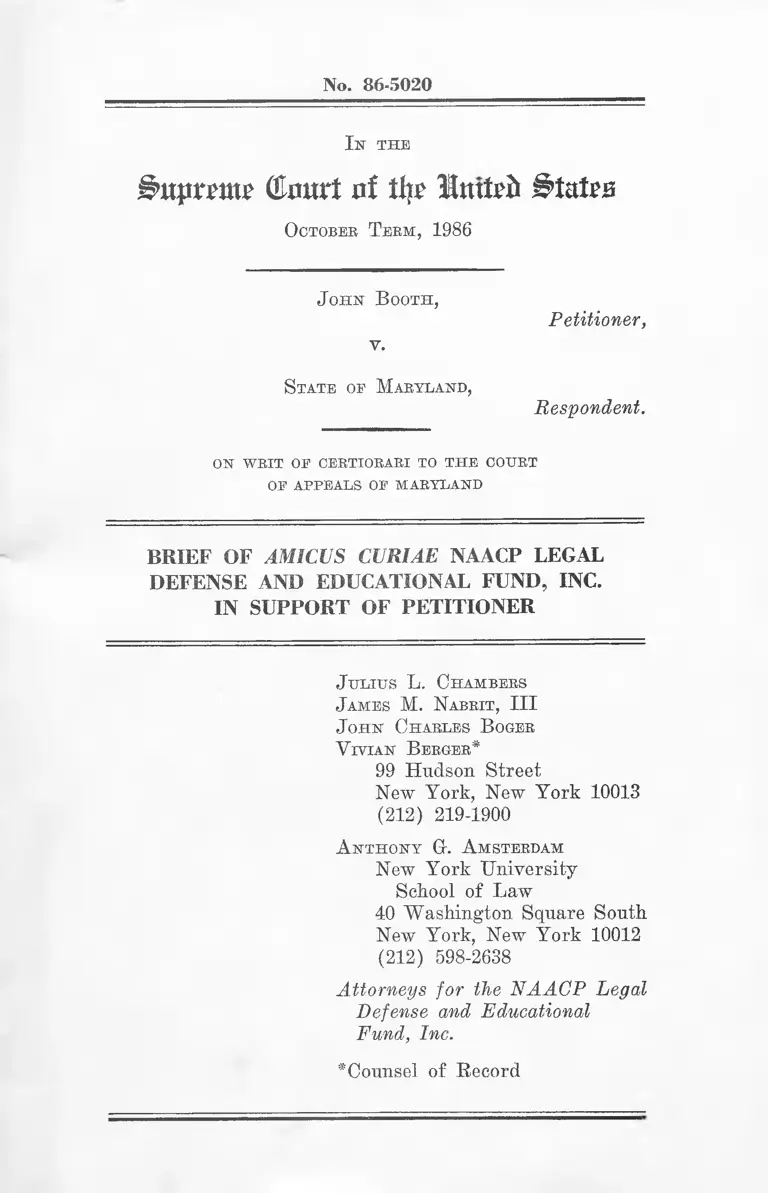

Booth v. Maryland Brief of Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Support of Petitioner

Public Court Documents

December 3, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Booth v. Maryland Brief of Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in Support of Petitioner, 1986. 3e02b71c-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cf4648bb-e3b2-4e8f-b176-762eff3c1eb5/booth-v-maryland-brief-of-amicus-curiae-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-in-support-of-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 86-5020

I n the

iwprpmp Qkutrt nt % Itutpib States

October Term, 1986

J ohn B ooth,

v.

State op Maryland,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

O N W R IT OP CERTIO RA RI TO T H E COU RT

OP A PPEA L S OP M A RYLAND

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

J ulius L. Chambers

J ames M. Nabrit, III

J ohn Charles Boger

V ivian Berger*

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

A nthony 0 . Amsterdam

New York University

School of Law

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

(212) 598-2638

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

^Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does the admission at a penalty

trial of so-called victim impact evidence

— which is by nature inflammatory,

irrelevant to any legitimate capital

sentencing purpose, and conducive to death

sentences imposed on the basis of race,

social class, and other impermissible

factors — violate the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments?

2. Did the introduction at

petitioner's sentencing of a "Victim Impact

Statement," as mandated under Maryland law,

violate this petitioner's rights under the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented .............. i

Table of Authorities ............. iv

Statement of Interest of

Amicus Curiae ................. 1

Summary of Argument .............. 3

Argument ......................... 4

The Use of "Victim

Impact" Evidence at the

Penalty Phase of a

Capital Trial, As Man

dated Under Maryland

Law, Injects Irrational,

Arbitrary and Imper

missible Considerations

into the Life-or-Death

Decision, and Is

Unconstitutional ....... 4

1. Much of the Matter

Required by Maryland

Law to Be Included

in Victim Impact

Statements Bears No

Conceivable Rela

tionship to the

Legitimate Ends of

Capital Sentencing .. 7

2. By Deflecting the

Jury From Its Proper

Task of Objectively

Considering the Par

ticularized Circum

stances of the

Individual Offender

ii

and Crime, Introduc

tion of Victim Impact

Statements at the

Penalty Phase En

courages Arbitrary

Sentences of Death .. 22

3. Admission of Victim

Impact Evidence Would

Necessitate Admission

of Expansive Proof

of a Similar Type,

Offered On Behalf of

Defendants .... . 31

4. Victim Impact State

ments Invite the Jury

to Impose Sentences

of Death for Consti

tutionally Impermis

sible Reasons ....... 36

II. The Admission at Peti

tioner's Penalty Trial

of a Long, Irrelevant,

Inflammatory Victim

Impact Statement Vio

lated Petitioner's

Rights Under the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments 40

Conclusion ....................... 46

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38

(1980) ......................... 2

Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880

(1983) ......................... 2

Booth v. State, 306 Md. 172,

507 A.2d 1098 (1986) .... 13 n.7,34,37,38

n.18,41 n.20,45

Brooks v. Kemp, 762 F .2d 1383

(11th Cir. 1985) (en banc),

vacated, ___ U . S . ___,

92 L.Ed. 2d 732 (1986) ......... 38,39

Caldwell v. Mississippi, ___ U.S.

___, 86 L.Ed. 2d 231 (1985) .... 5

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992

( 1983) ................. 6 r.. 2,15, 16,17,23

Chambers v. Mississippi,

410 U.S. 284 (1973) ............ 32

Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584

(1977) ......................... 22

Coppola v. Commonwealth,

220 Va. 243, 257 S.E. 2d 797

(1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S.

1103 ( 1980) .................... 35 n. 17

Eddings v. Oklahoma,

455 U.S. 104 (1982) ............ 21

Enmund v. Florida,

458 U.S. 782 (1982) ....... 2,15,16,21,22

Estelle v. Smith,

451 U.S. 454 (1981) ............ 2

IV

20

Evans v. State, 422 So. 2d 737

(Miss. 1982), cert, denied, 461

U.S. 939 (1983) ...............

Fisher v. State, 482 So. 2d 203

(Miss. 1985} .................. .

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

( 1972) ...................... 2,4,2

Fuselier v. State, 468 So. 2d 45

(Miss. 1985) ....................

Gardner v. Florida,

430 U.S. 349 (1977) ....22 n.12,23

Godfrey v. Georgia,

446 U.S. 420 (1980) ............

Grant v. State, 703 P .2d 943

(Okla. Crim. App. 1985) .......

Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95

(1979) ................. ........

Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153 (1976) ..2,4,15,17.n .

Henderson v. State, 234 Ga. 827,

218 S.E. 2d 612 (1975) ........

Ice v. Commonwealth, 667 S.W. 2d

671 (Ky.), cert, denied,

469 U.S. 861 (1984) ............

Lockett v. Ohio,

438 U.S. 586 (1978) .... 16,27-28

Lodowski v. State, 302 Md. 691,

490 A.2d 1228 (1985), vacated,

___ U.S. ___, 89 L .Ed.2d 711

(1986) ..... 5 n.1,9&.n.4,13-14.&

19,24,25

29

1,24,36

26 n.13

,27,30,

33 n.16

22,23

29,30

32

8,23,24

28,29

26

n.14,30

n.7,18,

,42 n .21

v

Moore v. Zant, 722 F .2d 640

(11th Cir. 1983), reh'g

en banc granted, 738 F .2d 1126

(11th Cir. 1984) .11,14,19&.n .9,20& n.10,

35 n.17,36,38 n.19,39

Muckle v. State, 233 Ga. 337,

211 S .E .2d 361 (1974) --- 11 n. 5

People v. Bartall, 98 111. 2d 294,

456 N.E. 2d 59 (1983) ......... 29

People v. Brown, 40 Cal. 3d 512,

709 P. 2d 440, 220 Cal. Rptr.

637 (1985), cert, granted, ___

U.S. , 90 L.Ed. 2d 717

(1986T~T...................... . n.14

People v. Easley, 34 Cal. 3d 858,

671 P .2d 813, 196 Cal. Rptr. 309

(1983) ......................... 27 n -14

People v. Free, 94 111. 2d 378,

447 N.E.2d 218, cert, denied,

464 U.S. 865 (1983) .11 n.5,18,25-26 n.13

People v. Holman, 103 111.2d 133,

469 N.W.2d 119 (1984), cert.

denied, 469 U.S. 1220 (1985) .18,19,26,39

People v. Lanphear, 36 Cal.3d 163,

680 P .2d 1081, 203 Cal. Rptr.

122 (1984) ..................... 27 n -14

People v. Levitt, 156 Cal. App.

3d 500, 203 Cal. Rptr. 276

(1984) ...11 n.5 ,1 7 ,1 8 ,20 n.10,28,30 n.15

People v. Love, 53 Cal.2d 843, 350

P .2d 705, 3 Cal.Rptr. 665

(I960) ................ .....21 n.11,23,24

People v. Ramirez, 98 111.2d 439,

457 N.E. 2d 31 (1983) ......... 25 n.13

vi

Skipper v. South Carolina,

_____ U.s. ... , 90 L.Ed. 2d 1

"( 1986) .......27 n . 14 , S2-33& n. 16,35 n.17

State v. Gaskins, 284 S.C. 105,

326 S.E. 2d 132 (1985) ........ 35 n. 17

State v. Reeves, 216 Neb. 206,

344 N.W. 2d 433 (1984) ......... 10 n.4

State v. Rushing, 464 So.2d 268

(La. 1985), cert, denied,

U.S. ___, 90 L.Ed. 2d 703

(1986) ........................ . n.22

State v. Sprake, 637 S .W .2d 724

(Mo. Ct. App. 1982) ............ 29

State v. Williams, 217 Neb. 539,

352 N.W.2d 538 (1984) ........ 9-10 & n.4

Tobler v. State, 688 P.2d 350

(Okla. Crim. App. 1984) 14,26

Turner v. Murray, ___ U.S. ___,

90 L.Ed. 2d 27 (1986) ..... 5,6.n .2,30,39

Vela v. Estelle, 708 F.2d. 954

(5th Cir. 1983), cert, denied,

464 U.S. 1053 (1984) 26,27

Welty v. State, 402 So.2d 1159,

(Fla. 1981) 29

Wiley v. State, 484 So.2d 339

(Miss. 1986) 26

Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510 (1968) 2

Woodson v. North Carolina,

428 U.S. 280 (1976) .......... 4,6 n.2,15

vii

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862

(1983) .................... 16,17,21,23,36

Statutes

Fed. R. Crim. P. 32(c) .......... 6 n.2

Fed. R. Evid. 404(a) ............. 19 n.9

L.S.A. Code Crim Pro.,

art. 875 (A), (B) (Supp. 1986) . 9 n.4

Md. Code, art. 27, section 413(c)

(iv)(Cum. Supp. 1984)........... 42& n.21

Md. Code, art. 41,

section 124 (Cum. Supp. 1984) ..7-8& n.3,

9 n.4,10,11,18

Md. Rule 4-343 (d ) ................ 34

Neb. Rev. Stat. section 29-2261

( 1985) 9 n.4

O.C.G.S. sections 17-10-1.1,

17-10-1.2 (Supp. 1986) 9 n.4

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 22,

section 982 (1986) 9 n.4

Public Law No. 97-291,

96 Stat. 1248 (1982) 6 n.2

S.C. Code Ann. section 16~3~1550(A)

( 1985) 9 n.4

Other Authorities

Henderson, The Wrongs of Victim's

Rights, 37 Stan. L. Rev. 937

vi i i

No. 86-5020

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1986

JOHN BOOTH,

Petitioner,

v .

STATE OF MARYLAND,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

COURT OF APPEALS OF MARYLAND

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a non-profit corporation

established to assist black citizens in

securing their constitutional rights. In

1967, it undertook to represent indigent

death-sentenced prisoners for whom adequate

representation could not otherwise be

found. It has frequently represented such

prisoners before this Court. E.g., Furman

v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972); Estelle v.

Smith, 451 U.S. 454 (1981); Enmund v ■

Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982). The Fund has

also appeared before this Court as amicus

curiae in capital cases. E.g., Witherspoon

v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968); Gregg v.

Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976); Adams v.

Texas, 448 U.S. 38 (1980); Barefoot v.

Estelle, 463 U.S. 880 (1983).

The Legal Defense Fund currently

represents a substantial number of indigent

condemned prisoners in states in the Fourth

Circuit and elsewhere, whose cases are at

various stages following affirmance of

conviction and sentence by the state

appellate courts. The Fund is also often

called on, and tries to the extent of its

capacities, to provide consultative

assistance to attorneys representing other

capital defendants across the nation.

2

The issues presented by this case are of

utmost concern to death-sentenced prisoners

throughout the country, including many

represented by the Fund. Both petitioner

and respondent have consented to the filing

of this amicus curiae brief.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The admission of victim impact

evidence at penalty trials violates the

Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment rights of

defendants on trial for their lives on a

number of grounds. For one thing, its use

advances no legitimate goal of capital

sentencing. Further, because it is so

inflammatory, it deflects the jurors from

rational consideration of the life-or-death

decision. Toleration of this evidence

would, moreover, compel admission of wide-

ranging proof of a similar nature offered

by defendants, and thereby threaten the

entire structure of death-sentencing

3

jurisprudence the Court has erected.

Finally, victim impact evidence encourages

jurors to base determinations of death on

invidious, impermissible factors such as

race and social class.

II. in this case, the "Victim Impact

Statement" admitted at the penalty trial

was so inflammatory and irrelevant as

clearly to violate petitioner's rights

under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.

ARGUMENT

I .

THE USE OF "VICTIM IMPACT" EVIDENCE AT

THE PENALTY PHASE OF A CAPITAL TRIAL,

AS MANDATED UNDER MARYLAND LAW, INJECTS

IRRATIONAL, ARBITRARY AND IMPERMISSIBLE

CONSIDERATIONS INTO THE LIFE-OR-DEATH

DECISION, AND IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL._____

Both in ushering out the old era

of capital punishment, Furman v ..Georgia,,

40S U.S. 238 (1972), and in inaugurating

the new, see, e.g., Gr egg_v^_G eonrgia, 428

U.S. 153 (1976); Woodson v . North Carolina,

428 U.S. 280 (1976), the Court announced a

4

strong commitment to eradicating arbitrary

and invidious influences on death-penalty

determinations. That commitment persists

unabated. As recently as last Term's

decision in Turner v. Murray, __ U.S.__, 90

L .Ed.2d 27 (1986), the Court reaffirmed its

obligation to strike down death sentences

imposed under circumstances that "'created

an unacceptable risk'" of arbitrariness,

caprice or mistake. Id. at 36, quoting

Caldwell v. Mississippi, ___ U . S . ___, 86

L .Ed.2d 231, 248-49 (1985)(0'Connor, J.,

concurring in part and concurring in the

judgment).

So-called victim impact evidence,

which in capital penalty proceedings mainly

deals with effects of the crime on the

victim's family1, offends this principle

1Lodowski v. State, 302 Md. 691, 760-

61, 490 A.2d 1228, 1263 (1985) (Cole, J.,

concurring), vacated on other grounds,__

U.S.__, 89 L.Ed. 2d 711 (1986). More

detailed discussions of such evidence

appear at pp. 40-45, infra.

5

for four interrelated reasons,2 First, such

evidence intrudes into the penalty decision

considerations that have no rational

bearing on any legitimate aim of capital

sentencing. Second, this proof is highly

emotional and inflammatory, subverting the

reasoned and objective inquiry which this

Court has required to guide and regularize

the choice between death and lesser

punishments. Third, victim impact evidence

cannot conceivably be received without

opening the door to proof of a similar

^The Court need not now determine the

appropriate role, if any, of the victim or

the victim's family at various stages of

ordinary trials. See generally Henderson,

The Wrong’s of Victim's Rights, 37 Stan.

ITTr evT~9 3 7 ( 1985); see , e . g ._j_ Pub. L. No.

97-291, 96 Stat. 1248 (1 9 8 2 )(amending Fed.

R. Crim. P. 32(c)(2)). For, as the Court

has often recognized; "' ••• [Tjhe

qualitative difference of death from all

other punishments requires a

correspondingly greater degree of scrutiny

of the capital sentencing determination.'"

Turner, U.S. at 90 L.Ed.2d at 36,

quoting California v. RamosL 463 U.S. 992,

998-99 (1983). See also Woodson v. North

Carolina, 428 U.S. at 303-05 (opinion of

Stewart, Powell and Stevens, JJ.).

6

nature in rebuttal or in mitigation,

further upsetting the delicate balance that

the Court has painstakingly achieved in

this area. Fourth, the evidence invites

the jury to impose death sentences on the

basis of race, class and other clearly

impermissible grounds.

1. Much of the Matter Required by

Maryland Law to Be Included in Victim

Impact Statements Bears No Conceivable

Relationship to the Legitimate Ends of

Capital Sentencing.__________________ ___

Article 41, section 124 of the Maryland

Code, set out in pertinent part in the

margin,3 provides for a Victim Impact

3Section 124(c)(3), (4) and (d) read

as follows (emphasis added):

(c ) ...

(3) A victim impact statement

shall:

(i) Identify the victim of the

offense;

(ii) Itemize any economic loss

suffered by the victim as a

result of the offense;

(iii) Identify any physical

injury suffered by the victim as

a result of the offense along

7

Statement ("VIS") to be encompassed in the

presentence investigation. Originally

enacted in 1982, the law did not apply at

first to felonies that resulted in death.

with its seriousness and

permanence;

(iv) Describe any change in the

victim's personal welfare or

familial relationships as a

result of the offense;

(v) Identify any request for

psychological services initiated

by the victim or the victim's

family as a result of the

offense; and

(vi) Contain any other information

related to the impact of the offense

upon the victim or the victim’s family

that the court requires.

(4) If the victim is deceased,

under a mental, physical, or legal

disability, or otherwise unable to

provide the information required

under this section, the

information__may be obtained from

the_____personal representative,

guardian, or_committee,__or__such

family members as may be necessary.

(d ) In any case in which the death

penalty is__requested under Article

27, section 412, a presentence

investigation, including a victim

impact____ statement, shall____ be

completed by the Division of Parole

and Probation,__ and shall__be

considered__by the court or .jury

before whom the separate sentencing

proceeding __is___conducted under

Article 27, §413.

8

See Lodowski v. State, 302 Md. at 736-37 &

n .4, 490 A.2d at 1251-52; id., 302 Md. at

760-63 & n .4, 490 A.2d at 1263-65 & n.4

(Cole, J., concurring) (discussing

legislative history). The next year, the

statute was amended, in haste and

apparently without much thought, to require

preparation and consideration by the

sentencing body of a VIS in any case where

the death penalty is requested (but not in

other murder prosecutions). 4

4About 30 states have recently passed

statutes authorizing victim input, in the

form of statements or otherwise, in

sentencing proceedings. Lodowski v. State,

302 Md. at 754-55 & n.3, ~490 A.2d at 1260

n.3 (Cole, J. concurring)(listing

statutes). Most of these jurisdictions

have also enacted capital punishment

provisions. A number of states with both

victim impact and death-penalty legislation

expressly exclude capital sentencing from

the ambit of the former statutes. See,

e .q ,, L.S.A. Code Crim. Pro., art.

875(A),(B)(1984)(La.); O.C.G.S. sections

17-10-1.1, 17-10-1.2 (Supp. 1986)(Ga.);

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 22, section

982(1986); S.C. Code Ann. section 16-3-

1550(A) (1985); but see Md. Code, art. 41,

section 124 (Cum Supp. 1984); Neb. Rev.

Stat. section 29-2261 (1985); State__v^

Williams, 217 Neb. 539, 541-42, 352 N.W.2d

9

Section 124 now calls for a VIS

describing specific harms to the victim:

economic, physical and emotional. The

statute also expressly mandates inclusion

in the statement of certain information

regarding the family. For instance, the

VIS must "[djescribe any change in the

victim's personal welfare or__L^ i lial

relationships" and "[identify any request

for psychological services initiated by the

victim or the victim's family that the

court requires." Md. Code, art. 41, section

124(c)(3)(iv), (v), (vi)(emphasis added).

Where the victim is deceased, a separate

subheading explicitly provides for the

needed data to be gotten "from the

personal representative, guardian, or

committee, or such family members as may be

538, 540-41 (1984) (presentence report

admissible at penalty trial) ; State— ,v_i.

Reeves, 216 Neb. 206, 221, 344 N.W.2d

433, 444 (1984)(per curiam)(same). See

generally Henderson, supra note 2, at 986-

87 .

10

necessary. Id. (c )(4){emphasis added).

See generally supra note 3. If one

considers how, practically speaking, such a

statute applies in a capital murder case,

it is readily apparent why admission of a

VIS or similar impact evidence5 at

sentencing is "fraught with constitutional

danger." See Moore v. Zant, 72 2 F .2d 640,

646 (11th Cir. 1983),reh'g en banc granted,

738 F .2d 1126 (11th Cir. 1984).

Every murder trial includes, as part of

the prosecution's case, the fact that a

particular victim has died and the extent

5Because victim impact legislation is

of recent origin, see supra note 4, the

statutes themselves have generated few

reported cases Even in the absence of

statutes, however, proof of this type has

at times been offered in capital and non

capital trials, and courts have passed upon

its propriety. See, e .g ., People v. Free,

94 111.2d 378, 447 N.E. 2d 218, cert.

denied, 464 U.S. 865 (1983); Muckle v.

State, 233 Ga. 337, 211 S.E.2d 361 (1974);

People v. Levitt, 156 Cal.App.3d 500, 203

Cal.Rptr. 276 (1984). Examples of

experience with similar evidence elsewhere

illuminate the problems of the Maryland

law, and are accordingly included here.

11

of his or her injuries. The killing is an

element of the crime charged, and proof of

injuries is typically relevant to intent

and other issues of mens rea as well as to

the means employed.® Further, special

facts about the victim which aggravate the

crime when known to the killer — such as

the victim's status as a policeman on duty

or vulnerable child or elderly person-

will naturally emerge during trial; they

will be highlighted in the penalty phase

where a state has chosen to make them

statutory aggravating circumstances. If a

VIS is to have any significance, it would

rest on the contents of the statement over

and above all of this information. The

matter, not bearing on the crime or the

defendant's mental state in relation to it,

is, of course, what this case is about.

6E.g., certain kinds of wounds,

consistent with the close-range firing of a

gun, would tend not only to prove the

instrumentality of death but also,

ordinarily, intent to kill.

12

Typically, those parts of the VIS that

go beyond the evidence at trial portray

grief--stricken relatives expressing their

extreme sorrow, sense of loss, and anger

over their bereavement — often in highly

emotional terms. Sometimes, these

survivors call, explicitly or implicitly

(as here), for the death of the

perpetrator, or announce their impatience

with procedures and delays in the courts.

They relate somatic and psychological

symptoms of distress attributed by them to

the murder, such as physical ailments,

effects on pregnancy, lack of appetite,

sleeplessness, nightmares, fears and

depression. Frequently, too, the adult

survivors describe these conditions in

their children.7

7Samples of all the varieties of proof

detailed in this paragraph and the next

appear both in Booth, 306 Md. 172, 234-39,

507 A.2d 1098, 1130-33 (1986), and in

Maryland's leading case on victim impact

evidence, Lodowski v. State, 302 Md. at

764-72, 780-84, 490 A .2d at 1265-70, 1273-

13

Insofar as the VIS recounts matter

pertaining to the actual victim, that too,

ordinarily, has no bearing on the

circumstances of the crime or the

defendant. Frequently, (as here), family

members were not present at the time of the

killing and have no relationship with the

killer. Hence, they tend to dwell upon

general good character traits and

achievements of the deceased, see , e .q .,

Moore_v. Zant, supra (victim's education

and work habits), and recollections of

"happier days." See, e .g ., Lodowski, 302

Md. at 770 n .8, 490 A.2d at 1268 n.8 (Cole,

J., concurring)(topic heading in victim's

mother's VIS was entitled "'Our Past Happy

Days'"); Tobler v. State, 688 P.2d 350

(Okla. Crim. App. 1984)(surprise Mother's

Day family reunion involving the victim).

76 (Cole, J. concurring). See also infra at

40-45; Petitioner's Brief at ___ (Statement

of the Case).

14

Such proof at a penalty trial fails to

contribute "measurably" — or at all — to

the recognized aims of capital sentencing,

which, as the Court has often stated, are

mainly retribution and general deterrence.

See, e .q ■, Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782,

798 (1982); Greacr v. Georgia, 428 U . S . at

183 (opinion of Stewart, Powell and

Stevens, JJ.); see also id. at 233

(Marshall, J., dissenting). These aims

explain why capital punishment decisions

since Gregg constantly recur to the theme

of "personal responsibility and moral

guilt," Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. at 801,

and hence to the constitutional requirement

that the 1 ife-or-death decision focus on

"relevant facets of the character and

record of the individual offender” and "the

circumstances of the particular offense.

Id. at 798; Woodson v. North Carolina ̂428

U.S. at 304 (opinion of Stewart, Powell and

Stevens, JJ. ) . See, e . g , , Ca 1 i tor n i a . v_._

15

Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1006; Zant v , Stephens,

462 U.S. 862, 879 (1983); Lockett v. Ohio,

438 U.S. 586, 604 (1978) (plurality

opinion); Gregg, 428 U.S. at 189 (opinion

of Stewart, Powell and Stevens, JJ.). For

Enmund v. Florida, supra, in barring the

infliction of death upon a vicarious felony

murderer who did not intend any killing to

occur, made clear that both the retributive

and the deterrent efficacy of capital

punishment depend critically on the degree

of a defendant's culpability and, above

all, his intent -- considerations built

into the death-selection standard revolving

about the crime and the criminal. See id.,

458 U.S. at 799-801. Executing a defendant

on the basis of results over which he had

no control and which he did not contemplate

neither "educates" future offenders nor

16

constitutes "just deserts" for the actions

of this particular offender.8

Unintended physical, emotional and

psychological after-effects on relatives do

not increase the moral blameworthiness of

the killer beyond the onus he already bears

for committing the murder, and are

"constitutionally irrelevant." See

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1001-02

(footnote omitted); Zant v. Stephens, 462

U.S. at 885. Since "the fact that a

victim's family is irredeemably bereaved

can be attributable to no act of will of

the defendant other than" the killing,

meting out death on account of "fortuitous

circumstances" like "the composition of the

®Even if specific deterrence or

incapacitation of the killer (preventing

his commission of further crimes) were

thought to justify capital punishment, cf.

Gregg, 428 U.S. at 183 n.28 (opinion of

Stewart, Powell and Stevens, JJ.) (taking

no position on the question), achievement

of these aims, too, would involve

assessment of factors relating to the crime

or the criminal.

17

Vk W s" fafnilyi Ptc>pU (/, , I S~C

Cal. App.3d at 516-17, 203 Cal. Rptr. at

287-88, or survivors' need for

"psychological services," Lodowski, 302 Md.

at 764 n .6, 490 A.2d at 1265 n.6, 1267

(Cole, J., concurring); see Md. Code, art.

41, section 124(c)(3)(v), does not further

deterrence or retribution. Indeed:

It would be difficult to find

anything less relevant to the

circumstances of this offense or

the character of this defendant

than testimony concerning the

reactions of family members of his

unfortunate victims. Their

reaction was not to the nature of

his crime but to the fact that the

crimes happened.

People v. Free, 94 111. 2d at 436, 447

N .E .2d at 246 (Simon, J., concurring in

part and dissenting in part). Similarly,

proof of the victim's sterling character

ordinarily has no legitimate place at a

capital trial and serves only to inflame

the jury. See, e.q.. People v. Holman, 103

111.2d 133, 166-67, 469 N.E. 2d 119, 134-

18

35 (1984), cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1220

(1985).9

In Lodowski, on which the Maryland

Court of Appeals relied in Booth, the

majority cursorily equated victim impact

evidence with the "circumstances

surrounding the crime" and therefore deemed

it admissible. 302 Md. at 741-42, 490 A.2d

at 1254. This argument is wholly

unpersuasive. Lodowski, 302 Md. at 774, 490

A.2d at 1270 (Cole, J., concurring). Cf.

Moore v. Zant,' 722 F . 2d at 653 n.3

(Kravitch, J., concurring in part and

9 In certain limited situations, facts

concerning the victim's character may be

relevant to guilt or innocence, or to the

degree of the defendant's personal

culpability, and hence admissible at

capital trials as at others. See generally

Fed. R. Evid. 404(a )(2)(permissible for

state to show peaceable nature of victim to

rebut evidence offered by defendant to

prove victim was first aggressor). Compare

Moore v. Zant, 722 F.2d at 645 (victim's

character bore on existence of an

aggravating circumstance) with__id._ at 651

(Kravitch, J., concurring and dissenting)

(contra).

19

dissenting in part)("pure sophistry to

subsume victim's "positive attributes"

under "'circumstances of the crime'").10

On the one hand, to the extent that after

effects are idiosyncratic, like the

blighting influence on a granddaughter's

wedding of the murder involved in this case

(JA ___), such an expansive conception of

"crime" suggests no principled outer limits

germane to culpability. C_f. Evans_v .

State, 422 So.2d 737, 743-44 (Miss.

1982)(error in admitting proof of victim's

wife's pregnancy, unknown to defendant, at

capital sentencing was cured by

instruction). On the other hand, as to

predictable effects — the likelihood, for

10By contrast, aggravating

circumstances such as killing a victim who

is known to be an on-duty police officer or

especially vulnerable, see supra at 12,

genuinely relate to the nature of the

offense. See Moore v . Zant, 722 F .2d at

652 n.2 (Kravitch, J., concurring in part

and dissenting in part); People v . Levitt,

156 Cal. App. 3d at 516-17, 203 Cal. Rptr.

at 287-88.

20

instance, that someone will mourn the

victim's loss — their very generality

defeats the goal of individualization in

sentencing. See, e.q., Zant v. Stephens,

462 U.S. at 879; Eddinqs v. Oklahoma, 455

U.S. 104, 110-12 (1982). In any event,

Enmund made clear that the death penalty

cannot be grounded on broad notions of

responsibility for all foreseeable results

of one's acts:11 death imposed on such a

11A pre-Furman state court decision,

People v. Love, 53 Cal.2d 843, 350 P.2d

705, 3 Cal. Rptr. 665 (1960)(Traynor,

CJ.), is very instructive in this regard.

There, the court vacated a capital sentence

because the state had presented proof of

the victim's extreme pain, in the absence

of any showing that the killer had intended

to make her suffer when he shot her fatally

at point-blank range. Operating under a

system where (unlike now) the jury

possessed "complete discretion" to assess

sentence, and conceding that "retribution

may be a proper [sentencing]

consideration," the court nonetheless

expressed strong doubt "that the penalty

should be adjusted to the evil done without

reference to the intent of the evildoer."

53 Cal.2d at 856-57 & n.3, 350 P.2d at 712-

13 & n.3, 3 Cal. Rptr. at 672-73 & n.3.

21

basisl2 amounts to "'nothing more than the

purposeless and needless imposition of pain

and suffering'" and thus to

"unconstitutional punishment." See.Enmund,

458 U.S. at 798, quoting Coker.v . G eo rqia,

433 U.S. 584, 592 (1977).

2. By Deflecting the Jury From Its

Proper Task of Objectively Considering

the Particularized Circumstances of the

Individual Offender and Crime, Intro

duction of Victim Impact Statements at

the Penalty Phase Encourages Arbitrary

Sentences of Death._____________________

If a state wishes to authorize capital

punishment, it "must channel the

sentencer's discretion by 'clear and

objective standards' that provide 'specific

and detailed guidance,' and that 'make

rationally reviewable the process for

imposing a sentence of death. Godfrey—v_.

12cf. Gardner_v. Florida, 430 U.S.

349, 359~(1977) : "If, as the State argues,

it is important to use such information in

the sentencing process, we must assume that

in some cases it will be decisive in the

[sentencer’s] choice between a life

sentence and a death sentence."

22

446 U. S . 420,Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 428 (1980)

(plurality opinion) (citations omitted).

Although the jury should have as much

relevant data as possible to inform its

choice, Gregg, 428 U.S. at 204 (opinion of

Stewart, Powell and Stevens, JJ.); see Zant

v. Stephens, 462 U.S. at 878, "[i]t would

be erroneous to suggest that the Court has

imposed no substantive limitations on the

particular factors that a capital

sentencing jury may consider in determining

whether death is appropriate." California

v . Ramos, 463 U.S. at 1000. Critically,

evidence that introduces arbitrary

variables into the life-or-death decision

affronts the central constitutional tenet

that a capital sentence must be "'based on

reason1" -- in appearance and reality—

"rather than caprice or emotion." Zant v.

Stephens, 462 U.S. at 885, quoting Gardner

v. Florida, 430 U.S. at 358. See also

People v. Love, 53 Cal. 2d at 856, 350 P .2d

23

at 713, 3 Cal. Rptr. at 673 (pre-Furman

case).

Because Victim Impact Statements and

similar forms of evidence virtually invite

jurors to sentence on the basis of

"'passion, prejudice or ... other arbitrary

factor[s]'," no civilized system should

sanction their use at the penalty phase of

capital trials. Cf. Gregg, 428 U.S. at 166-

67, 198 (opinion of Stewart, Powell and

Stevens, JJ.)(upholding Georgia's capital

statutes in part because appellate review

minimized the influence of these factors).

Judge Cole, the dissenter on this point in

Booth, captured the essence of the dangers

posed to rational sentencing by such

innately inflammatory evidence in his

concurrence in Lodowski:

In my view, the only

purpose in allowing members of

the victim's family in a

capital sentencing proceeding

to vent their passions and

express their grief, as in

this case, is to exacerbate

the aggravating circumstances

24

established by the

prosecution. These

demonstrations are arbitrary

and capricious and create a

frenzied environment for the

defendant. How can he

challenge any testimony that

expresses bereavement,

religious harm, or infant

sorrow?

Id., 302 Md. at 786, 490 A.2d at 1276-77.13

130pinions in several capital cases

from other jurisdictions articulate

compatible views. See, e.q,, People v .

Ramirez, 98 111. 2d 439, 453, 457 N.E.2d 31,’

37 (1983)(citation omitted):

"[Ejvidence that a murder

victim has left a spouse

or children is

inadmissible since it

does not enlighten the

trier of fact as to the

guilt or innocence of the

defendant or the

punishment he should

receive, but only serves

to prejudice and inflame

the jury."

See also People v. Free, 94 111.2d at 436,

447 N.E.2d at 246 (Simon, J., concurring in

part and dissenting in part):

An emotional rendition of

the grief of a victim's

family, while understand

able, can only distract

the jury from its weigh

ing of the aggravating

and mitigating factors

25

Several states have apparently

recognized these risks, and responded to

them sensitively, by exempting capital

penalty trials from the requirements of

victim input laws. See supra note 4. In

the absence of governing statutes too,

courts have disapproved the use in capital

proceedings of testimony designed mainly to

create sympathy for the victim or his or

her family, and simultaneously to generate

hatred toward the defendant. See, e .g ■,

People v._Holman, 103 111.2d at 166-67, 469

N .E .2d at 134-35; Ice v. Commonwealth, 667

S .W .2d 671, 675-76 (Ky.), cert, denied, 469

U.S. 861 (1984); Wiley v. State, 464 So.2d

339, 348 (Miss. 1986); Tobler v. State, 688

peculiar to the defendant

and his crime. Such tes

timony is always inflam

matory .

Cf. Fuselier v. State, 468 So.2d 45 (Miss.

1985)(reversal of conviction and death

sentence because victim's daughter was

permitted to sit near the prosecutor and

openly displayed emotion).

26

P •2d at 353-54; cf. Vela__v. Estelle, 708

F • 2d 954, 964-65 (5th Cir. 1983)(because of

counsel s ineffectiveness, jury had been

encouraged "to set punishment based on the

goodness of the murder victim"), cert.

denied, 464 U.S. 1053 (1984).

Such rulings, whether or not expressly

premised on the Eighth Amendment,

effectuate its mandate to avert the risk of

death sentences based on "caprice or

emotion." See Gardner v, Florida, 430 U.S.

at 358.14 They are bolstered by an

14This mandate in no way conflicts

with the defendant's position in People v.

Brown, 40 Cal.3d 512, 709 P.2d~440, 220

Cal. Rptr. 637 (1985), cert. granted,

U-S. __, 90 L.Ed.2d 717 (1986), challenging

a penalty-phase instruction that the jury

should not be swayed by sympathy. The

California Supreme Court had previously

held that a jury may not rely upon

factually untethered sympathy -- i.e .,

sympathy not based on the evidence. People

v.. Lanphear, 36 Cal. 3d 163, 168 n. 1, 680

P-2d 1081, 1084 n. 1, 203 Cal. Rptr. 122,

125 n.l (1984); see People v. Easley, 34

Cal. 3d 858, 876 671 P.2d'813," 824, 196

Cal. Rptr. 309, 320 (1983). In Brown, the

defendant produced substantial mitigating

evidence relating to his character and

background, as he was clearly entitled to

27

additional line of precedent that holds

inadmissible victim-character or

generalized victim-sympathy proof -- as

irrelevant or overly inflammatory -- even

without regard to the special

considerations obtaining in capital

sentencing proceedings. See, e .g ., People

v. Levitt, 156 Cal. App.3d at 517, 203 Cal.

Rptr. at 288 (family's bereavement

irrelevant to sentence of a defendant

convicted of manslaughter); Henderson v.

State, 234 Ga. 827, 828, 218 S.E.2d 612,

614 (1975)(generally, murder victim's

do (see, e .g ., Skipper v. South Carolina,

U.S. __", 90 L . Ed. 2d 1 (1986); Lockett v.

Ohio, supra); the sole issue dividing the

parties is whether the no-sympathy

instruction foreclosed the jurors'

consideration of this evidence, whose

relevance no one disputes. See Brief for

Respondent in People v. Brown, supra, at 9-

10, 24.

Here, by contrast, the issue is

precisely the relevance of evidence

entirely unrelated to the character or

background of a defendant or to his crime,

but instead dealing only with collateral

facts about a victim or surviving relatives

character is irrelevant and inadmissible in

a murder trial); Fisher v. State, 482 So.2d

203, 225 (Miss. 1985) (en banc) (same);

Welty v. State, 402 So.2d 1159, 1162 (Fla.

1981) (preference for non-family member

testimony, whenever feasible, to identify

the deceased) ; c f . State_v.__Sprake, 637

S .W .2d 724, 727 (Mo. Ct. App. 1982) (in

second-degree murder case, error to call

widow solely to expose her to jury, to

engender sympathy for the family and

prejudice against the defendant); People

v. Bartall, 98 111.2d 294, 322-23, 456

N .E .2d 59, 72-73 (1983) (prosecutor's

summation on victim's rights held improper

but harmless, in part because there had

been "no presentation of irrelevant

evidence about the grieving family"); Grant

v. State, 703 P.2d 943, 945-47 (Okla. Crim.

App. 1985)(prosecutor's statement that

manslaughter victim was survived by eleven-

29

year old daughter held to be error although

harmless) .

Simply stated, courts have sought to

avoid the dangers of exposing juries to

emotion-laden evidence of dubious or non

existent relevance, both in capital and

ordinary trials. Whether or not the

Constitution requires this caution in non

capital cases, see supra note 2, it is

"essential in capital cases," Lockett v.

Ohio, 438 U.S. at 605, where the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments demand the highest

degree of protection against subjectivity

and prejudice. E .g ., Gardner v._Florida,

supra ; Turner v. Murray, supra.

l50f course, under certain

circumstances, evidence of the victim's

character, good or bad, may bear

sufficiently on issues pertinent to the

trial to be admissible. See supra note 9.

However, it is hard to envision any

setting, in a criminal case, in which such

matters as survivors' sorrow or physical or

psychological symptoms are relevant. Cf.

People v.__Levitt, 156 Cal. App. 3d at 157,

203 Cal. Rptr. at 288 (evidence of this

sort "is relevant to damages in a civil

action").

30

3. Admission of Victim Impact Evidence

Would Necessitate Admission of

Expansive Proof of a Similar Type,

Offered On Behalf of Defendants.______

A holding by the Court tolerating

victim impact evidence would necessarily

expand the scope of future penalty trials

beyond all reason. For if the Court gives

its imprimatur to a wholly new definition

of relevance in capital sentencing — a

definition loosed from the traditional

moorings of the defendant's character,

background and crime — it must also deem

relevant in mitigation proof whose reach

will be bounded only by the inventiveness

of counsel.

Take as an instance the subject of the

victim's character. What principle of

logic or fairness could deem it relevant

that the deceased was a good person and at

the same time irrelevant that he or she was

bad? Were the state permitted to prove

that a victim was educated and hard

working, a defendant should be permitted to

31

show that a victim was a sixth-grade

dropout, who never worked a day in his

life. Similarly, if it "matters" in the

context of capital sentencing that one

victim left a family who loved her, it also

"matters" that another was hated by

surviving relatives — or, indeed, left no

family at all. A defendant cannot

constitutionally be foreclosed from

offering evidence pertinent to the issues

in a criminal trial, see, e.g., Chambers v.

Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284 (1973), and the

same rule applies at the penalty phase of a

capital case. See, e.g., Green v. Georgia,

442 U.S. 95 (1979)(per curiam).16

16Where the prosecution has presented

evidence enhancing the victim, there can

simply be no way to avoid the conclusion

that the defendant has a Fourteenth

Amendment right to "'deny or explain'" it,

by proving, e.g., that the victim was

unworthy or unmourned. See, e.g., Skipper

v. South Carolina, __ U.S. at ___ n. 1, 90

L . Ed . 2d at 7 , n.~ ~1 ; ___U.S. a t ____, 90

L.Ed.2d at 9-11 (Powell and Rehnquist, JJ.,

and Burger, CJ., concurring in the

judgment) (capital defendant denied due

process when he was barred from adducing

32

But if the spectacle of the defendant

"trashing" the victim through proof and

argument seems inappropriate, consider the

further prospect of competing "victims" at

penalty trials. Suppose, for example, that

the Court sanctions introduction of a VIS

containing (as here) graphic descriptions

by family members of how the murder has

destroyed their lives and thrown them into

emotional turmoil. This very case,

reveals the type of "contest of weeping

families" that would predictably follow. In

exercising his right under Maryland law to

make an unsworn statement to the jury,

Booth sought to portray his family as

victims:

evidence of his good behavior in custody to

counter argument by prosecution that he

would be a dangerous prisoner), quoting

Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. at 362; see

generally id. (due process violation where

defendant was sentenced to death in part on

the basis of confidential information,

"which he had no opportunity to deny or ex

plain" ) .

33

Now this case, it

has had a terrible effect

on me and my family and

particularly my wife. My

* wife has attempted

suicide. My grandfather

had a stroke. He's past

[sic] away. He's

deceased now as a result

of me facing a death

penalty in this case.

* * *

The effect of this thing

on my grandmother has

been hard. She is under

doctor's care. She has

heart problems and I

think that if I am

sentenced to death, that

woman would actually die.

I know i t .

(JA __; see also JA __). The prosecution

did not object to these comments—

possibly because state law permits

"allocution" by defendants on matters not

confined to the record. See Booth, 306 Md.

at 197-99, 507 A.2d at 1111 (discussing Md.

Rule 4-343 (d)). It would seem, however,

that once VIS evidence of the sort admitted

against Booth is permitted, the defendant

must have the constitutional right to

34

present sworn statements or testimony by

parents, grandparents, children and

siblings to describe in detail their own

physical and psychological "victimization,"

which could be expected to result from

their loved one’s execution.17 If the

deceased's weeping mother has a role to

play at sentencing, by the same token so

must the defendant's: either such feelings

properly enter the capital calculus or they

do not. Yet to sanction such proof would

17Nothing in the Eighth Amendment

compels admission of such collateral

evidence, untethered to proof about the

defendant1s own better qualities. See,

e.q., Coppola v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 243,

257 S.E.2d 797 (1979)(no error in excluding

evidence of adverse effects on defendant's

children of his prosecution for capital

murder since it was irrelevant to

mitigation), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 1103

(1980); see general1y Skipper v South

Carolina. __U.S. at 90 L. Ed. 2d at 6, 8

n •2. See also Moore v. Zant, 722 F .2d at

653 n.4 (defendant should not be permitted

"to argue the victim's worthlessness in

mitigation"); State v. Gaskins, 284 S.C.

105, 128, 326 S .E .2d 132, 145 (1985)(no

error in excluding confession of victim, a

murderer under sentence of death, since

victim's status "did not entitle

[defendant] to kill him").

35

be tantamount to toppling the entire

edifice of rational capital sentencing

jurisprudence which the Court has taken

such pains to erect.

4. Victim Impact Statements Invite the

Jury to Impose Sentences of Death for

Constitutionally Impermissible Reasons.

Worse, if possible, than death

sentences that are entirely arbitrary in

the sense that a strike of lightning is

freakish, see Furman, 408 U.S. at 309-10

(Stewart, J., concurring), are those

imposed on invidious grounds: where the

lightning rod is race, religion, class or

wealth, or some other constitutionally

forbidden criterion. See Zant v. Stephens,

462 U.S. at 885; Furman, 408 U.S. at 249-51

(Douglas, J., concurring); id. at 310

(Stewart, J., concurring); id. at 363-66

(Marshall, J., concurring); Moore v. Zant,

722 F .2d at 645-46. In addressing the

necessarily capricious quality of victim

36

impact evidence, Judge Cole once again gave

eloquent voice to the basic problems:

What can be a more

arbitrary factor in the

decision to sentence a

defendant to death than

the words of the victim's

family, which vary

greatly from case to

case, depending upon the

ability of the family

member to express his

grief, or even worse

depending upon whether

the victim has family at

all? In more practical

terms, a killer of a

person with an educated

family would be put to

death, whereas in a crime

of similar circumstances,

the killer of a person

with an uneducated family

or one without a family

would be spared.

Booth. 306 Md. at 233, 507 A.2d at 1129

(Cole, J., concurring in part and

dissenting in part). It is no great leap

from the judge's perception of the

arbitrariness of the listed factors to an

understanding that these — and others—

have a highly discriminatory potential.

37

This is so for a number of reasons.

First, such characteristics as the

articulateness of family members will often

be the products of class or wealth, thereby

serving as surrogates for impermissible

status considerations that no one would

claim should influence capital

sentencing.18 Further, not only the mode of

expression but also its substance typically

encourages the jurors to consider the

social value of the victim and "compare the

relative worth of the victim and the

defendant to society."19 See Brooks v.

Kemp, 762 F.2d 1383, 1439 (11th Cir. 1985)

18It is instructive in this regard to

compare the power of expression of the VIS

in Booth, see infra at 40-45, with

petitioner's admitted sense of inadequacy

in allocution: "I've never been a real good

speaker in front of people or anything like

that. I'm not gifted with words or nothing

like that." (JA ___).

19Cf. Moore v. Zant, 722 F.2d at 653

n.4 (Kravitch, J., concurring in part and

dissenting in part)(invoking "spectre" of

statute listing as aggravating factor that

"victim of the murder was a valuable member

of society and of her family").

38

(en banc) (Clark, J., concurring in part

and dissenting in part), vacated on other

grounds, __ U.S. ______ 92 L . Ed. 2d 732

(1986); Moore v. Zant, 722 F.2d at 652-53

(Kravitch, J., concurring in part and

dissenting in part). Social worth, as the

jurors view it, will also tend to vary with

factors like education, class and wealth,

whether of the victim or the survivors—

and, regrettably, often with race or

religion as well. See, e .g ,, People v.

Holman, 103 111. 2d at 167-68, 469 N.E.2d

at 135 (death sentence vacated where

prosecutor alluded to "religous moral

fiber" of victim's mother as well as

accomplishments of victim); see generally

Turner v._Murray, supra (especially great

risk of racial discrimination in capital

sentencing). By its very nature, this type

of evidence invites the jury to "choose up

sides," to empathize with the (usually more

attractive) victim or the victim's family,

39

in particular where these are white,

middle-class, and otherwise similar to most

of the jurors.

II.

THE ADMISSION AT PETITIONER'S

PENALTY TRIAL OF A LONG,

IRRELEVANT, INFLAMMATORY VICTIM

IMPACT STATEMENT VIOLATED

PETITIONER'S RIGHTS UNDER THE

EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS.

Agent Michelle Swann of the Division of

Parole and Probation prepared a four-page,

single-spaced VIS in this case, reporting

the reactions of the victims' son,

daughter, son-in-law, and one

granddaughter. The statement is fully set

out in the Joint Appendix (JA ___) and is

excerpted in Petitioner's Brief. See id . at

___ (Statement of the Case). For present

purposes, a small sampling of the data

contained within this document — which the

prosecutor in his closing urged the jurors

to "'read out loud'" in the jury room—

provides a graphic illustration of why this

40

kind of proof is anathema to rational

capital sentencing.2®

First, the VIS was replete with

emotional and incendiary comments. For

example: "'The victims' son feels that his

parents were not killed but were butchered

like animals'." (JA ___). The victims'

daughter "'saw the bloody carpet, knowing

that her parents had been there, and she

felt like getting down on the rug and

holding her mother'." (JA ___). "'[S]he

could never forgive anyone for killing them

that way'" and "'states that animals

wouldn't do this'." (JA___).

Interspersed among such remarks were

statements amounting to calls for a death

20Booth, 306 Md. at 240, 507 A.2d at

1133 (Cole, J., concurring in part and

dissenting in part)(emphasis in original).

In light of the prosecutor's exhortation

and the fact that the VIS (and the rest of

the presentence investigation report)

comprised the entire state's case at

sentencing, 306 Md. at 194, 507 A.2d at

1109, the use of this grossly inflammatory

statement could not have amounted to

harmless error.

41

sentence,21 expressions of sentiments of

revenge, and implicitly adverse judgments

about the course of the prosecution. The

daughter, for instance, "'attended the

defendant's trial and that of the co-

defendant because she felt someone should

be there to represent her parents'." (JA

). "'She doesn't feel that the people

who did this would ever be rehabilitated

and she doesn't want them to be able to do

this again or put another family through

this'." (JA ___). The son "'doesn't think

anyone should be able to do something like

this and get away with it'." (JA __ ).

Further,

"the victims' family members

note that the trials of the

suspects charged with these

offenses have been delayed for

over a year and the

postponements have been very

^introduction of sentencing

recommendations in a capital penalty trial

is forbidden by Maryland law. Md. Code,

art. 27, section 413(c)(iv). See Lodowski,

302 Md. at 775, 490 A.2d at 1271 (Cole, J.,

concurring).

42

hard on the family

emotionally.... The family

wants the whole thing to be

over with and they would like

to___see___swift and lust

punishment ."

(JA ___)(emphasis added).

In addition to quoting more comments of

a similar nature, the VIS recounted the

various physical and psychological problems

experienced by the interviewees as well as

by other members of the family. The

statement noted, for instance, that a

granddaughter with whom the agent had not

spoken had had her wedding, honeymoon and

associated memories ruined by the tragic

events of the time {JA ___); different

grandchildren (also not interviewed by the

agent) were poignantly reported as having

first learned of their grandparents' death

via television. (JA ___).

The VIS also described the victims in

extremely laudatory terms as "'amazing'"

people, who enjoyed a "'very close

relationship'," "'had made many devout

43

friends'" (JA ), and whose funeral was

"'the largest in the history'" of the

funeral home. (JA ___). Finally, it

contained editorial comments by Agent

Swann22 and global statements by the

22See, e.q.: "'Perhaps [the grand

daughter] described the impact of the

tragedy most eloquently when she stated

that it was a completely devastating and

life altering experience'." (JA ___). The

agent's "peroration," with which the VIS

ended, was as follows:

"It became increasingly

apparent to the writer as

she talked to the family

members that the murder

of Mr. and Mrs. Bronstein

is still such a shocking,

painful and devastating

memory to them that it

permeates every aspect of

their daily lives. It is

doubtful that they will

ever be able to recover

fully from this tragedy

and not be haunted by the

memory of the brutal

manner in which their

loved ones were murdered

and taken from them."

(JA ) (emphasis added). C_f. State v.

Rushing, 464 So.2d 268, 275 (La. 1985),

cert, denied, _ _ U . S . ___, 90 L. Ed. 2d 703

(1986) (error to admit testimony that

killing was one of most vicious policeman

had ever seen since this was tantamount to

44

survivors that their lives would never be

the same again.

* * *

No one could remain untouched by the

genuine suffering conveyed in the

statement. But that is, in fact, our

point. This type of emotional, inflammatory

evidence "has no place in a statutory

weighing process which owes its very

existence to the constitutional mandate

that the death penalty must not be

administered in an arbitrary or capricious

manner." Booth, 306 Md. at 241, 507 A.2d at

1133 (Cole, J., concurring in part and

dissenting in part). Survivors (and

understandably sympathetic parole and

probation agents) cannot be permitted to

function as supplemental prosecutors,

raising a hue and cry for vengeance.

Because petitioner's sentence of death very

opinion that alleged aggravating factor

existed).

45

likely was -- and surely appeared to be--

based on caprice and emotion, not reason,

this Court must overturn it.

CONCLUSION

The Court should reverse the judgment

of the Court of Appeals of Maryland.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

VIVIAN BERGER*

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University Law

School

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

(212) 598-2638

Attorneys for the NAACP

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund,_Inc.

By:_____________

Vivian Berger

*Counsel of Record

Dated: December 3, 1986

46

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177