Bill to Amend Code of Alabama 1975

Policy Advocacy

February 12, 1980

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Bill to Amend Code of Alabama 1975, 1980. 60fe0ac8-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d0c20ea7-6ff9-4f1d-9018-6ecec24baff4/bill-to-amend-code-of-alabama-1975. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

2.

3

4

5

b

7

I

9

[0

t1

L2

t3

14

L5

L6

L7

18

19

2A

2L

z2

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

,r,

J'

38

39

40

41

G!80-463:2- 12- 80)

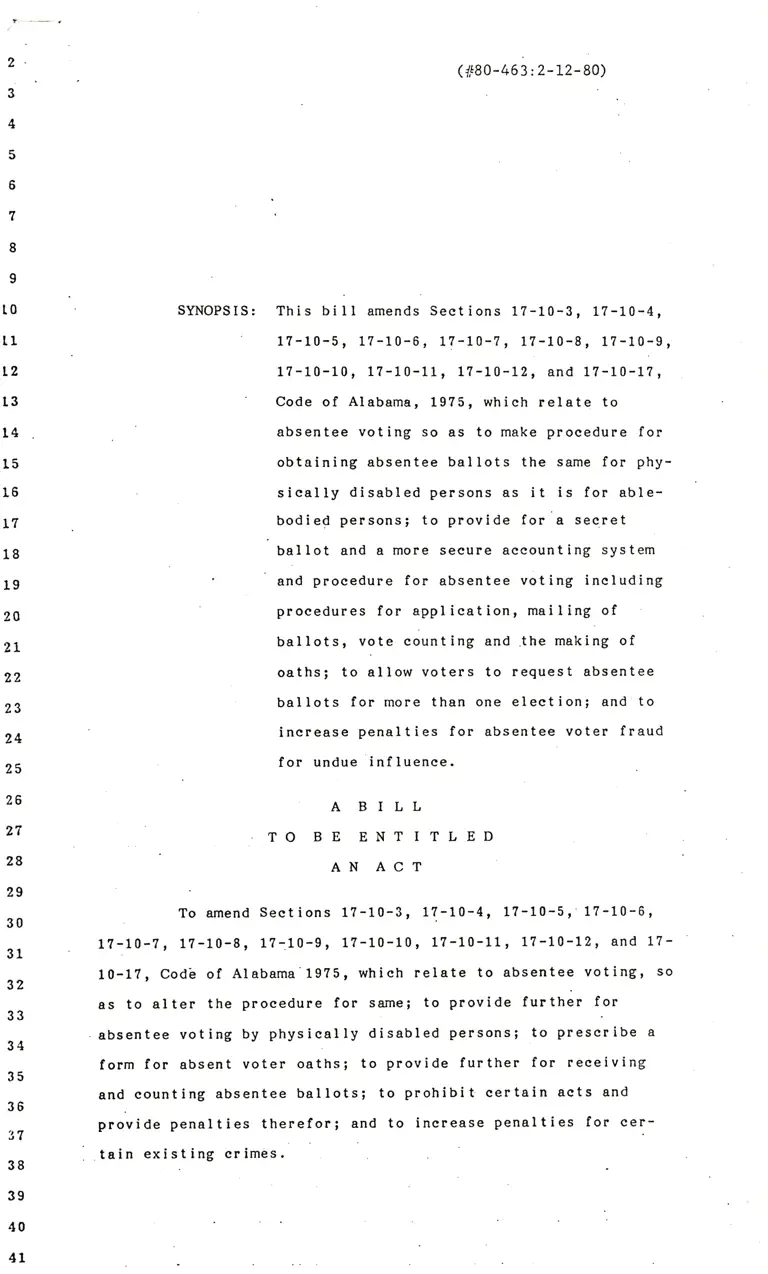

SYNOPSIS: This bi tl amends Sections 1?-10-3, L7-L0-4,

' 17-10-5, 1?-10-6, 17-10-7, 17-10-8, 1?-1r:r,

17-10-10, L7-10-11, 1?-10-12, and 17-10-1?,

' Code of AIabama, 1975, whieh relate to

absentee voting so as to make procedure for

obtaining absentee ballots the same for phy-

sieally disabled persons as it is for able-

bodied personsi to provide for'a sec.ret

ballot and a more seeure aeeounting system

and procedure for absentee voting including

proeedures for application, mailing of

bal lots, vote count ing and .the making of

oaths; to aIIow voters to request absentee

ballots for more than one eleetion; and to

inerease penal t i es for absentee voter fraud

for undue influenee.

TO TLED

To amend Seetions 1?-10-3, 17-10-4r 1?-10-5'' 17-10-6,

1?-10-7, 1?-10-8, 1?-10-9, 1?-10-10, L7-10-11, l7-L0-12, and L7-

10-1?, Codb of Alabama'19?5, whieh relate to absentee voting' so

as to alter the procedure for sarllei to provide further for

absentee voting by physically disabled persons; to pressribe a

form for absent voter oaths; to provide further for reeeiving

and eounting absentee ballots; to prohibit certain aets and

provide penalties therefor; and to increase penalties for cer-

tain exi st ing cr imes.

A BILL

BE ENTT

AN ACT

rt

4

5

6

7

8

I

10

11

L2

13

14

15

16

L7

t8

19

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

4l

BE IT ENACTED BY 'THE' LEGISLATIJRE OF ALABAIWA:

Section 1. Code of Alabama 1g?S, Seetion 1?-10-3 is

amended to read as follows:

xs 17-10-3.

"(a) Any qualif ied eleetor of this state and any per-

son who, but for having moved from the state within the 30 days

inmediately preeeding the eleetion, is a qualif ied elector of

this state who wi Il be unable to vote at his glleg regular

poll ing plaee beeause of his gr_!,el absence f rom the eounty of

his g,LIg1 residenee on the day of any primary, general, special

or municipal eleetionr or.who beeause of any physieal illness or

infirmity whieh prevents h*s attendanee at the porls, whether he

g! gIg is wit.hin or without the county on the day of the elee-

tionr may vote an absentee ballot, provided h" gl_g\e makes

application in writing therefor not more than 60 nor'less than

five days prior to the election in which he or she desires to

vote as authorized in this chapter.

u(b) An applieant for an absentee ballot who is a

member of the armed forees of the United States, ineluding the

Alabama National Guard, the United States naval reserves, the

United States air force reserves and the United States military

reserve.s on active duty training or &n applicant who is the hus-

!gg9-gf wife of any member of the armed forees mey make applica-

tion for an absentee ballot by filling out the federal postcard

appl ication form, authorized and provided for under the provi-

sions of rThe Federal Voting Assistanee Act of 1955rt Public Law

296, Chapter 656, H.R. 4048r approved August 9, 1955, getn

Congress 1st Session. fr.

. Seet ion 2. Code of Alabama 19?5, Seet ion 1?-10-4 is

amended to read as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

l2

13

14

15

16

1?

18

19

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

5 1?-10-4.

I'Such appl-ieation which shall be filed with the Per-

son designated to serve as the absentee eleetion manager, need

not be in any particular form, but it shall eontain sufficient

information to identify the applicant as g-regig!9l99-vo!e! the

pe+*er*he-e*&h3-,Fe-be. It shall inelude the aPplicantrs name,

ogcT-+cxr tg,!.Iggneg address, preeinet-in-whieh-he-*ast-roted,

and the address to whieh he or_she desires the ballot to be

ma i I ed. 9qe_epp[gglf91.trgl-t9gg9s t-a balle!-!ef-BlL-lg1-o!!-

er-9!!er-qsqsgeue4-e!eg!res-!e-qe-IsL9-st!!tlg i xls-9gvlo r -

the receipt of the appl icelten-9f-Ue-eEggglee gleglfgg-geggggt.

Any applicant may have such assistanee in filling out the appli-

eat i on as he g!_gIg des i res, but eaeh

.

appl i cat i on shal I be

manual ly s igned by the apPl ieant and, i f he !Ig-gPPlf9.g.!! s igns

by mark, the name of the witness to his or-her signature must be

signed thereon. Sueh aPPlication may be handed by the applieant

hi*n*el"f to the register or forwarded to hit g1-lgl by United

S t a t es ma i I . *n-*he-eeee-ol-$he-appl*eat*ea-ef-e-qual*$ied-elee-

ter-whe-r+i**-be-w*{h*p-the-eeun*y-en-the-dete-ef the-e}ee$iea7

but- gr+*ble-$e-ge-le-the-pells-en-aeeeuRt-e$-e-phyeiee l -diee bilityy

the-epplieet*en-eh a}}- ha+e-etteehed-the*e&e-e-ee*$l$ie atey-e4$ sed

by-e-*ieeneed-praet*eing-phys*eian- o$- th*s-+ta*e7-eett**y* n$-where

the-epp**eae*-*e-eea$*ned-end-de+e r*b*ng- h*+-e+-het-phys*e el

eead*t*en- end-s+a**n g- thet-he-e+- she-*i**-be-phy+*eatly- trneble-

to-g'o-to-h*g-or-her-po**in6-p'}aee-on-elce*ion-day= Agglfgg!I9!-

f o rms wh l qh-qle-gr i n t ed-C$iegg-aygllgb I e-t o-anLePPlfgg!!-Uy,-

!!g-augg[99-9!9,g!I91-trgleggl-g\a I l -have

pf!4e9-!\Sfgsla I 1-

ggg!-pgla I t i e s-a s

-a

r e-h gr gl!-Pr 9yf9e9-!ef-any-v i olelfgLo f

-

t !tg-

gleelet.'

r,

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

L2

13

14

15

16

L7

18

19

20

ZL

22

23

24

25

26

2T

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

4L

Seetion 3'. Code of Alabama 1g?S, Seetion 1?-10-S, is

amended to read as follows:

"s 1?-10-5.

rrupon receipt of the appl icat ion f or an absentee

ballot, if the applieantrs name appears.on the Iist of qualified

voters in the eleetion to be held opr if the voter makes an

af f idavi t for a ihal lenged vote or-the-ab*entee-e*eet*on-maftagei-

*e sa*isf*ed-the-veter-is-the-persoR-he-elain*s-{e-bey-he the

glggglgg glggllgl-trangggl shalt furnish the absentee b"rl;; ;"

the appl ieant as-regttired-*n-+eet*or-++-+e-S !y_0)_!glwg$-Lgg-

!!-9u-!Er!e9-9!a t e q-trs.Ll-lg egg!-perse!- o r !0-!u-!sngrrs_!!s_

g!ggl!99-9eL-Le!_!e_!Ie_yg! e r _ig_p e r s o n r_ a nq_Uy,-I9_9!h 91_g9 a n s .

rrThe offieial Iist of qualified voters herein

referred to'shaIl be furnished Io the absentee eleetion manager

by the probate judge or other person preparing said list at

least 21 OaVg before the eleetion. The absentee election manager

shall underscore on such list the name of the voter and shall

write inrnediately beside h*s the name of the voter the word

'absenteer. ge llg Uglgggl shall also enrolr the name, residenee

and polling plaee of the applicantr_Ils_gr her_abg9!!gg-!,g}.g!_

guErerr-ag_hereilgllgr_ggsgllqgg, and the date the appl icat ion

was reeeived on a list of absentee voters. The absentee eleetion

manager shall eaeh day enter on said list the narnes, addresses

and poll ing places of each vote.r who h.as that day appl ied f or an

absentee ballot and shall post a copy of the list of applica-

tions reeeived each day on the regular bulletin board or other

public plaee in the county courthouse. Such list shall be main-

tained in the office of the clerk or regi.ster for 60 days after

the election, at which time it shall be destroyea !L-Lgg_Wf!!

!!S_gfg!g!S_igq,gS.: The absentee election manager shatI atso,

before the polls open at any eleetion, cause to be delivered.to

the election offieers of eaeh polling pliee a list showing thg

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

L2

11

t4

15

15

L7

18

19

20

2L

22

2',

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

name and address of every person lvhose name appears on the

official I ist of qual i fied electors for sueh pol I ing plaee

who applied for an absentee ballot in the eleetion. The

name of every such person shall be stricken from the list of

qual i fied electors kept at the pol I ing plaee, and the person

shal I not vote aga i n. ++-sh&H-be-Reee*+ary-for-eaeh

proep eet*+e-absente e-voter-to--raalee-applieat*on-f otr- &n

eb+ea,Fee-ba**et-Sor-eaeh- elee**on-*n-whieh-h e-p*epese*-*o

vo*e-ea--absentee-ba*et- n

Seetion 4. Code of Alabama 19?5, Seetion 1?-10-6, is

amended to read as follows:

t'5 1?-10-6.

"fa) The offieial bal lots for any eleet ion to wh'ich

this chapter pertains shall be in the same form as the offieial

regrrlar ballots for the eleetion, except that they shall have

printed theieon the words, tOfficial Absentee BaIIotr and each

absentee bal lot shal I be numbered eonsecU!!y9!y.-g!.-!,9.I9gq!!9.f.-

pryyfggg, and except that there shall a*so-be-printed-therest-

eae-ef -Ehe-affidaviEs-here*aafEel-Preeefibed; be a detachable

portion of the ballots on which shal1 be printed a unique

', (b ) - sueh -balle e s - shal I -b e- swora - Eo -b e fo re - a -net a:ry

publ i e -er -oEher -e f fi eer- auEherie e d -e e - aeknewl e dge - e aEh s 7 - exeepE

*.4- Ehe- fellewing- eas e 3 "

t' (I) -A -person -eor+f !r+ed -or+ -aeeotlne -of -physieal

dioabiliEy -tso -a -hoePitsa}; -Itulslag -horne ; -Feets -hsrne i -ol3

sanlEatriura-rnay-!n -Pereon-exeeutse -ehe-af f idavie -ort -Ehe

ba}loe -before -Ehe -a6EhoriEy -in -ehalSe -sf -ehe -hospiE'a} ,

rabsentee balLot number' and a space Provi@

name. AlL absentee ballots for each e!-qction sbel!-!-g numbered

consecutively for each counEy. The absentee elec

shall write the unique absentee ballot number offi

mail envelope and the name of the voter in the sp

before he or she for:wards the ballot to the Yo!eg-,-"

1.

2

3

4

5

6

7

I

9

10

1.1

L2

13

L4

15

15

L7

18

19

20

aur e ia t -hene 7 -l e s E -home -or - s an iE ariunr-where -h e- o::

she - i s - een f iaed,-er -b e fere - a -ae E ary- pub I ie;

' "(2) -Aay-applieaaE-for-aa-abseatee-bal1oE-who

is -a-nenber-ef -ehe-arned,- fe::ees -ef -ehe-Uaited

6EaEes; -Ee - enuraerated- ia-S eeEiea-17- 10 - 3; - aad.- is

oa - aeE ive- dutsy - ia- sueh- arrned- fe ?e es - o r - ehe -wi f e

o f - aay - s ueh -merab er - e f - eh e - arraed- fo r e e s ; -who -wi I I

be -away -from-h*s-er-her-tres *deaee-ea-eleeE iea- d.y;

nay -raak e - th e - a f f * davi E - oa - E he -b aI I e E - be for e - aay

o f fieer-auEherised-ee - adraiaister-oaEhs -or-b efore

E h e- eemraaadia g -e f f i e er - e I - e E her - auE he r i ey - ia

eha.rge -e f -ehe - unie - ef -ehe -aaE ional - guar d7 - r ee erveS

or -oEher- eonapenene -s f -Ehe - arned- feree g ;

Seetion 5. Code of Alabama 19?5, Seetion 1?-10-? and

ZL Seetion 17-10-8 is amended to read as follows:

22 n$ 1?-10-?.

26

27

28

23 rrThe f orm of the af f i dav i t ygfflfggllg!-doggtrg!! wh i eh

24 shall be printed-on-absentee-ba*lots used in general, speeial or

25 municipal eleetions shall be substantially as forrows:

rrState of Alabama

' trCounty of ..........

ltBef ore-mer-the--.r*nder**6 ne d-ctrt-h,ee**y 7-pe r+e n a}} y

29 eppea*ed-i'T?'t?=ii?:iir==?a'??-rr???7?-i-i7Tt;Tt=r7-Whe-is-kffgwa-tg,r

30 nade-knowa)-+o-me-aaC-who7-be*ng-*irst-duly-+we*a7-depesee-and

31 eays+-*-anr-a-boaa-f*de-re+i.dent-and-quail-i*ied-e}eetsr

32 efr;;;;r-?ri-i-r?;;'ptecirtet-or-di*triet-*n-===''

33 €euatyT-Alabtma-or-thaF*-was-a-bona-tide-resident-and-qtta****ed

34 elcetor-of-==;;;???r??r;=rptlccinet-or-di-str-ietsunti-I-tny-remova*

35 . therefronron-the-i;????r=;;;rday-of-==:ri-?????;;;;y:}g;r;;-a-date

36 not-more-than-fh*rty-days-betore-the-eleet-lon-dayy-and-bpt-for

37 eueh-remonat-*-sti**-safitfy-*he-Alabama-regi;tration-regu*renrcnts;

38

39

::

2

3

4

5

6

- +-haye-not-heretofore-voted-in-the-e*eet*sn-to-be-held-on

I

I

10

11

L2

13

14

15

16

L7

18

19

20

2L

22

23

24

2S

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

tf:i?????:'t???t= t 1 -'L9;;;7- a nd-* -ara-ent*tled-to-+ete

thereit;-but;-l-w*l*-be-away-f rorthe-es unty-ef -my-r es*d ene e-(sr

*srmer-ret* deneclo r-ttnable-to-g:o-to-the-po*ls-on-sueh-day'r

There*ore--*-have-mctrked-the-f ore g o*ng- abgentee-bal*ot-and-her eby

deelare-the-stme-to-be-my-ba**ot-*n-s{r*d-e}eet*ot?; ;;;;=???t???--

llr-lle-grggryrgn e e r-e 9-gq9gr-(or-eMrd.

that:

1( !.--l-g-a r es i del!-of-.:. . :-:::::. . :.:.-999!!Y

in the State of Alabama.

x(2) Mv olaee of residence in Alabama is:

-:-:--a-L-----

---f sTrEeII-

,A!e9eue --r--lzlP_gooel

l$)--Uy-vot i ns-Eegi ne! ( or-plae9-U!el9-l

yg!e)-ig:

ls

sitl-I-ye!e-!s-Pelg9!- i n- t h e-glegllgs-le snle!-!! i e.-Esll9!-99!:

tains

rI have marked the enelosed abqeElgg_EgUot voluntguly,_

and have read or had read to me and-unQerstand the

EeriEI --GEil:-Jr "

s r I- -l(I-Uv-9e!e-el,-99!r' rg -

:(5 ) --l-str-e!!lt I e9-!g-yg!9-a!-a!se!!ee-9e[e!

9eggggg:

1(0 ) --UY-!glgeh

ole-gsgqel

trCheck_onlg-gng:

fE'omeI------(off TE'AI

I have moved from Alabama less than

thirtv davs orior to the election.

----r---g-L----I wi I I be out of the eountY or the

state on el99!199-dgl:

I am ohvsicallv incaPaeitated and

:-=--E--

wi I l-not ue-gllg-lo vote-in-gglggg

on gJeetfqn_day,.

fl I f urther swear (or af f irm) the!_l_haye_qot vglgg-lgl

4l instruetions aceompanying this baltot and _hqv9_g-gtefu!!y

10

11

L2

13

t4

15

16

l7

18

19

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

2g

30

3l

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

99trP I lgg-urll-ggc !-gg!lg9!lgu:

trMo r eove r I f u r t her-gs9sl-(et-el!lrq)-!!q!-eL!-eL-!!e

rllgtgqlt el-glv91-s,Usve-rq-!$9-ssq eorrect to ue-!ee!-e!-uy,

Elgsleggs= asq-!!s!-!-ssgers!ss g-!!sl Lv-EssgtlgU-sry,r!s false

i n f o rma tlqn-s e-gq-!g-vo!g- i It gggLLy-!.f-eqgelt 99-UeUe!-Ue!-l

shal I 9e-ggtl!y.-o! a-trr gggggelgf-glign lg-Pgltg!'eEle-9v-a f i ne-

!9!-!9-9x e e e d-$ I r90 0

-gn9/et -ge$ I n gtren t -In !!9-999!!y'-iql!- f o f-

!9!-tr9l9-t h a t

-s

i x-tr9!!!!:

--(STilATtiA-o r -frAFE-6f -VoTAFI-

lNe!*--I9ul-$gla t u r e mug!-9e-gf!999n99-qI

' ei ther :-A nglary-Puqlfg-9l-otlgl-glllgef

au t h o r iZeg-lg-aekn o-Il e dge

Uilge1qeg-glgh t e en-yeals -9!-gg9-9l9l99f:--

and subscribed before me this dayrrSworn t o

o f -------L

(or made known) to me

oaths or two

I certifY that the affiant is known

the identical party he claims to be'

1 9____.

to be

----(TTTr6-or-6rrrcrarr-

(signature of official)

--fa,AAFa s s -of -of TTAraIf:=------ oR

n Is t Wi tness ------- ----GTsnaT[FeI

-IPilq!-l'"uEI-------

-IaEEiEssI-

-IeI!rT- --IZiPregEI-

Gls[slsrel----

-Ierit!-!epEl--

( address )

11s9-Er!!es!

-rcIEI: IZiE:s0EEI-

3

4

5

6

7

I

I

10

11

L2

13

14

15

16

t7

18

19

20

2L

22

23

24

25

26

2T

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

3?

38

39

40

4l

11

te)

--IsigqslsE e -or_ ss!E" FIZ

"

g:ssE!!I---

street adAFe3sf

leilyl- -GTE GIPI-

GIgEEIsF{E{EUEFT e e -EI

"

s lls!-AEsse"il.

-TEETEI'

-(6ETr6T-il[ffi6EFF

Seetion 7. Code of Alabama 19?5, Seetion 1?-10-10, is

amended to read as followss

n$ 1?-10-10

ttUpon receipt of the absentee bal lot, the absentee

e I eet i on manager sha I I endorse-on-.Ehe-en+e*ope-over*hie-s*6nature

the-da*e-ard-hour-oFits-reeeipt-by-hinr geg,glg- i !s -r gc e i g!-

thereof on thq absentee I i st_groylggg_1!_[ee!fgg_U-1q-5-g!_tl,fg

eode and shall safely keep the ballot without breaking the seal

of the envelope. On the day of the eleetion, and-during*the-t*rte

the-poiL*r-are-open7 begiigglgg g! !e:qq_Neol, the absentee elec-

tion manager shall deliver the sealed envelopes eontaining

absentee ballots to the eleetion.offieials provided for in see-

tion 1?-10-11, and sueh eleetion officials shall call the name

g f

-e

a c h

.

v o t e r

-c

a s lfg-gl-gq g gE! e e-EgUe!-ltlll-egLL-ga t cle r s-

p r e s en!-gs may,-q e-gr ov i d ed-un9e r -t he-lggg-glAlgleng-gga gEgI!

open eaeh 1etqlq_trei I enveloper-revigU-ltg-ver i f icalfgL9ggg-

Bgg! t o_ggt! i f y_!!e!_ggg!_vo!9t_ i s-en t !! I ed-!o-v o!g-al9 dg,Pgql!

the_Llgil_enveloge_eontaidg-tlg_abggntee--bal lot into g

sealed bal lot box. The absentee bal lots shal I gPgg-!!,9,-g19glgg-

g!_!trg_pgtL!, be counted and otherwise handled in all respects as

tf the said absentee voter were present and voting in person.

As regards municipalities with PoPulations of less than 10,000,

+

2

3

4

5

6

7

I

I

10

11

t2

13

14

15

16

L7

18

19

20

2l

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

3'l

38

39

40

L2

in the ease of municipal elections held at a time different from

a primary or general election, sueh fglglg_trgf!_glyglgPgg-gg1-

lgfglg_lbg UaIIots shall be delivered to the eleetion official

of the preeinet of the respeetive voters.'l

Seetion 8. .Code of Alabama 19?5, Section 1?-10-11

is amended to read as follows:

g 1?-10-11.

"(a) Fol every primary, general, speeial or muni-

cipal'eleeiion, there shall be appointed three managers, two

elerks and a returning off ieer, named and notif ied as are other

eleetion off ieials under the general laws of the,state, who shal

meet, at the regular time of elosing of the election on that

day, in the offiee of the elerk or register for the Purpose of

reeeiving, eounting and returning the ballots cast by absent

voters. The ieturns frorn the absent box shall be made as

required QV law for all other boxes. It shall be unlawful for

any election offieial or other person to publish or make known

to anyone the resul ts of the count of absentee votes' before the

polls close.

n(b) Notwithstanding the provisions of subseetion

(a) of tfris section, in eounties with poPulations of 50'000 or

more, there shall be appointed three managers, two clerks and

one returning officer for. each 200 absentee ballots, or fraction

thereof, east at the elect ion. In sueh eount ies; the apPoint ing

board for the eleetion shall meet four 6ayf before the election,

determine the number of officials to be aPPointed and appoint

and notify them as other eleetion officials arg aPpointed and

notified

(" )_Ary_pe r s gn_o Lelgett" g!ig!

-

a u t h o g!99!-!e

appoint poll watchers under Sect!qr1s 1?-6-8 or 1?-1e-?9-Ug[-Iave

-LS-----\------

s-qtrs!9.Ee!s,!9t-el9s9s!-e!-!!e-gesurn s-o f ' sq !9!!99-qellg!g'

g1!!-ggg!-ffg!.!!.-e!-gt9-eonfelre!-bv lhe glgtgga i d g"g!fe!,g-egg

!v, arv-qlIer-prgvrglglg-o f -g!g!g-!gg.

1.

2

3

4 . 13

b

6 r(e) '!g). This seetion shall not spply to municipal

,l

elections in cities and towns of less than 10r000 inhabitants

8

which are held at a time different from a primary or general

I

election.tt

t0 Section 9. Code of Alabama'19?5, Seetion 1?-1 O-72, is

r.1

amended to read as followss

Lz "s 1?-10-12

13 nNot less than 2t days prior to the holding of any

14 eteetion to which this ehapter pertains, gl-ln !!e-egge-of-g-lg1:

1 s o!!-pttmgrr 9!eg!rgg-!g-un i g!-Urq-glsP!9r-e9l!sllgr-!9!-tr9rg

16 !hag-I-9gy,s a!!gt-!he-!flt!-glfpglL-9lec!!Qn, the officer eharged

t7 with the printing and distribution of the official ballots and

18 eleetion supplies shalI cause to be delivered to the absentee

19 eleetion manager of each county in whieh the election is held or

l

20 to the person designated to serve in his gt-lgt stead a'suf-

2L fieient number of absentee ballots, envelopes and other

22 neeessary supplies. If the absentee eleetion manager is a

23 eandidate gl!!_gppgqflfon in the eleetion, he gg-glg'shall

24 inmediately, up.on reeeipt of such ballots, envelopes and

23 supplies, deliver the same to the person authorized to aet

26 in his or her steadr-ag-grgvided-for in sggtigl !1-!9:!1."

ZT Section 10. Code of Atabama 19?5, Seetion 1?-10-17, is

28 amended to read as follows:

29 r'5 17-10-17.

30 nAny person who willfully changes an absen-

81 tee voter I s bal-lot to the. extent that i t does not ref lect

32 the voterrs true ballot 9t-gEy-Pglg9!-g!,9-gi!!!ur!y-votes-

33 Egle-lEan-once-EX, abgg!!ee-f!,-!he-ggmg-glec!ieg-or-gny-pe-r -

34 geg-Eho-wi I I f gl ly,-veteg-lef-egellgg-voter g!-!g!glf i9!

35 qlq.eqlee Ealle!-egpliget iggs el-vegllicat i9!, g'9ggtr9E!g-99-

36 g,s !9-Io!9 aqqeglee-or-otherwirc-uiolate+-in 'Ig!g!fgg-g!

3,1 this chapter, upon eonvietion, shall be punished

38

39

40

I

3

4

5

L4

6- by hard-*abor-for-the-eoun*y-*or.-not-rnsre-than-*9-mon€h+ IIPr1-

7

:ggltreu rn-!h9-petr!9!!iary-!sr-1e t !9q e-!!es-e!9-E9l-tr9l9-!!e!

I -.- f ive-_yealgr or by a f ine of not less than $500.00 nor not mofe

o" than $g;ee0tee $,291990.00,or by being both fined and senteneed-to

10 - -.--rhard-*abo? lgptiggEgg: It shall be unlawful for any candidate to

11 aid or assist or to tell or suggest the name of any candidate to

t2 any person lvhen he or_she is in the proeess of voting h*s an

13 absentee ballot before the register or other person authorized to

14 administer oaths. Any person who willfully aids any Person

15 unlawfully to vote an absentee ballot, any person who knowingly

16 and unlawfully votes an absentee ballot and any voter who votes

L7 both an absentee and a regular ballot at any eleetion shalt be

18 s imi }arly puni shed. n

19 Seetion lI. This act shall beeome effeetive inme-

.2O diately upon it, passage and approval by the Governor r or uPon i ts

2L otherwise beeoming a law,

22

23

24

25

26

21

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40