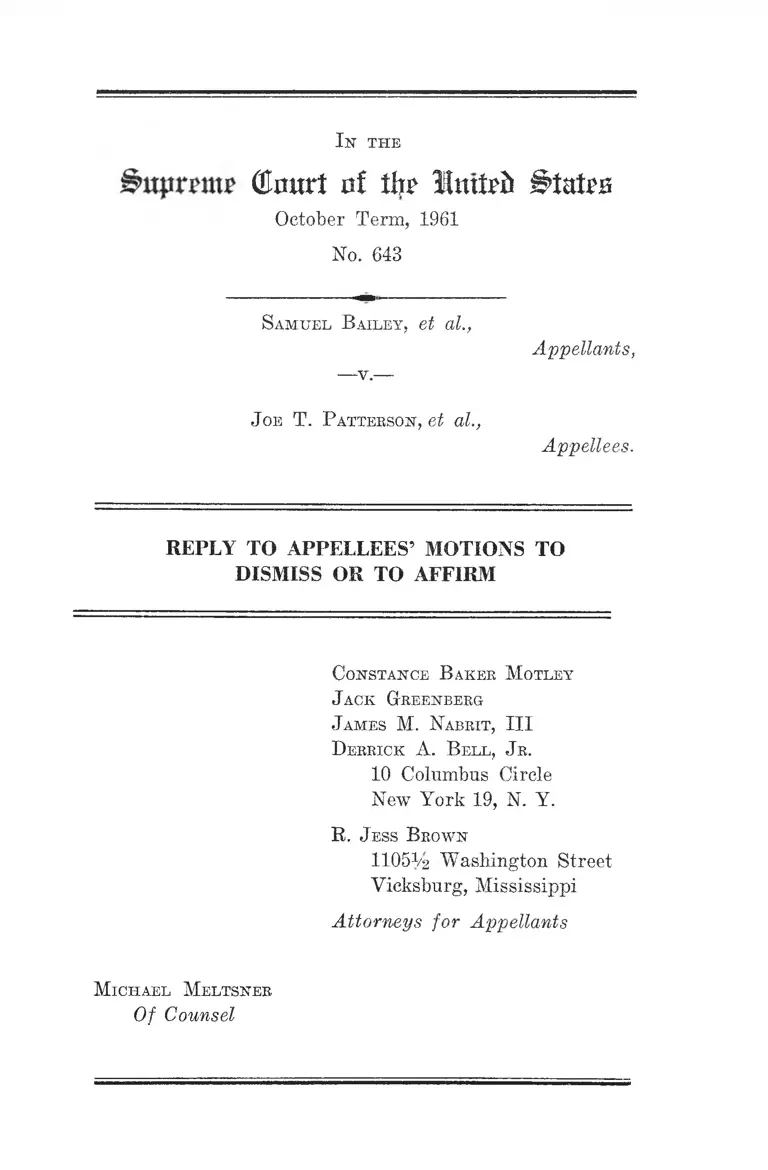

Bailey v. Patterson Reply to Appellees' Motions to Dismiss or to Affirm

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bailey v. Patterson Reply to Appellees' Motions to Dismiss or to Affirm, 1961. 1479a68b-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ce9d2bf2-e84a-44c4-ae38-aa9fb167cb95/bailey-v-patterson-reply-to-appellees-motions-to-dismiss-or-to-affirm. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

(&mvt of tht lotted BtntiB

October Term, 1961

No. 643

Samuel Bailey, et al.,

— v .—

J oe T. P atterson, et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

REPLY TO APPELLEES’ MOTIONS TO

DISMISS OR TO AFFIRM

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

R. J ess Brown

11051/2 Washington Street

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellants

Michael Meltsner

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

I. Motion to dismiss or affirm filed by the City of

Jackson, Mississippi, its Mayor, Commissioners,

Chief of Police, and by the Attorney General of

Mississippi .............................................. 1

A. Appellants’ Claims Are Justiciable ................. 1

B. The Order Below Is Appealable ..................... 10

C. The United States District Court From Which

This Appeal Was Taken Had Jurisdiction of

This Cause Under 28 U.S.C. §2281 ................. 12

II. Motion of Greyhound Corporation and Continental

Southern Lines to dismiss and/or affirm ....... . 16

Conclusion................. 18

T able oe Cases

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern Rail

way, 341 U.S. 341 .......... .......................................... 12

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958) .... 8

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (5th Cir. 1961) .... 8

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 ____ _________ 5,16

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala, 1956),

affirmed, 352 U.S. 903 ...................... .......... .......... . 5, 7

Bryan v. Austin, 148 F. Supp. 563 (E.D. S.C. 1957)

app. dism. as moot, 354 U.S. 933 ....... .................... 10

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315............................ 12

ii

PAGE

Ettelson v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 317 U.S. 188 .... 10

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202 ................................... 7,8

Ex parte Bransford, 310 U.S. 354 ............................ 15

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas Co.,

224 F. 2d 752 (5th Cir. 1955), appeal dismissed, 351

U.S. 901 ..................................................................... 5

Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207 ............................ 6, 9

Government & Civic Employees Organizing Comm.,

CIO v. Windsor, 353 U.S. 364 ................................ 10

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167 ........................... 10

Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 ...... ........... 5,16

Herkness v. Irion, 278 U.S. 92 ......... ................... ...... 14

Keys v. Carolina Coach Co., 164 M.C.C. 769 (1955) ..5,16

Lewis v. Greyhound Corp. (M.D. Ala., C.A. No. 1724-n,

November 1, 1961, not yet reported) ........................ 6

Meredith v. Fair, 30 U.S. Law W. 2347 ........... ............. 2

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80 ........................5,16

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 ........................... 5,16

NAACP v. Bennett, 360 U.S. 471 ........................... . 10

NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco By., 297 ICC 335

(1955) .............................. ........................................... 5

Poe v. Ullman, 6 L. ed. 2d 989 ................................... 8

Query v. United States, 316 U.S. 486 ........................ 14

Radio Corporation of America v. United States, 95

F. Supp. 660 (N.D. 111.), affirmed 341 U.S. 412 ...... 12

Ill

PAGE

Romero v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d 399 (C.A. 9), reversing

131 F. Supp. 818 (S.D. Cal.) ........... ........................ 11

Sterling v. Constantin, 278 U.S. 378 ............................. 16

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199........... . 6, 9

United States v. Parke, Davis & Co., 362 U.S. 29 .... 16

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629 ....... 17

Walling v. Helmerich & Payne, Inc., 323 U.S. 37 ..... 17

Statutes and Other A uthorities

28 U.S.C. §1253 ......................... .................... ..... ........ 12

28 U.S.C. §2281 .............. .......... ............... i 4

28 U.S.C. §2284 .................................................. .....12 13

17 Miss. Code Ann., §4065.3 ...... .............. ..................2, 9,15

Interstate Commerce Commission, Docket No. NC-C-

3358 (Sept. 22, 1961) ...........................

Judicial Abstention From the Exercise of Federal

Jurisdiction, 59 Col. L. Rev. 749 11

I n t h e

QJmtrt nt % States

October Term, 1961

No. 643

Samuel Bailey, et al.,

— v .—

Appellants,

J oe T. P attekson, et al.,

Appellees.

REPLY TO APPELLEES’ MOTIONS TO

DISMISS OR TO AFFIRM

Appellants have received Motions to Dismiss or Affirm,

filed by appellees, City of Jackson, Mississippi, its Mayor,

Commissioners and Chief of Police, by appellees Greyhound

Corporation and Continental Southern Lines, Inc., and by

appellee Attorney General of Mississippi. Appellants here

in reply to these Motions reserving the right to file further

replies to any other Motion to Dismiss or Affirm which may

be filed by any of the other parties hereto.*

I.

Motion to dismiss or affirm filed by the City of Jack-

son, Mississippi, its Mayor, Commissioners, Chief of

Police, and by the Attorney General of Mississippi.

A. Appellants’ Claims Are Justiciable

The essence of the motion by appellee city and its officials

consists of the position, utterly unsupported in the record,

* Time to file Motion to Dismiss or Affirm has expired.

2

that Jackson, Mississippi is not enforcing segregation in

intrastate and interstate travel or appurtenant terminal

facilities. If it were necessary, the Court could rely solely

on the notorious fact that Mississippi and all of its subdivi

sions are obedient to the precept of 17 Miss. Code Ann.

§4065.3 which exhorts “The entire executive branch of the

government of the State of Mississippi, and of its subdivi

sions, and all persons responsible thereto, including the

governor . . . mayor . . . chiefs of Police, policemen . . . to

prohibit by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional means,

the causing of a mixing or integration of the white and

Negro races in . . . public waiting rooms, . . . ” This provi

sion further incorporates by reference the massive, perva

sive “Resolution of Interposition” which purports to negate

federal prohibitions against state enforcement of racial seg

regation. Notice of the policy of the State of Mississippi in

connection with its University was recently taken by the

Fifth Circuit in Meredith v. Fair, 30 U.S. Law W. 2347-

2348:

This case was tried below and argued here in the

eerie atmosphere of never-never land. Counsel for

[University] argue that there is no state policy of

maintaining segregated institutions of higher learn

ing and that the court can take no judicial notice of this

plain fact known to everyone.

We take judicial notice that the state of Mississippi

maintains a policy of segregation in its schools and

colleges.

But this Court need not rely on judicial notice alone. The

record thoroughly substantiates appellants’ contention that

Mississippi and the City of Jackson enforce racial segrega

tion in interstate and intrastate travel facilities, in waiting

rooms, in connection with rail, bus, and air transportation,

against local residents and out of state travelers, against

3

“freedom riders” and ordinary travelers. Moreover, segre

gation is enforced in obedience to statutes of the state re

quiring segregation, and an ordinance of the city requiring

segregation, and, in apparent effort to escape federal in

terdiction, pursuant to breach of the peace laws. The en

forcement, and immediate threat inflicted by Mississippi

in all these ways leaps to the eye, not only through express

evidence inscribed in the record, but by means of the

tenacious and evasive posture of Mississippi officials and

officers of the City of Jackson who seek somehow to per

petuate segregation through taking the position that they

are not enforcing it.

At the close of the trial in the court below counsel for

Jackson City Lines, the local bus company, addressed the

Court with a plea that it enter an injunction so that Jack-

son City Lines could cease segregating under compulsion

of statutes and ordinances without subjecting itself to the

penalties of these duly enacted requirements that racial

segregation be maintained.

We are purely a local company operating only in the

City of Jackson. The same identical statute that re

quired the railroad and the bus companies to put up a

sign, in another part of the same section requires us

to do that exactly which we are doing. The city

ordinance is an exact copy of the state law, which re

quired us to do that which we are doing. I want to

make this statement now because I think that the re

sponsibility for what may happen should be shifted to

some extent from my shoulders. The Illinois Central

Railroad and both the bus lines have, according to the

testimony here—and I have every reason to believe

every word of it—ceased to make any effort to enforce

any of these statutes except to have the signs there

which they have no control of. I have the signs in

4

buses, and those drivers are instructed just as this

driver told you, because I am the man that wrote the

instructions to park the buses in the event someone

fails to operate on the basis of those signs. . . . If you

would tell me this afternoon that in your opinion those

statutes are unconstitutional, I would take the signs

out of my buses and tell my buses to operate like the

railroads and the other two bus companies.

# * #

I don’t think any injunction should issue against me,

but I need some relief because if I go pull the signs out

of the buses, I am pulling them out in the face of the

statute and an ordinance created by my own rate

making body, and I am in trouble either way I go

(R. 696-698).

Yet the City of Jackson which insists that segregation

is not being enforced, through its attorney opposed this

request of the bus company that it be enjoined from segre

gating :

I certainly would like to be heard before you act on any

such suggestion as made to the Court. On behalf of

the City of Jackson, I strenuously object to any injunc

tion issuing in this case__ (R. 697).

And the State of Mississippi through its counsel also

urged:

We too oppose any issuance of any injunction in this

case.. . . (R. 698).

The appellants in this case had protested the segregation

here enforced years ago. Yet, a local Jackson official of

another one of the carriers (Greyhound) wrote to its presi

dent that it too was coerced by state law:

5

I will say this, if the N.A.A.C.P. does start using the

waiting rooms at any Terminal in Jackson, Mississippi

there will be plenty of trouble, because the police de

partment has the backing of the City Officials and it

appears they will go all the way to keep the races

segregated in Mississippi (E. 204; Plaintiffs’ Exh.

No. 6).

And counsel for Greyhound in its Motion to Dismiss or

Affirm recently filed with this Court, stated on p. 4 that:

The testimony is without dispute that the signs were

placed over the entrance doors at the two terminal

buildings pursuant to the provisions of Chapter 258,

Laws of 1956, Mississippi Legislature, Regular Session.

Violation of these statutes requiring the posting of

these signs and the corresponding City of Jackson

ordinance carries a severe penalty.

The letter quoted above was written before such a thing

as freedom riders existed. Indeed, appellants respectfully

suggested that “freedom riders” probably never would

have come into existence if Mississippi and appellee car

riers had been obedient to long-established requirements

of federal law. See Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80

(1941); Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946); Hender

son v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 (1950); NAACP v. St.

Louis-San Francisco Ry., 297 ICC 335 (1955); Keys v.

Carolina Coach Co., 164 M.C.C. 769 (1955); Flemming v.

South Carolina Electric and Gas Co., 224 F. 2d 752 (5th

Cir. 1955), appeal dismissed, 351 U.S. 901; Browder v.

Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala. 1956), affirmed, 352

U.S. 903 (1956) ; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960).

The suggestion that this suit arises from capricious,

arbitrary activities of “freedom riders” belies the record.

6

Appellant Bailey in this case testified concerning the ar

rest of a co-worker seated next to him on a Jackson City

bus. This co-worker obviously was not and, it is not alleged

that he was, a freedom rider (R. 250). Moreover, other

arrests of local residents occurred on Jackson City buses.

They also were merely local travelers, not freedom riders

(R. 342, 347, 353). Long before anyone ever heard of

freedom riders, the witness Evers was required to be seg

regated in the local air terminal (R. 312-315). And see

all of the other testimony of arrests and prosecutions and

other intimidation by state officials in Mississippi of per

sons who with one exception, could not be characterized

as freedom riders. (Jurisdictional Statement of Appel

lants, pp. 16-18.) Beyond this, the so-called freedom riders

were obviously not guilty of any crime and were unconsti

tutionally deprived of their federal constitutional rights.

See appellants’ Exhibit Nos. 32, 33, 34 and 35 (R. 532, 536,

541-542, 544). Garner v. Louisiana, 7 L. ed. 2d 207; Thomp

son v. City of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199; Lewis v. Greyhound

Corp. (M.D. Ala., C.A. No. 1724-n, November 1, 1961, not

yet reported).

It is quite untrue, as appellees City of Jackson and its

officials urge, that:

The gist of Appellants’ action is now and has always

been an effort to stop the State Court prosecutions

of the self-styled Freedom Riders. This necessarily

resolves itself into purely factual issues as to whether

the various persons arrested were or were not guilty

of a breach of the peace which justified the arrests.

None of them was arrested under the segregation stat

utes attacked in the case (Exhibits 32, 33, 34 & 35).

(Motion of City to Dismiss or Affirm, p. 10.)

This case involves local residents and out of state travelers

too, who have long been subjected to denial of constitu-

7

tional rights on all of the common carriers, air, rail and

bus, local and interstate, in the City of Jackson and else

where in Mississippi. While other citizens of the United

States who have protested this unconstitutional deprivation

of rights are members of this class seeking the benefit of

the decree in this cause, the complaint and prayer go far

beyond the “freedom riders” who are, appellants submit,

a by-product of the Mississippi policy proclaimed in 17

Miss. Code Ann. §4065.3 and the Mississippi Statutes, ex

tracts from which occupy pages 7-11 of the appellants’

Jurisdictional Statement.

It is, therefore, frivolous to suggest, as appellees do

on page 16 of the Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, that “Ap

pellants have no standing to litigate the constitutional is

sues presented because of the non-justiciability of Appel

lants’ claims.” As this Court held in Evers v. Divyer, 358

U.S.202:

We do not believe that appellant, in order to demon

strate the existence of an “actual controversy” over

the validity of the statute here challenged, was bound

to continue to ride the Memphis buses at the risk of

arrest if he refused to seat himself in the space in

such vehicles assigned to colored passengers. A resi

dent of a municipality who cannot use transportation

facilities therein without being subjected by statute to

special disabilities necessarily has, we think, a substan

tial, immediate, and real interest in the validity of the

statute which imposes the disability. See Gayle v.

Browder, 352 US 903; 1 L ed 2d 114, 77 S Ct 145,

affirming the decision of a three-judge District Court

(Ala) reported at 142 F Supp 707.

Moreover, these statutes are not only being enforced

through the arrest and prosecution of Negroes with suffi

cient temerity to challenge segregation, but through signs

8

which direct the races to different waiting rooms, signed

“By order of Police Department” (R. 218, 259, 277). Also,

there is the posting of signs by the various carriers obedi

ent to state law. As the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit held in Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 755 (5th

Cir. 1961), “when in the execution of that public function

[a carrier] is the instrument by which state policy is to

be and is effectuated, activity which might otherwise be

termed private may become state action within the Four

teenth Amendment.” Police posting of racial signs outside

of the terminals in question is far more state action than

occurred in Baldwin v. Morgan, supra, where “the state

[did] not physically post the signs, but it [did] so just

as effectively through the instrument of the Terminal.”

287 F. 2d at 755. Indeed, in Baldwin, the Court of Appeals

found “The very act of posting and maintaining separate

facilities when done by the Terminal as commanded by

these state orders is action by the state.” 287 F. 2d at 755.

Not only terminals, but carriers as well posted signs in

Jackson.

The abstract quotations from cross-examination in the

City of Jackson’s Motion to Dismiss or Affirm which

appear on page 16 of said Motion are meaningless when

taken out of context. The obvious full meaning of the wit

ness’ testimony was that they sought to avoid the harass

ment, obloquy and hardship which experience told inev

itably would follow should they make an effort to ride in

a nonsegregated manner. The Constitution does not re

quire that one subject himself to arrest when it is known

that arrest inevitably will follow in order to file an action

in the FTnited States court to secure one’s constitutional

rights. Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U.S. 202; Baldwin v. Morgan,

251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958).

Appellees, City of Jackson, do not rely properly on this

Court’s decision in Poe v. Ullman, 6 L. ed. 2d 989, 996, for

9

in that case, as the opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter

stated, the suit was not brought by “one who [was] him

self immediately harmed or immediately threatened with

harm by the challenged action.” See Motion of City of

Jackson, p. 19. The multitudinous arrests occurring over

a long period of time in every variety of facility, the intri

cate network of statutes and the ordinance requiring segre

gation, the refusal of the Attorney General of Mississippi to

acknowledge the unconstitutionality of state segregation

laws (E. 527) and his avowal, when asked whether and

under what circumstances he would enforce these laws,

that “If conditions should arise to such a point that I

thought it was necessary to bring them into effect, yes.”

(R. 515), demonstrates that Mississippi presently continues

as it always has, to enforce segregation in every aspect of

state life, including local and interstate travel.1 The two-

step operation of prosecuting for breach of the peace,

rather than for failure to segregate per se, does not at

all vitiate the monolithic state policy declared in 17 Miss.

Code Ann. §4065.3. In fact, petitioners respectfully sub

mit, it is difficult, if not impossible, to conceive of a case

in which enforcement of a state policy at all points is more

immediate a threat to one who seeks to enjoy constitu

tional rights.

So far as “freedom riders” are concerned, the continued

daily prosecution of citizens from outside the state, who

on the detailed evidence of this record, are being convicted

in the Mississippi courts for what under Thompson v. City

of Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 and Garner v. Louisiana, 30 U.S.

L. Week 4070, is obviously not a crime, in violation of

1 Q. Have you [the Attorney General] ever made any public

announcement to the effect that these laws referred to in the

Complaint would not be enforced?

* * #

A. Certainly not (R. 527).

10

Fourteenth Amendment rights, is a daily advertisement by

Mississippi to everyone that it intends to continue enforc

ing racial segregation in travel.

The threat is real, it is immediate, and appellants have

no relief but by judicial enforcement of long established

constitutional rights.

B. The O rder Below Is Appealable

Appellants submit that in the jurisdictional statement

they adequately set forth reasons why the order below is

appealable and that appellees, City of Jackson and its

officials, have not in any wise distinguished the cases cited

(Bryan v. Austin, 148 F.Supp. 563 (E.D.S.C. 1957), app.

dism. as moot, 354 U.S. 933 (1957); Government <& Civic

Employees Organizing Comm., CIO v. Windsor, 353 U.S.

364 (1957), per curiam; NAACP v. Bennett, 360 U.S. 471

va’g automatic remand to state court for consideration in

light of Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U.S. 167), except, essen

tially, to suggest that the question of appealability “was

[not] raised or decided” in said cases (Motion to Dismiss

or Affirm, p. 9). Appellants submit, however, that this

consistent course of decision coupled with the policy of

the jurisdictional statutes involved clearly supports appeal-

ability. It is the substance of the order rather than the

terminology to which the statutes look. As this Court said

in Ettelson v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 317 U.S. 188,

191-192:

As in the Enelow case [293 U.S. 379] so here, the

result of the District Judge’s order is the postpone

ment of trial of the jury action based upon the policies;

and it may, in practical effect, terminate that action.

It is as effective in these respects as an injunction

issued by a chancellor. If the order be found to be

erroneous, it will have to be set aside and the plaintiffs

11

permitted to pursue their action to judgment. The

plaintiffs are, therefore, in the present instance, in no

different position than if a state equity court had

restrained them from proceeding in the law action.

Nor are they differently circumstanced than was the

plaintiff in the Endow case. The relief afforded by

%129 is not restricted to the terminology used. The

statute looks to the substantial effect of the order

made.2 [Emphasis added.]

Obviously the substantial effect of the order below was to

deny a temporary injunction no matter what the order

was called. Appellants’ motion for preliminary injunction

was filed June 9, 1961. The hearing was delayed three

months before a trial was held and oral arguments were

completed upon the motion. The order of November 17th

stayed proceedings for a “reasonable,” but nevertheless,

indefinite length of time. Its practical effect and therefore

its legal effect has been to deny appellants relief for the

indefinite future. The order constituted an adjudication

of the question of preliminary relief. The motion for pre

liminary injunction is no longer sub judice. Failure to take

jurisdiction of an appeal under circumstances such as these

would result in an ad hoc episodic, inconsistent treatment

of cases which are essentially alike.3 For example, if the

2 See also Romero v. Weakley, 226 F. 2d 399 (O.A. 9), reversing

131 F. Supp. 818 (S.D. Cal.). There the district court retained

jurisdiction of the case pending state court proceedings. The court

of appeals held that the action of the district court was reviewable

and said (226 F. 2d at 400) : “All the parties also are agreed that

the decision to refuse to consider the complaints are appealable.

Apart from the agreement we hold these are appealable decisions.”

In a footnote to this statement, the court added: “Alternatively,

appellant sought a writ of mandamus. Our remanding order is,

in effect, such a writ.”

3 See note, Judicial Abstention From The Exercise of Federal

Jurisdiction, 59 Colum. L. Rev. 749, 771-776, for a discussion of

the technique of disposition where the principle of equitable ab

stention is applied.

12

District Court would choose to dismiss a complaint (which

it has power to do), see, e.g., Alabama Public Service Com

mission v. Southern Railway, 341 U.S. 341; Burford v. Sun

Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315, instead of retaining jurisdiction

during state court proceedings, its order would be appeal-

able. But, appellees urge, if it “retains” jurisdiction the

order is not. Since the two methods of disposition are, in

effect the same, however, one should not produce conse

quences different from the other. The treatment suggested

by appellees would frustrate congressional intent for three-

judge courts were created to provide a swift method of

final determination of the constitutionality of state or fed

eral enactments. See 28 U.S.C. §2284(4); 28 U.S.C. §1253.

Radio Corporation of America v. United States, 95 F.Supp.

660 (N.D. 111.), affirmed, 341 U.S. 412.

C. The United States District Court F rom Which This

Appeal Was Taken Had Jurisdiction of This Cause

Under 28 U.S.C. §2281

Appellees advance the argument that this was not prop

erly a ease for a three-judge federal district court, urging

that “ [t]he gist of Appellants’ action is now and has always

been an effort to stop the State Court prosecutions of the

self-styled Freedom Eiders. This necessarily resolves i t

self into purely factual issues as to whether the various

persons arrested were or were not guilty of a breach of

the peace which justified the arrests” (Motion to Dismiss

or Affirm of City, p. 10). This, however, is clearly not the

case, and a cursory glance at the record indicates that

appellants have sought to enjoin racial segregation en

forced by officers of the State of Mississippi under au

thority of a host of segregation statutes (see Jurisdictional

Statement, pp. 6-11) and that such injunction has been

sought on the ground of the unconstitutionality of the

statutes (as well as, the record indicates, other grounds).

13

The amended complaint herein alleges:

The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked pur

suant to provisions of Title 28, United States Code,

Section 2281 and Section 2284. This is an action to

enjoin the enforcement of certain statutes of the State

of Mississippi requiring racial segregation on common

carriers, and in waiting room and rest room facilities

utilized by common carriers, and providing criminal

penalties for carriers and persons refusing to abide

by such segregation. The statutes sought to be enjoined

are Title 11, Sections 2351, 2351.5 and 2351.7, and

Title 28, §§7784, 7785, 7786, 7786-01, 7787, 7787.5,

Mississippi Code Annotated (1942), and any other

statute of the State of Mississippi requiring or per

mitting such segregation (E. 13).

# # #

The segregation complained of herein subjects plain

tiffs and members of their class to daily public incon

venience, harassment, embarrassment, and arrest, and

violates rights secured to plaintiffs and members of

their class by the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal

Constitution and Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3 (Com

merce Clause) of the Federal Constitution and by the

laws of the United States, Title 49, United States Code,

§§3(1) and 316(d) (R. 21).

The prayer of the amended complaint seeks injunctive re

lief against state officers to prevent them from enforcing

these state statutes requiring segregation on the ground of

the unconstitutionality of said statutes (R. 21).

It is impossible to see how a complaint so sweeping in

matters specifically directed against a host of transporta

tion and waiting room segregation statutes can be narrowly

14

characterized as solely “an effort to stop State Court

prosecutions of the self-styled Freedom Eiders” by the

motion to dismiss or affirm (Motion to Dismiss or Affirm,

p. 10). The complaint falls squarely within the plain lan

guage of Title 28, §2281:

An interlocutory .. . injunction restraining the enforce

ment, operation or execution of any State statute by

restraining the action of any officer of such State in the

enforcement or execution of such statute . . . , shall

not be granted by any district court or judge thereof

upon the ground of the unconstitutionality of such

statute unless the application therefor is heard and

determined by a district court of three judges. . . .

Regularly the courts have looked into the complaint to see

whether a three-judge court should be convened.

As the bill challenged the validity under the Federal

Constitution of an order of an administrative board of

the state, the district court had jurisdiction under §266,

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290, 67

L. ed. 659, 43 Sup. Ct. Rep. 353, and this court has

jurisdiction on direct appeal. Herkness v. Irion, 278

U.S. 92, 93-94.

And see Query v. United States, 316 U.S. 486, 490:

Here a substantial charge has been made that a state

statute as applied to the complainants violates the Con

stitution. Under such circumstances, we have held

that relief in the form of an injunction can be afforded

only by a three-judge court pursuant to §266. Stratton

v. St. Louis S. W. R. Co., 282 US 10, 75 L ed 135, 51

S Ct 8; Ex parte Bransford, 310 US 354, 361, 84 L ed

1249, 1253, 60 S Ct 947.

15

Ex parte Bransford, on which Appellees rely, also turns

on a construction of the complaint. In that case it was

held that:

It is necessary to distinguish between a petition for

injunction on the ground of the unconstitutionality of a

statute as applied, which requires a three-judge court,

and a petition which seeks an injunction on the ground

of the unconstitutionality of the result obtained by

the use of a statute which is not attacked as uncon

stitutional. The latter petition does not require a

three-judge court. In such a case the attack is aimed

at an allegedly erroneous administrative action. Until

the complainant in the district court attacks the con

stitutionality of the statute, the case does not require

the convening of a three-judge court, any more than

if the complaint did not seek an interlocutory injunc

tion. 310 U.S. 354, 361.

This hardly is a case, as suggested in Bransford, where

“a prerequisite such as need for relief against state offi

cers is lacking. . . . ” 310 U.S. at 361. Nor is it a case where

the three-judge court statute is inapplicable because the

action complained of is not directly attributable to the stat

ute. 310 U.S. at 361. Here there are not only a host of

segregation statutes, but a general, recently enacted legis

lative pronouncement, 17 Miss. Code Ann., §4065.3, which

stridently exhorts state officers, from the highest to the

lowest, to enforce the racial segregation policies of the

State. And, even if recourse to the record were appropriate

to ascertain whether, in view of the complaint and the

prayer, three judges were required, here is a record re

plete with examples of enforcement and obedience to an

unconstitutional set of statutes by carriers and citizens

under threat of enforcement. See Part 1A, supra. That

segregation has been enforced in other ways, pursuant to

16

ordinance and so forth, does not rob the three-judge court

of jurisdiction which reaches to questions cognizable

by one judge as well as three. Sterling v. Constantin, 278

U.S. 378.

II.

M otion o f G reyhound Corporation and C ontinental

Southern L ines to d ism iss a n d /o r affirm.

The essence of the Motion to Dismiss or Affirm by these

interstate carrier appellees is that they have not enforced

racial segregation and that they are obedient to the Inter

state Commerce Commission Order in Docket No. NC-C-

3358, dated September 22, 1961, effective November 1, 1961

(Motion to Dismiss or Affirm of Greyhound Corporation

and Continental Southern Lines, pp. 2, 5). The record,

however, contains numerous instances of segregation on

carriers being enforced by agents of the carriers subser

vient to state law and in combination with persons acting

under color of law, or individually. See Jurisdictional

Statement, pp. 16-19. The avowal by these carriers that

now, following the decisions in Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S.

373; Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 and Keys v. Caro

lina Coach Co., 64 M.C.C. 769 (1955), the aforesaid Order

of the Interstate Commerce Commission, as well as the

decisions of this Court in Mitchell v. United States, 313

U.S. 80, and Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816, they

no longer require segregation of passengers or persons

using their terminals, is hardly a ground for avoiding the

injunction which appellants seek to obtain against them

and, therefore, does not render insubstantial the issues

presented by this appeal.

This Court recently held in United States v. Parke, Davis

& Co., 362 U.S. 29, 48, that cessation of alleged activity

does not itself moot a case:

17

The courts have an obligation, once a violation . . .4

has been established, to protect the public from a con

tinuation of the harmful and unlawful activities. A

trial court’s wide discretion in fashioning remedies is

not to be exercised to deny relief altogether by lightly

inferring an abandonment of the unlawful activities

from a cessation which seems timed to anticipate suit.

See United States v. Oregon State Medical Soc., 343

U.S. 326, 333, 96 L. ed. 978, 72 S. Ct, 690.

This long has been the law. See Walling v. Helmerich S

Payne, Inc., 323 U.S. 37 where following suit to enjoin

violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act the employer

voluntarily discontinued use of contracts which were the

subject of the suit. The cause was held to be justiciable.

Similarly, in United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629,

where there was a disclaimer of intention to repeat prac

tices against which an injunction was sought the case was

held not moot. Of course, as suggested in the W. T. Grant

case, “ [t]he case may nevertheless be moot if defendant

can demonstrate that ‘there is no reasonable expectation

that the wrong will be repeated.’ ” But, as stated there,

“the burden is a heavy one.” 345 U.S. 629, 633.

It might theoretically be established on some other rec

ord that these interstate carriers and their drivers and the

managers of their terminals will not, in the future, direct

Negroes and whites to separate parts of vehicles and ter

minals. But, a history over a period of years of repeated

violations in the face of clear federal law does not instill

confidence that at this juncture these appellees have be

come obedient to the Constitution and the Interstate Com

merce Act. If they have, an injunction can do them no

4 The excised language refers to the antitrust laws, but, of course,

is generally applicable.

18

harm. If they have not, appellants obviously need pro

tection of the decree they have prayed for.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, the appellants

respectfully submit that this Court has jurisdiction in the

instant case.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance Baker Motley

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

R. J ess Brown

1105Y2 Washington Street

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Attorneys for Appellants

Michael Meltsner

Of Counsel