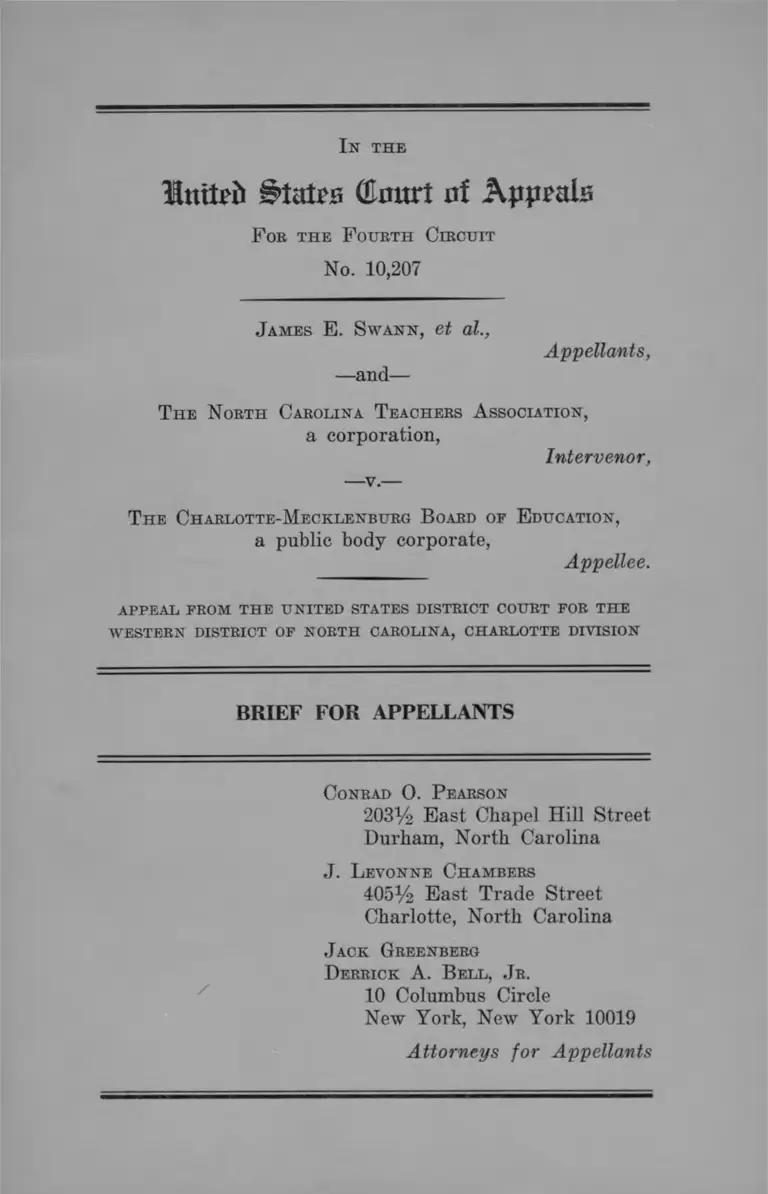

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1965. d47cb578-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce7cf685-4f54-4fb4-96b4-28e697f58a20/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

United (Eimrt of Appeals

F ob t h e F oubth C ircuit

No. 10,207

In the

J am es E . S w a n n , et al.,

Appellants,

—and—

T h e N orth C arolina T eachers A ssociation ,

a corporation,

Intervenor,

—v.—

T h e C hablotte-M ecklenburg B oard of E ducation ,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t f o r t h e

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHARLOTTE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

C onrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J . L evonne C ham bers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

J ack G reenberg

D errick A . B ell , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of the Case ............... 1

Questions Involved ............................................................ 3

Statement of Facts .......................................................... 4

A rgum ent

I. The District Court’s Approval of Continued

Racial Assignment of Negro Students to the

Ten Excepted Negro Schools Was a Clear

Abuse of Discretion ........................................... 11

II. The Court Below Erred in Approving Trans

fer Policies Which Preserve Racial Segrega

tion in the School System ............................... 15

C onclusion ........................................................................................ 21

T able of C ase s :

American Enka Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 119 F. 2d 60 (4th

Cir. 1941) .......................................................................16,20

Bell v. School Board of City of Gary, 324 F. 2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert. den. 377 U. S. 924 ................... 19

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963) .......................................................... 18

Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of Education,

345 F. 2d 329 (4th Cir. 1965) ....................................... 11

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, Virginia, 345

F. 2d 310, 323 (4th Cir. 1965) .............. .................... 14,17

11

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington, 324

F. 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ........................................... 15

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954)

4, 7,11,12

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955)

7,11,15,16

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir, 1964) ....................................... 11

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ............................... 11

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ....... 15,18,

19, 20

Dowell v. School Board of City of Oklahoma City

Public Schools,------F. Supp.------- , No. 9452 (W. D.

Okla., Sept. 7, 1965) .................................................... 19, 20

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336

F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964) ......................................... 19

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683 (1963) .................................................. 11,15

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218 ...................................................11,15

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730

(5th Cir. 1958) .............................................................. 15

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 620 (4th Cir. 1962) .....12,14

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d

72 (4th Cir. 1960) .......................................................... 15

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U. S. 145 .......16,18,19, 20

N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock

Co., 308 U. S. 241

PAGE

16

Ill

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 345

F. 2d 333 (4th Cir. 1965) ............................................ 12

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ...................................15,19

Price v. Denison Independent School District, ------

F. 2 d ------ , 5th Cir. No. 21,632 (July 2, 1965) ....... 13

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, ------F. 2 d ------- (5th Cir. No. 22,527, June 22,

1965) ................................................................................ 13,16

Sperry Gyroscope Co. v. N. L. R. B., 129 F. 2d 922

(2d Cir. 1942) ...............................................................16,20

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173 ........................................................................ 16,18,19,20

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (1963) ....... 11

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309

F. 2d 630 (4th Cir. 1962) ........................................ 12,14

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, ------

F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. No. 9630, June 1, 1965) ........... 12

Oth er A u t h o r it y :

General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation

of Elementary and Secondary Schools, United States

Office of Education, Department of Health, Educa

tion, and Welfare, April 1965 (H. E. W. Guide

lines) ................................................................................12,14

PAGE

In the

T&mtzb Stall's (Eourt of Appeals

F or th e F ourth C ircuit

No. 10,207

J ames E . S w a n n , et al.,

—and—

Appellants,

T h e N orth C arolina T eachers A ssociation ,

a corporation,

Intervenor,

T h e C h arlotte-M ecklenburg B oard of E ducation ,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

appeal from th e united states district court for th e

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHARLOTTE DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order (145a) of the United

States District Court for the Western District of North

Carolina, Charlotte Division, approving a plan submitted

by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education for de

segregation of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg public schools.

This action was instituted on January 12,1965, by twenty-

five Negro children and their parents, on behalf of them

selves and others similarly situated, seeking a permanent

injunction enjoining the continued use of racially gerry

2

mandered school districts, transfer policies based on race

and racial employment and assignment of teachers and

school personnel (la-8a). Answer to the complaint was

filed on February 5, 1965 (9a), the appellee Board denying

certain allegations of the complaint and alleging that it

had established geographical attendance zones for schools

to be placed in effect for the 1965-66 school year.

Appellants filed interrogatories on February 9, 1965

(15a). On February 18, 1965, the Board moved (58a) that

the time for answering same be extended until May 1, 1965.

Appellants filed objections to the request for extension on

February 23,1965 (60a). Following a hearing on the motion

on March 11, 1965, the district court extended the time for

answering the interrogatories until April 15, 1965 (62a).

The Board filed answers to the interrogatories on April

15, 1965 (20a), and attached its proposed plan for the as

signment of students for the 1965-66 and subsequent school

years (37a-47a).

On May 25, 1965, appellants moved the Court (63a) to

preliminarily enjoin the Board’s proposed racial assign

ment of Negro students to ten schools, which the Board ex

cepted from its geographical assignment plan (42a-46a).

The Board filed an answer to the motion on May 27, 1965

(65a). The district court entered a Memorandum Decision

and Order on June 1, 1965, denying appellants’ motion for

preliminary injunction (97a).

The North Carolina Teachers Association filed a motion

to intervene in the action and a complaint in intervention

on June 1, 1965 (100a-105a). The Board filed an answer

to the motion on June 8, 1965 (106a), and to the complaint

in intervention on July 15, 1965 (107a).

Appellants filed additional interrogatories on June 24,

1965 (109a), following the Board’s assignment of students

which were answered on July 8, 1965 (112a).

3

The cause came on for hearing on July 12 and 13, 1965,

at which time the lower court received stipulated facts and

testimony and heard arguments from counsel for both

parties. The district court entered a Memorandum De

cision (145a) and Judgment (155a) on July 14, 1965, find

ing that the Board’s continued racial assignment of Negro

students to the ten excepted schools was reasonable, that

there was no evidence of purposeful gerrymandering of

the attendance zones established for the other schools, and

ordering the plan modified to provide for the immediate

employment and assignment of teachers and school per

sonnel on a nonracial basis. A judgment was accordingly

entered approving the plan as modified (155a).

Notice of appeal was filed on July 15, 1965.

On August 20, 1965, appellants moved this Court for an

injunction pending appeal to enjoin the racial assignment

of Negro students to the ten excepted schools and requested

an early hearing. In an order dated August 24, 1965,

hearing on the motion was postponed until hearing on the

merits on appeal, with leave given the parties to address

themselves to the motion as well as to the merits (164a).

Questions Involved

1. Whether the Court below erred in approving a plan

providing for continued racial assignments of all Negro

students in ten of the Board’s schools, where such continued

assignments were not required by unavoidable administra

tive problems and had the effect of severely limiting the

amount of desegregation in the system.

2. Where a school board has followed a policy of com

pulsory racial assignments pursuant to dual bi-racial school

zones, may such board satisfy the requirements of Brown

4

v. Board of Education to disestablish their segregated

system by designing geographical attendance zones which

limit integration, and adopting transfer procedures which

maintain segregation in the schools.

Statement of Facts

There are approximately 75,000 students in the Char-

lotte-Mecklenburg School System, approximately 52,000

white pupils and 23,000 Negro pupils (25a-27a). During the

1964-65 school year the system had 56 all-white schools, 31

all-Negro schools; there was a small degree of racial mix

ing in the remaining 22 schools.1 For the 1965-66 school

1 Enrollment for 1964-65 and 1965-66 by schools (25a, 27a) :

E n r o l l m e n t 1964-65 E n r o l l m e n t 1965-66

S c h o o l Negro White Negro White

Alexander Jr. 0 577 7 595

Alexander Street 342 0 333 0

Ashley Park 0 654 0 656

Bain 0 674 0 712

Barringer 0 604 0 646

Berryhill 0 1026 2 1003

Bethune 343 9 355 10

Biddleville 434 0 421 0

Billingsville 729 0 721 0

Briarwood 2 582 7 623

Chantilly 0 445 3 434

Clear Creek 0 207 0 195

Cochrane Jr. 0 872 10 961

Collinswood 0 375 0 378

Cornelius 0 241 2 246

Costwold 0 631 0 620

Couhvood Jr. 3 574 33 641

Crestdale 97 0 87 0

Davidson 0 178 0 185

Marie Davis 80S 0 813 0

Derita 6 892 22 948

Devonshire 2 474 4 525

Dil worth 100 401 105 343

Double Oaks 703 0 786 0

Druid Hills 520 0 485 0

East Mecklenburg High 0 1782 4 1930

Eastover 0 704 1 650

5

year, there are 36 all-white schools, 29 all-Negro schools,

and 44 racially mixed schools.

(Continued)

E n r o l l m e n t 1964-65 E n r o l l m e n t 1965-66

S c h o o l Negro White Negro White

Eastway Jr. 0 1046 1 1121

Elizabeth 5 448 79 329

Enderly Park 0 368 0 356

Fairview 702 0 715 0

First Ward 473 0 430 0

Garinger High 2 2266 65 2249

Alexander Graham 0 1048 18 1105

J. H. Gunn 696 0 707 0

Harding High 0 1002 29 1030

Hawthorne Jr. 25 670 102 729

Hickory Grove 0 530 0 534

Highland 2 273 3 302

Hoskins 0 342 6 355

Huntersville 0 553 1 528

Huntingtowne Farms 0 358 0 390

Idlewild 0 592 0 543

Irwin Avenue Jr. 785 0 836 0

Amay James 360 0 360 1

Ada Jenkins 431 0 441 0

Lakeview 0 400 3 385

Lansdowne 0 633 0 672

Lincoln Heights 783 0 756 0

Long Creek 0 423 0 402

Matthews Jr. 0 937 1 919

McClintock Jr. 0 1273 0 1382

Merry Oaks 0 538 0 526

Midwood 0 560 0 497

Montclaire 0 720 0 644

Morgan 305 0 311 0

Myers Park Elem. 0 575 0 598

Myers Park High 31 1772 162 1693

Myers Street 820 0 747 0

Nations Ford 0 513 0 545

Newell 0 463 0 486

North Mecklenburg 1 1155 151 1137

Northwest Jr. 773 0 0 818

Oakdale 0 402 5 423

Oakhurst 0 548 0 551

Oaklawn 6 6 6 0 693 0

Park Road 0 583 0 604

Paw Creek 0 793 0 768

6

Prior to 1962, the Board made assignment of students

according to dual racial attendance zones established prior

1 (Continued)

E n r o l l m e n t 1964-65 E n r o l l m e n t 1965-66

S c h o o l Negro White Negro White

Piedmont Jr. 121 291 287 201

Pineville 0 364 0 367

Pinewood 0 719 0 704

Plato Price 505 0 509 0

Plaza Road 0 400 2 332

Quail Hollow Jr. 0 766 0 878

Rama Road 0 442 2 509

Ranson Jr. 9 658 33 727

Second Ward 1411 0 1529 1

Sedgefield Elem. 3 526 5 561

Sedgefield Jr. 6 920 43 923

Selwyn 0 531 0 533

Seversville 96 229 226 19

Shamrock Gardens 0 536 0 532

Sharon 0 591 0 568

Smith Jr. 0 1115 0 1207

South Meek. High 30 1430 122 1546

Spaugh Jr. 1 930 11 917

Starmount 0 481 0 549

Statesville Road 0 650 0 650

Steele Creek 0 222 0 220

Sterling Jr. 699 0 607 0

Thomasboro 0 885 0 926

Torrence-Lytle 1005 0 944 0

Tryon Hills 0 324 4 316

Tuckaseegee 0 631 0 598

University Park 700 0 735 0

Villa Heights 23 594 101 528

Wesley Heights 214 0 209 0

West Charlotte High 1560 0 1695 0

West Mecklenburg High 1 1270 84 1286

Williams Jr. 752 0 808 0

Wilmore 6 323 22 333

Wilson Jr. 0 1064 1 1155

Windsor Park 1 679 1 704

Winterfield 0 455 0 577

Woodland 360 0 326 0

Woodlawn 0 283 1 272

Isabella Wyche 383 0 376 0

York Road 1041 0 1127 0

Zeb Vance 465 0 525 0

7

to 1954. Teachers, principals and school personnel were

employed and assigned according to their race and color

and the race and color of the students attending the par

ticular schools (167a-169a). Extra-curricular school activ

ities were authorized and sanctioned on a racial basis. Thus

except for a few Negro students who had sought transfers

pursuant to the N. C. Pupil Enrollment Act, N. C. G. S.

§§115-176 et seq., no steps had been taken by the Board

to bring the school system in compliance with the Supreme

Court’s decisions in Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483 and 349 U. S. 294 (168a).

In 1962, the Board drew attendance zones for two schools

(174a) but provided that students in these schools could

transfer out if their race was in the minority (175a-176a).

The Board denied applications of other students who sought

to transfer to a school to obtain an integrated education

(176a-177a). During the 1963-64 school year, the Board

extended geographical assignments to twelve additional

schools (48a, 175a). The Board continued its policy of

granting racial transfers (48a, 175a-177a). In this year

the Board also assigned one white teacher to teach Bible

part-time in a Negro school. The Board extended geo

graphical assignments to 43 schools for the 1964-65 school

year (50a, 178a), continuing the same racial transfer

policy. Several of these lines were admittedly gerryman

dered (328a). In this year, also, the Board assigned 8

white teachers to all-Negro schools (178a-179a). No Negro

teacher was assigned to teach in a white or predominantly

white school. Approximately 819 Negro students were at

tending schools with approximately 17,366 white students

(25a-27a).

For the 1965-66 school year the Board proposed to ex

tend geographical attendance zones to 99 of the 109 schools

8

(37a-47a).2 The 10 “excepted” schools are all-Negro and

offer inferior education because of the low enrollments

in these schools. In addition, Negro students are required

to travel several miles, across several attendance zones

to reach these schools, even though schools near the resi

dences of these Negro students could easily absorb the

Negro students. For these schools, the Board proposed to

continue its dual attendance zones and bus routes. The

plan provides that these students may request transfer out

of these schools, but the parents were not advised that

bus transportation would be provided if they requested

transfer of their children to other schools (41a; 70a-96a).

There are approximately 4,000 Negro students assigned

to the “excepted” schools, more than one-half of whom

would be assigned to integrated schools if nonracial dis

trict lines were drawn (332a-333a).

The Board gave as reasons for excepting these schools:

the problem of space, the programs being offered at these

schools, and the building program, following completion

of which new school zone lines are to be drawn for all

schools affected (398a-399a).

Pursuant to its plan for establishing geographical at

tendance zones for the other 99 schools, the lines drawn

showed the following:

2 The plan provides (paragraph 10) (42a) :

“There exist attendance areas, serving certain schools in Mecklen

burg County, which now overlap and embrace territories which

include the attendance areas of other schools. The schools with

attendance areas which overlap other attendance areas are Sterling

School, Torrence-Lytle School and J. H. Gunn, which are known

as union schools providing instruction at the elementary, junior

high and senior high school level in grades one through twelve,

the York Koad Junior-Senior High School, the Plato Price and

Billingsville Schools which combine elementary and junior high

school courses of instruction, Crestdale Elementary School, Ada

Jenkins Elementary School, Amay James Elementary School and

Woodland Elementary School” (42a).

9

The northeast line of Lakeview Elementary School

starts on Rozze.lls Ferry Road, and, instead of con

tinuing down this road, a substantial highway, to

Stewart Creek Road, it veers off to pick up some white

students, thereby keeping them out of the all-Negro

Biddleville Elementary School (240a-242a). The Board

stated that the line followed a railroad track (328a).

The southwest line of Barringer Elementary, all-

white, veers off on an undisclosed street, rather than

going along the railroad track (245a-246a). The

Board stated that the lines here would be changed

upon completion of Allenbrook School (330a-331a).

The eastern zone of Eastover Elementary School,

all-white, starts down Randolph Road and suddenly

cuts off, for no apparent reason, and goes hack. This

removes a small white community from the Negro

Billingsville School (247a-248a; 440a-441a). The Board

stated the line followed a creek (331a-332a).

The southern line of Billingsville Elementary School

cuts across a proposed new road (249a; 333a), rather

than continuing down to McAlway Road. The present

line keeps several white students, attending Cotswold

Elementary, out of all-Negro Billingsville Elementary

School (249a-250a; 440a-441a).

The southern line of Derita Elementary, with 22

Negro students and 948 white students, comes down

across Interstate 85, a major thoroughfare, and picks

up a small white community. The effect of this line

is to keep the white children, south of Interstate

Highway 85, out of all-Negro Druid Hill (253a). The

Board stated that it contemplated redrawing the line

at Interstate Highway 85 as soon as it completed

building a junior high school in that area (333a-334a).

Alexander Graham School has a wandering line

which logically should follow Providence Road to

10

Wendover Road, both major highways. Instead, the

line branches off between Andover Road and Vernon

Drive, keeping a small settlement of white students

in Alexander Graham rather than placing them in

all-Negro Billingsville (258a).

The common line between Second Ward and Pied

mont Junior High School instead of following Trade

Street, which is a major thoroughfare, cuts off to pick

up a Negro settlement and then returns to Trade

Street. If the line followed Trade Street this would

enable more Negroes to attend Piedmont Junior High

and alleviate the overcrowded conditions at Second

Ward Junior High School (259a-260a).

The west line of Ranson Junior High School, in

stead of following Beatties Ford Road or Belhaven

Road to Oakdale and then to Sunset Road, major

streets, cuts off Beatties Ford Road for no apparent

reason. If it followed Beatties Ford Road this would

put more Negroes in Coulwood Junior High School

or Ranson Junior High School. The southern line

should cut off at Interstate 85 rather than crossing

Interstate 85 as it presently does. The present line

keeps Negroes out of Cochrane Junior High School

(261a-264a).

There are some 19 schools in the system to which

one or two students of one race were initially assigned.

No apparent reason was given for this small number

of one racial group being initially assigned to par

ticular schools (250a-251a).

The plan as proposed by the School Board provides for

free transfers of students after initial assignment (38a-

39a). The effect of this provision has been that the 396

white students initially assigned to 16 Negro schools have

11

transferred out of these schools and thus re-segregated

the 16 Negro schools (394a-396a).

Nineteen hundred and fifty-five Negro students were

initially assigned to mixed or previously all-white schools

(312a). Ninety-one of these requested transfer out and 262

Negro students requested transfers to integrated schools

leaving a balance of 2,126 of approximately 23,000 attend

ing integrated schools for the 1965-66 school year.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The District Court’ s Approval of Continued Racial

Assignment of Negro Students to the Ten Excepted

Negro Schools Was a Clear Abuse of Discretion.

A. It was more than eleven years ago when the Su

preme Court proscribed racial segregation in public edu

cation. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483. Pub

lic school authorities were then required to make a prompt

and reasonable start toward eliminating their racially dis

criminatory policies. Brown v. Board of Education, 349

U. S. 294, 300. Since that time the Supreme Court, and

this Court, have consistently reproved delays in complying

with the Brown decision. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1;

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; Goss v. Board

of Education, 373 U. S. 683; Griffin v. County School Board

of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S. 218; Buckner v.

County School Board of Greene County, 332 F. 2d 452

(4th Cir. 1964); Bowditch v. Buncombe County Board of

Education, 345 F. 2d 329 (4th Cir. 1965). Plans or pro

grams which could be approved for eliminating racial

discrimination in public schools have been sharply re

stricted. Goss v. Board of Education, supra.

12

Eleven years following the Brown decision, and despite

the decisions of the Supreme Court and of this Court, the

Court below has approved a plan which permits the con

tinued use of dual, racial school zone lines and continued

initial racial assignment of one-fifth of the system’s Negro

students to 10 of the 109 schools. This Court has expressly

enjoined the use of dual racial school zone lines. Jeffers

v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir. 1962); Wheeler v.

Durham City Board of Education, 309 F. 2d 630 (4th Cir.

1962). This Court has further rejected plans providing

for initial racial assignments. Wheeler v. Durham City

Board of Education, ------ F. 2d ------ , 4th Cir. No. 9630

(June 1, 1965); Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Educa

tion, 345 F. 2d 333, 334-335 N. 3 (4th Cir. 1965) (“ a court

ought not to put its stamp of approval upon [a plan of

desegregation] if initial assignments are both racial and

compulsory” ). Despite this Court’s rulings, however, the

court below has approved these patently discriminatory

practices.

B. Moreover, the plan here approved by the district

court falls far short of the minimum requirements of the

Department of Health, Education and Welfare for com

pliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Under the Department’s regulations, no pupil may be

“assigned, reassigned or transferred without being given

once annually at an appropriate time an adequate prior

opportunity to make an effective choice of school” .3 * 5

The district court’s ruling here, in requiring less than

the minimum standards of the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, invites the executive-judicial con

3 General Statement o£ Policies Under Title VI of the Civil Eights

Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and Secondary

Schools, HEW, Office of Education, xlpril 1965 (H. E. W. Guidelines).

13

flict which the Fifth Circuit has only recently admonished

district courts under its jurisdiction to avoid. E.g., Single-

ton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, ------

F. 2 d ------ , 5th Cir. No. 22,527 (June 22, 1965); Price v.

Denison Independent School District, ------ F. 2d ------,

5th Cir. No. 21,632 (July 2, 1965).

No justifiable basis whatever has been advanced by

the Board for excluding these 10 Negro schools from its

geographical attendance plan. The evidence clearly shows

that these students could be adequately placed in the

schools now serving their districts.

Negro students living near the Thomasboro Elementary

School are transported over long distances to the Amay

James and Plato Price Schools, although the Thomasboro

School is able to absorb the Negro students in this area

(242a-244a). Similarly, Negro students in the Newell

Elementary (246a-247a) and Berryhill Elementary (248a-

249a) area are transported, in some instances 8 or 10 miles

to all-Negro schools, even though there is space for these

students at Newell and Berryhill. The Paw Creek Elemen

tary School district, all white, is in the same area as Wood

land Elementary, all-Negro and an excepted school. These

schools are separated by Mount Holly Road with Negroes

and whites living on both sides and with space available

to accommodate the students (244a). The Billingsville

Junior High School with 200 students is unable to offer

comparable programs to other junior high schools in the

system. Yet, these students are retained in Billingsville

although they could easily be assigned to surrounding

schools (257a-259a). The only logical inference that can

be drawn here is that of the reluctance of the School

Board to assign white students to the Negro schools or

Negro students to the white schools in the area. Despite

the fact that these students, admittedly, are receiving an

14

inferior education at these schools, the Board proposes,

and the court below has approved, retaining these Negro

students in patently inferior schools for one or two more

years.

The Board contends that it affords a remedy to students

in the accepted schools by permitting them to transfer.

This Court has made it unequivocally clear that in order

for a plan to be approved it must afford an opportunity

to the students to indicate a choice prior to initial assign

ment. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,------

F. 2d ------ , 4th Cir. No. 9630 (June 1, 1965); see also

Department of Health, Education and Welfare regulations

cited above. Moreover, in order to afford an effective cor

rective “means must exist for the exercise of a choice that

is truly free and not merely pro forma” . Bradley v.

Board of Education of City of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310,

323 (4th Cir. 1965) (Concurring and dissenting Opinion of

Judges Sobeloff and B ell); Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 620

(4th Cir. 1962). Here, although, the School Board mailed

letters to parents of children who were initially assigned to

the 10 excepted schools, no notice was given to advise these

parents that transportation would be available for these

students to attend other schools (70a-96a). Practically,

all of these schools are in the county, and students are

bussed to school. I f the choice, allegedly, given these

parents is to be an effective one, transportation will have

to be provided and the parents of children in these schools

should have been so advised.

Manifestly, therefore, the denial by the district court

of the clear and expressed constitutional rights of appel

lants is at variance with the decisions of the Supreme

Court and of this Court and constitutes a clear abuse of

discretion.

15

II.

The Court Below Erred in Approving Transfer Poli

cies Which Preserve Racial Segregation in the School

System.

The Supreme Court has placed upon school boards the

affirmative duty of developing and implementing plans for

complete desegregation of their school systems. Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, 300. Plans or programs

which merely remove racial designations while retaining

racial segregation have consistently been reproved. Griffin

v. County School Board of Prince Edwards County, 377

U. S. 218; Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683;

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington, 324 F. 2d 303

(4th Cir. 1963); Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960); Northeross v. Board of Education

of City of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964); Holland

v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir.

1958); Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960). Thus,

the Eighth Circuit has stated in Dove v. Parham, supra at

259:

In summary, it is our view that the obligation of a

school district to disestablish a system of imposed

segregation, as the correcting of a constitutional viola

tion, cannot be said to have been met by a process of

applying placement standards, educational theories, or

other criteria, which produces the result of leaving the

previous racial segregation situation existing, just as

before. Such an absolute result affords no basis to

contend that the imposed segregation has been or is

being eliminated. The placement standards, educa

tional theories, or other criteria used have the effect

and application of preserving the creative status of

16

constitutional violation, then they fail to constitute a

sufficient remedy for dealing with the constitutional

wrongs.

It is equally imperative that a school plan he considered

in light of the past history of the school hoard and the cir

cumstances in which it is proposed to operate. Plans for

compliance with the Brown decision should not he con

sidered in a vacuum. Thus, where a school hoard has de

liberately followed a policy over a period of years of com

pulsory segregation of races in the public schools, of as

signing students, teachers and school personnel according

to race, of placing schools and school zone lines on the

basis of race, it does not satisfy its affirmative duty of

disestablishing this system by merely adopting a hands-

off policy. It is encumbent that the plan adopted provide

the means and actually lead to disestablishment of the il

legal system deliberately created. Cf. Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U. S. 145; United States v. Crescent Amuse

ment Co., 323 U. S. 173; N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Ship

building £ Dry Dock Co., 308 U. S. 241; American Enka

Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 119 F. 2d 60 (4th Cir. 1941); Sperry

Gyroscope Co. v. N. L. R. B., 129 F. 2d 922 (2nd Cir. 1942).

The Fifth Circuit has clearly adopted this position in

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

------ F. 2 d ------- (Xo. 22527, June 22, 1965). The court re

viewed the obligation imposed on school boards by the Su

preme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

294 and stated in conclusion:

In retrospect, the second Brown opinion clearly im

posed on public school authorities the duty to provide

an integrated school system. Judge Parker’s well-

known dictum (“ The Constitution, in other words,

does not require integration. It merely forbids dis

17

crimination.” ) in Briggs v. Elliott, E. D. S. C. 1955,

132 F. Supp. 776, 777, should be laid to rest. It is in

consistent with Brown and the later development of

decisional and statutory law in the area of civil rights.

While the issues before this court in Bradley v. School

Board of City of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965),

in which each student was given complete freedom of choice

are clearly distinguishable from the factual situation here,

the views of Judges Sobeloff and Bell expressed in that

case (Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, supra,

at 323) appear in accord with the position of the Fifth

Circuit and are both logically and practically necessary if

the mandate of Brown is ever to be translated into fact.

The Judges there stated:

It is now 1965 and high time for the court to insist

that good faith compliance requires administrators of

schools to proceed actively with their nontransferable

duty to undo the segregation which both by action

and inaction has been persistently perpetuated. How

ever phrased, this thought must permeate judicial

action in relation to the subject matter. (Emphasis

in original.)

Considered in this context, the error of the district

court, in approving the attendance areas adopted by

appellee, is clear.

Appellee, over the years, has followed a deliberate

policy of segregation of the races in its public schools.

Attendance areas were established, schools planned and

located, and children assigned to the various schools in

furtherance of appellee’s racial policy. In attempting to

carry out its affirmative duty of disestablishing its segre

gated school system, appellee does not discharge this duty

18

by now merely taking a neutral position in drawing at

tendance areas around schools deliberately located to

maintain segregation. Louisiana v. United States, supra;

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., supra. Bee

also, Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, 321 F. 2d

494, 499 (4th Cir. 1963), where counsel for the school board

questioned whether the board had violated its duty by

failing to encourage integration, the court stated: “ The

school board has indeed violated its duty. It is upon the

very shoulders of school boards that the major burden

has been placed for implementing the principles enun

ciated in the Brown decision” . Particularly is this so

where, as here, the newly established zones leave the

school system as racially segregated as before. Dove v.

Parham, supra.

The evidence here shows several instances where school

zone lines have veered off from normally established

routes resulting in the exclusion or inclusion of a par

ticular racial settlement. As shown by the testimony of

plaintiffs’ expert witness, the attendance areas of Lake-

view Elementary School, Barringer Elementary School,

Billingsville Elementary School, Eastover Elementary

School and Derita Elementary School, veer off from

reasonably acceptable routes, resulting in the exclusion

or inclusion of certain racial groups. (240a-242a, 245a-246a,

247a-248a, 440a-441a, 249a-250a, 253a.) The same is true

of the attendance areas of Alexander Graham, Second

Ward and Ransom Junior High Schools (258a, 259a-260a,

261a, 264a). The attendance area of Billingsville Elemen

tary School, all-Negro, is completely surrounded by five

entirely or predominantly white elementary schools. Even

if it is assumed that the appellee here was neutral and

followed, in drawing the attendance zones, what would

be acceptable educational criteria in another context, it

19

has failed to discharge its duty if, as here, equally ac

ceptable boundaries exist which would further the process

of disestablishing the segregated school system. Cf. Dove

v. Parham, supra; Northcross v. Board of Education of

City of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661, 664 (6th Cir. 1964);

Dowell v. School Board of City of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, ------ F. Supp. --------- , No. 9452 (W.D. Okla.,

Sept. 7, 1965).

The issue here is clearly distinguishable from that

faced by the Seventh Circuit in Bell v. School Board of

City of Gary, 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

377 U.S. 924, and the Tenth Circuit in Downs v. Board of

Education of Kansas City, 336 F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964).

Whatever may be the constitutional obligation of school

systems with racially imbalanced schools caused by

residential patterns and varied conditions not attributable

directly to school officials (see generally, Fiss, “ Racial

Imbalance in the Public Schools: The Constitutional

Concepts” , 78 Harv. L. Rev. 564 (1964)), the constitutional

duty of disestablishing, as here, carefully and deliberately

established segregated school systems is clear. Whatever

might be said of appellee’s geographical zoning of its

school district if hypothetically appraised in another

context where no history of compulsory segregation is

present, appellee’s present lines should be viewed in its

factual context against a background of school planning

and manipulation to foster segregation. Against that

background, and faced, as was appellee, with the alterna

tive of drawing attendance areas for the schools referred

to above along lines of constitutionally acceptable stan

dards so as to further disestablish its segregated

school system, its failure to follow these lines may not

be constitutionally condoned. Louisiana v. United States,

supra; United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., supra;

20

Dove v. Parham, supra; Dowell v. School Board of City

of Oklahoma City Public Schools, supra.

Equally objectionable here is the transfer system estab

lished by appellee which has resulted generally in re

segregation of the school system after initial assignment.

Here, appellee initially assigned 346 white students to

16 formerly all-Negro schools. Pursuant to appellee’s

transfer policy, 345 of these students transferred out to

all-white or predominantly white schools. Again, this

procedure must be viewed in light of appellee’s prior

practices of compulsory racial segregation and of its

practices followed since its initiation of geographical

attendance areas in 1962 of granting and encouraging

transfers of students initially assigned to integrated

schools. These standards established here by appellee

actively promote “the result of leaving the previous racial

situation existing, just as before.” Dove v. Parham, supra;

Dowell v. School Board of City of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, supra. Just as in Dowell, appellee here should

be required to adopt procedures which will further dis

establish the racial segregation of students in its public

school system. Merely taking a neutral or hands off posi

tion here does not dischharge appellee’s constitutional

duty of desegregating the public schools under its juris

diction. Louisiana v. United States, supra; United States

v. Crescent Amusement Co., supra; American Enka Corp.,

v. N.L.R.B., supra; Sperry Gyroscope Co. v. N.L.R.B.,

supra.

21

CONCLUSION

Appellants respectfully submit that for all of the fore

going reasons the decision in the court below should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

D errick A. B e l l , J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C onrad 0. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

J . L evonne C ham bers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants

MEilEN PRESS IN C — N. Y. C.