Venegas v. Mitchell Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 15, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Venegas v. Mitchell Brief Amici Curiae, 1989. 5d404604-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cf5857d5-0979-441b-9963-3e3d553ae7e7/venegas-v-mitchell-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

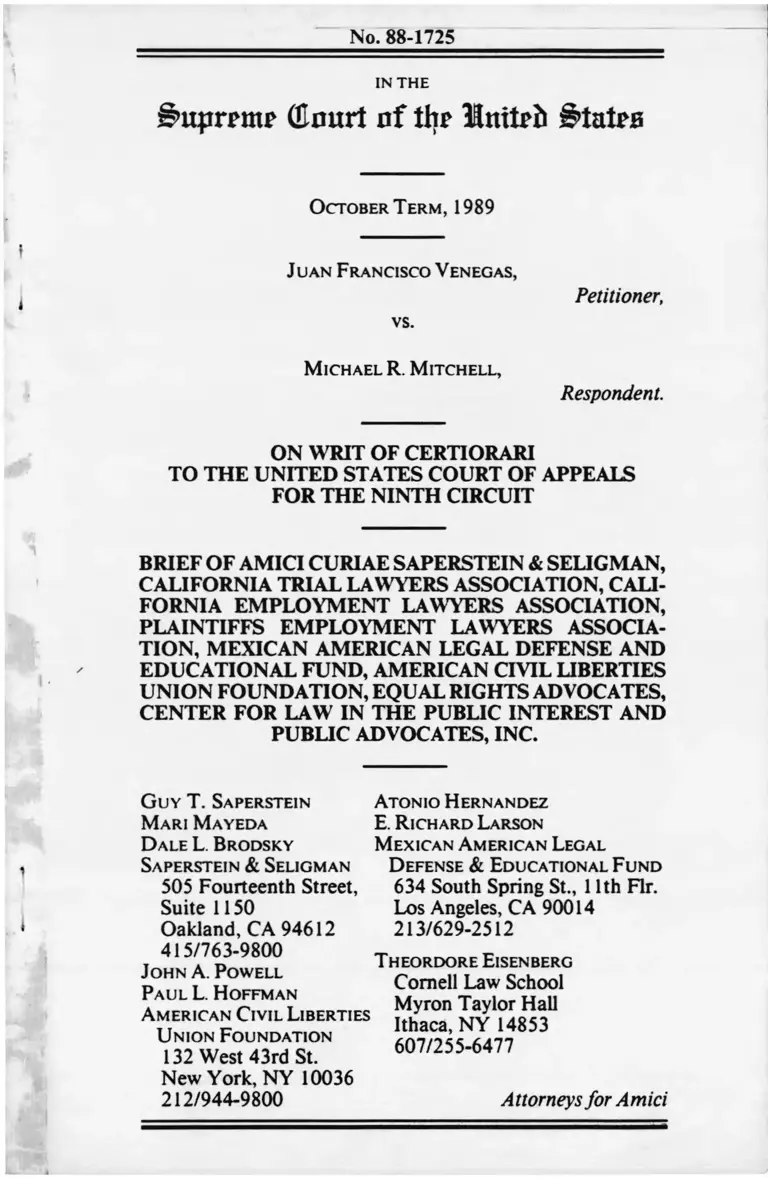

No. 88-1725

IN THE

i>uprrmp (Eourt of tlir

\

i

October Term, 1989

Juan Francisco Venegas,

vs.

Petitioner,

M ichael R. M itchell,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE SAPERSTEIN & SELIGMAN,

CALIFORNIA TRIAL LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, CALI

FORNIA EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION,

PLAINTIFFS EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIA

TION, MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION, EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES,

CENTER FOR LAW IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST AND

PUBLIC ADVOCATES, INC.

1

1

G uy T. Saperstein

Mari Mayeda

D ale L. Brodsky

Saperstein & Seligman

505 Fourteenth Street,

Suite 1150

Oakland, CA 94612

415/763-9800

John A. Powell

Paul L. Hoffman

A merican Civil Liberties

U nion Foundation

132 West 43rd St.

New York, NY 10036

Atonio H ernandez

E. R ichard Larson

Mexican American Legal

D efense & Educational Fund

634 South Spring St., 11th Fir.

Los Angeles, CA 90014

213/629-2512

T heordore Eisenberg

Cornell Law School

Myron Taylor Hall

Ithaca, NY 14853

607/255-6477

212/944-9800 Attorneys for Amici

1

QUESTION PRESENTED

Did Congress, in enacting the Civil Rights Attorney’s

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, intend to add

recovery of statutory fees to the already existing system

of fee agreements without abrogating enforceable written

contracts?

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTEREST OF AMICI CU RIA E.................................. 1

SUMMARY OF A RG U M EN T..................................... 6

ARGUM ENT.................................................................... 7

I. FEE AGREEMENTS ARE ESSENTIAL IN

DUCEMENTS TO THE PROSECUTION OF

CIVIL RIGHTS CASES........................................... 7

A. The Fee Agreement Is and Has Always Been

a Critical Inducement to Accepting Represen

tation of Clients With Meritorious Claims

Who Cannot Afford to Hire Lawyers.............. 7

B. Issues Regarding Regulation of the Terms

of Fee Agreements Should Be Left to the

Extensive Fee Regulatory System................... 9

C. The Invalidation of All Fee Contracts Would

be an Unwarranted Affront to the Right to

C on tract............................................................... 11

II. ENFORCEMENT OF OTHERWISE PERMIS

SIBLE FEE CONTRACTS IS CONSISTENT

WITH CONGRESS’ LANGUAGE AND

INTENT .................................................................... 14

A. The Plain Language of the Statute as Well as

the Legislative History Clearly Demonstrate

that Congress Did Not Intend to Void the

Right to C ontract............................................... 14

B. Enforcement of Respondent’s Fee Agreement

Is Consistent with Prior Supreme Court Rul

ings ........................................................................ 17

III. EXPERIENCE UNDER SECTION 1988

COUNSELS AGAINST INVALIDATING FEE

CONTRACTS........................................................... 19

CONCLUSION................................................................. 22

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Agarwal v. Johnson, 25 Cal.3d 932 (1979)............... 10

Alcorn v. Anbro Engineering, Inc., 2 Cal.3d 493

(1970).......................................................................... 10

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240(1975)................................................. 16

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456 U.S. 63

(1982).......................................................................... 14

Blanchard v. Bergeron,____ U .S ._____, 109 S.Ct.

939(1989).................................................................. 18, 19

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886 (1984)...................... 7, 17

Caminetti v. U.S., 242 U.S. 470 (1917).................... 14

Christianburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412

(1978).......................................................................... 12

City o f Riverside v. Rivera, A ll U.S. 561 (1986).... 10

Crawford Fitting Co. v. J. T. Gibbons, 482 U.S. 437

(1987).......................................................................... 15, 18

Evans v. JeffD., 475 U.S. 717 (1986)....................... 8, 16,19

Farmington Dowel Products Co. v. Foster Mfg. Co.,

421 F.2d 61 (1st Cir. 1969)..................................... 7, 11

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983)................ 7

INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U.S. 421 (1986)......... 14

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974)................................................... 16

Kelly v. Robinson, 479 U.S. 36 (1986)....................... 14

Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc. v. American Radiator &

Standard Sanitary Corp., 540 F.2d 102 (3d Cir.

1976)........................................................................... 7

Lockheed Minority Solidarity Coalition v. Lockheed

Missiles & Space Co., 406 F. Supp. 828 (N.D.

Cal. 1976)................................................................... 22

Manhart v. City o f Los Angeles, 652 F.2d 904 (9th

Cir.), vacated and remanded on other grounds,

461 U.S. 951 (1983)................................................. 7

Oki America, Inc. v. Microtech International, Inc.,

872 F.2d 312 (9th Cir. 1989)................................. 13

IV

Page

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens Council

for Clean Air, 478 U.S. 556 (1986)........................ 11

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens Council

for Clean Air, 483 U.S. 711 (1987)........................ 18

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal.

1974)........................................................................... 17

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Education,

66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975)............................ 17

United States v. Hohri, 482 U.S. 64 (1987)............. 14

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,____ U.S______,

109 S.Ct. 2115 (1989).............................................. 20

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

15 U.S.C. § 15g( 1) (A) (b ) ............................................ 15

28 U.S.C. § 1821........................................................... 15

28 U.S.C. § 2412(d)(1) (A)......................................... 15, 17

ABA Code of Professional Responsibility

DR 1-106 (1981)....................................................... 9

ABA Informal Opinion 86-1521................................. 11

ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct

Rule 1.5 (1983).......................................................... 9

American-Mexican Chamizal Convention Act of

1964, 22 U.S.C. §277d-21...................................... 15,16

Antitrust Civil Process Act Amendments Pub. L.

94-435, 90 Stat. 1394 (1976) 15 U.S.C. §§ 15b-h. 15

Cal. Civil Code § 5 1 ...................................................... 10

Cal. Const., Art. 1.......................................................... 13

Cal. Govt. Code § 12940.............................................. 10

California Business & Professions Code § 6200, et

seq................................................................................. 9

California Business and Professions Code § 6000,

et seq............................................................................ 9

California State Bar Rules of Professional Responsi

b ility ............................................................................ 9

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act Pub. L.

94-559, 90 Stat. 2641, 42 U.S.C. § 1988............... passim

Coast Guard Act 14, U.S.C. § 4 3 1(c)......................... 15

Const., Art. I § 10.......................................................... 13

Federal Tort Claims Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2678............. 15, 17

International Claims Settlement Act of 1949, 22

U.S.C. §§ 1623(f), 16310), 1641 (p), 1642(m),

1643(k)........................................................................ 15

Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948,

50 U.S.C. App. § 1985.............................................. 16

Military Personnel and Civilian Employees Claims

Act of 1964 as amended, 31 U.S.C. § 3721 (i) ...... 16

Organic Act of Guam, 48 U.S.C. § 1424.................. 16

Servicemen’s Group Life Insurance Act, 38 U.S.C.

§ 784(g)........................................................................ 16

Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. § 406(a)................... 15,17

Other Authorities

3 C. D. Sands Sutherland Statutory Construction

§46.01 (4th Ed. 1986).............................................. 14

Administrative Office of the United States Courts

1984 Annual Report of the D irector..................... 20

Eisenberg & Schwab, The Reality o f Constitutional

Tort Litigation, 72 Cornell L. Rev. 641 (1987)... 20, 21

Mandatory Arbitration o f Attorney-Client Fee Dis

putes: A Concept Whose Time Has Come, 14

Toledo L. Rev. 1205(1983).................................... 9,10

Schwab & Eisenberg, Explaining Constitutional

Tort Litigation: The Influence o f The Attorneys

Fee Statute and the Government as Defendant,

73 Cornell L. Rev. 719 (1988)............................... 8, 21

IN THE

g>uprnttr (Enurl of lltutpfo States

OctoberT erm, 1989

Juan Francisco Venegas,

vs.

Petitioner,

M ichael R. M itchell,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE SAPERSTEIN & SELIGMAN,

CALIFORNIA TRIAL LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, CALI

FORNIA EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION,

PLAINTIFFS EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIA

TION, MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION, EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES,

CENTER FOR LAW IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST AND

PUBLIC ADVOCATES, INC.

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici curiae represent an array of private civil rights

attorneys and trial lawyers’ organizations who depend on fee

agreements in their representation of civil rights, environ

mental, and public interest plaintiffs. Amici also represent

numerous non-profit civil rights and public interest organiza

tions which are actively involved in civil rights cases.

The amici are:

2

SAPERSTEIN & SELIGMAN, P.C., Oakland, California

This seventeen-year-old, 32-lawyer firm specializes in

plaintiffs’ employment discrimination litigation, both indi

vidual and class actions. Contingent fee agreements are

commonly chosen by clients because civil rights victims

typically cannot afford any other type of fee arrangement.

Frequently, the client is not obligated to pay for either costs

or legal services during the course of the litigation.

A contingent fee agreement which entitles the firm to a

percentage of the recovery is an important incentive for

undertaking the risk of representing civil rights plaintiffs.

Prohibiting the firm from entering into contingent fee agree

ments would seriously deter them from representing civil

rights plaintiffs.

CALIFORNIA TRIAL LAWYERS ASSOCIATION

The California Trial Lawyers Association (CTLA) is a

statewide organization of plaintiffs’ trial attorneys. CTLA’s

approximately 6,500 members derive legal fees from contin

gent fee work and have represented hundreds of civil rights

plaintiffs on contingent fee contracts. If CTLA’s members

were prohibited from entering into contingency fee agree

ments, many would simply not handle civil rights cases.

CALIFORNIA EMPLOYMENT

LAWYERS ASSOCIATION

The California Employment Lawyers Association is a

statewide organization of plaintiffs’ attorneys who practice

employment and discrimination law. Members of this organi

zation are involved in employment and civil rights cases and

commonly accept representation of plaintiffs on a contingent

fee basis. Currently, there are a small number of attorneys left

in California willing and capable of prosecuting employment

3

discrimination cases on behalf of plaintiffs. This figure would

dwindle to almost nothing if employment attorneys were

prohibited from contracting with their clients on a contin

gency basis for a percentage of the recovery.

PLAINTIFFS EM PLOYM ENT

LAWYERS ASSOCIATION

The Plaintiffs Employment Lawyers Association (PELA)

is a nationwide organization of plaintiffs employment attor

neys. Members of PELA are involved in employment, civil

rights and public interest litigation and rely on contingent fee

agreements to pursue these cases. If statutory fees were the

only fee recovery in civil rights cases, many of PELA’s

members would be out of the business of prosecuting civil

rights claims.

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (MALDEF) is a national civil rights organization estab

lished in 1967. Its principal objective is to secure, through

litigation and education, the civil rights of Hispanics living

in the United States. This objective is pursued in part by

MALDEF’s provision of free legal representation to civil

rights plaintiffs in nonmonetary cases. MALDEF recognizes,

however, that the rights of Hispanics are also vindicated in

cases involving potentially sizeable monetary recovery by

private counsel retained on a contractual basis. Both types

of representation are essential to securing the civil rights of

Hispanics.

4

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION,

New York, New York

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION

OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles, California

The American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) is a non

profit public interest organization with more than 275,000

members and more than 50 affiliates in nearly every state,

including the ACLU of Southern California (“ACLU/SC”).

Both the ACLU and its affiliates are dedicated to protecting

the civil rights and civil liberties of all persons in the United

States. The ACLU, through its legal staff and hundreds of

volunteer attorneys, has been involved in hundreds of cases

brought under the federal civil rights laws to vindicate these

rights.

Though the ACLU does not sponsor cases on a contingent

fee basis it has a strong interest in maintaining the availability

of attorneys fee awards to private counsel involved in bringing

civil rights actions. To the extent that the Civil Rights

Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,42 U.S.C. Section 1988,

is interpreted in a way that creates disincentives for the

private bar to handle civil rights cases, the ACLU believes

that the purposes of the civil rights laws will be undermined

and many deserving civil rights plaintiffs will remain

unrepresented.

EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES, INC.,

San Francisco, California

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. (ERA) is a non-profit public

interest law firm dedicated to achieving equality of rights

under the law for women. ERA regularly handles intake and

referral of sex discrimination matters, and has great difficulty

finding attorneys willing to represent clients who cannot

afford legal counsel.

5

CENTER FOR LAW IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST,

Los Angeles, California

The Center for Law in the Public Interest (CLIPI) is a

non-profit public interest law firm. CLIPI’s public interest

litigation includes employment discrimination and environ

mental cases. The Center regularly handles intake and referral

of civil rights, environmental and public interest litigation.

Such cases are virtually impossible to refer to private counsel

where the client cannot afford the cost of legal services.

PUBLIC ADVOCATES, INC., San Francisco, California.

Public Advocates, Inc. is a non-profit public interest law

organization which has been representing poor and minority

individuals and organizations since 1971. The bulk of Public

Advocates’ litigation is in the fields of education, health

care, homelessness, economic development and employment.

Many, if not most of Public Advocates’ cases are co-counseled

with private attorneys and legal services organizations. The

availability of co-counseling arrangements with private attor

neys would be impaired by a prohibition against private fee

contracts.

6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The amici submitting this brief are private practitioners

and non-profit public interest and civil rights organizations

that are litigating hundreds of cases under fee shifting statutes.

Unless privately negotiated fee agreements are available,

the congressional goal of enabling clients to find competent

lawyers needed to enforce civil rights and environmental

legislation will be frustrated. The already severely diminis

hing number of attorneys willing to handle such cases would

decrease even further if the Court were to take away one of

the traditional means for attorneys to undertake representa

tion for clients who cannot afford legal services—the contin

gent fee contract.

Fee contracts are subject to regulation under state and

federal statutes and are even further regulated by state, local

and American Bar Association ethical rules and regulations

which in this case includes the Rules of Professional Conduct

of the State Bar of California. Usurpation of this extensive

fee regulation system was not contemplated by Congress

when it enacted the civil rights fee shifting provisions.

As there is no indication that Congress intended to

eliminate the contract rights of attorney and client, the deci

sion of the Ninth Circuit should be affirmed.

7

ARGUMENT

I.

FEE AGREEMENTS ARE ESSENTIAL

INDUCEMENTS TO THE PROSECUTION

OF CIVIL RIGHTS CASES

A. The Fee Agreement Is and Has Always Been a Critical

Inducement to Accepting Representation of Clients With

Meritorious Claims Who Cannot Afford to Hire Lawyers

Enforcement of privately negotiated fee agreements

which permit the attorney to recover a percentage of the

damages is consistent with the aim of the fee shifting statutes,

which seek to provide an incentive for attorneys to represent

clients with meritorious civil rights and environmental

claims. This fundamental congressional purpose has been

repeatedly recognized by this Court.1

The importance of the fee agreement as an inducement

is demonstrated by its consistent use in the legal market place

in civil rights and comparable complex federal litigation.2

Unlike civil rights defendants, civil rights plaintiffs often lack

the resources to pay for representation during the course of

litigation. Indeed, clients represented by amici frequently

1 See Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 429 (1983) (“The

purpose of § 1988 is to ensure ‘effective access to the judicial

process’ for persons with civil rights grievances. H.R. Rep. No. 94-

1558, p. 1 (1976).”); Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 897 (1984)

(“The legislative history [of § 1988] explains that ‘a reasonable

attorney’s fee’ is one that is ‘adequate to attract competent counsel,

bu t . . . [that does] not produce windfalls to attorneys.’ S. Rep. No.

94-101 l,p. 6(1976).”).

2 See, e.g., Manhart v. City o f Los Angeles, 652 F.2d 904 (9th

Cir.), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 461 U.S. 951 (1983);

Lindy Bros. Builders, Inc. v. American Radiator & Standard Sanitary

Corp.. 540 F.2d 1021 (3d Cir. 1976) (antitrust case); Farmington

Dowel Products Co. v. Foster Mfg. Co., 421 F.2d 61 (1st Cir. 1969)

(“Farmington /”).

8

cannot even afford to pay for the non-fee costs of litigation.

Therefore, private civil rights plaintiffs’ counsel may have no

realistic alternative but to enter into fee arrangements in

order to meet the costs of running their practices.

Evans v. Jeff D., 475 U.S. 717 (1986) has made the

practical need for fee agreements in cases involving fee

shifting statutes even greater. In Evans, this Court held that

plaintiffs in a civil rights action could waive the right to

statutory attorneys’ fees. Given the possibility that the client

may waive statutory attorney’s fees altogether, separate fee

contracts between plaintiffs and their counsel have become

essential. In an Evans situation, the only protection available

for private attorneys is to have in effect a fee agreement. If

such agreements are not available in fee shifting cases, the

threat of forced fee waivers under Evans would make civil

rights cases financially devastating for plaintiffs’ attorneys.

Not only would such cases not be financially competitive with

other cases, they would lead to financial ruin for even the

most successful of plaintiffs’ firms.

Failure to enforce ethically permissible fee agreements

will undermine the economic viability of the sole practitioners

and small firms that make up the bulk of the experienced

private civil rights bar, and will inevitably lead to the with

drawal of many of the most experienced and talented attor

neys from this practice.3 Thus, invalidation of privately

negotiated fee contracts would be a serious, and perhaps

devastating, setback to the enforcement of the civil rights and

environmental laws. The only beneficiaries of such a financial

disincentive would be the violators of those laws.

3 Contrary to Petitioner’s assertion at page 28 of his brief, most

civil rights litigation is brought by small private firms and solo

practitioners. See Schwab & Eisenberg, Explaining Constitutional

Tort Litigation, 73 Cornell L. Rev. 719,768 (1988).

9

B. Issues Regarding Regulation of the Terms of Fee Agree

ments Should Be Left to the Extensive Fee Regulatory

System

Many of the issues raised by Petitioner involve fact

specific matters of contract interpretation and ethical princi

ples that are best left to the extensive enforcement mecha

nisms already in place among local, state and national bar

associations, state regulatory provisions, and fee arbitration

panels which routinely regulate attorney-client fee disputes.

In this case, this includes the ABA Model Rules of Profes

sional Conduct, Rule 1.5 (“Fees”) (1983), the ABA Code

of Professional Responsibility DR 1-106 (“Fees for Legal

Services”) (1981), as well as various provisions of the Califor

nia Business and Professions Code, § 6000, et. seq., and the

California State Bar Rules of Professional Responsibility. In

addition, numerous local agencies such as state and county

bar associations have fee arbitration panels which routinely

consider questions regarding the enforcement of fee

agreements.4

4 See Mandatory Arbitration o f Attorney-Client Fee Disputes:

A Concept Whose Time Has Come, 14 Toledo L. Rev. 1205 (1983).

These fee arbitration agencies include: Alaska Bar R. 35-42; Rules

of Comm, of the State Bar of Ariz. on Arbitration of Fee Disputes;

By-Laws of the Legal Fee Arbitration Comm, of the Bar Ass’n of

Greater Cleveland and the Rules and Regulations of its Legal Fee

Arbitration Bd.; Rules for Arbitration for Legal Disputes, Conn.

Bar Ass’n; Rules of the Fee Dispute Comm, of the Dallas Bar Ass’n;

Model Fee Arbitration Bylaws, as adopted by the Fla. Bar Ass’n;

State Bar of Ga.’s Fee Arbitration R.; Rules of the Idaho State Bar

on Arbitration of Fee Disputes; Rules for the Arbitration Comm.,

as approved by the Iowa State Bar; Mich. Gen. CT.R.979; Legal

Fee Arbitration Plan, as adopted by the Ky. Bar Ass’n; Resolution

of Fee Disputes, N.H. Bar Ass’n; NJ.Ct.R. 1:20A; Section 739, By-

Laws of the Philadelphia Bar Ass’n Rules to the Fee Dispute

Comm, of the Philadelphia Bar Ass’n; Procedures of the Legal Fee

Arbitration Bd. of the Minn. State Bar; Rules of the Comm, on

Resolution of Fee Disputes, the Bar Ass’n of Metropolitan St. Louis;

Fee Arbitration Rules, as adopted by the State Bar of Wis.; Cal.

Bus. & Prof. Code § 6200, et seq.: Rules of Procedures for the

10

Reference to state and local fee regulation is not only

prudent, but will frequently be necessary in civil rights and

other fee shifting cases due to the common existence of

pendent state claims. Thus, fee agreements in fee shifting

cases frequently apply to both federal and state law claims.

For example, in City o f Riverside v. Rivera, 477 U.S. 561

(1986), plaintiffs prevailed on both their federal claims and

their state law negligence claims. Id. at 564. Had plaintiffs’

counsel wished to enforce a fee contract in that case, the

Tenth Amendment would require that the fee contract based

on the state law tort causes of action be governed and enforced

in accordance with state law.

The same is true of discrimination cases in California,

where the state legislature has enacted state statutes prohibit

ing discrimination in employment, housing and public ac

commodations and services. See Cal. Govt. Code § 12940,

et. seq.; Cal. Civil Code § 51. Other pendent state claims are

often included in federal civil rights cases in California,

including intentional infliction of emotional distress predi

cated on a discrimination theory.5 In these cases involving

both federal and state discrimination causes of action, the

California courts would have the right to determine and

regulate the attorneys’ fees contract questions in accordance

with local and state bar professional rules of responsibility,

(footnote 4 continued from page 9)

Hearing of Fee Arbitration Proceedings by the Alameda County

Bar Ass’n; Rules for Arbitration Proceedings for Attorney Fee

Disputes, Beverly Hills Bar Ass’n; Rules for Conduct of Fee Dis

putes and Other Related Matters, Los Angeles County Bar Ass’n;

Rules of Conduct of Fee Arbitrations by the Fee Arbitration Comm,

of the Santa Clara County Bar Ass’n; San Diego County Bar Ass’n

Rules of the Arbitration Comm. Id. at 1226 n.104.

5 See. e.g., Agarwal v. Johnson, 25 Cal.3d 932 (1979) (inten

tional infliction of emotional distress based on racial epithets);

Alcorn v. Anbro Engineering, Inc., 2 Cal. 3d 493 (1970) (supervisor

shouting epithets to plaintiff).

11

California contract law, and the fee contract provisions of

the California Business & Professions Code.

C. The Invalidation of All Fee Contracts Would be an Unwar

ranted Affront to the Right to Contract

The result sought by Petitioner would invalidate fee

agreements under a number of statutes and would not be

limited to interfering with the right to contract only in civil

rights cases. This Court and Congress have stated that fee

shifting statutes are to be interpreted uin pari materia”.6

Thus, contracts regarding environmental, civil rights, and

other fee shifting statutes are subject to invalidation regard

less of whether or not the client is willing to abide by the

terms of the contract, as was the case in Farmington Dowel

Products Co. v. Foster Mfg. Co., 421 F.2d 61 (1st Cir. 1969).7

Since the statutory fee is only awarded if the client wins,

and no statutory fee is awarded if the client loses, the radical

result sought by Petitioner— an order prohibiting the attorney

in this and consequently any fee shifting case from collecting

a fee except the statutory fee— imposes on the attorney and

client a forced contingent arrangement. The result of this

forced bargain would be that the right to contract for even a

standard hourly agreement is abrogated.8 Attorney and client

6 See, e.g., Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens’ Council

for Clean Air, 478 U.S. 556, 559 (1986) (“Delaware Valley /"); S.

Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., 6 (1976).

7 Farmington is considered the leading case on the relationship

between the statutory and ethical tests which govern fee amounts.

In Farmington, an antitrust case, the Court held that the statutory

and ethical tests for a reasonable fee were different. 421 F.2d at

90. It instructed the district court to determine the “maximum

ethically allowable fee," to assess the reasonable statutory fee from

defendant, and to require plaintiff to pay only such further amount

as would constitute a fee that was not excessive under the ethical

standards. Id. at 87.

8 This result raises serious ethical concerns. In 1986 the

American Bar Association Standing Committee on Ethics and

Professional Responsibility issued Informal Opinion 86-1521, stat

ing that it is unethical for a lawyer not to offer clients alternative

fee arrangements before accepting a case on a contingent-fee basis.

12

should be encouraged— not prohibited from— negotiating fee

contracts which best suit the needs and financial circum

stances of each case.

Invalidation of fee contracts also unnecessarily interferes

with economic regulation which occurs in the legal market

place. If statutory fees alone were sufficient to attract an

adequate supply of attorneys, then these types of agreements

would dominate the marketplace. If, however, statutory fees

were insufficient consideration, civil rights plaintiffs will have

to have some “bargaining chip” to induce attorneys to accept

their cases. Traditional bargaining tools which clients can

utilize to obtain counsel include contemporaneous hourly

agreements, lump sum “retainer” agreements, and contingent

fee agreements.

The ruling sought by Petitioner would also interfere with

all fee contracts negotiated between civil rights defendants

and their counsel. This Court has recognized that the civil

rights statutes, like “many of the statutes”, have “flexible”

fee provisions which authorize “the award of attorney’s fees

to either plaintiffs or defendants”. Christianburg Garment

Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412,416 (1978).9 Since either plaintiff

or defendant may be a “prevailing party” within the meaning

of the civil rights fee statutes, limiting fees to those available

under a statutory award would invalidate a broad array of

plaintiffs’ and defendants’ free market contracts. Surely,

Congress never intended such interference with the rights of

parties to negotiate free market contracts regarding payment

for legal representation.

Thus, to interpret the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees

Awards Act as precluding private fee agreements between

clients and their attorneys would be a substantial burden on

those parties’ right to enter contracts. In interpreting such

9 The Christianburg standard, although decided under Title

VII’s fee provision, applies to numerous fee statutes. See Chris

tianburg, 434 U.S. at 416 n.7.

13

legislation the importance of the individual’s right freely to

enter into contracts should not be overlooked. The impor

tance of the right to contract is underscored by the contract

clauses of the Federal and State Constitutions.10

While courts and legislatures alike have been more will

ing to substitute their own judgment of what is a sound and

worthwhile business transaction for the judgments of private

individuals in the marketplace, this is not appropriate here.

As Judge Alex Kozinski stated in a recent opinion:

Perhaps most troubling, the willingness of courts to

subordinate voluntary contractual arrangments to

their own sense of public policy and proper business

decorum deprives individuals of an important mea

sure of freedom. The right to enter into contracts—

to adjust one’s legal relationships by mutual agree

ment with other free individuals— was unknown

through much of history and is unknown even today

in many parts of the world. Like other aspects of

personal autonomy, it is too easily smothered by

government officials eager to tell us what’s best for

us. The recent tendency of judges to insinuate

tort causes of action into relationships traditionally

governed by contract is just such overreaching. It

must be viewed with no less suspicion because the

government officials in question happen to wear

robes.

Oki America, Inc. v. Microtech

International, Inc.

872 F.2d 312, 316 (9th Cir. 1989)

(Kozinski, J., concurring)

Judge Kozinski’s remarks regarding the expansion of tort

causes of action into the contract area applies with even

greater force to the proposed interpretation of the Civil Rights

Attorney’s Fees Awards Act. For, if the Court interprets that

Act as Petitioner suggests, it will obliterate the free market

rights of the parties and their attorneys to enter into private

contracts and will place the entire matter of what consider

10 Const., Art. I § 10; see. e.g., Cal. Const., Art. I.

14

ation attorneys will be paid for representing such clients—

normally the subject of free negotiation between client and

attorney— into the hands of the judiciary. This affront to

contract rights should not be lightly embraced by this Court.

II.

ENFORCEMENT OF OTHERWISE

PERMISSIBLE FEE CONTRACTS IS CONSISTENT

WITH CONGRESS’ LANGUAGE AND INTENT

A. The Plain Language of the Statute as Well as the Legisla

tive History Clearly Demonstrate that Congress Did Not

Intend to Void the Right to Contract

Petitioner has postulated that the legislative history of

the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976“ sup

ports the abrogation of the right of attorney and client to

agree to the terms of an ethically permissible fee contract.

To the contrary, the clear language of the statute, as well as

its legislative history, belie this view.

It is a fundamental rule of statutory construction that

“the meaning of the statute must, in the first instance, be

sought in the language in which the act is framed, and if that

is plain, . . . the sole function of the courts is to enforce it

according to its terms.” Caminetti v. U.S., 242 U.S. 470,485

(1917). If the language is unambiguous, it is inappropriate to

resort to legislative history to interpret the statute. American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson. 456 U.S. 63, 68 (1982). See also

INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca. 480 U.S. 421, 431-32 (1986); Kelly

v. Robinson, 479 U.S. 36, 43 (1986); United States v. Hohri,

482 U.S. 64 (1987); 3 C.D. Sands, Sutherland Statutory

Construction, §46.01 (4th Ed. 1986). 11

11 The Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act, Pub. L.

94-559, 90 Stat. 2641, as set forth in 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

15

Just weeks before Section 1988 was enacted, Congress

passed the Antitrust Civil Process Act amendments of 1976.12

During the course of the lengthy debates on the antitrust

amendments, the legislators focused considerable attention

on the availability of contingent fees for private attorneys.

As a consequence, both the House and Senate ultimately

agreed to explicitly prohibit private attorneys from collecting

contingency fees based on a percentage of monetary relief

unless the award of fees is determined by a court. See 15

U.S.C. § 15g( 1 )(A) and (B).

In contrast to the contingent fee prohibition in the

antitrust amendments, Congress included no limitation on

private fee contracts in Section 1988. In Crawford Fitting

Co. v. J.T. Gibbons, 482 U.S. 437 (1987), this Court held that

Congress had enacted 28 U.S.C. § 1821 as a limitation on the

amount of reimbursement a district court may award to a

prevailing party for expert witness fees. Thus, Justice Rehn-

quist aptly observed, “[i]t is . . . clear that when Congress

meant to set a limit on fees, it knew how to do so.” Id. at

442. Likewise, Congress unquestionably knew how to place

limits on the availability of fees under a private fee contract,

but it did not do so when it passed the Civil Rights Attorney’s

Fees Awards Act. Petitioners cannot now impute such limita

tion in the absence of an expression of clear congressional

intent.13

12 The Antitrust Civil Process Act Amendments, Pub. L. 94-

435, 90 Stat. 1394, 1395, 1396 (1976), as set forth in 15 U.S.C.

§§ 15b-h.

13 Moreover, had Congress intended to limit attorneys’ fees

under § 1988, it could have imposed a cap on fees as it has in

numerous other statutes. See, e.g.. Equal Access to Justice Act, 28

U.S.C. § 2412(d)(1)(A) ($75/hour in absence of special circum

stances); Federal Tort Claims Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2678 (fee limited to

20% of administrative settlement; 25% of judgment); Social Security

Act, 42 U.S.C. § 406(a) (fee limited to 25% of award); Coast Guard

Act, 14 U.S.C. § 431(c) ($10 maximum); International Claims

Settlement Act of 1949, e.g., 22 U.S.C. §§ 1623(f), 1631 (j), 1641(p),

1642(m), 1643(k) (10 percent maximum); American-Mexican

16

Even if reference is made to the legislative history of

Section 1988, it readily demonstrates that the primary pur

pose of the Fees Act was “the promotion of respect for civil

rights” rather than the imposition of limits on contract rights,

as Petitioner suggests. See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 94-1011, p.5

(1976); Evans v. JeffD., 475 U.S. 717, 731-32, 89 L. Ed. 2d

7 4 7 ,106S.Ct. 1531(1976). According to the chief proponents

of the legislation, the impetus for enacting the Fees Act was

to restore the status quo after the Supreme Court decided in

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S.

240 (1975) that attorneys’ fees could not be awarded in the

absence of a specific authorizing statute. See, e.g., Senate

Report No. 94-1011, pp. 1,4,5; House Report No. 94-1558,

pp. 2,3,9. The scant commentary cited by Petitioner as

criticism of attorneys seeking fees for their work pales in

comparison to the strong emphasis Congress placed on en

couraging meritorious civil rights actions.

Indeed, both the Senate and House Reports cited the

seminal Title VII case, Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express,

Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974), for the proposition that

the reasonableness of fee awards under § 1988 should be

determined in accordance with the 12 standards articulated

by the Johnson court. S. Rep. No. 94-1011, p.6 (1976); H.R.

Rep. No. 94-1558, p.8 (1976). It is noteworthy that among

the 12 factors for determining fee awards is “whether the fee

is fixed or contingent.” Johnson, supra, at 718 (emphasis

added). Thus, Congress was not only aware that attorneys

separately contract with their clients for fees on a contingency

basis but also affirmed its support for the practice.

[footnote 13 continued from page 15)

Chamizal Convention Act of 1964, 22 U.S.C. §277d-21 (10 percent

maximum); Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948,

50 U.S.C. App. § 1985 (10 percent maximum); Organic Act of

Guam, 48 U.S.C. § 1424c(f) (5 percent maximum); Military Person

nel and Civilian Employees Claims Act of 1964, as amended, 31

U.S.C. § 3721 (i) (10 percent maximum); Servicemen’s Group Life

Insurance Act, 38 U.S.C. § 784(g) (10 percent maximum).

17

Congress’ intent to add statutory fees to the then existing

fee incentives available to clients is also evidenced by refer

ence to the cases where the fee standards were “correctly

applied.” Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 893-4 (1984)

(quoting with approval from legislative history). In Stanford

Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974), plaintiffs

were able to obtain counsel through use of a lump sum

or “retainer” payment. The fee agreement provided that

plaintiffs would pay counsel “$5,000 plus whatever funds

they could raise from interested third parties.” Id. at 686.

Pursuant to this fee contract, counsel was paid $8,500. Id.

Similarly, in another case cited with approval by Con

gress, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. o f Education, 66

F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975), counsel for plaintiffs received

some payment of fees and costs from the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Id. at 486. The Court

specifically acknowledged the existence of the private fee

arrangement. Id.

If Congress had desired to regulate private fee agree

ments, it would have evidenced this intent by placing a dollar

amount limit or percentage “cap” on civil rights attorneys’

fees, as it has done in numerous other fee statutes.14 The

absence of these “supervisory” fee provisions in the Civil

Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act further demonstrates that

the statutory fee provision was not intended to abrogate

private arrangements negotiated by the client and his or her

attorney.

B. Enforcement of Respondent’s Fee Agreement Is Consistent

with Prior Supreme Court Rulings

In each of four recent decisions addressing issues arising

under fee shifting statutes, this Court has acknowledged the

14 See, e.g., 28 U.S.C. § 2412(d)(1)(A) (fee awards under Equal

Access to Justice Act limited to $75/hour in absence of special

circumstances); Federal-Tort Claims Act, 28 U.S.C. §2678 (fee

limited to 20% of administrative settlement; 25% of judgment or

settlement); Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. § 406(a) (fee limited to

25% of award).

18

viability of fee agreements privately negotiated by plaintiffs

and their attorneys. In Crawford Fining, the right to privately

contract for fees was preserved. In that case, the Court limited

reimbursement to a prevailing party for expert witnesses to

$30.00 per day. Accordingly, a federal court is bound by the

limits of §§ 1821 and 1920 “absent explicit statutory or

contractual authorization” Id. at 445 (emphasis added).

Likewise, in Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizen’s

Council, 483 U.S. 711 (1987) (“Delaware Valley i r ) , the

Court stated that “the fee contract between the client and his

attorney should be taken into account when determining the

reasonableness of a fee award . . . . ” Delaware Valley II, supra

at 723. In its discussion of the nature of § 1988, the Court

in Delaware Valley II also noted that, because a losing plaintiff

is entitled to no fees, his or her attorney will be paid nothing

unless “the attorney has an agreement with the client that the

attorney will be paid, win or lose” Id. at 715. Indeed, in

Delaware Valley II all nine Justices noted with approval the

availability of private fee contracts.15

In Blanchard v. Bergeron,____U.S______, 109 S.Ct. 939

(1989) this Court again reaffirmed the viability of private fee

agreements by holding that a district court cannot limit the

court awarded attorneys’ fees to an amount provided in a

contingent fee agreement. Thus, “a contingent fee agreement

is not a ceiling upon the fees recoverable under § 1988”, 109

S.Ct. at 946, and a private agreement may be a factor in

determining the reasonableness of court awarded fees. 109

S.Ct. at 944. However, Blanchard also makes it clear that a

prevailing party and his or her attorney can contractually

agree to a higher fee than the statutory award, and that will

not alter the losing party’s obligation to pay court-awarded

15 Justice O’Connor concurred in this portion (part II) of Justice

White’s plurality decision. Id. at 734 (O’Connor, J. concurring).

In addition. Justice Blaekmun recognized with approval the avail

ability of privately negotiated contingent fee contracts. Id. at 737

(Blaekmun, J. dissenting).

19

fees. 109 S.Ct. at 945. Thus, Petitioner’s dramatic appeal

to “balance the scales” by invalidating all fee agreements is

no more than empty rhetoric. Blanchard has, in fact, already

equalized the equation. Defendants in civil rights cases are

only liable for the amount of the statutory fee award, no more

no less, regardless of the private contract between client and

attorney.

Finally, although this Court did not directly address the

issue of fee agreements in Evans v. Jeff D„ 475 U.S. 717

(1986), implicit in its determination was an acknowledgement

of the practice of entering into private fee agreements.

Reviewing congressional intent, the Court observed, “[Con

gress] did not prevent the party from waiving this eligibility

[for attorneys’ fees] any more than it legislated against assign

ment of this right to an attorney-----” Id. at 730-31. The

Court added that while “Congress expected fee shifting to

attract competent counsel to represent citizens deprived of

their civil rights, it neither bestowed fee awards upon attorneys

nor rendered them non-waivable or non-negotiable". Id. at

731-32 (emphasis added). As such, if the right to statutory

fees can be used as “a bargaining chip” to negotiate an

advantageous settlement agreement, it would be an anoma

lous result to limit a prevailing attorney to statutory fees.

Surely, if a contract can be negotiated which allows the

plaintiff to waive statutory fees, a contract can be negotiated

which allows use of one of the time-honored means for

representation of clients with little or no financial resources—

the contingent fee agreement.

III.

EXPERIENCE UNDER SECTION 1988 COUNSELS

AGAINST INVALIDATING FEE CONTRACTS

The available evidence counsels against interpreting

§ 1988 to limit the recovery of fees pursuant to a private

20

contract. Despite judicial and popular perceptions to the

contrary, § 1988 has not attracted a mass of attorneys to bring

previously neglected civil rights actions. If the possibility of

fee awards attracted attorneys to constitutional tort litigation,

one would expect civil rights filings to increase after the

effective date of § 1988, October 1, 1976. Yet the most

comprehensive study of civil rights filings finds that, after

enactment of § 1988, there was a general nationwide decline

in general non-prisoner civil rights filings as a percentage of

all federal civil filings. Eisenberg & Schwab, The Reality o f

Constitutional Tort Litigation, 72 Cornell L. Rev. 641, 666

(1987) (Table III) [hereinafter referred to as Reality].'6

Table III from Reality compares the annual increase in

non-prisoner civil rights filings with the annual increase in

all federal civil filings from 1975 to 1984. The civil rights

category that encompasses most § 1983 and other civil rights

claims is Administrative Office Category number “440”,

which is labeled “other civil rights”.16 17 Table III reveals that,

between 1975 and 1984, this category declined as a fraction

16 Nothing in the unrefined, generalized statistical information

presented by Petitioner supports the total abandonment of the right

to contract. Petitioner’s raw data is precisely the type of generalized

information criticized by this Court in its recent decision in Wards

Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,___U.S_____, 109 S.Ct. 2115 (1989).

Unlike the data in the study relied upon herein, there is no basis

for eliminating from Petitioner’s material any of a number of

factors which could explain differences in filing statistics such as

changes in substantive law, societal attitudes about litigation in

general, or variations in workforce demographics. Any of these

factors could well explain the figures cited by Petitioner, and there

is no reason to extrapolate from that data the conclusion that

Petitioner’s figures are explained solely by court decisions regarding

contingent fee contracts.

17 This category excludes employment claims, most of which

are covered by their own fee statute which has been part of Title

VII since its enactment in 1964. The data for Table III come from

Administrative Office of the United States Courts, 1984 Annual

Report of the Director 145 (Table 25).

21

of the federal civil docket. Civil rights filings either remained

constant or decreased relative to all civil filings in all but two

years during the ten-year period and in only one of those two

years did the relative increase exceed five percentage points.

If § 1988 generated a spate of civil rights actions in the

decade after its enactment, they are undetectable through

observation.

Similar findings apply with respect to prisoner civil rights

litigation. Reality, 72 Cornell L. Rev. at 666-67 & Table

IV .18 Indeed, in the prisoner area there is evidence that

§ 1988 has provided insufficient incentives to attract private

counsel to meritorious prisoner claims. Schwab & Eisenberg,

Explaining Constitutional Tort Litigation: The Influence o f

The Attorneys Fees Statute and The Government as Defendant,

73 Cornell L. Rev. 719, 770-74 (1988).

It is true that the absolute level of civil rights filings

increased during the reported period. But, given the increase

in population and general litigation (as measured by the

increase in other civil filings), the absolute level of civil rights

filing activity is less persuasive evidence than the relative

level. If § 1988 were inducing lawyers to file civil rights cases

in extraordinary numbers, there should have been an increase

in both the absolute and relative level of civil rights filings.

18 Further evidence that § 1988 had modest effects on filings is

presented in Schwab & Eisenberg. Explaining Constitutional Tort

Litigation, 73 Cornell L. Rev. 719 (1988).

22

CONCLUSION

There exists an abundance of well-financed and experi

enced attorneys available to defend civil rights cases at guar

anteed hourly rates. The principal congressional objective

in providing for reasonable attorneys’ fees in civil rights

litigation, however, was to provide an incentive to competent

attorneys to accept these difficult but socially important cases

on behalf of plaintiffs. H.R. Rept. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong.

2d Sess. 6 (1976); S. Rep. 94-1001, 94th Cong. 2d Sess. 4

(1976). The purpose was not to provide mere representation

to plaintiffs, but representation by highly skilled attorneys

experienced in this complex area of law who are sufficiently

well-capitalized to be able to persevere through protracted

litigation. Former Judge Charles B. Renfrew captured this

purpose well:

Litigation in this area often involves extraordinarily

complex legal and factual issues that many attorneys

would simply be unable to handle successfully. The

important individual and societal issues at stake in such

litigation may not be adequately protected unless attor

neys possessing the requisite skills can be induced to take

Title VII cases. Many able attorneys, no doubt, are

willing to forego some financial rewards because of the

psychic satisfaction of advancing a cause in which they

believe. However, the enforcement of the rights guaran

teed by Title VII cannot be entrusted to such altruistic

motives. Lockheed Minority Solidarity Coalition v. Lock

heed Missiles & Space Co., 406 F. Supp. 828, 830 (N.D.

Cal. 1976)

23

The lofty congressional purposes of providing competent

representation for victims of civil rights abuses would be ill

served by the invalidation of the right to contract sought by

Petitioner. The interference with the economics of the legal

marketplace and the contract rights of the parties sought by

Petitioner should not be indulged by this Court.

Dated: December 15, 1989

Respectfully submitted,

G u y T. Saperstein

Mari Mayeda

D ale L. Brodsky

Saperstein & Seligman

505 Fourteenth Street,

Suite 1150

Oakland, CA 94612

415/763-9800

Atonio H ernandez

E. R ichard Larson

Mexican American Legal

D efense & Educational F und

634 South Spring St., 11th Fir.

Los Angeles, CA 90014

213/629-2512

T heordore Eisenberg

Cornell Law School

Myron Taylor Hall

Ithaca, NY 14853

607/255-6477

John A. Powell

A merican C ivil Liberties U nion

Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

213/944-9800

Paul Hoffman

American Civil Liberties

U nion Foundation Of

Southern California

633 So. Shatto Place

Los Angeles, CA 90005

213/487-1720

Attorneys for Amici

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

PROOF OF SERVICE

Case: Juan Francisco Venegas v. Michael R. Mitchell

U.S. S.Ct. No.: 88-1725

STATE OF CALIFORNIA )

) SS

COUNTY OF ALAMEDA )

I am a citizen of the United States and have an office

in the county aforesaid. I am over the age of eighteen years and

not a party to the within entitled action. My business address is

505 Fourteenth Street, Suite 1150, Oakland, CA 94612.

On December 16, 1989 I served the within:

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE SAPERSTEIN & SELIGMAN, CALIFORNIA

TRIAL LAWYERS ASSOCIATION, CALIFORNIA EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS

ASSOCIATION, PLAINTIFFS EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION,

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, EQUAL RIGHTS

ADVOCATES, CENTER FOR LAW IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST AND

PUBLIC ADVOCATES, INC.

by placing a true copy thereof enclosed in a sealed Federal

Express envelope with postage thereon fully prepaid, in a Federal

Express Depository at Oakland, California addressed as follows:

Michael Bromberg (3 copies)

Box 2112, Hampton Street

Sag Harbor, New York 11963

Charles A. Miller (2 copies)

Covington & Burling

1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

Michael R. Mitchell (1 copy)

4929 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 910

Los Angeles, CA 90010

by causing a true copy thereof to be transmitted via telecopier

to:

I, Wanda Ruth Smith, declare, under penalty of perjury,

that the foregoing is true and correct.

Executed on Decemb< >rnia.

Richard Mosk

1901 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 850

Los Angeles, CA 90067

Wanda Ruth Smith