Spencer v Casavilla Brief of Plaintiff Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 16, 1990

54 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Spencer v Casavilla Brief of Plaintiff Appellants, 1990. c05254ec-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/cfc18382-d39c-407d-9646-e4a97c80e154/spencer-v-casavilla-brief-of-plaintiff-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

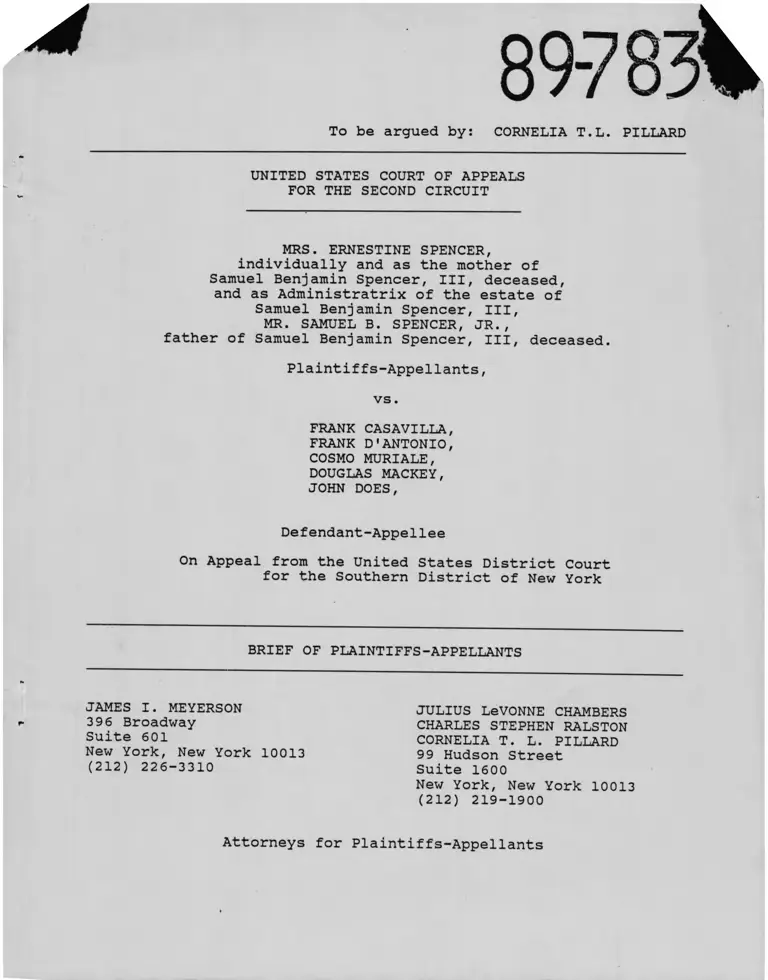

To be argued by:

89-783 i

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

MRS. ERNESTINE SPENCER,

individually and as the mother of

Samuel Benjamin Spencer, III, deceased,

and as Administratrix of the estate of

Samuel Benjamin Spencer, III,

MR. SAMUEL B. SPENCER, JR.,

father of Samuel Benjamin Spencer, III, deceased.

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

FRANK CASAVILLA,

FRANK D'ANTONIO,

COSMO MURIALE,

DOUGLAS MACKEY,

JOHN DOES,

Defendant-Appellee

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JAMES I. MEYERSON 396 Broadway

Suite 601

New York, New York 10013 (212) 226-3310

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

CORNELIA T. L. PILLARD 99 Hudson Street Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ii

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW . .

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........

Nature of the Case . . . .

Course of Proceedings . .

District Court Decision

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS . . . .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..........

ARGUMENT ................

THE DISTRICT COURT APPLIED THE WRONG LEGAL STANDARD IN

DISMISSING THE COMPLAINT FOR LACK OF SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION ..............

II. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ASSERTED A COLORABLE CLAIM THAT BY

KILLING SAMUEL SPENCER BECAUSE HE WAS BLACK, DEFENDANTS

DEPRIVED HIM OF "THE FULL AND EQUAL BENEFIT OF ALL LAWS

... FOR THE SECURITY OF PERSONS" IN VIOLATION OF 4 2 U.S.C. § 1981 ............ 11

III. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ASSERTED A COLORABLE CLAIM THAT

DEFENDANTS' CONSPIRACY WAS CARRIED OUT WITH THE REQUISITE PURPOSE TO VIOLATE 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3) ..............

Plaintiffs' Allegations State a Section 1985(3) Claim Under Griffin v. Breckenridge ...........

The District Court Erred in Holding that the

Purpose of the Conspiracy Must be to Deprive Plaintiff of Federal Rights ..............

Plaintiffs' Allegations State a Section 1985(3)

Claim Even Under The Restrictive Standard Adopted By The District Court . . . .

CONCLUSION . . 33

CASES

Baker v. McDonald's Coro.. 686 F. Supp. 1474 . . 31

Central Presbyterian Church v. Black Liberation Front.

303 F. Supp. 894 (E.D.Mo. 1969)................ 13, 15

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Local Union No. 542.

International Union of Operating Engineers.

347 F. Supp. 268 (E.D.Pa. 1972) . . . . 14

Conley v. Gibson. 355 U.S. 41 (1957)

Demiragh v. DeVos.476 F.2d 403 (2d Cir. 1973) .

Dickerson v. City Bank and Trust. 575 F. Supp. 872 (M.D.La 1983) ............................

Eggleston v. Prince Edward Volunteer Rescue Souad. 569 F.Supp. 1344 (E.D.Va. 1983),

aff'd mem.. 742 F.2d 1448 (4th Cir. 1984)

Fowler v. McCrory. Civil Action JFM 87-1610(D.Md. December 22, 1989) ................

Gannon v. Acton. 303 F. Supp. 1240 (E.D.Mo. 1969), aff'd on other grounds.

450 F.2d 1227 (8th Cir. 1971) . . . .

10

31

32

14

13

13

Great American Federal Savings & Loan Assoc, v . Novotnv 442 U.S. 366 (1979) ! . ~ ; ~ " ]---

Griffin v. Breckenridoe. 403 U.S. 88 (1970)

Hawk v. Perillo, 642 F. Supp. 380 (N.D.I11. 1986)

Hernandez v. Erlenbusch. 368 F. Supp. 752 (D.Or. 1973) ........................

passim

13, 29

13

Jett v. Dallas Ind. School Dist..

105 L. Ed. 2d 598 ( 1 9 8 9 ) .................... 16

Jones v . Alfred H. Maver Co.. 392 U.S. 409 (1968) . 16, 17

King v. New Rochelle Municipal Housing Authority 442 F.2d 646 (2d Cir.),

cert denied. 404 U.S. 863 (1971) . . . . 30

Levering & Garrigues Co. v. Morrin.

287 U.S. 103 ( 1 9 3 3 ) ........................ 10

ii

• 14, 15

Mahone v. Waddle. 564 F.2d 1018 (3rd Cir. 1977)

cert, denied. 438 U.S. 904 (1978) . .

McLellan v. Mississippi Power & Light Co.545 F.2d 919 (5th Cir. 1977) . .

Memorial Hospital v. Maricopa. 415 U.S. 250 (1974)

Memphis v. Greene- 451 U.S. 100 (1981)

26

30

17, 31

Nieto v. United Auto Workers Local 598r 672 F. Supd 987 (E.D.Mich 1987)............................ . 32

Patterson v.— McLean Credit Union. 109 S. Ct. 2363105 L. Ed. 2d 132 (1989) . . . 2.63' 5/ ^ 12

People By Abrams v. n Cornwell Co.,. 695 F.2d 34

(2d Cir. 1982) , modified on other arnnnrig

718 F .2d 22 (2d Cir. 1983) . . . . ' . 20, 25, 28

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)

Stevens v. Tillman, 855 F.2d 394 (7th Cir. 1988)

12

6, 27, 28, 29

Stoner v. Miller, 377 F. Supp. 177 (E.D.N.Y. 1974)

Thompson v. International Assoc, of Machinists,580 F. Supp. 662 (D.D.C. 1 9 8 4 ) ------

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Ren,410 U.S. 431 (1973) . .

31

32

16

'St‘ Barbara’s Greek, Orthodox Chnrrh,851 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1988) . . . 6, 21, 25, 26

United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners

I ,0 r** 1 ̂ 1 1 A T7 T __ « -------------Local 610, AFL-CIQ y. finntt,

463 U.S. 825 (1983) 21,

of America

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs. 383 U.S. 715 (1966)

United States v. Harris. 106 U.S. 629 (1882)

Williams v. Northfield Mount Hermon School 504 F. Supp. 1319 (D.Mass. 1981) [

25

11

26

14

iii

STATUTES

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .

42 U.S.C. § 1982

42 U.S.C. § 1985(3)

42 U.S.C. § 1986

New York Penal Law § 125.25

MISCELLANEOUS

Gormley, Private Conspiracies and the Constitution: a Modern Vision of 42 U.S.C. Section 1985 m .64 Tex. L. Rev. 527 (1985) ................

Comment, Developments in the Law — Section 1981,15 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 29 (1980)

C. Schurz, Report on the States of South Carolina,

Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana

S. Exec. Doc. No. 2, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (December 19, 1865) ........................

Universal Declaration of Human Rights,

reprinted in L. Sohn, Basic Documents of the United Nations (1968) ................

passim

16

passim

1 / 2

31

26

16

17

32

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Did the district court apply the incorrect legal standard in

dismissing the case for lack of subject matter jurisdiction?

Does 42 U.S.C. § 1981, which prohibits racially motivated

interference with plaintiffs' right to "the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and

property," apply to private conduct?

Have plaintiffs who alleged a racially motivated conspiracy

to violate federal rights under the Thirteenth Amendment, First

Amendment and 42 U.S.C. § 1981, as well as rights under New York

State tort law, stated a claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3)?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Nature of the Case

When Samuel Benjamin Spencer, III, a young Black man, rode

his bicycle through the Coney Island section of Brooklyn, New York

in May 1986, six white men chased him in their cars, ran him off

the road, kicked him, beat him with a bat, and stabbed him to

death, yelling "You're going to die now, nigger." The racially

motivated killing of Mr. Spencer by a white mob perpetuates tactics

first used by the Ku Klux Klan a century ago to enforce slavery in

practice after it had been eradicated by law. Groups of white men

used physical violence, including murder, to intimidate Black

former slaves and keep them on the plantations. The Reconstruction

era civil rights laws were enacted to address precisely such

conduct. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1985 (3) , 1986. This lawsuit,

1

brought by Mr. Spencer's parents under those laws, seeks to remedy

the closest modern analogue of the conduct that they originally

addressed.

Plaintiffs claim violations of 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1985(3) and

1986, and of constitutional rights, including the right to travel,

and the right under the Thirteenth Amendment to be free from the

badges and incidents of slavery. The Complaint also alleged torts

under New York State law, including wrongful death, assault,

battery and intentional infliction of emotional distress. see

Complaint (A4). Plaintiffs appeal from the district court's

decision dismissing their Complaint for lack of federal subject

matter jurisdiction. (A81). Plaintiffs seek relief under the

clause of section 1981 which ensures "the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and

property" against deprivation on the basis of race. They contend

that because this clause applies to purely private as well as

governmental violations of Mr. Spencer's rights, the district

court's opinion requiring state action should be reversed.

Plaintiffs also seek relief under section 1985(3), which is

aimed at conspiracies motivated by invidious racial animus that

seek to deprive, "either directly or indirectly, any person or

class of persons of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal

privileges and immunities under the laws. . . .» 42 U.S.C.

§1985(3). The district court acknowledged that section 1985(3)

reaches private action, but held that "in the absence of a

conspiratorial objective to violate a federally-assured right," as

2

opposed to rights assured by state law, plaintiffs cannot recover

under section 1985(3). Plaintiffs contend that the district court

erred both in failing to recognize that they have alleged

deprivations of federal rights, and in interpreting section 1985(3)

as inapplicable to deprivations of equal rights under state law.

The unreported opinion of District Judge Charles S. Haight,

Jr. dismissing plaintiffs' Complaint is reproduced in the Appendix.

(A81).

Course of Proceedings

Plaintiffs filed this case on May 18, 1987. On July 13, 1987

counsel for defendant Frank D'Antonio in his criminal case filed

an Answer generally denying the factual allegations of plaintiff's

Complaint. (A22). No other defendant filed a formal answer to the

Complaint, and none retained counsel for his defense in this

action.

The district judge held a status conference on September 18,

1987 and, in view of the murder prosecution then pending against

the defendants in state court for the conduct alleged in this case,

ordered that the case be placed on the Suspense Calendar. (A29)

On July 5, 1988, after each of the defendants had either pleaded

guilty or been convicted, plaintiffs moved to reactivate this

case.1 (A36). No defendant opposed plaintiffs' motion.

1 Plaintiffs moved on February 28, 1988 for reinstatement of the case to the active court calendar for the limited purpose

of holding a hearing to determine the assets of defendants and, if

appropriate, tô restrain the dissipation of assets pending

resolution of this case. Only defendants Casavilla and D'Antonio

3

The district judge reactivated the case by Memorandum Opinion

and Order dated November 4, 1988. (A42). The judge simultaneously

directed counsel for plaintiffs to serve all defendants with the

Order placing the case on the court's active calendar, and an

additional copy of the Complaint. See Notice of Entry of Opinion

and Order (A45). The Order directed counsel for all defendants

who had not already done so to respond to the Complaint within 45

days after the Order was served on them. It further invited

motions for default judgment against any defendant who did not

respond or seek an extension of time within the specified period.

None of the remaining defendants formally responded to the

. 2Complaint.

At a pretrial conference on April 5, 1989, the court raised

sua sponte the question whether it had federal subject matter

jurisdiction over plaintiffs' claims, and ordered that counsel for

plaintiffs brief the issue. See Order dated April 6, 1989 (A63).

On June 19, 1989, plaintiffs filed their Memorandum of Law in

opposed the motion._ By Order dated April 27, 1988, the court

denied the motion with leave to renew it at a future date. See docket entries dated 2-29-88 to 4-28-88. (A2).

_Defendant Mackey requested and was granted an extension of time within which to file a responsive pleading, but did not do

so. (A51, A53). His aunt, Deanna Daddiego, by letter to the court

did, however, "make a reply of General Denial" on behalf of Mackey

which could be construed as an answer to the Complaint. (A58).

Defendant Muriale wrote to Judge Haight and requested court-

appointed counsel, (A52), and wrote to plaintiffs' counsel to "deny

that there was any racial motivation whatsoever" in Mr. Spencer's

murder. (A62). Muriale's letter, too, might be construed as a pro se answer.

4

Support of Federal Subject Matter Jurisdiction in this Litigation

Under 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 and 42 U.S.C. Section 1985 In

Conjunction With The Thirteenth Amendment To The United States

Constitution. By Memorandum Opinion and Order dated July 27, 1989,

the district court dismissed plaintiffs' federal claims with

prejudice, and dismissed their pendent state-law claims without

prejudice. (A81). On August 16, 1989, plaintiffs timely noticed

this appeal. (A94).

District Court Decision

The district court reviewed the Complaint to test the court's

subject matter jurisdiction, and then dismissed the Complaint under

the standard applicable on a motion to dismiss for failure to state

a claim under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6).

The district court dismissed the section 1981 claim for

failure to allege state action. Although the court recognized that

the Supreme Court recently reaffirmed application of section 1981

against private infringements, slip op. at 3 (A83), citing

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union. 109 S. Ct. 2363, 105 L.Ed.2d 132

(1989), the district court concluded that only the first clause of

section 1981, establishing the right to "make and enforce

contracts," applies to private conduct. Slip op. at 3-6 (A83-86).

The court held that "the complaint at bar, involving private

conduct of a non-contractual nature, does not allege a viable claim

under § 1981." Slip op. at 5-6 (A85-86).

The district court dismissed plaintiffs' section 1985(3) claim

5

on the ground that, "in the absence of a conspiratorial objective

to violate a federally-assured right, the action does not lie under

§ 1985(3)." Slip op. at 11 (A91). The district court acknowledged

that this Court has not required plaintiffs suing under section

1985(3) to allege that the purpose of the conspiracy was to deprive

them of federal rights, slip op. at 6-7 (A86-87), citing Traaais

v. St. Barbara's Greek Orthodox Church. 851 F.2d 584 (2d Cir.

1988), but nonetheless elected to follow the Seventh Circuit's

restrictive interpretation of section 1985(3)'s purpose

requirement. Slip op. at 7-8, 11 (A87-88, 91), citing Stevens v.

Tillman, 855 F.2d 394 (7th Cir. 1988). The court did not discuss

why it apparently found inadequate the Complaint's allegations

showing that defendants sought to interfere with Mr. Spencer's

federal constitutional rights to travel and associate, and his

Thirteenth Amendment right to be free from the "badges and

incidents of slavery." The district court concluded that

plaintiffs' Complaint is inadequate because it "contains no

allegations implicating a federally created or protected right."

Slip op. at 10 (A90).

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Plaintiffs' Complaint seeks compensatory and punitive damages

for the racially motivated killing of their twenty—year old son,

Samuel Benjamin Spencer, III. See Complaint (A4).3 In the early

3 Whether^ the dismissal below was for lack of subject

jurisdiction or for failure to state a claim, the allegations of the Complaint must be taken as true.

6

morning of May 28, 1986, when Mr. Spencer was bicycling to his

sister's house near Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York, six white

men pursued him in four cars, driving up onto the sidewalk and

cutting across his path. Id., 13, 15 (A10). When Mr. Spencer

fell off his bicycle, the men attacked him, kicking him and beating

him with a baseball bat. Id., 16 (A10) . Defendant Frank

Casavilla stabbed Mr. Spencer repeatedly with a knife, yelling

"You're going to die now, nigger." Id. at 15, 16, 17 (A10) ;

See Letter from Assistant District Attorney Daniel A. Saunders to

Hon. Michael R. Juviler (February 22, 1988), at 1 (A33)

[hereinafter "ADA letter"].

Mr. Spencer died at 4:40 a.m. the same day at Coney Island

Hospital. The autopsy revealed head trauma, skull fractures, brain

injury and stab wounds in Mr. Spencer's back. ADA letter at 1

(A3 3) . The Medical Examiner concluded that the beating and

stabbing caused the death, and listed the death as a homicide.

Complaint at 21 (All).

Mr. Spencer was unarmed, and did nothing to provoke the

attack. Id. at 23, 25 (All, 12). The defendants were hostile

toward Mr. Spencer, and opposed his presence in their neighborhood

and near their cars, on the basis of his race. Id. at 17, 23,

25 (A10, 11, 12). They murdered him solely because he was Black.

Id.

7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court erroneously dismissed plaintiffs' claims

for want of subject matter jurisdiction under the legal standard

applicable on a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim.

In order to state a basis for federal jurisdiction, a complaint

need merely state a non-frivolous federal claim, not a viable one.

Acting sua sponte with no motion to dismiss before it, the court

in effect predicted that if defendants had filed a motion to

dismiss the court would rule in their favor, and dismissed the case

on that basis. This error alone requires reversal.

Even if defendants had moved to dismiss plaintiffs' Complaint

for failure to state a claim, dismissal would have been erroneous

on its merits. Plaintiffs have alleged that defendants, a group

of white men conspiring together, murdered Samuel Spencer solely

because he was Black. Such conduct is squarely prohibited by

sections 1981 and 1985(3) of the Reconstruction Civil Rights laws.

The district court erroneously dismissed plaintiffs' section

1981 claim for want of state action. Section 1981 does not require

government participation. The Supreme Court in Patterson v. McLean

Credit Union, 105 L.Ed.2d. 132, recently reaffirmed that private

actors are liable when they interfere with a plaintiff's right

under section 1981 to "make and enforce contracts." There is no

basis upon which to hold that private persons are not also liable

for interfering with the other rights section 1981 protects,

including Mr. Spencer's right under section 1981 to "the security

of persons."

8

The court dismissed plaintiffs' section 1985(3) claim for

failure to allege that the object of defendants' racially-motivated

conspiracy was to violate Mr. Spencer's federal rights, as opposed

to his rights under state law. Neither the text of section 1985(3)

nor its judicial construction is limited to conspiracies to violate

federal rights. The statute addresses all racially motivated

conspiracies to deprive persons of "equal protection of the law or

equal privileges and immunities under the laws." Moreover, because

plaintiffs alleged a conspiracy to deprive Mr. Spencer of equal

"̂î jhts under federal as well as state law, the claim suffices even

under the standard the district court purported to apply.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT APPLIED THE WRONG LEGAL

STANDARD IN DISMISSING THE COMPLAINT FOR LACK OF SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION

The district judge dismissed plaintiffs' Complaint without

specifying the procedural posture in which it did so. The court

stated that "[wjhether the proper procedural ruling is to dismiss

the action for want of federal subject matter jurisdiction or to

find a sufficient invocation of jurisdiction and then dismiss the

federal claims under Rule 12(b)(6), F.R.Civ.P., the result is that

the complaint must be dismissed." Slip op. at 11—12 (A91—92). In

the context of the proceedings in this case, however, the court

could only have dismissed the matter for want of subject matter

jurisdiction. In doing so, the court applied an erroneous standard

to plaintiffs' claims.

9

Defendants did not move to dismiss the Complaint. Thus, the

court was not in a position to review plaintiffs' claims under

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b) (6) . The court itself did not

move to dismiss the case, nor could it have done so. Rather, the

court specifically asked counsel to brief only subject matter

jurisdiction, an issue that the court is empowered to raise at any

time. Plaintiffs accordingly filed a memorandum in support of

subject matter jurisdiction. Once the court had given notice of

its intent to test its jurisdiction and that issue was before it,

the court did not apply the appropriate standard. Instead, it

reviewed the Complaint as if defendants had filed a motion to

dismiss for failure to state a claim.

A federal court has subject matter jurisdiction so long as the

complaint raises a federal claim that is not wholly frivolous.

Only if a claim is "obviously without merit" because "'its

unsoundness so clearly results from previous decisions of . . .

[the Supreme Court] as to foreclose the subject and leave no room

for the inference that the questions sought to be raised can be the

subject of controversy"' should it be dismissed for want of

jurisdiction. Levering & Garriques Co. v. Morrin. 287 U.S. 103,

105-06 (1933) quoting Hannis distilling Co. v. BaltimorPr 216 U.S.

285, 288 (1910). The standard for failure to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted is much higher. See Conley v. Gibson,

355 U.S. 41, 45-46 (1957). Under that standard, the plaintiffs

must show more than room for "controversy" about their claims; they

must explain why any open legal questions should be decided in

10

their favor.

Here, plaintiffs were asked only to address subject matter

jurisdiction. The court's sua sponte dismissal of plaintiffs'

claims on their merits raises serious constitutional problems,

especially where plaintiffs were given no notice that the court

intended to review the Complaint on its merits. If the Complaint

states even a single non-frivolous federal claim, the court has

jurisdiction over the entire case. See United Mine Workers v.

Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966). If defendants had continued to fail

bo respond in this lawsuit, motions for default judgment would have

been appropriate. Thus, unless this Court finds plaintiffs'

federal claims to be wholly frivolous, the case must be remanded.

II. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ASSERTED A COLORABLE CLAIM

THAT BY KILLING SAMUEL SPENCER BECAUSE HE WAS

BLACK, DEFENDANTS DEPRIVED HIM OF "THE FULL

AND EQUAL BENEFIT OF ALL LAWS . . . FOR THE

SECURITY OF PERSONS" IN VIOLATION OF 42 U.S.C § 1981

When defendants chased Mr. Spencer in their cars and attacked

him in the early morning hours, they deprived him of the full and

equal benefit of New York State laws prohibiting assault and

murder. Defendants acted quickly, leaving no opportunity for law

enforcement intervention to save Mr. Spencer. They outnumbered and

overwhelmed Mr. Spencer, preventing him from calling for help. By

the time the defendants were apprehended, the crimes had already

been completed and Mr. Spencer was dead.

The district court's conclusion that section 1981 does not

cover such conduct because it was perpetrated by private persons

11

rather than state actors cannot be sustained even under the Rule

12(b)(6) standard that the district court improperly applied.

Under the appropriate subject-matter jurisdiction standard, it is

indisputable that plaintiffs asserted at least a colorable claim

that defendants' conduct violated section 1981.

Section 1981 applies to racially motivated private conduct

that interferes with "the security of persons."4 In Patterson v.

McLean Credit Union, 105 L.Ed.2d. 132, the Supreme Court reaffirmed

the holding of Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) , that section

1981 prohibits private as well as official deprivations of the

statutory right to "make and enforce contracts." Application of

section 1981 to private conduct, the Court observed, "is entirely

consistent with our society's deep commitment to the eradication

of discrimination based on a person's race or the color of his or

her skin." 105 L.Ed. at 149.

Section 1981 is written as a single sentence, and the

rationales of Patterson and Runvon should not be limited to the

statute's first phrase. The lower courts have accordingly applied

section 1981 to private conduct that deprived plaintiffs of the

Section 1981 of Title 42 of the United States Codeprovides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

shall have the same right to make and enforce contracts,

to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and

equal ̂ benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white

citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains,

penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind and no other.

12

II In"equal benefit of all laws . . . for the security of persons.

Hawk v. Perillo. 642 F. Supp. 386-87, 388-92 (N.D.I11. 1986), for

example, the court sustained the Black plaintiffs' section 1981

claim under the "equal benefit" clause based on allegations that

a group of white men had attacked and severely beaten plaintiffs

while yelling racial insults at them. In Hernandez v. Erlenbusch.

368 F. Supp. 752, 755-56 (D.Or. 1973), the court held a private

group of white men liable under section 1981 for beating up

plaintiffs who had angered the defendants by speaking Spanish in

a local tavern that had an English-only rule.5 See Gannon v.

Acton, 303 F. Supp. 1240, 1244-45 (E.D.Mo. 1969), aff'd on othgr

grounds, 450 F.2d 1227 (8th Cir. 1971) (holding Black civil rights

demonstrators liable under section 1981's guarantee of "equal

benefit of all laws . . . for the security of . . . property" for

disrupting a white congregation's church services in violation of

the plaintiffs' rights to use their church property as they chose);

Central Presbyterian Church v. Black Liberation Front. 303 F.Supp.

894, 901 (E.D.Mo. 1969) (same); cf. Fowler v. McCrory. Civil Action

JFM 87-1610, slip op. at 5-8 (D.Md. December 22, 1989) (slip

opinion attached) (recognizing an employee's right to "give

evidence" on an equal basis with white persons against private

The court did not rely on the fact that the tavern was

publicly licensed, and although discriminatory denial of contracts

"the purchase of beer also provided a ground for section 1981

liability, the court invoked the "equal benefits" clause as well

to find that plaintiffs' "rights to buy, drink and enjoy what the

tavern has to offer on an equal footing with English-speaking customers" had been violated. Id at 755.

13

interference by his employer); Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v.

Local Union No. 542, International Union of Operating Engineers.

347 F. Supp. 268, 289-90 (E.D.Pa. 1972) (enjoining labor union

under the "give evidence" clause from interfering with plaintiff's

pursuit of an employment discrimination suit).

In view of the clear applicability to private conduct of the

section 1981 right to "make and enforce contracts," there is no

basis for failing to so apply the "equal benefit" clause as well.

In drawing a distinction between the first clause and the later

clauses of the statute, the district court adopted reasoning from

Mahone v. Waddle. 564 F.2d 1018, 1029 (3rd Cir. 1977), cert.

denied, 438 U.S. 904 (1978), that the words of the "equal benefit"

clause "suggest a concern with relations between the individual and

the state, not between two individuals," and thus are not protected

from deprivation at private hands. Slip op. at 4-5 (A84-85) . ®

That reasoning was dictum in Mahone, however, and is inconsistent

with the text and legislative history of section 1981.

In Mahone, Black citizens of Pittsburgh sued individual police

°^^^cers and the City for racially motivated beating and

harassment. There were no private defendants in the case, and

The two additional cases upon which the district court relied merely follow this reasoning with no additional support.

Eggleston— v_.— Prince Edward Volunteer Rescue Squad. 569 F.Supp.

1344, 1353 (E.D.Va. 1983), aff* 1 d mem. . 742 F.2d 1448 (4th Cir.

I984)'* Williams_v. Northfield Mount Hermon School. 504 F. Sunn1319, 1332 (D.Mass. 1981).

14

, 7state action was clearly alleged. The court's opinion mentioned

application of section 1981 to private conduct only in passing, to

respond to the City's suggestion that allowing plaintiffs to

recover under section 1981 for the officers' battery would create

"a section 1981 action in federal court whenever a white man

strikes a black in a barroom brawl." 564 F.2d at 1029. The court

referred to the state action requirement as potential limiting

principle on the "equal benefit" clause. Id.

The Mahone court's rationale for opining that the "equal

benefit" clause does not apply to private conduct was that "the

concept of state action is implicit in the equal benefits clause,"

because "the state, not the individual, is the sole source of

laws." 564 F. 2d at 1029. The Supreme Court in Griffin v.

Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1970), rejected just such an argument,

however, in construing section 1985 (3) 's similar language to apply

private actors. At issue there was a prohibition on

depriving persons of "the equal protection of the laws, or the

equal privileges and immunities under the laws." The Court held

that "there is nothing inherent in the phrase that requires the

action working the deprivation to come from the State." 403 U.S.

The Mahone court was careful to specify that "[i]n the instant case, of course, the complaint does allege state action,"

and that accordingly the court did not need to decide more than

whether such state action was covered. 564 F.2d at 1030. Indeed,

among several decisions the court cited with approval was Central

Presbyterian Church, 303 F. Supp. 894, which applied the "equal

benefits" clause to private action; the Mahone court stated "[olur

own examination of section 1981 leads us to believe that its reach

is as wide as these cases would indicate." Id. at 1027.

15

at 345. Similarly, with respect to section 1981's "equal benefit"

clause, "[ajccepting the premise that the state is the sole source

of law does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that only the

state can deprive a citizen of the equal benefit of the laws."

Comment, Developments in the Law — Section 1981, 15 Harv. C.R.-

C.L. L. Rev. 29, 138 (1980). Indeed, just as only the State can

bestow the "equal benefit of the laws," only the State can

"enforce" a contract or fail to do so; Patterson's holding that the

enforcement of contracts is protected against private interference

thus suggests that private obstruction of the "equal benefit of the

laws" is also actionable under the statute.

The Supreme Court's observation in Griffin that the failure

to mention a state action requirement strongly indicates

Congressional intent not to impose one is equally applicable to

section 1981's "equal benefit" clause. See 403 U.S. at 435. in

contrast to section 1981, the Fourteenth Amendment specifies that

it constrains only the "State," and section 1983 of Title 42

explicitly prohibits only conduct "under color of state law."

Indeed, in view of the Supreme Court's decision in Jett v. Dallas

•— School— Dist. , 105 L. Ed. 2d 598, 624 (1989) , that the section

1981 claims of plaintiffs suing state actors are superseded by

their section 1983 claims, affirmation of the district court's view

would render the "equal benefit" clause a nullity.8

g The Supreme Court has also held that 42 U.S.C. § 1982 applies to private conduct. See Jones v. Alfred H. Maver Co.r 392

U.S. 409 (1968). In view of their parallel wording' and

contemporaneous enactment, section 1981 and section 1982 are

similarly construed. See Tillman v, Wheaton~Haven Rec. Assoc.. 410

16

The legislative history of section 1981 further supports the

conclusion that the law applies to private obstruction of "equal

benefit of the laws." As the Supreme Court has emphasized, the

1866 Congress "had before it an imposing body of evidence pointing

to the mistreatment of Negroes by private individuals and

unofficial groups, mistreatment unrelated to any hostile state

legislation." Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.. 392 U.S. at 427. A

substantial part of that evidence was a report drafted by Major

General Carl Schurz on the States of South Carolina, Georgia,

Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, S. Exec. Doc. No. 2, 39th

Cong., 1st Sess. (December 19, 1865). See Memphis v. Greene. 451

U.S. 100, 131 n. 4 (1981) (White, J., concurring). The abuses

Schurz reported were almost exclusively private. Among the forms

of widespread violence by whites against newly freed Black

citizens, Schurz reported that

In many instances Negroes who walked away from

plantations, or were found upon the roads, were shot or

otherwise severely punished, which was calculated to

produce the impression among those remaining with their

masters that an attempt to escape from slavery would result in certain destruction.

S. Exec. Doc. No. 2, at 17. General Schurz1 s report was the

preeminent account of Southern conditions when section 1981 was

enacted, and it was apparently instrumental in convincing Senator

Trumbull, the author and sponsor of the Civil Rights Act of 1866,

that federal legislation was needed. See Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

U.S. 431, 439-440 (1973).

17

1st Sess. 43.

The 18 66 Congressional debates show that the members were

unwilling to tolerate private deprivations of the rights of ex

slaves, whether or not those rights were concerned with the making

and enforcement of contracts. Senator Wilson, in the first speech

on the condition of former slaves, referred to killings as among

the "outrages and cruelties" by private citizens. Cong. Globe,

39th Cong., 1st Sess. 39-40. Other speakers also referred to

killings, and to mobs of white men enforcing a de facto pass

system. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. at 1159-60 (remarks of

Rep. Windom)? id. at 1759 (remarks of Sen. Trumbull); id. at 1833-

35 (remarks of Rep. Lawrence) ; id. at 1838-39 (remarks of Rep.

Clark). As Representative Windom explained it, the bill "provides

safeguards to shield [the freedmen] from wrong and outrage, and to

protect them in enjoyment of that lowest right of human nature, the

right to exist." Id. at 1159. Faced with extensive evidence of

private acts aimed at perpetuating the subjugation of Blacks,

including evidence of racially motivated murder, Congress enacted

section 1981 to redress all such acts and not merely interference

9

Congressional records show that as late as Dec 13, 1865, Senator Trumbull remained uncertain whether the former slaves'

situation demanded federal legislation. His conditional position

that point was that "we may pass a bill, if the action of the

people in the southern States should make it necessary," but he

continued to harbor the "hope that such legislation may be

unnecessary" on the ground that "there may be a feeling among [the

people of the south . . . which shall not only abolish slavery in

name but in fact." Id. The Schurz report was released December

19, 1865, and on January 5, 1866, Senator Trumbull introduced the legislation that became section 1981.

18

with contractual rights.

In view of the wording, structure, and history of section

1981, as well as the numerous precedents supporting the application

of the "equal benefit" clause to private conduct, plaintiffs'

section 1981 claim cannot be deemed "obviously without merit."

Indeed, it would survive a properly filed and briefed motion to

dismiss. Therefore, the decision of the district court must be

reversed.

III. PLAINTIFFS HAVE ASSERTED A COLORABLE CLAIM

THAT DEFENDANTS' CONSPIRACY WAS CARRIED OUT

WITH THE REQUISITE PURPOSE TO VIOLATE 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3)

The only inadequacy the district court identified in

plaintiffs' section 1985(3) claim concerned the allegations of the

conspirators' purpose in killing Mr. Spencer.10 The court held

that unless the conspiracy was alleged to have been aimed at

depriving Mr. Spencer of federal rights independent of section

1985 (3) , in addition to being motivated by racial animus, it was

The text of section 1985(3) relevant to the allegations in this case states:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire . . . for the purpose of depriving, either

directly or indirectly, any person or class of persons

of the equal protection of the laws or the equal

privileges and immunities under the laws; . . . [and] do

or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the object

of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured in his

person or property, or deprived of having or exercising

any right or privilege of a citizen of the United States,

the party so injured or deprived may have an action for

the recovery of damages, occasioned by such injury or

deprivation, against any one or more of the conspirators.

19

not carried out with a purpose actionable under section 1985(3).

Slip op. at 11 (A91). This conclusion is wrong as a matter of law

and fails to credit appropriately the allegations of the Complaint.

Under section 1985(3) as interpreted by the Supreme Court in

Griffin. 403 U.S. at 101-02, and by this Court in People By Abrams

v..11 Cornwell Co.. 695 F.2d 34, 41-42 (2d Cir. 1982), modified on

other,,, grounds, 718 F.2d 22 (2d Cir. 1983) (in banc), plaintiffs

need only allege that defendants acted with racial animus when they

killed Mr. Spencer. Plaintiffs' Complaint contains clear

allegations of racial animus. Complaint at 17, 23, 25 (A10, 11,

12) . Even if this Court were to adopt the additional legal

requirement imposed by the district court that the conspiracy aim

to deprive Mr. Spencer o'f federally-assured rights, plaintiffs'

Complaint also meets that standard. Plaintiffs alleged that

defendants conspired to violate Mr. Spencer's constitutional right

to be free from the badges and incidents of slavery under the

Thirteenth Amendment, his constitutional right to travel, and his

right to the "equal benefit of all laws . . . for the security of

persons" under section 1981. See Complaint (A4).

A. Plaintiffs' Allegations State a Section 1985(3)Claim Under Griffin v. Breckenridae__________

The allegations of plaintiffs' Complaint in this case closely

parallel those sustained by the Supreme Court in Griffin v.

Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88. In Gr iff in, a group of Black persons

riding in a car. Id. at 90. Two white men drove their truck

into the car's path, forced the plaintiffs from the car, prevented

20

their escape by threatening to shoot them, and beat them on their

heads with a club. Id. at 90-91. The Supreme Court reversed prior

precedent holding section 1985(3) inapplicable to purely private

conspiracies, and held that the plaintiffs could recover on the

facts alleged. The only difference between the allegations in that

case and this one is that Mr. Griffin and his companions survived,

whereas Mr. Spencer did not.11

Plaintiffs' Complaint meets the four-part test that the

Supreme Court set forth in Griffin and that the district court

purported to apply here:

To state a cause of action under § 1985(3) a plaintiff

must allege (1) a conspiracy (2) for the purpose of

depriving a person or class of persons of the equal

protection of the laws, or the equal privileges and

immunities under the laws; (3) an overt act in

furtherance of the conspiracy; and (4) an injury to the

plaintiff's person or property, or a deprivation of right or privilege of a citizen of the United States.

Slip op. at 6 (A86) , guotincr Traggis v. St. Barbara's Greek

Orthodox.Church, 851 F.2d at 586-87, citing Griffin. 403 U.S. at

102-03. See United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of

America, Local 610, AFL-CIO v. Scott. 463 U.S. 825, 828-29 (1983)

(affirming Griffin's four-part test). The Complaint alleges a

conspiracy in that "Defendant parties, individually and

collectively, . . . acted together and in concert in the attack,

assault, battery and beating." Complaint at 15 (A10). it

alleges the kind of purpose prohibited by section 1983 in that *

The Supreme Court's holding that plaintiffs' interstate travel rights were implicated does not distinguish that case from this one. See infra, [27-28 and n. 16].

21

defendants "savagely and brutally beat[]" Mr. Spencer "because he

was Black and the defendant parties, as individuals, were hostile

toward him because of his race as a Black individual." Complaint,

at 17 (A10) ; see id. at 23, 25 (All). Allegations that

defendants "kicked, punched, and, ultimately beat[] with a baseball

bat and otherwise stabbed [plaintiff] with a knife" describe overt

acts in furtherance of the conspiracy. Complaint at 16 (A10).

Finally, plaintiffs alleged injury to Mr. Spencer's person as a

result of the conspiracy: he "suffered much pain, physical and

mental, as a consequence of the beating inflicted upon him

including the stabbing and the battering with the baseball bat by

the defendant parties," and then "died on May 28, 1986 after being

taken to Coney Island Hospital from the scene of the brutal and

savage assault. . . ." Complaint, at 24, 18 (All); see id., at

19-22 (All).

The district court erred in holding that the Complaint failed

to meet the second part of the Griff in test, which requires that

the conspiracy be "for the purpose of depriving, either directly

or indirectly, any person or class of persons of the equal

protection of the laws, or equal privileges and immunities under

the laws." 403 U.S. 102-03 ; see slip op. at 6 (A86).12 Under

Gr_i_ffiri/ that element is satisfied by an allegation of racial

animus: "The language requiring intent to deprive of equal

12 The district court did not question the sufficiency of

plaintiffs' allegations under parts (1), (3) and (4) of the Griffin test. -------

22

protection, or equal privileges and immunities, means that there

must be some racial, or perhaps otherwise class-based, invidiously

discriminatory animus behind the conspirators' action." 403 U.S.

at 102 (emphasis added in Griffin).13

Contrary to the suggestion of the district court, slip op. at

7-9 (A87-89), Griffin did not hold, or even assume, that section

1985(3) covers only conspiracies aimed at interfering with federal

rights.14 The district court reached this conclusion because it

believed that otherwise section 1985(3) would federalize all state

torts. Slip op. at 9 (A89) . But the Court in Griffin squarely

held that that problem was resolved by the requirement of class-

based animus, and did not suggest a further requirement that the

purpose of conspiracy be to violate rights under federal as opposed

to state law. Griffin held that

[t]he constitutional shoals that would lie in the path

of interpreting § 1985(3) as a general federal tort law

can be avoided by giving full effect to the congressional

purpose — by requiring,_ as an element of the cause of

action, the kind of invidiously discriminatory motivation stressed by the sponsors of the limiting amendment.

403 U.S. at 102.

The Court relied in part on the remarks of Representative Shellabarger, section 1985(3)'s House sponsor, who described the

purpose requirement as ensuring "that any violation of the right

the animus of which is to strike down the citizen, to the end that

he may not enjoy equality of rights as contrasted with his and

other citizens' rights, shall be within the scope of the remedies of this section." 403 U.S. at 100.

14 The aspect of §

deprivation of rights

403 U.S. at 102, n.10

Court specifically stated that "[t]he motivation

1985(3) focuses not on scienter in relation to

but on invidiously discriminatory animus."

23

So long as the requisite racial animus is present,

conspiracies aimed at depriving a person of the equal protection

of state or federal law alike meet the Griffin standard. The need

referred to by the district court "on the one hand to avoid turning

all state torts into federal offenses and on the other to give some

content to a statute that if read naturally speaks only to state

action and therefore duplicates § 1983," slip op. at 8 (A88), was

fulfilled by Griffin's reading of section 1985(3) to require racial

animus.

Plaintiffs alleged racial animus. Complaint at 17, 23, 25

(A10, 11, 12). Those allegations have already been substantiated

with testimony that Defendant Frank Casavilla shouted "you're going

to die now, nigger," as he stabbed Samuel Spencer to death. See

i/ (A33) . Plaintiffs clearly have alleged an

adequate basis for subject matter jurisdiction over their section

1985(3) claim, and indeed have stated an actionable claim under

that section.

B. The District Court Erred in Holding that the

Purpose of the Conspiracy Must be to Deprive Plaintiff of Federal Rights___________

The district court required that the conspiracy both be

motivated by racial animus and be carried out with the purpose of

depriving plaintiffs of federally protected rights. Slip op. at

11 (A91) . Even if the district court is correct that the

conspiracy must aim to deprive a plaintiff of some right

independent of section 1985(3), see slip op. at 7 (A87), citing

24

Great American Federal Savings & Loan Assoc, v. Novotnv. 442 U.S.

366, 372 (1979), there is no basis upon which to require that the

right be one protected by federal rather than state law.

To the extent that a purpose to deprive a plaintiff of rights

independent of section 1985(3) is required under the statute, the

Supreme Court in Scott suggested that "rights, privileges or

immunities under state law or those protected against private

action by the Federal Constitution or federal statutory law" all

might qualify. 463 U.S. at 834.15 This Court has not read section

1985(3) to require allegations that defendants conspired for the

purpose of violating federal rights. In Tragqis v. St. Barbara's

Greek Orthodox Church. 851 F.2d at 587, the Court acknowledged a

controversy over the extent to which section 1985(3) applies to

private conspiracies "to deprive persons or classes of persons of

the equal protection of, or equal privileges and immunities under,

federal statutory or state law," but did not take a position in

that controversy because the state-law claim at issue in Tracrais

was incompatible on other grounds with the section 1985(3) remedy.

851 F. 2d at 590 (following Novotnv in declining to apply section

1985(3) remedy when it would undermine detailed administrative

procedures in separate law). Tragqis did recognize, however, that

the most recent relevant precedent in this Circuit, People By

In Scott, the Court found it unnecessary to remand the case for a determination whether any such violation was involved

because it affirmed the set-aside of the injunction on the basis

that pro-union animus is not actionable class-based animus under section 1985(3). Id.

25

Abrams v. 11 Cornwell. 695 F.2d at 42, suggested that plaintiffs

injured by defendants acting with a class-based animus to deprive

plaintiffs of state-law rights can sue under section 1985(3). 851

F.2d at 588-89 (noting that 11 Cornwell cited with approval the

holding of Life Insurance Co. of North America v. Reichardt. 591

F.2d 499, 505 (9th Cir. 1979), that state-conferred rights can be

remedied under section 1985(3)). The Fifth Circuit is also in

accord with this view. See McLellan v. Mississippi Power & Light

Co_;_, 545 F. 2d 919, 926-27 (5th Cir. 1977) (en banc) (holding that

§ 1985(3) requires a purpose to commit an independent violation of

federal or state law, with three members dissenting on the ground

that no deprivation of any independent right need be alleged). see

generally Gormley, Private Conspiracies and the Constitution:

A Modern Vision of 42 U.S.C. Section 1985 m . 64 Tex. L. Rev. 527,

587 (1985) ("Section 1985 (3) — unlike section 1983 — does not

require the deprivation of some constitutionally or federally

right . . . . the right at stake will normally be the

equal protection of state laws — trespass laws, contract laws,

property laws, and tort laws").16

In United States v. Harris. 106 U.S. 629 at 643 (1882),

the Supreme Court discussed how "one private person can deprive

another person of the equal protection of the laws" in the meaning

°f. t,he language that appears in both section 1985 (3) and its criminal analogue under review in Harris. The Supreme Court there

interpreted the language to include "the commission of some offense against the laws which protect the rights of persons, as by theft,

burglary, arson, libel,^ assault or murder." Id. Although the

Supreme Court in Harris struck down the criminal statute as

unsupported by any Constitutional authority (an issue resolved for

current purposes by Griffin), plaintiff's claim in this case is

supported by the Supreme Court's view, just sixteen years after

passage of section 1985(3), that the language encompasses a

26

In determining that a purpose to violate federal rights is

required, the district court relied substantially upon Stevens v.

Tillman, 855 F.2d 394. There, the Seventh Circuit rejected a white

school principal's claim that the Black president of a parent-

teachers' association and others had violated her rights under

section 1985(3) by conspiring to commit such acts as trespass

during a sit-in, assault in the form of verbal threats, and slander

in statements to reporters. Id. at 395, 405. The court dismissed

plaintiff's claim because she "does not contend that [defendant]

violated any of her rights under state law . . . for the purpose

or with the effect of inducing her to surrender or refrain from

exercising rights secured by federal law." Id. at 404. The

Seventh Circuit thus demanded an additional federal "hook," id. at

405, beyond the race-based animus required under Griffin.

This Court should not follow Stevens, which misread Griffin

and is inconsistent with the plain language of section 1985(3).

The court in Stevens cited no precedent for its view, and appears

to have considered itself to be developing new law. Its rationale

for developing an added requirement reiterates the concern

articulated and resolved by the Supreme Court in Griffin: to avoid

federalizing all state tort law. Stevens. 855 F.2d at 404. As

noted above, however, the Court in Griffin was satisfied that the

requirement of race—based animus was the "hook" Congress used to

distinguish harms properly remedied only under state law from the

conspiracy to commit murder.

27

efforts to re-subjugate the former slaves for which Congress chose

to provide an additional, federal remedy. Stevens misreads Griffin

to require a section 1985(3) plaintiff to allege "that the offense

deprives him of a right secured by a federal rule designed for the

protection of all." 855 F. 2d at 404 (emphasis added). The Supreme

Court in Griffin stated only that the conspiracy must "aim at a

deprivation of the equal enjoyment of rights secured by the law to

all," with no requirement that the rights be federally protected.

403 U.S. at 102.

Stevens also makes no attempt to reconcile its view with

section 1985(3)'s explicit reference to "an injury to the

plaintiff's person or property" as among the harms actionable under

the law. Indeed, the Stevens opinion fails even to reproduce that

portion of the law in its initial recitation of section 1985(3) 's

requirements. Compare 855 F.2d at 403 with Griffin. 403 U.S. at

103. The Stevens "rule" supports the bizarre result that if

private murder is deemed to be prohibited by state but not federal

law, but see infra Part III.C., (discussing Thirteenth Amendment

rights), a victim of a Klan lynching who did not also have a claim

against the Klan for interference with his rights to speak,

assemble, or vote, for example, would have no section 1985(3)

claim. Surely coverage of the statute popularly known as the "Ku

Klux Klan Act" is not so arbitrarily narrow.

Under precedents in the Supreme Court and this Circuit,

plaintiffs have stated a section 1985(3) claim. The district court

therefore clearly erred in concluding that it had no subject matter

28

jurisdiction. Cf. 11 Cornwell. 695 F.2d at 38 (holding that a

section 1985(3) claim seeking to remedy a violation of state law

was sufficiently substantial to provide a basis for federal

jurisdiction, and proceeding to first decide separate state-law

claim). Even the Seventh Circuit in Stevens expressed uncertainty

whether its decision was right, "either as an interpretation of the

law or as a wise rule." 855 F.2d at 405. Accordingly, plaintiffs'

section 1985(3) claim clearly was not foreclosed.

C. Plaintiffs' Allegations State a Section 1985 (3)

Claim Even Under The Restrictive Standard Adopted By the District Court____________ _

Even if this Court were to agree with the district court that,

"in the absence of a conspiratorial objective to violate a

federally-assured right, [an] action does not lie under section

1985(3)," slip op. at 11 (A91), reversal would still be appropriate

because plaintiffs have alleged that defendants sought to deprive

plaintiff of several rights under federal law.

allegations demonstrate that the conspiracy was

aimed at depriving Mr. Spencer of his constitutional right to

freedom of movement and travel. See Complaint at 13, 14 (A10)

As Griffin itself acknowledged, the right of interstate travel is

protected by the federal constitution against private conduct. 403

U.S. at 105 (citing cases). The facts alleged in the Complaint are

analogous to those in which courts have found grounds for an

inference that plaintiffs were engaged in interstate travel. See

29

Griffin. 403 U.S. at 90-91, 105-0617; Hawk v. Perillo. 642 F.

Supp. at 387 (finding allegations that defendant sought to deter

plaintiffs "'from the free use of highways and entering the subject

neighborhood"' sufficient to support claim of conspiratorial

interference with right of interstate travel in violation of

§ 1985 (3)) .

Even if plaintiffs' allegations fail to support an inference

of obstruction of interstate travel, they clearly implicate a right

of movement and travel within the state. The allegations show that

defendants aimed to keep Mr. Spencer from traveling the route he

took through their neighborhood, down their street, and past

defendants' parked cars by which they were gathered. Although the

Supreme Court has not decided whether the constitutional right to

travel applies to movement within a state, see Memorial Hospital

v,„ Maricopa, 415 U.S. 250, 255-56 (1974) (declining in dicta to

draw a distinction between interstate and intrastate travel), this

Court has specifically held interstate and intrastate travel to be

equally protected. King v. New Rochelle Municipal Housincr

There is no allegation in Griffin that plaintiffs were engaged in interstate travel. The Complaint merely specified that

they "were travelling upon the federal, state and local highways,

in and about DeKalb, Mississippi, performing errands and visiting

friends." 403 U.S. at 90. There is no basis upon which to assume

that the road upon which the plaintiffs in Griffin were traveling

when they were attacked was a federal highway, or that their

errands had taken them from one state to another. It is just as

likely that Mr. Spencer had visited friends in New Jersey on the

day he was killed as that the plaintiffs in Griffin had been doing

in Tennessee. The weakness of the inference of interstate travel in Griffin suggests that the interstate aspect of the travel was not crucial to the Court's analysis.

30

Authority, 442 F.2d 646, 648 (2d Cir.), cert denied. 404 U.S. 863

(1971) (holding that "it would be meaningless to describe the right

to travel between states as a fundamental precept of personal

liberty and not to acknowledge a correlative constitutional right

to travel within a state); Demiraah v. DeVos. 476 F.2d 403, 405

(2d Cir. 1973); Stoner v. Miller. 377 F. Supp. 177, 180 (E.D.N.Y.

1974) .

The Complaint also alleges that defendants conspired to

violate Mr. Spencer's Thirteenth Amendment right to be free from

the "badges and incidents of slavery." See Complaint, 31, 34,

37, 40, 51, 55 (A13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19). Protection of Thirteenth

Amendment rights was a primary purpose of section 1985(3).

Griffin, 403 at 104-05; Memphis v. Greene. 451 U.S. 100, 125 n. 38

(identifying section 1985(3) as among several statutes implementing

the Thirteenth Amendment). As the Court in Griffin explained, the

Thirteenth Amendment prohibits more than "the actual imposition of

slavery or involuntary servitude. By the Thirteenth Amendment, we

committed ourselves as a Nation to the proposition that the former

slaves and their descendants should be forever free." 403 U.S. at

105. Any action "aimed at depriving [Negro citizens] of the basic

rights that the law secures to all free men" violates the

Thirteenth Amendment as implemented by section 1985(3). 403 U.S.

at 105. The right to life is a fundamental aspect of personal

18 See Baker v. McDonald's Corn.. 686 F. Supp. 1474, 1480 and n. 12 (S.D.Fla. 1987) (explaining in dictum that "the

Thirteenth Amendment is implicated when it is alleged that a

P^^vate individual or entity acted in a way to segregate, humiliate

or belittle a person of the Negro race in a way that prevented such

31

freedom in state, federal and international law. See New York

Penal Law § 125.25? Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution; Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Approved by

Resolution 217A (III) of the General Assembly, 10 December 1948,

GAOR, III.l, Resolutions (A/810), at 71-77 reprinted in L. Sohn,

Basic Documents of the United Nations, 168-71 (1968).

Plaintiffs have also alleged that defendants conspired to

deprive them of their rights under 1981. "Several courts have held

that section 1981 may serve as the substantive basis for a cause

of action under section 1985(3)." Nieto v. United Auto Workers

Local 598, 672 F. Supp. 987, 992 (E.D.Mich 1987), citing Chambers

y_._„0maha Girls Club, 629 F. Supp. 925, 940 (D.Neb. 1986); Thompson

¥_•— International Assoc, of Machinists. 580 F. Supp. 662, 667-68

(D.D.C. 1984). See Dickerson v. City Bank and Trust. 575 F. Supp.

872, 876 (M.D.La 1983).

Thus, even if the Court were to adopt the district court's

view that the Complaint must allege a purpose to deprive Mr.

Spencer of a federally-assured right, plaintiffs' allegations

satisfy that requirement. Accordingly, plaintiffs' Complaint

cannot be dismissed, whether for want of subject matter

jurisdiction or for failure to state a claim.

a person from freely exercising a right guaranteed to all

citizens," including "acts which classify a person as a former

S U B " ̂

32

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated in the foregoing Brief of Plaintiffs-

Appellants, the decision of the district court should be reversed,

and the case remanded to the district court for further

proceedings.

Respectfully submitted,

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON 99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

JAMES I. MEYERSON

396 Broadway

Suite 601

New York, New York 10013

(212) 226-3310

Attorneys for Plaintiffs- Appellants

Dated: New York, New York

January 16, 1990

33

/*>rs.

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND

CV

ROBERT G. FOWLER

v.

MCCRORY CORPORATION

*

*

* Civil No. JFM-87-1610

*

*

*****

'nn

OPINION

Plaintiff, Robert G. Fowler, alleges that he was

constructively discharged by defendant, McCrory Corporation, as a

consequence of his refusal to implement a racially discriminatory

hiring policy. He has filed a second amended complaint

containing three counts. The first count asserts a claim under

42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1982), the second count a claim under section

27-20(a) of the Montgomery County Code, Montgomery County, Md.,

Code § 27-20(a) (1984), and the third count a claim under Title

VII, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e-2000(e)(17) (1982). I have previously

certified to the Maryland Court of Appeals the question of

whether Fowler has a cognizable claim under section 27-20(a) of

the Montgomery County Code, and the Court of Appeals presently

has that question sub curia. McCrory has now, in the wake of the

Supreme Court's decision in Patterson v ._McClean—Credit—Union,

109 S. Ct. 2363 (1989), moved to dismiss the claim under § 1981.

I.

The facts as alleged by Fowler, which for the purpose of

McCrory's motion to dismiss must be assumed to be true, are as

follows:

On March 27, 1985 Fowler was performing his job as store

manager at McCrory's Silver Spring store. He had been manager of

the store since 1978. On that day, Ms. Mitchell, a restaurant

zone manager for McCrory, conducted an inspection of the Silver

Spring restaurant and told Fowler that he had hired too many

blacks for the restaurant. She said that Mr. Dovenmuehl, a

regional manager, Mr. Remnick, a company manager, and Mitchell

herself had repeatedly told Fowler "not to hire all blacks for

the restaurant." She went on to say that Mr. Dovenmuehl had told

a Norfolk restaurant manager that he would be fired if he did not

hire the "kind of people" he had been told to hire.

In response, Fowler sent a "witness statement" to Don

Harvey, a McCrory vice president, providing the details of the

incident and protesting the discriminatory hiring instructions.

Three other McCrory employees, who had overheard Ms. Mitchell

make some or all of these comments, submitted witness statements

to Harvey as well.

Fowler never received a written response to his witness

statement. However, he was asked to and did meet with a regional

personnel manager, A1 Winsheimer, in April 1985. Fowler

requested a letter from McCrory stating that the company would

not discriminate on the basis of race. McCrory never sent Fowler

the requested letter and took no other action to repudiate the

discriminatory instructions. Thereafter McCrory employees

allegedly harassed and retaliated against Fowler for protesting

the discriminatory hiring policies. For example, on November 30,

2

1985, McCrory's president, Phil Lux, visited the Silver Spring

store and told Fowler that "there is no place for you in the

future of this store."

On December 13, 1985, Fowler and Ms. Godbold (one of the

employees who had previously submitted a witness statement)

phoned in their complaints about McCrory to the Montgomery County

Human Relations Commission. The same morning, after telephoning

the Commission, Fowler phoned various managers of McCrory

informing them that a complaint had been filed. Within an hour,

William Tallman, another McCrory vice president, called Fowler,

asked him if he and Ms. Godbold had yet to sign the Commission

complaint, and informed him that they had until 2:30 p.m. that

day to reconsider their action. When Fowler later informed

Tallman that he had not decided to withdraw the complaint,

Tallman suspended him without giving any specific reason for the

suspension.

An additional incident occurred on December 17, 1985, when a

district manager of McCrory, in Fowler's presence, referred to a

Thai employee as "like a black person, slow and always trying to

get out of doing work." Fowler reguested that such comments not

be made around him. On January 21, 1985, Fowler informed McCrory

that he was forced to resign because of the company's actions.

He left his job on February 28, 1986, after over 30 years of

employment.

3

II.

42 U.S.C. § 1981 provides in pertinent part as follows:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States shall have the same right in

every State and Territory to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence,

and to the full and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the security of persons

and property as enjoyed by white citizens .

In Patterson v. McClean Credit Union, 109 S. Ct. at 2369,

the Court declined to overrule Runyon v . McCrary, 427 U.S. 160

(1976), which held that § 1981 applies to private conduct. The

Court reaffirmed that claims for racial discrimination in hiring

and promotion are cognizable under § 1981. 109 S. Ct. at 2377.

Recognizing, however, that an expansive reading of § 1981 would

engulf Title VII and undermine the integrity of the dispute-

resolution mechanism established therein, the Court refused to

extend § 1981 to a claim for post-contract, on-the-job racial

harassment. Id. at 2373-75. Although some questions concerning

the scope of § 1981 remain after Patterson, the fundamental

import of the decision is clear: where there is an overlap

between § 1981 and Title VII (or another federal statute

comprehensively addressing matters of racial discrimination),

only those claims which clearly fall with the parameters of §

1981 may be asserted under that section.1

One of the questions which Patterson leaves somewhat

unclear concerns the nature of the promotion claims which are

covered by § 1981. The Court indicated that "[o]nly where the

promotion rises to the level of an opportunity for a new and

4

Due regard for the Patterson decision thus requires that

courts exercise restraint in construing the terms of § 1981.

This does not mean, however, that only a person who has been

refused a job or denied a promotion has a cognizable § 1981

claim. Here, proper analysis requires the conclusion that Fowler

has a claim under § 1981 both as a person whose right to "give

evidence" has been violated and as a person who has been

concretely injured by a discriminatory hiring policy directly

violative of § 1981.

A. Violation of the Right to "Give Evidence"

By its terms § 1981 protects the exercise of four different

rights or sets of rights: (1) the right to "make contracts"; (2)

the right to "enforce contracts"; (3) the related rights "to sue,

be parties, give evidence"; and (4) the right to "the full and

distinct relation between the employee and the employer is such a

claim actionable under § 1981." Patterson. 109 S. Ct. at 2377.

In support of that proposition, the Court cited only Hishon v.

King & Spaulding. 467 U.S. 69 (1984), which involved the dramatic

change in status from associate to partner in a law firm.

Presumably, however, any promotion which would involve a concrete

change in the terms of employment (such as salary or benefits)

would be covered by § 1981.

A second question which Patterson does not resolve is

whether claims for discharges are in and of themselves covered by

§ 1981. Most courts which have considered this issue after

Patterson have held that such claims are not covered. See, e.g ..

Overby v. Chevron USA, Inc., No. 88-5801 (9th Cir. September 1,

1989) (LEXIS, Genfed Library, U.S. App. file); Leong v. Hilton

Hotels Coro.. 51 E.P.D. paragraph 39,257 (D. Haw. July 26, 1989);

but see Padilla v. United Air Lines, 716 F. Supp. 485 (D. Colo.

1989). The former cases seem to be correctly decided since the

termination of employment does not in and of itself does

constitute the violation of a right enumerated in § 1981.

5

equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of

persons and property."

In Patterson the Court appears to have considered only two

of these rights: the right to "make contracts" and the right to

"enforce contracts." 109 S. Ct. at 2372. McCrory argues that

the Court subsumed the third set of rights - "to sue, be parties,

give evidence" - within the concept of the right to "enforce

contracts." McCrory points out that the Patterson Court stated

that the latter right "embraces protection of a legal process,

and of a right of access to legal process, that will address and

resolve contract-law claims within regard to race." Id. at 2373.

That much is certainly true. However, the fact that there is a

degree of concentricity between what is implicitly protected by

the right to "enforce contracts" clause and the express language

of the rights "to sue, be parties, give evidence" provision does

Candor perhaps requires that I acknowledge that I find

enigmatic one aspect of the Court's discussion of the right to

"enforce contracts." The Court concludes the paragraph in which

that right is most fully discussed with a favorable quotation

from a sentence in Justice White's dissenting opinion in Runyon,

stating that all of the rights enumerated in § 1981, other than

the right to "make contracts," refer only to the removal of legal

disabilities. Patterson, 109 S. Ct. 2373 (quoting Runyon. 427

U.S. at 195 n.5 (White, J., dissenting)). If that were true, it

would appear that a person who was blocked by a mob at the

courthouse steps to prevent him from asserting a claim arising

out of anything other than the right to make a contract would not

have a claim under § 1981. That conclusion seems somewhat

dubious. In any event, the language quoted by the Court seems

inconsistent with its own statement that § 1981 "also covers

wholly private efforts to impede access to the Courts or obstruct

non-judicial methods of adjudicating disputes about the force of

binding obligations, as well as discrimination by private

entities, such as labor unions, in enforcing the terms of the

contract." Patterson, 109 S. Ct. at 2373 (emphasis in original).

6

not mean that the two displace one another. There are certain

acts, such as the racially motivated refusal of a labor union to

process grievances under a collective bargaining agreement, which

constitute a violation of a person's right to enforce his

contract but which would not implicate his right to sue, be a

party or give evidence. Id. (citing Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co.,

482 U.S. 656 (1987)). By the same token a person who has been

retaliated against for reporting to a public agency an alleged

racially discriminatory hiring policy has suffered a violation of

his right to "give evidence" even though it is not his own

. 3contract right which he is seeking to enforce.

This is not to say that every employee who alleges that he

was retaliated against for filing or pursuing a claim of racial

discrimination has a cognizable claim under § 1981. If, for

example, he filed his claim with the EEOC, the instruction of the

Court in Patterson that § 1981 and Title VII should be construed

so that they are reasonably consonant with one another suggests

3 Fowler does argue that his right to enforce his own

contract was violated by McCrory's action. He contends that all

applicable laws are incorporated into a contract and that

therefore his contract rights were violated when McCrory violated

federal, state and county anti-discrimination laws in retaliating

against him. This argument proves far too much. If it were

accepted, every act of unlawful discrimination would constitute a

breach of contract and would, in contradiction to the holding in

Patterson, be actionable under § 1981. Thus, whatever value the

principle upon which Fowler relies may have in certain contexts,

see, e.q ., Denice v. Sootswood I. Ouinby, Inc., 248 Md. 428, 237

A.2d 4 (1968) (incorporating the provisions of a county building

code into a construction contract), it constitutes too broad a

statement to enhance the analysis of a § 1981 claim. See

generally 4 S. Williston & W. Jaeger, A Treatise on the Law of

Contracts § 615, at 605—06 (3d ed. 1961).

7

that the remedy provided by Title VII itself for retaliation

would be exclusive. Furthermore, if it could be proved that the

employee deliberately chose to file a complaint with an agency

other than the EEOC in order to create for himself a § 1981 claim

for retaliation, concern for the integrity of the Title VII

scheme might well require rejection of his claim. Here, however,

no such issue is presented. According to his allegations, Fowler

was retaliated against by McCrory for filing a complaint with the

Montgomery Human Relations Commission, and there is no indication

that he chose to file his complaint with that agency to obtain

tactical advantage in this litigation.

B. Third-Party Standing

Fowler also has a viable claim under § 1981 as a person who

suffered concrete injury as a result of McCrory's refusal to

"make contracts" on a non-discriminatory basis.

That Fowler has "standing" in the constitutional sense

cannot be questioned. He has alleged that he has suffered

particularized injury - loss of his employment - which is

directly traceable to McCrory's illegal conduct. See Warth v.

Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 499 (1969) (citations omitted). The more

difficult question is whether he should be deemed to have the