Maxwell v. Bishop Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Bishop Brief Amicus Curiae, 1969. dd290257-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cee28781-b6c3-433b-b53b-935cd6e70526/maxwell-v-bishop-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

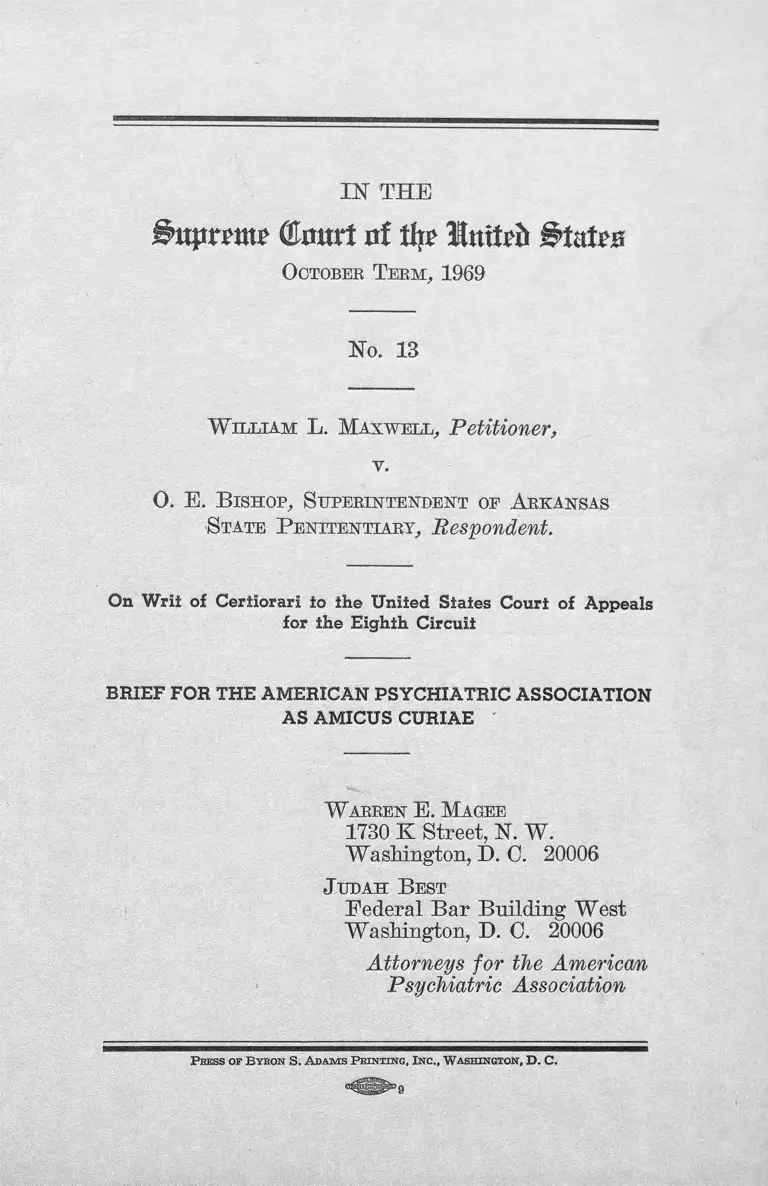

IJST TH E

GJmtrt nf % Unttefo States

October Term, 1969

Ho. 13

W illiam L. Maxwell,, Petitioner,

v.

O. E. B ishop, Superintendent of A rkansas

State P enitentiary, Respondent.

On Writ ol Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION

AS AMICUS CURIAE

W arren E. Magee

1730 K Street, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

J udah B est

Federal Bar Building West

Washington, D. 0. 20006

Attorneys for the American

Psychiatric Association

P ress op B yron S. A d a m s P rinting, Inc., W ashington, D . C .

INDEX

Page

Interest of tlie Amicus Curiae..................................... 1

Argument ............................................. 3

Conclusion ................................................................... 11

AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Bloom v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 194 (1968) ......................... 4

Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958) ............ 9

Nobles v. Georgia, 168 U.S. 398 (1897) ..................... 9

Phyle v. Duffy, 334 U,S. 431 (1948) ............................ 9

Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950) ........................ 9

Other A u th o ritie s :

Bluestone & McGahee, “ Reaction to Extreme Stress:

Impending Death by Execution,” 119 Am.J. of

Psychiatry 393 (Nov. 1962) ................................... 8

Canada, Joint Committee of the Senate & House of

Commons on Capital Punishment, Report (1956).. 7

Cohen, “ Psychiatrists Look at Capital Punishment” ,

29 Psychiatric Digest 45 (1968) .......................... 5

Coke, Third Institutes (1644) ..................................... 9

Hart, “ Punishment and Responsibility” (1968) ....... 5,7

New York State, Temporary Commission on Revision

of the Penal Law and Criminal Code, Special Re

port on Capital Punishment (1965) ................... 5

New York Times, Oct. 12, 1969 ................................... 10

Pennsylvania Joint Legislative Committee on Capital

Punishment, Report (1961) ................................. 5

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Ad

ministration of Justice, Report (The Challenge of

Crime in a Free Society) (1967) ......................... 5

11 Index Continued

Page

Eeik, “ Freud’s View on Capital Punisliment,” Tlie

Compulsion To Confess (1959) ......................... 4

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment 1949-1953,

Report (H.M.S.O. 1953) ....................................... 5

Transcript of Record, Rosenberg v. United States, Nos.

I l l and 112 (Oct. Term 1952) .............................. 11

United Nations Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Capital Punishment (ST/SOA/SD/9-10)

(1968) ................................................................... 5

Washington Post, Nov. 4, 1969 ................................... 10

Weihofen, “ The Urge To Punish.” (1956) .................. 5

West, Dr. Louis J., “ A Psychiatrist Looks at the Death

Penalty” , Paper presented at the 122nd annual

meeting of the American Psychiatric Association,

May 11, 1966 ....................................................... 6,7,8

IK THE

j&upratw ©mart nf tty? Btutzz

October Term, 1969

Ko. 13

W illiam L. Maxwell, Petitioner,

V.

O. E. B ishop, Superintendent of A rkansas

S tate P enitentiary, Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Eighth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION

AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE

The American Psychiatric Association is a nonprofit

organization incorporated in the District of Columbia

with a present membership of over 17,000 psychiatrists

located throughout the United States. Pounded in

2

Philadelphia in 1844 as the Association of Medical

Superintendents of American Institutions for the In

sane, the Association is the oldest continuing national

medical society in the United States. In 1921 the

present name of the organization was adopted, and

in 1927 the Association was incorporated in the "Dis

trict of Columbia.

The American Psychiatric Association is a society

of medical specialists brought together by a com

mon interest in the continuing study of psychiatry,

in working together for more effective application

of psychiatric knowledge to combat the metal illnesses,

and in promoting mental health of all citizens. Among

the Association’s earliest accomplishments was its par

ticipation in the transfer of the mentally ill from

jails and almshouses to medical institutions, and in

the inauguration of a program of moral treatment

that embodied the rudiments of modern community

psychiatry. In the Association’s constitution its ob

jectives are stated as follows:

To further the study of the nature, treatment,

and prevention of mental disorders and to pro

mote mental health.

To promote the care of the mentally ill.

To further the interests, the maintenance, and

the advancement of standards of all hospitals for

mental disorders, of out-patient services, and of

all other agencies concerned with the medical,

social, and legal aspects of these disorders.

To make available psychiatric knowledge to

other branches of medicine, to other sciences, and

to the public.

In furtherance of the purposes of the Association,

its governing Board of Trustees adopted a resolution

3

at its December 12, 1969, meeting condemning capital

punishment and authorizing the filing of this brief

amicus curiae. The resolution of the Board of Trustees

is set out below:

RESOLUTION

Resolved, that the American Psychiatric Asso

ciation, through its Board of Trustees, opposes

the death penalty and calls for its abolition. The

best available scientific and expert opinion holds

it to be anachronistic, brutalizing, ineffective and

contrary to progress in penology and forensic

psychiatry.

This brief is filed amicus curiae for the Association

in order to bring before this Court some psychiatric

views of capital punishment which have not hereto

fore been stressed in this case. Consent of the parties

for the filing of the amicus curiae brief has been

sought and obtained. Copies of the parties’ letters

will be submitted to the Clerk with this brief.

ARGUMENT

This brief amicus is prompted by the submission of

respondent herein:

“ 1. What the case really involves is whether

the jury system is a workable procedure in capital

cases. Petitioner contends that he would have

no complaint to a jury ’s deciding the question

of life or death if framed by adequate rules. But

it is earnestly submitted by respondent that

a set of rules could never be drafted which would

both protect the rights of the accused and the

interest of the State.” 1

1 Brief for Respondent, p. 3.

4

In other words, respondent concedes that the death

penalty, jury trials, and fairness to the parties can

not co-exist. Since trial by jury is Constitutionally

mandated, Bloom v. Illinois, 391 IJ.S. 194 (1968), the

question on respondent’s own premises is whether

the retention of the death penalty is of such im

portance to society that a system which does not “ both

protect the rights of the accused and the interest of

the State” may Constitutionally be retained. Assum

ing, without conceding, that fundamental unfairness

in a criminal case can ever be excused by such

an argument of necessity, we here demonstrate that

far from being essential to the welfare of society, the

death penalty is in fact detrimental and thus cannot

excuse a procedure which is fundamentally unfair.

It is, therefore, unnecessary for us to discuss the

broader Constitutional question of whether the reten

tion of the death penalty itself violates the Fifth or

Eighth Amendments.

We deem of special relevance to this presentation

Sigmund Freud’s views on capital punishment:

[Pjunishment not infrequently offers, to those

who execute it and who represent the community,

the opportunity to commit, on their part, the

same crime or evil deed under the justification of

exacting penance. Only the fact that mankind

shrinks from facing facts, from acknowledging

the facts of unconscious emotional life, delays the

victory of the concept of capital punishment

as murder sanctioned by law.2 3

The irrationality of the imposition of capital punish

ment has special concern for psychiatrists, for the

2Reik, “ Freud’s View on Capital Punishment” , The Compulsion

to Confess 473 (1959).

5

recurrent preoccupation with death by all human

beings is a fact of special psychiatric importance and

thereby places psychiatrists in a unique position to

evaluate the death penalty.3

It is the position of amicus that imposition of the

death penalty is so costly to society, to the adminis

tration of a system of criminal justice, and to the

sentenced individual as to require that this sanction

be abolished. All of the serious studies of deterrence

have concluded that there is no evidence that the

death penalty has deterrent efficacy.4 5 Indeed, as has

been pointed out,6 far from serving as a deterrent,

capital punishment may actually serve as an incite

ment to crime among various types of mentally un

stable potential offenders:

(1) The suicidal group, which includes depressed

patients who adopt the attitude that death is the only

3 See Cohen, “ Psychiatrists Look at Capital Punishment” , 29

Psychiatric Digest 45 (1968).

4 “ It is generally agreed between the retentionists and abolition

ists, whatever their opinions about the value of comparative studies

of deterrence, that the data which now exists show no correlation

between the existence of capital punishment and lower rates of

capital crime.” United Nations Department of Economic and

Social Affairs, Capital Punishment (ST/SOA/SD/9-10) (1968)

123. See also, Royal Commission on Capital Punishment 1949-1953,

Report (H.M.S.O. 1953) 18-24, 58-59, 328-380; President’s Com

mission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, Report

(The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society) (1967) 143; New

York State, Temporary Commission on Revision of the Penal Law

and Criminal Code, Special Report on Capital Punishment (1965)

2; Pennsylvania Joint Legislative Committee on Capital Punish

ment, Report (1961) 9, 20-29.

5E.g., Hart, “ Punishment and Responsibility” , 86-88 (1968);

Weihofen, “ The Urge to Punish” 161 (1956).

6

just punishment for their imagined sins and com

mission of capital offenses is a means of securing it.

(2) Those to whom the lure of danger has a strong

appeal. The prospect of being caught and being

sentenced to death serves as an actual incentive to

crimes of violence.

(3) The exhibitionist who is fascinated with the

idea of pitting his wits against the police and there

after being the central figure at a spectacular murder

trial.

In his paper “ A Psychiatrist Looks at the Death

Penalty” presented at the 122nd annual meeting of

the American Psychiatric Association on May 11,1966,

Dr. Louis J. West elaborated upon the thesis that the

death penalty breeds murder in that it becomes

“ a promise, a contract, a covenant between the society

and certain warped mentalities who are moved to

kill” (Id. at 3), by a series of case illustrations:

“ Recently an Oklahoma truck driver was stop

ping for lunch in a Texas roadside cafe. A total

stranger—a farmer from nearby—walked in the

door and blew him in half with a shotgun. When

the police finally disarmed the man and asked

why he had done it, he replied, ‘ I was just tired

of living.’

“ In 1964 Howard Otis Lowery, a life-term con

vict in an Oklahoma prison, formally requested

a judge to send him to the electric chair after a

District Court jury found him sane following

a prison escape and a spree of violence. He said

that if he could not get the death penalty from

that jury he would get it from another, and com

plained that officials had failed to live up to an

agreement to give him death in the electric chair

7

when he pleaded guilty to a previous murder

charge in 1961.

“ Another murderer, James French, asked for

the death penalty after he wantonly killed a motor

ist who gave him a ride while hitchhiking through

Oklahoma in 1958. However, he was ‘betrayed’

by his Court-appointed attorney who pleaded him

guilty and got him a life sentence instead of the re

quested execution. Three years later French

strangled his cellmate for no obvious reason: a

deliberate, premeditated slaying. He has been

convicted three times for that crime, declared

legally sane and sentenced to death each time.

'This sentence he deliberately invites in well-or

ganized, literate epistles to the Courts and in pro

vocative challenges to the jurors. During a psy

chiatric examination in 1965 French admitted to

me that he had seriously attempted suicide several

times in the past but ‘ chickened out’ at the

last minute, and that a basic motive in his mur

dering another prisoner was to force the State to

deliver the electrocution to which he feels entitled

and which he deeply desires.” 6

Thus, while there may be isolated and anecdotal

reports of persons who have been dissuaded from

committing capital crimes by fear of the death penalty,

the worth of such fragile evidence7 as support for

continuation of capital punishment is, in our opinion,

clearly overcome by the documented findings of in

stances where the death penalty encourages capital

crime.8 Moreover, there is substantial evidence that

6 West, supra, at pp. 3-4.

7 Generally, such evidence is unsustained by objective evidence.

See, e.g., Canada, Joint Committee of the Senate and House of

Commons on Capital Punishment, Report (1956), paras. 29-33,

43-52.

8 See particularly Hart, supra, n. 5, at p. 88.

8

the death penalty creates a breeding ground for psy

chosis in death row. Very often prisoners deteriorate

rapidly following the imposition of the death penalty.

In their study of eighteen men and one woman await

ing death in the Sing Sing death house, Drs. Harvey

Bluestone and Carl L. McGahee9 noted in virtually

every case studied the presence of degenerative psy

chological effects, including delusion, persecution, and

withdrawal as the human mind attempted, in the en

vironment of death row, to set up defenses against in

tense anxiety or the paralyzing depression occasioned

by thought of the inevitable and impending end. Dr.

West examined Jack Ruby, the convicted killer of Lee

Harvey Oswald, a number of times and noted that by

every objective medical criterion Ruby had become

grossly psychotic since he had been sentenced to death.10

The stress on Jack Ruby in the relatively short period

of time between his sentence and death was rather

less than that experienced by many condemned indi

viduals who over the course of several years approach

scheduled death down to the last month, or week, or

minute, only to live through a breathtaking re

prieve or perhaps face another countdown.

A good many of these doomed men require psy

chiatric care prior to execution, but the requirements

of legalized death dictate that when the psychiatrist

has improved his patient’s condition, he must spe

cify him as ready for execution. This phenomenon,

9 Bluestone and McGahee, “ Reaction to Extreme Stress: Im

pending Death by Execution,” 119 Am.J. of Psychiatry 393 (Nov.

1962).

10 West, supra,, at p. 5.

9

that only a sane man can be lawfully executed, has

historic roots in the “ unbroken command of Eng

lish law for centuries preceding the separation of

the Colonies” (Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9, 20

(1950) (dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurt-

ter)). At its earliest stages of development, the com

mon law prohibited execution of the insane, “ because

by intendment of law the execution of the offender is

for example, ut poena ad paucos, meins ad omnes

perveniat, as before is said: but so it is not when a

mad man is executed, but should be a miserable spec

tacle, both against law, and of extreame inhumanity

and cruelty, and can be no example to others.”

(Coke, Third Institutes 6 (1644)). That this phe

nomenon of the mind breaking down under the stress

of an impending execution is a commonplace of

the death penalty is reflected by the several eases

which have presented to this Court the problem of

insanity supervening after sentence of death,11 and

by the fact that virtually every state has provided

some mechanism for suspension of execution of the

death penalty upon insanity supervening after sen

tencing.12 * *

In addition to the cost of administering capital

cases from trial through final appeal and during the

long periods of detention that invariably follow im

u E.g., Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549 (1958); Solesbee

v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950); Phyle v. Duffy, 334 U.S. 431 (1948);

Nobles v. Georgia, 168 U.S. 398 (1897).

12 See Mr. Justice Frankfurter ’s dissenting opinion and ap

pendix of pertinent state legislation and judicial decisions, Soles

bee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. at 14 et seq.

10

position,18 there would appear to be a greater psychic

strain upon the participants in a capital case than in

a criminal matter involving lesser sanctions. There

are a number of examples of capital cases where the

persons who comprised the criminal jury publicly

reflect upon and attempt to repudiate their prior deter

mination. Thus, in the case at bar, eleven of the twelve

jurors have publicly declared that “ upon reflection,

they thought his [petitioner’s] sentence should be

reduced to life imprisonment.” 14 Indeed, in the pres

ent case the enormity of involvement in capital punish

ment has motivated the complaining witness as well

as the prosecuting attorney to disavow an interest in

having petitioner executed.15 We submit, in short,

that the harm caused by the necessity of processing a

18 See, for example, a recent newspaper account:

“ Billie Austin Bryant was sentenced yesterday to imprison

ment for life in a maximum security federal penitentiary

without possibility of parole for the murder of two FBI agents

last January. * * * In deciding against the death penalty,

Judge G-esell [of the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia] said, he was not moved by any ‘ religious,

philosophical, ethical, scientific or political controversy or

criticism’ on capital punishment. ‘ Purely practical matters

controlled the court’s decision in this case.’

Imposition of the death penalty, the judge said, would keep

Bryant ‘ indefinitely in the death cell of our antiquated jail,’

where he cannot be controlled, while appealing the death

sentence.

‘ The Court has concluded that it would not serve the ends

of effective justice to allow the defendant the luxury of all

the special attention a capital penalty would generate. ’ * * * > ’

Washington Post, Nov. 4, 1969, §*A, at 3, col. 5-6.

14 N.Y. Times, Oct. 12, 1969, § 6 (Magazine) at 60.

15 Id.

11

capital punishment case to its terrible conclusion16 is

so costly as to warrant the conclusion that capital

punishment is unnecessary to the progress of our

society and should not be permitted in the case at bar.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amicus submits that the

judgment of the Court of Appeals should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

W arren E . M agee

1730 K Street, N. W.

Washington, 1). C. 20006

J u d a h B est

Federal Bar Building West

Washington, D. C. 20006

Attorneys for the American

Psychiatric Association

16 See the following declamation of a sentencing judge: “ What

I am about to say is not easy for me. I have deliberated for hours,

days and nights. I have carefully weighed the evidence. Every

nerve, every fiber of my body has been taxed. I am just

as human as are the people who have given me the power

to impose sentence. I am convinced beyond any doubt of your

guilt. I have searched the records—I have searched my conscience

—to find some reason for mercy— for it is only human to be merciful

and it is natural to try to spare lives. I am convinced, however,

that I would violate the solemn and sacred trust that the people of

this land have placed in my hands were I to show leniency to the

defendants Rosenberg. ” (Transcript of Record, p. 1616, Rosenberg

v. United States, Nos. I l l and 112, Oct. Term 1952).