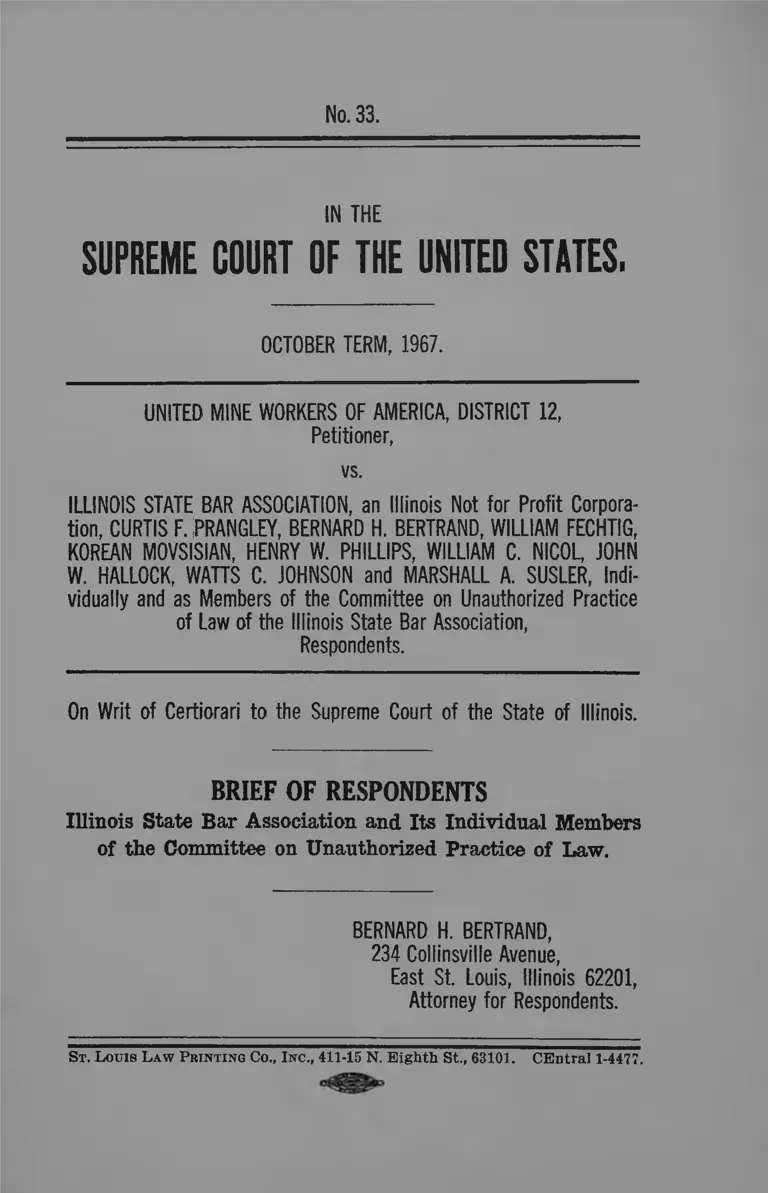

United Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Association Brief of Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Association Brief of Respondents, 1967. 06c62d2d-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d07b619a-976c-4fd9-a90e-5ce917fa90f5/united-mine-workers-of-america-district-12-v-illinois-state-bar-association-brief-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 33.

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM , 1967.

UNITED M INE WORKERS O F AM ERICA, DISTRICT 12,

Petitioner,

vs.

ILLINOIS STATE BAR ASSOCIATION, an Illinois Not for Profit Corpora

tion, CURTIS F. PR A N G LEY, BERNARD H. BERTRAND, WILLIAM FECHTIG,

KOREAN MOVSISIAN, H EN R Y W. PH ILLIPS, W ILLIAM C. NICOL, JOHN

W. HALLOCK, WATTS C. JOHNSON and M ARSHALL A. SU SLER, Indi

vidually and as Members of the Committee on Unauthorized Practice

of Law of the Illinois State Bar Association,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Illinois.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS

Illinois State Bar Association and Its Individual Members

of the Committee on Unauthorized Practice of Law,

BERNARD H. BERTRAND,

234 Collinsville Avenue,

East St. Louis, Illinois 62201,

Attorney for Respondents.

St. Louis L aw P rinting Co., I nc., 411-15 N. Eighth St., 63101. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Table of Contents.

Page

Constitutional, Statutory Provisions and Canons of

Ethics Involved ......................................................... 1

Questions Presented ................................ 2

Statement of the Case .................................................... 3

Summary of Argument .................................................. 11

Argument ............................................................................. 14

I. The decision below is clearly correct ............... 14

A. An attorney may charge a fee for services

rendered in handling Workmen’s Compensa

tion Act cases .................................................. 20

B. The Labor-Management Relations Act does

not authorize or have within its purview the

union salaried lawyer arrangement consid

ered by the Illinois Supreme C o u rt............. 22

C. Petitioner’s arguments run contra to facts

as well as opinions of committees on profes

sional ethics. Its analogies are wanting in

support ............................................................. 25

D. The injunctive decree was proper and com

plete for the purposes intended ................. 28

II. The Illinois Supreme Court decision does not

deny the petitioner any constitutionally pro

tected right nor does the state decision conflict

with any decision of this Court ......................... 30

III. A discussion of group legal services is not per

tinent to the issues in this case ......................... 36

Conclusion ......................................................................... 37

11

Appendix A—Workmen’s Compensation Act ............. 39

Appendix B:

Exhibit A—Eeport to attorney on accidents .......... 42

Exhibit B—Letter to Union officers and members

dated September 23, 1959 ....................................... 44

Exhibit B—Letter to Union officers and members

dated September 26, 1959 ........................................ 46

Appendix C—Statement of American Bar Association

re Informal Opinion No. 469 12/26/61 ..................... 47

Appendix E>—Formal Opinion 282 ............................... 49

Table of Cases.

Beckemeyer Coal Co. v. Ind. Comm., 370 111. 113 (1938) 18

Chicago, Wilmington & Franklin Coal Co. v. Ind.

Comm. (Matchek), 400 111. 60 (1948) ..................... 18

Chicago, Wilmington & Franklin Coal Co. v. Ind.

Comm. (Sarafin), 399 111. 76 (1948) ........................... 18

Federal Trade Commission v. Beech Nut Co., 257 U. S.

4 4 1 .................................................................................... 29

Franklin County Coal Co. v. Ind. Comm., 398 111. 528

(1948) ............................................................................. 18

Illinois State Bar Association v. United Mine Work

ers, District 12, 35 111. 20, 112, 219 N. E. 2d 503

(1966) ........................................................................... 17

In re Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 13 111. 2d

391, 150 N. E. 2d 163 ......... 11,16,23

John Florczak v. Ind. Comm., 381 111. 117 (1942) ___ 18

Lasley v. Tazewell Coal Co., 223 111. App. 462 __ 20,21

NAACP V. Button, 371 U. S. 415 ............... 20, 30, 31, 33, 36

New York, New Haven and Hartford Ry. Co. v. Inter

state Commerce Commission, 200 U. S. 3 6 1 ............. 30

NLRB V. Express Publishing Company, 312 U. S. 42 29

Ill

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Association v. Chicago

Motor Club, 362 111. 50, 199 N. E. 1 ......................... 14

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Assn. v. Lally, 313 111. 21,

144 N. E. 329 (1924) .................................................... 21

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Association v. The Mo

torists Association of Illinois, 354 111. 595, 188 N. E.

827 .................................................................................. 14

People ex rel. Courtney v. Association of Real Estate

Taxpayers of Illinois, 354 111. 102, 187 N. E. 823 .. 14

Sperry v. State of Florida, 373 U. S. 379 .................... 36

Swift & Company v. IT. S., 196 U. S. 375 ................... 30

Virginia Brotherhood (377 U. S. 1, April 20,

1964) ........................................................................30,31,33

Constitution, Statutes and Canons of Ethics.

Canons of Ethics of the Illinois State Bar Association 1-2

Constitution of the United States:

First Amendment .......................................................... 1

Fourteenth Amendment .............................................. 1

Hurd, 111. Rev. Stat. 1915, § 1 5 3 .................................... 26

Labor Management Relations Act, 29 U. S. C. A.,

§141 ...........................................................................2,22,23

111. Rev. Stat. 1963, Ch. 48, § 138.19 ............................. 25

111. Rev. Stat. 1963, Ch. 63, § 1 4 .................................... 24

Illinois Workmen’s Compensation Act, Illinois Revised

Statutes (1959), Ch. 48, §138.19 (1) (2), 138.19 (c),

§138.16 ................................................................2,17,21,22

Miscellaneous.

Carlin and Howard, Legal Representation and Class

Justice, 12 U. C. L. A. L. Rev. 381, 386 ................. 19

Carlin, Ethics and the Legal Profession (1965) ........... 19

No. 33.

T H E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM , 1967.

UNITED M INE WORKERS OF AM ERICA, DISTRICT 12,

Petitioner,

vs.

ILLINOIS STATE BAR ASSOCIATION, an Illinois Not for Profit Corpora

tion, CURTIS F. PR ANGLEY, BERNARD H. BERTRAND, W ILLIAM FECHTIG,

KOREAN MOVSISIAN, HENRY W. PHILLIPS, WILLIAM C. NiCOL, JOHN

W. HALLOCK, WATTS C. JOHNSON and M ARSHALL A. SUSLER, Indi

vidually and as Members of the Committee on Unauthorized Practice

of Law of the Illinois State Bar Association,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the State of Illinois.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS

Illinois State Bar Association and Its Individual Members

of the Committee on Unauthorized Practice of Law.

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY PROVISIONS AND

CANONS OF ETHICS INVOLVED.

Pertinent constitutional provisions consisting of the

First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution

of the United States; Canons of Ethics of the Illinois

2 —

State Bar Association; Illinois Workmen’s Compensation

Act, Illinois Eevised Statutes (1959), Ch. 48, § 138.19

(1) (2), 138.19 (c), § 138.16, and 29 U. S. C. A., § 141,

Labor Management Relations Act, are involved (Appen

dix A).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

The Respondents adopt Nos. 2, 3 and 4 of this section

as stated by Petitioners, but object to portion of No. 1

insofar as it asserts that the attorney’s salary was paid

by the Union from membership dues. The record refutes

that statement (R. 15). In sworn answers to interroga

tories, the Union responded: “ No portion of dues is allo

cated to pay attorneys’ salary” .

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

The legal proceeding in this case began with the filing

of a complaint in the Circuit Court of Sangamon County,

Illinois, wherein, the Illinois State Bar Association, and

members of its Unauthorized Practice of Law Committee,

as plaintiffs, brought suit against the United Mine Work

ers of America, District 12, as defendants (R. 1-4). The

pleadings alleged that the Illinois State Bar Association

(hereinafter referred to as “ Bar Association” ) is a not-

for-profit corporation organized for the purpose of estab

lishing and maintaining the honor and dignity of the

courts and of the profession of law, the protection of the

public, the fostering and promoting of a high standard

of professional ethics, and the due administration of

justice in all courts in the State. The United Mine Work

ers of America, District 12, is a labor union, and appeared

in court in response to the complaint in the name of

Joseph Shannon, a member of District 12, and all members

of said association made parties by representation. The

complaint charges the Union has been engaged in the

practice of law in Illinois by employing an attorney on

a salary basis for the purpose of representing its members

with respect to their individual claims for compensation

under the provisions of the Workmen’s Compensation Act

of the State of Illinois. The complaint further charged

that the Union is not and cannot be licensed to practice

law in the State of Illinois, and despite its lack of au

thority has offered, furnished and rendered legal services

and advice. These activities are charged to be, among

other things, contrary to public policy, and “ not only

tend to degrade the legal profession and to bring the

same into bad repute in the administration of justice, but

also tend to mislead and defraud the public.” The Bar

Association in conclusion sought an injunction restraining

and enjoining the defendant, its agents or employees from:

1. Giving legal counsel and advice.

2. Rendering legal opinions.

3. Representing its members with respect to Work

men’s Compensation claims and any and all other

claims which they may have under the statutes and

laws of the State of Illinois.

4. Practicing law in any form either directly or

indirectly.

5. Advertising, advising or holding itself out to

members or others as practicing law or as having

a right to practice law.

6. Charging or collecting fees, commissions or pay

ments or apportioning dues of members in any form

for legal services.

Defendant, acting through Joseph Shannon, a member

of District 12, United Mine Workers of America and all

the members of the association made parties by repre

sentation, then moved the Court for an order directing the

Bar Association to make the complaint more definite and

certain as to the allegation that defendant, on occasion,

filed claims with the Industrial Commission for and on

behalf of a member without obtaining the member’s per

mission, authorization or approval (R. 5). In response

to an order entered on this motion the Bar Association

pleaded that one Elery D. Morse, East Walnut Limits,

Canton, Illinois, a UMW member was injured on July 18,

1961, in the course of his employment. In March, 1962,

Morse retained the services of Claudon and Elson, attor

neys, 21 W. Elm Street, Canton, Illinois, to file his appli

cation for adjustment of claim in regard to his claim

against the Midland Electric Coal Corporation with the In

dustrial Commission of Illinois. On June 28, 1962, Claudon

and Elson filed an application for adjustment of claim

for Mr. Morse, Case No. 712,133, before the Industrial

Commission. One month later, on July 23, 1962, M. J.

Hanagan, salaried attorney for United Mine Workers Dis

trict 12, filed a similar application for Elery Morse, Case

No. 713,647, without Morse’s consent, approval, authori

zation, and without knowledge of the previous application

having been filed (B. 6).

An answer by the Union was filed admitting the general

allegations relating to the Bar Association and its individ

ual members, and the existence of the Union. The Union

denied it was engaged in the practice of law, but admitted

the employment of an attorney on a salary basis for the

sole purpose of representing the members in their individ

ual claims before the Industrial Commission of the State of

Illinois. The pleading denied filing without a member’s per

mission, and as to the pleaded facts relating to Elery

Morse, denied same, and stated further, that, even if true,

such matter was immaterial to this case. It was further

admitted that as an association it is not and cannot he

licensed to practice law in Illinois. All other matters

pleaded were likewise denied (E. 7-8).

The Union moved to strike the portions of the pleadings

referring to the Elery Morse incident and for judgment

on the pleadings (R. 8-10). This motion was denied by

the trial court. The Union, one week later, filed a motion

for reconsideration of the order denying motion for judg

ment on the pleadings stressing a violation of Section 19,

of Article 2 of the Constitution of the State of Illinois and

of the rights allegedly guaranteed the Miners by the First

and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution of the

United States. After hearing, this likewise was denied

(E. 11).

Interrogatories were filed by the Bar Association and

served upon the defendant’s attorney (R. 55-62). Objec

tions were made to the interrogatories and some were

eliminated by order of court.

— 6

In the answers to plaintiffs’ interrogatories, the officers

of the Union were identified. I t was disclosed that the

Union had 8500 working members. It had offices in Spring-

field, Taylorville, DuQuoin and West Frankfort, Illinois.

On legal aid, information was supplied naming an inter

national special representative from Lewistown, a district

special representative from Thompsonville, two secre

taries (one in Springfield and one in West Frankfort) and

the added information that local unions designate an

officer or member to “assist other members in preparing

and filing reports of accidents occurring in mines over

which they have jurisdiction”. The salaried attorney was

identified as Stuart J. Traynor of Taylorville, Illinois, and

it was stated that members by themselves or with assist

ance of someone in the local union prepare, sign and file

for the attorney, either in Springfield or West Frankfort,

a report of accident.

Attached to the answers and made a part thereof were

three exhibits. Exhibit “A” was a Report to Attorney on

Accident, Exhibit “B” was a letter from the union a t

torney to local Union officers and members, and Exhibit

“C” was a letter from the president to the same people

written four years later (Appendix B).

The Union admitted that the present attorney does not

see and interview each injured member before starting a

claim.

Stuart Traynor, up to date of answers to interroga

tories, (January, 1964 to February 2, 1965) had filed 590

applications for adjustment of claims, had concluded 637

files, and had collected $737,998.27 for the injured miners

or their families. William D. Hanagan, serving only an

interim term, filed only 20 applications for adjustment of

claim, settled 87, and collected $100,723.24. His father,

M. J. Hanagan, who held the position of salaried attorney

for many years, from January 1, 1961 until his death in

— 7-

June of 1963, filed 1318 applications, concluded 1328

claims and collected $1,859,640.65.

The interrogatories, further disclosed, that M. J. Hana-

gan received a salary of $12,400 plus $2,236.54 expenses

for a total of $14,436.54 in 1961; a total of $14,954.79 in

1962 and until his death in 1963, the sum of $7,044.16 ̂

William D. Hanagan received a salary of $3,099.96 and

expenses of $323.05, for a total of $3,423.01. Stuart J.

Traynor from January through November, 1964, earned

a salary of $11,366.68 and received expenses of $1497.60

for a total of $12,864.28.

At a meeting of the Executive Board of the Union on

August 5, 1963, a motion was made and passed unani

mously authorizing the acting president, Joseph Shannon,

to make arrangements with Stuart Traynor of Taylor-

ville, Illinois for the purpose of retaining him “to handle

District 12 compensation cases.”

Dues of each member have been $5.25 per month since

November 1, 1964, but no portion of the dues is allocated

to pay attorneys salary.

In addition to interrogatories submitted to defendant,

the deposition of Stuart J. Traynor was taken (R. 31-54).

In answer to questions, he advised that he was employed

by the United Mine Workers of America, District 12,

since October 1963, with direction and authorization to

represent members of District 12 in claims for Work

men’s Compensation Benefits under the Illinois Workmen’s

Compensation Act. He disclosed his salary of $12,400 a

year, that he is responsible and obligated to represent

miners, no matter how many may have claims during any

particular year, and his salary neither increases or de

creases based on number of claims handled. The union

never requires him, as part of his employment to do

work outside the State of Illinois. He does not consider

himself hired to render legal advice on the running of

District 12 or any of its internal affairs. His main func

tion is to represent individual members when that person

is hurt in a mining accident wherein he would qualify

under the Workmen’s Compensation Act of the State of

Illinois. He maintains an office at Taylorville, for his

services with the United Mine Workers, and the Union

maintains office space at Springfield and West Frank

fort. I t is generally known among the members of the

Union that they have a lawyer available to them for the

purpose of presenting their claim before the Industrial

Commission and this is true whether or not they know

him personally. Because of his residence in Taylorville,

a considerable distance from West Frankfort, he would

not be one of the lawyers in the West Frankfort area

with whom the members would be personally familiar.

Most applications for adjustment of claim are signed

outside of his presence. The miner can obtain the Report

to Attorney form at the mine and need not go to either

of the two offices, but sends it in. A secretary then fills

out the application without the man being present and

the attorney signs it. Traynor acknowledged that he

could not find any language in the Report to Attorney

that in any way instructs him to file a claim or hires him

to do so as an individual. The application is sent in to

the Industrial Commission, after a secretary signs the

attorneys name on the form and at the time of this

filing, in most instances, he has not seen the injured em

ployee. The member secures all the medical reports for

the attorney, either from the company doctor or from

someone else, if the member is in need of further medical

attention. In preparing for a hearing before an Arbi

trator he does not send out advance notice for a confer

ence with the injured miner before the hearing. Some

drop in and see him ahead of time, but if they did not,

the first time the attorney would see him would be the

day of the hearing at place of the hearing. He confers

— 9 —

with the coal company lawyer and if they agreed as to

the figure of settlement, a settlement contract is pre

pared and presented, otherwise they have a hearing be

fore the Arbitrator for his decision. Although he has

represented miners for private matters in his three

county areas, he has never represented miners from the

West Frankfort area for their private purposes. This

individual representation has been more in the probate

field than anything else.

He received his first contact from the Union in August,

1963 when he was told Mr. Shannon would like to talk

to him. He was told it was necessary for the Union to

hire an attorney to carry on the work of Mr. Hanagan.

The next event was his receipt of a letter dated Sep

tember 26, 1963, from Mr. Shannon advising him that he

had been hired.

There was an error in the original answers to interro

gatories which are corrected as follows:

14 (d) $737,998.27.

This change is due to fact that from October to Decem

ber of 1963, he filed 174 applications for adjustment of

claim in his name and closed 150 cases for a total

recovery of $209,113.14.

Subsequently, the plaintiffs moved to strike paragraph

7 from their pleadings and the same was allowed.

After the pleadings were settled, the intenrogatories an

swered and the deposition of Stuart Traynor accomplished,

the United Mine Workers filed a motion for summary de

cree and, upon receipt thereof, the Illinois State Bar As

sociation countered with their own motion for summary

judgment. These motions were heard by the Honorable

Creel Douglas, Chief Judge of the 7th Judicial Circuit,

State of Illinois, and on September 7, 1965, he entered an

— 10 —

order denying the relief sought by the United Mine Work

ers of America, District 12, and granted the motion of the

Illinois State Bar Association, and thereby enjoined the

United Mine Workers from doing any of the following

acts

1. Giving legal counsel and advice.

2. Eepresenting its members with respect to Work

men’s Compensation claims and any and all other

claims which they may have under the laws and stat

utes of the State of Illinois.

3. Eendering legal opinions.

4. Employing attorneys on salary or retainer basis

to represent its members with respect to Workmen’s

Compensation claims and any and all other claims

which they may have under the statutes and laws of

Illinois.

5. Practicing law in any form either directly or in

directly.

The Union took an appeal to the Illinois Supreme Court,

whose decision affirmed the holding of the Circuit Court.

I t is from this Illinois Supreme Court opinion that the

United Mine Workers, District 12, have sought a writ of

certiorari in this court which was granted February 27,

1967.

— 11

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

The Illinois Supreme Court has consistently held that

not-for-profit organizations which hire lawyers to repre

sent their members are engaging in the unauthorized prac

tice of law. The question of representation of union mem

bers by preselected attorneys was not new to Illinois when

the Mineworkers suit was instituted. In 1958, the Illinois

Supreme Court in In re Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen,

13 111. 2d 391, 150 N. E. 2d 163, condemned the financial

payback by the attorney to the union out of fees collected,

but recognized the right of the union to recommend to its

members the advisability of obtaining legal advice before

making a settlement, and giving the names of attorneys

who, in its opinion, have the capacity to handle such claims

successfully.

After this decision, the Committee on Unauthorized

Practice of the State Bar, in meetings held with minework

ers’ representatives, urged the union to desist from its

salaried lawyer arrangement and to follow the guidelines

of recommendation of legal counsel as spelled out in the

Illinois Brotherhood case. They refused to change their

programs and, after all reasonable efforts failed, the Illi

nois State Bar Association instituted the present litigation

to enjoin such practice. Repeated efforts, throughout the

proceedings, were made to urge the United Mine Workers

Union to change to the recommendation system. They

continued their refusal.

The type of representation, with the volume of claims

involved, was not conducive to the best interests of the

public. The record does not support their claim that the

plan insured competent and loyal legal counsel for the

individual miner.

The claim of prohibition of attorneys’ fees in compen

sation cases in Illinois is not supported by the statutory

— 12 —

law of the State, but, on the contrary, specific provisions

of the Workmen’s Compensation Act not only permitted

attorneys’ fees, but provide that they shall be regulated

by the Industrial Commission.

The general language of the part of the Labor Manage

ment Relations Act dealing with “ other mutual aid or

protection” does not carry with it the right to usurp the

authority of the Illinois Court to regulate and control the

practice of law. The Congressional declaration of purpose

and policy, as contained in Section 141 of the Act, does

not include the individual rights of the members of the

union, unrelated to the common purpose.

Professional Ethics opinions of the American Bar As

sociation support the position taken by Illinois in this

factual situation.

The injunctive decree was proper in all of its terms

and was necessary for the protection of the public, who

in this case is the individual miner.

Finally, the decision of the Illinois Supreme Court does

not deny the petitioner union any constitutionally pro

tected right, nor does the State decision conflict with any

decision of this Court. The protection of the public and

the assurance of the proper attorney-client relationship

is the sole and only purpose for the existence of a State

unauthorized practice of law committee, and its action

here was necessary to enforce State protected rights of

the public.

There was a compelling State interest that required the

action of the committee and, finally, the ruling of the

Illinois Supreme Court. This was not some vague un

identifiable right that was being protected, but a sub

stantial right of the State to control the practice of law

within its border. There was no invasion of the indi-

— 13 —

vidual miner’s right of freedom of expression and associa

tion. I t was because of its profound duty to the public

that Illinois concerned itself with (1) the preservation of

the integrity of the attorney-client relationship, (2) de

termination that Federal constitutional provisions of free

expression and association are not infringed by the court’s

control of professional conduct and the protection of the

public, and (3) the prevention of substantial commer

cialization of the law profession. The Illinois Supreme

Court is not attempting to regulate conduct involving the

application of a Federal law, such as the Safety Appliance

Act, the Federal Employer’s Liability Act, or the practice

before the United States Patent Office, but the Illinois

decision merely limited its curtailment of the union’s con

duct to State protected rights only.

The decision of the lower court should be affirmed.

— 14 —

ARGUMENT.

The Decision Below Is Clearly Correct.

It is basic to This Court’s consideration of the Brief

of Petitioner’s, United Mine Workers of America, District

12, that it be advised of the long history of Illinois Su

preme Court pronouncements as to what constitutes the

unauthorized practice of law within the State of Illinois.

This court has consistently held that organizations, includ

ing not-for-profit organizations, which hire lawyers to

represent their members are engaging in the unauthorized

practice of law. People ex rel. Courtney v. Association

of Real Estate Taxpayers of Illinois, 354 111. 102, 187

N. E. 823; People ex rel. Chicago Bar Association v. The

Motorists Association of Illinois, 354 111. 595, 188 N. E.

827; People ex rel. Chicago Bar Association v. Chicago

Motor Club, 362 111. 50, 199 N. E. 1.

The Chicago Motor Club case sets forth the position

of Illinois as to the activities of a service organization

when it said on pages 56-57:

“ By way of exception to the findings of the com

missioner, respondent claims there is no admission

in the record that it solicited memberships for the

purpose of performing legal services; that the cor

poration itself performed no legal services; but such

as were in fact performed were by lawyers engaged

by respondent for its members pursuant to authority

received by it from them; that such legal services

were paid for out of dues collected by respondent

from its members as their representative and agent.

It is further contended that respondent is not engaged

in the practice of law within its ordinarily accepted

sense, but that its legal functions are only a part

15

of its many-sided activities as a service organization

whose members have a common interest. However

beneficial its many other purposes and services seem

to be to its members and to the public generally,

we cannot condone the advertisements and solicitations

of memberships by respondent and its admission that

it was only acting as agent in rendering legal services

for its members without abandoning the rules laid

down in several recent cases governing such practices.

While the case of People v. Peoples Stock Yards

Bank, 344 111. 462, is distinguishable from the present

case in many respects, yet the fundamental principle

was there expressed ‘a corporation can neither prac

tice law nor hire lawyers to carry on the business

of practicing law for i t ’ (emphasis ours). When the

Chicago Motor Club offered legal services to its mem

bers with the statement, ‘should you be arrested for

an alleged violation of the Motor Vehicle law, you

may call the legal department, and one of our attor

neys will conduct your defense in court,’ it was

engaging in the business of hiring lawyers to prac

tice law for its members. This we have repeatedly

condemned in Illinois. (People v. Peoples Stock

Yards Bank, supra; People v. Motorists Ass’n, 354

111. 595; People v. Real Estate Taxpayers, 354 id.

102.) Other jurisdictions have reached the same or

similar conclusions in recent cases. (Goodman v.

Motorists Allliance, 29 Ohio N. P. K. 31; In re Morse,

98 Vt. 85, 126 Atl. 550; In re Opinion of the Justices,

194 N. E. (Mass.) 313; Rhode Island Bar Ass’n, 179

Atl. (R. I.) 139 (decided May 9, 1935.) The fact

that respondent was a corporation organized not for

profit docs not vary the rule. People v. Real Estate

Taxpayers, supra.”

Legal services cannot be capitalized for the profit

of laymen, corporate or otherwise, directly or indi

rectly, in this State. In practically every jurisdiction

16

where the issiie has been raised it has been held that

the public welfare demands that legal services should

not be commercialized and that no corporation, asso

ciation or partnership of laymen can contract with

its members to supply them with legal services, as

if that service were a commodity which could be

advertised, bought, sold and delivered (emphasis

ours).

The Illinois Mineworkers Opinion (E. 94-105) and the

Appellee’s brief filed in the Illinois Supreme Court (R.

63-94) fully develop the court-announced concept of un

authorized practice of law in Illinois by unincorporated

associations. This problem is not new nor is it prospective

with the Illinois Court or the organized bar of the State

of Illinois. The Committee on Unauthorized Practice of

the State Bar for many years has considered these prob

lems, including the salaried lawyer arrangement of United

Mine Workers, District 12, and has taken court action

in stopping such practices (R. 77-83).

This question of representation of union members by

elected attorneys was not new to the Illinois Supreme

Court when the mineworkers suit was initiated. In 1958,

the Illinois Supreme Court handed down its opinion in

In re Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, 13 111. 2d 391,

150 N. E. 2d 163. While condemning the financial pay

back by the attorney to the union out of fees collected,

that court readily recognized the right of the union to

recommend to its members generally, and, to injured

members or their survivors in particular, first: the ad

visability of obtaining legal advice before making a set

tlement; and second: the names of attorneys who, in its

opinion, have the capacity to handle such claims success

fully (13 111. 2d 391, 398).

Immediately following this pronouncement by our court,

the Illinois State Bar Association Unauthorized Practice

— 17

of Law Committee, in meetings held with the mineworkers’

representatives, urged that union to desist from its sal-

ai’ied lawyer arrangement and follow the guidelines of

recommendation of legal counsel approved by the Illinois

Court in its Brotherhood case. In 1964, after all reason

able efforts failed, the Bar Association, acting through

its committee, initiated the present litigation. Through

out the course of the litigation, at every appearance before

the judges of the Circuit Court of Sangamon County,

and, even before the Supreme Court, in our brief (R.

72-3, 92) as well as in oral argument, this Bar Associa

tion, through its counsel, offered to dismiss the suit if

the salaried lawyer arrangements were abandoned and

a proper recommendation plan substituted. This the union

was unwilling to do.

The State Bar is interested in seeing that union mem

bers obtain “ competent and loyal legal counsel” (R. 72-3),

but We are not convinced that the plan now in effect

accomplishes such purpose. On the contrary, the record

herein belies such claim. It is axiomatic that not all

claims or suits brought before administrative tribunals

or courts are correctly decided at the lowest level. For

this reason, appellate procedures are an inherent part of

our judicial system. The rulings of the Industrial Com

mission are subject to review in the Circuit Courts of this

State, and, from there, to our Supreme Court (111. Rev.

Stat. 1959, Ch. 48, Sec. 138.19 (1) (2)). The fundamental

duty of an attorney involves undiluted loyalty to the client

whom he serves and whose interest he protects (Illinois

State Bar Association v. United Mine Workers, District

12, 35 111. 20, 112, 219 N. E. 2d 503 (1966)). It follows,

without question, that this duty extends to the maximum

representation of his individual client’s interest. An anal

ysis of the Workmen’s Compensation cases which reached

the Supreme Court of the State of Illinois for a thirty-one

year period (1936-1967) contained in volumes published

- 1 8

by the ofBcial Reporter, discloses that 351 compensation

cases were decided. Of this total, 252 thereof were appeals

initiated by employers, 99 were pursued by employees.

In that number only 11 cases were appealed by the coal

mining companies and 10 by the miner. Of this group of

21 cases, only 5 originated involving United Mine Work

ers, District 12. ̂ Four of those appeals were filed by the

coal mining companies and only one by a miner affiliated

with the Petitioners herein. I t is further significant that

the last appeal by the mineworker was in 1942. During

the above referred to thirty-one year period, the rates of

recovery for specific injury were increased several times

by statute, the last time being in 1963, before this liti

gation commenced. Yet, the salaried lawyer, in the cal

endar year 1964, recovered less on the average than his

predecessor, even though he was practicing before the

Commission when the rates were at a higher level (R.

53-4, 58-60). In the years 1964-66, during the pendency

of this litigation, we find there was a substantial increase

of appeals to the Supreme Court originating from this

Administrative Agency due to the adoption of Illinois ’ new

Judicial Article on January 1, 1964, which made appellate

procedures more simplified and expeditious. Ninety-nine

(99) compensation cases were taken by appeal to that

court, of which seventy-nine (79) were advanced by the

employer and twenty (20) by the employee. Not a single

case involving a United Mine Workers, District 12 mem

ber, either as petitioner or respondent, reached our high

est court in that period. Is this evidence of “ competent

and loyal legal counsel” so vital to the individual interest

of the miner! We cannot believe that this salaried law-

1 Beckemeyer Coal Co. v. Ind. Comm,, 370 111. 113 (1938);

John Florczak v. Ind. Comm., 381 111. 117 (1942); Franklin

County Coal Co. v. Ind. Comm., 398 111. 528 (1948); Chicago,

Wilmington & Franklin Coal Co. v. Ind. Comm. (Sarafin), 399

111. 76 (1948); Chicago, Wilmington & Franklin Coal Co. v. Ind.

Comm. (Matchek), 400 111. 60 (1948).

-- 19

yer arrangement has fully advanced legitimate legal claims

of the mineworker. On the contrary, when considered

with the volume of cases handled by this salaried attorney

per year (R. 54) we cannot help but feel that, in the in

terest of expediting his work load, he most likely has dealt

with the coal mining company’s lawyers on a volume

basis (sometimes called “ wholesaling files” ), and it would

seem a logical conclusion that the individual minework

e r’s injury claim has been compromised at a figure far

below what might have been secured if the mining com

pany lawyer was dealing with independent attorneys. He

becomes no better than the personal injury lawyer-broker

who deals in volume with the insurance company and

trades cases as a package deal, rather than by considering

the injury aspect of each individual file.^

In Illinois, many attorneys are highly competent and

successful practitioners before the Industrial Commission

of the State of Illinois. There is absolutely no shortage of

lawyers who are willing, ready and able to handle Work

men’s Compensation cases of the union members. (The

section on Workmen’s Compensation of the Illinois State

Bar Association has enrolled 969 officers and members.)"-

I t is highly significant that nowhere in this record is there

2 Carlin, Ethics and The Legal Profession (1965); Carlin and

Howard, Legal Representation and Class Justice, 12 U C L A

L. Rev. 381, 386. . . . .

3 Records of the Illinois State Bar Association reveal that of

these 969 members who by their membership in the Section show

their interest in compensation matters, 400 practice in Chicago,

85 in Cook County, exclusive of Chicago. The three counties

surrounding Cook—62; the next eight counties away from Cook

—68; next six counties—47; the next fifteen—83; the next six

teen counties 77; the next 14—45; the next 30, comprising

Southern Illinois below Route 40—46; and the popular seven

counties adjacent to St. Louis, Missouri—56. It is not intended

that this list number only those attorneys who can competently

handle a workmen’s compensation claim, but it is indicative of

the large percentage of the lawyers practicing in Illinois who

are available.

— 20 —

a word of testimony, nor a single affidavit tiled by the

petitioners that any member of the union, for any reason

whatsoever, was unable to find competent, individual at

torneys to handle their claims. If such fact were true,

most certainly the petitioners would have filled the trial

court record with proof thereof, by depositions, or affi

davits to this effect, before asking for a summary decree.

Only if such circumstances existed in Illinois, could our

factual situation be considered to parallel the Button (371

U. S. 415) case. Without it, their hue and cry of prece

dence vanishes.

A. An attorney may charge a fee for services rendered

in handling Workmen’s Compensation Act cases.

The Petitioner, in its brief, would have this court believe

that a principal objective of the Workmen’s Compensation

Act was to assure that no one take anything out of an

award except the injured person or his dependents, if he

was deceased (Pet. brief 36-7). Reliance for this statement

is upon a section of the Statute which prohibits an award

to be assignable or subject to any lien, attachment, or

garnishment. The meaning attached to this section is

extended by Petitioner to exclude an attorney charging a

fee for services rendered in a compensation case. The

cases relied on, however, all refer to depleting the pay

ments of an award because of a lien or charge from an

other source. In quoting from Lasley v. Tazewell Coal Co.,

223 111. App. 462, a 1921 decision, it is significant to note

that the Appellate Court found against an attorney assert

ing a lien against the coal company for his fee after ob

taining an award from the Industrial Commission. This is

apparent by the following language from the opinion:

‘ ‘ There is nothing in the other sections of the Act which

in any way conflicts with the provision referred to,” that

the Appellate Court did not review the entire Act. The

Workmen’s Compensation Act has and does provide for

21

the awarding of attorneys fees (111. Rev. Stat. 1965, Ch. 48,

Sec. 138.16).

The section as to liens referred to by Petitioner was

included in the original Act of 1912, and, it is conceded

that the section on Rules did not contain any reference to

attorneys fees until June 28, 1915, when the following

was added:

“ The Board shall have the power to determine the

reasonableness and fix the amount or any fee or com

pensation charged by any person, for any service per

formed in connection with this Act, or for which pay

ment is to be made under this Act, or rendered in

securing any right under this Act. Hurd, 111. Rev.

Stat., Ch. 48, Sec. 141 (1915). The words ‘including

attorneys, physicians, surgeons and hospitals’ were

added in 1925 immediately following the phrase ‘or

compensation charged by any person.’ ”

As both sections were part of the Workmen’s Compen

sation Act in 1921, and, still appear in that Act, the

Appellate Court, in Lasley were either uninformed or, by

nature of these provisions, merely limited its decision to

a prohibition of enforcing an attorneys lien against the

employer. All attorneys fees are fixed by the Industrial

Commission and are carefully and judiciously controlled.^

I t is common knowledge that the maximum fee allowed

is 20%. However, rarely does the Commission approve

fees of that size and most fees awarded are substantially

4 People ex rel. Chicago Bar Assn. v. Lally, 313 111. 21, 144

N. E. 329 (1924) :

“The administration of the Workmen’s Compensation Act

is put in the hands of the Industrial Commission. It fixes

the amount of compensation to be paid and the amount of

attorneys’ fees or compensation rendered for any service

under the Act. Beneficiaries of the Act are under the pro

tection of the Commission, and they can waive none of the

provisions of the Act in regard to compensation.”

■ 22 -

less. It should also be mentioned that the maximum fee

approved in a death case is 10%.

The law recognized that attorneys fees would and could

he charged and are subject to the review of the Commis

sion, when it in Section 19 (c) of the Act, in part, stated:

“The fees and payment thereof of all attorneys and

physicians for services authorized by the Commission

under this Act, shall, upon request of either the

employer or the employee or the beneficiary affected,

he subject to the review and decision of the Com

mission.” Ch. 48, Sec. 138.19 (c).

The Petitioners claim that the mineworkers opinion in

this instant case conflicts with public policy as expressed

by the Legislature is an exercise in fallacious reasoning.

I t is self evident that the section on liens, attachments

and garnishments cannot be read to contain a prohibition

of attorneys fees for professional services.

B. The Labor-Management Relations Act does not

authorize or have within its purview the union salaried

lawyer arrangement considered by the Illinois Supreme

Court.

The mineworkers, throughout the entire course of this

litigation, have endeavored to place unwarranted sig

nificance upon very general language contained in Section

157 of the Labor Management Relations Act (29 U. S.

C. A., 141-157). The section relied upon, after stating the

right of employees to organize and to collectively bargain

contains what petitioner believes to be an all inclusive

catch-all phrase:

“and to engage in other concerted activities for the

purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid

or protection . . . ”

To this language the union claims authority for it “to

make wise provision in advance for competent and loyal

■ 23 -

legal assistance” in the event of disabling injury or death

arising out of and in the course of member’s employment.

This assumes that because coal mining is hazardous, its

members need free legal service and that its appointment

of one man to handle all its members claims insures com

petent and loyal legal assistance.® The facts and the

records of the Department of Mines & Minerals of the

State of Illinois refute each claim.®

It is common practice among attorneys handling claims

before the Industrial Commission not to accept as final

® “We find nothing to suggest that Congress intended hy the

Railway Labor Act, any more than by the Labor Manage

ment Relations Act (29 U. S. C. A. 141), to overthrow

State regulation of the legal profession and the unauthor

ized practice of law.” In re Brotherhood of Railroad Train

men, 13 111. 2d 391, 395.

29 U. S. C. A., § 141, specifically sets forth the purposes and

policy of the Labor-Management Relations Act. None of the

provisions thereof encompass the right to furnish a salaried

lawyer to handle individual claims of the members.

® The Director of Mines and Minerals of the Department of

Mines and Minerals of the State of Illinois stated in the Illinois

Blue Book, 1963-1964, that the mineral industry in Illinois, of

which the chief mineral mined is coal, exceeds a gross dollar

revenue of $600,000,000 per year. Illinois continued as fourth

ranking coal producing state in the nation, producing more than

11 per cent of all coal. Its value in 1962 was $186.6 million.

In 1965, coal produced had a value of $218,977,345.00 (Illinois

Blue Book, 1965-1966). The State of Illinois is endowed with

the largest known coal reserves in the nation. It is estimated

that 137 billion tons of coal remain in the ground in seams of

minable thickness, which at the present rate would take over

1000 years to exhaust (Illinois Blue Book, 1965-1966). The 1966

Annual Coal, Oil and Gas Report of the Department of Mines

and Minerals, page 16, Table 2, “General Statement with Com

parative Figures, 1962-66”, although showing a decline in the

number of mines operating (from 116 to 84), shows a 15 million

ton increase in coal output, an increase in the number of miners

working from 8774 to 8994, and an increase in average days

worked from 182 to 200 days. Still another statistical chart,

“Labor and Employment—Table 17”, reflects upon petitioner’s

claims. In this chart, it compares fatal and non-fatal accidents

for 38 years. Since 1962, the report shows an average per year

of 430 to 485 fatal and non-fatal accidents.

— 24 —

and unimpeachable the medical reports of the company

doctor, hiach injured employee is submitted for physical

examination and possible treatment to a specialist who is

called upon to give a report as to his condition, often

bases on percentages to aid the Arbitrator on making an

award within the purview of the Statute. By this method,

the lawyer is assured that the employee will present to

the Commission the opinions of others than company

doctors, and advances the rights and, by its very nature,

increase the amount that is to be awarded. This is not

the customary practice of the salaried union counsel. This

is a rarity rather than the ordinary course of procedure

(E. 42).

Because of the volume of claims that this one attorney

must handle (430-485 per year), it is obvious that a thor

ough and conscientious handling would consume all of

his time, and in all probability if studied and presented

on an individual basis, instead of a mass production tech

nique, would probably reduce substantially the number

of claims concluded each year. This volume needs the

undivided attention of the single attorney, yet, we find

Stuart Traynor was a State Senator and had a private

practice other than the mineworkers’ representation (R.

31, 41). I t is well known that a Senator must spend a

minimum of three days, usually Tuesday, Wednesday and

Thursday, in the State Capitol representing his constitu

ents during a legislative session. These sessions last from

7 to 8 months beginning in January. Illinois Blue Book

1963-64, 1964-5, 1965-6. This leaves but 5 months, includ

ing part of the summer, to handle the volume previously

mentioned. His salary per annum as a legislator is Nine

Thousand ($9,000.00) Dollars, almost equal to his pay

from the Union.'^ The Industrial Commission sends arbi

trators to various locations throughout the State on a

T Til. Rev. Stat. 1963, Ch. 63, § 14.

— 25 —

regular basis to hear the cases.® Many of these locations

are in the center of coal mining areas and are removed

from Springfield, the State Capitol, by several hundred

miles (R. 43-45). Thus, the mine workers’ attorney cannot

do justice to his mineworker representation if he is to

adequately represent his constituents. By the same token,

he cannot do justice to his Senatorial position, if he spends

more of his time representing the mineworkers. Look at

the practicalities of the dilemma of Mr. Traynor. Because

the Legislature meets every other year, he must subvert

the interest of the mineworker for at least 7 months of

that period in order to perform his public functions. This

is not evidence of “ competent and loyal legal assistance” .

The Supreme Court of Illinois, having pride in its con

tinuing efforts to protect the public and to regulate the

legal profession, was forced by the factual situation pre

sented to it in the mineworkers case to reach its an

nounced conclusion. To have done otherwise would have

avoided the duty it has as the highest judicial body in

the State and its obligation to protect the public. We

have repeatedly stated that the individual miner is the

public in the eyes of the Illinois Supreme Court, and he

does not lose that identity merely because he is a member

of a union.

C. Petitioners’ arguments run contra to facts as well

as opinions of committees on professional ethics. Its

analogies are wanting in support.

The Union’s explanation that a legal department had

to be started because the “ interests of the members were

being juggled and, even when not, they were required to

pay forty or fifty per cent of the amounts recovered in

damage suits, for attorneys” (R. 14). This cry arose

within one year after the creation of the Industrial Com-

8 111. Rev. Stat. 1963, Ch. 48, § 138.19.

• 26 -

mission and before it had a chance to operate. Strangely

enough, they refer to “ damage suits’’—not injury or

compensation cases. Did the Union have in mind the

establishment of a legal department to handle personal

injury matters unrelated to compensation! Was this

proclamation in 1913 an advertising gimmick to lure

members away from the rival Progressive Miners Union—

a devise to build up its membership! If the Union was

so concerned with the alleged gauging of its members by

attorneys why did it not seek relief through the legisla

ture or the Industrial Commission! We find that on June

29, 1915, the Legislature amended the Statute as follows:

“ The board shall have the power to determine the

reasonableness and fix the amount of any fee or com

pensation charged by any person for any services per

formed in connection with this Act, or for which pay

ment is to be made under this Act, or rendered in

securing any right under this Act.” Hurd, 111. Rev.

Stat. 1915, Sec. 153.

We are unable to find any legislative notes as to the rea

son for this amendment or what group promoted it. How

ever, its purpose is obvious and meets the objection of the

mineworkers as expressed to their membership, if their

concern was, truthfully, compensation claims. Yet, they

chose not to eliminate their salaried lawyer arrangement

and permitted it to continue under circumstances which

disclosed that the individual miner was not receiving ade

quate legal representation.

Petitioner chose to claim that the Illinois decision runs

contra to an informal opinion of the American Bar As

sociation’s Committee on Professional Ethics, and, quotes

the concluding paragraph of No. 469 as authority for their

assertion that the mineworkers plan has the approval of

that committee. Petitioner does not inform this court of

the full opinion (Appendix C) which emphatically reas-

— 27 —

serts previous opinions that “ where a lawyer is selected

and employed, as well as paid, by the employer or associa

tion to represent its employees or members, the employ

ment may well be unethical.” Petitioner, further, refers

to a portion of a letter to the appointed counsel (E. 19-20)

which tells him to turn over a file if the member is repre

sented by other counsel. I t is interesting to note that the

format used to obtain information in no way gives the

member the opportunity to disclose he has other counsel.

The Report to Attorney on Accident form (R. 16-17) does

not contain any words of employment of the Union Law

yer to consent for him to proceed. It is arbitrarily assumed

that the salaried union lawyer will represent him. What

is there in these forms which would lead the salaried law

yer to believe or not to believe that the individual miner

wants or even has secured other counsel? The circum

stance of the Elery Morse incident eminently demonstrates

this void (R. 9). I t would seem, therefore, that this right

to choose counsel is an empty one.

We also find a purported analogy between the lawyer

hired by the insurance company to defend an insured in

an automobile accident case with the mineworkers sal

aried lawyer arrangement. I t is emphasized that in

approving the relationship, a committee on Professional

Ethics of the ABA stated that “ the company and the

insured are virtually one in their common interest and

that the same may be said of the Union and its injured

employee-members.” A reading of Formal Opinion 282

(Appendix D), shows that such equating is not correct.

The context of the remark by the committee has reference

to a community of interest growing out of the contract

of insurance with respect to an action brought by a third

party against the insured within the policy provisions of

defense, investigation and other contractual elements of

control agreed upon between the parties (not the least

of which is that it is the insurance company’s money

— 28 —

that is involved). The Committee found that the lawyer

hired by the insurance company can neither be said to

be “ exploited” by it in violation of Canon 35, nor that

the lawyer was “ lending his services to the unauthorized

practice of law” under Canon 47. I t further held that

no profit inured to the company through the lawyers’

employment and such employment was a necessary in

cident to the main contract of insurance. No part of

Formal Opinion 282 can be stated to support the mine-

worker’s plan which is under attack here. On the con

trary, the record shows, among other things, that the

mineworkers salaried lawyer is and can be “ exploited”

to the detriment of the individual miner and, as such,

is lending his services to the “ unauthorized practice of

law” by a lay intermediary. When considering the type

of services rendered and the volume involved, no other

conclusion can be reached but that the individual miner

is exploited to benefit the union in its claim of better

representation as between it and rival coalminers’ unions.

We have previously shown that the members of the

union are not impoverished or without access to com

petent legal advice and counsel.

D. The injunctive decree was proper and complete for

the purposes intended.

Petitioners object to the scope of the injunctive decree

as being too broad and not supported by the record.

Petitioner’s brief incorrectly paraphrases Items 3 and 4

of said decree. The decree has for its purpose stopping

the United Mine Workers Union from representing its

members in their individual claims through an attorney,

the hiring of such an attorney for that purpose, and the

necessary incidence to that arrangement. I t may seem

somewhat enlarged to enjoin the Union from the (1)

giving of legal counsel and advice, and (2) rendering of

legal opinions, but such facets of the decree are part of

— 29 —

the prohibition of the Union “ practicing law in any form

either directly or indirectly.” Perhaps each of the first

two elements should have been included as a subpara

graph of No. 5. However, from a review of the facts and

the evil sought to be controlled, the decree, in its present

form, is understandable and correct. Certainly, from the

facts of this case, items 3 and 4 must be upheld. The

Illinois Supreme Court recognized the problem presented

to it, and accepted its responsibility in controlling the

legal profession and protecting the public. If it had de

cided that the injunctive decree was too broad in scope,

it would have stricken that part which did not fall

within the purview of its decision. It did not choose to

do so. Therefore, This Supreme Court should not render

a decision on that ground only, and reverse the con

sidered decision of the Illinois Court.

Petitioner cites the case of State of Wyoming v. State

of Colorado, 286 U. S. 494, as authority for the proposi

tion that an injunctive decree cannot be broader or more

extensive than the case warrants. The cited case does not

so hold, but the Supreme Court has held that when a party

brings a judgment or decree to it for review, on that

party rests the burden of showing in what respect the

decree is erroneous. Federal Trade Commission v. Beech

Nut Co., 257 U. S. 441. The United Mine Workers has

failed to sustain the burden placed upon them and have

merely indulged in categorical statements of denial. This

very court has acknowledged that “ it is a salutary prin

ciple that when one has been found to have committed

acts in violation of a law, he may be restrained from

committing other related acts” . NLRB v. Express Pub

lishing Company, 312 U. S. 42. “ Giving legal counsel and

advice” and “ rendering legal opinions” are sufficiently

related to the main subject of unauthorized practice as

being a proper element of the decree that was entered in

this cause.

- - 30 —

If the Court, after approving, in general, the position

taken hy the Illinois Supreme Court, is inclined to limit

the decree, it has the power to strike from any decree re

straints upon the commission of unlawful acts which are

disassociated from those which a defendant has commit

ted. Swift & Company v. U. S., 196 U. S. 375; New York,

New Haven and Hartford Ry. Co. v. Interstate Commerce

Commission, 200 U. S. 361. By this authority, the deci

sion could be limited to approving only such portion as

the Court believes is warranted by the action taken. As

a result, the decree could be limited to enjoining the

United Mine Workers, District 12, from:

a) Representing its members with respect to Work

men’s Compensation claims and any and all other

claims which they may have under the laws and stat

utes of the State of Illinois, and

b) Employing attorneys on salary or retainer basis

to represent its members with respect to Workmen’s

Compensation claims and any and all other claims

which they may have under the statutes and laws of

Illinois.

II.

The Illinois Supreme Court Decision Does Not Deny the

Petitioner Any Constitutionally Protected Right Nor

Does the State Decision Conflict With Any Decision

of This Court.

When we filed the present suit against the mineworkers

in June of 1964, your court had already handed down the

decision in Button (371 U. S. 417, Jan. 14, 1963), and

Virginia Brotherhood (377 U. S. 1, April 20, 1964). As

lawyers, and above all, as members of the Unauthorized

Practice of Law Committee, it behooved us to give care

ful consideration to the intent and meaning of these de

cisions becaxise of their possible effect on matters pending

before us. A searching analysis of these cases, while com

paring them with the factual situation involving the mine-

workers in Illinois, and its purely intrastate character,

convinced us, as attorneys, that our present litigation was

in no way comparable to these decided matters. On the

contrary, upon reviewing these two opinions with our own

Illinois Brotherhood ease, the Bar Association’s course of

action was considered proper and was warranted. As

attorneys, it would be fool-hardy and presumptuous on our

part to arbitrarily disregard the pronouncement of the

highest court of the land for the sole and only purpose

of harassing a union. It cannot be considered harassment,

when you plead with them to adopt a course of conduct

approved by the highest court in the land in Virginia

Brotherhood (377 U. S. 1, at p. 8) (R. 92, 104).

The prime concern of the Bar Association and its Un

authorized Practice of Law Committee is the protection

of the public. In this instance, the public is the individual

mineworker, and he does not lose that status merely be

cause he is a member of a large union. The protection of

the public and the assurance of the proper attorney-client

relationship is the sole and only purpose for the existence

of a state Unauthorized Practice of Law Committee.

Our Illinois Supreme Court carefully considered the

effect and the meaning of the pronouncements in Button

(371 U. S. 415), and Virginia Brotherhood (377 U. S. 1),

as it might be applicable to the mineworkers. The Court

stated:

“ In Virginia Brotherhood Trainmen the Court held

that the First and Fourteenth Amendments protect

the rights of the members through their Brotherhood

to maintain and carry out their plan for advising

workers who are injured to obtain legal advice and

for recommending specific lawyers. Since the part of

the decree to which the Brotherhood objects infringes

those rights, it cannot stand; and to the extent any

82

other part of the decree forbids these activities it too

must fall.” 377 U. S. at p. 8.

“ The Court there (377 U. S. 5, n. 9) specifically

pointed out that the railroad trainmen were objecting

to only those portions of the decree encomposed by

the language of the holding, as the Brotherhood had

denied that it was engaging in practices forbidden

by our decree in In Ee Brotherhood of Railroad Train

men, 13 111. 2d 391. Accordingly, that holding does

not purport to overturn our decision precluding any

financial connection between the Brotherhood and the

counsel selected by it to handle individual member

ship claims. As a consequence, we do not read Vir

ginia Brotherhood Trainmen as constitutionally pro

tecting the conduct we are concerned with here, i. e.,

employment on a salary basis by a labor union of

counsel to represent individual members’ claims be

fore the Industrial Commission. The Circuit Court

decree in question here does not attempt to restrain

the union from advising its members to seek legal

advice or from recommending particular attorneys

thought competent to handle Workmen’s Compensa

tion claims. As related earlier, our decision in In re

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, specifically allows

such conduct.”

“ In N. A. A. C. P. V. Button, the Supreme Court

of the United States held that a system devised by the

N. A. A. C. P. to furnish and recommend attorneys

(who were apparently compensated on a p e r d iem

basis by the organization in connection with each case

handled) to member litigants for the prosecution of

civil rights cases was constitutionally protected by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments. However, the

litigation therein engaged was regarded as a form of

constitutionally protected political expression and

cannot as such be equated with the bodily injury liti

gation with which we are concerned here. Also, it is

to be noted that an apparent dearth of Virginia law

yers willing to handle civil rights litigation was

deemed of some importance by the Supreme Court,

and at least Justice Douglas was influenced by his

conclusion that the State’s attempt to characterize

the N. A. A. C. P. activities as ‘solicitation’ indicated

a legislative purpose to penalize that group because of

desegregation activities. Further, the majority opin

ion there read the decree of the Virginia Supreme

Court of Appeals ‘as prescribing any arrangement by

which prospective litigants are advised to seek the

assistance of particular attorneys’ (371 U. S. at p.

433). Under such construction, the decree was deemed

violative of the First and Fourteenth Amendment

freedoms of speech and expression.”

Comparing the Button facts with the mineworkers, the

Illinois Court rightfully held that Illinois was not at

tempting to prohibit the union from advising its members

to seek the assistance of particular attorneys, and pointed

out that the Bar Association conceded that the minework

ers “ may validly advise their members to seek legal

advice in connection with their claims and may properly

recommend particular attorneys deemed competent to

handle such litigation” (E. 104).

The Illinois Court correctly concluded that the decision

entered by the Circuit Court of Sangamon County was

not violative of the First Amendment guarantees relating

to freedom of association and expression. This State Court

decision referred to the recognition in both Button (371

U. S. 438-40) and Virginia Brotherhood (377 U. S. 8, 10)

cases, of the right of individual states to regulate the

practice of law and those who unauthorizingly practice it

(R. 104-5).

We find in Button that the facts disclosed no compelling

state interest to justify Virginia’s action. To the same

— 34-

eifect is this Court’s opinion in the Virginia Brotherhood

Trainman case (377 U. S. 8). Each decision, then, justi

fied its application of First Amendment protection in

reaching results announced. Illinois is not ignoring its

recognition of the rights so vividly protected in Button

and Virginia Brotherhood Trainmen; specifically the right

of political expression or the right to advise and recom

mend particular attorneys because of their competence in

a particular legal field. On the contrary, Illinois urges

those rights and encourages their proper use for the bene

fit of the Union member in his individual affairs. What

Illinois is concerned about, and in which it has a com

pelling state interest, is the protection of the public in

connection with the practice of law by members of the

profession admitted in its state acting through a laj ̂

intermediary. The maintenance of high professional

standards among those who practice law, the prohibitions

of acts of champerty, barratry and maintenance, the ad

herence to well-founded Canons of Ethics against solicita

tions and intervention by lay intermediaries, as well as

statutory provisions forbidding the unauthorized practice

of law are all factors involving clear and compelling state

interests and have continually received the attention of

Illinois Courts. Illinois, through the efforts of its Bar

Association has repeatedly caused its Supreme Court to

look into arrangements which challenge this protection

of the public, and, as an incident thereto, the profession.

We have referred earlier to the history of this court in

that regard. The Illinois Supreme Court is not blind to

progress or sociological development, as evidenced by its

ruling in the Illinois Brotherhood case. You do not find

it striking down the basic plan fostered by the Brother

hood. I t only restricted its evil. That evil was the

financial connection between the Brotherhood and the

attorneys, and the concern of interference with the indi

vidual attorney-client relationship. I t has done no more

its mineworker decision. I t attacks the salariedin

— 35 —

lawyer relationship for the evil it exposes, and it attempts

to assure to the individual member of the union the un

divided loyalty of his attorney. Neither the Court nor

the Bar Association has put arbitrary road blocks in the

path of the union. They merely direct that its Illinois

Brotherhood and the Virginia Brotherhood Trainmen de

cisions be followed by eliminating that financial connec

tion between union and attorney, and substituting the

practice of selecting a list of qualified and competent at

torneys to recommend to the members for that member to

hire, and for that member to pay for services rendered.

In considering whether Illinois has a “ compelling state

interest” in controlling the practice of law and the pro

tection of the public, the Court rightfully looked into the

potential problems of the future under this plan or any

similar device to circumvent the desired individual at

torney-client relationship. Because the Illinois Supreme

Court is concerned with what might happen in the future,

the union charges it with unnecessary clairvoyance, and

condemns such reasoning. Petitioner ignores, however,

the responsibility of the Illinois Court over the legal pro

fession and its duty to protect the public, incidental

thereto. I t is no answer to say that this plan or any one

like it should be continued because the Court has the

right to correct individual abuses as they are brought to

its attention. Consider if you will, what this means, and

its effect upon the individual. The salaried lawyer han

dles a claim for an individual mineworker member, and,

because he has not fully prepared his case, the mineworker

receives an award considerably less than the maximum he

was entitled to or could have received. Consider further

that this situation, because of the salaried lawyer rela

tionship, does not come to the attention of the Bar until

the appeal time has been exhausted. Certainly, the Bar

and the Court are interested in this case and probably

vdll hold hearings as to the lawyer’s conduct, to deter-

— 36 —

mine whether this was incompetence, or of such a character

to deserve suspension or disbarment. What good is this

control element to the individual whose claim has not

been handled properly? Obviously, he is left without a

remedy unless it is against the lawyer for mal-practice.

The Supreme Court of every state, not only Illinois, must

consider many matters prospectively in order to fulfill its

rule making function. It is because of its profound duty

that Illinois concerned itself with (1) the preservation of

the integrity of the attorney-client relationship, (2) de

termined that Federal Constitutional provisions of free

expression and association are not infringed by that

court’s control of professional conduct and its protection

of the public, and (3) the prevention of substantial com

mercialization of the law profession.

We do not find any constitutional infringement of the

rights of the Illinois mineworkers in the action taken by

the Courts of Illinois to regulate and control the practice

of law within its border. The State of Illinois has a

“ compelling state interest’’ in controlling the standards

of professional conduct, NAAOP v. Button, 371 U. S. 41-5

at 438. The Illinois Supreme Court is not attempting

to regulate conduct involving the application of a Federal

law, such as the Safety Appliance Act, the Federal Em

ployer’s Liability Act, or the practice before the United

States Patent Office, Sperry v. State of Florida, 373 U. S.

379, but the Illinois decision merely limited its curtail

ment of the Union’s conduct to state protected rights only.

III.

A Discussion of Group Legal Services Is Not

Pertinent to the Issues in This Case.

The problem presented by the facts of this case were

of such a nature that any discussion of group legal

services as an answer to the issues raised herein would

— 2.1 —

be improper. The extent of the legal services rendered

by the salaried lawyer employed by United Mine Workers

of America, District 12, made it imperative that the

Illinois Supreme Court reach the decision it rendered. It

was a purely local problem within Illinois, involving a

union and a lawyer, and the proper application of the

prohibitions contained in the Canons of Ethics. It was a

proper exercise of the Court’s power to control the prac

tice of law.