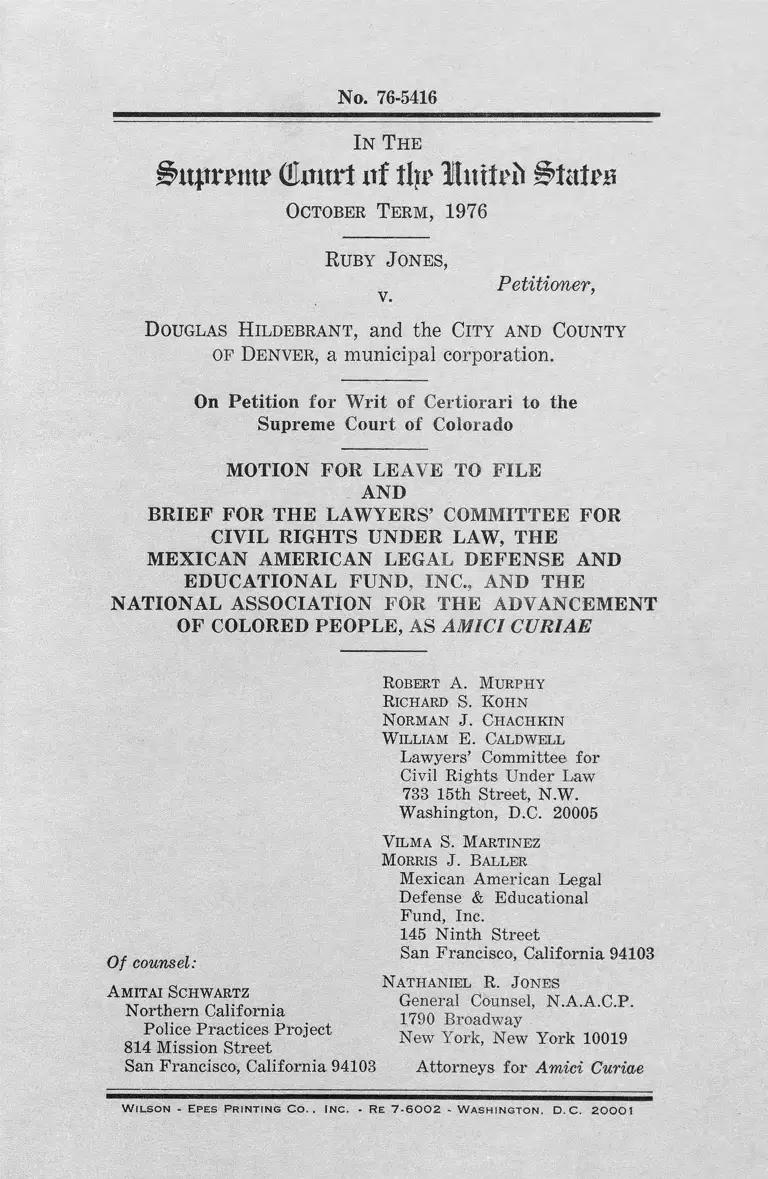

Jones v. Hildebrant Motion of Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Hildebrant Motion of Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1976. 4dcf2d4d-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce3d342f-1920-4e8e-93de-b4765ec97a1d/jones-v-hildebrant-motion-of-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

No. 76-5416

In The

&npran? (tart of tljr luttrii §tatra

October Term, 1976

Ruby J ones,

Petitioner,

Douglas H ildebrant, and the City and County

OF Denver, a municipal corporation.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Colorado

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

AND

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, AS AMICI CURIAE

Robert A. Murphy

Richard S, Kohn

Norman J. Chachkin

William E. Cat,dwelt.

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Vilma S. Martinez

Morris J. Baller

Mexican American Legal

Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Nathaniel R. J ones

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

San Francisco, California 94103 Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Of counsel:

Amitai Schwartz

Northern California

Police Practices Project

814 Mission Street

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - R e 7 - 6 0 0 2 - W a s h i n g t o n , d . c . 2 0 0 0 1

In The

£>upttm Court of % luttrib ̂ tatro

October Term, 1976

No. 76-5416

Ruby J ones,

Petitioner,

v.

Douglas H ildebrant, and the City and County

of Denver, a municipal corporation.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Colorado

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

Amici curiae Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law, Mexican American Legal Defense & Educa

tional Fund, Inc., and National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People respectfully seek leave to

file the attached brief in order to assist the Court in

resolving important issues affecting the right to recover

meaningful damages in actions brought pursuant to 42

U.S.C. § 1983 to redress unconstitutional police miscon

duct causing death. In the attached brief, amici discuss

several underlying questions which are critical to the

(1)

(2)

disposition of this cause but which amid do not believe

will be addressed by the parties.

The interest of amid in this case grows out of their

longstanding concern with the problem of devising reme

dies that will secure the effective enforcement of federal

civil rights laws, and in particular their past and present

involvement in litigation on behalf of minority citizens

who have suffered injury or death at the hands of police

officers.

Amid have sought consent to the filing of this brief

but such consent has been refused by counsel for Re

spondents.

WHEREFORE, amid respectfully move that their

brief be filed in this case.

Respectfully submitted,

Of counsel:

Amitai Schwartz

Northern California

Police Practices Project

814 Mission Street

San Francisco, California!

Robert A. Murphy

Richard S. Kohn

Norman J. Chachkin

William E. Caldwell

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights, Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Vilma S. Martinez

Morris J, Baller

Mexican American Legal

Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94103

Nathaniel R. J ones

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................... ........... in

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ______ ___________ 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...................................... 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............ ........................ 8

ARGUMENT

I. The Colorado Courts Properly Entertained This

§ 1988 Suit, Though They Were Required To

Apply Federal Law In Determining Its Out

come. _________________ ____ ______________ 11

II. Civil Actions May Be Maintained Under 42

U.S.C. § 1983 By Persons, Such As Petitioner

Here, Who Seek To Redress Unconstitutional

State Action Resulting In Human Death. ____ 18

A. Section 1983 Creates A Constitutional Cause

of Action Wholly Apart From State Tort

Law. __________________ _______________ 20

B. In § 1983 Death Cases The Courts Are Au

thorized, Both By General Principles Of

Federal Remedial Law And By 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988, To Utilize State Wrongful-Death

Statutes. __________________ ___________ 31

III. Restrictive State Damage Rules, Such As Colo

rado’s “Net Pecuniary Loss” Limitation, Are

Inapplicable When Incompatible With Interests

Protected By § 1983. ___ __ ________________ 36

A. Complete Justice And Deterrence of Uncon

stitutional Conduct Are The Twin Goals of

§ 1983. ______________ _______________ 36

B. The “Net Pecuniary Loss” Rule Negates The

Purposes of § 1983. ______ __ _________ _ 38

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

n

C. Uniform Federal Rules of Recovery Are Re

quired Even Where State Wrongful-Death

Statutes Are Utilized........... ............................. 40

IV. If the State Wrongful-Death Act Must Be Ap

plied in its Entirety, Then This Court Should

Reject the State Law Approach Altogether and

Create a Federal Common Law of Survival and

Wrongful Death Under § 1983. .............. -........ 44

CONCLUSION .... ................................................................. 50

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Rage

Adickes V. S. H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970).. 20, 27,

36, 37, 38, 40, 49

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ............................................. ....................... . 37,38

Aidinger V. Howard, 96 S. Ct. 2413 (1976) ....11,14, 22n

A /S J. Ludwig Mowinckels Rederi v. Dow Chem

ical Co., 25 N.Y.2d 576, 255 N.E.2d 774, 307

N.Y.S.2d 660, cert, denied, 398 U.S. 939 (1970).. 43n

Atchison, T.&S.F. Ry. v. Sowers, 213 U.S. 55

(1909) ........................................................................ 2,On

Bailey V. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962)...... ........ . 35n

Baker v. Bolton, 1 Camp. 493, 170 Eng. Rep. 1033

(1808) ............................................................ ......_..28n, 29n

Baker v. F.&F. Investment Co., 420 F.2d 1191 (7th

Cir.), cert, denied, sub nom. Universal Builders

Inc. V. Clark, 400 U.S. 821 (1970) .... ................ 27n

Bartch v. United States, 330 F.2d 466 (10th Cir.

1964) _________ ___ ________ __________ ____ 38n

Basham v. Smith, 149 Tex. 297, 233 S.W.2d 297

(1946) ..................................................... 43n

Basista v. Weir, 340 F.2d 74 (3d Cir. 1965)....... _..38n, 40

Bell V. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946)______________ 23, 37

Bemis Bros. Bag Co. V. United States, 289 U.S.

28 (1933) ________________ 37

Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, 403 U.S.

338 (1971) ............ ........... ............. .................... . 48

Blue V. Craig, 505 F.2d 830 (4th Cir. 1974)...... . 12n

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F.2d 401 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 368 U.S. 921 (1961)____________ 19n, 24, 25n

Brown V. Balias, 331 F. Supp. 1033 (N.D. Tex.

1971) ................................ 42n

Brown v. Gerdes, 321 U.S. 178 (1944)________ 13n, 15n

Caperci V. Huntoon, 397 F.2d 799 (1st Cir.), cert.

denied, 393 U.S. 940 (1968) ___ ___________ 38n

Carey v. Berkshire Railroad, 55 Mass. (1 Cush.)

475, 48 Am. Dec. 616 (1848) ________________ 29n

Chamberlain V. Brown, 442 S.W.2d 248 (Tenn.

1969) 12n

IV

Charles Dowd Box Co. V. Courtney, 368 U.S. 502

(1962) ............. ..................................................14,15,16,17

Cinnamon V. Abner A. Wolf, Inc., 215 F. Supp. 833

(E.D. Mich. 1963) ..................................................... 19n

Claflin V. Houseman, 93 U.S. 130 (1876)____ 13n, 15,17

Clearfield Trust Co. V. United States, 318 U.S.

363 (1943).... .................................. .......... ........... . 31,48

Clint V. Stolworthy, 144 Colo. 597, 357 P.2d 649

(1960) _____________________ ___ ________ 30n

Davis V. Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572 (N.D. 111.

1955) ____ ___________ ________ ___________ 19n, 24n

Dellariya V. Ne wYork, N.H. & H.R.R., 257 F.2d

733 (2d Cir. 1958) ___________ 31n

Dennick V. Central Ry., 103 U.S. 11 (1880) _____ 30n

District of Columbia V. Carter, 409 U.S. 418

(1973) __________ 16n

Douglas V. New York, N.H. H.R.R., 279 U.S.

377 (1929) .____ ______________ __________ 13n

Dudley V. Bell, 50 Mich. App. 678, 213 N.W.2d

805 (1973) .............................................. 43n

Erie R.R. V. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938) ____ 48

Evain V. Conlisk, 364 F. Supp. 1188 (N.D. 111.

1973), aff’d 498 F.2d 1403 (7th Cir. 1974)........ 19n

Farmers Educ. Cooperative Union V. WDAY, 360

U.S. 525 (1959)___________________________ 17n, 48

Fish V. Liley, 120 Colo. 156, 208 P.2d 930 (1949).. 7n

Garner V. Teamsters, C. & H. Local Union, 346

U.S. 485 (1959) ......... 15n

Garrett V. Moore-McCormack Co., 317 U.S. 239

(1942) .............. 17n

Griffin V. Breckenridge, 402 U.S. 88 (1971)_____ 25n

Hall V. Wooten, 506 F.2d 564 (6th Cir. 1974) ......19n, 25n

Holmberg V. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392: (1945)....... 48

Illinois V. City of Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91 (1972).. 48

Imbler V. Pachtman, 424 U.S. 409 (1976) .... ....... 41

Jackson County V. United States, 308 U.S. 343

(1939) ....... 49

James V. Murphy, 392 F. Supp. 641 (M.D. Ala.

1975) .................. ..................................................... 19n, 41n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

y

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Jerome V. United States, 318 U.S. 101 (1959)__ 45

J. I. Case Co. V. Bordk, 377 U.S. 426 (1964) ___ 48

Jones V. Hildebrant, 550 P.2d 339 (Colo. 1976)__4n, 5, 8,

30n,35n,38

Local 17h V. Lucas Flour Co., 369 U.S. 95 (1962)..17, 42n,

48

Lynch V. Household Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538

(1972) ......................... - ________ _____________ 16n

Marbury V. Madison, 1 Cranch (U.S.) 137

(1803) _____ ___________ ___ _______________ 37

Mattis V. Schnarr, 502 F.2d 588 (8th Cir. 1974).... 19n

McAllister V. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 357 U.S.

221 (1958)....... ............ ............ ...............................17n, 48

McKnett V. St. Louis & S.F. Ry., 292 U.S. 230

(1934) .............................................. ............ ........ 13n

Missouri ex rel. Southern Ry. V. Mayfield, 340

U.S. 1 (1950) _____ ___ ____________ ________ 13n

Mitehum V. Foster, 408 U.S. 225 (1972) _______ 16n

Mobile Ins. Co. V. Brame, 95 U.S. 754 (1878) .....28n, 30n

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ______ 12,16n, 20,

24, 26n

Moor V. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973).. 18n,

34, 42n

Moore V. Backus, 78 F.2d 571 (7th Cir. 1935)____ 28n

Moragne V. States Marine Lines, Inc., 398 U.S.

375 (1970) ____ __ ......18n, 27, 35, 39, 42, 45, 46, 47, 48

National Metropolitan Bank V. United States, 323

U.S. 454 (1945) ________ ___________________ 48

Paul V. Davis, 424 U.S. 693 (1976) __________6, 7n, 20

Perkins V. Salafia, 338 F. Supp. 1325 (D. Conn.

1972) ........................................................................... 19n

Pritchard V. Smith, 289 F.2d 153 (8th Cir. 1961).. 19n

Publix Cab Co. V. Colorado Nat’l Bank of Denver,

139 Colo. 205, 338 P.2d 702 (1959)..................... 19n

Rhoads V. Hovat, 270 F. Supp. 307 (D. Colo.

1967) ______ _________ __ _____-----................ 38n

Riley V. Agwilines, Inc., 296 N.Y. 402, 73 N.E.2d

718 (1947) 43

VI

Rogers V. Douglas Tobacco Bd. of Trade, 244 F.2d

471 (5th Cir. 1957) ..__ ____________________ 31n

Romero V. International Terminal Operating Co.,

358 U.S. 354 (1959)________ ___ ____________ 28n

Rue V. Snyder, 249 F. Supp. 740 (E.D. Tenn.

1966) ____________________ _____________ __ 22n

Runyon V. McCrary, 96 S. Ct. 2978 (1976) ____ 33n

SalazarV. Dowd, 256 F. Supp. 220 (D. Colo. 1966).. 19n

San Diego Building Trades Council V. Garmon,

359 U.S. 236 (1953) ___ ____ __________ _____ 15n

Scheuer V. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974)_______ 18n, 24n

Screws V. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945)___ 6n

Sea-Land Services V. Gaudet, 414 U.S. 573 (1974).. 18n,

22n, 39, 43, 48

Second Employers’ Liability Cases (Mondou V.

New York, N.H. & H.R.R.), 223 U.S. 1 (1912).. 13n

Shaw V. Garrison, 545 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1977)._19n, 42n

Shaw V. Garrison, 391 F. Supp. 1353 (E.D. La.

1975), aff’d 545 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1977)____ 21

Smith V. Wickline, 396 F. Supp. 555 (W.D. Okla.

1975)____________________________________ 19n, 35n

Sola Electric Co. V. Jefferson Electric Co., 317

U.S. 173 (1942) _______________ ____________ 49

Spence V. Staras, 507 F.2d 554 (7th Cir. 1974)._19n, 38n,

39-40

Steffel V. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974)______ 16n

Stringer v. Dilger, 313 F.2d 536 (10th Cir. 1963).. 22n

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229

(1969) _________________________ 17n, 32n, 34, 37, 42

Swift V. Tyson, 16 Pet. (U.S.) 1 (1842)________ 30n, 48

Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367 (1951)_____ 41

Testa V. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947) ____________ 13n

Textile Workers Union V. Lincoln Mills, 363 U.S.

448 (1957)_____ ____ ____________ '.......14,15,18,48

The Harrisburg, 119 U.S. 199 (1886)__________ 42n, 46

The Tungus V. Skovgaard, 358 U.S. 588 (1959).... 27, 42,

48

Tunstall V. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen

& Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210 (1944)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

48

VII

United States V. Standard Oil Co., 332 U.S. 301

(1947) . ____ ______ _ __ _____________ 31

Van Beech V. Sabine Towing Co., 300 U.S. 342

(1936) -----------------------------------------------------32n, 46n

Wicker V. Hoppock, 6 Wall. (U.S.) 94 (1867)___ 37

Woodson V. North Carolina, 96 S. Ct. 2978 (1976).. 35n

Zwickler V. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967)_________ 16n

Constitution and Statutes

U.S. Const., 14th Amendment (1868)_________ passim

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) ______________ _______ 11, 12n, 16

28 U.S.C. § 1652 ____________________ _______ 42n

42 U.S.C. § 1983 --------------------------------------------passim

42 U.S.C. § 1985 _______________________ ____ 25n

42 U.S.C. § 1986 _____________________________25, 26n

42 U.S.C. § 1988 -------------------7, 19, 31, 32, 33, 34, 38, 41

P.L. 94-559, Civil Rights Attorneys’ Fees Awards

Act of 1976, 90 Stat. 2641 ________________ _ 33n

Judiciary Act of 1789 __________________ ______ 16

Labor Management Relations Act of 1947______ 14,16

Force Act of 1871, 16 Stat. 433 ______________ 28n

Ku Klux Act of 1871, 17 Stat. 13_________ __ _passim

Enforcement Act of 1870, 16 Stat. 140 ________28n, 33n

Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866, 14 Stat. 2 7 ___ 32, 33n

Rev. Stat. § 722 _______________ ____________ 33n

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-20-101 (1973) __________ 19n

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-21-201 (1973) ___________ 29n

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-21-202 (1973) __________ 4n, 19n

Rules

Supreme Court Rules 23(1) ( c ) ______________ 5

Supreme Court Rules 40(d) (1) ____ ________ 5

Other Authorities

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st S ess.____________ 23

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess-----------12n, 23, 24, 26n,

28,31

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

vin

P. Bator, P. Mishkin, D. Shapiro and H. Wechs-

ler, The Federal Courts and the Federal

System (2d ed. 1973) _______ _____________ 48n

Black’s Law Dictionary (4th ed. 1957)____ __ 28n

2 F. Harper & F. James, Law of Torts (1956).... 18n

C. McCormick, Handbook on Damages (1935)-. 18n,

48n

W. Prosser, Law of Torts (4th ed. 1971) ____19n, 24n,

41

Friendly, In Praise of Erie—and of the New Fed

eral Common Law, 39 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 383

(1984) ______ ____ ___________ ____________ 48n

Malone, American Fatal Accidents Statutes—

Part I : The Legislative Birth Pains, 1965 Duke

L.J. 673 _________________ ________________ 29n

Malone, The Genesis of Wrongful Death, 17 Stan.

L. Rev. 1043 (1965)_______________ _____ ...19n, 29n

Monaghan, The Supreme Court, 1974 Term—

Forward: Constitutional Common Law, 89 HARV.

L. Rev. 1 (1975)......... ................ ............ ............... 44-45

Niles, Civil Actions for Damages Under the Fed

eral Civil Rights Statutes, 45 Tex. L. Rev. 1015

(1967) __________________________________22n, 42n

Page, State Law and the Damages Remedy Under

the Civil Rights Act: Some Problems in Fed

eralism, 43 Den. L.J. 480 (1966) ________22n, 39, 42n

Pound, Comment on State Death Statutes—Appli

cation to Death in Admiralty, 13 NACCA L.J.

188 (1954) ....................... .... ...................... ............ 48n

Smedley, Wrongful Death—Bases of the Common

Law Rules, 13 Vand. L. Rev. 605 (1960)_____ 28n

Theis, Shaw v. Garrison: Some Observations on

42 U.S.C. § 1988 And Federal Common Law, 36

La. L. Rev. 681 (1976)___________ _________ 41, 42n

Note, Federal Common Law, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1512

(1969) _________ ____________________ _____ 45

Note, Survival of Actions Brought Under Federal

Statutes, 63 Colum. L. Rev. 290 (1963)............. 34

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

In The

Bnpmnt (Emir! xif % Htttfrii States

October Term, 1976

No. 76-5416

Ruby Jones,

Petitioner,

Douglas Hildebrant, and the City and County

of Denver, a municipal corporation.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Colorado

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, AS AMICI CURIAE

Interest of Amici Curiae

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President

of the United States, John F. Kennedy, to involve pri

vate attorneys throughout the country in the national

effort to assure civil rights to all Americans. The Com

mittee’s membership today includes two former Attorneys

General, nine past Presidents of the American Bar

Association, two former Solicitors General, a number of

law school deans, and many of the nation’s leading law

yers. Through its national office in Washington, D.C.

and its offices in Jackson, Mississippi and eight other

cities, the Lawyers’ Committee over the past fourteen

years has enlisted the services of over a thousand mem

bers of the private Bar in addressing the legal problems

of minorities and the poor in voting, education, employ

ment, housing, municipal services, the administration of

justice, and law enforcement.

The Lawyers’ Committee has been intimately involved

in litigation on behalf of minority-race persons seeking

redress for unconstitutional police conduct, especially the

use of excessive physical force, including deadly force.

This litigation has been based principally upon 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983, which derives from the Ku Klux Act of 1871.

The Committee’s experience is that broad principles of

relief are essential to the fulfillment of that statute’s

goals. In particular, the rules of damages applicable to

§ 1983 litigation must not only assure complete com

pensation for personal injuries resulting from the un

justified use of excessive force by police officers; the

rules must also assure that, in appropriate circumstances,

exemplary damages will be awardable. The realistic pos

sibility that egregious abuses of police authority may

result in substantial damage awards is necessary if such

unconstitutional conduct is to be deterred.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (MALDEF) is a privately-funded civil rights or

ganization founded in 1968. MALDEF is dedicated to

ensuring through law that the civil rights of Mexican

Americans are protected. Over the past nine years

MALDEF has represented or assisted Mexican Americans

in a variety of cases brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983

arising from violent abuse of police authority. MALDEF

therefore has a significant interest in the continuing

vitality of § 1983 as a legal remedy for the deprivation

of federal rights.

3

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP) is a non-profit membership

association representing the interests of approximately

500,000 members in 1800 branches throughout the United

States. Since 1909, the NAACP has sought through the

courts to establish and protect the civil rights of mi

nority citizens. 42 U.S.C. § 1983 has been central to the

MAACP’s litigation efforts, especially those seeking re

dress for personal injury and death unnecessarily in

flicted upon minority citizens by police officials under

color of state law.

In the experience of amici, the unwarranted misuse

of police power, including the unjustifiable use of deadly

force, disproportionately strikes down minority Ameri

cans. In the present § 1983 case, brought in Colorado

state court, a Denver police officer is charged with in

tentionally killing a fifteen-year-old black boy without

reason. Astonishingly, the courts below have effectively

determined that, under recovery rules which they deemed

mandated by federal law, this unconstitutional death has

a compensable value of $1,500. We are confident from

our experiences and observations that almost any de

gree of physical injury short of death would have a

higher value anywhere in the country, including Colo

rado. If the rule announced below is affirmed by this

Court, therefore, the result will be that the Nation’s

law enforcement officers will be given an incentive to kill

during the course of employing excessive force. Such a

rule is intolerable, in our view; it seriously undermines

our efforts to secure complete justice for our clients;

and it repudiates the basic purposes of § 1983.

Amici thus have an interest in this dispute greater

than that of the actual parties. In the remainder of

this brief we address issues which may not be discussed

by the parties, but which we believe are essential to the

just disposition of this case. That disposition, in our

opinion, requires reversal of the judgment below and a

remand for the trial of petitioner’s § 1983 claims.

4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On February 5, 1972, respondent Hildebrant, a white

Denver, Colorado police officer, intentionally shot and

killed petitioner’s 15-year-old black son. Petitioner in

stituted this action against respondent Hildebrant and

respondent City and County of Denver on October 15,

1973, in the State District Court for the City and County

of Denver, seeking compensatory and punitive damages

for the alleged unlawful killing of her son, and raising

claims under both state and federal law.1 In their an

swer respondents admitted the shooting, and admitted

that respondent Hildebrant was acting within the scope

of his office as a Denver law enforcement officer. Re

spondents denied, however, that petitioner’s son was

killed in violation of either state or federal law; re

spondents asserted as affirmative defenses that the kill

ing was privileged because decedent was a fleeing felony

suspect who could not have been apprehended without

the use of deadly force, that respondent Hildebrant em

ployed deadly force in self-defense, and that he used only

that amount of force reasonably necessary under the

circumstances.

1 As amended, petitioner’s complaint in the state trial court, as

consistently construed by both the trial court and the Colorado

Supreme Court, stated three claims for relief: (1) for battery

under state law; (2) for negligence under state law; (3) for viola

tion of federal constitutional rights. See Jones v. Hildebrant, 550

P.2d 339, 341 (Colo. 1976). The state courts treated the first two

claims for relief as being authorized by the state wrongful-death

statute, Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-21-202 (1973) ; the third claim

was treated as one authorized by 42 U.S.C. § 1983. However, the

complaint did not expressly refer to either the state wrongful-death

statute or § 1983. The federal claim also makes no reference to

specific provisions of the federal Constitution, but, fairly read, it

alleges violations of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment. The lower courts in this case have

uniformly construed this as a Fourteenth Amendment cause of

action authorized by <§ 1983.

5

The case proceeded to trial on all of petitioner’s claims.

At the close of proof and before the case was submitted

to the jury, however, respondents moved to dismiss pe-

tioner’s federal (42 U.S.C. § 1983) claim. The trial judge

granted the motion on the ground that the § 1983 claim

merged with the state law claims, and that no relief

different from that recoverable under the state-law claims

was available under § 1983. The case thus went to the

jury on petitioner’s state-law claims only. On the issue

of damages, the jury was instructed that petitioner was

limited to recovering the net pecuniary loss she sustained

as a result of her son’s death, with a maximum allowable

recovery of $45,000 (because petitioner was not a de

pendent of decedent) ; future earnings, loss of society,

exemplary damages and the like were held to be unre

coverable under state wrongful-death law. The jury

resolved the issues of liability under state law in pe

titioner’s favor but returned a verdict of only $1,500

against respondents. The trial judge denied a motion

for a new trial on the issue of damages.

On petitioner’s appeal, the Colorado Supreme Court

addressed a number of issues, Jones v. Hildebrant, 550

P.2d 339 (Colo. 1976), only a few of which are fairly

comprised within the grant of certiorari. Su prem e

Court Rules 23(1) (c), 40(d) (1). With respect to pe

titioner’s appeal on the limitations placed on damages

recoverable under the state-law claims, the Colorado

Supreme Court (1) declined to discard the “net pecuni

ary loss” rule first established in an 1894 decision of

that court, and (2) upheld the $1,500 verdict as being

adequate under that rule, 550 P.2d at 341-42. Neither

of these issues is presented for review by this Court,

nor could they be.2

2 The court implicitly rejected petitioner’s claim that the “net

pecuniary loss” limitation on recovery under the state’s wrongful-

death statute was inconsistent with the Fourteenth Amendment.

6

As to petitioner’s federal claim that her § 1983 cause

of action was distinct from the state-created wrongful

death action—and that it should not therefore have been

“merged” with the state action nor dismissed by the trial

judge 3—the Colorado Supreme Court considered and de

cided four somewhat overlapping issues. At the outset,

the court considered a contention by petitioner (viewed

by the court as “confusingly stated” ) to the effect that

petitioner’s “civil right to her son’s life,” as recognized

by the state wrongful-death statute, “was denied her

without due process of law through his wrongful kill

ing.” 550 P.2d at 342. On the basis of this Court’s de

cision in Paul v. Davis, 424 U.S. 693 (1976), the

court rejected this contention, holding that “where, as

here, the state allows a plaintiff to bring her [wrongful-

death] suit, she is not deprived of any of her civil rights

without due process of law.” 550 P.2d at 343. While

we confess difficulty in understanding this issue,4 it is a

550 P.2d at 342. This claim likewise is not pressed before this

Court by the petitioner.

3 Since petitioner’s § 1983 claim was dismissed prior to sub

mission of the case to the jury, there has been no determination

that plaintiff’s son was killed in contravention of the federal Con

stitution, as distinct from state law. The Colorado Supreme Court

appears to have assumed that the facts as found by the jury also

constituted a federal constitutional violation. In any event, this

Court must, in the present posture of this case, make a similar

assumption, as in all cases where a federal claim is dismissed prior

to decision on the merits. It is sufficient to observe here that the

Fourteenth Amendment expressly protects human life from wanton

deprivation by the state. See, e.g., Screws v. United States, 325 U.S.

91 (1945). If petitioner prevails here, therefore, she will be entitled

to a remand for trial of her § 1983 claims.

4 Apparently petitioner’s contention was: (1) that Colorado’s

wrongful-death statute created substantive property rights in a

class of individuals bearing certain specified relationships to de

cedents; (2) that these rights were protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment; and (3) that in a § 1983 wrongful-death action, the

state “net pecuniary loss” rule could not be applied without in

fringing those substantive property rights in violation of the Four-

7

constitutional claim which need not be determined in

order to reach the question presented for review by this

Court, and it is not fairly comprehended within the

grant of certiorari.

The next three issues decided by the Colorado Supreme

Court are, however, properly embodied within the ques

tion presented for review here, for they involve inter

pretations of § 1983 which led the court below to con

clude that § 1983 was identical in purpose and effect

to the Colorado wrongful-death statute. First, the court

attempted to determine the federal law of damages

applicable to § 1983 wrongful-death actions brought in

Colorado federal courts. Reviewing a number of lower

federal court decisions which had utilized 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988 to “incorporate” relevant state survival and

wrongful-death statutes into § 1983 actions brought in

federal court, the Colorado Supreme Court concluded

that Colorado’s wrongful death remedy would be en

grafted into a § 1983 action if brought in a federal

court. However, because the instant suit was

brought in state court and joined with a suit under

the state wrongful death statute, the trial court

properly ruled that the two actions were merged

so that the § 1983 claim should be dismissed.

teenth Amendment. Petitioner may have relied, incorrectly, upon

the previous decision in Fish v. Liley, 120 Colo. 156, 208 P.2d 930

(1949) to support her assertion that the wrongful-death statute

created a “property right.” In the instant case, however, the

Colorado Supreme Court rejected that assertion and characterized

the wrongful-death statute as “remedial,” 550 P,2d at 344, creating

only a “right to sue” at law for a tort which, under Paul v. Davis,

423 U.S, 693 (1976), was distinguishable from a “property

right.” In any event, since petitioner has not pressed her attack

upon the “net pecuniary loss” limitation of the state claim (see note

2, supra.), this issue also does not seem to be presented for this

Court’s review.

8

Furthermore, because the allowable damages are

such an integral part of the right to bring a wrong

ful death remedy, we believe the state’s law on

damages should also apply.

550 P.2d at 344 (footnotes omitted). Second, the court

rejected petitioner’s argument that there is a § 1983

wrongful-death remedy independent of state law. The

court based its conclusion “on the perceived Congressional

intent not to pre-empt the states’ carefully wrought

wrongful death remedies, the adequacy in a death case

of the state remedies to vindicate a civil rights violation,

and the overwhelming acceptance of such state remedies

in the federal courts.” Id. at 345 (footnote omitted).

Third, the court held that “one may not sue for the de

privation of another’s rights under § 1983 . . .” and that

petitioner “therefore cannot sue in her own right for

the deprivation of her son’s rights apart from her remedy

under the wrongful death cause of action.” Id.

Two Justices dissented on the ground that “Colorado’s

judicial limitation of net pecuniary loss as a measure of

damages for wrongful death [does not] applfy] to ac

tions founded upon 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1970).” Id, at

345-46. It is this question framed by the dissenting Jus

tices, and the issues fairly comprised therein, that are

before the Court pursuant to its grant of certiorari.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

This case presents important questions of federal law

concerning the fashioning of appropriate relief in ac

tions brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 alleging that

unconstitutional state action caused human death. The

precise question presented for review—“what is the meas

ure of damages” in such an action—arises (as the phras

ing in the Petition for Certiorari indicates) in the con

9

text of a state court disposition of a § 1983 claim which

the Colorado courts are willing and able to entertain.

However, the court below clearly understood that it was

considering and deciding questions of federal law in de

termining that the measure of damages in a § 1983

wrongful-death action was the same as that in the state

wrongful-death claim. There are no considerations of

comity or federal-state tensions which affect the disposi

tion of the federal questions presented in this case, -which

is in the same posture as if it had been brought in the

United States District Court for the District of Colorado

and federal judges below selected the Colorado “net pecu

niary loss” rule as the measure of damages in a § 1983

action.

II

The court below was correct in deciding another is

sue implicit in the question presented for review here:

whether § 1983 authorizes a cause of action to be prose

cuted when constitutional wrong results in death. Al

though the parties may not address this issue, this

Court’s disposition of the major question may necessarily

decide it, and amici therefore discuss it. As we show,

the lower federal courts and the Colorado courts in the

instant case have uniformly recognized a § 1983 action

for wrongful death resulting from unconstitutional ac

tion, though on the basis of differing rationales. The

result in these cases is clearly correct, and this Court

should have no hesitation in affirming the determination

of this issue by the Colorado Supreme Court in order to

reach and decide the important remedial question which

is the major subject of controversy in this case.

III

The court below wTas of the view that while petitioner

was entitled to utilize the process of Colorado’s wrongful-

death statute in order to maintain a § 1983 action against

10

respondents, she was also required to accept the severe

limitations on damages embodied in that statute, as

judicially construed. The plain meaning of this ruling,

in the context of this case, is that even if petitioner’s

15-year-old son was killed in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, such constitutional injury has a compensable

value of $1,500. This ruling is untenable. If petitioner

prevails on the merits of her § 1983 claim she is en

titled to have the Colorado courts award a federal meas

ure of relief commensurate with (1) prevailing notions

of complete justice, and (2) the dual remedial purposes

of § 1983’s private-enforcement scheme: just compensa

tion and deterrence of unconstitutional conduct on the

part of state officials. As a general matter of federal law,

principles of damages applicable to § 1983 cases must

encompass all elements of the particular constitutional

injury, and must also reflect the statute’s exemplary

goals. Colorado’s “net pecuniary loss” rule is inconsistent

with these applicable principles. Uniform federal rules

of recovery in § 1983 actions are essential; there is no

basis for the requirement imposed below that the dam

ages rules embodied in the state’s wrongful-death statute

must be applied in federal § 1983 actions.

IV

If the Court should hold that reference to state wrong

ful-death and survival statutes in § 1983 actions must

carry with it the state-created limitations on damages,

then this Court should reject the use of state law in its

entirety and create a federal common law of wrongful

death applicable to actions under the Act, as the Court

has done in other important areas of federal juris

prudence.

11

ARGUMENT

I. The Colorado Courts Properly Entertained This § 1983

Suit, Though They Were Required To Apply Federal

Law In Determining Its Outcome.

This ease presents an opportunity for the Court to de

cide a heretofore unresolved question: whether state

courts may entertain actions brought under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983. See Aldinger v. Howard, 96 S. Ct. 2413, 2430 n.

17 (1976) (dissenting opinion). Amici think the answer

is that they may. The heart of this case is 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 which, together with its jurisdictional counter

part, 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3), derives from § 1 of the Ku

Klux Act of 1871.5 The overriding purpose of that en- 6

6 As originally passed, § 1 of the 1871 Act, 17 Stat. 13, read as

follows:

Be it enacted, by the Senate and House of Representatives of

the United States of America in Congress assembled, That

any person who, under color of any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage of any State, shall subject, or

cause to be subjected, any person within the jurisdiction of

the United States to the deprivation of any rights, privileges,

or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States, shall, any such law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

custom, or usage of the State to the contrary notwithstanding,

be liable to the party injured in any action at law, suit in

equity, or other proper proceeding for redress; such proceed

ing to be prosecuted in the several district or circuit courts

of the United States, with and subject to the same rights

of appeal, review upon error, and other remedies provided in

like cases in such courts, under the provisions of the act of the

ninth of April, eighteen hundred and sixty-six, entitled “An act

to protect all persons in the United States in their civil rights,

and to furnish the means of their vindication” ; and the other

remedial laws of the United States which are in their nature

applicable in such cases.

The cause-of-action and jurisdictional parts of § 1 of the Ku

Klux Act are now separately codified, the former being 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory, sub-

12

actment was to provide a federal forum for the enforce

ment of the then-recent federal rights conferred by the

Fourteenth Amendment (1868). Monroe v. Pape, 365

U.S. 167 (1961). The legislative history of the Ku Klux

Act reveals that Congress, rather than seeking to utilize

the state courts as the primary enforcers of the Four

teenth Amendment, was displeased with those courts

because of their past failures.6 Some state courts have

refused to entertain § 1983 actions precisely because of

that perceived congressional hostility.* 6 7 But the constitu

tional correctness of those decisions is not at issue here,8

jeets, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United

States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the

deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured

by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party

injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper

proceeding for redress.

The jurisdictional provision is now 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) :

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any

civil action authorized by law to be commenced by any person:

* * * *

(3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any State

law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage, of any

right, privilege or immunity secured by the Constitution of the

United States or by. any Act of Congress providing for equal

rights of citizens or of all persons within the jurisdiction of

the United States;

The evolution process is informatively traced in Blue v. Craig,

505 F.2d 830 (4th Cir. 1974).

6 See generally Monroe V. Pape, supra, 365 U.S. at 174-80. The

mood of Congress and its attitude toward state courts was accurately

summed up by Representative Yoorhees, an opponent of the Act, in

cluding its provisions conferring federal-court jurisdiction: “This

is to be done upon the assumption that the courts of the southern

States fail and refuse to do their duty in the punishment of

offenders against the law.” CONG. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess.,

App. 179.

7 See, e.g., Chamberlain v. Brown, 442 S.W.2d 248 (Tenn. 1969).

8 Section 1983, of course, is in principal function a federal-

court jurisdictional vehicle for civil actions arising under the

13

for the Colorado courts have not expressed unfriendli

ness toward petitioner’s § 1983 claims. Indeed, the Colo

rado Supreme Court’s opinion in this case appears un

qualifiedly receptive to petitioner’s § 1983 arguments, and

the court made a creditable attempt, albeit an erroneous

one in our view, to interpret and apply federal law.9

With this background, the only state court/federal

law question that could remain is whether, contrary to

the Colorado Supreme Court’s assumption, state courts

Fourteenth Amendment (or, to be more precise, under “the Consti

tution and laws’’). Section 1983 aside, it is difficult to perceive,

given the Supremacy Clause (indeed, given the plain language

of the Fourteenth Amendment itself), how a state court of general

jurisdiction could, as in cases such as the one cited in note 7,

supra, refuse to receive an action to vindicate Fourteenth Amend

ment rights. Any contention that such state power exists would

seem to have “been resolved by war” to the contrary. Testa V.

Katt, supra, 330 U.S. 386, 390 (1947). But, as we say, that issue

is not implicated here.

9 This case does not involve any of the knotty conflicts between

state courts and federal law which have arisen from time to time

over the years. Accordingly, we take a moment to identify what is

not at issue here. In general, this case presents none of the more

difficult problems flowing from Mr. Justice Bradley’s benchmark

post-Civil War decision in Claflin V. Houseman, 93 U.S. 130 (1876),

holding that federally-created rights could be vindicated in state

courts with competent jurisdiction. More specifically, this case is

not one in which the state court, by virtue of some uniformly-

applied procedural rule pertaining to access to it, has refused to

entertain a federal cause of action. Cf. Missouri ex rel. Southern

Ry. V. Mayfield, 340 U.S. 1 (1950) (F rankfurter, J.) ; Douglas v.

New York, N.H. & H.R.R., 279 U.S. 377 (1929) (Holmes, J.).

Nor is this case one in which Congress has created a cause of action

and conferred concurrent enforcement jurisdiction on the federal

and state courts, but state-court jurisdiction is refused on grounds

which discriminate against the cause of action solely because of

its federal source. Cf. Testa v. Katt, 330 U.S. 386 (1947) (Black,

J . ) ; McKnett V. St. Louis & S.F. Ry., 292 U.S. 230 (1934) (Bran-

deis, J.) ; Second Employers’ Liability Cases (Mondou v. New

York, N.H. & H.R.R.), 223 U.S. 1 (1912). And, manifestly, this

case is not one in which Congress has attempted to force upon

the state courts the duty to enforce a federal law. Cf. Brown v.

Gerdes, 321 U.S. 178, 191 (1944) (Frankfurter, J., concurring).

14

lack authority to adjudicate § 1983 cases. In other words,

are § 1983-Fourteenth Amendment causes of action mat

ters, either expressly or by necessary implication, within

the exclusive province of federal judicial power? Last

Term three members of this Court expressed the view

“that § 1983 claims are not claims exclusively cognizable

in federal court but may also be entertained by state

courts.” Aldinger v. Howard, supra, 96 S. Ct. at 2430 n.

17 (1976) (Brennan, J., joined by Marshall and Black-

mun, JJ., dissenting). That view, in our judgment, is un

assailable in the light of established precedent. Without

a case in this Court squarely on point, it would be dif

ficult to find a more closely analogous decision than that

in Charles Dowd Box Co. v. Courtney, 368 U.S. 502

(1962).

Charles Dowd involved a labor-contract suit initiated

in state court. By § 301(a) of the Labor Management

Relations Act of 1947, however, Congress had provided

that such suits “may be brought in any district court of

the United States. . . .” See id. at 502. Section 301 was

produced by circumstances not unlike those that gave

birth to § 1983—namely the inadequacy or unavailability

of state-court remedies:

A principal motive behind the creation of federal

jurisdiction in this field was the belief that the

courts of many States could provide only imperfect

relief because of rules of local law which made suits

against labor organizations difficult or impossible, by

reason of their status as unincorporated associa

tions.

Id. at 510. Moreover, in Textile Workers Union v.

Lincoln Mills, 363 U.S. 448 (1957), this Court had

held that § 301 cases brought in federal courts were to

be governed by federal rather than state law, a proposi

tion that inescapably obtains in § 1983-Fourteenth

Amendment cases. The contention was accordingly made

in Charles Dowd that even though § 301 did not express

15

ly provide for exclusive federal-court jurisdiction, fed

eral exclusivity must necessarily be implied from the

Lincoln Mills-% 301 scheme as it had been implied in

other cases.10 The Court unanimously rejected the argu

ment in an opinion authored by Mr. Justice Stewart.

Upon examination of the legislative history, the Court

found that “the purpose of conferring jurisdiction upon

the federal district courts was not to displace, but to

supplement, the thoroughly considered jurisdiction of the

courts of the various States over contracts made by la

bor organizations.” Id. at 511. Congressional purpose

was to submit § 301 problems “ ‘to the usual processes

of the law.’ ” Id. at 513. This legislative history coupled

with Justice Bradley’s Claflin v. Houseman 11 test—that

the state courts have concurrent jurisdiction “where it is

not excluded by express provision, or by incompatibility

in its exercise arising from the nature of the particular

case” (93 U.S. at 136)—led the Court in Charles Doivd

to the inevitable conclusion that the state courts enjoyed

jurisdiction concurrent with that of the federal courts in

§ 301 cases.

A similar analysis leads to the same conclusion with

respect to the authority of the state courts to hear § 1983

cases. We have found nothing in the legislative debates

manifesting a congressional desire to deprive the state

courts of jurisdiction in Fourteenth Amendment cases.

While it is true that Congress was displeased with the

performance of state courts in this regard (see note 6,

supra), it is also clear that Congress understood that

Fourteenth Amendment rights could be vindicated in the

state courts, as rights secured by the Contracts Clause,

for example, had been historically, with ultimate federal

10 See, e.g., San Diego Building Trades Council v. Garmon, 359

U.S. 236 (1959); Gamer v. Teamsters, C. & H. Local Union, 346

U.S. 485 (1953) ; Brown V. Gerdes, 321 U.S. 178 (1944).

11 See note 9, supra.

16

protection provided in the form of review by this Court

under § 25 of the Judiciary Act of 1789.12 Yet, there is

no indication whatsoever that Congress intended § 1 of

the Ku Klux Act to deprive the state courts of power

to decide Fourteenth Amendment cases. It simply chose

the federal judiciary, which it viewed as being less sus

ceptible to the pressures of popular passions than the

state court systems, as the primary forum for the ad

judication of individual federal rights13—primary but,

at the litigant’s option, not exclusive.14

The language of § 1983’s jurisdictional grant, 28

U.S.C. § 1343(3), also fails to support an argument for

exclusivity. There is no difference between the language

of § 301 considered in Charles Dowd and that of § 1343

sufficient to require a different conclusion. The principal

difference is that § 301 spoke in terms of “may” (labor-

contract cases “may be brought in any district court of

the United States” ), while § 1343’s preamble speaks in

terms of “shall” (“ [t]he district courts shall have orig

inal jurisdiction” of the enumerated civil actions, includ

ing those authorized by § 1983).15 But the “shall” man

date simply obliges federal courts to receive § 1983

cases; it does not preclude the state courts from also

12 See Monroe v. Pape, supra, 365 U.S. at 194-98 (Harlan, J.,

concurring).

13 See, e.ff., Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974) ; District of

Columbia V. Carter, 409 U.S. 418 (1973); Lynch V. Household

Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538 (1972); Mitchum v. Foster, 408 U.S.

225 (1972); Zwiclder v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967).

14 When the Congress of these times desired to confer exclusive

federal jurisdiction, it knew how to do it expressly. See note 36,

infra, for example.

15 The original jurisdictional language, as it appeared in § 1

of the Ku Klux Act (see note 5, supra) authorized an appropriate

“action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for re

dress; such proceeding to be prosecuted in the several district or

circuit courts of the United States. . . .”

17

entertaining them. That is the teaching, without excep

tion, of the Claflin v. Houseman line of cases.

State courts are thus free to contribute to § 1983-

Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence. Of course, in

the contribution process it is federal law rather than

state law which they must expound. The Court made

that clear enough when later in the same Term that

produced Charles Dowd it rejected a state-court deter

mination that state courts could apply state law in § 301

cases. Local 17J V. Lucas Flour Co., 369 U.S. 95 (1962).

That conflict, however, is not presented by the decision

below in this case, as the Colorado Supreme Court made

a straightforward effort to determine and apply federal

law. The case is thus in no different posture for deci

sion-making purposes than it would be had it arrived

here from a lower federal court. The Court’s task in this

case, as in the numerous previous state-court cases re

quiring the application of federal law by this Court,16

.as well as the many federal cases in which the Court

has been required to develop federal law,17 is to decide

what federal law is or ought to be and apply it to the

case. That such cases may occasionally arise in the state

courts is an asset rather than a liability; it is good con

stitutional law and, consequently, good federalism. As

Mr. Justice Stewart put it in Charles Dowd (368 U.S.

at 514) (footnote omitted) :

It is implicit in the choice Congress made that “di

versities and conflicts” may occur, no less among the

courts of the eleven federal circuits, than among the

courts of the several States, as there evolves in this

field of labor management relations that body of

16 See, e.g., Sullivan V. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969);

Local 17U v. Lucas Flour Co., supra; Farmers Educ. Cooperative

Union v. WDAY, 360 U.S. 525 (1959) ; McAllister v. Magnolia

Petroleum Co., 357 U.S. 221 (1958); Garrett v. Mo or e-McCormack

Co., 317 U.S. 239 (1942); and other cases discussed in Argument

IV, infra.

17 See, e.g., cases and authorities discussed in Argument IV, infra.

18

federal common law of which Lincoln Mills spoke.

But this not necessarily unhealthy prospect is no

more than the usual consequence of the historic ac

ceptance of concurrent state and federal jurisdic

tion over cases arising under federal law. To re

solve and accommodate such diversities and conflicts

is one of the traditional functions of this Court.

II. Civil Actions May Be Maintained Under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 By Persons, Such As Petitioner Here, Who Seek

To Redress Unconstitutional State Action Resulting

In Human Death.

Although this Court has never addressed the question,18

the lower federal courts are in unanimous agreement

that death does not abate a pending § 1983 cause of ac

tion nor prevent the bringing of such an action for un

constitutional conduct which causes death.19 These courts

18 In Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693, 702 n.14 (1973),

the Court noted, without approval or disapproval, that the lower

federal courts had applied “state survivorship statutes” in § 1983

cases. In Scheuer v. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974), the Court con

sidered other problems in a § 1983 wrongful-death case without

alluding to any of the questions present here.

19 At common law, death gave rise to no cause of action and

terminated all those for personal torts. As described by this Court

in Moragne v. States Marine Lines, Inc., 393 U.S. 375 (1970), the

reason can be traced to the felony-merger doctrine, under which

the penalty for committing a felony included the forfeiture to the

Crown of all property owned by the wrongdoer. The harshness of

the doctrine has been substantially ameliorated by the passage of

statutes both in England and in this country. While these statutes

vary widely in their terms and scope, most legislative schemes

create two separate and distinct causes of action. The first, termed

“survival” statutes, generally permits recovery by the decedent’s

executor of damages which accrued from the injury prior to the

death of the decedent. See Sea-Land Services v. Gaudet, 414 U.S.

573, 575 n.2 (1974). The second, generally described as “wrong

ful-death” statutes, permits the heirs to bring suit subsequent

to the decedent’s death for the loss to them. See generally 2 F.

Harper & F. J ames, Law of Torts §§ 24.1-24.3 (1956), C. McCor

mick Handbook on Damages § 12 (1935). Colorado has enacted both

19

have uniformly considered themselves obligated by estab

lished principles to fashion a federal law of wrongful

death and survival in § 1983 cases.20 To be sure, these

courts also frequently utilize 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (which

we discuss below) as a vehicle by which to utilize state

wrongful-death and survival provisions. But when rele

vant state law is absent or found wanting, the courts

proceed to shape a suitable federal rule.21 Amici believe

types of statutes; the wrongful-death action is created by Colo.

Rev. Stat. § 13-21-202 and the survival statute is § 13-20-101. An

action under the survival statute does not preclude an action for

wrongful death. Id., §13-20-101(1). The former must be brought

by the executor of the decedent’s estate, but the latter may be

brought by certain designed survivors. Some states permit sur

vival actions to be brought by the executor of the estate for dam

ages even where death is instantaneous. Colorado apparently is not

one of these. See Publix Cab Company v. Colorado National Bank

of Denver, 139 Colo. 205, 338 P.2d 702, 706 (1959). The difference

between wrongful-death and survival statutes is discussed in W.

Prosser, Law of Torts, §§ 126, 127 (4th ed. 1971); Malone, The

Genesis of Wrongful Death, 17 Stan. L. Rev. 1043, 1044 (1965).

Since petitioner’s decedent died instantly, this suit was com

menced under the Wrongful Death Statute and not the survival

statute. Petitioner sued individually as the mother of the decedent

and not as the administratrix of her son’s estate. Thus, as the

complaint made clear, the suit, insofar as it states a claim under

42 U.S.C. § 1983, asserts a cause of action on the basis of the alleged

unlawful killing of petitioner’s son.

20 See, e.g., Spence V. Staras, 507 F.2d 554, 557 (7th Cir. 1974);

Hall V. Wooten, 506 F.2d 564 (6th Cir. 1974); Mattis V. Schnarr,

502 F.2d 588, 593 (8th Cir. 1974) ; Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F.2d

401 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 921 (1961); Pritchard v.

Smith, 289 F.2d 153 (8th Cir. 1961) ; Smith v. Wickline, 396 F.

Supp. 555 (W.D. Okla. 1975); James v. Murphy, 392 F. Supp. 641

(M.D. Ala. 1975); Evain v. Conlisk, 364 F. Supp. 1188 (N.D. 111.

1973), aff’d, 498 F.2d 1403 (7th Cir. 1974) ; Perkins v. Salafia, 338

F. Supp. 1325 (D. Conn. 1972); Salazar V. Dowd, 256 F. Supp. 220

(D. Colo. 1966) ; Cinnamon V. Abner A. Wolf, Inc., 215 F. Supp.

833 (E.D. Mich. 1963) ; Davis v. Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572 (N.D.

111. 1955).

21 See, e.g., Shaw V. Garrison, 545 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1977) (Wis

dom, J .) .

20

that this result is wholly sustainable as a rightful part

of the business of judging in a federal system, quite

apart from § 1988 or state law.

A. Section 1983 Creates A Constitutional Cause of

Action Wholly Apart From State Tort Law.

Section 1983-Fourteenth Amendment actions at law

are inherently distinct from state tort actions and, for

that matter, any other type of legal action that does not

concern personal rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

We are confirmed in this view by all of this Court’s

§ 1983 decisions from Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 194

(1961) through Paul v. Davis, 424 U.S. 693 (1976).

Those decisions instruct that the facts which make out

a § 1983 cause of action may coincidentally consti

tute a state-law tort or some other violation of state

law, but that conduct unlawful under state law does not

ipso facto establish the components of a § 1983 case.

The failure to perceive this critical distinction is at the

bottom of the Colorado Supreme Court’s erroneous con

clusion that petitioner’s § 1983 claim merged with her

state-law claims.

The inherently unique nature of a § 1983 case derives

not solely from the “under color of law” element, see

Adickes v. S. H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970),

although this is the ingredient that in the first instance

distinguishes § 1983 from common-law tort doctrine. The

more important difference, in cases such as this, is the

fact that § 1983 is a vehicle for the vindication of in

dividual constitutional rights guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment.23 As Mr. Justice Harlan explained

in Monroe v. Pape, supra, 365 U.S. at 196 (concurring

opinion), “a deprivation of a constitutional right is sig

nificantly different from and more serious than a viola- 22

22 This case does not involve the “and laws” portion of § 1983,

21

tion of a state right and therefore deserves a different

remedy even though the same act may constitute both

a state tort and the deprivation of a constitutional right.”

It is because constitutional rights are involved that the

interests protected by § 1983 transcend the values with

which the general common law is concerned. The dis

trict court’s decision in Shaw v. Garrison, 391 F.Supp.

1353 (E.D. La. 1975), aff’d, 545 F.2d 980 (5th Cir.

1977), illustrates the distinction. There Judge Heebe

refused to allow a pending § 1988 action to abate because

of the death of the plaintiff, although under state law

governing actions for libel, slander or malicious prosecu

tion the death of the plaintiff would have abated the

action. The inherent difference between § 1983-Four-

teenth Amendment actions and state-tort actions was

critical to Judge Heebe’s decision (391 F.Supp. at 1364

n.17) :

The fact of the matter is that this is not a state

action for libel, slander or malicious prosecution, but

a federal action for violation of plaintiff’s civil

rights. We have already determined that the pur

poses underlying this statute require that the action

not abate, if there is some proper mechanism for

survival. The fact that some states may have a dif

ferent policy for a cause of action based on the

same facts yet differently characterized should not

be binding on a federal court construing civil rights

actions.

It is not only § 1983’s concern with constitutional

rights, however, that makes it intrinsically unique. For

there is the added factor of the statute’s great remedial

design. It is thus because of the overriding constitutional

remedial purpose of § 1983’s private enforcement scheme

—designed both to compensate for and to deter constitu

tional injury—that causes of action thereunder require

22

a special place in the litigation hierarchy.28 It is, in

23 As stated in Niles, Civil Actions for Damages Under the

Federal Civil Rights Statutes, 45 Tex.L.Rev. 1015, 1026 (1967) :

[T]he basic policy behind tort law is compensation for

physical harm to an individual’s person or property by shifting

losses from the one injured to. the one perpetrating the injury,

while the underlying policy of the civil rights statutes is quite

different. The legislative intent behind these statutes is not

entirely certain since other provisions of the Act of 1871 re

ceived far more attention in congressional debate than did those

that eventually became sections 1983, 1985, and 1986. One pur

pose of the Act apparently was to provide a federal forum

for rights that the disorganized Southern state governments

were not protecting adequately. It seems clear, however, from

the statements of a few legislators, the title of the Act itself,

and the circumstances surrounding its passage that the Act’s

primary purpose was to enforce the fourteenth amendment by

providing a positive, punitive civil remedy for acts of racial

discrimination. Thus an award of damages would depend not

on the common-law test of whether a plaintiff had suffered

a measurable physical or economic injury, but on whether the

defendant’s conduct came within the scope of actions that the

statutes were intended to penalize. While traditional tort law

damages rules may be appropriate to accomplish some of the

civil rights statutes’ purposes, the tort-law rules do no [sic]

allow full realization of those purposes because of their empha

sis upon loss-shifting rather than upon punishment and de

terrence. [footnotes omitted]

Since § 1983 and common-law tort concepts protect different inter

ests, and concern different legal relationships, a plaintiff injured in

both respects may maintain separate suits in both state and federal

courts, even though both wrongs arise out of the same occurrence.

Page, State Law and the Damages Remedy Under the Civil Rights

Act: Some Problems in Federalism, 43 Denver L.J. 480, 481, 483

(1966) . Or, both the state and federal claims may be combined in

a single suit in state court, as here; or, with certain limitations,

both claims may be brought in one suit in federal court, with the

state claim cognizable under the doctrine of pendent jurisdiction.

Aldinger v. Howard, 96 S. Ct. 2413 (1976). This does not mean,

of course, that double recovery will be permitted for the same ele

ments of injury. See Stringer v. Dilger, 313 F.2d 536, 541-42 (10th

Cir. 1963) ; Rue V. Snyder, 249 F. Supp. 740, 743 (E.D. Tenn.

1966); see generally Niles, Civil Actions for Damages Under the

Federal Civil Rights Statutes, 45 Tex. L. Rev. 1015, 1029-30

(1967) . Cf. Sea-Land Services v. Gaudet, 414 U.S. 573 (1974).

Thus, in the instant case, the jury (had petitioner’s § 1983 claims

23

other words, the superior quality of these “federally pro

tected rights” that calls into play the intense judicial

scrutiny not normally associated with the legal relation

ships governed by the general common law as developed

by the states. See Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684

(1946). That the statute is preoccupied with remedy is

made plain from the congressional debates on both the

Fourteenth Amendment and its principal enforcement

mechanism, the Ku Klux Act, from which § 1983 derives.

It was repeatedly asserted that equal rights and the

privileges and immunities of citizens were being denied

by the states, “and that without remedy.” Cong. Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2542 (Remarks of Rep. Bingham

with reference to § 1 of the proposed Fourteenth Amend

ment). And the opponents contended that the majority

of Congress were willing “to overturn the whole Con

stitution to get at a remedy for these people.” Id. at

499 (Sen. Cowan). The Ku Klux Act which Congress

debated in the Spring of 1871 did not “overturn the

whole Constitution,” but there can be no doubt that its

central thesis was to provide a supervening federal

remedy for denial of the fundamental rights which the

Fourteenth Amendment was designed to secure as against

the states. See, e.g., Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess.,

App. 85 (Rep. Bingham, the author of § 1 of the Four

teenth Amendment).

With respect to this central remedial theme, and im

portantly for this case, it is clear that Congress did not

intend to place death-dealing constitutional injury be

yond the reach of the statute. Quite simply, “it defies

history to conclude that Congress purposely meant to as

sure to the living freedom from such unconstitutional de

privations, but that, with like precision, it meant to

been submitted to the jury) could have been instructed that if the

defendants were found liable under both the state and federal

claims, the verdict under § 1983 could not reflect the “net pecuniary

loss” damages recoverable under the state causes of action.

24

withdraw the protection of civil rights statutes against

the peril of death.” Brazier v. Cherry, supra, 293 F.2d

at 404.24 25 Indeed, President Grant’s message to Congress,

which inspired the Ku Klux Act, was predicated upon

“ [a] condition of affairs [that] now exists in some States

of the Union rendering life and property insecure . . . .”

Cong . Globe, 42d Cong., 1st Sess. 244 (emphasis added);

see Monroe v. Pape, supra, 365 U.S. at 172. And hardly

a page of the debates passes without at least one ref

erence to murder, lynchings and other modes of killing.

It was the purpose of the Ku Klux Act to provide federal

protection for “life, person and property,” Cong . Globe,

42d Cong., 1st Sess. 321, 322 (Rep. Stoughton) ; it was

an effort to attain “that twilight civilization in which

every man’s house is defended against murder and ar

son. . . .” Id. at 370 (Rep. Monroe). The debates are

replete with such references. See also, e.g., id. at 374

(Rep. Lowe), 428 (Rep. Beatty), quoted in Monroe v.

Pape, supra, 365 U.S. at 175.

On the other hand, there is nothing in the debates to

support a contention that § 1 of the Act (now § 1983)

was intended to limit the authorized civil action by the

“person injured” to those circumstances where death does

not occur.23 The only contrary argument we are aware

24 The Brazier court went on to point out that “ [t]he policy of

the law and the legislative aim was certainly to protect the security

of life and limb as well as property against these actions. Violent

injury that would kill was not less prohibited than violence which

could cripple.” 293 F.2d at 404. As the court observed in Davis v.

Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572, 574 (N.D. 111. 1955), a contrary holding

“would encourage officers not to stop after they had injured but

to be certain to kill.” See also W. P r o s s e r , L a w o f T o r t s § 127

at p. 902 (4th ed. 1971).

25 Some courts, in fact, have held that the decedent’s executor is

a “person injured” within the contemplation of § 1983. See, e.g.,

Davis V. Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572 (N.D. 111. 1955) ; cf. Scheuer

V. Rhodes, 416 U.S. 232 (1974).

25

of is the one, consistently rejected,26 contending that by

expressly providing for wrongful-death actions in § 6

of the Ku Klux Act (now 42 U.S.C. § 1986),27 Congress

implicitly evidenced its desire to deny wrongful-death

26 See, e.g., Hall v. Wooten, supra, 506 F.2d a t 568-69 n.3; Brazier

V. Cherry, supra, 293 F.2d a t 404.

27 Section 6 of the Ku Klux Act, 17 Stat. 13, originally provided

as follows:

That any person or persons, having knowledge that any of

the wrongs conspired to be done and mentioned in the second

section of this act are about to be committed, and having power

to prevent or aid in preventing the same, shall neglect or refuse

so to do, and such wrongful act shall be committed, such person

or persons shall be liable to the person injured, or his legal

representatives, for all damages caused by any such wrongful

act which such first-named person or persons by reasonable

diligence could have prevented; and such damages may be

recovered in an action on the case in the proper circuit court

of the United States, and any number of persons guilty of

such wrongful neglect or refusal may be joined as defendants

in such action: Provided That such action shall be commenced

within one year after such cause of action shall have accrued;

and if the death of any person shall be caused by any such

wrongful act and neglect, the legal representatives of such

deceased person shall have such action therefor, and may re

cover not exceeding five thousand dollars damages therein, for

the benefit of the widow of such deceased person, if any there

be, or if there be no widow, for the benefit of the next of kin

of such deceased person.

As codified in 42 U.S.C. § 1986, the wrongful-death provision of

the statute reads:

and if the death of any party be caused by any such wrongful

act and neglect, the legal representatives of the deceased shall

have such action therefor, and may recover not exceeding $5,000

damages therein, for the benefit of the widow of the deceased,

if there be one, and if there be no widow, then for the benefit

of the next of kin of the deceased. But no action under the

provisions of this section shall be sustained which is not com

menced within one year after the cause of action has accrued.

The “second section of this act” referred to in the original § 6 is

now 42 U.S.C. § 1985, insofar as it authorizes civil actions against

those affirmatively engaged in conspiracies to violate civil rights.

See generally Griffin V. Breckenridge, 402 U.S. 88 (1971).

26

actions under § l .28 This is more than the process of

28 As we point out in the text following this note, § 1 of the Act

was not the cause of most of the controversy during the Ku Klux

debates. Hence, it is very tenuous to draw inferences about § 1 from

what happened with other parts of the bill, especially § 6. The Act

originated in the House as H.R. 320, where it passed and was sent

to the Senate by a vote of 118 to 91. Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 1st

Sess. 522. During the course of the Senate debates, Senator Sher

man introduced an amendment which would have imposed civil liabil

ity for personal injuries and property damages resulting from the

conduct of “any persons riotously and tumultuously assembled to

gether” upon all of “the inhabitants of the county, city or parish”

wherein such injury or damage occurred. Id. at 663. The proposed

Sherman amendment also provided that such “riot damages” would

be payable “to the person or persons damnified by such offense if

living, or to his widow or legal representative if dead.” Id. This

was the first time a wrongful-death provision expressly appeared in

the Ku Klux Act or any of its proposed amendments, yet there is no

explanation for it. Although the Sherman amendment was adopted

in the Senate (by a vote of 39 to 25) without debate (id. at 705),

and was thus added to the Senate version of the Act, it ran into a

storm of opposition in the House, as outlined in Monroe v. Pave,

supra, 365 U.S. at 188-90. The House refused to concur in the

Sherman amendment, by a vote of 132-45, and the bill was referred

to House-Senate conference. Cong. G l o b e , supra, at pp. 725, 728.

A modified version of the Sherman amendment was worked out in

conference and sent to both the House and Senate. This revised

version (see id. at 749) provided that the actual wrongdoers must

also be joined in an action authorized by the amendment; it pre

vented, in Representative Shellabarger’s words, “a claimant entitled

to recover from resorting to property of individuals at all and con-

fin [ed] his right of recovery to the county or city in which the

mischief was done,” id. at 751; it provided that the city or county

would be liable only to the extent a judgment could not be satisfied

against the actual wrongdoers; and it continued the wrongful-death

authorization from the first version. The conference report contain

ing this revised version of the Sherman amendment again passed

the Senate (by a vote of 32-16, id. at 779), but also again failed in

the House (106 to 74). Id. at 800-01. A new conference was con

vened, and it was at this second conference that § 6 of the Act was

first proposed (see id. at 804). The second conference report con

taining § 6 (now 42 U.S.C. § 1986, see note 27, supra) ultimately