race or color. Any

illegal action on the part of the appellees in the distribution

of this fund directly affects appellant Alston and is an

injury peculiar to him as a taxpayer who is also a teacher.

20

The right of a citizen, resident and taxpayer to attack

the unconstitutional distribution of public funds has been

clearly established. In the case of Claybrook v. City of

Owensboro, 16 F. 297 (D. C. Ky., 1883), the General As

sembly of Kentucky passed an act authorizing a municipal

corporation to levy taxes for school purposes and to dis

tribute taxes from white people to the white schools, and

taxes from the colored people to colored schools. Residents

of the City of Owensboro filed a petition for an injunction

in the District Court restraining the distribution of these

taxes on this basis. The Court in granting the injunction

prayed for stated that:

“ The equal protection of the laws guaranteed by this

Amendment means and can only mean that the laws of

the states must be equal in their benefit as well as equal

in their burdens, and that less would not be ‘ equal pro

tection of the laws.’ This does not mean absolute equal

ity in distributing the benefits of taxation. This is im

practicable; but it does mean the distribution of the

benefits upon some fair and equal classification or

basis.” (16 Fed. at 302)

See also: Davenport v. Cloverport, 72 Fed. 689, (D. C.

Ky. 1896); Puitt v. Commissioner of Gaston County, 94 N. C.

709, 55 Am. R. 638 (1886).

The law sustaining this case is well established and was

recognized in Virginia in 1883 by the case of Roper v. Mc

Whorter, 77 Va. 214 (1883) :

” . . . In this country the right of property-holders or

taxable inhabitants to resort to equity to restrain mu

nicipal corporations and their officers, and quasi cor

porations and their officers from transcending their

lawful powers or violating their legal duties in any

way which will injuriously affect the taxpayers, such

as making an unauthorized appropriation of the cor

porate funds, or an illegal disposition of the corpo

rate property, . . . has been affirmed or recognized in

numerous cases in many of the states. It is the prevail

ing doctrine on the subject.” (77 Va. at p. 217.)

%

21

This rule of law as applied in Virginia is the prevailing

doctrine today as to public schools:

“ Except as relief may be denied where the act com

plained of does not affect the taxpayer with an injury

peculiar to himself, it has been held that the authorities

of a school district may be enjoined at the suit of tax

payers from making any illegal or unauthorized appro

priation, use, or expenditure of the district funds, as

where there is a threatened use or expenditure of funds

for an illegal or unauthorized purpose, or a threatened

diversion of funds.” 56 C. J., Schools and School Dis

tricts, sec. 906, page 764.

In the case of Oehler v. City of St. Paul, 174 Minn. 410, 219

N. W. 760 (1928), the court upheld an injunction restraining

the appointment to a civil service position without meeting

civil service requirements, stating:

“ It is well settled that a taxpayer may, when the situ

ation warrants, maintain an action to restrain unlawful

disbursement of public moneys . . . as well as to restrain

illegal action on the part of public officials.” (219 N. W.

at p. 763.)

In the case of Tuttle v. Beem, 144 Ore. 145, 24 P. (2d)

12 (1933), taxpayers were granted an injunction to enjoin

the local school district from unauthorized use of public

funds for digging a well.

In the case of Anderson v. Fuller, 51 Fla. 380, 41 So. 684

(1906), it was held that taxpayers may sue to enjoin public

officers from paying money under an illegal contract. In

this case the contract was let without competitive bidding.

In Board of Education v. Arnold, 112 111. 11 (1884), an

action by a taxpayer, an injunction was granted preventing

the payment of a teacher who had no certificate from the

county superintendent.

And a taxpayer was held entitled to an injunction against

a school district to prevent the employment of a teacher

whose employment was voted down by a majority of the

22

district. O’Brien s. Moss, 131 Ind. 99, 30 N. E. 894, (1892).

A taxpayer was held entitled to maintain an injunction

to restrain the payment of a warrant for a school teacher’s

salary which was illegal. Black v. Ross, 37 Mo. App. 250

(1889). The court said:

“ If the defendants, as directors of the school dis

trict, were about to make an unlawful and unauthorized

disposition of the public school fund, an injunction was

the only adequate remedy afforded the individual tax

payer, to prevent the illegal diversion.”

II

The Facts Alleged in Appellant Alston’s Pleading Do Not

Constitute a Waiver of His Right to the Relief

for Which He Prays

In considering the issue of waiver it is and must be as

sumed that racial discrimination in fixing the salaries of

public school teachers violates the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment. But admitting such un

constitutionality the District Court concluded that appellant

Alston had waived his right to complain of the unconstitu

tional discrimination.

Scope of Present Waiver Issue

Paragraph 10 of the complaint (Appendix, p. 43) alleges

that appellees are under a statutory duty to employ teachers

and to provide for the payment of their salaries, citing,

inter alia, Section 786 of the Virginia School Laws which

provides in part that,

“ The City school board of every city shall . . . have

the following powers and duties. . . . Third. To em

ploy teachers . . . Twelfth. To . . . provide for the

pay of teachers . . .”

It is further provided in Section 664 that

23

“ Written contracts shall be made by the school board

with all public school teachers before they enter upon

their duties, in a form to be prescribed by the Super

intendent of Public Instruction.’.’

Paragraph 15 of the complaint (Appendix, p. 45) alleges

that appellant Alston

“ is being paid by the defendants for his services this

school year as a regular male high school teacher as

aforesaid an annual salary of $921.”

Thus, from the complaint and the above quoted language

of applicable Virginia statutes it seems a proper conclusion

that appellant Alston is employed during the current year

pursuant to a contract of hire and at an annual salary of

$921. Moreover, in a preliminary proceeding in the nature

of a hearing on motion to dismiss the complaint it seems

proper that the court determine whether any conclusion of

law fatal to the plaintiff’s case follows from the facts out

lined above. To that extent, and to that extent only, the

question of waiver was before the District Court and is in

issue upon the present appeal.

It is to be noted that so much of the “ Second Defense”

in the answer as raises the issue of waiver is in form a

defense in law in the nature of a motion to dismiss, but in

substance it combines a challenge to the sufficiency of the

complaint with an introduction of new matter in the nature

of an affirmative defense. Thus, the sub-paragraphs num

bered (4) and (5) (Appendix, p. 55) go beyond an allega

tion that acceptance of employment by the appellant is a

waiver of the rights asserted in his complaint. These

sub-paragraphs refer to the specific contract of the appellant

and incorporate by reference an attached document de

scribed as a copy of his contract. In thus going beyond the

fact of employment pursuant to a contract of hire as already

revealed by the complaint and pertinent statutes, and

in attempting to put in issue the terms of a particular

contract, the circumstances of its execution and any legal

. ' MlSsSlcil W S m

24

conclusions that may depend upon such terms and cir

cumstances, the appellees have introduced an affirmative

defense. Under Rule 8(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, such new matter is deemed to be denied without

reply. Indeed, no reply is permitted except by order of the

court. See Rule 7(a). Therefore, the new matter alleged

in the answer was not before the court on a motion to dis

miss and is not material to the present appeal.

In brief, the question now at issue is whether the facts

(1) that appellant’s status was created by a contract of

hire and (2) that he has been employed for a definite salary,

operate as a matter of law to preclude this suit. Clearly the

answer to this question is in the negative and, therefore,

the appellants contend that the judgment of the District

Court cannot be sustained. Even if the answer to this ques

tion should be—and the appellants do not concede the cor

rectness of such an assumption—that the circumstances of

the particular hiring must be considered before the issue

of waiver can be decided, the judgment of the District Court

is in error because such an issue can be determined only

by a hearing on the merits.

A. The Contract of Hire Is Not Affected by the Relief

Sought

No modification of the contract of hire is sought in this

case. The appellants ask for declaratory relief in the

form of a decree that the policy, custom and usage of dis

crimination in salary schedules solely on the basis of race

and the actual discrimination against them solely on ac

count of their race are a denial of equal protection of the

laws. Injunctive relief is sought in the form of a decree

restraining the appellees from applying the discrimina

tory salary schedule and from continuing the practice of

racial differentials in teachers’ salaries.

It is to be emphasized that under the prayers of the com

plaint the appellees would be left free to determine the

25

actual salary of each teacher on any basis other than race.

Certainly the Court is not asked to amend any contract or

to determine the wage to be paid to any teacher.

Moreover, although the appellants seek immediate relief

they complain of a continuing wrong. They have a very

real interest in protection against the continuation of this

discrimination from year to year in the future. It is within

the discretion of a court administering equitable relief to

determine whether its injunctive decree shall impose an

immediate restraint or whether the decree shall become

operative at some other date determined in the light of

the equities of the case before it. Thus, in Mills v. The

Board of Education, supra, under prayers essentially simi

lar to those in the present case, the court declared the un-

constitutionality of a racial salary differential and re

strained its continuance as of the beginning of the next

school year.

The value of such a prospective decree and the interest

of the appellants in obtaining such prospective relief, if

the court in its discretion should thus postpone the oper

ation of its decree, are apparent. A teacher has a reason

able expectancy of reemployment from year to year, par

ticularly such a teacher as the appellant Alston, who has

been employed continuously for the past five (5) years

(Appendix, p. 44). Yet his opportunity to bargain for and

to obtain compensation for the next year is impeded by the

existing salary schedule and by the custom and practice of

paying colored teachers less than white teachers solely

because of their race. That this impediment is an effective

barrier is shown by appellees’ denial of appellant Alston’s

petition for the discontinuance of the racial salary differ

ential at the beginning of the present school year (Ap

pendix, p. 50) and by the denial of a similar petition of

another Negro school teacher at the beginning of the

preceding year. (Appendix, p. 50.)

Thus, the waiver argument is but colorable at best since

the court is not asked to modify any contract; and with

26

reference to possible prospective relief for the next school

year the waiver argument has no basis whatever. Yet, the

contention of appellees and the holding of the District Court

seem to be that the appellant Alston is precluded from ob

taining immediate relief because he is under a contract of

employment for the current school year, and that he is pre

cluded from obtaining any prospective relief which will

benefit him in bargaining for compensation for next year

because he is not now under contract for that year. In

brief, the decision below puts him in the dilemma of being

unable to acquire such a status and interest as will give him

standing to challenge a constitutional wrong without

waiving his objection to that wrong.

B. The Doctrine of Waiver Has Been Held Inapplicable to

Analogous Dealings with Public Authorities

The cases generally hold that the acceptance of public

employment at a particular salary is no waiver of the right

subsequently to object to the unconstitutionality of unlaw

ful conduct of public administrative officers in fixing that

salary. Cases involving various contractual relations with

agencies of the state are in accord. In the cases which

follow, courts have gone far beyond any relief sought in the

present case and have actually modified contracts of public

employment and other contracts with public agencies.

Courts have granted relief against discrimination be

tween salaries of men and women teachers, or between the

salaries of married and single women, imposed by public

authority contrary to law, despite the complainants ’ agree

ments to accept a discriminatory salary.

Hutton v. Gill, 212 Ind. 164, 8 N. E. (2d) 818 (1937);

Moses v. Board of Education, 127 Misc. 477, 217 N. Y. S.

265; rev’d on other grounds, 245 N. Y. 106 (1927);

Rockwell v. Board of Education, 125 Misc. 136, 210

N. Y. S. 582; rev’d on other grounds, 214 App. Div.

431, 212 N. Y. S. 281 (1925).

Cf.: Chambers v. Davis, 131 Cal. App. 500, 22 P. (2d)

27 (1933).

To the same effect are the cases in which a teacher has

complained of an illegal retirement deduction or other de

nial of benefits incidental to his employment accomplished

by imposition of the school authorities, but with his formal

consent.

Minnesota ex rel. Jennison v. Rogers, 87 Minn. 130,

91 N. W. 438 (1902)

Hibbard v. State ex rel Ward, 65 Ohio St. 574, 64 N. E.

109 (1901)

School District v. Teachers’ Retirement Fund Assn.,

Ore. —, 95 P. (2d) 720, 96 P. (2d) 419 (1939).

The same conclusion is reached in the long line of cases

involving agreements to accept less than the statutory sal

ary of a particular office.

Glavey v. United States, 182 U. S. 595 (1901)

Miller v. United States, 103 Fed. 413 (1900)

Settle v. Sterling, 1 Idaho 259 (1869)

Whiteley County Board of Education v. Rose, 267 Ky.

283, 102 S. W. (2d) 28 (1937)

People ex rel Satterlee v. Board of Police, 75 N. Y. 38

(1878)

Cf.: Pederson v. Portland, 144 Ore. 437, 24 P. (2d)

1031 (1933) (Alleged waiver of double compensation

for overtime)

Courts have not hestitated to invalidate bargains between

public officers and independent contractors upon the com

plaints of such contractors that the contracts signed by them

contained terms which the public authorities had imposed

in violation of some constitutional or other legal right.

28

Lukens v. Nye, 156 Cal. 498, 105 Pac. 593 (1909)

People ex rel Rodgers v. Coler, 166 N. Y. 1, 59 N. E.

716 (1901)

City of Cleveland v. Clements Bros. Construction Co.,

67 Ohio St. 197, 65 N. E. 885 (1902)'

R a tionale op t h e D ec isio n s

Considerations of equity and public policy underlie the

refusal of courts to recognize any waiver or estoppel in

these cases.

Where a statute or administrative order or regulation

requires the discriminatory or otherwise illegal action in

question, the person dealing with the public agency has no

such choice or freedom of bargaining with reference to

that phase of the transaction as will on equitable principles

create an estoppel. The subject matter in question has been

removed from the area of free bargaining by the illegal

conduct of the state or its agents. The illegal element in

the transaction is present not because of voluntary agree

ment of the parties that it be there but because govern

mental authority has required that it be there.

See Minnesota ex rel. Jennison v. Rogers, supra

City of Cleveland v. Clements Bros., supra

Whiteley County Board of Education v. Bose, supra

The fact that appellants are met at the threshold of their

transaction with the state by a schedule and a practice of

race discrimination in salaries leaves them only the alter

natives of foregoing employment altogether or accepting

employment under conditions of discrimination. This situ

ation is emphasized by the fact, pleaded by the appellants

(Appendix, p. 50) that a petition filed by a Negro school

teacher on behalf of herself and the other Negro teachers

of Norfolk in October, 1939, requesting the elimination of

racial salary differentials was denied. In such circum

stances submission to discrimination cannot be said to be

29

voluntary in the sense in which a choice must be voluntary

to constitute a waiver of objection to the imposed condition.

“ Were the rule otherwise it would be comparatively an

easy matter for the governing authorities to take ad

vantage of an officer dependent upon his salary for a

livelihood and virtually compel him to forego his con

stitutional right.” Whiteley County Board of Educa

tion v. Rose, 102 S. W. (2d) at p. 30.

A comparable and analogous situation arises when a state

imposes upon a foreign corporation, as a condition of con

tinuation in business within its borders, the payment of a

tax which denies the corporation equal protection of the

laws. The corporation may remain in the state and resist

the tax.

Hanover Fire Ins. Co. v. Harding, 272 U. S. 494 (1926)

Similarly, when the privilege of using the public highway

as a private carrier for hire is conditioned upon the assump

tion of the obligations of a public carrier the entrepreneur

may use the highway in his business as a private carrier

and at the same time resist the unconstitutional condition.

Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission, 271 U. S.

583 (1926)

“ Having regard to form alone, the act here is an offer

to the private carrier of a privilege, which the state

may grant or deny, upon a condition, which the carrier

is free to accept or reject. In reality, the carrier is

given no choice, except a choice between the rock and

the whirlpool—an option to forego a privilege which

may be vital to his livelihood or submit to a require

ment which may constitute an intolerable burden.”

(271 U. S. at 593)

The court continues with language peculiarly apposite to

the contention of waiver in the present case:

30

‘‘It is not necessary to challenge the proposition that,

as a general rule, the state, having power to deny a

privilege altogether, may grant it upon such conditions

as it sees fit to impose. But the power of the state in

that respect is not unlimited; and one of the limitations

is that it may not impose conditions which require the

relinquishment of constitutional rights. If the state

may compel the surrender of one constitutional right

as a condition of its favor, it may, in like manner, com

pel a surrender of all. It is inconceivable that guaran

tees embedded in the Constitution of the United States

may thus be manipulated out of existence.” (271 U. S.

at p. 593-4)

Again, the Supreme Court has held in Union Pacific Rail

way v. Public Service Corporation, 248 U. S. 67 (1918), that

in applying for and obtaining a certificate which was a

statutory prerequisite to the issuance of certain bonds, the

corporation did not waive its right to contest the consti

tutionality of the condition thus imposed on it.

“ The certificate was a commercial necessity for the

issue of the bonds. . . . Of course, it was for the in

terest of the company to get the certificate. It always

is for the interest of a party under duress to choose

the lesser of two evils. But the fact that a choice was

made according to interest does not exclude duress. It

is the characteristic of duress properly so called.”

(248 U. S. at p. 70)

The common element of duress resulting from imposition

of economic pressure characterizes the action of the public

authorities in all of these cases as in the case at bar. The

state leaves the constrained person merely a choice be

tween accepting an unconstitutional and otherwise illegal

arrangement on the one hand or suffering serious loss on

the other. No doctrine of waiver founded on equitable

principles can have application in such a situation. “ Guar

antees imbedded in the Constitution of the United States

(cannot) thus be manipulated out of existence.”

31

In addition to the considerations above presented, the

question of public policy is emphasized in a large number

of decisions against alleged waiver of advantages incidental

to public employment. The courts have reasoned that the

deprivation of rights to salary or other benefits incidental

to public employment, or incidental to some other public

relationship, involves not only the individual interest of

the person immediately effected, but also the public interest

in the public activity in which that person is engaged.

Thus, in the already cited cases of statutory salaries the

courts agree that there is a controlling public interest in

the protection of the public service against the demoralizing

effect of salary reductions below’ the amount legislatively

determined to be adequate, and that no waiver by the in

dividual employee can be effective in such circumstances.

To the same effect is School District v. Teachers’ Retirement

Fund Assn., supra, where a teacher’s express waiver of

his right to certain disability compensation was held to be

against public policy and therefore ineffective.

The case at bar involves the very important public in

terest in maintaining an effective public school system and

in providing equal educational opportunities for white and

colored children. Express declarations of such interest and

policy appear in Section 129 of Article IX of the Constitu

tion of Virginia and in Sections 680 and 786 of the School

Code of Virginia.

“ The general assembly shall establish and maintain

' an efficient system of public free schools throughout

the State.” Va. Const., Art. IX, Sec. 129.

City school boards are required to

“ . . . establish and maintain . . . a general system

of public free schools in accordance with the require

ments of the constitution and the general educational

policy of the Commonwealth.” Va. School Code, Sec.

786.

32

‘ ‘ White and colored children shall not be tanght in the

same school, but shall be tanght in separate schools,

under the same general regulations as to management,

usefulness and efficiency.” Va. School Code, Sec. 680.

While colored teachers are held to the same professional

standards as white teachers and many colored teachers

manage to continue their professional studies so as to

achieve efficiency beyond the requirement of their classi

fication, it cannot be denied that the general effect of sub

stantial salary discrimination is to impose a barrier of

economic disadvantage which impedes the professional and

scholarly advancement of those who teach colored children.

The imposition of such a handicap upon the whole body of

teachers in colored schools is in plain derogation of the

legislative policy of maintaining an efficient school system

and the more specific policy of equality in educational facili

ties for white and colored children. It is also noteworthy

that, since on the record race and color are admitted to be

the sole basis of the unlawful discrimination, there is not

even a design to promote any public interest through this

discrimination.

For these reasons, public policy alone is a sufficient basis

for judicial refusal to impose any estoppel or waiver upon

a teacher who complains of unconstitutional salary dis

crimination against Negro teachers.

C. Decision on the Waiver Issue Was Erroneously Based

Upon Facts Not Before the District Court

The foregoing discussion of waiver presupposes that a

decisive answer on the question of waiver or estoppel can

be given on the appellants’ complaint and applicable stat

utes. Appellants, for the reasons hereinbefore presented,

contend that it is clear that no waiver results from the con

duct of appellant Alston. Appellees, on the other hand,

contend that employment pursuant to a contract of hire

results as a matter of law in waiver of the rights herein

33

asserted. But the District Court took an intermediate posi

tion,—that waiver is a question to be determined upon the

facts of the particular hiring. The following excerpts from

the opinion of the District Court show that court’s approach

and analysis:

“ A defense set up in the answer . . . and which stands

out in the record as an undisputed fact, is that some

time before this suit was instituted the plaintiff entered

into a contract with the defendant school board, which

contract covers the subject matter of this litigation. . . .

“ A copy of that contract is in the record before the

court. There is an absence of any claim that I can find

in the complaint to the effect that the plaintiff was in

duced to enter into the contract by fraud, misrepre

sentation or that it was entered into under duress or

that any unfair means were employed by defendants

in that behalf, or that it was ever made or signed under

protest. . . . I am fully aware of the fact that in situ

ations of this kind it sometimes happens that the em

ployee is at a distinct disadvantage, is not in a position

boldly to assert what he conceives to be his rights, and

does not, in fact, therefore, contract freely with the

other party. But I do not find in the record any facts

that have been pleaded by way of explanation that could

reasonably justify the court in reaching the conclu

sion that it ought to disregard the written contract and

further proceed in the case in spite of the fact that

the plaintiff voluntarily entered into such contractual

relation with the defendants. ’ ’ (Appendix, pp. 61-62.)

The error of this analysis, in addition to the mistaken

premise that the issue of waiver in this type of case cannot

be dismissed without consideration of the details of the

particular hiring, is that new matter, pleaded in the answer

and an exhibit to the answer, is used as the factual basis of

decision on a motion to dismiss the complaint. It is beyond

question, both before and since the adoption of the present

Rules of Civil Procedure, that such pleadings and exhibits,

extrinsic of the complaint, cannot be considered on a motion

to dismiss.

34

Cf.: Polk v. Glover, 305 U. S. 5 (1938) ^

Gibbs v. Buck, 307 IT. S. 66 (1939)

Jouner v. Browning, 30 F. Supp. 512 (D. C. W. D.

Tenn., 1939)

As heretofore pointed out, the terms and circumstances

of hiring pleaded in the answer represent an attempt to as

sert an affirmative defense, and under Civil Rule No. 7(a)

such new matter is deemed denied without reply. If the

terms of the particular hiring are material, or if the con

duct of the parties prior to and at the time of the particular

hiring have any legal significance in a case of this char

acter, then decision on the issue of waiver should have been

for the appellants on preliminary hearing, with ultimate

decision on the issue reserved for determination after a

final hearing on the merits.