Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief for Appellants with Suggestion for En Banc Hearing

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief for Appellants with Suggestion for En Banc Hearing, 1972. cc10b6bf-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cdf7f0fe-ceaf-4790-ad3a-8ccb4503f127/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants-with-suggestion-for-en-banc-hearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

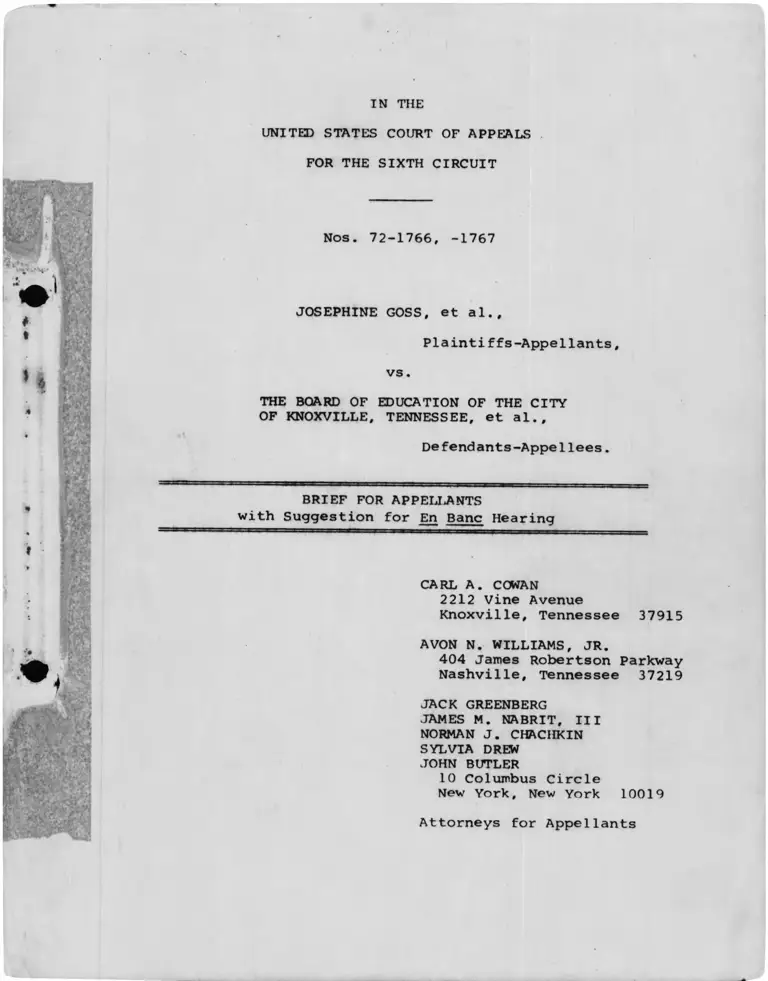

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 72-1766, -1767

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et al.#

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

with Suggestion for En Banc Hearing

CARL A. COWAN

2212 Vine Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN SYLVIA DREW

JOHN BUTLER10 Columbus CircleNew York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 72-1766, -1767

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-AppeHants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et al.,

„ Defendants-Appellees.

SUGGESTION FOR EN BANC HEARING

Appellants, by their undersigned counsel, and pursuant

to Rule 35, F.R.A.P. and Rule 3, Sixth Circuit Rules,

respectfully suggest that this matter would be appropriately

heard by the Court en banc for the following reasons:

1. Pursuant to the normal practice of this Court, these

appeals will be assigned to a panel consisting of Circuit

Judges Weick and Miller, and Senior Circuit Judge O'Sullivan.

See Goss v. Board of Educ.. 444 F.2d 632 (6th Cir. 1971).

2. A majority of that panel also formed the majority of

the panel which decided Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga.

Nos. 71—2006, —2007, 72—1443, -1444, on October 11, 1972.

3. Most of the issues in the instant appeals are identical

to issues raised in the Mapp case; the plaintiffs' expert

witness was the same individual in both cases and in each

plaintiffs contend that a plan utilizing pupil transportation

must be adopted in order to bring about Constitutional compliance.

4. Plaintiffs in Mapp have sought a Rehearing En Banc

of the panel's October 11, 1972 decision therein, and it would

be appropriate to grant same in that case, act favorably upon

this Suggestion, and set the matters down for argument before

the entire Court at one time.

5. The decisions of the various panels of this Court in

school desegregation cases are in serious conflict (see opinion

of Edwards, J., dissenting in Mapp, supra). Resolution of

these conflicts by the Court en banc will materially assist

litigants and district judges in this Circuit.

WHEREFORE, appellants respectfully suggest the appropriate

ness of a hearing en_ banc on these appeals.

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Pkwy.

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

CARL A. COWAN

2212 Vine Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

JOHN BUTLER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

-2-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Issues Presented for Review .................... 1

Statement

Introduction .............................. 2

School Segregation in Knoxville 1971-72 . . 3

Desegregation Efforts Since 1960 .......... 5

Residential Segregation in Knoxville . . . . 14

Proposals for Further Desegregation . . . . 16

Page

Financing Desegregation .................. 21

The District Court's Ruling .............. 23

ARGUMENT

The District Court's Finding That Knoxville

Has A Unitary School System Is Contrary To

Swann, Other Controlling Decisions Of The

Supreme Court, This Court's 1971 Remand In

This Case And Other Decisions Of This Court;

It Is Based Upon Faulty Factual Premises And

The Application Of Erroneous Legal Standards 26

The District Court Erred In Approving The

School Board's Proposal To Close A Black

Elementary School Without A Showing That

Discontinuation Was Required For Non-Racial

R e a s o n s .................................. 37

The District Court Should Have Awarded

Attorneys' Fees And Litigation Expenses To

The Plaintiffs

A. An Award Is Required Under

Traditional Equitable Principles . . 40

B. An Award Is Required By §718,

P.L. 9 2 - 3 1 8 ...................... 52

Conclusion.................................... 60

[Appendices A & B]

L

Page

CASES:

Adams v. School District No. 5, Orangeburg,

444 F.2d 99 (4th Cir. 1971), aff'g Green

v. School Bd. of Roanoke, 316 F. Supp. 6

(W.D. Va. 1970)................................... 38

Armstrong Paint & Varnish Works v. Nu-Enamel

Corp., 305 U.S. 315 (1938)........................ 58

Bell v. West Point Municipal Separate School

Dist., 446 F. 2d 1362 (5th Cir. 1971).............. 38

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 325 F. Supp.

828 (E.D. Va. 1971).............................. 36

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28

(E.D. Va. 1971).................................. 50, 51

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943

(4th Cir.), cert.denied, 406 U.S. 905 (1972)...... 35Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp. 974 (N.D. Calif.1969) . ........................................... 38

Brown v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 464 F.2d382 (5th Cir. 1972).............................. 35

Carpenter v. Wabash Ry. Co., 309 U.S. 23 (1940)..... 53Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 429F. 2d 382 (5th Cir. 1970).......................... 38

Chambers v. Iredell County Bd. of Educ., 423

F. 2d 613 (4th Cir. 1970).......................... 38

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe,401 U.S. 402 (1971).............................. 54n

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709 (E.D. La. 1970), aff'd 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir.

1971)........................................... 40n, 58Clark v. American Marine Corp., 304 F. Supp.603 (E.D. La. 1969).............................. 45

Cleveland v. Second National Bank & Trust Co.,

149 F.2d 466 (6th Cir.), cert, denied 326U.S. 777 (1945)........ ...................... 43

Crawford v. Board of Educ. of Los Angeles,

No. 822-854 (Super. Ct. Cal., Jan. 11, 1970)... 41,47,50

Davis v. School Comm'rs of Mobile County, 402

U.S. 33, 91 S. Ct. 1289, 28 L .Ed.2d 577 (1971)___ 23,26Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Educ., 406 F.2d

1183 (6th Cir. 1969).............................. 27nDeal v. Cincinnati Board of Educ., 369 F.2d

55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied 389 U.S.

847 (1967)....................................... 26,27

Dobbins v. Local 212, IBEW, 292 F. Supp. 413(S .D. Ohio 1968)................................. 45

Dolgow v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472 (E.D. N.Y.1968)............................................. 49

Drummond v. Acree, No. A-250 (September 1,

1972) (Mr. Justice Powell, Circuit Justice) 58-59

Page

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 391 F.2d 555(2d Cir. 1968)..................................... 49

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers,

237 Ore. 139, 390 P.2d 320 (1964).................. 49n

Glover v. Housing Auth. of Bessemer, 444 F.2d

158 (5th Cir. 1971)................................ 54n

Gordon v. Jefferson Davis Parish School Bd.,

446 F. 2d 266 (5th Cir. 1971)....................... 39

Goss v. Board of Educ., 444 F.2d 632 (6th Cir.),

immediate relief denied with instructions to

issue mandate, 403 U.S. 956 (1971)............ 2,27,29

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968)...... 45n

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 (1959)............... 57n

Greene v. United States, 376 U.S. 194 (1964)...... 56n,57n

Hall v. Beals, 396 U.S. 45 (1969).................... 54

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 424 F.2d

320 (5th Cir. 1970)................................ 54n

Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964)....... 54

Hammond v. Housing Auth. & Urban Renewal Agency,

328 F. Supp. 586 (D. Ore. 1971).................. 45,49Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 364

(8th Cir. 1:970)........................... ......... 38

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., 433 F. 2d 387 (5th Cir. 1970)................ 34

Hill v. Franklin County Board of Educ., 390

F. 2d 583 (6th Cir. 1968).......................... 47

Johnson v. United States, 434 F.2d 340 (8th Cir.1970).............................................. 54n

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 (1968)........ 43,45n,46,48

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.,

463 F. 2d 732 (6th Cir. 1972).................. 4n,35,39

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86

(4th Cir. 1971)......... 45,58

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746

(5th Cir. 1971).................................... 38

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143

(5th Cir. 1971).................................... 58

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d 290(5th Cir. 1970).................................... 46

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)...... 45n

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, Nos.

71-2006, -2007, 72-1443, -1444 (6th Cir.,

October 11, 1972).................................. 36n

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426

F. 2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970)......................... 47,48

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375

(1970).......................................... 42n,47

Monroe v. Bd. of Comm'rs of Jackson, 244 F. Supp.3 53 (W.D. Tenn. 1965).........................

ii i

47

Page

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Educ.,

418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir.1969) (en banc)(per curiam)....................................... 41

Newbern v. Lake Lorelei, Inc., 308 F. Supp. 407,

1 Race Rel. L. Survey 185 (S.D. Ohio 1968)......... 46n

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

390 U.S. 400 (1968)............... 44,47,48,51,57,58,59Northcross v. Board of Educ., No. 72-1630

(6th Cir., Aug. 29, 1972)........................ 4n,28

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co.,

433 F. 2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970).................. 44-45, 51Pina v. Homsi, 1 Race Rel. L. Survey 18

(D. Mass. 1969).................................... 46n

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., No.

71-1966 (6th Cir., September 21, 1972) ............ 39Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R.R., 186 F.2d 473(4th Cir. 1951).................................... 49n

Rolfe v. County Board of Educ. of Lincoln

County, 282 F. Supp. 194 (E.D. Tenn. 1966),

aff'd 391 F. 2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968).................. 47

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948)................ 16Siegel v. William E. Bookhultz & Sons, Inc.,

419 F. 2d 720 (D.C. Cir. 1969)...................... 44n

Smith v. St. Tammany Parish School Board,

302 F. Supp. 106 (E.D. La. 1969)................... 38

Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (M.D. N.C. 1969).... lOn

Sprague v. Ticonic National Bank, 307 U.S. 161

(1939)..................................... 43-44,47,58nSullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396U.S. 299 (1969).................................... 47

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)............................... passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D. N.C. 1971)................. 38

Terry v. Elmwood Cemetery, 307 F. Supp. 369

(N.D. Ala. 1969).................................. 46n

Thorpe v. Housing Auth. of Durham, 393 U.S. 268

(1969)........................................ 53,54,56Tracy v. Robbins, 40 F.R.D. 108 (D.S.C. 1966)........ 47

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin

County, 423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970).............. 54n

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School Dist., 460 F.2d 1205 (5th Cir. 1972)........ 35

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1

Cranch) 103 (1801)............................... 53,56nUnited States v. Scotland Neck City Be], of

Educ., 407 U.S. 484 (1972)......................... 26

IV

Page

Vandenbark v. Owens-Illinois Glass Co./

311 U.S. 538 (1941).............................. 53-54

Vaughan v. Atkinson, 369 U.S. 527 (1962)........... 44n,47

Wall v. Stanly County Board of Educ., 378

F.2d 275 (4th Cir. 1967)........................... 47

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972)................................ 26

Ziffrin v. United States, 318 U.S. 73 (1943)......... 54

STATUTES ;

42 U.S.C. § 1982 ......................... 43,44,45,47,48n

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ......................... 43,44,45,47,4842 U.S.C. § 2000a-3 (b) .............................. 47

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-l............................... . [ 56n

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16.............................. 56n

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

117 Cong. Record, S5483-92 (daily ed., April 22,

1971) and S5534-39 (daily ed., April 23, 1971)..... 55117 Cong. Record, S5484, S5490 (daily ed.,April 22, 1971).................................... 59

117 Cong. Record, S5485 (daily ed., April 22, 1971)... 59n

117 Cong. Record, S5537 (daily ed., April 23, 1971)... 59

United States Code, Congressional and AdministrativeNews, 1972, at 2406 ............................... 55

United States Comm'n on Civil Rights, Racial

Isolation in the Public Schools 65 (1967).......... 5n

v

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 72-1766, -1767

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented for Review

1. Whether the district court erred in holding that, with

the implementation of amendments to its desegregation plan

proposed by the Board of Education, Knoxville was operating a

unitary school system in conformity with Constitutional require

ments and with Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburq Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971).

2. Whether the district court erred in approving the

amendments to its desegregation plan proposed by the Knoxville

Board because such amendments unfairly burden black students

by closing black schools.

3. Whether the district court erred in denying plain

tiffs' motion for an award of attorneys' fees.

Statement

Introduction

These appeals are taken from the district court orders of

April 6, 1972 (denying plaintiffs' requests for further

desegregation of the Knoxville public school system, approving

the school board's proposed modifications to its plan, and

1/declaring the school system to be "unitary") (A. 1672) and

May 22, 1972 (denying the motion to alter and amend a May 1,

1972 district court order denying an award of attorneys' fees

in favor of plaintiffs) (A. 1674). The district court proceed

ings followed this Court's 1971 remand in light of Swann, supra,

and companion decisions by the United States Supreme Court

Goss v. Board of Educ., 444 F.2d 632 (6th Cir.j, immediate

relief denied with instructions to issue mandate. 403 U.S. 956

(1971).

In general, the contentions of the parties on the present

appeal are the same as those raised in 1971— and concern

whether or not Knoxville has, since the institution of this

lawsuit, taken adequate steps to dismantle its state-mandated

dual school system. Since that question was not resolved by

—^ Citations in the form "A. " are to the reproduced

Appendix on this appeal. Citations to the Appendices on

previous appeals will be designated "20,834 A. __, " "14,425

A. ___," etc. Citations to exhibits introduced during the

1971-72 hearings following this Court's remand are given as

" X

-2-

this Court in 1971 (in order to permit the district court to

evaluate its own ruling in light of the intervening decision

in Swann), and also to furnish the Court with information

relating to the background of this suit, we reprint as Appendix

_ 2/ A to this Brief, the Statement from our 1970 Brief, No. 20834.

Following this Court's remand, the Knoxville Board of

Education adopted certain amendments to its desegregation plan

(X 27, A. 1532); plaintiffs in the trial court opposed the

closing of black schools as part of the board's plan and

objected to the sufficiency thereof. After lengthy hearings,

at which plaintiffs' expert witness proposed an alternative

desegregation plan for Knoxville (X 19-22, A. 1526), and during

which the City of Knoxville, its Mayor and City Council were

joined as additional parties defendant (A. 1516), the district

court ruled that the amendments to the board's plan were

adequate and that the board was operating a unitary school

system (A. 1653).

School Segregation in Knoxville 1971-72

The Knoxville City school system is relatively small,

both in terms of total enrollment and of the percentage of

black students. In 1971-72, the system enrolled 34,876 students;

2 /— The detailed procedural history of this litigation appears

at n.2 therein.

-3-

of that number, 5,767 or 16.5% were black (X 8, A. 1518)-.-

However, of 64 schools in the Knoxville system, seven were

more than 90% black (ibid.; Table I infra). Sixteen schools

had all-white enrollments in 1971-72 and twelve others were

more than 99% white (with only 31 black students in attendance

among all twelve schools) (ibid.).

The seven black schools were initially constructed to

serve black students only (A. 854) and all except Cansler and

Maynard are located in the East Knoxville area. Together they

enroll more than 51% of Knoxville's black student

population, but only 32 white students attend these schools

(see Table I infra). 13,772 or 49% of all white students in

the system attend the twenty-eight 99% or 100% white schools,

1/along with only 30 black pupils (X 83, A. 1644). More than

82% of all white students in Knoxville attend schools more

than 90% white (ibid.).

Table I

1971-72 Enrollments of Virtually All-Black Schools

School Black Students White Students

Austin-East 693 4

Cansler 231 4

2/ The Memphis and Nashville school systems, each of which was

recently the subject of opinions of this Court, enrolled 145,581

students (53.6% black) and 94,170 students (24.6% black),

respectively. See Northcross v. Board of Educ., No. 72-1630

(6th Cir., August 29, 1972); Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.. 463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir. 1972).

4/ Thus, 51 of Knoxville's 64 schools are attended by 90% or

more students of one race, and serve 21,497 students — 61% of the entire school system's enrollment.

-4-

Eastport 442 3

Green 411 1

Maynard 288 10

Sam Hill 280 8

Vine 619 2

The reduction in the number of virtually all-black schools

since 1969-70 (see Appendix A, p. 13) results from (i) the

closing of Mountain View Elementary in 1970 in connection with

the relocation of the black population it served (c_f. A. 372-98),

and (ii) elimination of one of the more obvious segregatory

devices from the system (see Appendix A, p. 10) by pairing

Rule and Beardsley junior high schools, as directed by the

5/district court in 1970.

Other one-race schools in Knoxville have remained essen

tially unchanged since the commencement of this lawsuit.

Well, there are a number of schools that

have remained predominantly black; there

are a number of schools that have remained predominantly white . . . .

(A. 620) (Board Vice-Chairman Howard).

Desegregation Efforts Since 1960

The Board of Education takes the position that its

affirmative constitutional obligation to desegregate was

IT In its 1971-72 amendments, the Board finally proposed the

pairing of Sam Hill and Lonsdale Elementary Schools as well

(X 27, A. 1532), a measure proposed years ago by the Tennessee

Title IV (HEW) Center. See United States Comm'n on Civil Rights,

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools 65 (1967); Appendix A, at 10, n.12.

-5-

satisfied by its elimination of dual, overlapping attendance

zones and the substitution therefor of "neighborhood school"

zones. Current segregation is, in the Board's view, attributable

to independent residential segregation and is unrelated to the

dual system. Plaintiffs contended — and we believe the evidence

shows — that the present public school segregation is highly

related to official discrimination, including continuing dis

crimination by the School Board, and that the Board has never

undertaken the effective desegregation measures which the

Constitution requires of it. The conflict is exemplified by

the following testimony of Dr. Bedelle, the Assistant Superin

tendent and chief Board witness:

Q. You also indicated that school enrollments do

follow housing projects on direct examination.

You don't wish to change that now, do you?

A. Our school enrollment reflects practically

in every case the residential pattern that is in proximity to the school.

Q. And if the residential pattern is segregated

the school is segregated too, isn't it?

A. if that residential pattern is predominantly

black or white the school will reflect that, yes.

Q. And if that was the situation when desegrega

tion began, then the neighborhood school patterns

are insufficient to integrate the school, aren't they?

A. For the purpose of mixing all schools that is true.

(A. 127 ) .

6/The dual zones were eliminated in 1964-65 and since

single attendance areas were established for each school, there

17 See Appendix A, n. 2 .

-6-

have been no substantial changes in most of the zones (A. 103;

see also, A. 89; Appendix A, at 5). Dr. Bedelle compared the

present zones with the dual areas operative prior to 1960

(X 38-40) and found remarkable similarities, particularly inso

far as the black schools are concerned: the Cansler, Maynard,

Sam Hill, Green and Eastport zones encompass virtually the same

Vareas of Knoxville as the old "dual" zones (A. 92-100). Many

8/

of pre-annexation Knoxville's white school zones also remain

substantially unchanged: Fair Garden, Park Lowry, Fort Sanders,

Sequoyah, Perkins, West Hills, Claxton, McCallie, Brownlow,

Oakwood, Lincoln Park, McCampbell, Belle Morris, Flenniken

(incorporating the former Lockett zone). South Knoxville, and

Giffen (A. 100-02). Indeed, Dr. Bedelle testified, the school

board never redrew the zones in a manner which would achieve

substantia] desegregation because this would result in displacing

large numbers of students from the schools they formerly attended

(A. 161).

The prior explicit segregation policy of the board has

significantly influenced the residential segregation to which

the board now attributes continued school segregation in Knox

ville. Maintenance of the dual system caused the board to

locate schools in areas of racial concentration, but closer

I T Because residential patterns in Khoxville have always

been very highly segregated, the areas of actual overlapping zones were minimized.

8/ In 1963, a substantial portion of Knox County was annexed.

-7-

together than would otherwise have been necessary (A. 104).

The result is that the "neighborhood" zones for such schools

today are uniracial. Dr. Bedelle previously testified that the

school system's policy of building schools in racially concen

trated population centers (18,165 A. 233, 241) caused racially

discrete communities to develop near schools designated for

children of each race (20,834 A. 411; 18,165 A. 227).

This relationship between school location and housing

patterns has been noted by the Supreme Court, Swann, supra,

402 U.S. at 20-21, and by scholars. Dr. Karl Taeuber, a noted

demographer, testified below that

There is a reciprocal relationship between the

school attendance zone and neighborhood resi

dential patterns such that segregation in one tends to reinforce segregation in the other.

(A. 774 ). Dr, Taeuber stated that in his opinion, the actions

of Knoxville school authorities have contributed significantly

9/to residential segregation in the city (A. 818).

The school construction policies of the board since 1960

have exacerbated racial segregation within the school system.

The Director of the Metropolitan Planning Commission, which has

2/ Similarly,Rodney Lawler,Executive Director of the Knoxville Housing Authority, testified that if students were assigned to

"neighborhood" school zones, the location of schools near

segregated housing projects (as Knoxville's were prior to 1965 and as they remain today, A. 376, 380; X 16) would reinforce

the segregation of each institution (A. 375). The plaintiffs’

educational expert. Dr. Stolee, also discussed the influence

of Knoxville board actions upon the development of residential segregation within the City (A. 1317-19).

-8-

assisted the city and county school authorities in selecting

school sites, testified that his agency had never been asked

to plan for a biracial school population except for the new

Green school presently under construction in East Knoxville

(A. 1042). None of the schools in use which were constructed

after this suit was filed is attended by less than 90% pupils

of one race.

Dr. Bedelle stated that the major determinants of the

board's site selection policy are the availability of land and

10/the residential concentrations of pupils (A. 166-67 ) . The

board has never, with the exception of the new Green Elementary

school, affirmatively selected sites for the purpose of

desegregation (see 18,165 A. 224). The result is that new

schools have been constructed near the outer fringes of Knox

ville in spite of the considerable underutilization of classroom

space in central city schools. (There are between 1200 and

11/1500 empty spaces in these schools.) (X 54, A. 1557; A. 182).

— / In his 1970 testimony, Dr. Bedelle gave a long list of

factors justifying the location of the new Bearden and Central

High Schools; projected racial composition was not one of them (20,834 A. 356-59).

11/ Dr. Bedelle subsequently attempted to qualify his testimony by stating that the capacity figures provided in answers to

interrogatories had been prepared from outdated information

and were incorrect; that the number of available spaces should

be reduced by some 1200-1300 because some of the empty class

rooms are being utilized for such things as a PTA office or

clothing center (A. 532-33, 536, 542). However, Dr. Bedelle admitted that this space could be utilized and would be if it

was the only seating available for students (A. 581). in fact,

X 54 (A. 1557) understates the available chair space because

it lists only vacant classrooms (A. 572). Austin-East, for

example, is 203 students under its rated capacity, X 54 shows

all classrooms in use (a . 577). Dr. Bedelle testified that the

-9-

The effects of the board's construction policies resulting

in continued segregation were magnified by Knoxville's trans

portation practices and the assignment of Knox County children

attending Knoxville schools (most of whom are white). Pursuant

to the annexation agreement with Knox County in 1963 (X 10),

students residing within the area added to the city in that

year are furnished bus transportation to schools by the Knoxville

12/

board. Approximately 6100 Knoxville students utilize school

buses under the agreement (A. 669; A. 41); no other pupil

transportation is provided by the school board except for a

12/shuttle bus between the Austin and East facilities (A. 42).

Although schools in the annexed area are heavily crowded, how

ever (A. 184, 576), the students who receive transportation

anyway are not assigned to the underutilized central city schools

11/ cont'd

board has not attempted to utilize the available space in central

city schools rather than expanding the capacity of suburban facilities, even though this would have resulted in greater

desegregation, because pupil transportation "alienates" parents (A. 229). See text infra.

12/ The Knoxville board is empowered to furnish transportation

to any or all of its students but under Tennessee law, partial

State reimbursement for transportation services is payable only

to county boards of education (A. 677). Cf. Sparrow v. Gill,

304 F. Supp. 86 (M.D. N.C. 1969). Twelve Tennessee city school

districts have transportation agreements with their respective

county boards pursuant to which they receive proportional reim

bursement from the State (A. 678-79). In 1970-71 Knox County

received State reimbursement payments totalling $313,000, or

approximately 39% of its operating cost ($32.48 annually per

pupil) for transporting some 25,000 students — including those in the area annexed to Knoxville (A. 670-71).

13/ Prior to the direction of the district court during the

trial below, and despite the holding of the Supreme court in

Swann, 402 U.S. at 26-27, the board did not even provide free

transportation to students exercising majority-to-minority transfers (A. 82).

-10-

(A. 189). Instead, the school system purchases portable build

ings at a cost of between $10,000 and $12,000 to expand the

capacity of the predominantly white suburban schools (A. 171,

236, 189) despite the fact that desegregation is admittedly

14/retarded by this practice (A. 192). In addition, some 2800

Knox County resident pupils attend Knoxville schools (A. 6),

most of them white, but they (like the annexed area students)

are not assigned so as to desegregate the school system (X 41;

A. 187-89).

Not only did Knoxville never affirmatively redraw its

zone lines to achieve desegregation, nor employ construction

and site selection toward that goal, nor assign students it

was transporting anyway in order to integrate its facilities,

but the administration of its transfer policies over the years

has been so loose as to undercut even the minor increases in

desegregation which might have been anticipated had the atten

dance area boundaries been enforced. in 1970 the district

court wrote that

. . . it appears that there is some irregularity

in the administration of [the transfer] policy

. . . . In light of the former history of this

suit the Board has committed a grave omission in

failing to either enforce its transfer policy or

to maintain records to show that enforcement.

Failure to provide the requested information is

difficult to excuse. Approval of neighborhood

zones is specious when informal transfers occur

(?0,834 A. 317-18). Yet again this year the board's own bi-

racial committee strongly condemned the school authorities'

±2/ In analogous fashion in the past — but after the board came

under judicial decree to desegregate — black students were

contained in predominantly black schools by the construction of additions or expansion of their capacities while adjacent, nearby white facilities were underutilized (A. 858-62).

-11-

administration of transfer policies, charging in particular

that the failure of pairing Austin and East High Schools to

bring about meaningful and lasting desegregation resulted at

least in part from lax transfer policy enforcement (A. 1123;

accord, A. 80-81 [Bedelle: board processed 2000-3000 transfer

requests a year and there is some reason to believe vocational

transfers were abused]; A. 494 [Trotter, the board's educational

expert: the pairing of Austin and East had the inevitable

impact of increasing segregation]):

This Committee is in agreement that this entire

problem has been aggravated and compounded by

the questionable actions the Administration and

the School Board has taken on zone transfers in past years. This transfer situation seems to

involve not only the black and white ratio in

schools but athletes and personal favor. It

has been unfair and unwise. Unless the School

Board members can establish a reasonable trans

fer policy and abide by it, no plan will work;

and they will continue to lose community support.

(A. 1124).

The most flagrant example of transfer program abuse

concerns the decline of white enrollment at the paired Austin-

East High School after 1968. Although this was the subject

of considerable inquiry in the 1970 hearings (see the comments

of the district quoted above, 20,834 A. 317-18), Dr. Bedelle

had still made no effort to determine whether all of the white

students within the Austin-East zone had been properly trans

ferred; he admitted that the majority of such pupils had

obtained vocational transfers to Fulton (A. 602-04) and recog

nized the likelihood that vocational transfers had been abused

(A. H0-8J), Dr. Bedelle subsequently produced transfer records

-12-

and forms for some of the white students in the Austin-East

zone (X 82, A. 1567-1643) which showed that transfers had

been granted for such things as "emotional difficulty" (A. 1238-

11/39) or on explicitly racial grounds (A. 1326).

Finally, the board's attempts to desegregate its faculty

and administrative staff have been long delayed and ineffective.

Although the board has at last adopted a policy of reassigning

faculty members so as to establish in each school a faculty

whose racial composition approximates that of the system as a

whole (X 12, A. 1522; X 27, A. 1532), this was not effectuated

for the 1971-72 school year, during which several traditionally

black facilities maintained disproportionately black faculties

(A- 31-33; X 11, A. 1521). There has been virtually no change

on the principals-administrative staff level (X 11, A. 1521),

and both Dr. Bedelle and Dr. Stolee agreed that black schools

in Knoxville remain racially identifiable by virtue of having

16/black principals (A. 146 [Bedelle], A. 1300-02 [Stolee]).

There is only one black on the central administrative staff,

as Director of Federal Programs (A. 594). The system has done

very little to prepare faculty members for desegregation (A. 1501).

see n. infra.

16/ The only black principal assigned to a white school was a

first-year principal assigned to Belle House for one year prior

to its being closed (A. 229). Knoxville assigns principals

based upon their making application for vacancies, but never specifically told its black principals that it would be willing

to assign them to traditionally white schools (A. 225-27).

Dr. Bedelle also testified that some blacks refused appointments

at predominantly white schools (A. 37) but this was apparently not made a condition of their employment.

-13-

Residential Segregation in Knoxville

Consistent with the school board's thesis that it bears

no responsibility for either the residential segregation or

the school segregation in Knoxville, the defendants attempted

to establish that neither is the product of racial discrimina

tion. The board's witness on this subject, Dr. Champion, drew

his conclusions from secondary sources without any empirical

data at all (A. 274) and it is not unfair to say that his testi

mony was thoroughly discredited. Plaintiffs introduced very

substantial evidence to demonstrate that residential segregation

in Knoxville results from both official and private racial

discrimination.

As the district court found (A. 1657), blacks are rigidly

segregated in the city, generally into three areas (A. 345).

The witnesses all acknowledged the segregatory effect upon

residential development of school location under the dual

system (A. 104; 20,834 A. 411; 18,165 A. 227 [Bedelle]; A. 818

[Taeuber]; A. 376, 380 [Lawler]; A. 1317-19 [Stolee]; cf. A.

1211-12 [Sharpe]). They also recognized the important role

played in Knoxville by the location of segregated public

housing projects: Dr. Bedelle commented that most of the pre

dominantly black schools are very much affected by their location

near housing projects (A. 18-19, 107-12) which remain substan

tially segregated today (A. 114). See also, A. 791-93 (Taeuber);

A. 375 (Lawler). The expansion of the black population into

East Knoxville was facilitated by public urban renewal and

-14-

highway programs. Plaintiffs’ witness Rabin noted, for example,

that Interstate Highway 40, which generally parallels the

Southern Railroad right of way, was planned with a sufficient

deviation from the railroad route in East Knoxville as to

enclose all census tracts which in 1960 had any substantial

concentration of blacks (A. 337). Dr. Bedelle agreed that

urban renewal and public housing together account for eastward

movement of the black population from the Green-Mountain View

area near the center of the city (A. 106). Housing Authority

Director Lawler described how public housing in East Knoxville

was erected as a resource to receive blacks being relocated

from the Mountain View Urban Renewal area (A. 372, 383-85), in

which the replacement housing will probably be occupied by

whites (A. 390).

Private racial discrimination in the housing market is

well entrenched and also contributes Markedly to the existing

segregated residential patterns. Lawler thought "blockbusting"

tactics which accompanied the relocation of Mountain View Urban

Renewal Area residents contributed to the resegregation of

blacks in East Knoxville (A. 398) and that such practices

17/were continuing even at the time of the hearing (A. 396-97).

At the time of the hearing, the United States Department

of Justice was reported to be investigating the occurrence

of blockbusting practices in conjunction with public housing

and urban renewal projects in East Knoxville (A. 400). Examples of continued discrimination were revealed by the testimony of

Dr. Robert H. Kirk, a black University of Tennessee professor,

and Mrs. Paul Underwood that when they expressed interest in

West Knoxville properties, realtors informed them that the

owners would not permit sales to blacks (A. 980-81; A. 1005-06).

-1 5-

The President of the Knoxville Board of Realtors testified

that at least prior to 1968, the residential mobility of

Knoxville blacks was restricted (A. 1205), and that many sub

divisions in the city were and are all white because of the

use of restrictive covenants (A. 1196, 1200). Until recently,

the Knoxville Board's Code of Ethics, like that of the National

Association of Real Estate Boards, contained a provision

18/cautioning brokers from introducing "inharmonious" uses into

neighborhoods; while operative, the Code prevented blacks from

purchasing homes in white sections of the city (A. 1198-99).

The manager of a savings and loan association stated that prior

to Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), virtually all areas of Knoxville

except Mechanicsville and portions of East Knoxville other

than Mountain View were covered by racially restrictive covenants

which prevented blacks from obtaining mortgage loans to

purchase in white areas (A. 1139-40, 1145).

Proposals for Further Desegregation

In August, 1971, the school board adopted amendments to

its desegregation plan (X 27, A. 1532). The board proposed

to balance its school faculties so as to eliminate racial

identifiability, to further restrict transfers, to appoint a

biracial committee and to guarantee election of minority

cheerleaders. The amendments concerning student assignments

I q /— • Cf. A. 941-47 (testimony of Martin Sloan concerning FHA's replacement of explicit racial guidelines with provision against "inharmonious user groups").

-16-

included: the pairing of Sam Hill and Lonsdale elementary schools;

the pairing of Rule and Beardsley Junior High schools, the closing

of the Cansler Elementary school and division of its students

(black) between adjacent predominantly white Beaumont and West

View elementary schools; the closing of the Moses Elementary

school (predominantly white) and assignment of its students to

Maynard (black); the eventual closing of Robert Huff elementary

school upon completion of the new Sara Green school in East

Knoxville; the pairing of vocational programs at Austin-East

and Fulton High schools; and a minor zone change between Austin-

East and Holston High schools. The board did not make projections

of the anticipated racial distribution of pupils expected

from the changes.

Attached to the board's submission as an exhibit were

a series of recommendations for desegregation, including

additional attendance boundary changes, which the board did

not propose to adopt (A. 1535-43). At the trial it developed

that these recommendations formed part of a report to the board

from a University of Tennessee professor, Dr. Charles Trotter,

whom it had commissioned to develop a desegregation plan for

Knoxville "to get the best mix of children, and without any

19/

busing as part of the plan" (A. 407). He carried out his

instructions, but the board did not fully adopt his recommendations

— '' Compare A. 153 5-43 with A. 1549-56.

-17-

(A • 459) . lie was unable, however, to compare the desegregation

which would be achieved under his plan and that adopted by the

board (ibid.).

Dr. Trotter did say that while his recommendations would

eliminate some all-black schools, it would maintain schools

whose racial compositions are substantially disproportionate

to the total ratio in Knoxville even though experience and the

educational literature indicate that such schools are unstable;

he did not consider whether the results he projected at any

particular school or schools would be likely to lead to

resegregation (A. 462, 474). He described the changes in racial

composition which would result from his recommendations at

several schools as "not very substantial" (A. 479). Indeed,

his plan would increase the percentage of black students at

Eastport Elementary school, already more than 90% black (A. 480).

These results flowed from the limitations placed upon him by

the board: he agreed that it was very difficult to achieve

any substantial desegregation merely by peripheral tinkering

with the zone lines (A. 481).

Plaintiffs’ expert witness, Dr. Michael Stolee, analyzed

Dr. Trotter's plan as follows: It would affect only twenty-one

of Knoxville's 64 schools (A. 1333), it would eliminate one

all-black elementary school (Sam Hill) by pairing but establish

two schools in its stead which remain substantially disproportionate

-18-

to the system-wide ratio (A. 1334-35); achieve similar results

by pairing Rule and Beardsley without involving other junior

and senior high schools in substantial desegregation efforts

(A. 1336); and in general, it would make only minor changes in

racial composition at other affected schools (A. 1340; X 84,

A. 1646).

The board's amendments would achieve even less desegre

gation than Dr. Trotter had proposed (A. 452). Vice-Chairman

Howard testified that the board had decided not to utilize

transportation of pupils as a technique for desegregation

because of fiscal problems and because in its judgment, the

majority of the community did not favor busing for desegregation

(A. 610). The bi-racial committee recommended that busing b.̂

kept to a minimum and restricted to secondary schools (A. 1100)

but its Chairman was astounded to learn that over 6,000 students

in the system are already transported to school at public

expense (A. 1120-21).

Plaintiffs' expert educational witness, Dr. Michael

Stolee, presented an alternative desegregation plan to maximize

integration by using the techniques of pairing, zoning, grade

restructuring, and pupil transportation (X 19-22). At the

elementary level, its typical approach was to cluster one

-19-

predominantly black elementary school with several predominantly

white schools and restructure the grades (A. 1346-53). The

clusters, contiguous and non-contiguous, are based upon the

existing school zones established by the Knoxville school

authorities (A. 1364). At the junior high school level, the

plan utilized some grade restructuring and both contiguous and

non-contiguous zones drawn by combining existing elementary

school attendance areas (A. 1366-71). With little exception,

the junior high school zones would operate like a feeder

pattern, assigning children who attended the same elementary

schools to the same junior high schools (A. 1372). The basic

technique for senior high school desegregation is noncontiguous

zoning (A. 1373-76).

Dr. Stolee further proposed specific faculty desegregation

policies (X 85, A. 1647) and reporting provisions (X 86, A. 1650;

A. 1383).

Dr. Stolee made a general and flexible assumption that

in Knoxville, with a total black student population of 16.5%,

truly desegregated schools would range between 10%-30% black (A.

1296), but under the plan he devised in light of the practical

limitations in Knoxville, individual schools were projected to

range from 8.6% black to 39.1% black (A. 1526-31). Dr. Bedelle

agreed that Stolee's plan did not propose an absolute or fixed

percentage (A. 1492).

-20-

Financing Desegregation

Dr. Stolee projected, on the basis of his experience that

only 75% of those students eligible for free transportation

actually take advantage of it (A. 1357), that 5,104 pupils

20/

would require transportation under his plan (A. 1408),

although some of these students might already be receiving it/

pursuant to the annexation agreement. Estimating a per pupil

21/

cost of $36 annually, he placed the expense of implementing

his plan at less than $200,000 — about 1% of the board's

22/

$23,000,000 budget for 1971-72 (A. 58).

Considerable evidence was introduced concerning the

financial condition of the school system and the City of

Knoxville, which furnishes approximately 10% of the board's

annual budget (A. 513). The retiring Mayor of the city stated,

for example, that Knoxville is presently taxing at its limit

under Tennessee law (A. 503-04) and has never had sufficient

funds to carry out its program needs (A. 529). However, he

Dr. Stolee attempted to avoid long, cross-town busing in

grouping schools in contiguous or noncontiguous clusters under

his plan.

21/— Knox County's annual per pupil transportation expense is

$32.48 (A. 671) and pupil transportation costs in Knoxville

are estimated to be a little higher (A. 678).

— ^The school board's 1971-72 budget contained no allocation

for school desegregation (A. 56).

-21-

said that he would not recommend postponing constitutional

compliance until the city's revenue problems were worked out

because, in his opinion, that day would never come (A. 530).

Although anticipated revenues of the school system for

1971-72 were expected to drop by $200,000 (A. 1169), the

Assistant Superintendent for Business Affairs testified that

a surplus of $250,000 was projected for fiscal 1973. Both

the school board (A. 1187) and the city (A. 749) can reallocate

funds within their budgets. And while the City Charter limits

the regular tax rate to $2.85, it may be raised in order to

cover an operating deficit incurred during the previous fiscal

year (A. 750). Although the Charter also prohibits the

intentional creation of a deficit as a means of circumventing

the tax rate limitation, when a retroactive teachers' salary

rise was negotiated by the Board of Education, the City Council

and Mayor gave the board express advance promise that additional

funds would be appropriated by the council in the following

fiscal year to cover the operating deficit which resulted (A. 1180)

As a result of the repayment of short-term notes sold to finance

the retroactive payments, the City may enjoy a surplus of

$1,500,000 in fiscal 1973 (A. 752).

Theotis Robinson, one of the original plaintiffs in this

-22-

23/

lawsuit, and now a Knoxville City Councilman, testified

that it was his belief that if additional funds were required

to carry out a desegregation order, City Council could furnish

the money to the school board (A. 748).

The District Court's Ruling

In a lengthy opinion, the district court endorsed virtually

everything about the Knoxville school system, and concluded that

Knoxville is in compliance with Swann.

Accordingly, Knoxville is operating a

unitary school system consistent with

constitutional requirements. [A. 1671)

The opinion is reported at 340F.Supp. 711 (A. 1653-71).

The opinion contains a lengthy discussion of the geography

and topography of Knoxville designed to support the district

court's conclusion that the city "is substantially more complex

than that found in Davis v. School Comm1rs of Mobile County,

402 U.S. 33, 91 S.Ct. 1289, 28 L.Ed.2d 577 (1971) . . . ." (A.

1656). It then documents the intense residential segregation

in the city (A. 1656-58) and summarizes changes in pupil

enrollments since this lawsuit was commenced (A. 1658-59),

classifying schools as "integrated" so long as they are not

"all one race," whether or not there is any substantial

2 3/Neither Robinson nor his wife, also one of the original

plaintiffs in this action, ever got to attend an integrated

school in Knoxville (A. 744-45).

-23-

integration. The court then turns to the board's "neighborhood

school" zones and terms them "reasonable" (A. 1659-61).' Sum

marizing the board’s 1972 proposals (A. 1661-62), it approves

the board's reasons for failing to adopt the additional

recommendations of Dr. Trotter (A. 1662-63).

The district court completely dismisses Dr. Stolee's

plan and testimony because of various supposed defects: Dr.

Stolee did not use the pupil locator map in drawing his plan

(A. 1663); Dr. Stolee "grossly understated" the actual amount

of busing under his plan (A. 1666); Dr. Stolee has a "manifest

interest" in school desegregation cases (ibid.) ; his plan

would not permit bused students to participate in extra

curricular activities, did not consider capacity, would require

modification of city-county agreements and might result in a

loss of certain State funds (A. 1666). We deal with the

district court's findings in the Argument, infra.

The court holds faculties, including principalships,

adequately desegregated (A. 1667), rules there is no credible

evidence that the transfer policies have promoted segregation

(ibid.), and sanctions Knoxville's school construction policies

because the board lacks the money to operate a transportation

system (A. 1668) .

A busing plan is impossible because of lack of funds

-24-

(A. 1669), finds the Court. Turning to conclusions of law,

the court characterizes plaintiffs' requests for relief as

demands for racial balance, which it finds barred by Swann

(A. 1670). "We do not interpret Swann as invalidating the

neighborhood pupil assignment system." (ibid.). Because

"Knoxville school children are assigned to schools on the

basis of their residence and without regard for their race,"

the district court finds no constitutional violation (A. 1671)

April 6, 1972, the court entered its Order denying the

relief sought by plaintiffs and declaring Knoxville to be a

unitary school system (A. 1672); May 1, 1972 an Order was

entered denying plaintiffs' request for an award of counsel

fees (A. 1673) and May 22, 1972, the court denied a motion

for new trial and/or to alter or amend the May 1 judgment.

(A. 1674). These appeals followed.

-2 5-

ARGUMENT

I

THE DISTRICT COURT’S FINDING THAT KNOXVILLE HAS A

UNITARY SCHOOL SYSTEM IS CONTRARY TO SWANN, OTHER

CONTROLLING DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT, THIS

COURT'S 1971 REMAND IN THIS CASE AND OTHER DECISIONS

OF THIS COURT; IT IS BASED UPON FAULTY FACTUAL PREM

ISES AND THE APPLICATION OF ERRONEOUS LEGAL STANDARDS

The Supreme Court's most recent school desegregation

opinions, Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) and United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of

Educ., 407 U.S. 484 (1972), concerned a different issue than

that before the Court in this case, but they are worthy of

note because the Court again summarized the standard by which

school board actions in desegregation cases are to be reviewed

. . . The mandate of Brown II was to

desegregate schools, and we have said

that "[t]he measure of any desegregation

plan is its effectiveness." Davis v.

School Commissioners of Mobile County,

402 U.S. 33, 37. Thus, we have focused

upon the effect— not the purpose or

motivation— of a school board's action

in determining whether it is a permissible

method of dismantling a dual system.

Wright, supra, 407 U.S. at 462.

The import of Davis and Swann had not been overlooked

by this Court. Whereas in considering this case in 1969, this

Court rejected the test of effectiveness, citing Deal v.

Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert.

-26-

24/

denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967), last year this Court recognized

that Swann and Davis undercut such an analysis:

Swann, 1971, forbids the use of our

decisions in Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of

Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert,

denied 389 U.S. 847, 88 S.Ct. 39, 19 L.

Ed.2d 114 and Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of

Ed., 419 F.2d 1387, cert, denied because

of late filing, 402 U.S. 962, 91 S.Ct.

1630, 28 L.Ed.2d 128, to justify a plan of

desegregation in a state which employed de

jure segregation until the Brown decision.

Goss v. Board of Educ., 444 F.2d 632, 639 (6th Cir. 1971).

The district court apparently understood this language only

in its most literal sense, for while the court was exceedingly

careful never to cite Deal in its opinion, 340 F. Supp. 711

(A. 1653), its approach and method of analyzing this case

remains wedded to Deal. As it has done for years whenever

there are proceedings in this case before it, the district court

ritualistically intones the words "Knoxville is a unitary system"

without regard to any realistic appraisal of either how the

law has changed, or how the school system has really not changed

very much at all since Brown.

The district court's errors are so abundant that it is

difficult to know where to begin. Perhaps the most striking

^/in 1969 this Court said:

. . . the fact that there are in Knoxville

some schools which are attended exclusively

or predominantly by Negroes does not by

itself establish that the defendant Board of

Education is violating the constitutional rights

of the school children of Knoxville. Deal . . . .

406 F.2d 1183, 1186 (6th Cir. 1969).

-27-

omission from the district court's opinion is its failure to

confront the fact that more than three-fifths of Knoxville's

students attend virtually all-one-race schools, i.e., schools

25/

which are 90% or more black or white. The closest the

district court comes to measuring the effectiveness of the

Knoxville desegregation plans is its finding (A. 1659) that

in 1970-71 and 1971-72 all of Knoxville's black students were

attending "integrated" schools (see X 9, A. 1520). That this

can hardly be considered a valid measure of desegregation is

revealed by the inclusion of Green Elementary (411 black, 1

white) as an "integrated" school (X 83, A. 1644).

In Northcross v. Board of Educ., No. 72-1630 (6th Cir.,

August 29, 1972)(slip op. at p. 4), this Court affirmed a

district court holding that Memphis' "neighborhood school" zone

plan had not resulted in a unitary system:

It is the defendant School Board's contention

that notwithstanding the fact that some 79%

of its schools have an essentially monolithic

racial structure it has satisfactorily cured

the violation of law involved in its past de

jure segregation and has, in fact, established

a unitary system. We cannot accept this

contention.

Likewise, in Knoxville, 79% of the school facilities have this

li^In view of the fact that Knoxville's overall student popu

lation is only 16.5% black, perhaps the 90% figure is inappropriate

In 1971-72, 58% of all Knoxville students attended schools

enrolling 95% or more of one race; 48% attended schools 97% or

more uniracial (X 83, A. 1644).

-28-

essentially monolithic racial structure — but the district

court held the system was unitary.

The district court was obviously aware of the weakness

of its analysis; if the amount of integration in the public

schools of Knoxville was sufficient, that would be the end of

the matter since "[t]he constitutional command to desegregate

schools does not mean that every school in every community must

always reflect the racial composition of the school system as

a whole," Swann, 402 U.S. at 24. But the district court went on

(A. 1659-61) to hold that the minimal desegregation in Knoxville

was justifiable on the basis of "the previously approved

neighborhood pupil assignment system" (A. 1661) because the

"zone lines for [the neighborhood] schools are reasonably drawn

and the racial composition of each school corresponds to the

27/

composition of its zone" (A. 1660). In so doing, the district

court again ignored this Court's interpretation of Swann when

this matter was last decided:

. . . While the existence of some all black

or all white schools is not struck down as

per se intolerable, school authorities will

have to justify their continuance by something

more than the accident or circumstance of

neighborhood.

Goss v. Board of Educ., supra, 444 F.2d at 638.

Equally significant, the district court's finding

27/ .— This is precisely the standard enunciated in Pea 1 which

may be applicable to school systems as to which no past history

of discrimination is shown.

-29-

that "the racial composition of the schools corresponds to

the residential patterns within each school zone" (A. 1661)

is one of many which are clearly erroneous on this record; to

the extent that the judgment below is dependent upon such

findings (it is difficult to tell), it is unsupportable.

The district court's general finding, quoted above, is

inconsistent with its own summary of the Austin-East situation

The pupil locator map discloses that 291

more white children attending City schools

live in the Austin-East Senior High School

zone than attend schools within the zone.

. . . Vocational transfers, however, do not

account for all the shortage. There are

indications that the balance can be found at

Holston High. No evidence was introduced

to show whether school registration procedures

include a determination that the registrant

resides within the appropriate attendance

zone. It is possible that transfer procedures

can be circumvented. The evidence is clearly

insufficient to explain the situation.

(A. 1661). In its subsequent discussion

of transfer policies, the district court

itself, stating: [t]here is no credible

Board's transfer policy is being used to

of the administration

again contradicted

evidence that the

promote segregation."

(A. 1667) .

Precisely the opposite was demonstrated at trial. The

most compelling evidence of abuse is the board's own X 82

(A. 1567-1643) dealing with Austin-East zone transfers by

white students. The district court found nothing untoward:

-30-

The Board introduced copies for the transfer

requests from Austin-East for the past three

school years. Dr. Stolee testified that

these requests demonstrated that the transfer

system had been used to promote segregation.

These requests do not indicate the applicant's

race, and the bulk of them are checked

"disapproved." It is not understood how Dr.

Stolee could reach his conclusion from this

exhibit.

(A. 1667-68). Here is what the exhibit shows: The forms

are all from white students (see master listing at A. 1567-70)

There are transfer requests from 51 students — some having

repeatedly sought transfers — in the Austin-East zone. Not

all of the students listed as having transferred at A. 1567-70

are represented in the transfer requests? their forms may have

been lost.

Of the 51 students, 20 of their latest requests were

approved and 29 were denied; the other two students had sub

mitted forms unnecessarily after changing their addresses

and moving into another zone. Only six of the twenty-nine

white students whose requests to transfer out of Austin-East

were denied remained at the school: LaVerne Cox, Mary Green,

Miriam Kenimer, Larry Patty, Alan Rogers, Eursal Payne. 8

whites whose transfer forms are marked "disapproved" are shown

on the master listing as having obtained transfers and

subsequently been graduated from Fulton, Holston or Rule.

Among these, incredibly enough, is one Brenda Keeling (A. 1597

98); in the winter of 1967 Miss Keeling's request to transfer

-31-

from East to Rule

Because of the colored. They are a

colored boy that is causing trouble

in a way which I don't improve of;

causing talk [A. 1598]

was denied. In the spring of 1968 another

request to transfer, this time from East to Fulton because of

the "racial situation" (A. 1597) was disapproved. Yet the

school system reports (A. 1567) that Miss Keeling was a

Holston graduate! Another example is Miss Becky Suffridge

(A. 1634), who sought a transfer because she was "socially

deprived." Although it was denied, she is listed (A. 1567)

as a Fulton graduate.

Some of the approvals are equally interesting. Two were

granted because of racial complaints (Larry and Vicki Pickens,

A. 1617-20). Five other transfer requests were granted despite

previous disapprovals of the same or similar transfer pleas.

For example, Eddie Parton first sought transfer in early 1968

on the ground that it was inconvenient for him to attend East

(A. 1612); his request was denied. In late spring, 1968, he

again sought to change schools because of "emotional difficulty

in adjusting to a specific school situation" (A. 1611) (a

phrase which appears with annoying regularity on many transfer

forms). That was denied, and in August, 1968 he filed another

request to transfer to Fulton because he "wants to learn a

-32-

trade" (A. 1610). This request was also denied, but a school

official wrote on the form, the words "What Trade?" Finally,

on September 4, 1968 Parton got the message, requested transfer

so as to take "machine shop," which was not offered at Austin,

and was granted his transfer (A. 1609). James Dockery was

denied a vocational transfer in the summer of 1967, appealed

to the school board and lost (A. 1588); yet the following

winter he was granted a vocational transfer (A. 1587).

We have gone into this matter in some detail not simply

because transfers from Austin-East have been a bone of contention

in this case ever since the schools were paired, but also

because it is a good demonstration of the district court's

facility for ignoring the evidence when convenient. For

example, the court condemns Dr. Stolee's failure to prepare his

plan from the pupil locator map and computer print-outs

prepared by the board ("Dr. Stolee's failure to use this data

substantially reduces the weight of his testimony" [A. 1663]).

Yet the district court itself found that the locator map was

3000-4000 pupils below actual enrollment in this 34,000 pupil

system (A. 1655) and the Court seems to forget that Dr. Trotter,

who developed the Board's plan, also did not use the pupil

locator map because he regarded it as inaccurate (A. 413-14).

Given such discrepancies, it is evident that this Court will

be unable to decide this matter on the lower court's findings.

-33-

If the district court's fact finding is suspect, its

legal conclusions are also flawed and in conflict with governing

law. The school board did not even consider a transportation

plan, or noncontiguous zoning or pairing, because it would

cost money to establish a bus system and because they felt

the community was opposed to it (A. 610, 618). Not only Swann

and Davis, but this Court's opinion in this case last year

require "[cjonsideration of pairing of school zones, contiguous

or non-contiguous," 444 F.2d at 638. Yet the district court

did not require such, because it held, (a) on the basis of a

convoluted geography lesson, that Knoxville is distinguishable

from Mobile (A. 1656), and (b) a plan utilizing pupil transpor

tation would place an extreme fiscal burden on the school system.

As to the former conclusion, this is clearly insufficient

justification for continued segregation. Under the dual school

system, black students from all over the city travelled to

Austin, for example, apparently without undue hardship.

Barriers which did not prevent enforced

segregation in the past will not be held

to prevent conversion to a full unitary

system.

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist., 433 F.2d

387, 394 (5th Cir. 1970). As to the financial plight of the

school board and city, not only is the evidence conflicting

(see pp. 21-23 supra) but the projected cost of busing, even

accepting the district court's statement that "Dr. Stolee

-34-

grossly understated the actual amount of bussing [sic]

and the distances involved in his plan" (A. 1666) and using

Dr. Bedelle's highest estimate (A. 1669), is well within allowable

levels of expenditure as a percentage of the total school

budget approved in Swann. See Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk,

456 F.2d 943, 947 n.6 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 905

(1972); United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

Dist., 460 F.2d 1205 (5th Cir. 1972); Brown v. Board of Educ.

of Bessemer, 464 F.2d 382 (5th Cir. 1972). Any attempt to

distinguish Swann because Knoxville does not at present furnish

transportation except pursuant to the annexation agreement

(A. 1669) must also fail? the Charlotte school system was

required by the district court's desegregation order to enlarge

it3 transportation system by adding far more new vehicles and

personnel than will be required in Knoxville.

The district court's dissatisfaction with the Stolee plan

as a "workable alternative to the Board's plan" (A. 1666) is

certainly no ground for approving a scheme which uses no

technique except minor zone alterations and two contiguous

pairings. At the least, the court should have instructed the

school board to submit another plan. Knoxville has no immunity

from being required to use "any of the tools of modern life

in carrying out [the] constitutional mandate." Kelley v.

Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 463 F.2d 732, 746-47 (6th

-35-

28/Cir. 1972).

The district court also accepted Dr. Bedelle's contention

that effective desegregation, through busing, in Knoxville

would curtail student participation in extracurricular activ

ities (A. 1666). Swann recognizes that the process of desegre

gation will resul t in some awkwardness and inconvenience, 402

U.S. at 28; the Supreme Court clearly limits those circumstances

which will excuse failure to desegregate to plans under which

"the time or distance of travel is so great as to either risk

the health of the children or significantly impinge upon the

educational process." 402 U.S. at 30-31. Defendants did not

attack specific pairings or groupings on this basis, however,

but opposed any and all pupil transportation (except that

required by the annexation agreement). Furthermore, it is well

within defendants' power to avoid some of these practical

problems as, for example, by scheduling extra “late" bus runs

for students participating in extracurricular activities, as

many school systems have done. Cf. Bradley v. School Bd. of

Richmond, 325 F. Supp. 828, 847 (E.D. Va. 1971).

28/The decision of the district court below cannot be upheld

on the basis of this Court's recent decision in Mapp v. Board

of Educ. of Chattanooga, Nos. 71-2006, -2007, 72-1443, -1444

(6th Cir., October 11, 1972). While the panel majority in that

case did not indicate that substantial desegregation must be

achieved on remand through the use of busing, if necessary, it

did recognize, unlike the court below, that more had to be done.

"In our judgment the mere fact that the District Court at one

time considered the Board of Education in compliance, did not

preclude the Court from holding otherwise when considering the

case in light of more recent decisions" (slip op. at p. 11).

-36-

II

The District Court Erred In

Approving The School Board's

Proposal To Close A Black

Elementary School Without A

Showing That Discontinuation

Was Required For Non-Racial Reasons

The district court approved, and permitted implementation

of, modifications to the school board's desegregation plan

including the discontinuation of the Cansler Elementary school,

a formerly black school, for regular instructional purposes.

The court did so without any showing by the board that there

were justifiable, non-racial reasons for this step. Indeed,

the evidence in the record suggests the opposite. Cansler

is a relatively new facility (A. 203), but the author of the

board's plan, Dr. Trotter, made no comparison of its age or

adequacy with adjacent, but predominantly white schools (such

as West View or Beaumont, to which Cansler pupils are sent)

when he decided to recommend its closing (A. 478). It is also

significant that in questioning Dr. Stolee about his plan,

which would retain Cansler (and also a white school, Moses,

which Trotter also proposed to shut down), the school board

attorney sought justification for retaining Moses only (A. 1421)

Twice as many black schools as white schools have already

been closed since this litigation commenced (X 8, A. 1518),

and in light of the board's reliance upon community opinion

-37-

as a justification for the kind of desegregation measures

it takes (A. 618), it is evident that Cansler was closed rather

than having had white student assigned to attend it.

Numerous courts have held desegregation plans unconstitu

tional when they unfairly discriminate against black students

either by forcing them to bear a disproportionate share of the

required transportation or by closing a disproportionate number

of formerly black schools. E.g., Brice v. Landis, 314 F. Supp.

974, 978 (N.D. Cal. 1969); Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburq Bd.

of Educ., 328 F. Supp. 1346 (W.D.N.C. 1971); Lee v. Macon County

Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971); Haney v. County Bd.

of Educ., 429 F.2d 364, 371-72 (8th Cir. 1970); Bell v. West

Point Municipal Separate School Dist., 446 F.2d 1362 (5th Cir.

1971); Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg, 444 F.2d 99

(4th Cir. 1971), aff1q Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke, 316 F.

Supp. 6 (W.D. Va. 1970); Smith v. St. Tammany Parish School Bd.,

302 F. Supp. 106, 108 (E.D. La. 1969).

The cases which have approved black school closings have

done so on the ground that the deteriorated physical condition

of the buildings required their closing, and thus that black

students bore no special burdens of desegregation thereby. E.g.,

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 382 (5th Cir.

1970); Chambers v. Iredell County Bd. of Educ., 423 F.2d 613

-38-

(4th Cir. 1970). But evidence must be adduced and district

courts must make specific findings of fact and conclusions of

law justifying such closings, e.g., Gordon v. Jefferson Parish

School Bd., 446 F.2d 266 (5th Cir. 1971).

Because the school board made no showing, and the district

court made no findings on the subject, we submit that the court

erred in permitting the closing of Cansler for regular instruc

tional programs. Additionally, we urge the Court to require

a compelling justification to be shown before the lower court

is authorized to permit such a step. See Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Bd. of Educ., supra, 453 F.2d at 751 (McCree, J., concurring)

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., No. 71-1966 (6th Cir.,

September 21, 1972) (McCree, J., dissenting).

-39-

Ill

The District Court Should Have Awarded

Attorneys' Fees And Litigation Expenses

To The Plaintiffs

A. An Award Is Required Under Traditional Equitable Principles

The district court summarily denied plaintiffs' motion

for an award of attorneys' fees and taxation of costs and

expenses, even though it is absolutely clear that any desegre

gation which has occurred in Knoxville has resulted from plaintiffs'

vigorous prosecution of this suit (see Appendix A, n. 2).

«Plaintiffs in this action are but nominal petitioners on

behalf of all students. They could not be and should not be

29/

expected to finance these proceedings from their own resources.

The investigation, research and presentation of expert and fact

witnesses require the expenditure of tremendous amounts of time

29/The Court should not be misled, by the fact that plaintiffs'

attorneys are assisted in this case by salaried attorneys of a

non-profit organization (the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.) into believing either that unlimited funds are avail

able to support this lawsuit or that a counsel fee award is

inappropriate in these circumstances. As to the former, it

suffices to say that the Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit

corporation supported mainly by public contributions. It is

involved in a wide variety of litigation, including more than

one hundred fifty school desegregation cases, at enormous cost.

Last year, the Legal Defense Fund operated at a $250,000 deficit.