Henderson v. United States Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henderson v. United States Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1949. 714e99f3-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce48ae4e-4610-4a87-a4b6-0b95b23fa65d/henderson-v-united-states-motion-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

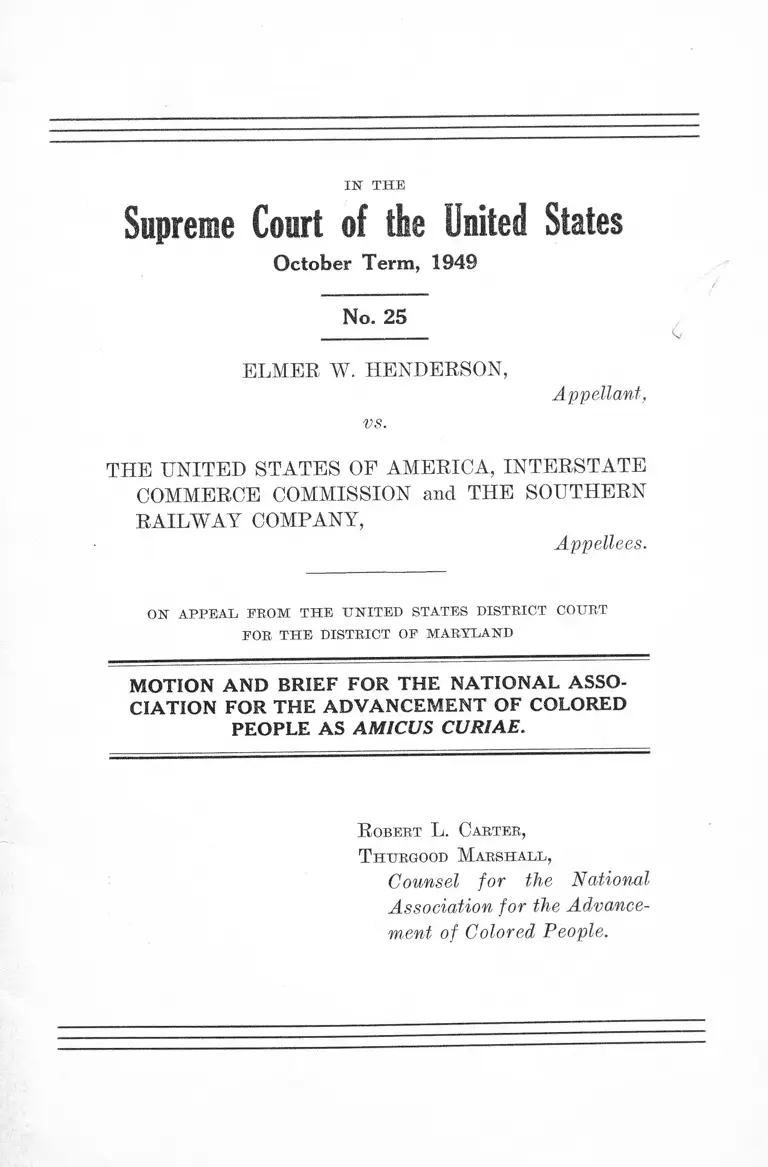

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. 25

__________ ___ <v

ELMER W. HENDERSON,

vs.

Appellant,

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, INTERSTATE

COMMERCE COMMISSION and THE SOUTHERN

RAILWAY COMPANY,

Appellees.

ON A P P E A L PR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D ISTR IC T COU RT

EOR T H E D ISTR IC T OF M A RYLAND

M OTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSO

CIATION FOR TH E ADVANCEM ENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE AS AM IC U S CU RIAE.

R obert L. Carter ,

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

Counsel for the National

Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amicus Curiae___ 1

Brief for the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People as Amicus Curiae___ ____ 3

The Opinions Below _____ 3

Jurisdiction___________________________________ 3

Statutes Involved _____________________________ 4

Statement of the Case __________________________ 4

Summary of Argument_______________________— 6

PAGE

Argument:

I. The present regulation violates the Interstate

Commerce Act________________________ 7

II. The present regulation constitutes a burden on

interstate commerce in the same manner and

to the same extent as the state statute which

was struck down in Morgan versus Virginia 15

III. Sanction of this regulation by the Interstate

Commerce Commission constitutes govern

mental action within the reach of the Fifth

Amendment________—------------------------ - 18

IV. The government is powerless under the Con

stitution to make, sanction, or enforce, any

distinctions or classifications based upon

race or color______________________ — 21

Conclusion 24

IX

T ab le of C ases C ited

Adelle v. Beaugard, 1 Mart. 183_________________ 16

Bob Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28_____ 20

Chicago R. I. & P. Ey. Co. v. Allison, 210 Ark. 54, 178

S. W. 401 (1915) _________________ ...__________ 17

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283 ____________________ . 20

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1 ___________________ ... 20

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. 8. 485 _____________________ 21

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 IT. 8. 81____—20, 21, 22

Hurd v. Hodge, 332 U. S. 2 4 ___________________ 21, 22

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214---------20, 21, 22

Lee v. New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182__ 16

Louisville & N. R. R. v. Ritchel, 148 Ky. 701, 147 S. W.

411 (1912) ___________________ ...____________ 17

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S.

151 ________ 1_______________________ 9 11

Missouri K. & T. Ry. Co. of Texas v. Ball, 25 Tex. Civ.

App. 500, 61 S. W. 327 (1901) _________________ 17

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80-----9,10,11,13,18, 20

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 _____ ...---------------- 15

Pennsylvania v. West Virginia, 262 U. S. 553, 596, 597 20

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ------------------------22, 24

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 _______________10, 21, 22

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631---------------- 11

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ------------------------ 21

State v. Treadway, 126 La. 300, 52 So. 500 — ...----------- 16

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192--------- 20

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 332 U. S. 410 21

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312--------------------------- 21

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and

Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210------- ------------------ 20, 21, 22

United States v. Screws, 325 U. S. 91.-----------— ------- 21

PAGE

Ill

S ta tu te s

Alabama Code, tit. 1, Sec. 2; tit. 14, Sec. 360 (1940)__ 16

Georgia Code, Sec. 2177 (Michie Supp. 1928)________ 16

Georgia Laws, p. 272 (1927)_____________________ 16

Interstate Commerce Act 10A, F. C. A., Title 49, Secs.

1(5), 3(1), 49 IT. S. C. A. Secs. 1(5), 3(1)___4,15,19, 20

Interstate Commerce Act 10A, F. C. A., Title 49, Secs.

1(13), 1(14), 49 U. S. C. A. Secs. 1(13), 1(14)___ 18,19

Interstate Commerce Act, 10 F. C. A., Title 46, Sec. 815,

46 U. S. C. A. Sec. 815_________________ A______ 20

Interstate Commerce Act, 10A F. C. A., Title 49, Sec.

484, 905 ______________________ ____ ________ 20

Louisiana Act No. 87 (1908)_____________________ 16

Louisiana Act No. 206 (1910)_____________________ 16

Louisiana Crim. Code, Arts. 1128-1130 (Dart 1932)___ 16

North Carolina Gen. Stat., Secs. 51-3,14-181 (1943)___ 16

North Carolina Gen. Stat., Sec. 115-2 (1943)________ 16

South Carolina Const., Art. I ll, Sec. 33 (1895)______ 16

O th e r A u th o ritie s

To Secure These Rights, The Report of the President’s

Committee on Civil Rights, IT. S. Government Print

ing Office, Washington, D. 0., 1947_____________ 23

PAGE

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term, 1949

No. 25

E l m e r W . H en d erso n ,

Appellant,

vs.

T h e U n ited S tates op A m erica , I n t e r

state C o m m erce C o m m issio n a n d T h e

S o u t h e r n R ailw ay C o m pa n y ,

Appellees.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS

AMICUS CURIAE.

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States and

the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

The undersigned, as counsel for the National Associa

tion for the Advancement of Colored People, respectfully

move this Honorable Court for permission to file the ac

companying brief as amicus curiae. Permission has been

secured from all parties with the exception of the interven

ing respondents, the Southern Railway Company, which has

refused its consent. (The letters in answer to our request

have been filed in the Clerk’s office.)

2

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People for the past 40 years has devoted itself to

the eradication of discrimination based on race and color

from all phases of American life. We are dedicated to the

belief that enforced racial separation is an ugly blot on

American democracy and, consequently, saps it of much

of its integrity. Our democracy is strong', not only because

of its material wealth, but because the concept of equality

and freedom for all has fired the hopes and aspirations of

the people of the world. In practice, however, we have

fallen far short of our preachments and we, as well as the

rest of the world, have become increasingly aware of this

fact. Either we must put our own credo into practice, or

we must admit that we cannot successfully make these be

liefs a part of our everyday life.

Prom time to time issues are presented to this Court

which require that this “ American dilemma” be honestly

resolved. This is just such an occasion. It is our belief

that the racial distinctions and discriminations which the

Southern Railway Company is now attempting to enforce

under its present regulations, and which the Interstate Com

merce Commission and United States District Court ap

proved, are invalid, humiliating to passengers both white

and Negroes alike, and directly contrary to the ideals of

democratic living to which this country is dedicated.

Robert L. Carter

Thurgood Marshall

Counsel for the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People.

IN T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term , 1949

No. 25

E l m e r W . H en d erso n ,

Appellant,

vs.

T h e U n it e d S tates of A m erica , I n t e r

state C o m m erce C o m m issio n a n d T h e

S o u t h e r n R ailw ay C o m pa n y ,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR TH E NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR

TH E ADVANCEM ENT OF COLORED PEOPLE AS

AMICUS CURIAE.

T he O pinions Below .

The first report of the Interstate Commerce Commission

(R. 184) is reported in 258 I. C. C. 413. The second report

(R. 4) may be found in 269 I. C. C. 73. The first opinion

by the three judge District Court (R. 63) can. be found in

63 F. Sup. 906, and its later opinion from which this appeal

is taken (R. 248) is reported in 80 F. Sup. 32.

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction of this Court to review on direct appeal

the judgment entered in this case is granted under Title 28

United States Code, Section 1253. Appellant’s appeal was

filed on November 17, 1948, and probable jurisdiction was

noted by this Court on March 14, 1949 (R. 266, 269, 278).

3

4

Statutes Involved.

Section 3, Subsection 1 of the Interstate Commerce Act

makes it unlawful for any carrier subject to the provisions

of the Act to make or to give any undue or unreasonable

preference or advantage to any particular person, company,

firm, corporation, association, locality, port, port district,

gateway, transit point, or any particular description of

traffic to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvan

tage in any respect whatsoever.1

Section 1, Subsection 5 makes it unlawful for any carrier

to make an unjust and unreasonable charge for services

rendered.2

Statem ent of the Case.

Appellant, a Negro, on May 17, 1942, was a Pullman

passenger on a train of the Southern Railway Company on

a trip from Washington, D. C., to Birmingham, Alabama,

as a field representative of the President’s Committee on

Fair Employment Practices. During the course of the

1 “It shall be unlawful for any common carrier subject to the pro

visions of this chapter to make, give, or cause any undue or unreason

able preference or advantage to any particular person, company, firm,

corporation, association, locality, port, port district, gateway, transit

point, or any particular description of traffic, in any respect whatso

ever or to subject any particular person, company, firm, corporation,

association, locality, port, port district, gateway, transit point, or any

particular description of traffic to any undue or unreasonable prejudice

or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever.”

2 “All charges made for any service rendered or to be rendered in

the transportation of passengers or property as aforesaid, or in con

nection therewith, shall be just and reasonable, and every unjust and

unreasonable charge for such service or any part thereof is prohibited

and declared to be unlawful: And provided further, That nothing in

this chapter shall be construed to prevent telephone, telegraph, and

cable companies from entering into contracts with common carriers

for the exchange of services.”

5

journey, appellant had occasion to seek services in the

dining car. At that time, the Southern Railway Company,

pursuant to a regulation, issued on July 3, 1941 and a

supplemental one issued on August 6, 1942, reserved two

tables at the end of the diner, adjoining the kitchen, for

Negro passengers for a certain time after the diner opened.

If no Negroes presented themselves during that period,

white passengers were then seated at these tables, and no

Negro passenger could thereafter be served until both

tables were no longer occupied by whites. Under no cir

cumstances were Negroes permitted to eat at any of the

other tables in the diner. If Negroes came to the diner

while both of these two tables were empty, they were seated

and curtains were drawn to separate them from the rest

of the car until they had completed their meal.

When appellant sought service, the two end tables were

then occupied by whites, and he was told that he could not

be served but would have to return later. There was, at

that time, available space at both tables and at other tables

in the diner. There is no question but that had appellant

been a white passenger he would then and there have been

seated and served. When appellant returned to the diner

for the second time, the two end tables were still in use,

and the dining car steward informed him that he would

send word back to his Pullman seat, when he could be served.

The steward failed to do this, and the diner was taken off

in Greensboro, North Carolina, without appellant having

been served at all.

A complaint was then filed with the Interstate Commerce

Commission alleging unequal treatment and unjust prej

udice and discrimination (R. 80). The Commission found

the allegations of the complaint had been sustained, but con

cluded that a future order would serve no useful purpose

and, therefore, dismissed the complaint (R. 184, 195). On

6

suit to set aside the Commission’s order the District of

Maryland set aside the order of the Commission on the

ground that the regulations did not afford the equality of

treatment which the Interstate Commerce Act required (R.

63).

Thereupon, the Southern Railway published a new regu

lation under which one table is reserved exclusively for

Negro passengers at the kitchen end of the diner and will

be set off by a wooden partition of approximately five feet

in height (R. 223). The Commission, with two members

dissenting in part, found that this new regulation provided

the equality of treatment which the Interstate Commerce

Act required and dismissed the complaint (R. 4-11). The

Court below affirmed in a two to one decision, and thereupon

appellant sought review in this Court.

Summary of Argum ent.

The regulation which has been approved as giving to

Negro passengers equal treatment required under statu

tory and constitutional provisions is both discriminatory

and unreasonable. Race alone is the basis for its existence.

The regulation requires governmental approval. The ap

proval of the regulation by the Interstate Commerce Com

mission is invalid on constitutional and statutory grounds.

What the carrier contends is that as a result of a survey,

it has found that the division of its diners among its white

and Negro patrons as provided under its regulation af

fords the Negro an equitable amount of space. However,

the Constitution and the Interstate Commerce Act require

that equal treatment be afforded the individual, and when

ever a Negro passenger is forced to remain standing when

he would have been served had he been white, his right to

equal protection has been invaded. Moreover, every pas

7

senger is entitled to equal treatment without governmen-

tally-enforeed racial segregation.

The carrier must, under the present regulation, deter

mine what it means by the term Negro. The term is sub

ject to varying conflicting statutory definitions, and would

subject interstate commerce to the same confusion and

burdens which caused this Court to hold state segregation

statutes burdensome to interstate commerce in the Morgan

case. Further, there is less reason for permitting the car

rier to make racial distinctions than there is for permitting

the states to do so.

The Interstate Commerce Commission sanctioned the

regulation and thereby gave to it government support. Our

national government is not permitted to make race or color

the basis for its action. Governmen tally-enforced racial

segregation serves no useful purpose. The “ separate but

equal” doctrine has never provided the equality required

by the Constitution. The requirement that Negro passen

gers, solely because of race, must be confined behind a

wooden partition from all other passengers in and of itself

is unequal treatment. Our Constitution prohibits such gov-

ernmentally-enforced segregation.

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The present regulation violates the Interstate Com

merce Act.

The present regulation sets aside a table for the exclu

sive occupancy of Negroes at the kitchen end of the dining

car while the train is going through those states where

segregation is required. From Washington to New York,

8

Negroes may be served on the same basis as any other pas

senger. If this regulation is upheld, the Southern Rail

way Company will install on all of its trains a wooden par

tition approximately five feet in height which will separate

this table and its Negro diners from the rest of the tables

and white passengers in the car.3 Negro passengers, re

gardless of their number, are required to eat at this table.

The rest of the diner is reserved exclusively for whites.

This arrangement was made pursuant to a purported sur

vey which showed Negroes to be approximately 3.48 per

cent of the persons using the diner of the Southern Railway.

(See Exhibits, R. 225-247.)

Since respondent’s position holds that the present regu

lation adequately protects Negroes against future discrimi

nation in dining car service, it is very relevant to determine

whether the new regulation will insure that the rights of

Negro passengers protected by the Interstate Commerce

Act will be safeguarded in all circumstances which may

3 “Transportation Department Circular No. 142. Cancelling in

struction on this subject, dated July 3, 1941, and August 6, 1942.

S u b j e c t : Segregation of White and Colored Passengers in Dining

Cars. To: Passenger Conductors and Dining Car Stewards. Con

sistent with experience in respect to the ratio' between the number of

white and colored passengers who ordinarily apply for service in avail

able diner space, equal but separate accommodations shall be provided

for white and colored passengers by partitioning diners and the allot

ment of space, in accordance with the rules, as follows: (1) That one

of the two tables at Station No. 1 located to the left side of the aisle

facing the buffet, seating four persons, shall be reserved exclusively

for colored passengers, and the other tables in the diner shall be re

served exclusively for white passengers. (2) Before starting each

meal, draw the partition curtain separating the table in Station No. 1,

described above, from the table on that side of the aisle in Station No.

2, the curtain to remain so drawn for the duration of the meal. (3) A

“Reserved” card shall be kept in place on the left-hand table in Sta

tion No. 1, described above, at all times during the meal except when

such table is occupied as provided in these rules. (4) These rules

become effective March 1, 1946. R. K. McClain, Assistant Vice-

President.”

9

present themselves in the future.4 Demonstration of the

inadequacy of the present regulation in any situation as

sures the conclusion that its sufficiency fails to meet the re

quirements of the Interstate Commerce Act. The present

regulation, therefore, must be tested in the light of any and

all reasonably foreseeable situations.5

The fundamental right to equality of treatment is a right

specifically safeguarded by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States,6 against the carrier

acting pursuant to state laws, and against the carrier acting

pursuant to privately promulgated regulations by the ex

press provisions of the Interstate Commerce Act.7 The

right of a Negro passenger guaranteed by these provisions

is the right to be served according to the same rules govern

ing all other passengers, a right accruing upon the pur

chase of the ticket. Where a Negro passenger applies for

service and is denied the same at a time when there is a seat

available, and is forced to remain standing while a white

passenger who subsequently applies is admitted to and

served in the same seat denied the Negro passenger, it is

clear that the Negro passenger has, on account of his color,

been subjected to a disability not suffered by white passen

gers, and a violation of the Act is patent.

4 It is to be noted that there has been no showing of a factual basis

demonstrative of the equality claimed to be afforded by the present

regulation. The division is based upon a survey made from May

14-24, 1945, and October 1-10, 1946, showing the number of Negroes

and whites using the dining car facilities of the Southern Railway (R.

225-247). While this gives some idea as to the approximate volume

of Negro patronage in the dining car, there are no means available

for determining how many Negro passengers will request service on a

particular trip, and the present regulation is insufficient to accommo

date an unanticipated volume of Negro traffic.

5 See first opinion of lower court in this case (R. 76).

6 McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151.

7 Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80.

10

Yet, this is what is accomplished under the present regu

lation as applied to a situation which may be reasonably

expected to occur. Where Station 1 is fully occupied by

Negro passengers, and Station 2 is wholly or partially occu

pied by white passengers, a Negro passenger then applying

for service is forced to wait, irrespective of the number of

vacant seats in the white section. A white passenger pre

senting himself for service, immediately after the refusal

of the Negro passenger, is served without delay.

Nor is it an answer to say that whites also have to wait

for seats on some occasions.7* The inquiry does not stop

at the situation where all seats in the dining car are taken,

or where both Negro and white passengers are standing;

the character of the right possessed by the Negro passenger

who stands while all whites are seated, and while there is

space for him in the “ white” section, clearly makes the

difference.8 Equal protection is not met by saying to the

Negro passenger applying for accommodations in a sleeper,

7a Equality of treatment is not granted because there is between

whites and Negroes an “indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.”

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22.

8 “We take it that the chief reason for the Commission’s action

was the ‘comparatively little colored traffic’. But the comparative

volume of traffic cannot justify the denial of a fundamental right of

equality of treatment, a right specifically safeguarded by the provisions

of the Interstate Commerce Act. We thought a similar argument with

respect to volume of traffic to be untenable in the application of the

Fourteenth Amendment. We said that it made the constitutional

right depend upon the number of persons who may be discriminated

against, whereas the essence of that right is that it is a personal one.

While the supply of particular facilities may be conditioned upon there

being a reasonable demand therefor, if facilities are provided, substan

tial equality of treatment of persons traveling under like conditions

cannot be refused. It is the individual, we said, who is entitled to the

equal protection of the laws—not merely a group of individuals or a

body of persons according to their numbers. And the Interstate Com

merce Act expressly extends its prohibitions to the subjecting of ‘any

particular person’ to unreasonable discriminations.” Mitchell v.

United States, supra, at page 97.

11

at a time when such accommodations are available to whites,

that he may travel tomorrow,9 nor is it accomplished by

telling the Negro student who seeks a legal education, at a

time when such facilities are immediately available to

whites, that he may study later.10 The conclusion seems in

escapable that the right to dining car service must be af

forded when the passenger presents himself, if facilities

for affording service are then available anywhere in the car.

Appellant is entitled to and seeks a guarantee of the

same service in every respect which is accorded white pas

sengers under like conditions. This includes, among other

things, the right to receive the same service and to be served

as expeditiously.11 Earlier regulations of the Southern

Railway fell short of affording this needed protection, and

it is believed that the inadequacy of present regulations is

equally clear.

A review of the history of regulations of the carrier as

to dining car service for Negro passengers demonstrates

the discrimination which has inevitably accompanied its

segregation policies. First in point is its practice of many

years’ duration of serving meals to passengers of different

races at different times, Negro passengers being served

either before or after the service of white passengers was

completed (R. 186). The fact that the period required for

the service of white passengers extended into the next meal

period, completely obliterated all possibilities of service of

Negro passengers and finally forced modification of this

practice as accomplished by its regulation of July 3, 1941,

which in turn was found lacking by the Commission and the

9 Mitchell v. United States, supra, at page 97.

10 Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631.

11 McCabe v. Atchison T. & S. F. Ry. Co., supra; Mitchell v.

United States, supra.

12

District Court.12 The supplemental regulation of August

6, 1942, in force at the time appellant was refused service

met the same fate in court.13 * * * * 18 Experience as to the regu

lations of the carrier demonstrates that only by a wide and

radical departure from its practices pursuant to its previous

regulations will illegal discriminations be avoided. It is

apparent, however, that no such change is sought to be

accomplished by the regulation under inquiry. The inade

quacy of the regulation under consideration becomes more

apparent when examined in light of its inflexible character,

even though there is a variance in the number of Negro

passengers travelling on a given train or seeking service

in a particular diner. No matter how many Negro passen

gers seek or desire service in the dining car, no matter

whether they seek service singly, in couples or in larger

12 Dining Car Regulations at R. 186: “Meals should be served to

passengers of different races at separate times. If passengers of one

race desire meals while passengers of a different race are being served

in the dining car, such meals will be served in the room or seat occu

pied by the passenger without extra charge. If the dining car is

equipped with curtains so that it can be divided into separate com

partments, meals may be served to passengers of different races at the

same time in the compartment set aside for them.” As to this regula

tion the lower court said at R. 78: “The alternative offered the

Negro passenger of being served at his seat in the coach or in the

Pullman car without extra charge does not in our view afford service

substantially equivalent to that furnished in a dining car.”

18 Dining Car Regulations at R. 186: “On August 6, 1942, these

instructions were supplemented as follows: Effective at once please

be governed by the following with respect to the race separation cur-

trains in the dining cars: Before starting each meal pull the curtains

to service position and place a ‘Reserved’ card on each of the two

tables behind the curtains. These tables are not to be used by white

passengers until all other seats in the car have been taken. _ Then if

no colored passengers present themselves for meals, the curtain should

be pushed back, cards removed and white passengers served at those

tables. After the tables are occupied by white passengers, then should

colored passengers present themselves they should be advised that

they will be served just as soon as those compartments are vacated.

‘Reserved’ cards are being supplied you.” This regulation was also

found inadequate by the lower court (R. 63).

13

groups, under respondent’s present regulation the same dis

position must be made in each instance. They must wait

until there is room at the single table for four reserved

exclusively for their benefit behind the wooden partition.

In each of these situations it appears that the number of

seats then available in the white section is immaterial since

under no circumstances will the overflow demand of Negro

passengers waiting for dining car service be taken care of

except at the table for four.

Such situations will, in the very nature of things, con

stantly present themselves, and their proposed disposition

by respondents is intolerable. Incessant delays in obtain

ing a seat at this one table are inevitable, and for many

Negroes the procuring of a seat will be impossible. For

those who are fortunate enough to obtain a seat, there will

remain the consequent lack of expediency in service. The

exercise of the privilege of dining with one’s friends, a

matter of course among whites, becomes for the Negro an

extraordinary accomplishment. When the seats reserved

exclusively for Negroes are in use and seats reserved for

whites are empty, it is clear that a Negro seeking service in

respondent’s diner, on being denied such service at one of

the empty seats, has been afforded discriminatory treat

ment on the basis of race and color in violation of the Inter

state Commerce Act.14

The best that can be said for this regulation is that it is

based on a very limited survey indicating the habits of a

racial group made with respect to the use of the dining car

service. However, the Interstate Commerce Act and the

Constitution secures and protects individual rights, and

where an individual is discriminated against the Act and

the Constitution is violated regardless of how accurate or 14

14 See Mitchell v. United States, supra.

14

exact may be the arrangement regarding the group with

which he is identified. We believe that the carrier’s past

regulations show that the equal treatment to individual pas

sengers which the Interstate Commerce Act requires, can

not be secured except under an arrangement whereby all

passengers, regardless of race and color, have the same

accommodations, service and treatment available. The only

rule governing the availability of accommodations should

be the democratic rule of “ first come—first served” rather

than consideration of race and color.

When appellant bought his ticket for a journey over the

Southern Railway between Washington, D. C., and Birming

ham, Alabama, in addition to his seat and berth in a Pull

man car, he was entitled to all other services and accom

modations incident thereto, including the right to dine in

the carrier’s diner. The record shows that pursuant to

regulations then in force, appellant was not permitted to

eat in the dining ear because of his race and color. White

persons, on the other hand, paying the same charges and

fare, were permitted to dine in the diner as a matter of

course. It is now not disputed that appellant was subjected

to an undue preference and prejudice proscribed under Sec

tion 3 of the Interstate Commerce Act. The further con

clusion is equally inescapable that white persons received

greater service, comfort and convenience than appellant and

other Negro passengers, paying the same charges and fare

and entitled in all respects to like accommodations, comforts

and conveniences. Clearly this is a basis for inquiry con

cerning the reasonableness of the fare exacted as required

under Section 1. Further there can be no doubt that ap

pellant and other Negro passengers were receiving less ser

vice and comfort than whites paying the same fare and were

therefore being charged greater compensation for the trans

portation than were white passengers.

15

Under the new regulation which was the subject of fur

ther hearing before the Interstate Commerce Commission,

these violations have not been cured as indicated, supra.

Appellant and other Negro passengers who are using, or

who in the future will use, respondent’s train are and will

be subjected to undue prejudice and disadvantage, will re

ceive less service, comfort and convenience than white per

sons paying the same fare. Appellant contends that this

disproportion amounts, and will amount, to a violation of

Section 1 (5) as well as Section 3 of the Act.

II.

T he present regulation constitutes a burden on in

terstate com m erce in the sam e manner and to the sam e

extent as the state statute w hich w as struck dow n in

M organ versus Virginia.

The same factors which influenced this Court in declar

ing that the states are without authority to require the sepa

ration of races in interstate commerce are at work with

equal force when the effect of a carrier regulation enforcing

such segregation is considered. In Morgan v. Virginia,10

this Court found that one of the main vices of giving effect

to local statutes enforcing segregation in interstate com

merce was the difficulty of identification.15 16 That difficulty

is no less when the separation is attempted under a carrier

regulation rather than under a state statute.

The carrier in order to enforce the present regulation

must define what is meant by the term “ Negro” or

“ colored” person. Appellant, in the instant case, travelled

through five states, Virginia, North Carolina, South Caro

15 TT S ^7 ^

Ibid at pages 382, 383.

16

lina, Georgia and Alabama en route to his destination,

Birmingham. In Virginia, Georgia and Alabama the term

“ Negro” or “ colored” person includes all persons with any

ascertainable amount of Negro blood.17 In North Carolina

this term embraces all persons with Negro blood to the third

generation inclusive,18 whereas in South Carolina % or

more of Negro blood is enough to classify one as a “ Negro”

or “ colored person” .19

If, therefore, the carrier attempts to enforce the pro

posed regulation in accord with state policy, it will have to

adopt the definitions of all states along the route over which

the suggested regulation is to operate.

The record does not show that the carrier here involved

has at any time attempted to formulate a definition or test

by the application of which a passenger may be determined

as a white person or Negro within the meaning of the

regulation in question. But even if this were so, the situa

tion would not be helped. The carrier regulations would

17 Ga. Laws, 1927, page 272; Ga. Code (Michie Supp.) 1928, Sec.

2177; Va. Code (Michie) 1942, Sec. 67; Ala. Code, 1940, Title 1,

Sec. 2 and Title 14, Sec. 360.

18 N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Secs. 51-3 and 14-181 (marriage law) ;

but see N. C. Gen. Stat. 1943, Sec. 115-2 (separate school law) for a

different definition of the term.

19 S. C. Const., Art. I ll , Sec. 33 (intermarriage). If the trip were

continued to New Orleans, Louisiana, the rule is not clear. It was

first held that all persons, including Indians, who were not white were

“colored”. Adelle v. Bectugard, 1 Mart. 183. In 1910 it was held that

anyone having an appreciable portion of Negro blood was a member

of the colored race within the meaning of the segregation law. Lee v.

New Orleans G. N. Ry., 125 La. 236, 51 S. 182. In the same year,

however, it was decided that an octoroon was not a member of the

Negro or black race within the meaning of the concubinage law (La.

Act, 1908, No. 87). State v. Treadaway, 126 La. 300, 52 So. 500.

Shortly after the latter decision, the present concubinage statute was

enacted substituting the word “colored” for “Negro”. La. Acts, 1910,

No. 206, La. Crim. Code (Dart), 1932, Arts. 1128-1130. The effect

of the change is yet to be determined.

17

necessarily be even less precise in this regard than a state

segregation statute. It is also perfectly clear that, as be

tween different carriers and their respective segregation

regulations, there are bound to be a multiplicity of varia

tions of definitions of passengers as white and colored,

and a multiplicity of variations in the ascertainment of pas

sengers as white and colored. The dining car steward

makes the determination as to the race of a passenger who

seeks to dine in his car, and as between different stewards

there is bound to be variations in the enforcement of the

regulation. One steward might consider a passenger a

white person and another steward might consider the same

passenger a Negro within the meaning of the regulation.

One thing* is clear, whether the carrier follows the state

definitions or adopts its own, it makes itself subject to bur

densome litigation.20 Hence, it is clear that the proposed

regulation is as objectionable and as burdensome to com

merce as the Virginia statute voided in the Morgan case.

There is, moreover, even less reason for giving effect to

a carrier regulation than to a state statute. None of the

factors which are said to give validity to a legislative judg

ment which is expressed in segregation laws are operative

where carrier regulations are involved. If respondent fears,

as suggested before the Interstate Commerce Commission

and in the lower court, that the co-mingling of Negro and

white passengers will result in breaches of the peace, there

is no reason advanced to show* that the states along re

spondent’s route are without power to handle or control

20 See Louisville & N. R. R. v. Ritchel, 148 Ky. 701, 147 S. W.

411 (1912) ; Missouri K. & T. Ry. Co. of Texas v. Ball, 25 Tex. Civ.

App. 500, 61 S. W. 327 (1901); Chicago R. /. V P. Ry. Co. v.

Allison, 210 Ark. 54, 178 S. W. 401 (1915) where punitive damages

were afforded white persons for mistaken placement in colored coaches.

Regardless of the definition used the carrier will be liable in damages

unless its definition is a correct one as determined by the law of the

applicable forum.

18

such incidents and to protect respondent’s property.2051

National interests in maintaining commerce free of burdens

and obstructions, must prevail over carrier regulations as

well as state statutes. Hence under the rationale of the

Morgan case, it must logically follow that neither a state

nor a carrier has authority to burden interstate commerce

by the enforced segregation of passengers in interstate

commerce.

III.

Sanction o f this regulation by the Interstate Com

m erce Com m ission constitutes governm ental action

w ithin the reach o f the F ifth A m endm ent.

With the passage of the Interstate Commerce Act, the

Congress established the Interstate Commerce Commission

to exercise its authority with respect to interstate com

merce within the terms of the statute.

Under Section 1 (13) the Commission is authorized by

general or special orders to require all carriers by railroad

subject to the provisions of the Act to file from time to time

their rules and regulations with respect to car service, and

the Commission may in its discretion direct that such rules

and regulations be incorporated in their schedules showing

2°a yfor may we aqq js there any reason to anticipate trouble. The

Southern Railway is no local carrier but operates over one of the

main arteries of travel connecting the North and South. People from

states having civil rights statutes as well as those from states which

practice segregation use its facilities. Negro passengers, at least since

Mitchell v. United States, supra, have used its Pullman facilities with

out segregation and without any infractions of the law taking place.

Service in its diner without segregation will not force any white per

son who does not desire to sit down and eat with a Negro.

19

rates, fares, and charges for transportation and be subject

to any and all provisions of this chapter relating thereto.21

The Commission is further authorized under Section

1 (14) after hearing a complaint or on its own initiative

without complaint, establish reasonable rules, regulations

and practices with respect to car services by carriers by

railroads subject to this chapter.22

Under Section 3 (1) Congress has declared it unlawful

for any common carrier to make or give any undue or un

reasonable preference or advantage to any person.

Under Section 1 (5) the carriers subject to the Act are

required to charge reasonable and just rates for services.

The Commission has the authority and the duty of seeing to

it that these provisions are carried out, and it may deter

mine on its own initiative or on the complaint of an in

dividual party whether a purported regulation or a regula

tion in force is in keeping with the requirements of the Act.

From the decisions of this Court, it is clear that Con

gress intended to reach all forms of discriminatory prac

tices made by carriers subject to the Interstate Commerce

21 Sec. 1 (13) provides—Rules and regulations as to car service

to be filed, etc.—The commission is authorized by general or special

orders to require all carriers by railroad subject to this chapter, or any

of them, to file with it from time to time their rules and regulations

with respect to car service, and the commission may, in its discretion,

direct that such rules and regulations shall be incorporated in their

schedules showing rates, fares and charges for transportation, and be

subject to any or all of the provisions of this chapter relating thereto.

32 Sec. 1 (14) provides—Establishment by commission of rules,

etc. as to car service.—The Commission may, after hearing, on a com

plaint or upon its own initiative without complaint, establish reason

able rules, regulations, and practices with respect to car service by

carriers by railroad subject to this chapter, including the compensa

tion to be paid for the use of any locomotive, car, or other vehicle not

owned by the carrier using it, and the penalties or other sanctions for

non-observance of such rules, regulations or practices.

2 0

Act.23 Regarding such practices, it is clear that discrimi

nation because of race and color is prohibited. There is no

question but that Congress has therefore occupied the field

and that private or state regulations contrary to the con

gressional purpose must fall.24

23 Mitchell v. United States, supra, at pages 96, 97.

24 This has been the rule since Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat 1. In

this connection it seems important to note that while this Court on

occasion has questioned certain of its own earlier distinctions between

direct and indirect impositions, the fact that exercise of control over

interstate commerce is the purpose and objective of a questioned state

statute, and that its enforcement is achieved by interference with inter

state movement itself, militates strongly against the validity of the

statute. This is because such an impact necessarily involves some

invasion of the national interest in maintaining the freedom of com

merce across state lines. If this fact alone is not conclusive, it at least

suffice to establish the impropriety of the state regulation until and

unless it is shown that urgent considerations of local welfare take a

particular case out of the general rule. See Pennsylvania v. West

Virginia, 262 U. S. 553, especially 596, 597; Bob Lo Excursion Co. v.

Michigan, 333 U. S. 28, follows the same rationale. There it was felt

that commerce was so peculiarly local that there could in no respect

be an interference with the control of the United States over foreign

commerce. Further, this conclusion seemed to be reached by virtue

of the fact that the Michigan statute and public policy was found by

the court to conform to the national policy with regard to barring

distinctions and classifications based on race and color. On this point

the Court said in note 16: “Federal legislation had indicated a national

policy against racial discrimination in the requirement, not urged here

to be specifically applicable in this case, of the Interstate Commerce

Act that carriers subject to its provisions provide equal facilities for

all passengers, 49 U. S. C. A. Sec. 3 (1), 10A,_ F. C. A. title 49,

Sec. 3 (1), extended to carriers by water and air, 46 U. S. C. A.

Sec. 815, 10 F. C. A. title 46, Sec. 815 ; 49 U. S. C. A. Secs. 484, 905,

10A F. C. A. title 49, Secs. 484, 905, Cf. Mitchell v. United States, 313

U. S. 80, 85 L. ed. 1201, 61 S. Ct. 873. Federal legislation also com

pels a collective bargaining agent to represent all employees in the

bargaining unit without discrimination because of race. 45 U. S. C. A.

Secs. 151, et seq., 10A F. C. A. title 45, Secs. 151, et seqx, Steele v.

Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192, 89 L. ed. 173, 65 S. Ct. 226;

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive F. E., 323 U. S. 210, 89 L. ed.

187, 65 S. Ct. 235. The direction of national policy is clearly in ac

cord with Michigan policy. Cf. also Hirabayashi v. United States,

320 U. S. 81 L. ed. 1774, 63 S. Ct. 1375; Korematsu v. United States,

323 U. S. 214, 89 L. ed. 194, 65 S. Ct. 193; E x parte Endo, 323 U. S.

283, 89 L. ed. 243, 65 S. Ct. 208.”

21

The situation which wTas present when Hall v. DeCuir

was decided is present no longer.25 26 There it was felt that

state statutes that required equal treatment of passengers

in interstate commerce were burdensome on such com

merce and that private carriers were free to make their

own rules and regulations until such time as Congress had

spoken. Congress has now spoken.

It is the duty of the Commission to say whether a regula

tion provides equality of treatment, and the carrier regula

tions dealing with this subject matter are of no force or ef

fect without the sanction of the Commission. They can

only exist with the sanction of the government. In this case,

the Commission specifically approves the present regula

tion and this is clearly governmental action within the

meaning of the Fifth Amendment.26

IV.

The government is powerless under the Constitu

tion to make, sanction, or enforce, any distinctions or

classifications based upon race or color.

It has been the consistent opinion of this Court that the

Constitution requires that all persons similarly situated be

treated in a like manner.27 Thus, where legal distinctions

25 95 U. S. 485.

26 For full discussion of the concept of state action under the Four

teenth Amendment see United States v. Screws, 325 U. S. 91, and

particularly Mr. Justice R u t l e d g e ’s opinion at pages 113, 114, 115.

It is clear the same principle will determine whether there is govern

mental action under the Fifth Amendment. This issue was raised in

Hurd v. Hodge, 332 U. S. 24, but not decided because the court dis

posed of the problem without reaching the constitutional question.

27 See Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312; Skinner v. Oklahoma,

316 U. S. 535; Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 332 U. S.

410; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Hirabayashi v. United States,

320 U. S. 81 ; Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214; See also

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24; Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomo

tive Firemen and Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210.

are made as between persons or groups, such distinctions

must have a rational basis in order to avoid conflict with

either the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments. This

Court has consistently held that governmental distinctions

between persons based upon race or color are arbitrary and

unreasonable and cannot stand under the Constitution.28

Although the Fifth Amendment contains no equal protec

tion clause, it is no longer open to doubt that the United

States government is as limited in making race a basis for

a legislative enactment as are the states under the Four

teenth Amendment.28a It is also now clear from the deci

sions of this Court that the government cannot be a party

to the enforcement of racial distinctions and classifications

which are privately promulgated.29 Although Hurd v.

Hodge was decided without reaching this constitutional

question, it seems certain that this Court will find the fed

eral government bound by the same constitutional limita

tions which is found applicable to the states in Shelley v.

Kraemer.

Only under the rationale of Plessy v. Ferguson30 could

a contrary decision be reached. That decision gave birth

to the much criticized “ equal but separate” doctrine, under

which enforced racial separation is declared permissible

as long as the facilities available for Negroes are equal or

28 See cases supra, in note 27.

28a Hirdbayashi v. United States, supra; Korematsu v. United

States, supra; and Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen

and Enginemen, supra.

29 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

30 1 63 U. S. 537.

23

substantially equal to those available to whites.31 Of course

there can be no question of equal facilities in this case when

under the carrier’s present regulations a passenger who is

a Negro is forced to eat in isolation behind a wooden barrier

as if he were unclean or an untouchable.32 But for more

31 The Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights at

page 81. “This judicial legalization of segregation was not accom

plished without protest. Justice Harlan, a Kentuckian, in one of the

most vigorous and forthright dissenting opinions in Supreme Court

history, denounced his colleagues for the manner in which they inter

preted away the substance of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments. In his dissent in the Plessy case, he said: ‘Our Constitution

is color blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citi

zens. * * * ’ ‘We boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above

all other peoples. But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with a

state of the law which, practically, puts the brand of servitude and

degradation upon a large class of our fellow citizens, our equals before

the law. The thin disguise of ‘equal’ accommodations * * * will not

mislead anyone, or atone for the wrong this day done. I f evidence

beyond that of dispassionate reason was needed to justify Justice

Harlan’s statement, history has provided it. Segregation has become

the cornerstone of the elaborate structure of discrimination against

some American citizens. Theoretically this system simply duplicates

educational, recreational and other public services, according facilities

to the two races which are ‘separate but equal’. In the Committee’s

opinion this is one of the outstanding myths of American history for

it is almost always true that while indeed separate, these facilities dre

far from equal.’ ” (Italics supplied.)

82 The Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights at page

79. “Mention has already~been made of the ‘separate but equal’ policy

of the southern states by which Negroes are said to be entitled to the

same public service as whites but on a strictly segregated basis. The

theory behind this policy is complex. On one hand, it recognizes

Negroes as citizens and as intelligent human beings entitled to enjoy

the status accorded the individual in our American heritage of free

dom. It theoretically gives them access to all the rights, privileges,

and services of a civilized, democratic society. On the other hand, it

brands the Negro with the mark of inferiority and asserts that he is

not fit to associate with white people.” (Italics supplied.)

24

than 20 years this Court has shown an acute awareness of

the dangers and fallacies in ratio decedendi of Plessy v.

Ferguson and has moved further away from the philosophy

which that case expounded. There is now little doubt but

that government cannot now use race or color as a permis

sible basis for legislative or administrative action. Consti

tutional limitations in this regard are probably more strin

gent and inflexible when the national government is involved

than when there is a question of permissible state action.

The “ equal but separate” doctrine should be reexamined

and discarded.

Conclusion.

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

Distinct Court should be reversed and that the Interstate

Commerce Commission should be directed to enter an order

prohibiting- the railroad from requiring racial segregation

of its Negro dining car patrons.

Robert L. Carter

Thurgood Marshall

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae.