Madsen v. Women's Health Center, Inc. Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Madsen v. Women's Health Center, Inc. Brief Amici Curiae, 1994. df6177f0-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cfbc2c51-c332-48cb-a948-0b69369b43b6/madsen-v-womens-health-center-inc-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

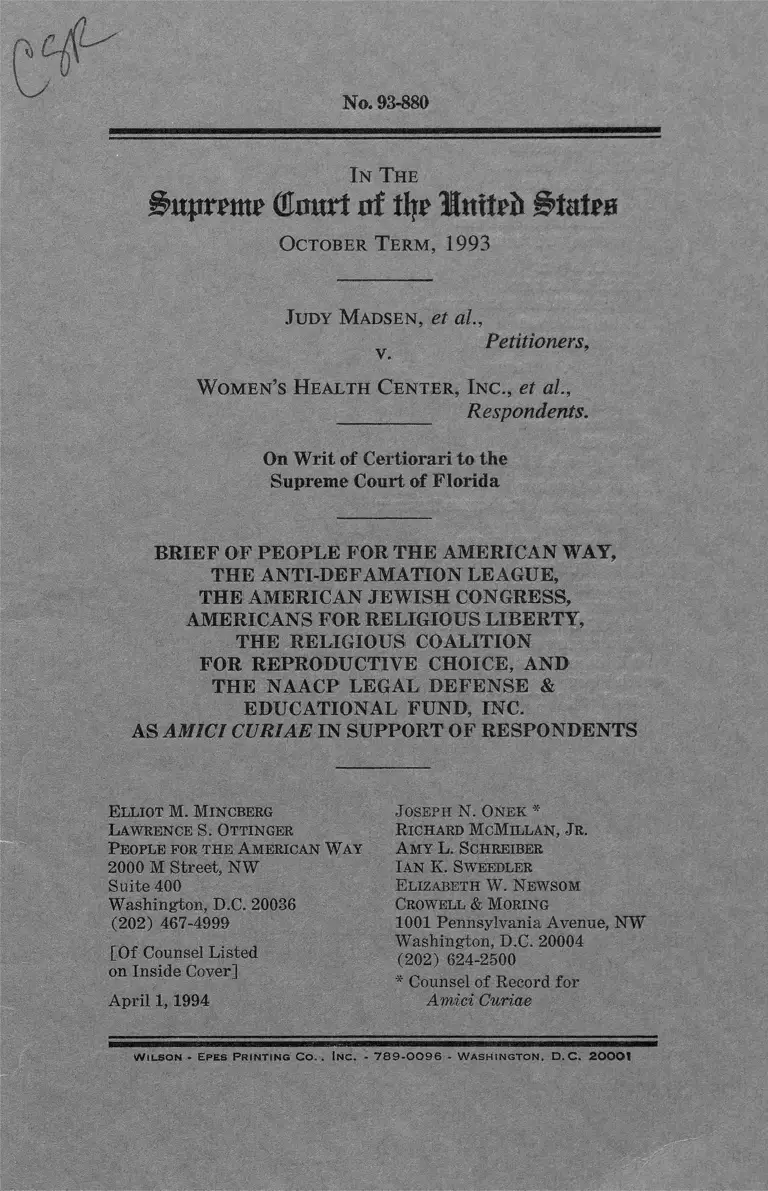

No. 93-880

I n T he

j^uprmr (ta r t of % Inttrft States

October T erm , 1993

Judy Madsen, et al.,

Petitioners,

Wom en’s Health C enter , Inc., et a l ,

_________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Florida

BRIEF OF PEOPLE FOR THE AMERICAN WAY,

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS,

AMERICANS FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY,

THE RELIGIOUS COALITION

FOR REPRODUCTIVE CHOICE, AND

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Elliot M. Mincberg

Lawrence S. Ottinger

People for the American Way

2000 M Street, NW

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 467-4999

[Of Counsel Listed

on Inside Cover]

April 1,1994

J oseph N. Onek *

Richard McMillan, J r.

Amy L. Schreiber

Ian K. Sweedler

Elizabeth W. Newsom

Crowell & Moring

1001 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 624-2500

* Counsel of Record for

Amici Curiae

W il s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

Of Counsel:

Ruth L. Lansner

Steven M. F reeman

J oan S. Peppard

Anti-Defamation League

82S United Nations Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017

Marc D. Stern

Lois C. Waldman

American J ewish Congress

15 E. 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

Richard F. Wolfson

American J ewish Congress

Southeast Region

420 Lincoln Road

Suite 601

Miami Beach, FL 38139

Ronald Lindsay

Americans for Religious L iberty

P.O. Box 6656

Silver Spring, MD 20916

Elaine R. J ones

Theodore M. Shaw

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense &

E ducational F und, I nc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether, in the context of a pattern of illegal conduct

and violations of previous injunctions, a court may con

stitutionally impose specific time, place and manner

restrictions on individuals and organizations and those

acting in concert with them to prohibit blocking access

to a medical facility, harassing the facility’s patients and

staff, engaging in activities that threaten patients’ health,

and harassing and picketing staff members at their homes.

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PR ESEN TED ............................................... .. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................. ........... . iv

IN TER EST OF AMICI CURIAE....... ......................... 1

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.. 5

A R G U M EN T.................... 6

I. TH E INJUNCTION IS CONTENT NEUTRAL.. 6

A. The Injunction Is Not Content Based Simply

Because I t Is Directed A t Speakers Whose

Views Are K now n________________ 6

B. The Restrictions Imposed By The Injunction

Are Content N eu tra l............................................ 7

C. The Injunction’s Application To Persons Act

ing In Concert W ith Named Defendants Does

Not Render I t Content B a se d .......................... 8

II. THE INJUNCTION IS NARROWLY TAI

LORED TO SERVE A SIGNIFICANT GOV

ERNMENTAL INTEREST AND LEAVES

SUFFICIENT ALTERNATIVE AVENUES OF

COMMUNICATION ACCESSIBLE TO THE

SPEAKER.......... ....................... ........- ............... . 12

III. THE INJUNCTION MAY BE EASILY

AMENDED TO AVOID ANY UNANTICI

PATED CONSEQUENCES RESTRICTING

FIRST1 AMENDMENT AND OTHER RIGHTS.. 18

CONCLUSION.............. ........................................................ 20

(iii)

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Alemite Mfg. Corp. v. Staff, 42 F.2d 832 (2d Cir.

1930)..................................... 6,11

Alger v. Peters, 88 So. 2d 903 (Fla. 1956) ______ 6,10

Beth Israel Hosp. v. NLRB, 437 U.S. 483 (1978).... 8,12

Burson v. Freeman, 112 S. Ct. 1846 (1992) ............ 8,17

Carroll v. Presidents and Comm’rs of Princess

Anne, 393 U.S. 175 (1968) ....... 17

Chase Nat’l Bank v. Norwalk, 291 U.S. 431 (1934).. 11

Cheffer v. McGregor, 6 F.3d 705 (11th Cir. 1993).. 7,10

Florida Jai Alai, Inc. v. Southern Catering Servs.,

388 So. 2d 1076 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1980)........... 9

Frisby v. Schultz, 487 U.S. 474 (1988) ............... . 12,17

Hill, Darlington & Grimm v. Duggar, 177 So. 2d

734 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1965)......................... .... 19

Hirsh v. Atlanta, 495 U.S. 927 (1990) ........ 17

Miami v, Miami Dolphins, Ltd., 374 So. 2d 1156

(Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1979)............ ............ ............. 9

Milk Wagon Drivers Union, Local 753 v. Meadow-

moor Dairies, 312 U.S, 287 (1941) ..................16,17,18

Minneapolis Star & Tribune Co. v. Minnesota

Comm’r of Revenue, 460 U.S. 575 (1983) ____ 17

NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886

(1982).... ................................................................ 15

National Soc’y of Professional Eng’rs v. United

States, 435 U.S. 679 (1978) ............................ 16,17,18

NLRB v. Baptist Hosp., 442 U.S. 773 (1979)...... . 8,12

Perry Educ. Ass’n v. Perry Local Educators’ Ass’n,

460 U.S. 37 (1983) .... .................... .......................... 12

U Shop Rite, Inc. v. Richard’s Paint Mfg. Co., 369

So. 2d 1033 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1979) ................ 9

Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781

(1989)......................................................................... 7, 8

STATUTES AND RULES:

17 U.S.C. § 502.... ............................................. ....... 17

Fed. R. Civ. P. 65 (d ) ............. ............ ............. ......... 9,18

Fla. R. Civ. P. 1.610(c)......... ........................... ........... 9,18

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

Melville B. Nimmer, Nimmer on Freedom of

Speech (1984)........................................................... 17

In The

^ttjuTnt? (Emtrt itf tlw I n M ^taJrn

October T erm , 1993

No. 93-880

Judy M adsen, et al.,

Petitioners,

Wom en’s Health C enter , Inc ., et al.,

________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Florida

BRIEF OF PEOPLE FOR THE AMERICAN WAY,

THE ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS,

AMERICANS FOR RELIGIOUS LIBERTY,

THE RELIGIOUS COALITION

FOR REPRODUCTIVE CHOICE, AND

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The undersigned amici are civil rights, civil liberties,

and religious organizations whose members are deeply

concerned about both sets of rights and interests at stake

in this case: the First Amendment right of free expres

sion and the right to reproductive choice protected by the

due process clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amend

ments. Amici believe that, when properly interpreted, the

trial court’s amended injunction imposes reasonable and

2

content-neutral time, place and manner restrictions

against specific parties who intentionally and repeatedly

violated the court’s previous, more narrow injunctions

against illegal behavior. As amici explain below, as a

result of these factors, as well as because the amended

injunction applies only to specific parties and those acting

in concert with them and not to all who oppose abortion,

and because of its adaptability to particular circum

stances, the injunction ensures access to reproductive

medical care consistent with the protection of First

Amendment freedoms, and should be upheld.

People For the American Way (“People For”) is a

nonpartisan, education-oriented citizens’ organization es

tablished to promote and protect civil and constitutional

rights, including First Amendment freedoms, the consti

tutional right to privacy, and women’s rights to reproduc

tive choice. Founded in 1980 by a group of religious,

civic and educational leaders devoted to our nation’s

heritage of tolerance, pluralism and liberty, People For

now has over 300,000 members nationwide. People For

has frequently represented parties and filed amicus curiae

briefs before this Court in litigation seeking to defend

First Amendment rights. People For also has participated

in litigation protecting women’s rights to reproductive

choice. People For is filing this amicus brief because this

case implicates the organization’s dual concerns of en

suring women safe access to reproductive medical care,

including abortion, and fully protecting First Amendment

freedoms. Based on the specific record in this case, the

trial court’s amended injunction accomplishes both of

these purposes by narrowly enjoining conduct of parties

who have repeatedly harassed and violated the rights of

patients and health professionals, while leaving those par

ties ample avenues for free expression.

The Anti-Defamation League (“ADL”) is a human

relations organization established over 80 years ago “to

secure justice and fair treatment to all citizens alike.”

ADL is committed to safeguarding principles of religious

3

and individual liberty, including freedom of speech and

association, the right to privacy, and reproductive free

dom. The right to abortion, and the right to oppose abor

tion, raise sharp conflicting and competing interests,

which must be accommodated. ADL believes the injunc

tion at issue, which establishes content-neutral parameters

for abortion protests, accomplishes that accommodation.

The injunction respects the rights of individuals to voice

their opinions, and, at the same time, protects the ability

of other individuals to exercise their constitutional rights.

In support of these principles, ADL has filed briefs in this

Court in such cases as Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 113 S. Ct.

2194 (1993); Bray v. Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic,

113 S. Ct. 753 (1993); Planned Parenthood of South

eastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 112 S. Ct. 2791 (1992);

Hodgson v. State of Minnesota, 497 U.S. 417 (1990);

and Fraz.ee v. Illinois Dep’t of Employment Sec., 489

U.S. 829 (1989).

The American Jewish Congress (“AJC”) is a national

organization of American Jews founded in 1918 and com

mitted to the preservation of the civil liberties and civil

rights of Jews and of all Americans. AJC has filed many

briefs in this Court supporting First Amendment rights

and free expression. In addition, AJC believes that a

woman’s freedom to choose whether, when, or if to bear

children, and to obtain medical and counselling services

in connection with that freedom, must and should be pro

tected as an essential constitutional liberty.

Americans for Religious Liberty (“ARL”) is a nation

wide nonprofit educational organization dedicated to de

fending religious freedom and freedom of conscience.

ARL has appeared before the Supreme Court in a num

ber of amicus curiae briefs in defense of the right of all

women to freedom of choice in dealing with problem

pregnancies.

The Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice is

comprised of 36 national religious organizations that have

4

official pro-choice policies. The Coalition’s purpose is to

ensure that every woman is free to make decisions about

when to have children according to her own conscience,

without government interference. The Coalition’s primary

role is educating the public to make clear that abortion

can be a moral, ethical, and religiously responsible

decision.

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

(“LDF”) is a non-profit corporation formed to assist

African Americans in securing their constitutional and

civil rights and liberties. For many years LDF has pur

sued litigation to secure the basic civil and economic

rights of low-income African American families and in

dividuals. Litigation to ensure the non-discriminatory de

livery as well as the adequacy of health care and hospital

services available to African American communities has

also been a long-standing LDF concern. See, e.g., Bryan

v. Koch, 627 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980) (challenging the

closing of Sydenham public hospital in Harlem under

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). LDF has also

worked on behalf of African Americans struggling with

the burden of poor health and discriminatory and inade

quate health care services.

LDF is particularly concerned with the growing rates

of poverty among African Americans and with the num

ber of single female-headed African American families

that are living in poverty. Health care for low-income

uninsured women and their families is a matter of great

concern to LDF. Through its Poverty & Justice Program,

LDF is challenging the barriers to economic advancement

to help to improve the economic status and living con

ditions of the many in poverty.1

1 The parties’ letter of consent to the filing of this brief has been

filed with the Court pursuant to Rule 37.3.

5

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case arises in the context of a sustained campaign

to interfere with the operation of a family planning clinic

where abortions are performed and to intimidate and

harass the clinic’s staff and patients. The initial judicial

response was a brief order that simply prohibited certain

organizations and individuals from blocking access to the

clinic and physically abusing persons who worked at or

used the clinic. J.A. 9. When this order failed to provide

adequate protection to the clinic, its staff and its patients,

and when the evidence established a concerted pattern of

violation of the court’s orders and continued harassment

and disruption, the court entered a more detailed in

junction that imposed specific time, place and manner

restrictions on the defendants and those acting in con

cert with them. The Supreme Court of Florida, find

ing that the “demonstrators’ tactics have impaired the

functioning . . . of . . . a licensed medical facility and

have placed in jeopardy the health, safety and rights of

Florida women,” upheld the amended injunction. Opera

tion Rescue v. Women’s Health Ctr., 626 So. 2d 664,

675 (Fla. 1993).

Petitioners, who are anti-abortion activists, challenged

the amended injunction on First Amendment grounds.

They invoke concerns-—prior restraint, content-based re

strictions, overbreadth—-that are central to First Amend

ment jurisprudence. But these concerns are not controll

ing on the facts of this case.

In this case, the court entered its injunction only after

holding a full evidentiary hearing that revealed a history

and pattern of illegal conduct and violations of previous

injunctions. In this case, the court imposed time, place

and manner restrictions that are content neutral and are

narrowly tailored to protect significant governmental in

terests without materially affecting petitioners’ ability to

express and promote their views. And in this case, the

court’s doors remain open to clarify any provisions in the

6

injunction that may unintentionally impinge on First

Amendment rights.

ARGUMENT

I. THE INJUNCTION IS CONTENT NEUTRAL.

Petitioners contend that the injunction issued by the

Florida court is content based, that it imposes restrictions

on demonstrators because of their anti-abortion beliefs

and seeks to stifle the expression of anti-abortion views.

In light of the facts of this case, however, this contention

is without merit.

A. The Injunction Is Not Content Based Simply Be

cause It Is Directed At Speakers Whose Views Are

Known.

An injunction, unlike an ordinance, must be directed

at specific persons.2 Thus, an injunction enforcing even

the most traditional and non-controversial time, place and

manner restrictions will usually be directed against some

one whose political or social views are well known. This

does not mean, however, that the injunction is content

based.

Take the example of a protest group that believes the

United States is reducing military expenditures too

quickly and therefore launches a campaign to “wake up

America” by broadcasting its message by sound truck in

residential neighborhoods at 1:00 in the morning. A

court that was requested to enjoin the 1:00 a.m. sound

truck campaign would certainly know the views of the

speaker and the content of the challenged speech. But

this does not mean that an injunction against the protest

2 “ ‘[A] court of equity is as much so limited as a court of law;

it cannot lawfully enjoin the world at large, no matter how broadly

it words its decree.’ ” Alger v. Peters, 88 So. 2d 903, 907 (Fla.

1956) (quoting Alemite Mfg. Corp. v. Staff, 42 F.2d 832 (2d Cir.

1930) (Hand, J .)) .

7

group barring any sound trucks between 10:00 p.m. and

8:00 a.m. is content based. As long as there is no reason

to believe that an injunction would not be issued against

other speakers in similar circumstances, the injunction

should be regarded as content neutral. “Government reg

ulation of expressive activity is content neutral so long as

it is 4justified without reference to the content of the

regulated speech.’ ” Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491

U.S. 781, 791 (1989).

This same reasoning must be applied to the Florida

courts and the numerous other courts throughout the na

tion now struggling with the issues raised by demonstra

tions at abortion clinics. Obviously, these courts know

the views of the demonstrators, just as in years past they

would have known the views of the demonstrators at

draft boards, university admissions buildings or segregated

lunch counters. The fact that the courts know the views

of each of these speakers is immaterial, so long as that

knowledge does not form the basis for the injunction and

the injunction is otherwise consistent with the First

Amendment. The content neutrality of an injunction de

pends on the nature of the restrictions it imposes, not on

the views of the persons being enjoined.3

B. The Restrictions Imposed By The Injunction Are

Content Neutral.

The injunction in this case is clearly content neutral

on its face; its time, place and manner restrictions do not

refer to any particular content or message. It is also

3 The majority in Cheffer v. McGregor, 6 F.3d 705 (11th Cir.

1993) argued that a restriction on the speech of “the Republican

Party, the state Republican Party, George Bush, Bob Dole, Jack

Kemp and all persons acting in concert or participation with

them. . . .” could not be content neutral. That argument is clearly

incorrect. If those organizations and individuals engaged in the

use of sound trucks at 1:00 a.m., a decision to restrict such conduct

would certainly appear to be content neutral, absent evidence of

discriminatory enforcement.

8

content neutral in objective. As the Court stated in Ward,

491 U.S. at 791, “[t]he government’s purpose is the con

trolling consideration. A regulation that serves purposes

unrelated to the content of expression is deemed neutral

. . . .” The purposes served by the injunction here are

obvious. First, the injunction seeks to assure access to the

clinic to employees, patients and other invitees. Second,

it seeks to protect patients and staff from being physically

abused, harassed and intimidated as they enter the clinic.

Third, the injunction seeks to protect the health of clinic

patients by reducing noise during periods of medical

treatment. Fourth, the injunction seeks to prohibit de

fendants from extending their harassment of clinic em

ployees by invading the privacy of employees’ homes.

None of these objectives is related to the content of the

regulated expression.4

C. The Injunction’s Application To Persons Acting In

Concert With Named Defendants Does Not Render

It Content Based.

Petitioners argue that the injunction in this case was

applied to persons accused of “acting in concert” with the

named defendants in a manner that makes the injunction

4 Only one restriction in the injunction can arguably be considered

content based: the bar against “images observable” to patients dur

ing surgery and recovery hours. In the context of paragraph 4 of

the injunction, the restriction appears aimed at protecting patients

from visual “noise” or clutter, irrespective of the content of the

images. But even if this restriction is deemed content based, the

state has the requisite compelling interest in imposing it. Patients

undergoing surgery or in recovery are certainly at least as in need

of protection from disturbing speech or proselytizing as voters on

the way to the polls. See Burson v. Freeman, 112 S. Ct. 1846, 1851

(1992). See also Beth Israel Hosp. v. NLRB, 437 U.S. 483, 509

(1978) (Blackmun, J., concurring) ; NLRB v. Baptist Hosp., 442

U.S. 773, 783-84 n.12 (1979) (hospitals may shield patients from

upsetting speech). In another era, a court would not have been

barred from shielding servicemen undergoing surgery from the

chants and placards of anti-war protesters.

9

content based. This argument is unsupported by the

record.

It is correct that the injunction applies not only to

specific organizations and individuals but also to “all per

sons acting in concert or participation with them.” The

“in concert” language is taken directly from the Florida

Rule of Civil Procedure 1.63 0(c), which provides that

“every injunction shall be binding on the parties and on

those parties in active concert or participation with them.”

The language of the Florida rule is essentially identical

to that which appears in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure

65(d).

The “in concert” language appears in both the Florida

and federal rules of procedure because without it any

injunction would be meaningless. Named defendants

could circumvent the injunction by arranging for some

other person to carry out the prohibited acts. The courts

of Florida have routinely employed the “in concert” lan

guage without controversy. See, e.g., Florida Jai Alai,

Inc. v. Southern Catering Servs., 388 So. 2d 1076 (Fla.

Dist. Ct. App. 1980); Miami v. Miami Dolphins, Ltd.,

374 So. 2d 1156 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1979); U Shop Rite,

Inc. v. Richard’s Paint Mfg. Co., 369 So. 2d 1033 (Fla.

Dist. Ct. App. 1979).

Petitioners argue that the judge who entered the injunc

tion ruled that persons are “acting in concert” simply

because they advocate anti-abortion positions while pres

ent in the proscribed buffer zones, and that this ruling

renders the injunction content based. Petitioners are un

fairly characterizing the judge’s comments at the hearing.

The judge repeatedly stated that persons who advocated

anti-abortion positions could demonstrate to the prosecutor

or the trial court that they were not “acting in concert.”

See J.A. 66, 68, 70, 74, 77. In essence, the judge simply

made the obvious point that the police were unlikely to

10

consider someone advocating a pro-choice position as “in

concert.” 6

Petitioners also argue that the local police applied the

“in concert” language in a content-based manner by in

discriminately arresting persons who indicated through

speech or images that they held anti-abortion views.

Amici note that any failure of the police to enforce the

injunction in a proper maimer does not render the terms

of the injunction content based. Moreover, the Supreme

Court of Florida only had before it review of “a trial court

order imposing an amended permanent injunction.” Op

eration Rescue v. Women’s Health Ctr., 626 So. 2d at

666. It did not have before it, and did not rule upon,

the activities of the police in applying the injunction.

Thus, those activities are not before this Court.

To the extent any confusion remains, this Court should

make clear that this injunction can not be constitutionally

applied to every person with an anti-abortion viewpoint

solely on the basis of that viewpoint. Amici note that

Florida and federal courts use the same standard to

determine whether non-parties are subject to the terms

of an injunction. “ ‘[T]he only occasion when a person

not a party may be punished, is when he has helped to

bring about, not merely what the decree has forbidden,

because it may have gone too far, but what it has power

to forbid, an act of a party. This means that the re

spondent must either abet the defendant, or must be

legally identified with him.’ ” Alger v. Peters, 88 So. 2d

s The majority in Cheffer v. McGregor, 6 F.3d 705 (11th Cir.

1993), were thus clearly incorrect in concluding that the amended

injunction applies to Ms. Cheffer or any other anti-abortion person

not acting in concert with named defendants. As Judge Paine

explained in his dissenting opinion: “When the Amended Perma

nent Injunction is properly viewed as an injunction, it becomes

clear that the state court lacks the power to reach Cheffer.” Id. at

715. The only relief even arguably justified in Cheffer, assuming

that standing existed, would have been a simple declaration that

the amended injunction did not apply to Ms. Cheffer.

11

903, 907 (Fla. 1956) (quoting Alemite Mfg. Corp. v.

Staff, 42 F.2d 832 (2d Cir. 1930) (Hand, J .)) . Cf.

Chase Nat’l Bank v. Norwalk, 291 U.S. 431, 437 (1934)

(quoting Alemite). Interpreted in this manner, the “in

concert” provisions of the injunction are clearly proper.

There have been no contempt convictions in this case of

persons claiming that they were not “acting in concert”

with the named defendants. There is thus no basis for

contending that the Florida courts will apply the injunc

tion to all anti-abortion demonstrators or be unable prop

erly to determine whether particular individuals were

actually “acting in concert” with defendants for purposes

of enforcing the injunction.

To the extent necessary to protect the rights of individ

uals not subject to the injunction, amici submit this Court

may properly emphasize that two independent determina

tions must be made before the injunction can be enforced

against any individual: whether that person is violating

the substantive time, place and manner provisions of the

injunction, and whether that person is acting in concert

with named defendants.6 Amici are confident that the

Florida courts will properly enforce the injunction and

instruct the police on the meaning of “acting in concert,”

consistent with any guidance the Court may provide in

this case. On the record in this case there is no justifica

tion for invalidating the injunction itself.

8 In practice, there will be many instances in which concerted

activity is clear. According to testimony in the trial court, defend

ant Bruce Cadle acknowledged that he was a leader of a group of

anti-abortion demonstrators and could often be seen directing the

activities of other demonstrators. See J.A. 265-66, 291, 309-10.

12

II. TH E IN JU N CTIO N IS NARROWLY TAILORED TO

SERVE A SIG N IFIC A N T GOVERNMENTAL IN

TER EST AND LEAVES S U FFIC IE N T ALTERNA

TIVE AVENUES OF COMMUNICATION ACCESSI

BLE TO TH E SPEA K ER.

A content-neutral restriction on the time, place or man

ner of expression is permissible if the restriction is nar

rowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest

and leaves sufficient alternative avenues of communica

tion accessible to the speaker. See, e.g., Perry Educ. Ass’n

v. Perry Local Educators’ A ss’n, 460 U.S. 37 (1983). In

this case there can be no question that the restrictions

imposed by the injunction serve significant governmental

interests. First, the injunction protects the health of

women undergoing abortions by reducing noise levels dur

ing the period of surgery and recovery and by ensuring

that women who want abortions can obtain them in a

timely manner. J.A. 55. See NLRB v. Baptist Hosp.,

442 U.S. 773, 781-84 (1979) (upholding regulations

restricting speech based on need to avoid disruption of

patient care and disturbance of patients); see also Beth

Israel Hosp. v. NLRB, 437 U.S. 483, 509 (Blackmun,

J., concurring). Second, it protects the ongoing opera

tions of the clinic and the interests of its clients and em

ployees by assuring access to and from the clinic without

harassment and intimidation. J.A. 55.7 Third, it protects

against defendants’ efforts to extend their campaign of

harassment of clinic employees by invading the privacy

of employees’ homes. J.A. 56; see Frisby v. Schultz, 487

U.S. 474 (1988).

It remains necessary to determine whether the injunc

tion is narrowly tailored to serve these significant govern

mental interests. In making that determination, it is ap

i In Baptist Hosp., this Court noted that certain expression “may

disrupt patient care if it interferes with the health-care activities

of doctors, nurses and staff, even though not conducted in the

presence of patients.” 442 U.S. at 782 n .ll.

13

propriate to review the history of this injunction. The

record demonstrates that the trial court moved carefully

in its efforts to craft an injunction that restricts expressive

activity as little as possible. The court first tried to ad

dress respondents’ concerns through an injunction that

simply enjoined petitioners from harassing clients, block

ing access to the clinic and physically abusing persons

entering or leaving the clinic. J.A. 5-10. This injunction

remained in place for six months, during which time, as

the record shows, the petitioners and other demonstrators

engaged in conduct that interfered with the operations of

the clinic through threats, harassment, intimidation, dis

ruption and physical obstruction. See generally, J.A. 50-

56. Accordingly, after a full evidentiary hearing, the

court concluded that its initial injunction was insufficient

and entered a more specific injunction.

During three days of testimony, the court heard evi

dence that, despite its previous injunction, there had been

serious interference with ingress to the clinic. Judge

McGregor found that the activities of petitioners and

others demonstrating with them had hindered access to

the clinic’s parking lots (J.A. 51, 55) and blocked traffic

on the public street in front of the clinic (J.A. 52, 55).

The amended injunction therefore permits anti-abortion

demonstrators to gather on the south side of Dixie Way,

rather than the north side, to prevent the crov/d from

blocking access to the clinic. J.A. 57-58.

The amended injunction was also directed at conduct

shown to have posed medical risks to the clinic’s patients.

Judge McGregor noted testimony that

the demonstrators [ran] along side of and in front of

patients’ vehicles, pushing pamphlets in car windows

to persons who had not indicated any interest in

such literature. As a result of patients having to run

such a gauntlet, the patients manifested a higher level

of anxiety and hypertension causing those patients

to need a higher level of sedation to undergo the sur

gical procedures, thereby increasing the risk associ

14

ated with such procedures.8 . . . The doctor also tes

tified that he observed some patients turn away from

the crowd in the driveway to return at a later date.

He testified that such delay in undergoing the proce

dures also increased the risk associated therewith.

J.A. 54.

The court concluded that the actions of the petitioners

continued to impede and obstruct both staff and patients

from entering the clinic and that “the noise associated

with the demonstrations impermissibly interferes with the

operation of the clinic and the well-being of its patients.”

J.A. 55. It was on the basis of these concerns for the

well-being of the clinic’s patients that Judge McGregor

enjoined loud noises “during surgical procedures and re

covery periods . . . .” J.A. 59. Finally, the court heard

testimony that clinic employees and sometimes the minor

children of clinic employees were accosted in their homes

by petitioners. Judge McGregor found these actions at

the homes of clinic staff to be impermissible conduct.

J.A. 56.

The injunction must be judged in this context and in

light of the failure of the previous injunction to prevent

illegal conduct. Given this history, the court was entitled

to impose an injunction which might be somewhat

broader in scope than that which would have been appro

priate ab initio. The initial injunction in this case only

prohibited patently illegal conduct—trespassing on clinic

property, blocking access to the clinic and physically

abusing persons using and working at the clinic. J.A. 9.

But after hearing the evidence, the court appropriately

8 Amici note that it was this testimony that resulted in paragraph

5 of the injunction prohibiting demonstrators from approaching

patients within 300 feet of the clinic. Amici believe that this re

striction, aimed at protecting patients from unwelcome intrusion,

intimidation and harassment, is content neutral. But even if it is

not content neutral, the testimony as to the potential harm to pa

tients establishes a compelling interest for the restriction. See

note 4, supra.

15

determined that the only way to protect the clinic, its

staff and its patients was to prohibit conduct that might

be legal under other circumstances. Thus, to prevent

demonstrators from blocking access to the clinic, the court

established a 36-foot buffer zone around the clinic. Simi

larly, it established buffer zones to protect patients seek

ing to enter the clinic from unwelcome intrusion and

physical intimidation and to protect clinic employees

from extension of the pattern of harassment into their

homes.

Petitioners contend that the fact that the injunction en

joins some possibly lawful conduct renders it overbroad

and not narrowly tailored. They cite a footnote in

NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 886

(1982), stating that the injunction issued by the Mis

sissippi courts in that case “must be modified to restrain

only unlawful conduct and the persons responsible for

conduct of that character.” Id. at 924 n.67. Claiborne is

clearly distinguishable. In Claiborne, the NAACP and its

leaders had organized a lawful, economic boycott of cer

tain white-owned businesses, and no evidence connected

them to the “isolated acts of violence” which occurred

during the boycott and caused the damages to plaintiffs.

Id. at 923. Furthermore, there was no evidence that the

NAACP and its leaders had committed or ratified any

illegal acts, or that they had violated a prior injunction

preventing only unlawful conduct. Id. at 930-31. De

spite this evidentiary record, the Mississippi court entered

a large damages award and an injunction which essen

tially sought to stifle completely the NAACP’s lawful

efforts to promote economic, political, and social change

in the local area. Under these facts, this Court reversed

the damages award and the injunction against the

NAACP and its leaders.

In sharp contrast, the court’s amended injunction here

addresses an admittedly illegal blockade of a medical

clinic by organizations and their leaders who, according

to detailed evidence, committed numerous illegal and

16

threatening acts. In this case, which does not involve a

crippling damages award, the court’s original temporary

and permanent injunctions did not enjoin any constitu

tionally protected activity. Only after receiving extensive

evidence that its two prior injunctions had been violated

did the court carefully tailor specific restrictions that pro

hibit some possibly lawful activity.

This Court has held that where illegal conduct has been

demonstrated, a trial court is “empowered to fashion ap

propriate restraints on the [defendants’] future activities

both to avoid a recurrence of the violation and to elimi

nate its consequences,” National Soc’y of Professional

Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 697 (1978). This

is true even though the court may enjoin some otherwise

lawful activity. As the Court has stated:

While the resulting order may curtail the exercise of

liberties that the [enjoined party] might otherwise

enjoy, that is a necessary and, in cases such as this,

unavoidable consequence of the violation. . . . In

fashioning a remedy, the District Court may, of

course, consider the fact that its injunction may _in-

pinge upon rights that would otherwise be constitu

tionally protected, but those protections do not pre

vent it from remedying the . . . violation.

Id. at 697-98; see also Milk Wagon Drivers Union, Local

753 v. Meadowmoor Dairies, 312 U.S. 287 (1941).

The injunction also meets the “narrowly tailored” re

quirement because it clearly leaves sufficient alternative

avenues of communication accessible to petitioners. Peti

tioners are free to demonstrate anywhere except within

36 feet of the clinic and 300 feet of a clinic staffer’s

home. Petitioners may be as noisy as they wish except

during the hours of surgery and recovery. They may pre

sent their views to all persons seeking to enter the clinic

except that they may not physically approach such per

sons within 300 feet of the clinic unless invited to do so.

In short, petitioners have ample means to communicate

their views concerning abortion to patients and potential

17

patients of the clinic, to employees of the clinic and to

the public at large.® In essence, petitioners are restricted

only in the manner in which they can present their views

to people who are “captive” in their homes or “captive”

by virtue of their need for medical treatment. See Frisby

v. Schultz, 487 U.S. at 484-85 (“[A] special benefit of

the privacy all citizens enjoy within their walls, which

the state may legislate to protect, is an ability to avoid

intrusions.”).* 10

® It could be argued, of course, that the 300-foot boundary line

should be 250 feet or 200 feet. This Court responded to such a

contention in Burson v. Freeman, 112 S. Ct. 1846, 1857 (1992), by

stating that “ [w] e do not think that the minor geographical limita

tions prescribed by [a statute forbidding campaign solicitations

near polling places] constitute such a significant infringement.

Thus, we simply do not view the question of whether the 100-foot

boundary line could be somewhat tighter as a question of ‘constitu

tional dimension.’ ” As explained in Section III, infra, moreover,

any problems with a specific boundary line can be remedied while

preserving the overall injunction.

10 Petitioners also invoke the prior restraint doctrine. This Court,

however, has not applied the prior restraint doctrine to cases such

as this, where a remedial injunction is entered only after a full

evidentiary hearing. See National Soe’y of Professional Eng’rs,

435 U.S. at 696-99; Milk Wagon Drivers Union, 312 U.S. at 293-

98. See also discussion in Carroll v. Presidents and Comm’rs of

Princess Anne, 393 U.S. 175, 179-84 (1968). Nor has this Court

applied the prior restraint doctrine in cases involving content-

neutral restrictions except in very limited circumstances. See

Minneapolis Star & Tribune Co. v. Minnesota Comm’r of Revenue,

460 U.S. 575, 586-87 n.9 (1983). To do so broadly would, inter alia,

cast doubt on the constitutionality of the venerable injunction pro

visions of the copyright laws. See 17 U.S.C. § 502 ; see also Melville

B. Nimmer, Nimmer on Freedom of Speech §2.05[C], at 2-57

(1984). See also Hirsh v. Atlanta, 495 U.S. 927, 927 (1990)

(Stevens, J., concurring in denial of stay) (explaining that it is

“entirely proper” to distinguish between “injunctive relief imposing

time, place and manner restrictions upon a class of persons who

have persistently and repeatedly engaged in unlawful conduct” and

an “injunction that constitutes a naked prior restraint against a

proposed march by a group that did not have a similar history of

illegal conduct in the jurisdiction where the march was scheduled”).

18

III. THE INJUNCTION MAY BE EASILY AMENDED

TO AVOID ANY UNANTICIPATED CONSE

QUENCES RESTRICTING FIRST AMENDMENT

AND OTHER RIGHTS,

Because this case involves an injunction rather than an

ordinance or statute, petitioners have an easy remedy if

certain applications of the injunction might violate the

First Amendment in ways not anticipated by the court.

Petitioners can apply to the court to amend or clarify

the injunction. As in National Soc’y of Professional

Eng’rs, petitioners “apparently fear[] that the [trial

court’s] injunction, if broadly read, will block legitimate

paths of expression . . . . But the answer to these fears

is . . . that the burden is upon the proven transgressor

‘to bring any proper claims for relief to the court’s atten

tion.’ ” 435" U.S. at 698. See also Milk Wagon Drivers

Union, 312 U.S. at 298 (“If an appropriate injunction

were put to abnormal uses in its enforcement . . . . the

doors of this Court are always open.”)11

Petitioners contend, for example, that paragraph 6 of

the injunction, which forbids them from “approaching”

within 300 feet of the residence of clinic personnel, would

bar a petitioner from simply living in the same apart

ment complex with a clinic employee or walking down

such an employee’s street. But there is no reason to be

lieve that the Florida court intended to have paragraph

6 read or enforced in such a manner. Amici assume that

the Florida court would, if requested by petitioners,

amend the injunction to permit general “approaches” that 11

11 Issues of vagueness, like overbreadth, take on a very different

meaning in the context of an injunction. An injunction, “arising

out of a particular controversy and adjusted to it, raises totally

different constitutional problems from those that would be pre

sented by an abstract statute with an overhanging and undefined

threat to free utterance.” Milk Wagon Drivers Union, 312 U.S. at

292. Thus, the standard by which an injunction is measured is

whether it is specific in its terms and describes in reasonable de

tail the act or acts sought to be restrained. Fla. R. Civ. P. 1.610(c);

Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(d).

19

are not specifically directed and targeted at clinic per

sonnel for the purposes of harassing them. See, e.g., Hill,

Darlington & Grimm v. Duggar, 111 So. 2d 734 (Fla.

Dist. Ct. App. 1965) (clarifying injunction at request

of defendant).

Indeed, to the extent that potential applications of the

injunction appear to create specific problems, this Court

may wish to make clear its understanding of the reach

of the injunction and the constitutional problems that

would arise if the Florida courts were to interpret the in

junction too broadly or refuse to make appropriate clar

ifications. Of course, the Court can strike down partic

ular provisions of the injunction if it believes they are

unconstitutionally broad and not susceptible to adequate

clarification. However, amici do not believe this action

will be necessary because the record in this case estab

lishes that the amended injunction appropriately protects

against harassment and illegal behavior in a manner con

sistent with First Amendment freedoms.

20

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amici respectfully urge that

the decision of the Supreme Court of Florida be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Elliot M. Mincberg

Lawrence S. Ottinger

People for the American Way

2000 M Street, NW

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 467-4999

Of Counsel:

Ruth L. Lansner

Steven M. F reeman

J oan S. Peppard

Anti-Defamation League

823 United Nations Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10017

Marc D. Stern

Lois C. Waldman

American J ewish Congress

15 E. 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

Richard F. Wolfson

American J ewish Congress

Southeast Region

420 Lincoln Road

Suite 601

Miami Beach, FL 33139

Ronald Lindsay

Americans for Religious Liberty

P.O. Box 6656

Silver Spring, MD 20916

Elaine R. J ones

Theodore M. Shaw

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense &

E ducational F und, I nc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

April 1,1994

J oseph N. Onek *

Richard McMillan, J r.

Amy L. Schreiber

Ian K. Sweedler

Elizabeth W. Newsom

Crowell & Moring

1001 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 624-2500

* Counsel of Record for

Amici Curiae