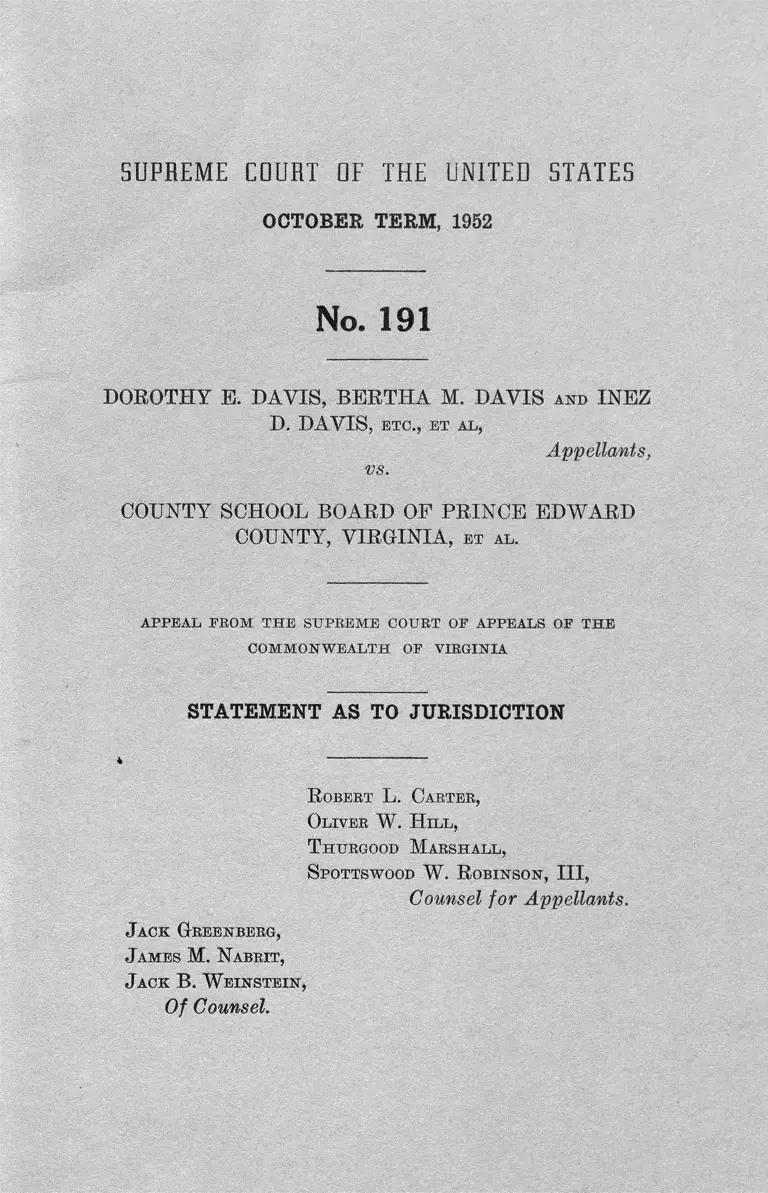

Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Statement as to Jurisdiction

Public Court Documents

May 5, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Prince Edward County, VA School Board Statement as to Jurisdiction, 1952. 1a27753a-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cfb4e24f-2a78-438f-bbc8-a0f26f0eb2c7/davis-v-prince-edward-county-va-school-board-statement-as-to-jurisdiction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

SU P RE M E COURT OF THE UNITED STA T E S

OCTOBER TERM, 1952

No. 191

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, BERTHA M. DAVIS a n d INEZ

D. DAVIS, BTC., ET AL,

VS.

Appellants,

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, e t a l .

APPEAL FROM THE SXJPBEME COURT OB APPEALS OB THE

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

R obert L. Carter,

Oliver W. H ill,

T hurgood Marshall,

Spottswood W. R obinson, III,

Counsel for Appellants.

Jack Greenberg,

James M. Nabrit,

Jack B. W einstein,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OP CONTENTS

S u b je c t I n d ex

Page

Statement as to Jurisdiction.......................................... 1

Opinion B e lo w ........................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................ 2

Questions Presented ............................................. 2

Statutes Involved ................................................... 3

Statement ................................................................ 3

Questions Involved Are Substantial................... 4

1. In offering educational facilities and op

portunities, the state is without power

under the equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to make distinctions among

its citizenry based upon race and color. 6

2. Application of the separate school laws

has resulted in continued and unbroken

discrimination against Negro children

in Prince Edward County in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment............... 12

3. The findings of the court below entitle

appellants to admission at once to the

superior schools in Prince Edward

County...................................................... 16

4. Equal educational opportunities in fact

cannot be provided under Virginia’s

separate school laws................................. 19

5. The decree of the court below fails to

grant appellants effective relief from an

admitted deprivation of their constitu-

tutional rights ..................................... 25

Conclusion ...................................................................... 29

Appendix A .................................................................... 30

Appendix B .................................................................... 38

—2858

11 INDEX

T able oe C ases

Page

American Communications Association v. Dowds, 339

U.S. 389 ...................................................................... 5

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U.S. 219................................... 12

Belton et al. v. Gebhart et al., — Del. Ch. —, -— A.

2d —, decided April 11, 1952..................................... 17

Board of Supervisors v. Wilson, 340 U.S. 909........... 4

Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350....................................... 32

Carr v. Corning, 182 F.2d 14 (C.A.D.C. 1950)'.......... 28, 32

Camming v. Board of Education, 175 U.S. 528.......... 15, 32

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U.S. 285..................... 7

Gonzales v. Sheeley, 96 F.Supp. 1004 (D. Arizona

1951) ....................................................................; 7

Gray v. University of Tennessee, — U.S. —, decided

March 3, 1952 .............................................................. 14

Groessart v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464................................. 7

Guinn v. United States, 283 U.S. 347........................... 12

Hawkins v. Board of Control, 47 So. 2d 608 and 53 So.

2d 116; cert, denied — U.S. —, Nov. 13, 1951.......... 14

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81................. 8

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214................... 8

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.2d 949 (C.A. 4th

1951) ............................................................................ 24

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U.S. 637............. 4

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337......... 14

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633....................... . 8

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537................................. 32

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U.S.

389 ............................................................................... 7

Scott v. Sanford, 19 How. 393...................................... 9

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ..................................... 8

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631..................... 14

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535............................... 7

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649................................... 20

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303..................... 6

Swanson v. University of Virginia, (Civil Action

No. 30, W.D.Va. 1950, unreported)........................... 14,15

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629..................................... 4

Takahashi v. Fish <& Game Commisison, 334 U.S.

410 ................................................................................ 8

ISTDEX

Page

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S.

131 ................................................................................ 28

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25......................................... 6

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356................................. 12

S ta tu te s C ited

United States Statutes:

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281.......... 2

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2284........ 2

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1253......... 2

Title 28, United States Code, Section 2101(b) . . . 2

State Provisions:

Section 140, Constitution of Virginia of 1902, as

amended .............................................................. 3

Section 22-221, Code of Virginia of 1950, as

amended ............................................................. 2, 3,13

Section 22-251, 22-256, Code of Virginia of 1950,

as amended........................................................... 6

O t h e r A u th o r it ie s

American Teachers Association, The Black & White

of Rejections for Military Service (1944).............. 7

Horace M. Bond, The Education of the Negro in the

American Social Order (1934)................................. 10

Horace M. Bond, Negro Education in Alabama

(1939) ....................... 10

Ralph Bunche, The Political Status of the Negro (Un

published manuscript, Carnegie-Myrdal study) . . . 9

Clark, Negro Children, Educational Research Bulle

tin (1923) .................................................................... 7

Henry S. Commager, 1 Documents of American His

tory (1935) .................................................................. 9

Allison Davis, et ah, Deep South (1941)..................... 10

Douglas, Stare Decisis, 49 Col. L. Rev. (1939)............ 20

W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction (1935)............ 10

Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding of

‘ Equal Protection of the Laws,’ 50 Col. L. Rev.

(1950) .......................................................................... 19

iii

IV INDEX

Page

E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States

(1949) ...................................................................................10

Graham, The Early Anti-Slavery Backgrounds of the

14th Amendment, Wis. L. Rev. (1950)..................... 19

Klineberg, Race Differences (1935)............................... 7

Klineberg, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migra

tion (1935) ........................... 7

Paul Lewinson, Race, Class and Party (1932)............. 9

Charles S. Mangum, Legal Status of the Negro

(1940) ......................................................................... 10

Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth— The Fal

lacy of Race (1945) .................................................. _ 7

Peterson & Lanier, Studies in the Comparative Abili

ties of Whites and Negroes, Mental Measurement

Monograph (1929) .................................................... 7

Keport of the Proceedings and Debates of the Con

stitutional Convention, State of Virginia, Rich

mond, June 12, 1901-June 26, 1902, Hermitage

Press, Inc., 1906, Vol. 1 ................................................. 10

Sidney Sutherland, The 14th and 15th and 18th

Amendments, Liberty Magazine V, No. 16, 10

(April 21, 1928) .............................................................. 11

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FDR THE

FDR THE EASTERN DISTRICT DF VIRGINIA

RICHMOND DIVISION

CIVIL ACTION NO. 1333

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, BERTHA M. DAVIS and INEZ

D. DAVIS, I n f a n t s , b y JOHN DAVIS, T h e ir F a t h e r

an d N e x t F r ie n d , et a l .,

vs.

Plaintiffs,

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, an d T. J. McILWAINE, DIVI

SION SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS OF

PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et a l .,

Defendants

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

In compliance with Rule 12 of the Supreme Court of the

United States, as amended, plaintiffs-appellants submit

herewith their statement particularly disclosing the basis

upon which the Supreme Court has jurisdiction on appeal

to review the judgment of the district court entered in this

cause.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, ------F. Supp.------ , has not

yet been reported and a copy of the opinion, along with the

final decree, is attached hereto as Appendix “ A .”

2

Jurisdiction

The district court, convened pursuant to Title 28, United

States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284, entered final judg

ment on 7 March 1952. A petition for appeal is presented

to the district court herewith, to wit, on 5 May 1952. Juris

diction of the Supreme Court to review this judgment by

direct appeal is conferred by Title 28, United States Code,

Sections 1253 and 2101(b) and has been sustained by the

following decisions: McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339

U.S. 637; Board of Supervisors v. Wilson, 340 U.S. 909;

Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350.

Questions Presented

1. Whether Sections 140 of the Constitution of Virginia

of 1902, as amended, and Sections 22-221 of the Code of

Virginia of 1950, as amended, are invalid and unenforce

able under the equal protection and due process clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States because they mandate segregated public

secondary schools for colored children in Prince Edward

County, Virginia, and because they compel infant-

appellants to attend such segregated schools to their detri

ment.

2. Whether after finding that the buildings, facilities,

curricula and means of transportation furnished appellants

are inferior to those provided for white students, the court

below was required by the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States to issue a decree restraining appellees forthwith

from denying appellants admission to the superior state

facilities solely because of their race and color.

3. Whether in addition to parity in curricula and physi

cal facilities the constitution guarantees appellants equality

3

in all other educationally. significant factors affecting the

development of skills, mind, and character.

Statutes Involved

Section 140 of the Constitution of Virginia of 1902, as

amended, and Section 22-221, Code of Virginia of 1950, as

amended, are set forth in Appendix “ B ” hereto.

Statement

Appellants are colored persons defined by law in the

state of Virginia as a person with “ any” “ ascertainable”

Negro blood and are citizens of the state of Virginia and

of the United States and residents of Prince Edward

County. They are: (1) children of public school age at

tending secondary public schools in Prince Edward County;

and (2) the parents and guardians of these children. Ap

pellees are state officers charged with the duty and re

sponsibility of providing, operating and maintaining public

elementary and secondary schools in Prince Edward

County, Virginia.

Section 140 of the Constitution of Virginia of 1902, as

amended, and Section 22-221 of the Code of Virginia of

1950, as amended, compel appellees to maintain separate

schools for colored and white children. Appellants are

seeking to enjoin enforcement of these provisions on the

grounds that they are in direct conflict with the equal

protection and due process clauses of the Fourtenth Amend-

Amendment.

Three public high schools are now in operation in the

county—the Moton High School for colored children and

the Worsham and Parmville High Schools for white chil

dren. The Moton High School has a larger enrollment (Tr.

37), average daily attendance and average daily member

ship (Tr. 77) than the combined totals at the other two

schools.

4

Appellees admitted in their answer and in their opening

statement that the buildings and equipment of the Negro

school were inferior to those of the white schools but alleged

that equal educational opportunities were furnished in all

other respects, (Tr. 9010). Blueprints of a proposed new

Negro high school designed to correct the inequalities in

physical facilities by September 1953 were placed in evi

dence (Tr. 521-541).

After hearing the evidence, the court below found the

Moton High School inferior not only in buildings and

equipment, but also in curricula and means of transporta

tion as well. Appellees were ordered forthwith to provide

appellants with curricula and means of transportation

“ substantially” equal to that available to white high school

students. Appellees were also ordered to “ proceed with

all reasonable diligence and dispatch to remove the in

equality existing as aforesaid in said buildings and facili

ties, by building, furnishing and providing a high school

building and facilities for Negro students, in accordance

with the program mentioned in said opinion and in the

testimony on behalf of the defendants herein, or other

wise . . . ” (See Appendix “ A ” .) As indicated, according

to appellees’ testimony, this new high school will not be

available until September 1953 (Tr. 541).

The court refused either to enjoin enforcement of the

state constitutional and statutory provisions requiring the

maintenance of radically segregated schools or to restrain

appellees from assigning school space in the county on the

basis of race and color.

Questions Involved Are Substantial

The issues raised in this case are similar to those raised

in Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629; McLaurin v. Board of

Piegents, 339 U.S. 637; and Board of Supervisors v. Wilson,

340 U.S. 909. Under the federal constitution, appellants

5

are entitled to equal state educational opportunities. Since

the Negro high school was found to be inferior in bus

transportation, curricula, buildings and facilities, appel

lants are entitled to effective and immediate relief. Such

relief, we submit, requires the issuance of a decree which

permits appellants to share now in the superior state

facilities without regard to their race or color. A decree

that does less makes meaningless appellants’ constitutional

rights to equal educational opportunities.

Moreover, without regard to the present inequality with

respect to physical facilities, appellants contend that the

racial barriers and restrictions mandated by the state sep

arate school laws block the full and complete development

of their educational potential and make it impossible for

them to benefit from public education to the same extent

as white children. Thus by enforcing its invidious racial

classifications and distinctions among children of public

school age in Prince Edward County, as well as by fur

nishing appellants inferior physical facilities because of

race, the state violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

This is not only a local problem but is a question with

both national and international implications. The full

development of human resources of this country are

certainly as important to the nation and the world as the

full development of our natural resources, such as steel,

aluminum, coal and oil. As Mr. Justice Jackson said in

American Communications Association v. Douds, 339 U.S.

383, 442: ‘ ‘ Thoughtful, bold and independent minds are

essential to wise and considered self-government.” Inso

far as a majority of the public school population in Prince

Edward County is retarded in the full development of its

mental resources, the state of Virginia and the United

States are weakened in their efforts to develop that strong,

enlightened citizenry essential to the preservation of our

democratic institutions.

6

1. In offering educational facilities and opportunities,

the state is without power under the equal protection and

due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to make

distinctions among its citizenry based upon race and color.

Sections 22-251 to 22-256 of the Code of Virginia of 1950,

as amended, require that all children between the ages of

7 and 16 attend public school or receive instruction in pri

vate schools. The state provides free public elementary and

secondary education. Negro children, whose parents object

to their attending racially segregated schools, must seek

their education in states where racial segregation is not

practiced. To most there is, therefore, no practicable alter

native to attending the segregated public schools.

While appellants have no abstract or natural right to a

public school education, as Mr. Justice Frankfurter noted

in his concurring opinion in American Communications

Association v. Bonds, supra at 417, the government is under

no obligation to furnish any public facilities, but once it

does it cannot make its facilities “ available in an obviously

arbitrary manner nor exact surrender of freedoms unre

lated to the facilities.” In this case, the state tells appel

lants that they must attend school, but if they choose to

attend the schools which the state maintains, they must

attend the segregated Moton High School solely because

they are Negroes.

The Fourteenth Amendment was designed to secure full

and equal citizenship rights for Negroes; it made freedom

from state action based upon race or color fundamental to

our way of life Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303.

Protection of this freedom is secured by due process which

is “ the compendious expression for all those rights which

courts must enforce because they are basic to our free

society . . . ” Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25, 27. In requiring

appellants to attend specially designated public schools

solely because of their color, the state denies to them the

7

enjoyment of a freedom and liberty which they would

otherwise have except for the fact that they are Negroes.

In the infringement of this freedom, the state has further

magnified the harm to which appellants are subjected by

requiring them to attend inferior schools and to receive

inferior educational advantages.

As to equal protection, it must be conceded that a state

may classify its citizenry to accomplish some legitimate

governmental objective Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249

U.S. 265; Groessart v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464. The classifi

cation, however, must be based upon some real difference

pertinent to a lawful legislative end. Quaker City Cab Co.

v. Pennsylvania, 277 U.S. 389; Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316

TJ.S. 535. Admittedly the only difference between appellants

and white public school children is a difference of race and

color, and this cannot be considered a difference in the con

stitutional sense.

The state has not attempted to show, nor can it show, that

this separation is based upon inherent differences between

appellants and white children in the county because of

their racial origin.1 There is not even here the question

of language differences upon which Arizona unsuccessfully

sought to sustain the segregation of children of Mexican

descent. Gonzales v. Skeeley, 96 F. Supp. 1004 (D. Ari

zona, 1951). As the court declared at 1008, 1009:

“ Segregation of school children in public school

buildings because of racial or national origin . . . consti

tutes a denial of equal protection of the laws as guaran

teed . . . by the provisions of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.”

1 Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth— The Fallacy of Race, 188

(1945) ; American Teachers Association, The Black & White of Rejec

tions for Military Service 5 at 29 (1944) ; Klineberg, Negro Intelligence

and Selective Migration (1935); Peterson & Lanier, Studies in the Com

parative Abilities of Whites and Negroes, Mental Measurement Mono

graph (1929) ; Clark, Negro Children, Educational Research Bulletin

(1923); Klineberg, Race Differences 343 (1935).

8

The purposes of public education in Virginia, defined in

its official pronouncements, is to develop fundamental skills,

provide experience for emotional, moral and social develop

ment, develop good citizenship in a democracy, provide

studies appropriate to the child’s needs and aptitudes, pre

pare students for occupations and college and serve adults

by providing facilities needed as they attempt to solve the

problems of life (Tr. 46-47). There is no rational con

nection between these aims and racial segregation. Thus

the separate school laws not only fail to satisfy the con

stitutional requirements of due process, but also equal

protection of the laws. They are, therefore, invalid under

both provisions.

Indeed, we take the unqualified position that the Four

teenth Amendment has totally stripped the state of power

to make race and color the basis for governmental action.

See Skinner v. Oklahoma, supra, at 541. While an excep

tion may be made with respect to the federal government

in a grave national emergency, Hirabayashi v. United

States, 320 U. S. 81; Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S.

214, no state can show any such overriding necessity which

would warrant sustaining state action founded upon these

constitutionally irrelevant and arbitrary considerations.

See Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633; Takahashi v. Fish

and Game Commission, 334 IT.S. 410; Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 IT. S. 1. For this reason alone, we submit, the state

separate school laws in this case must fall.

In our view, the law also violates the privileges and im

munities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Under that

Amendment a privilege and immunity incident to national

citizenship is freedom from governmental restrictions

founded upon race.

Appellants contend further that the state separate school

laws are motivated by racial prejudice and are based upon

9

a belief in the inherent inferiority of the Negro directly

flowing from his racial origin and that they are invalid for

this additional reason. Cf. Korematsu v. United States,

supra, at 216; Oyarna v. California, supra, at 646; and see

concurring opinion of Mr. Justice Murphy in Takahashi v.

California, supra, at 412, 427.

The court below concluded that the state school segre

gation laws are not the result of racial animosity or an

tipathy, but declare “ one of the ways of life in Virginia”

and are “ a part of the mores of her people.” ''See Appen

dix “ A ” .) The available historical evidence does not sus

tain these conclusions. Doubts concerning the status of

the free Negro prior to the Civil War were resolved by the

Dred Scott decision which expressly decided that a Negro

had no citizenship rights equal to those enjoyed by a white

person.2 After the Civil War the Negro was affirmatively

granted full and equal citizenship by the Thirteenth and

Fourteenth Amendments, and the legal basis for racial

distinctions inherent in the institution of slavery was de

stroyed. The white South, however, not content with this

constitutional change, immediately undertook to reestablish

the Negro status to accord with the ante-bellum philosophy

expressed in the Dred Scott decision.

These attempts were first manifested in the Black Codes

(1865-1866) which in many instances permitted the effec

tive reestablishment of slavery through the apprenticeship

system.3 Subordination of the Negro was temporarily re

strained by Congress but between 1870-1871 gained momen

tum in North Carolina, Virginia and Georgia4 and through

out the South after the Presidential election of 1877.5

2 Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. 393.

3 Henry S. Commager, 1 Documents of American History 5 (1935);

Paul Lewinson, Race, Class and Party, 34 (1932).

4 Bunche, The Political Status of the Negro, 1, 230 (Unpublished manu

script, Carnegie-Myrdal study.)

B Bunche, op. cit. supra note 5 at 230-233,

10

Implicit in the plan to relegate the Negro to a subordinate

political, economic and social status was the separate school

system. There was determined resistance to any public

education whatsoever for the Negro, and where public edu

cation was provided, there was resistance to affording such

education in mixed schools. Mixed education was in fact

undertaken in Louisiana and South Carolina, but proponents

of mixed schools were- persuaded that abandonment of

mixed schools woplft help the cause of public education

throughout the- South.6

The records of the southern state constitutional conven

tion, 1890-1910, reveal that segregation was looked upon

js 'a means of giving the Negro as little education as possible

and of assuring the progress of white education unham

pered by the economic burden of Negro education.7 Equality

under segregation in education was never intended, and

certainly has never been achieved.8

At the Constitutional Convention for the state of Vir

ginia, 1901-1902, devices were specifically sought which

would give the Negro as little education as possible,9 and to

6 Horace M. Bond, The Education of the Negro in the American Social

Order, 37-57 (1934).

7 E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro in the United States, 421-427 (1949).

8 Charles S. Mangum, Legal Status of the Negro, 132-133 (1940);

W. E. B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction, 642-677 (1935) ; Allison Davis,

et al., Deep South, 240, 417-419 (1941) ; H. M. Bond, Negro Education in

Alabama, 190 (1939).

8 Report of the Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Conven

tion, State of Virginia, Richmond, June 12, 1901-June 26, 1902, Hermitage

Press, Inc., 1906. In the debate over a resolution that state funds for

schools must be used to maintain primary schools for four months before

these funds could be used for establishment of schools of higher grades,

the following exchange took place. See Vol. 1, p. 1677:

Mr, Turnbull:

“ Might not the effect of this provision be to tend to prevent the estab

lishment of schools in sections of the country where it ought to be

prevented?”

Mr. Glass:

“ I do not think so. Those matters were discussed. The committee dis

cussed this provision perhaps more earnestly and longer than any other

11

make certain that he remained in an inferior position. The

late Senator Carter Glass, who was a delegate at the Con

vention, took a relatively moderate position. During the

course of the debates he stated:10

“ Discrimination! . . . that is precisely what we pro

pose ; that, exactly, is what this convention was elected

for—to discriminate to the very extremity of permis

sible action under the limitations of the Federal Con

stitution, with a view to the elimination of every Negro

voter who can be gotten rid of, legally, without mate

rially impairing the numerical strength of the white

electorate. ’ ’

As late as 1928, in commenting upon the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments and the South, Walter F. George of

Georgia—now Senator—declared :u

“ No statutory law, no organic law, no military law,

supersedes the law of racial necessity and social iden

tity.

“ Why apologize or evade? We have been, very care

ful to obey the letter of the Federal Constitution—but

we have been very diligent and astute in violating the

spirit of such amendments and such statutes as would

lead the Negro to believe himself the equal of a white

man. ’ ’

Thus, it is clear that the purpose and intent of Virginia’s

separate school laws was to avoid according to Negroes

the full citizenship rights which the Fourteenth Amendment

provision contained in this report; and as I have said, it was a discussion

to this very demand— certainly in my judgment a very reasonable demand

—that the white people of the black sections of Virginia should be per

mitted to tax themselves, and after a certain point had been passed,

which would safeguard the poorer classes of those communities, divert

that fund to the exclusive use of the white children, and I do not think

we ought to go beyond that point.”

10 Lewinson, op. cit. supra, at 86.

11 Sidney Sutherland, “ The 14th, 15th and 18th Amendments,” Liberty

Magazine, V, No. 16,10 (April 21, 1928).

12

was designed to secure. On this basis alone, we submit,

these laws should be struck down.

In summation, appellants contend that these state laws

violate due process, deny the equal protection of the laws,

abridge a privilege and immunity of national citizenship,

exceed the permissible limits of state power and are moti

vated by racial prejudice. For each and all of these reasons,

we submit, the laws must fall.

2. Application of the separate school laws has resulted

in continued and unbroken discrimination against Negro

children in Prince Edward County in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Even assuming that Virginia had a proper motive in

the enactment of its separate school laws, an examination

of the natural and actual effect of these laws—which is

clearly relevant to a determination of constitutionality,

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219; Guinn v. United States,

283 U. S. 347; Yiclt Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356—discloses

that in Prince Edward County public educational facilities

for Negroes are inferior to those available for white chil

dren and that this condition has existed for a continuous

period of at least thirty-four years. The present Super

intendent of Schools of Prince Edward County took office

in 1918 and has held the position ever since (Tr. 638-639).

Although a high school for white children was available

when he took office, no high school facility of any sort was

open to Negroes until 1927-1928 when a combination ele

mentary-high school was erected; no accredited high school

was available until 1931; in 1924-25, public school bus trans

portation was made available for whites, but it was not

until 1938 that such transportation was offered to Negroes

(Tr. 639-642). Discrimination in salary between teachers

in the white schools and teachers in the Negro schools was

in effect in 1918, and no steps were made to end this

13

practice until 1940 (Tr. 645-646). At no time during the

thirty-four year period in the regime of the present Super

intendent have physical school facilities for Negroes been

equal to those available for white children. These are

the undisputed facts.

The inequality which existed when the present Super

intendent took office necessarily predated 1918. It is, there

fore, fair to conclude that educational opportunities for

Negroes have never been equal to those for white children

in Prince Edward County under the separate school laws.

The present Superintendent knew that school facilities for

Negro children were inferior when he took office in 1918.

The present school board knew of the dissatisfaction among

Negro citizens with conditions at the Moton High School

at least as long ago as December of 1947 (Tr. 463). The

school board even ordered a school survey which was

completed in 1948 (Tr. 464-465), yet no affirmative steps

were taken to remedy this discrimination until after the

present law suit was filed in 1951.

Section 22-221 of the State Code, which has been in force

since 1869-70, provides that the separate schools be under

the “ same general regulations as to management, useful

ness and efficiency.” If this provision is interpreted as

requiring equality, it has been ignored as scrupulously as

the requirement for separation has been observed.

While it may be true, as the district court pointed out,

that separate schools have been “ one of the ways of life

of Virginia,” systematic and deliberate discrimination

against Negroes has been its inevitable result in Prince

Edward County.12 Appellants are seeking to modify that

12 Nor does the situation in Prince Edward County differ materially in

this regard from that in the rest of the state. The opinion of the district

court indicates that in a large number of counties and cities in Virginia

the schools and facilities for Negroes are equal and superior to those

14

way of life so that it will conform with the requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The records of this Court disclose beyond cavil that the

“ separate but equal” doctrine has not provided equal edu

cational opportunities consistent with the demands of the

federal Constitution. In 1938, this Court held that a state

had to provide equal legal facilities for Negro applicants

within the state or admit them to the state university de

spite segregation laws. Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337. This decision gave notice to all that states

could not provide legal training without making provi

sions for training of Negro applicants on the same basis.

Yet, ten years later Oklahoma was still attempting to do

just that. Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631. Until

the case of Sweatt v. Painter, supra, had been in the state

court for about a year, no law school other than the Uni

versity of Texas was available. In Hawkins v. Board of

Control, 47 So. 2d 608 and 53 So. 2d 116 (Fla.) ; cert. den.

U. S. , November 13, 1951, for want of final judg

ment, and in Gray v. University of Tennessee, U. S. ,

decided March 3, 1952, the only law schools available were

at the state universities to which Negroes had been denied

admission. In Virginia, a court decree in Swanson v. U n

available for white children. There is nothing in the record to justify this

broad conclusion.

Uncontroverted testimony was introduced to establish those facts only

with respect to high school buildings (Tr. 545-547), but that evidence

is not a sufficient basis for the court’s unqualified statement.

As a matter of fact, the Annual Report of the State Superintendent

of Public Instruction for 1950-1951, pages 322-324, discloses that in every

city and county in Virginia the white schools are superior to Negro

schools in terms of value of sites and buildings, value of furniture and

equipment, and value of school buses. Appellants took the appellees’ own

figures and demonstrated at the trial without challenge that for every

dollar the state had spent on instruction in white schools, eighty-five

cents had been spent in the Negro schools in 1933-1934; and that in 1950

the figure in the Negro schools had increased to eighty-nine cents (Tr.

955-g-h) ; that taking into account the state’s ambitious construction

program even after these proposed projects are completed, for every

dollar invested in sites and buildings in the white schools, seventy-four

cents would have been invested in Negro schools (Tr. 956).

15

versity of Virginia, unreported, Civil Action No. 30, (W.D.

Va. 1950) was necessary to secure admission of a Negro

to the only state facility where legal training was being-

offered.

In all the cases which heretofore have reached this Court

involving the equality of educational opportunities as be

tween the segregated and nonsegregated groups, either

the separate facilities have been inferior to those available

to other racial groups or nonexistent. Camming v. Board

of Education, 175 U. S. 528; Missouri ex rel Gaines v.

Canada, supra; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra; Sweatt

v. Painter, supra; McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra;

Gray v. University of Tennessee, supra. The present case

falls into the same pattern. The “ separate but equal”

theory as a rule of law has been a total failure in provid

ing that protection against racial discrimination which

was concededly one of the primary purposes of the Four

teenth Amendment. Shelley v. Kraemer, supra. Acutal

experience has demonstrated the fallacy of the theory and

it should now be discarded.

With respect to the operation of the separate school

laws in this case, this Court is in exactly the same posi

tion as it was in Tick Wo v. Hopkins, supra. There, after

finding that the ordinance in question made possible uncon

stitutional discrimination against Chinese solely because

of race, the Court struck it down. It declared at 373:

“ . . .w e are not obliged to reason from the probable

to the actual . . . For the cases present the ordinances

in actual operation, and the facts shown establish an

administration directed so exclusively against a par

ticular class of persons as to warrant and require the

conclusion that . . . with a mind so unequal and

oppressive as to amount to a practical denial by the

State of that equal protection of the laws which is

secured , , , the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

16

tution of the United States. Though the law itself he

fair on its face and impartial in appearance, yet, if it

is applied and administered by public authority with

an evil eye and an unequal hand, so as practically to

make unjust and illegal discrimination between per

sons in similar circumstances, material to their rights,

the denial of equal justice is still within the prohibition

of the Constitution. ’ ’

The separate school laws make possible discrimination

against Negroes because of their color, deliberate and

invidious discrimination has been its actual result for more

than thirty-four continuous years in Prince Edward County.

No law should be allowed to stand where discrimination

forbidden by the federal Constitution is made possible

and indeed actually and inevitably results. Yick Wo v.

Ilopkins, supra.

Looking at the application of these laws in Prince Edward

County, the conclusion is inescapable, we submit, that

appellants’ rights as guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment can only be secured if the state’s separate

school laws are held unconstitutional, and appellees are

required to admit appellants to the superior schools in the

county without regard to race or color.

3. The findings of the court below entitle appellants to

admission at once to the superior schools in Prince Edward

County.

In Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, supra, at 352, this

Court, even without a record showing the injury incident

to racial segregation, held that a Negro applicant must

be admitted to the state university “ in the absence of

other and proper provisions for his legal training. ” “ The

admissibility of laws separating the races in the enjoyment

of privileges afforded by the State rests wholly upon the

quality of the privileges which the laws give the separated

17

groups within the State.” Id at 349. Subsequently, in

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra, the state was held under

obligation to furnish educational opportunities for Negro

applicants as soon as these were furnished any other group.

Finally, in Sweatt v. Painter, supra, after finding the state

had failed to provide equal educational opportunities to a

Negro applicant, this Court said at pages 635, 636: “ . . . pe

titioners may claim his full constitutional right: legal edu

cation equivalent to that offered by the State to students

of other races . . . the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment requires that petitioner be ad

mitted to the University of Texas Law School.”

Eights secured under the Fourteenth Amendment are

personal and present, Sweatt v. Painter, supra, at 605;

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, supra; Shelley v. Kraemer,

supra; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra; Missouri ex rel

Gaines v. Canada, supra, and having established a clear

and unmistakable violation of these constitutional guaran

tees, appellants are entitled to full and effective relief at

once which in this instance is their immediate admission

to the white schools. It should be remembered that appel

lants are high school students. For many this represents

their last opportunity to obtain equal educational oppor

tunities. A decree effective at some future time when the

state gets around to completing a new Negro high school

after they graduated will mean in fact that they will secure

no relief.

In Belton et al. v. Gebhart et aL, Del. Ch,, A 2d ,

decided April 1, 1952, the Delaware Court dealt with the

same problem raised here. The state presented evidence

to show that it was engaged in a building program designed

to better the Negro schools and argued that under such

circumstances, the court should merely direct the equaliza

18

tion of facilities and allow the state time to comply with

such an order. While recognizing that some courts in

similar cases had taken this course, Chancellor Seitz rejected

this proposal on the grounds that where a showing has

been made of an existing and continuing “ violation of the

‘ separate but equal’ doctrine, [a Negro applicant] is en

titled to have made available to him the State facilities

which have been shown to be superior. ’ ’ Otherwise, he said,

a complainant would be told that although his constitutional

rights had been violated, he would have to patiently wait

for the court to find out whether they were still being

violated at some future date. “ To postpone such relief is

to deny relief, in whole or in part, and to say that the

protective provisions of the Constitution offer no imme

diate protection.” The court concluded that despite the

state’s future plans, immediate injunctive relief was nec

essary and issued a decree restraining the state from deny

ing admission to the white school based upon race and

color.

The only basis upon which the court below could have

sustained the constitutionality of Virginia’s separate school

laws is under the “ separate but equal” doctrine. While

appellants contend that their rights should not be measured

by that formula, and that no state has power to make

racial distinctions among its citizenry with respect to edu

cational facilities, certainly they are entitled to no less

than the Plessy v. Ferguson doctrine requires, i.e., equal

educational opportunities.

While upholding the constitutionality of the segrega

tion of appellants in the public high schools of Prince

Edward County, the court below found that equal educa

tional opportunities with respect to buildings, facilities,

curricula and means of transportation were not being of

fered at the Moton High School and would not be offered

19

until 1953.13 Since a sine qua non to a finding of constitu

tionality even under the minimum constitutional standard—

the “ separate but equal” doctrine—is the equality of the

facilities provided for the segregated group, the state in

this case has failed to build the constitutional flooring

essential to its argument that its separate school laws are

valid. Under these circumstances the court below was at

least obligated to order appellants’ admission to the supe

rior schools without regard to the state’s policy of racial

segregation. In failing to issue such a decree, the court

below committed a fatal error, and its judgment should

be reversed.

4. Equal educational opportunities in fact cannot be

provided under Virginia’s separate school laws.

Controversy has raged for many years over the question

as to whether the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment

specifically intended to deprive the state of power to pro

mulgate and enforce racial segregation in public schools.

Modern-day scholars have demonstrated that racial segre

gation was one of the evils which the framers of the Four

teenth Amendment sought to eradicate.14 It has always

been clear and undisputed, however, that the Fourteenth

Amendment sought to secure forever against state abridg

ment full and equal civil and political rights for Negroes.

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, at 23. It is against this undis

puted objective that Virginia’s separate school laws must

be measured.

18 Appellants introduced evidence to show that even when the new

Moton High School is completed, for every dollar spent on white high

school buildings and facilities in Prince Edward County, eighty-two

cents would be spent for Negro schools (Tr. 958).

14 E.g., see Graham, “ The Early Anti-Slavery Backgrounds of the 14th

Amendment,” Wis. L.Rev., 478, 610 (1950) ; Frank and Munro, “ The

Original Understanding of ‘Equal Protection of the Laws,’ ” 50 Col.

L.Rev. 131 (1950).

20

Racial segregation has been sustained in the past under

the “ separate but equal” philosophy. Upon the evidence

introduced at the trial of this case, there is little doubt that

appellants have been subjected to invidious discrimination

under the shield of the segregation laws. Whatever inter

pretation may have been placed upon the Constitution by

past courts, constitutional guarantees can only be given

meaning and vitality in the light of present knowledge

and experience. See Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 665;

see also Douglas, Stare Decisis, 49 Col. L. Rev. 735 (1939).

It is difficult to conclude today that separate schools can

ever be equal schools.

Appellants contend that they have been denied equal edu

cational opportunities in Prince Edward County because

they are required to attend racially segregated schools

and that these schools are in fact inferior to schools which

the state provides for white children. The court has found

that the segregated schools are inferior with respect to

buildings, facilities, curricula and means of transportation.

Appellants contend that in deciding the constitutional

question involved here—whether appellants are receiving-

equal educational opportunities—the inquiry cannot be

limited to a comparison of curricula and physical facilities

alone but must embrace every significant factor which

relates to educational and mental development.

Appellants introduced experts in the fields of education

and psychology who testified that racial segregation stig

matizes the Negro child with a sense of inferiority; that

it impedes the natural development of his mental resources;

that it is conductive to the development of an unhealthy

personality; and that it bars contact with the dominant

groups in the community thereby making it impossible for

the Negro child to receive educational opportunities equal

to those which would be available to him in an unsegregated

21

school system (Tr. 241, 276, 318-321, 391-393, 404-406). Cf.

Siveatt v. Painter, supra. Appellees introduced experts

in the fields of education, psychology and psychiatry to*show

that given equal facilities in a separate school, the Negro

would receive equal educational opportunities.

As to this phase of the case, the court said that appellants

had introduced expert witnesses who unanimously agreed

that segregation in schools “ immeasurably abridged [the

Negro child’s] educational opportunities” ; and that on the

other hand appellees had introduced equally distinguished

expert witnesses who agreed that given equal physical

facilities, offerings and instruction, “ the Negro would re

ceive in a separate school the same educational opportunity

as he would obtain in the classroom “ and on the campus

of a mixed school . . . On this fact issue the Court cannot

say that the plaintiffs’ evidence overbalances the defend

ants.” (Appendix “ A ” .)

Four experts in education testified for appellees—Dr.

Colgate Darden, President of the University of Virginia

and former Governor of the State (Tr. 741-761) ; Dr. Dabney

Lancaster, President of Longwood College (Tr. 762-793) ;

Dr. Dowell J. Howard, State Superintendent of Public

Instruction (Tr. 717-740); and Dr. Lindley Stiles, Dean of

the Department of Education of the University of Virginia

(Tr. 803-855). All testified that segregated schools with

equal facilities would be better for Negroes than mixed

schools and expressed fear of withdrawal of public support

if segregation were abolished.

Appellees’ witness, Dr. Darden, however, stated that seg

regation in many instances had been used as a shield for

oppression, discrimination and mistreatment although he

was of the opinion that this should not necessarily follow

from segregation (Tr. 752).

Appellees’ witness, Dr. Stiles, stated that he could not

accept segregation as a social practice (Tr. 825), and that

22

to the degree that Negroes are given equal educational

opportunities to learn and to the extent that all Virginians

get better schools, segregation was in the process of being

abolished (Tr. 826). He said that the debate was not

over whether society could or should be cured of the ail

ment of segregation, but rather on how to treat the disease

(Tr. 825-827). With better education for both groups,

he felt the time would come when segregation would be

considered unnecessary (Tr. 835).

Also testifying for appellees were Dr. William Kelly, a

psychiatrist and Director of the Memorial Foundation

and Memorial Guidance Clinic, Richmond, Virginia (Tr.

856-883) ; John Buck, a retired clinical psychologist (Tr.

884-910) ; and Dr. Henry E. Garrett, Chairman of the

Department of Psychology, Columbia University (Tr. 911-

955C). Again, all voiced the opinion that Negroes could

get equal training in separate schools.

Appellees’ witness, Dr. Kelly, while of the opinion that

segregation was going to end, feared its abrupt termina

tion (Tr. 871 and 875). He conceded, however, that racial

segregation was adverse to the personality development

of the individual, although lie expressed doubt that its

elimination would per se change the personality defect

or remove the adverse influence (Tr. 882).

Appellees’ witness, Mr. Buck, stated that racial segre

gation in the abstract was bad (Tr. 903), and that it was

the consensus of members of his profession that segrega

tion was harmful, although he felt the harm done depended

upon many other circumstances (Tr. 908).

Appellees’ witness, Dr. Garrett, felt that segregation

could not be defended if the segregated group is stigma

tized or put into an inferior position, but that the mere

fact of segregation did not necessarily mean discrimination

(Tr. 920-921). In view of the present state of mind of

Virginia and given equal facilities, it was Ms feeling that

Negro children could get a better education in segregated

schools (Tr. 953). However, in answer to a question as

to whether segregation as practiced in the United States

today was harmful, Dr. Garrett stated : “ In general, when

ever a person is cut off from the main body of society or

a group, if he is put in a position that stigmatizes him

and makes him feel inferior, I say, yes, it is detrimental

and deleterious to him.” (Tr. 954.)

Thus, four of appellees’ seven expert witnesses admit

that segregated schools have harmful effects on Negro

children, and while favoring the eventual elimination of

separate schools, they presently support the immediate

preservation of separate schools primarily because of the

climate of public opinion in the state. A fifth witness for

appellees recognized that segregation made possible racial

discrimination. Only two of appellees’ witnesses gave un

qualified support to the state practice, and even they placed

emphasis upon public opinion.

Whether segregation in the public schools of the state

is a wise or sound policy is not involved in this litigation;

nor can the state practice be defended on the grounds

that even if removed appellants will be no better off since

the teachers and white students might not accept them.

This Court dealt firmly with that argument in McLaurin v.

Board of Regents, supra, at 641, 642, where it said:

‘ ‘ It may be argued that appellant will be in no better

position when these restrictions are removed, for he

may still be set apart by his fellow students. This we

think irrelevant. There is a vast difference—a Con

stitutional difference—between restrictions imposed by

the state which prohibit the intellectual commingling

of students, and the refusal of individuals to commingle

where the state presents no such bar. The removal

of the state restrictions will not necessarily abate in

24

dividual and group predilections, prejudices and

choices. But at the very least, the state will not he

depriving appellant of the opportunity to secure accept

ance by his fellow students on his own merits.”

And as Judge Soper noted in McKissick v. Carmichael,

187 F. 2d 949, 953, 954 (CA 4th 1951) the state cannot suc

cessfully defend against the assertion of constitutional

rights on the grounds that it is in the individual’s interest

that he be deprived of them. We quote his apt language:

“ . . . the defense seeks in part to avoid the charge

of inequality by the paternal suggestion that it would

be beneficial to the colored race in North Carolina as

a whole, and to the individual plaintiffs in particular,

if they would cooperate in promoting the policy adopted

by the State rather than seek the best legal education

which the State provides. The duty of the federal

courts, however, is clear. We must give first place

to the rights of the individual citizen, and when and

where he seeks only equality of treatment before the

law, his suit must prevail. It is for him to decide in

which direction his advantage lies.”

It must be remembered that the Fourteenth Amendment

requires that the state not deny to appellants, because

of race, educational opportunities equal to those it furnishes

other groups. Only if it were possible to resolve that ques

tion in terms of physical facilities would it be appropriate

to limit the reach of the constitutional mandate to that

phase of the educational picture alone. That the consti

tutional guarantee of equal educational opportunities in

volves more than mere equal physical offerings was settled

beyond doubt in the McLaurin decision. Whatever may be

the present force of the Plessy v. Ferguson “ separate but

equal” doctrine, it is now too late for a court to determine

constitutional equality on the basis of physical facilities

alone as that case seems to imply.

25

Appellants have demonstrated that racial separation in

public schools as practiced in Prince Edward County injures

appellants and is adverse to their educational development.

With this basic thesis at least four of appellees’ expert

witnesses agree. These were the considerations which were

the basis of the McLaurin decision. If the state practice

produces harm forbidden by the Constitution, the fact that

a majority of the state’s population does not want the

practice changed or that it has become a feature of the

state’s way of life cannot insulate the practice against the

reach of the Constitution. Since it has been demonstrated

that segregation in the public schools in Prince Edward

County is injurious and adverse to appellants, we submit

that the separate school laws are forbidden by the Four

teenth Amendment and should be struck down.

5. The decree of the court below fails to grant appellants

effective relief from, an admitted, deprivation of their con

stitutional rights.

The court below found that Moton school is unequal with

respect to curricula and issued a decree designed to imme

diately remove discrimination in this category. Serious

questions arise, however, concerning the meaning of this

decree and the problem of enforcement presents, in our

view, insurmountable difficulties.

In its opinion the trial court stated that:

. . we find physics, world history, Latin, advanced

typing and stenography, metal and machine shop

work and drawing, not offered at Moton, but given in

the white schools.”

We assume that under this decree appellees must provide

at Moton at once courses in physics, world history, Latin,

advanced typing and stenography, metal and machine shop

work and drawing. Yet as to physics, metal and machine

shop work and drawing, there are deficiencies at Moton

26

in the equipment and facilities essential to the proper

teaching of these courses.

The court was not unaware of these deficiencies in facili

ties and equipment. For it is specifically stated in the

court’s opinion that the iVIoton. school lacks a gymnasium,

showers, o r :

“ dressing rooms to accompany physical education

or athletics, no cafeteria, no teachers’ restroom and

no infirmary to give some of the items lacking in Moton

lout present in the white school. Moton’s science equip

ment and facilities are lacking and inadequate. No

industrial art shop is provided . . . ” (emphasis sup

plied)

Inequalities in buildings and facilities under the court’s

decree need not be removed until the new Moton High

School, promised for occupancy in September, 1953, is

completed.

Either appellees must provide equality in curricula at

once by offering courses in physics, metal and machine

shop work and drawing without the necessary equipment—

in which case they cannot provide substantial equality now;

or appellees are permitted to wait until the promised new

school is finished at some subsequent date before being

required to equalize the curricula—in which case the decree

ordering equalization at once is meaningless.

The record further shows that Moton is overcrowded.

If courses in physics, metal and machine shop work and

drawing, advanced typing and stenography must be added

at once, this may require special rooms which Moton can

not spare without dropping some of the program presently

in force. Thus, in order to comply with this decree, appel

lees may have to create new curricula inequalities without

curing the old ones.

Confusion is also created by the court’s phraseology.

The court states:

27

“ While the school authorities tender their willing

ness to give any course in the Negro school now obtain

able in the white school, all courses in the latter should

be made more readily available to the students at

Moton. ’ ’

It is difficult to conclude exactly what appellees are required

to do in this regard.

Concerning bus transportation, the court had this to say

in its opinion:

“ In supplying school buses the Negro students have

not been accorded their share of the newer vehicles.

This practice must cease. In the allocation of new

conveyances, as replacements or additional equipment,

there must be no preference in favor of the white

students. ’ ’

It issued a decree ordering immediate equality in means of

transportation. Yet, the court did not indicate what

appellees must now do to satisfy this order. One could

assume that appellees could satisfy the court’s decree in

operating school transportation facilities under present

conditions as long as Negro children got their proportionate

share of any new equipment which might be added in the

future. On the other hand, the decree may require appel

lees to buy new equipment for Negro children at once.

With reference to buildings and facilities, after pointing-

out some of the inequalities in the Negro school, the court

uses the all-inclusive and vague terminology “ in many

other ways the structures and facilities do not meet the

level of the white school.” The expert witness for appel

lants who surveyed the schools testified that Moton was

at a great disadvantage in respect to attractiveness, ar

rangement of physical plant, location, construction and

compactness (Tr. 114-115). Unless there is equality of

buildings in these features, even conceding the possibility

of a separate equality, the new structure cannot be the

equal of the white school. It is not clear whether under

this decree appellees must take these features into account.

A school building program is constantly in progress.

Teaching methods change as educators gain added insight

into the problems of mass education. Public school edu

cation is materially different from what public school edu

cation was ten or twenty years ago or will be several years

hence. With public school education always in flux, no

two schools can retain a constant and fixed relation to each

other.

Certainly this relationship cannot be fixed by court decree.

As Judge Edgerton dissenting in Carr v. Corning, 182 F.

2d 14, 22, 31 (CADC 1950), said:

“ . . . two schools are seldom if ever fully equal to

each other in location, environment, space, age, equip

ment, size of classes, and faculty.’ '

While the meaning and effect of the decree is far from

clear, its enforcement would necessarily involve the court

in the daily operation of the public school system in Prince

Edward County. It is clear that this is a task for which

the judiciary is unsuited, and “ control through the power

of contempt is crude and clumsy and lacking in the flexibility

necessary to make detailed and continuous supervision

effective.” United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334

U. S. 131, 163.15

As a matter of fact this decree seems to require no more

than the statute itself—which has been in force since 1869-

70—under which appellees are required to maintain the

15 See Belton et al. v. Bebhart et al., supra, where in refusing to merely

issue an injunctive decree ordering the state to equalize the Negro school

facilities within the framework of segregation, the court stated that one

of the bases for its refusal was that it could not see how the court could

implement such an injunction against the state.

29

colored schools under the “ same general regulations as to

management, usefulness and efficiency” as the white schools.

Unquestionably, this statutory requirement has not pre

vented discrimination against Negro children. For more

than thirty-four years, officials of Prince Edward County

have been either woefully derelict and disinterested, ac

tively prejudiced against Negroes or are unable to pro

vide equal educational facilities under the state’s separate

school laws. Except to insure the involvement of appel

lants and the class they represent in constant and consid

erable litigation to obtain enforcement and clarification of

the court’s decree, the judgment accomplishes little. It is

indeed difficult to believe that this decree will succeed where

specific statutory requirements have failed.

On the other hand, by declaring the separate school laws

unconstitutional and by restraining appellees from deny

ing admission to the superior schools on the basis of race

and color, the court settles and resolves the basic problem

once and for all. Its only future concern would be upon

a showing that appellees were attempting to avoid the

decree. n tConclusion

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted,

the judgment of the court below should be reviewed by

the United States Supreme Court and reversed.

R obert L. Carter,

Oliver W . H ill,

T hurgood Marshall,

Spottswood W. R obinson, III,

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants.

J ack G-reenberg,

J ames M. Nabrit,

Jack B. W einstein,

Of Counsel.

Dated: May 5, 1952.

30

APPENDIX “A ”

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA,

AT RICHMOND.

Civil Action No. 1333.

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, et al.,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al.

(Heard February 25-29, 1952. Decided March 7, 1952)

Before Dobie, Circuit Judge, and H utcheson and Bryan,

District Judges.

Oliver W. Hill, Esquire, Spottswood W. Robinson, 3rd, Es

quire (Hill, Martin & Robinson) of Richmond, Virginia,

and Robert L. Carter, Esquire, of New York City, for

the plaintiffs;

T. Justin Moore, Esquire, Archibald G. Robertson, Esquire

and T. Justin Moore, Jr., Esquire (Hunton, Williams, An

derson, Gay & Moore) of Richmond, Virginia, for the

defendant school board and superintendent.

Honorable J. Lindsay Almond, Attorney General of Vir

ginia, and Henry T. Wickham, Esquire, Assistant Attor

ney General of Virginia, for the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia.

B ryan, District Judge:

Prince Edward is a county of 15,000 people in the southern

part of Virginia. Slightly more than one-half of its in

habitants are Negroes. They compose 59 percent of the

county school population. At the high school plane the

average pupil attendance is 386 colored, 346 white. For

themselves and their classmates, a large number of these

Negro students, their parents, or guardians now demand

31

that their county school board and school superintendent

refrain from further observance of the mandate of section

140 of the Constitution of Virginia and its statutory coun

terpart.,16 the former reading: “ White and colored children

shall not be taught in the same school. ’ ’ Defendants ’ adher

ence to this command, it is averred, creates a positive dis

crimination against the colored child solely because of his

race or color, constituting both a deprivation of his privi

leges and immunities as a citizen of the United States and a

denial to him of the equal protection of the laws. _ The pro

hibition is denounced as a breach of the Civil Rights Act17

and as inimical to section 1 of the 14th Amendment of the

Federal Constitution.

Defendants pray a declaration of the invalidity, and an

injunction against the enforcement of the separation pro

visions. In the alternative, they ask a decree noting and

correcting certain specified inequalities between the white

and colored schools. That the schools are maintained with

public tax moneys, that the defendants are public officials,

and that they separate the children according to race in obe

dience to the State law are conceded. The Commonwealth

of Virginia intervenes to defend.

Plaintiffs urge upon us that Virginia’s separation of the

Negro youth from his white contemporary stigmatizes the

former as an unwanted, that the impress is alike on the

minds of the colored and the white, the parents as well as

the children, and indeed of the public generally, and that the

stamp is deeper and the more indelible because imposed by

law. Its necessary and natural effect, they say, is to preju

dice the colored child in the sight of his community, to im

plant unjustly in him a sense of inferiority as a human being

to other human beings, and to seed his mind with hopeless

frustration. They argue that in spirit and in truth the col

ored youth is, by the segregation law, barred from asso

ciation with the white child, not the white from the colored,

that actually it is ostracism for the Negro child, and that

the exclusion deprives him of the equal opportunity with

16 Constitution of 1902; See. 22-221, Code of Virginia 1950, q.v. post

p. 6.

it 8 USCA 41.

32

the Caucasian of receiving an education unmarked, an im

munity and privilege protected by the statutes and consti

tution of the United States.

Eminent educators, anthropologists, psychologists and

psychiatrists appeared for the plaintiffs, unanimously ex

pressed dispraise of segregation in schools, and unequivo

cally testified the opinion that such separation distorted the

child’s natural attitude, throttled liis mental development,

especially the adolescent, and immeasurably abridged his

educational opportunities. For the defendants, equally dis

tinguished and qualified educationists and leaders in the

other fields emphatically vouched the view that, given equiv

alent facilities, offerings and instruction, the Negro would

receive in a separate school the same educational opportu

nity as he would obtain in the classroom and on the campus

of a mixed school. Each witness offered cogent and appeal

ing grounds for his conclusion.

On this fact issue the Court cannot say that the plaintiffs’

evidence overbalances the defendants’. But on the same

presentation by the plaintiffs as just recited, Federal

courts18 19 have rejected the proposition, in respect to elemen

tary and junior high schools, that the required separation of

the races is in law offensive to the National statutes and

constitution. They have refused to decree that segregation

be abolished incontinently. We accept these decisions as

apt and able precedent. Indeed we might ground our con

clusion on their opinions alone. But the facts proved in our

case, almost without division and perhaps peculiar here, so

potently demonstrate why nullification of the cited sections

of the statutes and constitution of Virginia is not warranted,

that they should speak our conclusion.

Regulations by the State of the education of persons

within its marches is the exercise of its police power—‘ ‘ the

power to legislate with respect to the safety, morals, health

and general welfare. ’ ,19 The only discipline of this power by

18 Briggs et al. V. Elliott et aL, 98 F.Supp. 529, and Carr v. Coming,

182 F2d 14, citing Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 41 L.Ed., 256; Gong

Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78, 72 L.Ed. 172, and Cumming v. County Board

of Education, 175 U.S. 528, 44 L.Ed. 262.

19 Briggs v. Elliott, supra, 98 F. Supp. 529, 532.

33

the 14th Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of Congress is

the requirement that the regulation be reasonable and uni

form. We will measure the instant facts by that yardwand.

It indisputably appears from the evidence that the sep

aration provision rests neither upon prejudice, nor caprice,

nor upon any other measureless foundation. Rather the

proof is that it declares one of the ways of life in Virginia.

Separation of white and colored “ children” in the public

schools of Virginia has for generations been a part of the

mores of her people. To have separate schools has been

their use and wont.

The school laws chronicle separation as an unbroken

usage in Virginia for more than eighty years. The General

Assembly of Virginia for its session of 1869-70, in providing

for public free schools, stipulated “ that white and colored

persons shall not be taught in the same school, but in sep

arate schools, under the same general regulations as to man

agement, usefulness and efficiency.” 20 It was repeated at

the session 1871-2,21 and carried into the Code of 1873.22

As is well known, all this legislation occurred in the period

of readjustment following the Civil War when the interests

of the Negro in Virginia were scrupulously guarded. The

same statute was re-enacted by the Legislature of 187723

Virginia. In almost the same words separation in the

schools was carried into the Acts of Assembly of 1881-2,25

and similarly embodied in the Code of 1887,26 in the Code of

1919,27 in the same words: “ White and colored persons shall

not be taught in the same school, but shall be taught in sep

arate schools under the same general regulations as to man

agement, usefulness and efficiency.” The importance of

the school separation clause to the people of the State is

20 Acts of 1869-70, cp. 259, p. 402.

21 Acts of 1871-2, c. 370, p. 461.

22 Title 23, c. 78, sec. 58.

23 Acts of General Assembly 1876-7, c. 38, p. 28.

and again in 1878,24 still within the Reconstruction years of

24 Acts of General Assembly 1877-8, c. 14, p. 10.

25 C. 40, pp. 36, 37.

2« Sec. 1492.

27 Sec. 719.

34

signalized by the fact that it is the only racial segregation

direction contained in the Constitution of Virginia.

Maintenance of the separated systems in Virginia has not

been social despotism, the testimony points out, and suggests

that whatever its demerits in theory, in practice it has be

gotten greater opportunities for the Negro. Virginia alone

employs as many Negro teachers in her public schools, ac

cording to undenied testimony, as are employed in all of

the thirty-one non-segregating States. Likewise it was

shown that in 29 of the even hundred counties in Virginia,

the schools and facilities for the colored are equal to the

white schools, in 17 more they are now superior, and upon

completion of work authorized or in progress, another 5

will be superior. Of the twenty-seven cities, 5 have Negro

schools and facilities equal to the white and 8 more have

better Negro schools than white.