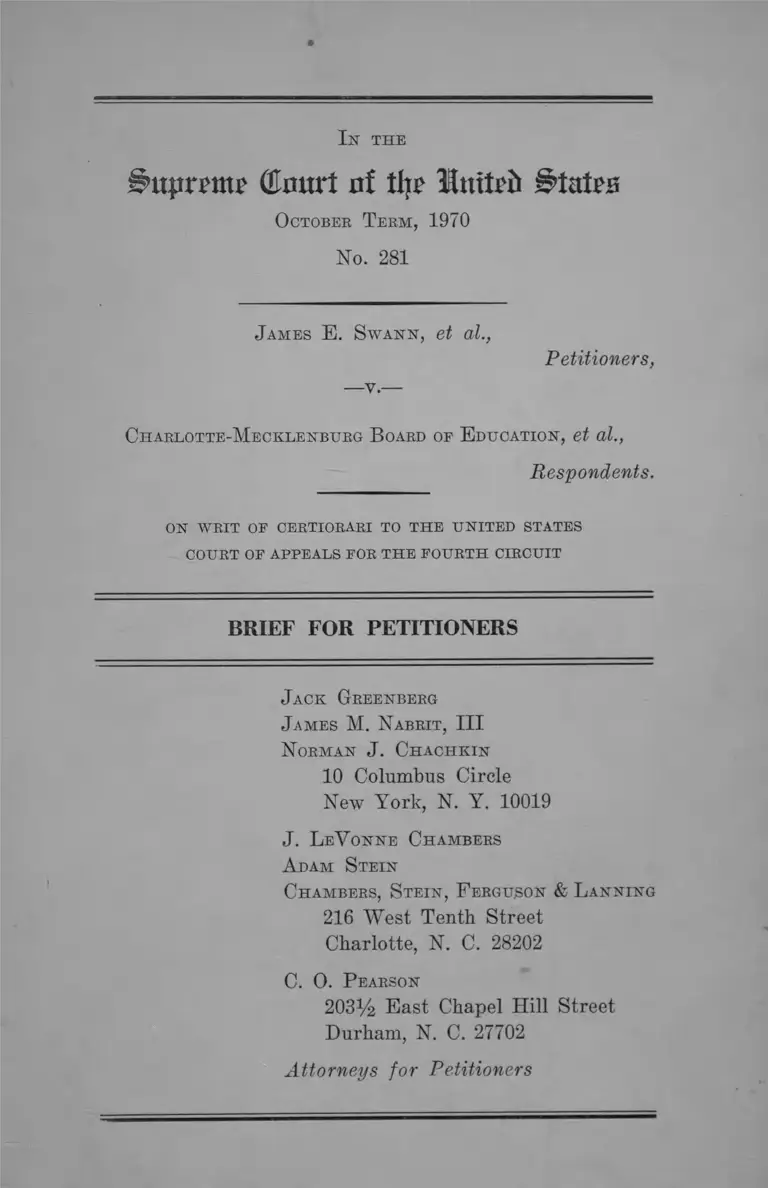

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education Brief for Petitioners, 1970. 205fca7e-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d11f887c-ec4f-4386-bf96-bbd4b80c063c/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenberg-board-of-education-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Supreme dmtrt at % Initrii States

O ctobee T ee m , 1970

No. 281

J ames E . S w a n n , et at.,

—v.—

Petitioners,

C h arlotte-M bcklenburg B oard of E ducation , et al.,

Respondents.

on w r it of certiokabi to th e un ited states

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M . N abrit , III

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J. L eV onne C ham bers

A dam S tein

C h am bers , S t e in , F erguson & L an n in g

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

C. O. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, N, C. 27702

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions B elow ........................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................... 3

Questions Presented ........................................................... 4

Constitutional Provisions Involved ....................... ........ 4

Statement ............................................................................... 4

1. Introduction ............................................................. 4

2. Proceedings Below ................................................. 5

3. Proceedings Pending Certiorari ......................... 10

4. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg County School Sys

tem in 1968-69 11

5. Two Schools in 1969-70 ..................................... 16

6. The Plan Ordered by the District Court in

February, 1970 ........................................ 19

a. High Schools ..................................................... 20

b. Junior High Schools ...................................... 21

c. Elementary Schools ......................................... 22

d. Transportation ................................................. 23

7. Other Elementary Plans Reviewed by the Dis

trict Court in July, 1970 ........................................ 30

a. The Majority Board Plan ............................... 30

b. The HEW Plan ............................................... 30

c. The Finger Plan, the Board Minority Plan

and the Preliminary Finger Plan ................. 33

Summary of Argum ent......................................................... 34

PAGE

11

A rgum ent—

PAGE

I. The Public Schools of the Charlotte-Meeklen-

burg School System Are Racially Segregated

in Violation of the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment as the Result of

Governmental Action Causing School Segrega

tion and Residential Segregation ..... ............. 41

A. The Schools Are Organized in a Dual Seg

regated Pattern ............................................... 41

B. Governmental Agencies Created Black

Schools in Black Neighborhoods by Pro

moting School Segregation and Residen

tial Segregation ............................................... 46

II. The District Court Was Correct in Ruling That

the Dual Segregated System in Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Must Be Disestablished by Re

organizing the System So That No Racially

Identifiable Black Schools Remained. The

Court of Appeals Erred in Substituting a Less

Specific Desegregation Goal ............................... 54

A. This Court’s Decisions Require Complete

School Desegregation ..................................... 54

B. The Fourth Circuit’s New Reasonableness

Rule Makes the Goal of Desegregation Less

Complete and Specific and Threatens to

Undermine Brown v. Board of Education 58

C. The Goal of Integrating Each School in

Charlotte Is Consistent With Federal Statu

tory and Constitutional Requirements ....... 65

I l l

PAGE

III. The District Court Acted Within the Proper

Limits of Its Discretion by Ordering a Plan

Consistent With the Affirmative Duty to De

segregate the Schools and the Objective of

Preventing Resegregation ......................... 68

A. The Finger Plan Promises to Establish a

Unitary System ............................................... 68

B. The Court Ordered Plan Is Feasible ....... 69

C. The Finger Plan Utilizes Appropriate Tech

niques to Achieve Pupil Desegregation ..... 75

D. The Neighborhood School Theory Cannot

Be Justified on the Basis of History and

Tradition Because It Was Widely Disre

garded in Order to Promote Racial Segre

gation ................................................................. 80

E. The Finger Plan Is Necessary to Accom

plish the Constitutional Objective ............... 83

F. The Court of Appeals Applied an Improper

Standard for Appellate Review of the Dis

trict Court’s Discretionary Determination in

Formulating Equitable Relief ..................... 84

C onclusion ........................................................................................ 87

B bief A ppen dix

Memorandum of Decision and Order, dated August

3, 1970 .....................................................................Br. A1

Memorandum Decision, dated August 7, 1970 ....Br. A39

Defendants’ Report of Action Taken as Directed

by the Court in Its Order of August 3,1970 ....Br. A40

IV

T able of A uthoeities

Cases: page

Alexander v. Hillman, 296 U.S. 222 (1935) ................. . 86

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ...........................................7,8,40,43,64,86

Andrews v. City of Monroe, No. 29358 ------ F .2 d --------

(5th Cir., Apr. 23, 1970) ............................................... 65

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ....................... 50

Baldwin v. New York, 26 L.ed 2d 437 (1970) ........ ....... 63

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964) ............. ......... 35, 50

Bowman v. The School Board of Charles City County,

382 F.2d 326 (1967) ....................................................... 6

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction of Pinellas

County, No. 28639,------ F.2d -- ----- (5th Cir., July 1,

1970) ................................................................................... 76

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County, 402 F.2d 900 (5th Cir. 1968) ............ ....... . 52

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 397

F.2d 37 (4th Cir. 1968) ....................................... 52,53,76

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

35, 47, 54, 56, 59, 62, 64

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

54, 68, 75, 84

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1

of Clarendon County, No. 14571,------ F .2d ------- (4th

Cir., June 5, 1970) .......................................................59,76

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) ....................... 49

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

Va., 332 F.2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964) ............................... 82

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U.S. 290 (1970) .........................................................8,65,86

V

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock, No. 19795,

----- F.2d —— (8th Cir., May 13, 1970), cert, pend

ing No. 409 O.T. 1970 ................................................... 77

Continental Illinois Nat. Bank & Trust Co. v. Chicago

R.I. & P. R. Co., 294 U.S. 648 (1935) ......................... 82

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).............35,46,53,54,75

Corbin v. County School Board of Pulaski County,

Va., 177 F.2d 924 (4th Cir. 1949) ................................... 82

Crisp v. County School Board of Pulaski County, Ya.

(W.D. Va. 1960), 5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 721 ................. 82

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 393 F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968) ....................... 52, 76

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 396 U.S. 269 (1969) ...........................8, 86

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), affirmed, 375 F.2d 158 (10th

Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967) ........... 52,65

Eason v. Buffaloe, 198 N.C. 520, 152 S.E. 496 (1930).... 49

Goins v. County School Board of Grayson County, Va.,

186 F. Supp. 753 (W.D. Va. 1960) ............................ . 82

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) .....................................6, 35, 36, 38, 39,

40, 43, 47, 54,

55, 57, 58, 64,

68, 69, 76, 86

PAGE

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, No.

14335 ------ F .2 d -------- (4th Cir., June 17, 1970).... . 77

Griffin v. Board of Education of Yancey County, 186

F. Supp. 511 (W.D. N.C. 1960) ................................... 81

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)...............37,63,

75, 85

VI

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 417 F.2d 801

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969)....... 76

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County,

Ark., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)............................ . 82

Harvest v. Board of Public Instruction of Manatee

County, No. 29425, ------ F.2d ------ (5th Cir., June

26, 1970) .......................................................................... 76, 77

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969)........... ................... 47,52

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach

County, 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) ........................... 52

Jackson v. Marvell School District No. 22, 425 F.2d

211 (8th Cir. 1970) ..... .............. ...................................... 76

Jones v. School Board of Alexandria, Va., 278 F.2d 72

(4th Cir. 1960) ............................................................... 82

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) ................. 66

Kemp v. Beasley, 423 F.2d 851 (8th Cir. 1970) .......76, 77

Keyes v. School District No. One, Denver, 303 F. Supp.

289 (D. Colo. 1969), stay granted, ------ F.2d —__

(10th Cir. 1969), stay vacated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969)..52, 65

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hills-

brough County, No. 28643,------ F .2 d -------- (5tli Cir.,

May 11, 1970) ..................................................................’ 76

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968) ...............................................................6,35,41,43,64

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board, 304 F.

Supp. 244 (E.D. La. 1969) ................. 66

Nesbit v. Statesville City Board of Education, 418 F.2d

1040 (4th Cir. 1969) ..........................................................g,76

Northcross v. Board of Education, 397 U.S. 232

(197°) ...............................................................................41,70

PAGE

V ll

Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N.C. 290, 37 S.E.2d 895 (1946). 49

Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968) ....... 6

Rogers v. Hill, 289 U.S. 582 (1933) ............................... 85

School Board of Warren County, Va. v. Kilby, 59 F.2d

497 ( 4th Cir. 1958) .............. ............................................ 81

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) .................63,66

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ................... 15, 49, 51

Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (M.D. N.C. 1969) ..... 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

243 F. Supp. 667 (W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369

F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966) .................................................1,41

Tillman v. Board of Public Instruction of Volusia

County, No. 29180, — F.2d — (5th Cir., April 23,

1970) ...........................................................................65,76,77

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington Coun

ty, 166 F. Supp. 529 (E.D. Va. 1958) ........................... 83

United States v. Board of Trustees of Crosby Inde

pendent School District, 424 F.2d 625 (5th Cir.

1970) ...........................................................................65,76,77

United States v. Choctaw County Board of Education,

417 F.2d 838 (5th Cir. 1969) .......................................... 52

United States v. Cook County, Illinois, 404 F.2d 1125

(7th Cir. 1968) ................................................................. 63

United States v. Corrick, 298 U.S. 435 (1936) ............. 85

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................... 52

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

District, 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

— U.S. — (1970) ....................................................... 52

PAGE

V1U

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1969), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S. 840

(1967) ....................................... -....................................... 65

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Edu

cation, 395 U.S. 225 (1969)...................................36,40,57,

67, 68, 86

United States v. School Dist. 151 of Cook County, 404

F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968), aff’g 286 F. Supp. 786

(N.D. 111. 1968) .................................................. 52, 65, 76, 77

United States v. W. T. Grant, 345 U.S. 629 (1953) ....40, 85

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Board, — F.2d —

(5th Cir. 1970) ................................................................. 52

Vernon v. R. J. Reynolds Realty Co., 226 N.C. 58, 36

S.E.2d 710 (1946) ........................................................... 49

Walker v. County School Board of Floyd County, Va.

(W.D. Va. 1960), 5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 714 .................... 82

Whittenberg v. School District of Greenville County,

C.A. No. 4396, D. S.C. (Feb. 4, 1970) ......... ............... 67

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction of Bay

County, Fla., — F.2d — (5th Cir., No. 29369, July 24,

1970) ............................................................. 52

PAGE

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, §§ 401(b), 407 (A )(2 ), 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000c(b), 2000c-6(a) (2) ............................. 37, 66

28 U.S.C. § 47 .................................................................. 4

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ............................................................... 5

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ............................................................... 5

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 115, 176.1 [1969 Supp.] ................... 9

IX

Other Authorities-.

Abrams, Forbidden Neighbors (1955) ........................... 51

“NEA Brief Amicus Curiae” ................................. ......... 63

“ On the Matter of Bussing: A Staff Memorandum

from the Center for Urban Education” (February

1970) ................................................................................. 79

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A Report of the

U. S. Commission on Civil Rights (1967) ...........45, 50, 51

Statement of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights Concerning the “ Statement by the President

on Elementary and Secondary School Desegrega

tion” , April 12, 1970 ............................ 62

Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (1948) ...................................... 51

Weinberg, “Race and Place, A Legal History of the

Neighborhood School” (U.S. Govt. Printing Office,

1967) ................................................................................... 83

PAGE

I n t h e

i>upr?mT Court of thr luttri States

O ctober T er m , 1970

No. 281

J ames E . S w a n n , et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

C h arlotte-M ecklen burg B oard of E ducation , et al.,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR TH E FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinions of the courts below are as follows J

1. Opinion and order of April 23, 1969, reported at 300

F. Supp. 1358 (285a).

2. Order dated June 3, 1969, unreported (370a).

3. Order adding parties, June 3, 1969, unreported

(374a).

4. Opinion order of June 20, 1969, reported at 300 F.

Supp. 1381 (448a).

1 Earlier proceedings in the same case are reported as Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 243 F. Supp. 667

(W.D. N.C. 1965), affirmed, 369 F.2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966).

2

5. Supplemental Findings of Fact, June 24, 1969, re

ported at 300 F. Supp. 1386 (459a).

6. Order dated August 15, 1969, reported at 306 F.

Supp. 1291 (580a).

7. Order dated August 29, 1969, unreported (593a).

8. Order dated October 10, 1969, unreported (601a).

9. Order dated November 7, 1969, reported at 306 F.

Supp. 1299 (655a).

10. Memorandum Opinion dated November 7, 1969, re

ported at 306 F. Supp. 1301 (657a).

11. Opinion and Order dated December 1, 1969, reported

at 306 F. Supp. 1306 (698a).

12. Order dated December 2, 1969, unreported (717a).

13. Order dated February 5, 1970, reported at 311 F.

Supp. 205 (819a).

14. Amendment, Correction, or Clarification of Order of

February 5, 1970, dated March 3, 1970, unreported

(921a ).

15. Court of Appeals Order Granting Stay, dated March

5, 1970, unreported (922a).

16. Supplementary Findings of Fact dated March 21,

1970, unreported (1198a).

17. Supplemental Memorandum dated March 21, 1970,

unreported (1221a).

18. Order dated March 25, 1970, unreported (1255a).

19. Further Findings of Fact on Matters raised by Mo

tions of Defendants dated April 3, 1970, unreported

(1259a).

3

20. The opinions of the Court of Appeals filed May 26,

1970, not yet reported, are as follow s:

a. Opinion for the Court by Judge Butzner (1262a).

b. Opinion of Judge Sobeloff (joined by Judge Win

ter) concurring in part and dissenting in part

(1279a).

c. Opinion of Judge Bryan dissenting in part

(1293a).

d. Opinion of Judge Winter (joined by Judge Sobel

off) concurring in part and dissenting in part

(1295a).

21. The judgment of the Court of Appeals appears at

1304a.

22. The opinion of a three-judge district court in an

ancillary proceeding in this case dated April 29,1970,

not yet reported, appears at 1305a.

23. The Memorandum of Decision and Order dated Au

gust 3, 1970, unreported of the district court entered

following the further proceedings directed by the

Court of Appeals (1278a-1279a) and authorized by

this Court (1320a) is appended to this brief.2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

May 26, 1970. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1). The petition for a writ

of certiorari was filed in this Court on June 18, 1970, and

was granted on June 29, 1970 (1320a).

2 The appendix to the brief containing the decision on remand

is herein designated “Br. A— — The other matters, including all

other previous opinions are printed in separate appendix volumes

and are herein designated “•------a.”

The Memorandum dated August 7, 1970, unreported is printed

at Br. A39.

4

Questions Presented

1. Whether the trial judge correctly decided he was re

quired to formulate a remedy that would actually integrate

each of the all-black schools in the northwest quadrant of

Charlotte immediately, where he found that government

authorities had created black schools in black neighbor

hoods by promoting school segregation and housing segre

gation.

2. Whether, where a district court has made meticulous

findings that a desegregation plan is practical, feasible and

comparatively convenient, which are not found to be clearly

erroneous, and the plan will concededly establish a unitary

system, and no other acceptable plan has been formulated

despite lengthy litigation, the Court of Appeals has discre

tion to set aside the plan on the general ground that it im

poses too great a burden on the school board.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

Statement

1. Introduction

This Court has granted review3 of an en banc4 * decision

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir-

3 The defendants have filed a cross petition for writ of certiorari

which is pending. (Oct. Term 1970, No. 349.)

4 Prior to argument, Judge Craven entered an order disqualify

ing himself. He had decided the case as a district judge in 1965

(243 F. Supp. 667) and was of the opinion that this previous

participation barred him from hearing the case as a circuit judge.

28 U.S.C. §47.

5

cult setting aside certain portions of an order of Judge

James B. McMillan of the Western District of North Car

olina which had required the complete desegregation of

the Charlotte-Mecklenburg County public school system.

Three members of the court, in a plurality opinion written

by Judge Butzner, agreed with the lower court that the

school board had an affirmative duty to employ a variety

of available methods, including busing, to disestablish its

dual school system and approved the portions of the order

providing for the desegregation of the junior and senior

high schools. As to the plan ordered for the elementary

schools, however, they thought that the board “ should not

be required to undertake such extensive additional busing

to discharge its obligation to create a unitary school sys

tem (1271a).” Judges Sobeloff and Winter viewed Judge

McMillan’s decision as appropriate in all respects and

would have affirmed the decision in its entirety (1279a,

1295a). Judge Bryan who would have reversed the entire

order expressed disapproval of busing to achieve racial

balance which he found the order to require for junior and

senior high school students as well as elementary (1293a).6

2. Proceedings Below

Black parents and students brought this action in 1965

against the local school board to desegregate the consoli

dated school district of Charlotte City and Mecklenburg

County, North Carolina pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1343 and

42 U.S.C. §1983. The North Carolina Teachers Association,

a black professional organization, intervened seeking de

6 This is essentially the position of the defendants as stated in

their cross petition for writ of certiorari. See note 3, supra. They

not only argue that the Court of Appeals erred in approving Judge

McMillan’s plan for junior and senior high schools, but also dis

agree with the Court’s conclusion that the board’s elementary plan

is unconstitutional.

6

segregation of the faculties on behalf of the black teachers

in the school system. More recently, other defendants have

been added, including the State Board of Education, the

State Superintendent of Public Instruction and the individ

ual members of the local board (464a, 374a, 901a). This

current phase6 of the litigation began in 1968 when the

plaintiffs, relying upon the Green trilogy,7 reopened the

case seeking the elimination of all vestiges of the dual sys

tem (2a).

Judge McMillan first heard testimony in March, 1969

and entered his initial opinion the following month (300 P.

Supp. 1358; 285a) judging the school system to be illegally

segregated and requiring the hoard to submit a plan for

desegregation. Extensive proceedings followed over the

6 The ease was first tried in the summer 1965. (243 F. Supp.

667 (1965).) The plaintiffs challenged an assignment plan where

initial assignments were made pursuant to geographic zones from

which students could transfer to schools of their choice. Plaintiffs

complained that many of the zones were gerrymandered and that

the zones of ten rural and concededly inferior black schools which

the board claimed would be abandoned within a year or two over

lapped white school zones. They also attacked a free transfer policy

which had resulted in the transfer of each white child initially

assigned to black schools as had the previous policy allowing for

minority to majority transfers. Also under attack was the board’s

policy looking to the “eventual” non racial employment and as

signment of teachers. Underlying plaintiffs’ specific grievances was

their general assertion that the Constitution required the school

board to take active affirmative steps to integrate the schools.

The district court approved the assignment plan but required

“ immediate” non-racial faculty practices.

The court of appeals affirmed. (369 F.2d 29 (1966).) The deci

sion noted that the 10 black schools were closed at the end of the

1965-66 school year. The court held, as it did the following year

in Boivman v. The School Board of Charles City County, 382 F.2d

326 (1967), rev’d sub nom. Oreen v. County School Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), that the school hoard had no

affirmative duty to disestablish the dual system.

7 Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968); and Raney v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 443 (1968).

7

next twelve months.8 9 He rejected the first plan submitted

and called for another, found the second plan inadequate

but “reluctantly” accepted it as an interim measure for

the 1969-70 school year, again required a new plan which

after review was also found unacceptable.8 On December 1,

1969, following the court’s patient but unavailing efforts

to secure from the board an acceptable plan, the fail

ure of the board to carry out its minimal interim plan

for 1969-70 and the mandate of this Court10 that schools

are to be desegregated “ at once” , Judge McMillan decided

to appoint an educational consultant to assist him in devis

ing a desegregation plan (698a). The following day, the

court appointed Dr. John A. Finger, Jr., a Professor of

8 Judge McMillan has provided an excellent summary of the

proceedings in the district court prior to the decision of the court

of appeals in his Supplemental Memorandum of March 21, 1970

(1221a).

9 The first plan was rejected on June 20, 1969 (448a). The Court

found that the board had sought from the staff a “minimal” and

inadequate plan, that the staff produced such a plan and the board

thereupon eliminated its only effective provisions before submitting

it to the court.

The court found the second plan inadequate on August 15, 1969

(580a) but accepted it for the 1969-70 school year only because it

promised some measure of desegregation and there did not appear

to be sufficient time prior to the opening of the new school term

for the development and implementation of a more effective plan.

The failure of the board to accomplish what the plan had prom

ised was determined on November 7, 1969 (657a).

The third “plan” was simply a statement of guidelines as to

how the board intended to produce a plan. The guidelines prom

ised no particular results and were thus rejected on December 1,

1970 (698a).

Judge Sobeloff traces this history in an extensive footnote (1291a,

n. 9). He concludes “ [T]he above recital of events demonstrates

beyond doubt that this Board, through a majority of its members,

far from making ‘every reasonable effort’ to fulfill its constitu

tional obligation, has resisted and delayed desegregation at every

turn.”

10 Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19.

8

Education at Rhode Island College who was directed to

work with the administrative staff to prepare a plan for

the court’s consideration (717a). The board was again

invited to submit another plan (698a).

On January 20, 1970, plaintiffs requested that Dr. Finger

promptly present his plan so that the schools could be de

segregated “at once” (718a).11 The Finger plan (835a-

839a) and a fourth board plan (726a) were filed with the

court in early February. Judge McMillan held further

hearings and entered an order on February 5 directing the

desegregation of the students and teachers of the elemen

tary schools by April 1, 1970, and of the junior and senior

high schools by May 4, 1970 (819a).12 The order was based

upon the plans submitted by the board and Dr. Finger.

The school board appealed (904a) and sought a stay in

the court of appeals. On March 5,1970, the court of appeals

11 Plaintiffs’ request followed the controlling decisions of Alex

ander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969) ;

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public Schools,

396 U.S. 269 (1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970); and Nesbit v. Statesville City Board

of Education, 418 F.2d 1040 (4th Cir. 1969).

This was not the first request by plaintiffs for immediate relief.

In September of 1969 the plaintiffs’ motion for a finding of con

tempt and for immediate desegregation (596a) had led to the

court’s finding in November that the board had not accomplished,

during the 1969-70 school year, what it had been ordered to do

(655a).

The plaintiffs were required to file a variety of other motions as

well, such as motions for contempt (596a, 914a), objections to

patently defective plans (e.g. 692a), a motion to enjoin school

construction (324a), motions to vacate state court orders (see

925a), motions to add new defendants (840a, 906a) and motions

to enjoin state officials from interfering with orders of the court

(840a, 906a, 914a). Despite these and other efforts in the district

court, the court of appeals and this Court, there has yet to be any

more desegregation in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system

than when this round of litigation commenced.

12 The order was slightly modified on March 3, 1970 (921a).

9

stayed a portion of the order relating to the elementary

schools and directed that the district court make additional

findings concerning the cost and extent of the bussing re

quired by the February 5 Order (922a). The plaintiffs

applied to this Court to have the partial stay rescinded;

the application was denied.

The district court received additional evidence pursuant

to the directives of the court of appeals and entered a sup

plemental Memorandum (1221a) and Supplemental Find

ings of Fact (1198a)18 on March 21, 1970.* 14

18 The supplemental findings were amended in certain respects

on April 3, 1970 (1259a), in response to a motion by defendants

(1239a).

14 During this period there were also proceedings concerning the

North Carolina anti-bussing law:

“In June of 1969, pursuant to the hue and cry which had been

raised about ‘bussing,’ Mecklenburg representatives in the

General Assembly of North Carolina sought and procured

passage of the so-called ‘anti-bussing’ statute, N.C.G.S. 115-

176.1 [supp. 1969]” (1223a).

Plaintiffs were granted leave to file a supplemental complaint

in July, 1969 and to add the State Board of Education and State

Superintendent of Public Instruction as defendants to attack the

statute (464a). At that time the statute did not appear to the

court to be a barrier to school desegregation (579a, 585a).

However, in the spring of 1970, the Governor and other state

officials directed that no public funds be expended for the trans

portation of students pursuant to the district court order of Feb

ruary 5 and several state judges issued ex parte orders of similar

effect acting under color of the state statute. (See 1305a, 1307a,

1308a).

At the plaintiff’s request Judge McMillan added the Governor,

other state officials and one group of state court plaintiffs as de

fendants (901a). He, thereafter determined that the constitu

tionality of the state statute was at issue and, therefore, requested

and the Chief Circuit Judge appointed a three-judge court. The

court convened in Charlotte on March 24. On April 29, 1970, the

court entered its decision (1305a) declaring unconstitutional the

portions of the statute prohibiting the assignment of any students

“on account of race, creed, color or national origin, or for the

purpose of creating a balance or ratio of race, religion or national

1 0

The opinions and judgment of the court of appeals were

filed on May 26, 1970. The court decided by a vote of 4 to 2

to vacate and remand the judgment of the district court

for further proceedings. A majority for the judgment was

created by the vote of Judge Bryan joining with the three

members of the court subscribing to the plurality opinion

written by Judge Butzner, although Judge Bryan dissented

from the views expressed in the plurality opinion (1304a,).* 15

3. Proceedings Pending Certiorari

Judge McMillan conducted hearings from July 15 through

July 24, 1970 in accordance with the order of this Court of

June 29, 1970 granting certiorari, authorizing the remand

directed by the Court of Appeals for further proceedings

and reinstating the district court’s judgment.

The school board had filed, but did not support, a plan

prepared by the Department of Health, Education and Wel

fare (hereinafter HEW) and a plan prepared by four of

the five members of the school board.

The Department of Justice appeared at the hearing as

amicus curiae to present the HEW plan. Testimony was

therefore directed to the comparative advantages and dis

advantages to these plans and another plan which had

been prepared by Dr. Finger during his tenure as court

consultant.

origins, the involuntary bussing of students in contravention of

[the statute] and the use of public funds . . . for any such

bussing.” J

The state and the local defendants have noted appeals to this

Court.

15 The judgment was vacated in its entirety. Judge Butzners

reason for this action was to give greater flexibility to the develop

ment of a new elementary plan (1263a). Judges Winter and

Sobeloft thought it was improper to invite the reconsideration of

the portions of the plan already found acceptable (1295a n *)

The judgment expressed Judge Bryan’s hope that “upon re’-exam-

mation the District Court wall find it unnecessary to contravene

the principle stated . . . ” in his dissent (1304a).

1 1

The Court entered a Memorandum of Opinion and Order

(Br. A l) on August 3, 1970 in which it: rejected again the

majority board plan; rejected the HEW plan as unconsti

tutional, and unreasonable in the context of Charlotte;

accepted as constitutional and reasonable the originally

ordered plan, the minority board plan and the preliminary

Finger plan; and continued in effect his previous order of

February 5, 1970 but allowing the board to choose to oper

ate under one of the other plans found acceptable by the

court if such a decision were made and presented to the

court in writing before noon on August 7, 1970.16

The school board, at a meeting on August 6, 1970 decided

not to exercise any of the options offered by the order of

August 3 and to appeal and seek a stay in this Court and

in the court of appeals (Br. A40). Upon receiving the

report the court ordered the court ordered plan of Feb

ruary 5 be implemented (Br. A39).

4. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg County School

System in 1968-69

In March of 1969, the plaintiffs presented to the district

court detailed evidence about the school system, such as the

number and location of the schools, the grades served, the

kinds of programs offered, the achievement of the students

in the different schools, the racial distribution o f students

and faculties in the system, and the changes which had

occurred over the years. The plaintiffs also showed by

expert testimony the rigid racial segregation of the popula

tion in Charlotte and in Mecklenburg County and its causes.17

16 The court also allowed the board to close rather than integrate

the Double Oaks School (black). There had been evidence presented

at the hearing that it is difficult to get buses to the school although

buses served the school during the 1969-70 school year.

17 See the testimony of Charles L. Green (15a-27a), Daniel O.

Henningan (28a-57a), Paul R. Leonard (57a-64a) and Yale Rabin

(174a-241a). And see the testimony of defendants’ witness, W il

liam E. McIntyre (251a-284a).

1 2

The court carefully analyzed the voluminous evidence

before it. Over the course of the litigation below, the dis

trict court made extensive findings of fact.18 Each succeed

ing order reflects a comprehensive analysis of new sub

missions of evidence by the parties and the cumulative

evidence already before the court. The court o f appeals

has accepted the district court’s findings (1262a).19

Judge McMillan’s first opinion on April 23, 1969, gave

a detailed description of the school system, the community

which it serves and the extent of racial segregation within

the schools (285a). We only summarize here some of the

salient facts contained in the April opinion.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg' school system serves more

than 84,000 pupils residing in the city of Charlotte and

Mecklenburg County. In April, 1969, there were 107 schools,

including 76 elementary schools (grades 1-6), 20 junior

high schools (grades 7-9) and 11 senior high schools (grades

10-12). The system employed approximately 4,000 teachers

and nearly 2,000 other employees. The racial composition

of the students in the system was approximately 71% white

and 29% black. The residential patterns of the county were

sufficiently integrated so that most of the county school

zones included both black and white students. Ho all-black

schools remained in the County. In the City, however, the

18 Significant findings are contained in eight of the orders leading

to the decision of the court of appeals: Opinion and Order, April

23, 1969 (285a); Opinion and Order, June 20, 1969 (448a); Order

June 24, 1969 (459a); Order, August 15, 1969 (579a); Memoran

dum Opinion, November 7, 1969 (657a); Opinion and Order, De

cember 1, 1969 (698a); Order, February 5, 1970 (819a); Supple

mental Findings of Fact, March 21, 1970 (1198a) ; and Further

Findings, etc. (1259a).

See also the most recent Memorandum of Opinion and Order

August 3, 1970 (Br. A l) .

19 The most recent findings (Br. A l) , of course, have not been

reviewed by the court of appeals.

1 3

residential areas were and are generally segregated by

race,20 and most schools were racially identifiable.

During the 1968-69 school year, students were assigned

to the schools under the same plan as approved by the dis

trict court in 1965—initial assignments by geographic zones

with freedom of transfer restricted only by school capac

ities.

The court found that 14,000 of the 24,000 black students

in the system were attending schools which were at least

99% black (303a).21 The court further found that most of

the desegregated city schools were in transition from a

previously all-white enrollment to all-black (302a). Seven

schools which served 5,502 white pupils and no black pupils

in 1954, served 5,010 pupils of which 35% were black in

1965. In 1968 they served 5,757 students, 81% of whom

were black.

The school system had been growing at approximately

3,000 students per year, requiring an on-going school con

struction program. With few exceptions, the size and place-

20 Most of the evidence concerning residential segregation was

produced at the March 1969 hearings. (See note 17, supra.) The

April order describes the housing patterns and some of the forces

which created them. The matter was examined again in subsequent

orders, particularly the Order of November 7, 1969 (657a). The

court’s conclusion was that housing segregation in Charlotte has

been substantially determined by governmental action.

21 In June, after further analysis of the data, the court concluded

that approximately 21,000 of the 24,000 black students in the sys

tem lived within the city of Charlotte and that nearly 17,000 of

them were attending black or nearly all-black schools (459a). The

court also found that nearly 19,000 of the more than 31,000 white

elementary students attended schools which were nearly all-white.

(There are only 150 black students attending these schools.) More

than one-half of the 14,741 white junior high school students at

tended schools with a total blaek population of 193 (453a).

1 4

ment of the recently constructed schools produced either

| all-white or all-black new schools.22

The court found faculties segregated. The great major

ity of the 900 black teachers were teaching in black schools.

There was less than one white teacher per black elementary

school. The two black high schools had teaching staffs more

than 90% black.

The court concluded that the board’s policies o f zoning,

free transfer and its school placement had contributed to

md continued an unlawfully segregated public school sys-

;em. It also concluded that the faculties had not been de

segregated as required by the 1965 order. The board wTas

directed to produce plans for the active desegregation of

he pupils and faculties by May 15, 1969.

On appeal, Judge Butzner agreed that the system was

unlawfully segregated in April of 1969:

“Notwithstanding our 1965 approval of the school

board’s plan, the district court properly held that the

board was operating a dual system of schools in the

light of subsequent decisions of the Supreme Court

. . .” (1263a-1264a).23

The district court further found that the impact of seg

regation on black students in the system had resulted in

the denial of equal educational opportunities. Comparative

test results showed a wide disparity in achievement between

students attending all-black schools and students attending

22 The new black schools were generally “walk-in” schools while

the white schools were placed some distance from the areas which

they serve (1203a-1204a),

23 Both Judges Sobeloff and Winter concurred in this conclusion

(1279a, 1295a).

1 5

white and integrated schools (857a-859a, 702a-704a, 1206a-

1207a).24

The court also found that the residential segregation was

far from benign or de facto. The school board by gerry

mandering zone lines (455a-456a) and other practices, to

gether with the activities of other governmental agencies,

had had a significant impact upon the creation of Char

lotte’s ghetto. Again, the three circuit judges subscribing

to the plurality opinion and Judges Sobeloff and Winter

concurred in these findings. As Judge Butzner summarize^

The district judge also found that residential pat

terns leading to segregation in the schools resulted in

part from federal, state and local governmental action.

These findings are supported by the evidence and we

accept them under familiar principles o f appellate

review. The district judge pointed out that black resi

dences are concentrated in the northwest quadrant of

Charlotte as a result of both public and private action.

North Carolina courts, in common with many courts

elsewhere, enforced racial restrictive covenants on

real property [footnote omitted] until Shelley v. Krae-

mer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) prohibited this discriminatory

practice. Presently the city zoning ordinances differ

entiate between black and white residential areas.

Zones for black areas permit dense occupancy, while

most white areas are zoned for restricted land usage.

The district judge also found that urban renewal

projects, supported by heavy federal financing and the

active participation of local government, contributed

to the city’s racially segregated housing patterns. The

school board, for its part, located schools in black resi

dential areas and fixed the size of the schools to accom

24 The court reviewed the most recent data in July, 1970 and

found wide disparities again (Br. A l) .

1 6

modate the needs of immediate neighborhoods. Pre

dominantly black schools were the inevitable result

(1264a).

In addition to the activities of the governmental agencies

producing the discriminatory zoning (297a, 1229a) and the

urban renewal programs (297a, 1229a) mentioned by Judge

Butzner, there was substantial evidence showing that long

range planning by the City Council projects present segre

gation into the future (1229a), that public housing officials

had overtly discriminated until recent years and have re

inforced racial segregation by their site selection (1229a)

and that those officials responsible for planning and build

ing streets and highways have created racial barriers. (See,

generally testimony of Yale Rabin (174a-241a)).

There was also significant testimony concerning “ private”

individual and institutional forces which have kept blacks

out of white residential areas. The Rev. Daniel 0. Henni-

gan, a black realtor testified at length concerning the enor

mous difficulties he had experienced over a period of four

years in becoming the first—and so far only—black member

on the Charlotte Board of Realtors. He finally secured

membership by agreeing not to seek participation in Char

lotte’s multiple listing service. He also told of instances

where he had negotiated the purchase of land in white

areas but was unable to proceed because funds were denied

his clients by the lending institutions (28a-57a).

5. The Schools in 1969-70

During the 1969-70 school year the schools were again

operated under the board’s 1965 desegregation plan as

modified in its submission to the court in July 1969. The

modifications provided for the transportation of 4,245 in

ner-city black students to outlying white schools. Of these

1 7

children 3,000 were to come from 7 schools which were to

be closed and 1,245 from overcrowded black schools. The

board also proposed some further faculty desegregation but

would retain all other racially discriminatory features as

found by the court in April. The board did propose, how

ever, to study its building programs and such measures as

altering attendance lines, pairing, clustering and other

techniques in order to develop a comprehensive desegre

gation plan for the future.

The plaintiffs had objected to the proposal on the grounds

that it left many schools segregated for yet another year

and placed the full burden of desegregation upon black

children.

The court, in an order entered on August 15, 1969 (579a),

approved the proposed pupil reassignments for the 1969-70

school year “ only (1) with great reluctance, (2) as a one

year temporary arrangement and (3) with the distinct

reservation that ‘one-way bussing’ plans for the years after

1969-70 will not be acceptable.” The board was ordered to

file a third plan by November 17, 1969, “making full use

of zoning, pairing, grouping, clustering, transportation and

other techniques . . . having in mind as its goal for 1970-71

the complete desegregation of the entire system to the

maximum extent possible” (591a).25 26

Upon application of defendants, the court modified the

August 15 order on August 29 to allow for the reopening

of a black inner-city school to serve up to 600 inner-city

children who chose not to be transported to suburban white

schools (593a).

25 The board explicitly refused to follow these directives. Each

of the next two plans submitted by the board rejected the techniques

of “pairing, grouping [and] clustering.” See n. 29, infra. A simi

lar directive of the court of appeals has also been ignored (Br. A l) .

1 8

The plan did not accomplish what was promised. The

court later found that “ the ‘performance gap’ is wide”

(659a).

In substance, the plan which was supposed to bring

4,245 children into a desegregated situation had been

handled or allowed to dissipate itself in such a way

that only about one-fourth of the promised transfers

were made; and as of now [March 21, 1970] only 767

black children are actually being transported to sub

urban white schools instead of the 4,245 advertised

when the plan was proposed by the board (1226a).

In the November, 1969 Memorandum Opinion (657a) the

court set out in detail the racial characteristics of the

school system during the 1969-70 school year (658a.-663a).

The court concluded that there had been no real improve

ment from the segregated situation found during the pre

vious school year.

Of the 24,714 Negroes in the schools, something

above 8,500 are attending “white” or schools not readily

identifiable by race. More than 16,000, however, are

obviously still in all-black or predominantly black

schools. The 9,216 in 100% black situations are con

siderably more than the number of black students in

Charlotte in 1954 at the time of the first Brown deci

sion. The black school problem has not been solved.

The schools are still in major part segregated or

“dual” rather than desegregated or “ unitary” (661a).

Analyzing the same figures in a later order (698a) the

court pointed out that “Nine-tenths of the faculties are

still obviously ‘black’ or ‘white.’ Over 45,000 of the 59,000

white students still attend schools which are obviously

white” (702a).

The court also determined that the free transfer provi

sion in the board’s plan negated any progress which the

19

July plan might have produced (662a).26 It also found that

attempts to desegregate the schools by altering attendance

lines would continue to fail as long as students could exer

cise a freedom of choice (662a-663a).

The court of appeals shared Judge McMillan’s view that

the system was still segregated during the 1969-70 school

year (1266a, 1275a).

6. The Plan Ordered by the District Court in

Feburary, J97027

In the decision of December 1, 1969 (698a) in which the

court announced that an educational consultant would be

appointed, 19 principles were stated for his guidance (708a-

713a). Dr. Finger’s instructions included “ all the black

and predominantly black schools in the system are ille

gally segregated . . .” (711a); “ efforts should be made to

reach a 71-29 ratio in the various schools so that there will

he no basis for contending that one school is racially dif

ferent from the others, hut . . . variations from that norm

26 The court had made similar findings in June:

Freedom of transfer increases rather than decreases segrega

tion. The School Superintendent testified that there would be,

net, more than 1,200 additional white students going to predom

inantly black schools if freedom of transfer were abolished

(453a).

Moreover, during the choice period prior to the 1969-70 school year,

just two white students out of 59,000 elected to transfer to black

schools and only 330 black students out of 24,000 chose to transfer

to white schools (I'd.).

27 A portion of the February order was stayed by the court of

appeals on March 5 (922a) and the remainder by the district court

on March 25 (1255a).

The order was reinstated by this Court on June 29 (1320a)

pending further proceedings in the district court.

On August 3, 1970 the district court continued this Court’s order

in effect subject to options made available to the board for elemen

tary school assignments if exercised on or before August 7, 1970

(Br, A l ) . Since the board declined to exercise any of the options,

the court, on August 7, 1970 directed the court ordered plan of

February 5 be implemented (Br. A39).

2 0

may be unavoidable” (710a); “bus transportation to elimi

nate segregation [and the] results of discrimination may

validly be employed” (710a); and “pairing, grouping, clus

tering, and perhaps other methods may and will be con

sidered and used if necessary to desegregate the schools”

(712a).

Dr. Finger’s work is described in the Supplemental Mem

orandum of March 21, 1970 (1221a):

Dr. Finger worked with the school board staff mem

bers over a period of two months. He drafted several

different plans.28 When it became apparent that he

could produce and would produce a plan which would

meet the requirements outlined in the court’s order

of December 1, 1969, the school staff members pre

pared a school board plan which would be subject to

the limitations the board had described in its November

17, 1969 report.29 The result was the production of two

plans— the board plan and the plan o f the consultant,

Dr. Finger.

The detailed work on both final plans was done by

the school board staff (1231a).

Both plans were presented to the court.30

a. High Schools— The school staff had developed a plan

which produced a white majority of at least 64% in each

28 One of his preliminary plans was introduced and described at

the July, 1970 hearing (Br. A l) .

29 The board’s two most significant limiting factors were: (1) Re

zoning was the only method to be employed; the board rejected

such techniques as pairing, grouping and clustering; (2) a school

sought to be desegregated would be at least 60% white; thus, the

board’s plan for elementary schools produced some schools between

57% and 70% white, eight schools 1% to 17% white, two schools

0% white and no schools between 18% and 58% white.

The court of appeals found as the district court had that these

limiting factors were improper (1275a-1276a).

30 Description of the plans are found in several of the decisions

below. See, Order, February 5, 1970 (819a, 825a-827a) and tables

2 1

of the ten high schools including the all-black West

Charlotte High School (see Exhibit B, 829a). The board

accomplished this result by restructuring attendance lines.

Dr. Finger’s proposal used the board’s new zones and as

signed an additional 300 pupils from a black residential

area to Independence High School which would have had

only 23 black students under the board’s plan. Judge

McMillan adopted the Finger modification. This portion

of the plan was approved on appeal. Judge Butzner wrote:

The transportation of 300 high school students from

the black residential area to suburban Independence

School will tend to stabilize the system by eliminating

an almost totally white school in a zone to which other

whites might move with consequent “ tipping” or re-

segregation of other schools (1273a).

b. Junior High Schools—During the 1969-70 school year

the board operated 19 junior high schools. Five were all or

predominantly black; eight were more than 90% white.

(See Exhibit D, 830a.) The board, by rezoning eliminated

several of the black schools. One school, however, Pied

mont, remained 90% black. Additionally, four schools would

be more than 90% white.81

Dr. Finger devised a plan which would integrate all the

junior high schools. Twenty of the schools would have

white populations ranging from 67% to 79% and the re- 31

(829a-839a) ; Supplemental Findings, March 21, 1970 (11.98a,

1208a-1214a); Supplemental Memorandum, March 21, 1970 (1221a,

1231a-1234a) ; Opinion of Court of Appeals (1262a, 1268a-1269a).

See also the Memorandum of Opinion and Order, August 3, 1970

(Br. A l) .

31 Two new junior high schools are scheduled to open for the

1970-71 school year. Both proposed plans contemplate assigning

students to these new schools. It is significant that under the board

plan one of the schools would be 100% white and the other 91%

white (830a).

2 2

maining school would be 91% white. The plan employed

rezoning and satellite zones.32

The district court approved of the board’s plan except

as to Piedmont, and gave the board four options: (1) re

zoning to eliminate the racial identity of the remaining

black school, (2) two-way transportation of pupils between

Piedmont and white schools, (3) closing Piedmont, or (4)

adopting the Finger Plan. The board reluctantly chose to

employ the Finger Plan.

Judge Butzner found the plans for junior and senior

high schools by use of satellite zones together with trans

portation “a reasonable way of eliminating all segregation

in these schools” (1273a).

c. Elementary Schools— The board in restructuring at

tendance lines for the 76 elementary schools was unable

to affect a majority of the students attending racially iden

tifiable schools. As the court of appeals observed, “ Its

proposal left more than half the black elementary pupils

in nine schools that remained 86% to 100% black, and

assigned about half of the white elementary pupils to

schools that are 86% to 100% white” (1269a; see Exhibit

H, 832a-834a).

The Finger Plan also employed the board’s rezoning. 27

schools were rezoned, and 34 schools were desegreated by

clustering and pairing with transportation.33 Judge Mc

Millan described the plan:

Like the board plan, the Finger plan does as much by

rezoning school attendance lines as can reasonably be

accomplished. However, unlike the board plan, it does

not stop there. It goes further and desegregates all

the rest of the elementary schools by the technique of

grouping two or three outlying schools with one black

32 A “satellite zone” is an area which is not contiguous with the

main attendance zone surrounding the school.

33 The designated clusters are shown in Exhibit K (838a-839a).

The zones of ten schools remained substantially unchanged.

2 3

inner city school; by transporting black students from

grades one through four to the outlying white schools;

and by transporting white students from the fifth and

sixth grades from the outlying white schools to the

inner city black school.

The “ Finger Plan” itself . . . was prepared by the

school staff. . . . It represents the combined thought of

Dr. Finger and the school administrative staff as to a

valid method for promptly desegregating the elemen

tary schools. . . .” (1212a-1213a)

Under the plan the elementary schools would be from 60%

to 97% white with most of the schools about 70% white.

(See Exhibit J, 835a-837a.)

Judge McMillan found the board plan to be inadequate

and directed that the Finger Plan or some other plan

which would accomplish similar results be implemented.

The court of appeals agreed that the board plan was

unacceptable. “ The district court properly disapproved

the school board’s elementary school proposal because it

left about one-half of both black and white elementary

pupils in schools that were nearly completely segregated”

(1275a). The court of appeals, however, decided that the

board should not be required to undertake the additional

transportation necessitated by the Finger Plan (1275a)

and directed further proceedings for the development of

another plan (1277a).

d. Transportation— The district court’s order required

additional transportation to be provided. The plurality

opinion approved of the increments of transportation to

accomplish the junior and senior high assignments (1273a)

but determined that the elementary school busing appeared

too extensive (1276a).

During the 1969-70 school year, the board operated 280

school buses transporting 24,737 of its 84,000 students.34

34 Judge McMillan made detailed and elaborate findings concern

ing the extent and cost of busing in the Charlotte system, the state

2 4

The board reported (619a) the number of children trans

ported, by grade level, as follows:

Pre-school 599

Elementary 10,441

Junior High 8,989

Senior High 4,708

Another 5,000 students rode public transportation at a

reduced fare (1214a). The average annual cost per child

was about $20.00 or about $475,000.00 out of a total budget

of about 57 million dollars, almost all of which was reim

bursed by the state.35 The buses averaged 1.8 one-way trips

and the country, in his Supplemental Findings of March 21, 1970

(1198a). (See also Further Findings, etc. of April 3, 1970

(1259a)). The court had examined the transportation system in

previous decisions as well (306a-307a, 449a-450a, 822a-823a).

Similar evidence was presented at the July, 1970 hearing with

resulting findings by the court (Br. A l) . These additional findings

are discussed below.

35 See Further Findings, etc., April 3, 1970 (1359a-1260a). The

district court had originally understood the average cost to be

about $40.00 per pupil (306a-307a, 1200a). The state reimburses

local school boards for operating expenses for transportation for

those students who are eligible under state law. The original cost

of the bus is borne by the local board but the state replaces worn

out buses (1259a-1260a).

During 1969-70 and previous years, pupils eligible for trans

portation were those children who lived more than iy 2 miles from

school and who lived either in the county or in portions of the city

which had been annexed since 1957. Additionally, the state paid

the transportation costs for children who lived within the pre-1957

city limits who attended schools outside of the pre-1957 limits

(1203a).

For the 1970-71 school year, as a result of a decision in an unre

lated case, Sparrow v. Gill, 304 F. Supp. 86 (M.D. N.C. 1969)

(3-judge court), the State Board of Education has directed each

school system either to offer transportation (at state rather than

local expense) to all city children living more than 1% miles from

the school to which they are assigned or to no children living within

the city limits.

Thus all of the children to be bused under the court approved

plan would be eligible for transportation at state, rather than local

expense. (See, Br. A l) .

2 5

per day carrying an average of 83.2 students, averaging

40.8 miles (1200a).36 37

Judge McMillan’s Findings in March (which were re

affirmed after 8 days of hearings in July, 1970) as ac

cepted by the court of appeals show the added transporta

tion under the plan ordered on February 5 to be:

No. of

Pupils

No. of

Buses

Operating'■

Costs

Senior High 1,500 20 $ 30,000

Junior High 2,500 28 50,000

Elementary 9,300 90 186,000

Total 13,00 138 $266,000

The initial one-time38 capital outlay to purchase new

buses would be $745.200.39 However, it was discovered at

36 The overall figures for the state show a higher percentage of

students riding buses than in Charlotte. During the 1968-69 school

year about 55% of all students in North Carolina rode buses to

school; 70.9% were elementary students (1199a). (Elementary

students are defined by the state for these purposes as students in

grades 1 through 8.)

37 These operating cost figures are as determined by the court of

appeals (1269a) by applying the district court’s Further Findings,

etc. of April 3, 1970 (1259a) to its Supplemental Findings of

March 21, 1970 (1198a). Operating costs are reimbursed by the

state.

The board had claimed much greater increases in the extent and

cost of additional busing, but the district court, after carefully

analyzing the data, found the board’s figures to be exaggerated

(see “Discount Factors,” (1214a-1216a). The court’s findings are

also consistent with the transportation requirements projected by

the board for its plan to transport 3,000 Negro children to the

suburbs for the 1969-70 year (Exhibit E, 491a).

38 Obsolete buses are replaced by the state. See note 35, supra.

39 The district court observed that there was at least 3 million

dollars worth of vacant school property which had been abandoned

pursuant to the 1969-70 desegregation plan (1219a) and which, as

the board had pointed out in its report in the summer of 1969,

could be disposed of to produce necessary “desegregation” funds

(Exhibit E, 491a).

2 6

the recent hearings that the board has on hand 107 buses

not now being used to transport children to school.

14. Up until the July 15, 1970 hearings, the defen

dants had allowed the court to believe they only had

280 busses plus a few spares. On the last day of the

hearing, however (July 24, 1970), some amazing testi

mony was developed on cross-examination of the wit

ness J.W. Harrison, the Transportation Superinten

dent. He testified and the court finds as facts that in

addition to the 280 “ regular” busses, the Board’s bus

assets include at least the following:

(i) Spare busses ................................... 20

(ii) Activity busses (each driven less

than 1,000 miles a year) ................. 20

(iii) Used busses replaced by new ones

in 1969-70 ..... 30

(iv) New busses currently scheduled

for replacement purposes and ex

pected to be delivered in near

future ................................................. 28

Total: 107

(Br. A 18).

Moreover, the court found that since “ early 1970 . . . there

were 75 new busses available to the local school system

if they wanted them, out of the 400 new busses then held

by the state” and that the 400 second-hand busses in the

state are “available on loan, without cost, for local school

boards to use in 1970-71” that “could be safely used”

(Br. A 1).

Thus no initial capital expenditures for busses is re

quired of the local board.

2 7

“No capital outlay will be required this year to

comply with the court’s order. The School Board

and the county government have ample surplus and

other funds on hand to replace with new busses as

many of the used busses as 1970-71 experience may

show they actually need” (Br. A 1).

And, again, operating costs are borne by the state.

The board itself had proposed the busing of 4,200 black

inner-city children for the 1969-70 school year to outlying

suburban schools as a desegregation measure (584a-586a).

The board’s February 2 plan proposes to bus approxi

mately 5,000 additional students, about half of whom are

elementary pupils. A major portion of this busing is within

the City (1217a, 1270a, n. 4). Moreover, there is nothing

novel about city children riding school busses. Children

living in the city but outside of the 1957 city limits have

been bused. Many city boards of education, such as Greens

boro, have provided transportation for all city children

living more than lVz miles from school with local funds.

The present State Superintendent of Public Instruction,

his predecessor and the prestigious 1969 Report of the

Governor’s Study Commission on the Public School System

of North Carolina had all recommended that transportation

be provided for children, city as well as rural, on an equal

basis (1201a-1202). State policy for the 1970-71 school

year is that all city children living more than l :1/2 miles

from school will be eligible for transportation at state

expense.

The bus trips required for the paired elementary schools

would be straight-line non-stop trips (1205a), would be

shorter and would take less time than the average bus trip

in the sytem or in the state (1199a, 1205a).

3 4 ______

(f) The average one-way bus trip in the system

today is over 15 miles in length and takes nearly

an hour and a quarter. The average length of the

one-way trips required under the court approved plan

for elementary students is less than seven miles, and

would appear to require not over 35 minutes at the

most, because no stops will be necessary between

schools (1215a).40

Busing was a technique employed by the board to main

tain its dual system as recently as 1966 (1200a); even

today, school buses transport white students to outlying

white schools while Negro students walk to their all-black

schools (1203a-1204).

Judge McMillan’s most recent memorandum includes

significant findings concerning transportation. The ex

haustive evidence on transportation presented in July veri

fied beyond question the court’s conclusions of March. It

also revealed, even more clearly, the gross exaggerations

of the Board’s transportation estimates for all desegrega

tion plans. Among the more pertinent findings are:

1. “ In North Carolina the school bus has been used

for half a century to transport children to segregated

consolidated schools” (Br. A16).

2. The state now authorizes transportation at state

expense for all city children living more than a mile

40 The court later explained how these figures were developed:

The average straight line mileage between the elementary

schools paired or grouped under the “cross-bussing” plan is

approximately 5% miles. The average bus trip mileage of

about seven miles which was found in paragraph 34(f) was

arrived at by the method which J. D. Morgan, the county

school bus superintendent, testified he uses for such estimates

—taking straight line mileage and adding 25%. (Emphasis in

original; 1215a.)

2 9

and a half from school, causing a significant increase

in the number of children riding school busses in North

Carolina from the 55% who were bussed during the

1968-69 school year (Br. A16).

3. “ School bus transportation is safer than any

other form of transportation for school children” (Br.

A16).

4. There were 17 busses carrying 700 four and five

year old children to child development centers on one

way trips ranging from seven to thirty-nine miles dur

ing the 1969-70 school year (Br. A18, A24).

5. The Board’s cost “ ‘estimates,’ when heard against

the actual facts, border on fantasy!” (Br. A24). Its

projections do not, as claimed, reflect the Board’s ex

perience in transporting inner-city black children to

outlying white schools for the 1969-70 school year.

“ [T]he evidence [shows] for example . . . that one

[such] ‘desegregation bus’ (Bus #23, Exhibit 54)

transported 99 children daily among schools as

remote as Northwest Charlotte (9th and Bethune)

on the one hand and Sharon Elementary and

Beverly Woods Elementary on the other, with

the driver then going on in the bus to South High

School” (Br. A22).41

6. There is an emple supply of busses, new and

used, money and drivers to implement the court order

(Br. A18-A20, A26).42

41 The defendants estimate for all plans are based upon the as

sumption that one bus will make one trip to one school with one

load of 45 or less children (Br. A21-A22).

42 The court also found to be without basis the Board’s claim that:

elementary children should not ride buses ( “ There may be more

first graders than children of any other age riding school busses”

(Br. A 24)) ; that additional buses will unduly clog traffic in Char

lotte (Br. A 2 5 ); and that it would unduly disrupt the system if

3 0

7. Other Elementary Elans Reviewed by the

District Court in July, 1970il!L

Judge McMillan reviewed and compared five elementary

plans at the hearings in July, 1970: (1) The majority

board plan which he had rejected in February and which

the court of appeals had rejected; (2) the Finger plan as

ordered in February, 1970; (3) the minority board plan

supported by four of the nine members of the board;

(4) another plan which Dr. Finger had prepared when

acting as court consultant; and (5) the HEW plan.

a. The Majority Board Plan— The court was of the

opinion that the court of appeals had required the board

to prepare and present another plan. The board chose

not to do so, but relied again upon its February submis

sion. Judge McMillan was not persuaded that he could

approve a plan which left over half of the black and white

elementary children in racially identifiable schools and

which had been rejected by the court of appeals (Br. A27).

b. The HEW Plan— This plan was developed by a team

of four HEW officials. They did not consult with or seek

the assistance of the local staff in the preparation of the

plan. The team was lead by Mr. Henry Kemp, recently

hired by HEW, who had no previous experience as an

educator with a school system of over 6,000-7,000 students.

Charlotte was Mr. Kemp’s first assignment by HEW to

prepare a desegregation plan. His principal assistant was

it were necessary to stagger the hours of school to simplify trans

portation problems ( “ The schools already operate on staggered

schedules. . . . The court finds that staggered opening and closing

hours for elementary schools, and arrangement of class schedules

of bus drivers for late arrival and early departure are facts of

life which will not be eliminated by desegregation of the schools”

(Br. A25-A26).)

42a At the time of the preparation of this brief, the July, 1970

proceedings have not yet been transcribed.

3 1

Mr. John Cross, a young lawyer who also had never

worked upon a complete desegregation plan for a city or

metropolitan school system.

The plan used the newly created zones o f the majority

board and Finger plans and then created several contigu

ous clusters each containing a black school with two or

more rezoned desegregated schools with each school serv

ing all the students within the cluster for 1, 2 or 3 grades.

It left two schools all black/3 The schools which had been

desegregated by rezoning would therefore have a signifi

cantly greater black student population than under the

Finger plan.