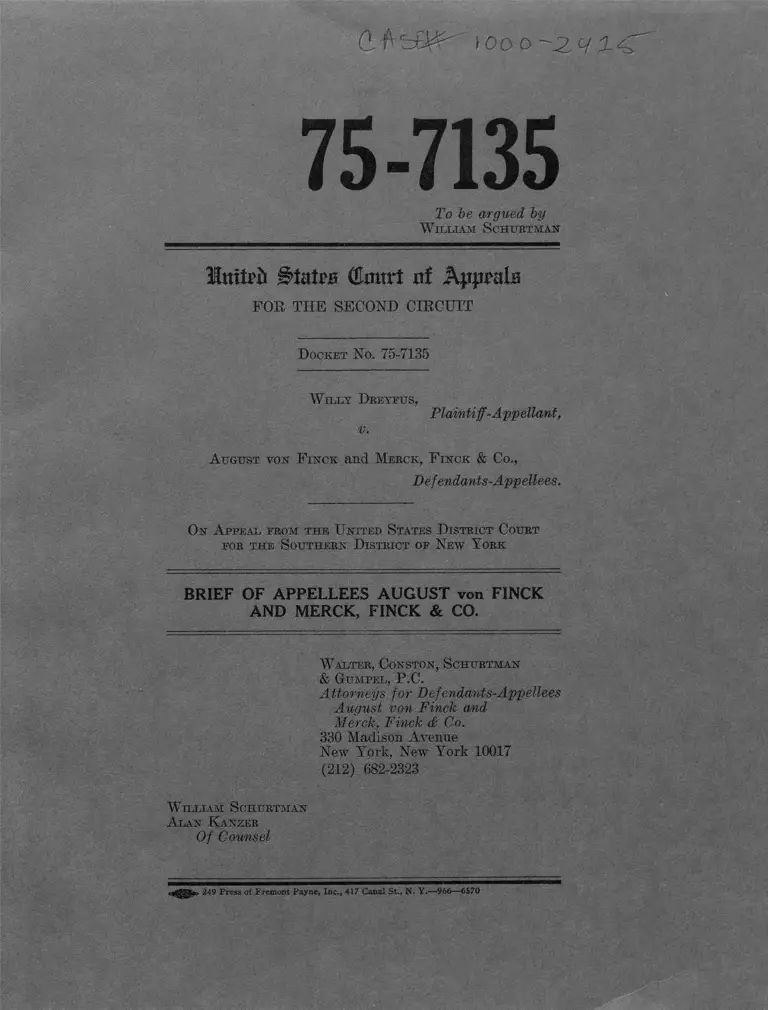

Dreyfus v. von Finck Brief of Appellees August Von Finck and Merck, Finck & Co.

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dreyfus v. von Finck Brief of Appellees August Von Finck and Merck, Finck & Co., 1975. 2a721b3d-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cefc8120-47e5-4c30-a7df-495b588355d9/dreyfus-v-von-finck-brief-of-appellees-august-von-finck-and-merck-finck-co. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

(1 f c:± ^ . i O O O -X y % <

75-7135

To be argued by

W illiam Schurtman

Hmttfk (Bfmrt nt Appeals

FOR TH E SECOND CIRCUIT

D ocket No. 75-7135

W illy Dreyfus,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

A ugust von F inck and Merck, F inck & Co.,

Defendants-Appellees.

O n A ppeal prom the U nited States D istrict Court

for the Southern District of New Y ork

BRIEF OF APPELLEES AUGUST von FINCK

AND MERCK, FINCK & CO.

W alter, C-onston, S churtman

& Gumpel, P.C.

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellees

August von Finch and

Merck, Finch & Co.

330 Madison Avenue

New York. New York 10017

(212) 682-2323

W illiam S churtman

Alan K anzer

Of Counsel

249 Press of Fremont Payne, Inc., 417 Canal St., N . Y.-—966— 6570

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Cases and Other Authorities........................ iv-x

Preliminary Statement........................................ 1

Statement of the Issues...................................... 2

Statement of the Case........................................ 3

The amended complaint................................... 3

The commencement of this action......................... 4

Defendants' motion to dismiss the original complaint... 4

The amended complaint................................... 7

The dismissal of the amended complaint.................. 7

Plaintiff's expansion of the issues on this appeal.... 8

Argument............................... 9

POINT I -

The district court correctly held that plaintiff has

failed to state a claim under any treaty of the United

States................................ 9

The decision of the district court.... ................ 9

The treaties relied on by plaintiff................... 10

A. The Hague Convention.............................. 10

B. The Kellogg-Briand Pact........................... 13

C. The Treaty of Versailles.......................... 13

D. The Four Power Occupation Agreement............... 14

Plaintiff does not have the right to sue defendants

under the Hague Convention, the Kellogg-Briand Pact,

the Treaty of Versailles or the Four Power Occupation

Agreement......................... 15

i

Page

POINT II -

The district court correctly held that plaintiff has

failed to state a claim under the law of nations...... 25

The law of nations..................................... 26

POINT III -

Plaintiff's claims are barred by the Act of State

doctrine............................................... 31

The meaning of the Act of State doctrine.............. 31

A. The Bernstein cases.............................. 32

B. First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba 33

C. The Sabbatino decision........................... 34

Conclusion......................... 36

POINT IV -

The district court lacked subject matter jurisdiction

over plaintiff's claim................................. 37

The district court's decision.......................... 37

Bell v. Hood........................................... 38

The treaties on which plaintiff relies................. 39

Plaintiff's claim...................................... 40

POINT V -

Military Government Law No. 59 is not a "law of the

United States", and no federal question arises under

it. Moreover, plaintiff has not stated any claim for

relief based on that military law...................... 42

ii

Page

The history of MGL 59.................................. ^2

MGL 59 is not a law of the United States.............. 45

A. The legislative history of §1331................... ^5

B. Judicial construction of "laws of the United

States"........................................... ^7

C. Military occupation cases......................... 50

Plaintiff's claim does not arise under a law of the

United States.......................................... 53

POINT VI -

The federal courts lack pendent jurisdiction to con

sider plaintiff's common law claims.................... 56

Conclusion.................................................. 60

iii

TABLE OP CASES AND OTHER AUTHORITIES

Page

CASES

Acheson v. Wohlmuth, 196 F.2d 866 (D.C. Cir. 1952).............. 50, 51

Adra v. Clift, 195 P. Supp. 857 (D. Md. 19 6 1)................... 26, 29

American Society and Trust Co. v. Commisioners of the District

of Columbia, 224 U.S. ¥91 TT912)............................ 50

Antoine v. Washington, 95 S. Ct. 944 (1975)..................... 18, 20, 21

Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U.S. 332 (1924).......................... 22, 23

Association J. Dreyfus &_ Co. v. Merck, Finck &_ Co., Case No. 49,

Court of Restitution Appeals, March 7, 1951................ 5, 8, 54

Bacon v. Rives, 106 U.S. 99 (1882)............. ................. 37

Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964)........ 34, 35, 36

Bell V. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946)................................ 37, 38

Bernstein v. N.V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-

Maatschappi,]', 210 F.2d 375 (2nd Cir. 1954)................. 32, 33

Bernstein v. Van Heyghen Freres Societe Anonyme, 163 F.2d 246

(2nd Cir. 19^7)7 cert, denied, 332 U.S. 771 (1947)......... 32, 33

Blanton v. State University of New York, 489 F.2d 377 (2nd Cir.

1973)........................................................ 38

Braden v. University of Pittsburgh, 3^3 F. Supp. 836 (W.D. Pa.

1972)......... 48

City of New York v^ Richardson, 473 F.2d 923 (2nd Cir. 1973).... 57

Cobb yu United States, 191 F.2d 604 (9th Cir. 1951)............. 50

Corbett v. Stergios, 381 U.S. 124 (1965)........................ 21

Crabb v. Wedden Bros., 164 F.2d 797 (8th Cir. 1947)............. 49

iv

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970)...................... 30

Dassignienis v. Cosinos Carriers & Trading Corp., 321 F. Supp.

1253 (S.D.N.Y. 1970)........................................ 37

DeCoteau v. District County Court, 95 S.Ct. 1082 (1975)......... 18, 20

Dodge v. Nakai, 298 F. Supp. 17 (D. Ariz. 1968)....... 19, 20

Edye v. Robertson, 112 U.S. 580 (1884)........................... 16, 17

Eisner v. United States, 117 F. Supp. 197 (Ct. Cl. 1954)....... . 50

Farmer v. Philadelphia Electric Company, 329 F.2d 3 (3rd Cir.

19FT)....................................................... 47

First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba, 406 U.S. 759

(1972)...................................................... 33, 34

Flick v. Johnson, 174 F.2d 983 (D.C. Cir. 1949)........... 42, 50, 51

52, 53

Gem Corrugated Box Corp. v. National Kraft Container Corp., 427

F.2d 499 (2nd Cir. 1970)....... 57, 58

Gully v. First National Bank, 299 U.S. 109 (1936)............... 54, 55

Hagans v. La vine, 415 U.S. 528 (1974)............................ 57, 58, 59

Harris v. Boreham, 233 F.2d 110 (3rd Cir. 1956)................. 50

Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 U.S. 483 (1880)........................ 21, 22

Hidalgo County Water Control and Improvement District v.

Hedrick, 226 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1955)........................ 23, 38

Illinois v. City of Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91 (1972)............... 49

Ivy Broadcasting Co. v^ American Tel. &_ Tel. Co., 391 F.2d 486

(2nd Cir. 19^8")............................................. 49

Karakatsanis v. Conquistador Cia. Nav. S.A., 297 F. Supp. 723

(S.D.N.Y. 1965)....... ...................................... 37

Page

v

Page

Khedivial Line, S.A.E. v. Seafarers' International Union, 278

F. 2d T49~T2nd Cir. I960)....................................... 28

Klein v. Shields & Co., 970 F.2d 1394 (2nd Cir. 1972)........... 57

Kolovrat v. Oregon, 366 U.S. 187 (1961).......................... 21

Leech Lake Band of Chippewa Indians v. Herbst, 334 F. Supp. 1001

(D. Minn. 1971)............................ 19

Lopes v. Reederei Richard Schroeder, 225 F. Supp. 292 (E.D. Pa.

1953)..................................................................................................... 29> 30

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co. v. Mottley, 211 U.S. 149

(I90F)......................................................................................... ................. 38

McClanahan v. State Tax Commission of Arizona, 411 U.S. 164

(1973)77.77777.“ ' . ................ .77 ........................................................ 18, 20, 21

McDaniel v. Brown & Root, 172 F.2d 466 (10th Cir. 1949)......... 48

Makah Indian Tribe v. McCauly, 39 F. Supp. 75 (W.D. Wash. 1941).. 19

Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, 14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 304 (1816)........ 21

Mater v. Holley, 200 F.2d 123 (5th Cir. 1952)................... 49

Maximov v. United States, 373 U.S. 49 (1963).................... 23

Moore v. Sunbeam Corp., 459 F.2d 8ll (7th Cir. 1972)............ 54

Murphy v. Colonial Federal Savings and Loan Ass'n., 388 F.2d 609

(2nd Cir. 1967)..... ....................................... 47

Oneida Indian Nation v. County of Oneida, 4l4 U.S. 66l (1974).... 18, 19

Patton v. Administration of Civil Aeronautics, 217 F.2d 395 (9th

Cir. 1954)......... 48

Pauling v. McElroy, 164 F. Supp. 390 (D.D.C. 1958), aff'd, 278

F.2d 252 (i960), cert, denied, 364 U.S. 835 (i960)........... 17

People of Puerto Rico v. Hermanos, 309 U.S. 543 (1940)............ 50

vi

People of Puerto Rico v. Shell Co., 302 U.S. 253 (1937)......... 50

People of Saipan v. United States Department of Interior, 356

P. Supp. 645 (D. Haw. 1973).................................18

Phelps v. Hanson, 163 F.2d 973 (9th Cir. 1947)...... ............. 18

Romero v. International Terminal Operating Co., 358 U.S. 354

(1959)............. ^5, 46

Ryan v. J. Walter Thompson Co., 453 F.2d 444 (2nd Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 4o6 U.S. 907 (1972)........................... 57, 58

Schulthis v. McDougal, 225 U.S. 561 (1912)...................... 54, 55

Skokomish Indian Tribe v. France, 269 F.2d 555 (9th Cir. 1959)••• 18, 19

Stevens v. Carey, 483 F.2d 188 (7th Cir. 1973).................. 48

Stokes v. Adair, 265 F.2d 662 (4th Cir. 1959)................... 49

Underhill v. Hernandez, 168 U.S. 250 (1897)..................... 31, 32

United Mine Workers of America v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966)..... 56, 57, 58, 59

United Optical Workers Union v. Sterling Optical Co., Inc., 500

F. 2d 220 (2nd C i r . T O T ) .................................... 38

Valanga v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 259 F. Supp. 324 (E.D.

Pa. 1966)......... 29, 30

Z&F Assets Realization Corp. v. Hull, 114 F.2d 464 (D.C. Cir.

1940), afrtd, 311 U.S. T 7 FTT941)......................... 17

Page

Constitutions

United States Constitution, article III, section 2.............. 46, 47, 49

Treaties

Berlin Treaty of 1921, 42 Stat. 1939............................. 13, 17

vii

Page

Pour Power Occupation Agreement, 5 U.S.T. 2062 (1945)........... 6, 10, 14,

15, 22, 23,

39, 40, 42, 43

Hague Convention of 1907, 36 Stat. 2277.......................... 6, 10, 11,

12, 13, 15,

22, 23, 39, 40

Income Tax Convention between the United States and the United

Kingdom, 60 Stat. 1377 (1945)............................... 23

Kellogg-Briand Pact, 46 Stat. 2343 (1929)........................ 6, 10, 13,

15, 22, 23,

39, 40

Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Prance and the United States,

8 Stat. 12 (1778)........................................... 28

Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Prussia and the United

States, 8 Stat. 84 (1785)................................... 28

Treaty between Japan and the United States, 37 Stat. 1504 (1911). 23

Treaty between Mexico and the United States, 59 Stat. 1219 (1945) 24

Treaty between the United States and the Sioux Indians, 15 Stat.

505 (1867).................................................. 20

Treaty between the United States and the Swiss Confederation, 11

Stat 587 (1850)...... 22

Treaty of Canandaigua of 1794, 7 Stat. 44....................... 19, 20

Treaty of Port Harman of 1789, 7 Stat. 33................. 19, 20

Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1784, 7 Stat. 15...................... 19, 20

Treaty of Friendship between Spain and the United States, 8 Stat.

138 ( 1795) ..................................................................................................................................................................... 28

Treaty of Peace and Amity between Algiers and the United States,

8 Stat. 133 (1795).......................................... 28

Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Morocco and the United

States, 8 Stat. 100 (178 7).................................. 28

viii

Page

Treaty of Versailles, S. Doc. No. 348, 67th Cong., 4th Sess.

3329 (1923)........ ......................................... 6> 10> 13’

14, 15, 17,

22, 23, 39, 40

Statutes

28 U.S.C. §1331.................................................. 13, 38, 45,

46, 53, 55

28 U.S.C. §1332.................................................. 37

28 U.S.C. §1343.................................................. 58

28 U.S.C. §1350................................................. 13, 25, 26,

28, 29, 30, 32

28 u .s .c . §1363................................................................................................... 50

28 u .s .c . §1983................................................................................................... 58

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e....................... 54

Judiciary Act of 1789, 1 Stat. 73................................. 26

Judiciary Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 470.............................. 45, 46

Military Government laws

Military Government Law No. 59, 12 Fed. Reg. 7983 (1947) ......... 2, 6, 8,

14, 42, 44,

45, 53, 54, 55

Other Authorities

Brierly, The Law of Nations (6th ed. 1963)....................... 27

Elliott, Journal of the Federal Convention....................... 46

ix

Page

Elliott's Debates (1888)......................................... 27

The Federalist No. 80 (J. Cooke ed. 19 6 1) (Hamilton)............ 28

Restatement (2nd) of Foreign Relations........................... 18

Warren, The Making'of the Constitution (1929)................... ^6

x

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

■X

WILLY DREYFUS, :

Plaintiff-Appellant, :

-against- : Docket No. 75-7135

AUGUST von FINCK and MERCK, :

FINCK & CO.,

Defendants-Appellees.

•X

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES

AUGUST von FINCK and MERCK, FINCK & CO.

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Plaintiff-appellant ("plaintiff") appeals from an order dated

January 21, 1975* of Judge Charles L. Brleant, Jr. of the United States

District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissing plaintiff’

amended complaint (App. R) for failure to state a claim upon which relief

can be granted.

* A copy of the January 21, 1975 order is set forth in the Joint

Appendix as document "U". Hereafter, references to documents

contained in the Joint Appendix will be to "App." followed by

the letter by which the document is designated therein, as, e.g.,

"App. U".

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Did the district court err in holding that plaintiff's

amended complaint failed to state a claim for relief under the treaties

alleged therein?

2. Did the district court err in holding that plaintiff's

amended complaint failed to state a claim for relief under the law of

nations?

3. Does the Act of State doctrine permit the exercise of

jurisdiction over plaintiff's claims?

4. Do the federal courts have subject matter jurisdiction

over plaintiff's claims under the law of nations and the treaties of the

United States?

5. Do the federal courts have subject matter jurisdiction

over plaintiff's claims under Military Government Law No. 59?

6. Has the plaintiff stated a claim for relief under Military

Government Law No. 59?

7. Should plaintiff's common law claims be adjudicated under

the doctrine of pendent jurisdiction?

-2-

STATEMENT OP THE CASE

This is an action commenced in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York by a citizen and resident of

Switzerland against two citizens and residents of West Germany based on

events which took place entirely in Germany more than 25 years ago.

Plaintiff purported to obtain jurisdiction over the foreign

defendants by attaching their bank accounts in New York and by mailing

copies of the summons and complaint to the defendants in West Germany.

The amended complaint

The amended complaint (App. R) alleges that plaintiff Willy

Dreyfus is a citizen and resident of Switzerland (f 1) and that de

fendants are residents and citizens of West Germany (HH 3 and 4).

The amended complaint also alleges that in 1938 the Nazis

compelled plaintiff, who was Jewish, to transfer the German banking firm

of J. Dreyfus & Co., and all of his interests therein, to the defendants

at a completely unfair, illegal, inadequate and inequitable price; that

plaintiff and his family were forced to leave Germany; that plaintiff

sought appropriate compensation from the defendants after the end of

World War II and entered into a settlement agreement in 194b, which

defendants thereafter allegedly refused to honor and, in fact, renounced.

- 3-

The amended complaint seeks damages and an accounting, but

does not offer any explanation why plaintiff waited 25 years to bring

the present action.

The commencement of this action

On December 12, 1973 plaintiff filed his original complaint

and on January 15, 197^ plaintiff obtained an ex parte order of attach

ment from the district court in the amount of $150,000 which was used to

tie up bank accounts maintained by defendants in New York (App. E).

Plaintiff posted a $15,000 bond (App. F).

In order to free their bank accounts, and without in any way

conceding the validity of the attachment or consenting to jurisdiction,

the defendants had to post a bond of $150,000 (not $15,000 as plaintiff

incorrectly alleges at page 5 of his appeal brief) (App. G) and the

attachment was vacated by a consent order dated February 5, 1974.

Defendants' motion to dismiss the original complaint

Defendants moved (App. H), pursuant to Rule 12(b) of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to dismiss the complaint on the

following grounds: (a) lack of subject matter jurisdiction, (b) lack of

personal jurisdiction, (c) forum non conveniens, and (d) insufficient

service of process, but subsequently waived their challenge to suf

ficiency of service and deferred, without prejudice, their claim of lack

of personal jurisdiction and forum non conveniens.

-4-

In their motion papers, defendants pointed out, inter alia,

that the complaint neglected to inform the court that the parties had

litigated the validity of the 194b settlement in the German courts and

had ultimately entered into a new settlement agreement dated February

12, 1951 which ended the litigation and settled all of plaintiff's

claims against defendants upon payment by defendants to plaintiff of

a substantial sum. Defendants submitted as Exhibit "B" a copy of an

opinion dated March 7, 1951 by the Court of Restitution Appeals of the

United States Courts of the Allied High Commission for Germany ("CORA")

which states, at page 2:

"The motion was set for hearing before us on the 12th day

of February, 1951. Whereupon, in open court, the parties

announced to the Court that they had arrived at an ami

cable settlement and they requested that a signed agree

ment be recorded. This was accepted and recorded."

and at page 4:

"It is further ordered that the joint motion of the parties

to withdraw the Motion for Recall and for other appro

priate relief be, and the same is hereby granted. The

claimants petition is dismissed."

(Reply Affidavit of William Schurtman, sworn to April 26, 1974; App. K)

The reference to this superseding 1951 court-approved settle

ment, which was artfully omitted from the original and also from the

later amended complaint*, is relevant on this appeal because of plaintiff's

Plaintiff is in error when he claims at page 4 of his brief on

appeal that he alleged the 1951 settlement in his amended

complaint. He did not.

-5-

decision to broaden the issues before this Court by relying on Military

Government Law No. 59 - the very law under which CORA approved the

1951 settlement some twenty-four years ago. (See plaintiff's appeal

brief, p. 33).

Plaintiff's brief on this appeal alleges for the first time -

but still without the particularity required by Rule 9(b) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure - that the 1951 settlement was fraudulent.

Moreover, plaintiff's brief on appeal again fails to explain why plaintiff

waited more than twenty years before making this claim.*

In a memorandum opinion dated May 20, 197^ (App. L), Judge

Brieant concluded that the district court had subject matter juris

diction, but dismissed the complaint for failure to state a claim upon

which relief could be granted. He expressly held that the treaties on

which plaintiff relied - the Hague Convention, the Kellogg-Briand Pact,

the Treaty of Versailles and the Four Power Occupation Agreement - did

not give rise to private causes of action, and also that the Act of

State doctrine barred the district court from considering the legitimacy

of the acts of the German government.

Since the district court twice dismissed the complaint for failure

to state a claim, defendants have not been required to file an

answer. If an answer were necessary, it would include not only a

denial of the allegations of wrongdoing, but also defenses of pay

ment, release, settlement, accord and satisfaction, statute of limi

tations and laches. In addition, defendants would renew their

motion to dismiss the action on the ground of forum non conveniens

since the action involves a Swiss plaintiff, German defendants, events

which took place entirely in Germany, evidence and witnesses located

in Germany, proof in the German language, and no explanation by

plaintiff why this action cannot or should not be brought in a West

German court.

-6-

The amended complaint

Plaintiff moved for rehearing and reargument (App. N). By

order dated June 26, 1974 (App. Q), the district court granted the

motion and modified the May 20, 1974 memorandum opinion to permit

plaintiff to file an amended complaint that:

"... shall allege with particularity specific pro

visions of such treaty or treaties relied upon."

Plaintiff then served defendants with an amended complaint

(App. R) which was substantially similar to the original complaint (App.

B), but which purported to conform to the judge's requirement that the

treaty provisions be specified with particularity.

The dismissal of the amended complaint

Defendants then moved (App. S) to dismiss the amended complaint

principally on the grounds of failure to state a claim and lack of

subject matter jurisdiction.*

By a memorandum opinion dated January 2, 1975, the district

court dismissed the amended complaint for failure to state a claim on

which relief could be granted. The district court also suggested,

though it noted that it need not so hold, that the Act of State doctrine

barred consideration of plaintiff's claims (App. T).

The motion also asserted the grounds of lack of personal juris

diction and forum non conveniens, but these issues were deferred

without prejudice.

-7-

Plaintiff's expansion of the Issues on this appeal

On February 18, 1975, plaintiff filed a Notice of Appeal and,

on May 15, 1975, moved (App. V) to remand this action to the district

court on the ground that plaintiff had failed to raise in the district

court a question of law allegedly necessary for the resolution of the

case, namely, the applicability of Military Government Law No. 59- De

fendants objected on the ground that Military Government Law No. 59

had been expressly called to the attention of the district court by de

fendants in their Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiff's Motion for

Rehearing and Reargument, which stated, at page 10:

"The Four Power Occupation Agreement is neither self-executing

nor sufficiently precise nor detailed to permit judicial en

forcement. It was implemented by Military Government Law No.

59 (the "Restitution Law"), which expressly authorized victims

of Nazi laws to institute restitution actions in Germany.

Actions were initiated in local German courts called Restitution

Chambers; the Court of Restitution Appeals ("CORA"), an

American court in Germany, had exclusive jurisdiction of

appeals, (cf. the 1951 CORA decision in the Dreyfus action,

annexed as Exhibit B to defendants' reply affidavit by

William Schurtman, sworn to April 26, 197^0.

Since plaintiff himself invoked the benefits of the Restitution

Law by suing the defendants and obtaining a disposition of the

case in the Court of Restitution Appeals, it is most sur

prising that he overlooks the fact that the basis for that

action was Military Government Law No. 59, not the Four

Power Occupation Agreement."

During oral argument on plaintiff's remand motion, defendants'

counsel stipulated that in the interest of leaving a prompt disposition

of plaintiff's appeal, defendants would not object to this Court's

considering Military Government Law No. 59, the allegedly overlooked

law. Counsel's stipulation was subsequently confirmed by letter. (App. X).

ARGUMENT

POINT I

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY HELD

THAT PLAINTIFF HAS FAILED

TO STATE A CLAIM UNDER ANY

TREATY OF THE UNITED STATES

The decision of the district court

Judge Brieant, in his memorandum opinion of January 2, 1975

(App. T), dismissed plaintiff's amended complaint for failure to state a

claim upon which relief could be granted. The district judge did not,

as plaintiff erroneously contends on this appeal, hold that the district

court lacked subject matter jurisdiction but, on the contrary, expressly

held that it did have subject matter jurisdiction:

"This District Court has subject matter jurisdiction,

because the right of plaintiff to recover under his

complaint will be sustained if the treaties of the

United States are given one construction, and will

be defeated if they are given another." (memorandum

opinion of May 20, 1974 [App. L], incorporated by

reference in the January 2, 1975 memorandum opinion

[App. T]*.

Defendants do assert on this appeal, as an alternative argument

to sustain the dismissal of the complaint, that the district

court also lacked subject matter jurisdiction. (See Point

IV, infra.)

- 9-

The treaties relied on by plaintiff

Plaintiff, In his amended complaint (App. R), claimed that he

had been injured by actions which defendants allegedly took in viola

tion of the Hague Convention of 1907, 36 Stat. 2277, the Treaty of

Versailles, S. Doc. No. 348, 67th Cong., 4th Sess. 3329 (1923), the

Kellogg-Briand Pact, 46 Stat. 2343 (1929), and the Four Power Occupa

tion Agreement, 5 U.S.T. 2062 (1945).

As defendants show below, none of these treaties prohibited

the German government or any of its citizens from expropriating

property situated in German territory irrespective of whether it was

owned by Germans or aliens. Furthermore, none of the cited treaties

conferred any rights on private individuals.

A. The Hague Convention

The only portions of the Hague Convention on which

plaintiff purports to rely are the Preamble and Articles 1, 41 and 46.

The Hague Convention was an attempt to impose restrictions on

the ways in which belligerent powers could wage war, and governed such

areas as the treatment of prisoners of war and inhabitants of occupied

- 1 0 -

territory.

The Preamble merely stated that in the absence of provisions

covering specific situations, the warring nations should be governed by

"the principles of the law of nations, as they result from the usages

established among civilized peoples, from the laws of humanity, and the

dictates of the public conscience." (36 Stat. 2280).

The Preamble does, however, cleanly define and limit the scope

and applicability of the Hague Convention. The Convention's provisions,

the Preamble states:

"... are intended to serve as a general rule of conduct for the

belligerents in their mutual relations and in their relations

with the inhabitants*." (36 Stat. 2279)-

While the reference to "inhabitants" is ambiguous, Judge Brieant

concluded, and the context clearly shows, that the inhabitants

referred to are the citizens and residents of countries occupied

by, or at war with, the belligerent powers. See, e.g., Articles 2,

44 and 45 of the Regulations respecting the laws and customs of war

on land:

Article 2

"The inhabitants of a territory which has not been occupied,

who, on the approach of the enemy, spontaneously take up arms

to resist the invading troops without having had time to

organize themselves in accordance with Article 1, shall be re

garded as belligerents if they carry arms openly and if they

respect the laws and customs of war." (36 Stat. 2296).

Article 44

"A belligerent is forbidden to force the inhabitants of ter

ritory occupied by it to furnish information about the army of

the other belligerent, or about its means of defense." (36

Stat. 2306).

Article 45

"It is forbidden to compel the inhabitants of occupied ter

ritory to swear allegiance to the hostile Power." (36 Stat.

2306).

- 1 1 -

Article 1 of the Convention, which provides:

"The Contracting Powers shall issue instructions to their armed

land forces which shall be in conformity with the Regulations

respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, annexed to the

present Convention." (36 Stat. 2290).

clearly pertains solely to nations and their armies, and defendants come

within neither category. Moreover, Article 2 specifically provides that

the Regulations cited by plaintiff:

"...do not apply except between Contracting Powers, and then

only if all the belligerents are parties to the Convention."

(36 Stat. 2290).

Article 4l of the Regulations provides:

" X violation of the terms of the armistice by private persons

acting on their own initiative only entitles tha,Jjiiiff£dJ2arty

to demand the punishment of the offenders or, if ngpessary,?

compensation for the losses sustained." (36 Star? 2;306j'.

But Article 40, which provides:

"Any serious violation of the armistice by one of the parties

gives the other party the right of denouncing it, and even, in

cases of urgency, cf recommencing hostilities immediately."

(36 Stat. 2305-2306),

clearly shows that the injured "party" referred to in Article 4l is a

"state", with the consequence that only nations, and not private in

dividuals, have the right to demand compensation in the event that a

private party violates the Convention.

Article 46 is equally inapposite. It provides:

"Family honour and rights, the lives of persons, and private

property, as well as religious convictions and practice, must

be respected.

Private property cannot be confiscated." (36 Stat. 2306-2307).

- 1 2 -

At first glance the reference to confiscation of property

might seem in point, but Article 46 is a part of a group of Regulations

headed: "Military Authority over the Territory of the Hostile State".

Consequently it is clear that Article 46 prohibits confiscation of

property of citizens of occupied nations, and has no bearing on de

fendants' alleged conduct or plaintiff's right to obtain relief under

the Hague Convention.

B. The Kellogg-Briand Pact

The Kellogg-Briand Pact, 46 Stat. 2343 (1929), is equally

inapplicable. As plaintiff has earlier conceded, it is but "a sweeping

declaration renouncing war as an instrument of national policy"*, and

there is nothing in the language or history of the Pact that indicates

any intent to confer rights or impose duties on individuals or businesses.

C. The Treaty of Versailles

Even assuming that the Treaty of Versailles, S. Doc. No.

348, 67th Cong. 4th Sess. 3329 (1923), is a treaty within the meaning of

28 U.S.C. §1331 or §1350 (a most dubious proposition since it was never

ratified by the United States, and since the 1921 Treaty of Berlin, 42

Stat. 1939, on which plaintiff apparently relies, only provided that the

* Quoted from plaintiff's brief in support of his petition for re

hearing and reargument, p. 1 9 .

-13-

United States would be granted by Germany some of the benefits bestowed

by the Versailles Treaty upon its signatories), the Articles cited by

plaintiff are patently unrelated to his claims. They merely required

Germany to pay reparations for damages suffered by French nationals at

the bands of German nationals (Article 124), permitted the Allies, with

the cooperation of Germany, to prosecute German citizens for war crimes

committed during World War I (Articles 227-230), fixed responsibility

for damage done Allied countries and their citizens by Germany and her

allies during World War I (Article 231), and provided that Allied

nationals injured by acts done in Germany during World War I could file

complaints in a newly created arbitration tribunal (Article 300).

D. The Four Power Occupation Agreement*

The Four Power Occupation Agreement (Agreement on Control

Machinery in Germany), 5 U.S.T. 2062 (1945), simply provided for the

governance of occupied Germany by the United States, England, the Soviet

Union and France during the period at the end of World War II in which

Germany was "carrying out the basic requirements of unconditional surrender".

It contains no provisions that relate in any way to private individuals.

This treaty will be discussed in greater detail in relation to

Military Government Law No. 59 in Point V, infra.

-14-

Plaintiff does not have the right to sue

defendants under the Hague Convention, the

Kellogg-Briand Pact, the Treaty of Versailles

or the Four Power Occupation Agreement_______

After reviewing the provisions of the treaties relied on by

plaintiff, Judge Brieant held that they conferred no express rights on

individuals, and declined to imply a private right of action under

them:

"We find no authority, and none is cited to us in which

a private cause of action arising out of extraterritorial

acts, but justiciable in the federal courts, has been

asserted successfully as arising by implication out of

any international treaty.

When the international lawyers and diplomats desire to

create a private right arising out of a treaty, they

know how to do so. The classic example, of course, is

the Warsaw Convention, by which private causes of action

were created by express language of the Convention it

self, against international air carriers for the benefit of

passengers and shippers. See Chapter Three thereof,

and particularly Article 28(1) which fixes the venue

for the private action.

The learning with respect to international compacts dif

fers from the interpretation of legislative intent

followed by our courts in implying private rights of action

under remedial statutes such as the federal securities

laws. An accepted principle of international law seems

to be that to create a private right or obligation, the

treaty must, as in the case of the Warsaw Convention,

express a clear intent so to do." (Memorandum opinion

dated May 20, 1974, pages 11-12, App. L)

Defendants submit that Judge Brieant's decision is correct

and in accord with a long line of cases (discussed below) in which the

courts, in recognition of the limited role the judiciary should play

-15-

in the area of foreign affairs, have, for the purpose of determining

which claims could properly be adjudicated, distinguished between

treaties which, either by their express terms or reasonable implica

tion, confer rights on individuals, and those, like the ones on which

plaintiff purports to rely, which are either broad policy pronouncements

or pacts regulating the relations of the convenanting nations with one

another.

The Supreme Court, in Edye v. Robertson, 112 U.S. 580 (1884)

(the Head Money Cases), stated the distinction as follows:

"A treaty is primarily a compact between independent

Nations. It depends for the enforcement of its pro

visions on the interest and the honor of the govern

ments which are parties to it. If these fail, its

infraction becomes the subject of international ne

gotiations and reclamations, so far as the injured

party chooses to seek redress, which may in the end

be enforced by actual war. It is obvious that with

all this, the judicial courts have nothing to do

and can give no redress. But a treaty may also contain

provisions which confer certain rights upon the

citizens or subjects of one of the Nations residing

in the territorial limits of the other, which partake

of the nature of municipal law, and which are capable

of enforcement as between private parties in the

courts of the country. An illustration of this

character is found, in treaties which regulate the

mutual rights of citizens and subjects of the con

tracting Nations in regard to rights of property

by descent or inheritance, when the individuals con

cerned are aliens. The Constitution of the United

States places such provisions as these in the same

category as other laws of Congress by its declaration

that 'This Constitution and the laws made in pursuance

thereof, and all treaties made or which shall be made

under authority of the United States, shall be the

supreme law of the land.' A treaty, then, is a law

of the land as an Act of Congress is, whenever its

-16-

provisions prescribe a rule by which the rights

of the private citizens or subject may be determined.

And when such rights are of a nature to be enforced

in a court of justice, that court resorts to the

treaty for a rule of decision for the case before

it, as it would to a statute." (Id. at 598-599).

And Z&F Assets Realization Corp. v. Hull, 114 F.2d 464 (D.C.

Cir. 1940), aff!d , 311 U.S. 470 (1941), applying the test set forth in

the Head Money Cases, held that a private party’s claim that its rights

under the Berlin Treaty of 1921* had been infringed did not state a

justiciable controversy:

"The compact [the Treaty of Berlin] is between the

two governments; the citizens [plaintiffs] are not

parties thereto; and no provision is made or contem

plated therein, for submitting any question to the

courts." (Id. at 472.) (footnote omitted.)

Similarly, in Pauling v, McElroy, 164 F. Supp. 390 (D.D.C.

1958), aff'd, 278 F.2d 252 (I960), cert, denied, 364 U.S. 835 (I960),

the court held that a private citizen cannot enforce treaties that do

not purport to grant individuals rights:

"The provisions of the Charter of the United Nations,

the Trusteeship Agreement for the Trust Territory of

the Pacific Islands, and the international law principle

of freedom of the seas relied on by plaintiffs are not

self-executing and do not vest any of the plaintiffs

with individual legal rights which they may assert

in this Court. The claimed violations of such inter

national obligations and principles may be asserted

only by diplomatic negotiations between the sovereign

ties concerned." (Id. at 393.)

As previously noted, on page 15, supra, the Treaty of Berlin is

alleged by plaintiff as the basis for his assertion that the Treaty

of Versailles, which was never signed or ratified by the United

States, Is nevertheless a "treaty of the United States".

-17-

Accord: People of Saipan v. United States Department

of Interior, 35(Tf . Supp.“545 (D. Haw. 1973).

These principles have also been recognized and codified in the

Restatement (2nd) of Foreign Relations, which bars actions by aliens

against a state absent express authorization, §17 5, and remits to the

state of which the alien is a national the sole right to seek redress of

his Injuries, §174. See also §1, Comment f.

While plaintiff cites a plethora of cases where courts have

held that they have jurisdiction to consider claims allegedly based on

treaties, an examination of these cases shows that In every instance in

which the courts held that the plaintiff had stated a claim upon which

relief could be granted, the plaintiff was either itself a party to the

treaty (as in the cases involving Indian tribes) and thus clearly had

standing to sue under it, or the treaty relied on expressly conferred

rights on private individuals.

The bulk of the cases cited by plaintiff involve the rights of

Indians under treaties between the United States and their tribes.

These cases include: DeCoteau v. District County Court, 95 S.Ct. 1082

(1975); Antoine v. Washington, 95 S.Ct. 944 (1975); Oneida Indian Nation

v. County of Oneida, 414 U.S. 661 (1974); McClanahan v. State Tax Com

mission of Arizona, 4ll U.S. 164 (1973); Skokomish Indian Tribe v.

France, 269 F.2d 555 (9th Cir. 1959); Phelps v. Hanson,* 163 F.2d 973

* Plaintiff's reference to Phelps v. Hanson is both puzzling and mis

leading, since the Ninth Circuit held that the district court

lacked subject matter jurisdiction Inasmuch as the complaint did

not raise any federal question.

-18-

(9th Cir. 1947); Leech Lake Band of Chippewa Indians v. Herbst, 334 F.

Supp. 1001 (D. Minn. 1971); Dodge v. Nakai, 298 F. Supp. 17 (D. Ariz.

1968); and Makah Indian Tribe v. McCauly, 39 F. Supp. 75 (W.D. Wash.

1941).

Oneida Indian National, Skokomish Indian Tribe, Leech Take

Band of Chippewa Indians, and Makah Indian Tribe, supra, all involve suits

by Indian tribes to enforce specific rights conferred on them by treaties

to which they were parties.

Oneida Indian Nation, supra, is representative of this group

of cases and well illustrates the significant differences between the

treaties relied on by the Indians and those alleged herein by plaintiff.

The plaintiffs in Oneida Indian Nation were the Oneida Indian

Nation of New York State and the Oneida Indian Nation of Wisconsin. The

defendants were the Counties of Oneida and Madison in New York State.

Plaintiffs alleged, inter alia, that pursuant to three treaties

between the Oneidas and the United States - the Treaty of Fork Stanwix

of 1784, 7 Stat. 15, the Treaty of Fort Harman of 178 9, 7 Stat. 33, and

the Treaty of Canandaigua of 1794, 7 Stat. 44 - the Indians had the

right to occupy certain land which had wrongfully been taken from them.

Since the plaintiffs were themselves parties to the treaties

on which they relied, their standing to sue under those treaties could

not be doubted. Moreover, the rights the Oneidas sought to enforce were

specifically granted by those treaties. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix

-19-

stated that:

"[t]he Oneida and Tuscarora nations shall be

secured in the possession of the lands on

which they are settled",

and under the Treaty of Fort Harman, plaintiffs were "again secured and

confirmed in the possession of their respective lands". Moreover,

Article II of the Treaty of Canandaigua provided:

"The United States acknowledge the lands reserved

to the Oneida, Qnandaga and Cayuga Nations, in

their respective treaties with the state of New

York, and called their reservations, to be their

property; and the United States will never claim

the same nor disturb them...in the free use and

enjoyment thereof..." (The aforequoted passages

from the Oneida treaties are set forth in the

Supreme Court’s opinion at 414 U.S. 664, n.3-)

Dodge v. Nakai, supra, differs from the preceding Indian tribe

cases only in that the Indian tribe was a defendant, rather than a

plaintiff. The remaining Indian cases, DeCoteau v. District County

Court, Antoine v. Washington and McClanahan v. State Tax Commission of

Arizona, supra, are also readily distinguishable.

In DeCoteau, Sioux Indians claimed that under a 1867 treaty

between their tribe and the United States, 15 Stat. 505, the states in

which they resided had no jurisdiction over them. The Supreme Court

held that the treaty had been superseded by a subsequent act of Congress.

Consequently, the Court did not reach the question of their rights, if

any, under that treaty.

In both Antoine and McClanahan, however, the Supreme Court

- 2 0 -

upheld the right of individual Indians to be free of state regulations.

McClanahan involved the right of a state to tax the income earned by

an Indian on a reservation. Following a long line of cases, the Supreme

Court held that within reservations, Indians had exclusive sovereignty

of their affairs. Consequently, the decision did not revolve around

the rights of individual Indians under treaties but rather the

jurisdiction of states within reservations and the question of whether

federal law preempted the field.

Similarly, Antoine held that under an act of Congress which

ratified an agreement between plaintiffs' tribe and the United States,

the states were not free to interfere with the right of tribe members

to hunt and fish. Like McClanahan, the central question was one of

whether the federal government had exclusive power to regulate the

affairs of the Indians.

The non-Indian cases cited by plaintiff are equally inap

posite.

Corbett v, Stergios, 381 U.S. 124 (1965) 3 Kolovrat v. Oregon,

366 U.S. Ib7 (1961), Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 U.S. 433 (l880), and

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, 14 U.S. (1 Wheat.) 304 (18 16), all involved

the question of the rights of aliens to acquire, inherit, hold or sell

land in the United States under treaties which specifically granted them

those rights. Since Hauenstein v. Lynham, supra, is representative of

these cases, defendants will limit their discussion to Hauenstein to

- 2 1 -

avoid unnecessary repetition.

Kauenstein held that Swiss citizens had the right, under an

1850 Treaty between the United States and the Swiss Confederation, 11

Stat. 587, to sell property which, under Virginia law, they were not

permitted to inherit.

Unlike the Hague Convention, the Kellogg-Briand Pact, the

Treaty of Versailles and the Pour Power Occupation Agreement, the Swiss-

American Treaty specifically and unambiguously conferred rights on the

citizens of those two nations. Article 5 of the Treaty states, in

pertinent part:

"...in case real estate situated within the territories

of one of the contracting parties should fall to a citi

zen of the other party, who, on account of his being

an alien, could not be permitted to hold such property

in the State or in the canton in which it may be situated,

there shall be accorded to the said heir, or other suc

cessor, such term as the laws of the State or canton

will permit to sell such property; he shall be at liberty

at all times to withdraw and export the proceeds thereof

without difficulty, and without paying to the government

any other charges than those which, in a similar case,

would be paid by an inhabitant of the country in which

the real estate may be situated." (quoted in Hauenstein

v. Lynham, 100 U.S. at 486) (emphasis supplied).

Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U.S. 332 (1924), although it does not

involve land, is quite similar to the foregoing group of cases. Plaintiff

was a Japanese citizen domiciled in the state of Washington who, because

of his nationality, was denied the right, under a Seattle ordinance, to

operate a pawnshop in that city. The Supreme Court held the ordinance

-22-

Invalid on the ground that it conflicted with a 1911 treaty between

Japan and the United States, 37 Stat. 1504.

Unlike the Hague Convention, the Kellogg-Briand Pact, the

Treaty of Versailles and the Four Power Occupation Agreement, the

Japanese-American Treaty was clearly intended to confer specific rights

on the citizens of Japan and the United States:

"The citizens or subjects of each of the high contracting

parties shall have liberty to enter, travel and reside

in the territories of the other to carry on trade, whole

sale and retail, to own or lease and occupy houses, manu

factories, warehouses and shops, to employ agents of their

choice, to lease land for residential and commercial pur

poses, and generally to do anything incident to or necessary

for trade upon the same terms as native citizens or subjects,

submitting themselves to the laws and regulations there

established.... The citizens or subjects of each...shall

receive, in the territories of the other, the most constant

protection and security for their persons and property..."

(Asakura v. Seattle, 265 U.S. at 340).

Maximov v. United States, 373 U.S. 49 (1963), merely held that

a domestic trust was a separate taxable entity, apart from its bene

ficiaries, and thus did not qualify for the benefits which the 1945

Income Tax Convention between the United States and the United Kingdom,

60 Stat. 1377, bestowed on residents of Great Britain.

Hidalgo County Water Control and Ixrprovement District v.

Hedrick, 226 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. 1955), the final case cited by plaintiff

to bolster his contention that the district court improperly dismissed

his claim under the Hague Convention, the Kellogg-Briand Pact, the

Treaty of Versailles and the Four Power Occupation Agreement, held that

the plaintiffs therein, two individuals and two political subdivisions

-23-

of the State of Texas, failed to state a claim for relief under the

Mexican-American Treaty of 1945, 59 Stat. 1219 (19^5)-

Plaintiff has thus failed to cite a single case in which a

court has held that a private individual has standing to sue under a

United States treaty that does not expressly confer specific rights

on the claimant.

Consequently, it is respectfully submitted that this Court

should affirm the district court's holding that plaintiff has failed

to state a claim under a treaty of the United States because:

(1) defendants' alleged conduct did not violate

any of the provisions of the cited treaties;

(2) none of the treaties on which plaintiff

relies confers specific rights on private

individuals; and

(3) this Court should not imply private rights

of action under such treaties.

- 2 4 -

POINT II

THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY

HELD THAT PLAINTIFF HAS FAILED

TO STATE A CLAIM UNDER THE LAW

__________ OF NATIONS__________

The court below also held that plaintiff failed to state a

claim under the law of nations clause of 28 U.S.C. §1350, which pro

vides, in pertinent part:

"The district court shall have original jurisdiction

of any civil action by an alien for a tort only,

committed in violation of the law of nations..."

Plaintiff, an alien suing two other aliens over an allegedly

tortious act occurring outside the United States, evidently claims that

any tort committed anywhere in the world by anyone (whether a United

States citizen or not) against anyone (other than a United States citizen),

which violates the law of nations, is cognizable by a United States

district court under §1350 even if the tort has no connection of any

kind with the United States.

Moreover, plaintiff apparently claims that the law of nations

protects the rights of individuals as well as nations.

As defendants show below, neither the history of §1350 nor

the decisions construing it support such a broad, untrammelled reading

of the statute. Indeed, such a construction of §1350 would convert the

United States courts into the policemen of the world.

Significantly, plaintiff has not cited, and defendants have

not found, a single case in which a federal court accepted jurisdiction

-25-

under §1350 of an action that did not involve some nexus with the

United States, such as a United States defendant or a tort committed in

the United States.

Nor has plaintiff cited, or defendants found, a single case in

which the courts held that an individual, as well as a nation, had

rights protected by the law of nations. In the one case where a court

upheld a claim under the law of nations clause of §1350, the Court made

it clear that while the individual alien had standing to sue under §1350,

his claim had to show that he was injured by a violation of his nation's

rights.* *

The law of nations

Although it has been the law since 1789 that an alien can sue

in the federal courts if he has been tortiously injured in violation of

the law of nations**, defendants have found only one case in which

jurisdiction was successfully asserted under the law of nations.* Con

sequently, such judicial construction as there is of the "law of nations"

is mainly dicta.

Scholarly commentary is not much more extensive, and centers

primarily on the applicability of the law to nations, rather than to

individuals. This is not surprising, however, since historically It was

* Adra v. Clift, 195 F. Supp. 857 CD. Md. 1961), discussed infra, at

page 29.

** §9 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, 1 Stat. 73, 77 provided that the

district courts shall have cognizance of:

"...all causes where an alien sues for a tort only in

violation of the law of nations..."

This provision is now contained in 28 U.S.C. §1350.

-26'

the state, and not its citizens, that asserted rights 'under the law of

nations.*

What little discussion there is of why the newly formed United

States was interested in protecting aliens' rights under the law of

nations suggests two principal reasons: first, a desire to expand the

trade of the United States both by encouraging foreigners to invest in

this country and by insuring reciprocal treatment of Americans abroad;

and second, a fear that absent federal control of the treatment of

aliens, one of the states might take action that could thrust the United

States into war.

The first of these concerns was expressed by James Madison

during the debates on the ratification of the Constitution, when he

noted that the inability of foreign merchants to obtain the protection

of the state courts had inhibited "many wealthy gentlemen from trading

or residing with us". 3 Elliott's Debates 583 (1888). This concern is

further evidenced by the fact that most of this nation's early treaties

explicitly provided for the right of citizens of the signatories to do

Plaintiff, at page 19 of his appeal brief, quotes the following

passage from Brierly, The Law of Nations (6th ed. 1963), but omits

the underlined portion which supports defendants' contention that

historically an individual could not sue under the law of nations:

"No state is legally bound to admit aliens into its

territory, but if it does so it must observe a certain

standard of decent treatment towards them, and their

own state may demand reparation for an Injury caused

to them by a failure to observe this standard.tT (id.

at 276)(emphasis supplied).

-27-

business in one another's territory*.

The latter point was stressed by Alexander Hamilton, who

observed:

"The union will undoubtedly be answerable to foreign

powers for the conduct of its members. And the re

sponsibility for an injury ought ever to be accompanied

with the faculty of preventing it. As the denial or

perversion of justice by the sentences of courts...is

with reason classed among the just causes of war, It

will follow that the federal judiciary ought to have

cognizance of all causes in which the citizens of

other countries are concerned." (The Federalist,

No. 80)

Neither of these two concerns, however, would suggest any

desire by the founding fathers to protect nonresident aliens from the

acts of foreign governments taken outside the territory of the United

States.

Nor do the few recent decisions Involving the law of nations

afford plaintiff any basis for bringing an action under §1350.

In Khedivial Line, S.A.E. v. Seafarers' International Union,

278 F.2d 49 (2nd Cir. i960), an action by an Egyptian ship owner to

enjoin a U.S. labor union from picketing its ships, this Court held that

the plaintiff did not state a claim for relief under the law of nations.

See, e.g., Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and the

United States, 8 Stat. 12 (1778); Treaty of Amity and Commerce

between Prussia and the United States, 8 Stat. 84 (178 5); Treaty of

Peace and Friendship between Morocco and the United States, 8 Stat.

100 (178 7); Treaty of Peace and Amity between Algiers and the

United States, 8 Stat. 133 (1795); and Treaty of Friendship between

Spain and the United States, 8 Stat. 138 (1795).

-28-

After noting that despite the age of §1350 and its pre

decessors, it had rarely been applied, and that the Court had found no

case which squarely based jurisdiction on a claim under the law of

nations, the Court observed that the plaintiff had failed to show that

the law of nations bestows rights on individuals, and not solely on

nations.

Adra v . Clift, 195 F. Supp. 857 (D. Md. 19 6 1), the one case

upholding jurisdiction under §1350's law of nations clause, also re

volved around the question of whether a nation's rights had been violated.

Plaintiff, a Lebanese national, alleged that his former wife,

who had remarried and who lived in the United States, had used a false

passport to get the child into the United States.

The court, in finding a violation of the law of nations,

stressed that misuse of a passport injures both the country that issued

it and the country that admits an alien in reliance on it:

"...despite the fact that the child Najwa was a Lebanese

national, not entitled to be admitted to the United

States under an Iraqi passport, defendant concealed Najwa's

name and nationality, caused her to be included in defendant's

Iraqi passport, and succeeded in having her admitted to

the United States thereby. These were wrongful acts hot

only against the United States, 8 U.S.C.A. §1182, 18 U1S.C.A.

§1546, but against the Lebanese Republic, which is en

titled to control the issuance of passports to its

nationals." (195 F. Supp. at 864-865) (emphasis supplied).

Lopes y. Reederei Richard Schroder, 225 F. Supp. 292 (E.D. Pa.

1963), and Valanga v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 259 F. Supp. 324 (E.D.

- 2 9 -

Pa. 1966), both held that the federal courts lacked subject matter

jurisdiction under §1350 over the claims of the defendants therein, in

the former case because the torts alleged - unseaworthiness and negli

gence - did not constitute violations of the law of nations, and in the

latter case because a suit for the recovery of insurance proceeds was

not a true tort action.

However, the courts did discuss the law of nations in some

depth and their review of its history supports defendants' contention

that it is primarily concerned with: (a) the relations of nations with

one another; and (b) offenses that disrupt or undermine the sovereignty

or economic base of nations.

Lopes quoted extensively from Kent's Commentaries, which

defined the "Law of Nations" as:

"that code of public instruction which defines the

rights and prescribes the duties of nations in their

intercourse with each other..." (quoted at 225 F.

Supp. 297),

and listed four offenses as coming within the scope of that law: vio

lation of passports, violation of ambassadors, piracy and the slave

trade.

Valanga concluded that:

"A violation of the law of nations means a violation

of those standards by which nations regulate their

dealings with one another inter se." (259 F. Supp.

at 328.)

Consequently, since defendants' alleged conduct caused no

injury to any nation, defendants have not violated the law of nations.

-30-

POINT III

PLAINTIFF'S CLAIMS ARE BARRED

BY THE ACT OF STATE DOCTRINE

In addition to finding that plaintiff failed to state a

claim either under a United States treaty or under the law of nations,

Judge Brieant also suggested in his January 2, 1975 opinion that

plaintiff's claims would in any event be barred by the Act of State

doctrine.

After analyzing this doctrine and its exceptions, Judge

Brieant concluded:

"We need not, however, rest our decision on this

ground, since for the reasons stated above, the

complaint fails to state a claim cognizable in

this court." (App. T, p. 22)

Defendants submit that Judge Brieant was correct in his

determination that It is not even necessary to reach the Act of

State doctrine in this case. However, since plaintiff has argued

the doctrine on this appeal, defendants further submit that if this

Court should find it necessary to consider the Issue, It should find

that plaintiff's claims are Indeed barred by the Act of State doctrine.

The meaning of the Act of State doctrine

The Act of State doctrine Is perhaps best set forth in Underhill

v. Hernandez, 168 U.S. 250 (1897), where Chief Justice Fuller said for a

-31-

unanimous Supreme Court:

"Every sovereign state Is bound to respect the Indepen

dence of every other sovereign state, and the courts

of one country will not sit in judgment on the acts of

the government of another done within its own territory.

Redress of grievances by reason of such acts must be

obtained through the means open to be availed of by

sovereign powers as between themselves." (Id. at 252.)

A. The Bernstein cases

The Act of State doctrine was applied by this Court in

Bernstein v. Van Heyghen Freres Societe Anonyme, 163 F.2d 246 (2nd Cir.

1947), cert, denied, 332 U.S. 771 (1947), when it declined to take

jurisdiction over a claim that the defendant had wrongfully obtained

plaintiff's property at an unfair price as a result of duress applied by

the Nazi government of Germany, a claim substantially similar to that

alleged by plaintiff in the instant litigation.

Although there have been two major developments in the Act of

State doctrine since Van Heyghen, defendants contend that Van Heyghen is

still the controlling precedent in this Circuit and requires the dis

missal of plaintiff's action.

The first of these developments was the decision of this Court

in Bernstein v. N.V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-Maatschappij,

210 F.2d 375 (2nd Cir. 1954), an action which, like Van Heyghen and the

instant case, involved an alleged improper acquisition of property as a

result of the actions of German officials prior to the commencement of

World War II.

-32-

The crucial distinction between Van Heyghen and Nederlandsche-

Amerik^nsche is that after this Court ordered the plaintiff in Nederlandsche-

Amerikaansche "to refrain from alleging matters which would cause the

court to pass on the validity of acts of officials of the German govern

ment", (210 P.2d at 375), the United States State Department issued a

press release and sent this Court a letter stating that:

"The policy of the Executive, with respect to claims

asserted in the United States for the restitution

of identifiable property (or compensation in lieu

thereof) lost through force, coercion, or duress

as a result of Nazi persecution in Germany, is to

relieve American courts from any restraint upon the

exercise of their jurisdiction to pass upon the

validity of the acts of Nazi officials." (quoted

by the Court at 210 F.2d 376.)

In reliance on the State Department's pronouncement, this

Court reversed its initial decision and held that the Act of State

doctrine was not applicable in cases involving Nazi actions.*

B. First National City Bank v.

Banco Nacional de Cuba

The second major development was the rejection of the

Bernstein exception by six Justices of the Supreme Court in First National

City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba, 406 U.S. 759 (1972),** thus, in

* The view that the Act of State doctrine need not be applied when

the Executive explicitly authorizes the courts to determine the

controversy on the merits has come to be known, and will be re

ferred to hereafter, as the "Bernstein exception".

** Plaintiff concedes that the Bernstein exception was rejected by six

justices in Banco Nacional. Brief on appeal of plaintiff, pp. 38-39*

-33-

effect, reinstating the policy, followed by this Court in Van Heyghen,

that courts should not review the validity of acts of other nations

taken within their own territory.

Plaintiff, however, seeks to avoid the implications of the

elimination of the Bernstein exception by contending that Banco Nacional

holds only that the courts are now free to decide for themselves when to

apply the Act of State doctrine, and that under the standards announced

in Banco Nacional de Cuba v^ Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964), this Court

should consider plaintiff's allegations on the merits.

A close reading of Sabbatino, however, shows that the case

supports defendant's contention that the Act of State doctrine bars

plaintiff's claims.

C . The Sabbatino decision

In Sabbatino, the Supreme Court held that under the Act

of State doctrine it was improper for the federal courts to consider the

validity of Cuba's expropriation of a Cuban corporation which was a

wholly-owned subsidiary of an American corporation.

Plaintiff points to a portion of the Supreme Court's

opinion In which Justice Harlan said that the need to apply the Act of

State doctrine was less where: (a) there was general agreement as to

the applicable law, (b) the act was taken by a government no longer in

existence, and (c) the issue in dispute was of minor Importance, and

-34-

contends that the instant litigation presents just such a situation.

Plaintiff, however, has wholly ignored Justice Harlan's dis

cussion of the widely divergent views which different nations have of

acts such as those from which defendants allegedly benefited.

In the first place, plaintiff overlooks Justice Harlan's

statement that:

"There are few if any issues in international law today

on which opinion seems to be so divided as the limitations

on a State's power to expropriate the property of aliens."

(376 U.S. at 428) (footnote omitted).

Plaintiff himself contends that he was an alien in Germany

both because he had dual Swiss and German citizenship (amended complaint,

112, App. R), and because Jews were regarded by the Germans as aliens

(plaintiff's brief on appeal, p. 11).

The heart of plaintiff's allegations is that the German govern

ment "...adopted the policy of making it impossible for Jews to own

economic assets including banking firms in Germany" (amended complaint,

1l8, App. R), a decision quite similar to Cuba's determination that its

sugar crop should not be controlled by foreigners. Consequently, plaintiff

can hardly claim that defendants' alleged conduct is a clear violation

of the law of nations.

Moreover, the right of a nation to expropriate the property of

an alien is a highly sensitive and Important issue that the courts would

do well to avoid:

"It is difficult to imagine the courts of this country em

barking on adjudication in an area which touches more sen

sitively the practical and ideological goals of the various

members of the community of nations." (376 U.S. at 430.)

(footnote omitted.)

-35-

Therefore, a decision that this Court is free to determine the

propriety of the former German policy on Jewish control of banks will

inevitably require this Court to take a position on the right of a

foreign government to expropriate the property of aliens who own in

dustries that are regarded as crucial to its economy, a decision the

Supreme Court in Sabbatino was not prepared to make, and a decision

which may have adverse effects on the State Department's negotiations on

behalf of American companies whose property has been expropriated by

countries throughout the Middle East and Latin America.

Similarly, if plaintiff is regarded as a German national

rather than as an alien, adjudication of his claims will require the

federal courts to take a position on the difficult and sensitive question

of the right of a foreign government, within its own borders, to act in

a discriminatory or even oppressive fashion towards classes of its

citizens, a question which, defendants submit, should not be reached in

a case having no legal nexus with the United States.

Conclusion

Consequently, this Court should decline to take jurisdiction

of plaintiff's claims under the law of nations on the ground that the

Act of State doctrine bars this Court from considering the validity of

the alleged expropriation of plaintiff's property.

-36-

POINT IV

THE DISTRICT COURT MCKED

SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION

OVER'PLAINTIFF'S CLAIM

The district court's decision

Defendants asserted both in their motion to dismiss plaintiff's

original complaint (App. H) and In their motion to dismiss plaintiff's

amended complaint (App. S) that the district court lacked subject

matter jurisdiction over plaintiff's claims. The district judge, how

ever, In reliance on Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (19^6), held that it had

such jurisdiction:

"...because the right of plaintiff to recover under

his complaint will be sustained if the treaties of

the United States are given one construction, and

will be defeated if they are given another." (memo

randum opinion of Judge Brieant, dated May 20, 197^,

App. L, page 5, incorporated by reference in memo

randum opinion of Judge Brieant, dated January 2,

1975, App. T.)*

For the reasons hereinafter set forth, defendants respectfully

During the hearing on defendants' motion to dismiss plaintiff's original

complaint, plaintiff conceded that there was no diversity jurisdiction

under §1332 since all parties were aliens. (App. L, p. 3)* Neverthe

less, the amended complaint alleges jurisdiction under §1332 on the

ground that defendants' bank accounts were attached in New York. (App.

R, 1f6)

Plaintiff misconstrues §1332. The cases are clear that it does

not apply to controversies between aliens. Karakatsanis v. Conquistador

Cia. Nav. S.A., 297 F. Supp. 723 (S.D.N.Y. 1965), Dassignienis v. Cosinos

Carriers & Trading Corp., 321 F. Supp. 1253 (S.D.N.Y. 1970). The citizen

ship of the banks which held defendants' funds Is wholly Irrelevant. In

the first place, they are not parties. Secondly, the citizenship of

garnishees does not affect or create diversity of citizenship jurisdic

tion. Bacon v. Rives, 106 U.S. 99 (1882).

-37-

contend that the district judge's determination was erroneous and that

the dismissal of the amended complaint should also be sustained for lack

of subject matter jurisdiction.*

Bell v. Hood

In Bell v. Hood, supra, the Supreme Court held that if a

plaintiff asserted a claim under the Constitution or the laws of the

United States, there was federal question jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C.

§1331 unless the alleged claim was "immaterial and made solely for the

purpose of obtaining jurisdiction" or was "wholly Insubstantial and

frivolous".** (327 U.S. at 682-683.)

The cases are clear that an appellee is free to raise on appeal:

"...any matter in the record in support of the district court's

order, including arguments previously rejected by the district

court..." United Optical Workers Union v. Sterling Optical

Co., Inc., 500 F.2d 220, 224 (2nd Cir. 197I01

even though the appellee did not cross-appeal. Dandridge v. Williams,

397 U.S. 471, 475, n.6 (1970); United Optical Workers Union v.

Sterling Optical Co., Inc., supra; and Blanton v. State University

of New York, 409 F.2d 377, 382, n.7 (2nd Cir. 1973).

Moreover, lack of subject matter jurisdiction may be raised at any

time, even on appeal and even on the court's own initiative.

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co. v. Mottley, 211 U.S. 149

(1908).

There appears to be no reason why the test of subject-matter

jurisdiction should vary when the claim is based on a treaty,

rather than on the Constitution or laws of the United States. Cf,

Hidalgo County Water Control v. Hedrick, 226 F.2d 1 (5th Cir.

1955).

-38-

Defendants do not deny that plaintiff's original and amended

complaint both seek recovery under treaties of the United States. They

do, however, contend that jurisdiction is wanting since the Hague Con

vention, the Kellogg-Briand Pact, the Treaty of Versailles and the Four

Power Occupation Agreement clearly afford no basis for plaintiff's

claims. This is not, as Judge Brieant suggested, a case where plaintiff's

right to recover turns upon the manner in which a treaty is construed.

Rather, it is a case where no reasonable interpretation of the treaties

in question sustains plaintiff's action.

The treaties on which plaintiff relies

Defendants have discussed the Hague Convention of 1907, 36

Stat. 2277, the Treaty of Versailles, S. Doc. No. 348, 67th Cong., 4th

Sess. 3329 (1923), the Kellogg-Briand Pact, 46 Stat. 2343 (1929), and

the Four Power Occupation Agreement, 5 U.S.T. 2062 (1945), in some

detail in Point I, supra, and will not repeat that discussion herein.

Defendants’ position, however, is that there is no reasonable basis for

contending that plaintiff has a bona fide claim against defendants under

those treaties.