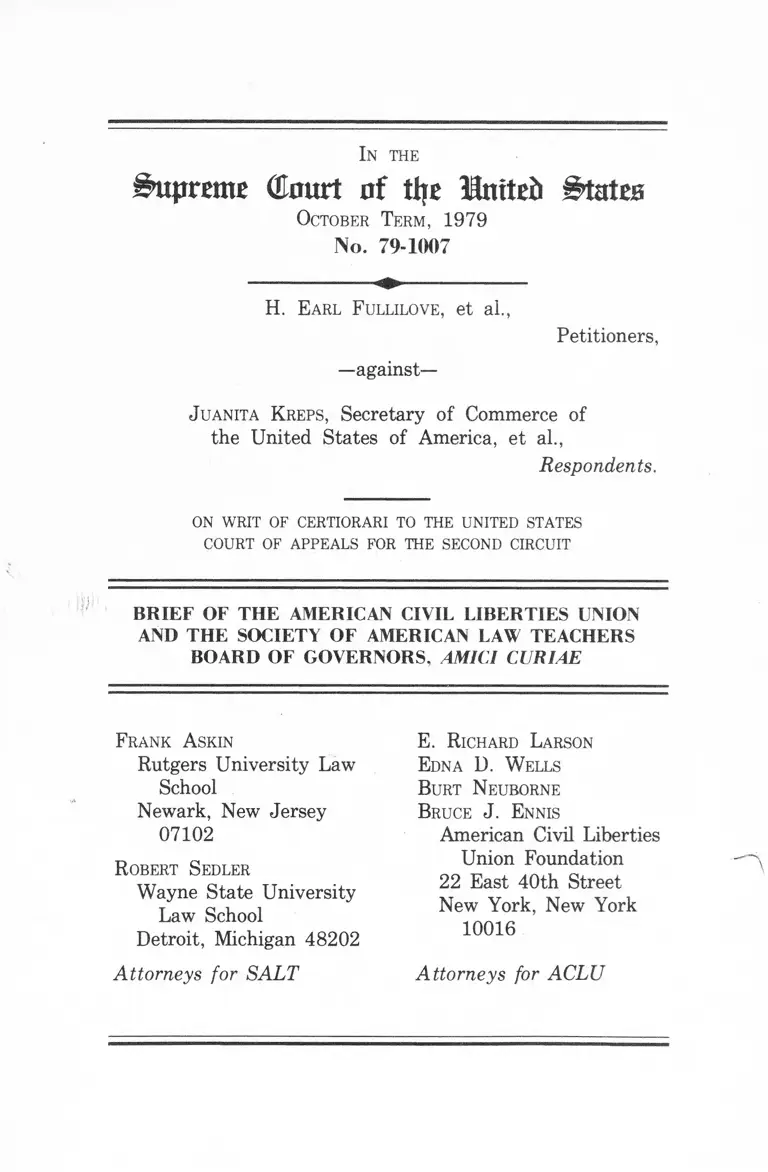

Fullilove v. Kreps Brief of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Society of American Law Teachers Board of Governors, Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 8, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fullilove v. Kreps Brief of the American Civil Liberties Union and the Society of American Law Teachers Board of Governors, Amici Curiae, 1979. 49be6b78-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cf9ba37b-b972-4b17-880b-442b1dc707ea/fullilove-v-kreps-brief-of-the-american-civil-liberties-union-and-the-society-of-american-law-teachers-board-of-governors-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Supreme Court of ttjc United States

October Term, 1979

No. 79-1007

H. Earl F ullilove, e t a l ,

—against—

Petitioners,

J uanita Kreps, Secretary of Commerce of

the United States of America, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

AND THE SOCIETY OF AMERICAN LAW TEACHERS

BOARD OF GOVERNORS, AMICI CURIAE

Frank A skin

Rutgers University Law

School

Newark, New Jersey

07102

Robert S edler

Wayne State University

Law School

Detroit, Michigan 48202

Attorneys for SALT

E. Richard Larson

Edna D. W ells

B urt N euborne

B ruce J. Ennis

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

22 East 40th Street

New York, New York

10016

Attorneys for ACLU

T A B L E OF C O N T E N T S

P a g e

Interest of the A m i c i .............1

Statement of the C a s e .............8

1. The Background of

Minority Business

Enterprise Programs. . . . 12

2. The Background of

Government Contracting . .22

3. The Enactment of the

MBE Ten Percent Set

A s i d e ................... 26

Summary of Argument.................39

Argument ....................... 4 7

I. THE MBE TEN PERCENT SET ASIDE

IS CONSISTENT WITH TITLE VI

AND LAWFUL IN VIEW OF THE

CONTROLLING PRINCIPLE THAT

SUBSEQUENT SPECIFIC CONGRES

SIONAL ENACTMENTS PREVAIL

OVER PRIOR GENERAL ONES. . . . 50

II. THE MBE TEN PERCENT SET

ASIDE, WHICH HAS NEITHER A

DISCRIMINATORY EFFECT NOR A

DISCRIMINATORY PURPOSE, IS

CONSTITUTIONAL UNDER THE

STANDARDS APPLIED IN UNITED

JEWISH ORGANIZATIONS BY

JUSTICES WHITE, STEVENS AND

REHNQUIST, AND BY JUSTICES

STEWART AND POWELL ........ 59

P a g e

III. THE MBE TEN PERCENT SET ASIDE

ALSO IS CONSTITUTIONAL UNDER

THE INTERMEDIATE STANDARD OF

REVIEW APPLIED IN BAKKE BY

JUSTICES BRENNAN, WHITE,

MARSHALL AND BLACKMUN . . . . 68

A. Because the MBE Ten

Percent Set Aside Is

Similar in Formulation

and Purpose to the

Sixteen Percent Special

Admissions Program at

Issue in Bakke, the

Intermediate Standard

of Review Is Applicable

Here ...................... 69

B. The Intermediate Standard

of Review Also Is Applic

able because— as Justice

Powell Pointed Out in

Bakke— the Racial Classi

fication Here Is Premised

upon Congressional Find

ings of Severe Minority

Underrepresentation in

Government Contracting . . 72

C. The MBE Ten Percent Set

Aside Is Necessary To

Remedy Substantial and

Chronic Minority Under

representation in

Government Construction

Contracting, and It

Does Not Stigmatize Any

Group..................... 8 7

-11-

IV. EVEN IF THE STRICT SCRUTINY

STANDARD OF REVIEW WERE

APPLICABLE, THE MBE TEN

PERCENT SET ASIDE STILL

WOULD BE CONSTITUTIONAL . . . . 94

A. Under the Standards

Applied by Justice

Powell in Bakke,

Congress Is both Author

ized and Competent To

Find Minority Underrep

resentation in Government

Contracting and To Devise

a Remedy for that Under

representation ...........94

B. The MBE Ten Percent Set

Aside Furthers a Compel

ling Governmental Purpose

and No Less Restrictive

Alternative Is Available . 103

CONCLUSION..........................112

P a g e

Cases

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

A. J. Raisch Paving Co. v. Kreps,

No. 77-3977 (N.D.Cal. Dec. 15,

1977) .......................... 48

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429

U.S. 252 (1977)..................... 59

-iii-

Associated General Contractors

of America, Inc. Alaska Chapter

v. Kreps, No. F78-1 (D.Alas.

Oct. 10, 1 9 7 8 ) ..................... 48

Associated General Contractors of

California v. Secretary of

Commerce, 441 F.Supp. 955 (C.D.

Cal. 1977) 49

Associated General Contractors

of Kansas v. Secretary of Commerce,

No. C.A. 77-4218 (D.Kan. Feb. 9,

1978) 48

Associated General Contractors of

Massachusetts v. Altshuler, 490

F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert.

denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974) . . . passim

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v.

Bridgeport Civil Service Commission,

482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir. 1973) . . . . 74

Buckner v. Goodyear, 339 F.Supp.

1108 (N.D.Ala. 1972), aff1d,without

opinion, 429 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir.

1973) 28

Bulova Watch Co. v. U.S., 365

U.S. 753 (1961) 57

Califano v. Webster, 430 U.S.

313 (1977)........... 43, 96, 100, 101

Carolinas Branch, Associated

General Contractors of America

v. Kreps, No. CA.M-77-165 (W.D.

Mich. Jan 4, 1 9 7 8 ) ................. 49

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315

(8th Cir.), modified on rehearing

en banc, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir.),

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972)

- iv-

74

passim

Contractors Association of

Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of Labor

442 F.2d 149 (3d Cir.), cert.

denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) . . .

Constructors Association of

Western Pa. v. Kreps, 573 F.2d

811 (3rd Cir. 1978) ........... 48

Florida East Coast Chapter,

Associated General Contractors

of America v. Secretary of Commerce,

No. C.A. 77-8351 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 3,

1977) .......................... 49

Fullilove v. Kreps, 584 F. 2d 600

(2d. Cir. 1978)................. 5, 48

Frank Coluccio Construction Co. v.

Kreps, No. F78-9-Civ.(D. Alas.

Oct. 5, 1 9 7 8 ) ................... 48

General Building Contractors

Ass'n v. Kreps No C.A. 77-3682

E.D. Pa Dec. 9, 1977)........... 49

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S.

88 (1976)............... 43, 96, 97, 98,99

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United

States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964)........... 105

Indiana Constructors, Inc., v.

Kreps, No. IP 77-602-c (S.D. Inc.

Jan. 4 , 19 7 9 ) ......................... 48

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392

U.S. 409 (1968)................. 105

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S.

641 (1966)........... 44 , 82, 84 , 105, 64

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974). • .105

- v-

Local 53 of International

Association of Heat & Frost,

etc. v. Voglen 407 F. 2d 1047

(5th cir. 1969) .............. 28

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39

(1971).................................60

Montana Contractors Association

v. Secretary of Commerce, 460 F.

Supp. 1174 (D. Mont. 1979).......... 49

Morten v. Mancari, 417

U.S. 535 (1974).................. 56, 57

North Carolina Board of Education

v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971)........ 60

Ohio Contractors Association v.

Economic Development Administration,

580 F . 2d 213 (6 Cir. 1 9 7 8 ) ......... 4 8

Palmer v, Thompson, 4 03 U.S.

217 (1971)..................... 42 , 59

Radzanower v, Touche Ross & Co.

et.al. 426 U.S. 148 (1976) . . . . . 57

Regents of the University of

California v, Bakke, 438 U.S. 265

(1978) .......................... passim

Rhode Island Chapter, Associated

General Contractors of America v.

Kreps, 450 F. Supp 338 (D.R.I.

1978) ................................

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301 ( 1966) . . . 44, 76, 82, 83, 105

Southern Illinois Builders

Association v. Ogilve, 47 F. 2d

159 (3d cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ................. 28

- vi -

Tennessee' Valley Authority v.

Hill, 437 U.S. 153 ......... . 56,58

United Jewish Oraanizations v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) . . . passim

United States v International

Union of Elevator Contractors,

538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir. 1976) . . .

United Steelworkers of America v.

Weber, 61 L. Ed 2d 480

28

(1979) .......................... passim

Virginia Chapter, Associated

General Contractors of America, Inc.

v. Kreps, 444 F. Supp. 1167 (WO

Va 1978)..........................

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976) ................. 42, 61

Wright Farms Construction, Inc. v.

Kreps 444 F. Supp.-1023 (D. Vt.

1977) ............................

STATUTES

Local Public Works Capital

Development and Investment Act of

1976, Pub. L. No. 94-369, 90

Stat. 999, 42 U.S.C. §§6701,

et seq ............................ oLOC

O

Public Works Employment Act of

1977, Pub. L. No. 95-28, 9 Stat.

116, 42 U.S.C. §§670], et seq.,

as amended .....................

- vi i -

passim

20, 21

Railroad Revitalization and

Regulatory Reform Act of 1976,

Pub. L. No. 94-212, 90 Stat. 31,

49 U.S.C. §1657a, et seq . . . .

Small Business Act of 1953, Pub. L.

No. 83-163 (July 30, 1953), 67

Stat. 232 ..........................

Small Business Act, Pub. L. No.

85-536 (July 18, 1968), 72 Stat.

384, 15 U.S.C. §631, et seq. . .

Small Business Act Amendments of

1974, Pub. L. No. 93-386, 88

Stat. 742 ........................

Small Business Act Amendments of

1976, Pub. L. No. 94-305, 90

Stat. 667 ........................

State and Local Fiscal Assistance

Act of 1972, §122, 31 U.S.C.

§§]242 ..........................

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000d . . . .

Executive Orders

Executive Order 11458, 3 C.F.R.

109, 34 Fed. Reg. 4937 (March 5,

1969) ............................

Executive Order 11518, 3 C.F.R.

109, 35 Fed. Reg. 4938 (March 21,

1 9 7 0 ) ..................... ..

Executive Order 11625, 3 C.F.R.

213, 36 Fed. Reg. 19967 (Oct. 13,

(1971)................... 15, 16

-viii-

12

13,14,20

20

20

10

passim

14,102

15, 102

, 17, 102

Regulations

13 C.F.R. §124.8-1, 31 Fed.

Reg. 13729 (May 25, 1 9 7 3 ) ........... 17

49 C.F.R. §265. 12a

265. 13b (5)

265. 13c (3) v i ........... 21

Legislative History

123 Cong. Rec. H.1436 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1 9 7 7 ) ................. passim

123 Cong. Rec. H.1437 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1 9 7 7 ) ................. passim

123 Cong. Rec. H.1438 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1 9 7 7 ) ................. 32

123 Cong. Rec. H.1440 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1 9 7 7 ) ................. passim

123 Cong. Rec. H.1441 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1977) 38

123 Cong. Rec. H. 3920-3935 (daily

ed. May 3, 1 9 7 7 ) ................. 38

123 Cong. Rec. S. 3910 (daily ed.

March 10, 1977 ................... passim

123 Cong. Rec. S. 3920 (daily ed.

March 10, 1 9 7 7 ) ............... 38, 41, 42

123 Cong. Rec. S.6755-6757 (daily

ed. April 29, 1 9 7 7 ) ............... 38

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 95-230, 85th

Cong., 1st Sess. 9 (April 28, 1977)

(reprinted in U.S. Cong. & Adm.

News 168 (1977) ) ................... 38

-lx-

Other Authorities

Bureau of Labor Statistics,

Employment and Earnings, 143

(Jan. 1 9 7 8 ) ............................ 8

Committee on Samll Business,

Summary of the Activities, House

of Representatives, 94th Congress

(1977)................................ 109

Department of Commerce, A New

Strategy for Minority Business

Enterprise Development, at 4

(April 1 9 7 9 ) ............ 22

Brief of the ACLU and SALT, amici

curiae, at 75-89, filed in United

Steelworkers of America v Weber,

61 L. Ed. 2d 480 (1979)............. 27

GAO Report to Congress: Questionable

Effectiveness of the 8(a) Procurement

Program 32 (April 1975) . . . . . . 19

............. 19,85

Marshall, R. & Briggs v The

Negro and Apprenticeship (1967) . . . . 28

Marshall "The Negro in Southern

Unions", in the Negro and the American

Labor Movement (ed. Jacobson, Anchor

(1968).............................. 28

Myrdal, G. An American Dilemma

1079-1124 (1944) 21

Sedler, "Beyond Bakke: The Constitu

tion and Redressing the Social History

of Racism", 14 Harv. Civ. Rights--

Civ. Lib. L. Rev. 133 (1979)........ 88

-x-

Spero, S. and Harris A.

The Black Worker (1931)............. 28

United States Commission on

Civil Rights Employment 97

(1961)................... . .......... 28

United States Commission on Civil

Rights Report, Minorities and

Women as Government Contractors

(May 1975) ........................ passim

United States Commission on Civil

Rights, State Advisory Committee

50 States Report 209 (1961) . . . . 28

United States Commission on Civil

Rights, The Challenge Ahead: Equal

Opportunity in Referral Unions 58-94

(1976).............................. 28

-xi -

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1979

NO. 78-1007

H. EARL FULLILOVE, et al.,

Petitioners,

against

JUANITA KREPS, Secretary of Commerce of the

United States of America, et al.,

Respondents,

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States court

of A ppeals f o r the Seco nd cir cuit

BRIEF OF THE

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

AND THE SOCIETY OF AMERICAN LAW TEACHERS

BOARD OF GOVERNORS, AMICI CURIAE

Interest of the Amici*

The American Civil Liberties Union

for 59 years has devoted itself exclu

sively to protecting the fundamental

* The parties have consented to the filing of

this brief and their letters of consent have

been filed with the Clerk of the Court pursuant

to Rule 42(2) of the Rules of this Court.

-1-

rights of the people of the United

States.

For nearly a decade, the governing

board of our 200,000-member national

organization has vigorously debated the

issue of "numerically based affirmative

action." The intensity and vigor of our

discussions have heightened the ACLU's

realization that the major civil liber

ties issue still facing the United

States is the elimination, root and

branch, of all vestiges of racism. No

other right surpasses the wholly

justified demand of the nation's

discrete and insular minorities for

access to the American mainstream from

which they have so long been excluded.

In recognition of this right, the

ACLU in 1973 adopted the following

policy:

"The root concept of the principle

of non-discrimination is that

individuals should be treated

individually, in accordance with

their personal merits, achievements

and potential, and not on the basis

of the supposed attributes of any

class or caste with which they

may be identified. However, when

discrimination— and particularly

-2-

when discrimination in employment

and education— has been long and

widely practiced against a

particular class, it cannot be

satisfactorily eliminated merely

by the prospective adoption of

neutral, 'color-blind' standards

for selection among the applicants

for available jobs or educational

programs. Affirmative action is

required to overcome the handicaps

imposed by past discrimination of

this sort; and, at the present time,

affirmative action is especially

demanded to increase the employment

and the educational opportunities

of racial minorities."

Pursuant to this policy, the ACLU,

amicus curiae, filed a brief in this

Court supporting the constitutionality

and legality of the sixteen percent set

aside for disadvantaged minorities in

the race conscious admissions program at

issue in Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

The ACLU and SALT, amici curiae, also

filed a brief in this Court supporting the

legality of the numerical goals, ratios

and timetables in the race conscious

on-the-job training program at issue in

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

61 L.Ed.2d 480 (1979) .

-3-

Subsequent to this Court's decision

in Bakke, the ACLU's governing board

again debated the appropriateness of

numerically based affirmative action.

As a result of these debates, our

governing board in March 1979 "reaf

firm [ed] the continuing need for

vigorous efforts to redress the adverse

effects of racism...in American society,

and encouraged the adoption of numerical

measures designed to remedy "current

disadvantage caused by discrimination,

whether specific or societal." Our

revised policy also states with approval

"As Justice Blackmun has recog

nized [in Bakke], 'In order to

get beyond racism, we must first

take account of race.... We

cannot— we dare not— let the

Equal Protection Clause

[perpetuate] racial supremacy.'

[438 U.S. at 407]"

The instant case, following on the

heels of Bakke and Weber, presents

another facet of affirmative action: a

race conscious law which sets aside ten

percent of the contracts in a new

government contracting program for

-4-

minority business enterprises. Premised

upon nearly a decade of special but

inadequate assistance for minority

business enterprises, and specifically

directed at alleviating the high unem

ployment rate in minority communities,

this congressional enactment is but one

more step necessary to get beyond racism.

The United States Court of Appeals

for the Second Circuit found this

congressional enactment constitutional.

Fullilove v. Kreps, 584 F„2d 600 (2d Cir.

1978) .

For the reasons expressed in this

brief, the ACLU urges this Court to

affirm that decision.

The Society of American Law Teachers

is a professional organization, formed

in 1973, of approximately 400 professors

of law at more than 120 law schools in

the United States. Among its stated

purposes is the encouragement of fuller

access of racial minorities to the legal

profession; since its inception the

Society has been active in supporting

the adoption and maintenance of special

- 5 -

minority admissions programs at American

law schools. Its position is that volun

tary affirmative action programs are

fully consistent with the requirements

of the Constitution of the United States

and federal laws designed to eradicate

racial dsicrimination. In accordance

with this position, it has filed an

amicus curiae brief, urging reversal, in

Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), and has

joined with the American Civil Liberties

Union in filing an amici curiae brief

urging reversal in United Steelworkers

of America v. Weber, 41 L.Ed.2d 480 (1979) .

Like the affirmative action programs

involved in Bakke and in Weber, the MBE

ten percent set aside involved in the

present case represents an affirmative

effort, this time by the federal govern

ment, to end the historic exclusion of

blacks and other racial minorities from

the American mainstream. If true racial

equality is ever to be achieved in this

Nation, it is imperative that such affir

mative efforts be upheld by this Court.

For these reasons, the Society of

-6

American Law Teachers joins the ACLU in

this brief, urging this Court to affirm

the judgment of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and

to uphold the validity of the MBE ten

percent set aside.

-7-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In 1976, the national unemployment

rate was 7.7%, with the nonwhite rate

nearly double at 13.1%.1 A year later,

there had been little improvement. The

national unemployment rate was 7.0%,

while the nonwhite rate remained at

13.1%.2

Congress, in the exercise of its

economic powers, sought to reduce these

high rates of unemployment and to

stimulate general economic recovery

from the lingering recession of several

years earlier. It did so, in part, by

enacting legislation authorizing

billions of dollars for state and local

government public works projects. One

such enactment was the Local Public

Works Capital Development and Investment

Act of 1976, Pub.L.No. 94-369 (July 22,

1976), 90 Stat. 999, 42 U.S.C. §§6701,

et seq. In that Act, Congress authorized

1. U.S. Dept, of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statis

tics, Employment and Earnings, 143 (Jan. 1978) .

2. Id.

-8-

the Secretary of Commerce, acting

through the Economic Development

Administration, to distribute two

billion dollars to state and local

governments for local public works

construction projects. 42 U.S.C.

§§6701, 6702, 6710. As part of the

Act, Congress established priorities

and preferences for state and local

governments in jurisdictions with

particularly high unemployment rates

and directed that grants should provide

employment for unemployed persons in

those jurisdictions. 42 U.S.C. §6707.

Congress also incorporated into the Act

a nondiscrimination provision similar

to that of Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 and directed that it be en

forced in a manner similar to that which

is used to enforce Title VI. 42 U.S.C.

§6727. Finally, Congress directed that

the two billion dollar authorization be

allocated and expended no later than

September 30, 1977. 42 U.S.C. §6710.

In the spring of 1977, Congress

recognized that its two billion dollar

authorization was insufficient to reduce

-9-

unemployment or to stimulate economic

recovery. It thus amended the law by

enacting the Public Works Employment Act

of 1977, Pub.L.No. 95-28 (May 13, 1977),

91 Stat. 116, 42 U.S.C. §§6701, et seq.,

as amended. The new Act increased the

overall authorization to six billion

dollars, 42 U.S.C. §6710, as amended;

altered the priorities and preferences

so as to increase the grants available

to local governments in jurisdictions

with particularly high rates of unem

ployment, 42 U.S.C. §6707, as amended;

encouraged the Secretary to award grants

to construction projects which would

result in energy conservation, id.;

changed the nondiscrimination enforce

ment provision from one paralleling

Title VI to one paralleling the manda

tory enforcement provisions in §122 of

the State and Local Fiscal Assistance

Act of 1972 ["the Revenue Sharing Act,"

31 U.S.C. §1242], 42 U.S.C. §6727, as

amended; and directed that no grants

be made to a state or local government

applicant unless the applicant assured

the Secretary that at least ten percent

-10-

of the amount of each grant would be

expended for minority business enter

prises, 42 U.S.C. §6705 (f) (2) .

The last amendment, the subject

of this litigation, provides as follows

"Except to the extent that the

Secretary determines otherwise, no

grant shall be made under this chapter

for any local public works project

unless the applicant gives satisfactory

assurance to the Secretary that at

least 10 per centum of the amount of

each grant shall be expended for

minority business enterprises. For

purposes of this paragraph, the term

'minority business enterprise' means

a business at least 50 per centum of

which is owned by minority group

members or, in case of a publicly

owned business, at least 51 per

centum of the stock of which is owned

by minority group members. For the

purposes of the preceding sentence,

minority group members are citizens

of the United States who are Negroes,

Spanish-speaking, Orientals, Indians,

Eskimos, and Aleuts." Id.

This amendment, generally referred to

as the "MBE [Minority Business Enter

prise] ten percent set aside," was

authored by Representative Parren J.

Mitchell, who, at that time, was Chair

man of the Subcommittee on Domestic

Monetary Policy of the House Committee

on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs;

and Chairman of the Task Force on Human

Resources of the House Committee on the

Budget.

The amendment reflected a decade

of experience by Congress and by the

Executive Branch with providing economic

and business assistance to minority

business enterprises.

1. The Background of

Minority Business

Enterprise Programs

The preference in §103(f)(2) of

the Public Works Employment Act of 1977,

42 U.S.C. §6705(f)(2), for Minority

Business Enterprises did not originate

with that law. Rather, it derives from

a compendium of federal laws, federal

regulations, and Executive Orders which

together comprise the Minority Business

Enterprise Program.

The origin of the MBE Program dates

back to the enactment of the Small

Business Act of 1953, Pub.L.No. 83-163

(July 30, 1953), 67 Stat. 232, an Act

-12-

which was replaced in 1958 by a new law

known as "the Small Business Act," Pub.

L.No. 85-536 (July 18, 1968), 72 Stat.

384. Amended at various times since

then, the Small Business Act currently

is codified at 15 U.S.C. §§631, et seq.

The evident purpose of the Small

Business Act was to strengthen the

economic position of small businesses,

especially those businesses located in

areas with high unemployment and with

high proportions of low income individ

uals. 15 U.S.C. §631(b). In order to

effectuate these objectives, Congress

created the Small Business Administra

tion ["SBA"], and directed that it be

"under the general direction and super

vision of the President." 15 U.S.C.

§633(a). Under this direction and

supervision, the SBA was authorized to

make loans, guarantee loans, and provide

for technical assistance to small busi

nesses. 15 U.S.C. §636. Most signifi

cantly, under what is known as the

Section 8 (a) Program, the SBA was

empowered to enter into procurement

contracts with federal agencies and to

-13-

arrange for the performance of such

contracts by letting subcontracts to

small business enterprises. 15 U.S.C.

§637(a).

Despite the beneficent purposes of

the Small Business Act, the SBA was

unexpectedly inactive for the first

fifteen years of its existence.

Virtually no aid of any significance

flowed from the SBA to any small

businessesfmuch less to minority

business enterprises.

In 1969, the SBA was awakened from

its slumber. Acting under the authority

granted by 15 U.S.C. §633(a), President

Richard Nixon issued Executive Order

11458, 3 C.F.R. 109, 34 Fed.Reg. 4937

(March 5, 1969). With that Executive

Order, the Minority Business Enterprise

Program was formally established. The

Order created within the SBA the Office

of Minority Business Enterprise ["OMBE"]

and further created a President's 3

3. See generally, United States Commission on

Civil Rights Report, Minorities and Women as

Government Contractors, 29 n.54, 35 (May 1975).

-14-

Advisory Council for Minority Enterprise.

The explicit purpose of the Executive

Order was to rejuvenate the Section 8(a)

Program so as to award procurement

subcontracts to minority business enter

prises .

A year later, President Nixon

supplemented the foregoing Order with

Executive Order 11518, 3 C.F.R. 109, 35

Fed.Reg. 4939 (March 21, 1970). That

Order directed all federal departments

and agencies to increase the proportion

of procurement contracts to small

businesses, especially to minority

business enterprises.

In 1971, President Nixon superseded

the old Orders with Executive Order

11625, 3 C.F.R. 213, 36 Fed.Reg. 19967

(Oct. 13, 1971). Titled as a "National

Program for Minority Business Enterprise,"

the Executive Order was premised upon

the recognition that the OMBE had

"facilitated the strengthening and

expansion of our minority enterprise

program" but that it was necessary to

make better use "of resources and

opportunities in the minority enterprise

-15-

field" by authorizing the Secretary of

Commerce "to implement Federal policy

in support of the minority business

enterprise program" and "to coordinate

the participation of all federal

departments and agencies in an increased

minority enterprise effort." Id. The Execu

tive Order indeed sought to accomplish

such a national program. Section 1 of

the Order required the Secretary to

coordinate all federal, state, local

and private efforts to strengthen

minority business enterprises; Section

2 continued the existence of the

Advisory Council for Minority Enterprise;

Section 3 directed all federal depart

ments and agencies to cooperate with

the Secretary and to foster and promote

minority business enterprises; and

Section 5 authorized the Secretary to

take all steps necessary to achieve

the purposes of the Order. In Section

6 of the Order, "minority business

enterprise" was formally defined:

" 'Minority business enterprise

means a business enterprise that is

owned or controlled by one or more

-16-

socially or economically disadvantaged

persons. Such disadvantage may arise

from cultural, racial, chronic economic

circumstances or background or other

similar cause. Such persons include,

but are not limited to, Negroes,

Puerto Ricans, Spanish-speaking

Americans, American Indians, Eskimos,

and Aleuts." Id.

The foregoing definition of

"minority business enterprise" was

reiterated and further refined in new

regulations issued by the SBA under its

Section 8(a) Program. The pertinent

regulation, 13 C.F.R. §124.8-1, 31 Fed.

Reg. 13729 (May 25, 1973), provides in

part:

"(b) Purpose. It is the policy

of SBA to use such authority to assist

small business concerns owned and

controlled by socially or economically

disadvantaged persons to achieve a

competitive position in the market

place.

"(c) Eligibility.— (1) Social or

economic disadvantage. An applicant

concern must be owned and controlled

by one or more persons who have been

deprived of the opportunity to

develop and maintain a competitive

position in the economy because of

social or economic disadvantage.

Such disadvantage may arise from

-17-

cultural, social, chronic economic

circumstances or background, or other

similar cause. Such persons include,

but are not limited to, black Ameri

cans, American Indians, Spanish-

Americans, Oriental Americans,

Eskimos, and Aleuts. Vietnam-era

service in the Armed Forces may be a

contributing factor in establishing

social or economic disadvantage.

"(2) Ownership and control. Dis

advantaged persons must presently own

and control the concern except where

a divestiture agreement or management

contract, approved by the Associate

Administrator for Procurement and

Management Assistance, temporarily

vests ownership or control in non-

disadvantaged persons.

"(i) Proprietorships. An appli

cant concern may be a proprietorship.

"(ii) Partnerships. The ownership

of at least a 50-percent interest in

the partnership by disadvantaged

persons will create a rebuttable pre

sumption of ownership and control.

" (iii) Corporations. The owner

ship of at least 51 percent of each

class of voting stock by disadvantaged

persons will create a rebuttable

presumption of ownership and control." Id.

No longer allowed to remain dormant,

the SBA, acting through the OMBE, revived

the Section 8(a) Program and began to

award government procurement subcontracts

to minority business enterprises. In

-18-

Fiscal Year I"FY"] 1968, for example,

the SBA had awarded only 8 contracts

totaling approximately $10.5 million to

MBEs. In FY 1972, the SBA had increased

its efforts by awarding 1720 contracts

totaling more than $153 million to MBEs.

Despite this dramatic increase, the

procurement contracts awarded to minority

firms under the Section 8(a) Program

nonetheless were relatively minimal.

In FY 1972, these contracts represented

less than 0.3 percent of the total $57.5

billion of federal procurement.^

In the years subsequent to its

establishment, the MBE Program was of

course subjected to periodic review

inside and outside Congress. In

several reports to Congress, the MBE

Program was praised as necessary and

yet criticized as insufficient. In

response, Congress continued the MBE 4 5

4. id. at 41.

5. See, e.g., House Comm, on Small Business,

Summary of Activities, H.R. No. 94-1791, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1977); GAO Report to Congress:

Questionable Effectiveness of the 8(a) Procure

ment Program 32 (April 1975).

-19-

Program. And although the Small Business

Act was amended on several occasions in

the early 1970s,6 Congress kept the

Section 8(a) Program intact.

The use of race conscious programs to

assist minority business enterprises has not

been limited to the SBA. They also have

been adopted by Congress, for example,

as part of the Railroad Revitalization

& Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, Pub.L.

No. 94-212 (Feb. 5, 1976), 90 Stat. 31,

49 U.S.C. §1657a. Under the Revitalization

Act, as amended, Congress authorized the

6. The Small Business Act Amendments of 1974,

Pub.L.No. 93-386, 88 Stat. 742, increased the

loan, guaranty, and investment ceilings of the

Agency.

The Small Business Act Amendments of 1976,

Pub.L.No. 94-305, 90 Stat. 667, established the

Office of Export Development; aided the procure

ment of equipment to meet government pollution

control standards; made changes in corporate

securities requirements; provided for investment

guarantees; assumed jurisdiction over unincor

porated investment companies; repealed limita

tions on bank investment; provided for loans

for plant acquisition; increased the amount

available for economic opportunity loans, local

development company loans, and regular business

loans; and established the National Commission

on Small Business in America.

-20-

establishment of a race-conscious admin

istrative body, "The Minority Resource

Center," whose specific and sole function

was to assist and to encourage minority

business enterprises. 49 U.S.C. §1657a

(e). Thus, the Minority Resource Center

was empowered to "enter into such con

tracts , cooperative agreements, or

other transactions as may be necessary

in the conduct of its functions and

duties." 49 U.S.C. §1657a(e).

The federal regulations promulgated

under the Act require detailed affirma

tive action programs to be established

to guarantee employment and contractual

opportunities. Specific goals and time

tables must be established to hire

minority employees in proportion to

their percentage in the work force of

the contracting area where prior under

utilization of minority employees renders

such establishment appropriate. 49

C.F.R. 265.13b (5) . A similar provision

for specific goals and timetables exists

for minority businesses. 49 C.F.R.

265.13c(3)vi.

Overall, both Congress and the

-21-

Executive acted on numerous occasions

prior to 1977 to strengthen minority

business enterprises with the intent of

increasing their share of government

contracts. But the efforts fell far

short of altering governmental exclusion

of minority business enterprises from

receipt of government contracts.

2. The Background of

Government Contracting

Despite the federal government's

Minority Business Enterprise Program,,

minority businesses have not fared well

under government contracting. In FY

1972, for example, only 0.7 percent of

all federal procurement contracts were

awarded to minority business enter-

7prises. (Approximately half of these

MBE contracts were awarded through the

OSBA's Section 8(a) Program. ) Since FY

1972, MBEs consistently have shared less

than one percent of all federal procure-

9ment contracting. 7 8 9

7. See note 3, supra, at 6.

8. Id.

9. U.S. Department of Commerce, A New Strategy for

Minority Business Enterprise Development, at 4

(April 1979). -22-

This exclusion of minority business

enterprises from government contracting

is not simply the result of open, compe

titive bidding. Indeed, most federal

procurement contracts are awarded not

through open, competitive bidding, but

through negotiation with competing firms,

and through "sole source" negotiation

without competition. The latter methods

of awarding multi-million dollar con

tracts is justified by the government on

grounds of urgency, lack of competitors,

need for standardization, and other

factors.

Noncompetitive "sole source"

contracting accounts for a sizeable

portion of all federal contracts. It,

in fact, has been the primary means of

contracting used by such agencies as

the Department of Defense, the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration,

and the Department of Energy (formerly

the Atomic Energy Commission and the

Energy Research and Development Adminis

tration).^ Significantly, in FY 1972,

these three agencies alone accounted

for $43.2 billion or more than 70 per- 10

10. See note 3 supra, at 2, 6, 7.

-23-

cent of the $57.5 billion of federal

procurement contracts.^

Given the small size of most MBEs

and the relatively smaller size of

contracts awarded by state and local

governments, it might be expected that a

higher proportion of these contracts

would be awarded to MBEs. This should

be especially true since state and local

governments spend far more proportionately

than the federal government for construc

tion (approximately 40% by state and local

governments compared to less than 10% by

the federal government), and since a

disproportionately large percentage

(approximately 10%) of minority firms

1 nare small construction contractors.

Whatever the expectations may be,

state and local governments have been no

less exclusionary than the federal

government. In some instances, MBEs

have been totally excluded from state

and local contracting. For example,

during FY 1972, Denver's Department of

Public Works awarded more than $23 11 12

11. Id.

12. Id. at 9.

-24-

million in contracts but none went to

13minority businesses. California, which

has an annual procurement budget of $500

million, awarded merely $10,000 in con

tracts to minority enterprises in FY 1972

14and only $60,000 during FY 1973.

Overall, of the $62.5 billion spent

by state and local governments on goods

and services in the private sector in

1972, less than 0.7 percent of all con

tracting dollars were awarded to minority

.. 0 15firms.

This record, like the federal

government's record, is appalling in

itself. And it was no doubt

appalling to Congress, which had increased

federal aid to state and local governments

from $2 billion in FY 1950 to $45 billion

in FY 1974.13 14 15 16

13. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, note 3 supra,

at 95.

14. Id. at 97.

15. Id. at 95.

16. Id. at 89.

-25-

3. The Enactment of the MBE

Ten Percent Set Aside

When Congress in the spring of 1977

considered enactment o f the Public Works

Employment Act of 1977, it had before it

numerous reports summarizing the severe

underrepresentation of minority business

enterprises in federal, state and local

17government contracting. Congress knew,

for example, that the federal government

and state and local governments together

awarded more than 99% of all government

procurement contracts to white business

18enterprises. Congress also was aware

that SBA's Section 8(a) Program applied

only to federal procurement, and that

even there it had not been successful in

remedying the federal government's

historic exclusion of MBEs from federal

19contracting.

1 7 . See, e.g., U.S. Commission on Civil Rights

"Minorities and Women as Government Contractors"

(May 1975); GAO Report to Congress, "Questionable

Effectiveness of the 8(a) Procurement Program"

(April 1975).

18. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, supra, at vii.

19. GAO Report to Congress, supra, at 4.

-26-

Congress, like the courts, was also

aware that most government construction

contracts are awarded by state and local

governments, that most construction firms

are formed by entrepreneurs who are

skilled craft workers, and that the

extensive racial discrimination in the

building trades had prevented minority

workers not only from obtaining necessary

skills but also from forming their own

viable concerns. These latter conclusions

were known to Congress as evidenced by

its rejection of legislative efforts in

1969 and 1972 to eviscerate the affirma

tive action requirements imposed on the

construction industry by Executive Order

11246,20 and its own observations.

20. The 1969 and 1972 legislative history is

set forth in the Brief of the ACLU and SALT,

amici curiae, at 75-89, filed in United Steel

workers v. Weber, 61 L.Ed.2d 480 (1979).

21. In United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

61 L.Ed.2d 480 (1979), this Court took judicial

notice of the past discrimination in the con

struction industry, stating:

"Judicial findings of exclusion from

crafts on racial grounds are so numerous

as to make such exclusion a proper subject

for judicial notice. See, e.g., United

-27-

Aware of these conditions, Congress

in the early spring of 1977 focused on

legislation that could help to remedy

some of these past patterns: the Public * V.

States v. International Union of Elevator

Constructors, 538 F.2d 1012 (CA3 1976);

Associated General Contractors of Massa

chusetts v. Alshuler [sic], 490 F.2d 9

(CAl 1973); Southern Illinois Builders

Association v. Ogilve [sic], 471 F.2d 159

(CA3 1972); Contractors Association of

Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary of Labor,

442 F .2d 159 (CA3 1971); Local 53 of

International Association of Heat & Frost,

etc. v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (CA5 1969);

Buckner v. Goodyear, 339 F.Supp. 1108 (ND

Ala. 1972), aff'd without opinion, 476

F.2d 1287 (CA5 1973). See also United

States Commission on Civil Rights, The

Challenge Ahead: Equal Opportunity in

Referral Unions 58-94 (1976) (summarizing

judicial findings of discrimination by

craft unions); G. Myrdal, An American

Dilemma (1944) 1079-1124; R. Marshall and

V. Briggs, The Negro and Apprenticeship

(1967); S. Spero and A. Harris, The Black

Worker (1931); United States Commission on

Civil Rights, Employment 97 (1961); State

Advisory Committee, United States Commis

sion on Civil Rights, 50 States Report 209

(1961); Marshall, "The Negro in Southern

Unions," in The Negro and the American

Labor Movement (ed Jacobson, Anchor 1968)

p 145; App, 63, 104." 61 L.Ed.2d at 486

n.l.

-28-

Works Employment Act of 1977. Designed

to decrease unemployment and to speed

economic recovery, the Act authorized

the expenditure of $4 billion of new

federal money for state and local govern

ment construction projects. Construction,

of course, was the precise area where

minorities in the past had suffered such

egregious discrimination and where there

nonetheless existed a sizeable number of

minority businesses. Congress quite

plainly was confronted with a vehicle

which could remedy past patterns.

During the debates on H.R. 11, the

House version of the Public Works Employ

ment Act, Representative Mitchell offered

the MBE ten percent set aside as an amend

ment to the Act. 123 Cong.Rec. H.1436

(daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977). He observed

that it was consistent with the SBA and

OMBE programs, and otherwise explained

the amendment in considerable detail:

"I want to commend the chairman and the

members of the committee who have done a

great deal to make this public works bill

far more equitable than it was last year.

They have targeted and have amended the

legislation to cover areas of high unem

ployment and they have improved the

-29-

legislation so that it is a much better

bill. But there is one shortcoming that

I see in the bill that I am attempting to

address through my amendment. That short

coming is that there will be numerous con

tracts awarded at the local level for

various public works projects, but in that

there is no targeting— and I repeat— there

is no targeting for minority enterprises.

"Let me tell the Members how ridiculous it

is not to target for minority enterprises.

We spend a great deal of Federal money

under the SBA program creating, strength

ening and supporting minority businesses

and yet when it comes down to giving those

minority businesses a piece of the action,

the Federal Government is absolutely remiss.

All it does is say that, 'We will create

you on the one hand and, on the other hand,

we will deny you.1 That denial is made

absolutely clear when one looks at the

amount of contracts let in any given fiscal

year and then one looks at the percentage

of minority contracts. The average per

centage of minority contracts, of all

Government contracts, in any given fiscal

year, is 1 percent— 1 percent. That is

all we give them. On the other hand we

approve a budget for OMBE, we approve a

budget for the SBA and we approve other

budgets, to run those minority enterprises,

to make them become viable entities in our

system but then on the other hand we say

no, they are cut off from contracts.

"In the present legislation before us it

seems to me that we have an excellent

opportunity to begin to remedy this situ

ation.

-30-

"I know what the points in opposition will

be. The first point in opposition will be

that you cannot have a set-aside. Well,

Madam Chairman, we have been doing this

for the last 10 years in Government. The

8-A set aside under SBA has been tested in

the courts more than 30 times and has been

found to be legitimate and bona fide. We

are doing it in this bill. We are target

ing for the Indians, that is a set-aside.

All that I am asking is that we set aside

also for minority contractors.

"...That is because that is the only way

we are going to get the minority enter

prises into our system.

"...We cannot continue to hand out survival

support programs for the poor in this

country. We cannot continue that forever.

The only way we can put an end to that

kind of a program is through building a

viable minority business system. So, I

am deadly serious about it." 123 Cong.Rec.

H.1436-37 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977).

Subsequent to Mr. Mitchell's intro

duction of the MBE ten percent set aside,

the Committee of the Whole, for the most

part, debated neither the purposes of nor

the need for the amendment but rather its

effect in jurisdictions where there were

few or virtually no qualified minority

contractors. This issue was first raised

by Representative Abraham Kazen: "What

happens in the rural areas where there

-31-

are no minority enterprises?" Id. Rep

resentative Mitchell responded that the

amendment would not apply in those areas,

that administrative procedures to this

effect already were in operation under

the minority contracting program encom

passed in Executive Order 11246, and that

the Secretary of Commerce was assumed to

have a similar authority under the bill.

Id. Another Member, Representative

Robert Roe, Chairman of the Economic

Development Subcommittee of the House

Committee on Public Works and Transpor

tation, proposed that the "assumption"

be added to Representative Mitchell's

amendment by making the MBE ten percent

set aside non-mandatory through prefatory

language: "Except to the extent the

Secretary determines otherwise...." Id.

at 1438. After further discussion,

Representative Mitchell agreed: "I accept

the amendment to my amendment." Id.

Throughout the entire debate in the

House, no Member expressed any opposition

to the MBE ten percent set aside. All of

the commentary was favorable. Represen

tative John Conyers, for example, stated

-32-

that "minority contractors and business

men who are trying to enter in on the

bidding process... get the 'works' almost

every time. The sad fact of the matter

is that minority enterprises usually

lose out.... [Tjhrough no fault of

their own, [they] simply have not been

able to get their foot.in the door."

Id. at 1440.

Additional comments in support of

the MBE ten percent set aside were made

by Representative Mario Biaggi who

stressed the need to reduce the high

rate of unemployment among minority

workers and to remedy the exclusion of

minority enterprises from government

contracting:

"I rise to indicate my full support of the

amendment offered by my distinguished col

league from Maryland as amended by the

gentleman from New Jersey (Mr. Roe). I

consider the amendment wholly complementary

to the bill as its objective is to guaran

tee to minority business enterprises that

they too will benefit from the passage of

this legislation.

"This Nation's record with respect to pro

viding opportunities for minority businesses

is a sorry one. Unemployment among minority

groups is running as high as 35 percent.

Approximately 20 percent of minority busi

-33-

nesses have been disolved [sic] in a period

of economic recession. The consequences

have been felt in millions of minority

homes across the Nation.

"What the amendment seeks to do is guaran

tee that at least 10 percent of all funds

in this legislation will go to contracts

which will be awarded to minority business

enterprises. This is not an unreasonable

demand— in fact it is quite modest. If

implemented however it could have great

benefits to the entire minority community.

Fiscal year 1976 figures indicate that

less than 1 percent of all Federal procure

ment contracts went to minority business

enterprises. This is a situation which

must be [rjemedied.

"The objectives of this legislation are

both necessary and admirable. Yet without

adoption of this amendment, this legisla

tion may be potentially inequitable to

minority businesses and workers. It is

time that the thousands of minority busi

nessmen enjoyed a sense of economic parity.

This amendment will go a long way toward

helping to achieve this parity and more

importantly to promote a sense of economic

equality in this Nation." Id.

After additional debate, Representa

tive Mitchell's amendment was adopted on

a voice vote by the Committee of the

Whole. Id. at 1441.

The proceedings in the Senate on

the Public Works Employment Act paralleled

those in the House. Early in the debates

-34-

on S.427, the Senate version of H.R. 11,

Senator Edward Brooke offered an MBE ten

percent set aside amendment very similar

to that adopted by the House. 123 Cong.

Rec. S.3910 (daily ed., March 10, 1977).

Recognizing that the purpose of the

Act was to increase employment, Senator

Brooke focused on the severe unemployment

of members of racial and ethnic minori

ties. He stated that it was "important

that we focus on the unemployment

experiences of different ethnic and

racial groups in designing a sensitive

and responsive jobs program. For

example, among minority citizens, the

average rate of unemployment runs double

that among white citizens." Id.

Senator Brooke viewed the percentage

targeting concept as "entirely proper,

appropriate and necessary." Id.

"It is a proper concept, recognized for

example in this committee's bill which

set aside up to 2h percent for projects

requested by Indians or Alaska Native

villages. And, the Federal Government,

for the last 10 years in programs like

SBA's 8(a) set-asides, and the Railroad

Revitalization Act's minority resources

centers, to name a few, has accepted the

-35-

set aside concept as a legitimate tool to

insure participation by hitherto excluded

or unrepresented groups." Id.

Senator Brooke added that the set

aside also was appropriate:

"It is an appropriate concept, because

minority businesses' work forces are

principally drawn from residents of

communities with severe and chronic

unemployment. With more business, these

firms can hire even more minority citizens.

Only with a healthy, vital minority

business sector can we hope to make

dramatic strides in our fight against the

massive and chronic unemployment which

plagues minority communities throughout

this country." Id.

Finally, echoing Parren Mitchell's

observations, he noted that the program

was "necessary because minority businesses

have received only 1 percent of the

Federal contract dollar, despite repeated

legislation, Executive orders and regula

tions mandating affirmative efforts to

include minority contractors in the

Federal contracts pool." Id. Senator

Brooke then assuaged possible concerns

about the amendment:

"Many have expressed concern about

the impact of this amendment as a limita-

- 3 6 -

tion on contracting in areas where there

are few minorities. But this amendment

is not a limitation. Rather, it is

designed to facilitate greater equality

in contracting. This amendment provides

a rule-of-thumb which requires much more

than the vague 'good-faith efforts* lan

guage which currently hampers our efforts

to insure minority participation.

"One final objection to this set-

aside may be that it will cause undue

delays in beginning these vital public

works projects. In fact, EDA already

maintains a roster for each State of

capable and qualified minority enterprises

who are ready and willing to work. These

firms are capable of competitive bidding,

and need the financial support which this

potential level of Federal contracting

will guarantee." Id.

As in the House, no Member raised

any objection to the amendment. One

Senator, however, voiced concern about

the amendment. Senator John Durkin

questioned the application of the amend

ment to states with small minority popu

lations. Senator Brooke responded to

this concern by noting that the language

of his amendment insured the fair fund

ing of projects through wide discretion

22granted to the Secretary. Satisfied,

22. This language,which differs from that contained

in the House version, reads:

-37-

Senator Durkin asked one last question:

Mr. DURKIN. "May I be a co-sponsor?

Mr. BROOKE. "Yes.

Mr. PRESIDENT. "I ask unanimous consent

that the name of the distinguished

Senator from New Hampshire be added

as a co-sponsor.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. "Without objection,

it is so ordered." Id.

The majority and minority floor

managers, Senators Quentin Burdick and

Robert Stafford, agreed to accept the

amendment and it was adopted on a voice

vote. Id. The differences between the

House and Senate versions were resolved

in Conference, H.R. Conf.Rep. No. 95-230,

85th Cong., 1st Sess. at 9 (April 28,

1977); and the House version was enacted

as law, 123 Cong.Rec. S. 6755-6757 (daily

ed., April 29, 1977); 123 Cong.Rec. H.

3920-3935 (daily ed. May 3, 1977).

"This section shall not be interpreted

to defund projects with less than 10 percent

minority participation in areas with minority

population of less than 5 percent. In that

event, the correct level of minority parti

cipation will be predetermined by the Secretary

in consultation with EDA and based upon its

lists of qualified minority contractors and

its solicitation of competitive bids from

all minority firms on these lists." 123

Cong.Rec. S.3910 (daily ed. March 10, 1977).

- 3 8 -

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

When Congress enacted the Public

Works Employment Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C.

§§6701 , et seq. , it sought to alleviate

unemployment and to stimulate economic

recovery in the private sector by author

izing $4 billion in new federal monies

flowing to private contractors. Con

cerned about the especially high rate of

unemployment among minority workers,

aware of the inadequacy of past MBE

Programs, and determined to alter the

severe underrepresentation of minority

business enterprises in government

contracting. Congress targeted ten per

cent of the new federal monies for

minority business enterprises. 42

U.S.C. §6705(f)(2). In view of the

scope of the problems faced by Congress,

this ten percent target, as described by

Representative Mario Biaggi, was "not

unreasonable— in fact it is quite modest."

123 Cong.Rec. H. 1440 (daily ed. Feb.

24, 1977).

The ten percent set aside not only

is quite modest. It also is lawful under

- 3 9 -

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and constitutional under the equal pro

tection component of the Fifth Amendment.

1. The same Public Works Employment

Act that contains the ten percent set

aside, 42 U.S.C. §6705(f)(2), also con

tains a general nondiscrimination provi

sion stating that no person shall "on

the ground of race, color [or] national

origin...be excluded from participation

in, be denied the benefit of, or be sub

jected to discrimination under any pro

gram or activity...[which] receives funds

made available under this subchapter."

42 U.S.C. §6727(a). This language is

virtually identical to the ban against

discrimination found in Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000d.

Congress in 1977 quite obviously

saw no inconsistency between the ban on

discrimination and the Act's race con

scious ten percent set aside for minority

business enterprises. Whatever Title VI

may have meant when it was enacted in

1964, see Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978),

its ban on discrimination was viewed by

-40-

Congress in 1977 as. entirely consistent

with race, conscious set asides.

Even if the ten percent set aside

were viewed in isolation from the Act's

prohibition against racial discrimination

parallel to that in Title VI, the ten

percent set aside still would not violate

Title VI. To the extent that any two

legislative enactments conflict, it is

settled that the specific act later in

time controls the former general one.

Since the Public Works Employment Act of

1977 with its ten percent set aside was

enacted by Congress after Title VI had

been enacted, the ten percent set aside

is not and cannot be unlawful under

Title VI.

2. Among the unmistakeable pur

poses of the ten percent set aside, as

summarized by Senator Edward Brooke, was

the need to make "strides in our fight

against the massive and chronic unemploy

ment which plagues minority communities

throughout this country." 123 Cong.Rec.

- 4 1 -

S.3920 (daily ed. March 10, 1977). More

over, of crucial significance is the fact

that the entire Public Works Employment

Act was designed to fuel our economy by

pumping $4 billion of new federal money

into the coffers of private contractors.

Because of the legislative design of this

program, the ten percent set aside cannot

be found to have been premised upon a

racially discriminatory purpose. United

Jewish Organizations v . Carey, 430 U .S .

144 (1977); Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976). Additionally, because it was

a new program providing billions of dol

lars to white contractors, and because it

in no way fenced out white contractors

from receiving the lion's share of new

government contracts, the legislative

plan had no discriminatory impact upon

whites. United Jewish Organizations v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977); Palmer v .

Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971). "Having

failed to show that the legislative.,,

plan had either the purpose or the effect

of discriminating against them on the

basis of their race, the petitioners have

offered no basis for affording them the

- 4 2 -

Unitedconstitutional relief they seek."

Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S.

at 180 (concurring opinion of Stewart,

J. , with Powell, J.).

3. Even if this legislative plan

had a discriminatory purpose or effect,

the constitutionality of the ten percent

set aside would be determined under the

intermediate standard of review applicable

to racial classifications which have a

benign, compensatory purpose. Regents

of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265, 355-380 (1978) (opinion of

Brennan, J., with White, Marshall and

Blackmun, JJ.). Indeed, the strict

scrutiny standard of review is especially

inapplicable here because the ten percent

set aside is premised upon administrative

and legislative findings of severe minority

underrepresentation in government contract

ing, a problem which Congress is uniquely

capable of remedying. Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265, 300-310 (1978) (opinion of

Powell, J.); Califano v. Webster, 430

U.S. 313 (1977); Hampton v . Mow Sun Wong,

- 4 3 -

426 U.S. 88 (1976); Katzenbach v . Morgan,

384 U.S. 641 (1966); South Carolina v .

Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966).

Under the intermediate standard of

review, the ten percent set aside must

be sustained. As in Bakke, the race

conscious plan here serves the important

and articulated purpose "of remedying the

effects of past societal discrimination"

in a context where "there is a sound

basis for concluding that minority under

representation is substantial and chronic

438 U.S. at 362 (opinion of Brennan

J., with White, Marshall and Blackmun,

JJ.). It also serves the important and

articulated purposes of "building a

viable minority business system," 123

Cong.Rec, H. 1436-37 (daily ed. Feb. 24,

1977) (remarks of Rep. Mitchell); of

"promot[ing] a sense of economic equality

in this Nation," 'id. at 1440 (remarks of

Rep. Biaggi); of "facilitat[ing] greater

equality in contracting," 123 Cong.Rec.

S.3910 (daily ed. March 10, 1977)' (remarks

of Sen.Brooke); and, of course, of

fighting "the massive and chronic unemploy

ment which plagues minority communities

- 4 4 -

throughout this- country," Id. Finally,

as in Bakke, this race conscious plan

neither "stigmatizes any group [n]or...

singles out those least well represented

in the political process to bear the

brunt of [this] benign program." 438

U.S. at 361 (opinion of Brennan, J., with

White, Marshall and Blackmun, JJ.).

4. In view of the demonstrated

inadequacy of past and ongoing MBE Pro

grams to alter our government contracting

practices which award less than 1% of all

government contracts to minority business

enterprises, the ten percent set aside

would be sustained as constitutional even

under the strict scrutiny standard of

review. See Regents of the University

of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265,

305 (1978) (opinion of Powell, J.). As

Senator Brooke commented, the ten percent

set aside is "necessary because minority

businesses have received only 1 percent

of the Federal contract dollar, despite

repeated legislation, Executive Orders

and regulations mandating affirmative

efforts to include minority contractors

in the Federal contracts pool." 123

-45-

Cong.Rec. S.3910 (daily ed. March 10,

1977), The purposes of the race con

scious set aside unquestionably are

substantial and compelling; the set

aside is necessary to accomplish its

purposes; and no less restrictive

alternative is available.

- 4 6 -

ARGUMENT

Shortly after Congress made $4

billion of new contracting money

available to construction contractors,

reserving only ten percent for the eco

nomic recovery of minority business

enterprises, the MBE ten percent set

aside in §103 (f) (2) of the Public Works

Employment Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C.

§6705(f)(2), was roundly challenged in

lawsuit upon lawsuit by various state

and local chapters of the Associated

General Contractors of America, Inc.

The contractors' associations this time

were not concerned with having to employ

a few minority workers. To be sure,

they appreciated the federal largess.

Nonetheless, they wanted to receive the

same 99% to 100% of the contracts under

this new program in the same manner as 1

1. This concern is reflected in, e.g., Associ

ated General Contractors of Massachusetts v.

Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert,

denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974); Contractors Associ

ation of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of Labor, 442

F .2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971).

-47-

they had received 99% to 100% of all

construction contracts in the past.

In response to the challenges, the

lower federal courts, virtually without

exception, upheld the MBE ten percent

set aside as lawful and constitutional.

2. In addition to the court below, Fullilove

v. Kreps, 584 F.2d 600 (2d Cir. 1978), the only

other courts of appeals that have confronted the

MBE ten percent set aside have upheld it. Ohio

Contractors Association v. Economic Development

Administration, 580 F.2d 213 (6th Cir. 1978);

Constructors Association of Western Pa. v. Kreps,

573 F .2d 811 (3d Cir. 1978).

Eleven district courts have rejected chal

lenges to the statute. Cases upholding the

constitutionality of the challenged provision

are: Rhode Island Chapter, Associated General

Contractors of America v. Kreps, 450 F.Supp. 338

(D.R.I. 1978); Associated General Contractors of

Kansas v. Secretary of Commerce, No. C.A.77-4218

(D.Kan. Feb. 9, 1978); Indiana Constructors, Inc.,

v. Kreps, No.IP 77-602-C (S.D.Inc. Jan. 4, 1979);

Associated General Contractors of America, Inc.

Alaska Chapter v. Kreps, No. F78-1 (D.Alas. Oct.

10, 1978), appeal filed, No. 78-3421 (9th Cir.

Oct. 19, 1978); Frank Coluccio Construction Co.

v. Kreps, No. F78-9-Civ. (D.Alas. Oct. 5, 1978).

Decisions denying preliminary injunction

are: A.J. Raisch Paving Co. v. Kreps, No. 77-3977

(N.D.Cal. Dec. 15, 1977), appeal filed, No. 77-

2497 (9th Cir. Dec. 20, 1977); Florida East

Coast Chapter, Associated General Contractors of

America v. Secretary of Commerce, No. C.A.77-8351

-48-

Given the uniqueness of this legislation,

and in view of this Court's decision in

Regents of the University of California

v. Baklce, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), it is

apparent that the near unanimity among

the lower courts is correct. The MBE

ten percent set aside is consistent with

and lawful under Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, and it is constitu

tional under the Fifth Amendment.

(S.D.Fla. Nov. 3, 1977); General Building Con

tractors Ass'n v. Kreps, No. C.A.77-3682 (E.D.

Pa. Dec. 9, 1977); Virginia Chapter, Associated

General Contractors of America, Inc. v. Kreps,

444 F.Supp. 1167 (W.D.Va. 1978); Carolines

Branch, Associated General Contractors of

America v. Kreps, 442 F.Supp. 392 (D.S.C. 1977);

Michigan Chapter, Associated General Contractors

of America, Inc. v. Kreps, No. C.A.M-77-165 (W.

D.Mich. Jan. 4, 1978).

Three district courts have rendered deci

sions adverse to the constitutionality of the

statute: Wright Farms Construction, Inc. v.

Kreps, 444 F.Supp. 1023 (D.Vt. 1977) (unconsti

tutional as applied); Montana Contractors Asso

ciation v. Secretary of Commerce, 460 F.Supp.

1174 (D.Mont. 1979) (unconstitutional as applied)

Associated General Contractors of California v.

Secretary of Commerce, 441F.Supp. 955 (C.D.Cal.

1977) , vacated and remanded for determination of

mootness, 438 U.S. 909 (C.D.Cal. 1978), appeals

filed, Nos. 78-1107, 78-1108, 78-1114 (Nov. 17,

1978) (unconstitutional on its face) .

- 4 9 -

I. THE MBE TEN PERCENT SET ASIDE IS

CONSISTENT WITH TITLE VI AND LAWFUL

IN VIEW OF THE CONTROLLING PRINCIPLE

THAT SUBSEQUENT SPECIFIC CONGRES

SIONAL ENACTMENTS PREVAIL OVER PRIOR

GENERAL ONES ~

In Regents of the University of

California v. Bakke , 438 U.S. 265 (1978),

this Court was divided on the issue of

whether Title Vi's ban on racial discrim

ination prohibited a race conscious set

aside favoring racial minorities, The

Court's division in Bakke is irrelevant

here. Whatever Congress may have intended

in 1964, it is patent that Congress in

1977 perceived no conflict between Title

Vi's ban on discrimination and the ten

percent set aside in the Public Works

Employment Act of 1977. Even if any

such conflict existed, the ten percent

set aside would be lawful under the con

trolling principle that subsequent specific

legislative enactments prevail over former

general ones. See pp. 56-59, infra.

The immediate predecessor of the

Public Works Employment Act of 1977 was

the Local Public Works Capital Develop

ment and Investment Act of 1976, Pub.L.

-50-

No. 94-369 (July 22, 1976), 90 Stat. 999,

42 U.S.C. §§6701, et seq. When Congress

enacted the 1976 Act, it added a Title

VI nondiscrimination provision similar

to those added to virtually all laws

authorizing the expenditure of federal

monies by state and local governments.'*’

This provision, contained in §207(a) of

the Act, 90 Stat. 1007, 42 U.S.C. §6727

(a), is virtually identical to the

nondiscrimination provision contained in

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000d.^ Congress continued 1

1. The nondiscrimination provision provided as

follows:

"No person in the United States shall,

on the grounds of race, religion, color,

national origin, or sex, be excluded from

participation in, be denied the benefits of,

or be subjected to discrimination under any

program or activity funded in whole or in

part with funds made available under this

subchapter." 42 U.S.C. §6727(a).

2. The nondiscrimination provision in Title VI

provides:

"No person in the United States shall,

on the ground of race, color, or national

origin, be excluded from participation in,

be denied the benefits of, or be subjected

to discrimination under any program or

activity receiving Federal financial

assistance." 42 U.S.C. §2000d.

- 5 1 -

this parallel by requiring that the

nondiscrimination provision in the 1976

Act be enforced in the same discretionary

3manner as Title VI is enforced.

The following year, Congress sub

stantially amended the 1976 Act by

enacting the Public Works Employment Act

of 1977, Pub,L . No. 95-28 (May 13, 1977),

91 Stat. 116, 42 U.S.C. §§6710, et seg.,

as amended. See pp. 8 - 10, supra. Among

the amendments added by Congress in 1977

was the MBE ten percent set aside amend

ment, added by §103 of the 1977 Act, 91

Stat. 117, 42 U.S.C. §6705(f)(2), as

amended. When it added this amendment,

Congress saw no reason to alter the Act's

nondiscrimination provision barring

discrimination on grounds, inter alia,

of race, color and national origin in

"any program or activity" funded under

The only difference between this provision and the

nondiscrimination provision in the 1976 Act, see

note 1, supra, is that the latter added religion

and sex to the grounds of prohibited discrimination.

3. Compare the enforcement procedures in 207

(b)& (c) of the 1976 Act, 90 Stat. 1008, 42 U.S.C.

§6727(b)&(c) with the nearly identical procedures

under Title VI, 42 U.S.C. §2000d-l.

- 5 2 -

the Act, 42 U.S.C. §6727(a), as amended.

And Congress did not change the use of

Title VI procedure to enforce the non

discrimination provision.^ There, of

course , was no need to do so since Congress

viewed the MBE ten percent set aside as