Lucy v. Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lucy v. Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama Brief of Appellants, 1953. fc63dcfe-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce3ddf84-f8e1-4cf2-9440-a90fa8eca82a/lucy-v-board-of-trustees-of-the-university-of-alabama-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

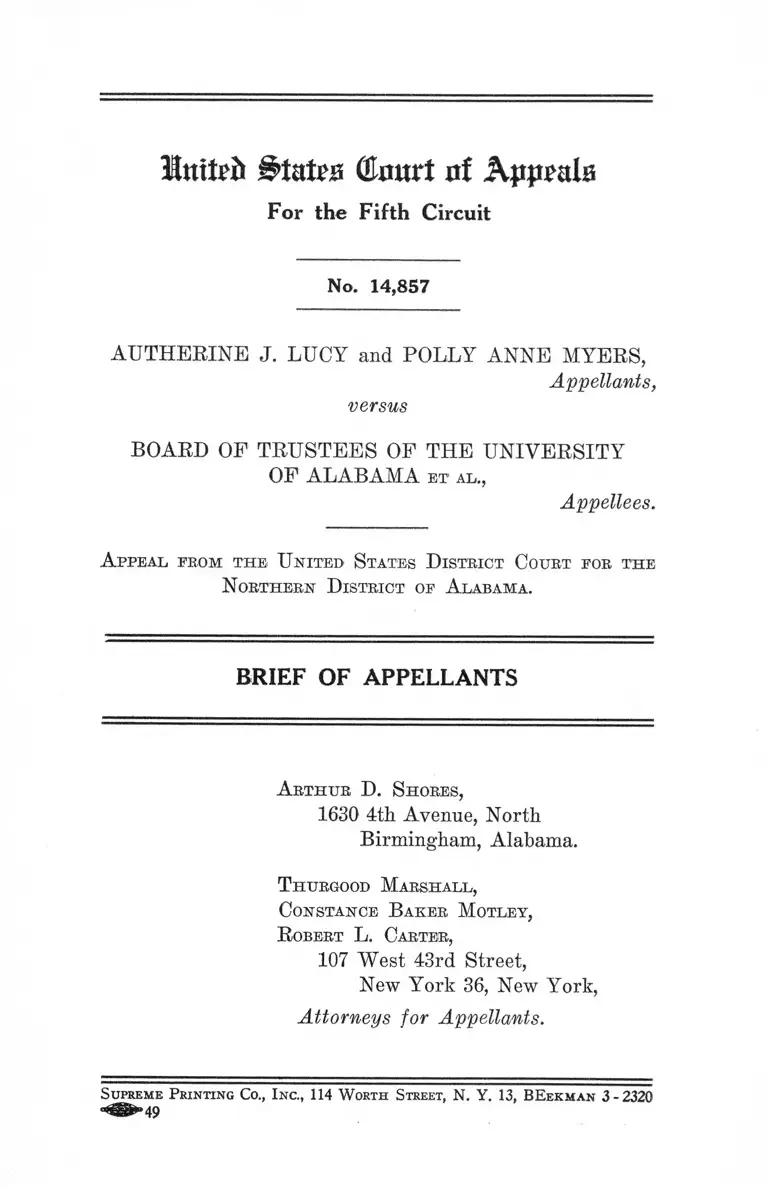

Intfrd States (Emtrt ni Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 14,857

AUTHERINE J. LUCY and POLLY ANNE MYERS,

Appellants,

versus

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE UNIVERSITY

OF ALABAMA et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal, eeom the United States D istrict Court for the

Northern District of A labama.

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

A rthur D. Shores,

1630 4th Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama.

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance B aker Motley,

R obert L. Carter,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3 - 2320

PAGE

Statement of the C a se ..................... ....... .. ' . . . . . . . . . . .

Statement of the Facts ................................. ..............

Questions Presented .........................................................

Specification of Errors ............................................. .. • • •

Argument ............................................................................

I—A suit against the Board of Trustees of the

University of Alabama for declaratory judg

ment with respect to alleged infringement of

constitutional rights and for injunction against

their violation is not a suit against the State of

Alabama .................................................................

A. No immunity from unconstitutional action ..

B. Criterion is relief sought...............................

II—A suit against the President and Dean of Admis-

missions of the University of Alabama for a

declaratory judgment with respect to alleged

infringement, of constitutional rights and for

injunction against their violation is not a suit

against the State of A labam a.............................

Conclusion .............................................................. ..

Table of Cases

Alabama Girls Industrial School v. Reynolds, 143

Ala. 579 (1904) .........................................................

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d

992 (C. A. 4, 1940) ..................................................... 10,

Barlowe v. Employers Insurance Company of Ala

bama, 237 Ala. 665, 188 So. 896 (1939) .................. 13,

1

2

5

6

7

7

8

9

16

18

11

18

14

11

PAGE

Burkley v. United States, 185 P. 2d 267 (C. A. 7,

1950).............................................................................. 11

Cook v. Davis, 178 F. 2d 595 (C. A. 5, 1950) ..........8, 9,10

12,18

Cox v. Board of Trustees of the University of Ala

bama, 161 Ala. 639, 49 So. 814 (1901 ).................. 13

Davis v. Cook, 55 F. Supp. 1004, 1007-1008 (1944) . . 8

Glass v. Prudential Insurance Company, 264 Ala.

579, 22 So. 2d 13 (1945) ..................................... 10,13,14

Hopkins v. Clemson Agricultural College, 221 U. S.

636, 55 L. ed. 890 (1911) .........................................8,9,18

Iowa-Des Moines Bank v. Bennett, 284 U. S. 239, 76

L. ed. 265 (1931) ......................................................... 8,17

Kansas City By. Company v. Daniel, 180 F. 2d 910

(C. A. 5, 1950) ............................................................ 8,9,18

Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Commerce Corp.,

337 U. S. 682, 93 L. ed. 1628 (1949) ..................... 8,9,10

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (C. A. 4,

1951) ...................................................................... 18

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637,

94 L. ed. 1149 (1950) ................................................. 17

Morris v. Williams, 149 F. 2d 703 (C. A. 8, 1945) . . . . 18

New York Technical Institute of Md. v. Lindbergh,

87, F. Supp 308 (1949) ............................................. 9

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631, 92 L. ed.

247 (1948) ................................................................... 18

Sloan Shipyard Corp. v. United States Shipping

Board Emergency Freight Corp., 258 U. S. 549,

66 L. ed. 762 (1922) ............................................... 9,18

State v. Clements, 217 Ala. 685, 117 So. 296 .............. 13

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 94 L. ed. 1114 (1950) 17

MnxUb Court of Appralfi

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 14,857

---------------------- o-----------------------

A utherine J. L ucy and P olly A nne Meyebs,

Appellants,

v.

Board of T bustees of the University of A labama, H ill

F erguson, Chairman of the Board, J ohn M. Galalee,

L ee B idgood and W illiam F. A dams,

Appellees.

-------------------- o--------------------

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court, Northern District of Alabama, entered

October 9, 1953, granting the motions to dismiss of the

appellees, defendants below, and dismissing the complaint

as to each of the appellees in this cause (R. 40-45).

The court below, in its opinion, ruled that this action

against the Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama

in its official capacity is a prohibited suit against the State

of Alabama (R. 43).

The court also ruled that the complaint does not show

any present actual controversy as to appellees Galalee

and Bidgood and that as to these parties, the complaint,

being against them in their official capacities, may not be

maintained (R. 43-44).

2

The court, in its opinion, ruled that as to defendant-

appellee Adams, the complaint, being against him for his

official acts rather than his acts in his individual capacity,

may not be maintained (R. 43-44).

Statement of the Facts

On July 3, 1953, appellants filed their complaint in the

court below against the appellees on behalf of themselves

and all other Negroes similarly situated with respect to

the matters here involved, alleging in part as follows:

Plaintiffs on September 9,1952 applied for admis

sion to the University of Alabama (R. 4).

Plaintiffs complied with all the rules and regula

tions entitling them to admission (R. 4).

That a room assignment was made by the Dean

of Admissions as shown by Plaintiffs’ Exhibits A

and B attached to and made a part of the complaint

(R. 4).

That plaintiffs received letters of welcome from

the President of the University, as shown by Plain

tiffs’ Exhibits C and D attached to and made a part

of the complaint (R. 4).

Plaintiffs appeared in person in the office of the

Dean of Admissions, William F. Adams, on Sep

tember 22, 1952 and after a conference with him he

informed plaintiffs that they would not be admitted

as students to the University (R. 4).

Plaintiffs applied to the President of the Uni

versity for admission and that the President of the

University refused the plaintiffs’ admission on ac

count of plaintiffs’ race and color (R. 4-5).

Subsequent to the refusal of admission by the

President, plaintiffs appealed to the Board of

Trustees of the University of Alabama to change

3

its policy, rules and regulations so as to admit plain

tiffs and other Negroes similarly situated (R. 5).

The Board of Trustees considered plaintiffs’

requests and applications for admission to the Uni

versity of Alabama and after said consideration

plaintiffs were notified by the Board that they were

denied admission to the University of Alabama and

that denial was based solely on plaintiffs’ race and

color (R. 5).

The defendants, who exercise overall authority

with respect to admission of students to the

University, have established and are maintaining a

policy, custom, usage and practice of denying to

qualified Negro applicants the right to be admitted

to the Schools of Journalism and Library Science of

the University of Alabama solely because of race

and color, and have continued the policy of refusing

to admit qualified Negro applicants into the said

schools, while at the same time admitting white appli

cants with equal or less qualifications than Negro

applicants solely on account of race and color (R. 5).

All of the defendants are sued in their official

capacities (R. 3).

The complaint prays a declaratory judgment that the

policy, custom, usage and practice of defendants in deny

ing plaintiffs, on account of race and color, and others

similarly situated, the right to enroll, enter and pursue

courses of study at the University of Alabama is a denial

of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and is, therefore, unconstitutional and void (R. 6).

The complaint prays the issuance of a permanent injunc

tion restraining defendants from denying plaintiffs and

others similarly situated the right to enroll and pursue

4

courses of study in journalism, library science and other

subjects at the University of Alabama, solely because of

their race and color (R. 7).

The defendant Board of Trustees of the University of

Alabama moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground,

among others, that the Board is a public corporation, an

instrumentality and agency of the State of Alabama, and is

not subject to suit under Article 1, Section 14 of the Con

stitution of the State of Alabama and that this action is

in reality a suit against the State of Alabama (R. 19).

The defendants John M. Galalee, Lee Bidgood, and

William F. Adams moved to dismiss the complaint on the

ground, among others, that it affirmatively appears that

this action is being brought against them in their official

capacities and that in such capacities they come under the

authority, supervision, control, and act pursuant to the

orders of the Board of Trustees of the University of Ala

bama, which is a public corporation, an instrumentality and

agency of the State of Alabama, which is not subject to

suit under Article 1, Section 14 of the Constitution of the

State of Alabama, and that therefore this action is in reality

against said Board of Trustees of the University of Ala

bama (R. 22, 24, 27).

These defendants also moved to dismiss the complaint

on the ground that it fails to show a case of actual contro

versy between each of them and the plaintiffs (R. 22, 24, 27).

The court below filed its opinion and order granting

the motions to dismiss on October 9, 1953 (R. 40-45). It

dismissed the complaint as to the Board of Trustees of the

University of Alabama on the ground that a suit against

it in its official corporate capacity is a suit against the

state (R. 43).

The court ruled that the complaint does not show any

present actual controversy as to the defendants Galalee

and Bidgood (R. 43).

5

It also ruled that as to those defendants and as to de

fendant Adams, the complaint does not purport to charge

them personally for any wrongful act—that it purports to

charge them only with acts officially committed—and that

it reveals that the acts that they are alleged to have com

mitted were all committed under authority, supervision,

control of, and pursuant to the orders and policies estab

lished by the defendant Board of Trustees of the University

of Alabama (R. 43).

The court ruled that as to any individual defendant,

otherwise properly in the case, it should not be difficult to

correct the infirmity referred to by an appropriate amend

ment averring that, in refusing plaintiffs’ admission to

the University, such officer was in fact acting personally,

although purporting* to act under color of office (R. 44).

The court dismissed the complaint as drafted as to each

of the defendant officials and in its order allowed plaintiffs

15 days within which to amend their complaint (R. 45).

From the order dismissing the complaint and directing

plaintiffs to amend their complaint, plaintiffs appeal (R.

46).

Questions Presented

I

Whether a suit against the Board of Trustees of the

University of Alabama is a suit against the State of Ala

bama where such suit is for a declaratory judgment that

the policy and practice of the Board in denying plaintiffs,

qualified Negro applicants, admission to the University of

Alabama solely because of their race or color, is in viola

tion of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment

to the Federal Constitution, and seeks an injunction re

straining the Board from denying plaintiffs, solely because

6

of race and color, the right to enroll and pursue courses of

study at the University of Alabama?

11

Whether a suit against the President and Dean of Ad

missions of the University of Alabama for a declaratory

judgment -that the policy and practice of these officials, in

their official capacities, of denying the plaintiffs the right

to enroll, enter, and pursue courses of study at the Uni

versity of Alabama solely because of the plaintiffs’ race

and color is in violation of the equal protection clause of

the 14th Amendment to the Federal Constitution, and seek

ing an injunction restraining these officials from denying

plaintiffs, solely because of their race and color, the right

to enroll and pursue courses of study at the University of

Alabama, is a suit which may not be maintained against

these officials in their official capacities because a suit

against the state?

Specification of Errors

I

The court below erred in dismissing the complaint on

the ground that the instant suit against the Board of Trus

tees of the University of Alabama in its official capacity is

a suit against the State of Alabama.

11

The court below erred in dismissing the complaint on

the ground that a suit against the President and Dean

of Admissions of the University of Alabama may not be

maintained against them in their official capacities because

a suit against the state and may be maintained against

them only in their individual capacities.

7

ARGUMENT

I

A suit against the Board of Trustees of the Univer

sity of Alabama for declaratory judgment with respect

to alleged infringement of constitutional rights and for

injunction against their violation is not a suit against

the State of Alabama.

The complaint in this action alleges that appellants ap

pealed to the Board of Trustees of the University of Ala

bama to change its policy, rules and regulations so as to

admit appellants and other Negroes similarly situated.

This appeal was made to the Board after appellants had

been denied admission to the University by the Dean of

Admissions, William F. Adams, one of the appellees herein,

and after the appellants had been denied admission, solely

because of race and color, by the President of the Univer

sity. The complaint alleges that the Board considered

appellants’ request to change its policy, rules and regula

tions and that after considering same, the Board notified

appellants that they were denied admission to the Univer

sity solely because of race and color (R. 4-5).

The complaint prays a declaratory judgment that the

policy, custom, usage and practice of the Board in denying

appellants and others similarly situated, the right to enroll,

enter and pursue courses of study at the University, solely

because of race and color, is a denial of the equal protection

of the laws guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States and is, therefore, unconsti

tutional and void (R. 6). The complaint prays a permanent

injunction restraining the Board from denying appellants,

solely because of race and color, the right to enroll and

pursue courses of study in journalism, library science and

other subjects at the University.

The complaint in this case thus alleges infringement of

constitutional rights, seeks a declaratory judgment against

8

the state agency which the complaint alleges has infringed

those rights, and seeks an injunction against the offending

agency. The question determinative of this appeal is

whether such a suit is in fact and effect one against the

State, thus permitting the offending agency to invoke the

sovereign’s immunity from suit.

A. No immunity from unconstitutional action

Where the suit is one against a state agency or official

alleging infringement of rights protected by the federal

Constitution, the state agency or official charged with viola

tion of constitutional rights may not invoke the sovereign’s

immunity from suit to defeat such action. See Larson v.

Domestic and Foreign Commerce Corporation, 337 U. S.

682, 690-691, 93 L. ed. 1628, 1636 (1949); Hopkins v. Clem-

son Agricultural College, 221 U. S. 636, 645, 55 L. ed. 890,

895 (1911); Davis v. Co oh, 55 Fed. Supp. 1004, 1007-1008

(1944); Cook v. Davis, 178 F. 2d 595, 599 (C. A. 5, 1950);

Kansas City Ry. Company v. Daniel, 180 F. 2d 910, 914

(C. A. 5, 1950).

Cases in which state officials have sought in vain to

invoke the sovereign’s immunity from suit in the face of

alleged infringement of constitutional rights are legion.

See Larson v. Foreign and Domestic Corporation, supra,

the dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter pp. 710,

712-713, 731, 1647-1648, 1658, where these cases are col

lected. But the truly basic question here involved is the

power of the federal courts to protect rights secured by

the federal constitution. Thus the state’s inherent or com

mon law immunity from suit and cases involving the ques

tion of what 'constitutes a suit against the state within the

meaning of the 11th Amendment to the federal constitution,

have no bearing. Iowa-Des Moines Bank v. Bennett, 284

U. S. 239, 245-246, 76 L. ed. 265 (1931).

9

B. Criterion Is Relief Sought

Nevertheless, in any case, specific relief against officers

or agencies of the sovereign may be obtained where such

relief is not in fact or in effect relief against the sovereign.

See Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Commerce Corpora

tion, supra; Sloan Shipyard Corporation v. United States

Shipping Board Emergency Freight Corporation, 258 U. S.

549, 66 L. ed. 762 (1922); Hopkins v. Clemson Agricultural

College, supra; Cook y. Davis, supra; Kansas City By. Com

pany v. Daniel, supra. Because where the relief sought is

not relief against the sovereign, the suit is not one which

must fail as against the state. This is the criterion estab

lished in all cases where a governmental official seeks to

invoke the sovereign’s immunity from suit. Larson v. For

eign and Domestic Commerce Corp., supra.

If the relief sought here were relief which would affect

an interest in property belonging to the State of Alabama,

then clearly the relief sought is relief against the sovereign.

Larson v. Domestic aoid Foreign Commerce Corp., supra.

I f the relief sought would result in compelling the State

of Alabama to exercise its sovereign powers of taxation or

legislation, or require it to pay out money in the public

treasury, then clearly the relief sought would be against

the State of Alabama in its sovereign capacity. Hopkins

v. Clemson Agricultural College, supra, at 642, 894 and

New York Technical Institute of Maryland v. Lindbergh, 87

F. Supp. 308, 313 (D. Md. 1949).

In the instant suit against the Board of Trustees of

the University of Alabama nothing is sought to be recovered

against the State of Alabama. No property interest of the

State of Alabama will be affected by the granting of relief

in this case. Neither will the granting of the relief prayed

compel the state to exercise any of its sovereign powers.

10

This suit against the Board of Trustees of the Uni

versity of Alabama is, therefore, not a suit against the

State of Alabama in name or in effect. It is a suit

against an agency of the State of Alabama which has

a separate corporate identity.1 The Board of Trustees

of the University of Alabama did not act in the name of

or for the State of Alabama in denying appellants admis

sion to the University of Alabama. It acted in its own

corporate name, according to the allegations of the com

plaint, and in its own corporate right as the agency of

the state which has been granted the power to admit

students to the University of Alabama. Like any other

officer or agency of the state which infringes upon rights

secured to an individual by the Constitution of the United

States, specific relief may be granted against the Board

of Trustees of the University of Alabama in the form of

a declaratory judgment, see, Glass v. Prudential In

surance Co., 264 Ala. 579, 584, 22 So. 2d 13 (1945), or in

the form of an injunction. See, Larson v. Domestic and

Foreign Commerce Corporation, supra, 690, 1636; see

Cook v. Davis, supra; Alston v. School Board of City of

Norfolk, 112 F. 2d 992 (CA 4, 1940).

The fact that the complaint alleges that the Board is

sued in its official capacity is not determinative of the

issue whether the instant suit against it is in fact and

effect a suit against the State of Alabama. Larson v.

Foreign and Domestic Corp., supra, at 687,1634. Therefore,

the fact that the complaint alleges that the suit is against

the Board in its official capacity is not a ground for dis

missal of the complaint.

The court below, in determining that the suit against

the Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama in

its official capacity is a suit against the State of Alabama,

failed to determine whether the relief sought was in fact

and effect relief against the State of Alabama. In this

1 Alabama Code 1940, Title 52, Section 486.

11

respect, the court below clearly committed error. The

court below looked only at the fact that the Board is sued

in its official capacity. This, as demonstrated, is not the

test and this Court must, upon this appeal, examine the

whole record to determine whether the appellants’ suit is

in fact one against the State of Alabama. BurJcley v. United

States, 185 F. 2d 267, 270-271 (C. A. 7, 1950).

A determination as to whether the relief sought is in

fact relief against the sovereign was the criterion used by)

the United States Supreme Court in the Larson case. In

that case the court found that the property sought to be

obtained by the Respondent was property belonging to the

United States and that Respondent sought by injunction

to enjoin the United States from selling or delivering

this property to anyone other than the Respondent. The

court, finding that the relief sought would affect an interest

in property belonging to the sovereign, ruled that the suit

must fail as one against the United States. That case is,

therefore, clearly distinguishable from the instant case

where no property belonging to the sovereign is sought to

be obtained, but where constitutional rights are sought to

be secured.

The Supreme Court of Alabama, in determining whether

a suit is one against the State in violation of Article I,

Section 14 of the Constitution of that State, has used the

same criterion. In Alabama Girls Industrial School v.

Reynolds, 143 Ala. 579, 583-586 (1904), the court, in decid

ing that a suit against the school was in fact against the

state said:

“ I f the suit instituted against it is practically

and really against the state—if the judgment and

decree obtained against it must be satisfied, if at all,

out of the property held by it, and this property'

belongs to the state, though the title is eo nomine

in the complainant as an agent of the state,— then

12

clearly to permit an action or suit against it would

be doing by indirection that which cannot be done

directly.”

In other words, if a suit against a state agency such as a

state school or university is one in which the judgment or

decree obtained against it must be satisfied out of the

property held by it and belonging to the state, or if some

right or interest of the state would be affected by the judg

ment or decree, then clearly the suit against the state school

or college cannot be maintained. But if, as in the instant

case, no property right or interest of the state will be

affected by the decree, the suit, even under this decision

of the Supreme Court of Alabama, may be maintained.

This Court, in Cook v. Davis, supra, 599 (1949),

decided the instant question in a situation similar to the

case at bar. In Cook v. Davis, the plaintiff Negro school

teacher sought to have public funds which had been duly

appropriated rightly paid out by the administrative officials

sued in that case. The administrative officials had, in

alleged violation of constitutional rights, improperly paid

out the funds appropriated by discriminating against plain

tiff in the payment of his salary by paying him less salary

than was paid to white teachers with the same qualifica

tions, experience, etc., solely because of the plaintiff’s race

and color. In that case the defendant state officials sought

to defend on the ground that the suit was one against

the state forbidden by the 11th Amendment to the Federal

Constitution. This Court ruled that the suit was not a

suit against the state for the reason that “ Nothing is sought

to be recovered against the state, nor is any right of the

State sought to be impaired. The validity of its statutes

is not even impugned. It seeks only to have public

funds which have been duly appropriated rightly paid out

by administrative officials according to law. The Eleventh

Amendment as interpreted in Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U. S.

1, 10 S. Ct. 504, 33 L. ed. 842, does not apply.”

13

In the instant case, nothing is sought to be recovered

against the State of Alabama, nor is any right of the State

sought to be impaired. The validity of the statutes of

the State of Alabama is not even impugned. The com

plaint seeks only to have the controlling public agency

and the administrative officials of the University of

Alabama admit the plaintiffs to the University in accord

ance with their duty to admit all qualified students. The

suit seeks in effect to compel the performance of a duty

which is purely ministerial. In State v. Clements, 217 Ala.

685,117 So. 296, the Supreme Court of the State of Alabama

ruled that the immunity of the state from suit under Article

I, Section 14 of the State’s Constitution does not exempt

state officers from the influence of judicial process to compel

the performance of a ministerial act.

The court below in its opinion cites three Alabama cases

as supporting its conclusion that the instant case is a suit

against the State of Alabama when brought against the

Board of Trustees in its official capacity and the individual

defendants in their official capacities; Cox v. Board of

Trustees of the University of Alabama, 161 Ala. 639, 49

So. 814 (1901); Barlowe V. Employers Insurance Company

of Alabama, 237 Ala. 665, 188 So. 896 (1939); Glass v.

Prudential Insurance Company, 264 Ala. 579, 22 So. 2d 13

(1945).

In the Cox case, the Board of Trustees of the University

of Alabama brought suit against an individual to recover

possession of certain lands allegedly owned by the Uni

versity. The question decided by the court was whether

the Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama was

the state for the purpose of applying to it a twenty-year

statute of limitations which applied to the state with respect

to such actions. There was no question of constitutional

rights involved and no necessity for the court to determine

whether a suit against the Board of Trustees of the Uni

versity of Alabama was, because of the relief sought, a suit

14

against the state. The language quoted by the court below

from that opinion has reference to the issue decided by the

court.

In Barlowe v. Employers Insurance Company of Ala~

bama, supra, no constitutional infringement of the plaintiffs

rights was alleged in the complaint. As a matter of fact,

no wrong or tort by the defendants in their official or indi

vidual capacity was alleged. The court, therefore, found

no equity in the case against the officials either in their

official or individual capacities. The court held that the

plaintiff had a. clear remedy at law in a suit against the

insurance company as third party beneficiary of the con

tract between the insurance company and the state officials

and that, therefore, the action for declaratory judgment

in that case could not be maintained in view of the avail

ability of another adequate remedy at law. The court did

not decide that if that case had been brought against the

Alabama State Highway Commission alleging infringement

of constitutional rights, by it or the members of the Com

mission in their official capacities, and seeking a declaratory

judgment and injunction, that such a case would be in effect

a suit against the State of Alabama.

In Glass v. Prudential Insurance Company, supra, the

court specifically construed a statute in such a manner as

to avoid a decision on whether Article I, Section 14 of the

Constitution of Alabama would be violated by a suit against

state officials in their official capacities. The court, desir

ing to uphold the statute to permit a suit against the

State Superintendent of Insurance to recover a tax paid

under protest, construed the statute as permitting a suit

against the state official in his individual capacity. The

court thereby avoided the issue presented by this case.

The Supreme Court of Alabama, however, in that case

specifically recognized that the weight of authority is that

a suit against state officials in their official capacity is not a

15

suit against a state forbidden by the Federal Constitution

where the suit is to enjoin state officers from enforcing

an unconstitutional law.

It also recognized that “ it is the nature of the suit or

relief demanded which the courts consider in determining

whether a suit against a state officer is in fact one against

the state within the rule of immunity referred to, and it

is not the character of the office or the person against whom

a suit is brought.” The court said that illustrative of

this is the Alabama case of Curry v. Woodstock Slag Gory.,

242 Ala. 379, 6 So. 2d 479, where a suit for declaratory

judgment was allowed against the state collector of internal

revenue. Quoting from the Curry case the court said:

“ When it is only sought to construe the law and

direct the parties, whether individuals or State offi

cers, what it requires of them under a given state

of facts, to that extent it does not violate Section

Fourteen, Constitution” (at p. 584).

In the instant case, appellants, in their complaint,

pray a declaratory judgment that the policy, custom, usage

and practice of the appellees in denying these appellants,

and others similarly situated, the right to enroll, enter and

pursue courses of study at the University of Alabama, on

account of their race and color, is a denial of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. They

also seek a permanent injunction restraining appellees from

denying appellants the right to enroll and pursue courses

of study at the University of Alabama when the denial is

based solely on race and color. Such relief seeks to have

the law construed, that is, the requirements of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. It seeks

to have the parties directed as state agents and officers. It

seeks to have determined what the law requires of these

16

state agents and officials in their official capacities. It

also seeks to enjoin appellees from unconstitutional dis

crimination. To this extent appellants maintain that a

suit against the Board of Trustees in its official capacity

does not violate Section Id, Article I of the Constitution

of the State of Alabama.

II

A suit against the President and Dean of Admis

sions of the University of Alabama for a declaratory

judgment with respect to alleged infringement of con

stitutional rights and for injunction against their vio

lation is not a suit against the State of Alabama.

The court below, in its opinion, ruled that since the

complaint against the individual appellees reveals that

the acts which they are alleged to have committed were all

committed under authority, supervision, control of and

pursuant to the orders and policies established by the Board

of Trustees of the University of Alabama and since the

complaint does not purport to charge these officers per

sonally on account of wrongful individual acts, the com

plaint as presently drawn must be dismissed as to each of

these officials (B. 43-45).

The complaint alleges that the appellants were refused

admission by Appellee Adams when they presented them

selves in person in his office as Dean of Admissions of the

University of Alabama (B. 4). The complaint alleges that

the President of the University denied appellants admission

to the University, appellants having appealed to the Presi

dent, and that his denial was based solely on appellants’

race and color (B. 4-5). A motion was filed by appellants

in the court below to substitute the present President of

17

the University as a defendant in this action on the ground

that there is a substantial need for continuing this action

against the present incumbent, in that he has adopted the

policy and practice sought to be enjoined (E. 30).

The complaint against these officials thus alleges that,

acting in their official capacities they have denied appel

lants ’ constitutional rights. In refusing appellants ’ admis

sion, these officials did not act as private citizens. They

acted as officials of the University of Alabama and, as the

complaint alleges, they acted under the authority, super

vision, control and pursuant to the orders and policies

established by the Board of Trustees of the University of

Alabama (E. 3).

Since the Board of Trustees of the University of

Alabama may not invoke the sovereign’s immunity from

suit in this instance, it follows that its agents may not

invoke such immunity, especially since the relief sought

against these officials is identical with the relief sought

against the Board and, as in the case of the Board, the

complaint against these officials alleges that they too in

fringe constitutional rights.

I f suing these officials in their official capacities was

the sole test for determining whether the instant suit is a

suit against the State of Alabama, then clearly the court

below was correct in dismissing the complaint as to each

of these officials and allowing the appellants time within

which to amend their complaint. But since this is not the

criterion, and since the action of these appellees must be

regarded as state action if the constitutional proscription

is to be invoked, Iowa-Des Moines Bank v. Bennett, 284

U. S. 239, 245, 76 L. ed. 265 (1931), it cannot be grounds for

dismissal that the complaint alleges that they are sued in

their official capacities.

In similar cases in which state officials sought to invoke

the sovereign’s immunity in suit alleging infringement of

constitutional rights, the state officials were sued in their

official capacities. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 94 L. ed.

1114 (1950); McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

18

IT. S. 637, 94 L. ed. 1149 (1950); Sipuel v. Board of Regents,

332 U. S. 631, 92 L. ed. 247 (1948); Sloan Shipyard Corp.

v. United States Shipping Board Emergency Freight Corp.,

258 U. S. 549, 66 L. ed. 762 (1922); Hopkins v. Clemson

Agricultural College, 221 U. S. 636, 55 L. ed. 890 (1911);

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (C.A. 4, 1951);

Cook v. Davis, 178 F. 2d 595 (C.A. 1950); Kansas City

Ry. Co. v. Daniel, 180 F. 2d 910 (C.A. 5, 1950); Morris v.

Williams, 149 F. 2d 703 (C.A. 8, 1945); Alston v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, 122 F. 2d 992 (C.A. 4,1940).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons appellants respectfully

urge that the order of the court below be reversed and

the case remanded for further proceedings.

Respectfully submitted,

A rthur D. Shores,

1630 4th Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama.

T hurgood Marshall,

Constance B aker Motley,

R obert L. Carter,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York 36, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.