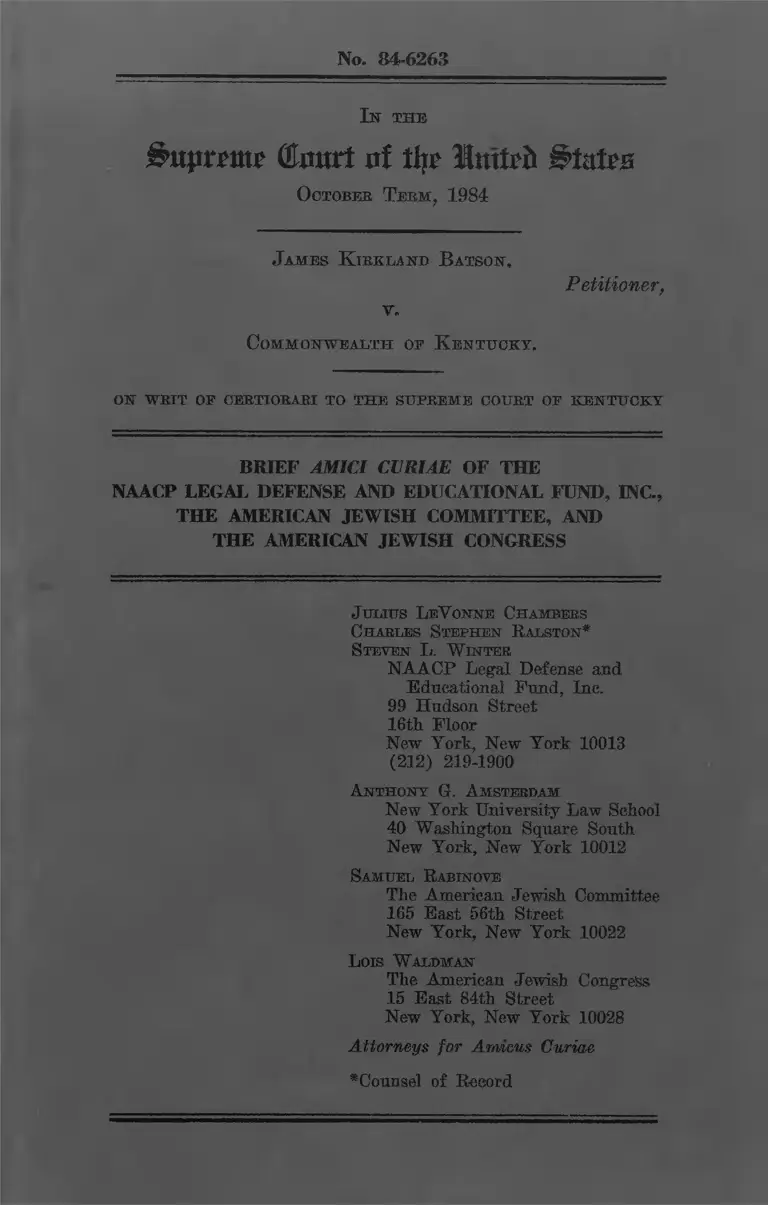

Batson v. Kentucky Brief Amici Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, The American Jewish Committee, and the American Jewish Congress

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Batson v. Kentucky Brief Amici Curiae of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, The American Jewish Committee, and the American Jewish Congress, 1984. b08bf0f9-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d0382e0d-995a-44d6-a168-27939871e196/batson-v-kentucky-brief-amici-curiae-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-the-american-jewish-committee-and-the-american-jewish-congress. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

No, 84-6263

I n t h e

&it|trrmr (tart nf tljr Imtrd Btzxtt&

October Term, 1984

J ames K irkland B atson,

Petitioner,

v.

Commonwealth of K entucky .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF KENTUCKY

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE, AND

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

J ulius L eV onne Chambers

Charles Stephen R alston*

Steven L. W inter

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Ine.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Anthony (t. A msterdam

New York University Law School

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

Samuel R abinove

The American Jewish Committee

165 East 56th Street

New York, New York 10022

Lois W aldman

The American Jewish Congress

15 East 84th Street

New York, New York 10028

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

Question Presented

Whether a prosecutor’s use of

peremptory challenges to exclude Blacks

from jury service because of their race

violates the Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United

States?

1

Index

Page

Interest of the Amici 1

Summary of Argument 5

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTION 9

II. HISTORY OF THE 19

PEREMPTORY CHALLENGE

III. THE EXCLUSION OF BLACKS 24

FROM JURY SERVICE THROUGH

THE USE OF PEREMPTORY

CHALLENGES VIOLATES THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

IV. THE EXCLUSION OF BLACK 37

JURORS VIOLATES THE RIGHT

TO HAVE A JURY REPRESENTA

TIVE OF THE COMMUNITY

V. EFFECTIVE MINIMALLY 47

INTRUSIVE MEANS EXIST TO

REMEDY THE UNCONSTITU

TIONAL MISUSE OF

PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES

Conclusion 60

- ii -

Table of Authorities

Page

Cases:

Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398 (1945) 15

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S.

625 (1972) 3, 10, 35, 44

Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404

(1972) 42

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977) 30, 35

Ballard v. United Stated, 329 U.S.

187 (1946) 38

Ballew v. Georgia, 435 U.S. 223

(1978) 44

Bob Jones University v. United

States, __ U.S. __, 76 L.Ed.2d

157 (1983) 12

Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 P .2d 1253

(5th Cir. 1971) 10

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 (1953) 38

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S.

320 (1970) 3, 10

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950)

- iii -

15

30

Columbus Bd. of Ed. v. Penick, 443

U.S. 449 (1979)

Commonwealth v. Joyce, 18 Mass. App.

417, 467 N.E.2d 214 (Mass. App.

Ct. 1984), further appellate

review denied, 470 N.E.2d

798 (19141 55

Commonwealth v. Kelley, 10 Mass. App.

847, 406 N.E.2d 1327 (Mass. App.

Ct. 1980) 46

Commonwealth v. Perry, 15 Mass. App.

932, 444 N.E.2d 1298 (Mass. App.

Ct. 1983), further appellate

review denied, 388 Mass. 1104,

488 N.E.2d 766 (1983) 54

Commonwealth v. Reid, 384 Mass. 247,

424 N.E.2d 495 (Mass. 1981) 55

Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461,

387 N.E.2d 499, cert, denied, 444

U.S. 1 881 (1979) 13, 37, 53, 55, 58

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145

(1968) 37

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) 10

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947) 42

xv

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1942) 15

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S.

81 (1943) 26

Hobby v. United States, __ U.S. __,

82 L.Ed.2d 260 (1984) 12

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S.

214 (1944) 26

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) 26

McCray v. Abrams, 750 F.2d 1113 (2nd

Cir. 1984), reh. en banc

denied , 756 F.2d 177 (1985) 37

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) 30, 32

Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117

(M.D. Ala. 1966) 3

Palmore v. Sidoti, __ U.S. __, 80

L .Ed.2d 421 (1984) 26

Patton v. Yount, __ U..S. __, 81

L.Ed.2d 847 (1984) 49, 56

People v. Boone, 107 Misc. 2d 301,

433 N.Y.S.2d 955 (Sup. Ct. 1980) 13

People v. Cobb, 97 111.2d 465, 455

v

N.E.2d 31 (1983) 58

People v. Hall, 672 P.2d 854,

859, 197 Cal. Rptr. 71 (1983) 54, 57

People v. Johnson, 22 Cal. 3rd 296,

583 P.2d 774, 148 Cal. Rptr.

914 (1978) 26

People v. Kagan, 420 N.Y.S. 2d 987

(N.Y'. Sup. Ct . App. Div. 1979) 13

People v. McCray, 57 N.Y.2d! 542,

457 N .Y.S.2d 441 , 443 N.E .2d

915 (1982) 13

People v. Payne, 106 111. App.

3d 1034, 62 111. Dec. 744 P

436 N.E.2d 1046 (111. Ct. App.

1982 ), rev1d , 9 111.2d 135,

457 N.E.2d 1202 (1983) 13, 22

People v. Thompson , 79 A.D. 2d 87,

435 N.Y.S.2d 739 (N. Y. Sup.

Ct. App. Div. 1981 ) 13

People v. Walker, 157 Cal. App .3d

1060 , 205 Cal . Rptr. 278

(Ct. App. 1984) 54

People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 258 , 148

Cal. Rptr. 890, 583 P. 2d 748

(1978) 13, 37 , 53, 54, 55, 56, 58

vi

59

People v. Williams, 628 P.2d 869,

174 Cal. Rptr. 317 (Cal. 1981)

(en banc)

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972) 45

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) 30

Roman v. Abrams, No. 85 Civ. 0763-CLB

(S.D.N.Y. May 15, 1985) 57

Rosales-Lopez v. United States

U.S. 182 (1982)

, 451

49

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545

(1979) 12, 60

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) 38

State v. Brown, 371 So.2d 751

(La. 1979) 14, 28

State v. Crespin, 94 N.M.2d

486, 612 P.2d 716 (1980) 13, 37, 53

State v. Gilmore, No. A-870-82

(N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div

March 8, 1985)

T4

• f

53

State v. Neil, 457 So.2d 482

(Fla. 1984) 13, 37, 53

State v. Washington, 375 So.2d

1162 (La. 1979) 15, 25, 28

- vii -

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880) 5 , 9 , 10

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965) passim

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S.

522 (1975) 38, 39, 40, 41, 43

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co.,

328 U.S. 217 (1946) 26

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

(1970) 3, 10

United States v. Childress, 715

F . 2d 1313 (8th Cir, 1983) 13, 28

United States v. Clark, 737 F.2d

679 (7th Cir. 1984) 13

United States v. Jackson, 696 F .2d

578 (8th Cir. 1982) 14

United States v. Leslie, 759 F.2d 31

366 (5th Cir. 1985), rehearing

en banc granted

United States v. McDaniels, 13, 31

379 F. Supp. 1243 (E.D. La. 1974)

United States v. Marchant, 25 U.S.

480 (1827)

- viii -

23

13

United States v. Newman, 549 F.2d

240 {2nd Cir. 1977)

United States v. Pearson, 448 F.2d

1207 (5th Cir. 1971) 28

United States v. Schackleford,

59 U.S. 588 (1856) 23

United States v. Whitfield,

715 F .2d 145 (4th Cir. 1983) 13

United States Postal Service Bd.

of Governors v. Aikens, 460

U.S. 711 (1983) 30, 34

Virqinia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313

(1880) 10

Wainwright v. Witt, __ U.S. , 83

L.Ed.2d 841 (1985) 49

Wheathersby v. Morris, 708 F.2d

1493 (9th Cir. 1983) 13

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

(1967) 36

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78

(1970) 39

Williams v. Illinois, __ U.S. , 104

S.Ct. 2634 (1984) 14

IX

13

Willis v. Zant, 720 F.2d 1212

(11th Cir. 1983)

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886) 26

Statutes:

Act of March 3, 1865, ch. 86,

§ 2, 13 Stat. 500 23

Colo. Rev. St. §§ 13-71-107, et seq. 41

Federal Jury Selection and Service

Act, Pub. L. 90-274, 82

Stat. 53 11, 41

Idaho Code §§ 2-201 et seq. 41

Hawaii Rev. Stat. §§ 612-1 et seq. 41

Indiana Code §§ 33-4-5.5-1 et seq. 41

Maine Rev. St. §§ 1211 et seq. 41

Md. Ann. Code § 8-1-13 41

Minn. Stat. Ann. §§ 593-31 et seq. 41

Miss. Code 1972, §«S 13-5-2 et seq. 41

No. Dakota Code 17-09.1-01 et seq. 41

x

1 Stat. 119 (1790) 23

The Ordinance of Inquests, 33 Edw.

c.2 (1305)

1. 21

28 U.S.C. § 1861 11, 41

Uniform Jury Selection and

Service Act 11, 41

Other Authorities;

4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries 21

Brown, McGuire, and Winters,

The Peremptory Challenge

as a Manipulative Device

m Criminal Trials;

Traditional Use or Abuse?

14 New Eng. L. Rev. 192 (1978)

16, 20, 22

Comment, A Case Study of the

Peremptory Challenge; A

Subtle Strike at Equal

Protection and Due Process,

18 St. Louis L.J. 662 (1974) 14

Comment, Swain v. Alabama; A 20, 22

Constitutional- Blueprint for

the Perpetuation of the

All-White Jury, 52 Va. L. Rev.

1157 (1966) ‘ 20, 22

xi

Jackson, Mississippi, Clarion

Ledger, July 25, 1983 16

New Orleans Times-Picayune,

April 7, 1985 ^6

Sullivan, Deterring the

Discriminatory Use of

Peremptory Challenges, 21 Am.

C n m . L. Rev. 477 (1984) 27, 45

xii

No. 84-6263,

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1984

JAMES KIRKLAND BATSON,

Petitioner,

v .

COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of Kentucky

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE

AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE, AND

THE AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

Interest of the Amici*

The NAACP Legal

tional Fund, Inc.,

Defense and Educa-

is a non-profit

‘Letters from the parties consenting to

the filing of this Brief have been lodged

with the Clerk of the Court.

2

corporation, incorporated under the laws

of the State of New York in 1939. It was

formed to assist Blacks to secure their

constitutional rights by the prosecution

of lawsuits. Its charter declares that

its purposes include rendering legal aid

without cost to Blacks suffering injustice

by reason of race who are unable, on

account of poverty, to employ legal

counsel on their own behalf. For many

years its attorneys have represented

parties and have participated as amicus

curiae in this Court and in the lower

federal courts in cases involving many

facets of the law.

The Fund has a long-standing concern

with the issue of the exclusion of Blacks

from service on juries. Thus, it has

3

raised jury discrimination claims in

1

appeals from criminal convictions,

pioneered in the affirmative use of civil

2

actions to end discriminatory practices,

and, indeed, represented the petitioner in

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), the

case which first raised the issue of the

use of peremptory challenges to exclude

Blacks from jury venires.

The American Jewish Committee is a

national organization of approximately

50,000 members which was founded in 1906

for the purpose of protecting the civil

and religious- rights of Jews. It has

always been the conviction of this

organization that the security and the

constitutional rights of American Jews can

E.g., Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972).

2 Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970);

Turner v. FoucfTe73%lJ7sr346 (1970); Mitchell v.

Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966).

4

best be protected by helping to preserve

the security and the constitutional rights

of all Americans, irrespective of race,

religion, sex or national origin. The

American Jewish Committee believes that

the exclusion of Blacks from juries

through the use of peremptory challenges

is a grievous deprivation based on race

which violates the Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution.

The American Jewish Congress is a

national organization of American Jews

founded in 1918 and concerned with the

preservation of the security and constitu

tional rights of all Americans. Since its

creation it has vigorously opposed racial

and religious discrimination in all areas

of American life, including the adminis

tration of justice. The American Jewish

5

Congress believes that the use of peremp

tory challenges by prosecutors to exclude

persons from juries solely on the basis of

their race or religion is in violation of

the United States Constitution.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The misuse of peremptory challenges

to exclude Blacks from juries is a

pervasive and pernicious practice. Its

use has supplemented earlier and more

obvious devices for preventing minorities

from participating in this most fundamen-

tal of democratic institutions. The

practice violates both the Sixth and

Pourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

and must be ended to make the promise of

Strauder v. West Virginia at last a

reality.

6

II.

Historically, the prosecution did not

have the right to challenge jurors

peremptorily. Under the common law,

peremptory challenges were given to the

defense for the purpose of enforcing the

defendant's underlying right to a fair

and impartial jury of his peers. The

right was extended to the prosecution by

statute only in the mid-nineteenth

century. Nothing in the history of the

exercise of peremptory challenges by the

prosecution suggests any reason for

permitting them to be exercised in a way

that is inconsistent with the Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendments.

III.

The intentional exclusion of a black

potential juror from actual service on a

7

jury violates the Fourteenth Amendment's

guarantee of equal protection. Swain v.

Alabama has been consistently misinter

preted by the lower courts as permitting a

successful objection to the racially

discriminatory exercise of peremptory

challenges in only an unduly limited and

virtually unprovable set of circumstances.

Trial courts should be no less free to

infer intentional discrimination by

prosecutors in a variety of factual

contexts than they are in a wide range of

other cases involving proof of intentional

discrimination.

IV.

For a prosecutor to strike black

jurors from a venire so as to render it

unrepresentative of the community violates

the Sixth Amendment. Although there is no

8

right to a jury that mirrors the communi

ty, the Constitution prohibits the use of

devices which affirmatively defeat a fair

opportunity to be tried by a jury that

reflects a fair cross-section of that

community.

V.

There are a variety of remedies to

correct the unconstitutional use of

peremptory challenges. Although any

method that is selected must realistically

promise effectively to guard against

discrimination, the states should be given

some leeway to experiment with solutions

that are consistent with their particular

jury selection procedures.

9

ARGUMENT

I.

INTRODUCTION

One hundred and five years ago this

Court held that "the very fact" that black

people were prevented from serving on

juries:

. . . because of their color,

though they are citizens and may

be in other respects fully

qualified, is practically a

brand upon them, affixed by the

law; an assertion of their

inferiority, and a stimulant to

that race prejudice which is an

impediment to securing to

individuals of the race that

equal justice which the law aims

to secure to all others.

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303,

3 0 8 ( 1 880). More than a century later,

the promise of Strauder — that all dis

criminatory acts directed towards black

10

citizens in the administration of justice

will be ended — ■ remains unfulfilled.

Until the 1970's, the primary device

for excluding Blacks from jury service was

simply to keep them off of the jury rolls.

Since Blacks never appeared on venires to

begin with, the use of the peremptory

challenge to get rid of them was rarely

required. When 100 years of decisions of

this Court reversing convictions for jury

3

discrimination, injunctions issued by

4

federal district courts, and the reform

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880);

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313 (1880); Ex parte

Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880); see cases cited m

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. at 628-29, 632

(1972).

E.g., Carter v. Jury Commission, supra; Turner v.

Ftoudhe, supra; Broadway v. Culpepper, 439 F.2d 1253

(5th Cir. 1971).

4

5

of federal and state jury selection laws

made total exclusion impractical, the use

of peremptory challenges to exclude those

Blacks who were placed on venires became

the method of choice to achieve the same

historic goal of preventing Black citizens

from participating in the criminal justice

system. Although the means used to exclude

Blacks has changed, the same pernicious

consequence continues: black citizens do

not have their rightful voice in an

institution that is at the heart of a free

and democratic society.

The exclusion of Blacks from juries

not only stigmatizes them and deprives

them of their right meaningfully to

participate in the criminal justice

system. It "destroys the appearance of

E.g., The Federal Jury Selection and Service Act, 28

U.S.C. §§ 1861 et seq.; Uniform Jury Selection and

Service Act, National Conference of Commissioners on

Uniform State Laws, 1971.

12

justice and thereby casts doubt on the

inteqrity of the judicial process . . .,

impair [ingj the confidence of the public

in the administration of justice." Rose

v. Mitc h e l l , 443 U.S. 545, 555-56 ( 1979);

accord Hobby v. United States, ___ U.S.

___ , 82 L . E d .2d 260, 277 ( 1984) (Stevens,

J., dissenting). Nothing could be more

destructive to public confidence in the

legitimacy of criminal justice than the

specter of a prosecutor deliberately

manipulating the process to exclude

identifiable segments of the community on

the basis of race, in contravention of

"deeply and widely accepted views of

elementary justice . . . Bob Jones

University v. United States, ___ U.S. ___ ,

76 L.Ed.2d 157, 174 ( 1983).

The proliferation of cases raising

13

the issue of this misuse of peremptory

challenges demonstrates that the practice

is nationwide, arising in states from

California to New York and Massachusetts

6

to Florida. Thus, the Illinois Supreme

Court has reviewed "at least 33 cases in

which criminal defendants have alleged

prosecutorial misuse of peremptory

See, e.g., People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d 258, 148

Cal. Rptr. 890, 583 P.2d 748 (1978)? State v. Neil,

457 So.2d 482 (Fla. 1984},* People va Payne, 106 111.

App. 3d 1034, 62 111. Dec. 744, 436 N.E.2d 1046 (111.

Ct. 4pp. 1982), rev'd, 9 111. 2d 135, 457 N.E.2d 1202

(1983); Cosrrconwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461, 387

N.E.2d 499, cert, denied, 444 U.S. 1 881 (1979);

State v.Crespin, 94 N.M. 2d 486, 612 P.2d 716 (1980);

People v. Kagan, 420 N.Y.S.2d 987 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. App.

biv. 1979 )~; People v. Thompson, 79 A.D.2d 87, 435

N.Y.S.2d 739 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. App. Div. 1981); People

v. Boone, 107 Misc. 2d 301, 433 N.Y.S.2d 955 (Sup. Ct.

'l980T;~Peq3].e v» McCray, 57 N.Y.2d 542, 457 N.Y.S.2d

441, 443 N.E.2d 915 (1982); United States v. Newman,

549 P.2d 240 (2nd Cir. 1977); United States v.

McDaniels, 379 F. Supp. 1243 (E.D. EaT~T974)7lMlted

States v. Childress, 715 F.2d 1313 (8th Cir. 1983);

T5ut^~^tates~vritfiitfield, 715 F.2d 145 (4th Cir.

?9§?y71H xted^EaEii~v7~C lark, 737 F.2d 679 (7th Cir.

1984); Wheathersty v.Morris, 708 F.2d 1493 (9th Cir.

1983)f"wIITIIv7 Zant, 720 F.2d 1212 (11th Cir.

1983).

14

7

challenges to exclude Negro jurors." The

Eighth Circuit has noted "the frequency

with which we have been called upon to

examine the prosecutor’s practices in this

regard in the Western District of Mis

souri." United States v. Jackson, 696 F .2d

8

578, 592 (8th Cir. 1982). And the

Louisiana Supreme Court reviewed 9 cases

in 7 years from the same parish, 5 of

which involved the same prosecutor. State

v. Brown, 371 So.2d 751 .(La. 1979).

In addition to the many reported

decisions, our experience and that of our

cooperating attorneys has convinced us

that the practice is common and flagrant.

See Williams v. Illinois, 104 S. Ct. 2364, 2365

(1984) (denial of cert.) (Marshall, J., dissenting).

See also Comment, A Case Study of the Peremptory

Challenge: A Subtle Strike at Equal Protection and

Due Process, 18 St. Louis L.J. 662, 676-77 (1974),

citing to studies finding that local prosecutors

struck 83% and 67% of black jurors respectively in

one year.

15

Indeed, prosecutors have publicly admitted

that they seek to keep Blacks from sitting

on criminal trials as a matter of course

because they are afraid that Blacks will

be too sympathetic to a defendant. Thus,

an instruction book used by the prosecu

tor's office in Dallas County, Texas, the

9 10

site of Hill v. Texas, Akins v . Texas,

11

and Cassell v. Texas, advised

prosecutors that they did not want a

"member of a minority group" on a jury

because he will "almost always empathize

12

with the accused." See also, State v.

9 316 U.S. 400 (1942).

10 325 U.S. 398 (1945).

11 339 U.S. 282 (1950).

12 The book states:

"III. What to look for in a juror.

"A. Attitudes

"1. You are not looking for a fair juror,

but rather a strong, biased and sometimes

hypocritical individual who believes that

16

Washington, 375 So.2d 1 162, 1 163 (La.

1979), where the prosecutor testified that

he routinely struck Blacks because of his

perception that they favored the

13

accused.

but rather a strong, biased and sometimes

hypocritical individual who believes that

Defendants are different from them in kind,

rather than degree.

"2. You are not looking for any member of

a minority group which may subject him to

oppression— they almost always emphathize with

the accused.

"3. You are not looking for free-thinkers

and flower children."

Brown, McGuire, and Winters, The Peremptory Challenge

as a Manipulative Device in Criminal Trials: fradiz

tional Use or Abuse? 14 New Eng. L. Rev. 192,

224 (1978).

^ See also, New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 7, 1985,

p. A— 16, and the Jackson, Mississippi, Clarion

Ledger, July 15, 1983, p. 1A, quoting an Orleans

Parish and a Hinds County prosecutor, respectively,

to similar effect.

17

Our position is simple. The exclu

sion of a single juror because of his or

her race or national origin violates the

Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee of equal

protection. The issue in Swain, we

submit, was not whether the exclusion of a

single juror because of race violates the

constitution, but rather how one proves

the discriminatory motive of such a single

exclusion. The lower courts have confused

the two issues and have improperly read

Swain as limiting the finding of a

constitutional violation to those rare

circumstances where it can be shown that

prosecutors in case after case, over a

long period of time, have used peremptory

challenges to exclude Blacks. The con

tinued misinterpretation of Swain that

allows the decision to be used as a cover

18

for a discriminatory practice should be

repudiated.

We would also urge that the exclusion

of Blacks from juries through the use of

peremptory challenges violates the right

to a jury representative of a fair

cross-section of the community, by

destroying the opportunity of having a

representative jury seated. The lower

courts have misconstrued holdings of this

Court that there is no requirement that a

particular jury mirror the community.

These decisions do not hold that nothing

can be done to end a practice which

affirmatively prevents a representative

jury from being seated.

In this brief we will discuss the

Fourteenth and Sixth Amendments and will

suggest remedies to end the misuse of

19

peremptory challenges that will not

interfere with their proper use. First,

however, we will briefly discuss the

history of the peremptory challenge, and

particularly its use by the prosecution.

In this way the interest involved in the

prosecutor's right to peremptorily

challenge jurors, on the one hand, and the

interest in ensuring that the criminal

justice system is free from any taint of

racial discrimination, on the other, will

be put into proper perspective.

II.

THE HISTORY OF THE PEREMPTORY

CHALLENGE

At common law, the prosecutor did not

have the right to excuse peremptorily

- 20

potential jurors. Rather, that right

derives solely from statute, and gained

wide acceptance only in the last one

hundred years — around the time that the

post-Civil War constitutional amendments

were ratified and this Court began to

apply the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantee

of equal protection to the wholesale

exclusion of blacks from the jury and

14

grand jury systems.

In early English law, jurors func

tioned essentially as witnesses — as

fact-givers rather than fact-finders. The

Crown therefore initially exercised

complete control over their selection; any

unacceptable juror could be removed by the

15

prosecution. Parliament enacted the

See, op. cite supra n. 12, at 195.

Op. cite supra, n. 12, at 194; Comment, Swain v.

Alabama: A Constitutional Blueprint for the Perpe-

tuiticn of The All-White Jury, 52 Va. L. Rev. 1157,

1170-71 (1966)

21

16

Ordinance of Inquests in 1305 which

limited the Crown to challenging jurors

for "cause certain." On the other hand,

by the time of the American Revolution,

the peremptory challenge was firmly rooted

in the common law as one of a defendant1 s

greatest protections — in the words of

Blackstone, "a provision full of that

tenderness and humanity to prisoners, for

which our English laws are justly fa-

33 Edw. 1. c.2 (1305).

4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries 353.

In reaction to the Ordinance of Inquests the

English courts did fashion the practice of "standing

aside" jurors. The prosecution can require a juror

to whom it objects to "stand aside" until all other

potential jurors have been called; after the defen

dant has exercised all his challenges, if there are

too few veniremen remaining to compose a jury, only

then is the juror "stood aside" allowed to sit,

unless the Crown can show cause why he should not be.

As one court has noted, however,

17

mous.

16

The procedure of having a juror stand

aside is not a perempto

because, even when the

erplcyed by the Crown, Which is seldom, the

22

The peremptory challenge for the

defendant was thus a part of the common

law received by the American states, while

the grant of a similar privilege to the

18

prosecution was not. Extension of that

privilege to the prosecution was strongly

resisted in early state histories, and was

19

slow in gaining legislative acceptance.

Thus, while one early decision of this

Court asserted that the English practice

of standing jurors aside was part of this

juror who has been stood aside may be

actually seated as a juror after the

defendant has exercised his challenges.

Specifically, 26 Halsbury's Laws of

England, par. 624 (4th ed. 1579) states:

"The Crown has no right to make peremptory

challenges."

People v. Payne, 105 111. App. 3d 1034, 1039 n. 4

(111. Ct. App. 1982).

See op. cit. supra note 12, at 194.

Bor a review of this history, see op. cit. supra note

15, at 1170-73.

23

20

country's common law heritage, the Court

correctly held in 1856 that the prosecu

tor's right to stand jurors aside was not

part of American common law, and therefore

only applied in federal court if the state

in which the federal court was sitting

21

extended that right to prosecutors.

Although defendants in federal prosecu

tions were guaranteed the peremptory

22

challenge by statute in 1790, it was not

extended to all federal prosecutors until

23

1865.

In short, the peremptory challenge

was not recognized in the Colonies and new

States as a right of the prosecution.

20 United States v. Marchant, 25 U.S. 480, 483 (1827).

21 United States v. Shackleford, 59 U.S. 588, 590

(1856).

22 1 Stat. 119 (1790).

23 Act of March 3, 1865, ch. 86, § 2, 13 Stat. 500.

24

Rather, it was given to the defense as a

means of assuring the underlying right to

a fair and impartial jury guaranteed by

the Bill of Rights. It was a protection

of the people against governmental

overreaching. The use of peremptory

challenges by the prosecution to undermine

the right to a jury representative of the

community stands history on its head. As

we show below, it is at odds with the

Constitution.

III.

THE EXCLUSION OF BLACKS FROM JURY

SERVICE THROUGH THE USE OF PEREMPTORY

CHALLENGES VIOLATES THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT.

In order to illustrate our argument

that the use of the peremptory challenge

to exclude Blacks is a denial of equal

protection, we will use the following

25

hypothetical. By random selection from a

truly representative jury wheel, a single

Black is selected for the venire. The

prosecutor uses a peremptory challenge to

strike the sole Black juror, and announces

that he has done so for the specific

purpose of excluding any Blacks from

24

sitting on the jury. Finally, the

prosecutor confesses that it is his

experience that black jurors tend to favor

defendants, and therefore he believes it

is to his advantage not to have them sit

on the jury.

We submit that this hypothetical set

of facts would establish a clear violation

of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, the

hypothetical prosecutor's action is of the

type most clearly contemplated to be in

24 See State v. Washington, 375 So.2d 1162 (La. 1979).

26

violation of the Equal Protection Clause,

whose "central purpose . . . is the

prevention of official conduct discrimi

natory on the basis of race." Washington

v ■ Day i s , 426 U.S. 229, 239 (1976). Not

only is it an adverse action deliberately

taken on the basis of race, and therefore

presumptively illegal under many decisions

25

of this Court, but it is based on

notions of racial characteristics which

are anathema to the most fundamental

principles that the equal protection

26

clause seeks to protect.

Palmare v. Sidoti, ___U. S. , 80 L.Ed.2d 421, 425

(1964)? Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967);

Koreroatsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, 216 (1944).

26 YickWbv. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886); Hirabayashi

v. Qiited States, 320 U.S. 81, 100 (1943); Thiel v.

Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217, 220 (1946).

(1943); People v. Johnson, 22 Cal. 3d 296, 299, 583

P.2d 774, 775, 148 Cal.Rptr. 914, 916 (1978).

27

The problem presented by the misuse

of peremptory challenges arises only

because it will be the rare case in which

a prosecutor admits that the reason for

his action was race. In Swain, this Court

hypothesized another set of facts in which

a violation could be proven by a statisti

cal showing that over a long period of

time, in case after case, the prosecutor

consistently struck Blacks from juries.

However, the hypothetical facts set out in

Swain were taken by lower courts to be the

only circumstances in which a constitu-

28

tional violation could be found, and the

difficulty of assembling such a showing

27 380 U.S. at 223.

28 Sullivan, Deterring the Discriminatory Use of

~ -im. L. Rev. 477, 485

27

28

made it virtually impossible to prevail

regardless of the actual discriminatory

29

practice,

There are a number of reasons why, in

the twenty years since Swain, there have

been virtually no cases in which a

defendant has been able to demonstrate

that prosecutors have stricken Blacks in

case after case over a long period of

time. First, courts do not routinely

record voir dires, the race of jurors that

are excused, or the grounds of excusal.

Se c o n d , even where there are any records,

such as transcripts of voir dires, there

is no ready means to determine in which

oq See, e.g., United States v. Pearson, 448 F.2d 1207,

1217 (5th Cir. 1971); United States v. Childress, 715

F.2d 1313, 1317 (8th Clr. 1983), en banc. Of all the

cases cited in the Appendix,"Th only two, have

defendants been able to meet the Swain burden of

proof, and both involved the same prosecutor, who had

admitted under oath that he customarily struck all

black jurors. State v. Brown, 371 So.2d 751 (La.

1979); State v. Washington, 375 So.2d 1162, 1163-64

(La. 1975J7- --- ----

29

cases they have been made or kept. Third,

most criminal defendants lack the re

sources to conduct an investigation

adequate to assemble the necessary data.

Fourth , the issue will usually arise in

the middle of voir dire when Blacks are

st r u c k ; there will simply not be enough

time to conduct an inquiry unless a

lengthy continuance of the trial is

granted, with the accompanying disruption

of the orderly course of justice. Fifth,

for all of the above reasons, the only

evidence available as a practical matter

will be the testimony of presiding judges,

court clerks, and members of the bar as to

their recollection of events that occurred

in years past. Finally, unlike an

ordinary challenge to the make-up of the

jury rolls, it is also totally impractical

to raise the peremptory challenge issue in

an aff irmative inj unctive action. In

30

addition to the impossibility of assem

bling the proof, an order prohibiting the

prosecutor from striking Blacks because of

their race would be unenforcible without

proof that that was his intent in a

specific case.

The restrictive reading of Swain by

lower courts is inconsistent with other

decisions of this Court. In every other

c o n text , the Court has recognized the

ability of a trial judge to infer

discrimination from a wide variety of

30

circumstances. Thus , the misinterpreta

tion of Swain has resulted in anomalous

results in comparison to every other area

of discrimination. In one federal case,

30 E.g., McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) (erployment); anted States Postal Service Bd.

of Governors v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711 (1983) (employ

ment); Rogers v. lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) (voting);

Columbus Bd. of EdV v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979)

(school desegregation); Arlington Heights v. Metro

politan Housing Corp,, 429 U.S. 252 (1977) (govern

mental action).

31

for example, the defendants challenged the

make-up of the jury rolls as unlawfully

excluding Blacks. The district court

rejected the claim, holding that, although

it was a close question, the under-repre

sentation of Blacks was not enough to

establish a violation. The prosecutor

then proceeded to strike all the Blacks

from the venire when the actual jury was

assembled. Despite the mutually con

firming discriminatory practices, the

district court held that because of the

absence of a Swain showing of a long

history of striking Blacks, there was not

31a constitutional violation under Swain.

31 United States v. McDaniels, 379 F. Supp. 1243 (D. La.

1974). The court did order a new trial, however, "in

the interests of justice" pursuant to Fed. R. Crim.

P. 33. See also United States v. Leslie, 759 F.2d

366 (5th Cir. 1985), rehearing en banc granted, May

14, 1985.

32

Under ordinary rules for adjudication

of a claim of intentional discrimination?

however? these circumstances would have

allowed the court to draw the inference

that the prosecutor had a discriminatory

motive,, Similarly? when a prosecutor with

a limited number of pereroptories uses all

of them to exclude the few Blacks on the

panel? as occurred in petitioner Batson’s

case? a court should be permitted to

infer a discriminatory motive sufficient

to cast upon the prosecutor the burden of

coming forward with a "legitimate,

32

non-discriminatory reason" for his

33

action.

32 McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 803 (1974).

33 In the present case the trial court did not make such

a judgment because he specifically declined to make

any factual inquiry on an erroneous legal theory. The

court took the view that? as a matter of law, the

constitutional cross-section requirement was limited

to "the whole, entire panel and the selection

process," and that ”[a]ny body can strike anybody

they want to" without constitutional restraint.

(Appendix to Petition for Certiorari? at p. 16.) This

Other inquiries would permit a judge

to infer discrimination. Did the prosecu

tor strike all the Blacks called to the

jury box, or only some of them? How many

Blacks, absolutely or in comparison to

w h i t e s , were struck? What proport ion of

peremptories were use to strike Blacks?

Were Blacks questioned on voir dire, and,

if so, in the same way or as extensively

as the whites whom the prosecution

struck? What was the demeanor of the

prosecutor and the black potential jurors

during their exchanges? Did they appear

to be fair and impartial jurors? Did the

white jurors who were struck have common

attributes, visibly adverse reactions to

rule of law was expressly endorsed by the Kentucky

Supreme Court as the basis for affirming Batson' s

conviction cn appeal: "an allegation of the lack of

a fair cross section which does not concern a

systematic exclusion from the jury drum does not rise

bo constitutional proportions." (Id., at p. 5)]

34

the prosecutor, or obvious drawbacks from

a prosecutorial perspective? Did the

Blacks? Conversely, did the prosecutor

retain whites who had the same attributes

as the Blacks that were struck? Did the

prosecutor attempt to purge the jury of

Blacks by other means, e,g., did he

challenge Blacks for cause while passing

up equally available for-cause challenges

to whites? Did the prosecutor use his last

peremptory challenge to get rid of a

Black, in contravention of the well-recog

nized tactic of trial lawyers not to run

the risk of getting a worse replacement?

In short, trial court judges should

be given the freedom to infer intentional

discrimination from the totality of the

circumstances in the particular case

34

before them in the same way they may

United States Postal Service Bd. of Governors v.

Aikens, 460 U.S. 711 (1983). ~

35

infer such discrimination in a variety of

other types of cases decided since Swain.

Thus, as this Court noted in Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corp., 429

D.S. 252, 266 n. 14 (1977),

. . . [A] consistent pattern of

official racial discrimination is

[not] a necessary predicate to a

violation of the Equal Protection

Clause. A single invidious dis

criminatory governmental act would

not necessarily be immunized by the

absence of such discrimination in the

making of other comparable deci

sions .

In jury discrimination cases this

Court has also found a violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment by a showing that

eligible Blacks had been eliminated "at

each stage of the selection process until

ultimately an all-white grand jury was

selected to indict him" ini the particular

case of the defendant. Alexander v

36

Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 629 (1972)?5

In sum, the Fourteenth Amendment is

violated whenever the State denies equal

protection of the laws, even in a single

instance. Repeated denials of equal

protection need not be shown in order to

trigger the Amendment's protection in an

individual case.

35 Ihe Court noted that Alexander was not a case where

the systematic exclusion of Blacks over a period of

years had been shown. Rather, the proof went only to

the selection process for the particular venire and

jury. Id. See also Whit us v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545,

549-50 (1967): it is "the law of this Court as

applied to the States through the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, that a conviction

cannot stand if it is based on an indictment of

grand jury or the verdict of a petit jury from which

Negroes were excluded by reason of their race."

(Emphasis added.)

37

IV.

THE EXCLUSION OF BLACK JURORS

VIOLATES THE RIGHT TO HAVE A JURY

REPRESENTATIVE OF THE COMMUNITY.

A number of lower courts have held

that Swain should be reexamined in light

36

of subsequent decisions that have held

the Sixth Amendment guaranty of a repre-

37

sentative jury applicable to the states.

The question is: since the use of

peremptory challenges to exclude Blacks

results in unrepresentative juries, is the

practice unconstitutional?

O/T

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968); Taylor v.

Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975).

^ McCray v. Abrams, 750 F.2d 1113 (2nd Cir. 1984), reh.

en banc denied, 756 F.2d 177 (1985). People v.

Vheeler, 22 Cal.3d 258, 148 Cal. Rptr. 890, 593 P.2d

748 (1978); State v. Nail, 457 So.2d 482 (Fla. 1948);

Gamonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461, 387 N.E.2d 499

(1979) ;State v. Crespin, 94 N.M. 486, 612 P.2d 716

(1980) .

38

Taylor v, Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522

(1975), held that "[t]he unmistakable

import of this Court's opinions, at least

since 1940 . . . is that the selection of

a petit jury from a representative cross

section of the community is an essential

component of the Sixth Amendment right to

a jury trial.” 419 U.S. at 528. In Smith

v. T e x a s , 311 U.S. 128, 130 (1940), the

Court declared that exclusion of racial

groups from jury service was "at war with

our basic concepts of a democratic society

and a representative government.” Ballard

v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 ( 1946),

reversed a conviction by a jury from which

women had been excluded, relying on a

federal statutory "design to make the jury

a 'cross-section of the community.'" In

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443, 474 ( 1953),

39

the Court asserted that the source of jury

lists roust "reasonably reflect . . . a

cross-section of the population suitable

in character and intelligence for that

civic duty."

In Taylor the Court also relied on

its decision in the six-person jury case,

which had stated that a jury should "be

large enough to promote group deliberation

. . . and to provide a fair possibility

for obtaining a representative cross-sec

tion of the community." Williams v.

Florida, 399 U.S. 78, 100 ( 1970). On the

basis of this precedent, the Court

declared:

We accept the fair-cross-section

as fundamental to the jury trial

guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment and

are convinced that the requirement

has solid foundation. The purpose of

a jury is to guard against the

40

exercise of arbitrary power — to

make available the common sense

judgment of the community as a hedge

against the over-zealous or mistaken

prosecutor . . . This prophylactic

vehicle is not provided if the jury

pool is made up of only special

segments of the populace or if large,

distinctive groups are excluded from

the pool. Community participation in

the administration of the criminal

law, moreover, is not only consistent

with our democratic heritage but is

also critical to public confidence in

the fairness of the criminal justice

system . . . [T]he broad representa

tive character of the jury should be

maintained, partly as assurance of a

diffused impartiality and partly

because sharing in the administration

of justice is a phase of civic

responsibility.' Thiel v. Southern

Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217, 227 (1946)

(Frankfurter, J ., dissenting).

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. at 530-31.

41

The requirement of a fair cross-sec

tion theory in jury selection has also

been adopted by statute as "the policy of

38

the United States." Taylor quoted

approvingly from the House Report on the

Federal Jury Selection and Service Act:

It must be remembered that the

jury is designed not only to under

stand the case, but also to reflect

the community's sense of justice in

deciding it. As long as there are

significant departures from the cross

Federal Jury Selection and Service Act of 1968, Pub.

L. 90-274, 82 Stat. 53, 28 U.S.C. §§ 1861 et seq.

Section 1862 provides that:

No citizen shall be excluded from service as a

grand or petit juror . . . on account of race,

color, religion, sex, national origin, or

econanic status.

See also, Section 2 of the Uniform Jury Selection and

Service Act (National Conference of Commissioners on

Uniform State laws, 1970), and Md. Ann. Code §

8-1-13. The Uniform Act has been substantially

adopted by eight states. Colo. Rev. St. §§ 13-71-107

to 13-71-121 (1971); Idaho Code §§ 2-201 to 2-221

(1971); ESiwaii Rev. Stat. §§ 612-1 to 612-26 (1973);

Indiana Code §§ 33-4-5.5-1 to 33-4-5.5-22 (1973); 14

Maine Rev. St. §§ 1211 et seq. (1971); Minn. Stat.

Ann. §§ 593-31 to 593-50 (1977); Miss. Code 1972, §§

13-5-2 et sea. (1974); No. Dakota Code §§ 17-09.1-01

to 27-09.1-22 (1971).

42

sectional goal, biased juries are the

result -- biased in the sense that

they reflect a slanted view of the

community they are supposed to

represent.

419 U.S. at 26 n. 37.

The argument based on the Sixth

Amendment is not inconsistent with

decisions of this Court which hold that

the defendant has no right to have his

particular jury represent the community

39

with precision. Thus, for example, in a

community in which one third of the

persons eligible for jury service are

Black there is no right to have a jury

with four Blacks out of the 12 jurors.

Although this proposition is correct,

it does not negate the conclusion that the

Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404, 413 (1972) (plu-

rality opinion); Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261, 284

(1947).

43

affirmative use of peremptory challenges

to produce an unrepresentative jury

violates the Sixth Amendment. What the

Court has held is that, assuming a system

of jury selection which results in jury

lists that are representative of the

community, the use of a neutral device to

select particular juries does not violate

the Fourteenth Amendment just because in a

particular case the jury may not precisely

40

mirror that community. Put another

way, although there is an affirmative

obligation to have a process by which a

representative jury can be chosen, there

is not an affirmative obligation to

achieve the result of juries that are

precisely representative.

40 See, e.g., Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. at

44

Bat the converse must also be true:

there is a right not to have selection

methods that result in unrepresentative

juries. The protections of the Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendments cannot stop with the

composition of the jury roll (or "drum" in

this case), but extend to the selection of

the specific jury itself. See Ballew v.

Georgia, 435 U.S. 223 (1978); Alexander v.

Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972). Thus, a

defendant has the right to a fair oppor

tunity for a jury on which are represented

the various groups that make up the

community in which he is tried. To allow

the unscrutinized use of peremptory

challenges on the basis of race biases the

process as surely as the exclusion of

Blacks from the jury lists or drum.

The right to a fair cross-section is

45

not based on the notion that individuals

vote to convict or acquit because of the

racial group to which they belong; rather,

it derives from the principle that juries

should contain representatives of the

various groups in the community so that

their opinions, voices, points of view,

and perceptions come to bear on the

deliberative process. When a prosecutor

removes Blacks from the jury the result is

a jury which is insulated from one of

41

those viewpoints and voices.

The question of whether the use of

peremptory challenges has violated the

cross-section requirement will, after all,

only arise in a particular case when a

fair system has produced a panel of

potential jurors that includes Blacks.

Bsters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493, 503-04 (1972); see op.

cit. supra n. 28, for an example of the impact on a

"jury's deliberations of the experiences of a black

juror.

46

Unless the prosecutor strikes them, a

representative jury will sit. If then the

prosecutor makes the jury unrepresentative

by striking some or all of the Blacks, his

abuse of the peremptory challenge violates

42

the Sixth Amendment.

To illustrate, one may assume a county that is 20%

black and that has a jury roll that is also 20%

black. In trial #1, 20 potential jurors are randomly

selected, one of whan is black, a result well within

the range of probability. That single Black is

excused for a valid, racially-neutral reason, and an

all-white jury sits. That result does not violate

the Sixth Amendment.

In trial #2, twenty potential jurors are

randomly selected, 4 of whom, or 20%, are black.

Through neutral selection criteria 2 of the 12

jurors to sit will be black, or almost 20%. The

prosecutor then affirmatively creates a non-repre

sentative jury by striking the two Blacks. That

result does violate the Sixth Amendment.

47

V.

EFFECTIVE, MINIMALLY INTRUSIVE MEANS

EXIST TO REMEDY THE UNCONSTITUTIONAL

MISUSE OF PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES

Amici believe that it is clear that

the exclusion of Blacks from juries

through the use of peremptory challenges

violates both the Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution. There are

numerous ways in which these violations

can be remedied. They will of necessity

vary from locality to locality depending

on the particular jury selection practices

in use. The appropriate remedy may also

vary with the nature of the constitutional

violation, depending on the amendments

invoked. Amici therefore suggest that the

lower state and federal courts be given

48

leeway to develop appropriate remedies in

light of local practices and condi

tions .

In the first analysis, however, the

prophylactice effect of a pronouncement by

this Court that the misuse of peremptory

challenges violates both the Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendments cannot be over-esti

mated. At present, prosecutors can and do

indulge the same misinterpretation of

Swain that prevails in the lower courts.

They think that the "case after case"

language in the Swain opinion defines a

substantive principle of constitutional

law rather than a principle relating to

the sufficiency of factual proof based on

statistics (see page 27, supra) . Thus,

the prosecutor who is conscientious in his

desire to obey the Constitution never-

49

theless sees nothing unconstitutional

about peremptorily challenging blacks qua

blacks in particular cases, so long as he

does not do it in all cases. Told that

this is indeed unconstitutional, the

conscientious prosecutor will stop doing

it.

To the extent that prosecutors do not

stop misusing peremptory challenges, the

primary agency for enforcing the Constitu

tion will be the trial judge, in pro

ceedings prior to the attachment of

jeopardy. As this Court has recognized in

43

other contexts, trial judges are

experienced and discerning in the inter

pretation and understanding of what is

being conveyed by the demeanor and

interaction of the participants during the

See, Rosales-Lopez v. United States, 451 U.S. 182

(1982); Patton v. Yount, ___U.S. ___ , 81 L.Ed.2d 847

(1984); Wainwright v. Witt, U.S. , 83 L.Ed.2d

841 (1985).

50

process of jury selection. They are fully

capable both of recognizing a prima facie

case of racially discriminatory peremptory

challenges by the totality of the circum

stances of the case before them, and of

taking effective action to remedy the

abuse.

The first thing that a trial judge

faced with an apparent prosecutorial

misuse of peremptories may do is to ask

the prosecutor for an explanation. This

alone will often suffice to warn the

prosecutor that his behavior is under

scrutiny, and make him change his ways. If

his explanation for his past behavior is

unsatisfactory, or if his behavior

persists under circumstances that render

the explanation hollow, the trial judge

then has numerous options to correct the

51

problem. He can disallow a peremptory,

dismiss the partially-selected jury and

bring in a new panel, or take other

pretrial corrective action.

For example, there exists a simple,

direct, and highly effective way both to

correct the exclusion of Blacks and to

leave undisturbed the proper use of

peremptory challenges. A state need only

adopt a practice that would permit defense

counsel to object upon the exclusion of a

member of a racial or national origin

minority group member. From that point on,

if a black, Hispanic, etc., juror were

excluded by use of a peremptory challenge,

he or she would be replaced by a member of

the same group. This would be directly

responsive to the nature of the violation,

insuring a representative cross-section of

52

the community on the jury. At the same

time, it allows the prosecution to strike

a juror for any reason other than race.

Such a rule would also have the great

advantage of not requiring the prosecutor

to explain the reasons for any challenge.

Moreover, the mere existence of the rule

would do much to end any discriminatory

practice since prosecutors would know

ahead of time that they would be unable,

as a practical matter, to use challenges

44

to exclude all Blacks from juries.

Another possibility is the highly

successful remedy that has been working

for more than six years in California and

44-------- ----Although this particular rule would be a race-con

scious remedy, it would not adversely affect the

rights of a person who was not a member of the

minority group, since that person would simply be

selected later and would not lose his or her right to

jury service.

53

45

Massachusetts without impeding the

efficient administration of justice, or

infringing significantly upon the wide

discretion that has been traditionally

accorded to prosecutors in the exercise of

their peremptory challenges.

Briefly stated, the system developed

by California and Massachusetts requires

that the defendant demonstrate a prima

facie case of discriminatory intent before

the trial judge will look beyond the

traditional presumption that the prosecu

tor is using his peremptory challenges in

a permissible manner. If the judge finds

that a prima facie case has been made, the

prosecutor is given the opportunity to

45 See People v. Wheeler, 583 P.2d 748, 148 Cal. Rptr.

890 (1978) (Mosk, J.); Commonwealth v. Soares, 377

Mass. 461, 387 N.E.2d 499 (197$). This model has

been adopted elsewhere. See State v. Crespin, 94

N.M. 486, 612 P.2d 716 (1980)? State v. Neil, 457

So.2d 481 (Fla. 1984), and State v. Gilmore, No.

A-870-82 T4 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div., March 8,

1985).

54

show that his challenges are not predi

cated on group bias. The reasons for the

challenges do not have to be sufficient to

sustain a challenge for cause, but could

relate to any of the many legitimate

46

reasons for peremptory challenges. The

judge will examine the prosecutor's

reasons and will dismiss the venire or

47

panel or disallow the particular

48

challenge only if the prosecutor fails

See People v. Hall, 672 P.2d 854, 859, 197 Cal. Rptr.

71 (1983); People v. Wheeler, 583 P.2d at 760, 148

Cal. Jptr. 890. See, e.g., Commonwealth v. Kelly, 10

Mass. App. 847, 406 N.E.2d 1327, 1328 (Mass. App. Ct.

1980) (accepting prosecutor's challenge based on the

prospective juror's "demeanor, manner and the 'smirk

on her face'"); People v. Walker, 157 Cal. App. 3d

1060, 205 Cal. Ifctr. 278, 280 (Ct. App. 1984) (trial

court accepts prosecutor's explanation that a

prospective juror "stood out as 'a comic'"),

47 People v. Wheeler, 583 P.2d at 765. Whether the

venire as a whole*or only the panel drawn for the

particular case would be dismissed, could depend on

the procedures used in the jurisdiction and the

practicality of assembling a new venire without

delay.

48 Qarmanwealth v. Perry, 15 Mass. App. 932, 444 N.E.2d

1298, 1300, (Mass. App. Ct. 1983), further appellate

review denied, 388 Mass. 1104, 448 N.E.2d 766 (1983);

55

to persuade the court that the challenges

were exercised for nondiscriminatory

reasons.

This remedy for the discriminatory

use of peremptory challenges leaves the

jury selection process unaffected in the

49

vast majority of cases. In order to

precipitate such an inquiry, the defen-

50

dant must demonstrate a "strong likeli-

Gamonwealth v. Reid, 384 Mass. 247, 424 N.E.2d 495,

500 (Mass. 1981).

Amici have examined all of the reported cases in

California and Massachusetts involving claims by

criminal defendants of racial discrimination under

Wheeler and Soares. There have been a total of 15

such cases in California (an average of barely more

than 2 a year.) In Massachusetts, where the Soares

case has been in effect for six years, there have

been 13 such cases. (In New Mexico, which adopted the

Wheeler~Soares approach five years ago, there has

been only one reported case involving a claim under

the rule.)

In Massadhuetts, judges occasionally investigate the

discriminatory use of peremptory challenges on their

own initiative. See Commonwealth v. Joyce, 18 Mass.

App. 417, 467 N . O d 214, 218 (Mass. App. Ct.1984),

further appellate review denied, 470 N.E.2d 798

( M ) 7 — -------- ----------------------------------

56

hood" that Blacks "are being challenged

because of their group association rather

than because of any specific bias". This

showing may be on the basis of evidence

such as that suggested at pp. 30-34,

51

the nature of the questioning,

the demeanor of the potential jurors or

the prosecutor, cf. Patton v. Yount, ___

U.S. ___ , 81 L.Ed. 2d 847 ( 1984), or any

other of a number of factors that ordi

narily permit a trier of fact to infer

bias.

People v. Wieeler, 583 P.2d at 764. The California

court listed sane of the factors the defendant might

rely upon in demonstrating discriminatory uses of

challenges. These were (1) that the prosecutor had

struck most or all of the members of the identified

group from the venire or (2) that he had used a

disproportionate number of his peremptory challenges

against members of the group or (3) that the jurors

in question have only their group identification in

cormon and that they otherwise are as heterogeneous

as the community as a whole. 583 P.2d at 764, 148

Cal. iptr. 890. Courts will also consider the race

of the defendant and the victim and whether the

prosecutor's questioning of the excluded jurors was

"desultory." Id.

57

One trial judge, disagreeing with his

own Circuit Court of Appeals, has argued

that providing a remedy for the misuse of

peremptory challenges will necessitate

"twelve mini-trials" in every case. See

Roman v. Abrams, No. 85 Civ. 0763-CLB,

slip. op. at 20 (S.D.N.Y. May 15, 1985).

The record in California and Massachu

setts, the two states with the longest

experience with this remedy, refutes this

charge. The California Supreme Court has

recently found no empirical evidence to

support a claim that this remedy has

proved "unworkable" in the trial courts.

People v. Hall, 672 P.2d 854, 859, 197

Cal. Rptr. 71 (1983) (en banc).

Even though minimally intrusive, the

Wheeler-Spares remedy has been effective

in reducing the intentionally discrimi-

58

natory use of peremptory challenges, as

the recent reported decisions in Cali

fornia and Massachusetts attest. None of

these cases involves a fact pattern

showing as blatant a misuse of peremptory

challenges as occurred before Wheeler and

5 2Soares were decided. _■— ---- Compare , e »g , ,

People v. Cobb, 97 111. 2d 465, 455 N.E.2d

31 (1983). The experience in California

and Massachusetts demonstrates that the

discriminatory use of peremptory chal

lenges is not only reprehensible but also

53

remediable.

In Soares itself, the prosecution used peremptory

challenges to eliminate twelve of the thirteen black

venirepersons. 387 N.E.2d at 508. In Wheeler, the

state excluded all of the blacks in the venire

(approximately seven) by using peremptory challenges.

583 P.2d at 752-54.

There are, of course, other possible remedies,

including abolishing peremptory challenges or

limiting them to the defense as under the common law.

A state may went to provide for additional voir dire,

so that the prosecutor (and defense counsel) will

have a more informed basis for exercising their

challenges. Indeed, the California Supreme Court has

59

None of the potential available

remedies impedes the vigorous and

effective prosecution of crime; none

delays trials more than momentarily or

encumbers them significantly. Indeed,

administration of the rule would involve

less disruption of trials than the

"case-after-case" rule currently applied:

under the prevailing misinterpretation of

Swain jury selection must be suspended

pending an evidentiary hearing into the

prosecutor's record in past cases.

recently expanded the scope of voir dire by holding

that counsel may asik questions reasonably designed to

assist in the intelligent exercise of peremptory

challenges even if such questions may not uncover

grounds sufficient to sustain a challenge for cause.

People v. Williams, 628 P.2d 869, 174 Cal. Rptr. 317

(Cal. 1981) (en banc). Thus, prosecutors are given

an opportunity to uncover evidence of specific bias

and to exercise their peremptory challenges in a

constitutional manner. Id. at 875.

60

Conclusion

No one can "deny that, [more than 114

years after the close of the War Between

the States and nearly 100 years after

Strauder, racial and other forms of

discrimination still remain a fact of

life. . . . " Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S.

at 558 . The final cutting off of all

means to perpetuate the practices first

condemned in Strauder is not only overdue,

but essential to ensure both the reality

and the appearance of justice in our

society.

For the foregoing reasons, the

decision below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted

JULIOS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON *

STEVEN L. WINTER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York University

Law School

40 Washington Square South

New York, N.Y. 10012

SAMUEL RABINOVE

The American Jewish

Committee

165 East 56th Street

New York, N.Y. 10022

LOIS WALDMAN

The American Jewish

Congress

15 East 84th Street

New York, N.Y. 10028

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177