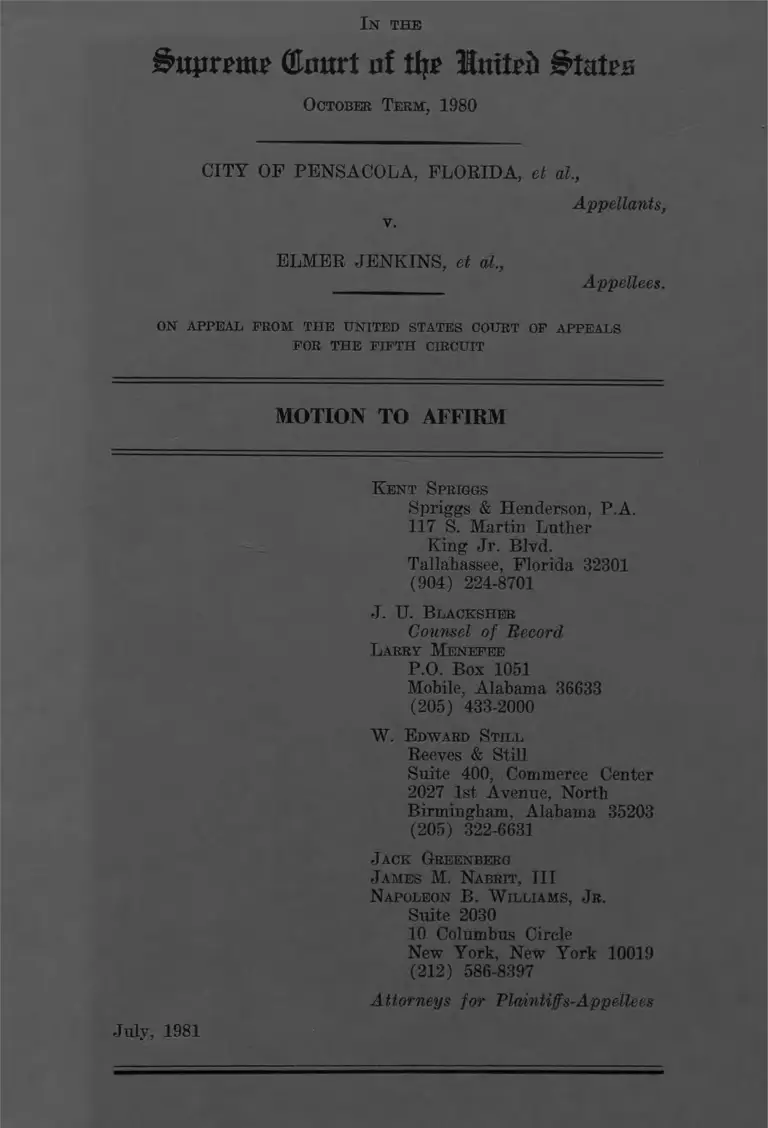

City of Pensacola, Florida v. Jenkins Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Pensacola, Florida v. Jenkins Motion to Affirm, 1981. d3b682fb-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cf1cad59-b484-4b3c-9c32-4969cf2d7592/city-of-pensacola-florida-v-jenkins-motion-to-affirm. Accessed March 06, 2026.

Copied!

In the

(tart of % Irntrti Stairs

October Term, 1980

CITY OF PENSACOLA, FLORIDA, et al,

Appellants,

v.

ELMER JENKINS, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Kent Spriggs

Spriggs & Henderson, P.A.

117 S. Martin Luther

King Jr. Blvd.

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

(904) 224-8701

J. U. Blacksher

Counsel of Record

Larry Menefee

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

(205) 433-2000

W. Edward Still

Reeves & Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 1st Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 322-6631

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Napoleon B. W illiams, Jr.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

July, 1981

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether, after concluding that

there was an invidious racial purpose

behind the adoption in 1959 of an at-large

municipal election system, the courts below

correctly based their findings of present

discriminatory effect on proof that as a

result of the at-large plan black can

didates are consistently defeated by a

bloc-voting white majority.

2. Whether the courts below properly

applied the principles of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp.

to the evidence in this case — which met

all the Arlington Heights criteria, includ

ing open admissions of racial motive — to

find invidious intent in the adoption of an

at-large election scheme.

i

f the finding of racially

discriminatory intent by the courts below

was erroneous, whether Pensacola's at-large

election system nonetheless violates the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, the

fourteenth amendment or the fifteenth

amendment.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED .................. i

I. THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE

INSUBSTANTIAL .............. 1

II. THERE ARE ALTERNATIVE STATU

TORY AND CONSTITUTIONAL

BASES FOR THE RULING BELOW .. 20

CONCLUSION ........................... 22

- iii -

Table of Authorities

Page

Cases

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 (1977) ..... i f 4,1 0 ,14,

15,17 ,21

Branti v. Finkel, 445 U.S 507

(1980) .. 18

City of Mobile V. Bolden, 446 U.S

55 (1980) --- 2,3,4,5 ,6,

00 V

O to ,22

Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979) ___ 18

Graver Tank & Mf g. Co. v. Linde Air

Products, 336 U.S 271 (1949) ... 18

Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358

(5th Cir. 1981) .... 4

McMillan v Escambia County, Memo

randum Decision (unreported,

N.D. Fla. 1978) ........ 4,5,6,7,11,

13,14,15,20

McMillan v. Escambia County, 638

F.2d 1239 (5th Cir.

1981 ) ................ 2,5,11 ,13,

15,17,21

Personnel Administrator of Massa

chusetts v. Feeney, 442

U.S. 256 (1979) ............ 19

Page

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973) ......................... 8

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1 973) (jen banc),

aff'd sub nom. East Carroll

Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636

(1976) .................... 3,4,6,7,8

Constitutional Provisions

Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States ... ii,22

Fifteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United

States ..................... ii,21,22

Statutes

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§1973, Section 2 ...... ii,20,21,22

v

No. 80-1946

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1980

CITY OF PENSACOLA, FLORIDA, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

ELMER JENKINS, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States

Court of Appeals For The

Fifth Circuit

MOTION TO AFFIRM

I.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE INSUBSTANTIAL

This case does not present the first

question suggested in the City's Jurisdic

tional Statement, namely, whether present

discriminatory effect, as well as discrimi

2

natory intent, is required to invalidate an

at-large election system. The Court of

Appeals interpreted the rule of City of

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), to be

as follows:

[I]f the purpose of adopting or

operating [the at-large] system is

invidiously to minimize or cancel out

the voting potential of racial minor

ities, and it has that effect, then it

is unconstitutional.

McMillan v. Escambia County, 638 F.2d 1239,

1248 (5th Cir. 1981) (emphasis added).

After concluding that the evidence in this

case fully supported the District Court's

conclusion that Pensacola's at-large system

had a racially discriminatory purpose, the

Court of Appeals then affirmed the judgment

of unconstitutionality "[b]ecause it is

undeniable that the system] ] [has] in

fact had that effect." I^d. (Footnote

omitted.)

3

Since the courts below concluded that

the election system was racially discrimi

natory in both purpose and effect, the

Appellant City's challenge of the decision

cannot ask whether present discriminatory

effect must be shown, but only whether the

lower courts' findings of discriminatory

effect are supported by the evidence.

Moreover, the Jurisdictional Statement

makes it clear that the Appellant proposes

to rehabilitate -- now as a measure of

discriminatory effect rather than intent —

the test of Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d

1 297 (5th Cir. 1 973) (en banc) , af f' d sub

nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v .

Marshall, 424 U.S 636 (1976), which was

discredited by City of Mobile v. Bolden.

The City urges this effect standard un

daunted by the District Court's conclusion

that in this case the black plaintiffs

4

satisfied the Z m_e r test, as well as

the test set out by this Court in Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development

Cor£ 4 2 9 U.S. 252, 266-268 (1977).

Appendix to Appellants' Jurisdictional

Statement 41a (hereinafter cited as

"App."). More particularly, the Appellants

would isolate and elevate to paramount

status as a measure of discriminatory

effect the single Zimmer criterion of local

government unresponsiveness to minority

group interests, citing Lodge v. Buxton,

639 F. 2d 1 358 (5th Cir. 1981), which held

that unresponsiveness was an essential

element of proving invidious _in J: ent..

Appellants' Jurisdictional Statement at

12-13 (hereinafter cited as "J.S.").

This question has been answered in

City of Mobile v. Bolden. While there is

no majority view supporting the decision of

the Court, one thing is certain from the

various Bolden opinions; given a discrimi

5

natory legislative purpose, the unrespon

siveness of local officials is not the

measure of the electoral system's effect.

According to the Bolden plurality, un

responsiveness "is relevant only as the

most tenuous and circumstantial evidence of

the constitutional invalidity of the

electoral system ..." 446 U.S. at 74.

This undermines the utility of unrespon

siveness for proving effect or purpose; if

it tended to prove adverse impact, it would

be relevant as an important "starting

point" for proof of intent. Thus, Bolden

fully vindicates the holding of the Dis

trict Court in the instant case that "[t]he

effect of dilution, however, may exist

apart from the unresponsiveness of politi

cians," App. 41a-42a, and the agreement of

the Court of Appeals that "a slave with a

benevolent master is nonetheless a slave."

638 F.2d at 1249

6

Whatever may ultimately become the

minimum test for adverse effect when

coupled with intent, Bolden certainly says

that an aggregate of the Z immer factors

amply carries this burden. None of the

members of the Bolden Court doubted that

Mobile's at-large elections had been proved

to have an adverse impact on blacks. By

the same token, the findings in the

instant case are more than sufficient:

racially polarized voting and at-large

elections interacting to deny blacks access

to the political processes, past official

racial discrimination that shares respon

sibility for racial polarization and the

defeat of black candidates, majority vote

requirements and numbered places. App.

41a. The District Court thus found that

"these factors show, in the aggregate, that

the voting strength of blacks is effec

7

tively diluted. ..." App. 42a-43a (empha

sis added) .

If this Court should accept Appel

lants' argument that the District Court's

finding of discrimination under the

Z immer analysis is insufficient to prove

discriminatory effect solely because the

single factor of unresponsiveness is

absent, then — and only then — would it

be necessary to consider what constitutes

the minimum requirements for proving

effective dilution. To begin with, there

is a strong suggestion in the Bolden

plurality opinion that legislative intent

should be the sole focus in a dilution case

— that no proof of adverse effect is

required thereafter. See City of Mobile

v. Bolden, supra, 446 U.S. at 90 (Stevens,

J., concurring). But even if actual racial

impact must be shown, "[sjuch a requirement

8

would be far less stringent than the burden

of proof required under the rather rigid

discriminatory-effects test ... in White v .

Regester, [412 U.S. 755 (1973)]." 446 U.S.

at 139 n.39 (Marshall, J., dissenting).

The plurality opinion bears out Justice

Marshall's observation. It infers that,

once a discriminatory purpose has been

established, blacks need prove no more than

that they have not elected representatives

in proportion to their numbers. Td. at 66;

accord, id. at 101 (White, J., dissenting).

The White v. Regester factors, says the

plurality, go far beyond evidence of mere

adverse effect, actually establishing

invidious purpose. Ici. at 69. The "en

hancing" factors of Zimmer, standing alone,

"tend naturally to disadvantage any voting

minority ... Id. at 74.

9

But neither the District Court nor the

Court of Appeals based its conclusion

of effective dilution merely on a measureVof "proportional representation."

The Court of Appeals did not compare

the number of black city council members

with the percentage of blacks in Pensa

cola's population; rather, it based its

finding of effective dilution on the

detailed analysis of election returns

extending over some twenty years, all

indicating that as a direct result of the

at-large system, black candidates were

consistently defeated by a bloc-voting

white majority. This measure of the

racially discriminatory effect of the

at-large plan is a correct one; it depends

*_/ The argument in the Jurisdictional

Statement notwithstanding (we count no less

than four references to the term) , this is

not a "proportional representation" case.

1 0

neither on the concept of proportional

representation nor on an "amorphous"

judicial inquiry into the sociological and

political dynamics of the local community.

The evidence of circumstances leading

up to and surrounding the 1 959 statute

and referendum eliminating the use of

single-member district elections for the

Pensacola City Council make this case a

paradigm of the type of proof called for

by Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at

266-68. If the findings of invidious

intent made by the lower courts here

cannot be affirmed, then Arlington Heights

is, indeed, an illusory and impossible test

of racial discrimination. A_11_ of the

evidentiary elements of invidious intent

discussed in Arlington Heights were found

in the instant case:

(1) Adverse racial impact: the

exclusive use of at-large elections in

Pensacola effectively dilutes black voting

strength. 638 F.2d at 1 248 ; App. 53a.

(2) The historical background of the

1959 change, revealing a series of official

actions taken for invidious purposes: the

official disenfranchisement of a substan

tial majority of black Floridians during

the first half of the twentieth century; a

long-standing preference for a mixture of

single-member district and at-large elec

tions in Pensacola; Pensacola's adoption of

the white primary and Jim Crow ordinances;

and growing apprehension in the 1940's and

1950's about increasing black voter regis

tration. 638 F.2d at 1247; App. 47a.

(3) The sequence of events leading up

to the change: the first black candidate

in living memory almost defeats the white

- 1 1 -

12

mayor of Pensacola in a close single-member

district election in 1955; the City Council

responds in 1956 by gerrymandering more

whites into the threatening black district;

and following other such gerrymander

efforts, the same City Council in 1959

requests the Florida legislature to elimin

ate Pensacola's single-member districts

altogether.

(4) Substantive and procedural

departures: the combination of single

member district and at-large elections had

been satisfactory to Pensacolians for 28

years, when the district elections were

abruptly eliminated by direct state legis

lation, even though the Pensacola City

Charter authorized modification of the

election system without reference to the

legislature by using the more deliberative

process of apportionment of a charter

13

amendment committee by the City Council

followed by a public referendum.

(5) The legislative history: al

though there is no official record of the

debates over the statute, because the

practice in the Florida legislature is not

to record such proceedings, one of the

members of the 1959 Pensacola City Council

admitted that the council had requested

the change to ensure against the possibil

ity of a black person being elected, the

legislator who introduced the bill admitted

that another petitioning council member had

alluded to a desire to avoid "a salt and

pepper council," and the Pensacola news

paper editorialized that the "prime" reason

for the proposed change was to prevent

blacks from being elected. See generally

638 F.2d at 1247-8; App. 47a-48a.

14

The second question presented in the

Jurisdictional Statement urges this Court

to rule that, solely because the District

Court accepted the sponsoring legislator's

personal disavowal of discriminatory

motives, as a matter of constitutional law,

invidious purpose cannot be proved.

Appellant City contends that, even where

the District Court found that the estab

lished practice of the local legislators

was to pass no laws concerning city govern

ment without the unanimous approval and

petition of the city council, App. 48a, the

racial motives of the city council members

may not be considered in the Arlington

Heights analysis. But, in order to agree

with Appellants' argument, this Court would

have to conclude that the lower courts'

reliance on all the other, overwhelming

Arlington Heights evidence was of no avail

and that the District Court and the Court

of Appeals misstated the law by holding

that " [d]iscriminatory intent at any stage

[of the formal or informal legislative

process] infects the entire process." App.

48a n.9, accord, 638 F.2d at 1246 n.14.

Such a result would fundamentally

negate the teaching of Arlington Heights

that " [d]etermining whether invidious

discriminatory purpose was a motivating

factor demands a sensitive inquiry into

such circumstantial and direct evidence of

intent as may be available." 429 U.S. at

266, cited in 638 F.2d at 1 243. If there

is any hope that the inquiry into purpose

or intent can provide a manageable judicial

standard for equal protection cases, and

in particular for racial vote dilution

cases, courts must be permitted to consider

the motives of all persons who exercised

16

substantial influence or control over

the ultimate official decision. If the

inquiry is required to identify and

focus on the motives of the single most

influential actor in the decision-making

process, then federal judges truly will be

enmeshed in the political thicket.

For example, in the instant case the

Appellant City argues that Governor

(then Representative) Askew's motives alone

are relevant, simply because he testified

that he had the power, by informal conven

tion of the local legislative delegation,

to "kill" the City Council's proposed bill.

But the same thing can be said of the other

two members of the Escambia County legisla

tive delegation, and the record says

nothing about their motives in voting

for the election change. Further extending

the City's theory to its logical conclusion

1 7

would require proof of invidious motives on

the part of a majority of the state legis

lators, who have the ultimate power to

overrule even local delegation decisions.

Clearly, Arlington Heights calls for a more

pragmatic consideration of the concept of

legislative purpose, and requires courts

to judge the intent of official actions by

weighing the entire evidentiary record.

As the Court of Appeals said in this

case, "[i]t is not easy for a court in 1981

to decide what motivated people in 1959."

638 F . 2d at 1 248 . Based on all of the

direct and circumstantial evidence, the

Court of Appeals agreed with the District

Court’s finding that " [t]he conclusion of

plaintiffs' expert historian that race was

a concurrent motivating factor in the 1959

change is inescapable. " I_d. Iff a s

Appellants contend, the constitutional

18

inquiry requires the courts to determine

the subjective motives of every one of the

individual legislators capable of altering

the outcome of proposed statutes, then

nothing short of a written statement of

racial intent within the law itself would

suffice. Moreover, acceptance of appel

lants' contention that both courts below

erred in their assessments of evidence

probative of discriminatory purpose would

be contrary to "[this Court's] settled

practice of accepting, absent the most

exceptional circumstances, factual determi

nations in which the district court and the

Court of Appeals have concurred ..."

Branti v. Finkel, 445 U.S 507, 512 n.6

(1980); accord, Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v .

Linde Air Products , 336 U.S. 271, 275

(1949). S e e , e .g ., Columbus Board of

Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 464

(1979).

19

Finally, Appellants argue that the

plaintiffs in a vote dilution case must

prove that the racial motives outweighed

the nonracial motives. They are therefore

asking this Court to reject its formulation

of proof of intent in Personnel Adminis

trator of Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S.

256, 279 (1979):

'Discriminatory purpose' ... implies

that the decisionmaker ... selected

or reaffirmed a particular course of

action at least in part 'because of,'

not merely 'in spite of,' its ad

verse effects upon an identifiable

group.

(Footnote omitted). This formula was

adopted by the Bolden plurality, 446 U.S.

at 71 n. 1 7. Feeney requires more than

lip-service to the usual "good government"

rationales of a "city-wide perspective" and

elimination of ward heeling. Otherwise, no

at-large electoral system could be chal-

The inability orlenged by minorities.

20

refusal of the lawmakers here to justify

how the racial consequences of their

actions were outweighed by the need for a

city-wide perspective supports the trial

judge's conclusion that the "good-govern

ment" rationale was a pretext for discrimi

nation, "at least in part."

II.

THERE ARE ALTERNATIVE STATUTORY AND

CONSTITUTIONAL BASES FOR THE RULING

BELOW

Plaintiffs contended below that §2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§1973, allowed them to sue to enforce

their voting rights and that this right did

not depend upon a finding of purposeful

discrimination. The trial court agreed

that the plaintiffs had proved a violation

of 42 U.S.C. § 1 973 , but did not decide

whether proof of intent was necessary under

that statute. App. 55a. The Court of

21

Appeals disagreed with the District Court's

conclusion that at-large vote dilution

violated the fifteenth amendment and held

that plaintiffs could sue only under the

fourteenth amendment to support such a

claim. 638 F.2d at 1242-3 nn. 8 and 9.

The Court of Appeals rejected the

Voting Rights Act and fifteenth amendment

predicates of the trial court's judgment on

account of the Court of Appeals' adoption,

in toto, of the plurality opinion in City

of Mobile v. Bolden. By concluding that

the evidence of invidious intent in the

adoption of Pensacola's at-large system

satisfied the requirements of Arlington

Heights, the lower courts grounded their

judgments of unconstitutionality on the

single theory that would clearly satisfy a

majority of the members of the Bolden

Court. But there was no majority agreement

22

with the plurality opinion's views of the

Voting Rights Act and fifteenth amendment

causes of action. Consequently, if this

Court were to disapprove the findings of

invidious intent made below, it would then

become necessary for it to reexamine the

difficult statutory and constitutional

questions that were not resolved in Bolden.

In this event, Plaintiffs-Appellees would

contend that at-large election systems

which have a demonstrably discriminatory

impact on a racial minority violate the

fourteenth amendment, the fifteenth amend

ment and §2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, whether or not an invidious racial

purpose could be proved.

CONCLUSION

This Court should decline to note

probable jurisdiction, and, on the merits,

affirm the judgment of the Court of

Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

KENT SPRIGGS

Spriggs & Henderson, P.A.

117 S. Martin Luther

King Jr. Blvd.

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

(904) 224-8701

J.U. BLACKSHER

Counsel of Record LARRY MENEFEE

Blacksher, Menefee &Stein, P.A.

P.O. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

(205) 433-2000

W. EDWARD STILL

Reeves & Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 1st Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 322-6631

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appell

MEILEN PRESS INC — N. Y. C. 219