Greenberg Remarks on The Crisis in American Justice Conference with Chief Justice Warren

Press Release

May 15, 1970

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Greenberg Remarks on The Crisis in American Justice Conference with Chief Justice Warren, 1970. 3268a31c-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce115295-a698-44d7-90a0-e45294f9694d/greenberg-remarks-on-the-crisis-in-american-justice-conference-with-chief-justice-warren. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

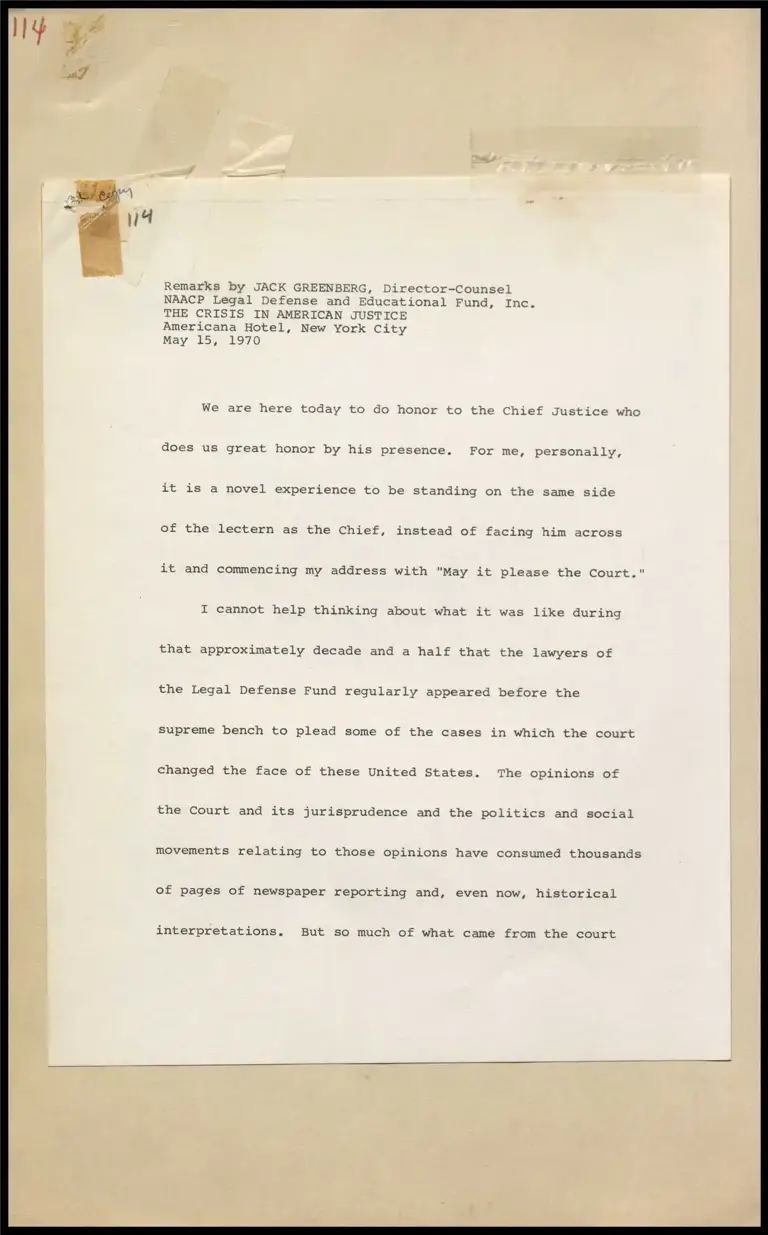

Remarks by JACK GREENBERG, Director-Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

THE CRISIS IN AMERICAN JUSTICE

Americana Hotel, New York City

May 15, 1970

We are here today to do honor to the Chief Justice who

does us great honor by his presence. For me, personally,

it is a novel experience to be standing on the same side

of the lectern as the Chief, instead of facing him across

it and commencing my address with "May it please the Court."

I cannot help thinking about what it was like during

that approximately decade and a half that the lawyers of

the Legal Defense Fund regularly appeared before the

supreme bench to plead some of the cases in which the court

changed the face of these United States. The opinions of

the Court and its jurisprudence and the politics and social

movements relating to those opinions have consumed thousands

of pages of newspaper reporting and, even now, historical

interpretations. But so much of what came from the court

can in microcosm be seen in the conduct of the hearings

of the cases by Chief Justice Warren.

During the questioning of counsel in which the Justices

seek to elicit the facts and understand the arguments of

both sides, he would frequently conclude a colloquy by

looking a lawyer in the eye and asking, "Yes I understand

your position, but is that fair?"

One may argue, and there is no shortage of legal

philosophers who have argued, that this inquiry is not

sufficiently legalistic. But in the Supreme Court, which

makes the supreme law of the land, one issue of overwhelming

concern is whether legal rules comport with the sense of

fairness of the times. This is no novel perception, having

been pointed out by Justice Cardozo long ago. Many a lawyer

wilted under the question "Is that fair." It took a particular

bravado and considerable circumlocution for counsel to assert

the fairness of a position in which he did not really believe.

Recently I have been looking at the transcripts of some

arguments before the Court and would like to share with you

some sense of how the Chief extracted the moral essense of

the legal questions before the Court. In the original

School Segregation Cases - on the issue of how to implement

the court order - he interrogated counsel for the State of

South Carolina as follows:

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: But you are not willing

to say here that there would be an honest attempt

to conform to this decree, if we did leave it to

the district court?

MR. ROGERS: No, I am not. Let us get the

word "honest" out of there.

THE CHIEF JUSTICE: No, leave it in.

MR. ROGERS: No, because I would have to tell

you right now we would not conform--we would not

send our white children to the Negro schools.

One can imagine how the court was impressed with arguments

about "good faith" after retorts of that sort.

And only two years ago, in the 'freedom of choice' cases,

he referred to the same theme of "honesty."

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN: Isn't the experience

of three years in that county, where there never has

been a white child go to a Negro school, isn't that

some indication that it was designed for the purpose

of having a booby trap for them, that they couldn't

didn't dare to go over?

MR. GRAY: . . . [I]£ integrated education is

what the colored plaintiff wants, I can provide it

for him this morning, if he is in the room. He

need only sign that form and check the New Kent

School, and he will have a fully integrated

education.

MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN: When you say to us

that there are no community attitudes that pervade

that county, which would militate against the Negro

child saying that he wanted to go to the white

school, can you say that to us honestly?

Politicians may tell tall tales, but there is no doubt

that the Justices knew what the score was.

Of course, we all know, and the Chief Justice will be

the first to say, that decisions of the Warren Court were

the decisions of a court consisting of nine justices. But

during his tenure, while the identities of his associates

changed somewhat from time to time, the direction of that

court remained the same. And the Chief's views on questions

of human liberty were a constant which characterized the

Court's decisions. Our dear friend and frequent collaborator

at the Legal Defense Fund, Professor Charles Black of Yale,

has recently given a series of lectures on the Warren Court,

which better than anything else sums up its achievement.

I would like to read some excerpts from those lectures:

There is only one thing I would say confidently,

now, about the Warren Court. It is the only Court

so far in American history which has so much as a

chance of being one day thought as great as the

Marshall Court, for it is the only Court that has

made an assertion as large as the Marshall Court

made. Marshall took a set of disconnected texts

and read them together in the light of an overall

vision of nationhood. The Warren Court .. . has

insisted that these guarantees, readable in them-

selves, in their radiations, and in their interstices,

are to be looked on as forming a total scheme of

citizenship. The Warren Court . . . perceived in

these guarantees a pervading systemic equity, and

equity of respect for the citizen, and thus set in

full motion a way of looking at them which can

make of their totality a plan adequate in shape

and size, to confront Marshall's plan of nationhood.

* * *

I think it plain that we will not be or

remain a nation unless we plant ourselves on the

moral ground to which the Warren Court has given

its outlines . . . We need this moral basis of

citizenship -- common, growing citizenship -- as

we need cleaner water and air.

The decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which is

in my view the Court's largest contribution to that vision

of citizenship, was, of course, handed down in response to

cases brought by the Legal Defense Fund. We have since

then devoted ourselves to implementing its vision in many

ways, acting to extend it to housing, employment and public

accommodations to all citizens and to see that all are treated

alike without regard to race or poverty.

Now the Legal Defense Fund is undertaking a new and much

needed effort, and that is to extend, particularly in the

South, the number of Negro lawyers who are trained in civil

rights, so that the theoretical victories can be made into

pervasive reality.

Today only 1% of the lawyers and law students in the

United States are Negro. There is only one black lawyer for

every 7,000 black Americans and in the South and Southwest

the ratio is one to 37,000. The comparable national figure

for white persons is one to every 637. We are undertaking

a program which over the next 5 years will add enough black

lawyers to those who normally would be expected to graduate

from law school to double the number of black lawyers in

the nation and more than double the number in the South, i.e.

1500 law school scholarships. Of these we will select more

than 200 to be interns in our offices or the offices of our

cooperating attorneys and develop special expertise in civil

rights so valuable, particularly in this day when the federal

government is cutting back on its civil rights enforcement.

Moreover, we plan to increase the number of our Lawyers

Training Institutes available to still other members of the

Bar to enhance the capacity of the private civil rights sector.

We plan to do this while maintaining our current litigation

program. And that means a 60% increase in budget or more

than $16 million to be spent over the next three years.

These are difficult enough times for those of us who

believe in human rights. Bishop Moore at the opening of this

session mentioned the tragic death of Walter Reuther. We

thought that some small recognition of his steady and

unfailing dedication might be commemorated by naming one

of the law school scholarships after him and this we intend

to do.

We had wondered, since this is a luncheon in honor

of the Chief Justice, whether to present him with a plaque

or a scroll or any of the conventional artifacts ordinarily

handed out on such occasions. But we concluded that probably

he had a closet full of them and another would make no real

difference beyond the expression of our esteem and love.

We do hope, however, that he takes some satisfaction in the

naming of the law school scholarship after Walter Reuther

his devoted friend and admirer whom he admired so profoundly.

And now, I present to you Mr. Chief Justice Earl Warren.