Scarlett v Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company Brief of Plaintiff Appellees Cross Appellants

Public Court Documents

June 13, 1980

62 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Scarlett v Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company Brief of Plaintiff Appellees Cross Appellants, 1980. 036994bc-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d173d2ae-5802-47c6-83fe-5bca18dc775e/scarlett-v-seaboard-coast-line-railroad-company-brief-of-plaintiff-appellees-cross-appellants. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

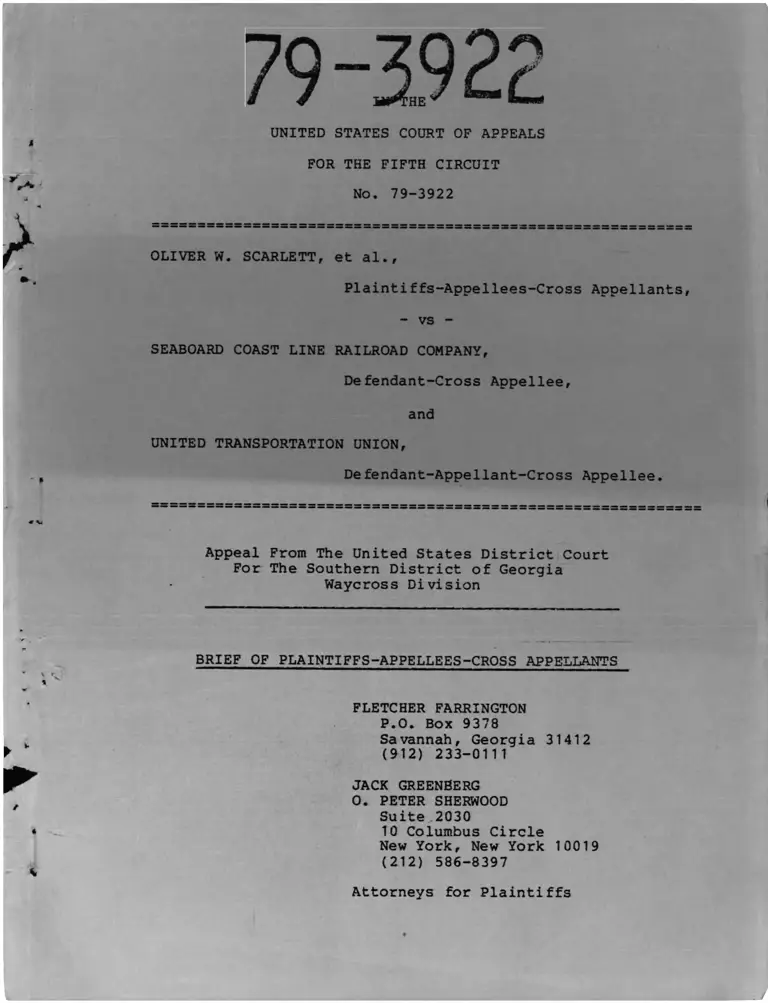

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

4

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-3922

OLIVER W. SCARLETT, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees-Cross Appellants,

- vs -

SEABOARD COAST LINE RAILROAD COMPANY,

Defendant-Cross Appellee,

and

UNITED TRANSPORTATION UNION,

Defendant-Appellant-Cross Appellee.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Southern District of Georgia

Waycross Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES-CROSS APPELLANTS

FLETCHER FARRINGTON

P.O. Box 9378

Savannah, Georgia 31412

(912) 233-0111r JACK GREENBERG

«

0. PETER SHERWOOD

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

/

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 79-3922

OLIVER W. SCARLETT, et al.,

PIaintiffs-Appellees-Cross Appellants,

- vs -

SEABOARD COAST LINE RAILROAD COMPANY,

Defendant-Cross Appellee,

and

UNITED TRANSPORTATION UNION,

Defendant-Appellant-Cross Appellee.

Appeal From The United States District court

For The Southern District of Georgia

Waycross Division

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned, counsel of record for Defendant Cross-

Appellee Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company, certifies that the

following listed persons have an interest in the outcome of this

case. These representations are made in order that the Judges of

this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal

pursuant to Local Rule 13(a):

1. Oliver W. Scarlett, Appellee;

2. H. B. Starkes, Appellee;

3. David Jones, Appellee;

4. J. Wimyond Jones, Appellee;

5. Horace V. Thomas, Appellee;

6. William D. Rood, Appellee;

7. F. D. R. Bell, Cross-Appellant;

8. W. J. Odol, Cross Appellant;

9. W. K. Linsdey, Cross-Appellant;

10. Appellant and Cross-Appellee United Transportation

Union and its affiliated, intermediate and local

local organizations representing employees of

Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company;

11. Employees of Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company

employed in crafts of Conductor and Trainman

(Brakeman and Switchman);

12. Defendant and Cross-Appellee Seaboard Coast Line

Railroad Company, its parent Seaboard Coast Line

Industries, Inc., and possibly the 36 concolidated

subsidiaries of Seaboard Coast Line Industries,

Inc. listed in certificate filed by defendant

Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co.

li

Statement Regarding Oral Argument

Plaintiffs believe that this appeal should be orally argued.

The legal issues are important and they involves questions that

the courts have begun to address only recently. These questions

include; 1) the proper interpretation of § 703(h) of Title

VII with respect to the legality of a seniority system which was

perverted for a racially discriminatory purpose and which continues

to adversely affect plaintiffs; and 2) the proper application of

this Court's analysis in James v. Stockham Valves & Fitting, Inc..

559 F .2d 310 (1977), regarding the implementation of § 703(h).

Oral argument will facilitate the resolution of these legal

arguments as well as assist in the presentation of the complex,

factual record in this appeal which covers over 80 years of

labor relations at the railroad.

i n

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Certificate of Interested Persons .................. i

Statement Regarding Oral Argument .................. iii

Table of Contents ................................... iv

Table of Authorities ................................ vi

Re-statement of the Issues on Union Appeal ........ 1

Statement of the Issues on Cross Appel ............

Statement of the Case .............................. 2

I. Course of the Proceedings and Disposi

tion in the Court Below .................. 2

A. The Record .................. ......... 2

B. Jurisdiction of the Trial Court ..... 3

II. Jurisdiction of This Court ............... 3

III. The Cross-appeal .......................... 3

Statement of Facts .................................. 6

I. Preface ................................... 6

II. The Clock Begins to Tick ................. 9

III. The Time that Counts ..................... 11

IV. The Influence of Seniority ............... 12

V. How Seniority is Lost .................... 15

VI. An Intention to Discriminate ............. 18

- i v -

Page

Page

Argument

I. Summary of Argument ....................... 24

II. Issues Presented on Union Appeal ........ 25

Preface ................................... 25

A. The Trial Court's Finding that

Plaintiff Oliver W. Scarlett

Received a Notice of Right to Sue,

Is Not Clearly Erroneous ............. 26

B. The Trial Court's Finding That the

Union Is Named in Mr.' Scarlett's EEOC

Charge, Is Not Clearly Erroneous .... 26

C. The District Court Properly Determined

That the Seniority System Is Not Bona

Fide Within the Meaning of

§ 703(h) ............................ 29

D. Plaintiffs Are Entitled, Pursuant to

42 U.S.C. § 1981, and Ga. Code § 3-704,

to Injunctive Relief From The Conse

quences of Defendants' Intentional

and Racially Discriminatory Assign

ment, Transfer and Promotion Practices

Even If the Seniority System Is Found

Bona Fide .......................... 38

III. Issues Presented On Cross-Appeal .......... 41

Introduction .............................. 41

A. The District Court Erred In Failing

to Declare Plaintiffs Bell, Odol and

Lindsey Entitled, Or At Least

Presumptively Entitled, to Relief

From The Effects of Defendants

Non-Bona Fide Seniority System ...... 41

B. Where The Record Demonstrates That

Plaintiffs Bell, Odol and Lindsey

Sought Transfer to the Trainman/

Conductor Craft, the District

Court Erred In Failing to Award

Them Injunctive Relief Under

•42 U.S.C. § 1981 ..................... 44

Conclusion .......................................... 46

Appendix ............................................

v

Table of Authorities

Acha v. Beame, 570 F.2d 57 (2d Cir. 1978) .......... 30

Alexander v. Aero Lodge No. 735 (AM) 565 F.2d 1364

(6th Cir. 1977), cert denied 436 U.S. 946 (1978). 31

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., 495 F.2d

437 (5th Cir. 1974)............................... 25,42

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).. _r. 34

California Brewers Assn. v. Bryant, ___ U.S. ___,

63 L . Ed. 2d 55 (1980) ............................. 6,7,8,33

Camack v. Hardee's Food Systems, Inc., 410 F. Supp.

1217 (D. Ariz. 1975) ............................ 28

Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal Inc., 15 EPD 1(7933 (N.D. Ind.

1977) ............................................. 31

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449 (1979) ....................................... 37,38

Cook v. Mountain States Telephone & Telegraph

Co., 397 F. Supp. 1217 (D. Ariz. 1975) ......... 28

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979) ........................................ 34

EEOC v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 577 F.2d 229

(4th Cir. 1978) .................................. 35

Fisher v. Proctor & Gamble Mfg. Co., 613 F.2d 527

(5th Cir. 1980) .................................. 35

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) 25,39,42,43,44

Hairston v. McLean Trucking Co., 520 F.2d 226

(4th Cir. 1975) .................................. 42

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964) ............ 12

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ..................... 24

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559

F . 2d 310 (1977) ................................. iii, 24,29,30

Cases Page(s)

vi

Cases Page(s)

H. Kessler & Co. v. Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, 53 F.R.D. 330 (N.D. Ga. 1971)

affirmed, 468 F.2d 25 (5th Cir. 1972) ............ 28

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).. 34,37

Local 189, United Paperworkers v. United States,

417 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 387

U.S. 919 (1970) .................................... 31

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973). 41,43

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d 283

(5th Cir. 1969) ..................................... 27

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 556 F.2d 758 (5th Cir.

1977) ................................................ 24,29,30

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 586 F.2d 300

(4th Cir. 1978) ..................................... 30

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 576 F.2d 1157

(5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied 439 U.S. 1115 (1979). 38

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505

(1968) ............................................... 31

Ridgeway v. Intern. Broth, of Elec. Wkrs., Etc.,

466 F. Supp. 595 (E.D. 111. 1979) .................. 28

Rule v. Ironworkers (IBSOIW), Local 396, 568 F.2d

558 (8th Cir. 1977) ................................. 40,42

Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455 (5th

Cir. 1970) ........................................... 28

Shehedeh v. Chesapeake & Potomac Tel. Co. of Md.,

595 F . 2d 711 (D.C. Cir. 1978) ...................... 35

Steele v. Louisville and Nashville Railroad Co.,

323 U.S. 192 ......................................... 14

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, F. Supp. , 17

EPD 1[ 8604 (N.D. Ala.1978) ........................ 17

Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight, 487 F.2d 416

(6th Cir. 1974) .................................... 28

United States v. American Railway Express Co.,

265 U.S. 425 (1924) ................................ 4, 35

vi i

Cases Pages(s)

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F .2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973) ...............................

United States v. United States Steel Corp., 520

F .2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975) ....................

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) .......

Wheeler v. American Home Products, 563 F.2d 1233

(5th Cir. 1979) ...............................

Williams v. DeKald County, 581 F .2d 2 (5th Cir.

1978) ..........................................

Other Authorities

Ga. Code Ann. § 3-704 .........................

Rule 52(a) F.R. Civ. ...........................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) ......................

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h) ......................

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...............................

Administration of the Railway Labor Act by the

National Mediation Board, .1934-1970 (U.S.

Government Printing Office: (1970) ...........

24,39,40

42

38

28

18,24

25,38,39,40

27

3

1, 6, 25,38

1 ,2,25,38,44

; 3

viii

RESTATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED BY THE APPEAL

OF UNITED TRANSPORTATION UNION V

1. Is the trial court's finding that plaintiff Oliver W.Scarlett

received a notice of right to sue, clearly erroneous?

2. Is the trial court's finding that the union is named in

Mr. Scarlett's EEOC charge, clearly erroneous?

3. Is the trial court's finding that defendants perverted the

seniority system for a discriminatory purpose, clearly erroneous?

If not, is the trial court's holding that a seniority system that

was consistently used to discriminate and which currently

perpetuates the effects of prior discrimination is not bona fide

within the meaning of section 703(h) of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, error?.

4. Did the trial court correctly apply the Georgia statute

of limitations to plaintiffs' claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 for a

remedy for defendants' intentional assignment, transfer and

promotion discrimination?

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED BY THE CROSS APPEAL

1. Where, prior to the commencement of trial the district

court declared that "if plaintiffs are sucessful in proving that

the seniority system is not bona fide and that it perpetuates the

effects of pre-Act discrimination, they will have proved their

case under Title VII," is its subsequent holding that plaintiffs

Bell, Odol, and Lindsey are not entitled to prevail because of

*/ Appellant's statement is prolix, ill-drawn, uninstructive.

1

their failure to establish at trial that they applied error?

2. Regardless of whether or not the district court erred in

finding the seniority system non-bona fide, are plaintiffs Bell,

Odol, and Lindsey entitled to a remedy based on their 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 claim?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE-^

I. COURSE OF THE PROCEEDINGS AND DISPOSITION IN THE COURT BELOW.

A. The Record

2/

For a case with such a record, the trial was short.

Many disputed issues were resolved before trial. The parties

filed six motions for summary judgment (R. 30; R. 68 & R. 71

3/

[SCL]; R. 80 [UTU]; R. 116 & R. 146 [plaintiffs]), and

defendants filed 20 other motions, in five separate pleadings

addressed to jurisdiction and the merits (R. 5; R. 11; R. 21; R.

26; R. 75). Most of these were supported by documents and

exhibits outside the pleadings (see, e.g., R. 75:6). In conse

quence, the record was well developed, and had been considered

by the trial court (R. 192:5), before oral testimony was taken.

V Appellant's Statement is incomplete.

2/ There are 222 entries on the district court's docket sheet.

This does not include trial exhibits.

3/ The trial court's local rules, adopted after defendants filed

their motions for summary judgment, but before plaintiffs',

require that the moving party file a statement of the facts

it contends are not in dispute. The opposing party must then

file a separate statement setting forth those facts (if any) he

controverts. If the opposing party does not file the required

controverting statement, the moving party's statement is admitted

2

B. Jurisdiction of the Trial Court

The United Transportation Union, joined by Seaboard Coast

Line Railroad Company, moved to dismiss the original complaint,

alleging that plaintiff Oliver Scarlett had not commenced his

action within ninety days of receiving his right-to-sue letter

from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (R. 5:1; R. 6:4;

R. 12-2). The union seemed then to agree that Mr. Scarlett

4/

received the letter; its address was rather to the alleged

tardiness of the subsquent federal court complaint. In response

to these motions and to SCL's discovery requests, plaintiffs

filed Mr. Scarlett's right to sue letter, which shows that copies

were mailed to both the union and the railroad (R. 16:10; R.

5/

17:16). The trial court found that Mr. Scarlett received the

letter, and that he commenced his action within ninety days

thereafter, as required by 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) (R. 33:6). The

court affirmed this finding in a second order (R. 60:2), denying

one of SCL's motions for summary judgment.

3/ cont'd.

(Trial transcript (hereinafter, "T.") 316-17). C_f. Rule 36,

F.R.Civ. P. Neither defendant filed a separate statement contro

verting plaintiffs' facts (see F. 147:1-6). Consequently, either

of plaintiffs' statements of fact (R. 116:5-17; R. 147) is

adequate to support the judgment below, independently of the

evidence adduced at trial. See, e.g. , R. 192:5 (record supports

a finding that the railroad consistently discriminated against

blacks with respect to the establishment, accumulation or exer

cise of seniority).

4/ "Mr. Scarlett failed to file suit within ninety days from the

dismissal of his charge....[T]he remaining plaintiffs have re

ceived no notice of failure of conciliation or of right to sue"

(R. 12:2, at § 119).

5/ A copy of the letter is attached as an appendix to this brief,

App.-1, infra.

3

II. JURISDICTION OF THIS COURT

The filing of a timely notice of appeal is necessary to give

this Court jurisdiction. Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Company did

not appeal. Those portions of its brief asking this Court to

reverse the trial court should therefore be stricken. A party

who does not appeal from the decree of the trial court cannot be

heard in opposition to the decree. United States v. American

Railway Express Co., 265 U.S. 425, 435 (1924).

III. THE CROSS-APPEAL

The pre-trial conference was held on November 18, 1977 (R.

Docket, p. 14). Because this hearing was specifically set with only

two day's notice (see R. 107), a fully subscribed Rule 16 pre-trial

order was not presented. Rather, defendants prepared and pre

sented to the court a proposed consolidated order, short only by

1 /plaintiffs' contentions.

According to this "Consolidated Pre-trial Order" (R. 87)

(entered in the record as such but, as noted, not signed (R.

87:16)), the question to be tried repecting the claims of cross

appellants Bell, Odol, and Lindsey was this: [Were t]he trainman

seniority dates of [cross-appellants] established ... pursuant to

a [nondiscriminatory] policy ...[?] (R. 87:3; 11 4). Defendants

also requested that "this Court order a bifurcated trial (R.

87:16), with "damages and seniority relief ... reserved until

[Stage II]" (R. 211:7). The trial court granted this request

6/ The court received this proposal and ordered it filed, but

withheld signing it pending receipt of plaintiff's contentions.

See also T. 22, where counsel refers to "the last pre-trial

order."

4

(Id..)* At trial, Seaboard Coast Line announced that: "The

only issue in this case as we see it is whether the ... seniority

system on the Seaboard Coast Line is bona fide" (T. 5). "It was

to examine this sole issue that Your Honor opened up the judgment

..." (T. 6). The union described the issue for trial as "whether

or not the universally applied rule [is] that entry into the

craft ... is the determining factor for measuring a man's senior

ity in that craft" (T. 6).

Before trial, Seaboard Coast Line advised the court that

cross-appellant Bell "... in July of '55 ... applied as a switch

man, [a]nd [the SCL representative] said that, you know, we

weren't hiring any black switchmen" (R. 48:5); and that cross

appellant Lindsey "was denied the right to be a switchman at the

time I applied for it" (.id). Cross-appellant Odol testified, in

a deposition later conceded by SCL to have been "included in the

record" (see R. 109:4), that "I had tried to apply for switchman

job ... in ... October ... '62, and as they said — they was

stating that they wasn't hiring — excuse the expression [— ]

VNiggers" (R. 42:2; refiled at R. 211:9).

Overlooking this, the trial court concluded that each

cross-appellant failed "to prove at least that at the time of his

initial hire he applied for trainman's job" (R. 201:10, emphasis

the court's). Plaintiffs moved the court to reconsider this (R.

210), citing the above testimony (R. 211:8-10), and adverting to

their position that, having proved the unlawful policy put in

issue by the pre-trial order, and by the opening statements of

7/ Only the cover sheet of the deposition appears in the record.

The full depositions are included with the exhibits.

5

counsel, they were not required to establish their individual

right to relief until Stage II (see R. 211:3-6; cf. R. 1 07:23, 11

5). This the court denied (R. 215) and these plaintiffs appealed

(R. 220.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

• • • this sorry tale of discrimination...

Trial Court (R. 201:5).

Pre face

"Whether a seniority system is bona fide is a mixed question

of law and fact" (UTU at 43). To understand what facts are

relevant, then, it is necessary to understand the law. The

unions' "Statement of Facts", to the extent it is not misleading,

is for the most part irrelevant because it ignores the disposi

tive law.

Under § 703(h) of the Civil Rights Act of 1 964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(h), it is not unlawful for an employer to make distinc

tions in the treatment of his employees pursuant to a bona fide

seniority system, provided "that such differences are not the

result of an intention to discriminate because of race." It

seems fundamental that any factual inquiry under § 703(h) must

begin with a description of the "seniority system" that is

claimed to be bona fide. In California Brewers Association v.

Bryant, ___ U.S. ___, 63 L.Ed.2d 55 (February 20, 1 980) (an

nounced nearly two months before the union's brief was filed),

8/ Compare UTU at 13: "There was absolutely no proof relative

to any right to sue letter," with R. 12:2 (UTU admits Scarlett

received "notice of dismissal" (i.e., right to sue leter); R.

16:10 & 17:16 (copies of the right to sue letter); and R. 33:6 St

60:2 (court finds right to sue letter received by Mr. Scarlett).

6

the United States Supreme Court affirmed this elementary princi

ple. Neither defendant cites the case in its brief and appellant

UTU makes assertions that are flatly contradictory to the Supreme

Court's holding.

A "seniority system" includes "more than simply those

components of any particular seniority scheme that, viewed

in isolation, embody or effectuate the principle that length

of service will be rewarded." Id_. , at 64. In order for a

seniority system to operate at all, it must contain rules, Id.,

that:

1. deliniate how and when the seniority clock begins

ticking 9/

2. specify how and when a particular person's seniority

may be forfeited;

3. define which passages of time will count and which

will not; and

4. particularize the types of employment conditions that

will be governed or influenced by seniority and those

that will not.

Rules that serve these purposes do not fall outside the "seniority

system" "simply because they do not, in and of themselves, operate

on some factor involving the passage of time." California Brewers,

Id. at 65.

The union misstates the facts necessary to resolve this

appeal. It views the challenged seniority provision "in isola

tion"; its entire factual premise is that because these discrimi-

natorily applied rules respecting the "establishment, accumula

tion or exercise of seniority" (R. 192:5) "do not, in and of

9/ Defendant UTU offers a contrary view:

The provision [of UTU agreement] excluding blacks

from positions of baggagemaster, flagmen or yard

conductors ... was not a seniority provision UTU

at 24.

7

themselves, operate on some factor involving the passage of

time," they are not a part of the seniority system. For example,

1 0/

trainmen were entitled, by right of seniority, to promotion

to baggagemaster, flagman or yard conductor. UTU says that the

provisions of the UTU agreements preventing black trainmen from

using their seniority to assume these positions "was not a

seniority provision" (UTU at 23); and "the seniority system ...

are [sic] distinct from the conditions of employment ... to

which they are [sic] applied (UTU at 18). Aside from the

sophistry of these postulates, their disconnection from the

unambiguous holding of California Brewers makes circumambulating

shadows of the union's "facts."

]0/ Switchmen and brakemen are "trainmen".

8

A. The Clock Begins to Tick

Seniority rights of individual employees are matters

peculiarly of interest to the UTU and its members

and SCL is not responsible for such matters.

Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co., December 18,

1977 (R. 87:4, «| 11) .

The United Transportation Union is the successor of

four operating craft unions: Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen

(BRT); Order of Railway Conductors (ORC); Brotherhood of Loco

motive Firemen and Enginemen (having jurisdiction of the engine

service crafts — not involved in this case); and the Switchmen's

Union of North America (which represented no employees on the

11/Seaboard Coast Line) (R.115:4-5; 117:22). These were among

the first labor organizations in the country, originating as

fraternal clubs for white men (R.116:16; T.14) in the railroad

boom years following the Civil War (T.13-14).

For as long as they existed (until 1969-T.399), the

unions retained their fraternal, racially exclusive character

The union complains, UTU at 14, that "there is no evidence

in the record relative to...other [than the BRT] unions."

This is false. As respects the ORC, there are contracts

in the Record, including a contract between ORC and the

Atlantic Coast Line (now SCL)(R.163:1-44; see also R.162:

13-15). These were filed by UTU in opposition to plain

tiffs' second motion for partial summary judgment. There

is also substantial evidence in the record regarding dis

crimination by the BLF&E on the ACL (see, e.g., R.116:20,

If If 15, 16; 117:16, 18) as well as in the country at large

(see, e.g., R.116:16). Moreover, UTU asserted in the court

below that discrimination practiced by the firemen's union

is of no consequence to this case (R.164:6). Cf. R.121:17

(SCL asserts that BRT is the only union involved in the

case). See also R.115:4,5; 157:27.

9

(T.14). By the 1880's, however, their dominant purpose had be

come the negotiating of employment benefits from the railroads

for white men working in the operating crafts (T.13). Aside

from wage bargaining, the chief concern of the unions was to

make contracts for the establishment, accumulation and exercise

(R-192:5) of ever-increasing employment benefits based on length

of service (R.161:10-11).

By 1890, the conductor's union had won contracts

effectively giving the union the right to decide who would

establish seniority and who would not: "So far as it can be

done consistently, [members of the Order of Railway Conductors]

should have preference in the filling of vacancies..." (R.162:

13 - Agreement between ORC and Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific

Railway). On other lines, the conductor's union negotiated

agreements giving their members the right to determine who would

be used as trainmen under them: "Conductors shall have the right

to object to Brakemen for cause, and when objections are sustain

ed by facts they will be furnished with other men" (R.162:64 -

contract between conductor's union and Galveston, Harrisburg &

San Antonio and Texas and New Orleans Railroad Co. (1889). See

also T .70, 92-93 - contract between conductor's union and Chicago

and Northwestern Railway Company (1891): "Brakemen will, in

all cases, be placed as the conductor's best judgment indicates".

Cf. R.116:11, Rules for the Plant System of Railways [now SCL]:

"In case of emergency... conductors ...[may] select flagmen).

10

All of these contracts provided that an employee's

seniority began on the first day he worked in his craft (R.116:

10; 162:21, 53; 163:61).

B . The Time That Counts

...I'm not going to let those son of a bitches tell

me who to hire and who not to hire. Before it's

over, I'm going to fill this yard up with.♦.niggers.

ACL Terminal Trainmaster E. S. Blackburn,

Waycross Yard, 1938 (see T.190).

The men who built railroads did so, in the main, for one

object: return on investment (R.161:12). The owners saw the unions'

wage demands as contrary to this singular interest (R.116:16; T.84-

85). To circumvent the diseconomy of high wages, many southern

railroads — rejecting social and political custom in favor of pro

fit — began to use black workers, who could be hired for half the

wages of union men (white men), as switchmen, brakemen and firemen

(T .13; R.116:16). The Atlantic Coast Line was the apparent leader

in this: in the first decade of this century it hired only Negroes

as switchmen (R.116:16; 117:44, 46-47; T.13).

The unions reacted bitterly to this "discrimination

against white trainmen" (R.116:19). On the floor of the 1899 con

vention of the BRT, the union adopted a resolution calling on the

other Brotherhoods "to give support to clearing our lines of this

[Negro] class of workmen" (T.15). For the next 70 years, the union

consistently (R.201:4), usually openly but surreptitiously if

necessary (T.26), and with varying success, followed its perverted

(R.201:6; T.94-95) resolve (T.14-16, 26).

In 1910, the BRT proposed, and the Atlantic Coast Line

agreed, to limit the number of Negroes to be hired in each sen

iority district (emphasis added) to that percentage of Negroes

11

employed in each such district on January 1, 1910 (T.

12/15-16). This agreement was designed to preserve the seniority

of white employees and to prevent black employees from estab

lishing seniority in the craft (R.164:5-6). Since the percentage

of Negro trainmen on the Atlantic Coast Line was already high,

because of the railroad's earlier hiring policy, the agreement

did not prevent ACL from continuing to emplov Negro trainmen.

13/

Despite the union's efforts to prevent it, black workers

were able to establish seniority as trainmen: brakemen and

switchmen; on the ACL, until May, 1945 (T.105-06, 190, 230).

C . The Influence of Seniority

It is of the utmost importance that the proper rules

for the government of the employes of a railroad

company should be literally and absolutely enforced.

...If they cannot, or ought not to be enforced,

they ought not to exist.

General notice from the Plant System of Railways

[now SCL], January 1, 1896 (R.116:10).

"...[0]ne of [seniority's] major functions is to de-

14/termine who gets or who keeps an available job." This function,

in the train service, operates in two ways: by determining order

12/

Appellant complains that plaintiffs did not connect this

agreement to the Atlantic Coast Line. UTU at 24. This is

false. See R.117:13, at n. 11 and accompanying text.

13/ Plaintiff Horace Thomas applied for and "cubbed" (learned on

his own time) a switchman's job in 1938. Because of object

ions from the trainman's organization, he was delayed more

than a year in taking his job. T.190.

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335, 346-47 (1964).

14/

-12

of promotion (from switchman to yard foreman, and from brakeman

to flagman and conductor) and choice of job assignments. The

trainman's universal seniority rule is that trainmen are called

for promotion to conductor in the order that their names appear

on the trainman's seniority roster (R.116:11, 198; 122:1; 162:4,

6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 19, 25, 35, 28, 29, 42, 45, 49, 53, 61, 70;

163:62). Before World War I, it was easy enough to keep blacks

from being promoted — only members of the union were benefici

aries of the unions' seniority agreements, and black men were

not then (or ever) members of the BRT (R.120:5).

The War made a difference, with the government

nationalizing railroad operations, and ordering, in "an act of

simple justice," that equal wages be paid to black trainmen

(R.116:18; T.102-04). After the War, the Railroad Administration

continued to enforce this and other work rules. Realizing that

if Negroes were to be treated equally for wages, there was nothing

to prevent them from being treated equally with respect to

choice of jobs and order of promotion, the BRT proposed to the

Railroad Administration (T.22-23) — no, coerced by threat of

15/

strike — (T.26) a set of work rules that perverted (R.201:6;

15/ The union claims there was no "proof" that these rules

applied to SCL. No "proof" was necessary. As a matter of

law, all railroads operating in Interstate commerce (in

cluding SCL) were governed by the Railroad Administration.

See generally, Administration of the Railway Labor Act by

the National Mediation Board, 1934-1970 (U.S. Government

Printing Office: 1970 0-388-548), at pp. 176-78.

13

T.95-96) the Negro trainman's seniority:

When new runs [(jobs) are] created, or vacancies

occur] ], the employee with the highest seniority

[will] have 'preference in choice of run [job]

or vacancy either as flagmen, baggagemen, brakeman

or switchman, except that Negroes are not to be

used as conductors, flagmen, baggagemen or yard

conductors' (R. 116 :18-19 , <[ 12; T.22-23).

The purpose of these rules, according to the union, was to "end

discrimination against white trainmen" (R.117:15).

Following the return of SCL to private control in

1920, defendants continued to enforce the rules preventing

blacks from using their seniority - as whites used theirs - to

gain promotion from trainman to conductor (T.109; see also R.

98:1: SCL rule book provides that blacks are not to be used as

conductors and baggagemasters). In 1944, these rules were in-

ferentially made illegitimate by the decision of the Supreme

16/Court in Steele v. Louisville and Nashville Railroad Co.

Accordingly, from that time forward, the written seniority

agreements between SCL and UTU were, on their face, neutral:

Promotion will be from trainmen to... conductor in

their relative standing on the trainmen's seniority

roster. Trainmen having at least two years ex

perience as such shall be in line for promotion,

and when called for promotion shall be notified by

certified mail. . . (R. 116 :-198 ; see also R.122:1-2).

Despite its apparent neutrality, this rule was selectively en

forced, being uniformly applied to whites and uniformly denied

to blacks; until 1967, at the Moncrief Yard in Jacksonville

323 U.S. 192.

16/

14

(R.7:9, 11, 12; 117:21) and until 1970 at the Waycross Yard

(R.117:22-23). And for Negro brakemen hired (before Steele) on

the Savannah Side of the Waycross Division (plaintiff J. W.

Jones) the rule was never enforced (R.201:5; T.115-16).

D . How Seniority is Lost

That meant...you was a nigger brakeman..., 1 one

of the niggers before the wartime.1 And,_as often

as they could keep you in the streets they would....

[I] f I had the seniority enough to hold the brake-

mari's job, and there was a conductor, he would give

up his conductor's rights and come up there and pull

me and let the...younger men stay on the cab, and

that would keep me in the streets starving to death..

Plaintiff J. W. Jones, remembering 1944

(T. 107, 111).

With the economic incentive to hire Negro trainmen lost

to the 1917 wage equalization order, Atlantic Coast Line might

have been expected to follow the Brotherhood's entreatment to

"clear our line of this class of workmen" (see T.15). It did

not. Despite union opposition, the railroad continued to use

black workers in the trainman's craft, at least until after

Steele.

Plaintiff J. W. Jones was hired as a brakeman in 1938

(R.117:44; T.105-06). The 1919 BRT-induced work rules not only

kept Mr. Jones from being promoted to conductor, it also affected,

in a way not applicable to whites (R. 116:19, if 14) his choice of

jobs. Older white employees, who held seniority both as brake-

men and conductors, could use their seniority to roll him from

15

his brakeman's job at the head end of the train, allowing junior

whites to fill jobs that Jones, because of the racially applied

seniority rules, could not hold: flagman, baggagemaster and

conductor (T.22, 108-11). This racially based use of seniority

for job selection was called, appropriately enough, "sharp

shooting" (T.128).

Sharpshooting was not practiced in the switching yards,

however. There, yard conductors were required to work as such if

conductor jobs were available. If they gave up a conductor job

to roll a switchman, they lost their conductor seniority (T. 151).

Consequently, plaintiffs Scarlett, Starkes, Thomas and Rood --

all of whom had transferred (some at the request of the railroad)

from all-black jobs to switchman jobs in the early 1940's —

(R.117:16, 17) were able to use their trainman seniority for job

selection (although not for promotion, and not for assignment

on the job, T.191-92) realtively free of union interference (T.

151). Until 1965.

Some time after the Civil Rights Act became law, BRT

sought and obtained an agreement from the railroad -- its eu

phemism: "switching by preference" — which brought sharpshooting

to the yards (T.151-55). Under this agreement, a conductor(still

an all-white craft) was no longer required to work at his craft

if he preferred lesser pursuits. He could "switch by preference"

— sharpshoot (T.174) — and retain his conductor's seniority

16

(T.171-73).

The testimony at trial was in conflict as to whether

this "preferred seniority" agreement (T.432) was the result of

an intention to discriminate. Plaintiffs testified that it was

aimed at those very senior black trainmen who had by now ac

cumulated enough trainmen's seniority to hold the choice high

overtime switching jobs (T.154-55). A union witness said that it

was passed to encourage men to take promotion to conductor (T.

434), but the railroad did not support this testimony. In any

event, the scheme precipitated this lawsuit.

In 1972, Oliver Scarlett, who was promoted to con

ductor after the sharpshooting agreement was made, who had twenty-

eight years of trainman's seniority and more than thirty years

in his craft, rolled a younger white switchman from a high-overtime

trainman's job. The conductor on this job -- an old-timer;

member of the fraternity — immediately vacated his job, let the

junior white switchman (senior, of course, to Scarlett in

conductor's seniority) take the now-vacant conductor's job,

waited a week, came back, and like old times on the road, rolled

Scarlett from his job. Scarlett— sharpshot, seniority frustrated

(.cf. T. 154-55) — complained to the company. (He could not

complain to the union -- he was not a member, and it refused to

process seniority grievances for non-members, even in 1972, T.

168-70). The company, following its age-old policy of deferring

17/to the union in seniority matters (R.87:4, K 11), shrugged

17/

Cf., Swint v. Pullman Standard, 17 FEP Cases 730, 738 (N.D.

17

(T.175-76). Within thirty days thereafter, Scarlett filed his

charge of discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (T.176).

18/E . An Intention to Discriminate

I was roped in as a trainman.... It was ridiculous

that I be out there [teaching the work] and not ac

cumulating any [seniority]....

[Then] train porter Booker T. Snowden, re

membering 1946 (R.116:126, 122).

Porters, attendants, cooks, waiters, air bleeders (R.

116:175-76) — Negroes all (R.116:120-22; T.255-56) — returned

from the War in 1946 hoping at last to leave their dying crafts

for trainmen's jobs. In a cruel paradox, Steele, supra, by out

lawing overtly racial agreements aimed at limiting the seniority

rights of Negroes, closed the door permanently to black acqui

sition of trainman seniority. Within six months of the decision

(see T .230) "the union, BRT, had [made a verbal] agreement with

the railroad not to hire any more blacks, and the railroad in

turns (original) agreed[. S]o long as [the B.R.T.] could keep

17/ (cont.)

Ala. 1978): "...[A] seniority system may properly be viewed

as the manifestation of a union objective, one which oper

ates in opposition to and as a limitation upon...managerial

powers.... [T]he seniority system under attack is essentially

the product of [union] aims and policies.

From Section 703(h), Civil Rights Act of 1964. Cf. Williams

v. DeKalb County, 581 F.2d 2 (5th Cir. 1978).

18/

18

19/

the work going, [the railroad] would not interfere" (R.116:122).

See also R.117:20; T.249-50. Cf. R.121:14, T.31: decisions

to maintain Negro employment at a minimum strongly influenced by

union policy; R.87:3, 1[ 11: seniority rights are peculiarly of

interest to UTU; SCL not responsible for such matters; T.230:

SCL vice president for labor relations cannot explain why company

changed its long-standing policy; R.175, T.234: present management

unable to set forth 1945-1965 history).

Although the railroad continued to draft black men from

their segregate crafts (as it had freely used plaintiffs during

the War as conductors — "lead switchmen," they were called

(T.192-93)) to operate trains according to the company's needs

2 0/

(R.116:120-22, 133-35; T.389) it withheld from these men

consistent wit its verbal agreement with the union -- the senior

ity benefits plainly called for by their written agreements:

"Seniority rights of each trainman...to commence on the date and

hour employed..." (R.116:110; 163:61). For more than twenty

years after Steele (with an isolated exception in the Waycross

Yard in late 1950)(R.117:46-47), no black persons were admitted

19/ Given these events commencing with the BRT's 1899 convention

pledge to "clearing our lines of this class of workmen, T. 15 and

continuing with consummation of the 1945 agreement to keep blacks

out of the trainmans craft, the defendants assertion that "union

membership did not affect employment decisions on ACL" is sheer

sophistry. SCL at 30.

*

20/ In 1946, SCL called Booker T. Snowden, train porter (R.116:

115) to work as an extra brakeman (_id. , 120) on a freight train

going south to Waycross (_id. , 122). He continued in this employ

ment until at least 1 953 (ici. , 1 27-28). Throughout the 1950's

the company used Uley Hamilton as a switchman at its Southover

Yard in Savannah (_icJ. , 175-80, 1 85). Snowden and Hamilton were,

in pursuance of the unwritten understanding with the union (i^.,

122), denied entry onto the UTU seniority roster. Some members

of the union sought to correct this for Mr. Snowden; the motion

to admit him, however, was defeated (id.).

19

to any train service seniority roster in the seniority

districts where plaintiffs were employed (R.116:58-74,

164-66; 117:46-47).

Apart from these exceptions, the company honored its

agreement with the union not to use blacks in the craft.

In 1955, plaintiff Franklin D.R. Bell applied for a switch

man's job at the Moncrief Yard in Jacksonville. He was in

formed that the company did not now hire blacks in the train

service (R. 20:16-17; R.48-7; R.93:l; R.211:8), and was in

stead made a waiter (R.39:3), an all-black job classification >

in a separate bargaining unit (T.256). Bell's experience

was repeated by plaintiffs Walter Odol and William K. Lindsey

in 1963; each applied for trainman's work; each was told —

Odol in vulgar terms (R.211-9) — that the railroad did not

hire blacks for train service (id.; R.20:19-20, 22; R.48:7;

R. 131:1, 6; R.211:10);

In 1963, plaintiff David Jones, who had originally

applied for any job he could get (T.255), sought transfer to

the trainman's craft (T.257-59). His application met the

same fate as the applications of Bell, Odol and Lindsey: no

blacks as trainmen (T.259-60). Jones, however, was per

sistent. He repeated his application in 1964, and again,

in 1965 (id. ). On this last try, he learned the real

reason for his failures: transfer was impossible "due to

20

letter

2_l/seniority rules governing the crafts" (SCL Ex. 24A,

of February 10, 1965, admitted at T.381, emphasis added. See

also T.365). One week later, Mr. William Seymour, then director

of labor relations for the railroad (T.215-17), apparently con

firmed that the seniority rules were being used to prohibit

22/

blacks from transferring. The rules were not applied to whites

seeking transfer: they came freely (T.260). Indeed, it was

the railroad's policy to fill trainmen's jobs by transfer from

other crafts (T.259-60).

Several months after Title VII became law, and eight

months after Mr. Jones' last application, the railroad, after

having been visited by a government official, granted Mr. Jones'

transfer request. He thus became the first black in more than

20 years to overcome the union-induced policy which prevented

blacks from establishing trainman seniority (T.263-64).

21/ This exhibit is included in this brief at App. 2.

22/

A notation on the bottom of the office memorandum says that

"Mr. Seymour called in re to union" (SCL Ex. 24A, included

here at App. 2). In view of the Company's position that

seniority rights are strictly union matters (R.87:4, 1[ 11),

there could have been no other reason for his call. Although

Mr. Seymour testified in the proceedings below (T.215ff.),

neither he nor anyone else for the railroad sought to deny

this obvious confirmation that the 1945 verbal agreement with

BRT was a seniority rule designed to prevent blacks from

transferring.

21

2. Unfortunately/ there is not always a remedy for

one's convictions of being wronged.... Your only

remedy is an administrative one through your labor

organization [in which a lawyer does not and cannot

get involved]....

23/UTU lawyer T. W. McAliley to plaintiff J. W.

Jones, October 7, 1974 (PI. Ex. 12).

Some time after Oliver Scarlett filed his 1972 EEOC

charge, he sought the union's help in exercising his seniority

to return to the Moncrief Yard (T.170). He was not then a

member of the organization (id.), although he had once tried to

join (T.168-69). "If you join the union," the local chairman

told him, "I'll sign the letter" (T.170). Scarlett joined. The

union signed (T.170-71; see also R.98:5).

David Jones applied to the BRT shortly after he trans

ferred to the trainman's craft in 1965. His application was

rejected (T.264-67). "You must have a member of the Brotherhood

to recommend you" (R.117:22; 118:2-3). J. W. Jones was turned

down for membership on three separate occasions (R.129:3).

Horace Thomas had applied earlier (T.200). "[We] would lose

half the members if we let [you] join" (T.199). After 1971, when

he was finally permitted to join the union, Thomas sought assist

ance from his local chairman. The official said, "I don't see

why [the railroad] won't straighten this out with you, because

T.125. Although Mr. McAliley is not on the staff of the

union, he represents it from time to time (T.428).

2$/

22

most of the Blacks have gone now anyway. There wouldn't be but

two or three to be inserted into the roster where they're sup

posed to be" (T.200, emphasis added). Thomas waited. He went

back to the railroad.

"[I]t [is] up to the Union," SCL told him.

"I've asked the Union," Thomas replied.

"[I]f you want to straighten it out, you'll have

to get you somebody to represent you [if the

union won't](T. 201).

"That's when I come to [see the lawyer] (flay,

24/

1976)(T.201; see also R.117:23).

See App. 3, ff., demonstrating the relation of union member

ship to the acquisition of trainman/conductor seniority.

23

I. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The record demonstrates that the district court's determina

tions that plaintiff Oliver W. Scarlett received a "Notice of

Right to Sue" from EEOC and that the union is adequately named in

plaintiff Scarlett's EEOC charge are not clearly erroneous. Rule

52(a) , F.R. Civ. P.

Under the standard established by International Brotherhood

of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) and interpreted

by this Court in James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559

F.2d 310 (9177) and Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp., 556 F .2d 758

(1977), a seniority system that has its genesis in racial discrimi

nation, was not neutually applied or was maintained with a

discriminatory purpose is not bona fide if it currently serves to

perpetuate the effects of prior discrimination. In this case the

district court properly found that the seniority system was

maintained with an illegal purpose.

The statute of limitations applicable to actions brought in

the State of Georgia pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1981 is borrowed

from Ga. Code § 3-704. See United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973). Acts or practices of intentional

racial discrimination such as defendants concededly racially

based assignment, transfer and promotion practices violate

§ 1981. See Williams v. DeKalb County, 582 F .2d 2 (5th Cir.

1978). The district court properly held that actions for injunc

tive relief from intentional racial discrimination are governed

by the 20 year period of limitations set forth in Ga. Code §

3-704, such actions being "suits for the enforcement of rights

24

accruing to individials under statutes," Ga. Code Ann. § 3-704.

Where, prior to trial, the district court indicated its

intention to try first the general issue of whether or not the

seniority system was bona fide within the meaning of § 703(h) of

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), the district court erred in

denying relief to plaintiffs Bell, Odol and Lindsey on the ground

that they failed to "prove" that they applied for jobs as trainmen.

Where the bona fides of a seniority system was the issue to be

resolved at trial, the district court failed to apply the proper

legal standards for evaluating the claims of plaintiffs Bell,

Odol and Lindsey. See Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S.. 747 (1976). In such cases, the contours of relief for

those who did not testify at trial are properly reserved for a

later stage of the proceedings. Id_. , Baxter v. Savannah Sugar

Refining Corp., 495 F .2d 437 (5th Cir. 1974).

Plaintiffs Bell, Odol and Lindsey are entitled to retroac

tive seniority based on their 42 U.S.C. § 1981 claims.

II. ISSUES PRESENTED ON UNION APPEAL

Preface

While the union claims to have discovered eleven separate25/

issues on their appeal, we believe all of the questions to

be resolved on the unions appeal may be subsumed under four

headings as appears below.

25/ Although the employer-railroad has not appealed, it claims to

have discovered additional errors in the trial court's determina

tion.

25

A. THE TRIAL COURT'S FINDING THAT OLIVER SCARLETT

RECEIVED A RIGHT TO SUE LETTER IS

NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

In its findings, the trial court referred, on three

occasions, to plaintiff Oliver W. Scarlett's notice of right to

sue from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (R.33:6;

60:2, 201:2). In this Court, the union asserts that these find

ings are "completely unsupported by the evidence" (UTU at 33,

emphasis the union's) and that "the record is absolutely devoid"

of proof of a right to sue letter (UTU at 38, emphasis the union's).

This argument is frivolous. The notice of right to sue is in

2 6/the record at two places (R.16:10; 17:16), and was considered

by the trial court in its rulings on defendants' motions to dis-

2 7/miss and for summary judgment (R.33:6; 60:2).

B. THE TRIAL COURT'S FINDING THAT THE UNION WAS

NAMED IN OLIVER SCARLETT'S EEOC CHARGE

IS NOT CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

The trial court found that the EEOC charge filed by

Oliver Scarlett "clearly alleges employment discrimination

2 6/

The notice is also included in this brief at App. 1.

The union, without explanation, omitted these orders from

the Record Excerpts required by this Court's Local Rule 13.1.

27/

26

against both the Company and the union" (R.201:2, n. 2, citing

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408 F.2d 283, 291 (5th Cir.

1969). As correctly noted by Seaboard Coast Line, "this is a

straight question of fact and thus subject to the 'clearly er

roneous' rule" [Rule 52(a), F.R.Civ.P]. SCL at 35. The union's

attack on the court's finding has two evidentiary underpinnings:

Its frivolous assertion that no right to sue letter was proved

(see Part I, supra); and an equally frivolous assertion that

"the only charge proved by plaintiffs was the [1972] charge of

Oliver Scarlett." UTU at 36-37. See R.4:2, 7; 16:8; 31:3; 88:7;

129:10; 181:7; 193:2, and 194 for reference to the EEOC charges

filed by other plaintiffs. The trial court correctly applied

the controlling law in making his finding, and there is abundant

evidence to support it.

Upon receipt of the original charge, the EEOC, pursuant

to its statutory duty to serve charges upon respondents, prepared

an "Acknowledgment of Receipt" form, addressed to "United Trans

portation Union, 15401 Detroit Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44107."

Moreover, the right to sue letter (R.16:10; 17:16; App. 1) is shown

as being mailed to "United Transportation Union, 14600 Detroit

Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio." These internal EEOC records are suf

ficient by themselves to support the trial court's finding that

the "union seniority system" named in the EEOC charge is the

27

system operated by the United Transportation Union on the Sea

board Coast Line. See Thornton v. East Texas Motor Freight,

497 F.2d 416, 423-24 (6th Cir. 1974). And there is more.

In 1976, Mr. Scarlett filed a second EEOC charge, sub

stantially identical in its factual allegations with the first

charge, in which he named "United Transportation Union" as one

of the parties who discriminated against him. To the extent

that there may have been ambiguity in the first charge (neither

the EEOC nor the trial court found any), it was cured by this

second charge. Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d 455,

461 (5th Cir. 1970). See also H. Kessler & Co. v. Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission, 53 F.R.D. 330, 334 (N.D.Ga. 1971),

affirmed, 468 F.2d 25 (5th Cir. 1972); Camack v. Hardee's Food

Systems, Inc., 410 F.Supp. 469 , 475-77 (M.D.N.C. 1976). Cf.

Ridgeway v. Intern. Broth, of Elec. Wkrs., Etc., 466 F.Supp 595,

598-99 (E.D.I11. 1979); Cook v. Mountain States Telephone &

Telegraph Co., 397 F.Supp. 1217, 1222, 1224-25 (D.Ariz. 1975).

The trial judge correctly applied the law, and there is ample

evidence to support his finding of jurisdiction. This Court 28/

should affirm.

28/ UTU does not question the district court's holding that it is

not necessary for every plaintiff in a case that was determined not

to be a class action because the numerosity requirement of Rule

23 (a) had not been satisfied. This issue has been raised by SCL

in its brief. See SCL at 40. As this Court noted in Crawford v.

Western Electric Co., Inc., 614 F.2d 1300, 1308 (5th Cir. 1980),

every decision in this circuit that bears on the issue supports the

holding of the district court. The trial court's holding should be

reaffirmed. See Wheeler v. American Home Products, 563 F.2d 1233

(5th Cir. 1979).

28

C. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY DETERMINED THAT THE

SENIORITY SYSTEM WAS NOT BONA FIDE WITHIN THE

MEANING OF 703(h)

There are relatively few fundamental differences between

the parties regarding the facts and the law as to the bona

fides vel non of the seniority system in this case although

the parties appear to disagree on how the law should be applied

23/to the facts. The parties agree that the district court

used the proper standards for evaluating the bona fides of a

30/

challenged seniority system. (See SCL at 23-4; UTU at 3,

10) That standard was described by this Court as follows:

1. whether the seniority system operates

to discourage all employees equally

from transferring between seniority units;

2. whether the seniority units are in the

same or separate bargaining units (if the

latter, whether that structure is rational

and in conformance with industry practice);

29/ The union appears to disagree with the district court's

finding that the seniority system was maintained with an

intention to discriminate. Plaintiffs address this contention

at p.31, infra.

30/ SCL's offers an alternative suggestion that a seniority

system be regarded as "bona fide" within the meaning of § 703(h)

if it is "currently a genuine and authentic system for allocat

ing available work on the basis of seniority", SCL at 28. This

approach misses entirely the Congressional mandate that the

application of "different terms, conditions or privileges of

employment pursuant to a bona fide seniority ... system" that is

" ... the result of an intention to discriminate on the basis of

race ..." is not entitled to the immunity accorded by § 703(h)

of Title VII. Further SCL's suggestion adds nothing to this

Court's operational definition of what constitutes a bona fide

seniority system within the meaning of §703(h). See James v.

Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F .2d 310 (5th Cir” 1977);

and Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp., 556 F .2d 758, 760 (5th Cir.

1977).

29

3. whether the seniority system had its genesis

in racial discrimination; and

4. whether the system was negotiated and has

been maintained free from any illegal

purpose.

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F .2d 310, 352

(1977) cert, denied 434 U.S. 1034 (1978). Properly applied, a

court should analyze each factor in order to determine if the

system had either its genesis in discrimination, or was not

neutrally applied, or was maintained with a discriminatory pur

pose. If the answer is affirmative to any one of these factors,

then a court may conclude that the system was not bona fide and

30/

was unlawful. An intentionally discriminatory creation,

application or maintenance of a system removes that system from

the protection of Section 703(h) because the racial differences

would be the result of an intention to discriminate. See Myers

v. Gilman Paper Corp., 556 F .2d 758, 760 (5th Cir. 1977) (per

curiam), cert. dismissed, 434 U.S. 801 (1977); James v. Stockham

Valves & Fittings, Co., supra, 559 F .2d at 351; Acha v. Beame,

570 F .2d 57, 64 (2d Cir. 1978) ("A system designed or operated to

discriminate on an illegal basis is not a 'bona fide' system");

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 586 F .2d 300, 303 (4th Cir.

31/ It would seem that a finding as to the "irrationality"

of the system would properly lead to an inference regarding

whether there was a discriminatory purpose in the development or

the maintenance of the system. Unlike a finding with respect to

the other factors, a determination of "irrationality" would not

independently lead to a conclusion of non-bona fides. This

follows from the fact that Title VII proscribes discrimination

but it does not necessarily prescribe rationality. But there

is a logical inference that an irrational system which has a

discriminatory effect was created with the intent to achieve

that effect. Cf. Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Corp., 429 U.S. 2^2, 26(5 ( 1 977).

30

1978) (The system "would not be bona fide if it either currently

served a racially discriminatory purpose or was originally

instituted to serve a racially discriminatory purpose.");

Alexander v. Aero Lodge No. 735 (IAM) 565 F .2d 1364, 1378 (6th

Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 436 U.S. 946 (1978); Chrapliwy v.

3 2/

Uniroyal, Inc., 15 FEP Cases 822, 826 (N.D. Ind. 1977).

As the district court noted and defendants emphasize,

"at trial, the plaintiffs conceded that the system meets

the first three [James] criteria." R. 201:4. Nevertheless

defendants treat extensively the origins of the seniority

system, e.g. , see UTU at 25-7, and SCL at 15-17. The district

court determined that the seniority system was not bona fide

within the meaning of § 703(h) of Title VII because the record

33/

disclosed discriminatory maintenance. It is the issue of

discriminatory maintenance that is the subject of this appeal.

The UTU attacks as erroneous the determination of the

district court that the seniority system was consistently

maintained with an intention to discriminate on the basis of

race. The union does not seriously question the district

court's finding that the seniority system was perverted in

order to deprive plaintiffs of their seniority based right

32/ Moreover, the Supreme Court indicated that the lower court

decisions such as Quarles v. Philip Moris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505

(E.D Va. 1968) and Local 189, United Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F .2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S 919

(1970), were consistent with Teamsters to the extent that these

"decisions can be viewed as resting upon the proposition that a

seniority sytem that perpetuates the effects of pre-Act dis

crimination cannot be bona fide if an intent to discriminate

entered into its very adoption." 431 U.S. at 346 n.28.

33/ Defendants expert Dr. Mater described it variously as "abuse"

and "perverted" use of the seniority system, T. 95.

31

to be called for promotion. Indeed the UTU agrees with the

determination of the district court that "promotion from trainman

to conductor is at least partially a function of seniority" (R.

201:5). See UTU at 41. Instead it seeks to lay all of the cause

of the total absence of blacks from the position of conductor on

"managerial prerrogative" (sic) in hiring and promotion and a

promotional examination which it claims, without citation to the

34/

record, conductors were required to pass. See UTU at 41,

42— 3, 21. These claims are unsupported by the record. (See pp.

12-15, supra.) The record evidence demonstrates that the

unions were deeply implicated in the exclusion of blacks from

the trainman/conductor craft. See pp. 11-15 and 18-21, supra.

It shows that the initial assignment and transfer opportunities

of blacks were affected by union seniority agreements. See pp.

18-21, supra. It shows that the union never sought to prevent

perversion of the seniority rights of black brakemen to be

"called" for promotion, T. 426. Regarding the requirement that

candidates for promotion to conductor pass an examination, the

contract required that the senior brakeman be "called for examina

tion," R. 116:111. Prior to 1967 none of the plaintiffs were

ever "called" as required by the above quoted seniority rule, R.

201:7. Thus questions regarding plaintiffs' ability to pass

these tests were not reached. In any event being "called" for

examination was tantamount to being promoted. No trainman except

34/ The union also makes reference to the fact that conductors

are required to be able to read and write. It wisely does

not claim that the plaintiffs lacked these skills. Plaintiffs

now occupy conductor positions and thus have demonstrated

their qualifications for the job.

32

plaintiff David Jones had ever failed the examination and the

district court found that Jones' "'failure' of the 1969 con

ductors examination was due to his race," R. 201:11.

Although defendant SCL did not appeal from any ruling of

the district court adverse to it, it nevertheless has advanced

its own theory for reversal of the district court's determina

tion that the seniority system is not immunized by § 703(h)

of Title VII. The Company appears to concede that the seniority

system may not have been bona fide during periods of its opera

tion prior to April 7, 1972, 180 days prior to the date on which

plaintiff Scarlett filed his charge with the EEOC. See SCL at

21. Instead it emphasizes the post-April, 1972 operation of the

system and argues that the system "currently" is bona fide. See

SCL at 21, 25, 32. This claim brings into sharp focus the issue

which must be resolved on this appeal: May a seniority system

which at certain times in the past was consistently perverted in

order to achieve a racially discriminatory purpose be deemed

bona fide within the meaning of § 703(h) of Title VII where the

effects of those racially discriminatory acts are being perpet

uated by the current operation of the seniority system? The

district court correctly answered this question in the negative.

There can be no doubt that the collectively bargained

rule that a brakeman be "called" for promotion in order of

his seniority is a part of the seniority system for it

determines when one begins to accumulate seniority as a conductor.

California Brewers Assn, v. Bryant, supra. And the district

court correctly so found, R. 201:5. For a period of at

33

least 80 years, ending in the late 1960's or early 1970's the

defendants consistently perverted this seniority rule by

withholding from blacks the benefits that normally flow from

the accumulation of seniority. And the district court

properly so held, R. 201:5.

Plaintiffs agree that most of the intentionally discrimina

tory conduct that perverted the seniority system occurred more

than 180 days prior to the date on which plaintiff Scarlett filed

a charge with the EEOC. However the fact that the intentionally

discriminatory acts rendering the seniority system non-bona fide

are remote in time does not alter the fact that the requisite

intent has been established. See Keyes v. School District No.

1., 413 U.S. 189, 210 (1973), and Dayton Bd. of Educ. v. Brinkman

35/

443 U.S. 526, 537 (1979). In Teamsters itself, the Supreme

Court recognized that intentionally discriminatory acts which

pre-date the effective date of Title VII can operate to remove

the limited immunity accorded bona fide seniority systems for "a

seniority system that perpetuates the effects of pre-Act discrimi

nation cannot be bona fide if an intention to discriminate

entered into its very adoption." Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at

346, n.28.

For most of plaintiffs careers the seniority system was

not maintained free of any racially discriminatory purpose.

Instead it was maintained to provide only white men with the

35/ In Keyes, the acts of intentional discrimination that

gave rise to the constitutional violation occurred prior to 1954 when Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

was decided. See Keyes, supra, 413 U.S. at 210.

34

opportunity to advance to the postion of conductor. See pp. 11-

21/ supra. Merely permitting plaintiffs to advance to con

ductor after 1967 simply could not cleanse suppurating festers

defendants implanted into the system. Legal surgery was

required to remove the infection, close the wound and restore

• • 36/plaintiffs to the same state of health as their white peers.

The remedy provided plaintiffs Scarlett, Starkes, Thomas, Rood,

37/J. W. Jones and D. Jones was an appropriate cure.

Although it did not appeal, SCL argues that the district

court "erred in allowing W.D. Rood to prevail where he did not

testify ..." SCL at 49. The union which has appealed does

not assert this claim. Accordingly this assignment of error is

not properly before this Court. See United States v. American

Railway Express Co., supra. In any event, the district court

was plainly correct in according a remedy to plaintiff Rood.

Rood was a switchman who prior to 1970 was not "called" for

36/ Thus contrary to SCL's claim of no continuing violation, see

SCL at 37-40, this case presents a classic example of a continuing

violation which may properly be the subject of an EEOC charge at

anytime during the period in which its effects are being felt.

See Fisher v. Proctor & Gamble Mfq. Co., 613 F.2d 527, 540 (5th

Cir. 1980); Shehadeh v. Chesapeake & Potomac Tel. Co. of Md., 595

F.2d 711, 724 (D.C. Cir. 1978).

37/ SCL's repeated assertion that the "current operation"

of the seniority system is bona fide is simply wrong. The

district court expressly found that "the non-bona fide seniority

system clearly perpetuates the effects of [defendants' prior

refusal to promote plaintiffs]. Because of the prior racial

discrimination the conductors with the longest tenure are without

exception white and the advantages of the seniority system flow

disproportionately to them and away from these plaintiffs" R.

201:7. Thus, contrary to SCL's contention this is not a case,

like EEOC v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry. Co., 577 F .2d 229, 233 (4th

Cir. T978) where tne plaintiffs did not assert that the current

seniority system was discriminatory.

35

promotion to conductor solely because of his race. He

was in precisely the same position as plaintiff Scarlett and the

district court so indicated in its order of July 7, 1977,

R. 192:5. Rood complained that the seniority system was

consistently maintained to discriminate against blacks.

SCL also claims that plaintiff David Jones' claim to 39/

promotion was "unrelated" to the claims of the other plaintiffs.

See SCL at 50. It argues that his claim of promotional dis

crimination was limited to his failure of the promotional 40/

examination. Id_. D. Jones' claim, like that of all of

the plaintiffs also addresses the discriminatory maintenance of

the seniority system. See R. 192:1.

Plaintiff D. Jones, like plaintiffs Bell, Odol and Lindsay,

was hired after the union (the BRT) succeeded in getting the

railroad to agree not to hire anymore blacks into the switchman 4J,/

classification. See pp. 18-21, supra. That agreement had the

necessary and foreseeable consequence of preventing blacks from

competing with whites for jobs and the accumulation of seniority

in the trainman/conductor craft. As a result, employment in the

38/

38/ Rood became a switchman on 11/3/42 and requested promotion

to conductor with adjusted seniority on 8/22/70. R. 4:6.

39/ This assignment of error too is not properly before this

Court.

40/ SCL argues that the district court's finding that D.

Jones' failure of the promotional examination was due to his

race, R. 201:11, "is error" but does not assert that it was

clearly erroneous. See SCL at 50. The evidence at trial

demonstrates that his failure of the examination was due to the

retaliatory racial animus of a supervisor, T. 280.

41/ The union appears to agree, however grudgingly, that such

was case. See UTU at 22.

36

all-black porter, attendant, cook, waiter and air bleeder class

ifications provided the only opportunity for blacks to accumulate

seniority for any purpose. The record evidence shows that the

railroad plainly understood that the placement of these plaintiffs

outside the trainman/conductor craft was a part of the seniority

agreement with the union for when, in 1964 and 1965, plaintiff D.

Jones sought transfer into this craft he was advised that the

requested transfer "was not practical due to the seniority rules

governing the crafts". (See SCL Ex. 24A, letter of February 10,

1965).

SCL's refusal to promote plaintiffs Scarlett, Starkes,

J.W. Jones, Thomas and Rood to conductor despite the existence

of a contractual provision that they be "called" for promotion

is additional evidence that the entire system was maintained

with an illegal purpose. Proof of a systematic program of

intentional discrimination with respect to a substantial part

of the seniority system is itself prima facie proof but that the

entire system is unlawful absent sufficient proof to the con

trary by the defendants. See Keyes, supra, at 203 and Columbus

Bd. of Educ. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 458 (1979). Here, not

only have defendants failed to offer contrary proof, but plaintiffs

proof shows that the intentionally discriminatory acts that

resulted in the exclusion of plaintiffs Bell, Odol, D. Jones

and Lindsey from the switchman classification were merely a later

skirmish in the relentless campaign of the union to deprive

blacks of all seniority rights in the trainman/conductor craft.

See pp. 11-18, supra. Clearly, because of the agreement between

37

the BRT and the railroad, the isolation of these plaintiffs in

black jobs results in the advantages of the seniority system

flowing disproportionately to white conductors hired at the same

time as these plaintiffs and away from these plaintiffs. They

are entitled to a remedy. Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229,

241-42 (1976); Columbus Bd. of Educ. v. Penick, supra.

D. PLAINTIFFS ARE ENTITLED, PURSUANT TO 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, TO INJUNCTIVE RELIEF FROM THE CONSEQUENCES OF

DEFENDANTS' INTENTIONAL RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

ASSIGNMENT, TRANSFER AND PROMOTION PRACTICES EVEN IF

THE SENIORITY SYSTEM IS FOUND TO BE BONA FIDE.

Defendant UTU next argues that a "seniority system validated

under § 703(h) of Title VII is not susceptible to attack under 42

U.S.C. § 1981", UTU at 46, and the district court erred in

applying the 20 year Georgia statute of limitations, Ga. Code

42/Ann. § 3-704, to plaintiffs claims for injunctive relief,

UTU at 46-8.

As to the union's first claim there is no dispute and the

findings of liability as to § 1981 are not to the contrary.

In this Circuit seniority systems that pass muster under Title

VII are bona fide under § 1981. See Pettway v. American Cast

Iron Pipe Co., 576 F .2d 1157, 1189 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied,

439 U.S. 1115 (1979). However, plaintiffs' claims for injunctive

relief under § 1981 are not limited to challenge to the seniority

system. Plaintiffs are entitled to relief that involves seniority

__/ There are several orders of the district court that are

relevent to this issue. Those orders appear at R. 76:4-6, 82: 3-5 and 201:11-12.

38

adjustments based on their § 1981 claims of unlawful refusal to

promote (in the case of the conductor plaintiffs) and to assign,

transfer and promote (in the case of the trainman plaintiffs).

These claims of disparate treatment which occurred within 20

years of the filing of this action are directly actionable under

§ 1981 and do not involve any issues going to the bona fides vel

43/

non of the seniority system. An indispensable remedy to

this unlawful racial discrimination in assignment, transfer and