Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Tureaud, Jr. Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

December 31, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Tureaud, Jr. Brief for Appellee, 1957. 6ff643e0-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/d178c11a-2486-4f11-a6e2-cf5039a90086/board-of-supervisors-of-louisiana-state-university-agricultural-mechanical-college-v-tureaud-jr-brief-for-appellee. Accessed March 05, 2026.

Copied!

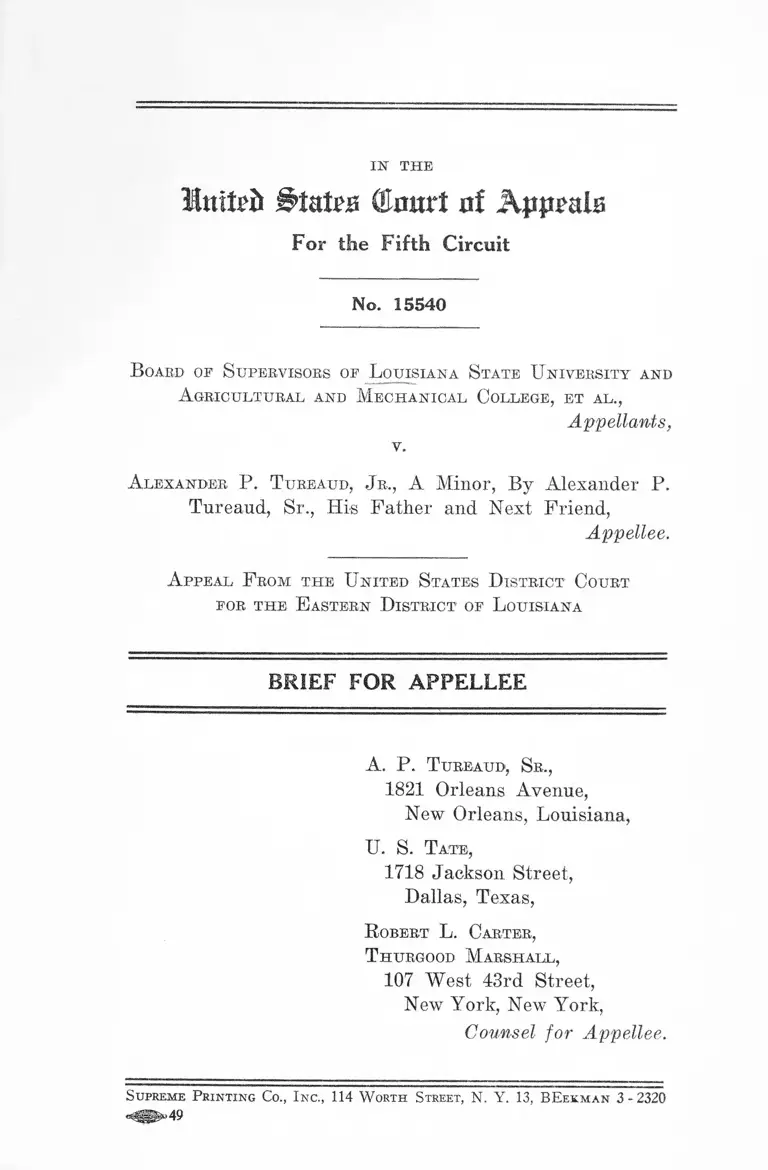

1ST THE

limtfii States Cflmtri nf Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 15540

B oard of S upervisors of L ouisiana S tate U niversity and

A gricultural and M echanical C ollege, et al .,

Appellants,

v.

A lexander P. T ureaud, Jr., A Minor, By Alexander P.

Tureaud, Sr., His Father and Next Friend,

Appellee.

A ppeal F rom th e U nited S tates D istrict C ourt

for t h e E astern D istrict of L ouisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

A. P. T ureaud, Sr.,

1821 Orleans Avenue,

New Orleans, Louisiana,

U. S. T ate,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellee.

Supreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekm an 3-2320

«^gj^49

(llmtrt sti Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 15540

-----------------------o------------- ----------

B oard of S upervisors of L ouisiana S tate U niversity and

A gricultural and M ech anical College, et al .,

Appellants,

v.

A lexander P. T ureaud, Jr., A Minor, By Alexander P.

Tureaud, Sr., Hi-s Father and Next Friend,

Appellee.

A ppeal F rom th e U nited S tates D istrict Court

for th e E astern D istrict of L ouisiana

——---------------- o------------- ----------

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE

Statement

This is a simple case involving the effort of appellee,

a Negro, to secure his constitutional right to equal edu

cational opportunities. The trial court found that appellee

could secure equal educational opportunity only by being

allowed to attend Louisiana State University and so

ordered, 116 F. Supp. 248. Upon appeal here, judgment

was reversed by a divided court on the ground that the

matter should have been heard before a three judge court,

207 F. 2d 807. We took the cause to the United States

Supreme Court, and this Court’s mandate was stayed and

subsequently the Supreme Court granted our petition for

2

writ of certiorari, vacated the judgment of this Court and

remanded the cause for reconsideration, 347 U. S. 491.

In the meantime, and prior to the Supreme Court’s

order staying this Court’s mandate, appellants secured a

dissolution of the injunction against them and promptly

expelled appellee from school. The procedural picture

thereby created was so confusing that appellee has been

unable to secure reinstatement, of the trial court’s injunc

tion until the instant judgment upon which this appeal is

based. It should be remembered, in this connection, that

appellee has not been in attendance at Louisiana State Uni

versity pending disposition of this case, although that was

clearly within the contemplation and expectation of the

Supreme Court and the basis for its order staying this

Court’s mandate.

ARGUMENT

In view of the School Segregation Cases, a single

district judge clearly has authority to enjoin the exclu

sion of a Negro from a state university solely because

of his race and color.

It is now clear that whatever procedural objections

could have been raised to the issuance of an injunction

by a United States District Judge sitting alone are now

no longer applicable. Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483; Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497. The United

States Supreme Court, in a sweeping and clear-cut opinion,

held that “ in the field of public education the doctrine of

separate but equal has no place. Separate educational

facilities are inherently unequal.”

There is no longer any doubt that a state policy main

taining racially segregated public educational facilities is

contrary to the constitutional mandate of the Fourteenth

Amendment. A mere reading of the opinion of the Supreme

3

Court in those cases makes it manifest that their interdic

tion against segregation per se and the application of

the “ separate but equal” doctrine embraced the entire

field of public education. In the light of these decisions,

no state policy, which seeks to maintain, as a part of the

state’s public educational system, segregated schools for

Negro and white students meets with the requirements of

the federal Constitution.

While there may have been room for doubt concerning

the power of the court below to grant injunctive relief in

this case prior to the decisions in the School Segregation

Cases, we submit that no question concerning this power

can be persuasive at this time. The decisions of the

Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases have con

clusively settled the substantive validity of state action

which seeks to enforce racial segregation in the field of

public education. No delicate questions of state-federal

relationship can now be involved in the enjoining of state

action in this regard as void and unconstitutional by an

ordinary district court. The Supreme Court has settled the

question, and lower federal courts must now follow the

Supreme Court’s formula. In short, the substantive issue

in this case—appellee’s right not to be excluded from

Louisiana State University on the basis of his race—no

longer presents a substantial federal question which would

necessitate the convening of a three-judge court. Ex Parte

Poresky, 290 U. S. 30 ; Jameson & Son v. Morganthau, 307

U. S. 171; Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. Ry. Co., 282 IT. S. 10.

Appellants seek to limit the reach of the School Segre

gation Cases to public elementary and secondary schools.

True, the cases decided involved elementary and secondary

schools, but these decisions, together with McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, 339 IT. S. 337, and Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U. S. 629, leave little doubt that whatever the

status of the “ separate but equal” doctrine in other areas,

4

it is no longer a valid constitutional yardstick with respect

to public education. It should be added, parenthetically,

that even application of that doctrine would be of little

benefit to appellants’ cause since the trial court’s original

grant of injunctive relief, which has now been reinstated,

was based not upon the unconstitutionality of segregation

per se, but upon appellants’ violation of the “ separate but,

equal” formula.

None of the cases cited by appellants are in point.

Steiner v. Simmons, 111 A. 2d 574 (Del. 1955), reversing 108

A. 2d 173 (Del. 1954), involves the right of public officials to

withhold relief as to a class seeking admission to elemen

tary school pending final terms of the relief granted in

the School Segregation Cases. But the United States

Supreme Court is seeking to evolve a formula which will

permit school officials to approach the question of redis

tricting and redefining school lines, affecting a large num

ber of persons, so as to conform to the Court’s decree with

out undue administrative disruption of the school program.

This approach was made only because of the large num

ber of Negro and white children who would be affected by

the transition. No -such problem arises in this case.

Fleming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas Co., 128 F.

Supp. 469 (E. D. S. C. 1955). Holmes v. City of Atlanta,

124 F. Supp. 290 (N. D. Ga. 1954); andl Clements v. Board

of Education, — F. Supp. — (S. D. Ohio 1955), cited

by appellants, are of dubious authority since all three cases

are pending before United States Courts of Appeal. Ap

pellants also relied upon the trial court’s opinion in Lone

some v. Maxwell, 123 F. Supp. (Md. 1954), but that case

was reversed by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit on March 14, 1955, — F. 2d —, on the

sweeping and all-inclusive ground that recent decisions of

the United States Supreme Court had stripped the “ sep

arate but equal” doctrine of validity in all fields.

5

As to the merits of this controversy, the court below

found that appellee could secure equal educational oppor

tunities only by being admitted to Louisiana State Uni

versity. This decision was and is clearly correct under

applicable constitutional standards. Brown v. Board of

Education, supra; Bolling v. Sharpe, supra; McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, supra. Since it cannot be said

that the Court’s findings are clearly wrong and not sup

ported by the evidence, its decision on the merits of this

controversy should be affirmed.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the reasons hereinabove indicated,

we submit that the judgment of the court below should

be affirmed.

A. P. T ueeatjd, Sr.,

1821 Orleans Avenue,

New Orleans, Louisiana,

U. S. T ate,

1718 Jackson Street,

Dallas, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellee.