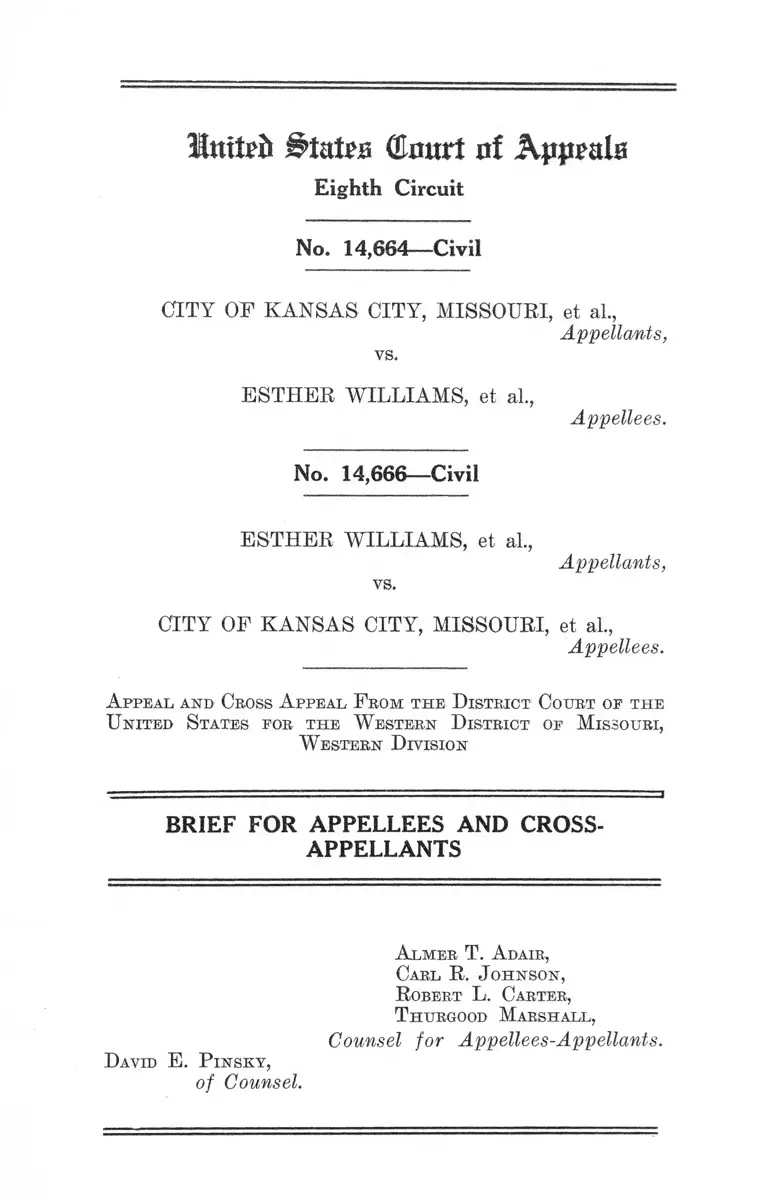

City of Kansas City, Missouri v. WIlliams Brief for Appellees and Cross-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1952

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Kansas City, Missouri v. WIlliams Brief for Appellees and Cross-Appellants, 1952. 83edf596-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d0d70917-5df1-464e-b648-f1c545d6b409/city-of-kansas-city-missouri-v-williams-brief-for-appellees-and-cross-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Inited (Emtrt of App^ala

Eighth Circuit

No. 14,664— Civil

CITY OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

ESTHER WILLIAMS, et al,

Appellees.

No. 14,666— Civil

ESTHER WILLIAMS, et al.,

vs.

Appellants,

CITY OF KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal and Cross A ppeal F rom the D istrict Court op the

U nited States por the W estern District of Missouri,

W estern Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES AND CROSS

APPELLANTS

Almer T. Adair,

Carl R. J ohnson,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Counsel for Appellees-Appellants.

David E. P insky,

of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the C ase ................................................... 1

Points and Authorities ........................................ 3

Argument—No. 14,664 ................................................. 5

I. The State has no power to impose distinctions

among its citizens with respect to the use and

enjoyment of public facilities ......................... 5

II. Where, as here, the facility maintained for the

segregated group is unequal and inferior to

that maintained for all other persons, the con

stitutional mandate of equal protection of the

laws is violated under all recognized theories

of American constitutional law ........................ 7

No. 14,666 ....................................................................... 8

III. The right to maintain a class action under Rule

23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

for the benefit of a large group or class of

persons similarly situated to secure rights

guaranteed under the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment is supported by

the overwhelming weight of au thority ........... 8

Conclusion ..................................................................... 13

Table of Cases

Alton v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 122 F. 2d

992 (C. A. 4th 1940); cert. den. 311 U. S. 693 ......... 4,10

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, 326 U. S. 207 . . . . 3, 5

Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 282 IJ. S. 499 .................. 3, 5

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28 . . . . 3, 6

11

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, Va., 182

F. 2d 531 (C. A. 4th 1950)...................................... 4,10

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 256 ................... 3, 5

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 184 ................... 3, 6

Everglades Drainage League v. Napoleon B. Broward

Dist., 253 Fed. 246 (S. D. Fla. 1918)...................... 4,11

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S, 283 .................................. . 3, 6

Gray v. Board of Trustees, 342 U. S. 517, 518........... 4, 9

Gonzales v. Sheeley, 96 F. Supp. 1004 (Ariz. 1951) .. 4,10

Gramling v. Maxwell, 52 F. 2d 256 (W. D. N. C. 1931) 4,11

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ................ 3, 6

Johnson v. Board of of Trustees of University of Ken

tucky, 83 F. Supp. 707 (E. D. Ky. 1949) ............... 4,10

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216.......... 3, 6

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61 .. 3,5

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769 (S. D. Cal. 1944) 4,10

McCabe v. A. T. & S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151. 4,12

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 3, 6

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell,

294 U. S. 580 .......................................................... 3, 5

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . .4, 5, 7,12

Mitchell v. Wright, 62 F. Supp. 580 (M. D. Ala. 1945),

rev. 154 F. 2d 580 (C. A. 5th 1946) ......................4,12,13

Monk v. City of Birmington, 185 F. 2d 859 (C. A. 5th

1950)........................................................................ 5,10

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ................................ 3, 6

Morris v. Williams, 149 F. 2d 703 (C. A. 8th 1945).. 4, 9

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541 ........................ 3, 6

Nolen v. Riechman, 225 Fed. 812 (W. D. Tenn. 1915) 5,11

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 ......................... 3, 6

PAGE

I l l

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ........................... 4, 7

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 8 8 ___ 3, 6

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1 ................................. 3, 6

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U. S. 5 0 ............................. 3, 6

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 IT. S. 631................ 4, 7

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ......................... 3, 6

Smith v. Allwright, 321IJ. S. 649 .................................. 3, 6

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629 ....................3, 4, 5, 6, 7,12

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334 U. S.

410 ............................................................................. 3, 6

Terry v. Adams, 95 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Tex. 1950),

rev. on other grounds 193 F. 2d 600 (C. A. 5th

1952) ......................................................................... 5,10

Wilson v. Beebe, 99 F. Supp. 418 (Del. 1951)........... 5,10

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 IT. S. 356 ........................... 3, 6

PAGE

Inttefc States OXnurt rtf Kppmlx

Eighth Circuit

— --------------------------------- o ----------- .— _ — —

No. 14,664— Civil

City of K ansas City, Missouri, et al.

Appellants,

v.

E sther W illiams, et al.

Appellees.

No. 14,666—Civil

E sther W illiams, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

City op K ansas City, Missouri, et al.

Appellees.

A ppeal and Cross A ppeal F rom the District Court op the

U nited States for the W estern District of Missouri,

W estern Division

----- ---------------- o----------------------

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES AND CROSS

APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Esther Williams, Lena R. Smith and Joseph N. Moore,

Negro citizens of the United States and of the State of

Missouri, began the action in the court below seeking to

enjoin the City of Kansas City, Missouri, the Board of

Park Commissioners and the Superintendent of Parks of

Kansas City from pursuing a policy, custom and usage

of refusing to admit them, and other Negroes similarly

2

situated to Swope Park Swimming Pool, a public facility,

solely because of their race and color. It was alleged that

their exclusion, being based upon race and color alone,

denied to them the equal protection of the laws as secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment. Suit was brought by

appellees1 as a class action in accordance with Rule

23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on their

own behalf and on behalf of all other Negroes similarly

situated—there being common questions of law and fact

involved affecting the rights of all Negro citizens who

reside in Kansas City, Missouri who are so numerous as

to make it impracticable to bring them all before the court

in a single litigation.

A trial on the merits took place on February 15, 1952

(R. 61 et seq). On April 18, 1952, the court below entered

its memorandum opinion (R. 24-35), findings of fact

(R. 35-37) and conclusions of law (R. 37-44). The court

held that “ plaintiffs may maintain the instant action in

their own behalf, but same cannot be presented as a pure

class action” (R. 37). On May 7, 1952, a final decree was

entered restraining the City, Board of Park Commissioners

and Superintendent of Parks from “ refusing to enter and

make contracts with the plaintiffs for admission to the

Swope Park Pool and from refusing to admit plaintiffs

to said pool and all facilities operated in connection there

with because of their race and color” (R. 46-47). From

this final judgment and decree, an appeal (R. 50) and

cross-appeal (R. 58) were taken.

Appellees submit that the judgment of the court below

should be affirmed except insofar as the court below ruled

that the instant action could not be maintained as a class

suit. With respect to the latter ruling, it is submitted that

the judgment is erroneous and should be reversed.

1 Throughout this brief the term, appellees, will refer to plain

tiffs below and the term appellants will refer to defendants below.

3

The facilities at the Swope Park Swimming Pool main

tained exclusively for white persons and those of the

Parade Park Pool maintained exclusively for Negroes is

accurately described by the court below in its memorandum

opinion (E. 26, 27, 35), and we adopt the court ’s statement

as our counter-statement of facts.

Points and Authorities

A s to No. 14,664

I. The State has no power to impose distinctions among

its citizens with respect to the use and enjoyment of pub

lic facilities.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637;

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629;

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission, 334

U. S. 410;

Asbury Hospital v Cass County, 326 TJ. S. 207;

Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 282 U. S. 499;

Bob Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28;

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265;

Edwards v. California, 314 TJ. S. 160;

Ex Parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283;

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81;

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214;

Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S.

61;

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Bromwell,

294 U. S. 580;

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373;

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541;

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633;

Railway Mail Assn. v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88;

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 TJ. S. 1;

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 TJ. S. 501

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 TJ. S. 535;

Smith v. Allwright, 321 TJ. S. 649 ;

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 TJ. S. 356.

4

II. Where, as here, the facility maintained for the

segregated group is unequal and inferior to that main

tained for all other persons, the constitutional mandate

of equal protection of the laws is violated under all recog

nized theories of American constitutional law.

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337;

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631;

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629.

III. As to No. 14,666

The right to maintain a class action under Rule 23(a)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for the benefit of

a large group or class of persons similarly situated to secure

rights guaranteed under the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment is supported by the over

whelming weight of authority.

Gray v. Board of Trustees, 342 U. S. 517, 518;

Alton v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 182

F 2d 531 (C. A. 4th 1950)

Morris v. Williams, 149 F 2d 703 (C. A. 8th 1945)

Carter v. School Board of Arlington County, Va.,

182 F. 2d 531 (C. A. 4th 1950);

Everglades Drainage League v. Napoleon B.

Broward Dist., 253 Fed. 246 (S. D. Fla. 1918);

Gonzales v. Sheeley, 96 F. Supp. 1004 (Ariz. 1951);

Gramling v. Maxwell, 52 F 2d 256 (W. D. N. C.

1931) ;

Johnson v. Board of Trustees of University of

Kentucky, 83 F. Supp. 707 (E. D. Ky. 1949);

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769 (S. D. Cal.

1944) ;

McCabe v. A. T. & S. F. By. Co., 235 U. S. 151;

Mitchell v. Wright, 62 F. Supp. 580 (M. D. Ala.

1945) , reversed 154 F. 2d 580 (C. A. 5th 1945);

5

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337;

Monk v. City of Birmingham, 185 F 2d 859

(C. A. 5th 1950);

Nolen v. Riechmun, 225 Fed. 812 (W. D. Term.

1915);

Sw-eatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629;

Terry v. Adams, 95 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Tex. 1950)

rev. on other grounds, 193 F 2d 600 (C. A. 5th

1952);

Wilson v. Beebe, 99 F. Supp. 418 (Del. 1951).

ARGUMENT

No. 14,664

I

The State has no power to impose distinctions

among its citizens with respect to the use and enjoy

ment of public facilities.

As to No. 14,664, there can he little question on an

examination of the record, opinion of the court, and

statement in appellants’ brief, heretofore filed, that the

Swope Park Swimming Pool is far superior in physical

appointments and facilities to the Parade Park Pool. It

is our contention that appellants may not exclude appellees

from the Swope Park Swimming Pool solely because of

race.

It is elemental doctrine that governmental classifica

tions must be based upon some real difference having per

tinence to a lawful legislative objective in order to con

form to the requirements of the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson,

282 IJ. S. 499; Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220

U. S. 61; Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, 326 U. S. 207 ;

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell, 294

U. S. 580; Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 256.

6

Classifications and distinctions based upon race and color

alone satisfy neither requirement and are the epitome of

that arbitrariness and caprieiousness constitutionally im

permissible under our system of government. See Skinner

v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535; Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S.

356; Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 184; Nixon v.

Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541. Only as a war measure de

signed to cope with a grave national emergency was even

the federal government permitted to level restrictions

against persons of enemy descent. Hirabayashi v. United

States, 320 U. S. 81; Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633.

This action, “ odious,” Hirabayashi v. United States, supra,

at page 100, and “ suspect,” Korematsu v. United States,

323 U. S. 214, 216, even in times of national peril, must

cease as soon as that danger has passed. Ex Parte Endo,

323 U. S. 283.

Certainly for the past quarter of century, the Supreme

Court of the United States has struck down state imposed

racial restrictions and distinctions in each field of govern

ment activity where question has been raised: selection

for jury service, Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U. S. 50 ; owner

ship and occupancy of real property, Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U. S. 1; gainful employment, Takahashi v. Fish and

Game Commission, 334 U. S. 401; voting, Smith v. All-

wright, 321 U. S. 649; and graduate and professional educa

tion. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637;

and Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629. The commerce clause,

in proscribing the imposition of racial distinctions in in

terstate travel, is a further limitation of state power.

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373. On the other hand, when

the state has sought to protect its citizenry against racial

discrimination and prejudice, its action has been consist

ently upheld, Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S.

88, even though taken in the field of foreign commerce.

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28.

7

Thus, we submit, that under the present status of the

law, even without reg*ard to the quality of facilities afforded,

the state has no power to maintain and make a racial

classification with respect to the use and enjoyment of its

public swimming pool facilities.

II

W here, as here, the facility maintained for the

segregated group is unequal and inferior to that main

tained for all other persons, the constitutional man

date of equal protection of the laws is violated under

all recognized theories of American constitutional law.

Whatever doubt may exist as to the present constitu

tional status of racial segregation where equal physical

facilities are provided, it would be frivolous indeed to argue

that absent equal facilities racial segregation is permis

sible. Plessg v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; Missouri ex rel

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337. The right to equality

of treatment is present and immediate, Svpuel v. Board of

Regents, 332 U. S. 631, and where such equality is denied,

racial barriers to the use and enjoyment of the superior

facilities must be removed at once. Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U. S. 629. Here the record shows clearly that the

Swope Park Swimming Pool maintained exclusively for

white persons is far superior in all respects to the Parade

Park Pool maintained exclusively for Negroes. Under

these circumstances, the policy, custom and usage of pro

hibiting Negroes from using the Swope Park Swimming

Pool cannot continue, and the judgment and decree of the

lower court was correct and should be affirmed.

8

No. 14,666

III

The right to maintain a class action under Rule

2 3 (a ) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for the

benefit o f a large group or class of persons similarly

situated to secure rights guaranteed under the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment is sup

ported by the overwhelming weight o f authority.

This case was brought as a class suit pursuant to Rule

23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which pro

vides as follows:

“ (a) Representation. If persons constituting

a class are so numerous as to make it impracticable

to bring them all before the court, such of them,

one or more, as will fairly insure the adequate

representation of all may, on behalf of all, sue or

be sued, when the character of the right sought to

be enforced for or against the class is

“ (1) joint, or common, or secondary in the

sense that the owner of a primary right refuses

to enforce that right and a member of the class

thereby becomes entitled' to enforce it;

“ (2) several, and the object of the action is

the adjudication of claims which do or may affect

specific property involved in the action; or

“ (3) several, and there is a common question

of law or fact affecting the several rights and a

common relief is sought.”

It was brought not only in behalf of named appellees, but

on behalf of all other Negroes residing in Kansas City,

Missouri, who are affected by the practice, policy, custom

9

and usage of appellants in excluding Negroes from using

the Swope Park Swimming Pool solely because of their

race and color.

The District Court was of the opinion that a class

action could not be maintained because the rights involved

are individual. The overwhelming weight of authority,

however, is to the effect that a class action is a proper

method to secure redress where the state had denied a

large group of its citizenry the equal protection of the law.

In Gray v. Board of Trustees, 342 U. S. 517, action was

brought by Negro plaintiffs who had been denied admission

to the University of Tennessee because of race. The action

was pursued as a class suit on behalf of the named plain

tiffs and all other Negroes similarly situated. In the

course of the argument in the Supreme Court of the United

States, counsel for the University announced that the school

authorities were now ready to admit the plaintiffs. The

Court stopped the argument and subsequently issued a

per curiam opinion saying at 518:

"Since appellants’ request for admission to the

University of Tennessee had been granted and since

there is no suggestion that any person "similarly

situated” will not be afforded similar treatment

* * * the judgments below are vacated and the Dis

trict Court is directed to dismiss the action upon

the ground that the cause is moot.”

This is a clear recognition by the Supreme Court that a

class action was appropriate and that under its decree

other Negroes not named as parties could obtain relief

against discriminatory practices by University officials.

In Morris v. Williams, 149 P 2d 703 (C. A. 8th 1945),

a Negro teacher in Little Rock, Arkansas commenced suit

for herself and on behalf of other Negro teachers and

principals of Little Rock similarly situated. On appeal

10

from a judgment dismissing* the complaint, this Court re

versed and remanded, holding that the record clearly

revealed the existence of a policy, custom and usage of

paying Negro teachers less than white teachers because of

race and color. This Court recognized that the cause was

being litigated as a class suit and impliedly approved the

propriety of this procedure.

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 122 F 2d

992 (C. A. 4th 1940); cert. den. 311 U. S. 693, was among the

first of the teacher-salary cases to be decided at the Court

of Appeals level. It was there recognized that a Negro

attacking state discriminatory action as violative of the

equal protection clause may sue on behalf of himself and

all others similarly situated pursuant to Rule 23a of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Class actions have been allowed in suits involving: the

right to equal school facilities, Carter v. School Board of

Arlington County, Va., 182 F 2d 531 (C. A. 4th. 1950)(

Gonzales v. Sheeley, 96 F. Supp. 1004 (Ariz. 1951); the

constitutionality of racial segregation in public schools,

Wilson v. Beebe, 99 F. Supp. 418 (Del. 1951); a zoning*

ordinance, Monk v. City of Brimingham, 185 F 2d 859

(C. A. 5th 1950), cert, denied, 341 U. S. 940; voting, Terry

v. Adams, 90 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Tex. 1950), reversed on

other grounds, 193 F 2d 600 (C. A. 5th 1952); admission

to graduate school of a state University, Johnson v. Board

of Trustees of University of Kentucky, 83 F. Supp. 707

(E. D. Ky. 1949); use of a public bath house, swimming

pool and playground, Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769

(S. D. Cal 1944).

Even prior to adoption of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure federal courts have generally upheld class suits

where large numbers of citizens have attacked state action

as violative of the Fourteenth Amendment.

11

In Everglades Drainage League v. Napoleon B. Broward

Dist., 253 Fed. 246 (S. D, Fla. 1918), the League and others

brought a bill of equity against the Drainage District and

others to enjoin defendants from collecting a uniform

acreage tax on the ground that the tax was violative of

the Fourteenth Amendment. The League, a voluntary

association claiming more than 1000 members, commenced

the action on behalf of itself and all others similarly situ

ated. On a motion to dismiss the bill, the court held that

the action was properly maintained as a representative

action under Equity Rule 38.2

In Nolen v. Riechman, 225 Fed. 812 (W. D. Tenn. 1915),

a class suit was considered proper where a large group

sought to enjoin enforcement of a state statute regulating

“ jitney” transportation on the ground that it violated the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Similarly, where a large group of peach growers

attacked the constitutionality of a licensing tax statute

as violative of the commerce clause and other provisions

of the Constitution, the propriety of a class suit was upheld.

Gramling v. Maxwell, 52 F. 2nd 256 (W. D. N. C. 1931).

In so holding, the court declared at page 260 :

“ The case is not one, however, involving merely

the right of a single taxpayer. It is a class suit

instituted in behalf of a large number of peach

growers affected by the statute; and we think that

it may be maintained in equity for the purpose of

avoiding the multiplicity of suits which would other

wise result. Whatever may have been the rule for

merly as to the right to maintain a class suit of this

character in the federal courts, we think that, since

the adoption of the 38th Equity Rule (28 U. S. C. A.

2 Equity Rule 38, in effect at the time this case was decided,

reads as follows: ‘‘When the question is one of common or general

interest to many persons constituting a class so numerous as to make

it impracticable to bring them all before the court, one or more may

sue or defend for the whole.

12

723), the right to maintain such a suit cannot be

denied. ’ ’

The District Court in the instant case rested its deci

sion on four cases: McCabe v, A. T. <& S. F. By. Co., 235

U. S. 151; Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337,

351; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ; and Mitchell v.

Wright, 62 F. Supp. 580 (M. D. Ala. 1945).

Neither Gaines nor Sweatt arose in the federal courts

and hence they cannot be considered authority on a ques

tion of federal procedure. Moreover, neither case was

brought as a class action. The assertion in both cases

that the right to the equal protection of the laws is a per

sonal right was meant to define the reach of the Fourteenth

Amendment with respect to the injury suffered and is not

indicative of any negation of the class suit remedy in

these types of cases.

The McCabe case, we submit, offers no support for

the position of the District Court. Plaintiffs in that case,

five Negro citizens of Oklahoma, brought a bill in equity

to restrain several railroad companies from complying

with an Oklahoma statute—which required railroads to

provide separate accommodations for white and Negro

passengers. The action was commenced prior to the effec

tive date of the statute and none of the plaintiffs, there

fore, had suffered any injury. It is not clear from the

opinion whether this action was prosecuted a class suit.

But even if the action was so brought, the case stands

only for the proposition that no one can qualify as a proper

representative of a class seeking redress against an uncon

stitutional enactment, if he has himself suffered no injury.

The Mitchell case stands alone in support of the District

Court. There, action was brought against Alabama regis

tration officials to restrain them from requiring Negro

citizens to submit to tests more rigid than those given

white citizens in order to qualify to vote. The court held

that a class action was improper on the theory that regis

tration was an individual matter and each voter’s qualifica

13

tion must be considered on its own merits. For this and for

failure to exhaust administrative remedies, the court dis

missed the complaint. On appeal, however, judgment was

reversed, 151 F. 2d 580 (C. A. 5th 1946). The opinion of

the Court of Appeals deals exclusively with the question

of administrative remedies but it was held that the action

had been improperly dismissed. Most of the vitality of

this lower court holding, we submit, was destroyed by the

reversal of the Court of Appeals. At any rate, until the

decision in the instant case, Mitchell v. Wright stood alone

in rejecting the propriety of a class suit as a method of

redress available to Negroes in equal protection cases.

Conclusion

The discriminatory action here complained of is the

state’s refusal to permit Negroes to use the Swope Park

Swimming Pool, solely because of their race and their

color. The court found appellants’ practices were uncon

stitutional because the Parade Park Pool was not equal in

physical facilities and recreational value to the Swope Park

Pool. While the named parties are before the court and

have been injured by a specific refusal of admission to

Swope Park, these particular appellees are merely examples

of the discriminatory effect of the state practice. If the

judgment below is allowed to stand in this respect, it will

be an open invitation to any state so inclined to defy the

Fourteenth Amendment until it is literally harassed with

a great number of suits. The appellants can hardly claim

the right to litigate and relitigate the identical issue. A

class suit represents the only effective way whereby a large

group of citizens can avail themselves of the safeguards

of the Fourteenth Amendment. The effect of the judg

ment here is thus to sap the equal protection clause of

14

its effectiveness. It is urged, therefore, that the judgment

of the District Court should he reversed in so far as it held

that a class suit could not be maintained.

Respectfully submitted,

A lmer T. A dair,

220 Lincoln Building,

Kansas City, Missouri,

Carl R. J ohnson,

231 Lincoln Building,

Kansas City, Missouri,

R obert L. Carter,

T htjrgood Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellees-Appellants.

David E. P insky,

of Counsel.

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc ., 41 M urray Street, N . Y., B A rclay 7-0348