Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Monroe v. City of Jackson, TN Board of Commissioners Brief for Petitioners, 1967. 4228c71d-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce449317-6dbf-4bcc-a2b7-f6fdf1b941bb/monroe-v-city-of-jackson-tn-board-of-commissioners-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

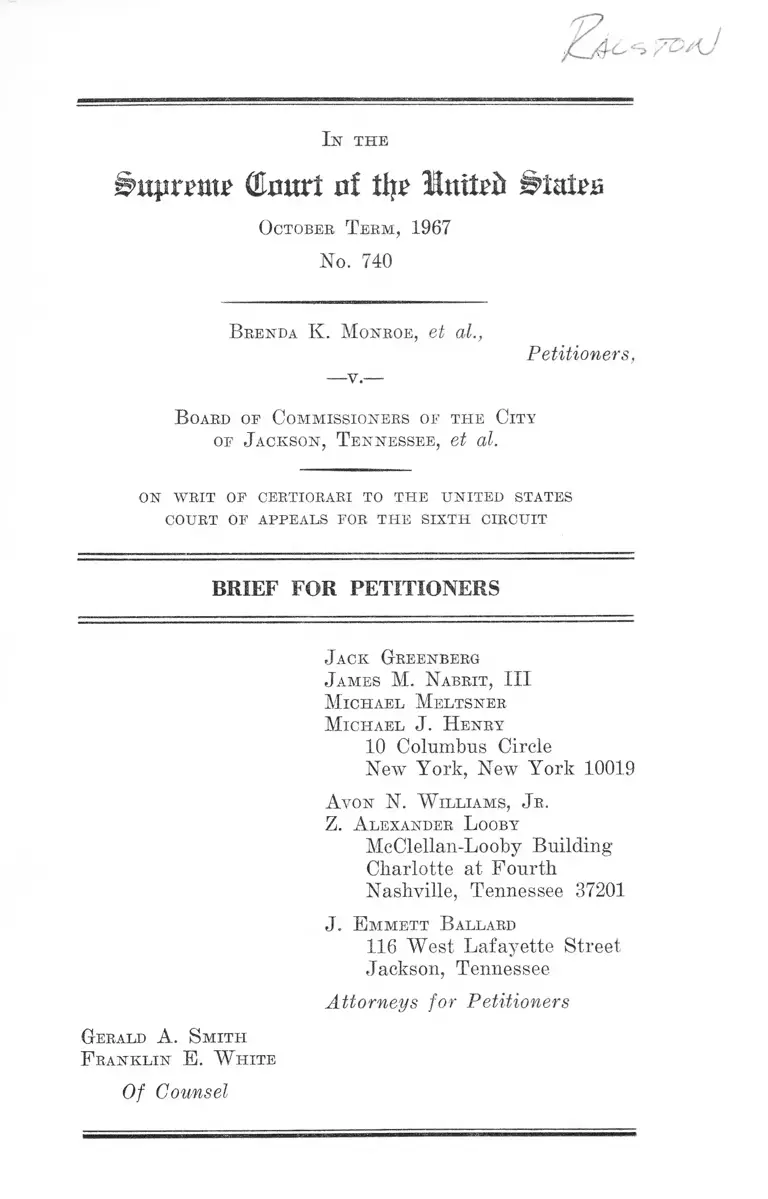

I n the

Hujirrmr (tort nf tiir liutri i>iatrs

October T erm , 1967

No. 740

B renda K. M onroe, et al.,

Petitioners,

B oard of Commissioners of the City

of J ackson, T ennessee, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TPIE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

M ichael J. H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams, J r .

Z. A lexander L ooby

McClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

J. E mmett B allard

116 West Lafayette Street

Jackson, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Gerald A . S mith

F ranklin E . W hite

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ......................... ... ............. 1

Jurisdiction ..... 1

Question Presented ..................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement of the Case .......... ... ................ ................. ..... 2

Summary of Argum ent............ ................. 18

A rgument—

Introduction............. 20

I. The Courts Below Applied an Erroneous

Legal Standard in Reviewing the Adequacy of

the Jackson Desegregation Plan ..................... 21

II. The Desegregation Plan Approved by the

Lower Courts Is Inadequate in That Peti

tioners Demonstrated That the Zoning and

Transfer Arragenments Were Not Designed

to Abolish the Dual System ............................ 30

Conclusion .......................................................................... 34

Cases:

T able of A uthorities

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967), cert. den.

387 U.S. 931, affirming Dowell v. School Board of

Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219 F. Supp. 427

(W.D. Okla. 1963), and 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D.

Okla. 1965) ................ .............................................19,25,29

11

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County (Fla.), M.D. Fla., Civil No. 4598, January

PAGE

24, 1967 ............................................................. ........... . 29

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ............. 17

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D. S.C. 1955)

16, 22

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ...............................3,17,18,20,21,22,

27, 28, 30, 33

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education

(Ala.), 253 F. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala. 1966) ............... 29

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ........ .................. 18, 20,24

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education (N.

Car.), 273 F. Supp. 289 (E.D. N.C. 1967) ................. 29

Corbin v. County School Board of Loudoun County

(Va.), E.D. Va., Civil No. 2737, August 27, 1967 ..... 29

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ...... 13,14

Kelley v. The Altheimer Arkansas Public School Dis

trict No. 22, 378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) ....18, 23, 29, 30

Kemp v. Beasley,------ F.2d — - (8th Cir. No. 19,107,

Jan. 9, 1968) .................................................................. 23,29

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ........... 27

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board (La.), E.D.

La., Civil No. 15973, October 19, 1967 .................. . 29

24Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ...

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .....

27

17

PAGE

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S. 110

(1948) ..................................................................... .......... 27

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 847 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed en banc, 380

F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert. den. 389 U.S. 840 ....18, 21,

22, 23, 24, 29

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910) .... 27

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d

768 (4th Cir. 1965) .......... ....................................... ....... 32

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............................................................ 1

42 U.S.C. §1983 ....... ...................... ...... .......... ................. . 2

Other Authorities:

“Racial Isolation in the Public Schools,” Report of the

United States Commission on Civil Rights (1967),

Yol. I ................................... ............ ...................... .......... 29

State of Tennessee, Department of Education, Equal

Educational Opportunities Program, Fall 1966 De

segregation Report on Tennessee’s Public Elemen

tary and Secondary Schools (compiled from reports

to the U. S. Office of Education) ..... ........................ . 17

In the

(Emtrt at tfye States

October T eem, 1967

No. 740

B renda K. M onroe, et al.,

Petitioners,

B oard of Commissioners of the City

of J ackson, T ennessee, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORAEI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOE THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Citations to Opinions Below

The district court’s opinion is reported at 244 F. Supp.

353, and is printed in the Appendix at pp. 365-389. The

opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 380 F.2d

955 and is printed in the Appendix at pp. 397-409. An

earlier district court opinion in this case is reported at

221 F. Supp. 968, and is printed in the Appendix at p. 33.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered July

21, 1967. The petition for writ of certiorari was filed Octo

ber 19, 1967, and was granted January 15, 1968. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. Section

1254(1).

2

Question Presented

Whether the courts below erred by approving a school

desegregation plan which failed to make reasonable pro

visions to abolish the dual school system, and by using a

standard for judging the plan which failed to recognize

the affirmative duty of the school board to disestablish the

segregated school system.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, and 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 providing a right of relief in equity for violations

of constitutional rights.

Statement of the Case

This is a school segregation case involving the public

schools of the City of Jackson, Tennessee.1 Jackson is a

small to medium-sized city in midwestern Tennessee, with

a school system of almost 8,000 students, about 60% white

and 40% Negro.2 As early as 1956, leaders of the Jackson

Negro community began petitioning the Board of Com

missioners to desegregate the schools in compliance with

this Court’s decision in the School Segregation Causes

1 An action seeking desegregation of the adjoining Madison County,

Tennessee school system is not involved in this petition. The county and

city school systems were sued in the same complaint, but the county and

city cases were severed and tried separately by the trial court. An

appeal involving the county schools was argued and decided in the Court

o f Appeals with this City case, but no petition for certiorari was filed

in the County case.

2 In 1964-65, there were 3,194 Negroes and 4,610 white pupils in the

system (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 26, A. 359).

3

(Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294)

(A. 357-358). They met with failure until the 1961-62

school year when the board admitted three Negro students

to a white school (A. 24). The following year (1962-63),

four more Negro students were admitted to a white school

(A. 24). Except for these 7 students, the 13 schools in the

system remained totally segregated in their student bodies

and faculties. In the elementary grades 1-6, there were

five white schools (Highland Park, Alexander, Whitehall,

Parkview and West Jackson) and three Negro schools

(Lincoln, South Jackson, Washington-Douglas). The jun

ior high school grades (7-9) were served by two white

schools (Tigrett Jr. High, Jackson Jr. High) and one

Negro school (Merry Jr. High). Grades 10-12 were served

by a white school (Jackson Senior High) and a Negro

school (Merry Senior High—located in the same building

with Merry Jr. High).

Petitioners, who are Negro pupils and parents in the

Jackson public school system, brought this action January

8, 1963, in the District Court for the Western District of

Tennessee. Their complaint alleged that the Jackson Board

of Commissioners operated a compulsory racially segre

gated school system with a dual system of white and Negro

schools, and that the individual plaintiffs had been dis-

criminatorily denied admission in white schools in violation

of their Fourteenth Amendment rights (A. 3). Petitioners

sought injunctive relief to enable the named plaintiffs to

attend specified white schools. In addition, they prayed

for an order for a “ complete plan for the prompt and

speedy reorganization of the entire systems of public

schools . . . into unitary, nonracial systems of schools . . .

[including] a plan for the assignment, education and treat

ment of students or enrollees on a nonracial basis, the as

signment and treatment of teachers, principals, . . . on a

4

nonracial basis, and the elimination of all and any other

discriminations in said systems . . . which are based on

race or color” (A. 22). The district court promptly, on

January 25, 1963, granted a preliminary injunction requir

ing the admission of the four plaintiffs to previously white

schools. The Board of Commissioners, by answer, denied

that the school system was segregated and asserted that

seven Negroes had been admitted to formerly all white

schools under Tennessee’s Pupil Placement Act (A. 23, 24).

However, the answer admitted that the Pupil Placement

Act was “not adequate as a plan for reorganizing' the

(City) schools into a nonracial system” (A. 25).

June 19, 1963, District Judge Brown granted plaintiffs’

motion for summary judgment and ordered the board to

file a desegregation plan (A. 27). The board filed a pro

posed plan July 19, 1963 (A. 29), and after an evidentiary

hearing the plan was approved with modifications in August

1963. (See 221 P. Supp. 968; A. 33-50.) The desegregation

plan (A. 29) as modified by the August 20, 1963, judgment

of the district court (A.42), provided for the elimination

of compulsory segregation rules in five stages with all

grades to be affected by the 1967-68 school year. As vari

ous school grades were desegregated, the plan provided

for the school officials to designate geographical attendance

areas to be served by each school. Pupils residing within

these areas had the right to attend the schools in their

zones (A. 30). Pupils already in schools were permitted

to remain where they were until graduation notwithstand

ing the new zones. Additionally, the school superintendent

was granted the power to “grant or require” transfers of

pupils to schools other than the school in their zones on

application or on his own initiative (A. 31-32). The court

also approved—over petitioners’ objections of gerryman

dering—the board’s school attendance zones for elementary

5

schools. The court held that the board “should have ad

ministrative discretion in establishing unitary zones, pro

vided that the zones do not clearly thwart the plan to bring

about abolition of discrimination” (A. 39), and that the

zones proposed “do not constitute an abuse of this discre

tion” (A. 40). The court directed (in accord with the plan

of gradual desegregation) that zone maps for junior high

schools and senior high schools be filed in 1965 and 1966,

respectively. In an addendum to the opinion (responding

to a new trial motion), the court reiterated its view that

the zones were not gerrymandered (A. 46).

After the desegregation plan had been in effect two

years, the five Negro schools remained all-Negro as before;

120 Negroes attended formerly white schools. The enroll

ments by race for the 1964-65 term were :s

Bldg. Negro White

Elementary Schools Capacity Pupils Pupils Total

Lincoln 875 709 0 709

South Jackson 525 589 0 589

W ashington-Douglas 525 434 0 434

Highland Park 700 0 590 590

Parkview 750 1 654 655

Whitehall 315 16 308 324

West Jackson 500 14 453 467

Alexander 750 87 628 715

Junior High Schools

Merry Jr. High 700 (+ 1 2 0 )4 752 0 752

Tigrett Jr. High 725 0 699 699

Jackson Jr. High 650 1 431 432

High Schools

Merry Senior High --------- 590 0 590

Jackson Senior High — 1 847 848

3,194 4,610 7,804

3 These enrollment figures are from Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 26 (A. 359-364);

building capacity figures are from A. 81-89, 143.

4 The board decided in the Spring of 1965 to construct 4 new rooms

to accommodate 120 more pupils at Merry.

6

In September 1964, when the plan was beginning* its

second year of operation, the Negro plaintiffs filed a Motion

for Further Relief and to Add Parties in which they at

tacked the administration of the plan’s transfer provisions

as racially discriminatory and again charged that the at

tendance zones were gerrymandered (A. 51). Twenty-seven

Negro children who complained that they had been denied

transfer to white schools were permitted to intervene as

plaintiffs, and the court ruled that plaintiffs could reopen

the gerrymandering issue, as well as a faculty desegre

gation prayer which had previously been deferred (Pre

trial order of 9/28/64; A. 92). The board filed a map

(reproduced at A. 105) proposing zones for the three junior

high schools and requested the court’s approval (A. 104-

105). Plaintiffs objected that the zone lines were drawn

to perpetuate racial segregation and asked that the board

be ordered to present new zones (A. 106). By a further

motion plaintiffs sought the desegregation of all remaining

grades in September 1965, and the elimination of discrimi

nation in teacher in-service training programs and extra

curricular activities (A. 109). The district court heard

evidence on these matters on May 28 and June 18, 1965

(A. 126-358).

The Superintendent of Schools, Mr. C. J. Huckaba,

testified that the elementary and junior high school zones

were prepared by considering such factors as the location

of the schools, the size of the buildings, the location of the

children and an effort to fit the number of students to

the capacity of the schools (A. 132). The petitioners pre

sented two experts in the field of education who testified

that the elementary and junior high school zones proposed

by the board were racially gerrymandered to achieve a

high degree of racial segregation. Petitioners’ experts were

Dr. Roger W. Bardwell, then Superintendent of Schools

7

of Elk Grove Township, Illinois, and Mr. Merle G. Her

man, then Assistant Superintendent of Schools in Villa

Park, Illinois.5 6 Dr. Bardwell and Mr. Herman conducted

a study (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 12) which was “designed

to discover if the school zone lines . . . have been so drawn

to obstruct the racial integration of the city’s schools” and

also to answer “whether the free transfer policy as admin

istered has fostered additional segregation in the schools”

(Exhibit 12, Introduction). The experts prepared a series

of exhibits, consisting of plastic overlay maps which may

be viewed in booklet form or projected on a screen by an

overhead projector (Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 12-21). The ex

hibits locate all pupils attending the schools by race on

maps showing the schools and zone lines. The procedure

used in preparing the exhibits was a standard method

which Dr. Bardwell said he used in presenting similar data

to his own Board of Education (A. 213). Dr. Bardwell and

Mr. Herman reached the following “conclusion” in their

study (Exhibit 12) :

“These exhibits represent an actual picture of the

total elementary school population and the total junior

5 Dr. Bardwell’s qualifications included B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees

from the University of Wisconsin in public school administration, fifteen

years’ experience in school administration, and substantial experience in

school building planning and zoning. The school district where he had

been superintendent five years was approximately the same size as the

Jackson system (A. 207-208).

Mr. Herman’s qualifications included a B.A. from McKendree College,

and an M.A. and completion of most doctoral requirements at Washing

ton University in St. Louis. His experience included three years’ public

school teaching, seven years’ public school administration, and ten years

college teaching in the field of education. During the period in which

he was a college faculty member, he participated in many school surveys

in a number o f different states, including zoning problems as part of

those surveys. The system where he was Assistant Superintendent was

also approximately the same size as the Jackson City school system (A

246-247).

8

high school population located on maps as near to the

pupil’s actual residence as possible. Elementary school

zone lines have also been indicated, as well as two ex

hibits (Nos. Y and V I) which depict the proposed

junior high school boundaries. It is possible to graph

ically examine the actual school zoning and attendance

situation in Jackson, Tennessee.

“Examination of this situation reveals:

(1) That elementary school attendance zones have

been gerrymandered to create racially segre

gated elementary schools.

(2) Proposed junior high school attendance zones

are also drawn to perpetuate racially segregated

schools at the junior high schools, grades 7, 8

and 9.

(3) The present transfer policy seems to mitigate

against desegregation of the Jackson schools.

Large number of white children living in pre

dominantly negro school zones have been per

mitted to transfer out of these zones to white

or predominantly white schools.”

The three junior high schools in Jackson had all been

constructed during the period after 1955 during which the

Board was operating a compulsory segregated school sys

tem contrary to the decision in the School Segregation Cases

(A. 232). Tigrett Jr. High, formerly all-white, is in the

western part of Jackson; Merry, still all-Negro, is in the

center of town; and Jackson Jr. High, formerly all-white,

is in the southeastern part of the city (A. 378). The zone

designated for the all-Negro Merry Junior High School

is an irregularly shaped area, described as “ sort of an

hour glass shape,” with a wide top, narrow center, and

9

wide bottom (A. 290), The lines were drawn “ consistently

between the Negro and white populations” (A. 291) and

the Merry zone thus included most of the Negro junior

high students but very few white students. The Bardwell-

Herman study concluded “ that the boundary zones for

junior high school attendance have been drawn with the

goal in mind to preserve racially segregated junior high

schools to a large degree” (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 12, see text

accompanying Exhibit V ).

In developing these zones, as well as the elementary

zones, the superintendent of schools apparently did not

undertake to find out how many junior high and elemen

tary students there were in the city and attempt to match,

the numbers of students to the capacities of the respective

schools, in spite of affirming that he used educational con

siderations such as capacity of schools in formulating the

zones. The only evidence of a count of students which

he was able to offer was a racial residential census of all

children aged 1-18 in the city, and not a count of relevant

age groups for junior high school and elementary school

zone planning (A. 129, 141, 145-146, 155, 162, 167, 182-183).

Analyzing a racial residential map of the city showing

the locations of the residences, and the race, of all junior

high students in the school system (Trial Exhibit 19, A.

211), plaintiffs’ educational expert Merle Herman con

cluded with regard to the junior high school zones: “ There

seems to be a very distinct tendency for the lines to fol

low the residences of Negroes and whites—in other words,

separating the two. Where there is a large Negro popula

tion, there tend to be lines drawn to maintain segregation

in the schools that serve those areas” (A. 250).

After the desegregated junior high school zones were

announced for the following year in late 1964, and after

10

the school system had discovered from the 1964-65 enroll

ment figures that all-Negro Merry Junior High School,

which then accommodated all but one of the Negro junior

high school students in the city, was over capacity, the

Board of Commissioners decided in the spring of 1965 to

construct four additional classrooms at Merry so as to

increase its capacity by 120 (A. 143, 184). This decision

was made despite the facts that (1) the enrollments of

the two previously all-white junior high schools were ap

proximately 300 students under capacity, and (2) the ele

mentary school enrollment figures indicated that total

junior high enrollment for the system would remain con

stant at about 100 students above the present enrollment

for at least the next four years (A. 143, 259-260).

When asked whether based on his experience no white

children could be expected to enroll in Merry Junior High

School and would it not therefore remain all-Negro, the

Superintendent of Schools said, “Judging on the basis of

what has happened up to now, that might be the case. . . .

I imagine it will be predominantly Negro” (A. 185-186).

He also expected that the small number of Negro students

from the other two zones of the heretofore all-white junior

high schools would continue coming to Merry, something

the board’s transfer policy would encourage (A. 186). The

superintendent attempted to justify the construction of

an addition to Merry Junior High by pointing out that

all-Negro Merry Senior High School (in the same build

ing), was growing and might need some of the rooms pres

ently used by the junior high school. But he also admitted

that the all-white senior high school (not yet then deseg

regated) was 249 students under capacity (A. 186).

With respect to the elementary schools, Dr. Bardwell

testified that his analysis showed that “ if geography were

the main criterion for the zoning of the schools, why most

11

all of the schools would be integrated with the exception

of Highland Park, and Lincoln would be predominantly

negro, but the balance of the schools would be integrated

to a much greater degree than they are” (A. 219-220; see

also, Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 12, text accompanying Exhibit

V II).

Dr. Bardwell was unequivocal in his observation about

the board’s proposed zones:

I said that the boundary lines were drawn so that the

majority of the schools remained highly segregated.

That was my conclusion. (A. 236)

Mr. Herman agreed (A. 254):

Well, the elementary school lines are built in such a

way that they tend to promote segregation. One can

never deal with the motivation behind them. It is just

an apparent type of thing that strikes you when you

look at the information that we have put together.

Plaintiffs proposed a specific plan for the junior high

schools which would have produced three integrated junior

high schools. Plaintiffs’ educational expert Merle Herman

explained that a standard basis for drawing junior high

school zones was the “feeder” principle. By this principle,

junior high school zones are based on elementary school

zones and are composed by clustering several such zones

so that all students from the same elementary school go

on to attend the same junior high school (A. 248-251, 255,

293-296).

Mr. Herman concluded that using the accepted “ feeder”

principle, the existing elementary schools in the city were

located so that they could be conveniently clustered into

12

zones to produce three completely integrated junior high

schools. The proposed feeder zoning plan was: (1) Park-

view (white), Washington-Douglass (Negro), and White

hall (white) elementary school zones to constitute the

zone for Jackson Junior High School; (2) Highland Park

(white), “West Jackson (white), and South Jackson (Negro)

elementary school zones to be the zone for Tigrett Junior

High School; and (3) Alexander (white) and Lincoln

(Negro) elementary school zones to be the zone for Merry

Junior High School (A. 255, 293-296). Each elementary

school is located conveniently to the proposed junior high

school, and the capacities of the elementary schools were

matched to the junior high schools (A. 255, 293-296). Mr.

Herman concluded that by drawing the zones in accordance

with the “ feeder” principle, “ the junior high school zones

would be developed objectively, without regard to the racial

character of the neighborhood” and “ from an educational

point of view, it would be sound” (A. 255).

Transfer Policy. The original plan of desegregation ap

proved by the district court in 1963 (A. 371-372) provided

that any transfer policy could be adopted as long as it did

not have as its purpose the delay of desegregation. The dis

trict court found in 1965 that the school system had ad

ministered its transfer policy in the following manner:

“They have allowed white pupils as a matter of course to

attend schools, outside of their unitary zones, in which

white pupils predominate, and have allowed Negro pupils

as a matter of course to attend schools, outside of their

unitary zones, attended only by Negroes but they have de

nied Negroes (and specifically intervening plaintiffs) the

right to attend predominantly white schools outside of their

unitary zones” (A. 372). In other words, the board was

using, up through 1965, the “minority to majority” racial

13

transfer policy which had been condemned by this Court

in 1963 in Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 (1963).6

Dr. Bardwell pointed out that where the Board had

zoned all of the schools in such a way that their enroll

ments were conspicuously either predominantly white or

almost all-Negro, and thus preserved the racial identity

of the schools as they were under the dual school system,

the availability of the free transfer option caused the racial

identification of the schools to become even more pronounced

by permitting the remaining students of the minority race

in each school to transfer out. He indicated that where

the school system had conferred racial identities on indi

vidual schools, it would be expected that minority students

would transfer out of those schools because they were of

the minority race and this was confirmed by the fact of

an abnormally large number of transfers within the sys

tem (A. 223-224, 238-239). Merle Herman pointed out that

the effect of a free transfer system superimposed on ra

cially identified schools would operate “ to maintain what

ever the attitude structure is of the people who have

children in those schools: and the attitude toward inte

gration was obviously unfavorable because of the large

number of minority to majority transfers (A. 249-250).

He explained: “ If zoning would not accomplish what some

people might consider to be a proper solution to their own

personal problems, they could then use transfer as a means

by which they could solve their problems” (A. 250). Mr.

6 Other aspects of the system’s transfer policy were also administered

in accordance with the principle of a segregated dual school system. The

Jackson city school system admitted 385 students from surrounding

Madison County and all white students were assigned to schools which

were all-white or predominantly white and all Negro students to schools

which were all-Negro (A. 255-257; Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 20). County trans

ferees of the predominant race in any particular school were apparently

given priority in assignment over city students of a minority race who

actually resided in the zone o f that school (A. 256-257).

14

Herman concluded that since “It is an accepted fact here,

I think, that white children attend white schools and Negro

children attend Negro schools,” that even though a com

pletely open transfer policy was superimposed on the

board’s junior high school zones based on race, “ segrega

tion will continue to exist” ( A. 253).

The Bardwell-Herman study of the junior high school

zones indicated how the transfer plan operated with the

zones to achieve segregation. As stated in the study (Plain

tiffs’ Exhibit 12, text accompanying Exhibit Y I ) :

This exhibit indicates the possibility of using an

open transfer plan to promote an almost completely

segregated school system at the junior high level be

cause of the gerrymandered school zone lines and rela

tively few children to be granted transfer to achieve

a high degree of segregation.

This “high degree of segregation” was achieved notwith

standing the fact that the white junior high school popula

tion “ distributes itself over the entire city” because the

Negro junior high population “distributes itself in the cen

ter of the city” (Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 12, text accompany

ing Exhibit Y ). When most of the Negroes in Jackson were

zoned into Merry Junior High zone, and the few whites

living in the zone were permitted to transfer out, an all-

Negro school was the result.

The district court rendered an opinion July 30, 1965

(A. 365; 244 F. Supp. 353), and an order on August 11,

1965 (A. 390). The court held that the board’s transfer

policy had been administered in an unconstitutional man

ner in violation of Goss v. Board of Education, 373 H.S.

683 (1963) (A. 372). The court ordered that if the defen

dants continue the policy of allowing all pupils transfers to

15

schools where they will be in a racial majority, they must

also allow pupils to transfer to attend schools where they

will be in a racial minority (A. 392-393). The court also

ordered that each pupil be required to register in the

school in his zone before applying for a transfer (A. 393).

Judge Brown ruled that some of the elementary school

zones “ appear to be gerrymandered” (A. 393) and ordered

that boundaries separating three pairs of white and Negro

schools be adjusted. Each adjustment resulted in placing

adidtional Negro pupils into formerly white zones. But, the

court rejected the claim that junior high school zones were

gerrymandered and approved the board’s proposed zones

(A. 394).

The court ordered that desegregation be accelerated

to cover all junior high grades in 1965-66 and all grades

in 1966-67 (A. 394). Belief requiring integration of

faculties was denied, except that the court ruled that in

1966-67 the board should seek teachers to volunteer for

non-segregated assignments (A. 394). Jurisdiction of the

cause was retained “ pending full implementation of de

segregation” (A. 396).

Judge Brown’s opinion began by stating that the law

was not clear “as to whether the Constitution requires only

an abolition of compulsory segregation based on race or

requires something more” (A. 366). He thought this a

question that “must first be answered before we can

deal with the assignment and transfer issue and the gerry

mandering issue” (A. 366), and after some discussion,

decided that segregation resulting from “purely volun

tary choice” or resulting from “ ‘honestly’ arrived at

geographical zoning” did not violate the Constitution:

“ the Constitution does not require integration . . . it only

requires the abolition of compulsory segregation based on

race” (A. 371). The court stated its reliance upon the

16

famous dictum of Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.

S.C. 1955).

Reasoning from this premise, Judge Brown disregarded

the testimony and desegregation proposals of plaintiffs’

experts because they sought “ integration” :

. . . [T]he value of the testimony of these experts was

undercut by the fact that they assumed that it is the

duty of defendants to maximize integration because

of educational benefits that would, in their opinion,

flow therefrom. The value of their testimony with

respect to elementary schools was further somewhat

undercut because their maps were aimed to show the

amount of de facto segregation that has resulted after

two years under the plan. However, in view of volun

tary transfers by white and Negro pupils, the degree

of actual segregation in these schools does not itself

show that the zones are gerrymandered. The value of

the testimony of these experts with respect to junior

high schools was somewhat undercut because they not

only again assumed a duty to maximize integration

but also assumed that defendants had the duty to adopt

a “ feeder” system whereby certain elementary schools

would send their graduates only to a particular junior

high. (A. 376)

The Negro plaintiffs appealed and the Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit affirmed except with respect to the

faculty segregation issue, on July 21, 1967 (A. 397). The

court below asserted that the:

. . . Fourteenth Amendment did not command com

pulsory integration of all of the schools regardless of

an honestly composed unitary neighborhood system

and a freedom of choice plan. (A. 399)

17

The court stated that the Brown decision prohibits “ only

enforced segregation” (id.), and that it would apply the

same rule it had applied in a Cincinnati case where the

schools were desegregated long before Brown (A. 399-400).

It said:

However ugly and evil the biracial school systems ap

pear in contemporary thinking, they were, as Jefferson,

supra [372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966)] concedes, de jure

and were once found lawful in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U.S. 537 (1896), and such was the law for 58 years

thereafter. To apply a disparate rule because these

early systems are now forbidden by Brown would be

in the nature of imposing a judicial Bill of Attainder.

(A. 400-401)

The court then stated its approval of the trial judge’s

decision that the junior high school zones were not gerry

mandered. The trial court decision refusing relief on the

faculty desegregation question was reversed and the issue

remanded for reconsideration in light of Bradley v. School

Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965), and Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S.

198 (1965).

The record herein contains no enrollment figures in

dicating the results of the plan’s operation while the case

has been pending on appeal. However, published data re

flects that during the 1966-67 school term, Jackson’s five

Negro schools remained all-Negro, while 475 Negro students

attended racially mixed schools and 2,730 remained in all-

Negro schools.7 In the current 1967-68 school year, 615

7 Respondents’ Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, p. 4, filed November

1967; see also, State of Tennessee, Department of Education, Equal Ed

ucational Opportunities Program, Fall 1966 Desegregation Report on

Tennessee’s Public Elementary and Secondary Schools (compiled from

reports to the U. S. Office of Education).

18

Negro students attend mixed classes while 2,613 are in all-

Negro schools.8

Summary of Argument

I. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

349 U.S. 294 (1955), directs the district courts to consider

the adequacy of school desegregation plans to eliminate

racial discrimination in public school systems. School

officials have an affirmative duty to initiate desegregation.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

The courts below applied an erroneous legal standard

in appraising the Jackson Board’s desegregation plans

by rejecting the argument of petitioners that the board

had an affirmative duty to abolish the dual system. School

segregation plans should be judged by whether they are

reasonably designed to convert dual systems into unitary

systems. Adequate plans should desegregate both formerly

all-white and formerly all-Negro schools. Jackson’s plan

left the all-Negro schools intact while permitting a few

Negroes to enter formerly all white schools. The courts

below appraised the plan and the evidence by reference

to a misconception of the applicable law which rejected the

notion that school boards are affirmatively obligated to

disestablish patterns created by the segregation laws and

practices. Other courts of appeals have applied more ap

propriate standards for appraising desegregation plans.

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 847 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert. den. 389 U.S. 840. Kelley v.

The Altheimer Arkansas Public School District No. 22,

378 F.2d 483 (8th Cir. 1967) ; Board of Education of Okla

8 Ibid.

19

homa City Public Schools v. Dowell, 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir. 1967), cert. den. 387 U.S. 931.

II. The desegregation plan proposed for Jackson, Ten

nessee, including particularly the junior high school zoning-

arrangements and the transfer plan, was not reasonably

designed to abolish the dual school system. Plaintiffs made

an unrebutted showing that the junior high school zones

were racially gerrymandered, and that the transfer policy

operated with the racial zones to insure a high degree of

segregation. The school board’s construction policies com

plemented the zoning arrangements to promote segrega

tion. Having found gerrymandering at the elementary

school level, the trial court should have treated the oddly-

shaped junior high school zones with great suspicion.

Plaintiffs proposed feeder plan would have desegregated

each of the city’s junior high schools. The court should

have ordered this plan or some other arrangement equallv

likely to desegregate the system. If the record is not

deemed sufficient to justify the immediate disapproval of

the board’s plan, at the least the trial court should be

dii ected to reappraise the case in view of the appropriate

standard, e.g. the requirement that school boards take

affirmative steps to abolish the dual system.

20

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This case presents important questions relating to the

implementation of this Court’s decision that racial segre

gation in the public schools violates the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955). In

the second Brown decision, swpra, the Court directed that

the lower federal courts “ consider the adequacy of any

plans that the defendants may propose . . . to effectuate

a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school sys

tem” . (349 U.S. at 301). Subsequently the Court empha

sized the affirmative duty of school authorities, saying that

they “were thus duty bound to devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation and bringing about the elimination

of racial discrimination in the public school system” .

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 7 (1958). The courts below,

in the instant case, approved a desegregation plan (pro

posed by local school officers and objected to by Negro

parents) holding that the plan fully complied with the

board’s obligations to implement Brown, supra. Petitioners

submit, first, that both courts below applied an improperly

restrictive legal standard for judging the adequacy of the

desegregation plan, by rejecting the idea that equity courts

are obliged to require affirmative efforts to abolish the

dual segregated school system. Second, it is urged that

the Jackson plan was demonstrated to be inadequate be

cause the school zoning and pupil transfer arrangements

were not reasonably calculated to abolish the dual system

which had been created under segregation laws and prac

tices. Alternately, it is submitted, that if the Court does

not find the plan inadequate on this record, at the least

21

the cause must be remanded to the trial court for re

appraisal of the plan’s features using a correct legal

standard.

I.

The Courts Below Applied an Erroneous Legal Stan

dard in Reviewing the Adequacy of the Jackson Deseg

regation Plan.

Both courts below deemed the definition of the basic

constitutional standard to be applied in reviewing a pro

posed desegregation plan to be the decisive matter at issue.

Petitioners’ position on this question has been variously-

stated and characterized by respondents and by the courts

below; we state it on our own terms in the following para

graph.

Because the Jackson school officials have established an

unconstitutional dual system of segregated schools, it is

their affirmative duty to abolish the dual system. Abolish

ing the dual system involves desegregating the all-Negro

schools as well as the all-white schools. The Brown de

cision held that “ segregation of children in public schools

solely on the basis of race . . . deprive [s] the children of

the minority group of equal educational opportunities.”

(347 U.S. at 493). “The governmental objective of [‘con

verting the dual system of separate schools for Negroes

and whites into a unitary system’ ] . . . is— educational op

portunities on equal terms to all.” 9 “ The criterion for

determining the validity of a provision in a school deseg

regation plan is whether the provision is reasonably re

lated to accomplishing this objective.” 10 It is not suffi

9 United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 380 F.2d 385,

390 (5th Cir. 1967).

10 Id.

22

cient for a court to consider merely the abstract constitu

tionality or reasonableness of a desegregation plan’s pro

visions. The Court should judge whether, when viewed

in a practical context, the provisions are reasonably cal

culated to abolish the dual system of white and Negro

schools speedily and effectively and to the greatest extent

feasible in the circumstances. Finally, the plan must be

tested in actual operation “by measuring the performance

—not merely the promised performance—o f school boards

in carrying out their constitutional obligation ‘to disestab

lish dual, racially segregated school systems and to achieve

substantial integration within such systems’ ” .u

We urge that these propositions are well supported by

decisions in the lower courts which have been congenial to

implementation of the Brown decision. The contrary posi

tion of the courts below should be repudiated. The essence

of the matter is that the courts below have declined to

accept the argument that the school board has an affirmative

duty to disestablish the segregated system.

The District Judge emphasized the well-known dictum

enunciated by Judge Parker in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.

Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955) six weeks after the second

Brown decision, that the Constitution “ does not require

integration” . Briggs sounded the call for resistance to

Brown. It was an attempt to narrow the scope of the

opinion so as to almost deprive it of meaning. Briggs

has been argued as the supporting foundation for almost

every evasive effort to subvert Brown which has come be

fore the courts. It has never been recognized in this Court,

and has quite properly been repudiated as inconsistent

with Brown in numerous recent cases in the courts of ap- 11

11 United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 847,

895 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert

den. 389 U.S. 840 (1967).

23

peals. See e.g. United Slates v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, supra, 372 F.2d at 846, 861-873; 380 F.2d at 389;

Kemp v. Beasley, ------ F.2d ------ (8th Cir. No. 19,107,

Jan. 9, 1968); Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas, Public

School District No. 22, 378 F.2d 483, 488 (8th Cir. 1967).

The holdings by the trial court reject the idea of an

affirmative obligation by the school board to abolish the

dual system in several ways. The court used its conclu

sion that the Constitution did not require “integration”

to justify its disregard of the careful study made by peti

tioners’ expert witnesses who testified that the Jackson

school zones were racially gerrymandered. Their presen

tation was disregarded because the Court thought their

testimony assumed the desirability of “ integration” . Simi

larly, the court, took the view that school board discretion

in establishing attendance zones “ should not be overridden

unless it constitutes a clear abuse of this discretion” (A.

46). The Court thus limited its inquiry about the zones

to a search for an abuse of discretion without any ex

pressed indication of concern for the practical impact of

the proposed zones on the separation of the races in the

school system. Uncontradicted evidence that the zone lines

maximized the racial separation was disregarded.

The trial court’s standard for appraising the desegrega

tion plan was seriously in error in that it failed to recog

nize that a prime objective of the desegregation plan must

be to accomplish the actual desegregation of the schools

and the elimination of the dual system. The trial court’s

view focused entirely on whether the desegregation plan

used non-racial and non-discriminatory mechanisms for

assigning pupils and disregarded the practical impact of

these rules on the pre-existing dual system. A principal

feature of the dual system is the existence of a number

of all-Negro schools. Obviously abolition of the dual sys

24

tem of separate white and Negro schools should include

desegregation of both sets of schools and the elimination

of racially identifiable schools. But the Court approved

a plan which was manifestly designed to preserve the all-

Negro schools intact, and rejected petitioners’ experts’

proposal to desegregate all junior high schools by a feeder

system, saying that their plan was intended to “ integrate”

the schools.

The Court of Appeals also characterized petitioners’

arguments as a demand for “compulsory integration” . The

Court said it was unfair and impermissible to impose a

duty on the Jackson school board which had established

segregation under the aegis of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U.S. 537 (1896), that was not imposed on a school board

that had no history of compulsory segregation. By so

defining the problem the Sixth Circuit also refused to

follow the legal rule stated in United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, supra, that there is an affirm

ative duty placed on school boards to devise plans to abol

ish the dual system.

The Court of Appeals approved the trial judge’s opin

ion which it said “ concludes that the Fourteenth Amend

ment did not command compulsory integration of all of

the schools regardless of an honestly composed unitary

neighborhood system and a freedom of choice plan” (A.

399). We think this formulation mistakes the crucial is

sues. The vital inquiry in appraising a plan intended to

implement the Broivn decision is not merely whether school

attendance zones are demonstrably dishonest. The central

inquiry ought to be whether the zones are reasonably de

signed to abolish the segregated system. If the Board’s

duty is to “ devote every effort toward initiating desegre

gation” (Cooper v. Aaron, supra, 358 U.S. at 7), surely

this duty must include something beyond merely refrain

25

ing from drawing dishonest, plainly arbitrary, or segre

gationist zones. There is a duty to make a reasonable

effort to actually desegregate those schools which the state

previously established and maintained for one race only.

Pupil transfer rules adopted as part of a desegregation

plan should also be required to meet a similar test. In

this case the trial court ruled that transfer applications

must be granted to all without discrimination and en

joined the board’s former practices which it said were

racially discriminatory. The court left it open to the Jack-

son system to continue a transfer arrangement by which

every white pupil zoned into a Negro school area trans

ferred out of his zone to a white school and thus perpetu

ated the all-Negro schools. Experience showed that every

white child who was zoned into a Negro school had sought

and been granted a transfer to a white school. Everyone

—all the parties and the courts below—fully understood

and expected that this pattern, which has held true through

out the south, would continue and that the all-Negro

schools would remain all-Negro notwithstanding the fact

that white pupils did live in the zones designated for

these schools. It was error, we submit, for the courts be

low to approve a transfer arrangement which was thus

manifestly designed and expected to defeat the objective

of eliminating the dual system.

The appropriate standard for appraising desegregation

plans is illuminated by Board of Education of Oklahoma

City Public Schools v. Dowell et al., 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir., 1967), cert. den. 387 U.S. 931, affirming Dowell et al.

v. School Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 219 F.

Supp. 427 (W.D. Okla. 1963) and 244 F. Supp. 971 (WJD.

Okla. 1965). The Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

was confronted with a school system which had announced

a formal desegregation plan by unitary zoning in 1955.

26

Nevertheless, the unitary zoning plan had preserved a

number of all-Negro schools because of racially designed

building locations, racial residential segregation, and a

racial “minority to majority” transfer plan. At the time

of the final district court decision in 1965, 80% of the

Negro students in the system were still attending schools

which were all-Negro or at least 95% Negro.

The Oklahoma district court, after ordering a study by a

panel of independent educational administrators, required

the school system to take specific and affirmative actions

recommended by the panel to begin the process of disestab

lishing segregation, including: (1) a consolidation of the

attendance districts and changes in the grade structures

of two pairs of nearby six-year secondary schools so as to

completely integrate the four schools, and (2) adoption of

a transfer plan by which any student who was in the racial

majority in any school in the system could transfer as a

matter of right to any other school in which he would be

in the racial minority. The Tenth Circuit held that “under

the factual situation here we have no hesitancy in sustain

ing the trial court’s authority to compel the board to take

specific action in compliance with the decree of the court

so long as such compelled action can be said to be neces

sary for the elimination of the unconstitutional evils

pointed out in the court’s decree.” 375 F.2d at 166.

Judge Lewis, concurring, explained the Court’s view that

since compulsion was used to maintain the system of seg

regation, the compulsion inherent in school assignment

policies could properly be used to disestablish segregation:

I have no quarrel with the statement that forced in

tegration when viewed as an end in itself is not a

compulsion of the Fourteenth Amendment. But any

claimed right to disassociation in the public schools

27

must fail and fall. I f desegregation of the races is to

be accomplished in the public schools, forced associa

tion must result, not as the end sought but as the path

to elimination of discrimination. And, to me, the argu

ment that racial discrimination cannot be eliminated

through factors of judicial consideration that are based

upon race itself is completely self-denying. The prob

lem arose through consideration of race; it may now

be approached through similar but enlightened consid

eration. 375 F.2d at 169.

In the second Brown decision, 349 U.S. 294 (1955), this

Court directed that “in fashioning and effectuating the

decrees [requiring desegregation], the courts will be guided

by equitable principles.” 349 U.S. at 300. The general

equity principle is that there is no wrong without a remedy,

and therefore equity courts have broad power to provide

relief and are obligated to do so. The test of the propriety

of measures adopted by such courts is whether the required

remedial action reasonably tends to dissipate the effects

of the condemned actions and to prevent their continuance.

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965). An example

of the application of this equitable principle is in the

antitrust area, where it has been held to require the com

plete dissolution of large national business enterprises

which had been created by illegal monopolization, when

there was no other way to counteract the effects of such

illegal monopolization. United States v. Standard Oil Co.,

221 U.S. 1 (1910); Schine Chain Theatres v. United States,

334 U.S. 110 (1948). Similarly, it has been held to require

that federal courts supervise the redrawing of state legis

lative districts when there is no other way to counteract

the effects of population disparities in existing state legis

lative districts. Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964).

28

As indicated above, decisions of the Courts of Appeals

for the Fifth, Eighth, and Tenth Circuits have held that

this equitable doctrine, as applied to the problem of remedy

for the unconstitutional creation and operation of a segre

gated public school system, requires a school board to

undertake affirmative action purposed to disestablish segre

gation completely, and that the standard for determining

the completion of desegregation is that the formerly Negro

schools must cease being identifiable as Negro schools.

The creation and operation of separate schools for Negroes

was the condemned action, and the test of the propriety

of remedial action to be required by a court is thus whether

it will disestablish the existence of the Negro schools, i.e.

integrate Negro students.

This Court suggested in the second Brown decision the

scope of school system policies which would have to be

changed in order to disestablish segregation, when it said

that “ to effectuate this interest may call for elimination of

a variety of obstacles,” and directed the district courts

supervising the re-organization of dual school systems to

“consider problems related to administration, arising from

the physical condition of the school plant, the school trans

portation system, personnel, revision of school districts, and

attendance areas into compact units to achieve a system

of determining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis, and revision of local laws and regulations

which may be necessary in solving the foregoing problems.”

349 U.S. at 300-301.

Since this Court’s announcement of the second Brown

decision in 1955, the lower federal courts have considered

and ordered a variety of specific remedies which constitute

affirmative actions and policies purposed to disestablish

29

segregation.12 See, e.g., United, States v. Jefferson County,

Board of Education, supra; Kelley v. Altheimer, supra;

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, supra; Carr

v. Montgomery County Board of Education (Ala.), 253

F. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala. 1966); Moses v. Washington

Parish School Board (La.), E.D. La., Civil No. 15973,

October 19, 1967; Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of

Education (N. Car.), 273 F. Supp. 289 (E.D.N.C. 1967)

appeal pending; Corbin v. County School Board of Loudoun

County (Va.), E.D. Va., Civil No. 2737, August 27, 1967;

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval County

(Fla.), M.D. Fla., Civil No. 4598, January 24, 1967.

With regard to the “ revision of school districts and at

tendance areas,” ordered by Brown II the Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit held in Jefferson County, supra:

I f school officials in any district should find that their

district still has segregated faculties and schools or

only token integration, their affirmative duty to take

corrective action requires them to try an alternative

to a freedom of choice plan, such as a geographic at

tendance plan, a combination of the two, the Princeton

plan, or some other acceptable substitute, perhaps

aided by an educational park. 372 F.2d at 895-896.

The Court thus made it clear that the school board’s as

signment transfer, building utilization, new construction,

and other policies must be specifically designed to integrate

the system and eliminate identifiable Negro schools.

12 A survey of various types of remedies for the disestablishment of

segregation is contained in the Report of the United States Commission

on Civil Rights, “Racial Isolation in the Public Schools,” (1967), Yol. I,

pp. 140-183. This survey was commended to the school board and the

district court by the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in Kemp v.

Beasley II, No. 19,017, January 9, 1968, slip opinion, p. 9.

30

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit adopted a

similar provisions in its decree in Kelley v. Altheimer,

supra.

II.

The Desegregation Plan Approved by the Lower

Courts Is Inadequate in That Petitioners Demonstrated

That the Zoning and Transfer Arrangements Were Not

Designed to Abolish the Dual System.

The school desegregation plan proposed by the Jackson,

Tennessee board, including particularly the junior high

school zoning arrangements and the transfer plan, fail to

meet a minimum standard of adequacy under Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294. The Jackson plan

should not have been approved because there was no

reasonable likelihood that the plan could effectively abol

ish the dual system of schools.

Petitioners’ evidence showed without dispute that the

junior high school zones proposed for the system were

drawn so as to preserve racially segregated junior high

schools to a large degree. They proposed a plan which

would have desegregated all three junior high schools.

There was no evidence which contradicted or impaired the

value of plaintiffs’ exhibit No. 20 (the same map as Ex

hibit V within the booklet marked overall Exhibit No. 12).

This map depicts all of the Negro and white pupils of

junior high school age in the city by race (Negroes in blue,

whites in red dots) and shows how they are distributed

in the city. The overlay containing the junior high school

zone lines shows plainly how a strangely shaped zone for

the all-Negro Merry school has been designed by the school

authorities to include most of the Negroes in the city and

exclude most of the whites. The racial effect of the junior

high school zones is readily apparent from an examina

tion of Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 20.

31

At the same time the school board proposed the junior

high school zones it took steps to enlarge the all-Negro

Merry Junior High School. This enlargement was plainly

designed to accommodate all of the Negroes in the city

at Merry, since Jackson Jr. High School had capacity for

better than 200 more students than were enrolled there,

and there was also excess capacity at Tigrett Junior High.

The racial purpose of this construction is further shown by

the fact that the board’s projections indicated no expected

large increase in the number of junior high school students

in the next four years.

The location of the three junior high schools (all of

which were opened in the years after Brown on a segre

gated basis), the enlargement of Merry Junior High to

accommodate continued segregation, and the planning* of

school zones separating white and Negro populations, all

make an unrebutted showing of school building and school

zone planning to perpetuate segregation.

The board’s free transfer device operates to permit an

even greater degree of segregation than could be accom

plished by the school zones. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 19 (the

same maps as Exhibit VI within the booklet Exhibit 12)

demonstrates how the use of the combination of gerry

mandered zoning and an open transfer plan at the junior

high level permits a high degree of segregation. The

exhibit indicates on map overlays the location of the resi

dences of pupils attending the three junior high schools.

(Note that the exhibits were prepared based on data in

December 1964 when the Junior High Schools were still

segregated by compulsion. The respondents arguments

that these exhibits are somehow based on an effort to prove

“ de facto” segregation are thus entirely specious.) Exhibit

19 shows how relatively few children had to be transferred

out of their zones to maintain a high degree of racial

32

separation. As we have discussed above, all of the ex

perience in Jackson, at the time this plan was proposed

showed that white pupils would transfer out of the all

Negro schools if free transfers were permitted, thus leav

ing the all-Negro school intact as a segregated school.

The district court found that there was gerrymandering

with respect to the zone lines of several elementary schools

proposed by the respondent board. The court ordered that

these zones be modified because of this apparent gerry

mandering. G-iven this finding that the respondent board

had once engaged in preparing school zone lines to per

petuate segregation, it was incumbent upon the district

court to scrutinize the newly proposed junior high school

zones all the more carefully. We submit that the trial

judge, having once found that the board was guilty of

gerrymandering with respect to certain proposed zones,

erred in failing to consider the irregularly shaped zones

proposed by the board for junior high schools to be greatly

suspect. It is submitted that the evidence plainly showed

the manipulation of school location, construction, and

zoning policies to maintain a high degree of segregation.13

This was sufficient to require disapproval of the board’s

proposed plan and for the trial court to have ordered the

adoption of the proposed feeder plan suggested by plain

tiffs’ experts as a method of actually desegregating all

three junior high schools within the framework of the

existing building locations, and grade structures, and build-

13 The availability o f a transfer option, however “ free” , does not

justify the continued practice of school assignments based on racially

gerrymandered zone lines. See Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Ed

ucation, 346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir. 1965) (Students assigned by racially

gerrymandered zones, then granted right to transfer out. Held: “ Chan

neling pupils into schools by a method involving discriminatory practices

and then requiring them, or even permitting them, to extricate them

selves from situations thus illegally created, will not be approved.” 346

f\2d at 772).

33

mg capacities. I f this feeder proposal was not adopted,

at the least the court should have required some alternative

method of assignment to be proposed by the board which

was equally as likely as the feeder method to actually

disestablish the dual system of junior high schools.

We urge that the evidence on this record is fully sufficient

to justify this Court in ruling that the plan approved below

was plainly inadequate under Brown. However, assuming

arguendo that the record is not sufficient to support a ruling

rejecting the plan as completely inadequate then the cause

should be returned to the District Court for reappraisal

in view of the proper standards for review of desegrega

tion plans as discussed in part I of the argument, supra.

The trial court’s view of the evidence, the alternative pro

posa ls made by petitioners’ experts, and the entire gerry

mandering and transfer plan issues was influenced by the

court’s too restricted view of the constitutional require

ment of desegregation.

34

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

court below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

M ichael J. H enry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams, J r .

Z. A lexander L ooby

MeClellan-Looby Building

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

J. E mmett B allard

116 West Lafayette Street

Jackson, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

Gerald A . S mith

F ranklin E. W hite

Of Counsel

MEitEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C « s» ^ s> 2 1 9