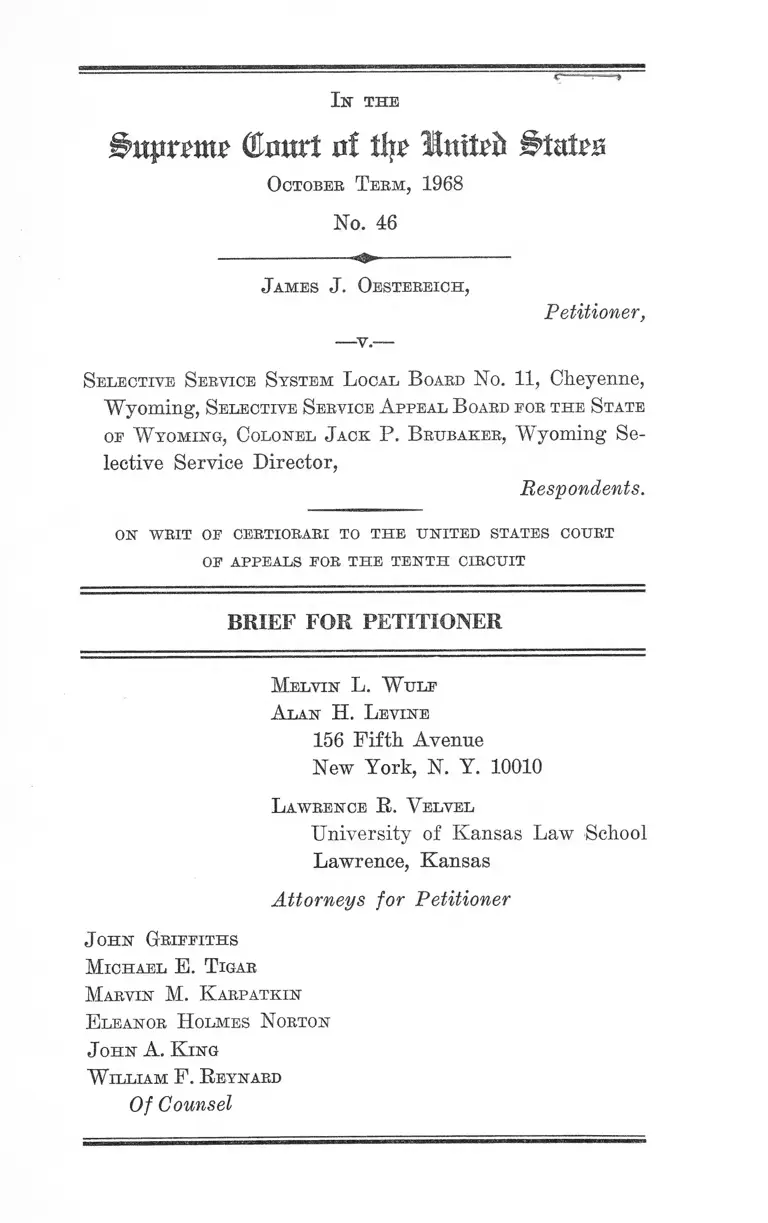

Oestereich v. Selective Service System Local Board No. 11 Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

August 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oestereich v. Selective Service System Local Board No. 11 Brief for Petitioner, 1968. af57f81a-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cfaba03c-db60-47eb-9a66-503ee7515a4f/oestereich-v-selective-service-system-local-board-no-11-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Isr the

Btiptme (Burnt ui tire Httitpfr Btutuu

Ootobee T eem, 1968

No. 46

J ames J. Oestebeich,

—v.—

Petitioner,

Selective Service System L ocal B oard N o. 11, Cheyenne,

Wyoming, Selective Service A ppeal B oard f o r the State

o f W yoming, Colonel J ack P. B rubaker, Wyoming Se

lective Service Director,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR TH E TEN TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Melvin L. W ulf

A lan H. L evine

156 Fifth. Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10010

L awrence R. V elvel

University of Kansas Law School

Lawrence, Kansas

Attorneys for Petitioner

J ohn Griffiths

M ichael E. T igar

Marvin M. K arpatkin

E leanor H olmes Norton

J ohn A. K ing

W illiam F. R eynard

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinions Below .................................................. -..... -..... 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

Statutes and Regulations Involved ............................... 2

Questions Presented ........................................................ 4

Statement of the Case .................................................... 5

Summary of Argument .................................................... 9

A rgument :

Introduction ................................ ...........................-.......... 16

I. The Federal Courts have jurisdiction to hear

and determine this suit ....................... 20

A. Effective Judicial Review of the Classifica

tion Orders of Local Boards Is Constitu

tionally Required ........................................... 20

B. In Cases Where a Board Order Affects

Rights Safeguarded by the First Amend

ment, the Federal Courts Have Jurisdiction

to Protect Those Rights ............................. 28

C. The “ Special Circumstances” of This Case

Require Judicial Review.............. 35

D. Congress, in Enacting Section 10(b)(3),

Did Not Intend to Bar Suits Such as the

Present One .................................................... 43

PAGE

11

II. The declaration of delinquency, punitive reclas

sification and order to report for induction in

this case are invalid ........................................... 45

A. Petitioner’s Reclassification Is Contrary to

an Exemption Expressly Granted by Stat

ute ..................................................................... 45

B. Punitive Reclassification Is Not Authorized

by Statute ...................................................... 46

C. Punitive Reclassification Is Not Authorized

by the Regulations ....................................... 50

D. Punitive Reclassification Is Unconstitutional 55

E. Local Board No. 11 Did Not Follow the

Procedure for Punitive Reclassification Re

quired by the Regulations and by Due Proc

ess ............................................................... -.... 64

III. Petitioner’s act of returning his registration

certificate to Local Board No. 11 was conduct

protected by the First Amendment .................. 68

A. Peaceful Conduct Which Is Relevant to the

Issue Giving Rise to the Protest Is Speech

Protected by the First Amendment ........... 68

B. Under the Tests for Determining When

Speech May Be Abridged, the Surrender of

Draft Cards Cannot Be Penalized ............... 73

1. Reg. 1642.4(a) Upon Which Petitioner’s

Delinquency, Reclassification, and Induc

tion Order Are Based Is Vague and

Overbroad .................................................. 73

PAGE

Ill

2. Plaintiff Is Being Unlawfully Punished

Under Past and Present Interpretations

of the Balancing Test ............................. 76

IV. There is in fact no independent requirement of

personal possession of registration certificates 85

Conclusion ................................................................................. 93

A ppendix :

Texts of Letter and Memo on the Draft ........... la

Delinquency Notice .................................................. 2a

T able op A uthorities

Cases:

Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U. S. 136 (1967) ..9, 20

21, 25

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616 (1919) .......14,69

Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347 U. S. 260 (1954) ........ 64

Allen v. Regents, 304 U. S. 439 (1938) .......................... 38

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U. S. 500 (1964) ..15, 75

Anderson v. Clark, Civil No. 48869 (N. D. Cal.) ....... 17

Anderson v. Hershey, No. 30729 (E. D. Mich.) .......... 17

Bartehy v. United States, 319 U. S. 484 (1943) ........ 59

Boire v. Greyhound Corp., 376 U. S. 473 (1964) ........ 37

Breen v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 16, No. 12422

(D. Conn.) ..................................................................... 17

Brothman v. Michigan, 379 Mich. 776, cert, denied, 36

U. S. L. Week 3287 (Jan. 16, 1968) .......................... 35

Brown v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443 (1953) ............................. 44

Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U. S. 131 (1966) ................ . 77

PAGE

IV

Brownell v. Tom We Slmng, 352 U. S. 180 (1956) -21, 25,40

Bucher, et al. v. Selective Service System, et al., No.

12, 26/67 (D. N. J.) ...................................................... 17

Cafeteria Workers v. McElroy, 367 U. S. 886 (1961) 64

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U. S. 89 (1965) ....................15, 80

Cheff v. Schnackenberg, 384 U. S. 373 (1966) .........-.... 63

Clark v. Uerbesee Finanz-Korporation, 332 U. S. 480

(1947) ..................................................... -.... -................. 5

Colfax v. Selective Service Local Bel. No. 11, Civ. Ac

tion No. 68-432 (W . D. Pa.) ...................................... 18

Collis v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 28, No. C-67-

19-M (N. D. W. Va.) .................................................. 17

Connor v. Selective Service Local Bd., No. Civ. 1968—33

(W. D. N. Y.) ........................-.................. -....... - ...... 17-18

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536 (1965) ............... —15, 75, 77

Cramp v. Bd. of Public Instruction, 368 U. S. 278 (1961) 74

Crowell v. Benson, 285 U. S. 22 (1932) .........-............21, 27

Barr v. Burford, 339 U. S. 200 (1950) ...................... 44

Davis v. United States, 160 U. S. 469 (1895) .........— 62

Decker v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 25, Civil No.

49348 (N. D. Cal.) ........................................................ 17

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 IT. S. 479 (1965) -10 ,15 , 29, 30,

31, 33, 34, 35, 74, 75

Douglas v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 415 (1965) -------- ---- ----- 61

Eagle v. United States ex rel. Samuels, 329 U. S. 304

(1946) ......................... ....... ............................-...... -...... 58

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) —71, 77

Estep v. United States, 327 U. S. 114 (1946) -1 2 , 21, 22, 27,

42, 46, 49, 64

Ex Parte Fabiani, 105 F. Supp. 139 (E. D. Pa. 1952) — 44

PAGE

PAGE

Ex Parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908) ..................10, 23, 24,

25, 27, 29

Falbo v. United States, 320 U. S. 549 (1944) .............. 22

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391 (1963) ................ - ........ . 41

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U. S. 51 (1965) .............. 34,35

Gabriel v. Clark, Civil No. 49419 (N. D. Cal.) .............. 28

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U. S. 335 (1963) -------- ------ 60

Glover v. United States, 286 F. 2d 84 (8th Cir. 1961) .... 44

Goldsmith v. Hershey, Civil No. 49281 (N. E>. Cal.) .... 17

Gonzales v. United States, 348 U. S. 407 (1955) .......49,65

Greene v. MeElroy, 360 U. S. 474 (1959) .......... 12, 46, 49, 50

Harmon v. Brucker, 355 U. S. 579 (1958) —.11,12, 35, 38, 46

Harris v. Buss, 146 F. 2d 355 (5th Cir. 1944) ............ - 61

Heikkila v. Barber, 345 U. S. 229 (1953) ..............21,40

Holland v. United States, 348 U. S. 121 (1954) ........... 62

Huey v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 22, No. C-225-

67 (C. D. Utah) .......................................- .... -.............. ^

In re Gault, 387 U. S. 1 (1967) .............. ...... ..........-.... 60,67

In re Oliver, 333 U. S. 257 (1948) ---------------- ----------- 63

Inti. Ladies Garment Workers Union v. Donnelly Gar

ment Co., 304 U. S. 243 (1938) ................................... 26

Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U. S. 717 (1959) .............................. 44

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341

U. S. 124 (1951) ................................... -..... - ........42,49,50

Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U. S. 144 (1963) ..13, 57,

58, 59, 63, 64

Kimball, et al. v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 15,

et al., No. 67/4733 (S. D. N. Y.) ................. ............17,42

VI

Knox v. United States, 200 F. 2d 398 (9th Cir. 1952) .... 65

Kolden v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 4, No. 6-68-64

Civil (D. Minn.) ..........................................................17,28

Leedom v. Kyne, 358 U. S. 184 (1958) ..........11,12,21,35,

36, 37, 46

Linzer, et al. v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 64,

et al., No. 68 C 110 (E. D. N. Y.) ............................. 17,18

Lipke v. Lederer, 259 U. S. 557 (1922) .......... 11, 21, 37, 38

Lockerty v. Phillips, 319 U. S. 182 (1943) ............ -9, 22, 23

McCulloch v. Sociedad Nacional, 372 U. S. 10 (1963) -21, 37,

46

Miller v. Standard Nut Margarine Co., 284 U. S. 498

(1932).............................................................................. 38

Milwaukee Pub. Co. v. Burleson, 255 U. S. 407 (1921) .... 50

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1963) ......... -.......... - 75

Niznik v. United States, 173 P. 2d 328 (6th Cir.), cert,

denied 337 U. S. 925 (1949) ................-...... -...... -.... 63

O’Brien v. United States, 88 S. Ct. 1673 (1968) ....15, 68, 76,

77, 78, 79, 80,

81, 82, 84

Ohio Valley Water Co. v. Ben Avon Borough, 253 U. S.

287 (1920) ......•.............................................................. 20

Oklahoma Operating Company v. Love, 252 U. S. 331

(1920)........................................................... 10, 23, 24, 25, 29

Olvera v. United States, 223 F. 2d 880 (5th Cir. 1955) .. 65

Orloff v. Willoughby, 345 U. S. 83 (1953) .................. 38

Pacific T. & T. Co. v. Kuykendall, 265 U. S. 196 (1924) 23

Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan, 293 U. S. 388 (1935) .... 53

PAGE

V ll

PAGE

Peffers and Hess v. Selective Service Appeal Bd., No.

7469 (W. D. Wash.) ................................................ ----- 18

Peters v. Hobby, 349 U. S. 331 (1955) ........-................ 46

Petersen v. Clark, et al., Civil No. 47888 (N. D. Cal.

1968) .............................................. -.............................. 1°> 25

Plummer v. Louisiana, 262 P. Supp. 1021 (D. C. La.

1967).......................................................................... - 44

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U. S. 400 (1965) ......................... 61

Porter v. Investors’ Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461 (1932) .. 23

Quaid v. United States, 386 F. 2d 25 (10th Cir. 1968) -12, 46

Reisman v. Caplin, 375 U. S. 440 (1964) ...................... 25

Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U. S. 305 (1966) .....-............15, 80

Rusk v. Cort, 369 U. S. 367 (1962) .................. 11, 21, 25, 40

Schilling v. Rogers, 363 U. S. 666 (1960) .................. 37

School of Magnetic Healing v. McAnnulty, 187 U. S. 94

(1902)....................................................................- -9 , 20,27

Schwartz v. Strauss, 206 F. 2d 767 (2d Cir. 1953) -—42,44

Service v. Dulles, 354 U. S. 363 (1957) ......................... 64

Shaughnessey v. Pedreiro, 349 U. S. 48 (1955) .........11,21

39-40

Shillitani v. United States, 384 U. S. 364 (1966) ....... 53

Simmons v. United States, 348 U. S. 397 (1955) .......65, 68

Smith v. Flinn, 261 F. 2d 781 (8th Cir. 1958) .......... 38

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513 (1958) ...................... 32

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U. S. 511 (1967) --- ----------------- 62

St. Joseph Stockyard v. United States, 298 U. S. 38

(1936)........................................................................ 9, 20, 27

Steinert v. Clark, Civil No. 48654 (N. D. Cal.) .............. 17

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 (1931) .......14, 71, 80

vm

Tamarkin v. Selective Service System, 243 F. 2d 108

(5th Cir. 1957) .............. ............................................ 43

Tomlinson v. Hershey, 95 F. Supp. 72 (E. D. Pa. 1949) 44

Townsend v. Zimmerman, 237 F. 2d 376 (6th Cir.

1956) .......... ..................................................... 43-44,65

Turney v. Ohio, 273 IT. S. 510 (1927) ................ ...... . 62

Turley v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 134, No. 68-

290-F (C. D. Cal.) ........................................................ 17

Uffleman v. United States, 230 F. 2d 297 (9th Cir. 1956) 61

United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Assn., 389

U. S. 217 (1967) ............... ........ ................... ............. 77

United States v. Brown, 381 U. S. 437 (1965) ............... 59

United States v. Burlicli, 257 F. Supp. 906 (S. D. N. Y.

1966) ......................................... - ..... ..................... ....... 65

United States v. Capson, 347 F. 2d 959 (10th Cir.), cert.

denied 382 U. S. 911 (1965) .................... .................... 60

United States v. Eisdorfer, No. 67 Cr. 302 (E. D. N. Y.

June 24, 1968) _____ ____ ______________ _________ .47, 53

United States v. Hayman, 342 U. S. 205 (1952) ........... 44

United States v. Hertlein, 143 F. Supp. 742 (E. D. Wise.

1956) ........................... ........ ...................... .................. - 59

United States v. Kime, 188 F. 2d 677 (7th Cir. 1951),

cert, denied 342 U. S. 825 (1951) ....................... ...... 59

United States v. Miller, 367 F. 2d 72 (2d Cir. 1966),

cert, denied 386 U. S. 911 (1967) ..............................81, 82

United States v. Stiles, 169 F. 2d 455 (3d Cir. 1948) .... 66

United States v. Sturgis, 342 F. 2d 328 (3d Cir.), cert.

denied 382 U. S. 879 (1965) ............. ....................... 60

United States v. Thompson, D. C. Mass., 1 S. S. .L. R.

3059 (1968) ...................... .................... ........................................... .................. . . . . . .66, 67

United States v. Vincelli, 215 F. 2d 210, reh. denied 216

F. 2d 681 (2d Cir. 1954) ............................ ...............65, 66

PAGE

IX

United States v. Willard, 211 F. Supp. 643 (N. D. Ohio

1962).................................................... -........................... 44

Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U. S. 535 (1959) ...........— ..... 64

Watkins v. Rupert, 224 F. 2d 47 (2d Cir. 1955) ........... 43

White v. Swenson, 261 F. Supp. 42 (Wr. D. Mo. 1966) 44

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 (1927) ...............14,72

Witmer v. United States, 348 U. S. 375 (1955) ........... 43

Wolff v. Selective Service, 372 F. 2d 817 (2d Cir.

1967) .................................................. 10.11, 32, 33, 34, 39,

44, 45, 55, 73, 74

Woo v. United States, 350 F. 2d 992 (9th Cir. 1965) .... 43

Woods, et al. v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 3, et ah,

No. 68 C 350 (E. D. N. Y.) .................... ...................... 17

Worsted v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 7, Civ.

Action No. 68-456 (AY. D. Pa.) ..................................... 18

Yakus v. United States, 321 U. S. 414 (194-4) .......9,22,23,

27, 30

Zemel v. Rusk, 381 U. S. 1 (1965) ................... .......... 53

Zigmond v. Selective Service Local Bd. No. 16, C. A.

No. 68-368-G (I). Mass.) .........................- ................. 18

Constitutional Provisions:

United States Constitution:

First Amendment ..................4,10,14,15, 28, 29, 30, 31,

32, 34, 35, 63, 64, 68, 69, 70,

71, 72, 73, 75, 76, 77, 78

..4, 26, 57, 63

.57, 61, 62, 63

............23, 30

PAGE

Fifth Amendment .....

Sixth Amendment .......

Fourteenth Amendment

X

Statutes :

26 U. S. C. §7421 ............................................................. 37

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) ..................... 1

28 U. S. C. §1361 ........ 93

28 IT. S. C. §2241 ......................... .................................. 44

28 IT. S. C. §2254 ....................................... 41

38 IT. S. C. §693(li) .......................................................... 38

Administrative Procedure Act:

Section 10 ....... 40

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952:

Section 349(a) (10) .................................................. 40

Section 360(b) and (c) ............................................ 40

Military Selective Service Act of 1967:

Section 1(c) ............................................................. 65

Section 6(f) [50 App. IT. S. C. §456(f)] .............. 42

Section 6(g) [50 App. U. S. C. §,456(g )] .......2, 4, 5, 8,

45,46

Section 6(h) [50 App. U. S. C. §456(h)] ......... 18,47

Section 6(i) [50 App. IT. S. C. §456( i ) ] ............—18,45

Section 6(j) [50 App. U. S. C. §456(j)] .............. 26

Section 10(b)(3) [50 App. IT. S. C. §460(b)(3) -2,4,7,

8,10,11, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29,

31, 35, 36, 39, 41, 43, 44, 45

Section 10(c) [50 App. U. S. C. §460(c)] ........— 46

Section 12(a) .......................................... 58,59

Section 15(b) ........................................................... 51

Prohibition A ct:

Section 35 ................................................................. 37

3224 Revised Statutes ....................................................37, 38

PAGE

XI

PAGE

Federal Regulations:

6 Fed. Reg. 1796 (March 31, 1941), Amendment

No. 22 ....................................................................... 87

7 Fed. Reg. 2086 (Feb. 15, 1942), Amendment

No. 21, 2d Ed.......................................................... 88

7 Fed. Reg. 9683 (Nov. 23, 1942), Amendment

No. 101, 2d Ed..............-....................................... 87,88

7 Fed. Reg. 9773 (Nov. 23, 1942), Amendment

No. 102, 2d Ed.................................................88, 89, 91

Regulations Under Selective Service A ct:

Section 617.1 .......................................

Section 617.2 ............. -.........................

Section 617.11 .....................................

Section 623.61-1 ..................................

Section 623.61-2 ................................. .

Section 623.61-3 .............................

,87, 88, 91

.87, 88, 91

....... 91

......91, 92

.88, 91, 92

....... 91

1917 Regulations:

Section 57 .. 90

1918 Regulations:

Section 279 ............................................................... 90

Selective Service Regulations, Second Edition, First

Printing 437 (1944) ...................................................... 89

Selective Service Regulations:

Regulation 1604.55 [32 C. F. R. §1604.55] ........... 62

Regulation 1604.62 [32 C. F. R. §1604.62] ............. 62

Regulation 1604.71 [32 C. F. R. §1604.71] - ............ 60

Regulation 1617.1 [32 C. F. R. §1617.1] -.3 , 4, 5,12,13,

16, 50, 85, 90, 91

Regulation 1621.10 [32 C. F. R. §1621.10] .......... 73, 91

Regulation 1621.13 [32 C. F. R. §1621.13] .............. 73

Regulation 1621.14 [32 C. F. R. §1621.14] ............ 52

Regulation 1621.15 [32 C. F. R. §1621.15] ............. 61

Regulation 1622.1 [32 C. F. R. §1622.1] ..............51, 61

Regulation 1622.10 [32 C. F. R. §1622.10] ..............6, 61

Regulation 1622.17 [32 C. F. R. §1622.17] ............ - 18

Regulation 1622.25 [32 C. F. R, §1622.25] ............ 18

Regulation 1622.26 [32 C. F. R. §1622.26] ............. 18

Regulation 1622.30 [32 C. F. R. §1622.30] ..... 18

Regulation 1622.40 [32 C. F. R. §1622.40] _______ 19

Regulation 1622.43(a)(4) [32 C. F. R. §1622.43

(a )(4 )] ......................................-............................ 5

Regulation 1622.50 [32 C. F. R. §1622.50] .......... 18,19

Regulation 1623.1 [32 C. F. R. §1623.1] .................. 52

Regulation 1623.2 [32 C. F. R, §1623.2] ............... 61

Regulation 1623.5 [32 C. F. R. §1623.5] ............... 90

Regulation 1623.6 [32 C. F. R. §1623.6] .................. 88

Regulation 1624.1 [32 C. F. R. §1624.1] ...........60,61

Regulation 1625.1 [32 C. F. R. §1625.1] ....... -.52, 62

Regulation 1628.16 [32 C. F. R. §1628.16] .............. 73

Regulation 1631.7 [32 C. F. R. §1631.7] .............. 17, 47

Regulation 1632.9 [32 C. F. R. §1632.9] ............... 6

Regulation 1641.3 [32 C. F. R. §1641.3] ............ 91

Regulation 1641.7 [32 C. F. R. §1641.7] ............... 51

Regulation 1642 :[32 C. F. R. §1642] ...................... 52

Regulation 1642.4 [32 C. F. R, §1642.4] .......3, 4,14, 53,

62, 63, 66,

67, 73, 75

Regulation 1642.10 [32 C. F. R. §1642.10] 53, 66, 67

Regulation 1642.12 [32 C. F. R. §1642.12] .17,19, 62, 63

Regulation 1642.13 [32 C. F. R. §1642.13] .17, 55, 62, 67

Regulation 1642.14 [32 C. F. R. §1642.14] ........... 54, 62

xii

PAGE

X l l l

PAGE

Miscellaneous:

Amsterdam, The Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the

Supreme Court, 109 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) ....... 74

Byse and Fiocca, Section 1361 of the Mandamus and

Venue Act of 1962 and “Nonstatutory” Judicial Re

view of Federal Administrative Action, 81 Harv.

L. Rev. 308 (1967) .......................................................- 93

Cong. Record, Vol. 113 (June 12, 1967):

S. 8052 .............. ................................................ - .... 43

4 Davis Administrative Law Treatise:

§28.18 (1958) ................ ..... ....................................... 21

§30 .................... ................... -..................................... 38

Dranitzke, The Possession of Registration Certificates

and Notices of Classification by Registrants Under

the Selective Service System, 1 S. S. L. R. 4029

(1968) ....................................................................... 85

Enforcement of the Selective Service Law, Selective

Service System Special Monograph No. 14, 56

(1951) .......................................................... 56,86,87,92

Enforcement of the Selective Service Law, Selective

Service System Special Monograph No. 18, 122

(1967) ........................................................................... - 90

Finman & Macaulay, Freedom to Dissent: The Viet

Nam Protests and the Words of Public Officials, 1966

Wis. L. Rev. 632 ............................................................ 70

Griffiths, Some Notes on the Solicitor General’s Memo

randum in Oestereich, 1 Selective Service Law Re

porter 4012 (1968) .......................................................... 39

PAGE

Hart and Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the Fed

eral System 312 (1953) .............................................. 21,

House Report No. 267, Committee on Armed Services 7

“ In Pursuit of Equity: Who Serves When Not All

Serve?,” Report of the National Advisory Commis

sion on Selective Service 29 (1967) .............................

Jaffe, Judicial Control of Administrative Action 587

(1956) .............................................................................

Jaffe, The Right to Judicial Review I, 71 Harvard Law

Review 401 (1958) ........................................................

Jaffe, The Right to Judicial Review II, 71 Harvard

Law Review 769 (1958) ................................................

Kamin, Residential Picketing and the First Amend

ment, 61 Northwestern U. L. Rev. 177 (1966) ..........

Layton and Fine, “ The Draft and Exhaustion of Ad

ministrative Remedies,” 56 Geo. L. J. 315 (1967) ....

N. Y. Times, December 30, 1967, p. 2 .............................

Note, Fairness and Due Process Under the Selective

Service System, 114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1014 (1966) .......

Note, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 685 (1967) ............................... 34,

Note, 114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1014 (1966) .............................

Selective Service System, Legal Aspects of Selective

Service 7 (1963) ..........................................................55,

Supp. No. 18, Justice Department Circular No. 3421

to United States Attorneys, dated October 18, 1943 ..

Velvet, Freedom of Speech and The Draft Card Burn

ing Cases, 16 Kan. L. Rev. 149 (1968) ......................70,

22

43

63

64

21

21

70

34

16

65

45

61

62

56

81

Ik the

§>uprTUt£ Court of tfyr i ’totro

October T eem, 1968

No. 46

J ames J. Oesteeeich,

- y .

Petitioner,

Selective Service System L ocal B oard N o. 11, Cheyenne,

"Wyoming, Selective Service A ppeal B oard for the State

oe W yoming, Colonel Jack P. B rubaker, Wyoming Se

lective Service Director,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES COURT

OE APPEALS FOR TH E TEN TH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The Order of the United States District Court, District

of Wyoming (A. 13-18), is reported at 280 F. Supp. 78.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

(A. 20) is reported at 390 F. 2d 100.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

February 21, 1968. The petition for certiorari was filed

on March 19, 1968 and was granted on May 20, 1968. The

jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U. S. C. §1254(1).

2

Statutes and Regulations Involved

"’"""Section 10(b) (3), Military Selective Service Act of 1967;

50 App. U. S. C. §460(b) (3):

“No judicial review stall be made of the classification

or processing of any registrant by local boards, appeal

boards, or the President, except as a defense to a

criminal prosecution instituted under section 12 of this

title, after the registrant has responded either affirma

tively or negatively to an order to report for induction,

or for civilian work in the case of a registrant deter

mined to be opposed to participation in war in any

form : Provided, That such review shall go to the ques

tion of the jurisdiction herein reserved to local boards,

appeal boards, and the President only when there is no

basis in fact for the classification assigned to such

registrant.”

Section 6(g), Military Selective Service Act of 1967;

50 App. U. S. C. §456(g ):

“Ministers of religion.—Regular or duly ordained min

isters of religion, as defined in this title, and students

preparing for the ministry under the direction of rec

ognized churches or religious organizations, who are

satisfactorily pursuing full-time courses of instruction

in recognized theological or divinity schools, or who

are satisfactorily pursuing full-time courses of instruc

tion leading to their entrance into recognized theolog

ical or divinity schools in which they have been pre

enrolled shall be exempt from training and service (but

not from registration) under this title.”

3

Selective Service Regulation 1617.1; 32 C. F. R. §1617.1:

“Effect of failure to have unaltered registration certifi

cate in personal possession.—Every person required

to present himself for and submit to registration must,

after he has registered, have in his personal possession

at all times his Registration Certificate (SSS Form 2)

prepared by his local board which has not been altered

and on which no notation duly and validly inscribed

thereon has been changed in any manner after its

preparation by the local board. The failure of any per

son to have his Registration Certificate (SSS Form 2)

in his personal possession shall be prima facie evidence

of his failure to register. When a registrant is in

ducted into the armed forces or enters upon active

duty in the armed forces, other than active duty for

training only or active duty for the sole purpose of

undergoing a physical examination, he shall surrender

his Registration Certificate (SSS Form 2) to the com

manding officer of the joint examining and induction

station or to the responsible officer at the place to

which he reports for active duty, and such certificate

shall be destroyed by the officer to whom it is sur

rendered.”

Selective Service Regulation 1642.4(a); 32 C. F. R.

§1642.4(a):

“Declaration of Delinquency Status and Removal There

from.— (a) Whenever a registrant has failed to per

form any duty or duties required of him under the

selective service law other than the duty to comply

with an Order to Report for Induction (SSS Form 252)

or the duty to comply with an Order to Report for

4

Civilian Work and Statement of Employer (SSS Form

153), the local board may declare him to be a delin

quent.”

Questions Presented

Petitioner, a student preparing for the ministry, was

exempt from training and service in the Armed Forces

under Section 6(g) of the Military Selective Service Act

of 1967 [50 App. U. S. C. §456 (g )]. Upon returning his

Selective Service Registration Certificate to the govern

ment as a statement of protest against the war in Vietnam,

petitioner was declared delinquent under the Selective

Service regulations, stripped of his exemption, reclassified

I-A and ordered to report for induction. Under these

circumstances:

1. Does Section 10(b)(3) of the Military Selective Ser

vice Act of 1967 [50 App. U. S. C. §460(b)(3)] preclude

judicial review of petitioner’s punitive reclassification and

order to report for induction!

2. Does the declaration of delinquency, punitive reclas

sification, and induction of petitioner for failure to have

his Registration Certificate in his personal possession, vio

late the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment, the

Military Selective Service Act of 1967, and the Selective

Service Regulations!

3. Does Selective Service Regulation 1617.1 [32 C. F. R.

§1617.1], as construed and applied in this case, and Selec

tive Service Regulation 1642.4(a) [32 O. F. R. §1642.4(a)]

on its face, violate the First Amendment!

5

4. Does a registrant in fact violate Regulation 1617.1 if

he does not have his Registration Certificate in his personal

possession?

Statement of the Case1

Petitioner is a duly enrolled student “preparing for the

ministry” at And over-Newton Theological School, Newton

Centre, Massachusetts, a “ recognized theological or divinity

school.” Military Selective Service Act of 1967, Sec. 6(g),

50 App. U. S. C. Sec. 456(g) [hereinafter “Act” ] ; 32

C. F. R. Sec. 1622.43(a)(4) [hereinafter “Regs.” ]. As

such, he was classified IV-D by Local Board No. 11 on June

20,1966 and thus exempt from military service (A. 3).

On October 16, 1967, together with numerous other

persons, petitioner returned his Selective Service registra

tion certificate (.SSLSJiAim.21. to the United States Govern -

ment solely for the purpose of registering his dissent from

participation by the United States in the war in Vietnam

(A. 3). Petitioner, by affidavit, explained in detail his rea

sons for returning his registration certificate. He described

it as “ an act of collective conscience in support of our dy

ing and suffering brothers who are presently fighting on

our behalf in Vietnam,” and “ a responsible expression of

concerned citizens, acting in light of the first amendment.”

His act was based upon his “understanding of the claims

which the Christian faith brings to bear on the human

situation” including the belief that “man responds to God’s

revelation by concrete participation in the structures and

1 The Statement of the Case is based upon the allegations in the

complaint, taken as admitted upon the government’s motion to dis

miss. Clark v. Vebersee Finanz-Korporation, 332 U. S. 480 (1947).

6

decisions of life, with a transcending loyalty to the will

of God, the authority of the scriptures, and the community

of interpretation which is the church,” and in his belief

in the doctrine of the “Just War” . He stated his belief

that “ the Yiet Nam situation reveals this war to be in

violation of most of the criteria of the just war doctrine and

is a major threat to the security and peace of the world”

(A. 7-11).

On November 7, 1967, Local Board No. 11 mailed peti

tioner a Delinquency Notice (SSS Form 304) informing

him that he “became delinquent” on October 20, 1967. The

Delinquency Notice advised petitioner that he was delin

quent for the following reasons: (1) “ Failure to have in

his possession a duly authorized Registration Certificate

(SSS Form 2)” and (2) “Failure to provide the local board

of his current status” (A. 4).2

Simultaneously, on November 7,1967, Local Board No. 11

mailed petitioner a Notice of Classification (SSS Form 110)

reclassifying him I-A (A. 4).3 Petitioner duly appealed his

I-A reclassification to the Selective Service Appeal Board

for the State of Wyoming which unanimously affirmed the

classification on December 27, 1967.4 On the same day,

December 27th, Local Board No. 11 mailed petitioner an

order to report forJuidncfion in Cheyenne, Wyoming, at

3:00 P.M. on January 24, 1968 (A. 4).5

2 The Delinquency Notice is reproduced in the Appendix, infra,

p. 2a.

3 Class I-A indicates that a registrant is “Available for Military

Service.” Reg. 1622.10.

4 Thereby exhausting administrative remedies (A. 4).

5 Petitioner’s place of induction was subsequently transferred,

pursuant to Reg. 1632.9, to Dorchester, Massachusetts, and post

poned to February 26, 1968.

7

On January 19, 1968, suit was filed in the United States

District Court for the District of Wyoming to enjoin peti

tioner’s induction into the armed forces. Oral argument

was heard on January 22, 1968, on petitioner’s application

for a temporary restraining order. After oral argument,

respondents’ Motion to Dismiss was granted from the

bench. An order dismissing the action was entered that

day (E. 23-24), a subsequent nunc pro tunc order was en

tered on January 23, 1968 (E. 25), and an Order Setting

Aside Prior Orders and Dismissing Plaintiff’s Action was

entered on February 6, 1968 (A . 13-18).

The District Court’s February 6th order found, among

other things, that the action did “not arise under the Con

stitution, laws or treaties of the United States” (A. 14),

that the matter in controversy did not exceed $10,000

(ibid.), that there was no diversity of citizenship (A. 15),

that it was divested of jurisdiction because of Sec. 10(b)(3)

of the Act (A. 15-16), that “ to assume jurisdiction over

plaintiff’s action would violate the fundamental constitu

tional precept of separation of powers . . . ” (A. 16), that

petitioner knew that he was required to have his registra

tion certificate in Ms possession at all times (ibid.), that

“ exemptions and classifications are a privilege, not an in

alienable right conferred by the Constitution or statute”

(A. 16-17), and that the action complained of “does not

constitute penal action” (A. 17).

Uotice of Appeal was filed on February 6, 1968 (E. 34),

and an expedited appeal was heard by the Tenth Circuit

on February 19, 1968. On February 21, 1968, the Court of

Appeals affirmed the decision below in a per curiam de

cision which reads in its entirety as follows:

8

“ The judgment is affirmed for the reasons set forth in

the memorandum decision of the trial court and par

ticularly in view of the jurisdictional restrictions con

tained in 50 App. U. S. C. §460(b)(3). Orderly classi

fication of a registrant for military service is not puni

tive in nature. Compare United States v. Capson, 10

Cir., 347 P. 2d 958. Appellant is not denied his right

to ultimate judicial review of his claimed rights. Wit-

mer v. United States, 348 U. S. 375, 377.”

An application for a stay was denied by the Tenth Cir

cuit on February 23, 1968. On the same day an application

to stay petitioner’s induction was presented to Mr. Justice

White. On March 5, 1968, after the government had agreed

to the postponement of petitioner’s induction to allow time

for consideration of the stay application, Mr. Justice White

issued an order staying “ the execution and enforcement

of the judgment of the United States District Court for

the District of Wyoming, as affirmed by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit . . . ” on the condi

tion that this petition for certiorari be filed on or before

March 19, 1968. The petition was filed on that date.

In his Memorandum for Respondents, the Solicitor Gen

eral took the position that the Court should reverse the

judgment below and, subject to establishment of the requi

site jurisdictional amount, direct that a decree be en

tered in petitioner’s favor. The position was based on the

Solicitor General’s acknowledgement that the Local Board

had deprived petitioner of a mandatory exemption granted

by Congress in Sec. 6(g) of the Act and that the Sec. 10

(b)(3) prohibition of pre-induction judicial review ought

to be construed “to exclude purported action of a board

9

which is in fact contrary to an exemption which has been

expressly granted by statute” (Memorandum for Respon

dents, p. 12),6

Summary of Argument

I. The Federal Courts Have Jurisdiction to Hear and Deter

mine This Suit,

A. Effective Judicial Review of the Classification Orders of

Local Boards Is Constitutionally Required.

The Constitution requires judicial review of the orders

and actions of administrative agencies. School of Magnetic

Healing v. McAnnulty, 187 U. S. 94 (1902); Abbott Labora

tories v. Gardner, 387 U. S. 136 (1967); St. Joseph’s Stock-

yard v. United States, 298 U. S. 38 (1936). Lockerty v.

Phillips, 319 U. S. 182 (1943); and Yakus v. United States,

321 U. S. 414 (1944), which are often cited as examples of

extreme judicial deference to congressional efforts to pre

clude judicial review of agency action, in fact stand for the

6 The Memorandum for Respondents also adverts to the fact

that petitioner was declared delinquent and reclassified I-A not only

for turning in his Registration Certificate but also for his “Fail

ure to provide the local board of his current status,” and says that

“ to overturn the administrative action, [petitioner] is under the

burden of showing that all grounds of decision are invalid” (pp.

10-11). Beyond the fact that it is improbable that this case would

have gone as far as it has simply because of petitioner’s failure

to notify his Local Board that he was enrolled in a recognized

divinity school, Local Board No. 11 was advised of petitioner’s

current status as a divinity student when it was served with

the complaint in this case and again when, by letter dated April

17, 1968, petitioner’s school so informed the Board. Furthermore,

the Solicitor General, Attorney for Respondents, personally “ con

firmed” the fact that petitioner “ is a full-time student in good

standing at . . . a ‘recognized theological or divinity school’ ”

(Memorandum for Respondents, p. 11), thus purging that aspect

of petitioner’s delinquency.

10

proposition that there must be a preliminary opportunity to

contest the constitutionality of an administrative order

in civil proceedings prior to facing criminal charges for its

violation.

Ex Parte Young, 209 U. S. 123 (1908); and Oklahoma

Operating Company v. Love, 252 U. S. 331 (1920), both

require judicial review at an earlier stage than as a defense

to a criminal prosecution where the penalty for being wrong

is so great as to deter challenge to the validity of agency

action.

Petersen v. Clark, et al., Civil No. 47888 (N. D. Cal.

1968), held Section 10(b)(3) unconstitutional on the ground

that “judicial review cannot be conditioned on the risk of

incurring a substantial penalty or complying with an in

valid order.” The case also holds that “allowing civil review

in advance of criminal prosecution would not disrupt the

Selective Service System.”

5. In Cases Where a Board Order Affects Rights Safe

guarded by the , the Federal Courts

Have Jurisdiction to Protect Those Rights.

Even if Section 10(b)(3) is not unconstitutional in the

generality of cases, it should be held inapplicable in the

present case where it is the interest of the First Amend

ment which is at stake. Petitioner having been punitively

reclassified because of his protest against the war, to allow

him to raise his claims only in a criminal prosecution, effec

tively nullifies his First Amendment rights and deters the

exercise of those rights by others. Dombrowski v. Pfister,

380 U. S. 479 (1965); Wolff v. Selective Service, 372 F. 2d

817 (2d Cir. 1967).

11

C. The “Special Circumstances” of This Case Require

Judicial Review.

Notwithstanding legislative efforts to preclude or defer

judicial review of administrative orders, the “ special cir

cumstances” rule has been applied to allow review where

an administrative agency has exceeded its jurisdiction or

where strict application of the statutory limitations on ju

dicial review will result in needless detention or prosecution.

The application of that rule is appropriate here where the

local board exceeded its jurisdiction. To require that peti

tioner needlessly run the risk of criminal prosecution or

detention Jn order to establish that the Local Board ex

ceeded its jurisdiction warrants applicatjp^JlLtJlBJlsjiecial

circumstance” rule. Leedom v. Kyne, 358 U. S. 184 (1958);

LipJce v. Lederer, 259 U. S. 557 (1922); Harmon v.

Brucker, 355 U. S. 579 (1958); Wolff v. Selective Service,

supra; Shaughnessey v. Pedreiro, 349 U. S. 48 (1955);

Rusk v. Cort, 369 IT. S. 367 (1962).

D. Congress, in Enacting Section 1 0 ( b ) ( 3 ) , Did Not Intend

to Bar Suit Such as the Present One.

In adopting Section 10(b) (3), Congress intended only to

codify existing law including cases like Wolff v. Selective

Service, supra, and others which recognize a broader scope

of judicial review in the Selective Service area. The argu

ment that Section 10(b)(3) reflects displeasure with Wolff

v. Selective Service and the intent to overrule it, can be

found to be consistent with the exhaustion and justiciability

aspects of Wolff rather than with the repudiation of its

constitutional base.

12

II. The Declaration of Delinquency, Punitive Reclassification

and Order to Report for Induction in This Case Are

Invalid.

A. Petitioner’s Reclassification Is Contrary to an Exemp

tion Expressly Granted by Statute.

A dministrative agency action which flies in the face of

explicit statutory language is a nullity. Estep v. United

States, 327 U. S. 114 (1946); Leedom v. Kyne, supra;

Harmon v. Brucker, supra; Quaid v. United States, 386

F. 2d 25 (10th Cir. 1968). Consequently, withdrawal of

petitioner’s IV-D classification, conferred by statute, is

invalid.

B. Punitive Reclassification Is Not Authorized by Statute.

The Act makes no provision for induction as a summary

punishment for breach of duties under Selective Service

law. “Without exclusive action by lawmakers, decisions of

great constitutional import and effects would be relegated

by default to administrative suits . . . and not endowed with

authority to decide them.” Greene v. McElroy, 360 U. S.

474 (1959).

C. Punitive Reclassification Is Not Authorized by the

Regulations.

Selective Service Regulations do not provide for reclassi

fication and induction as a punishment for the breach of

duties under Selective Service law. The sole function of

the delinquency procedure is to secure information re

quired by local boards to enable them intelligently to per

form their classification function. Delinquency is analogous

to civil contempt. Regulation 1617.1 cannot be enforced

through the delinquency procedure because the possession

13

requirement does not serve the information gathering func

tion of the delinquency procedure. Application of the de

linquency procedure to enforce Reg. 1617.1 is to use that

procedure as a form of criminal contempt designed to pun

ish for past acts, rather than as civil contempt to secure

compliance with the Regulations.

D. Punitive Reclassification Is Unconstitutional.

The use of the delinquency Regulation in this case

and petitioner’s subsequent reclassification and induction

is punishment. Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martines, 372 U. S.

144 (1963). Consequently, the procedures leading up to peti

tioner’s order to report for induction are unconstitutional

because punishment cannot be imposed without procedural

due process of law including the right to counsel, confron

tation and cross-examination, compulsory process, privilege

against self-incrimination, an impartial tribunal, a public

trial, and a jury trial, none of which were available to

petitioner.

E. Local Board 11 Did Not Follow the Procedure for

Punitive Reclassification Required by the Regulations

and by Due Process.

By concurrently declaring petitioner to ho--.a. delinquent,

and reclassifying him I-A, Local Board 11 violated S.elec-

tive Service Regulations and due process of law. The pur-

pose'dfa’Tfelinquency notice is to afford a registrant rea

sonable time to clear up his delinquency status and to avoid

reclassification into I-A. But simultaneous reclassification

deprives the delinquency notice of any function whatsoever.

The opportunity to have a I-A classification removed is not

the same as the right to show in advance that there is no

occasion to reclassify to I-A.

14

III. Petitioner’s Act of Returning His Registration Certificate

to Local Board No. 11 Was Conduct Protected by the

First Amendment.

A. Peaceful Conduct Which Is Relevant to the Issue

Giving Rise to the Protest Is Speech Protected by

the First Amendment.

Symbolic conduct must be considered speech if it is peace

ful and if it is relevant to the issue giving rise to the sym

bolic protest. The proposed rule permits courts to draw a

sensible balance between the need for an ordered society

and a need to serve the vital functions of the First Amend

ment. Those functions consist of insuring that there is a

free market place of ideas, Abrams v. United States, 250

U. S. 616 (1919), to insure that the government will be re

sponsive to the wishes of the people, Stromberg v. Cali

fornia, 283 U. S. 359 (1931), and to preserve a stable and

just society by enabling citizens to express their grievances

in a peaceable way. Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357

(1927).

B. Under the Tests for Determining When Speech May

Be Abridged, the Surrender of Draft Cards Cannot

Be Penalized.

1. Reg. 1642.4(a) Upon Which Petitioner’s Delin

quency, Reclassification, and Induction Order

Are Based Is Vague and Overbroad.

Reg. 1642.4(a) upon which petitioner’s delinquency, re

classification, and induction order are based is vague and

overbroad. Under Reg. 1642.4(a), not only petitioner’s con

duct, but other conduct unarguably protected by the First

Amendment, has been the basis for delinquency and re

classification. The Regulation, therefore, runs afoul of the

15

rule which condemns statutes or regulations with an “ over

broad sweep . . . [which] lend themselves too readily to

denial of [First Amendment] rights.” Dombrowski v. Pfis-

ter, 380 U. S. 479, 486 (1965); Aptheker v. Secretary of

State, 378 U. S. 500 (1964); Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U. S. 536

(1965).

2. Plaintiff Is Being Unlawfully Punished Under

Past and Present Interpretations of the Balanc

ing Test.

O’Brien v. United States, 88 S. Ct. 1673 (1968), appears

to indicate that, although First Amendment conduct can

not be regulated unless it poses some danger to a compelling

government interest, the degree of danger need not be

substantial in order for the government to have the right

to regulate the conduct. Application of this standard to

peaceful symbolic conduct opens the door to government

repression of many kinds of speech—pure and symbolic.

However, O’Brien v. United States also held that a restric

tion on speech can be no greater than is essential to further

a legitimate government interest. The restriction on speech

at issue in the case at bar is greater than necessary because

the government can run an effective Selective Service Sys

tem even though a few registrants have surrendered their

Registration Certificates. Though the administrative bene

fits flowing from enforcement of the possession regulation

are inconsequential [Carrington v. Rash, 380 TJ. S. 89

(1965); Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 XJ. S. 305 (1966)], the “ con

tinuing availability” of surrendered cards leaves those bene

fits undisturbed.

16

IV. There Is in Fact No Independent Requirement of Per

sonal Possession of Registration Certificates.

Tracking the history of Selective Service Regulation

1617.1 to World War I, establishes that non-possession of a

Registration Certificate is not a violation of the Regula

tions in itself, but is only prima facie evidence of another

act which is a violation of the Regulations and of the Act,

i.e., non-registration.

A R G U M E N T

Introduction

Petitioner’s registration certificate was one of 357 draft

cards which were returned to the government at a demon

stration at the Department of Justice on October 20, 1967

(Washington Post, January 25, 1968), and an additional

297 draft cards returned the next day during a demonstra

tion at the Pentagon (N. Y. Times, December 30, 1967,

p. 2).

On October 24, 1967, General Lewis B. Hershey, the Di

rector of Selective Service, issued a memorandum to all

local draft boards recommending the reclassification and

induction of registrants who abandon their Selective Ser

vice registration certificates or notices of classification.

Appendix, infra, p. la. Two days later, General Hershey,

in a letter addressed to all draft boards, encouraged the re

classification and induction of any registrant who, among

many other things, “violates the military Selective Service

Act or the Regulations, or the related processes . . . ” . Ibid.

The local boards responded promptly and affirmatively.

Though counsel cannot say precisely how many registrants

17

have been declared delinquent, stripped of their defer

ments or exemptions, reclassified I-A, and ordered for

priority induction into the armed forces, we have personal

knowledge of no less than seventy-six plaintiffs in eighteen

lawsuits who, having either been declared delinquent, or de

clared delinquent and reclassified I-A, are subject to prior

ity induction or have received induction orders.7 8 Linger,

et al. v. Selective Service System Local Board No. 64, et al.,

No. 68 C 110 (E. D. N. T .) ; Woods et al. v. Selective Service

Board No. 3 et al., No. 68 C 350 (E. D. N. Y .) ; Kimball,

et al. v. Selective Service Local Board No. 15, et al.,

No. 67/4733 (S. D. N. Y .) ; Bucher, et al. v. Selective Ser

vice System, et al., No. 12, 26/67 (D. N. J .) ; Collis v. Selec

tive Service Local Board No. 28, No. C-67-19-M (N. D.

W. Va.); Anderson, et al. v. Hershey, et al., No. 30729

(E. D. Mich.); Steinert, et al. v. Clark, et al., Civil No. 48654

(N. D. Cal.); Decker, et al. v. Selective Service Board No.

25, Civil No. 49348 (N. D. Cal.); Anderson v. Clark, et al.,

Civil No. 48869 (N. D. Cal.); Goldsmith v. Hershey, et al.,

Civil No. 49281 (N. D. Cal.); Kolden v. Selective Service

Local Board No. 4, No. 6-68-64 Civil (D. Minn.); Breen v.

Selective Service Local Board No. 16, No. 12422 (D. Conn.);

Turley v. Selective Service System Local Board No. 134,

No. 68-290-F (C. D. Cal.); Huey v. Selective Service Local

Board No. 22, et al., No. C-225-67 (C. D. Utah) ;s Connor,

7 A “ delinquent” may be classified I-A. Reg. 1642.12. If a de

linquent is reclassified I-A, he shall be ordered to report for induc

tion. Reg. 1642.13. I-A delinquents stand at the top of the order of

call and are to be inducted before all other draftees. Reg. 1631.7.

8 Huey was reclassified I-A delinquent not for turning in his

draft card but for participating “ in a peaceful public demonstration

near the Armed Forces Entrance and Examination Station at 438

South Main Street, Salt Lake City, Utah, for the sole purpose of

expressing publicly his dissent from American involvement in the

Vietnam War.” Huey Complaint, p. 2. Huey is an example of the

18

et al. v. Selective Service Local Board, et at., No. Civ. 1968

-—33 (W. D. N. Y .) ; Colfax v. Selective Service System

Local Bd. No. 11, et al., Civ. Action No. 68-132 (W. D. P a .);

Worstell v. Selective Service System Local Bd. No. 7, et al.,

Civ. Action No. 68-156 (W. D. Pa.); Zigmond v. Selective

Service Local Board No. 16, C. A. No. 68-368-Gr (D. Mass.).

Registrants who have been declared delinquent, declared

delinquent and reclassified, or ordered to report for induc

tion, include men in a variety of classifications. Some, like

petitioner, had been exempt as ministers or students of

the ministry; others had been deferred as students (Act,

Sec. 6(h) and ( i ) ; Regs. 1622.25, 1622.26); a 37 year old

registrant formerly classified Y-A under Reg. 1622.50 as

over-age, was reclassified I-A (N. Y. Times, December

20, 1967, p. 15); of the six plaintiffs in Linser v. Selective

Service System, supra, all but one of whom have been re

classified I-A, two had II-S deferments as students, one

had been classified I-Y because “ under applicable physical,

mental, and moral standards [he is] not currently quali

fied for service” (Reg. 1622.17), one had been deferred in

class III-A as a parent (Reg. 1622.30), one had been classi

fied IY-A having completed his military service (Reg.

punitive reclassification of a registrant pursuant to the Hershey

letter of October 26, 1967. Appendix, infra, p. la. In Peffers

and Hess v. Selective Service Appeal Board, No. 7469 (W. D.

Wash.), two men were reclassified I-A and ordered for priority

induction for distributing anti-war leaflets during their pre-induc

tion. physical examinations. The plaintiffs’ deferments were re

stored by their boards only after suit was filed. On May 15, 1968,

Local Board No. 10, Mount Vernon, N. Y., declared Daniel F.

Connell III delinquent for “ Counseling evasion of The Selective

Service Law,” and on June 27, 1968 reclassified him from III-A

(Mr. Connell is married and has two children) to I-A. His case

is on appeal to the State Appeal Board.

19

1622.40),9 and one had been classified Y-A as over the age

of liability (Reg. 1622.50).10

Thus, petitioner is not a victim of an aberrant draft

board. Though we do not know exactly how many men

have been declared delinquent, reclassified, or ordered to

report for induction, we know that the number is far

greater than seventy-six.

Whatever the number of registrants who have been di

rectly affected by the policy at issue here, equally sig

nificant is the number of registrants who have been silenced

out of fear that, should they publicly protest against the

war in Vietnam, they too will lose their deferred or exempt

status. What is at stake, therefore, is the power of the

government to present to a large number of young men the

choice of surrendering their right to speak freely on ques

tions of urgent public importance, or of suffering heavy pen

alties for exercising that right. Equally at issue is the

power of the Selective Service System to deprive persons

of exemptions granted by statute, and to impose punish

ment without due process of law under the capricious au

thority of a distorted “ delinquency” procedure which is

unauthorized either by statute or regulation.

9 The IV-A plaintiff was not reclassified I-A. Veterans may be

reclassified I-A only with the authorization of the Director of Selec

tive Service. Reg. 1642.12.

10 As of December 31, 1967, there were 15,593,748 registrants in

V-A. Selective Service, February 1968, p. 4.

20

I.

The Federal Courts have jurisdiction to hear and de

termine this suit.

A. Effective Judicial Review of the Classification Orders of

Local Boards Is Constitutionally Required.

An essential ingredient of onr Constitutional system is

the requirement of judicial review of the orders and actions

of administrative agencies. Accompanying the proliferation

of such agencies at all levels of government, has been the

concurrent development of the doctrine of judicial review,

which holds that “ [t]he acts of all . . . officers must be justi

fied by some law, and in case an official violates the law to

the injury of an individual the courts generally have juris

diction to grant relief.” School of Magnetic Healing v.

McAnnuity, 187 U. S. 94, 108 (1902). See also, Abbott

Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U. S. 136, 140 (1967) (and

cases cited therein). This basic principle was clearly stated

by Mr. Justice Brandeis:

“The supremacy of law demands that there shall be an

opportunity to have some court decide whether an

erroneous rule of law was applied; and whether the

proceeding in which facts were adjudicated was con

ducted regularly. To that extent, the person asserting

a right, whatever its source, should be entitled to the

independent judgment of a court on the ultimate ques

tion of constitutionality.” St. Joseph Stock Yards v.

United States, 298 U. S. 38, 84 (1936) (concurring opin

ion). See also, Ohio Valley Water Co. v. Ben Avon

Borough, 253 U. S. 287 (1920).

And Professor Louis Jaffe has concluded that “ . . . in our

system of remedies, an individual whose interest is acutely

21

and immediately affected by an administrative action pre

sumptively has a right to secure at some point a judicial

determination of its validity.” Jaffe, The Eight to Judicial

Review I, 71 Harvard Law Review 401, 420 (1958). Cf.

Hart and Wechsler, The Federal Courts and the Federal

System, 312-40 (1953).

In numerous instances congressional legislation, such as

Sec. 10(b)(3) in issue here, has purported to restrict the

scope or confine the availability of judicial review of admin

istrative orders, but this Court has interpreted such provi

sions to avoid constitutional infirmities. See, e.g., Lipke v.

Lederer, 259 U. S. 557 (1922); Crowell v. Benson, 285 U. S.

22 (1932); St. Joseph Stock Yards v. United States, supra;

Estep v. United States, 327 IJ. S. 114 (1946); Heik-

kila v. Barber, 345 U. S. 229 (1953); Skaughnessy v. Ped-

reiro, 349 U. S. 48 (1955); Brownell v. Tom We Skung,

352 H. S. 180 (1956) yLeedom v. Kyne, 358 IT. S. 184 (1958);

Busk v. Cort, 369 IJ. S. 367 (1962); McCulloch v. Sociedad

Nacional, 372 IJ. S. 10 (1963); see also, 4 Davis, Adminis

trative Law Treatise §28.18 (1958); Jaffe, The Right to

Judicial Review II, 71 Harvard Law Review 769, 770-86

(1958). Illustrative of judicial unwillingness to sanc

tion the claim that illegal administrative action is beyond

judicial scrutiny is Estep v. United States, 327 U. S. 114

(1946). Mr. Justice Douglas, writing for the Court, re

jected the contention that the finality conferred upon local

draft board orders by the Selective Training and Service

Act of 1940 could preclude all judicial inquiry. Such orders

were “ final” only when they were within the board’s “ juris

diction,” either geographical or legal:

“We cannot read §11 as requiring the court to inflict

punishment on registrants for violating whatever

22

orders the local board might issue. "We cannot believe

that Congress intended that criminal sanctions were

to be applied to orders issued by local boards no mat

ter how flagrantly they violated the rules and regula

tions which define their jurisdiction.” 327 IT. S. at 121.

Recognizing that “ [j judicial review may indeed be required

by the Constitution . . . ,” the Court construed the statute

so as to accord only administrative finality to the board’s

order and to insure a necessary measure of judicial review.

Lockerty v. Phillips, 319 U. S. 182 (1943), and Yakus

v. United States, 321 U. S. 414 (1944), both arising

under the Emergency Price Control Act of 1942, are often

cited as extreme examples of judicial deference to congres

sional efforts to preclude federal court jurisdiction and

control over the actions of administrative agencies.11

Lockerty v. Phillips involved a suit to enjoin a threatened

prosecution for violation of administrative orders under

the act. The Court upheld the lower court’s dismissal for

want of jurisdiction. Though there is dicta in that opin

ion which discusses the scope of congressional control

over the jurisdiction of the federal courts, 319 U. S. at

187, that extreme language has not only been criticized by

scholars, see Hart and Weehsler, supra, at 298, but it must

be read within the context of the statutory scheme which

Congress had established. One aggrieved by an order

by the Administrator could complain within the adminis

trative system. But more importantly, he could then ap

peal to the Emergency Court of Appeals, which in its 11

11 FaTbo v. United States, 320 U. S. 549 (1944), is also often cited

in this regard. That decision, however, was thereafter limited

by the decision in Estep v. United States, supra.

23

essentials resembled an Article III court, and finally to

this Court. Thus, the complainant received at least one

opportunity to litigate the legality of the order in a civil

proceeding and seek Supreme Court review before he had

to become a defendant in a criminal prosecution for viola

tion of the order. See Lockerty v. Phillips, 319 U. S. at

188-89. Cf. Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co. v. Kuy

kendall, 265 U. S. 196, 204-05 (1924); Porter v. Investors’

Syndicate, 286 U. S. 461, 471 (1932). Even in Yakus v.

United States, supra, which held that one who failed to

exhaust the special administrative remedies could not chal

lenge the validity of an order as a defense to a criminal

prosecution, the Court noted that there was a preliminary

opportunity to contest the constitutionality of an order in

civil proceedings prior to facing criminal charges for its

violation.

Much more relevant here are the decisions of this Court

which demonstrate that the right to effective judicial re

view cannot be impaired by imposing extreme burdens and

penalties on the exercise of that right. Two cases which

directly support this view are Ex Parte Young, 209 U. S.

123 (1908) and Oklahoma Operating Co. v. Love, 252 U. S.

331 (1920). Young held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s

guarantee of due process required judicial review by civil

suit where a State legislative scheme provided that the only

way to challenge administrative rate-setting was to violate

the prescribed rates and become subject to penalties up to

five years in jail and a $5,000 fine. The Court recoiled at

this deterrent to judicial review:

“ The necessary effect and result of such legislation must

be to preclude a resort to the courts . . . for the purpose

of testing its validity. The officers and employees could

24

not be expected to disobey any of the provisions of the

acts or orders at the risk of snch fines and penalties

being imposed upon them, in case the court should de

cide that the law was valid. The result would be a

denial of any hearing . . .

# * # # #

A law which indirectly accomplishes a like result [mak

ing administrative orders conclusive] by imposing

such conditions upon the right to appeal for judicial

relief as work an abandonment of the right rather

than face the conditions upon which it is offered or may

be obtained is also unconstitutional. It may therefore

be said that when the penalties for disobedience are by

fines so enormous and imprisonment so severe as to

intimidate the company and its officers from resorting

to the courts to test the validity of the legislation, the

result is the same as if the law in terms prohibited

the company from seeking judicial construction of laws

which deeply affect its rights.” 209 U. S. at 146, 147.

The Court held that the remedy at law was so uncertain

and hazardous as to require federal equity to intervene and

protect constitutional rights.

The Love decision carried this rationale of the time at

which judicial review was mandated one step further. It

held that, faced with a legislative scheme similar to that

in Young, which only allowed judicial review of adminis

trative orders by way of defense to contempt proceedings,

a federal equity court could enjoin enforcement of the

orders and the imposition of fines. Mr. Justice Brandeis

held that the right to judicial review could not be made

contingent upon the risk of such penalties:

25

“ Obviously a judicial review beset by such deterrents

does not satisfy the constitutional requirements, even

if otherwise adequate, and therefore the provisions of

the act relating to the enforcement of the rates by pen

alties are unconstitutional without regard to the ques

tion of the insufficiency of these rates.” 252 U. S. at

337.

Both cases establish the principle that judicial review is

constitutionally required at an earlier stage than as a de

fense to a criminal prosecution where the penalty for being

wrong will deter legitimate challenge to the constitutional

validity of a statute, regulation or order.12

Sec. 10(b)(3) was held invalid for this very reason in

Petersen v. Clark, et al., Civil No. 47888 (N. D. Calif. 1968),

in an opinion by Zirpoli, J.13 In Petersen, the complaint

alleged that the plaintiff was conscientiously opposed to

12 More recently, this Court held that an alien seeking to chal

lenge an exclusion order could bring a declaratory judgment suit

to avoid having to face the “ odium of arrest and detention which

a habeas corpus application would involve. Brownell v. Tom We

Shung, 352 U. S. 180 (1956). For other cases which displayed a

similar reluctance to allow the imposition of great burdens on the

right to judicial review of an illegal administrative determination,

see Busk v. Cort, 369 U. S. 367 (1962) and Abbott Laboratories v.

Gardner, 387 U. S. 136, 151-154 (1967). In Reisman v. Caplin, 375

U. S. 440 (1964), a case involving attempts to resist a subpoena un

der the Internal Revenue laws, the Court discussed Young and Love

and concluded that the legislative scheme under review was suffi

ciently free from burdens: “ Finding that the remedy specified by

Congress works no injustice and suffers no constitutional invalidity

we remit the parties to the comprehensive^ procedure of the Code

which provides full opportunity for judicial review before any

coercive sanctions may be imposed.” (Emphasis added.) 375 U. S.

at 450. See pp. 34-41, infra.

13 An original and nine copies of a certified copy of the opinion

have been filed with the Clerk of the Court.

26

participation in war in any form though willing to perform

alternative service and was therefore entitled to a 1-0 clas

sification under Sec. 6(j) of the Act, but that the local board

had unlawfully refused to consider plaintiff’s application

for classification into I-O. After the plaintiff was issued

an order to report for induction, he initiated a lawsuit to

enjoin his induction. Unable to secure a temporary re

straining order, plaintiff refused induction. The case was

then referred to a statutory three-judge court on the

theory that the suit challenged the constitutionality of

Sec. 10(b)(3), but was thereafter remanded to one judge

on the ground that the constitutionality of Sec. 10(b)(3)

was “ merely drawn in question,” rather than challenged

directly as unconstitutional, relying on International Ladies

Garment Workers Union v. Donnelly Garment Company,

304 U. S. 243 (1938).

Plaintiff moved the one-judge court for an order en

joining his prosecution for failing to submit to induc

tion and for an order holding the induction order invalid.

The opinion of Judge Zirpoli followed.

As phrased by Judge Zirpoli, the issue before him in

volved “the specific situation where a federal administra

tive agency places an individual in the position of having

to either: (1) comply with an allegedly invalid order when

compliance may subject him to such restraint of liberty as

military service entails or (2) risk criminal prosecution

to judicially test the order’s validity” (Opinion, p. 4).

First reviewing the power of Congress to regulate the

jurisdiction of the lower federal courts, Judge Zirpoli

concluded that Article III must be read in conjunction with

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment and that

the latter was a limitation upon the former at least where

27

judicial review of administrative action was concerned.

Consequently, relying upon American School of Magnetic

Healing, supra; St. Joseph Stockyards, supra; Ex Parte

Young, supra; Yakus v. United States, supra; Estep v.

United States, supra; and Crowell v. Benson, supra, Judge

Zirpoli concluded that “ Congress cannot make selective

service induction orders wnreviewable. Due process is of

fended by an administrative order which demands com

pliance or a term of imprisonment” (Opinion, p. 14).

Proceeding to the next question, namely, whether Sec.

10(b)(3) is constitutional in confining review to criminal

prosecution, Judge Zirpoli concluded that in general “ judi

cial review cannot be conditioned on the risk of incurring

a substantial penalty or complying with an invalid order”

(Opinion, p. 9), but believed himself obliged, in the selec

tive service context, to balance “ the interests of the govern

ment and the individual . . . to see if what the government

cannot do in other factual situations it may do when the

governmental function involved is the raising of armies”

{ibid.). He held that “ allowing civil review in advance of

criminal prosecution would not disrupt the Selective Ser

vice system” {ibid.), principally on the ground that the

apprehension by the government of litigious interruptions

of the induction process were baseless, that, indeed, “ the

court will experience a net saving in time” because “ the need

for a few trials will be obviated by voluntary compliance

with orders which have been judicially declared valid, and

some time will be saved at trials because the issue of the

order’s validity probably will not have to be litigated.” In

addition, “ the need for calling and empanelling a jury will

be completely eliminated.” Finally, “ since only the timing

and not the scope of review will be affected the number of

men who will ultimately be found to have been validly

classified will not be changed” (ibid.).1*

Thus, there is a constitutionally protected right to judi

cial review and that review cannot be conditioned on harsh

burdens which have the practical effect of denying any re

view at all. Insofar as the courts below have construed

Section 10(b)(3) as placing such extreme penalties on the

registrant who challenges a local board order, it would be

unconstitutional.14 15

B. In Cases Where a Board Order Affects Rights Safeguarded

by the First Amendment, the Federal Courts Have Juris

diction to Protect Those Rights.

Even if Sec. 10(b)(3) is not unconstitutional in the

generality of cases, we believe it should be held inapplicable

14 Meeting the government’s argument that due process is satisfied

by the availability of post-induction habeas corpus, Judge Zirpoli

held that that was inadequate because the registrant must first be

inducted, that induction is the equivalent of compliance with the

allegedly invalid order, that the habeas remedy does not abrogate

the duty to prevent the damage if possible, and that our system

of justice would not tolerate deferring all “ fourth or fifth amend

ment claims or defenses until after a factual finding that a defen

dant committed certain acts and require that they be raised by way

of habeas corpus after confinement” (Opinion, p. 11). The So

licitor General agrees that “ a habeas corpus proceeding after in

duction . . . is a very heavy burden to put on the citizen.” Memo

randum for Respondents, pp. 12-13.

15 Petersen has been followed in the Northern District of Cali

fornia by Harris, J in Gabriel v. Clark, et al., Civil No. 49419.

In Kolden v. Selective Service Local Board No. 4, No. 19,331 (8th

Cir. July 16, 1968), Blackman, J., issued an injunction, pending

appeal, against appellant’s punitive reclassification from II-S and

induction, relying on the grant at certiorari in the case at bar.

Though he did not cite Petersen, Judge Blackman said, that

“Kolden, if relief is not now granted to him, is subject to irrepa

rable injury and that, in contrast, the appellee, if relief is granted,