Harvey Gantt Interview Transcript

Oral History

March 23, 2023

40 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Interview with Harvey Gantt for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project, conducted by Melody Hunter-Pillion on March 23, 2023 Conducted in collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Copied!

Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project

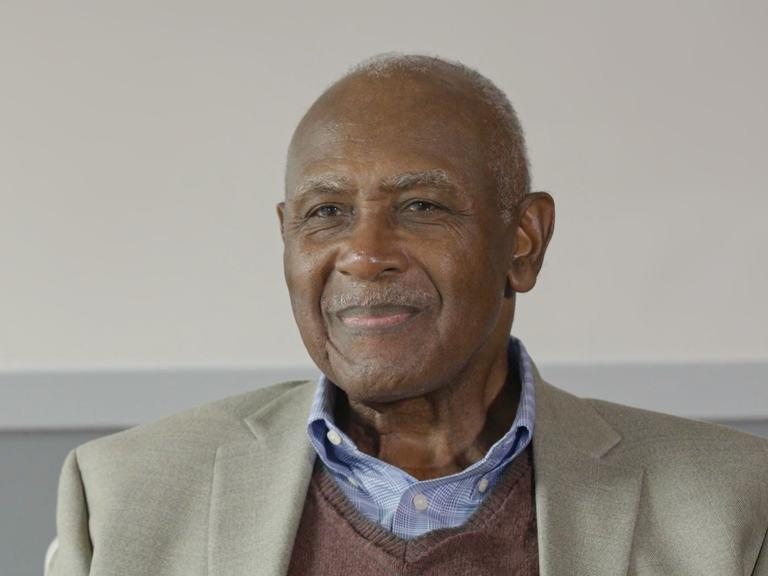

Harvey Gantt

Interviewed by Melody Hunter-Pillion

March 23, 2023

Charlotte, North Carolina

Length: 01:50:01

Conducted in collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill

LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute, NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

2

This transcript has been reviewed by Harvey Gantt, the Southern Oral History Program, and LDF. It

has been lightly edited, in consultation with Harvey Gantt, for readability and clarity. Additions and

corrections appear in both brackets and footnotes. If viewing corresponding video footage, please

refer to this transcript for corrected information.

3

[START OF INTERVIEW]

Melody Hunter-Pillion: Let’s start with your childhood. You grew up in Charleston. Is

that right? In Charleston, South Carolina?

Harvey Gantt: I grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. I was actually born on Yonges

Island, one of the islands surrounding Charleston, and moved to Charleston at a very young age

because my father was working in the Navy shipyards. This was during World War Two. So, I

lived there in a public housing project, specifically designed for people who were working in the

Charleston Naval Shipyard. And so, I tell people jokingly that I grew up in public housing for

the first six years of my life before my father moved us to a “salt of the earth” working class

neighborhood.

MHP: And let me say this before I ask the next question. This is Melody Hunter-Pillion

from the Southern Oral History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It is

March 23rd, 2023. I’m here in Charlotte, North Carolina, with Harvey Gantt in the Harvey B.

Gantt Center to conduct an interview for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project. So, and

again, thank you for being here with us. And Mr. Gantt, I am going to start just by having you

say your name and who you are, very quickly.

HG: I’m Harvey Gantt. I live here in Charlotte, North Carolina. I used to be the mayor of

Charlotte some thirty plus years ago.

MHP: Okay. And so, I want to go back to your beginnings. You talked about growing

up in South Carolina, in Charleston, talked about your father a bit. But your family has like deep

roots in South Carolina. Is that right?

HG: Well, I like to think they were deep roots. But all of my father’s brothers, my

father’s father — my grandfather — were all South Carolinians. And they lived on those

islands. [00:02:06] And following the period of slavery my great, great, grandfather bought

land. And we farmed. We were farmers. I didn’t know much about that era, of course, but I met

4

many of my relatives over the years growing up in Charleston who were Charlestonians [and

islanders]. And we had that very deep Gullah accent that came with people who grew rice on the

plantations during the era of slavery. So, when you say deep roots, yes. You know, we were

there way back then.

MHP: For many generations. Moving forward a bit, do you recall, because you grew up

during the era of segregation, do you recall school desegregation efforts? I'm going to ask a

couple questions here, but, and have any memories of Brown v. Board being decided, so how

did your parents talk about that whole thing and what are your memories of that era, of that

going on?

HG: Brown v. Board of Education was a very, very big topic in my family. You need to

know you can’t just answer that question, because to put that in context, my father, who I greatly

admire for keeping us and my four sisters current with what was going on, he used to drag us to

civil rights meetings at places like Mother Emanuel Church, [and our] home church, Morris

Street Baptist. We heard all the great civil rights leaders back of that time, Roy Wilkins, James

Farmer. All those folks came through on the [NAACP] speaking circuit and he dragged us

[laughs] to many of those events when we were very young. So, on the date of May 17, 1954, I

believe it was, there was a huge headline in the paper that said segregation unconstitutional.

[00:04:20] And we had a great lesson that evening at dinnertime about what all that meant

because Daddy would recount, you know, the Civil Rights Movement. He was an NAACP

member from as far as I can remember. And his charge to us was this is not going to benefit him

so much as it was going to benefit us. And we’ll soon be able to not pass the [white] elementary

school that we passed every day to go to our elementary school, which was segregated. Not have

to go x distance to the new high school, not new high school, but the high school that was

designed for African Americans. He saw a great vision of what was going on. The hero for him,

and I guess for us at the time, were people like Thurgood Marshall, who argued the case in the

5

Supreme Court. So, as a very young kid, we learned a lot about it. And I particularly got very

interested. There was a library about three blocks away from our house called the Dart Hall

Library, and I would come in that library every day following the Brown decision to read all the

periodicals I could. And that’s when I began to realize that my daddy’s dream was probably not

going to be immediate at all. I mean I saw all this opposition to it. And in a certain naïve sense,

you know, as a boy, I thought that when the Supreme Court spoke, everybody just would fall in

line. [00:06:12] We would see barriers come down the next day. And it was clear after a while,

after a lot of reading that with the White Citizens Councils and all this kind of stuff, that there

was going to be a lot of obfuscation and delay associated with that. But Brown had a big

decision, Brown made a big decision point in my life and probably for my whole family, as

would have been the case for a lot of other [Black] families. We thought segregation was over.

MHP: And I’m going to talk more about legal things that continue to need to happen and

the fight that has to continue. But I want to go back to those meetings that your father would

take you and your siblings to, and you name some of the great speakers and civil rights leaders

who would come through. But is there a particular meeting that you went to that is just most

memorable to you or really just made an impression?

HG: You know, I don’t think so. You know, to some extent, you know, remember now, I

was all of eleven years old when Brown happened and going to meetings with him, I was nine or

ten. Daddy was excited. My mother, incidentally, was not all that engaged, although her biggest

concern was, let’s just make sure these kids get a good education and can go to college. And that

to her meant an HBCU someday. But my father was very interested in that and he would try his

best to interpret. The person who stood out for me was Roy Wilkins, only because I thought he

was smart and whatever he said was a little bit engaging about, you know, how we have to

overcome the indignities of second-class citizenship, which was a term we kicked around quite a

bit about what it meant to be second class. [00:08:24] That happened at the dinner table, not at

6

the church when we were listening to those speeches. But we went along and we weren't the

only children that sat sprinkled through those audiences at Morris Street Baptist, Mother

Emanuel, and other churches. There was an engaged adult community. The people who were

least prominent were schoolteachers and people that, well, they were least prominent for

obvious reasons. They could not be associated with the Civil Rights Movement because many of

them would be threatened economically with losing their jobs. So, I didn’t come away feeling

like an intellectual. I came away impressed with how people spoke. Maybe some of the issues

that they spoke to. But I was young.

MHP: Those discussions at the dinner table, as much as you can recall and remember

them, because you said they were discussions, right, that the family had at the dinner table about

what it meant to be a second-class citizen. Can you tell me about some of those discussions and

just your impressions of what that meant as you heard your parents talk to you about it,

particularly your father?

HG: We were going to be, it meant a lot about giving us a sense of hope. There was a lot

of pride in my family and they, my parents, mother and father, always said, you guys are going

to be something. You’re going to get a better education than I did. My daddy was driven by the

fact that he only got to the eighth grade and living in the rural area of Yonges Island, Adams

Run, which was the name of the community. [00:10:20] And in Adams Run, there was a high

school there — Daddy, those that got to go and finished elementary school.1 And he couldn’t go

any further because to go further meant he’d have to go about twenty-seven, twenty-eight miles

to Charleston to school. There was nobody to take him there, bring him home every afternoon.

And so, he went with his father and started farming after finishing eighth grade. And it made an

impression on him when he started having children, all of us, we got this like we got our

1 During transcript review, Mr. Gantt clarified that “there was no high school that Daddy could attend after he had

finished elementary school.”

7

mother’s milk. “You’re all going to get an education, starting with high school and then on.

You’re going to go further. I don’t know how I’m afford to do it, but you will go.” Because he

understood back then that that was the key to how we were going to get to this first-class

citizenship thing. And so, the dinner table discussions were always about, how are we doing in

school? And then he’d lead a discussion on whatever was going on in the world and civil rights.

By 1955, we started hearing about a preacher in Alabama by the name of Martin Luther King.

That was when he was introduced to us as children and King impressed him. It was another

fight. He said there’s a fight in the courtroom, with people like Thurgood [Marshall]. And

apparently there’s going to be more mass protests. And for him, Daddy found that to be an

exciting time. And as kids, we said, well, we’re excited, too, because of what it was going to

mean. This world was going to open up big time. And we could all show our smarts in a bigger

environment, in a bigger pool. So.

MHP: [00:12:26] Mr. Gantt, obviously, you took those conversations to heart. So, here’s

your father who literally doesn’t go to school past eighth grade, but by ninth grade, from what

I’ve read, you have made this decision by ninth grade if this is true, and you tell me, that you

wanted to be an architect. So, when I just think about his life and what your trajectory, right, in

ninth grade, going, okay, I’m going to be an architect. How did your interest develop over the

years into going into architecture? How was it nurtured by the people around you, especially

since it’s such an overwhelmingly white profession even now, but even more so then obviously.

Let’s talk about that. Like, when did you first think this is what I want to do? What motivated

that?

HG: You mentioned the ninth grade. You must have read some article that was done

some time ago that, the actual grade was tenth. But I have to always go back to Ms. L.A. Hill,

who was a fifth-grade teacher of mine. You may have seen this story, too. She reprimanded me

one day for not paying attention to her because I was so busy sketching, just drawing up a storm.

8

Prettiest girl in the class, I could kind of form her face and draw her. And she recognized my

sketching abilities, but she would go and make me pay a price for that. And the price was,

you’re going to have to stay after school until you learn to pay attention. And then when I stayed

after school, she said, I want you to help me put this bulletin board up since you had these

“nervous hands,” and I did have nervous hands. I sketched everywhere I went. So I became the

sort of elementary school artist who could draw. [00:14:22] There was no architecture, I didn’t

even know what an architect was. I think I read an article in Ebony magazine about an architect

on the West Coast whose name I can’t quite recall at the moment and saw that he designed

houses, I remember he designed houses for movie stars.2 And he was African American. But

beyond that, I didn’t think of architecture until I got to tenth grade. And my English teacher

pointed out to me, he said, we all know you draw, but you might want to consider becoming an

architect. And he showed me outside my classroom window, an architect literally working on an

addition to our high school. And so, that’s when I got introduced to it. And found out what

architects did. And they designed buildings and they did this, that, and the other. And I got

curious and I consumed everything I could find about architecture. Unfortunately, I couldn’t go

visit an architect’s office. You know, this is 1957, [19]58, and it’s just unheard of that architects

would be walking in or wanting to do an internship or at least observe what architects do. That’s

just, that was a denial.3 Which is one reason why when I got my own firm, I made sure that

people had all the access they could. But at any rate, to make that long story short, I pursued it

with my guidance counselor. [phone makes a sound, Gantt apologizes and silences it] She was

my guidance counselor. And we started saying, all right, let’s pick out some schools where you

want to go study this if you’re serious about this. [00:16:25] I said, Ms. Broadnax, I don’t want

to do anything but be an architect. Can you imagine designing buildings? Tall buildings, houses,

2 During transcript review, Mr. Gantt noted that the architect he had in mind was Paul Williams.

3 During transcript review, Mr. Gantt clarified that it was “unheard of that a Black kid could go to an architect's office in

Charleston, or apply for an internship, to observe what architects do.”

9

you know, and you got to sketch and do all that. Anyway, she said, yeah, but you got to have

math and physics, so you better take those in high school, too. That will help you go to college.

That didn’t excite me that much, but I did. So one thing led to another. She challenged me when

I made applications to all the African American schools. A&T, Tuskegee, Howard. These were

the HBCUs that had courses in architecture. And one day she just said to me, you’re a smart

young man. And I dare you to try to get into a predominantly white school. And that’s when

they started to have a breakdown on what’s happening in that field. Number one, less than two

percent of all the architects at that time were African Americans. So why not go to the schools

where ninety-eight percent of them come from? Made sense to me. But it also meant that you

were going to be going into the environment that you were not accustomed to. All your life, for

twelve years now, you were going to segregated schools. You’re used to competing with

African American students. This was a new world and that segregation was declared

unconstitutional in 1954 indeed did creep along at less than deliberate speed than the Supreme

Court wanted. But this was a little bit of a new world for me. And so, I accepted her challenge

and I applied to a bunch of schools in the Midwest, maybe a few in the East, got into two or

three of them, chose Iowa State. [00:18:28]

MHP: So, and before we get to the year, I think you went to Ohio State for a year.

HG: Iowa.

MHP: Iowa. Iowa State. Did you anticipate sort of any difficulties when you were

applying to these schools? I mean, beyond just, hey, you have what it takes to get in, but did you

anticipate there would be any difficulties?

HG: You know, when I think back on that, Melody, it’s, I’ve often gone over that. Why

weren’t you concerned that you might not make it there? I mean, that’s what, Ms. Broadnax was

dangling this thing in front of me that effectively said accept the challenge, it is going to be a

challenge. I had some other teachers who said, you know, you only got so far in math, but when

10

these kids [students at white schools] start talking about calculus and having taken it in high

school, how are you going to feel? Somehow, I don’t remember ever being intimidated by that.

It was a challenge. What is life but challenges? Here I am, a sixteen, seventeen-year-old saying,

I want the challenge. You know the biggest concern I had? Leaving the South. My bigger

concern was not where and who I would be going to school with, but it was leaving the place

that I understood the soil, the people, the Gullah accent, Charleston. It was a beautiful city. And

here I was going to a place that I didn’t know anything about. [00:20:19] I wasn’t worried so

much about whether I could make good grades in class. I guess I should have been. But it was

leaving, and one of the most memorable moments I had was getting on the Southern railway

train in Charleston in late August of 1960, telling bye, saying bye to my father and mother and

my sisters. Some of whom were crying because this was the first time that I left home to go to a

place that they had never been. My parents had never been there. My daddy told me later, “I just

prayed that you were going to be all right, boy. Just prayed you were going to be all right.”

Because they did feel comfortable. Even though Daddy told all that stuff about integration, he

felt comfortable if I went to A&T, right in Greensboro, North Carolina. He could come see me,

whenever, you know, and all the great things he wanted to see us do as a race, as a group of

people, that could come later. But not now with his son going away somewhere that none of

them had ever been.

MHP: Talk to me a little bit more about this. This was not one of the questions, but

when we think about this sense of place. And I’m so not surprised that as an architect you would

think about space and place, but just, you know, culturally when there’s a very distinct place,

like how important that is, it’s not just that you’re moving from a region, but a really distinct

culture and place who made you what you are.

HG: Not sure I’m going to get this question and this answer right for you. What I knew

about living in the South was, what I’ve come to recognize is this closeness that comes by being

11

all together in a segregated society. So, I went to a doctor, occasionally I found myself a lawyer.

We were taught, preached to, by preachers who were African American males largely.

[00:22:30] We were nurtured by wonderful teachers of color who understood a lot of what we

were going through. I call it a nurturing environment that allowed me to minimize my second-

class citizenship. The only time you realized it a lot was when you got on the bus to go

downtown, when you left your salt of the earth working class neighborhood on the west side of

Charleston and you got on a bus. Your parents said, straighten up. Be polite. Don’t rock the boat.

In a sense, don’t get in trouble. And remembering what it was like. And this is this culture, the

segregated environment we were in, such that my mother couldn’t try on clothes at a department

store and we were not supposed to be able to drink at the water fountain, and all that business.

Of course, we did it as kids. We did test the water to see whether the white water tasted like the

colored water did. Okay. So that kind of nurturing upbringing, even in the second-class

citizenship status really produced some very proud people. Some very proud people. Then I got

dumped into a different culture altogether. And I found out that the second-class citizens, first of

all, they didn’t even know much about, I had people the first day at Iowa walk up to me and

really stare. [00:24:24] And this is the first time, if you came from Storm Lake, Iowa, or some

little small town where it was all agriculture and was all planting corn. And you went to all

white schools and you had no reason, here you are now at a big university. And here is a Black

guy standing in front of you in line to register. And so, I got lots of stares, probably much more

so than I would have gotten in the South amongst white people who were used to seeing us close

up and personal, but even in the second-class status, of course. And so, people asked questions,

funny questions like, what position do you play on the football team? Because that’s all Iowa

State was, well, I shouldn’t say that. There were some students there like me, but a lot of it was a

different world and I found out that the quote, [inaudible] to the N-word, for them was not Black

people. It was Catholics. It was Jews. Others who were treated in not so kind ways. We were, of

12

course, a part of that group. But they weren’t that familiar with us, they didn’t know us very

well. I did find that the teachers were fine. The people who taught me and built my architectural

career, at the beginning, were very nurturing and very understanding. I did find those calculus

classes tougher, chemistry classes tougher. But in fairness to them, I never felt that they treated

me as an “other.” They were fine. What drove me from Iowa and drove me back home, well at

least a desire to go back home, was the weather.

MHP: I understand that. [laughs]

HG: You understand that? [laughs]

MHP: I know I do. I’m a native North Carolinian, I do.

HG: [00:26:28] So, as I told you in the beginning, what intimidated me more was going

so far away to a distant land. And while there are nice things to say about the Iowa landscape.

Nice to say things to say about people who I didn’t blame as much because they weren’t

exposed to Black folks. The thing that really was negative for me was the harsh winters, the cold

weather. The fact that I just wasn’t accustomed to that, I yearned to go home.

MHP: Before we get to Clemson, we’ll be coming to that very quickly. But I want to

just step back a bit. You talked about those nurturing teachers, those teachers who challenged

you to think beyond, right, anything that you could think before. And so, just thinking of this

context of you learning, being pushed beyond. But then you’re being, you know, an activist also.

So, I’m going to talk about your involvement in a sit-in, and I want you to tell me a bit about

that before we move.

HG: I thought you’d go to that. [laughs]

MHP: What I have here is April 1960, that you helped lead a sit-in at a lunch counter in

Charleston. And I just want to ask about that. The planning for it, who was involved, and what

you anticipated the reaction to be.

13

HG: Okay. Well, first of all, we got involved in that process because of Greensboro, the

Greensboro Four. I had been, of course, you wouldn’t be surprised by this. I had become a

member of the NAACP Youth Council, and a lot of my buddies in high school also became

members of that. So, the youth council that used to sit around and we’d be following the news

and the NAACP meetings were all about what was going on in the rest of the country, really,

and how we were really making progress toward accomplishing integration with all deliberate

speed. [00:28:28] And it was coming clear, being admirers of Martin Luther King and what he

was doing and Rosa Parks and all that stuff. We’d talk about that. And when the Greensboro

Four did these sit-ins with students and literally, we were high school students, but they did

what they were doing. And we saw that spreading across the South and Nashville and other

places where HBCUs were and we said, “We finally found something to do. Maybe we ought to

do this.” And so, we kept talking about it, and the meetings got to be much more interesting

because now we weren’t just talking about what was happening in other places. We were talking

about the possibility of ending segregation at lunch counters in our own hometown and now not

having to pass that water fountain, and not getting a Coke and a hot dog. And we’re going to do

something. This was worthwhile. So, we decided we had to be secretive about it. We couldn’t

dare tell our parents, think about it. This was 1960 and this was February of 1960. I think the sit-

ins occurred in Greensboro on the first of February. So, the first rule was no telling our parents,

because first thing they’re going to say is, “They’re going to arrest you.” It’s going to, in fact, I

know my mother would’ve said that because she talked about other places this was happening,

and “These poor kids are not going to finish school because they are going to end up going to

jail.” And by implication [she would argue], “Harvey Gantt, don’t you ever dare ever think

about that because you’re going to be graduating in May of 1960.” February of 1960 was when

we were making those decisions. So, we couldn’t tell, I couldn’t even tell my daddy, who might

have said, “Yeah, go ahead and do it, but your mama’s not going to like it.” [00:30:29] So, we

14

did, and we trained for it. We got some NAACP people to come in and say, “Look, if you’re

going to do this, these are things you need to understand. Can you take the needling that’s going

to occur? The harsh treatment you’re going to get from white patrons who may not want you

there?” And there was a big story in the paper that happened in one of those Southern cities

where they were pouring ketchup over the sit-ins, the kids who were demonstrating. So, we

actually did some playacting to see how well some of us could stand being insulted, being called

the N-word. You know, just because it, as you got closer to maybe having to do this, it was no

longer an exciting drama that sixteen and seventeen-year-old kids felt like they were doing. This

is getting serious. Staying in jail. So, we started off with thirty some students. We ended up with

about twenty-seven. And to make it a secret, we did lots of interesting things that we thought we

were so tactically great. We weren’t going to have a [noticeable] march to this five and dime, S.

H. Kress. What we were going to do was divide ourselves up into nine kids and approach the

place from different directions. And we did that so that we didn’t create a stir. And then all of a

sudden, we showed up at the counter, sat down. We made an agreement that no one would be

identified as the leader. We would just all be students from Burke High School. [00:32:33]

That’s what we did. Sat there for about six, seven hours, [inaudible]. Got arrested. But you see,

things are never as bad as they may look all the time. We did get the insults from some people

who came, but the police were wonderful. They kind of kept the crowd away. And by the time

we were arrested, it’s a big crowd on the streets waiting for us to come out. We were put into

police cars. I don’t even remember where it was we went, but we weren’t taken to jail. We were

actually taken to a courtroom, a vacant courtroom. I applaud the chief, even to this day, Chief

Kelly, I believe his name was, he just wasn’t going to have this turn into [a big newspaper

story]. And I guess they found a lot of these kids were nice kids in high school, they checked us.

We finally had to give them our names. We sat in the courtroom for a few hours and then at the

door were our parents. They’d worked out getting us out of jail. So, we called ourselves having

15

a soft, nonviolent sit-in. But we were proud of ourselves. And a year later, a couple of years

later, Charleston had the real big demonstrations that really got rid of [public accommodations]

segregation. But we were the first to do it.

MHP: Did that experience, especially going, you know, to jail, not being in jail, right,

but just being taken into the legal system.

HG: Being arrested.

MHP: Being arrested.

HG: Exactly.

MHP: Yeah.

HG: Because that’s how we ended up meeting Matthew Perry.

MHP: Yeah. Did it shape how you thought about the role of the legal system in the Civil

Rights Movement?

HG: Well, first of all, I was glad that there’s something called the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund [laughs] and that [our] parents didn’t have to pay the legal fees to get us out.

[00:34:30] We were actually happy to be identified with being rescued, shall we say, from the

legal system that was unfair from a public policy standpoint. But we had advocates like the

NAACP who we, we were already impressed they were smart, smart lawyers, people who had

turned the Supreme Court around. So, there was never a moment of, I can’t remember at least

some of the guys who talked about this years later, never a moment of gloom and doom that

people might have anticipated would have happened to us, that we’d end up in jail and get a

record. Nothing would happen. Those lunch counters would go on being segregated. So, what

was the point? You just wanted to do some grandstanding before you graduated from high

school? An interesting story for me was when we were picked up by our parents. Some of them,

including my father, almost couldn’t suppress the smile and the — it’s like he stood a little taller.

When we got in the car, of course, my mother laid it on, about “You’re doing such a crazy thing,

16

but I love you anyway Harvey.” And it was like you say, you don’t know about that record.

Daddy was just, “You all right, boy?” You know, it was for him something that he was proud of.

I think mom, I think she was proud too, she just couldn’t express it.

MHP: Well, your safety, I’m sure was her [laughs], and his too, but, right? Perfect segue

to LDF and Clemson, right, because again, here comes LDF, but let’s talk about Clemson, right?

[00:36:35] So, you had gone to Iowa State one year, too cold. You decided to leave and, let’s

talk about your selecting Clemson. When you say, okay, Iowa State is not going to be it. When

you were growing up in South Carolina, how did you think about Clemson? What was, what did

Clemson sort of mean to you? What were your sort of impressions?

HG: It was football. It was football. It was football back then and, but it was a place that

I didn’t really think I’d ever get to, never thought about going. I didn’t even know they had an

architecture school. Ms. Broadnax, my guidance counselor who I’ve mentioned quite a bit in

this thing, you know, she never thought about Clemson, even though she knew that I was a

member of the NAACP Youth Council. She never equated me turning that around or taking

some legal action to go to a school like Clemson. All deliberate speed was working in that very

few of us were activating the effort to integrate schools. So, here’s how Clemson comes into

play. I’m, on a cold day in Iowa, I almost, well, I’ve said this a thousand times, it’s not the first

time I’ve said this. I’m standing in the lobby of the architecture building, reading a list of the

twenty top schools of architecture in the country. And that list was up there because Iowa State

was on that list, but Clemson was even above Iowa State. I said, “Clemson! That’s in South

Carolina. Boy, if I went back to South Carolina, I’d be closer to some of my girlfriends, go to

some of the dances at the HBCUs. [00:38:37] Even if I study. I don’t like this weather. This is a

good place to go.” This was 1961, winter. And as I recall, there were noises being made at the

University of Georgia by Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton [Holmes], I can’t remember his first

name. And so I said, you know what? These other places, other schools in the South were

17

quietly integrating [like] here in North Carolina. I said, I bet nobody has ever applied to

Clemson. We might actually be shocked. This is how naïve I was, we might be shocked if we

just sent a nice, innocent application. So that’s exactly what I did, went to the library, got a

college application for Clemson, sent that thing off, said, let’s see what happens. And I got a

letter back and they were very nice, and they said things like, "Send us your high school

transcripts and a transcript of your first [quarter] grades in Iowa State.” I mean, the semester, I

mean, the quarter, they meant, the quarterly half. Two quarters I attended Iowa State. They were

very, very polite. So, I told the guys I played bridge with in the club room of the dorm, “Told

you that nobody [Black] ever applied to Clemson before. They’re going to let me in.” I was

naïve. [00:40:42] They sent a second letter once they got all the data in. My high school

transcript, Iowa State sent my first two quarter grades. I was proud of those grades and they sent

me back a letter and said, “We noticed that you’re doing very well at Iowa State, please stay

there.” In effect, that’s what it said, very nicely. And that really did tick me off. That really made

me mad. [laughs] And then along the way people said, “I told you so. They’re not going to let

you in. You’re not going to get in.” Five applications later, well, the third application time, that’s

when I was, I was told, “You might want to get some help. You might want LDF to help you.

There is a lawyer that you’ve already met.” And that’s true. I had met Matthew Perry, who came

and spoke to us about what was going to happen in the sit-in case. He spoke to all the

demonstrators at Mother Emanuel Church and in that basement he was telling us all of the

possibilities out there. And people, the tale goes that I met him there, and that’s when he made

the thing, that “One of you is going to go to Clemson one day.” And that really never happened.

That’s a tale that got told. But I get to meet him again by letter because I did tell them what I’d

done, there were two applications that had gone Clemson already, and they turned me down and

what do I do now? [00:42:31] And they [Perry and his associates] said, keep applying. And so,

three more applications later is when we got — but I got introduced. Matthew Perry helped me

18

in terms of framing the letters that I wrote. And, of course, they had all kinds of reasons why

they wouldn’t accept me. The transcript didn’t arrive on time, we’ve got some new requirements.

I can’t even remember all the different, and it seemed like I was beating my head against a stone

wall. So, the summer of 1962, we filed a lawsuit. Matthew Perry, Connie Motley, that whole

brain trust. Willie Smith out of Greenville, Donald Sampson out of Columbia. They all got

excited about this case. And we were checked out to see whether or not we were willing to do it.

And a little-known fact is that there was another student who had come to Iowa State with me

[from Charleston]. After me, I’m sorry. And he enrolled a couple of quarters after I did. And I

told him I was going to go to Clemson, and he says, “Well, I want to go too. I want to go too.”

But he dropped out of that really quickly because his parents felt that there might be some

economic sanctions if he pursued, something like that. So here I was, going alone. And I’ll never

forget my sisters looking at me. And saying, “You’re really going to do this? Really?” And I

said, “I really am.” And then the next day’s paper had headlines: “Charleston Student Sues

Clemson.” [inaudible] And then they started believing. “You are really serious. And you are

crazy.” [laughs]

MHP: [00:44:49] Why was their reaction that? What were their concerns? Did they

have, I mean —

HG: They were concerned about my safety. I had sisters who listened to their mother

who thought, this is not a great idea. Good student. Why don’t you stay there, get your degree?

Come out, earn a living that way. Maybe you come back to the South one day when things have

changed. I think my mother thought “one day” would always be great. But you don’t have to be

the one that brings about “one day.” Go do your thing, you’re smart, blah blah blah. I had

friends in high school who were [mostly] very encouraging. The courtroom scenes in the fall of

1962 were just an eye opener for me. I never saw such smart lawyers in my life because I never

saw Black lawyers operate. And, you know, I go to the lawyers doing things like clearing up a

19

deed or my daddy was trying to get some sort of certification. But that’s how these guys operate.

And they were better than Perry Mason [laughs] on the scene of what they were doing.

Constance Motley was, she was a revelation. I mean, I never thought of women lawyers in that

sense. You know, I mean, today, I don’t think nothing of it. But back then, she was something

and there’s this classic picture taken in Jet magazine with me standing behind her in a break in

the cases in the courtroom action. [00:46:43] And we’re just having a lot of good times. Part of

what I think they were saying to me was, “Morally, this case is on your side and legally it is.

And we know we’re going to win.” They were the most confident people I’d ever seen. They

knew that they were going to win this case, not necessarily with the federal judge who was

hearing it, but most certainly once we appealed it to a [higher court]. And they were absolutely

correct. Absolutely right. And one little tidbit here was in the breaks in the courtroom in

Anderson, they had these times when there was a recess and we’d all go behind the curtain, so to

speak. And Matthew Perry and Constance Motley were having such a good time talking with the

lawyers who were their adversaries. And I could never figure that out. I mean, why are you all

so friendly? I think I remember a comment coming from Donald Sampson, one of the lawyers

from Columbia who had been with LDF there. And they said, “What’s happening, Harvey, is

those lawyers who are being paid a lot of money by the state of South Carolina are simply going

through an act of exerting every administrative remedy and legal remedy available so that they

can present the posture that they tried everything to keep the schools from being integrated.”

How cynical that was to me. I mean, come on, now. [00:48:43] And then we get in front of the

curtain and back into the courtroom, they were at loggerheads with each other, you know, but

they all knew what the result was going to be.

MHP: You just talked about how brilliant Matthew Perry, Constance Baker Motley, the

other attorneys were, and well-prepared. They had this strategy going. Can you talk to me about

20

like that? Like their strategies as much as you can? Did you have a role in the strategy at all?

What was your role in all this?

HG: Well, I had brief time on the witness stand, I had to answer some basic ABC

questions like, “Are you interested in architecture?” or some crazy thing like that. I wasn’t a part

of the head-to-head stuff that was going on. I don’t even know if I would have understood all of

what they were trying to do, establishing the presence of the registrar at the school when I tried

to go and do a personal interview and why they needed this. Frankly, I wasn’t that interested.

You know, I was there at times, but other times I was reading the papers and seeing how they

were covering the story. And getting used to, remember now I was almost twenty years old. Still

a kid, in a sense. Still a little bit naïve. But recognizing that this was going to happen. But no,

when Constance Baker Motley would dip her head over and they were getting together with this

next witness. What they were trying to get out of the next witness, or what they needed to have

that witness say, that didn’t interest me that much. It really didn’t.

MHP: Can you tell me any more about Constance Motley, as you describe what she’s

like and the confidence that she had, that Perry had too, but anything else that you just

remember about her?

HG: [00:50:53] Well. At first, she did not impress me as the kind of person you wanted

to kibitz around with because she seemed to be so serious. And her stature, her commanding

presence, I would say, is kind of awe-inspiring in a way, you know. You know, she was this

important New York lawyer who had done terrific things. She was the lawyer for James

Meredith. She was the one that carried that case. And so, the case in Georgia and ultimately the

case in Alabama. She was looked up to by the other lawyers in South Carolina, even though

Matthew Perry carried a lot of the load of questioning and cross-examination, it was, I always

got the impression she was the lead team lawyer in this case. And, you know, we didn’t, even

though that picture in Jet shows us laughing and going on, I never probed her to find out, you

21

know, who Mr. Motley was or, but that just didn’t come across. The moment was just too big to

get too personal with her. You know. Small talk was not my thing.

MHP: Right. Was there ever a point going through all this, the guardian of the answer,

going through all this, was there ever a point where you thought, this is not worth all this to get

into Clemson?

HG: Not a moment. Not a moment. I was already seeing myself on that campus.

[00:52:43] I had started to take their newspaper to gauge the fervor of the student opposition, to

gauge the general student comments. And somebody had started to send me The Tiger, which is

still to this day, their newspaper. So, I got a copy of The Tiger every day. It was a daily paper.

And I got to know the editor of The Tiger before it was over. And then we both moved to

Charlotte, and he started working at Bank of America, I was running the architectural firm. But

my point is, never did I ever think I was not going to get there because in gleaning through the

newspapers, most of the students were going to be indifferent to it. That’s usually the way that it

is. There is that big old middle that doesn’t give a damn. Doesn’t care. Yeah, you might have the

right-leaning. There were a group of students who I believe, reading those papers. There were

huge numbers of letters to the editor that came from the students. And of course, topic A was,

“What’s going to happen when the school gets integrated?” There was the sense that this crowd,

this student body knew it was going to happen. Maybe they understood the charade that was

going on better than the general public did. So all of that was encouraging to me. That once I got

there, there was a crowd that said, “We’re going to ostracize him. Don’t talk to him. Don’t speak

to him.” And I thought I could survive that. I could survive that.

MHP: [00:54:41] Definitely a different reception than say what happened in Mississippi

with James Meredith.

HG: Well, that’s because, I told James Meredith well before he passed on, we would

meet occasionally in New York, some of it was LDF stuff, that I’m thankful that he made my

22

integration a peaceful one. He didn’t quite understand what I was saying but I said, what

happened in Mississippi was not likely to happen again in the South. And Meredith went in, in

the fall of [19]62. I went in in the winter of [19]63. And the Mississippi incident was so similar

a moment in this whole struggle to integrate schools, National Guard, people being killed, all

kinds of necessarily bad, bad publicity, that the president of Clemson, R.C. Edwards, and the

Governor of South Carolina, Ernest Hollings, at that point when the trials were going on and

then the new governor, Russell, when he came in, had all agreed, even the General Assembly,

that we were not going to have what happened in Mississippi. And Edwards put out a few days

before my actual entrance, [a directive that] any student, any student that got out of line was

going to be sent home, no questions asked. Any student who confronted me or did anything,

they were going to be sent home. And he was serious and the students were serious. I often tell

people that the only epithets I ever heard in that whole ordeal was the ones hollered from the top

of a high rise dormitory down to me if I was walking across the campus alone. They would

simply say something like, “N, go home. [00:56:50] You know, go home. You don’t belong

here.” But other than that. Nothing, in fact, we played a game. I got to know the students in the

architecture school well. And we would walk back and forth to our dorms. Nice straight line

shot, where I was living and where the architecture school was. And we said, let’s play a prank.

One day we decided to play this prank. Let’s have you confronted by a bunch of angry white

students and try to pick a fight with you and let’s see what happens. We’re trying to figure out

how much protection I had because people suspected that there were folks around who looked

like students that really weren’t. And they were right. We faked this fight and out of nowhere all

these people showed up and said [laughs], “Anything we can help you with?” And we all

laughed about it.

23

MHP: Did you ever have a conversation with the university president, Edwards, because

obviously he had said, oh, no, it’s not about race. But then calms the waters when you are, you

know, admitted and you’re there. Did you ever speak one-on-one to him?

HG: Yes, we did. Yes. We spoke almost immediately after I got there. And then we

spoke again a couple of weeks later when he was very concerned for my safety. I was going to

this dance. One of the things I discovered was that as segregated as that institution had been,

Brook Benton, an R&B star back then, was coming to the campus for a dance, which was

shockingly a surprise to me. I said, Brook Benton on a formally segregated institution, a Black

R&B star? [00:58:50] I was learning something about the culture of southern schools is that they

didn’t let the students come in, but the entertainers were very popular. But this was going to be a

dance. And word got out that I was going to this dance. Up to that point, I had pretty much gone

to class, gone to the dining hall, back to my room. Got to know a few of the students in the hall

with me. That was basically my social circle. But I said, I’m going to do that. The other thing I

was going to do was to go to a football game whenever one occurred. And the reason was, hey,

if I’m a student here, I got to become a real student. The president then called me and we had

this nice heart-to-heart talk. And he suggested that I not go because there’d be some opportunity

for some crazy devil to approach me. If you got up and danced with a co-ed, that could be a

trigger for something bad. And I don’t know where I got it from, but the gumption was, “Mr.

President, I really respect all you’ve done, but I think I’m going to go to the dance.”

MHP: You went to the dance?

HG: Yes.

MHP: Did you dance?

HG: Not really. [laughs]

MHP: But you went.

24

HG: I got called backstage by Brook Benton, and people thought that was terrific. He

wanted to talk to me, but no, I basically just went and observed. Maybe that was the kind of

deferential way of maybe listening to the president but the notion of saying, no I couldn’t do

that, and we’d never had any trouble before, except when the March on Washington occurred in

the summer of 1963. [01:00:46] We had another discussion, and he basically wanted to, because

when I got to Clemson in January, I went to school year-round, every session. I wanted to make

sure I graduated in [19]65. So, I took three years in two years. I just went to school, never quit

going. And so that summer I was there in school, he said, “Are you taking time off to go to

Washington, D.C., like I hear all these people are?” And I said, “Sir, I can’t do that. I’m going to

have to watch that on television.” So I didn’t go.

MHP: Well, you are soon joined by your wife. Well, the young lady who would become

your wife, was the second Black student to enroll at Clemson. So, just can you talk about

meeting her? Just sort of also about, I think you both were LDF scholarship recipients? Talk

about that scholarship, what it enabled both of you to do, what it meant to you, but yeah.

HG: Well, first of all, the LDF scholarship, I didn’t find out about the scholarship until I

actually was enrolled. For some reason, we just assumed we would have to pay the normal fees.

And what I didn’t share with you was one of the things that happened at Iowa State was that I

got a grant from the state of South Carolina every semester that made up the difference between

what an in-state student had to pay if Iowa State was charging out-of-state fees, I got those out

of state fees paid by the state of South Carolina, which was one of the reasons they gave for not

accepting me at Clemson. “We noticed that you’re getting scholarship money from the state of

South Carolina, so stay where you are.” [01:02:47] When I went to Clemson, we said, well, now

we’re in-state students. We will have to pay the normal fees, and I’m not sure, Melody, how I

got the notice that, or what happened, because I got mine before Cindy got hers. But they said

LDF, I think it was the Herbert Lehman Scholarship, that your costs to go to Clemson are

25

covered. You know who I was happiest for? My father and mother. It seemed like a kind of

reward that they were going to get, their kid went to Clemson, and they didn’t have to pay a

dime, because of some generous people in New York that had paid the legal fees for the firm,

for the suit. And also paid the scholarship. And then Cindy got the same thing to happen to her.

But back to meeting her. Or. I heard about her. I had, the story is, and she says she went to that

meeting. She never remembered shaking my hand or doing any of that, so that could be true. I

was traveling the state as this famous college student who had integrated Clemson in the spring

of 1963. Met lots of high school students who were introduced to me and I was saying, of course

they wanted to know what it was like being the only student there with all those students, other

[white] students. And so, I was telling that story and the South Carolina Human Relations

Council was sponsoring these things. Cindy came to one of the Columbia meetings. I didn’t

know her from Adam [inaudible], I really didn’t, and we didn’t shake hands. [01:04:50] In the

middle of one of my summer school sessions, a guy came over to me and showed me a little tiny

article that said, “Clemson accepts second African American student”, a Negro student this is,

that they called us back then. I didn’t pay too much attention, because I, in a way, I told her

later, I was a little disappointed. I thought maybe there’d be ten, eleven, or twelve students, you

know, that were going to come. One single student. So, bottom line. And [later] there was a kid

from Columbia, Larry Nazry, who was another male student, so she was the first [woman] to

come. And so, one of my architectural buddies said, well, at least this is a woman. A strange

comment. Anyway, when she got there, I tried to be her friend, in fact, I was doing rehearsing.

How am I going to show her this campus when I’ve only been here one semester and two

summer sessions? But I’ll show her around and try to make her comfortable. And that’s what I

did. For about two months. [laughs] She was cute. [laughs] She was very nice. And I guess the

rest is history.

26

MHP: Was it also just some comfort knowing there was someone else there who was

like you in some ways, like can you just talk to me about what that meant, or maybe it didn’t

mean anything?

HG: Well, outside of the architecture students, I always ate lunch alone. When Cindy

got there, it was very comforting to have arranged to go to dinner together. Maybe not always

breakfast because our classes, conflicts occurred. [01:06:52] And we got to know some of the

people who took care of us, the janitors, and they would invite us to the church in the Clemson

Black community. And by that time, three of us would all go, but we stuck it out and continued

to do it. There was a comfort level and people in Seneca, South Carolina, who absolutely loved

her. And they, you know, I was the history maker so for some reason. I guess that’s what a

woman does. She softened the edges of whatever was happening. So, she was wonderful. I

married her. We dated. We went fishing together. We did lots of crazy things.

MHP: Did you stay in touch over the, while you were at Clemson matriculating, and

then afterwards, did you stay in touch with those LDF, those Legal Defense Fund attorneys?

HG: Well, Matthew Perry, I certainly stayed in touch with all the way through. We

appeared many times around South Carolina together. He sometimes complained that he had

done a lot of other things, but the only thing that they always mentioned was he was the lead

attorney for Harvey Gantt going to Clemson. Yes, we did stay in touch. And I got to know his

family very well. Hallie Perry and their son. Got to know Willie Smith. Used to eat dinner with

him all the time. That’s in Greenville because he was near to Clemson. Donald Sampson’s

probably the one I didn’t get to know as well. But yes, we stayed in touch. Connie Motley, not

so much, because she was in New York, and then I just read of all the wonderful things that

were happening to her, all the awards she was getting, and she was very respected and became a

judge. [01:08:58] And later on, after my career in politics, I met her son and he became a good

friend of ours and friend of my campaign manager, but yeah, I did stay in touch, and we went to

27

LDF dinners in New York. And some of the pioneers, we’d all get to meet. That’s how I met

James Meredith and Vivian Malone and a few of those others.

MHP: You had a chance to get to know former LDF President and Director-Counsel

Julius Chambers. Can you just talk about, you know, what he was like? Your impressions of

him, how you knew him? Tell us a little bit about that.

HG: Julius Chambers was a good friend of mine. And I think we actually met while he

was interning. We never could clear that up. Someone asked us, when did we first meet? It is,

really, the real first meeting was in his office. In Charlotte, right about where the Hornets have

their big coliseum now. He had a little second story office, about three or four rooms, very

unbefitting of the distinguished attorney that he became, just tiny cramped little space. I went to

see him because he was the attorney that was filing these lawsuits in Charlotte when I first got

there. [01:11:01] And that’s when he reminded me that we met at an LDF function prior to me

getting to meet him as a practicing attorney. He was a great lawyer. He was a brilliant man. I

had the benefit, I really, when I think about, I had the benefit of developing a very positive

impression of the legal profession. And that actually came, Melody, from the attorneys that I

encountered, I used to hear people talk about dishonest lawyers and shysters. That was not my

impression. There were some serious people out there changing the nature of this country, and

they were determined and hardworking people. And here was Chambers, a few years older than

me. I don’t know if you know him or knew him. Short in stature, understated, spoke in a very

low-key manner. You never would have gotten the impression that he was as brilliant as he was.

And as we, when we met, I was an intern in an architectural firm here in Charlotte. And we

lived in the same neighborhood. Right around the corner from each other. So, we’d play bid

whist together. And he’d tell me about these wonderful — not wonderful, scary — cases in

eastern North Carolina and central North Carolina, where he was going before judges who were

hostile. This little guy was just stirring up the legal profession in North Carolina. [01:13:03]

28

And I kept saying, “You’re the Matthew Perry of North Carolina”, and we’d joke and kid about

that kind of thing. He was a good friend and to watch him in the courtroom. I sat in on one

session one day at lunchtime when he was arguing the Swann case, because that was, everybody

was looking at that case. Quite frankly, I came away bored [laughs] because it wasn’t quite as

exciting as my case in Anderson, South Carolina, years earlier. But he was getting into some

details and that judge was listening and you know the judge listened because he ruled in Julius’s

favor. But he was a wonderful guy. Just a wonderful guy, as I said, all those LDF guys were.

And I’m not saying this because I’m talking to you about LDF. I mean, that is the real

impression that I got out of the legal profession from the wonderful attorneys that I met who

took their profession seriously and took the Constitution seriously. There are still people today

that are fighting that way that I admire.

MHP: The two of you, though, never worked, had a chance to work together in any

capacity though? No?

HG: I was an architect. We did work with him when we designed some buildings on the

campus at NCCU when he, his career went, you know, Legal Defense, General Counsel and

leader, and then surprisingly, back to North Carolina as the Chancellor of North Carolina

Central. [01:15:03] And so, we had a couple of occasions to work together on some buildings on

that campus. But what was interesting is when we started to do that, he recalled, when we first

were much younger men and I added on to his house [laughs] and designed his brother

Kenneth’s house in River Hills in the Charlotte area. So, Julius and I, we laughed about that

because these are million-dollar buildings now, and we were laughing about keeping within the

budget of a few thousand dollars for a family room that we designed and ultimately had a lot of

fun in.

MHP: I’m going to wrap up with the last two questions. If we have more time, I’ll put in

a bit more. But I definitely want to get to these. And one will be definitely about your career in

29

architecture and just sort of how you see architecture as a way to do your own work, right, in the

public realm as far as making spaces more accessible to everybody. Inviting everybody in some

ways. But I want to ask you about the, oh yes, thank you. Yeah, yeah, when you ran for Senate

against Jesse Helms. So that was [19]90 and [19]96, if I have this right. The races, of course,

drew a lot of national attention, in particular because of Senator Helms’s behavior. I just

wonder, can you talk about what led you to consider running for Senate and what it was like

being part of a race or a campaign, a race that was so contentious? And where, in particular,

where Mr. Helms definitely made a lot of race-based appeals to North Carolina voters.

HG: I can’t talk about the Senate race without being a little bit more expansive about

how I got into politics in the first place. [01:17:20] And I know you want to end up in

architecture. But it was architecture and city planning that got me involved in politics.

Remember I graduated from M.I.T., came back and did a thing in city planning and worked with

Floyd McKissick on something called Soul City. And I’m not going to get into that, you can

look that up. We were trying to develop this idealized new town. And then I moved from there

to forming an architectural firm with Jeff Huberman in 1971. And as a result of that, spent some

time getting to know city leaders who often would come to me about some advice on how to

plan something, or where do you place these kinds of things, and what can we do to make this

area better? You know, “You’re a trained planner” and blah, blah, blah. And as a result of that,

working with the council and doing some city design projects, we designed [a prototype]

neighborhood center. Which was a new strategy for improving these neighborhoods of color that

were the second tier of neighborhoods. [coughs and pauses to drink some water] And [I] got

asked to fill an unexpired term on the city council and I filled that one-year term and took to it,

took to politics like a duck takes to water.

MHP: [01:19:18] I have to say, I’m not surprised. [laughs] Are you surprised that I’m

not surprised?

30

HG: Yeah, a lot of people in Charlotte were surprised because I had not involved myself

in elective politics. I was spending time talking to people who were in politics. And the only

reason I got consideration was because I was apolitical. The seat was a coveted seat on the city

council, which at that time was made up of seven at-large elected council members, no districts

or anything, had to win the whole city, the top seven vote getters. And it required people who

understood politics and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. But in order to avoid a conflict, the city

council gets to appoint the additional [vacant] seat. Well, not additional seat, but gets to appoint

a person to that vacant seat.4 And there were so many people in the African American

community clamoring for that seat until they decided, “We can’t give any of those people a head

start. So, let’s pick someone who’s apolitical.” I keep bringing my mother up, because she

thought I had lost my mind. “Here you were beginning a great career in architecture, building a

firm. And now you want to wallow in the mud with politicians?” She had very traditional views.

For some reason I said yes, and I enjoyed it. And through the years, you know, kept getting

elected, finally losing the mayor’s race for a third term in the late [19]80s. [01:21:24] And

maybe sitting around the house and not doing anything, and watching Jim Hunt lose a race for

the Senate. And watching a guy who I thought was a demagogue continue to win and to mislead

a lot of North Carolinians as to what their future could be like. He was using the hate message

way back. His entire career was that, but he managed to get elected over and over, using fear as

a tactic. And so, my campaign manager and I were playing tennis in our backyard [in the spring

of 1989] and we said, nobody is going to — because Jim [Hunt] had decided he’d had enough of

it. He was not going to run against Jesse Helms a second time, which meant that Helms was

going to go unchallenged. And so, we said, well, we’ll run, if for no other reason than to present

an alternative platform to the citizens of North Carolina. Let us talk about health care. Let us

4 During transcript review, Mr. Gantt noted that the seat had been occupied by a prominent African American, Fred

Alexander.

31

talk about education. Let us talk, even way back then, about the environment. Let’s just build a

campaign around those themes and see if we can, first of all, get nominated. [laughs] Forget

about Jesse Helms. Let’s see if he can get nominated amongst the Democrats. No one had done

that before. And it was one of the most inspiring campaigns that I’d ever been a part of. We won

the Democratic nomination. Other than the night that I won my first campaign, my first mayor’s

race, is probably one of the highlights of my life just winning that nomination. Then after having

won it, we said, oh, boy. It’s like the dog catching up with [the auto], it was like, now we got it,

what are we going to do? [01:23:28] How are we going to run against this guy, who was just

such a negative person? So we decided to run a campaign that was ignoring him and spending

time defining ourselves and making it clear that Helms didn’t spend time worrying about those

[important “kitchen table”] issues. So, we showed some of them, the climate and the

environment, the bad water and the bad air. We talked about education from pre-K all the way

up and how much good that would do for white and Black citizens in this state. We talked about

health care and how that would help so many people in rural areas and in [inner] cities. This was

way before Obamacare was even uttered by anybody, way before we knew Obama or anybody

else did. Bottom line is we were doing a good job. Almost kind of daring Jesse to bring up the

race issue. Not giving him a real excuse. They tried to do lots of things like use the television

[ads] to bring up things that they thought were negative in my past. Not a lot of that to

[inaudible]. And then there was a poll that came out about a month before the end of the

campaign, and it’s called the White Hands — the poll, first of all, came out, showing us leading

Jesse by about nine points. [01:25:27] Charlotte Observer ran it. Everybody in our campaign

was ecstatic. Boy, that strategy worked. We neutralized it [race as an issue]. Didn’t give him an

excuse to deal with it. And then we gave him an excuse. The excuse we gave him was there was

a bill in the Senate that dealt with quotas. And at a press conference at UNC Charlotte, they

were asking me a question about whether I supported quotas or not. I said, not in the sharpest

32

sense in the way you’re using that. Anyway, it was a political answer that we were prepared to

answer that said we thought, we did feel as if there were to be efforts made to move people into

jobs and universities, and affirmative action was in fact a good thing. So [inaudible] somewhat

denied, but Jesse Helms, to his credit, had very, very sharp folks to support his campaign and

know how to promote it.5 So, one night, my campaign manager [Mel Watt] awakened me and

said, you got to see this. I know it’s crazy, but just this thing just came in. This ad that Jesse is

running, and he said it, he said it was [later called] the White Hands ad. Go look it up. I’m sure

you’ve already seen it. Saying this [white] person is balling up an application, saying, you

needed this job, but Harvey Gantt gave it to a [Black] person. Very skillful way of dealing with

that portion of it. [01:27:30] So, it was the introduction of race at the campaign. Introduction of

affirmative action into the campaign. And they literally ran that ad morning to night, and it

started to move the numbers.

MHP: What was your, when you first saw the ad, your first time you saw it, what did

you think when you saw it?

HG: I actually thought, and I gave a press conference a couple of blocks away from here

that said, “North Carolinians deserve better than that. We’ve gotten almost to the end of this

campaign, a month within the end of it. And I personally thought that I got a chance to say what

I needed to say, and [Helms] got a chance to say how good he was. And the citizens of North

Carolina were going to decide this election. I’m shocked that he would introduce such a racially

motivated ad designed to appeal to fears rather than the hopes and aspirations of ours.” And that

was unfair. And I actually believed that most North Carolinians would see it for what it was. I

actually believed that. There were smarter people in my campaign who didn’t believe that. And

they then explained to me what had happened, that Helms, we had inoculated him in a sense [on

5 During transcript review, Mr. Gantt clarified, “My response was twisted by the Helms team to mean that I supported

quotas, and they used that theme to develop a devastating T.V. ad.”

33

the race issue]. Didn’t give him anything to bite down on where he could use the race ad. But

that innocent question at a press conference at UNC Charlotte gave them what they needed,

which was a way to attack the race issues through the affirmative action thing. Now whether

they would run an ad like that, no politician in the country would try doing that. But Jesse

Helms would. And it made all the difference. That lead that we had was wiped out. And we

struggled in the waning days of the campaign to try to overcome that. [01:29:29] And we’d still

be leading sometimes, forty-nine percent, forty-eight percent, but not eight or nine points. And

[our side knew that if] if you don’t get fifty percent in the polls, you're not going to win the

election.

MHP: This is one of those additional questions that I have that, you know, before I get

to this, let me just ask you, when you saw what Helms did, your experience of enrolling and

getting into Clemson, working with LDF, did that somehow prepare you for sort of these barbs

that Helms threw at you?

HG: Oh, yeah. I was the one chomping at a debate and he absolutely refused three times.

He just, he was not going to debate me. And we actually were a little bit surprised about that

because we thought Helms would have loved to have been on a platform with a Black man, a

clearly Black man, and really sort of send his signals to a statewide audience. And that would be

enough. But he absolutely shunned sitting down and talking about issues. And we were prepared

to talk about race. What I think the experience of my earlier life said, to me, was I need not be

intimidated by what he represented. As a matter of fact, I was saying he was doing it so poorly

that I thought I could do it better. That in itself could have been intimidating to him, could have

been intimidating to him, that he might not want to sit on stage and have to debate the question.

So, it was best for him. And the message was sent very clearly, best for him not to be seen in the

same room, not to even campaign in the same town if I’m there. [01:31:33] They used to have a

game finding out where I was, simply because that would give me too much relevance. And the

34

word was he was not going to dignify Harvey Gantt. Not even being in the same room with him.

We actually thought that would backfire, but it didn’t.

MHP: This was one of the additional questions I sent to you, and I know definitely we

want to ask this. You’ve held political office, run for national office. What are your thoughts

then on ballot security programs related to recent people that LDF has opposed as judicial

nominees? And I gave, for instance, Thomas Farr, was nominated 2017, 2018. He worked with

Jesse Helms as a lead legal counsel on his Senate campaigns. So, just what’s your, kind of when

you think about this, and LDF’s continued work, right, they’re continuing this work. When you

think about as they come out to oppose some of these nominees who clearly are, what some

would say, trying to intimidate voters and to restrict voters’ rights.

HG: Let me just put it this way. And I thought about this when John Lewis died. And I

actually said it with my friend Julius Chambers before he died. It is amazing to me that we’re

still fighting the same battles. That this thing doesn’t go away simply by believing that the legal

structure can change and then change people’s behavior. The Voting Rights Act of [19]65, the

Public Accommodations Act of [19]64, all those things, Housing Act of [19]68, were designed

to change the behavior of people and it didn’t. [01:33:41] These folks are still fighting this same

battle, but they’re doing it in different ways. When I ran against Jesse Helms, they sent out

postcards to African American voters telling them lies about if you moved or you did certain

kinds of things, you could be arrested by voting. And we don’t know how many votes that

suppressed. I.D., voter I.D. requirements now that are heavily against those more from our

community than theirs, you know, the middle class community, a lot of my [African American]

buddies said, you know, why are we arguing about that, Harvey? I mean, all of us have driver’s

licenses, all of us. I said, yeah, that’s the problem with that is that you’re identifying a good

segment of the middle-class Black community, but we really don’t know how many people don’t

have picture IDs and whatever that exist in rural areas, [and] the depths of the ghetto in urban

35

centers. But why do they need that? There are other ways to verify whether this person has

voted. The other kinds of measures that are designed to keep — you’re not encouraging people

to vote. All of a sudden, you’re concerned about whether that ballot is secure enough. So, mail-

in ballots and other kinds of things have come under scrutiny. But we sum it all up to say it’s

still the same game that we fought in 1965, [19]55. Keep Black people from voting. I’m being

very blunt here. Black people from voting. That’s been the charge since the end of

Reconstruction. Keep them from voting. The tactics may have changed, but the overall design is

to minimize that vote. [01:35:44] And sometimes we get so caught up in it ourselves that any

little thing that seems to interfere with our ability to send and get people to the polls, we object

to. I mean, we don’t understand why Republicans react to taking people to the polls on Sunday

or cutting down early voting. In fact, if we had early voting when I ran against Helms in 1990

and 1996, we might have won the election, we actually might have won the election. They want

to restrict the time, restrict the places. All of that is designed for one thing. And so, Chambers

and I would talk about it. It’s not over. It’s still a battle. It’s going to be a battle for my

grandchild. And that’s unfortunate, but, it’s just unfortunate. That’s the cynicism I come away

with. Did we fight all these years to really be not far from the same place? I take that back to

architecture. We were saying two percent of the architects in this country back then, when I

went to Iowa State, were Black. Guess how many architects there are today that are Black as a

percentage.

MHP: What is the percentage?

HG: Two percent.

MHP: Two percent.

HG: Isn’t that amazing? All the progress that I made, all the things that I did, all the

buildings I designed, all the young people that we’ve encouraged to study architecture. It’s still

36

two percent. And in a way, it’s like Chambers and I were saying, sometimes that change is so

hard to come by.

MHP: And to maintain, right? And so, people who are still in the battle, LDF is still

there. What do you imagine it would be like if LDF were not still doing this work?

HG: [01:37:44] I hadn’t ever thought about that. I assumed they were still there. That’s

why — I assumed there were people. I mean, I have, you didn’t bring this up, but I have given

to that organization. It’s one of the ones that I’ve given to for the last sixty years, maybe. Easily.

And I assume there are a lot of other people still doing that, because that’s the only way they can

exist. They are always going to be needed, I don’t think there’s ever going to — I used to be

naïve one time and say in speeches I made across the Carolinas, “One day, there won’t even be a

need for civil rights organizations. They will have nothing to do. Why should they have

anything to do? You know, the American people are going to obey the law and we will try to get

along with each other. What will be the role of an NAACP then? Go in the courtroom and fight

for what?” But they’re still fighting.

MHP: So, NAACP, LDF, as critical as ever?

HG: Yes. Yes. I’m not trying to do a commercial for them, but let me just put it this

way. They are still needed. I’m not going to give my money to a lost cause. They’re still needed.

MHP: Let me just make sure I got —

HG: I hope I answered your questions.

MHP: Oh, my gosh. You’re a wonderful interviewee, again because you know how to