State of Louisiana v. Rev. B. Elton Cox Brief on Behalf of Defendant-Appellant and in Support of Application for Supervisory Writs

Public Court Documents

May 3, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State of Louisiana v. Rev. B. Elton Cox Brief on Behalf of Defendant-Appellant and in Support of Application for Supervisory Writs, 1963. ac9943c8-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d166c35d-ef48-435f-8f16-30fc60b01d50/state-of-louisiana-v-rev-b-elton-cox-brief-on-behalf-of-defendant-appellant-and-in-support-of-application-for-supervisory-writs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

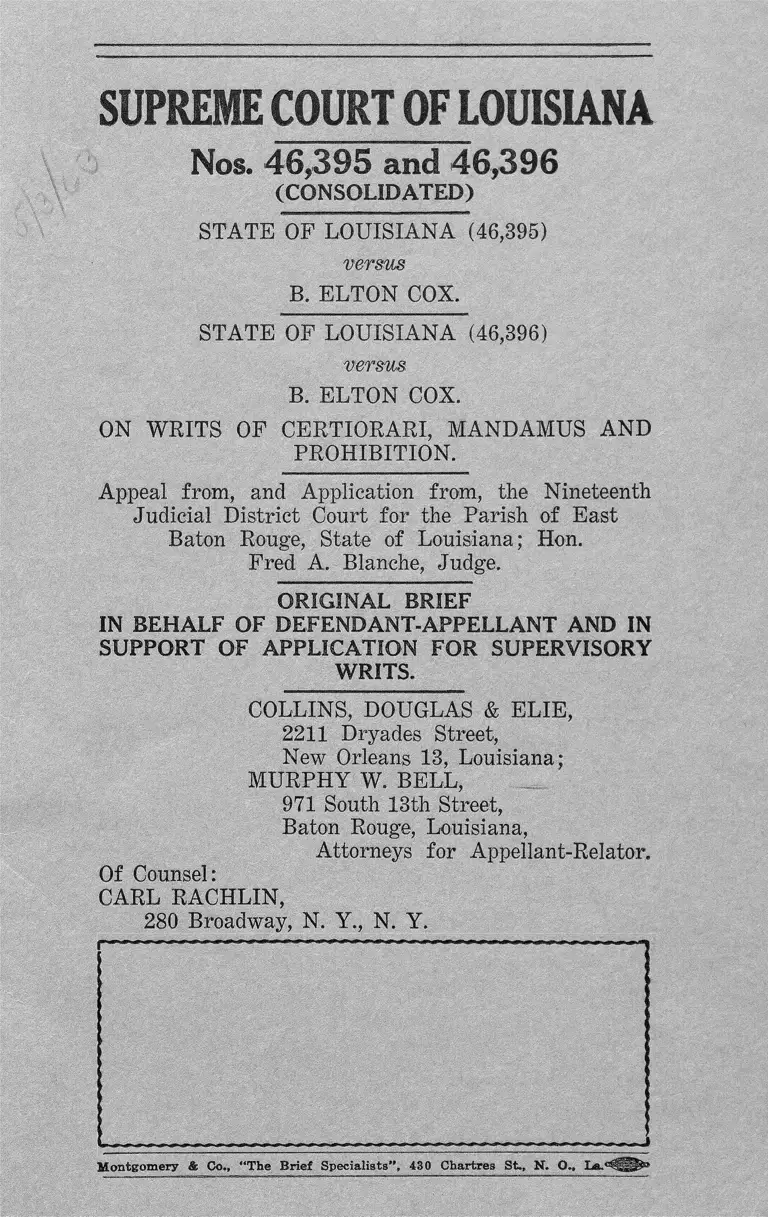

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

Nos. 46,395 and 46,396

(CONSOLIDATED)

STATE OF LOUISIANA (46,395)

versus

B. ELTON COX.

STATE OF LOUISIANA (46,396)

versus

B. ELTON COX.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI, MANDAMUS AND

PROHIBITION.

Appeal from, and Application from, the Nineteenth

Judicial District Court for the Parish of East

Baton Rouge, State of Louisiana; Hon.

Fred A. Blanche, Judge.

ORIGINAL BRIEF

IN BEHALF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT AND IN

SUPPORT OF APPLICATION FOR SUPERVISORY

WRITS.

COLLINS, DOUGLAS & ELIE,

2211 Dryades Street,

New Orleans 13, Louisiana;

MURPHY W. BELL,

971 South 13th Street,

Baton Rouge, Louisiana,

Attorneys for Appellant-Relator.

Of Counsel:

CARL RACHLIN,

280 Broadway, N. Y., N. Y.

Montgomery & Co., “ The Brief Specialists” , 430 Chartres St., N. O., La.4

SUBJECT INDEX.

Page

STATEMENT OF JU RISD ICTIO N ................... 1

PRINCIPLES OF L A W ........................................ 3

STATEMENT OF F A C T S .................................... 5

SPECIFICATION OF E R R O R S ......................... 8

ARGUMENT ........................................................... 9

CONCLUSION ......................................................... 62

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ........................... 63

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES CITED.

U. S. Constitution:

Sixth Amendment................................................ 17, 31 53

Fourteenth Amendment.......................................... 3

Louisiana Constitution:

Art. 1, Sec. 1 0 ........................................................ 9, 31, 54

Art, 7, Sec. 2 ............................................................. 2

Art. 7, Sec. 10, paragraph 7 ................................. 1

Statutes:

R. S. 14:100.1 ....................................................... 9,53,57

R. S. 14:103 ............................................................. 35,37

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Statutes:

Page

R. S. 14:103.1 ............................................8,35,36,37,

38, 39, 46, 49

R. S. 15:2 ................................................................ 53,54

R. S. 15:5 ....................................................... .. 53, 54

R- s. 15:227 ...................................................................9, 31,53,54

Cases:

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 (1953) .......... 25

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1952 ) . . . .26, 27, 30

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) .......... 11

Brewer v. Hoxie School District, 238 F. (2d)

91 (8th Cir. 1956) ........................................ 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1954) 10, 15

Cantwell v. Conn., 310 U. S. 296 ....................... 4

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442 ............ ............ 26

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 ............................. 26, 29

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 . . 51, 60

Cochran & Sayere v. U. S., 157 U. S. 286 .......... 57

Connally v. General Const. Co., 269 U. S. 385 . 46

Ul

Cases:

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 178 S. Ct. 1401,

3 L. Ed. (2d) 5 ............................................15, 19, 20

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council, 220 F. (2d)

386 (4th Cir. 1955) ........................................ 11

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council, 123 F. Supp.

193 (D. Md. 1954) .......................................... 11,12

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council, 350 U. S.

877 (1955) ...................................................... 12

Dorsey v. State Athletic Commission, 359 U. S.

533 ..................................................................... 18

Durham v. United States, 214 F. (2d) 862 (D. C.

Cir. 1954) ......................................................... 21

Edwards v. S. Carolina, -—-U. S. — , 23 U. S. Sp.

Ct. Bulletin 919, Feb. 25, 1963 ..................... 4, 45

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 ................... 26

Ex Parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651 (1884) . . . . 29

Flemming v. South Carolina Elec. & Gas Co., 224

F. (2d) 752 (4th Cir. 1955), appeal dis

missed 351 U. S. 901 (1956) ......................... 13

Farnsworth v. United States, 232 F. (2d) 59

(D. C. Cir. 1956) ............................................ 22

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 82 S. Ct.

248 ...................................................... 37, 39, 47

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Page

iv

Cases: Page

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 ................... 44

Great No. Ry. v. Sunburst Oil & Ref. Co., 287

U. S. 358 (1932) ............................................... 21

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12 (1956) .............. 22

Hagner v. U. S., 285 U. S. 427 ........................... 57

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 ............................... 26

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81 (1943) .......... 25

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 (1961) 12

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 124 P. Supp. 290

(N. D. Ga. 1955) ............................................ 12

International Harvester Co. v. Kentucky, 234

u - S. 216 ........................................................... 51, 60

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 .............. 46

Martin v. Struthers, 318 U. S. 1 4 1 ....................... 38

Morrison v. Davis, 252 P. (2d) 102 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 356 U. S. 968 (1958) .............. 14

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347

U. S. 971 (1954) ............................................ H

Musser v. Utah, 333 U. S. 9 5 ............................... 46

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958) . . 27

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925)

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

29

V

Cases:

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896) .. 10,20

Rosen v. U. S., 161 U. S. 29 ....................... 57

Schenck v. U. S., 249 U. S. 4 7 ............................... 41

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 ....................... 4

Sharp v. Lucky, 252 F. (2d) 910 (5th Cir. 1958) 13

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) ...... 26

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 1 4 7 ....................... 51, 59

State v. Christine, 239 La. 259, 118 So. (2d)

403 (1960) .................................................... 47, 52, 59

State v. Clemmons, 243 La. 264, 142 S. (2d) 794 8

State v. Kraft, 214 La. 351, 37 So. (2d) 815

(1948) ............................................................... 52,59

State v. McQueen, 230 La. 55, 87 So. (2d) 757

(1955) 56

State v. Robertson, 241 La. 249, 128 So. (2d)

646 (1961) ......................................................... 34

State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 14 So. (2d)

778 ..................................................... 38,50,51,52,59

State v. Vanicor, 239 La. 357, 118 So. (2d) 438

(I960) 34

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Page

vi

Cases:

State v. Varnado, 208 La. 319, 23 So. (2d) 106

11!! 141 ............................................................... 33, 56

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303

(1879) ............................................................15,24,25

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ............ 10

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Comm., 334 U. S.

100 (1948) ....................................................... 25

Taylor v. Louisiana, 82 S. Ct. 1188 .............. 34,36,62

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ................... 4, 39

Traux v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33 (1915) .............. 29

U. S. v. Capital Traction Co., 34 App, D. C. 592,

19 Ann. Cas. 6 6 ................................................ 48

U. S. v. Cruishank, 97 U. S. 542, 23 L. Ed. 588 . . 32, 55

U. S. v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214, 23 L. Ed. 563 .......... 49

Warring v. Colpays, 122 F. (2d) 642 (D. C. Cir.),

cert, denied, 314 U. S. 678 (1941) ............... 22

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .............. 46, 51, 59

Other Authorities:

Desegregation and the Law (1957), by Blaustein

and Ferguson .................................................. 44

Segregation and Public Recreation (1954), 40

Va. L. Rev. 697

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES— (Continued)

Page

11

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

Nos. 46,395 and 46,396

(CONSOLIDATED)

STATE OF LOUISIANA (46,395)

versus

B. ELTON COX.

STATE OF LOUISIANA (46,396)

versus

B. ELTON COX.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI, MANDAMUS AND

PROHIBITION.

Appeal from, and Application from, the Nineteenth

Judicial District Court for the Parish of East

Baton Rouge, State of Louisiana; Hon.

Fred A. Blanche, Judge.

ORIGINAL BRIEF

IN BEHALF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT AND IN

SUPPORT OF APPLICATION FOR SUPERVISORY

WRITS.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION.

This Honorable Court has jurisdiction of this

matter by virtue of Article VII, Section 10, paragraph

2

seven, of the Louisiana Constitution, wherein it is pro

vided :

“ The Appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court

shall also extend to criminal cases on questions

of law alone, wherever the penalty of death, or

imprisonment at hard labor, may be imposed; or

where a fine exceeding three hundred dollars or

imprisonment exceeding six months has been ac

tually imposed.”

The Criminal District Court for the Parish of

East Baton Rouge in matter Number 42,200 (Supreme

Court Number 46,395) appellant was sentenced to pay a

fine of $500.00 and to serve five months in the parish

prison and in default of payment of the fine an addi

tional five months.

This Honorable Court has jurisdiction of this

matter by virtue of Article VII, Section 2, of the Lou

isiana Constitution, wherein it is provided:

“ The Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, and

each of the judges thereof, subject to review by

the court of which he is a member, and each Dis

trict Judge throughout the state including Judges

of the Civil and Criminal District Courts in the

Parish of Orleans, may issue Writs of Habeas

Corpus in behalf of any person in actual cus

tody in cases within their respective jurisdic

tions; and may also, in aid of their respective

3

jurisdictions, original, appellate or Supervisory

issue writs of Mandamus, Certiorari, Prohibi

tion, Quo Warranto, and process, and where any

of said writs are refused, the Appellate Courts

shall indicate the reasons therefor.”

The District Court for the Parish of East Baton

Rouge, Louisiana, in matter Number 42,202 (Supreme

Court Number 46,396) sentenced defendant to pay a

fine of $200.00 and to serve four months in the parish

prison and in default of payment of the fine to impris

onment for four months additional.

PRINCIPLES OF LAW.

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens

of the United States and of the state wherein they

reside. No state shall make or enforce any law

which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of

citizens of the United States; nor shall any state

deprive any person of life, liberty or property

without due process of law; nor deny to any per

son within its jurisdiction the equal protection of

the laws.

Section 1, Fourteenth Amendment, U. S.

Constitution.

Freedom of speech, which is guaranteed by the First

Amendment against abridgment by the Federal

4

Government, is also within the liberty safeguarded

by the clue process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment from invasion by the state action.

Cantwell v. Conn., 310 U. S. 296.

The streets are the natural and proper places for the

dissemination of information and opinion; and one

is not to have the exercise of his liberty of expres

sion in appropriate places abridged on the plea that

it may be exercised in some other place.

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. H7.

It is the duty of municipal authorities, as trustees for

the public, to keep the streets open and available

for movement of people and property, the primary

purpose to which the streets are dedicated; and to

this end the conduct of those who use them may

be regulated; but such regulation must not abridge

the constitutional liberty of those who are right

fully upon the streets to impart information

through speech and picketing.

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 1J+1.

Freedom of speech guaranteed by the Constitution em

braces at the least the liberty to discuss publicly

and truthfully all matters of public concern with

out previous restraint or fear of subsequent pun

ishment.

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88.

5

The Fourteenth Amendment does not permit a state

to make criminal the peaceful expression of un

popular views.

Edwards v. South Carolina., — U. S. — , 23

U. S. Sup. Ct. Bulletin 919 (Feb. 25,

1963).

STATEMENT OF FACTS.

On December 14, 1961, twenty-three Negro col

lege students were arrested while picketing several

downtown Baton Rouge retail stores in protest of racial

segregation.

On December 15, 1961, some one thousand five

hundred or more (Tr. pp. 51, 77, 269, 282, 313, 316,

355) Negro college students protested the previous day’s

arrest of the twenty-three students. At about 12 o’clock

noon, these students assembled at the old state capital

and, while walking in pairs, circled the square until

most of them had arrived. From there they went on

North Boulevard up the west side of St. Louis Street up

to the 200 block (Tr. p. 372), i. e., between Louisiana

Avenue and America Streets (Tr. p. 33), opposite the

courthouse building. At the intersection of America

and St, Louis Streets, Rev. B. Elton Cox (Tr. pp. 99,

100, 101) informed Chief of Police Wingate White:

“ We are here to demonstrate the cause of . . . the

people who you have in jail who were arrested

for picketing . . . we are going to sing some songs,

patriotic songs, say some prayers . . .”

6

Rev. B. Elton Cox further said his speech would

take seven minutes, and the whole program would take

between seventeen and twenty-five minutes. (Tr. p.

471.) To this Chief W. White said (Tr. p. 101) “ all

right you got seven minutes but no more.” After tak

ing some ten minutes (Tr. p. 104) to assemble, the

group pledged allegiance to the flag, recited the Lord’s

Prayer, sang a couple of songs and Rev. B. Elton Cox

made a non-violent speech (Tr. pp. 29, 37, 44, 63, 124,

158, 268, 302, all testimony of state’s witnesses). No

violence occurred (Tr. pp. 20, 67, 127, 262, state’s wit

nesses) ; the only violence was the confusion which re

sulted from the tear gas being thrown by the police

and the use of police dogs (Tr. pp. 93, 165). There

were no physical acts of violence towards anyone (Tr.

pp. 127, 262, state’s witness) ; in fact no arrests were

made (Tr. pp. 79, 89, 96, 329). Among other things,

Rev. B. Elton Cox said in his speech (Tr. pp. 518, 519) :

“ . . . all right. It’s lunch time. Let’s go eat.

There are twelve stores we are protesting. A

number of these stores have twenty counters,

they accept your money from nineteen. They

won’t accept it from the twentieth counter. This

is an act of racial discrimination. These stores

are open to the public. You are members of the

public. We pay taxes to the Federal Govern

ment and you who live here pay taxes to the

state.”

And at Tr. p. 19, “ . . . so go to the designated places

and sit until you are waited on . . .” (For a summary

7

of the speech, see Tr. pp. 272, 273, state’s witness Wil

liam H. Daniels.) While this orderly demonstration

(Tr. pp. 23, 44, 90, 117, 119, 124, 140, 169, 205, 237,

319, 354, 376) was going on some 150 to 200 persons of

the white race (Tr. pp. 36, 166) gathered on the court

house steps on the east side of St. Louis Street. This

was not a hostile group. (Tr. pp. 27, 28, 167.) There

were also present some 80 or 90 policemen (Tr. pp.

254, 312, 316, 355) who could handle any situation

which would have arisen (Tr. pp. 327, 329, state’s wit

ness) .

Sometime immediately before the tear gas was

thrown, the prisoners in jail started to sing. The stu

dents quickly responded with a jubilant cheer or yell.

(Tr. pp. 54, 120.) The testimony is conflicting as to

whether the speech came first on the spontaneous yell

of the students. However, Rev. B. Elton Cox had com

plete control over the students at all times. (Tr. pp. 35,

38, 107, 119, 123, 124, 257, 313, 355.) Finally, Sher

iff Bryan Clemmons said, “ . . . you have been allowed

to demonstrate. Up until now your demonstration has

been more or less peaceful, but what you are doing now

is a direct violation of the law, a disturbance of the

peace, and it has got to be broken up immediately.” (Tr.

p. 354.) Immediately thereupon the tear gas bombs

were shot, and the students dispersed in confusion.

Several hours after the demonstration Rev. Cox

was arrested at a church in Scotlandville, La., and

charged with disturbing the peace, obstructing the side

walk, obstructing justice and criminal conspiracy. The

8

defendant was tried in the Nineteenth Judicial District

Court and found guilty of obstructing justice, obstruct

ing the sidewalk and disturbing the peace. The de

fendant was acquitted of criminal conspiracy. Two of

these cases have previously been up to this Court on a

writ of habeas corpus (see Nos. 46,078, 46,079), State

v. Clemmons, 243 La. 264, 142 So. (2d) 794, wherein the

sentences were annulled and the cases remanded to allow

defendant the opportunity to take any procedural steps

necessary to protect his rights. The defendant has now

been resentenced and the two cases are here, one by

way of appeal and the other by way of writs.

SPECIFICATION OF ERRORS.

1. The trial judge committed prejudicial error when

he failed to declare the application of the statutes

unconstitutional in that here the statutes were ap

plied to deprive defendant of freedom of speech

and expression guaranteed by the First Amend

ment to the United States Constitution and of the

due process and equal protection guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution. (Bill of Exception No. 1.)

2. The trial judge committed prejudicial error when

he refused the motion to desegregate the courtroom.

( Bills of Exception Nos. 2, 8 and 4. )

3. The trial judge committed prejudicial error when

he did not hold that both L. S. A.-R. S. 14:103.1 and

9

14:100.1 were unconstitutionally vague. (Bills of

Exception Nos. 2 and 3.)

4. The trial judge committed prejudicial error when

he did not hold that both bills of information were

fatally defective in violation of the Sixth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States and

in violation of Article 1, Section 10, of the Consti

tution of the State of Louisiana, 1921, and in vio

lation of L. S. A.-R. S. 15:227, Article 227, of the

Code of Criminal Procedure. (Bills of Exception

Nos. 1, 2 and 3.)

5. The trial judge committed prejudicial error in

the disturbing the peace case, because in finding

the defendant guilty he applied the wrong standard.

6. The trial judge committed prejudicial error when

he refused the application for a bill of particulars,

and when he refused the motion to quash, the mo

tion for a new trial and the motion in arrest of

judgment. (Bills of Exception Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4.)

ARGUMENT.

I.

Racial Segregation in the Court Where Relator

W as Tried and Convicted Denied Him of a Fair

Trial in Violation of the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

We submit that the Court must recognize that

the equal protection cases of recent years indicate that

10

it is no longer constitutional for states to require that

members of different races use separate state facilities.

Such practices for many years had been sustained under

the separate but equal doctrine of Ples-sy v. Ferguson,

163 U. S. 537 (1896). However, beginning in 1954

with Brown v. Bd. of Education, 3k7 U. S. k83 (195k.),

and continuing in an unbroken line of decisions, the

Court has held that state-imposed segregation is a vio

lation of the equal protection of the laws as guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The school segre

gation cases held that in the field of public education

the doctrine of separate but equal has no place as sep

arate facilities are inherently unequal. In Brown the

Court noted an earlier case decided under the old doc

trine which held that a Negro law school was unequal

partly on the basis of “ those qualities which are incapa

ble of objective measurement but which make for great

ness in a law school.” Siveatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629,

63k (1950). The Court elaborated on this line of rea

soning when it took judicial notice of modern psycho

logical knowledge and concluded that state-imposed seg

regation on the basis of race generated a feeling of in

feriority and was thus harmful to the petitioning Negro

children. In the companion case to Brown, the Court

held segregation in the public schools of the District of

Columbia violated the due process of law protection of

the Fifth Amendment and spelled out the general ap

proach that it was to take in cases involving state-

imposed segregation when it said:

11

“ Classifications based solely upon race

must be scrutinized with particular care, since

they are contrary to our traditions and hence

constitutionally suspect.” Bolling v. Sharpe, 347

U. S. 497, 499 (1954).

This line of reasoning which regards segregated

facilities as inherently inferior has not been confined

to the field of education. Since Brown the Court has

vacated judgment in a case involving segregation in a

theatre and remanded the case “ for consideration in

light of the School Segregation Cases . . .” Muir v. Louis

ville Park Theatrical Ass’n, 347 U. S. 971 (1954). This

“ inferiority” rationale of Brown has led commentators

to argue that all racial classification of state facilities

is unconstitutional. See Blaustein and Ferguson, De

segregation and the Law (1957); McKay, Segregation

and Public Recreation, 40 Va. L. Rev. 697 (1954).

The rationale that racial distinctions are inher

ently unequal, as contained in the Brown case, has been

applied to other areas of state activity. In the field of

public recreational facilities it is now law that segre

gated facilities, despite any physical equality, violate

the equal protection of the laws. This issue was

squarely faced when the Courts o f Appeals reversed a

District Court refusal to order integration of public

beach facilities which had been grounded on the separate

but equal doctrine. Dawson v. Mayor and City Council,

220 F. (2d) 386 (4th Cir. 1955), rev’g 123 F. Supp. 193

12

(D. Mel. 1954.). The intermediate court based its deci

sion on the theory that the Brown case had overruled

the separate but equal doctrine and held:

“ It is now obvious, however, that segregation

cannot be justified as a means to preserve the

public peace merely because the tangible facilities

furnished to one race are equal to those furnished

to the other.” {Id. at 887.)

The Court reasoned that the same inequality inherent

in separate schools applied with equal force in the field

of public recreation and that any separate public facili

ties are inherently unequal. The very fact of separa

tion on the basis of race was deemed to be violative of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

Faced with the two conflicting theories of con

stitutional law, the Supreme Court affirmed per curiam

the Court of Appeals’ holding of the unconstitutionality

of the segregated facilities. Dawson v. Mayor and City

Council, 350 U. S. 877 (1955).

When a Federal District Court sustained a Ne

gro’s petition for use of municipal golf courses apply

ing the separate but equal doctrine of Plessy, the Su

preme Court remanded with an order to modify the

decree to make it conform to the principles enunciated

in Broivn and Dawson. Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350

U. S. 879 (1961) modifying 124 F. Supp. 290 (N. D.

Ga. 1955). The sequence of these cases clearly evidences

13

that the Court is not willing to allow the use of the

separate but equal rationale in place of the inherently

unequal doctrine of Brown even when the same result

would be obtained. Similarly, the required use by Negro

voters of separate registration offices has been held to

be a violation of equal protection under the Fourteenth

Amendment. Sharp v. Lucky, 252 F. (2d) 910 (5th Cir.

1958). It clearly appears, therefore, that in cases

closely analogous to the instant case it has been held

unconstitutional for the state to provide separate facili

ties to members of different races. It is illogical to say

that the same rationale should not be applied when the

state requires its halls of justice to be segregated. When

segregation in other public facilities is held to violate

the principle of equal protection only an irrational dis

tinction could exclude public courtrooms from the scope

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

It has also been held unconstitutional for the

state to require segregation by race on public trans

portation facilities. In reversing a district Court ruling

denying jurisdiction in a suit for damages against a bus

driver for making Negro plaintiff change his seat in

conformity to the law on grounds that there was no

diversity and a valid state statute, the Fourth Circuit

construed the Brown decision as invalidating the sepa

rate but equal doctrine by implication in the field of

public transportation. Flemming v. South Carolina Elec,

and Gas Co., 22h F. (2d) 752 (ith Cir. 1955), appeal

dismissed, 351 U. S. 901 (1956). A later suit for in

14

junction and declaratory judgment produced the same

result on the theory that Flemming “ plainly and fully

disposed . . of the substantive issue of the unconsti

tutionality of segregated transportation facilities. Mor

rison v. Davis, 252 F. (2d) 102 (5th Cir.), cert denied,

356 U. S. 968 (1958).

The trend and meaning of the decisions seem

clear. The state may no longer provide separate facili

ties to be segregated on the basis of race. The Court

has held such racially separated facilities to be inher

ently unequal and thus violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment. In the case at bar the state is attempting

to do the same thing. Here the Court is attempting

to segregate the races in a public courtroom. Cer

tainly the facts here of racial segregation in the public

facility of a state courtroom are no different than the

segregation which has already been condemned in other

public facilities. The rationale applicable to these other

areas applies here with even greater force, since in the

instant case the equal protection that is being denied

occurs within the halls of justice itself. It strikes peti

tioners as incongruous that they may claim their right

to ride on unsegregated transportation facilities, or to

send their children to unsegregated schools, or to spend

their time on unsegregated golf courses— but that they

are denied the right to a trial free from a state-imposed

barrier established in a courtroom.

We submit that the Court need hardly be re

minded of the inscription which graces the structure

15

housing the Supreme Court of the land. To deny peti

tioners their right to “ equal justice under law” would

indeed be anomalous when the federal courts have al

ready acted to secure the equal protection of the laws

under the Fourteenth Amendment to members of all

races in other areas of public facilities.

The Supreme Court from Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879), through Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U. S. 1, 178 S. Ct. U01, 3 L. Ed. (2d) 5, and there

after has recognized that segregation of the races im

poses a status of inferiority upon Negroes. In the case

at bar the segregation of the courtroom, under the aegis

of the judiciary itself, was a continuing testimonial

by the state that the two races were unequal. As was

noted in Brown v. Board of Education, 31p7 U. S. h.83

(1951+), the impact of segregation is greater when it is

officially sanctioned by law. The aura of inferiority

cast by the courtroom segregation is particularly sus

pect in a case like the instant case where the defendant

and all defense witnesses are Negroes. The stigma

is critical when the defendant is a militant civil rights

leader and was at the time o f his arrest speaking out

against segregation.

The whole atmosphere of a courtroom and the

procedure of a trial is designed to emphasize the neces

sity for laying aside personal convictions and to judge

each case on its merits. The solemn, orderly and for

mal procedure followed in the courtroom, the respect

16

paid to the robed judge, and the basic dignity conveyed

by the entire proceeding all aspire to this goal. Yet

this prospect is inevitably shattered once the court is

segregated— a situation condoned, if not directed, by

the judge upon whom laymen rely specifically for guid

ance. Certainly a segregated courtroom has neither

the appearance nor substance of impartiality.

The relator herein was prejudiced by the refusal

to desegregate the courtroom because the effect was to

say you are not entitled, you have no right to have per

sons of your race sit where they choose in this court.

If this be true, then how can it be said, especially in

criminal cases, that your relator had all of his rights

secured to him? How can it be said objectively that he

received the benefit of the presumption of innocence;

that the state proved beyond a reasonable doubt the

guilt of the accused; that the statute in question was

strictly construed; that the white persons who testified

for the state were not given more credence than the

Negroes who testified for the defense, and this simply

because they were white? The answer is that there

must exist a reasonable doubt that when the forms of

justice are not met, then the substance of justice can

not be met, for the one precedes the other. The rights

of any defendant are theoretically secured to him be

cause of his dignity as a human being. If this dignity

is besmirched by requiring his trial in a segregated

courtroom, the denial of a lesser right, how can it be

said truthfully that his greater rights were secured?

17

This question becomes profound when the defendant was

arrested while actively speaking out against racial seg

regation. Segregation in the courtroom cannot stand,

because justice, like Caesar’s wife, must be above sus

picion.

It is the basic position of relator that segregation

in any public facility is inherently unequal and in vio

lation of the XIY Amendment, thus when exercised in a

court of justice is for a stronger reason violative of the

XIV Amendment, It is further the position of relator

that the original Brown decision has been extended not

only to mean that segregation in public schools violates

the equal protection clause of the XIV Amendment but

to also mean that segregation in any public facility is a

violation of due process. Thus appellant in being forced

to trial in a segregated courtroom was denied a basic

civil liberty amounting to a deprivation of due process

of law.

We maintain that the Brown case, supra, has

been extended to mean that separate public facilities

for Negroes are as a matter of law a violation of their

constitutional rights. We further maintain that when

a defendant is tried in a criminal case before a judge

alone and in a segregated courtroom, this, without more,

as a matter of law denies a defendant of a fair and

public trial and is a deprivation of defendant’s rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

The gist of the Brown case, supra, says:

IS

. . we conclude that in the field of public edu

cation the doctrine of separate but equal has no

place. Separate facilities are inherently un

equal.” (Emphasis ours.)

The Brown case, supra, has been extended by the United

States district courts. In Dorsey v. State Athletic Coin

mission (1958), this was said:

“ In the School Segregation Cases, 1954, 347 U. S.

483, 74 S. Ct, 686, 98 L. Ed. 873, the Supreme

Court held that classification based on race is in

herently discriminatory and violative of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. This principle, originally stated with re

spect to children in public schools, has been ap

plied to golf courses, parks, beaches, and swim

ming pools, and buses and streetcars. The ap

plication of the principle does not depend purely

upon the fact that the school or the park is pub

licly owned, it rests on the fact that the discrim

inatory classification is enforced by state offi

cials or state agencies. The Supreme Court has

consistently defined State Action as including

action of any agency of the state at any level of

government.”

Further on the case says:

“ The Commission relies on the argument that

the rule and statute were adopted under the

state police power as a necessary measure to

19

preserve peace and good order . . . The same

argument was made in Orleans Parish School

Board v. Bush. Judge Tuttle for the Court of

Appeals for the 5th Circuit, rendered the argu

ment :

“ ‘The use of the term police power works no

magic in itself. Undeniably the States retain

an extremely broad police power, however, as

everyone knows, is itself limited by the pro

tective shield of the Federal Constitution.’ ”

The holding of the Brawn case, supra, was elaborated in

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 178 S. Ct. 14.01, 3 L. Ed.

(2d) 5. In the Aaron case the Court reiterated the prop

osition that segregated schools denied the student equal

protection of the laws and also denied him due process of

law. It is significant that in the Cooper case the School

Board had filed a petition seeking a postponement of a

plan for desegregation on the principal ground of ex

treme public hostility engendered largely by the official

actions of the governor and the Legislature o f the State

of Arkansas. The Supreme Court held that the extreme

situation which existed in Little Rock and the powerful

and continued hostility of the governmental officials

and/or ordinary citizens were not grounds for suspen

sion of the Court’s order. The Court said:

“ The right of a student not to be segregated on

racial grounds in schools so maintained is indeed

so fundamental and pervasive that it is embraced

in the concept of due process of law.”

20

Thus we see that the “ separate but equal” doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, would now appear to

have no vitality in the field of public transportation, the

field in which the doctrine was originally announced.

The Brown case and its history in the Supreme Court

would appear to force the conclusion that there now

exists a positive mandate that segregated public facili

ties are as a matter of fact unconstitutional by virtue

of the due process and equal protection of the laws

clause of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States. This is on the theory

that segregated facilities are inherently unequal and

that the forced use of them is such a deprivation of basic

civil liberty that it amounts to a denial of due process

of law.

The only serious arguments which have been ad

vanced in recent years regarding the constitutionality

of public segregation by statute or otherwise have in

large measure had as their basis the exercise of the

police power of the state to prevent public violence.

This argument falls apart when one views the Court’s

reaction to the Little Rock violence as expressed in

Cooper v. Aaron, supra. The Court says that violence

or fears of violence are not proper factors to be consid

ered in determining whether or not a given segregation

statute or custom violates the Constitution. The Su

preme Court is thus saying that individual liberty is

more important than some abstract concept of public

good.

21

The above argument is particularly strong in the

light of the following statement by the trial judge at

pages 5 and 6 of the transcript:

“ Also let the record show that it has been the

practice and custom in the East Baton Rouge

Parish Courthouse for many, many years and in

the purpose of maintaining order in the court

room separate portions are placed in the

courtroom for both colored and white . . .”

II.

The Possibility That Retroactive Effect Will Be

Given to a New Ruling Should Not Deter the

Court from Making the Ruling, for the Court

May Provide That It Will Operate Only in

Future Cases.

If it is thought that the ruling sought in this

action would create a serious problem in its retroactive

application to previously litigated cases, the Court may

limit the operation of the decision to cases arising in

the future. See Great No. Ry. v. Sunburst Oil & Ref.

Co., 287 U. S. 358 (1932); Durham v. United States,

2U F. (2d) 862, 87J (D. C. Cir. 195 i).

In the Sunburst case Justice Cardozo held that it

was not a denial of due process for a state court to

limit its overruling decision to future operation. He

concluded that the courts were not under any legal re

straint; that the question whether to apply a ruling

22

retroactively or to limit it to future cases could be re

solved in accordance with the juristic philosophies of

judges in each jurisdiction.

In this absence of legal restraint, the choice be

tween retrospective prospective application is also avail

able to the federal courts. Compare Warring v. Colpoys,

122 F. (2d) 61+2 (D. C. Cir.), cert, denied, 311+ U. S. 678

(191+1), with Farnsworth v. United States, 232 F. (2d)

59 (D. C. Cir. 1956). The Court of Appeals for the Dis

trict of Columbia, in adopting a new insanity test in

the Durham case, expressly limited the application of

the new test to future cases, saying: “ (I)n adopting

a new test, we invoke our inherent power to make the

change prospectively.” 211+ F. (2d) at 871+.

Justice Frankfurter, concurring in the free tran

script ruling of Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U. S. 12, 25-26

(1956), feared that retroactive operation of the ruling

would cause a flood of litigation and, therefore, pro

posed that the Court include an express disclaimer of

retroactive effect in its opinion. Even though the ma

jority did not disclaim the retroactive effect of the rul

ing, Justice Frankfurter nevertheless concurred in the

result. Thus, the possibility of retroactive operation

of the ruling, with its attendant difficulties, was not

enough to induce Justice Frankfurter to oppose the new

ruling.

It is submitted, therefore, that the possibility of

retroactive effect need not deter the making of a con

23

stitutionally required ruling, for retroactivity may be

disclaimed.

III.

Segregation in the Courtroom Violated the Con

stitutionally Protected Rights of the Spectators,

and Defendant Has Standing to Assert

Those Rights.

It is a universal truth that individual and group

predilections, prejudices and choices have existed and

will continue. We do not complain of this per se. What

we do complain of is that the manifestation of majority

prejudices through the use of the full panoply of state

power. What we do seek is not a “gift” unwarranted

and unmerited but a “ right” due us from those in posi

tions of trust, warranted and merited by the same rea

sons said rights are accorded members of the majority.

It is also a truth, not quite so universal, that

segregation in the courts is not fair. No amount of

legal rationalization, no matter how skillfully stated,

will be sufficient to satisfy the mind of the most illiter

ate, insignificant individual that courtroom segrega

tion is fair. The great strength of the Fourteenth

Amendment is that it prohibits use of the evil eye and

uneven hand. That unfairness exists and should be

proscribed is not the question.

In 1868 with the ratification of the Fourteenth

Amendment it may be said at the very least that the

24

gods conspired to create the circumstances resulting in

the acknowledgment, be it ever so reluctant in some

areas, of unfairness to minorities. Nineteen hundred

fifty-four brought a revitalization of the Fourteenth

Amendment, a reacknowledgment of the necessity for

enforcing its proscriptions and an answer to the ques

tion, long pending, when should Fourteenth Amend

ment proscriptions be enforced.

Too much emphasis cannot be given to the Four

teenth Amendment and the jurisprudence developed

under it. Early recognition of Negroes’ rights and the

nature it was to take was indicated by Strauder v. West

Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 308 (1880), which said:

“ The very fact that colored people are . . . denied

by statute all rights to participate in the admin

istration of the law, as jurors, because of their

color . . . is . . . a stimulant to that race preju

dice which in an impediment to securing to indi

viduals of that race, the equal justice which the

law aims to secure to all others,”

And at 100 U. S. 307-308:

“ The words of the (Fourteenth) Amendment . . .

contain a necessary implication of a . . . right,

most valuable to the colored race . . . the right to

exemption from . . . legal discrimination . . .”

Since 1879 the Supreme Court has condemned

any state action which would subject Negroes to “ legal

25

discriminations implying inferiority in Civil Society.”

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 308 (1879).

See also Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81,100 (1943) :

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of

their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a

free people whose institutions are founded on a

doctrine of equality . .

See also Takahashi v. Fish and Game Comm., 334 U. S.

100 (1948).

The Strauder case evidences a concern by the

U. S. Supreme Court about insuring judicial admin

istration which preserves to parties before the court the

equal protection of the laws.

This the Strauder case shows by the fact that

it did not require evidence of actual prejudice against

defendant. Only a prima facie showing of discrimina

tion in the selection of the jury list was required. The

line of cases since Strauder have maintained the same

requirement. These cases on the basis o f circumstantial

evidence have found denial of equal protection; a fortiori,

a denial will similarly be found where as here there

was a denial of a motion to desegregate the courtroom.

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 (1953), is an

example of the close supervision the U. S. Supreme

Court will exercise in reviewing the process of judicial

administration of a state tribunal. There different

26

colored slips were made out for the Negro veniremen,

and the judge who selected the jurymen gave uncon

tradicted testimony that he had never practiced dis

crimination in the discharge of his duty. The Court

held that the absence of Negro jurymen on the panel

constituted sufficient evidence to make out a prima facie

case of discrimination. The Court noted: “ (Obviously

that practice makes it easier for those to discriminate

who are of a mind to discriminate.” 345 U. S. at 562.

The Court’s concern with equal protection in

grand jury cases is no different. See Carter v. Texas,

177 U. S. lf.lf.2; Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584;

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282. As Justice Jackson

pointed out in his dissent in Cassell, what the Court was

concerned with was not the prejudice that might result

to the defendant, but with the judicial administration

of the state court, with a “method of enforcing the right

of qualified Negroes to serve on grand juries.” 339 U. S.

at 300. As the Court in Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400,

noted:

“ No state is at liberty to impose upon one

charged with crime a discrimination in its trial

procedure which the Constitution, and an Act of

Congress alike forbids.”

The rationale of close supervision of state court

proceedings is also evidenced by the federal review of

actions brought to enforce restrictive covenants. See

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334, U. S. 1 (1948). In Barroivs v.

27

Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1952), the action was at law,

and the relief prayed for was damages for breach of

the restrictive covenant by a white vendor. The Court

held that the judicial enforcement which violated the

equal protection of the laws in a court of equity applied

as well when an action on the covenant was prosecuted

in a law court. The Court said: “ The result of the

Sanction by the State would be to encourage the use of

the restrictive covenants . . ” Id. at 254. That rationale

is equally applicable here.

To the argument that the instant case was a mis

demeanor, triable by the judge alone, therefore there is

a presumption that the trial was fair, we urge that this

presumption is a rebuttable one that was overcome by

the fact that the Court demonstrated its inability to

conduct a fair trial by its failure to grant the motion

to desegregate the courtroom.

IV.

Relator Has Standing to Assert the Denial of

Rights to Others.

Relator, while not being a spectator per se, has

standing to assert the rights of other spectators. One

group of cases indicated that there is standing if there

is sufficient nexus, or identity between the party whose

right is being asserted and the party who is before the

court. In N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 (1958),

the association was held to have standing to assert the

28

rights of its members, rights of freedom of speech and

of assembly. The Court said:

“ We think that petitioner argues more appro

priately the rights of the members, and that its

nexus with them is sufficient to permit that it

act as their representative before this court . . .

We reject respondent’s argument that the asso

ciation lacks standing to assert here constitu

tional rights pertaining to the members, who are

not of course parties to the litigation.” Id, at

458-59.

The Court also said:

“ Petitioner is the appropriate party to assert

these rights, because it and its members are in

every practical sense identical.”

It may be wryly suggested that one reason seg

regation is so easily enforced is because of the racial

characteristics involved, thus in a very real sense rela

tor cannot be said to be urging a purely personal right.

More properly he is urging a right common to all those

subject to the same vice by reason of the same racial

characteristics. One need not fully rely on the denial

of a nexus sufficiently close. Skin color is not a nexus.

However, should the cause of the vice, skin color,

be not sufficient, witness what Brewer v. Hoxie School

District, 238 F. (2d) 91 (8th Cir. 1956), says about the

identity of interests necessary:

29

“ The School board having the duty to afford the

children the equal protection of the law has the

correlative right, as has been pointed out, to

protection in performance of its function. Its

right is thus intimately identified with the right

of the children themselves. The right does not

arise solely from the interest of the parties con

cerned, but from the necessity of the government

itself. Cf. Ex Parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651

(1884). Though, generally speaking, the right to

equal protection is a personal right of an indi

vidual, this is ‘only a rule o f practice,’ Barrow

v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1952), which will not

be followed where the identity of interest be

tween the party asserting the right and the party

in whose favor the right directly exists is suf

ficiently close.” Id. at 104.

Accord, Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510

(1925) (pai ochial school asserting rights of parents

and children), and Tranx v. Raich, 289 U. S. S3 (1915)

(employee asserting employer’s right).

This same group of cases allowing standing on

the basis of proximity of interest includes the grand

jury cases where exclusion of Negroes as a class pro

vides Negro defendants with standing to object to the

exclusion of a class of which he is a member; e. g., Cas

sell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282 (1950).

Other cases indicate that a petitioner may even

assert the rights of parties not before the Court, even

30

if there is no real identity of interests connecting the

present and absent parties. Barrow v. Jackson, 346

U. S. 249 (1952), allowed a white co-covenantor of a

restrictive covenant to assert the rights of Negro pur

chasers. The Court said:

“ Under the peculiar circumstances of this case,

we believe the reasons which underlie our rule

denying standing to raise another’s rights, which

is only a rule of practice, are outweighed by the

need to protect the fundamental rights which

would be denied by permitting the damage ac

tion to be maintained.” Id. at 257.

The Court added that the petitioner “will be per

mitted to protect herself and, by so doing, close the gap

to the use of this covenant, so universally condemned

by the courts.” Id. at 257.

Segregation through the use of state coercive

powers has been universally condemned by the courts.

We respectfully submit that by permitting relator to

assert the constitutional rights of spectators another

gap will be closed on unconstitutional practices with

reference to minority groups.

V.

The Bill of Information Charging Defendant

With the Violation of 103.1 Is Fatally Defective

Because It Fails to Inform the Defendant of the

Nature and the Cause of the Accusation

Against Him.

31

The bill of information reads in pertinent part:

“• • • he did under circumstances such that a

breach of the peace could be occasioned thereby

congregate with others in and upon a public

street and upon public sidewalks in front of the

courthouse in the Parish of East Baton Rouge, a

public building, and in and around certain en

trances of places of business and failed and re

fused to disperse and move on when ordered to

do so by the Sheriff of East Baton Rouge, a

person duly authorized to enforce the laws of

this State . . (Emphasis ours.)

Relator contends that the above bill of infor

mation is fatally defective because it violates the Sixth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States;

Article 1, Section 10, of the Constitution of the State

of Louisiana, 1921, and L. S. A.-R. S. 15:227.

The Sixth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United, States reads in pertinent part:

“ In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall

enjoy the right to . . . be informed of the nature

and cause of the accusation . . . ”

Article 1, Section 10, of the Constitution of the

State of Louisiana, 1921, reads in pertinent part:

“ In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall

be informed of the nature and cause of the ac

cusation against him. . . .”

32

L. S. A.-R. S. 15:227, Article 227, of the Code

of Criminal Procedure reads:

“ The indictment must state every fact and cir

cumstance necessary to constitute the offense, but

it need do no more, and it is immaterial whether

the language of the statute creating the offense,

or words unequivocally conveying the meaning of

the statute be used.” (Emphasis ours.)

Relator immediately calls the Court’s attention

to the requirements of 15:227 that every circumstance

constituting the crime must be included in the indict

ment. A cursory reading of the bill of information

proves that instead of listing every circumstance con

stituting the crime it actually only uses the words

“ under circumstances” without stating what particular

circumstances were referred to.

At the very least this is a literal disparity be

tween the requirements of the statute and the qualities

of the bill of information.

The above bill of information does not meet the

test of the Cruisliank case, United States v. Cruishank,

97 U. S. 51f2, 23 L. Ed. 588, where it was said:

“ . . . The object of the indictment is, first, to

furnish the accused with such a description of

the charge against him as will enable him to

make his defense, and avail himself of his con

viction or acquittal for protection against a fur

33

ther prosecution for the same cause; and second,

to inform the court of the facts alleged, so that

it may decide whether they are sufficient in law

to support a conviction, if one should be had.

For this facts are to be stated, not conclusions

of law alone. A crime is made up of acts and

intent; and these must be set forth in the indict

ment with reasonable particularity of time, place

and circumstance.” (Emphasis ours.)

Relator assumes arguendo that the statute may

be sufficient to describe or legally characterize the of

fense denounced, but it is our position that the infor

mation is wholly insufficient to inform the accused of

the specific offense with which he is charged. As au

thority for this conclusion see State v. Varnado, on re

hearing, 208 La. 319, 23 So. (2d) 106 (19H ), which,

says:

“ It is the modern rule, universally applied by the

courts, that in charging a statutory offense it is

not necessary to use the exact words of the Stat

ute. An indictment or information for such an

offense is sufficient if it follows the language of

the Statute substantially or charges the offense 1

in equivalent words or others of the same import,

if the defendant is thereby fully informed of the

particular offense charged, and the court is en

abled to see therefrom on what statute the charge

is founded. . . .

34

“ The general rule . . . is without application

where the statutory words do not in themselves

fully, directly and expressly, without uncer

tainty or ambiguity, set forth all the elements

and ingredients necessary to constitute the of

fense intended to be punished. As the courts

have pointed out, the words of the statute may be

sufficient to describe or legally characterize the

offense denounced, and yet be wholly insufficient

to inform the accused of the specific offense of

which he is accused . . .” (Emphasis ours.)

We maintain that the general phraseology of

14:103.1 does not have a commonly understood meaning

and does not satisfy the test set out in State v. Robert

son, 2hl La. 2Jp9, 128 So. (2d) 61>6 (1961) at 128 So.

(2d) 61-8:

“ Under this test a statute is valid in the absence

of detailed specification if the general phraseol

ogy used in defining the crime has a fixed, defi

nite, or commonly understood meaning and appli

cation. . .

The phrase “ circumstances such that a breach of

the peace may be occasioned” has been interpreted but

has not been sustained by the U. S. Supreme Court.

See Taylor v. Louisiana, 82 Sp. Ct. 1188. We say said

phrase does not have a commonly understood meaning.

Further, the case of State v. Vanicor, 239 La.

357, 118 So. (2d) 1̂ 38 (1960), is in point. There de

35

fendants attacked the following portions of the statute,

to-wit: The possession of electrical devices “ under cir

cumstances which indicate the said possession is for the

purpose of illegally taking commercial fish . . .” This

Honorable Court said at 118 So. (2d) b k l:

“ The phrase ‘under circumstances which indicate

that said possession is for the purpose of illegally

taking commercial fish’ is too vague, general and

uncertain in our opinion to meet constitutional

requirements. The legislature has failed to spec

ify what these ‘circumstances’ are. The statute

furnishes no clear definition of the word and no

guide or standard by which such circumstances

can be judged. It is susceptible to many inter

pretations. Criminal Laws are stricti juris and

this Court has consistently refused to usurp leg

islative prerogatives by supplying definitions

omitted in Criminal Statutes. . . .”

L. S. A.-R. S. 14:103 specifically outlines specific

acts which constitute disturbing the peace. Those acts

prohibited deal with conduct which is overtly tumultu

ous. Obviously L. S. A.-R. S. 14:103.1 is the “ catch all”

provision, a net within which would fall all activities

not within 14:103. Thus being a general catch all

provision, the information must provide “ with reason

able particularity . . . time, place and circumstance.”

Merely to charge that defendant acted “ . . . under

circumstances such that a breach of the peace could be

36

occasioned thereby” is no more than a conclusion. The

bill o f information must state the specific circum

stances which could result in a breach; for example, the

presence of two hostile and belligerent groups, the pres

ence of armed individuals, the existence of fights, curs

ing or pushing or the presence of a group or groups

which in the past had disturbed the peace or finally

exhortation to violence.

In a recent United States Supreme Court deci

sion involving a prosecution under the same statute

here involved— L. S. A.-R. S. 14:103.1 (Taylor v. Lou

isiana, 82 S. Ct. 1188), the Court refused to sustain a

conviction based on the proposition that the mere pres

ence of Negroes in a situation involving protest of racial

discrimination violated this statute. This the Supreme

Court did without argument and in a per curiam deci

sion.

All that has previously been said with reference

to the phrase “ . . . under circumstances such that a

breach of the peace may be occasioned thereby . . .” may

be applied with equal vigor and with the same conclu

sion when applied to the other nebulous phrase in the

statute “ . . . crowds or congregates with others.”

It is submitted that unless an allegation or alle

gations are made in the bill of information of the spe

cific circumstances tending to occasion a breach of the

peace, then the mere allegation of the presence of an

individual with others upon a public street or in front

37

of a courthouse and his refusal to move on when ordered

to do so by the sheriff is insufficient to satisfy the

standards of completeness required under the Louisiana

law, the Louisiana Constitution and the Federal Con

stitution and such bill of information is void and of no

effect.

VI.

The Disturbing the Peace Statute (R. S. 14:103.1)

Under Which Relator Was Convicted Is Uncon

stitutional in Its Application If Construed as Here

to Proscribe Freedom of Assembly, Freedom of

Speech and Peaceful Picketing.

Mr. Justice Harlan in his concurring opinion in

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 S. Ct. 21̂ 8, said:

“ . . . Louisiana could not, in my opinion, consti

tutionally reach these petitioners conduct under

subsection (7 )— the “ catch-all clause” -—of its

then existing disturbance of the peace statute . . .

I intimate no view as to whether Louisiana could

by a specifically drawn statute constitutionally

proscribe conduct of the kind evinced in these two

cases, or upon the constitutionality of the statute

which the state has recently passed. . . .”

In the Garner case the defendants were charged

with violation of Subsection (7) of L. S. A.-R. S. H :103,

the old disturbing the peace statute. It read in perti

nent part as follows:

38

“ Disturbing the peace is the doing of any of the

following in such a manner as to foreseeably dis

turb or alarm the public:

“ (7) commission of any other act in such a man

ner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm the pub

lic.”

We adopt the previously quoted position of Mr.

Justice Harlan and apply it to the present facts and to

L. S. A.-R. S. 14:103.1.

We further adopt the following remarks made by

Mr. Justice Harlan in Gamer, where he refers to State

v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 1U So. (2d) 778:

“ In that case the Louisiana Supreme Court re

versed the convictions, under the then breach of

the peace statute, of four Jehovah’s Witnesses

who had solicited contributions and distributed

pamphlets in a Louisiana Town, with an opinion

which cited, inter alia, Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296, and Martin v. Struthers, 318 U. S.

141. Reference was made to the provisions of

the Constitution of the United States guarantee

ing freedom of . . . Speech. 203 La. At. 968, 14

So. (2d) At. 780. The Court said most clearly,

‘The application of the statute by the trial judge

to the facts of this case and his construction

thereof would render it unconstitutional under

the above Federal Authorities.’ 203 La. At. 970,

14 So. (2d) At. 780, 781.”

39

R. S. 14:103.1, one of the statutes under which

relator was charged, has been construed by the state

to make peaceful picketing illegal on the theory that it

constitutes disturbing the peace. This statute also ex

pressly exempts labor picketing, thus, by implication,

coupled with the interpretation of the trial Court, ef

fects an unconstitutional result which was and is now

prohibited. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 (1940).

Thornhill v. Alabama held that peaceful picket

ing was within the liberties protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments. Thornhill further held that

such interest as the state had in protecting public peace

was not substantial enough to proscribe peaceful picket

ing. Such interest as the State of Louisiana has in pro

tecting the public peace is not substantial enough to

constitutionally support the application here made of

the statute.

Even if it be conceded arguendo that the statute

might be constitutionally enforced in other circum

stances, it is not so when its enforcement limits free

dom of expression, as here. In a concurring opinion

in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 82 S. Ch 248, Mr.

Justice Harlan said at 272:

“ . . . When a state seeks to subject to criminal

sanctions conduct which, except for a demon

strated paramount state interest, would be within

the range of freedom of expression as assured by

the Fourteenth Amendment, it cannot do so by

40

means of a general and all inclusive breach of

the peace prohibition. It must bring the ac

tivity sought to be proscribed within the ambit

of a statute or clause ‘narrowly drawn to define

and punish specific conduct as constituting a

clear and present danger to a substantial inter

est of the state.’ Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra

310 U. S. at 311; Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U. S. 88, 105. And of course the interest must be

a legitimate one. A state may not ‘suppress free

communication of views, religious or other under

the guise of conserving desirable conditions.

Cantwell, supra, at 308.”

Relator here was convicted under a disturbing

the peace statute which is a supplement to a pre-exist

ing disturbing the peace statute. See R. S. 14:103. The

crime which the statute created is an offense very un

like the old misdemeanor of disturbing the peace. As

applied here, the mere act of persons peacefully pro

testing against racial segregation is given the dynamic

quality of a crime. There is guilt, although there were

no fights, riots, angry words, or molestation of the pub

lic. Thus, in effect, the accused is to be punished not

for an actual disturbance of the peace but for advocat

ing an end to racial segregation.

The right of free speech is a fundamental right

given a preferred position with relationship to the other

freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. This right

41

may not ordinarily be denied or abridged. But although

the right to free speech is fundamental, it is not in its

nature absolute. Its exercise is subject to restriction,

if the particular restriction proposed is required in

order to protect the state from serious injury— political,

economic or moral. That the necessity which is essen

tial to a valid restriction does not exist unless speech

would produce, or is intended to produce, a clear and

imminent danger of some substantive evil which the

state constitutionally may seek to prevent has been set

tled. See Schneck v. United States, 2U9 U. S. 1̂ 7, 52.

It is the function of the Legislature to determine

whether at a particular time and under the particular

circumstances the intent to breach the peace or presence

under circumstances such that a breach of the peace may

be occasioned thereby, coupled with crowding or con

gregating with others and refusing to move on when

ordered to do so by police, constitutes a clear and pres

ent danger of substantive evil. The Legislature must

decide in the first instance whether a danger exists

which calls for a particular protective measure. But

where a statute is valid only in case certain conditions

exist, the enactment of the statute cannot alone establish

the facts which are essential to its validity.

The courts have not yet fixed the standards by

which to determine when a danger shall be deemed

clear; how remote the danger may be and yet be deemed

present; and what degree of evil shall be deemed suffi

42

ciently substantial to justify resort to abridgment of

free speech as the means of protection. To reach sound

conclusions on these matters it is necessary to bear in

mind why the state is ordinarily denied the power to

prohibit dissemination of social, economic and political

doctrine which a vast majority of its citizens believes to

be false and fraught with evil consequence.

Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify sup

pression of free speech. Thus the presence of one in

circumstances such that a breach of the peace may be

occasioned does not qualify the state to abridge the right

of relator to peacefully picket, nor does the imputation

to relator o f intent to disturb the peace qualify the state

to abridge peaceful picketing. To justify the suppres

sion of free speech there must be reasonable ground to

fear that serious evil will result if free speech is prac

ticed. There must be reasonable ground to believe that

the danger apprehended is imminent. There must be

reasonable ground to believe that the evil to be pre

vented is a serious one. In order to support a finding

of clear and present danger it must be shown either

that the immediate serious violence was to be expected

or was advocated, or that the past conduct furnished

reason to believe that such advocacy was then contem

plated.

No danger flowing from speech can be deemed

clear and present, unless the incidence of the evil ap

prehended is so imminent that it may befall before there

is opportunity for full discussion. Only an emergency

43

can justify repression. Moreover, even an imminent

danger cannot justify resort to prohibition of these func

tions essential to effective democracy unless the evil

apprehended is relatively serious. Prohibition of free

speech is a measure so stringent that it would be in

appropriate as the means for averting a relatively triv

ial harm to society. The fact that the picketing is likely

to result in some violence or in destruction of property

is not enough to justify its suppression. There must be

the probability of serious injury to the state. The legis

lative declaration that facts existed within the state

which constituted a clear and present danger to a sub

stantial state interest creates merely a rebuttable pre

sumption that said conditions constitutionally exist as a

general proposition. We submit that the evidence on

record does not constitute facts which authorize the

state to constitutionally abridge the right of relator to

peacefully protest against segregation.

If a contrary conclusion were reached, then any

time a Negi’o in Louisiana rebels, be it ever so peaceful,

against segregation, then he violates R. S. 14:103.1.

Every time the N.A.A.C.P. or C.O.R.E. holds a meeting

or every time a Negro sits in a front seat of a city bus

he may have intent to breach the peace imputed to him

or he may be deemed to have been present in a circum

stance whereby a breach of the peace may have been

occasioned. For Louisiana to infect the administration

of its criminal laws by using them to support the cus

tom of segregation offends the salutary principle that

criminal justice must be administered “ without refer

ence to considerations based on race.” Gibson v. Missis

sippi, 162 U. S. 565, 591.

The above-mentioned limitations exist not be

cause control of such activity is beyond the power of

the state, but because sound constitutional principles

demand of the state Legislature that it focus on the

nature of the otherwise “ protected” conduct it is pro

hibiting, and that it then make a legislative judgment

as to whether that conduct presents a so clear and

present a danger to the welfare of the community that

it may legitimately be criminally proscribed.

Louisiana may have made its legislative judg

ment, but it cannot reasonably be said that attention was

focused on otherwise protected rights. Rather than

focus the Legislature used a buckshot approach; witness

the bill of information in pertinent part:

“ . . . He did under circumstances such that a

breach of the peace could be occasioned thereby

congregate with others in and upon a public

street and upon public sidewalks in front of the

courthouse in the Parish of East Baton Rouge,

a public building, and in and around certain en

trances of places of business and failed and re

fused to disperse and move on when ordered to

do so by the Sheriff of East Baton Rouge, a

44

45

person duly authorized to enforce the laws of

the state.”

On February 25, 1963, the United States Su

preme Court in the case of Edwards, et at., v. South

Carolina, ■—- U. S. — , 23 U. S. S. Ct. Bulletin 919, re

versed convictions of some 187 Negroes who had been

found guilty of breach of the peace because they con

ducted a demonstration against racial discrimination

on the South Carolina State House grounds. The facts

in this most recent case are very much similar to the

facts herein. In Edwards this was said:

“ These petitioners were convicted of an offense

so generalized as to be, in the words of the South

Carolina Supreme Court, ‘not susceptible of exact

definition.’ And they were convicted upon evi

dence which showed no more than that the opin

ions which they were peaceably expressing were

sufficiently opposed to the views of the majority

of the community to attract a crowd and neces

sitate police protection.

“ The Fourteenth Amendment does not permit a

State to make criminal the peaceful expression

of unpopular views. . . .”

The Edwards case is in our opinion on all fours

with the instant case and requires a reversal of the

conviction herein.

46

VII.

The Disturbing the Peace Statute (R. S. 14:103.1)

Under Which Relator Was Convicted Is, If Ap

plied to Him, So Vague and Uncertain as to

Violate Due Process.

A. Due Process Requires That a State Statute

Give Fair Notice of What Conduct Is Crim

inal.

The United States Supreme Court has repeat

edly held that a state statute violates the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment if it fails (1) to

give fair notice of what acts it encompasses, and (2)

to provide the trier with a sufficiently definite stand

ard of guilt to avoid conviction on an ad hoc basis;

e. g., Lanzetta v. Neiv Jersey, 306 U. S. 151; Connolly

v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385; Musser v.

Utah, 333 U. S. 95; Winters v. New York, 333 U. S.

507, 519. As the United States Supreme Court said in

Connolly, 269 U. S. at 391:

“ . . . a statute which either forbids or requires

the doing of an act in terms so vague that men

of common intelligence must necessarily guess at

its meaning and differ as to its application, vio

lates the First essential of due process of law.”

Similarly, in Lanzetta, the Court defined the fail-

notice required by due process at 306 U. S. 153:

47

. . no one may be required at peril of life, lib

erty or property to speculate as to the meaning of